1. Introduction

The introduction of the covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib has revolutionized the treatment paradigm and improved outcomes for patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leuk[emia (CLL) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These orally administered agents, delivered on a daily basis, have demonstrated substantial clinical efficacy, yielding high response rates and enhancing patients’ quality of life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. When utilized as first-line therapy, BTK inhibitors can induce durable remissions extending beyond four years in approximately 70–80% of patients [

10]. Despite these advances, a considerable proportion of patients discontinue therapy due to adverse events (AEs), predominantly attributable to off-target kinase inhibition [

11]. The most common reasons for discontinuation include cardiac arrhythmia, most notably atrial fibrillation and pneumonia [

12,

13]. Additionally, between 13% and 37% of patients cease therapy due to limited efficacy or the development of resistance mechanisms [

14]. Notably, discontinuation due to toxicity appears more prevalent with ibrutinib, whereas resistance-related discontinuation is observed across all available covalent BTK inhibitors [

15,

16].

All approved covalent BTK inhibitors irreversibly bind to cysteine residue 481 (Cys481) within the ATP-binding pocket of BTK, resulting in permanent enzyme inhibition [

17,

18,

19]. This covalent interaction necessitates the formation of a stable, irreversible bond, which can only be reversed through de novo synthesis of BTK [

20]. Prolonged selective pressure exerted by continuous inhibition fosters the emergence of somatic mutations within the BTK gene, often at the Cys481 site, that impair drug binding affinity. The most frequently observed mutations involve amino acid substitutions at Cys481, such as C481S or C481R, that reduce covalent binding stability, thereby diminishing drug efficacy [

20]. Less commonly, gain-of-function mutations in downstream signaling molecules like phospholipase C gamma 2 (PLCγ2) can occur which enable B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling to persist, and can synergise with BTK mutations, thus contributing to resistance [

21,

22,

23].

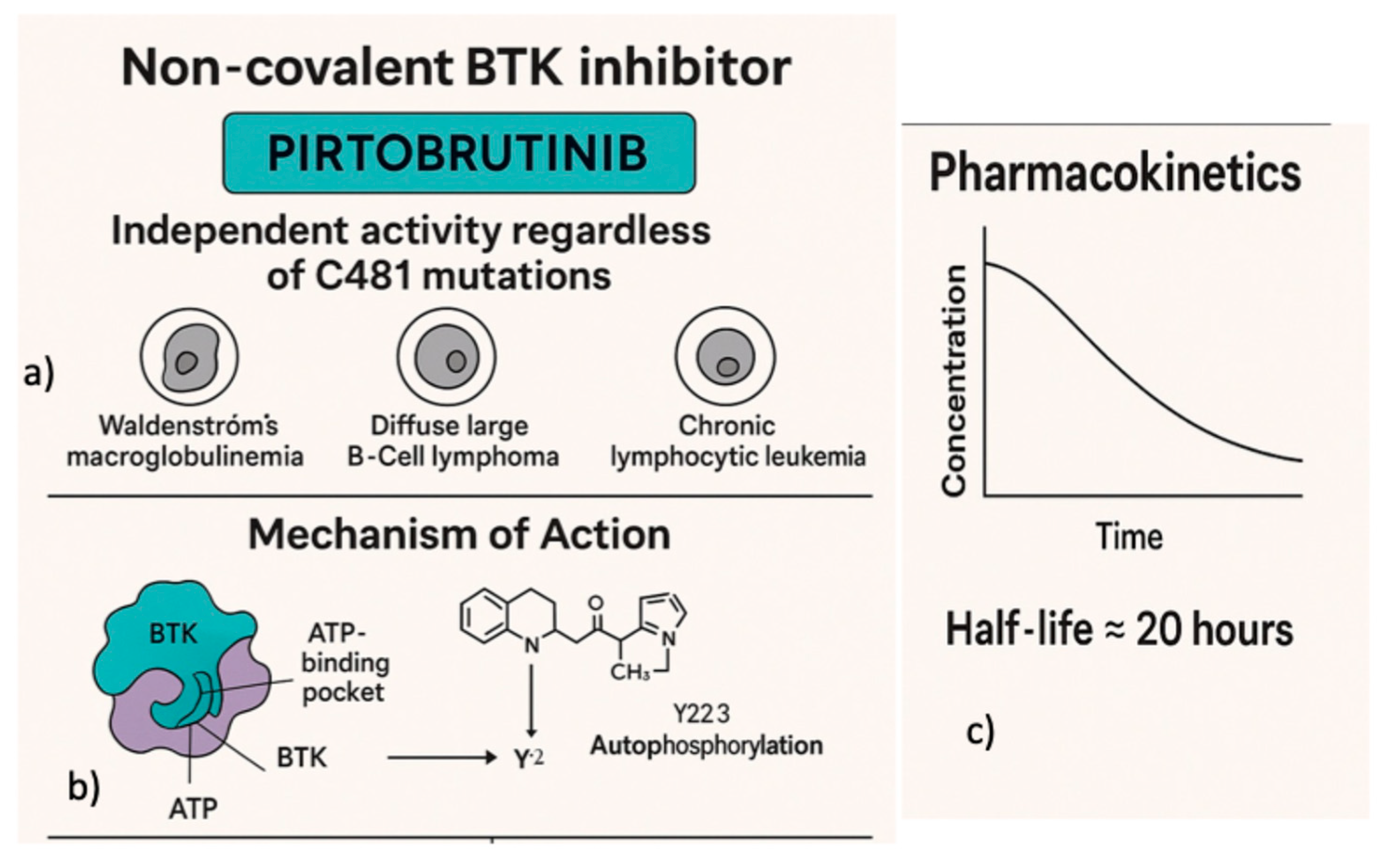

In contrast, noncovalent BTK inhibitors such as pirtobrutinib do not rely on covalent modification of Cys481 (

Figure 1b) [

24]. Instead, such inhibitors reversibly associate with the ATP-binding site through a combination of hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, and hydrophobic contacts. This reversible binding mode allows inhibitory BTK activity in the presence of Cys481 mutations which would confer resistance to covalent inhibitors [

25,

26]. Clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that pirtobrutinib retains activity in patients harboring Cys481 mutations; however, resistance can also develop through other somatic alterations within the BTK gene that affect the binding interface [

27,

28]. Such genetic alterations may diminish the efficacy of both covalent and noncovalent BTK inhibitors, underscoring the complexity of resistance mechanisms and the need for continuous monitoring and development of novel therapeutic strategies [

27,

28].

Figure 1.

