1. Introduction

According to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon of the American College of Radiology (ACR), nonmass enhancement (NME) is defined as an enhanced lesion without a space-occupying, three-dimensional, convex-edged mass on dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI of the breast. NME lesions do not cause distortion or displacement in the surrounding tissues, and islands of fatty tissue can be observed within them. In the ACR BI-RADS Atlas 5th edition, nonmass areas of contrast enhancement are classified according to their distribution characteristics and internal contrast enhancement patterns (IEPs) [

1]. The histopathological diagnostic results associated with NME lesions can be classified as benign, high-risk, or malignant. Among the malignant lesions presenting as NME, ductal carcinoma

in situ (DCIS) is the most common subtype; however, a substantial proportion also comprises invasive carcinomas. In a previous study, 57.1% of malignant NME lesions were diagnosed as DCIS and 42.9% as invasive carcinomas. This finding emphasizes the need for cautious assessment of invasive potential [

2,

3,

4].

NME lesions were assessed based on their distribution, IEP, dynamic curves, and diffusion restriction findings. Although various studies have evaluated NME lesion characteristics, only a few have analyzed large multicenter cohorts. Distribution pattern and IEP play important roles in assessing the risk of malignancy. Segmental distribution combined with clustered ring enhancement (CRE) patterns has the most significant correlation with malignancy [

3,

5].

CRE with segmental distribution improves the positive predictive value (PPV) for detecting DCIS, and both features are widely accepted as important radiological markers [

6]. Nevertheless, previous studies have revealed contrasting results regarding the predictive value of other imaging characteristics—such as diffusion restriction, hyperintensity on short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences, and time-intensity curve patterns—in differentiating benign from malignant NME lesions [

4,

5,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. These uncertainties emphasize the need for further multiparametric analysis in well-characterized lesion subgroups. Although previous studies have evaluated NME lesions as a group, their imaging features have rarely been analyzed in detail based on their distribution patterns. This lack of stratification creates ambiguity in clinical decision-making, particularly when assessing malignancy risk based on distribution or internal enhancement patterns. To address this gap, our study focused specifically on segmental NME, the distribution pattern with the highest reported PPV for malignancy, to investigate associated multiparametric MRI characteristics in detail.

Distinguishing NME lesions from the background parenchymal enhancement can be challenging. The background parenchymal enhancement commonly exhibits mild, persistent kinetic curves and bilateral symmetrical distribution. However, in some cases, asymmetrical patterns may mimic NME, which complicates differentiation. Baltzer et al. reported that the diagnostic performance of breast MRI in NME evaluation is highly dependent on reader experience [

12]. This underscores the need for improved diagnostic approaches, particularly for less experienced radiologists, and emphasizes the importance of performing larger case series to identify patterns based on their distribution characteristics.

We hypothesized that CRE patterns and early-phase kinetic curves have the highest predictive value for malignancy in segmental NME lesions. Identifying these patterns with multiparametric MRI can improve diagnostic accuracy and facilitate the differentiation between benign and malignant lesions.

This multicenter retrospective cohort study evaluated the correlation between segmental NME lesions, their internal enhancement patterns, dynamic contrast enhancement curves, diffusion restriction features, and T2-weighted imaging findings and malignancy. Further, we aimed to explore the potential use of these imaging characteristics in differentiating in situ and invasive malignancies in segmental NME lesions, thereby identifying the current limitations in predicting invasion based on imaging findings.

We believe that this study contributes to the existing literature by providing insights from a large multicenter cohort, offering valuable data to refine diagnostic strategies for NME lesions. Unlike most prior studies that pooled all NME patterns, our study isolates the segmental subtype—the distribution with the highest reported PPV for malignancy—to provide lesion-specific, multiparametric MRI markers. This stratified approach addresses a key evidence gap and aims to improve diagnostic precision and clinical decision-making for segmental NME. Further research on different NME distribution patterns should be performed to significantly enhance our understanding and help facilitate clinical decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

