Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Donor Variables

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

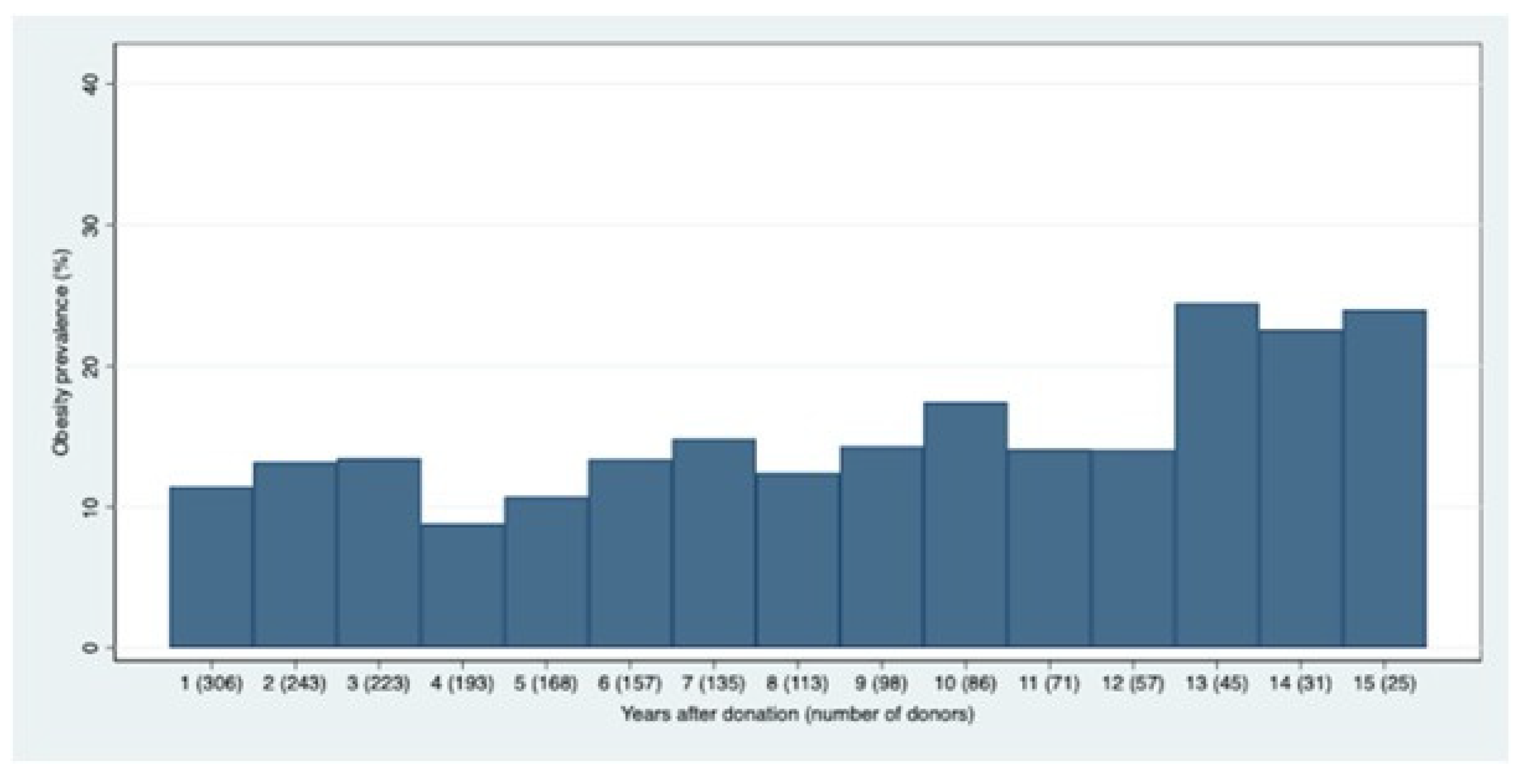

3.2. Evaluation of Obesity Prevalence and Predictors

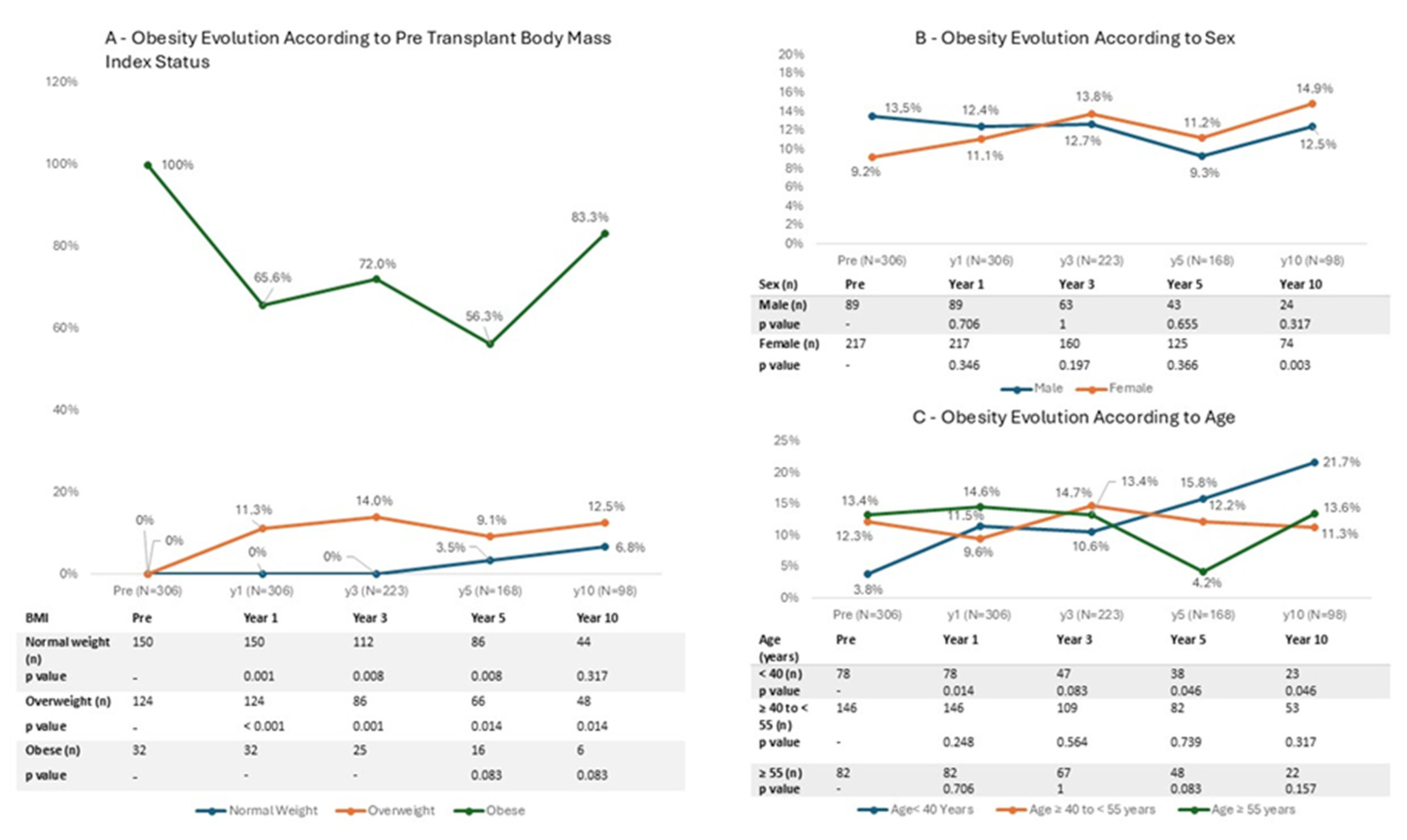

3.3. Trends in BMI Categories

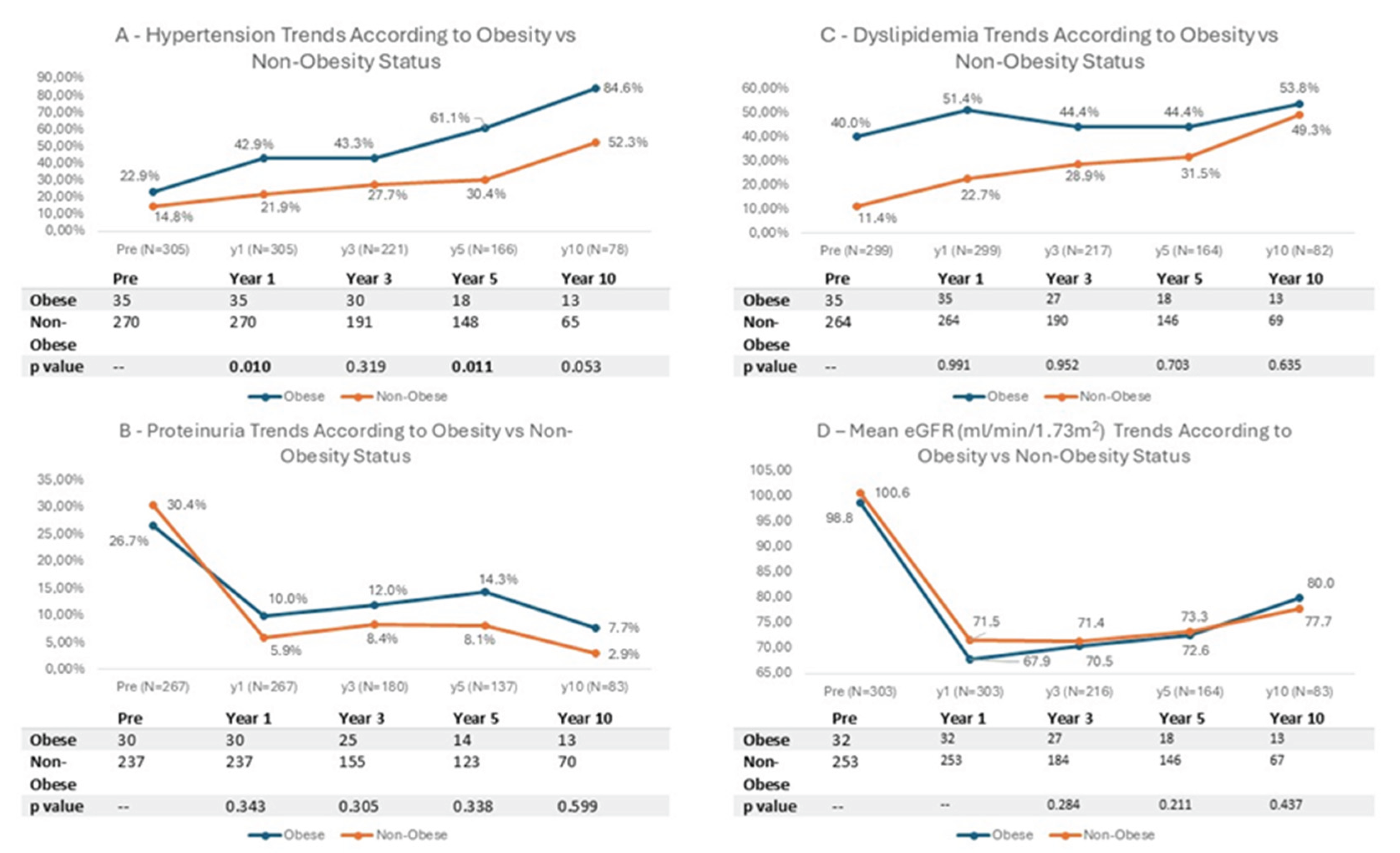

3.3. Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Kidney Function Trends According to BMI

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| ESKD | End Stage Kidney Disease |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| LKD | Living Kidney Donor |

| LKDT | Living Kidney Donor Transplantation |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, R.A.; Ashby, V.B.; Milford, E.L.; Ojo, A.O.; Ettenger, R.E.; Agodoa, L.Y.C.; Held, P.J.; Port, F.K. Comparison of Mortality in All Patients on Dialysis, Patients on Dialysis Awaiting Transplantation, and Recipients of a First Cadaveric Transplant. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 341, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, A.R.; Lafranca, J.A.; Claessens, L.A.; Imamdi, R.M.S.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; Betjes, M.G.H.; Dor, F.J.M.F. Shifting Paradigms in Eligibility Criteria for Live Kidney Donation: A Systematic Review. Kidney Int 2015, 87, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atividade Nacional Anual; 2021.

