Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The SLR Protocol

2.1. Research Questions

- What hardware components should SR be equipped with?

- What software should SR be equipped with?

- What future research directions are suggested for SR, and what gaps have been identified in the reviewed literature?

2.2. Exclusion & Inclusion Criteria

- The papers must be published between 2014-2024.

- The papers are written in English.

- The papers are the results of searching in Google Scholar, Google search engine, and Semantic Scholar.

- Exclude duplicate papers that contain redundant information.

- Papers must be four pages or longer to exclude works lacking scientific methodology and sufficient detail.

- Papers that are inaccessible are excluded.

- Exclude papers that do not contribute to the research after reviewing them.

2.3. Quality Assessment Criteria

-

Research Design & Methodology:* Clearly defined research objectives: Does the paper outline its contributions and research goals?* Description of methodology: Is the development or experimental methodology sufficiently described?*Software and hardware validation: Have the suggested software and hardware components undergone adequate testing and validation?

-

Technical Contribution:* Innovation and novelty: Does the paper offer new software or hardware solutions or enhancements?* Technical depth: Is the technical content rigorous and detailed enough?

-

Experimental Evaluation:* Experiments: Are they appropriate and well-designed?

-

Relevance and Impact:*Swarm robotics relevance: To what extent does the work relate to the field of swarm robotics?*Can the proposed solution be practically implemented?

