1. Introduction

Chitin, the homopolymer of β-(1⟶4)-linked

N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) units, is the most abundant polysaccharide in the marine environment with annual productions estimated at ~2.8 x 10

7 t – 1.3 x 10

9 t [

1]. Yet despite this natural abundance and the rising global demand for sustainable high-performance materials, marine chitin remains still underexploited in technical applications compared to other polysaccharides [

2].

In most biological systems, chitin occurs embedded within protein-mineral nanocomposites, rather than as a pure polymer [

3,

4,

5,

6]. These hierarchical chitin composites establish an important structure-function relationship enabling diverse functions, for example structural coloration in beetles, impact resistance of mantis shrimp dactyl clubs, and fracture toughness in the mollusk shell [

2]. However, this composite structure also complicates chitin isolation procedures [

2]. Consequently, in recent years, there were enormous research efforts to develop sustainable chitin extraction strategies from various sources [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Chitin nanomaterials already support a wide range of applications, including electrorheological fillers [

11], adsorbents for toxic dyes [

12], additives to reinforce foams and emulsions [

13], as well as bioinks for 3D printing [

8].

A relatively exotic but promising source is algal chitin from species of the order

Thalassiosirales (Bacilariaphyceae). These organisms can pre-form relatively pure micro scaled β-chitin rods with high aspect ratios, typically exhibiting diameters of tens to hundreds of nm, and lengths up to ~80 µm [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Because aspect ratios of chitin nanomaterials are a key parameter of material performance, this native rod geometry is especially interesting for downstream applications [

18]. Traditionally, chitin is isolated from marine biomass which predominantly comprises crustacean shell waste, using top-down extraction strategies involving bulk demineralization (strong acids), deproteinization (strong bases), and decolorization (oxidants) steps [

6,

19]. While these pretreatments are effective in isolating relatively pure chitin nanomaterials, they can alter key polymer parameters of the isolated chitin such as the degree of polymerization (DP), degree of acetylation (DA), and pattern of acetylation (PA) [

20,

21], and thereby interfere with native structure-function relationships [

2]. Moreover, this generates substantial amounts of potentially hazardous chemical waste. After pretreatment, processing into nanochitin typically involves chemical or mechanical approaches [

19]. Chemical acidic hydrolysis mostly relies on breaking down amorphous regions producing lower aspect ratio chitin nanocrystals and nanowhiskers [

19,

22]. By contrast, mechanical processing (e.g. ultrasonication, high pressure homogenization, or grinding) relies on the application of mechanical forces to disassemble the individual fibrils of chitin composites yielding higher aspect ratio nanochitins, often termed nanofibers [

10,

18,

19].

Since

Thalassiosira spp. algae already possess the bio-machinery to synthesize chitin microrods in a relatively pure form, no pretreatment is necessary. An interesting aspect with the

Thalassiosira rotula system is that the chitin they produce can be modulated

in vivo. With specifically tailored iminosugars made from inexpensive amino acid precursors, non-genetically modified

Thalassiosira rotula algae were shown to produce chitin microrods with increased lengths compared to control conditions [

14]. This makes them potentially valuable as chitin producers due to their ability to generate modified chitin without resorting to post-extraction chemical (dys-)functionalization. The ability to use these chitin-forming diatoms in photobioreactors is especially attractive regarding the biological upscaling of chitin rods [

4].

By modifying the algal metabolism, a programmable route to sustainable production of tailored chitin nanomaterials is within reach [

14,

23,

24,

25]. A milder extraction procedure is, however, necessary to profit from these interesting nanochitins. Our aim, therefore, was to establish a purely water-based chitin microrod extraction method devoid of harsh chemical treatments decreasing molecular and structural damage in the process. In the future, we hope that this extraction procedure will help to harvest

in vivo modified algal chitin for use in downstream functional materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Thalassiosira rotula Cell Culture

Cultures from the centric marine diatom

Thalassiosira rotula were isolated from a marine sample gratefully obtained from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Sylt, Germany. Generally, the cells were cultured with enriched artificial sea water medium (ESAW) [

26,

27], which was filtrated through a 0.2 µm filter under sterile conditions using a laminar flow hood before usage. The cells were incubated at 18 °C under a light intensity of 50 μmol photons per m

2 per s following a 16h : 8h light cycle (light from 6 am to 2 pm).

2.2. Chitin Microrod Isolation

For the microrod isolation, growth of a preculture of T.rotula cells was initiated with at least 10 synchronized cells in 250 mL ESAW medium. The cells were grown until they reached a cell density of approximately 5000 cells / mL, which was achieved after ~5-7 days of culture. Afterwards, 50 mL of the pre-culture cell suspension was transferred to 950 mL fresh ESAW medium, which was then grown until a cell density of 10.000 cells / mL was reached (after ~7 days). The cell pellets were collected by centrifugation at 2000 xg, 5 min, room temperature (RT). The pellets were washed twice with washing buffer (300 mM NaCl, 40 mM EDTA, pH 8.2) to remove any minerals and other ESAW residuals. Finally, the cell pellet was transferred into 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes and resuspended in fresh washing buffer. The cell suspension was vigorously shaken at 2000 rpm, 25°C, for 24 hours (ThermoMixer® C, Eppendorf, Germany) to dislodge the microrods from the algal cells. The next day, the suspension was filtered through a 6-well TC-insert (pore size 8 µm) (Sarstedt: 83.3930.800) installed on top of a 50 mL Falcon tube via low-speed centrifugation (500 xg, 3 min, RT) to isolate the free chitin microrods from the cells. The filtrate containing the fibers was transferred into another 2 mL microcentrifuge tube, and washed five times with 2 mL double distilled (dd)H2O with centrifugation steps in between (15000 xg, 20 min, RT). Pellets with suspended rods were recovered, freeze dried and stored under vacuum at RT.