- McCormick, F.; Held, P.J.; Chertow, G.M. The Terrible Toll of the Kidney Shortage. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2018, 29, 2775–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Escoli, R.; Eusébio, C.; Dias, L.; Almeida, M.; Martins, L.S.; Pedroso, S.; Henriques, A.C.; Cabrita, A. A Survival Analysis of Living Donor Kidney Transplant. Transplant Proc 2019, 51, 1575–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M. Weight Trends in United States Living Kidney Donors: Analysis of the UNOS Database. World J Transplant 2015, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.B.; Santos, D.A.; Silva, A.M.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.J.; Raimundo, A.M.; Moreira, H.; Santos, R.; Vale, S.; Baptista, F.; Mota, J. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Abdominal Obesity in a Representative Sample of Portuguese Adults. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, K.; Kuah, R.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Lam, T.K.T. Obesity and the Kidney: Mechanistic Links and Therapeutic Advances. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2024, 20, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.H.; Chang, T.I.; Joo, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Yun, H.; Park, J.T.; Yoo, T.; Sung, S.A.; et al. Association Between Serum High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels and Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: Results From the KNOW-CKD. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agati, V.D.; Chagnac, A.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Levi, M.; Porrini, E.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Praga, M. Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy: Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics and Pathogenesis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016, 12, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, F.; Deprele, C.; Sassolas, A.; Moulin, P.; alamartine, E.; Berthezène, F.; Berthoux, F. Excessive Body Weight as a New Independent Risk Factor for Clinical and Pathological Progression in Primary IgA Nephritis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2001, 37, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.A.; Kramer, H.; Bidani, A.K. Adverse Renal Consequences of Obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2008, 294, F685–F696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzullo, P.; Barba, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Siani, A.; Trevisan, M.; Farinaro, E.; Pagano, E.; Barbato, A.; Iacone, R.; Galletti, F. Altered Renal Sodium Handling in Men with Abdominal Adiposity: A Link to Hypertension. J Hypertens 2001, 19, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeli, S.; Böhnke, J.; Gorzelniak, K.; Janke, J.; Schling, P.; Bader, M.; Luft, F.C.; Sharma, A.M. Weight Loss and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. Hypertension 2005, 45, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, N.; Okabayashi, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Yokoo, T. The Renal Pathology of Obesity. Kidney Int Rep 2017, 2, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, A.P.J.; Ruggenenti, P.; Ruan, X.Z.; Praga, M.; Cruzado, J.M.; Bajema, I.M.; D’Agati, V.D.; Lamb, H.J.; Barlovic, D.P.; Hojs, R.; et al. Fatty Kidney: Emerging Role of Ectopic Lipid in Obesity-Related Renal Disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014, 2, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Ucku, D.; Zoccali, C. Donor Obesity and Weight Gain after Transplantation: Two Still Overlooked Threats to Long-Term Graft Survival. Clin Kidney J 2023, 16, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M. Should Obesity Affect Suitability for Kidney Donation? Semin Dial 2018, 31, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.R.; Lafranca, J.A.; Claessens, L.A.; Imamdi, R.M.S.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; Betjes, M.G.H.; Dor, F.J.M.F. Shifting Paradigms in Eligibility Criteria for Live Kidney Donation: A Systematic Review. Kidney Int 2015, 87, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J.E.; Reed, R.D.; Massie, A.; MacLennan, P.A.; Sawinski, D.; Kumar, V.; Mehta, S.; Mannon, R.B.; Gaston, R.; Lewis, C.E.; et al. Obesity Increases the Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease among Living Kidney Donors. Kidney Int 2017, 91, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.N.; Foley, R.N.; Reule, S.A.; Spong, R.; Kukla, A.; Issa, N.; Berglund, D.M.; Sieger, G.K.; Matas, A.J. Renal Function Profile in White Kidney Donors: The First 4 Decades. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2016, 27, 2885–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, A.B.; Muzaale, A.D.; Luo, X.; Chow, E.K.H.; Locke, J.E.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Henderson, M.L.; Snyder, J.J.; Segev, D.L. Quantifying Postdonation Risk of ESRD in Living Kidney Donors. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017, 28, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaale, A.D.; Massie, A.B.; Wang, M.-C.; Montgomery, R.A.; McBride, M.A.; Wainright, J.L.; Segev, D.L. Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease Following Live Kidney Donation. JAMA 2014, 311, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mjøen, G.; Hallan, S.; Hartmann, A.; Foss, A.; Midtvedt, K.; Øyen, O.; Reisæter, A.; Pfeffer, P.; Jenssen, T.; Leivestad, T.; et al. Long-Term Risks for Kidney Donors. Kidney Int 2014, 86, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, N.N.; Lentine, K.L.; Garg, A.X. End-Stage Renal Disease Risk in Live Kidney Donors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2014, 23, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese, P.P.; Boudville, N.; Garg, A.X. Living Kidney Donation: Outcomes, Ethics, and Uncertainty. The Lancet 2015, 385, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K.L.; Kasiske, B.L.; Levey, A.S.; Adams, P.L.; Alberú, J.; Bakr, M.A.; Gallon, L.; Garvey, C.A.; Guleria, S.; Li, P.K.