1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex neuropsychiatric disease, with multifactorial etiology including both genetic and environmental aspects [

1,

2,

3]. Available data support the diathesis stress model as the primary causal theory, and genetic liability is strongly implicated [

4,

5]. New studies have investigated autoimmune and infectious mediators in some cases of schizophrenia [

6]. Moreover, theories of neurodevelopmental and neurodegeneration [

1], as well as lowered protein synthesis, have also been proposed [

7]. Prenatal/perinatal adverse events, behavioral/neurocognitive signs during childhood, and schizotypal personality traits are correlated with an enhanced risk to develop schizophrenia [

8]. Traditional diagnostic and treatment frameworks, largely reliant on clinical observation and trial-and-error pharmacotherapy, have proven insufficient for addressing the substantial interindividual variability in disease progression and treatment response [

9,

10].

Molecular psychiatry has made considerable progress over the past decades and is gradually increasing knowledge on the biological complexity of schizophrenia, allowing for the characterization of its genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic landscapes. Genomic [

11], epigenomic [

12] and transcriptomic [

13] analyses have also facilitated our understanding of disease risk profiles and molecular pathways [

14,

15]. Most risk is predicted by hundreds of common variants, and rare variants and copy number variants (CNVs) increased risk in a proportion of cases [

11,

16]. Concurrently, overlapping transcriptomic and epigenomic changes in particular in synaptic plasticity, neuronal development and immune signaling pathways - have also been observed in patient brain tissue and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neuronal models [

17,

18,

19]. CNVs and new mutations are also involved in increased susceptibility to schizophrenia, especially among subpopulations. These include the well-characterized 22q11. 2 deletions and 16p11. 2 duplications and are also related to autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability [

20,

21]. In schizophrenia research, proteomics remains less developed compared to other fields, with the identification of differential proteins and potential biomarkers emerging only in recent years [

22,

23]. Integrating proteomic data with findings from other studied fields may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the disorder’s biological complexity [

24,

25].

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models are emerging as a powerful tool for investigating the neurodevelopmental and molecular foundations of schizophrenia. A recent meta-analysis by Burrack et al. [

26] identified consistent dysregulation of phosphodiesterase 4 (

PDE4) gene expression in both brain and blood samples from individuals with schizophrenia. These findings were validated in iPSC-derived dentate gyrus-like neurons. This suggests a conserved molecular pathology across tissue types. In parallel, Stern et al. [

27] demonstrated that monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia exhibit marked differences in neuronal maturation and synaptic transmission when modeled in iPSC-derived neurons. These findings support the role of early neurodevelopmental processes in disease emergence. Advancements in regional specificity have further enhanced the utility of iPSC models. For example, Sarkar et al. [

28] developed a protocol for generating CA3 hippocampal neurons which enables in vitro modeling of hippocampal circuitry relevant to schizophrenia pathophysiology. This builds upon initial work by Brennand et al. [

29], who first reported impaired connectivity and aberrant expression of genes involved in synaptic function and Wnt signaling in patient-derived iPSC neurons. Importantly, subsequent studies confirmed the translational validity of these models. Hoffman et al. [

17] demonstrated that gene expression profiles in schizophrenia iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons recapitulate transcriptional signatures observed in postmortem adult brain tissue. Beyond modeling schizophrenia in isolation, recent comparative studies have begun to uncover shared mechanisms with other related disorders. Romanovsky et al. [

30] revealed significant genetic overlap between schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In this study they showed that, although iPSC-derived neurons from these disorders follow distinct early developmental trajectories, they ultimately converge on similar synaptic impairments as they mature. Together, these findings highlight the value of iPSC models in capturing dynamic disease-relevant phenotypes.

The application of systems biology and machine learning has enabled integrative analysis, yielding testable hypotheses about disease mechanisms and candidate biomarkers for diagnosis and stratification [

24,

31]. These advances form the basis of a nascent but promising precision psychiatry paradigm; wherein molecular signatures could guide individualized treatment approaches. Notably, lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) have demonstrated utility as predictive platforms in this domain. For instance, expression patterns of immunoglobulin genes in LCLs were shown to distinguish lithium responders from non-responders among individuals with bipolar disorder [

32], while transcriptomic profiling of LCLs has been employed to predict suicide risk with promising accuracy [

33]. More broadly, predictive models of drug response across a spectrum of psychiatric conditions have been proposed, highlighting the value of combining patient-derived cellular systems with genomic and transcriptomic data to refine treatment stratification strategies [

34].

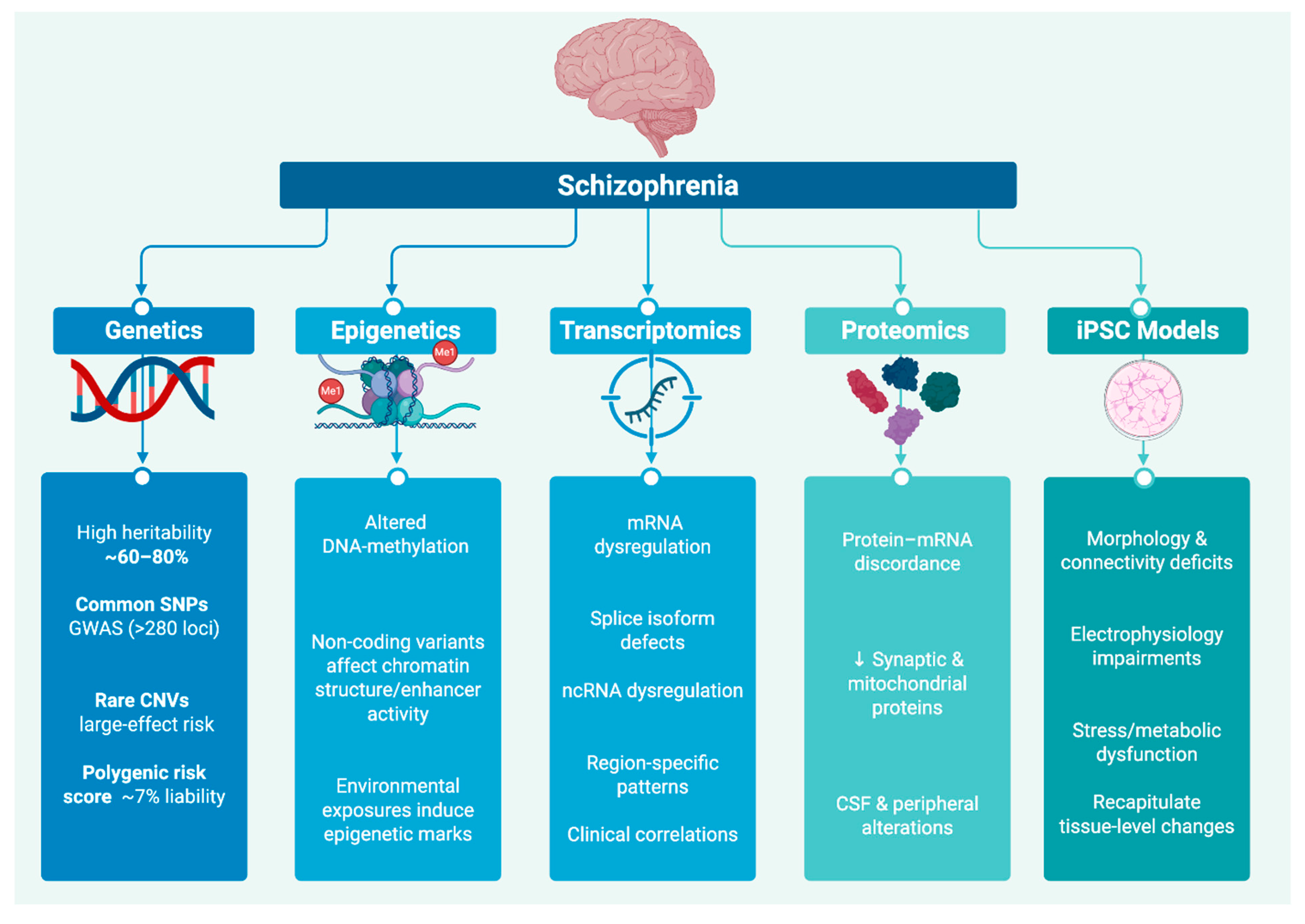

In this review, we examine schizophrenia’s molecular landscape across genetic and epigenetic variation, transcriptomic and proteomic alterations and eventually in iPSC models. An overview of representative molecular alterations across these five domains is presented in

Figure 1, which schematically summarizes key findings from genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and iPSC model studies in schizophrenia. We demonstrate that, despite their apparent divergence, these signatures may coalesce around a defined set of core biological pathways. The recurrent involvement of synaptic, immune, mitochondrial, neurodevelopmental, and adhesion-related mechanisms across diverse molecular studies highlights potential axes of convergence in schizophrenia. These patterns merit systematic validation through integrative and large-scale investigations.

