1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly become a foundational technology in healthcare, driving advances across diagnostic precision, therapeutic planning, clinical research, and public health interventions. Recent work illustrates its broad applicability: predictive modeling for patient readmission, protocol automation in clinical trials, and disease identification through advanced signal processing all highlight the growing integration of AI into modern healthcare practice [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Beyond direct clinical use, AI-driven analytics have provided novel insights into social determinants of health, health equity, vaccine hesitancy, and healthcare accessibility, with implications for both health policy and pandemic preparedness [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Economic modeling that links health outcomes with market and financial indicators has further expanded the role of AI in assessing system sustainability and resilience during crises [

15]. Building on these foundations,

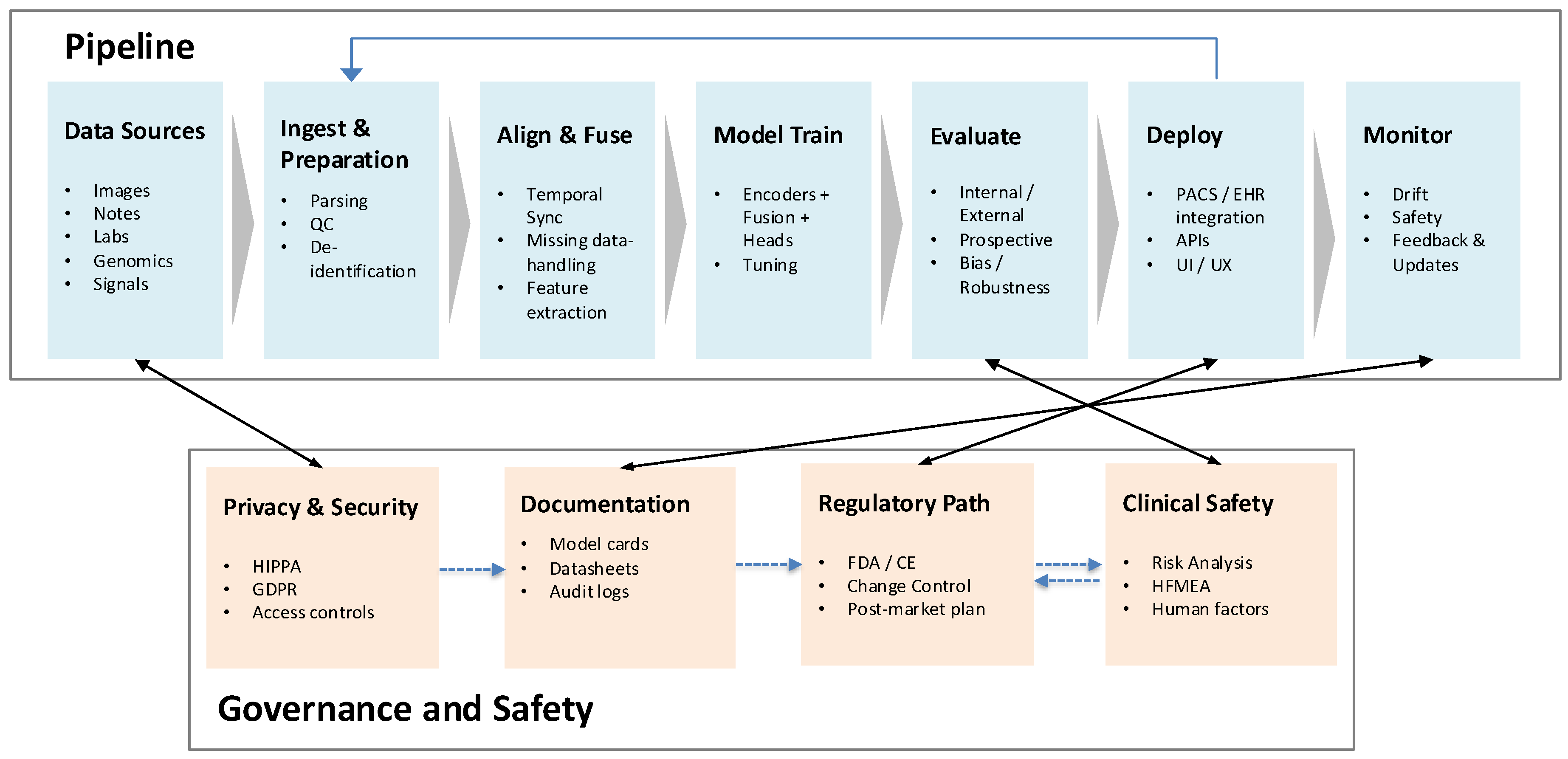

multimodal generative AI has emerged as the next frontier in diagnostic medicine. By jointly analyzing diverse data sources—such as radiology, pathology, clinical narratives, genomics, and physiologic signals—these models promise significant enhancements in diagnostic accuracy, interpretability, and personalized care. The overall clinical pipeline for multimodal diagnostic AI, from data ingestion and fusion to deployment and monitoring, is summarized in

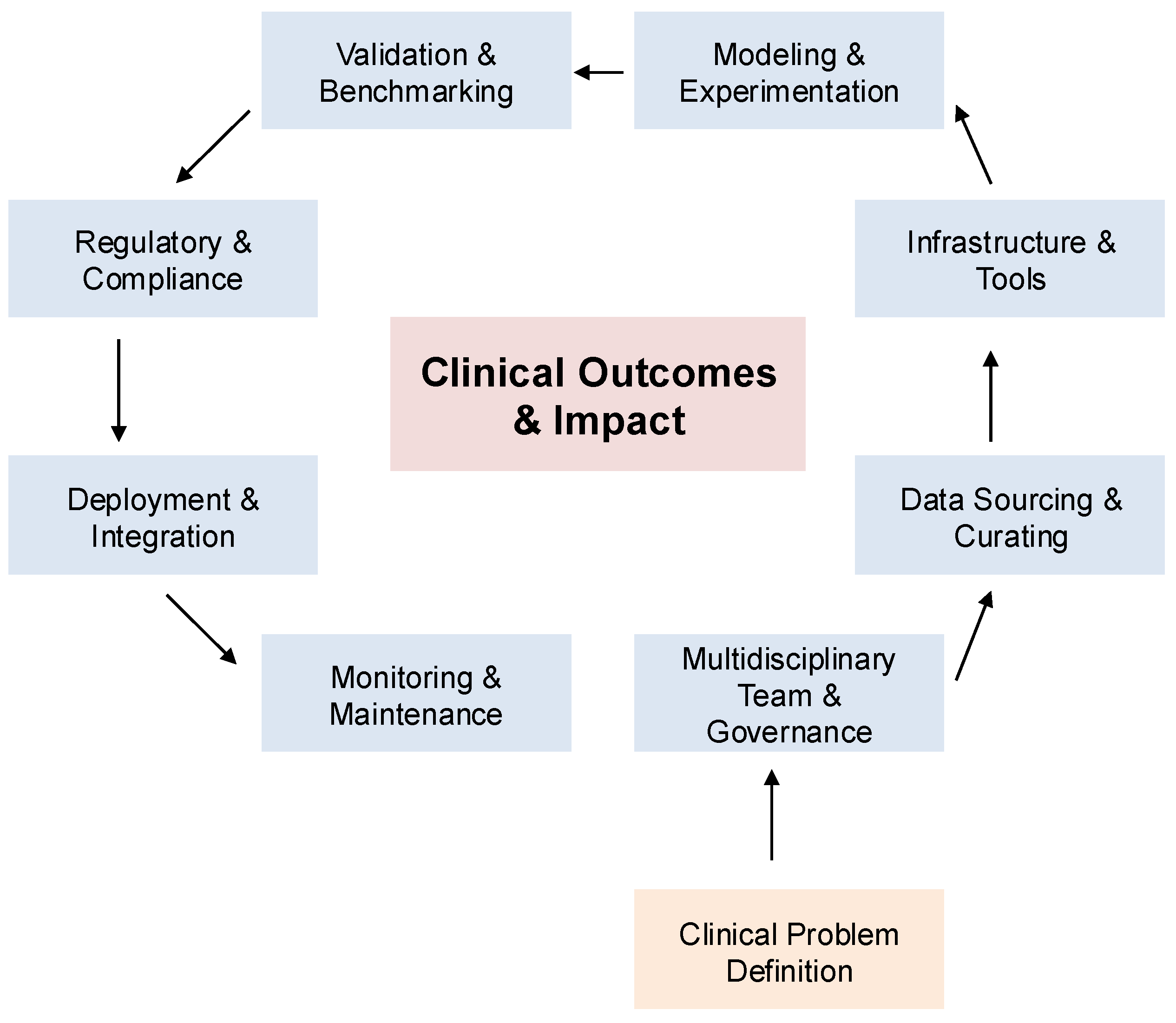

Figure 1. A broader perspective on the healthcare AI lifecycle, spanning data curation through governance and regulation, is illustrated in

Figure 2. Together, these frameworks underscore how multimodal AI approaches are positioned to transform medical diagnostics and enable safer, more effective integration into clinical workflows.