-T.; et al. Summary of Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.A.; Burnapp, L. British Transplantation Society / Renal Association UK Guidelines for Living Donor Kidney Transplantation 2018: Summary of Updated Guidance. Transplantation 2018, 102, e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Calheiros Cruz, G.; Sousa, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Ventura, S.; Silvano, J.; Pedroso, S.; Martins, L.S.; Ramos, M.; Malheiro, J. External Validation of the Toulouse-Rangueil Predictive Model to Estimate Donor Renal Function After Living Donor Nephrectomy. Transpl Int 2023, 36, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Silvano, J.; Pedroso, S.; Tafulo, S.; Martins, L.S.; Ramos, M.; Malheiro, J. Living Donors’ Age Modifies the Impact of Pre-Donation Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate on Graft Survival. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann Intern Med 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, D.B.; Arnold, M.; Bakris, G.L.; Bruns, D.E.; Horvath, A.R.; Kirkman, M.S.; Lernmark, A.; Metzger, B.E.; Nathan, D.M. Position Statement Executive Summary: Guidelines and Recommendations for Laboratory Analysis in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Liu, T.; Deng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Ruan, G.; Xie, H.; Song, M.; Lin, S.; Yao, Q.; et al. The Age-related Obesity Paradigm: Results from Two Large Prospective Cohort Studies. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugeja, A.; Harris, S.; Ernst, J.; Burns, K.D.; Knoll, G.; Clark, E.G. Changes in Body Weight Before and After Kidney Donation. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjala, S.R.; Adamjee, Q.; Silas, L.; Gökmen, R.; Karydis, N. Weight Trends in Living Kidney Donors Suggest Predonation Counselling Alone Lacks a Sustainable Effect on Weight Loss: A Single Centre Cohort Study. Transplant International 2021, 34, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, N.; Sánchez, O.A.; Kukla, A.; Riad, S.M.; Berglund, D.M.; Ibrahim, H.N.; Matas, A.J. Weight Gain after Kidney Donation: Association with Increased Risks of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension. Clin Transplant 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, O.A.; Ferrara, L.K.; Rein, S.; Berglund, D.; Matas, A.J.; Ibrahim, H.N. Hypertension after Kidney Donation: Incidence, Predictors, and Correlates. American Journal of Transplantation 2018, 18, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Hwang, H.S.; Yoon, H.E.; Kim, Y.K.; Choi, B.S.; Moon, I.S.; Kim, J.C.; Hwang, T.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Yang, C.W. Long-Term Risk of Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease in Living Kidney Donors. Transplant Proc 2012, 44, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, G.T.; Nolte, C.; Tsinalis, D.; Steiger, J.; Bachmann, L.M. Investigating Kidney Donation as a Risk Factor for Hypertension and Microalbuminuria: Findings from the Swiss Prospective Follow-up of Living Kidney Donors. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Reis Pereira, P.; Silvano, J.; Ribeiro, C.; Pedroso, S.; Tafulo, S.; Martins, L.S.; Silva Ramos, M.; Malheiro, J. Longitudinal Trajectories of Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate in a European Population of Living Kidney Donors. Transplant International 2024, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grams, M.E.; Sang, Y.; Levey, A.S.; Matsushita, K.; Ballew, S.; Chang, A.R.; Chow, E.K.H.; Kasiske, B.L.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Nadkarni, G.N.; et al. Kidney-Failure Risk Projection for the Living Kidney-Donor Candidate. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K.L.; Kasiske, B.L.; Levey, A.S.; Adams, P.L.; Alberú, J.; Bakr, M.A.; Gallon, L.; Garvey, C.A.; Guleria, S.; Li, P.K.-T.; et al. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017, 101, S7–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praga, M.; Hernández, E.; Herrero, J.C.; Morales, E.; Revilla, Y.; Díaz-González, R.; Rodicio, J.L. Influence of Obesity on the Appearance of Proteinuria and Renal Insufficiency after Unilateral Nephrectomy. Kidney Int 2000, 58, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, O.K.; Sengupta, B.; Bangdiwala, A.; Vock, D.M.; Dunn, T.B.; Finger, E.B.; Pruett, T.L.; Matas, A.J.; Kandaswamy, R. Implications of Excess Weight on Kidney Donation: Long-Term Consequences of Donor Nephrectomy in Obese Donors. Surgery 2018, 164, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, P.A.; Burnapp, L. British Transplantation Society / Renal Association UK Guidelines for Living Donor Kidney Transplantation 2018. Transplantation 2018, 102, e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, M.Á.; Crespo, M.; de la Oliva Valentín, M.; Hernández, D.; de Sequera, P.; Domínguez-Gil, B.; Pascual, J. Living-Donor Kidney Transplant: Guidelines with Updated Evidence. Nefrología (English Edition) 2022, 42, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, J.; Cruzado, J.M.; Alonso, Á.; Diekman, F.; Gallego, R.J.; Gutiérrez-Dalmau, Á.; Hernández, D.; Morales, J.M.; Rodrigo, E.; Zárraga, S. Kidney Transplantation Group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology. Nefrología (English Edition) 2013, 33, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafranca, J.A.; Spoon, E.Q.W.; van de Wetering, J.; IJzermans, J.N.M.; Dor, F.J.M.F. Attitudes among Transplant Professionals Regarding Shifting Paradigms in Eligibility Criteria for Live Kidney Donation. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz, D.; Cochat, P.; Claas, F.H.J.; Heemann, U.; Pascual, J.; Dudley, C.; Harden, P.; Hourmant, M.; Maggiore, U.; Salvadori, M.; et al. European Renal Best Practice Guideline on Kidney Donor and Recipient Evaluation and Perioperative Care: FIGURE 1. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2015, 30, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) |