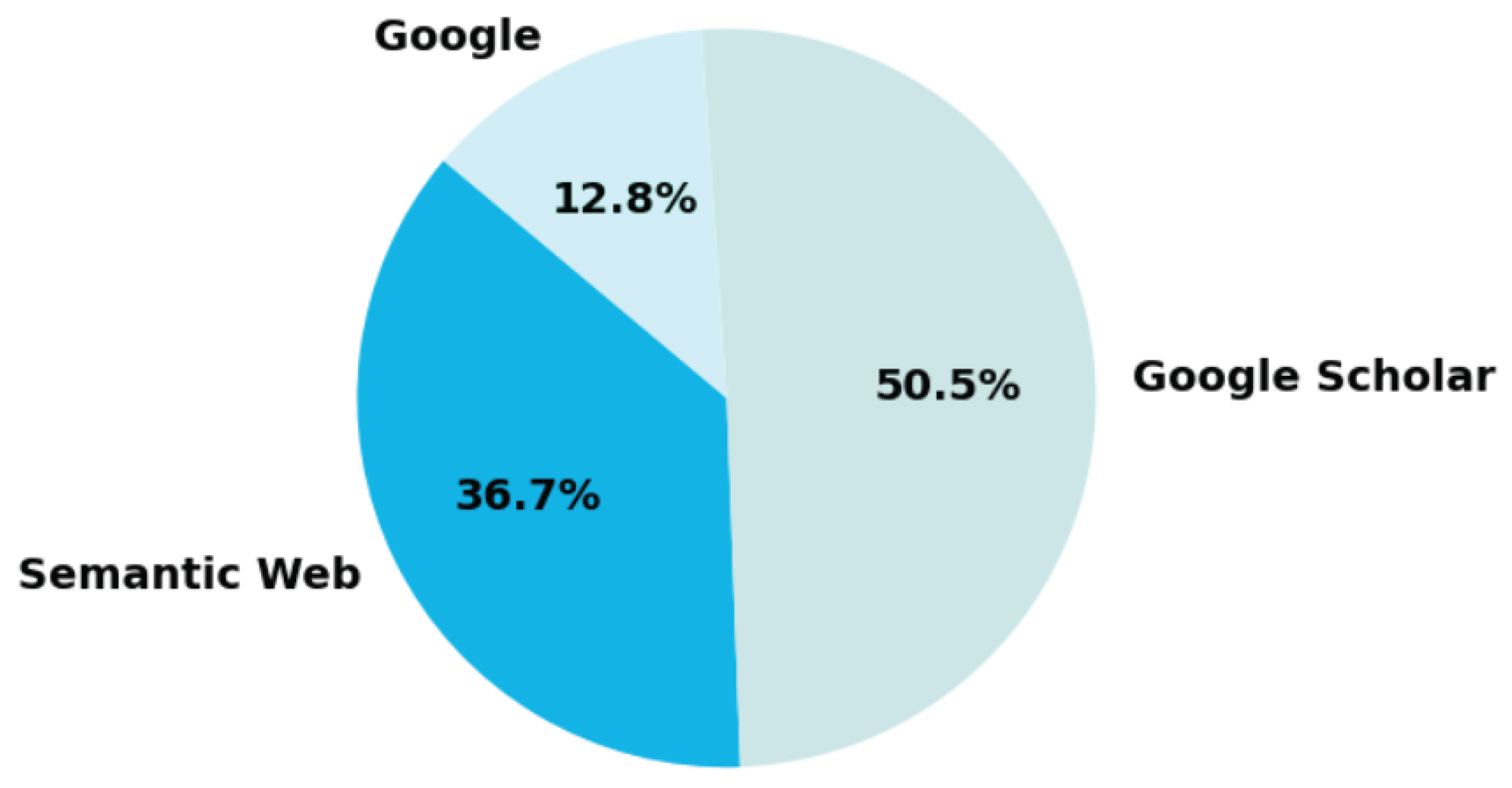

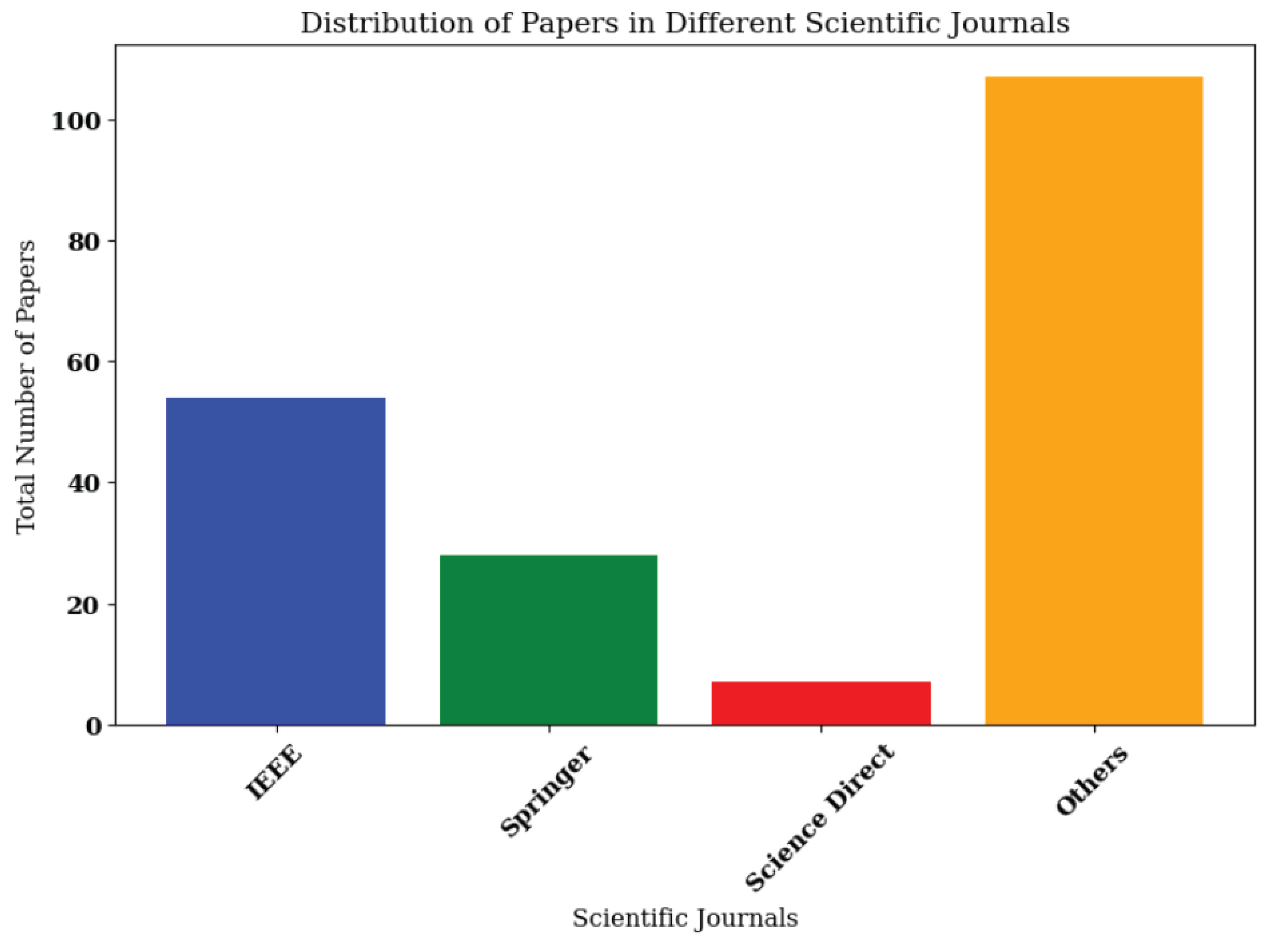

2.4. Execution

- The results are:

- 99 papers –> Google Scholar.

- 72 papers –> Semantic scholar.

- 25 papers –> Google search engine.

- 196 paper–> total.

- After applying the criteria outlined in subsections B and C, 40 out of 196 papers met the requirements, representing 20.41% of the total.

3. Hardware Design

3.1. Sensors

- sensor output signal.

- x is the distance of the obstacle.

- is the angle of incidence with the surface.

- includes several parameters, such as the reflectivity coefficient, output power of emitted IR, and sensor sensitivity.

- is the amplifier’s offset value plus the effect of ambient light.

3.2. Actuators and Locomotion Mechanisms

3.3. Communication And Networking

- Communication Distance Capability: The X-Bee modules have more extensive communication range in comparison to the Bluetooth Bee modules.

- Data Transmission Speed: The PmodWiFi module, when mixed with the SPI interface, facilitates a higher rate of data transfer comparing to the X-Bee and Bluetooth Bee modules.

- Energy Consumption: Each module exhibits distinct power requirements.

-

Interaction via Communication:

- Short-range wireless transmission: This often involves the use of radio frequency (RF) modules like Zigbee or Bluetooth.

- Infrared broadcasting communication: IR transceivers enable robots to exchange information using infrared light.

- LEDs for information indication: Robots can use LEDs on board to let other robots know what state they’re in or other information.

-

Interaction via Sensing:

- Sonar: Ultrasonic sensors help robots to detect the distance and direction of nearby robots without direct communication.