The integration of multimodal generative artificial intelligence (AI), which combines medical imaging data with textual and clinical information, is rapidly reshaping medical diagnostics by overcoming the limitations of unimodal approaches. Medical images such as radiographs, CT scans, MRIs, and histopathology slides provide crucial anatomical and physiological insights but often lack the interpretative context supplied by patient histories, laboratory results, and diagnostic reports. By jointly analyzing these heterogeneous data streams, multimodal AI enables more comprehensive diagnostic reasoning and has demonstrated significant improvements in diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and patient outcomes [

24,

25]. Notable benefits are observed across medical specialties. In oncology, for instance, integration of PET–MRI or PET–CT imaging with clinical records enhances tumor characterization and informs treatment planning [

26]. Similarly, in pathology, multimodal systems combining histopathological images with genomic data improve cancer grading, prognosis prediction, and recommendations for personalized therapy [

27,

28]. These integrated approaches provide clinicians with richer, contextually grounded insights than unimodal systems, particularly in complex diagnostic scenarios. Despite these advances, substantial challenges remain. The integration of heterogeneous multimodal data is technically complex, resource-intensive, and frequently hindered by limitations in data availability, annotation quality, and privacy protection [

29]. Sophisticated modeling architectures further increase computational demands, complicating clinical deployment in resource-constrained settings. Ensuring transparency and interpretability of multimodal models is also critical for fostering clinician trust, yet remains difficult given the inherent complexity of integrating diverse modalities [

24,

30].

A comparative overview of clinical applications across specialties is summarized in

Table 1, highlighting the spectrum of integrated data types, clinical benefits, and persistent challenges.

Beyond specialty-specific advances, multimodal AI closely mirrors physician reasoning processes by synthesizing imaging findings, laboratory results, and clinical narratives into unified diagnostic hypotheses. This alignment enhances clinical workflows, improves decision-making, and uncovers subtle diagnostic cues often missed by unimodal analyses [

39,

40]. For example, radiology systems that combine imaging with electronic health records have been shown to streamline diagnostic reporting, reduce errors, and improve efficiency [

26,

41]. However, clinical integration faces persistent obstacles. Clinician acceptance depends heavily on model interpretability, usability, and demonstrable impact, yet these attributes are often undermined by model complexity [

31,

40]. Ethical challenges, including privacy risks, security vulnerabilities, and the propagation of algorithmic biases, further complicate deployment and acceptance [

29,

42]. Addressing these barriers will require the development of interpretable and standardized modeling approaches, rigorous validation frameworks, and robust governance. Promising solutions include federated learning for privacy-preserving collaboration, explainable AI methods for interpretability, and user-centered interface design to enhance clinical usability [

31,

39,

43].

In summary, multimodal generative AI represents a transformative opportunity to advance diagnostic accuracy, align computational approaches with human reasoning, and strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration. Realizing its clinical potential requires addressing substantial technical, ethical, and regulatory hurdles through collaborative innovation, rigorous evaluation, and proactive governance.

2. Landscape of Multimodal Generative AI Models in Clinical Diagnostics

A diverse set of multimodal generative AI models has recently emerged, each characterized by distinct architectures, strengths, and clinical capabilities. Med-PaLM M extends Google’s PaLM language model through fine-tuning on medical datasets, employing transformer-based architectures with multimodal attention mechanisms to integrate textual data, medical imaging, and structured clinical information, thereby supporting tasks such as medical question answering and diagnostic reasoning [

39]. LLaVA-Med adapts the Large Language and Vision Assistant (LLaVA) framework for clinical contexts by combining vision transformers specialized in medical image interpretation with language models, enabling effective joint analysis of radiology reports and their corresponding images [

44]. BiomedGPT further broadens the scope of multimodal integration by incorporating genomic sequences, medical literature, protein structures, and clinical notes, using modality-specific encoders and cross-attention mechanisms to perform complex tasks such as biomedical entity recognition, hypothesis generation, and personalized treatment planning [

45]. Finally, BioGPT-ViT combines Vision Transformer (ViT) capabilities for imaging analysis with GPT-based text processing, demonstrating utility in medical image captioning, visual question answering, and multimodal clinical decision support systems that align imaging data with electronic health records [

27]. Collectively, these models represent complementary approaches toward unifying heterogeneous medical modalities, enabling both specialized and generalized diagnostic applications.

