Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

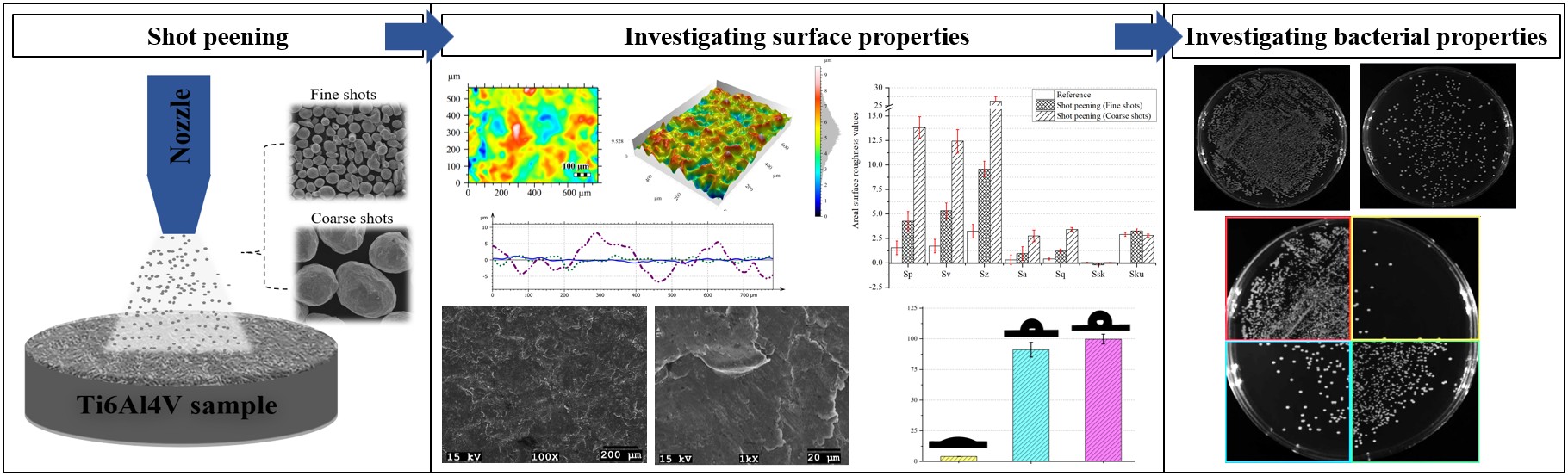