-

Interaction via the Environment:

- Virtual pheromones: This method uses the environment to "remember" things, just like ants do with pheromones. The actual implementation can be different; for example, robots can use wireless communication to keep track of virtual pheromone information.

3.4. Power Source

- Robot size and weight: Smaller robots require smaller, lighter batteries.

- Power consumption: Robots with more sensors, actuators, and processing power need higher-capacity batteries.

- Mission duration: Longer missions necessitate batteries with longer run times.

4. Software Design

- Modular design: separating robot control "body", communication "network", and swarming behavior "behavior" into distinct classes.

- Platform agnostic : different robots can be integrated by creating platform-specific body classes (eBot and e-puck examples given).

- Communication flexibility and Enables heterogenity.

- Provides "MockBody" and "MockNetwork" classes for simulation and rapid prototyping of swarm algorithms without real hardware. And it is Python-based for ease of development.

| Platform / Architecture | Key Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SwarmUS | ROS + Buzz integration, modular, real-to-simulation continuity | Requires experience with multiple tools | Advanced real-world hybrid deployments | [15] |

| Aquatic SR System | Real-time Java control, low-cost Raspberry Pi, user-friendly interface | Limited modularity and scalability | Low-cost aquatic swarms with basic missions | [21] |

| Zooids | Human-swarm interaction, high-frequency coordination, layered architecture | Limited to tabletop, not scalable for field robots | UI/HCI and real-time swarm interaction studies | [20] |

| Cellulo | Haptic feedback, education-focused, decentralized design | Limited in complexity and application domains | Educational swarm robotics for K–12 or university labs | [19] |

| Robotarium | Safety mechanisms, remote testing, real-to-sim pipeline | Limited hardware control; depends on centralized server | Cloud-based experiments, large-scale coordination testing | [28] |

| HeRo | Simple Arduino+ROS setup, cost-effective, modular firmware | Minimal swarm-specific middleware | Low-cost teaching and entry-level experimentation | [36] |

| Waffle (AutoMoDe) | Modular, automatically optimized control under constraints | Not flexible beyond mission-specific designs | Automated, constraint-aware controller generation | [16] |