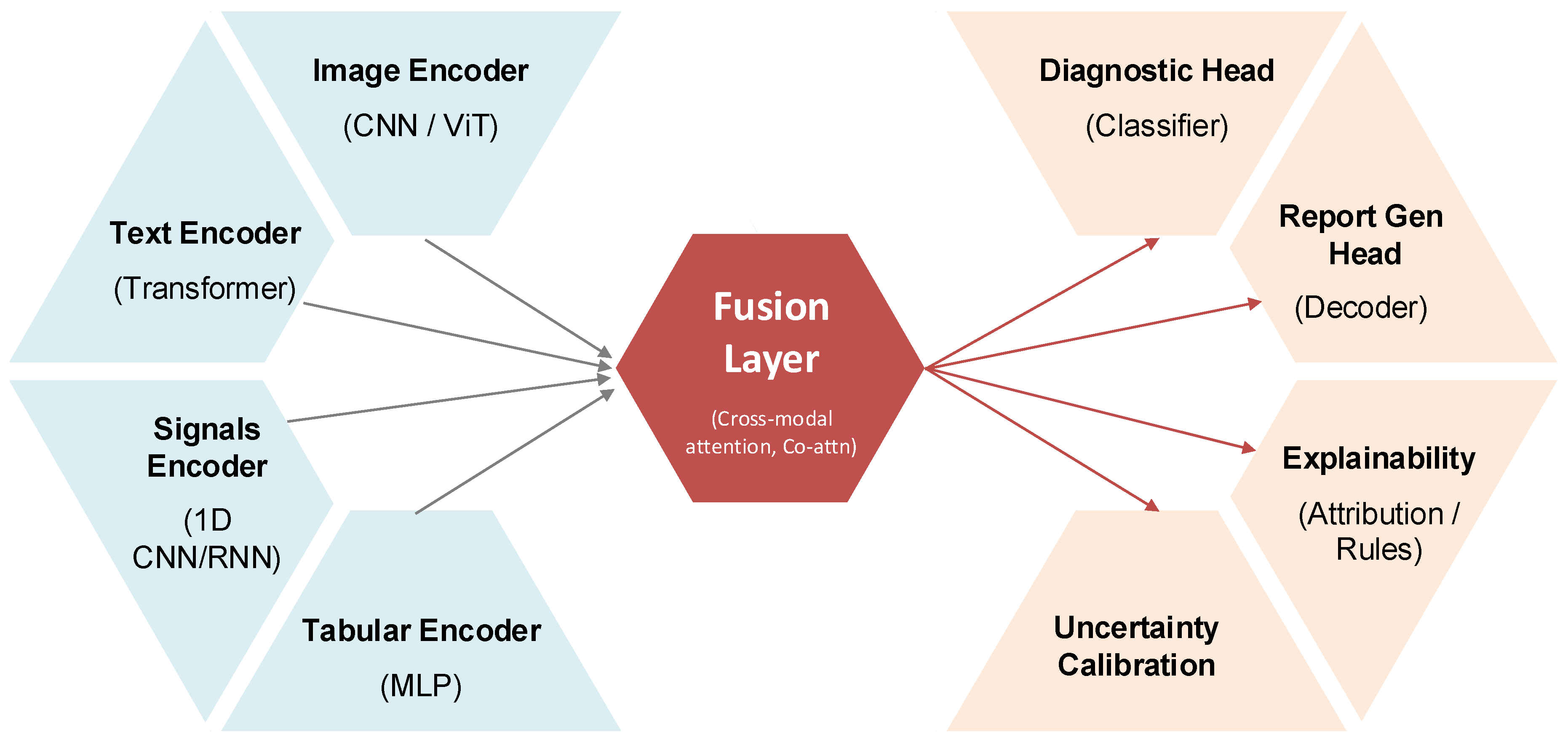

The conceptual design of a representative multimodal diagnostic AI architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3. In this framework, modality-specific encoders—such as vision transformers for medical images, transformers for clinical text, 1D CNN or RNN modules for signals, and multilayer perceptrons for tabular data—are integrated via a cross-modal fusion layer (e.g., co-attention mechanisms). Task-specific heads, such as classifiers for diagnostic prediction or decoders for automated report generation, are appended to this shared latent space, while auxiliary modules for explainability (e.g., attribution maps, rules) and uncertainty calibration ensure clinical transparency and reliability.

A structured comparison of the major multimodal generative AI models is presented in

Table 2, which highlights their distinctive integrated modalities, clinical applications, strengths, and known limitations. Med-PaLM M demonstrates robust natural language interaction and domain knowledge but remains limited in terms of real-world validation [

29]. LLaVA-Med shows high performance in CT and X-ray interpretation but underperforms in ultrasound analysis [

41]. BiomedGPT excels at broad biomedical integration across genomics, proteins, literature, and clinical notes, though its interpretability is constrained by model complexity [

39]. BioGPT-ViT effectively merges imaging and textual modalities for clinical reasoning support and analytics, yet faces risks of hallucinations in interpretation that may undermine clinical trust [

40]. Together, these models underscore both the promise and the persistent barriers of multimodal AI in advancing diagnostic practice.

Multimodal generative AI models differ substantially in their capacity to integrate diverse data modalities, and these differences directly shape their clinical effectiveness and scope of application. Med-PaLM M and LLaVA-Med specialize in combining medical imaging with clinical text, streamlining radiology workflows by providing preliminary interpretations and automated diagnostic recommendations that reduce clinician workload while improving diagnostic accuracy [

39,

44]. BiomedGPT expands the integration horizon by incorporating genomic sequences, temporal data, medical literature, protein structures, and clinical notes, thereby enabling comprehensive disease profiling particularly suited for complex conditions that require multidimensional biological, clinical, and imaging insights [

45]. BioGPT-ViT, by merging Vision Transformer-based image analysis with GPT-driven language processing, has proven effective in tasks such as image captioning, visual question answering, and multimodal clinical decision support, excelling in real-time scenarios where clinical text and imaging data must be synthesized simultaneously to guide decision-making [

27]. Collectively, these models demonstrate the capacity of multimodal AI to improve diagnostic workflows across radiology, oncology, and other specialties. For example, Med-PaLM M and LLaVA-Med have shown utility in automating radiology reports and facilitating early detection of abnormalities [

39,

44], while BiomedGPT enhances oncology workflows by integrating imaging, molecular, and clinical findings into nuanced, individualized diagnostic recommendations [

45]. BioGPT-ViT extends this further by enabling clinically relevant multimodal analytics that can provide detailed image-captioning and real-time reasoning support in complex diagnostic settings [

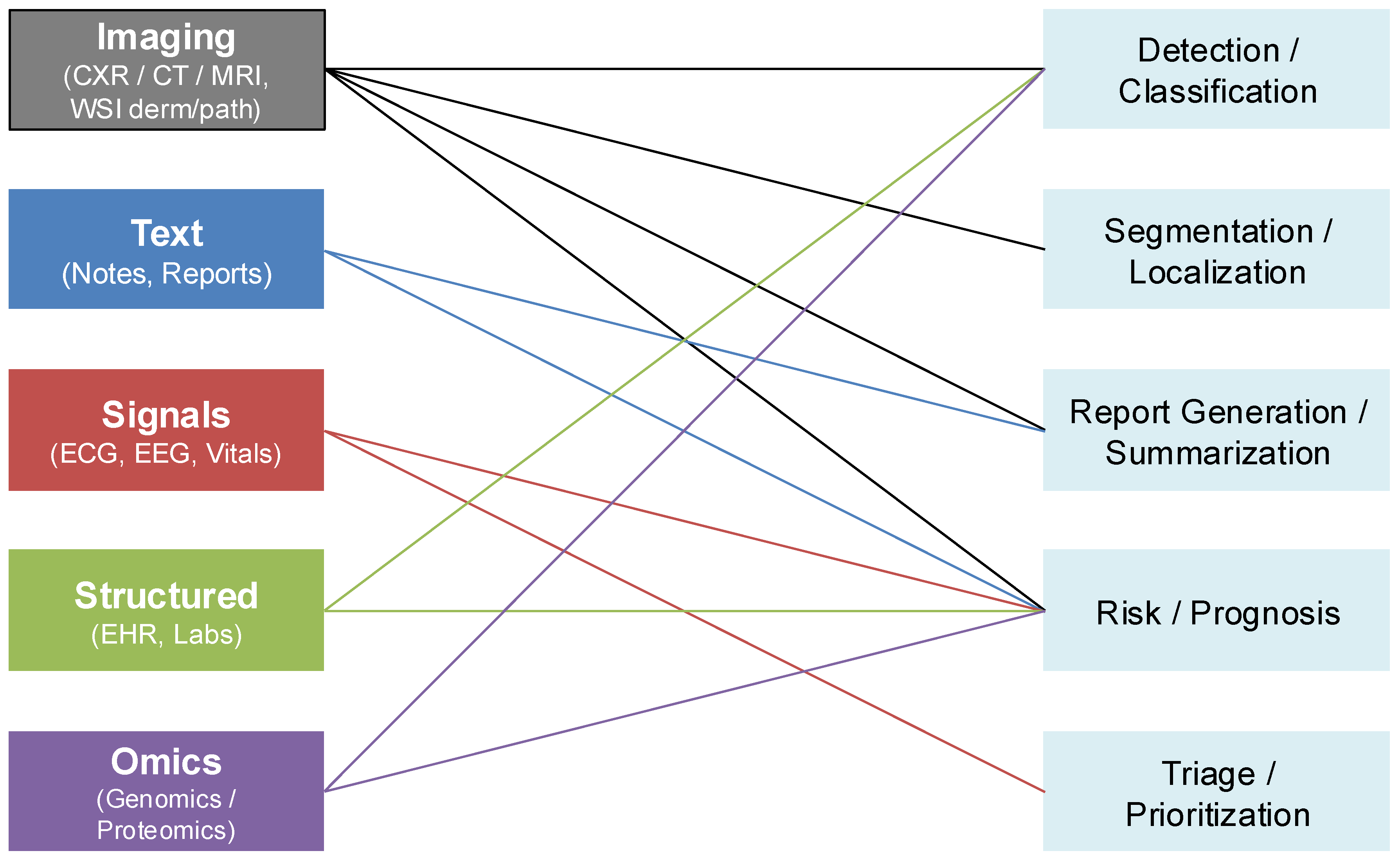

27]. The breadth of these data modalities and their clinical applications are illustrated in

Figure 4, which maps imaging, textual, physiologic, structured, and omics data streams to downstream diagnostic tasks such as detection, segmentation, report generation, prognosis, and triage.