2. Genetic Risk Architecture of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a strongly heritable neuropsychiatric disorder and is also polygenic [

3]. Its heritability estimates derived from classical twin and family based studies are in the range of 60%-80% [

35]. Large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have enriched our knowledge regarding the genetic architecture of this complex disorder with the identification of >250 genome-wide significant loci. These loci are mapped to genes and regulatory elements implicated in pathways related to neurodevelopment, synaptic signaling, immune response, and calcium channel regulation. All of which are mechanisms implicated in schizophrenia pathophysiology [

11,

36,

37]. Among these, variation within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6 has received particular attention due to the functional characterization of the complement component 4A (C4A) gene. Structural variation at this locus affects C4A expression, which has been shown to correlate with schizophrenia risk and may contribute to altered synaptic pruning during adolescence [

38].

2.1. Common Variation (SNPs and PRS)

Despite schizophrenia’s high estimated heritability (~80%) from family and twin studies, isolating the specific genetic variants responsible for this risk only became possible with the large-scale GWAS. Since the first schizophrenia GWAS in 2008 [

39] identified a common RELN variant increasing risk specifically in women, large-scale efforts have since expanded to identify over 100 genome-wide significant loci. Subsequent meta-analyses have increased this number to nearly 300 loci, many of which cluster in genes related to synaptic signaling, calcium-channel activity, and immune modulation. For example, a landmark 2014 GWAS by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Schizophrenia Working Group, which included 36,989 cases and 113,075 controls, reported 108 significant loci including genes such as

CACNA1C,

MIR137, and

GRIN2A [

11]. These findings were later extended in a meta-analysis involving over 320,000 individuals, identifying 287 loci enriched for pathways involved in synaptic signaling, calcium signaling, and immune regulation. [

16] Most of the associated SNPs are common variants with small individual effects on disease risk. However, their cumulative contribution is substantial, explaining approximately 23% of the SNP-based heritability of schizophrenia [

11].

A polygenic risk score (PRS) is computed by summing an individual’s risk-allele counts across thousands of common SNPs, each weighted by its GWAS-derived effect size, to yield a single metric of inherited liability to the trait [

40]. In predominantly European-ancestry cohorts, the schizophrenia PRS account for ~7.7% of case–control variance corrected for 1% disease prevalence [

11], much less than twin-based estimates of heritability (60–80%) [

3,

41]. People in the top decile of PRS have a 3 to 4 fold odds of schizophrenia relative to population expectation. PRS have an AUC of nearly 0.65 in discrimination analyses [

41]. That said, prediction accuracy is dramatically reduced in non-European population, due to differences in allele frequency and linkage disequilibrium [

42]. Novel multi-ancestry methods like PRS-CSx offer hope to enhance cross-population portability [

43].

2.2. Rare Variation

Rare structural and coding variants beyond common risk variants contribute meaningfully to schizophrenia risk.

2.2.1. Copy Number Variants (CNVs)

Recent large-scale genomic investigations have underscored the contribution of CNVs to schizophrenia risk. In a genome-wide analysis of over 21,000 schizophrenia cases and 20,000 controls, Marshall et al. [

44] identified several recurrent CNVs significantly associated with disease susceptibility. The 22q11.2 deletion which is observed in approximately 0.3% of schizophrenia cases (OR ~20–30×) encompasses key genes including

TBX1 which is implicated in neural crest development,

DGCR8 that is involved in microRNA biogenesis, and

COMT critical for dopamine metabolism. This suggests that haploinsufficiency across this region may disrupt neurodevelopmental and neurotransmitter pathways. Similarly, the 16p11.2 duplication, present in approximately 0.3% of cases (OR ~9–10), affects genes such as

MAPK3 and

TAOK2 which are components of the Ras/MAPK signaling cascade. In addition, it affects

KCTD13 a regulator of RhoA signaling, with potential consequences for neuronal proliferation, synaptic plasticity, and cytoskeletal organization. These findings are consistent with prior reviews suggesting that rare, high-penetrance CNVs contribute to approximately 2–5% of the genetic liability for schizophrenia, primarily through perturbations of neurodevelopmental, synaptic, and circuit assembly pathways [

20,

21].

2.2.2. Loss-of-Function Coding Mutation

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of germline DNA from peripheral-blood leukocytes of around 6,000 schizophrenia cases and 6,000 genetically matched controls, revealed ultra-rare heterozygous protein truncating variants (PTVs) in genes encoding chromatin modifiers, transcription factors, and synaptic proteins [

45]. Single-allele loss of function (LoF) mutations in

SETD1A and

RBM12, each with a prevalence less than 0.1%, demonstrate high penetrance (OR> 10×). This implicates mechanisms involving chromatin remodeling, histone modification and gene-regulatory networks in schizophrenia pathogenesis [

13,

46].

A follow-up meta-analysis by the SCHEMA consortium confirmed these findings in 24,248 cases versus 97,322 controls. Among the identified genes were

GRIN2A,

TRIO,

CACNA1G and

SETD1A which are enriched for ultra-rare LoF variants conferring high risk. These genes are highly expressed in cortical neurons and are enriched in the following pathways: synapse assembly, glutamatergic signaling, and ion channel regulation [

47]. Notably,

SETD1A was identified in both studies, suggesting a consistent signal across independent cohorts and reinforcing its potential contribution to schizophrenia risk.

2.3. Gene Regulation and Functional Genomics

Functional genomic analyses have been key in understanding the molecular consequences of genetic risk. Fromer et al. [

13] reported a RNA-seq and Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping analysis of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) from 467 postmortem donors (n=258 schizophrenia, 209 controls). They found that many schizophrenia risk variants are associated with gene expression levels in a range of brain areas which have been implicated in executive function and cognition, especially the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).

Similarly, Jaffe et al. [

12] merged DNA-methylation and transcription data for data in DLPFC from 526 subjects, verifying that risk loci are enriched in non-coding enhancers active in neurons and glia cells. These regulatory changes largely localize to active enhancer marks (H3K27ac) in neuronal chromatin, emphasizing the impact of the levels of epigenetic and chromatin control. Furthermore, Pardiñas et al. [

46] demonstrated that genes prioritized by GWAS and eQTL analyses are highly enriched for association with genes under strong evolutionary constraint, as defined by loss-of-function intolerance probability (pLI ≥0.9) in the ExAC reference of 60,706 exomes. This highlights the selective vulnerability of essential neurobiological processes to alteration.

Furthermore, Pardiñas et al. [

46] demonstrated that genes prioritized by GWAS and eQTL analyses are highly enriched for association with genes under strong evolutionary constraint, highlighting the selective vulnerability of essential neurobiological processes to alteration.

2.4. Systems Biology and Pathway Convergence

Convergent signals across a range of genomic domains have emerged through integrative multi-omic analysis. Pathways and network analyses constantly identify synaptic plasticity, glutamatergic signaling, immune modulation, especially complement C4A signaling, and calcium channel activity as a part of the picture of the mechanism underlying pathological processes of schizophrenia [

11,

16,

38]. Variants in the MHC, including those controlling C4A level, are particularly interesting because of a hypothesized involvement in exaggerated synaptic elimination during adolescence, which has been suggested to underlie the onset of schizophrenia symptoms during early adulthood [

38]. Systems biology analyses further support the notion that genetically distinct individuals may converge on shared molecular networks, reflecting common downstream mechanisms despite heterogeneous upstream variation [

24,

48,

49].

2.5. Genetic Subtypes and Network Modeling

Data-driven methods start to reveal genetically distinct schizophrenia subgroups that correlate with clinical features. For example, Arnedo and colleagues [

50] analyzed three independent GWAS cohorts totaling 6,500 cases and 8,650 controls, using a kernel-based SNP-set test. This analysis identified five reproducible SNP-sets, each mapping to biological pathways such as glutamatergic synaptic signaling and neurodevelopment. These genetic clusters were associated with differential symptom profiles, distinguishing subgroups predominantly characterized by positive versus negative or cognitive symptoms.

Another method for subgrouping patients was used by Birnbaum & Weinberger [

31] where they used pathway-specific polygenic risk clustering in a deeply phenotyped sample of 12,000 schizophrenia patients. By quantifying polygenic burden across synaptic function, immune signaling, and calcium channel pathways, they identified three distinct subtypes: “synaptic-loaded,” “immune-loaded,” and “mixed”. These labels reflect the dominant biological systems affected by the individual’s genetic risk burden, and the subgroups were found to differ in clinical features and antipsychotic treatment response rates, supporting their potential relevance to precision psychiatry. These emerging network-based and subtype-discovery suggest how molecular profiling can help characterize schizophrenia’s clinical heterogeneity and inform precision-psychiatry interventions.

An overview of the major classes of genetic variants implicated in schizophrenia, their representative loci, frequency, effect sizes, and related key biological pathways is provided in

Table 1.