2.3. Light Microscopy

Light microscopy images were obtained in phase contrast mode using the Axiovert 200 M inverted light microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The microscope was equipped with a ×40 magnification objective lens (LD ACHROPLAN 40×/ 0.60, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) and a 98 CCD Camera (Zeiss AxioCam MRm) in combination with the Software Zen 2 blue edition (v2.0).

2.4. Electron Microscopy

Chitin microrods and T.rotula cells were observed using a Zeiss EVO 15 scanning electron microscope equipped with the Smart SEM software at 20 kV, 100 pA. The electrons were detected with a secondary electron detector.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging, chitin microrods were resuspended in 100 µL ddH2O. 10 µL of this suspension was carefully transferred onto a silicon wafer. For SEM imaging of T.rotula cells, aliquots of 10 µL native living cells suspended in ESAW medium were transferred onto a 0.8 µm hydrophilic polycarbonate filter (Sigma Aldrich: ATTP02500). The formation of salt crystals during drying, which could rupture the cells, was prevented by gently removing the medium with vacuum assisted filtration. This procedure did not require any fixation. The silicon wafers or polycarbonate filters were mounted onto aluminum SEM stubs topped with carbon Leit-tabs (12 mm diameter, Plano GmbH, Germany). The rods and the cells were airdried at RT and afterwards coated with Au/Pd in a sputter coater (Balzers MED 020, Leica, Germany) for 60 s at 30 mA.

2.5. HAADF-STEM Microscopy

For high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) 5 µL of a ddH2O suspension of isolated chitin rods were dropped on a 400-mesh copper grid coated with a carbon-formvar film (Plano GmbH, Germany). Chitin rods were negatively stained with 1% uranylacetate for 30 seconds for contrast enhancement. The TEM investigations were carried out in a ThermoFisher Spectra 300 at 300 kV. The TEM is equipped with a high brightness Schottky Field Emission Gun (X-FEG). The STEM images were recorded with a HAADF detector using a dwell time of 10 µs. The camera length was set to 115 mm and the convergence angle to 22,5 mrad.

2.6. Image Analysis of the Chitin Microrods

Image analysis was performed using ImageJ v1.54p [

28]. For the generation of histograms of width and length distributions, randomly 100 chitin rods were selected from SEM images and were measured manually using the line tracing feature of ImageJ. The histogram was generated using R statistical software (v 4.4.2) [

29] in combination with the ggplot2 (v 3.5.2) [

30], and the mclust (v 6.1.1) [

31] package for the Gaussian mixture modeling approach to analyze bimodal distributions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Native Chitin Rod Formation in Thalassiosira rotula

It has been shown that iminosugars are able to modulate chitin synthesis

in vivo increasing the lengths of chitin rods compared to control conditions [

14]. To investigate these chitin rods for developing applications, we wanted to establish a procedure that allows mild extraction for a rigorous structural and chemical analysis aiming at preserving the native structure-function relationship of these chitins. We first investigated intact

Thalassiosira rotula cells for their native rod geometries using light and electron microscopy to provide a baseline for a subsequent chitin rod extraction. This allows us to define the target rod morphology we want to preserve during the extraction procedure.