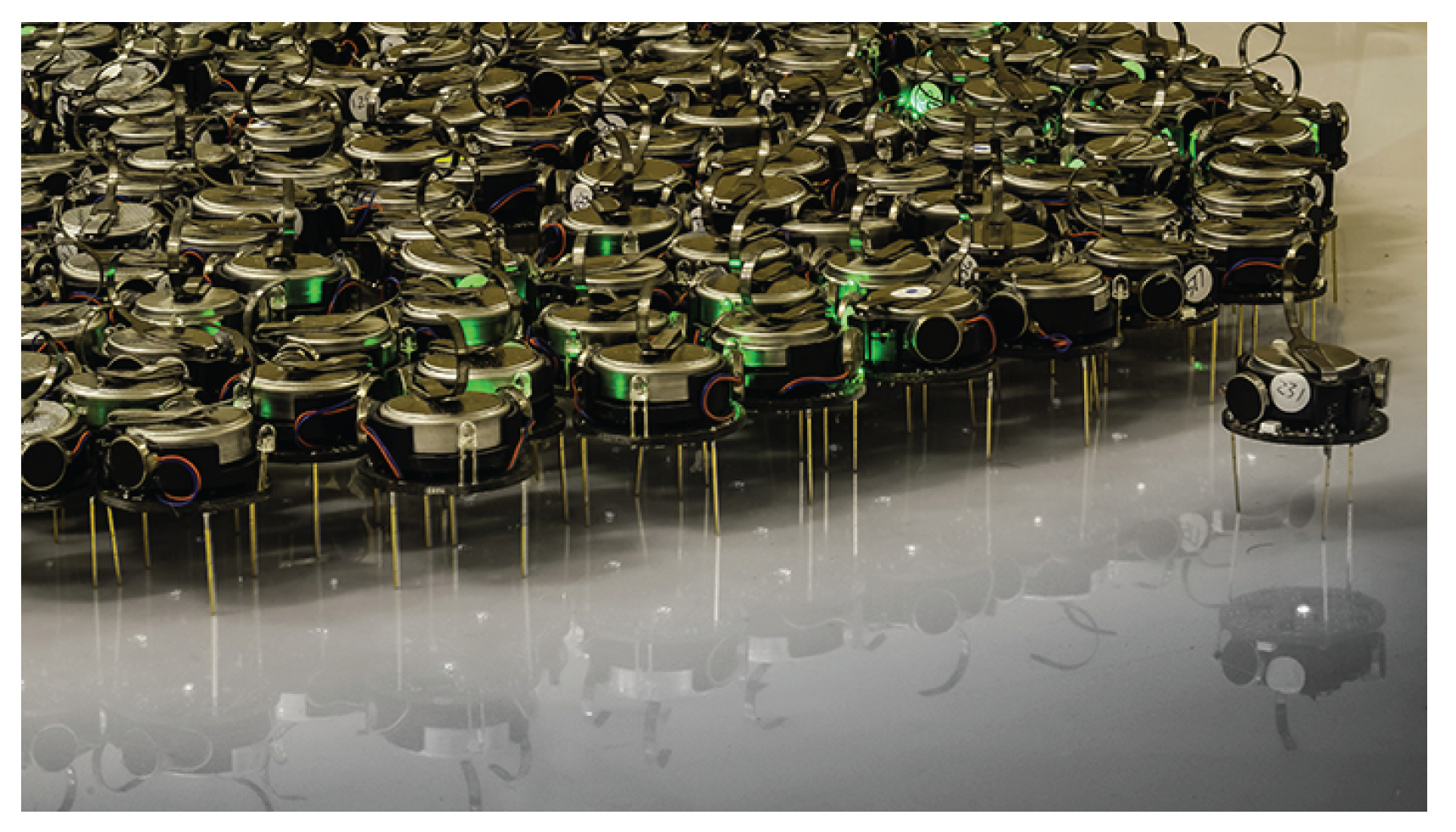

| Kilobots | Extremely scalable, low-cost, decentralized | Lacks computation and sensor diversity | Self-organization studies and large-scale swarm behavior | [42] |

| AutoMoDe-Chocolate | PFSM + optimization with structured modules | Limited expressiveness for novel tasks | Comparative benchmarking of automatic vs manual design | [10] |

| AutoMoDe-Vanilla | Simple PFSM composition; human-constrained design space | Less optimal than Chocolate or Maple | Baseline for automated swarm control | [56] |

| AutoMoDe-Maple | Modular behavior trees, automatic tuning | Higher complexity, new method under exploration | Rich control strategies for evolving swarms | [57] |

| Buzz | Swarm-specific DSL, stigmergy, and situated communication | Steep learning curve; lacks IDE tools | Flexible programming of heterogeneous swarms | [46] |

| SwarmTalk | Lightweight communication API; cross-platform abstraction | Middleware only; lacks behavioral logic | Efficient communication layer for custom control stacks | [45] |

| Pyswarming | Pythonic interface, built-in algorithms, fast prototyping | Limited to simulation environments | Teaching, prototyping, and algorithm development | [48] |

| Marabunta | Modular Python framework, supports heterogeneity and simulation | Requires manual platform adaptation | Platform-agnostic simulation + physical deployment bridge | [54] |

| PILOT | Actor-oriented toolkit for ML and distributed control | Limited real-world validation; documentation lacking | Research in ML-integrated distributed swarm programming | [50] |

| Swarmie (NASA) | Modular ROS architecture, formation control, inter-process messaging | Application-specific (lunar mining); limited public toolkit | Engineering-oriented missions, e.g., resource foraging | [51] |

| Property-Driven Design | Formal methods; uses PCTL and model checking | High complexity; early-stage usability | Safety-critical swarm verification with provable guarantees | [52] |

| ROS-Heterogeneous Framework | Five-mode abstraction, modular, ROS-based | Custom-built; limited general documentation | Unified control of heterogeneous multirobot teams | [53] |

| EvoStick (Neural Net) | Evolves FFNNs using evolutionary algorithms | Prone to overfitting; lacks interpretability | Optimizing reactive swarm behavior from scratch | [56] |