3. Epigenetic and Chromatin Regulation in Schizophrenia

Brain development and neuronal function heavily depend on epigenetic mechanisms which include DNA methylation and histone modifications as well as three-dimensional chromatin architecture to regulate gene expression. Epigenetic mechanisms were shown to be involved in schizophrenia pathophysiology and these mechanisms are essential disease contributors together with genetic variations [

51,

52]. Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications are dynamic and can be influenced by environmental exposures, making them a plausible link between external risk factors and long-term neurobiological changes. In schizophrenia, multiple human and model-system studies now converge on the idea that maladaptive epigenetic states both mediate genetic risk and translate environmental exposures into long-lasting molecular alterations [

53].

3.1. Environmental Influences on the Epigenome

The fetal brain experiences long-term epigenetic changes because of environmental factors encountered during prenatal development. A growing body of work suggests that schizophrenia’s lifelong risk begins in utero, when maternal exposures leave lasting “marks” on the fetal epigenome [

54,

55]. The combination of maternal infection with malnutrition and psychosocial stress and hypoxia creates early neurodevelopmental problems which make individuals more prone to schizophrenia [

55,

56].

In a series of rodent experiments, Bale and colleagues [

56] subjected pregnant mice to chronic psychosocial stress during the equivalent of the human first and second trimesters. Across three independent cohorts totaling over 30 litters, they showed that offspring of stressed dams exhibited robust changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation within hippocampal and prefrontal cortical neurons. These alterations persisted into adulthood and were accompanied by deficits in working memory and social interaction. These preclinical data provided evidence that early environmental insults can durably remodel the brain’s epigenetic landscape.

Supplementing animal studies, in a large meta-analysis of epidemiological studies of over a million births, Brown and Derkits [

55] found that exposure to maternal influenza, nutritional deprivation or hypoxia in utero were associated with offspring risk for schizophrenia that was increased by 1.5–3-fold. These human data, deriving from peripheral readouts suggest that prenatal immune and metabolic stressors must perturb molecular mechanisms, likely epigenetic. These generate stable alterations in developmentally programed neurodevelopmental trajectories.

Finally, the work of Ursini and co-workers [

57] provided integrative evidence for gene × environment interactions in schizophrenia by directly examining DNA methylation in the human placenta, a key fetal tissue mediating maternal influences. The study analyzed placental biopsies collected at birth from 82 individuals who were later diagnosed with schizophrenia and 75 matched controls (n= 157; 52% male), using genome-wide methylation arrays (>850,000 CpG sites). They reported enrichment of the immune-related (CXCL10, HLA loci) and oxidative-stress-regulator (NFE2L2) methylation signatures at specific genes. In addition, they found a significant polygenic risk score by documented obstetric complications interaction effect for these same CpGs. Pathway analysis of these findings implicated dysregulated placental angiogenesis and cytokine signaling as G×E candidate nodes. These results suggest that epigenetic alterations in the placenta may mediate the biological effects of prenatal environmental stressors in the context of genetic risk. This suggests a mechanistic framework for the developmental origins of schizophrenia.

Together, these findings from animal models [

56], population-scale epidemiology [

55], human placental epigenomic profiling [

57] support a model in which prenatal exposures including infection, nutritional deficiency, psychological stress, and hypoxia may induce persistent epigenetic dysregulation in fetal brain, thereby priming vulnerability to later psychopathology.

3.2. Epigenetic Inhibitory Alterations in Postmortem Brain Tissue

Postmortem studies of the prefrontal cortex have identified overlapping epigenetic dysregulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission in schizophrenia. In one of the first reports, Costa et al. [

58] compared Brodmann area 9 (BA9) tissue from 14 individuals with schizophrenia and 14 non-psychiatric controls obtained via the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Using methylated DNA immunoprecipitation and quantitative PCR, they reported that the RELN promoter CpG island was approximately 50% more methylated in schizophrenia, accompanied by an ~50% reduction in RELN mRNA levels. At the same time, DNMT1 transcript and protein levels were elevated by about threefold, implicating increased maintenance methylation as a mechanism for RELN repression.

Expanding on these observations, Gavin & Sharma [

59] examined dorsolateral PFC (Brodmann area 46) samples (n= 15/group) donated by the schizophrenia and control groups who were matched by race and other demographic characteristics (obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center). Using bisulfite sequencing, they revealed a 40% higher methylation of CpG islands on the GAD1 promoter in schizophrenia while chromatin immunoprecipitation identified a two- to threefold increase in DNMT3A enrichment at the same locus. These epigenetic modifications were associated with nearly >35% reduction of GAD1 (GAD67) transcriptions, linking de novo methylation to impaired inhibitory signaling.

More recently, Nishioka et al. [

60] applied genome-wide MBD-capture sequencing to dorsolateral PFC in 10 schizophrenia cases and 10 controls from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre. They found widespread promoter hypermethylation in schizophrenia, particularly at RELN, GAD1 and other GABAergic genes, and identified by Western blot that both DNMT1 and DNMT3A protein were both almost twice higher in the same cohort.

Cumulatively, the described studies sample nearly 40 schizophrenia and healthy control brains. Collectively, they indicate that up-regulation of the maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1 and/or the de novo enzyme DNMT3A within the PFC mediates hypermethylation and transcriptional silencing of key GABAergic genes (RELN, GAD1). Such changes are likely to contribute to reduced inhibitory signaling and the cortical circuit alterations observed in schizophrenia.

3.3. Histone Modifications and Regulatory Landscapes

Dysregulation of histone modifications besides DNA methylation in schizophrenia has also been proposed to affect the chromatin conformation at critical regulatory regions.

Among the earliest reports, Akbarian et al. [

61] compared histone arginine methylation in post-mortem prefrontal cortex (Brodmann's area 9) from 10 schizophrenia cases and 10 matched control subjects from the Stanley Brain Collection. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), they observed a roughly 2-fold increase in H3meR17 signal across promoters of metabolic genes, most notably glycolytic enzymes, accompanied by a 30–40% reduction in their mRNA levels. This raised the possibility that over-deposition of H3meR17 might suppress the neuronal metabolic pathways in schizophrenia and thereby lead to the disturbances of energy homeostasis in cortex circuits.

Building on these results, Jaffe et al. [

12] performed ChIP-seq for the active enhancer mark H3K27ac in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) from 236 donors (n= 141 schizophrenia, 95 controls) obtained via the CommonMind Consortium. They identified over 3,000 DLPFC enhancers with significantly altered H3K27ac enrichment in schizophrenia. Differentially acetylated enhancers were strongly overrepresented near genes involved in synaptic plasticity (e.g., BDNF, GRIN1), cell-adhesion, and immune signaling, including multiple MHC-linked loci.

More recently, Gusev et al. [

62] combined H3K4me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq data for prefrontal cortex (n= 50 schizophrenia ,50 controls) mapping over 1,200 schizophrenia-associated noncoding variants onto active histone peaks and showed that risk SNPs were enriched at enhancers marked by both H3K4me3 and H3K27ac in excitatory neurons. These “double-marked” regions are heavily enriched for genes mediating synaptic vesicle trafficking, actin cytoskeleton dynamics and complement cascade–mediated pruning (including C4A), suggesting a mechanistic connection between genetic risk and disrupted chromatin states at pathways central to schizophrenia

These ChIP-based studies, from small, focused analyses of histone arginine methylation to large-scale profiling of acetylation and trimethylation marks, further show that the pathological landscape of schizophrenia is characterized by changes in histone modifications at enhancers and promoters that regulate metabolism, synaptic stability, immune activation, and neurodevelopment.

3.4. Chromatin Architecture and Long-Range Interactions

In recent years, three-dimensional chromatin conformation studies have begun to reveal how non-coding schizophrenia risk variants perturb long-range regulatory interactions. Punzi et al. [

63] applied promoter-capture Hi-C to postmortem adult dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) from six donors (three schizophrenia cases, three controls) and identified over 40,000 promoter–enhancer contacts in cis and trans. By intersecting these loops with 145 genome-wide significant schizophrenia loci, they showed that nearly 60% of risk haplotypes contact genes located hundreds of kilobases away, often skipping the nearest gene, and nominate new candidate effectors such as GRIN2B and MEF2C rather than the originally annotated loci.

Complementing this, Wang et al. [

19] performed in situ Hi-C on homogenized adult prefrontal cortex tissue (five neurotypical donors) at ~10 kb resolution. They detected ∼1.2 million chromatin loops, of which schizophrenia risk SNPs were significantly enriched at loop anchors (P < 1×10⁻⁵). For example, risk variants in an intergenic region on chromosome 12q13.2 formed a high–confidence loop to the promoter of GRIN2B, implicating glutamatergic signaling in disease etiology. Similarly, they reported a locus on 5q14.3 looped to MEF2C, a key regulator of synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival.

Additionally, Gusev et al. [

62] integrated schizophrenia GWAS summary statistics with Hi-C data from induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitors and cortical neurons (two lines per cell type) to perform “SNP2Gene” assignments via chromatin interactions. They found that roughly one-third of noncoding risk SNPs colocalize with physically linked gene promoters in neural cells, with a strong bias toward synaptic vesicle and chromatin-remodeling genes. This cell-type–specific loop mapping refines target gene prediction at known loci and highlights novel candidates such as

CACNA2D2 and

SYNGAP1.