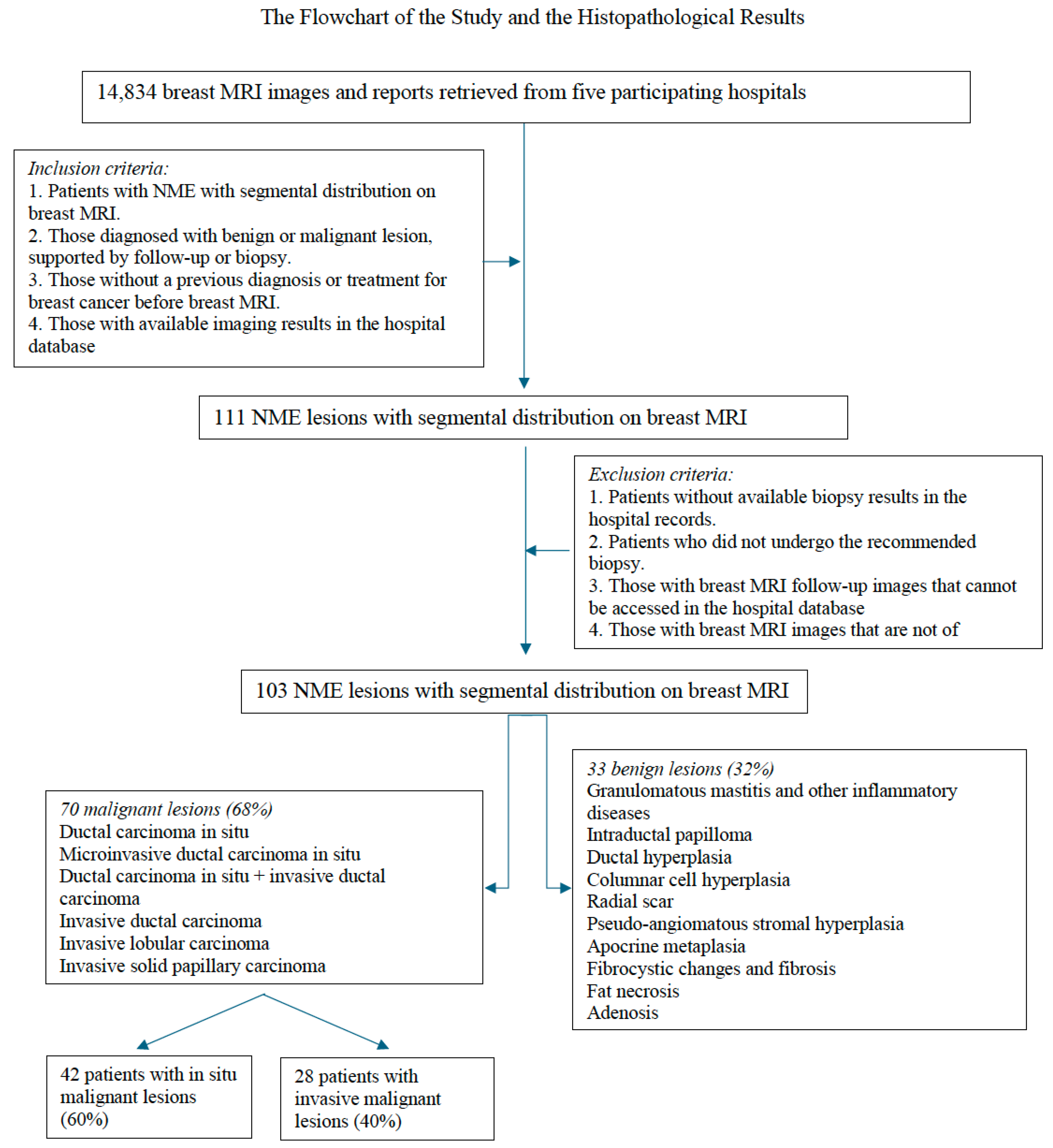

This multicenter retrospective cohort study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (Approval No. 2024-06/81; dated 11 July 2024). The need for patient consent was waived as only existing MRI images and histopathological data from hospital databases were analyzed. Breast MRI and pathology reports collected between September 2017 and February 2024 from five hospitals were reviewed. Of the 14,834 patients in the breast MRI reports, 111 with segmental NME lesions were identified. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with NME lesions with segmental distribution on breast MRI, (2) those with available data on histopathological diagnosis—benign or malignant—confirmed via biopsy or follow-up, (3) those without a previous history of breast cancer diagnosis or treatment before MRI, and (4) those with accessible data on prior imaging and clinical records within the hospital databases. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with unavailable or incomplete biopsy results in the hospital records, (2) those who did not undergo biopsy or were lost to follow-up, (3) those with MRI follow-up images that could not be retrieved, and (4) those who underwent MRI studies without essential sequences or those with images of non-diagnostic quality. Eight patients with incomplete pathology data or those who did not follow the biopsy recommendations were excluded from the study. Hence, 103 patients were finally included. All patients underwent MRI prior to any biopsy or surgical intervention. Surgical resection was performed on all patients with malignant lesions. Meanwhile, benign lesions were either excised or followed-up based on histopathological risk.

Figure 1 depicts the inclusion and exclusion process.

The biopsy and follow-up results were recorded. Lesions were confirmed via targeted ultrasonography in 66 patients, followed by US-guided core biopsies. MRI-guided biopsies were performed in three patients with lesions detectable exclusively on MRI, while MRI–ultrasound (MRI–US) fusion-guided biopsies were conducted in an additional three patients. Three patients underwent excisional biopsy under mammography guidance. Patients who did not undergo biopsy were monitored, and those with high-risk lesions underwent excision. The surgical pathology results were included for patients with malignancy diagnosed via core biopsy who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The histopathological diagnoses were classified as benign or malignant, and whether malignant NME lesions were invasive or in situ was recorded.

MRI scans were retrospectively reviewed between March and June 2024 by two breast radiologists (with 7 and 24 years of experience) who were blinded to the histopathologic results. The breast MRI protocol included axial seT1, fat-suppressed T2, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (b = 0 and b = 800), and at least five-phase DCE sequences. Examinations without any of these sequences or with significant artifacts were excluded from the analysis. Although imaging protocols varied slightly across centers, the acquired sequences were similar and analyzed with consistent technical parameters. The potential intercenter imaging variation was acknowledged as a study limitation. Selection bias was decreased with the use of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Observer bias was reduced by blinding the radiologists to the pathology results.

The radiologists evaluated IEPs according to the ACR BI-RADS 5th edition. If mixed IEPs were present, the pattern with the highest PPV was prioritized in the following order: CRE, clumped, heterogeneous, and homogeneous [

2].

Diffusion restriction was considered present when the ADC value was below 1000 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s [

5,

14]. Hyperintensity and/or cysts on fat-suppressed T2-weighted or STIR sequences were recorded. Initial-phase contrast enhancement was categorized as slow (<50% signal increase), medium (50% – 100%), or rapid (>100%). Meanwhile, delayed-phase enhancement was classified as persistent (>10% increase), plateau (no further increase), or washout (>10% signal decrease after the initial rise).