Despite these promising advances, multimodal generative AI continues to face significant barriers that limit clinical adoption. The most fundamental challenge is data quality, as model performance depends on large, representative, and well-annotated multimodal datasets. Inadequate representation of minority populations introduces biases that can exacerbate existing disparities in healthcare delivery [

29]. Equally critical are interpretability challenges: the opacity of decision-making in complex multimodal architectures undermines clinician confidence and trust, particularly in high-stakes diagnostic environments [

50]. Resource intensity poses additional barriers, as training and deploying multimodal models requires considerable computational infrastructure, which risks widening the gap between well-resourced health systems and underserved settings [

24]. Furthermore, ethical and privacy issues are amplified when integrating multiple sensitive data types; the risks of patient re-identification and data misuse necessitate stringent safeguards and regulatory oversight [

29]. Compounding these challenges, regulatory frameworks lag behind technological innovation, leaving clinical stakeholders uncertain about validation standards, approval pathways, and post-market monitoring requirements for multimodal AI systems [

50].

Addressing these challenges requires methodological, infrastructural, and governance innovations. Priority directions include the development of enhanced interpretability methods capable of explaining multimodal reasoning processes in clinically meaningful ways; the application of federated learning to facilitate cross-institutional collaboration without compromising data privacy; and the creation of standardized data integration pipelines that harmonize heterogeneous modalities for robust clinical use. Large-scale prospective clinical trials are essential to validate efficacy across real-world patient populations, while interdisciplinary collaboration among clinicians, AI researchers, policymakers, and ethicists will be crucial to navigate the ethical and regulatory landscape. In sum, although multimodal generative AI has already demonstrated its potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and personalized care across medical specialties, its long-term clinical translation depends on overcoming these technical, ethical, and regulatory hurdles through coordinated innovation and rigorous validation.

3. Multimodal LLM Design Approaches, Trade-offs, and Clinical Implications

The design of multimodal large language models (LLMs) for clinical diagnostics has rapidly advanced, with three dominant architectural paradigms—

tool use,

grafting, and

unification—each offering distinct trade-offs between flexibility, integration depth, interpretability, and computational efficiency. Tool-use approaches equip an LLM to orchestrate specialized external models for non-text modalities such as images, signals, or genomics, thereby functioning as integrative coordinators that route queries to the most appropriate expert module before synthesizing the results. This modularity allows the incorporation of validated, domain-specific tools and supports rapid updates without retraining the entire system, though it introduces latency, dependency complexity, and only shallow cross-modal learning [

39]. Grafting strategies connect pre-trained modality-specific encoders—such as vision transformers or clinical BERT variants—into an LLM backbone via adapters or fine-tuning, enabling joint intermediate processing of multimodal representations. These models achieve balanced performance across modalities with moderate resource demands, but their integration depth is limited and redundancy across modalities can reduce efficiency [

27]. By contrast, unification strategies train a single end-to-end architecture on multiple modalities simultaneously, enabling deep cross-modal reasoning and holistic diagnostic insight by embedding imaging, textual, genomic, and structured data into shared latent spaces. Unified models streamline analysis and eliminate reliance on external tools, but they demand extensive multimodal datasets, vast computational resources, and careful balancing to avoid overfitting or performance collapse across modalities [

50].