Pirtobrutinib demonstrates activity across multiple lymphoid malignancies (a). It binds to Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) in a non-covalent manner. Unlike covalent BTK inhibitors, which irreversibly bind to the BTK active site, pirtobrutinib retains inhibitory activity even in the presence of mutations within this region, such as the Cys481 substitution (b). Its favorable oral pharmacokinetic profile enables sustained BTK inhibition throughout the once-daily dosing interval (c).

Figure 1.

Pirtobrutinib demonstrates activity across multiple lymphoid malignancies (a). It binds to Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) in a non-covalent manner. Unlike covalent BTK inhibitors, which irreversibly bind to the BTK active site, pirtobrutinib retains inhibitory activity even in the presence of mutations within this region, such as the Cys481 substitution (b). Its favorable oral pharmacokinetic profile enables sustained BTK inhibition throughout the once-daily dosing interval (c).

This review provides an overview of the clinical studies that have underpinned the incorporation of pirtobrutinib into the current therapeutic algorithm for CLL. Ongoing investigations will clarify its role as a first-line therapy and its potential integration with novel T-cell engager therapies for patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.

2. Pirtobrutinib Mechanism-of-Action and Pharmacology

Unlike covalent BTK inhibitors pirtobrutinib exhibits activity independent of C481 mutation status, including mutations such as C481S and C481R that confer resistance to earlier-generation agents [

26]. This distinctive pharmacological characteristic positions pirtobrutinib as a versatile therapeutic agent for treating a spectrum of B-cell malignancies, notably Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and CLL (

Figure 1a) [

25].

Structurally, pirtobrutinib interacts within the ATP-binding pocket of BTK at a site spatially distinct from the C481 residue (

Figure 1). This binding mode enables it to maintain inhibitory activity even when mutations impair covalent bond formation at C481 [

24]. Biochemical assays, complemented by cell-based experimental models, have demonstrated that pirtobrutinib maintains comparable potency against wild-type BTK and mutant variants, including C481S and C481R, effectively inhibiting kinase activity regardless of mutation status. In vitro studies utilizing MEC-1 cell lines engineered to overexpress either wild-type or mutant BTK further confirm that pirtobrutinib effectively inhibits BTK autophosphorylation at tyrosine 223 (Y223) and downstream signaling pathways, independently of mutation presence [

29].

Data obtained from the ongoing phase I/II trial NCT03740529 support these preclinical findings. Early treatment results indicate significant reductions in plasma levels of chemokines CCL3 and CCL4, which are biomarkers associated with disease activity in BTK mutanted CLL which highlights the compound’s effective in vivo activity. Mechanistically, pirtobrutinib is a potent inhibitior of BTK autophosphorylation at Y223, a critical activation site. Although primarily classified as a back-pocket inhibitor, evidence suggests pirtobrutinib may also suppress upstream phosphorylation at tyrosine 551 (Y551), potentially through stabilization of BTK in an inactive, closed conformation. Structural insights further suggest that phosphorylation at Y551 is vital for the recruitment of hematopoietic cell kinase (HCK) to kinase-dead BTK mutants, which may contribute to residual signaling despite kinase domain inactivation, providing a rationale for the continued efficacy of pirtobrutinib [

29].

Selectivity profiling reveals that pirtobrutinib exhibits extraordinary specificity for BTK, being over 100-fold more selective for BTK than for a broad panel of other kinases tested. Enzymatic profiling indicates that pirtobrutinib interacts minimally with over 98% of human kinases, a feature that likely contributes to a favorable safety profile by reducing off-target adverse effects, such as cardiotoxicity, which are associated with less selective covalent inhibitors [

27].

Pharmacokinetic analyses have demonstrated that pirtobrutinib exhibits linear kinetics over a dose range from 25 mg to 300 mg daily, with an estimated half-life of approximately 20 hours. No dose-limiting toxicities have been observed at these doses, supporting the selection of 200 mg daily as the recommended phase II dose. This dosing achieves plasma trough concentrations capable of inhibiting approximately 96% of BTK activity, effectively ensuring continuous suppression of kinase activity throughout the dosing interval (

Figure 1c) [

30]. The extended half-life provides a pharmacokinetic advantage over irreversible inhibitors by maintaining sustained drug levels, thereby ensuring ongoing inhibition of newly synthesized BTK molecules and reducing the potential for disease progression due to incomplete kinase suppression [

27,

30].

3. Early Clinical Studies

Initial FDA approval for pirtobrutinib was based on the results of the multicenter phase 1/2 BRUIN study (NCT03740529), which enrolled patients with pretreated B-cell malignancies, including CLL, MCL, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and follicular lymphoma [

30]. A total of 323 patients received pirtobrutinib across seven dose levels—25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg, 250 mg, and 300 mg administered once daily—demonstrating a linear relationship between dose and systemic drug exposure. No dose-limiting toxicities were identified, and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached within the dose range studied. Based on safety and pharmacokinetic data, the recommended phase 2 dose was established at 200 mg daily. The most frequently reported adverse events, occurring in at least 10% of participants, included fatigue (20%), diarrhea (17%), and contusions (13%). Grade 3 or higher adverse events most commonly involved neutropenia, observed in 10% of patients. Notably, there were no reports of grade 3 atrial fibrillation or flutter; also grade 3 hemorrhage was rare, occurring in a single patient following mechanical trauma. Treatment discontinuation due to adverse events was necessary in approximately 1% of patients [

30].

Efficacy assessments in 121 patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), many of whom had previously received covalent BTK inhibitors (with a median of four prior lines of therapy), revealed an overall response rate (ORR) of 62%. Subgroup analyses indicated comparable response rates among patients with prior resistance to covalent BTK inhibitors (67%), those intolerant to such therapies (52%), patients harboring BTK C481 mutations (71%), and those with wild-type BTK (66%). At the time of analysis, the majority of responders—117 out of 125—remained progression-free, underscoring the potential durability of responses in this patient population [

30].

An update of this trial, including 317 with relapsed or refractory CLL or SLL, has indicated potential differences in treatment responses among patients with distinct genetic mutations [

31]. Notably, among patients harboring mutated Phospholipase C Gamma 2 (PLCG2), the ORR was 56%, which is lower than the response observed in patients with BTK C481 mutations. These findings suggest that additional data are necessary to more accurately assess the efficacy of treatment specifically in patients with PLCG2 mutations.

Overall, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 19.6 months. For patients who had previously received both a BTK inhibitor and a BCL2 inhibitor, the median PFS was 16.8 months. In contrast, patients who had been treated with a BTK inhibitor alone experienced a longer median PFS of 22.1 months.

Finally, pirtobrutinib was effective also in patients who had undergone all five available therapies for CLL or SLL—including BTK, BCL2, and PI3K inhibitors, as well as anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy. In these patients the median progression-free survival was 13.8 months [

31].