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

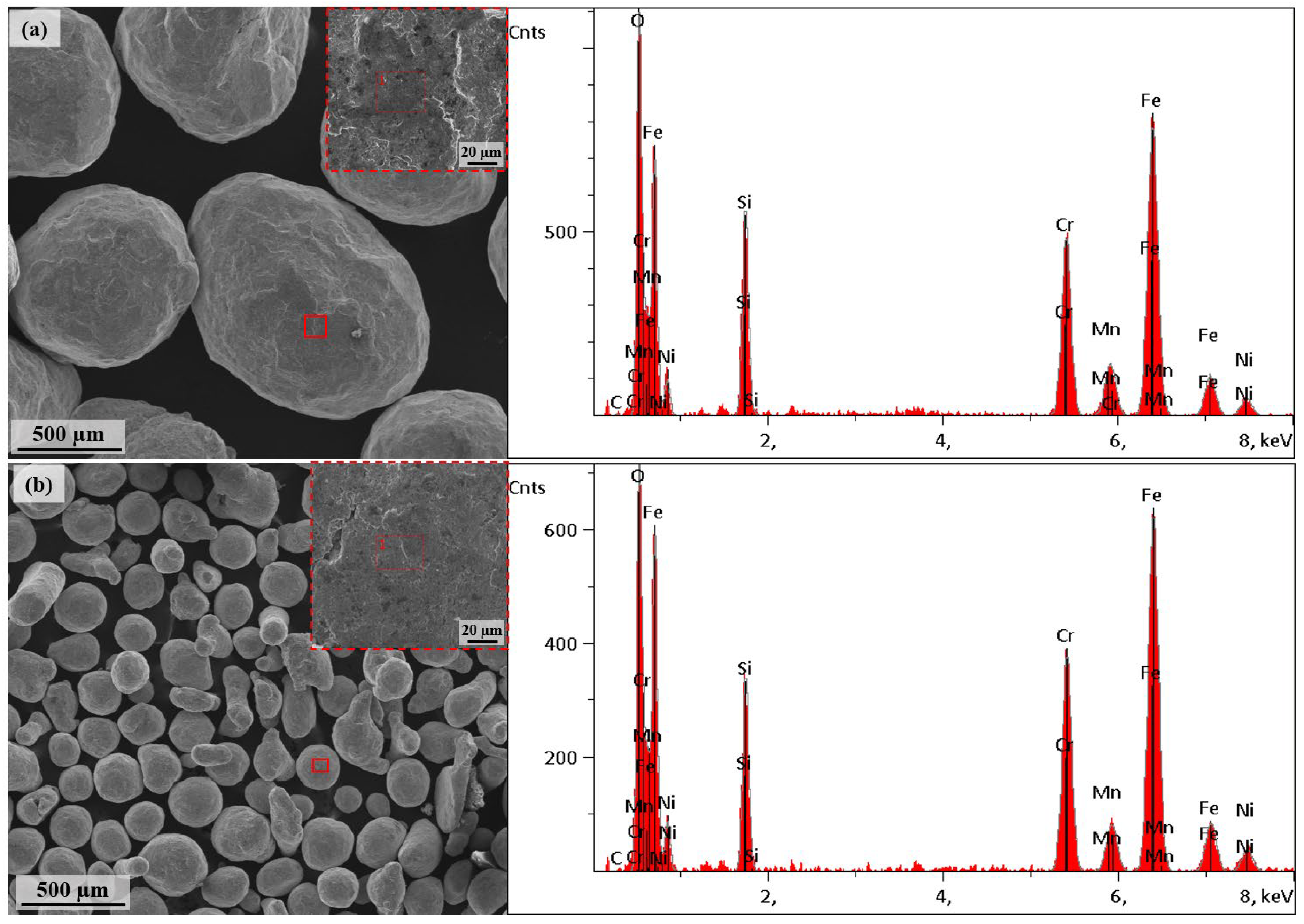

2.1. Materials