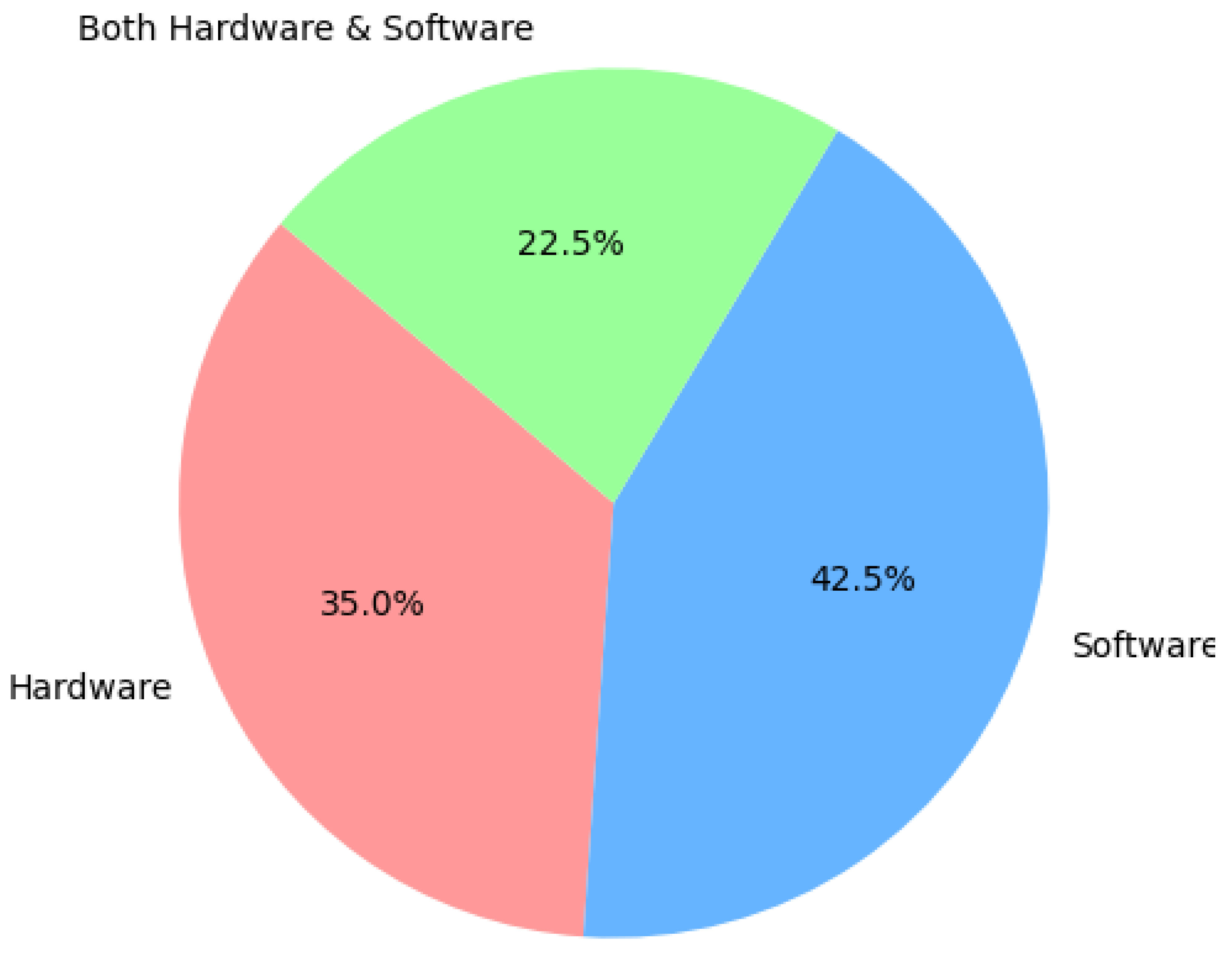

5. Answering the Research Questions

5.1. What Are the Hardware Components That SR Should Be Equipped with?

- Hardware Design: Focuses on choosing the appropriate actuators, sensors, communication modules, and power sources based on the specific environment and task.

- Software Design: Emphasis is placed on developing software that enables emergent swarm behavior inspired by natural swarm intelligence algorithms. The software needs to manage the robot actions, communication, and coordination.

- Actuators: DC motors, servo motors, wheels, legs, propellers, vibration motors, and specialized mechanisms for buoyancy (in aquatic robots).

- Sensors: Infrared (IR) sensors, ultrasonic sensors, cameras, GPS, chemical sensors, temperature sensors, humidity sensors, and touch sensors.

- Communication: Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, ZigBee, RFID, IR, and even electric field detection in aquatic robots.

- Power Sources: Rechargeable batteries (often LiPo), solar panels, and charging systems.

- Environment: Different environments require specialized actuators and sensors.

- Task: The specific task influences the hardware selection.

- Economic Constraints: Budgetary limitations may dictate the choice of more affordable components.

5.2. What Software Should SR Be Equipped with?

- Application Layer: Software that shapes the swarm behaviors and targets using task specific algorithms like Behavior trees and finite state machines.

- Inter- Communication Layer: Software that Facilitate information exchange and coordination using protocols like WiFi, Bluetooth and ZigBee.

- Control Layer: Software that process the sensor data and control actuators.

- Simulation and development Layer: For testing the robots before the real world deployment like the mentioned Gazebo simulator, also frameworks like Robot operating system (ROS), Buzz and AutoMoDe to programme the SR and the modular software design to ease the development process.

- Hardware Abstraction Layer: Provide interfaces for human users to control and monitor the swarm like HiveAR for real time interaction.

5.3. What Future Explorations Are Suggested for SR, and What Gaps Have Been Identified in the Reviewed Papers?

- Standardization: The most significant gap is the lack of a universal design methodology or standardized hardware platform. This makes it difficult to compare results, share code, or easily migrate projects between platforms.

- The Economic Constraints: The need for low-cost SR is emphasized, but few papers provide detailed comparisons of different cost-effective hardware options. More research on balancing performance with cost is needed. However, the paper by Salman et al., previously reviewed, presents waffle platform, a significant advancement in automatic design methods for SR by addressing the simultaneous creation of hardware and control software under economic constraints.

- Self-Repair and Robustness: There isn’t much talk about how to make SR that are strong and can fix themselves in tough situations.

- Automatic Design Methods: While automatic design methods show promise, they are still under development. More research is needed on their effectiveness.

- Environmental Adaptation: The papers mostly look at certain environments, such as ground, aquatic, and aerial environments. We need to do more research on how to make SR that can work in a variety of environments that are always changing.

- Communication Protocols: There’s a need for standardized, efficient, and robust communication protocols for SR. Existing protocols often lack scalability and flexibility.

- Swarm Behavior Modeling: Developing robust models and tools for predicting and analyzing swarm behavior is important for designing effective SR.

- Real-World Deployment: Many papers focus on simulation or small-scale experiments.

- Human-Swarm Interaction: While some papers mention interfaces, more research is needed on designing intuitive and user-friendly interfaces that enable effective human control and management of large-scale swarms.

- Ethical Considerations: The ethical implications of using SR are rarely discussed.

6. Conclusion

References

- G. Beni, "From swarm intelligence to swarm robotics," in International Workshop on Swarm Robotics, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004, pp. 1–9.

- E. Şahin, "Swarm robotics: From sources of inspiration to domains of application," in International workshop on swarm robotics, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004, pp. 10–20.

- P. G. F. Dias, M. C. Silva, G. P. Rocha Filho, P. A. Vargas, L. P. Cota, and G. Pessin, "Swarm robotics: A perspective on the latest reviewed concepts and applications," Sensors, vol. 21, no. 6, p. 2062, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tan, Handbook of research on design, control, and modeling of swarm robotics. IGI global, 2015.