A retrospective, multi-center phase I/II analysis of the BRUIN study evaluated the safety and efficacy of pirtobrutinib monotherapy in patients who previously discontinued a BTK inhibitor due to intolerance [

32]. This cohort included 78 patients, of whom 61.4% (n=48) had CLL. The majority of participants had prior treatment with the first-generation covalent BTKi, ibrutinib. The adverse events (AEs) leading to discontinuation of prior BTKi therapy aligned with known toxicities associated with intolerance to ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib. Cardiac-related issues, particularly atrial fibrillation, were the most common reasons for stopping BTKi therapy, with 40 patients (31.5%) experiencing cardiac disorders and 30 (23.6%) specifically reporting atrial fibrillation [

32].

The median follow-up duration was 17.4 months, during which patients remained on pirtobrutinib for a median of 15.3 months. The primary reasons for discontinuing pirtobrutinib were respectively disease progression (26.8%), AEs (10.2%), and death (5.5%). The most frequently reported treatment-emergent AEs were fatigue (39.4%) and neutropenia (37.0%). Notably, among patients who previously discontinued a BTK inhibitor due to cardiac concerns, 75% did not experience a recurrence of their cardiac AE. Importantly, no patient stopped pirtobrutinib because of the same AE that led to prior BTKi discontinuation, suggesting that pirtobrutinib may be a viable option for patients intolerant to covalent BTK inhibitors. Finally, the median PFS for the CLL/SLL subgroup was 28.4 months [

32].

These findings establish that the third-generation BTK inhibitor pirtobrutinib possesses a compelling efficacy and safety profile, with the potential to address several unmet needs associated with covalent BTK inhibitors. Furthermore, clinicians treating patients with CLL now have access to an agent that allows for the full utilization of BTK inhibition before transitioning patients to alternative therapy classes [

33,

34].

4. The Phase 3 Trial BRUIN CLL-321

Real-world data suggest that following covelent BTK inhibitor (cBTKi) discontinuation, median time-to-treatment-discontinuation ranged across databases (e.g., Flatiron Health electronic health record-derived database and the nationwide Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics

® Data Mart Database) between 6 and 9 months [

35].

No prospective, randomized studies currently evaluate treatment options for relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL following prior cBTKi therapy. For this patient subset, the applicability of the phase III MURANO trial which deomonstrated improved outcomes with venetoclax plus rituximab is limited, as only about 3% (n=5/194) had prior BCRi exposure [

36]. As the population of CLL/SLL patients with prior cBTKi therapy increases, there is a growing need for effective treatments in this subgroup [

37]. The BRUIN CLL-321 phase III randomized study, comparing pirtobrutinib to investigator’s choice consisting of Idelalisib plus rituximab (IdelaR) or bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), is unique as it exclusively enrolled in a prospective, randomized study patients previously treated with cBTKi [

38].

This study enrolled 238 patients, previously exposed to covalent BTKis who were randomly assigned to either receive pirtobrutinib (n = 119) or investigator’s choice (IC) (n = 119; including IdelaR [n = 82] and BR [n = 37]). The hazard ratio (HR) for PFS was 0.54 (95% CI, 0.39 to 0.75; P =.0002), with median PFS of 14 months (95% CI, 11.2 to 16.6) for the pirtobrutinib group compared to 8.7 months for the IC group. The unadjusted overall survival (OS) HR was 1.09 ( P = 0.7202), with 18-month OS rates of 73.4% in the pirtobrutinib arm versus 70.8% in the IC arm. The median time to next treatment (TTNT) was 24 months with pirtobrutinib, compared to 10.9 months with IC (P<0.0001). After a median follow-up of 17.2 months, grade ≥3 treatment-emergent AEs were observed less frequently in the pirtobrutinib group (57.7%) than in the IC group (73.4%). Treatment discontinuation due to AEs occurred in 20 patients (17.2%) on pirtobrutinib and 38 patients (34.9%) on IC [

38].

These results appear of relevance when it is considered that patients enrolled in the study were heavily pretreated with half previously treated with venetoclax, and 70% with chemotherapy and/or anti-CD20 antibody treatments. Of note, treatment benefits with pirtobrutinib were consistent across important subgroups, including those with high-risk features such as del(17p)/TP53 mutations, complex karyotype, and unmutated IGHV [

38].

Data derived from the BRUIN CLL-321 clinical trial indicate that pirtobrutinib achieves a median TTNT of approximately 2.5 years in patients who are naïve to venetoclax therapy, and approximately 1.7 years in patients with prior exposure to venetoclax [

38]. TTNT is a critically important endpoint as it provides a patient-centered measure of therapeutic durability and clinical benefit [

39,

40]. These findings imply that sequencing pirtobrutinib following venetoclax treatment may constitute a viable therapeutic approach, especially considering the observed differences in TTNT based on prior venetoclax exposure [

38]. A retrospective analysis conducted by Thompson et al., suggest that venetoclax maintains its efficacy after treatment with non-covalent BTK inhibitors [

41]. However, it is important to note that prospective studies evaluating this sequence are currently limited, and further clinical investigation is warranted to confirm these observations and optimize sequencing strategies in CLL management.

Finally, the BRUIN CLL-321 study confirmed that pirtobrutinib possesses a safety profile consistent with earlier phase 1/2 studies. Discontinuation due to adverse events was low (5.2%), and the incidences of atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and major bleeding were infrequent. Notably, patients with a history of atrial fibrillation/flutter did not exhibit an increased risk of cardiac adverse events. Most bleeding episodes were mild in severity, and no cases of Richter transformation were observed during treatment with pirtobrutinib [

38].

5. Pirtobrutinib in Patients in RICHTER Transformation

Preliminary results showed that pirtobrutinib demonstrated promising efficacy and a favorable safety profile in heavily pretreated patients with Richter transformation. Specifically, 6 out of 9 patients achieved at least a partial response, despite all having prior exposure to covalent BTK inhibitors [

31]. The Phase II BRUIN study included a subgroup consisting of 82 patients diagnosed with Richter transformation. At baseline, the median age within this subgroup was 67 years, with approximately two-thirds of the patients being male, reflecting the demographic characteristics typically observed in this patient population [

42]. A substantial proportion, approximately 90%,had previously received at least one systemic therapy targeting Richter transformation. Moreover, 74% had been treated with a cBTKi, indicating a heavily pretreated cohort with limited therapeutic options. The study findings demonstrated that pirtobrutinib elicited an ORR of 50%, with a complete remission (CR) rate of 13%. Among responders, eight patients continued on therapy and subsequently underwent stem cell transplantation, highlighting the potential role of pirtobrutinib as a bridge to potentially curative strategies [

42].