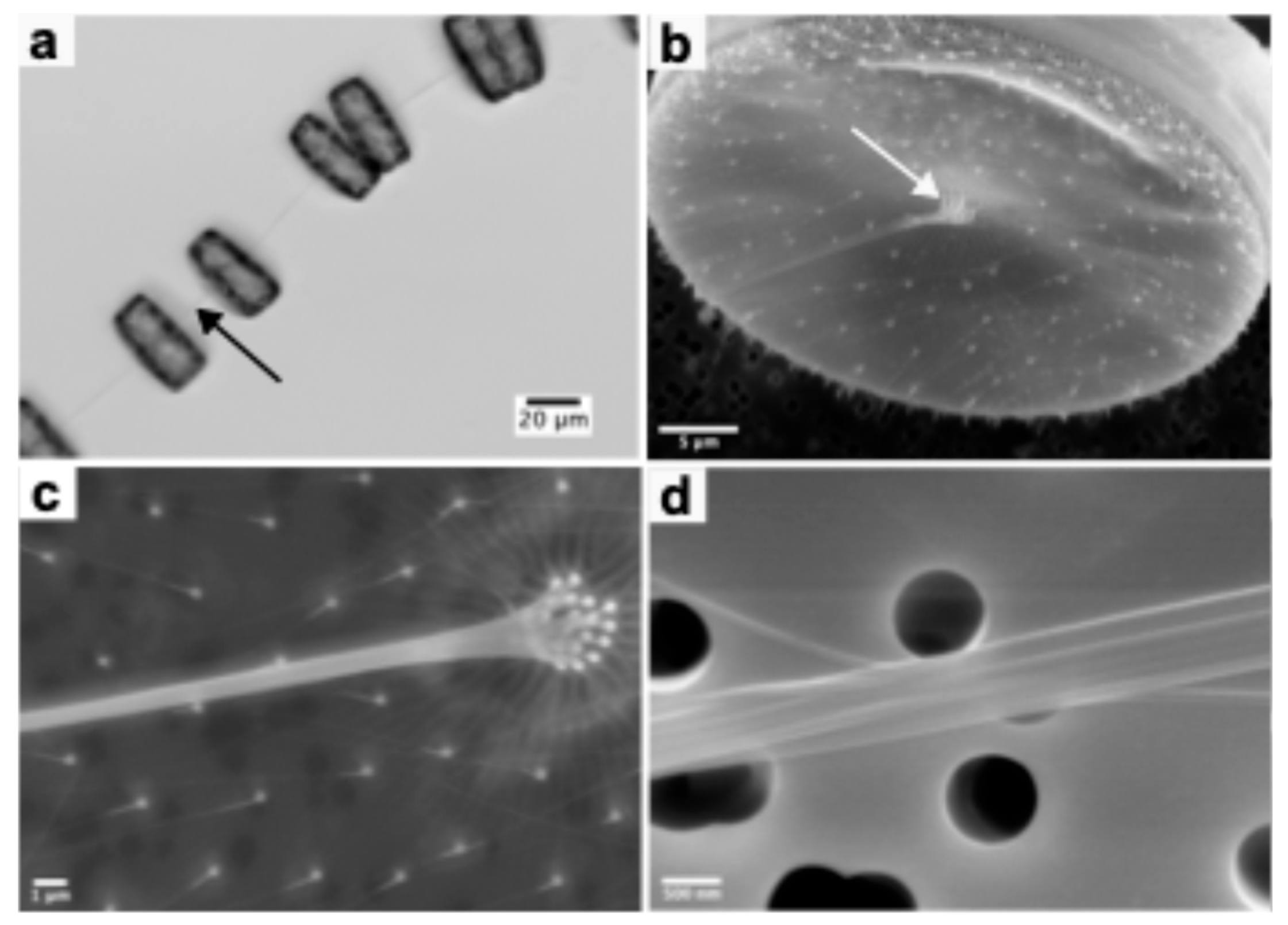

Live cell imaging using light microscopy showed that

T.rotula cells are connected together by single extracellularly formed chitin rods (

Figure 1a). Further inspection via electron microscopy (

Figure 1 b-d) demonstrated that each observed chitin rod consisted of a bundle of parallel micro- or nanorods.

Figure 1b, and 1c show the biosilica valve of

T.rotula. Distributed on its surface some protruding specialized biosilica pores (fultoportulae) are visible. Chitin synthases located in the membrane underlying the fultoportulae are responsible for forming the individual chitin rods. Notably, the rods synthesized by the central fultoportulae are connected together forming a microrod bundle. At higher magnifications (

Figure 1d) individual rod bundles appear smooth, straight and uniform in thickness. The number of fultoportulae in the center as well as the smaller ones distributed on the valve are not consistent among the cells but tend to be around 15 to 17 central fultoportulae and 101 – 117 outer fultoportulae (

Table 1). Measurement of the chitin rod diameters showed that they are different based on the position of the fultoportulae from which they originated. Chitins from central fultoportulae formed thicker chitin rods with 111 ± 33 nm on average while outer fultoportulae extrude thinner rods with an average of 69 ± 18 nm. The rod diameter is probably limited by the diameter of the silica pore itself (216 ± 44 nm for the central fultoportulae vs 165 ± 33 nm for the outer fultoportulae). Collected morphological measurements of the native synthesized rods and of

T.rotula fultoportulae are provided in

Table 1.

After having defined the native T.rotula rod geometries, a water-based rod extraction workflow was designed for mechanically removing the microrods from fultoportulae while minimizing rod damage.

3.2. T.rotula Chitin Rod Isolation

Isolation of structurally intact β-chitin microrods required cultivation of

T.rotula diatoms under controlled conditions to maximize rod production while minimizing cellular aggregation. We started cultivation with a preculture of a synchronous population of at least 10 cells to reduce variability of the timing of chitin rod extrusion which happens once per day on average [

14]. Cultures were then grown at 1 L scale in ESAW medium until they reached a density of around 10.000 cells / mL but were not cultivated for more than 7 consecutive days in the same medium. From experience, prolonging the culture beyond this point led to nutrient depletion, cells clumping and stagnated growth coinciding with increased biofilm formation [

32]. Harvesting the chitin rods in this state complicated the purification procedure at the end.

Cells were harvested by low-speed centrifugation to minimize shear and to prevent cell lysis limiting unwanted spill of cellular contents into the suspension. Afterwards, the pellet is washed twice with 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM EDTA (pH 8.2)

. The washing step served two purposes (1): removal of residual medium components (2): maintenance of osmotic balance to minimize lysis. The pH was selected to resemble natural seawater at pH 8.2 [

33] and to exploit potential self-assembly of β-chitin, as previously reported for squid pen chitin at pHs between 7.0 and 8.5 [

34]. Experimental variations in NaCl and EDTA concentrations at different pH values demonstrated that the rods and the cells remained structurally intact as determined by light microscopy until a pH of 10, whereas extreme alkaline conditions at pH 13 caused dissolution of the silica frustule interfering with the extruded chitin rod isolation.

After washing, the cell pellet (~10 mg / mL on average per batch) was subjected to overnight mechanical shaking treatment at 2000 rpm. This treatment proved to be effective in dislodging the microrods from fultoportulae requiring no further treatment. Previous reports on top-down mechanical approaches showed that high aspect ratios of chitin nanomaterials can be preserved [

18,

22]. Subsequently, we separated the rods from the cells by filtration through 8 µm filters. Given that typical

T.rotula valve diameters are around 25 µm (

Figure 1b) this cutoff retained cells on the membrane while allowing the microrods to pass through. The chitin rod-containing filtrate was then subjected to multiple washing steps using ddH

2O to remove remaining salts from the washing buffer yielding a mostly pure pellet of chitin rods suitable for imaging and analysis. We compiled state-of-the-art methodologies to extract chitin from diatoms over the years in

Table 2 to contextualize our approach.