Overweight (BMI 25-29,9 kg/m2) |

Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 306 (100%) | 150 (49%) | 124 (41%) | 32 (10%) | - |

| Age, mean±SD | 47.2±10.7 | 45.4±11.3 | 48.4±10.2 | 50.8±8.8 | 0.009 |

|

Age, n (%) < 40 40-55 >= 55 |

78 (25) 146 (48) 82 (27) |

50 (33) 65 (43) 35 (23) |

25 (20) 63 (51) 36 (29) |

3 (9) 18 (56) 11 (34) |

0.021 |

| Sex F, n (%) | 217 (71) | 114 (76) | 83 (67) | 20 (63) | 0.140 |

| BMI Kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.3±3.4 | 22.5±1.7 | 27.3±1.4 | 31.2±1.1 | - |

| Smoking habits, n (%) | 49 (16) | 32 (21) | 13 (10) | 4 (13) | 0.045 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 44 (14) | 13 (9) | 18 (15) | 13 (41) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mean±SD | 194.3±37.2 | 188.2±36.0 | 196.5±36.2 | 214.3±40.2 | 0.001 |

| HT, n (%) | 48 (16) | 11 (7) | 24 (19) | 13 (41) | <0.001 |

| TAS, mean±SD | 122.5±13.4 | 118.8±12.0 | 125.0±13.3 | 130.0±14.3 | <0.001 |

| TAD, mean±SD | 73.2±8.7 | 71.6±8.2 | 74.2±8.9 | 76.8±8.8 | 0.002 |

| ProtU 0.15-0.5 g/g, n (%) | 87 (28) | 43 (29) | 33 (27) | 11 (34) | 0.683 |

| Serum creatinine, mean±SD | 0.75±0.16 | 0.73±0.15 | 0.76±0.17 | 0.78±0.15 | 0.115 |

| Pre- donation eGFR ml/min/1.73m2, mean ± SD | 100.3±14.6 | 102.4±15.0 | 98.9±13.9 | 96.3±14.5 | 0.038 |

|

Pre- donation eGFR ml/min/1.73m2, n (%) <80 80-90 >=90 |

27 (9) 47 (15) 232 (76) |

14 (9) 17 (11) 119 (79) |

10 (8) 22 (18) 92 (74) |

3 (9) 8 (25) 21 (66) |

0.278 |

| Related donor, n (%) | 104 (34) | 52 (35) | 40 (32) | 12 (38) | 0.830 |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) |

P | |

|---|---|---|

| Time post-donation | 0.985 (0.844-1.150) | 0.848 |

| Age | 0.882 (0.808-0.963) | 0.005 |

| Female Sex | 3.250 (0.731-14.453) | 0.122 |

| BMI Kg/m2 | 5.324 (3.471-8.168) | <0.001 |

| Smoking habits | 0.450 (0.055-3.647 | 0.454 |

| HT | 0.182 (0.030-1.094 | 0.063 |

| Dyslipidemia | 6.048 (1.065-34.348) | 0.042 |

| ProtU 0.15-0.5 g/g | 0.361 (0.083-1.560) | 0.172 |

| Pre- donation eGFR ml/min/1.73m2 | 0.951 (0.899-1.006) | 0.080 |

| Related donor | 0.745 (0.194-2.831) | 0.668 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).