The median PFS was 3.7 months, while the median OS was 12.5 months. The 2-year OS rate was 33.5%, a notable outcome given the historically poor prognosis associated with Richter transformation. Importantly, for a disease with limited treatment options, pirtobrutinib demonstrated single-agent activity and served as a bridge to potentially curative therapies. These results support ongoing investigations of pirtobrutinib, both as monotherapy and in combination with other agents, as a promising therapeutic strategy for patients with Richter transformation [

42].

Additionally, it is important to recognize that approximately 20% of patients with Richter transformation (RT) are typically older and have substantial comorbidities, making them suitable candidates for palliative therapy [

43]. In this subset, single-agent pirtobrutinib may constitute a reasonable therapeutic option.

6. Pirtobrutinib in Fixed-Duration Regimens

While fixed-duration regimens combining cBTKi with venetoclax are well established in the upfront treatment of CLL, their application in relapsed/refractory (R/R) settings remains limited [

44]. This is particularly relevant given that many patients receive covalent BTK inhibitors as continuous frontline therapy, thereby diminishing the applicability of combination strategies in relapsed scenarios [

44].

In a phase 1b study, pirtobrutinib demonstrated notable efficacy when combined with venetoclax, with or without rituximab, in patients with R/R CLL. The overall ORR was 96%, with 40% of patients achieving CR. The 24-month PFS was 79.5%. Importantly, these responses were observed in a heavily pretreated population, with 68% having prior exposure to covalent BTK inhibitors, of whom 71% exhibited resistance to these agents. Additionally, the rate of undetectable measurable residual disease (uMRD) with a sensitivity of 10

-4 in peripheral blood after twelve cycles was 70.8%. Early discontinuation due to disease progression was rare, occurring in only two patients. Pharmacokinetic analyses indicated no significant drug–drug interactions between pirtobrutinib and venetoclax, with exposure levels comparable to monotherapy [

45].

These results further indicate that fixed-duration pirtobrutinib and venetoclax regimens are well tolerated and demonstrate sufficiently promising efficacy to warrant further investigation in this patient population.

Ongoing and planned studies include BRUIN CLL-322 (NCT04965493), a phase 3 trial comparing fixed-duration pirtobrutinib–venetoclax–rituximab (PVR) with venetoclax–rituximab (VR) in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL who have progressed after covalent BTKi therapy. This study represents the first large, time-limited venetoclax-based combination in a post-covalent BTKi setting, with approximately 80% of enrolled patients expected to be BTKi pretreated. Additional pirtobrutinib-based combinations are under evaluation, including the time-limited triplet of pirtobrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab (PVO) for treatment-naïve CLL or Richter transformation (NCT05536349, NCT05677919). Furthermore, the investigator-initiated phase 3 CLL-18 trial (NCT06588478) is planned to evaluate pirtobrutinib in combination with venetoclax versus obinutuzumab plus venetoclax, employing an MRD-guided approach (Table 1).

7. Pirtobrutinib Resistance and the Strategic Integration in CLL Management

Data from the BRUIN trials underscore the efficacy of pirtobrutinib in heavily pretreated patients with inclusion of those with dual-refractory disease, resistant to both cBTKis and venetoclax [

30,

31,

38].

Despite these promising outcomes, a subset of patients ultimately develop acquired resistance to pirtobrutinib itself [

30,

31,

38,

46]. Post-hoc analyses of the BRUIN cohort reveal that approximately 68% of patients experience disease progression accompanied by the emergence of mutations. Notably, BTK mutations are identified in 44% of cases, with PLCγ2 mutations present in 24%. Among these, mutations such as T474 and L528W are particularly prevalent, suggesting their significant role in resistance mechanisms [

47].

Clinically, the mutational phenotype appears to contribute, at least in part, to the relatively short duration of responses observed after pirtobrutinib, with median remissions lasting approximately 8 months, especially in double-refractory patients [

38,

47].

A recent post-hoc analysis of the phase 1/2 BRUIN trial further elucidated the molecular landscape of pirtobrutinib response in patients with CLL previously treated with cBTKis [

48]. The study focused on factors influencing sustained response versus disease progression and explored the potential for re-sensitization to cBTKis or other targeted therapies. Notably, early progressors, defined as those exhibiting disease progression within 24 cycles, more frequently had a history of cBTKi resistance and exhibited complex karyotypes. Patients harboring baseline BTK mutations, especially non-C481 variants, initially responded but eventually developed resistance, suggesting a mutator phenotype. Conversely, individuals with wild-type BTK or no detectable mutations experienced longer remissions, indicating that pirtobrutinib may have particular benefit in BTK inhibitor-naïve settings [

48].

These data underscore the potential efficacy of pirtobrutinib, particularly in patients with double-refractory CLL, but they also suggest that a durable advantage will likely require integration of pirtobrutinib within a broader sequence that includes T-cell–engager therapies [

30,

31,

38,

49]. A promising strategy is to employ pirtobrutinib to sustain disease control during a bridging period, with the aim of reducing tumor burden and mitigating related toxicities, and in selected patients, to switch to approaches capable of inducing deeper responses, such as CAR-T cell therapy [

49]. Strategically incorporating pirtobrutinib into individualized treatment pathways with carefully timed transitions to cellular therapies may maximize the likelihood of long-term disease control and potential cure.

8. Improving BTKi-Safety with Pirtobrutinib

The interaction between BTK inhibitor therapy and individual patient comorbidities significantly influences toxicity profiles in CLL [

12,

50]. Many CLL patients are concurrently receiving antithrombotic therapy at treatment initiation, which elevates their risk for bleeding complications [

12]. An analysis of bleeding events from the phase 1/2 BRUIN study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03740529), involving 773 patients treated with pirtobrutinib monotherapy, offers valuable insights into this interaction. Patients were stratified based on antithrombotic therapy exposure: 216 were antithrombotic therapy exposed (AT-E), and 557 were not (AT-NE). The AT-E group primarily received platelet inhibitors (51.9%), direct factor Xa inhibitors (36.6%), heparins (18.5%), salicylic acid derivatives (5.6%), and thrombolytics (2.3%), with warfarin contraindicated [

51].

Bleeding or bruising events occurred in 44.9% of AT-E patients compared to 32.5% of AT-NE patients, predominantly within the first six months of therapy, with contusions being the most common. Grade ≥3 bleeding events were infrequent (2.8% in AT-E and 2.0% in AT-NE), with only one patient requiring dose reduction. These findings suggest that pirtobrutinib maintains an acceptable safety profile even in patients on concomitant antithrombotic agents [

51].