Two distinct chitin targets in extraction procedures are apparent from the frequently applied methods in

Table 1: (1) chitin which is associated with the silica cell wall or (2), chitin microrods that are extruded from fultoportulae into the extracellular environment. Harvesting chitin embedded into the cell wall, requires the dissolution of the biosilica frustule. This is typically done by treatment of cells with harsh bases such as KOH exploiting the high pH environment [

36] or using reagents such as hydrofluoric acid or ammonium fluoride as was done in [

36,

37,

39] followed by repeated washing and drying cycles.

Isolation of extruded rods, however, typically employs mechanical approaches including the use of blending [

15,

35,

38] or centrifugation [

16,

36,

39]. Since we were interested exclusively in the chitin rods extruded from the cells and not present in cell walls, our initial starting point was based on a mechanical procedure. However, while approaches such as short bursts of blending or centrifugation work well for algal species that form single chitin rods (

Thalassiosira fluviatilis Hustedt [

35],

Thalassiosira weissflogii [

36,

38,

39], or

Cyclotella cryptica [

15,

16]),

T.rotula also produces bundled chitin microrods (

Figure 1 b-d) that proved to be resistant using these approaches. Longer blending times led to cell rupture, which made it more difficult to isolate chitin in the further steps and centrifugation in general did not result in effective chitin rod extraction at all in

T.rotula. Thus, we decided to use controlled shaking over night to efficiently dislodge the chitin rods without rupturing the cells in the process.

In the development of the chitin pellet purification steps, we wanted to preserve the structure-function relationship of the native chitin. Therefore, our processes were all carried out at room temperature and we abstained from harsh chemicals such as strong acids, bases or bleaches. For example in [

16] the extruded cell pellet was dried at 200°C. In contrast to our method this drying process might damage the native structure. Treatments of chitin pellets with KOH or NaOH as in [

36,

38,

39], HCl as in [

15,

36,

39], and treatments with oxidants for decolorization as in [

36,

38,

39] could be avoided.

3.3. Electron Microscopical Analysis of the Isolated Chitin Rods

We quantified rod geometries after the water-based extraction procedures to assess whether they retained the native architecture observed on live cells (

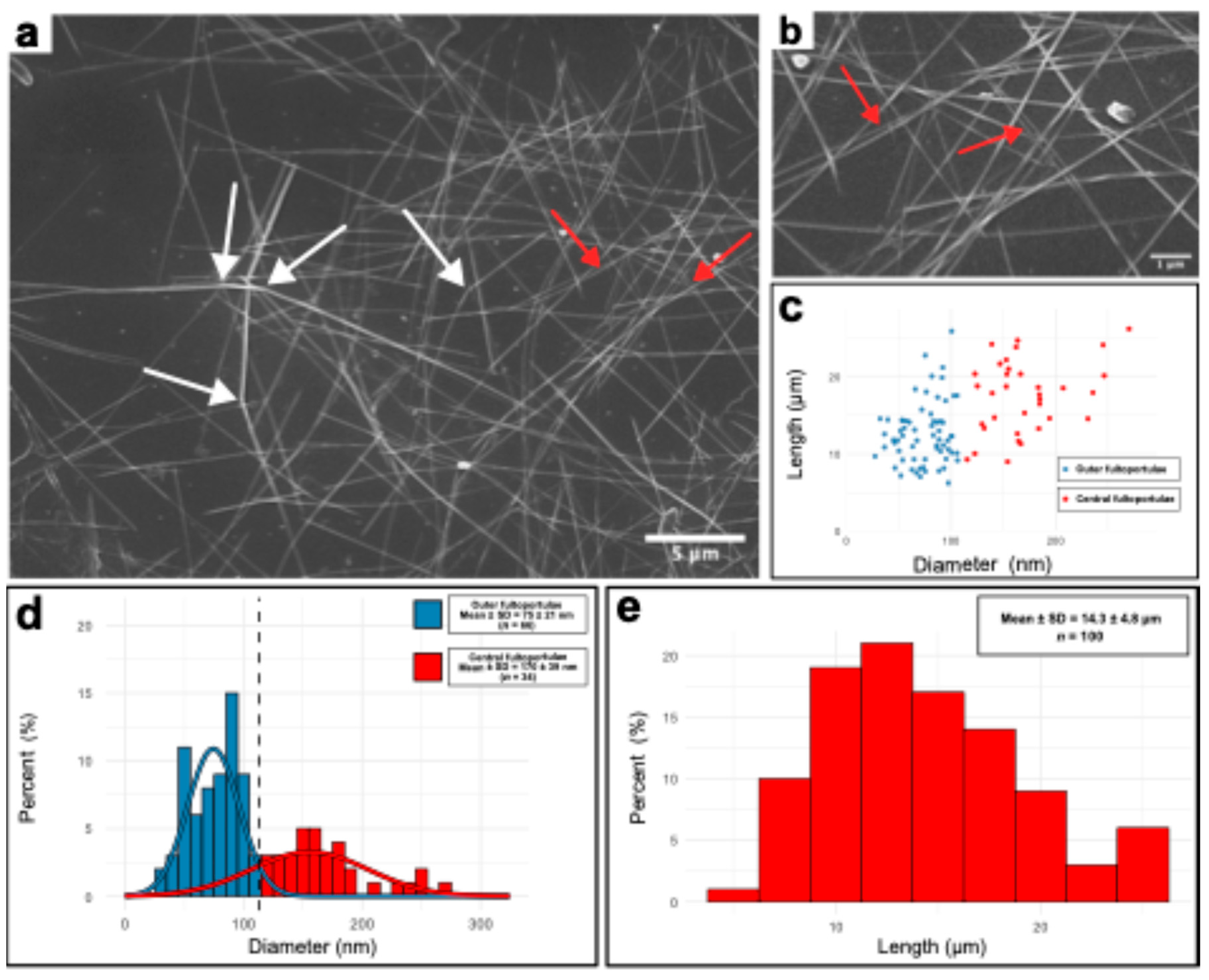

Table 1). Rod lengths and diameters were measured from scanning electron microscopy images.