2.2. Shot Peening of Ti6Al4V Alloy

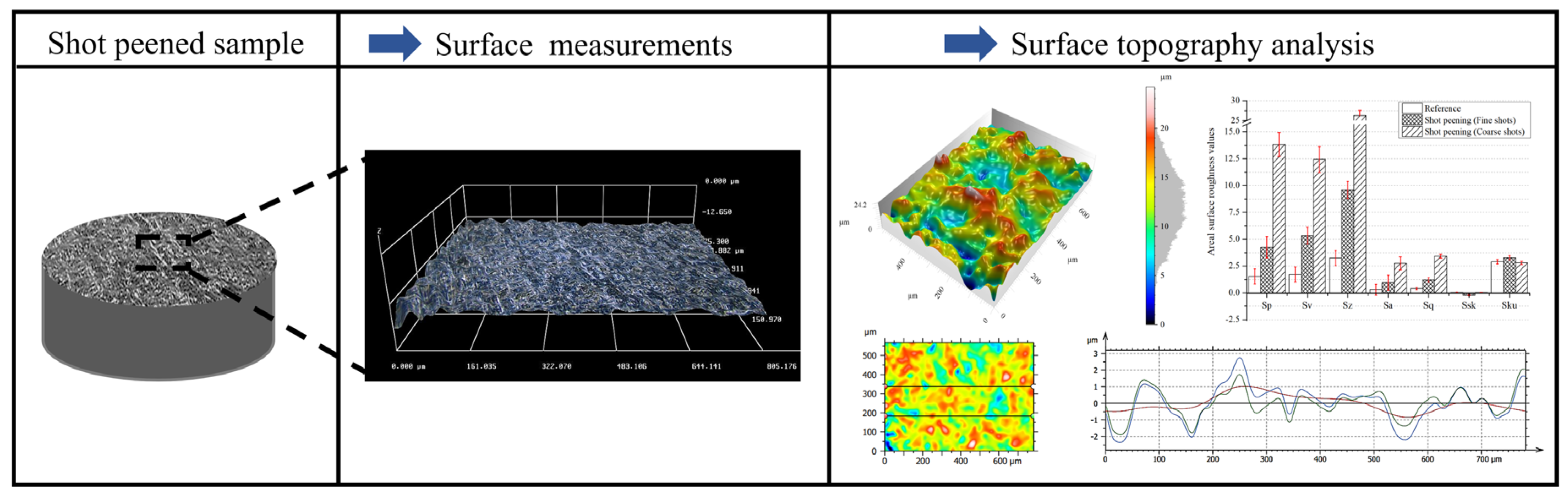

2.3. Surface Characterisation of