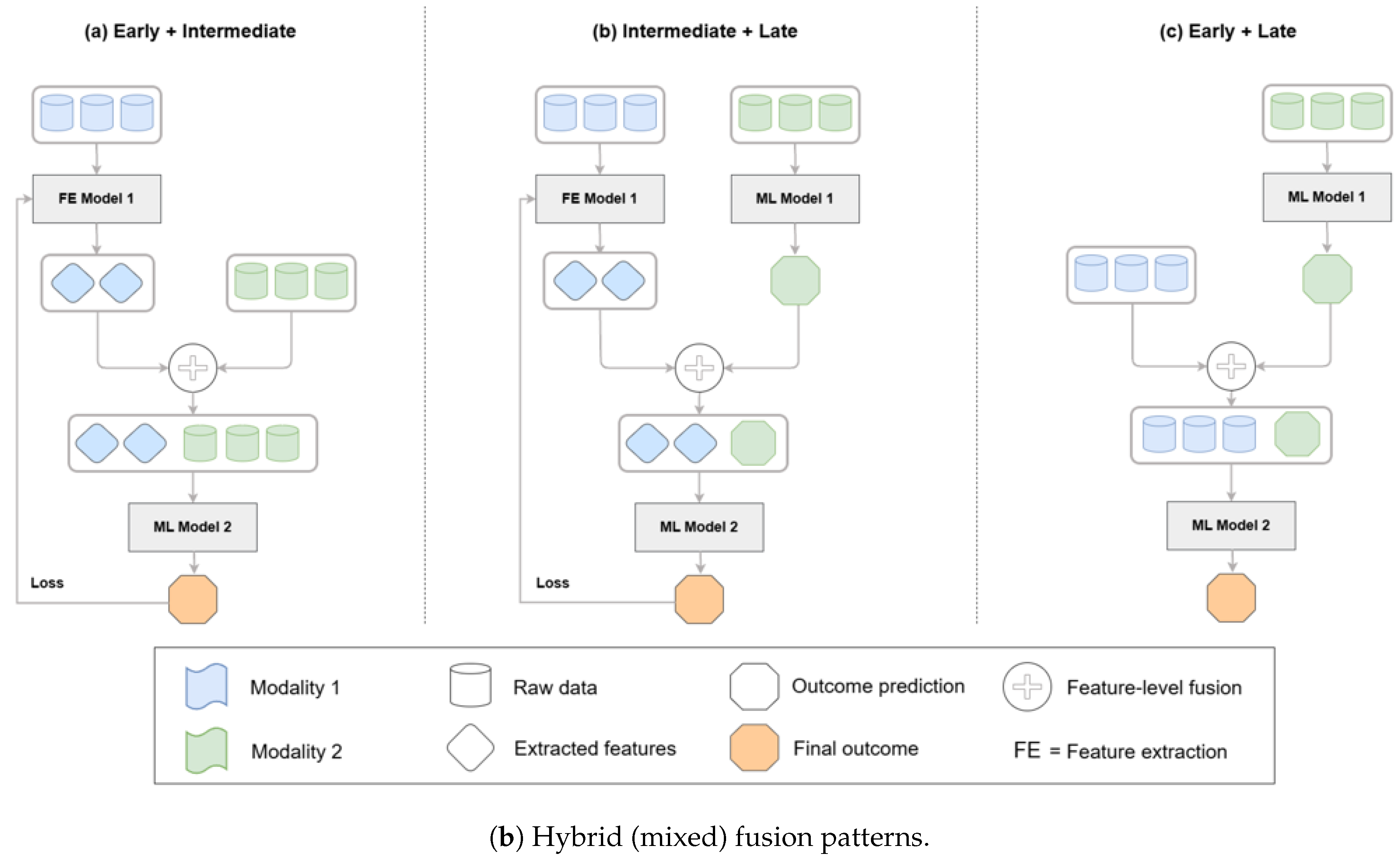

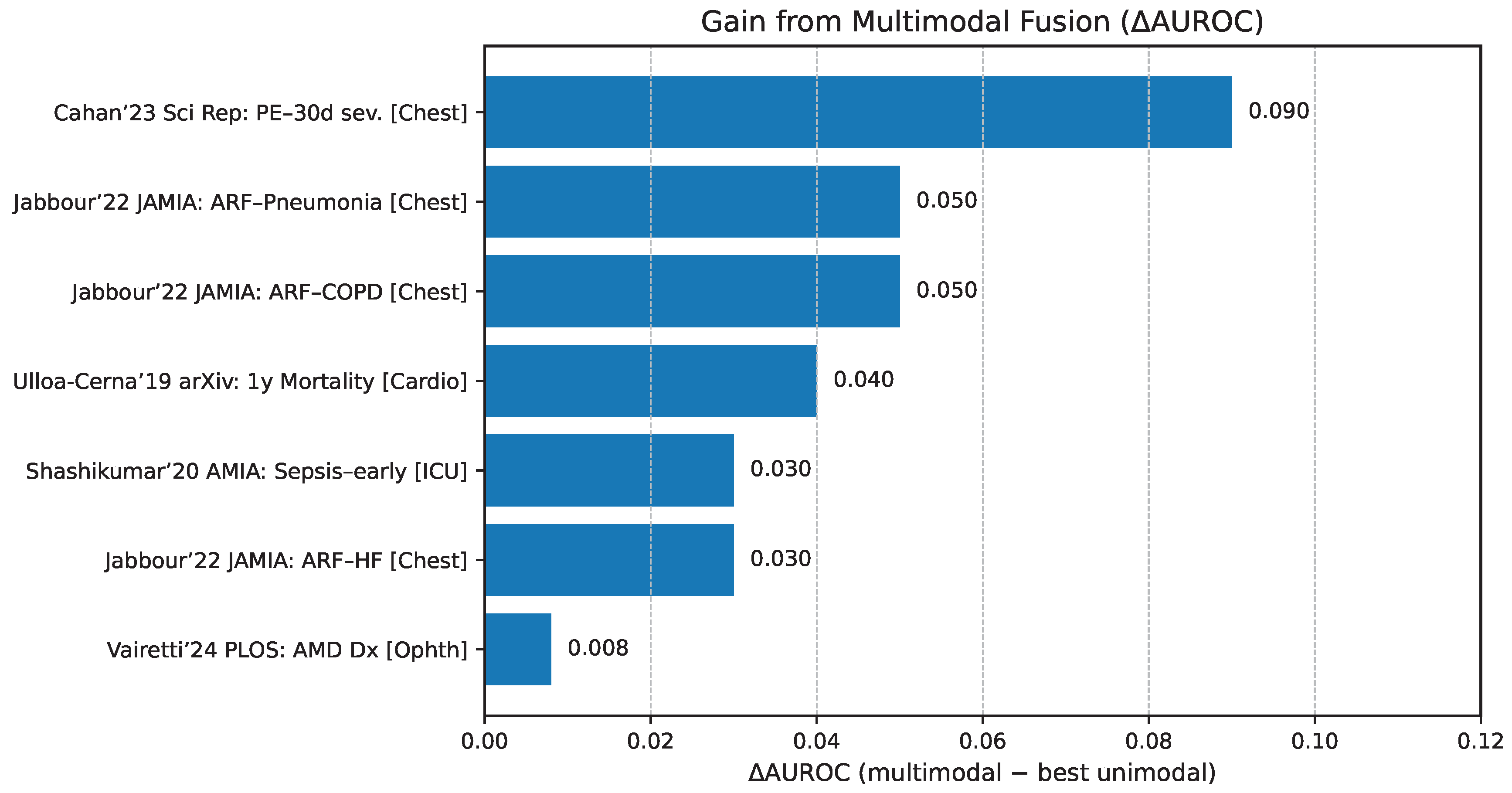

The comparative diagnostic value of these paradigms is illustrated in

Figure 5, which highlights reported improvements in AUROC relative to unimodal baselines across diverse clinical tasks. These findings emphasize that while unified models tend to yield the largest performance gains in integrative reasoning tasks, grafting and tool-use strategies can outperform in contexts requiring modularity, rapid specialization, or reliance on expert subcomponents.

- 3.0.1.

Tool Use Approach

The tool-use methodology equips large language models (LLMs) with the ability to orchestrate external specialized tools or domain-specific models, thereby extending their capacity to process modalities beyond their native textual input. In this paradigm, the LLM serves as an integrative coordinator that determines when additional modality-specific expertise is required and invokes external systems accordingly, whether for image analysis, speech recognition, or genetic interpretation. The outputs from these specialized modules are subsequently integrated into the LLM’s reasoning process to provide comprehensive diagnostic insights or recommendations [

56]. For instance, in radiological workflows, an LLM may request a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based model for lung nodule characterization and then combine these imaging results with textual patient records to generate a cohesive diagnostic report. This strategy offers considerable flexibility and modularity, as new or improved specialist modules can be incorporated without retraining the core model, while also capitalizing on extensively validated domain-specific tools to enhance diagnostic accuracy in specialized tasks. Nonetheless, tool-use approaches are not without drawbacks, as sequential invocation of multiple tools can introduce latency, the management of interdependencies among heterogeneous components increases system complexity, and the cross-modal learning achieved is often limited because integration occurs at a higher and more superficial representational level rather than through deeply unified embeddings.

- 3.0.2.

Grafting Approach

The grafting approach integrates pre-trained, modality-specific components directly into a foundational LLM via adapter layers or targeted fine-tuning, thereby allowing multimodal data to be jointly processed within the model’s representational hierarchy. By leveraging specialized encoders—such as vision transformers trained on imaging tasks or BERT-derived models adapted for clinical text—this strategy enables simultaneous interpretation of multiple modalities, such as pairing medical images with clinical notes to improve performance in pathology and radiology tasks [

27]. Grafted models benefit from reusing mature pretrained networks, thereby reducing both the volume of training data required and the associated computational costs compared to building fully unified models from scratch. Moreover, they tend to achieve balanced performance across modalities, making them well suited for clinical scenarios in which moderate integration between modalities is sufficient to yield actionable insights. However, the approach remains constrained by limited depth of cross-modal interaction, which may prevent capture of subtle interdependencies between modalities, as well as by redundancy in representational learning, which can reduce efficiency and hinder scalability when expanding to additional data types.