Figure 2a shows an exemplary SEM image of airdried chitin microrods deposited on a silicon wafer. Longer rods displayed a degree of bending (

Figure 1a, white arrows) and an occasional partial unwinding into smaller rods hinting at an underlying fibrillar structure as it is common among chitin materials was observed (

Figure 2a, b, red arrows) [

2]. We measured the diameters and lengths of

n = 100 randomly selected microrods across multiple SEM images. A scatterplot of the measurements is provided in

Figure 2c while the corresponding distributions of diameter and length are shown as histograms in

Figure 2d and 2e, respectively. Because we observed a bimodal diameter distribution, we performed Gaussian mixture modeling using the mclust package in the R environment to separate the two populations of rod diameters and to evaluate them. We determined mean diameters of 75 ± 21 nm (

n = 66) for population 1 and 170 ± 39 nm (

n = 34) for population 2 with a cutoff determined to be 107 nm. The two populations are indicated accordingly in the scatterplot as well. Rod lengths do not show a significant bimodal pattern and are distributed broadly around 5 - 30 µm with an average of 14.3 ± 4.8 µm. These rod geometries yield high aspect ratios (

L/d) of ~191 for population 1 and ~84 for population 2. When compared with native microrod measurements from

Table 1, the two distinct diameter populations map onto the rods extruded from the different types of fultoportulae. From outer fultoportulae generally thinner rods are extruded (69 ± 18 nm), whereas central fultoportulae were measured to extrude rods with average diameters of 111 ± 33 nm. These ones being lower compared to extracted rods probably due to biological variations over time of the experiments. However, a succinct trend is observable between thinner and thicker rod geometries and we therefore determined these two different populations to be the rods extracted from outer and central fultoportulae. A predominant extraction of rods with lower diameter is expected, since the outer fultoportulae outnumber the central ones by a factor of 6.8. Furthermore, the broader length distribution (5 - 30 µm) is not surprising since at the time of harvesting, rod synthesis is not synchronized anymore. We tried to combat this effect by initiating the culture with synchronous cells. However, maintaining perfect synchrony remained difficult to achieve after several days of culture.

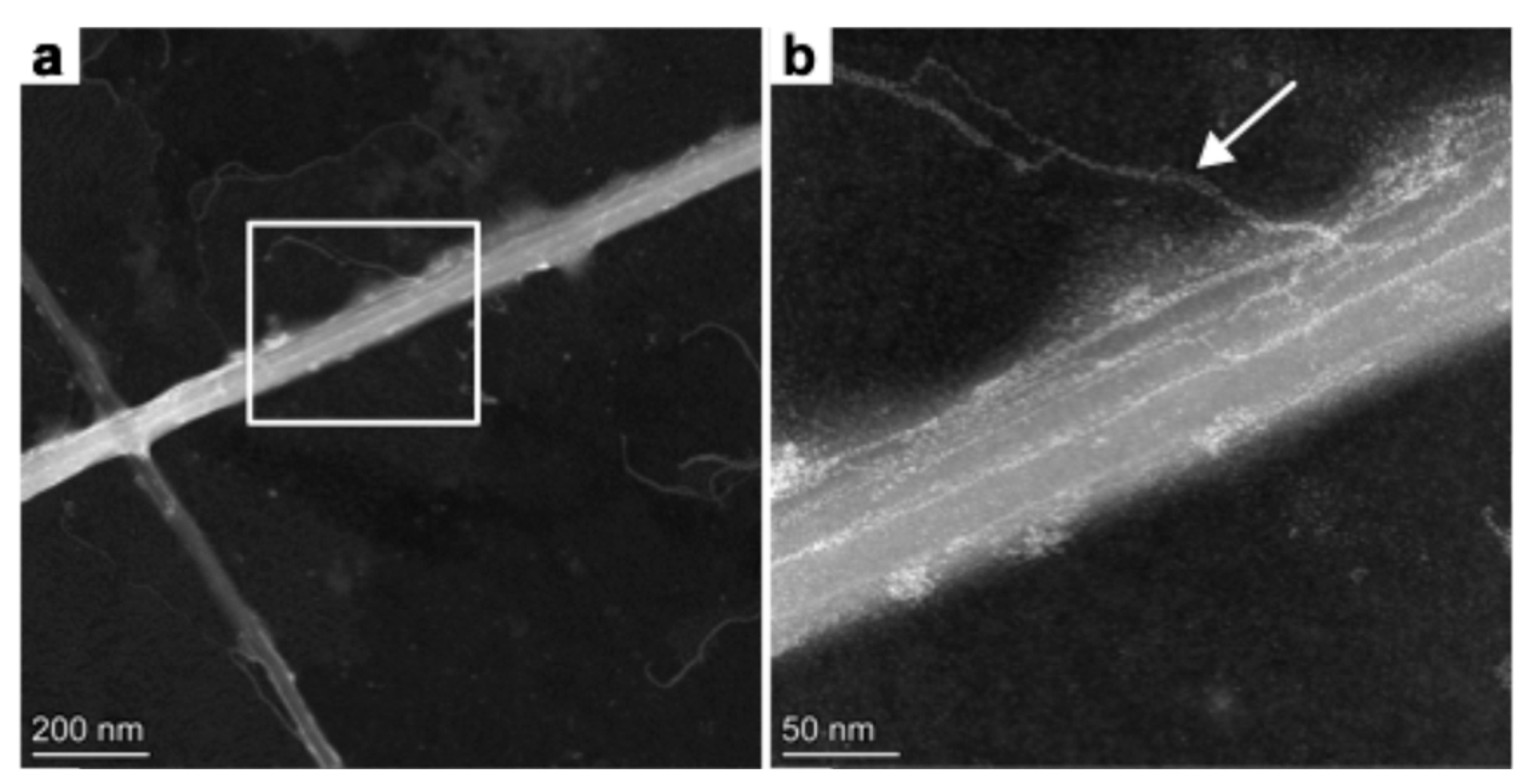

We performed high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF – STEM) on uranylacetate-stained chitin rods to examine the ultrastructure of the microrods in more detail. This technique allows the observation and confirmation of the ultrastructural integrity of the chitin rods isolated with the water-based extraction method. In