To reduce the impact of missing data, only patients with complete and diagnostically evaluable MRI and histopathology records were included in the final analysis. Eight patients were excluded: two were lost to follow-up after imaging and did not undergo biopsy, and six had MRI studies that were either missing essential sequences or rendered non-diagnostic due to motion or technical artifacts. Missing data were assumed to be completely at random (MCAR). No statistical imputation methods were applied, as a few cases were excluded and their exclusion was unlikely to introduce systematic bias. This was acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 23.0, and a p value <0.05 indicated statistically significant difference. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and lesion characteristics. The Pearson’s chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test were utilized to assess associations between variables. The associations between the imaging findings and histopathological outcomes were explored via univariate analyses. In the multivariate analyses, variables identified as potential risk factors for malignancy were subjected to a multivariate logistic regression analysis to calculate odds ratios (ORs). Variable selection was performed using the backward stepwise method, and the model fit was assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test.

A post-hoc power analysis with α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and a total sample size of 103 patients (70 with malignant lesions, 33 with benign lesions) indicated that the study could detect a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.60). This suggests that the sample size was sufficient to detect moderate differences. However, larger samples might be required for smaller effect sizes.

3. Results

A total of 103 patients with segmental NME lesions were included in the final analysis. The findings are presented according to patient and histopathological characteristics, internal enhancement patterns, multiparametric MRI features, and logistic regression outcomes. Detailed results are summarized below, with tables and figures illustrating the key observations.

3.1. Patient and Histopathological Characteristics

We examined 103 segmental NME lesions in 103 patients, with an average age of 44.38 ± 9.91 (range: 22–75) years. Of them, 70 (68%) presented with malignant lesions and 33 (32%) with benign lesions. The patients with malignant lesions were aged 26–75 (mean: 45.2) years. Among the 70 malignant tumors, 61 were ductal, 5 lobular, and 4 papillary. Approximately 40% of these malignant lesions were invasive and 60%

in situ. Seven patients had both invasive and

in situ components. These lesions were categorized as invasive.

Figure 1 depicts the histopathological diagnostic results.

3.2. Multiparametric Breast MRI Findings

3.2.1. Internal Enhancement Patterns

In our study group, heterogeneous IEPs were observed in 32% of the lesions, CRE in 31.1%, clumped patterns in 29.1%, and homogeneous patterns in 7.8%. Based on the Pearson chi-square test, there was a statistically significant correlation between IEP and histopathological outcomes (p = 0.002). CRE was found in 40% of malignant segmental NME lesions, and a significant correlation was observed (p = 0.004). CRE exhibited a sensitivity of 40%, specificity of 88%, and PPV of 87.5% for diagnosing malignancy, all with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneous patterns were most typically noted in benign lesions, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.001). Based on the univariate logistic regression (ULR) analysis, CRE increased the likelihood of malignancy by 4.8-fold (OR = 4.833, p = 0.007). Clumped and homogeneous patterns were not statistically significant (

Table 1).

3.2.1. Mixed Enhancement Patterns

Of the 75 patients who were assessed for mixed IEP (

Figure 2), 26 (34.7%) presented with the pattern. Approximately 41.55% of the patients with malignant lesions had mixed IEP. Of them, 15.4% exhibited benign lesions and 84.6% malignant lesions. Although the association did not reach conventional statistical significance (p = 0.053), a trend toward significance was noted. In ULR analysis, the presence of mixed IEP was associated with a 3.19-fold increased likelihood of malignancy (p = 0.061). This suggests that a larger sample size may improve the statistical power and clarify the strength of this association.