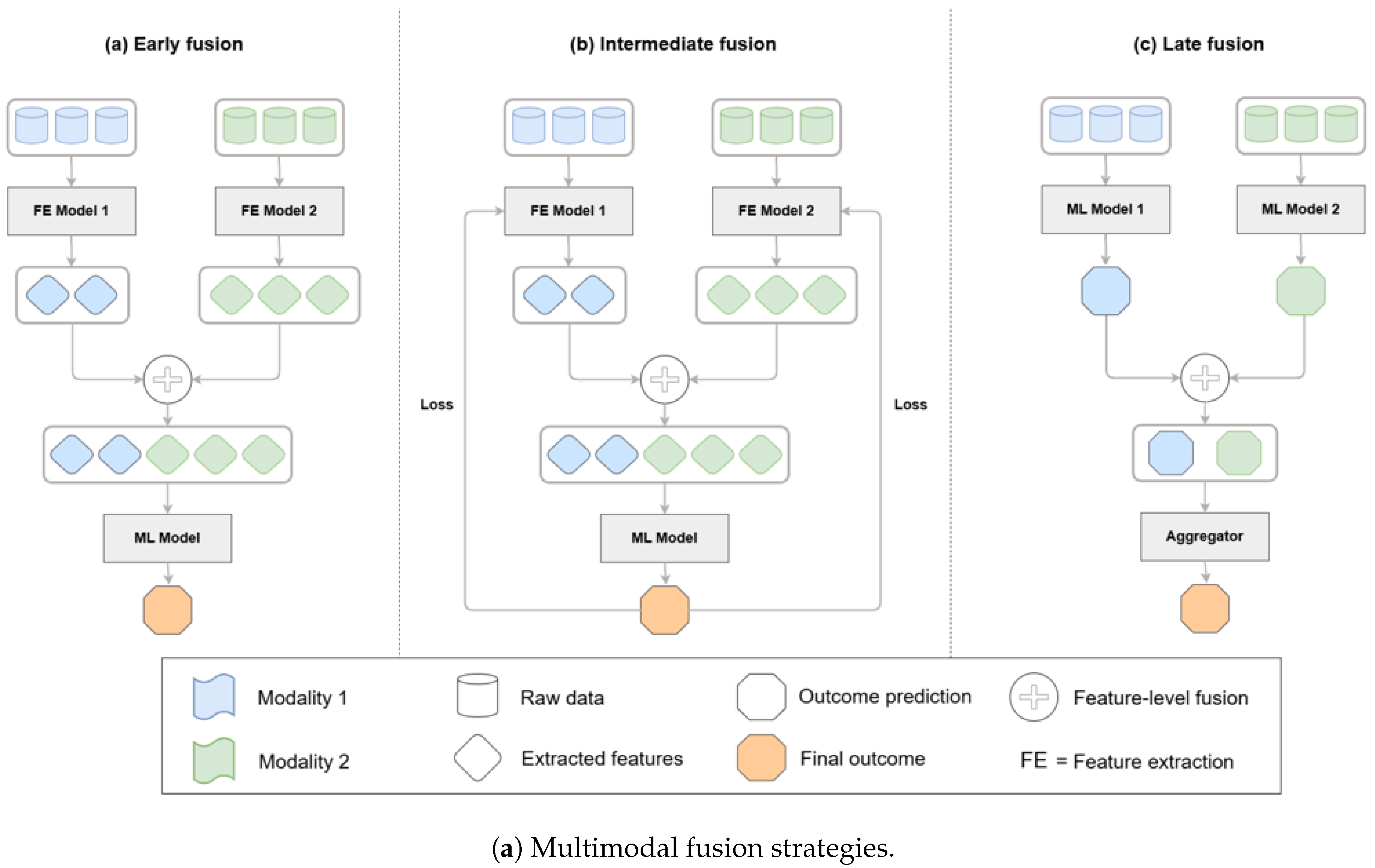

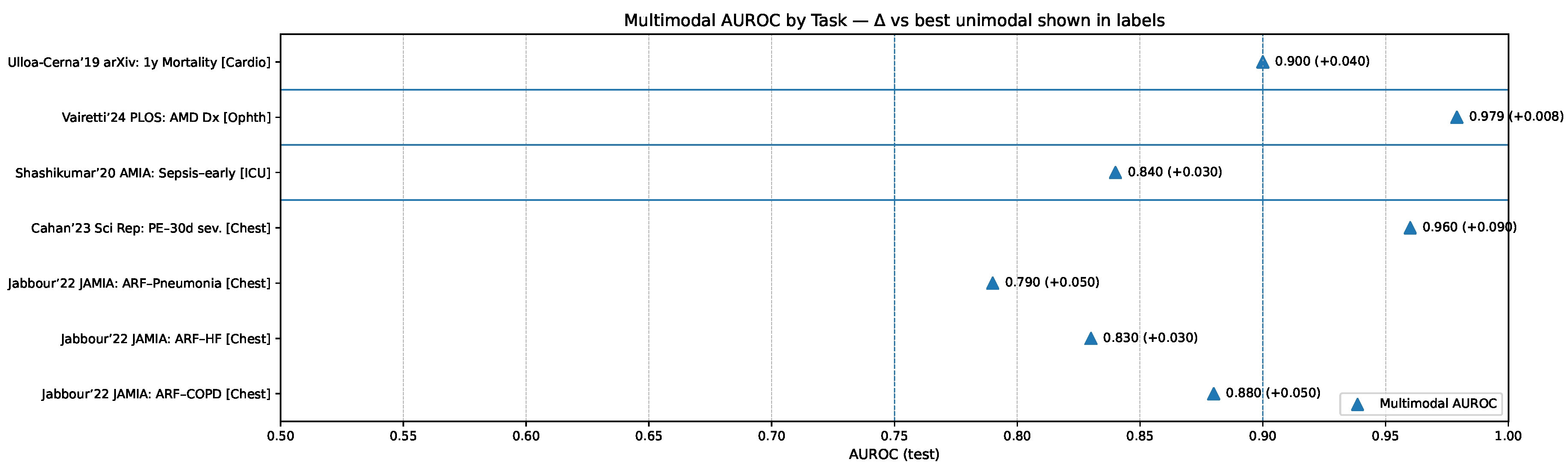

These architectural approaches can be systematically categorized by their fusion strategies, which determine how different modalities are combined within a model. As illustrated in

Figure 6, fusion can occur at the feature level (early fusion), within latent representations (intermediate fusion), or at the decision level (late fusion). Hybrid strategies that combine feature- and decision-level integration are also increasingly applied in biomedical AI, balancing the advantages of deep integration with practical considerations of efficiency and interpretability [

47,

48].

- 3.0.3.

Unification Approach

Unified models represent the most ambitious paradigm, in which a single holistic model is trained to simultaneously ingest and integrate diverse modalities—including medical imaging, textual reports, genomics, and structured clinical data—within a shared representational framework. These systems rely on advanced architectural designs and complex attention mechanisms to achieve deep cross-modal learning, enabling robust internal representations that capture intricate relationships across data types. For example, a unified multimodal transformer may concurrently analyze radiological images, genomic profiles, and clinical notes to produce a diagnostic assessment enriched by highly integrated insights [

29]. This design excels in capturing complex interdependencies that simpler approaches may miss, while also streamlining the analytical pipeline by reducing reliance on external modules, thereby improving overall coherence and reliability of outputs. However, unified models are computationally intensive, demanding substantial GPU resources and access to expansive, well-curated multimodal datasets. Their training is challenging, as performance must be carefully balanced across heterogeneous modalities, and risks such as overfitting or reduced generalization to real-world clinical variability remain significant obstacles. Despite these challenges, unified models hold the greatest promise for uncovering novel clinical insights and supporting deeply integrated diagnostic reasoning in multimodal healthcare applications.

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of multimodal fusion strategies—early/feature-level, intermediate/latent, late/decision-level—and hybrid patterns; biomedical fusion reviews and case studies detail these patterns and their performance trade-offs in practice [

47,

48,

52].

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of multimodal fusion strategies—early/feature-level, intermediate/latent, late/decision-level—and hybrid patterns; biomedical fusion reviews and case studies detail these patterns and their performance trade-offs in practice [

47,

48,

52].

3.1. Comparative Evaluation of Multimodal LLM Strategies

The comparative evaluation of multimodal large language model (LLM) design strategies highlights distinct strengths and limitations that influence their suitability for different clinical contexts (

Table 3). Unified models generally demonstrate superior performance in tasks requiring deeply integrated reasoning across heterogeneous modalities, leveraging their ability to capture complex interdependencies between imaging, textual, and structured clinical data. However, tool-use and grafting approaches can outperform unified systems in scenarios where specialized domain expertise, modular flexibility, or rapid iterative updates are required. Tool-use strategies excel by orchestrating validated external expert modules—such as convolutional networks for radiology—providing flexibility and high domain accuracy, albeit with challenges such as latency, dependency management, and only superficial integration [

38,

56]. Grafting approaches, by embedding pre-trained encoders for different modalities into an LLM backbone, deliver balanced performance and efficient use of computational resources, making them attractive for clinical settings where moderate multimodal integration is sufficient. Yet, their limited depth of cross-modal reasoning and redundancy across modality-specific representations restrict their scalability. In contrast, unified models streamline the diagnostic pipeline by training a single architecture across modalities, offering deep cross-modal reasoning and holistic insights, but at the expense of computational cost, complex training requirements, and higher risk of overfitting [

50]. Interpretability further distinguishes these strategies: tool-use approaches provide clearer transparency regarding which module contributes to a decision, while unified models, though powerful, often deliver more opaque reasoning processes that can hinder clinician trust and regulatory acceptance.

The relative diagnostic value of these paradigms is further illustrated in

Figure 8, which presents multimodal AUROC performance across representative clinical tasks compared against the best unimodal comparators. These results underscore that unified models tend to yield the largest gains in contexts requiring deep cross-modal reasoning, while tool-use and grafting strategies retain significant value in specialized or resource-constrained settings where modularity, interpretability, or efficiency take precedence.

Figure 7.

Multimodal AUROC by clinical task with per-bar callouts indicating the margin over the best unimodal comparator; exemplars include chest radiograph+EHR for acute respiratory failure [

51], CT+EHR for pulmonary embolism detection and 30-day risk [

52,

53], multimodal sepsis detection [

54], and multimodal ophthalmic diagnosis [

55].

Figure 7.

Multimodal AUROC by clinical task with per-bar callouts indicating the margin over the best unimodal comparator; exemplars include chest radiograph+EHR for acute respiratory failure [

51], CT+EHR for pulmonary embolism detection and 30-day risk [

52,

53], multimodal sepsis detection [

54], and multimodal ophthalmic diagnosis [

55].