Shot-Peened Alloy

2.4. Antibacterial Activity of Shot-Peened Surface

3. Results and Discussion

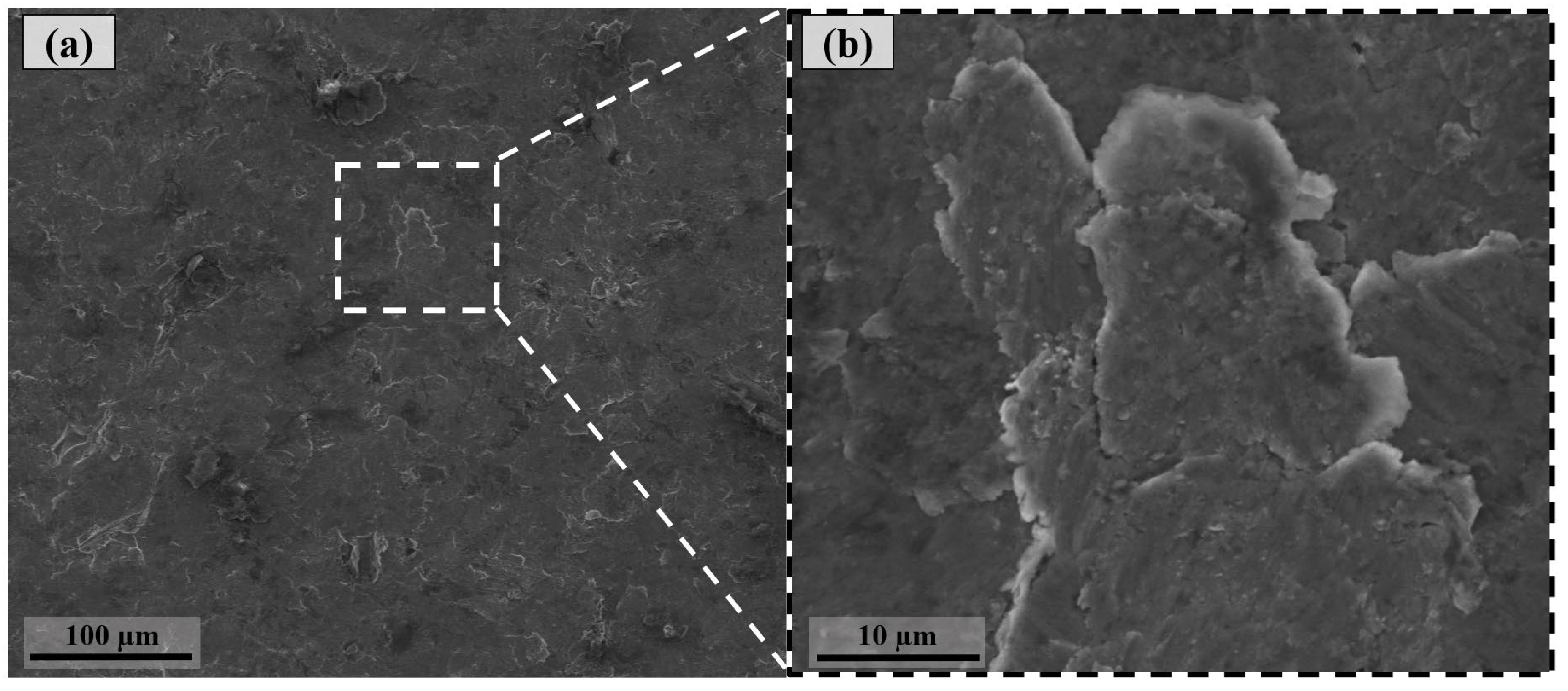

3.1. Surface Morphology After Shot Peening

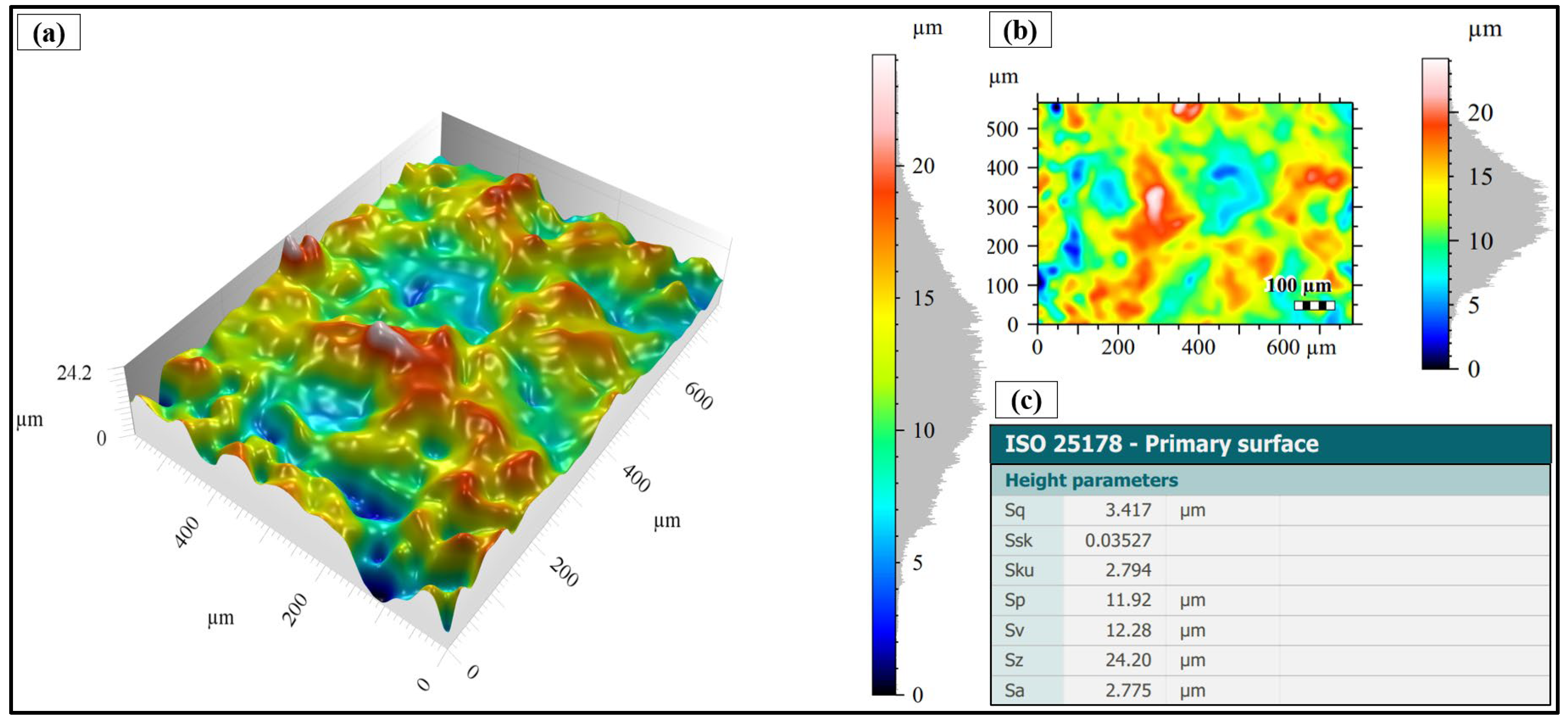