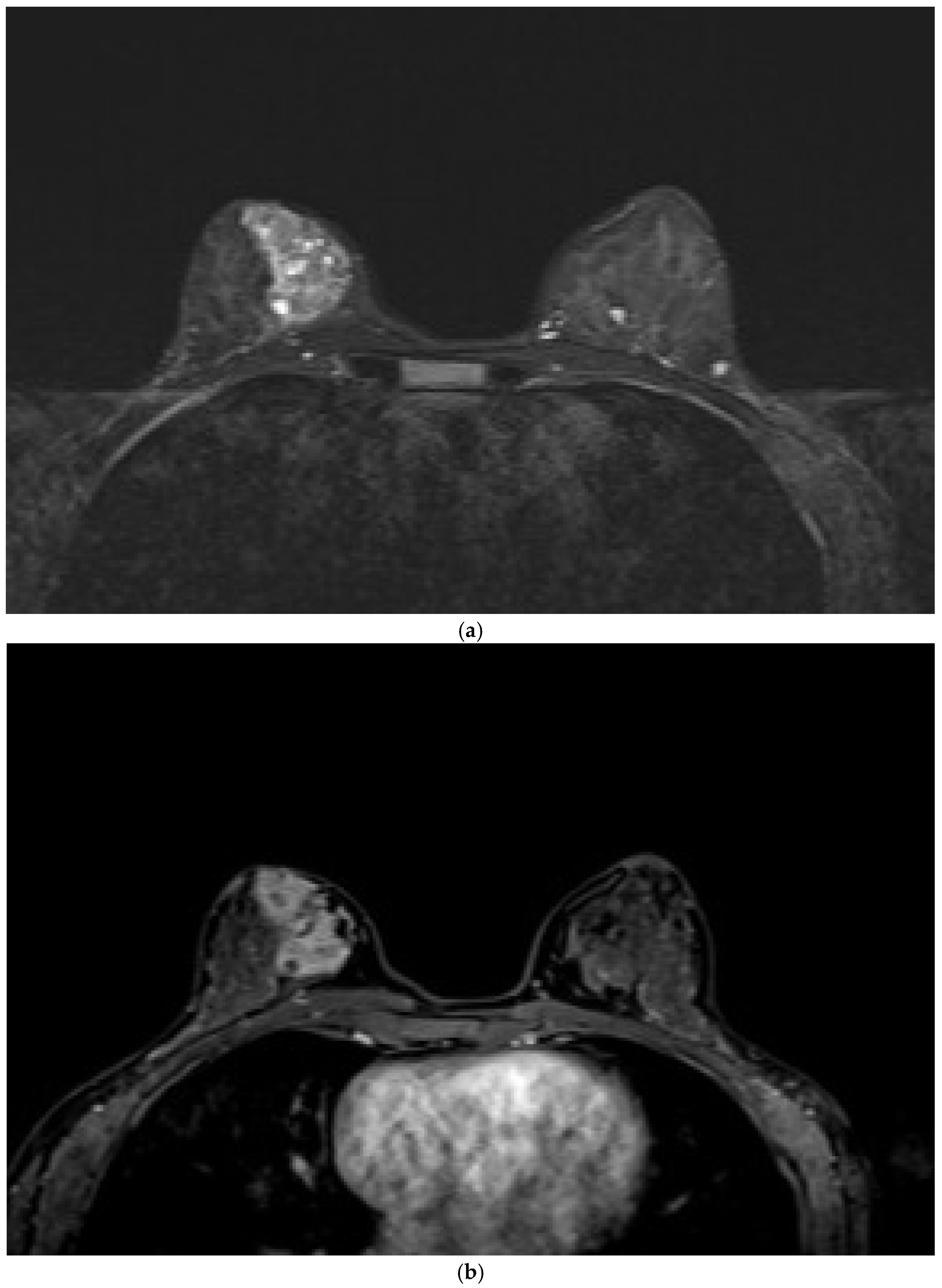

3.2.3. STIR and Diffusion MRI Findings

Cystic structures on the STIR sequences were observed in 27.2% of the lesions, 30.7% of which were benign and 69.3% were malignant (

Figure 3). The frequency rate of cystic structures in the malignant lesions was 25.7%, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.625). Diffusion restriction was found in 60.9% of lesions (64.1% in malignant lesions and 57.6% in benign lesions), without statistical significance (p = 0.533). The ULR analysis showed a 1.3-fold higher likelihood of malignancy in lesions with diffusion restriction. However, this result was not significant.