Figure 3a two chitin microrods are shown with ~75 nm and ~50 nm in diameter. This corresponds to chitin rods extruded from outer fultoportulae (

Figure 2). In contrast to SEM (

Figure 2), an internal texture is visible in the HAADF-STEM image (Figure 3). We interpret this as an additional hierarchical level. It is interesting to note that even chitin rods originating from smaller fultoportulae populations consist of several fibrils.

The rods seem to consist themselves of several nanorods which measured between 16 - 20 nm on average. Higher magnification imaging (

Figure 3b) revealed some secondary nanofibrillar structures protruding from one of the main rods (white arrow). These nanofibrils are thin with approximately 4.2 - 4.5 nm in diameter and seem to be more flexible than the main rod and possibly wind around the main fibril.

3.4. Comparison with Nanochitins from Other Sources

To our knowledge this is the first report of extruded chitin microrods from

T.rotula under water-based extraction conditions. Most nanochitin studies focus on biomass typically consisting of crustacean shell waste [

3,

6] or squid pen β-chitin sources, where substantial pretreatment is necessary to remove minerals, proteins, and pigments [

6]. Such pretreatments may alter the DP, DA, and PA, and therefore disrupt the native structure of chitin [

2,

21]. In contrast, our mechanical water-based workflow retains the native high aspect ratio rod geometry and molecular composition by elimination of harsh chemical treatments.

In

Table 3, we summarized representative mechanical nanochitin preparations across α-, and β-chitin sources together with the dimensions of the resulting nanochitins. Notably, due to an overwhelming amount of extraction procedures and an equally enormous amount of possible chitin sources the research on nanochitins is relatively unfocused and thus difficult to compare. Especially considering that we use a rather exotic source for β-chitin nanomaterials. However, as a general trend it can be stated that α-chitin sources lead to lower aspect ratio (

L/d) nanochitins (mostly < 100) compared to β-chitin sources which have higher aspect ratios. The chitin microrods we isolated from

T.rotula exhibited aspect ratios of ~191 for rods extruded from outer fultoportulae and ~84 for rods extruded from central fultoportulae. Both populations of rods show high aspect ratios comparable with other sources of chitin nanomaterials. Rods from outer fultoportulae show similar if not higher aspect ratios than chitin rods isolated from squid pen [

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, considering only diameters, squid pen nanochitins are typically thinner. This is compensated by the length of

T.rotula rods with 14.3 µm on average (this study) dominating the length scale among all the materials considered in

Table 3.

Interestingly though, chitin rods from

T.rotula generally are quite short when compared with microrods isolated from other species of

Thalassiosirales (

Table 2) which often lie in the range of 50 - 80 µm. From a previous study we observed chitin rods synthesized

in vivo between 19 - 23 µm for

T.rotula [

14]. These deviations probably reflect the biological variations among different cell populations over time.

Our ultrastructure investigations using HAADF-STEM (

Figure 3) shows for the first time the internal fibrillar structure of

T.rotula chitin nanorods. The occasionally protruding chitin nanofibrils which were measured to 4.2 - 4.5 nm in diameter are consistent with diameters of β-chitin microrods from squid pen in

Table 3 supporting the view that

T.rotula microrods are composed of hierarchically ordered β-chitin fibrils.

These comparisons especially underline two advantages in the use of

T.rotula as a source for chitin rods for high aspect ratio materials. First, pre-formed chitin microrods simplify the isolation procedure, since pretreatment steps can be avoided. Second, from other studies it was shown that

T.rotula chitin rods can be modulated

in vivo [

14,

24,

25]. Given that rod geometry is important for material performance in applications such as mechanical reinforcements, foam stabilization, and electrorheology, the coupling of biological tuning with a mild extraction procedure that preserves the structure-function relationship provides a promising route to programmable sustainable chitin building blocks. We note that upscaling of species of other

Thalassiosirales microalgae was shown to be possible in photobioreactors [

4] suggesting that a scale-up of

T.rotula cultures is feasible after some optimization.

5. Conclusions

In this study we successfully developed a water-based extraction procedure of β-chitin microrods from T.rotula cells. The method avoids harsh chemical treatments preventing the release of potential hazardous chemicals into the environment while minimizing damage to preserve the native hierarchical chitin structure of the microrods. SEM imaging confirmed the structural integrity and the high aspect ratios of the microrods (~191 and 84 for rods synthesized by outer and central fultoportulae, respectively).