Together, these studies demonstrate that many schizophrenia associated noncoding variants exert their effects by rewiring enhancer–promoter contacts in cortical neurons. This provides a direct mechanistic bridge from GWAS signals to dysregulated gene expression in pathways central to synaptic function and neurodevelopment.

3.5. Non-Coding RNAs and Peripheral Epigenetic Signatures

Several groups have now shown that schizophrenia is accompanied by consistent noncoding RNA and peripheral epigenetic signatures across both central and accessible tissues. In one of the first reports, Chen et al. [

64] reviewed evidence from matched postmortem DLPFC and blood-derived plasma studies in schizophrenia and controls. Across these primary investigations, miR-137 was consistently found to be reduced in both compartments, accompanied by de-repression of its targets, including genes involved in synaptic vesicle cycling (e.g.,

SYN2) and inflammatory signaling (e.g.,

IL6R). The same body of work reported upregulation of long noncoding RNAs

NEAT1 and

MALAT1 in patient plasma, which correlated with elevated C-reactive protein and oxidative stress markers. Together, these findings suggest coordinated perturbations in miRNA–lncRNA networks that may contribute to schizophrenia pathophysiology.

Punzi et al. [

63] extended these findings into a neurodevelopmental context by examining miRNA and lncRNA expression in cerebral organoids derived from iPSC models of five schizophrenia patients and five controls. They reported dysregulation of several miR-137 target networks. In particular, those governing synaptic vesicle trafficking and innate immune signaling. They found that correcting miR-137 levels in organoids partially rescued neuronal arborization deficits.Alongside RNA regulators, locus-specific DNA methylation changes have emerged in more accessible tissues. Nishioka et al. [

60] performed genome-wide methylation profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 20 antipsychotic-naïve patients and 20 controls. They showed global hypomethylation and focal hypermethylation at the

DRD2 promoter. Importantly, the

DRD2 gene encodes the dopamine D2 receptor, a primary pharmacological target of antipsychotic drugs.

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that schizophrenia is accompanied by noncoding RNA and DNA-methylation signatures in brain and peripheral tissues as well as well as patients derived brain organoid models. These findings offer a promising, minimally invasive avenue for biomarker development despite ongoing challenges of tissue specificity and replication.

3.6. Therapeutic Potential of Epigenetic Modulation

Pharmacological targeting of chromatin regulators has emerged as a promising field in schizophrenia research. In an in vitro study on the effect of Valproic acid (VPA) on the chromatin, Gavin et al. [

65] treated primary cortical neuron of Sprague–Dawley rat forebrains (n= 4) with valproic acid (VPA) and revealed a 2–3-fold increase in H3K9ac and H3K14ac at the promoters of BDNF and GAD1. These findings correlated with a ~1.8-fold rise in their mRNA expression, demonstrating VPA’s capacity to promote a transcriptionally permissive chromatin state.

Extending these findings to human tissue, Guidotti et al. [

66] examined postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex from schizophrenia patients (n= 12) who had received VPA and matched non-VPA–treated controls (n= 2). They found that VPA exposure was associated with enhanced H3K9ac enrichment at RELN and GAD1 promoters and with increased expression of these GABAergic genes, this further supports the notion that VPA’s HDAC-inhibiting activity can reverse disease-related epigenetic repression.

In in vivo rodent models of stress and NMDA-antagonist–induced deficits—used as proxies for cognitive and social dysfunction—HDAC inhibition similarly yielded behavioral improvement. Covington et al. [

67] subjected male C57BL/6J mice (n= 8 per group) to chronic social-defeat stress and then administered the class I HDAC inhibitor MS-275. Treated animals showed restoration of prefrontal synaptic proteins (PSD-95, synapsin I) and normalized social-interaction behavior compared to vehicle controls. Likewise, Simonini et al. [

68] gave adult Wistar rats (n= 10 per group) sodium butyrate for two weeks following MK-801–induced hyperlocomotion. Sodium butyrate reversed both the locomotor and Y-maze–assessed working-memory deficits, illustrating that broad-spectrum HDAC inhibition can mitigate schizophrenia-relevant phenotypes.

Although broad-spectrum histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors alter global chromatin, recent work has concentrated on more specific small molecules that directly affect DNA methylation or inhibit chromatin "reader" domains. Day and Sweatt (2000) treated rat organotypic hippocampal slices (n= 4) with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor RG108 [

69]. RG108 decreased methylation at the BDNF IV promoter by ∼40% and almost doubled BDNF mRNA expression to twice normal without any cytotoxicity. Nestler et al. [

70] subsequently treated trauma-exposed male C57BL/6J mice with the BET-bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 (50 mg/kg/d, n= 12/group) in the context of chronic unpredictable stress. JQ1 induced recovery of stress-induced reduction of hippocampal synaptic proteins (GluA1, PSD-95) and depressive-like behaviors in forced-swim and sucrose-preference assays, showing that specific inhibition of chromatin readers can particularly rescue synaptic resilience in vivo.

The combination of in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo studies using rodent primary neurons, organotypic slices, cultured cells, postmortem human brain, and live animal models demonstrates that pharmacological modification of histone acetylation, DNA methylation and chromatin-reader proteins can reverse schizophrenia-related molecular and behavioral deficits. The preclinical evidence of efficacy in these agents supports the development of next-generation epigenetic psychopharmacology which uses targeted chromatin regulators to normalize dysregulated transcriptional programs and strengthen synaptic connectivity for improving cognitive and social function in schizophrenia patients.

An overview of the principal epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms implicated in schizophrenia, along with representative studies, tissue sources, regulatory impacts, and core pathways, is presented in

Table 2.

4. Transcriptomic and RNA-Based Dysregulation

In addition to the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms discussed in sections 2-3, an emerging theme in schizophrenia is widespread abnormality of both coding and noncoding RNA species. Comprehensive RNA-seq profiling of major cortical and limbic brain regions has revealed strong, albeit regionally biased alterations in expression that also implicate peripheral cells as a manifestation of systemic disease. For example, Collado-Torres et al. [

71] analyzed postmortem human brain tissue and reported approximately 245 and 48 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (n= 245 schizophrenia, 279 controls) and hippocampus (n= 48 per group), respectively, with little overlap between the two regions. Fromer et al. [

13] examined the superior temporal gyrus in postmortem (n= 40 per group) and reported aberrant synaptic-related transcripts, and Liu et al. [

72] identified postmortem amygdala DEGs (n= 22 schizophrenia, 24 controls) for immune and mitochondrial-related processes.

4.1. Alternative Splicing

Aberrant alternative splicing and isoform expression are hallmarks of schizophrenia transcriptomics. Gandal et al. [

18] performed RNA-seq on postmortem frontal and temporal cortex (n= 258 schizophrenia, 301 controls) and identified over 3,800 differentially expressed isoforms plus 515 splicing events, many within neurotransmitter signaling and immune-related genes. In a separate microarray study of DLPFC (n= 100 schizophrenia, 100 controls), Wu et al. [

73] reported more than 1,000 differentially spliced genes and over 2,000 promoter-usage shifts, including DCLK1 which encodes a microtubule-associated kinase involved in neuronal migration and axonal guidance during neurodevelopment) and PLP1 a major component of central nervous system myelin; critical for oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelin sheath formation. Cohen et al. [

74], using exon-junction arrays on postmortem Brodmann area 10 (n= 40 schizophrenia, 40 controls), detected altered exon usage in synaptic genes ENAH and CPNE3. Jaffe et al.[

12], integrating postmortem DLPFC RNA-seq (n= 191 schizophrenia, 335 controls) with genotype data, showed that many splicing changes co-localize with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), indicating that schizophrenia risk variants can act via isoform-specific transcriptional mechanisms.

4.2. Non-Coding RNAs

Both miRNAs and lncRNAs are being increasingly reported as implicated in schizophrenia. In the first genome-wide small-RNA-seq study of postmortem amygdala (n= 13 schizophrenia, 14 controls), Liu et al. [

72] observed global miRNA down-regulation (notably miR-1307 and miR-34 family). These changes were associated with de-repression of predicted synaptic and inflammatory targets. In another study conducted on LCLs (n= 20 schizophrenia, 20 controls) Sanders et al. [

75] found about 35% reduction in DICER1 expression, implicating impaired miRNA biosynthesis as a potential mechanism. Mir-137 is a brain-enriched microRNA with demonstrated roles in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Olde Loohuis et al. [

76] reported that miR-137 regulates neurodevelopmental processes and plasticity in rodent hippocampal neurons, identifying numerous downstream mRNA targets through gain- and loss-of-function experiments. Moreover, the MIR137 locus ehich encodes miR-137 is one of the most highly significant schizophrenia GWAS hits [

77]. Gandal et al. [

18] further identified lncRNA co-expression modules in DLPFC (n= 258 schizophrenia, 301 controls) enriched for immune and neurodevelopmental pathways. Importantly, Geaghan et al. [

78] described sex-specific miRNA–mRNA interactions in PBMCs (n= 36 schizophrenia, 15 controls), highlighting additional layers of regulatory complexity.