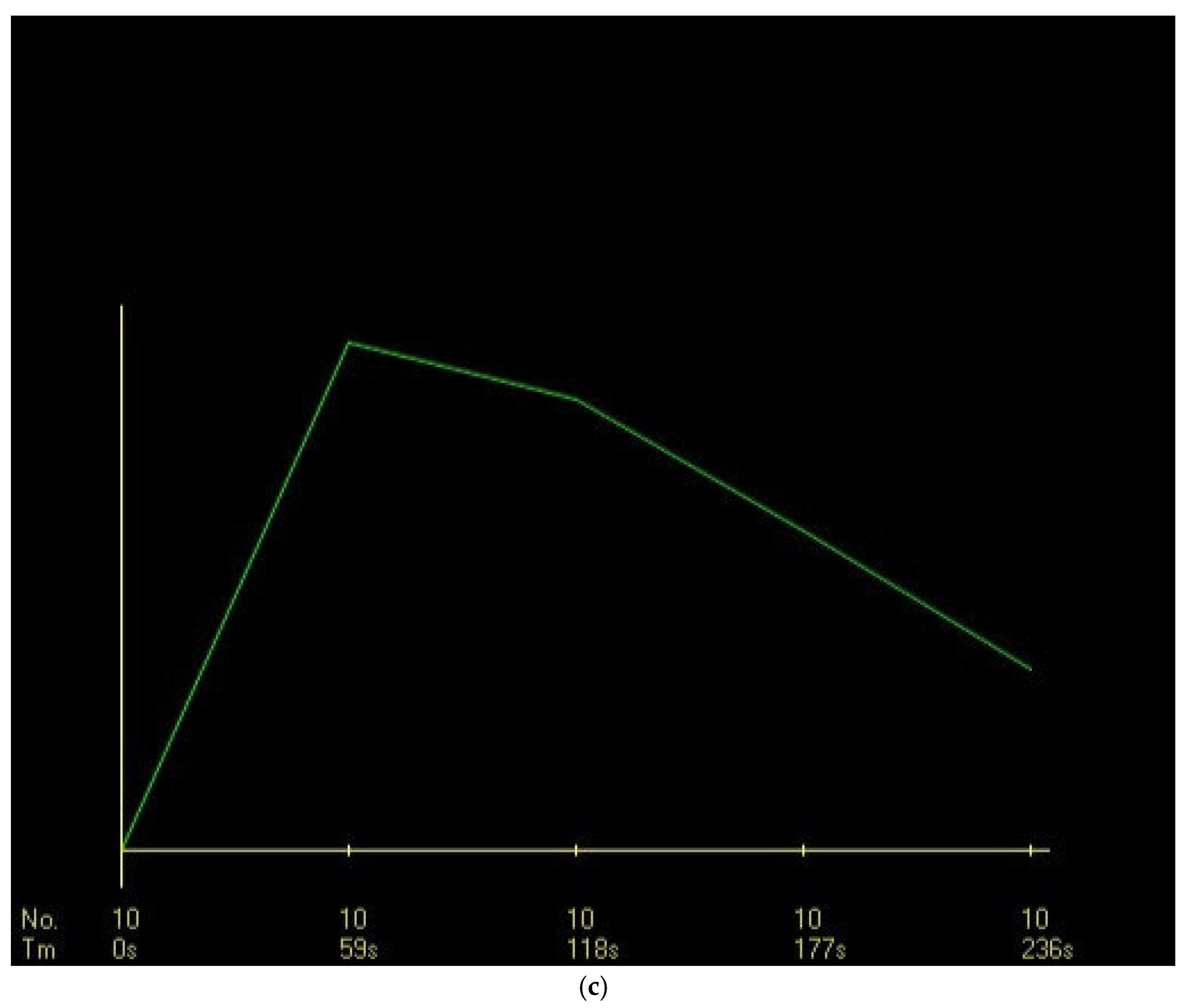

3.2.4. DCE-MRI Kinetic Features

In the DCE-MRI assessment, the most common dynamic curve pattern was rapid contrast enhancement in the initial phase (46.6%), with a plateau pattern in the delayed phase (45.6%). Rapid early-phase contrast uptake was observed in 60% of malignant lesions, with a significantly strong correlation (p < 0.001). It had a sensitivity of 60%, specificity of 82%, and PPV of 87.5% (95% CI, 76.8–98.2). Further, based on the ULR analysis, rapid contrast uptake was associated with 6.75-fold increase in the likelihood of malignancy, which was statistically significant (OR: 6.750, p < 0.001) (

Figure 3).

The most frequent dynamic curve pattern during the delayed phase was a plateau, which was observed in 44.3% of malignant lesions and 48.5% of benign lesions, without significant difference (p = 0.690). The washout pattern was the second most common, which was found in 31.4% of malignant lesions and 6.1% of benign lesions, with a strong association with malignancy (p = 0.004). The washout curve had a sensitivity of 31%, specificity of 94% (95% CI, 79.8–99.3), and PPV of 91% (95% CI, 76.5–97.8). Further, according to the ULR analysis, it increased the likelihood of malignancy by 7.1-fold, which was statistically significant (OR: 7.104, p = 0.011).

In DCE-MRI, a slow initial-phase contrast uptake was observed in 60.6% of benign lesions. This finding was significantly different from that in malignant lesions (p < 0.001). Approximately 45.5% of benign lesions presented with persistent enhancement curves in the delayed phase, which was also statistically significant (p = 0.030). According to the ULR analysis, the ORs were 0.134 for slow contrast uptake (p < 0.001) and 0.385 for persistent enhancement in the delayed phase (p = 0.033), both of which were statistically significant.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

A comprehensive multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. In this analysis, variables with significant or borderline associations, including CRE, heterogeneous enhancement, initial-phase kinetic curves (slow and rapid), delayed-phase patterns (persistent and washout), and mixed IEP, were incorporated. In the multivariate analysis, only rapid and slow initial-phase enhancements remained statistically significant. Rapid initial-phase enhancement increased the likelihood of malignancy by 5.133-fold (p = 0.031). Meanwhile, slow enhancement was associated with benignity (OR = 0.194, p = 0.020). In the univariate analysis, CRE increased the likelihood of malignancy by 4.833-fold and the washout-type delayed enhancement by 7.104-fold, which were both statistically significant. These findings underscore the diagnostic value of early-phase kinetics and specific enhancement patterns in differentiating malignant segmental NME lesions.

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate regression analyses.

3.4. Correlation with Invasion

The correlation between imaging findings and invasion in malignant segmental NME lesions did not identify definitive markers for predicting

in situ or invasive cancer. Mixed IEP was found in 59.1% of malignant lesions. CRE was observed in 32.1% of lesions, clumped pattern in 50%, heterogeneous enhancement in 40%, and homogeneous enhancement in 42.9%. Among the malignant NME lesions with CRE, 67.9% were

in situ lesions, and 32.1% were invasive. However, this difference was not significant (p = 0.273). Cystic structures on STIR sequences were found in 61.1% of

in situ lesions and 38.9% of invasive lesions, and a significant correlation was not found between cystic structures and invasion. Further, there were no significant differences in the early- and late-phase dynamic curves and diffusion restriction between invasive and