Beyond bleeding, infection and cardiovascular risks remain central considerations [

12]. Despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic during the trial period, no patients discontinued therapy due to recurrent infections, indicating that pirtobrutinib’s infectious risk profile is favorable. This is particularly relevant considering the immunodeficiency inherent to CLL, affecting both humoral and cellular immunity [

32,

52]. Regarding cardiovascular safety, data demonstrated that most patients with prior cardiac events did not experience recurrence, and no discontinuations due to cardiac adverse events (AEs) occurred—an encouraging contrast to the discontinuation rates seen with other covalent BTK inhibitors [

32].

These observations collectively support the hypothesis that pirtobrutinib offers a superior safety profile relative to covalent BTK inhibitors, with lower incidences of cardiac, infectious, and bleeding toxicities [

53]. To facilitate personalized treatment decisions, especially in elderly patients with complex comorbidities, we proposed the ‘CIRB’ criteria—a practical screening tool designed to evaluate key organ system vulnerabilities. The CIRB acronym encompasses Cardiovascular (C), Immunosuppression (I), Renal (R), and Bleeding risk (B), including factors such as concomitant dual antiplatelet therapy [

54]. Compared to existing tools like the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS), the CIRB aims to more effectively capture the interplay between BTK inhibitor-related toxicities and patient-specific comorbidities, thereby guiding clinicians in selecting the most appropriate therapeutic strategy—whether pirtobrutinib or covalent BTK inhibitors [

54].

The ongoing phase 3 BRUIN CLL-314 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05254743) is directly comparing the efficacy and safety of pirtobrutinib versus ibrutinib in both treatment-naïve and previously treated CLL/SLL populations. Early results demonstrate non-inferiority in overall response rate (ORR), with safety profiles consistent with prior studies. Full trial results are anticipated to be presented at the 2025 American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting, potentially establishing pirtobrutinib as a cornerstone of personalized CLL management.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, pirtobrutinib emerges as a potentially transformative agent within the evolving therapeutic landscape of chronic CLL, particularly for patient cohorts with limited treatment options due to intolerance or resistance to conventional covalent BTK inhibitors (

Figure 2). Its favorable tolerability profile enables a safe administration in heavily pretreated populations, including those with dual resistance, underscoring its promise as an effective salvage therapy.