4.3. Tissue Specificity and Peripheral Transcriptomic Profiles

Transcriptomic signatures in schizophrenia were often reported to be tissue-specific. For example, Collado-Torres et al. [

71] analyzed postmortem human brain tissue and demonstrated minimal overlap in DEGs across DLPFC, hippocampus, Brodmann area 10, and superior temporal gyrus (n= 40-280 per region). In contrast, accessible peripheral cells such as LCLs (n= 20 schizophrenia, 20 controls) [

75] and PBMCs (n= 36 schizophrenia, 15 controls) [

78] exhibit reproducible immune-related expression changes. Although these peripheral profiles may reflect systemic or non-neuronal effects, they highlight possible opportunities for minimally invasive diagnostic biomarkers and longitudinal disease monitoring.

4.4. Co-Expression Networks and Systems-Level Convergence

Schizophrenia appears to involve coordinated dysregulation of gene modules, rather than isolated gene-level effects. hits. In postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Fromer et al. [

13] applied weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to RNA-seq results from 258 schizophrenia cases and 279 controls. They identified large co-expression modules enriched for synaptic transmission genes. Importantly, these modules overlapped with genome-wide significant schizophrenia risk loci. Independently, Gandal et al. [

18] reconstructed very similar modules in frontal and temporal cortex (258 cases, 301 controls), driven by both common and rare risk variants [

46]. These modules have been proposed to act as intermediate molecular phenotypes, comprising synaptic, immune, and metabolic genes that may serve as convergence points for genetic risk. revealing how diffuse genetic liability converges on tightly co-regulated networks of synaptic, metabolic and immune genes. Schizophrenia-associated modules have been reported to show reduced intramodular connectivity, meaning weaker co-regulation, in cases compared to controls, with similar patterns replicated in independent datasets [

13,

18].

A concise summary of key transcriptomic findings, sample types, affected genes, regulatory changes, and convergent pathways is provided in

Table 3.

5. Proteomic and Functional Phenotypes

Building on the genetic, epigenetic and transcriptomic landscapes outlined in

Section 2,

Section 3 and

Section 4, proteomic analyses proteomic analyses provide an additional layer of insight into schizophrenia by characterizing protein-level changes that may reflect downstream effects of molecular variation. Mass spectrometry studies of postmortem cortical tissue have reported alterations in proteins associated with synaptic vesicle cycling, long-term potentiation machinery and mitochondrial respiratory complexes [

80,

81]. Peripheral blood-based assays, including multiplex immunoassays have identified immune-inflammatory profiles and candidate treatment-responsive protein panels. These findings suggest a possible correspondence between central proteome alterations and accessible biomarkers. In

Section 5.1–5.4, we synthesize these findings, spanning synaptic and mitochondrial proteome remodeling, immune and peripheral protein markers, post-translational modifications, and translational biomarker validation highlighting potential points of convergence that could inform more personalized approaches to diagnosis and therapy.

5.1. Synaptic and Mitochondrial Proteome Disruption

Targeted proteomic analyses of postsynaptic density (PSD) fractions have been particularly informative for dissecting synaptic abnormalities in schizophrenia. Föcking et al. [

82] applied shotgun proteomics to PSD isolates from the anterior cingulate cortex of 20 schizophrenia cases and 20 matched controls. They identified more than 700 PSD-associated proteins, of which 143 were differentially expressed, including key regulators of vesicle cycling and mitochondrial function. Among them DNM1, MAPK3, and AP2B1, which are central to synaptic vesicle cycling, endocytosis, and long-term potentiation. Another study by MacDonald et al. [

83] profiled the auditory cortex (n= 48 schizophrenia, 48 controls) and reported co-occurring differences in disturbances in PSD components (PSD-95, SHANK3) and mitochondrial respiratory complexes. Together, these observations suggest that alterations in neurotransmission and cellular energy metabolism may occur in parallel in schizophrenia. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to clarify their extent and causal relationships.

5.2. Immune Signatures and Peripheral Protein Markers

Multiplex immunoassays have been widely applied to investigate peripheral protein alterations in schizophrenia, enabling the identification of candidate biomarkers with potential translational utility. Schwarz et al. [

84] measured 181 proteins and small molecules by multiplex immunoassay in 250 first-episode or recent-onset schizophrenia patients, 280 healthy controls, and additional psychiatric groups (35 MDD, 32 bipolar and 45 Asperger syndrome). In an initial discovery cohort of 71 schizophrenia versus 59 matched controls, they derived a 34-analyte “serum signature” comprising cytokines, growth factors and endocrine markers. When tested across five independent cohorts, this panel classified schizophrenia cases versus controls with 60–75% accuracy and partially stratified MDD (~50%) and bipolar/Asperger cases (~10–20%). Ramsey et al. [

85] assayed >100 analytes in serum from 150 schizophrenia patients (75 men, 75 women) and 150 controls, reporting 65 sex-specific protein differences in hormonal and inflammatory markers. Domenici et al. [

86] conducted a study plasma of 229 schizophrenia patients and 254 controls, confirming that a panel enriched for immune- and metabolism-related proteins, notably IL-6, CRP, and BDNF, which discriminated cases from controls. Beyond case-control stratification, proteomic profiling has also been studied to predict treatment response. Föcking et al. [

87] showed, in a cohort of 30 amisulpride-treated patients, that treatment responders have elevated complement and coagulation factors (CFI, C4A, VWF). This suggests that such profiles could potentially serve as peripheral indicators of treatment response. Elevated complement factors, particularly C4A, are of mechanistic interest because structural variation in the C4 locus has been genetically linked to schizophrenia risk. Increased C4A expression has been implicated in excessive synaptic pruning during neurodevelopment [

38]. Collectively, these studies indicate that peripheral proteomic signatures encompass immune, hormonal, and metabolic alterations, and that certain profiles may hold value both for diagnostic stratification and for guiding personalized treatment strategies.

5.3. Post-Translational and Signaling Modifications

Proteomic evidence also points to dysregulation of post-translational regulatory mechanisms in schizophrenia. Jaros et al. [

88] performed phosphoproteomics to plasma from 50 schizophrenia patients and 50 controls. The study revealed altered phosphorylation of acute-phase proteins and key intracellular signaling molecules including Akt1 and STAT3. These changes may provide a mechanistic link between immune-inflammatory activation and downstream cellular signaling abnormalities. In a complimentary approach, Tomasik et al. [

89] analyzed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from 20 cases and 20 controls and reported aberrant phosphorylation of coagulation factors and synaptic scaffolding proteins. Notably, several of these phosphorylation changes correlated with both symptom severity and antipsychotic exposure. These findings raise the possibility that altered post-translational regulation is associated with both disease processes and treatment effects.

Representative proteomic studies, analytical platforms, altered proteins, and implicated biological processes are summarized in

Table 4.

6. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Models Elucidate Schizophrenia Pathophysiology

Patient-derived iPSC models now make it possible to interrogate schizophrenia’s cellular and molecular phenotypes in a human-specific context. Stern et al. [

27] studied hippocampal neurons from monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia and reported that neurons from affected individuals had reduced arborization, hypoexcitability with immature spike features, and diminished synaptic activity. Neurons from unaffected co-twins displayed intermediate characteristics, reinforcing potential contributions from both genetic predisposition and post-zygotic factors. Similarly, earlier work by Brennand et al. [

90] demonstrated that hiPSC-derived neurons from familial schizophrenia cases exhibit diminished neurite outgrowth, reduced synaptic marker expression, and impaired connectivity compared with controls. Subsequent work using a range of cellular models including two-dimensional neuronal cultures, cerebral organoids, interneuron–glia co-cultures, oligodendrocyte precursor models, and astrocyte-neuron systems has shown convergent disruptions in synaptic signaling, mitochondrial function, neurodevelopment, and glial support [

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96].

6.1. Early Neurodevelopmental Perturbations and Transcriptional Dysregulation

Neurodevelopmental abnormalities in schizophrenia can emerge as early as the neural progenitor stage. Brennand et al. [

90] examined patient-derived forebrain neural progenitor cells (NPCs) from four schizophrenia and four control iPSC lines using both transcriptomic and quantitative proteomic approaches. They identified 312 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) and protein-level alterations linked to cytoskeletal remodeling and oxidative stress, including a 1.7-fold downregulation of NCAM1, 1.5-fold of NRXN1, and 1.6-fold of NLGN1, alongside a 2.2-fold increase in antioxidant-enzyme transcripts. Functionally, schizophrenia NPCs migrated 35% more slowly in neurosphere assays and produced 28% more reactive oxygen species in DCFDA assays. Complementing these findings, Ahmad et al. [

91] reported altered microRNA expression in schizophrenia NPCs, with ~1.8-fold elevation of miR-137 and ~1.4-fold reduction of miR-9. This is corresponding to reduced SOX2 and PAX6 protein levels and delayed MAP2 expression. The combined findings indicate that schizophrenia NPCs phenotypes span coordinated transcriptional, epigenetic and functional disruptions. These alterations at the NPC stage may compromise the timing and fidelity of early neuronal development.