in situ lesions (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

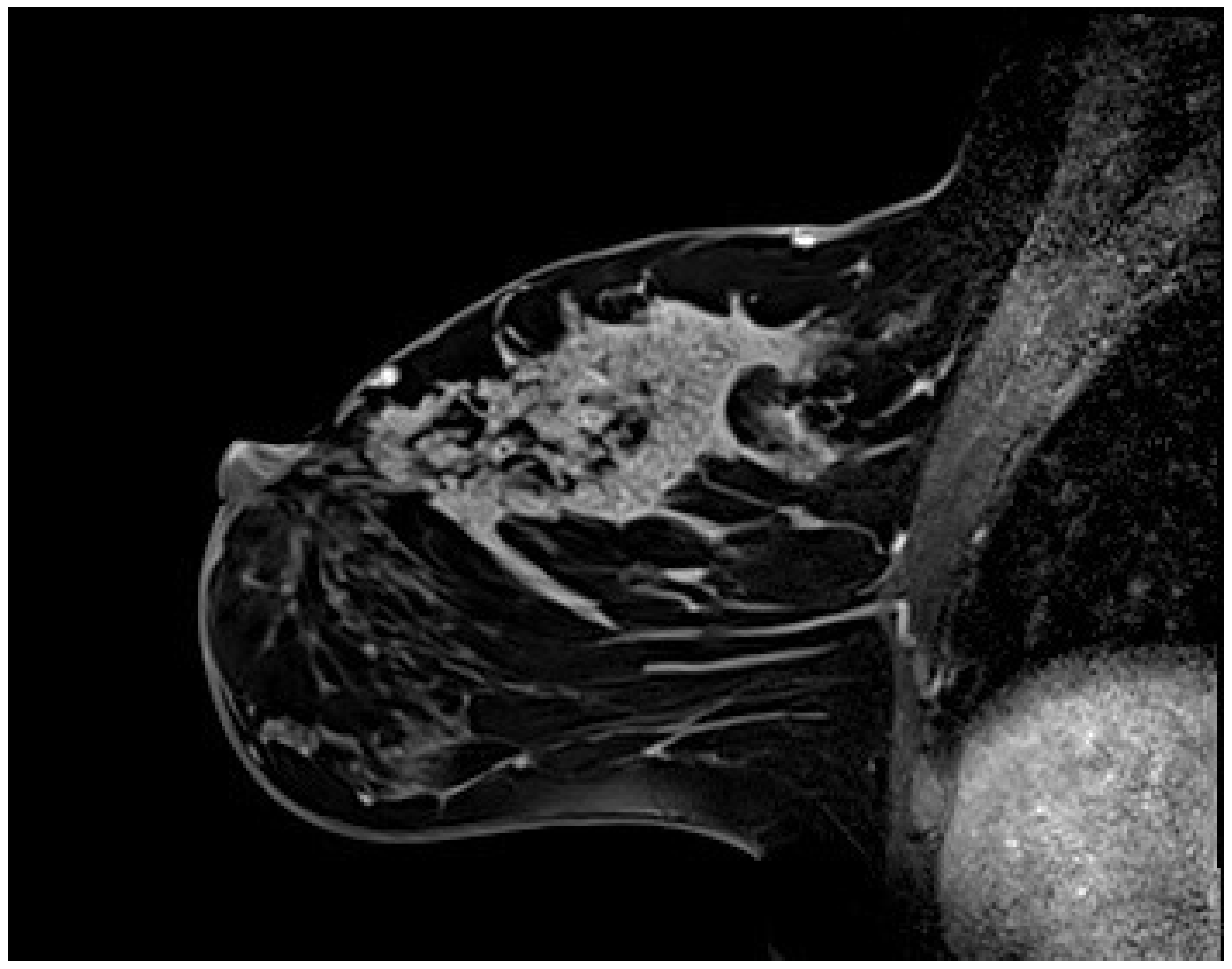

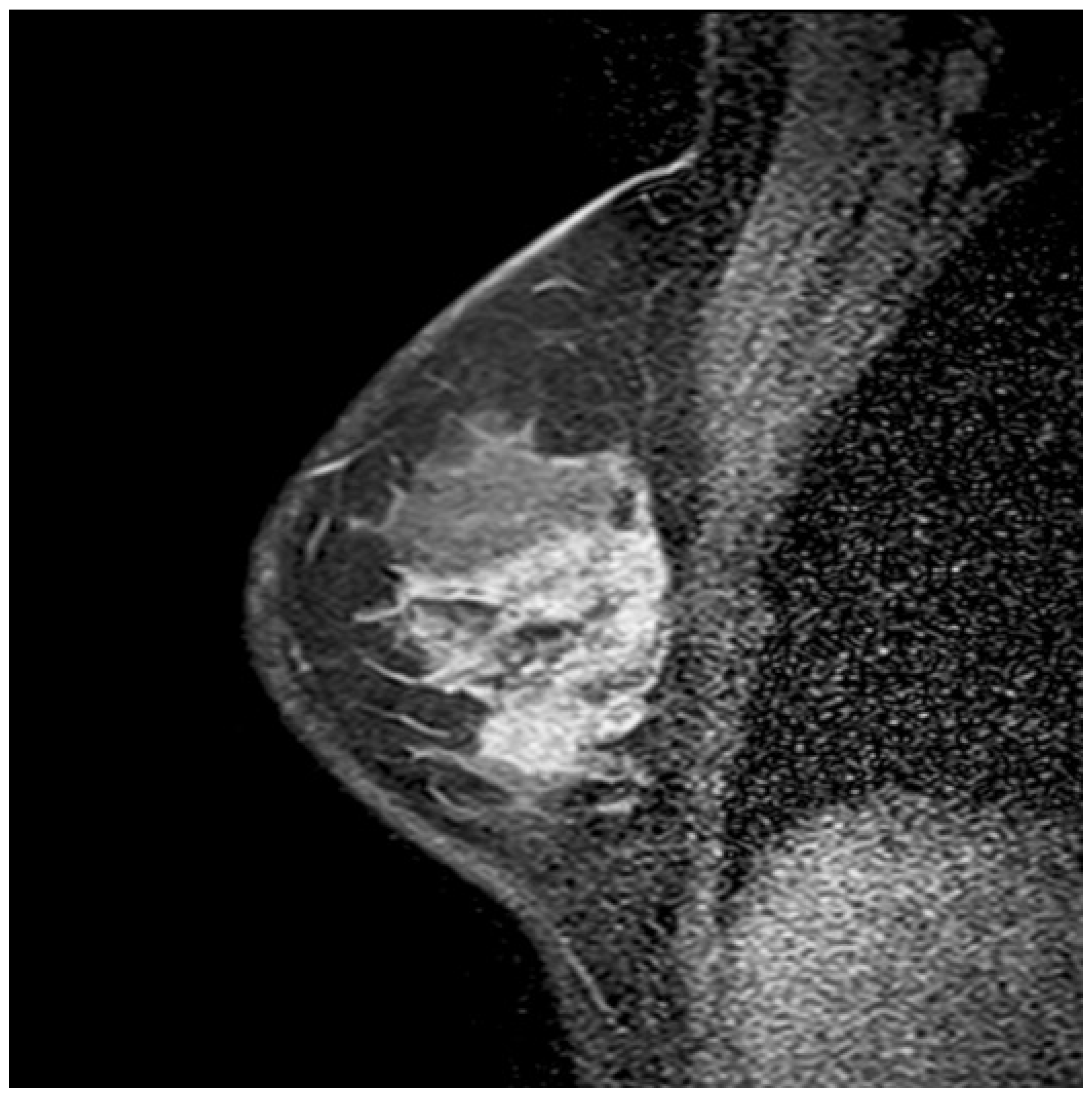

NME lesions with segmental distribution were evaluated according to the ACR BI-RADS 5th edition lexicon [