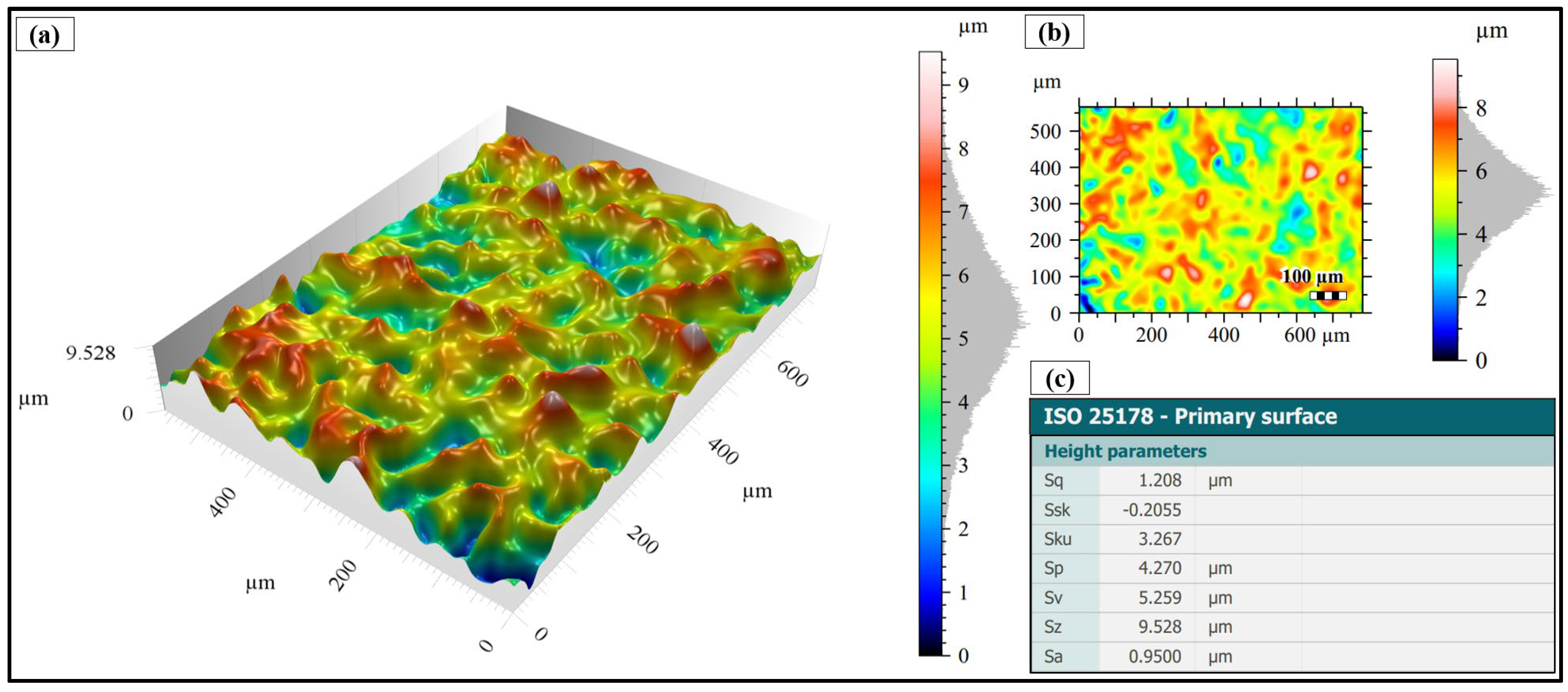

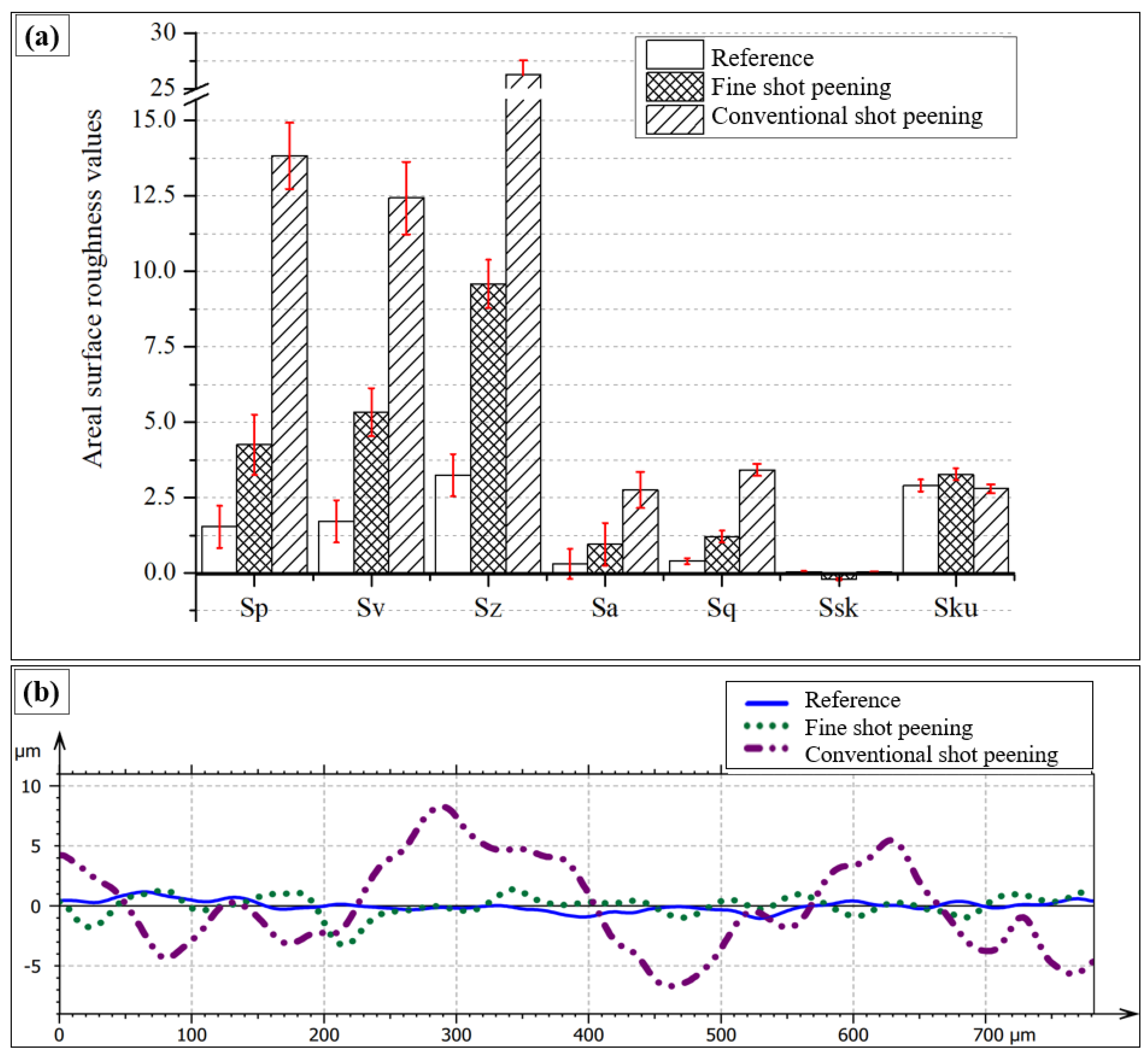