6.2. Mitochondrial Malfunction and Oxidative Stress

Robicsek et al. [

96] examined mitochondrial function in patient-derived neurons, reprogramming hair-follicle cells extracted from 3 schizophrenia and 2 control donors into dopaminergic (TH⁺) and glutamatergic (vGLUT1⁺) neurons. They observed 30% increase in mitochondria fission, 25% decrease in membrane potential and 35% increase in ROS. These changes were associated with a 20 % reduction in neurite length. In extending these 2D neuron results, Kathuria et al. [

93] have probed mitochondrial function in 3D cerebral organoids from (n= 8SZ, 8CTL) iPSC lines and showed 22 % decrease in basal O2 consumption rate and 28 % reduction in ATP-linked respiration as well as 40 % lower Spike rate. While these studies differ in model type, both point toward mitochondrial structural and functional alterations, along with oxidative stress, as potential cell-autonomous features in schizophrenia iPSC models.

6.3. Synaptic Connectivity and Dendritic Architecture

To assess synaptic structure and function, Brennand et al. [

29] differentiated 4 schizophrenia (one 22q11.2del) and 4 control lines into cortical neurons. Immunostaining showed about 40% fewer PSD-95 puncta in patients’ neurons, and Sholl analysis revealed a 35% reduction in dendritic intersections. Whole-cell patch-clamp recorded a 50% lower frequency of spontaneous EPSCs. Chronic treatment with loxapine increased PSD-95 density by 25% and EPSC frequency by 30%. In a parallel study, Pedrosa et al. [

97] studied 3 schizophrenia vs. 3 control glutamatergic neurons and found sustained OCT4/NANOG expression through day 60, with Synapsin-1 and Neurexin-1 cluster densities reduced by ~32% and ~28%, respectively, compared to controls. Extending these findings to a genetically controlled context, Stern et al. [

27] examined hippocampal neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of four pairs of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Neurons from affected twins exhibited reduced dendritic complexity, fewer secondary and tertiary branches, and decreased total dendritic length. Electrophysiological recordings revealed lower spontaneous and evoked synaptic activity, reduced firing rates, diminished sodium and potassium current amplitudes, and immature action potential waveforms. Paired recordings and miniature EPSC analyses indicated both presynaptic and postsynaptic deficits, including reduced release probability and lower AMPA/NMDA current ratios. Notably, neurons from unaffected co-twins displayed intermediate values across parameters, suggesting that both shared genetic liability and non-shared, potentially post-zygotic, influences may contribute to these cellular phenotypes. Collectively, these studies suggest that alterations in synaptic maturation and excitability are recurring features in patient-derived neuronal models of schizophrenia.

6.4. Organoid and Interneuron Circuit Deficits

Investigating network-level vulnerabilities, Kathuria et al. [

94] co-cultured cortical interneurons from 9 schizophrenia and 9 control lines with excitatory neurons. schizophrenia interneurons showed a 30% reduction in VGAT⁺ puncta, 42% lower GAD67, 38% lower gephyrin, and 45% lower NLGN2 by immunoblot; either NLGN2 overexpression or N-acetylcysteine restored synaptic puncta and increased the mean firing rate by ~50%. Building on this circuit-level framework, Notaras et al. [

95] profiled 25 organoids from 9 schizophrenia and 5 control donors. TMT proteomics identified 150 proteins altered >1.5-fold, including a 50% drop in BRN2 and 60% in PTN in schizophrenia organoids. Adding pleiotrophin for 7 days increased BRN2 levels by 2.2-fold, improved progenitor survival by 40%, and doubled NeuN⁺ neuron counts. Together, these studies point to network-level vulnerabilities in both 2D interneuron co-cultures and 3D organoids. This indicatrs that certain synaptic and progenitor-survival deficits in schizophrenia models can be partially ameliorated by targeted molecular interventions.

6.5. Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell Dysfunction

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) are immature glial cells capable of differentiating into myelinating oligodendrocytes, thereby playing a critical role in central nervous system development, axonal insulation, and white matter repair [

98]. While most patient-derived iPSC studies in schizophrenia have focused on neuronal phenotypes (see

Section 6.2–6.4), glial impairments have also been reported. In a family-based investigation, de Vrij et al. [

92] generated NG2⁺ oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) from three CSPG4-mutation carriers with schizophrenia and three unaffected siblings to probe glial contribution to disease pathology. Patient-derived OPCs accumulated a threefold increase in high-mannose NG2 species and mislocalized NG2 within the Golgi but core myelin proteins MBP and PLP1 were reduced by 45% and 50%, respectively. Expression of key transcriptional regulators of OPC maturation (

SOX10 and

OLIG2) were each ~30 % lower in schizophrenia-derived OPCs. These findings suggest that OPC and myelin-gene dysregulation may occur alongside the synaptic, neurodevelopmental, and mitochondrial alterations described in earlier subsections. Which suggests that multiple cell types could contribute to schizophrenia-related pathology.

At the molecular level, iPSC-based studies pinpoint specific genes and pathways that are repeatedly implicated across some schizophrenia models. These include alterations in synaptic assemblies, energy metabolism, cell-adhesion complexes, and myelin-gene networks. Such findings, while still limited in number, suggest recurring biological themes that merit further validation. Patient-derived iPSC models now enable interrogation of schizophrenia’s cellular phenotypes in a human-specific context. In

Section 7, we integrate these cellular and molecular insights to explore potential avenues toward precision medicine in schizophrenia.

An overview of iPSC-based models, cell types, observed phenotypes, and their relevance to schizophrenia pathology is presented in

Table 5.

7. Systems Integration: Recurring Molecular Pathways

Findings from genome-wide studies, epigenomic profiling, transcriptomics, proteomics, and patient-derived cellular models suggest that, despite methodological and tissue-specific differences, certain biological themes emerge repeatedly. These include alterations in synaptic signaling, mitochondrial function, cell-adhesion complexes, immune regulation, and neurodevelopmental pathways (summarized in

Table 6.).

7.1. Synaptic Signaling

Genome-wide association studies have repeatedly highlighted synaptic genes like

CACNA1C,

GRIN2A,

DLG2 each contributing modest risk [

11,

36,

46]. Rare copy-number variants (e.g., 22q11.2 deletions) and high-penetrance loss-of-function alleles (SETD1A) further implicate synaptic assembly and plasticity networks [

20,

47]. In the epigenome, neuron-specific H3K27ac and H3K4me3 landscapes are enriched for schizophrenia risk variants at enhancers of postsynaptic genes [

99], while DNA methylation shifts in the DLPFC affect synaptic loci [

12]. Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) link synaptic gene expression changes to schizophrenia risk loci [

62], and Hi-C maps connect these loci to GRIN2B and MEF2C promoters [

100]. At the transcript level, co-expression modules enriched for synaptic transmission and receptor scaffolds are disrupted in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [

13,

18], with isoform-specific splicing of DLG2 and SHANK2 further skewing synaptic composition [

18]. Proteomic surveys confirm depletion of PSD-95, SHANK3, and other postsynaptic density proteins in anterior cingulate and auditory cortices [

82,

83], phosphoproteomic studies in patient serum report altered phosphorylation patterns implicating dysregulated kinase signaling [

88]. Finally, patient-derived iPSC neurons recapitulate these deficits: cortical cultures show ~40% fewer PSD-95 puncta, 50% fewer spontaneous excitatory currents, and partial rescue with loxapine [

29], while interneuron co-cultures highlight NLGN2-dependent GABAergic synaptic failures [

94].

7.2. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics

Genetic evidence links mitochondrial function to schizophrenia. De Vrij et al. [

92] identified rare variants in mitochondrial electron-transport chain (ETC) genes in familial schizophrenia cases. Notaras et al. [

95] reported that patient-derived cerebral organoids display downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) genes, particularly in neurons and astrocytes, and show increased vulnerability to metabolic stress. Epigenetically, Akbarian et al. [

61] examined postmortem PFC tissue from schizophrenia patients and found reduced histone H3 arginine 17 dimethylation (H3R17me2) at promoters of genes encoding metabolic enzymes, alongside reduced transcription of mitochondrial and glycolytic pathway genes. At the transcriptomic level, Collado-Torres et al. [

71] analyzed dorsolateral PFC samples from 258 schizophrenia cases and 279 controls, revealing coordinated downregulation of OXPHOS co-expression modules, implicating respiratory complexes I–V. Proteomic studies indicate that mitochondrial respiratory-complex subunits are co-regulated with synaptic proteins and reduced in schizophrenia cortex. Föcking et al. [

82] reported decreased abundance of NDUFV2 (complex I) and UQCRC1 (complex III) in anterior cingulate cortex of schizophrenia patients. MacDonald et al. [

83] similarly observed reduced ATP5A1 (complex V) in primary auditory cortex, which correlated with reduced PSD-95 levels [

82,

83]. Functional modeling confirms mitochondrial deficits. In vitro, iPSCs patient-derived dopaminergic and glutamatergic neurons exhibit 30% increase in mitochondrial fragmentation, 25% membrane potential decrease, and 35% reactive oxygen species increase [

96]. Three-dimensional cerebral organoids have 22% decreased basal oxygen consumption rate and a 40% decrease in spontaneous neuronal spiking frequency relative to controls [

93].