Our HAADF-STEM analysis revealed for the first time the underlying hierarchical fibrillar composite structure of algal β-chitin rods and showed occasionally protruding nanofibrils not visible using SEM investigations. This sustainable procedure provides the foundation for analyzing and understanding rod morphologies from microrods synthesized under chitin-modulating conditions. We hope that in the future chitin nano- and microrods extracted using this procedure will be applied for a wide range of applications, e.g. as potential fillers for electrorheological suspensions, lightweight reinforcement material for biocomposites, biomedical scaffolds, or food packaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., S.L. and I.M.W.; methodology, J.L., and I.M.W.; validation, J.L.; formal analysis, J.L. F.K.; investigation, J.L.; resources, I.M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., F.K., S.L. and I.M.W..; visualization, J.L.; supervision, I.M.W.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, I.M.W, and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Carl Zeiss Foundation for the infrastructure project ChitinFluid (project no. P2019-02004) and received financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG, AOBJ: 661806). Furthermore, this research was supported by the European Regional Development Fund (EFRE, FEIH_778511) and the German Research Foundation DFG: INST 41/1034-1 FUGG (AOBJ: 642944).

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the core facility SRF AMICA (Stuttgart Research Focus Advanced Materials Innovation and Characterization) at the University of Stuttgart for their support & assistance in this work. This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, AOBJ: 661806). We thank M. Claußen from the AWI who generously provided us with the Thalassiosira rotula cells. Further, the authors acknowledge the generous financial support by the Carl Zeiss Foundation for the infrastructure project ChitinFluid (project no. P2019-02004). We thank M. Schweikert for his expert advice on microscopy techniques and algal cultures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AWI |

Alfred-Wegener-Institut |

| DP |

Degree of polymerization |

| DA |

Degree of acetylation |

| ddH2O |

Double distilled water |

| ESAW |

Enriched artificial sea water |

| GlcNAc |

N-acetyl glucosamine |

| HAADF-STEM |

High-angle annular dark-field – Scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| PA |

Patterns of acetylation |

| RT |

Room Temperature |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Dhillon, G.S.; Kaur, S.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M. Green Synthesis Approach: Extraction of Chitosan from Fungus Mycelia. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2013, 33, 379–403. [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Aydemir, B.E.; Dumanli, A.G. Understanding the Structural Diversity of Chitins as a Versatile Biomaterial. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2021, 379, 20200331. [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Chen, X. Sustainability: Don’t Waste Seafood Waste. Nature 2015, 524, 155–157. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A. Screening Diatom Strains Belonging to Cyclotella Genus for Chitin Nanofiber Production under Photobioreactor Conditions: Chitin Productivity and Characterization of Physicochemical Properties. Algal Research 2023, 70, 103015. [CrossRef]

- Aldila, H.; Asmar; Fabiani, V.A.; Dalimunthe, D.Y.; Irwanto, R. The Effect of Deproteinization Temperature and NaOH Concentration on Deacetylation Step in Optimizing Extraction of Chitosan from Shrimp Shells Waste. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 599, 012003. [CrossRef]

- Kozma, M.; Acharya, B.; Bissessur, R. Chitin, Chitosan, and Nanochitin: Extraction, Synthesis, and Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3989. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Ganesan, A.R.; Ezhilarasi, P.N.; Kondamareddy, K.K.; Rajan, D.K.; Sathishkumar, P.; Rajarajeswaran, J.; Conterno, L. Green and Eco-Friendly Approaches for the Extraction of Chitin and Chitosan: A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 287, 119349. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, M.-C.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, C.; Mei, C. Microwave-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction of Chitin from Crayfish Shell Wastes for 3D Printable Inks. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 194, 116325. [CrossRef]

- Saravana, P.S.; Ho, T.C.; Chae, S.-J.; Cho, Y.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Chun, B.-S. Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Extraction and Fabrication of Chitin Films from Crustacean Waste. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 195, 622–630. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Shi, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, C.; Deng, H. Chitin/Chitosan Nanofibers Toward a Sustainable Future: From Hierarchical Structural Regulation to Functionalization Applications. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 12014–12026. [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, V.V.; Kuznetsov, N.M.; Istomina, A.P.; Bogdanova, O.I.; Vdovichenko, A.Yu.; Streltsov, D.R.; Malakhov, S.N.; Kamyshinsky, R.A.; Chvalun, S.N. Low-Filled Suspensions of α-Chitin Nanorods for Electrorheological Applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 277, 118792. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Ji, C.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Hairy Chitin Nanocrystals: Sustainable Adsorbents for Efficient Removal of Organic Dyes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 298, 139948. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Biopolymer-Based Particles as Stabilizing Agents for Emulsions and Foams. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 68, 219–231. [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, M.; Ludwig, J.; Bernz, A.; Claasen, B.; Majoul, A.; Reuter, J.; Zens, A.; Pawletta, B.; Bilitewski, U.; Weiss, I.M.; et al. Modulating Chitin Synthesis in Marine Algae with Iminosugars Obtained by SmI2 and FeCl3-Mediated Diastereoselective Carbonyl Ene Reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 6606–6618. [CrossRef]

- LeDuff, P.; Rorrer, G.L. Formation of Extracellular β-Chitin Nanofibers during Batch Cultivation of Marine Diatom Cyclotella Sp. at Silicon Limitation. Journal of Applied Phycology 2019, 31, 3479–3490. [CrossRef]

- Herth, W.; Zugenmaier, P. Ultrastructure of the Chitin Fibrils of the Centric Diatom Cyclotella Cryptica. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 1977, 61, 230–239. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Noishiki, Y.; Wada, M. X-Ray Structure of Anhydrous β-Chitin at 1 Å Resolution. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 950–957. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hao, L.T.; Park, J.; Oh, D.X.; Hwang, D.S. Nanochitin and Nanochitosan: Chitin Nanostructure Engineering with Multiscale Properties for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2203325. [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, L.; Esquivel, M.; Tardy, B.L.; Huan, S.; Niu, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; Fan, Y.; Rojas, O.J. Nanochitin: Chemistry, Structure, Assembly, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 11604–11674. [CrossRef]