- S. J. Russell and P. Norvig, Artificial intelligence a modern approach. London, 2010.

- J. P. Kelly and I. H. Osman, Meta-heuristics: theory and applications. Kluwer Norwell, 1996.

- C.-W. Tsai and M.-C. Chiang, Handbook of metaheuristic algorithms: from fundamental theories to advanced applications. Elsevier, 2023.

- H. T. Jongen, K. Meer, and E. Triesch, Optimization theory. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2004.

- E. Şahin, S. Girgin, L. Bayindir, and A. Turgut, "Swarm robotics," in Swarm intelligence: introduction and applications, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 87–100.

- A. Francesca, et al., "AutoMoDe-Chocolate: Automatic design of control software for robot swarms," Swarm Intelligence, vol. 9, no. 2-3, pp. 125-152, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Tello-Rodríguez and L. Torres-Treviño, "Characterization of Environment Using the Collective Perception of a Smart Swarm Robotics Based on Data from Local Sensors," in Smart Technology: First International Conference, MTYMEX 2017, Monterrey, Mexico, May 24–26, 2017, Proceedings, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 133–140.

- J. Jesson, F. M. Lacey, and L. Matheson, Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Pati and L. N. Lorusso, "How to write a systematic review of the literature," HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 15–30, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Nedjah and L. S. Junior, "Review of methodologies and tasks in swarm robotics towards standardization," Swarm and Evolutionary Computation, vol. 50, p. 100565, 2019. [CrossRef]

- É. Villemure, P. Arsenault, G. Lessard, T. Constantin, H. Dubé, L.-D. Gaulin, X. Groleau, S. Laperrière, C. Quesnel, and F. Ferland, "Swarmus: An open hardware and software on-board platform for swarm robotics development," arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.02643, 2022.

- M. Salman, A. Ligot, and M. Birattari, "Concurrent design of control software and configuration of hardware for robot swarms under economic constraints," PeerJ Computer Science, vol. 5, p. e221, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Patil, T. Abukhalil, and T. Sobh, "Hardware architecture review of swarm robotics system: Self-reconfigurability, self-reassembly, and self-replication," International Scholarly Research Notices, vol. 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Patil, T. Abukhalil, S. Patel, and T. Sobh, "Ub robot swarm—design, implementation, and power management," in 2016 12th IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA), IEEE, 2016, pp. 577–582. [CrossRef]

- A. Özgür, S. Lemaignan, W. Johal, M. Beltran, M. Briod, L. Pereyre, F. Mondada, and P. Dillenbourg, "Cellulo: Versatile handheld robots for education," in Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2017, pp. 119–127.

- M. Le Goc, L. H. Kim, A. Parsaei, J.-D. Fekete, P. Dragicevic, and S. Follmer, "Zooids: Building blocks for swarm user interfaces," in Proceedings of the 29th annual symposium on user interface software and technology, 2016, pp. 97–109. [CrossRef]

- V. Costa, M. Duarte, T. Rodrigues, S. M. Oliveira, and A. L. Christensen, "Design and development of an inexpensive aquatic swarm robotics system," in Oceans 2016-Shanghai, IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- P. C. M. Bartmess and P. Ernst, "Fast, low-cost swarm robots," Springer, 2018.

- B. Shang, "Hardware variation in robotic swarm and behavioural sorting with swarm chromatography," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southampton, 2017.

- F. Arvin, J. C. Murray, L. Shi, C. Zhang, and S. Yue, "Development of an autonomous micro robot for swarm robotics," in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, IEEE, 2014, pp. 635–640. [CrossRef]

- S. Mintchev, E. Donati, S. Marrazza, and C. Stefanini, "Mechatronic design of a miniature underwater robot for swarm operations," in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2014, pp. 2938–2943. [CrossRef]

- N. Moustafa, A. Gálvez, and A. Iglesias, "A general-purpose hardware robotic platform for swarm robotics," in Intelligent Distributed Computing XII, Springer, 2018, pp. 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mulgaonkar, G. Cross, and V. Kumar, "Design of small, safe and robust quadrotor swarms," in 2015 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2015, pp. 2208–2215. [CrossRef]

- D. Pickem, P. Glotfelter, L. Wang, M. Mote, A. Ames, E. Feron, and M. Egerstedt, "The robotarium: A remotely accessible swarm robotics research testbed," in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1699–1706. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Patil, M. Y. Upadhye, F. Kazi, and N. Singh, "Multi robot communication and target tracking system with controller design and implementation of swarm robot using arduino," in 2015 International Conference on Industrial Instrumentation and Control (ICIC), IEEE, 2015, pp. 412–416. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Lakshmi and A. Lalitha, "Design and implementation of Arduino based multi robot for target tracking system," 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ç. A. Demir, "Design of a low-cost swarm robotic system for flocking," M.S. thesis, Middle East Technical University, 2019.