7.3. Cell-Adhesion Complexes

Genetic evidence implicates both common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in NCAM1, NRXN1, and NLGN1 and rare copy number variants (CNVs) in cell-adhesion pathways critical for neurite outgrowth and synapse formation [

11,

90]. Epigenetic analyses demonstrate hypermethylation and transcriptional silencing of RELN in the prefrontal cortex, potentially disrupting extracellular matrix interactions and synaptic organization [

58,

59]. Transcriptomic profiling reveals widespread dysregulation of protocadherins and adhesion factor isoforms across cortical regions in schizophrenia [

18]. Proteomic investigations identify altered abundance and phosphorylation of adhesion scaffolds, including AP2B1 and DNM1, in both serum and brain tissue from affected individuals [

82,

88]. Functional modeling in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) systems shows that forebrain neural progenitor cells (NPCs) derived from schizophrenia patients migrate approximately 35% more slowly than controls and exhibit 1.5–1.7-fold lower expression of

NCAM1,

NRXN1, and

NLGN1 [

90]. Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) from CSPG4-mutation carriers display NG2 mislocalization alongside reduced expression of myelin proteins MBP and PLP1 [

92].

7.4. Immune Regulation

Variants in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), particularly complex structural variation in the C4A gene, increase complement activity and are strongly associated with excessive synaptic pruning in schizophrenia [

38]. human placenta and peripheral blood have identified immune-gene methylation signatures that interact with polygenic risk and obstetric complications, suggesting a combined genetic and environmental contribution to immune dysregulation [

57,

60]. Transcriptomics in both brain and periphery, including large-scale RNA-seq analyses of postmortem cortex and exon-array profiling of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, highlight upregulated cytokine and microglial modules in schizophrenia [

18,

75]. Co-expression network analyses integrating thousands of brain transcriptomes position immune genes, particularly those in complement and interferon pathways, at the core of schizophrenia risk modules [

19,

101]. Serum proteomic assays identify reproducible “immune signatures” (IL-6, CFI, C4A) that stratify cases and forecast treatment response [

84,

87]. Patient-derived iPSC organoids and interneuron co-cultures similarly show dysregulated complement and cytokine pathways. These alterations were shown to be partially normalized by pleiotrophin supplementation or N-acetylcysteine treatment [

94,

95].

7.5. Neurodevelopmental Regulation

Schizophrenia risk is evident during prenatal and early postnatal brain development, where both inherited variants and environmentally induced epigenetic alterations converge to disrupt neuronal differentiation and progenitor viability. Recurrent 22q11.2 microdeletions and rare loss-of-function variants in POU3F2 (BRN2) and pleiotrophin (PTN) implicate transcriptional regulators that govern cortical patterning and cell–matrix interactions [

92,

95]. Genome-wide methylation profiling of human placenta identifies differentially methylated regions at PAX6 and SOX2, demonstrating that obstetric complications interact with genetic liability to modify developmental histone marks and DNA methylation landscapes [

57]. In vitro, induced pluripotent stem cell–derived neural progenitor cells from schizophrenia patients exhibit reduced expression of NCAM1, NRXN1 and NLGN1, dysregulated miR-137/PAX6 signaling, delayed neuronal marker expression, impaired migration and elevated oxidative stress [

90,

91]. Three-dimensional cerebral organoids recapitulate these phenotypes, displaying approximately 50 % reductions in BRN2 and PTN protein levels; importantly, exogenous pleiotrophin supplementation or BRN2 overexpression restores progenitor survival and increases neuronal differentiation [

95]. Collectively, these data define a neurodevelopmental axis in schizophrenia whereby genetic perturbations and prenatal epigenetic modifications intersect to derail early cortical maturation.

7.6. Convergence Genes

Several genes emerge repeatedly across genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and patient-derived cellular studies, indicating that they may occupy central nodes within core pathways of schizophrenia.

DLG4 (PSD-95): Although not itself a GWAS hit, the PSD-95 scaffold shows concordant dysregulation at multiple levels: reduced H3K27ac at its enhancer in DLPFC [

12]; decreased mRNA in DLPFC [

13]; lower protein abundance in anterior cingulate and auditory cortex [

82,

83]; and fewer PSD-95 puncta accompanied by reduced spontaneous EPSCs in patient-derived cortical neurons, which are rescued by loxapine [

29].

C4A/C4B: Complement components encoded in the MHC region stand out across modalities: complex structural variation at C4A/C4B associates with risk [

38]; enhancer marks H3K4me3/H3K27ac at C4 loci are enriched in schizophrenia neurons [

62]; elevated C4A transcript levels appear in immune gene co-expression modules [

18]; and higher serum C4A/C4B protein distinguishes treatment responders [

87].

NRXN1 / NLGN1: These presynaptic adhesion molecules are disrupted genetically by rare CNVs and GWAS signals [

11,

20]; their mRNA is downregulated in patient NPCs [

90]; and their puncta/clusters are reduced in iPSC-derived cortical and glutamatergic neurons [

29,

97].

MT-CO1, ATP5A1 (OXPHOS subunits): Key components of mitochondrial respiratory chain Complexes I–V show downregulation at the protein level in postmortem cortex [

82], and fragmented low-potential mitochondria with increased reactive oxygen species in patient iPSC neurons [

96].

RELN: The reelin adhesion cue is epigenetically silenced by promoter hypermethylation in BA9 (14 vs. 14) [

58], shows reduced mRNA in DLPFC [

59], and is reactivated at both the chromatin and transcriptional level in VPA-treated patients [

66].

BRN2 (POU3F2), PTN (pleiotrophin): Two factors involved in neuronal differentiation and adhesion are consistently downregulated in schizophrenia organoids [

95]; exogenous pleiotrophin or BRN2 overexpression rescues progenitor survival and neuronal output in these 3D models [

95].

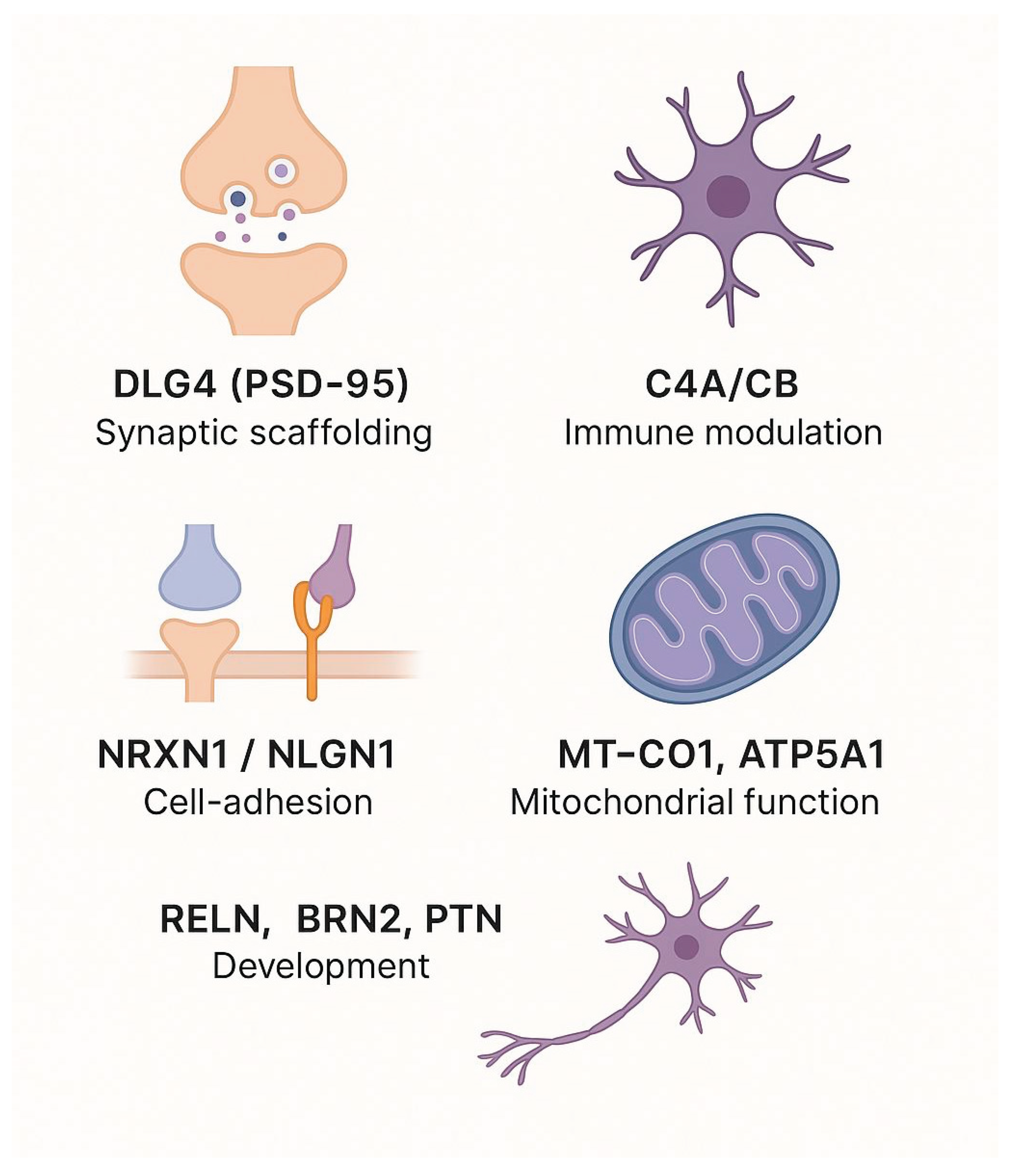

The genes discussed above have been recurrently implicated across multiple molecular layers, including genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and patient-derived cellular studies (