- Pakizeh, M.; Moradi, A.; Ghassemi, T. Chemical Extraction and Modification of Chitin and Chitosan from Shrimp Shells. European Polymer Journal 2021, 159, 110709. [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Wattjes, J.; Niehues, A.; Mengoni, T.; Mendes, A.C.; Morris, E.R.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Moerschbacher, B.M. Biotechnologically Produced Chitosans with Nonrandom Acetylation Patterns Differ from Conventional Chitosans in Properties and Activities. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7125. [CrossRef]

- Panackal Shibu, R.; Jafari, M.; Sagala, S.L.; Shamshina, J.L. Chitin Nanowhiskers: A Review of Manufacturing, Processing, and the Influence of Content on Composite Reinforcement and Property Enhancement. RSC Appl. Polym. 2025, 10.1039.D5LP00104H. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Bowler, C.; Xing, X.; Bulone, V.; Shao, Z.; Duan, D. Full-Length Transcriptome of Thalassiosira Weissflogii as a Reference Resource and Mining of Chitin-Related Genes. Mar Drugs 2021, 19, 392. [CrossRef]

- Di Dato, V.; Di Costanzo, F.; Barbarinaldi, R.; Perna, A.; Ianora, A.; Romano, G. Unveiling the Presence of Biosynthetic Pathways for Bioactive Compounds in the Thalassiosira Rotula Transcriptome. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9893. [CrossRef]

- Sumper, M.; Weiss, I.M.; Eichner, N. Chitin Synthase 1 [Thalassiosira Rotula] Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/ACL00587.1.

- Harrison, P.J.; Waters, R.E.; Taylor, F.J.R. A Broad Spectrum Artificial Sea Water Medium for Coastal and Open Ocean Phytoplankton1. Journal of Phycology 1980, 16, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Berges, J.A.; Franklin, D.J.; Harrison, P.J. Evolution of an Artificial Seawater Medium: Improvements in Enriched Seawater, Artificial Water Over the Last Two Decades. Journal of Phycology 2001, 37, 1138–1145. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2021.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag New York, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4.

- Scrucca, L.; Fraley, C.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation Using mclust in R; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023; ISBN 978-1-032-23495-3.

- Khan, M.J.; Singh, R.; Shewani, K.; Shukla, P.; Bhaskar, P.V.; Joshi, K.B.; Vinayak, V. Exopolysaccharides Directed Embellishment of Diatoms Triggered on Plastics and Other Marine Litter. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18448. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.-Q.; Carter, B.R.; Feely, R.A.; Lauvset, S.K.; Olsen, A. Surface Ocean pH and Buffer Capacity: Past, Present and Future. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18624. [CrossRef]

- Montroni, D.; Marzec, B.; Valle, F.; Nudelman, F.; Falini, G. β-Chitin Nanofibril Self-Assembly in Aqueous Environments. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2421–2429. [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, J.; McInnes, A.G.; Falk, M. Studies on the Chitan (Chitin: Poly-n-Acetylglucosamine) Fibers of the Diatom Thalassiosira Fluviatilis Hustedt: I Production and Isolation of Chitan Fibers. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 707–713. [CrossRef]

- Noishiki, Y.; Y, N.; M, W.; S, O.; S, K. Inclusion Complex of Beta-Chitin and Aliphatic Amines. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4. [CrossRef]

- Brunner, E.; Richthammer, P.; Ehrlich, H.; Paasch, S.; Simon, P.; Ueberlein, S.; van Pée, K.-H. Chitin-Based Organic Networks: An Integral Part of Cell Wall Biosilica in the Diatom Thalassiosira Pseudonana. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009, 48, 9724–9727. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Kimura, S.; Wada, M. Electron Diffraction and High-Resolution Imaging on Highly-Crystalline β-Chitin Microfibril. Journal of Structural Biology 2011, 176, 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Shao, Z.; Wang, X.; Lu, C.; Li, S.; Duan, D. Novel Chitin Deacetylase from Thalassiosira Weissflogii Highlights the Potential for Chitin Derivative Production. Metabolites 2023, 13, 429. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jungstedt, E.; Šoltésová, M.; Mushi, N.E.; Berglund, L.A. High Strength Nanostructured Films Based on Well-Preserved β-Chitin Nanofibrils. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11001–11011. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Preparation of Chitin Nanofibers from Squid Pen β-Chitin by Simple Mechanical Treatment under Acid Conditions. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1919–1923. [CrossRef]

- Bamba, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Saito, T.; Berglund, L.A.; Isogai, A. Estimating the Strength of Single Chitin Nanofibrils via Sonication-Induced Fragmentation. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4405–4410. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Wang, S.-T.; Chang, K.-L.B.; Tsai, M.-L. Enhancing Saltiness Perception Using Chitin Nanomaterials. Polymers 2019, 11, 719. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Individual Chitin Nano-Whiskers Prepared from Partially Deacetylated α-Chitin by Fibril Surface Cationization. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 79, 1046–1051. [CrossRef]

- Mushi, N.E.; Butchosa, N.; Salajkova, M.; Zhou, Q.; Berglund, L.A. Nanostructured Membranes Based on Native Chitin Nanofibers Prepared by Mild Process. Carbohydrate Polymers 2014, 112, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Salaberria, A.M.; Fernandes, S.C.M.; Diaz, R.H.; Labidi, J. Processing of α-Chitin Nanofibers by Dynamic High Pressure Homogenization: Characterization and Antifungal Activity against A. Niger. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 116, 286–291. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-C.; Wu, Q.; Song, K.; Cheng, H.N.; Suzuki, S.; Lei, T. Chitin Nanofibers as Reinforcing and Antimicrobial Agents in Carboxymethyl Cellulose Films: Influence of Partial Deacetylation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4385–4395. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).