1]. CRE was the second most common pattern after heterogeneous enhancement and the most frequent IEP in malignant lesions, with statistical significance (p < 0.05). The PPV of CRE was 87.5% (95% CI, 76.8–98.2), which is consistent with the literature. Its specificity was 88% (95% CI, 74.2–94.4), which is higher than the values reported in the literature. This discrepancy might be attributed to the fact that our study focused solely on segmental NME lesions with the highest PPV. Segmental NME forms a distinctive pyramidal configuration, with the apex aligning toward the nipple and the base extending toward the chest wall (

Figure 4). Previous studies have clearly reported a strong association between segmental NME and DCIS [

3,

4,

8,

9,

10,

15].

Table 3 summarizes previously reported histopathologic diagnoses associated with segmental NME lesions for contextual reference.

Overall, heterogeneous IEP was the most common contrast pattern, but it was least frequently observed in malignant lesions. Kubota et al. performed a meta-analysis in 2023, and they reported varying results regarding the association between heterogeneous contrast patterns and malignancy [

7]. Our study found no association between malignancy and heterogeneous enhancement. However, it was the most prevalent pattern in benign lesions (54.5%), with a significant association (p = 0.001).

Homogeneous IEP was the least observed pattern and was not significantly associated with malignancy. The prevalence rate of malignancy in segmental NME lesions with a clumped contrast pattern was 66.7%. However, its association with malignancy was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), which is consistent with previous studies [

4,

6].

Mixed IEP, where two or more IEP types were present within the same lesion, was observed in 34.7% of cases. Among these, 84.6% were malignant lesions, with slight statistical significance (p = 0.053). Shimauchi et al. showed that clumped and CRE patterns might have similar developmental mechanisms and occur concomitantly [

10]. Our study did not specify which contrast patterns coexisted within the mixed contrast findings. However, if some cases of mixed IEP represent a combination of CRE and clumped enhancement patterns, this may partially account for the borderline statistical association observed. Thus, further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate this relationship and enhance statistical power.

Li Yan et al. showed that the diagnostic performance of DWI was inferior to that of DCE-MRI, possibly due to DWI slice thickness [

13]. Our study, which focused on segmental NME, did not encounter this limitation as all lesions were larger than the DWI slice thickness. Diffusion restriction was observed in both benign and malignant lesions, with no significant correlation to malignancy. Previous studies have shown that unlike mass lesions, the diagnostic accuracy of diffusion restriction in NME lesions is limited [

11,

13]. The alignment of our findings with previously published reports, within a cohort with a high malignancy risk in segmental NMEs, underscores the diagnostic limitations of diffusion restriction in NME lesions.

Baltzer et al. did not find statistically significant differences in the dynamic enhancement features between benign and malignant lesions [

12]. Conversely, Liu et al. showed that the washout curves were more frequent in malignant lesions. Meanwhile, persistent curves were more common in benign ones, with statistical significance [

3]. Our study identified a strong association between malignancy and rapid contrast uptake in the initial phase and washout dynamic curves in the delayed phase (p < 0.001 and p = 0.009, respectively). The literature has reported that plateau curves were more frequently observed in malignant NME lesions, unlike our findings [

3,

4,

5,

13]. In addition, Liu et al. have found that the washout type curves might help distinguish invasive breast cancer from benign lesions. However, our study did not find a statistically significant correlation between the invasion and dynamic curves.

There was no statistically significant correlation between the cystic structures observed in the STIR images and the presence of benign or malignant lesions. Previous studies have contrasting findings on this matter. Milosevic et al. showed an association between the presence of microcysts on STIR and atypical lesions [

16]. Baltzer and colleagues have reported that hyperintensity accompanying NME lesions on T2-weighted images is more significantly associated with benignity and hypointensity than with malignancy [

12]. Conversely, Chikarmane et al. showed that hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences is unreliable for assuming benignity in NME lesions [

2].

The efficacy of MRI in distinguishing invasive NME lesions varies across studies. Liu et al. found no association between invasion and IEP. Meanwhile, Hahn et al. reported that CRE was more frequently found in microinvasive ductal carcinomas than in DCIS [

3,

17]. Machida et al. found a significant correlation between CRE and malignancy, indicating that IEPs could predict invasion, with PPV values of 40.2% for clumped patterns, 46.2% for branching, 51.8% for heterogeneous enhancement, 50% for CRE, and 73.9% for hypointense areas, which are not included in the MRI BI-RADS atlas [