Table 7 and

Figure 2). They are linked to fundamental biological processes such as synaptic scaffolding, immune modulation, cell adhesion, mitochondrial function, and developmental regulation. While their consistent identification across independent datasets suggests potential points of convergence in schizophrenia, this observation is based on selected representative studies rather than a comprehensive quantitative synthesis. While their repeated identification across independent datasets suggests potential points of convergence in schizophrenia, they merit further quantitative analysis to validate this potential convergence and determine their mechanistic roles, as well as their potential utility as biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

Table 7. Genes listed here were selected based on evidence from at least three distinct molecular levels: genetics, epigenetics/chromatin, transcriptomics, proteomics, and/or iPSC-based models in schizophrenia. This threshold was chosen to emphasize genes with recurrent, cross-platform support, reflecting higher confidence in their involvement across biological scales. References cited are representative examples and not an exhaustive list.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this review, we examine schizophrenia’s molecular landscape across genetic and epigenetic variation, transcriptomic and proteomic alterations, and eventually in iPSC-based functional models. We demonstrate that, despite their apparent divergence, these signatures may coalesce around a defined set of core biological pathways. The recurrent involvement of synaptic, immune, mitochondrial, neurodevelopmental, and adhesion-related mechanisms across diverse molecular studies highlights potential axes of convergence in schizophrenia. These patterns merit systematic validation through integrative and large-scale investigations.

When findings from these molecular layers are compared, certain genes emerge with evidence across three or more domains (

Table 7). Such recurrence may indicate particularly robust biological signals, although it is equally possible that these genes are overrepresented due to methodological biases or research focus. Careful, quantitative meta-analysis will therefore be required to assess their true contribution to disease biology.

This synthesis is qualitative, drawing on representative studies to highlight recurrent molecular themes. While this provides a useful framework, systematic reviews and quantitative approaches are needed to evaluate the consistency and magnitude of these effects across larger datasets.

Future work should focus on integrating ancestrally diverse cohorts to improve generalizability, applying single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to dissect cell type– and circuit-level processes, and advancing clinically compatible pipelines for multimodal biomarker identification. Parallel to scientific progress, ethical frameworks must ensure equitable and responsible implementation of emerging technologies.

Continued integration of multi-level molecular data, alongside careful validation, will be essential for clarifying the biological underpinnings of schizophrenia and informing future efforts toward precision psychiatry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Malak Saada and Shani Stern; Investigation, Malak Saada; Resources, Shani Stern; Data curation, Malak Saada; Writing: original draft preparation, Malak Saada; Writing review and editing, Malak Saada and Shani Stern; Visualization, Malak Saada; Supervision, Shani Stern; Project administration, Shani Stern; Funding acquisition, Shani Stern. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rubeša, G., L. Gudelj, and N. Kubinska, Etiology of schizophrenia and therapeutic options. Psychiatr Danub 2011, 23, 308–15. [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo, A. and O. Onaolapo, Schizophrenia Aetiology and Drug Therapy: A Tale of Progressive Demystification and Strides in Management. Advances in Pharmacology and Pharmacy 2018, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hilker, R.; et al. Heritability of Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia Spectrum Based on the Nationwide Danish Twin Register. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyllested, A. Schizophrenia. Current biological theories on the etiology. Ugeskrift for laeger 1996, 158, 4273–7. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, E., V. Mittal, and K. Tessner, Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008, 4, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandarakalam, J.P. The Autoimmune and Infectious Etiological Factors of a Subset of Schizophrenia. 2015.

- English, J.A.; et al. Reduced protein synthesis in schizophrenia patient-derived olfactory cells. Translational Psychiatry 2015, 5, e663–e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obiols, J.E. and J. Vicens-Vilanova, Etiología y Signos de Riesgo en la Esquizofrenia. International journal of psychology and psychological therapy 2003, 3, 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Insel, T.R. , Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature 2010, 468, 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, R.S.; et al. Schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2015, 1, 15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripke, S.; et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.E.; et al. Mapping DNA methylation across development, genotype and schizophrenia in the human frontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience 2016, 19, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromer, M.; et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience 2016, 19, 1442–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariaga-Martinez, A., J. Saiz-Ruiz, and R. Alelú-Paz, From Linkage Studies to Epigenetics: What We Know and What We Need to Know in the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia. Front Neurosci 2016, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, E.; et al. Epigenetic Studies of Schizophrenia: Progress, Predicaments, and Promises for the Future. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2012, 39, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trubetskoy, V.; et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature, 2022. 604.

- Hoffman, G.E.; et al. Transcriptional signatures of schizophrenia in hiPSC-derived NPCs and neurons are concordant with post-mortem adult brains. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandal, M.J.; et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science 2018, 362, eaat8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science 2018, 362, eaat8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, D. and J. Sebat, CNVs: Harbingers of a Rare Variant Revolution in Psychiatric Genetics. Cell 2012, 148, 1223–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F., M. J. Daly, and M. O'Donovan, Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmann-Winter, K.E.; et al. The proteome and its dynamics: A missing piece for integrative multi-omics in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 2020, 217, 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, J.M. and D. Martins-de-Souza, The proteome of schizophrenia. npj Schizophrenia 2015, 1, 14003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; et al. Integrative omics of schizophrenia: from genetic determinants to clinical classification and risk prediction. Molecular Psychiatry 2022, 27, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; et al. A Perspective of the Cross-Tissue Interplay of Genetics, Epigenetics, and Transcriptomics, and Their Relation to Brain Based Phenotypes in Schizophrenia. Frontiers in Genetics, 2018. Volume 9 - 2018.

- Burrack, N.; et al. Altered Expression of PDE4 Genes in Schizophrenia: Insights from a Brain and Blood Sample Meta-Analysis and iPSC-Derived Neurons. Genes 2024, 15, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.; et al. Monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia differ in maturation and synaptic transmission. Molecular Psychiatry 2024, 29, 3208–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; et al. Efficient Generation of CA3 Neurons from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Enables Modeling of Hippocampal Connectivity In Vitro. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 684–697.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennand, K.J.; et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2011, 473, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovsky, E.; et al. Uncovering convergence and divergence between autism and schizophrenia using genomic tools and patients’ neurons. Molecular Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, R. and D.R. Weinberger, Genetic insights into the neurodevelopmental origins of schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2017, 18, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, L.; et al. Immunoglobulin genes expressed in lymphoblastoid cell lines discern and predict lithium response in bipolar disorder patients. Molecular Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4280–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, O.; et al. Predicting Suicide Risk in Bipolar Disorder patients from Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines genetic signatures. bioRxiv, 2024, p. 2024.05.30.596645.

- Stern, S.; et al. Prediction of response to drug therapy in psychiatric disorders. Open Biology 2018, 8, 180031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J., A. Sawa, and P.B. Mortensen, Schizophrenia. The Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trubetskoy, V.; et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 2022, 604, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511, 421–7. [CrossRef]

- Sekar, A.; et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 2016, 530, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifman, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Identifies a Common Variant in the Reelin Gene That Increases the Risk of Schizophrenia Only in Women. PLOS Genetics 2008, 4, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.M.; et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 2009, 460, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legge, S.E.; et al. Genetic architecture of schizophrenia: a review of major advancements. Psychological Medicine 2021, 51, 2168–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.; et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nature Genetics 2022, 54, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.R.; et al. Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nature Genetics 2017, 49, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.M.; et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 2014, 506, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardiñas, A.F.; et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nature Genetics 2018, 50, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; et al. Rare coding variants in ten genes confer substantial risk for schizophrenia. Nature 2022, 604, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsley, K.G. et al. Convergent impact of schizophrenia risk genes. 2022.

- Roussos, P.; et al. A System-Level Transcriptomic Analysis of Schizophrenia Using Postmortem Brain Tissue Samples. Archives of General Psychiatry 2012, 69, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]