3.2. Specialization and Generalization Trade-offs

An important dimension in the design of multimodal generative AI systems is the balance between specialization and generalization, as each orientation carries distinct advantages and trade-offs for clinical practice. Specialized models are typically optimized for narrowly defined diagnostic tasks, achieving high accuracy and strong domain-specific interpretability. Such models excel in targeted applications like oncology, where precision and transparency are critical for tasks such as cancer diagnosis or prognosis prediction [

33,

38]. In contrast, generalized models offer broad applicability across diverse clinical scenarios, from primary care to emergency medicine, enabling versatility in settings that require rapid, adaptable diagnostic support. However, this breadth comes with potential reductions in peak performance compared to specialized counterparts [

29]. These trade-offs extend beyond performance to encompass interpretability, computational requirements, and deployment complexity. Specialized systems are often easier to interpret, require fewer computational resources, and can be more straightforward to deploy within narrowly defined workflows. By contrast, generalized models demand greater computational infrastructure, pose challenges in explaining complex multimodal reasoning across varied domains, and require more intricate integration into heterogeneous clinical workflows [

45,

57]. The comparative characteristics of these two design orientations are summarized in

Table 4, which outlines their respective strengths, limitations, and implications for clinical implementation.

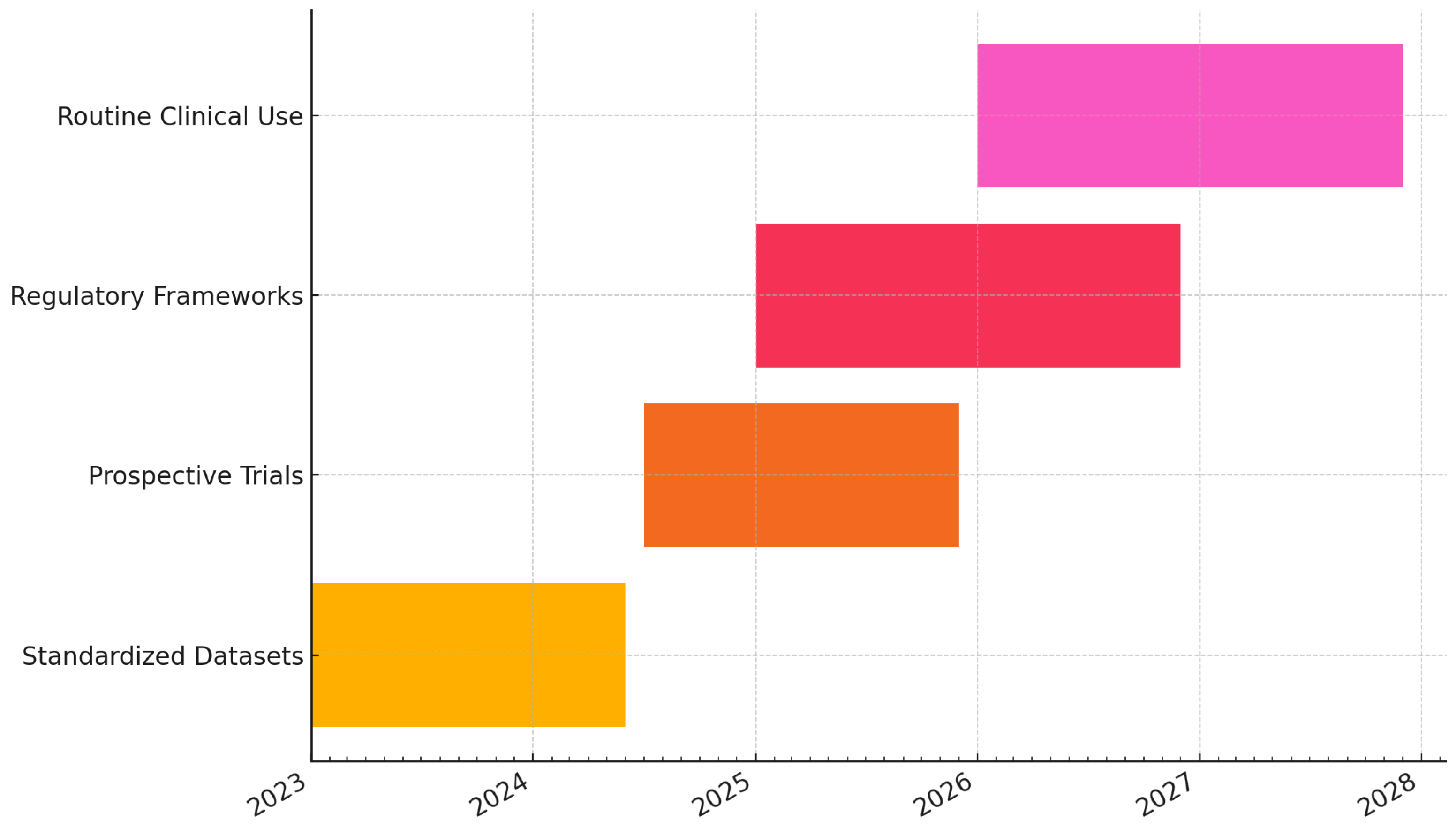

3.3. Future Directions and Research Priorities

Moving forward, advancing multimodal generative AI in diagnostics requires systematically addressing ongoing technical, ethical, and regulatory challenges. Improving interpretability remains a top priority, as clinicians must be able to trust and understand the reasoning behind AI-assisted decisions in high-stakes clinical contexts. Strategies such as federated learning and transfer learning will be essential for managing data scarcity, enabling institutions to collaborate without compromising patient privacy while broadening the representativeness of training datasets. Equally important is the development of robust validation frameworks, including large-scale prospective clinical trials, to demonstrate reproducibility and generalizability across diverse patient populations. Hybrid approaches that integrate aspects of tool-use, grafting, and unification may offer a pragmatic balance, combining modularity and efficiency with deeper integration, thereby maximizing clinical utility. Emphasis on causal learning, explainable AI methods, and standardized benchmarking datasets will be vital to achieving regulatory acceptance and facilitating widespread clinical adoption [

29,

58]. In conclusion, careful consideration of design strategies, performance trade-offs, and practical implementation challenges is necessary for translating multimodal generative AI into meaningful clinical applications, ensuring improvements not only in diagnostic accuracy but also in workflow efficiency and patient outcomes.

4. Clinical Applications of Multimodal Generative AI: Radiology, Pathology, Dermatology, and Ophthalmology

Multimodal generative artificial intelligence (AI) has shown significant potential to revolutionize medical diagnostics across various specialties by integrating diverse data sources and enhancing clinical decision-making. This section reviews prominent clinical applications, capabilities, comparative benefits, and existing challenges of multimodal AI within radiology, pathology, dermatology, and ophthalmology.

4.1. Radiology Applications

Radiology has embraced multimodal AI extensively, integrating imaging data (CT, MRI, PET) with electronic health records (EHR) and clinical notes to achieve improved diagnostic accuracy and streamlined workflows. Multimodal deep learning approaches have demonstrated superior diagnostic capabilities compared to traditional, unimodal methods, notably in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, a multimodal classifier combining FDG-PET and MRI achieved enhanced diagnostic accuracy in Alzheimer’s disease classification, leveraging complementary imaging modalities to improve sensitivity and specificity [

31]. Moreover, the integration of vision-language models facilitates tasks such as visual question answering (VQA) and automated report generation from imaging data, significantly improving the efficiency and interpretability of radiological workflows [

25]. The ROCO (Radiology Objects in COntext) dataset exemplifies the utility of multimodal benchmarks, offering comprehensive data for developing and validating models capable of tasks such as radiographic image captioning and text-conditioned image retrieval. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in data quality, model interpretability, and integration within existing clinical systems. Large-scale validation and regulatory approval processes also represent significant hurdles for practical implementation [

44,

59].

4.2. Pathology Applications

In pathology, multimodal AI systems that integrate histopathology images, genomic data, and textual clinical information have significantly advanced precision diagnostics and personalized treatment planning. The PathChat model is a notable example, combining a specialized pathological image encoder with a language model, achieving high diagnostic accuracy (up to 89.5%) on expert-curated multimodal tasks, significantly surpassing single-modality systems [

33]. Similarly, the CONCH model demonstrates potential for rare disease diagnostics, utilizing large-scale multimodal datasets for zero-shot pathology classification [

33].