- J. McLurkin, A. McMullen, N. Robbins, G. Habibi, A. Becker, A. Chou, H. Li, M. John, N. Okeke, J. Rykowski, et al., "A robot system design for low-cost multi robot manipulation," in 2014 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems, IEEE, 2014, pp. 912–918. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Kim, Z. Kashino, T. Colaco, G. Nejat, and B. Benhabib, “Design and implementation of a millirobot for swarm studies—mroberto," Robotica, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 1591–1612, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Kumar, A. Ravindiran, S. Meganathan, N. O. Roberts, and N. Anbarasi, "Swarm robot materials handling paradigm for solar energy conservation," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 46, pp. 3924–3928, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Bonnet, Y. Kato, J. Halloy, and F. Mondada, "Infiltrating the zebrafish swarm: design, implementation and experimental tests of a miniature robotic fish lure for fish—robot interaction studies," Artificial Life and Robotics, vol. 21, pp. 239–246, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Rezeck, H. Azpurua, and L. Chaimowicz, "Hero: An open platform for robotics research and education," in 2017 Latin American Robotics Symposium (LARS) and 2017 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- B. Shang, R. Crowder, and K.-P. Zauner, "Simulation of hardware variations in swarm robots," in 2013 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, IEEE, 2013, pp. 4066–4071. [CrossRef]

- A. Abuelhaija, A. Jebrein, and T. Baldawi, "Swarm robotics: Design and implementation," International Journal of Electrical & Computer Engineering (2088-8708), vol. 10, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. N. J. E. Jacob, Simplified Robotics: An Illustrative Guide to Learn Fundamentals of Robotics, Including Kinematics, Motion Control, and Trajectory Planning. BPB publications, India, 2022.

- R. Arrick and N. Stevenson, Robot building for dummies. John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- R. S. Pressman, Software engineering: a practitioner’s approach. Palgrave macmillan, 2005.

- M. Rubenstein, A. Cornejo, and R. Nagpal, "Programmable self-assembly in a thousand-robot swarm," Science, vol. 345, no. 6198, pp. 795–799, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Francesca, M. Brambilla, A. Brutschy, L. Garattoni, R. Miletitch, G. Podevijn, A. Reina, T. Soleymani, M. Salvaro, C. Pinciroli, et al., "Automode-chocolate: automatic design of control software for robot swarms," Swarm Intelligence, vol. 9, pp. 125–152, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Hasselmann, "Advances in the automatic modular design of control software for robot swarms: Using neuroevolution to generate modules," Ph.D. dissertation, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Y. Zhang, L. Zhang, H. Wang, F. E. Bustamante, and M. Rubenstein, "Swarmtalk-towards benchmark software suites for swarm robotics platforms," in Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, 2020, pp. 1638–1646.

- C. Pinciroli and G. Beltrame, "Swarm-oriented programming of distributed robot networks," Computer, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 32–41, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Francesca and M. Birattari, "Automatic design of robot swarms: achievements and challenges," Frontiers in Robotics and AI, vol. 3, p. 29, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. M. de Andrade, A. C. Fernandes, and J. S. Sales, "Pyswarming: a research toolkit for swarm robotics," Journal of Open Source Software, vol. 8, no. 89, p. 5647, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Á. Madridano, A. Al-Kaff, P. Flores, D. Martín, and A. de la Escalera, "Software architecture for autonomous and coordinated navigation of uav swarms in forest and urban firefighting," Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 1258, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Akkaya, S. Emoto, and E. A. Lee, "Pilot: An actor-oriented learning and optimization toolkit for robotic swarm applications," in International Workshop on Robotic Sensor Networks, 2015.

- K. A. Stolleis, "Swarming robot design, construction and software implementation," Tech. Rep., 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Brambilla, A. Brutschy, M. Dorigo, and M. Birattari, "Property-driven design for robot swarms: A design method based on prescriptive modeling and model checking," ACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive Systems (TAAS), vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1–28, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Gansari and C. Buiu, "Software system integration of heterogeneous swarms of robots," Journal of Control Engineering and Applied Informatics, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 49–57, 2017.

- M. Chamanbaz, D. Mateo, B. M. Zoss, G. Tokić, E. Wilhelm, R. Bouffanais, and D. K. Yue, "Swarm-enabling technology for multi-robot systems," Frontiers in Robotics and AI, vol. 4, p. 12, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Parker, D. Rus, and G. S. Sukhatme, "Multiple mobile robot systems," Springer handbook of robotics, pp. 1335–1384, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Francesca, M. Brambilla, A. Brutschy, L. Garattoni, R. Miletitch, G. Podevijn, A. Reina, T. Soleymani, M. Salvaro, C. Pinciroli, et al., "An experiment in automatic design of robot swarms: Automode-vanilla, evostick, and human experts," in Swarm Intelligence: 9th International Conference, ANTS 2014, Brussels, Belgium, September 10–12, 2014. Proceedings 9, Springer, 2014, pp. 25–37. [CrossRef]

- J. Kuckling, A. Ligot, D. Bozhinoski, and M. Birattari, "Behavior trees as a control architecture in the automatic modular design of robot swarms," in International conference on swarm intelligence, Springer, 2018, pp. 30–43. [CrossRef]

- K. Hasselmann, F. Robert, and M. Birattari, "Automatic design of communication-based behaviors for robot swarms," in Swarm Intelligence: 11th International Conference, ANTS 2018, Rome, Italy, October 29–31, 2018, Proceedings 11, Springer, 2018, pp. 16–29. [CrossRef]

- L. Williams, "FEATURE: How swarms of robots will revolutionise the construction industry," Aug. 14, 2019. [Online]. Available:https://imechewebresources.blob.core.windows.net/imeche-web-content/images/default-source/default-album/dscf4314_lr1-edit_lr1.jpg?sfvrsn=c438b12_0.