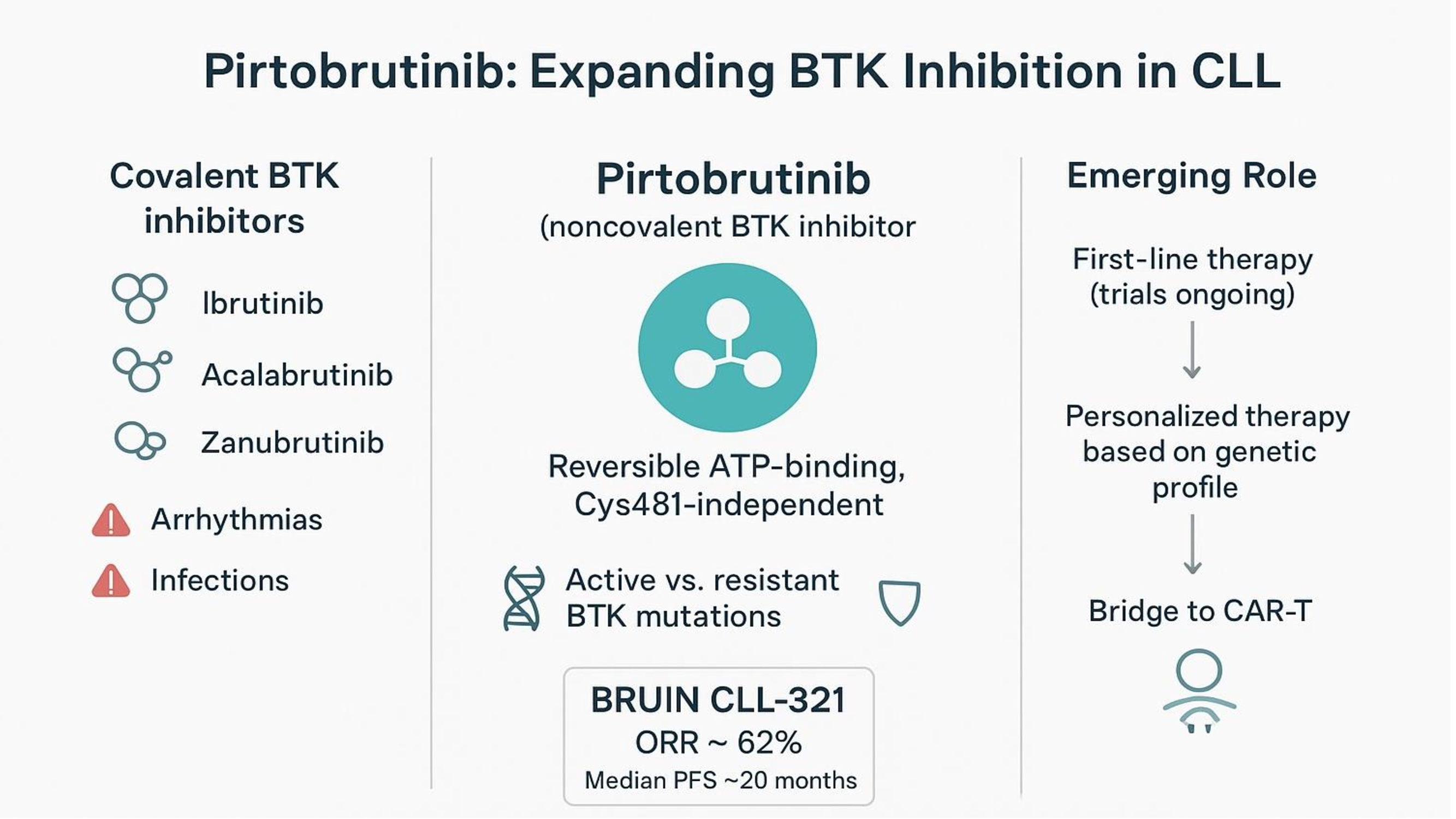

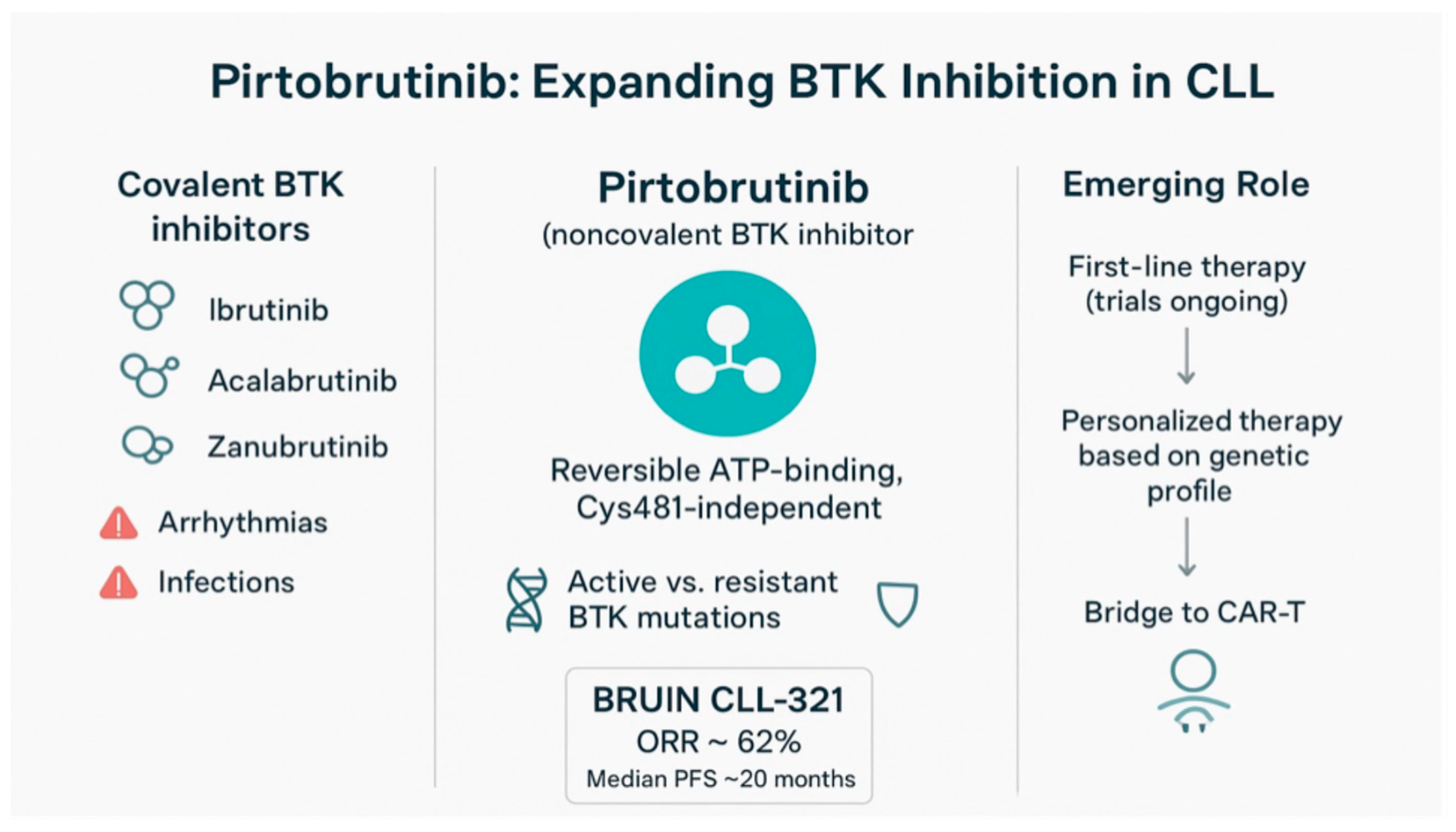

Figure 2.

An optimal therapeutic sequence for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), transitioning from covalent to non-covalent BTK inhibition (pirtobrutinib), is depicted. The figure highlights the emerging role of pirtobrutinib in first-line treatment and its potential to complement chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. These are original figures generated using a Chat-GPT 5.0.

Figure 2.

An optimal therapeutic sequence for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), transitioning from covalent to non-covalent BTK inhibition (pirtobrutinib), is depicted. The figure highlights the emerging role of pirtobrutinib in first-line treatment and its potential to complement chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. These are original figures generated using a Chat-GPT 5.0.

Resistance to pirtobrutinib often results from mutations in BTK, with certain mutations like A428D, T474I, and L528W potentially causing cross-resistance to other BTK inhibitors [

27]. Although these patterns may influence future treatment sequencing, current understanding is limited, and optimal strategies for managing resistance are unclear [

27]. In this setting, there is potential for BTK degrader agents that can degrade BTK irrespective of its mutation status, thereby targeting both wild-type and mutant BTK proteins.

Importantly, insights into the molecular determinants of response reveal that baseline genetic characteristics and prior treatment history significantly influence the durability of remission—patients with wild-type BTK tend to experience longer-lasting disease control, while those with complex genetic aberrations may encounter earlier progression [

48]. This underscores the necessity of integrating pirtobrutinib within comprehensive, multimodal treatment strategies, such as bridging to advanced immunotherapies like CAR-T, to optimize outcomes and potentially enhance the efficacy of subsequent interventions [

56]. Safety considerations, including manageable bleeding risks and a low incidence of cardiovascular or infectious adverse events, further support its clinical utility, especially given the typical age and comorbidities of the CLL population [

10,

30,

31,

38]. Preliminary data from ongoing comparative trials suggest that pirtobrutinib may offer non-inferior efficacy relative to established agents like ibrutinib, with a consistent safety profile. As further evidence matures, pirtobrutinib is poised to solidify its role in first-line and combination regimens, with ongoing investigations into resistance mechanisms and personalized treatment algorithms critical for extending remission and moving toward potential cures [

55]. Ultimately, pirtobrutinib exemplifies how targeted, precision medicine approaches can significantly enhance disease management, improve patient quality of life, and shape the future of CLL therapy.

Author Contributions

S.M. and D.A. equally contributed to this paper.

Funding

This paper was not funded.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this paper , data availability is inherent to references.

Conflicts of Interest

SM received consulting honoraria from Janssen, AbbVie, Astra-Zeneca; DA received travel sponsorship from Gilead and Beigene. He i salso local investigator on Ely Lilly sponsored studies of pirtobrutinib. Local prinviple investigator for Beigene sponsored study.

References

- O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Sharman JP, Burger JA, Blum KA, Grant B, Richards DA, Coleman M, Wierda WG, et al. Ibrutinib as Initial Therapy for Elderly Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia or Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: An Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 1b/2 Trial,” Lancet Oncol. 2014 Jan;15(1):48-58. [CrossRef]

- Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Bairey O, Hillmen P, Bartlett NL, Li J, et al. Ibrutinib as Initial Therapy for Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 17;373(25):2425-2437.

- Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T Prof, Owen C, Tedeschi A, Sarma A, Patten PE, Grosicki S, McCarthy H Dr, Offner F, et al. Final analysis of the RESONATE-2 study: up to 10 years of follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment for CLL/SLL. Blood. 2025 Jul 30:blood.2024028205. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Wang, X.V.; Kay, N.E.; Hanson, C.A.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.; Jelinek, D.F.; Braggio, E.; Leis, J.F.; Zhang, C.C.; et al. Ibrutinib- Rituximab or Chemoimmunotherapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 432–443.

- Woyach, J.A.; Ruppert, A.S.; Heerema, N.A.; Zhao, W.; Booth, A.M.; Ding, W.; Bartlett, N.L.; Brander, D.M.; Barr, P.M.; Rogers, K.A.; et al. Ibrutinib Regimens versus Chemoimmunotherapy in Older Patients with Untreated CLL. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2517–2528. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Greil, R.; Demirkan, F.; Tedeschi, A.; Anz, B.; Larratt, L.; Simkovic, M.; Samoilova, O.; Novak, J.; Ben-Yehuda, D.; et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): A multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 43–56.

- Munir, T.; Brown, J.R.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.C.; Barr, P.M.; Reddy, N.M.; Coutre, S.; Tam, C.S.; Mulligan, S.P.; Jaeger, U.; et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: Up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 1353–1363. [CrossRef]

- Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, Skarbnik A, Pagel JM, Flinn IW, Kamdar M, Munir T, Walewska R, Corbett G, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzmab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020 Apr 18;395(10232):1278-1291.

- Shadman M, Munir T, Robak T, Brown JR, Kahl BS, Ghia P, Giannopoulos K, Šimkovič M, Österborg A, Laurenti L, et al. Zanubrutinib Versus Bendamustine and Rituximab in Patients With Treatment-Naïve Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: Median 5-Year Follow-Up of SEQUOIA. J Clin Oncol 2025 Mar;43(7):780-787.

- Tam C, Thompson PA. BTK inhibitors in CLL: second-generation drugs and beyond.Blood Adv. 2024 May 14;8(9):2300-2309. [CrossRef]

- Huntington SF, de Nigris E, Puckett J, Kamal-Bahl S, Farooqui M, Ryland K, Sarpong E, Leng S, Yang X, Doshi JA. Ibrutinib discontinuation and associated factors in a real-world national sample of elderly Medicare beneficiaries with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma[ 2023 Dec;64(14):2286-2295.

- Lipsky, A.; Lamanna, N. Managing toxicities of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2020, 2020, 336–345.

- Dickerson, T.; Wiczer, T.; Waller, A.; Philippon, J.; Porter, K.; Haddad, D.; Guha, A.; Rogers, K.A.; Bhat, S.; Byrd, J.C.; et al. Hypertension and incident cardiovascular events following ibrutinib initiation. Blood 2019, 134, 1919–1928. [CrossRef]

- Molica S, Allsup D, Giannarelli D. Prevalence of BTK and PLCG2 Mutations in CLL Patients With Disease Progression on BTK Inhibitor Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Hematol. 2025 Feb;100(2):334-337.

- Byrd, J.C.; Hillmen, P.; Ghia, P.; Kater, A.P.; Chanan-Khan, A.; Furman, R.R.; O’Brien, S.; Yenerel, M.N.; Illés, A.; Kay, N.; et al. Acalabrutinib Versus Ibrutinib in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results of the First Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3441–3452. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Eichhorst, B.; Hillmen, P.; Jurczak, W.; Kaźmierczak, M.; Lamanna, N.; O’Brien, S.M.; Tam, C.S.; Qiu, L.; Zhou, K.; et al. Zanubrutinib or Ibrutinib in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 319–332. [CrossRef]

- Pan Z, Scheerens H, Li SJ, et al. Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Chem Med Chem. 2007;2(1):58-61.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42.

- Guo Y, Liu Y, Hu N, et al. Discovery of zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), a novel, potent, and selective covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2019;62(17):7923-7940.

- Alu A, Lei H, Han X, Wei Y, Wei X. BTK inhibitors in the treatment of hematological malignancies and inflammatory diseases: mechanisms and clinical studies.J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Oct 1;15(1):138. [CrossRef]

- Gruessner C, Wiestner A, Sun C. Resistance mechanisms and approach to chronic lymphocytic leukemia after BTK inhibitor therapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2025 Jul;66(7):1176-1188.

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTK(C481S)-mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1437-1443.

- Molica S, Allsup D. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL): A Clinical View. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2025 Jul 1;17(1):e2025053.

- Gomez EB, Ebata K, Randeria HS, Rosendahl MS, Cedervall EP, Morales TH, Hanson LM, Brown NE, Gong X, Stephens J, et al. Preclinical characterization of pirtobrutinib, a highly selective, noncovalent (reversible) BTK inhibitor. Blood. 2023 Jul 6;142(1):62-72.

- Bravo-Gonzalez A, Alasfour M, Soong D, Noy J, Pongas G. Advances in Targeted Therapy: Addressing Resistance to BTK Inhibition in B-Cell Lymphoid Malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Oct 10;16(20):3434.

- Thompson PA, Tam CS. Pirtobrutinib: a new hope for patients with BTK inhibitor-refractory lymphoproliferative disorders.Blood. 2023 Jun 29;141(26):3137-3142. [CrossRef]

- Tam CS, Balendran S, Blombery P. Novel mechanisms of resistance in CLL: variant BTK mutations in second-generation and noncovalent BTK inhibitors. Blood. 2025 Mar 6;145(10):1005-1009.

- Naeem A, Utro F, Wang Q, Cha J, Vihinen M, Martindale S, Zhou Y, Ren Y, Tyekucheva S, Kim AS, et al. Pirtobrutinib targets BTK C481S in ibrutinib-resistant CLL but second-site BTK mutations lead to resistance. Blood Adv. 2023 May 9;7(9):1929-1943. [CrossRef]

- Aslan B, Kismali G, Iles LR, Manyam GC, Ayres ML, Chen LS, Gagea M, Bertilaccio MTS, Wierda WG, Gandhi V. Pirtobrutinib inhibits wild-type and mutant Bruton’s tyrosine kinase-mediated signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2022 May 20;12(5):80. [CrossRef]

- Mato AR, Shah NN, Jurczak W, Cheah CY, Pagel JM, Woyach JA, Fakhri B, Eyre TA, Lamanna N, Patel MR, et al. Pirtobrutinib in relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies (BRUIN): a phase 1/2 study. Lancet. 2021 Mar 6;397(10277):892-901.

- Mato AR, Woyach JA, Brown JR, Ghia P, Patel K, Eyre TA, Munir T, Lech-Maranda E, Lamanna N, Tam CS, et al. Pirtobrutinib after a Covalent BTK Inhibitor in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jul 6;389(1):33-44.