PathVQA and related visual question answering datasets support the training and evaluation of AI systems in pathology, testing their ability to integrate visual and textual diagnostic reasoning. Yet, interpretability and usability remain significant challenges; black-box nature and limited transparency of complex models hinder clinician trust and acceptance. Efforts such as explainable AI (XAI) methods (e.g., attention maps, SHAP values) and federated learning approaches for privacy-preserving collaboration across institutions aim to address these barriers [

60,

61].

4.3. Dermatology Applications

Dermatology benefits from multimodal generative AI through enhanced diagnostic accuracy in skin lesion classification and early detection of skin cancers by integrating dermatoscopic images, clinical images, and patient metadata. Multimodal deep learning models demonstrate superior performance to unimodal approaches, particularly in distinguishing malignant from benign lesions, reducing unnecessary biopsies, and improving overall diagnostic confidence [

34,

37]. Conversational AI capabilities further improve patient-provider communication, aiding patients in understanding complex medical conditions and treatment options through accessible, natural-language explanations of diagnostic findings and management strategies [

35].

Generative AI techniques address data scarcity by creating realistic synthetic dermatological images, supporting model training and educational data generation for rare conditions. Despite these strengths, data bias, model interpretability, and integration into clinical workflows present challenges, demanding continued development of standardized data protocols, rigorous validation, and advanced interpretability methods [

35].

4.4. Ophthalmology Applications

Ophthalmology has rapidly adopted multimodal AI to improve diagnostic accuracy and disease monitoring, particularly in diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration. Multimodal generative AI models integrating fundus photographs, OCT scans, and clinical records demonstrate enhanced diagnostic precision and disease progression prediction compared to single-modality analyses, achieving notable area-under-curve (AUC) scores exceeding 0.80 [

36,

37]. These systems facilitate earlier and more accurate diagnosis, potentially improving patient outcomes significantly.

Synthetic image generation capabilities further augment training datasets and aid medical education. However, practical implementation challenges include data standardization, model interpretability, clinical workflow integration, and ethical considerations regarding synthetic data use and privacy compliance [

40,

42].

4.5. Comparative Analysis Across Specialties

A comparative evaluation (Table ??) highlights varying degrees of adoption, effectiveness, and challenges across radiology, pathology, dermatology, and ophthalmology. Radiology and pathology have experienced relatively greater adoption due to established digital data frameworks and imaging standardization. Dermatology and ophthalmology are swiftly advancing, leveraging recent digitization and generative AI techniques. Shared challenges across specialties include data integration complexity, interpretability concerns, data quality and bias risks, and regulatory hurdles. Standardized data protocols, enhanced model interpretability methods, and robust validation frameworks are critical for overcoming these barriers.

4.6. Future Directions and Clinical Integration

Future multimodal generative AI research should prioritize addressing these shared challenges through advanced interpretability techniques, federated learning frameworks for privacy preservation, standardized data protocols, and rigorous prospective clinical validation. Emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers, clinicians, and regulators will be crucial for successful clinical translation. Developing robust governance and evaluation standards, alongside continuous monitoring and recalibration of AI models, will ensure sustained accuracy and clinical relevance across diverse patient populations and healthcare settings.

In summary, multimodal generative AI offers profound transformative potential across radiology, pathology, dermatology, and ophthalmology, promising significant improvements in diagnostic precision, personalized care, and clinical workflow efficiency. However, careful management of data quality, ethical considerations, model interpretability, and clinical integration barriers is essential to fully realize the clinical impact of these powerful diagnostic technologies.

10. Conclusion and Strategic Priorities for Multimodal Generative AI in Clinical Diagnostics

Multimodal generative artificial intelligence (AI) represents a transformative opportunity for clinical diagnostics, holding immense promise to significantly enhance patient care, diagnostic accuracy, and healthcare efficiency. Realizing this potential, however, necessitates addressing critical clinical, research, ethical, and regulatory priorities. This call to action highlights the essential areas of strategic focus required for responsible adoption and optimal utilization of multimodal generative AI technologies in clinical practice.

10.1. High-Priority Clinical Domains

Immediate clinical priorities span diverse medical fields where multimodal AI integration could substantially enhance diagnostic capabilities and patient outcomes. Oncology stands out as a prime area, where integration of imaging, pathology, genomic profiles, and clinical histories offers the potential to revolutionize early cancer detection, precise characterization, personalized treatment strategies, and continuous therapeutic monitoring [

38]. Neurology, cardiology, rare disease diagnostics, and emergency medicine also represent priority areas where multimodal data integration can significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy, timely interventions, and patient management through comprehensive analyses of imaging, electrophysiological, clinical, and genomic data [

27,

33,

40].

10.2. Strategic Research Priorities

Advancing multimodal generative AI necessitates targeted research in several critical domains:

10.3. Ethical and Regulatory Frameworks

Implementing multimodal generative AI requires rigorous ethical and regulatory frameworks addressing responsibility, fairness, transparency, and interpretability. Clear delineation of roles among clinicians, developers, and regulators is critical for addressing liability concerns associated with AI-driven diagnostics [

58]. Ensuring fairness and equity involves proactive monitoring and mitigation of biases inherent in datasets and algorithms, promoting equitable healthcare access and outcomes [

29]. Transparency in AI decision-making processes, supported by robust XAI methodologies, is essential to building clinician trust and facilitating regulatory compliance. Internationally harmonized regulatory guidelines should provide agile oversight frameworks that balance innovation with patient safety, addressing both current technological capabilities and future advancements [

29,

58].

10.4. Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Stakeholder Engagement

Realizing the potential of multimodal generative AI requires interdisciplinary collaboration involving clinical researchers, AI specialists, data scientists, biomedical informaticians, ethicists, regulators, healthcare administrators, and patient advocacy groups. This diverse collaboration fosters comprehensive solutions to technical, ethical, and operational challenges. Active engagement of patients and advocacy communities ensures that AI tools align with patient-centered priorities and ethical standards, promoting transparency, consent, and equitable healthcare delivery.

10.5. Strategic Actions for Overcoming Barriers and Accelerating Adoption

To accelerate responsible integration and adoption of multimodal generative AI, several strategic actions are recommended:

Establish Clear Regulatory Pathways: Collaborate with regulatory bodies to develop explicit validation and approval frameworks, streamlining the translation of AI technologies from research to clinical practice.

Invest in Computational Infrastructure: Support healthcare institutions in building robust computational platforms capable of integrating and deploying complex multimodal AI models efficiently.

Implement Comprehensive Training Programs: Educate clinicians and healthcare professionals in effectively using AI-assisted diagnostic tools, emphasizing practical application, interpretability, and ethical considerations.

Promote Open Science and Data Sharing Initiatives: Encourage international sharing of algorithms, models, and standardized datasets to foster reproducible, collaborative, and transparent AI research.

Conduct Cost-effectiveness and Impact Studies: Demonstrate the economic and clinical value of multimodal AI to drive reimbursement and justify widespread clinical implementation.

Develop Standardized Best Practices and Ethical Guidelines: Establish international guidelines and best practices for the responsible development, validation, and clinical deployment of multimodal AI systems.

Engage Public and Community Dialogues: Foster ongoing communication with patients and communities to build trust, address concerns, and ensure transparency around AI usage in healthcare settings.

10.6. Summary of Strategic Priorities and Impact Outlook

A structured summary of strategic priorities, stakeholders, and recommended actions for advancing multimodal generative AI in clinical diagnostics is presented in

Table 12, highlighting immediate clinical priorities, focused research initiatives, key collaborative stakeholders, and targeted strategic actions essential for successful adoption and impact.

Multimodal generative AI holds extraordinary promise for reshaping clinical diagnostics, offering substantial improvements in diagnostic accuracy, personalized patient care, clinical efficiency, and health system optimization. Yet, realizing this potential demands focused action across clinical, research, ethical, and regulatory domains. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, strategic investment, comprehensive validation, proactive ethical governance, and international standardization efforts, multimodal generative AI can be harnessed responsibly to significantly enhance patient outcomes and healthcare delivery, ultimately advancing the goal of precision medicine in clinical diagnostics.