- "HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Distance Sensor." [Online]. Available:https://imechewebresources.blob.core.windows.net/imeche-web-content/images/default-source/default-album/dscf4314_lr1-edit_lr1.jpg?sfvrsn=c438b12_0.

- "Sharp GP2Y0A21YK IR proximity sensor.jpg." [Online]. Available:https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/Sharp_GP2Y0A21YK_IR_proximity_sensor.jpg.

- "Adafruit Standalone 5-Pad Capacitive Touch Sensor Breakout - AT42QT1070 [ADA1362]." [Online]. Available:https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61Go+qnompL._AC_SX522_.jpg.

- "LSM303D 3D Compass and Accelerometer Carrier with Voltage Regulator." [Online]. Available:https://a.pololu-files.com/picture/0J4935.1200.jpg?7d52096304294be12fb09e46e661c656.

- "DC Gear Motor, DC 6V Gear Motor High Torque 1:1000 for Toy Car Model Reduction Gearbox 10/15/20RPM(6V 10RPM)." [Online]. Available:https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61nJ1X1uI5L._SL1001_.jpg.

- "TowerPro SG 90 Micro Servo Motor." [Online]. Available:https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61yfIwAxe0L._SX522_.jpg.

- "EMAX Multicopter motor MT2213 (With Prop1045 Combo) 935KV." [Online]. Available:https://rees52.com/cdn/shop/files/Drone_Multirotor_Motor_combo.png?v=1740738578&width=713.

- "Stepper motor." [Online]. Available:https://stock.adobe.com/dz/images/stepper-motor-of-cnc-linear-axis-drive-of-3d-machine/84747521.

- "ESP8266 WiFi Module." [Online].Available:https://grobotronics.com/images/thumbnails/570/570/detailed/135/ESP8266-01-112.png.

- "RN-42 Bluetooth Module." [Online]. Available:https://media.parallax.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/13151324/30086.png.webp.

- "2.4GHz Wireless Transceiver nRF 24L01." [Online]. Available:https://store.fut-electronics.com/cdn/shop/products/nrf24l01_1024x1024.jpeg?v=1566906321.

- "Pmod WiFi: WiFi Interface 802.11g." [Online]. Available:https://cdn02.plentymarkets.com/qxzolkbuxzfb/item/images/100705/middle/24083-gross.jpg.avif.

| Category | Component (Model/Type) | Function / Usage | Specs (Power, Range, Cost) | Platform(s) / Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensors | GP2Y0A21YK IR Sensor | Obstacle avoidance, range detection | 30–50 mA, 10–80 cm, $10 | S-Bot [29] |

| HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor | Distance measurement, anti-collision | 15 mA, 2–400 cm, $2–5 | UBswarm, Mustafa SR [18,29] | |

| Realsense D400 Camera | Depth sensing, 3D mapping | 1.6 W, USB-powered, $150 | SwarmUS [15] | |

| DS18B20 Temp Sensor | Water temperature sensing | 1 mA, digital, $5 | Aquatic SR (Costa) [21] | |

| AT42QT1070 Touch Sensor | Capacitive human interaction | 2 µA, $1 | Zooids [20] | |

| Actuators | DC Gear Motors (e.g., Solarbotics) | Wheeled movement | 35–150 mA, 3–12V DC | Colias, UBswarm, S-Bot [18,24,29] |

| SG90 Servo Motors | Wheel drive (modified) | 250 mA peak, 5V, $3–5 | HeRo [36] | |

| Piezoelectric Actuators | Micro-scale movement | mW range, low voltage | Kilobot (implied) [25] | |

| Omni-wheel Drive | Holonomic motion | Variable, platform-specific | Cellulo [19] | |

| Propeller Motors (NTM, EMAX) | Aquatic propulsion | 140 W, 11.1V LiPo | Jeff, Costa SR [21,25] | |

| Communication Modules | ESP8266 Wi-Fi | Long-range comms, ROS link | 70–170 mA, 20–50 m, $2–10 | HeRo, GRITSbot [28,36] |

| PmodWiFi (SPI) | High-speed Wi-Fi data | 250 mA, 400 m, $20–30 | UBswarm [31] | |

| nRF24L01+ RF Chip | RF link with PC/server | 15 mA, 800–1000 m, $1–5 | Zooids [20] | |

| RN-42 Bluetooth | App/tablet communication | 15–50 mA, 10–15 m, $10–30 | Cellulo [19] | |

| IR Sensors (Long/Short Range) | Obstacle avoidance, basic comms | 30 mA, 1–5 m, $5–20 | Colias, S-Bot [24,29] | |

| [21] | ||||

| Power Sources | 3.7V Li-Po Battery | Main control and drive power | 600–1200 mAh, USB, $5–15 | Colias, Zooids [20,24] |

| 11.1V Li-Po Pack | High power, aquatic missions | 880 mAh ×8, 120 min | Jeff [25] | |

| Wireless Charging Dock | Automatic recharge | 400 mAh, 40 min runtime | Robotarium (GRITSbot) [32] | |

| Dual Battery (Motor + Logic) | Noise isolation, redundancy | 4.2V Li-Ion ×2 | Abuelhaija SR [38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).