9]. Using the ACR BI-RADS 5th edition criteria, our study did not find significant predictors of invasion, possibly due to the exclusion of specific descriptors analyzed in the study of Machida et al.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature might have introduced selection bias and resulted in incomplete imaging and clinical records despite the predefined criteria. Second, the multicenter design, with varying MRI field strengths and imaging parameters, might have led to inconsistencies in image resolution and IEP evaluation, particularly in differentiating CRE from clumped patterns. Although the acquired sequences were similar, the parameter variations across centers remain a limitation. However, the multicenter approach improves patient diversity and enhances generalizability. Missing data were addressed by excluding cases with incomplete pathology or imaging records, assuming that the data were completely at random (MCAR), which could have affected the generalizability of the findings. Observer bias was decreased by having experienced radiologists independently review the images. However, interobserver variability remains a potential limitation. Finally, post-hoc power analysis showed that the study had sufficient power (80%) for detecting a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.60) with the available sample size (n = 103). However, smaller effect sizes might have gone undetected, thereby suggesting the need for larger sample sizes in future studies to improve statistical power and diagnostic accuracy.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study offers a comprehensive examination of segmental NME lesions and their multiparametric MRI findings in relation to malignancy and invasion in a broad patient population. The results can provide significant insights into distinguishing benign from malignant lesions and identifying the presence of invasive components. Further, they can contribute significantly to the current body of literature and clinical scenarios encountered in daily practice, thereby setting a foundation for future multicentric and extensive studies to better understand the less common NME patterns.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, HA; methodology, HA; validation, HA, CB, ACB, PSO, AAA, IGO, SG, AE, IDS; formal analysis, SH; investigation, HA, CB, ACB, PSO, AAA, IGO, SG, AE, IDS; resources, HA; data curation, HA; writing—original draft preparation, HA; writing—review and editing, CB, ACB, PSO, AAA, IGO, SG, AE, IDS; visualization, SH; supervision, HA; project administration, HA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Wenta Heat Technologies A.S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dr AY Ankara Oncology Training and Research Hospital, Health Sciences University (protocol code 2024-06/81; date of approval 11 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the radiology departments of all participating institutions for their valuable support in the data collection and image interpretation. The authors would like to thank Enago for providing English language editing services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACR |

American College of Radiology |

| BI-RADS |

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| CRE |

clustered ring enhancement |

| DCE |

dynamic contrast-enhanced |

| DCIS |

ductal carcinoma in situ |

| DWI |

diffusion-weighted imaging |

| IDC |

Invasive ductal carcinoma |

| IEP |

Internal enhancement pattern |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NME |

nonmass enhancement |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PPV |

Positive Predictive Value |

| STIR |

Short Tau Inversion Recovery |

References

- (ACR) American College of Radiology. - ACR BI-RADS-ACR (2014).

- Chikarmane, S.A.; Michaels, A.Y.; Giess, C.S. Revisiting Nonmass Enhancement in Breast MRI: Analysis of Outcomes and Follow-Up Using the Updated BI-RADS Atlas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 209, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Chen, Q. Non-Mass Enhancement Breast Lesions: MRI Findings and Associations with Malignancy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-X.; Ji, X.; Feng, L.-L.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, X.-Q.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X. Significant MRI Indicators of Malignancy for Breast Non-Mass Enhancement. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2017, 25, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, H. The MRI Characteristics of Non-Mass Enhancement Lesions of the Breast: Associations with Malignancy. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20180464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Faria Castro Fleury, E.; Castro, C.; do Amaral, M.S.C.; Roveda Junior, D. Management of Non-Mass Enhancement at Breast Magnetic Resonance in Screening Settings Referred for Magnetic Resonance-Guided Biopsy. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2022, 16, 11782234221095897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, K.; Mori, M.; Fujioka, T.; Watanabe, K.; Ito, Y. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Diagnosis of Non-Mass Enhancement of the Breast. J. Med. Ultrason. 2001 2023, 50, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesio, L.; Di Pastena, F.; Gigli, S.; D’ambrosio, I.; Aceti, A.; Pontico, M.; Manganaro, L.; Porfiri, L.M.; Tardioli, S. Non Mass-like Enhancement Categories Detected by Breast MRI and Histological Findings. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Machida, Y.; Shimauchi, A.; Tozaki, M.; Kuroki, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Fukuma, E. Descriptors of Malignant Non-Mass Enhancement of Breast MRI: Their Correlation to the Presence of Invasion. Acad. Radiol. 2016, 23, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimauchi, A.; Ota, H.; Machida, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Satani, N.; Mori, N.; Takase, K.; Tozaki, M. Morphology Evaluation of Nonmass Enhancement on Breast MRI: Effect of a Three-Step Interpretation Model for Readers’ Performances and Biopsy Recommendations. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016, 85, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avendano, D.; Marino, M.A.; Leithner, D.; Thakur, S.; Bernard-Davila, B.; Martinez, D.F.; Helbich, T.H.; Morris, E.A.; Jochelson, M.S.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; et al. Limited Role of DWI with Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Mapping in Breast Lesions Presenting as Non-Mass Enhancement on Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2019, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, P.A.T.; Dietzel, M.; Kaiser, W.A. Nonmass Lesions in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast: Additional T2-Weighted Images Improve Diagnostic Accuracy. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2011, 35, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Fan, C.; Qin, Y.; Tang, C.; Yin, T.; Ai, T.; Xia, L. Contrasts Between Diffusion-Weighted Imaging and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MR in Diagnosing Malignancies of Breast Nonmass Enhancement Lesions Based on Morphologic Assessment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2023, 58, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickel, H.; Pinker, K.; Polanec, S.; Magometschnigg, H.; Wengert, G.; Spick, C.; Bogner, W.; Bago-Horvath, Z.; Helbich, T.H.; Baltzer, P. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging of Breast Lesions: Region-of-Interest Placement and Different ADC Parameters Influence Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, M.; Liu, D.; Sheng, F.; Cai, J. Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Breast Papillary Neoplasms on MRI With Non-Mass Enhancement. Acad. Radiol. 2023, 30 (Suppl. 2), S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, Z.C.; Nadrljanski, M.M.; Milovanovic, Z.M.; Gusic, N.Z.; Vucicevic, S.S.; Radulovic, O.S. Breast Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI: Fibrocystic Changes Presenting as a Non-Mass Enhancement Mimicking Malignancy. Radiol. Oncol. 2017, 51, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.Y.; Han, B.-K.; Ko, E.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Nam, M. MR Features to Suggest Microinvasive Ductal Carcinoma of the Breast: Can It Be Differentiated from Pure DCIS? Acta Radiol. Stockh. Swed. 1987 2013, 54, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).