- Shah NN, Wang M, Roeker LE, Patel K, Woyach JA, Wierda WG, Ujjani CS, Eyre TA, Zinzani PL, Alencar AJ,et al Pirtobrutinib monotherapy in Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor-intolerant patients with B-cell malignancies: results of the phase I/II BRUIN trial Haematologica. 2025 Jan 1;110(1):92-102.

- Al-Sawaf O, Jen MH, Hess LM, Zhang J, Goebel B, Pagel JM, Abhyankar S, Davids MS, Eyre TA. Pirtobrutinib versus venetoclax in covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor-pretreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a matching-adjusted indirect comparison.Haematologica. 2024 Jun 1;109(6):1866-1873. [CrossRef]

- Rogers KA. Choosing between CAR T-cell therapy and pirtobrutinib in double-refractory CLL. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2024 Dec;22(10):494-496.

- Jain N, Eyre TA, Winfree KB, Bhandari NR, Khanal M, Sugihara T, Chen Y, Abada P, Patel K. Real-world outcomes after discontinuation of covalent BTK inhibitor-based therapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2025 Aug;66(8):1400-1412.

- Kater AP, Harrup R, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, Owen CJ, Assouline S, Lamanna N, Robak T, de la Serna J, Jaeger U, et al. The MURANO study: final analysis and retreatment/crossover substudy results of VenR for patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. Blood. 2025 Jun 5;145(23):2733-2745.

- Huntington SF, de Nigris E, Puckett J, Kamal-Bahl S, Farooqui M, Ryland K, Sarpong E, Leng S, Yang X, Doshi JA. Ibrutinib discontinuation and associated factors in a real-world national sample of elderly Medicare beneficiaries with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023 Dec;64(14):2286-2295.

- Sharman JP, Munir T, Grosicki S, Roeker LE, Burke JM, Chen CI, Grzasko N, Follows G, Mátrai Z, Sanna A, et al. Phase III Trial of Pirtobrutinib Versus Idelalisib/Rituximab or Bendamustine/Rituximab in Covalent Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Pretreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (BRUIN CLL-321). J Clin Oncol. 2025 Aug;43(22):2538-2549.

- Delgado, A.; Guddati, A.K. Clinical endpoints in oncology—A primer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 1121–1131.

- Molica S. Redefining efficacy and safety endpoints for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of targeted therapy. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023 Jul-Dec;16(11):803-806. [CrossRef]

- Thompson MC, Bhat SA, Jurczak W, Patel K, Shah NN, Woyach JA, Coombs CC, Eyre TA, Danecki M, Dlugosz-Danecka M, et al. Outcomes of Therapies Following Discontinuation of Non-Covalent Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Richter Transformation: Results from an International, Multicenter Study. Blood (2024) 144 (Supplement 1): 1870.

- Wierda WG, Shah NN, Cheah CY, Lewis D, Hoffmann MS, Coombs CC, Lamanna N, Ma S, Jagadeesh D, Munir T, et al. Pirtobrutinib, a highly selective, non-covalent (reversible) BTK inhibitor in patients with B-cell malignancies: analysis of the Richter transformation subgroup from the multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 BRUIN study. Lancet Haematol. 2024 Sep;11(9):e682-e692. [CrossRef]

- Eyre TA. Richter transformation-is there light at the end of this tunnel?Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2023 Dec 8;2023(1):427-432.

- Molica S. Navigating the gap between guidelines and practical challenges in selecting first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2025 Jan-Mar;18(3):195-200.

- Roeker LE, Woyach JA, Cheah CY, Coombs CC, Shah NN, Wierda WG, Patel MR, Lamanna N, Tsai DE, Nair B, et al. Fixed-duration pirtobrutinib plus venetoclax with or without rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL: the phase 1b BRUIN trial. Blood. 2024 Sep 26;144(13):1374-1386. [CrossRef]

- Qi J, Endres S, Yosifov DY, Tausch E, Dheenadayalan RP, Gao X, Müller A, Schneider C, Mertens D, Gierschik P, et al. Acquired BTK mutations associated with resistance to noncovalent BTK inhibitors. Blood Adv. 2023 Oct 10;7(19):5698-5702.

- Brown J, Desikan S, Nguyen B, Won H, Tantawy SI, McNeely S, Marella N, Ebata K, Woyach JA, Patel K, et al. Genomic evolution and resistance during pirtobrutinib therapy in covalent BTK-inhibitor (cBTKi) pretreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients: updated analysis from the BRUIN study [abstract]. Blood. 2023;142(suppl 1):326.

- Gandhi V, Tantawy S, Aslan B, Manyam G, Iles L, Timofeeva N, Singh N, Jain N, Ferrajoli A, Thompson P, et al. Pharmacological profiling in CLL patients during pirtobrutinib therapy and disease progression. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2025 Mar 31:rs.3.rs-6249480. [Version 1]. [CrossRef]

- Shadman M, Davids MS.How I treat patients with CLL after prior treatment with a covalent BTK inhibitor and a BCL-2 inhibitor. Blood. 2025 Jul 29:blood.2024025482. Online ahead of print. PMID: 40729699. [CrossRef]

- Molica S, Allsup D Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Care and Beyond: Navigating the Needs of Long-Term Survivors. Cancers (Basel). 2025 Jan 2;17(1):119. [CrossRef]

- Lamanna N, Tam CS, Woyach JA, Alencar AJ, Palomba ML, Zinzani PL, Flinn IW, Fakhri B, Cohen JB, Kontos A, et al. Evaluation of bleeding risk in patients who received pirtobrutinib in the presence or absence of antithrombotic therapy. EJHaem. 2024 Sep 27;5(5):929-939. [CrossRef]

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL.Blood. 2015 Jul 30;126(5):573-581.

- Shah PV, Gladstone DE. Covalent and Non-Covalent BTK Inhibition in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2025 Jul 18. [CrossRef]

- Molica S. Defining treatment success in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: exploring surrogate markers, comorbidities, and patient-centered endpoints. Expert Rev Hematol. 2024 Jul;17(7):279-285.

- Montoya S, Bourcier J, Noviski M, Lu H, Thompson MC, Chirino A, Jahn J, Sondhi AK, Gajewski S, Tan YSM, et al. Kinase-impaired BTK mutations are susceptible to clinical-stage BTK and IKZF1/3 degrader NX-2127. Science. 2024 Feb 2;383(6682):eadi5798.

- Shadman M, Davids MS How I treat patients with CLL after prior treatment with a covalent BTK inhibitor and a BCL-2 inhibitor. Blood. 2025 Jul 29:blood.2024025482. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).