3.2. Surface Topography After Shot Peening

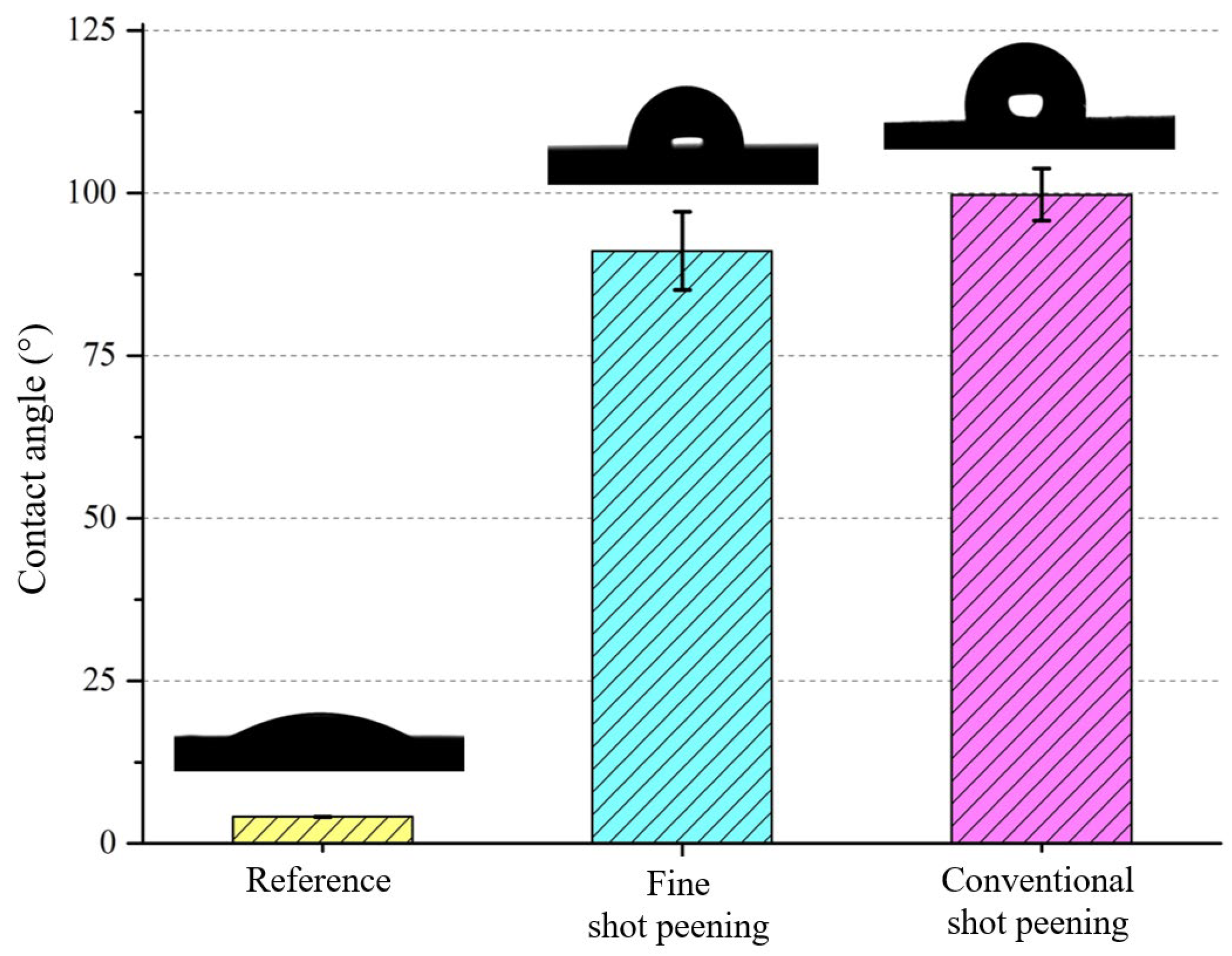

3.3. Wettability After Shot Peening

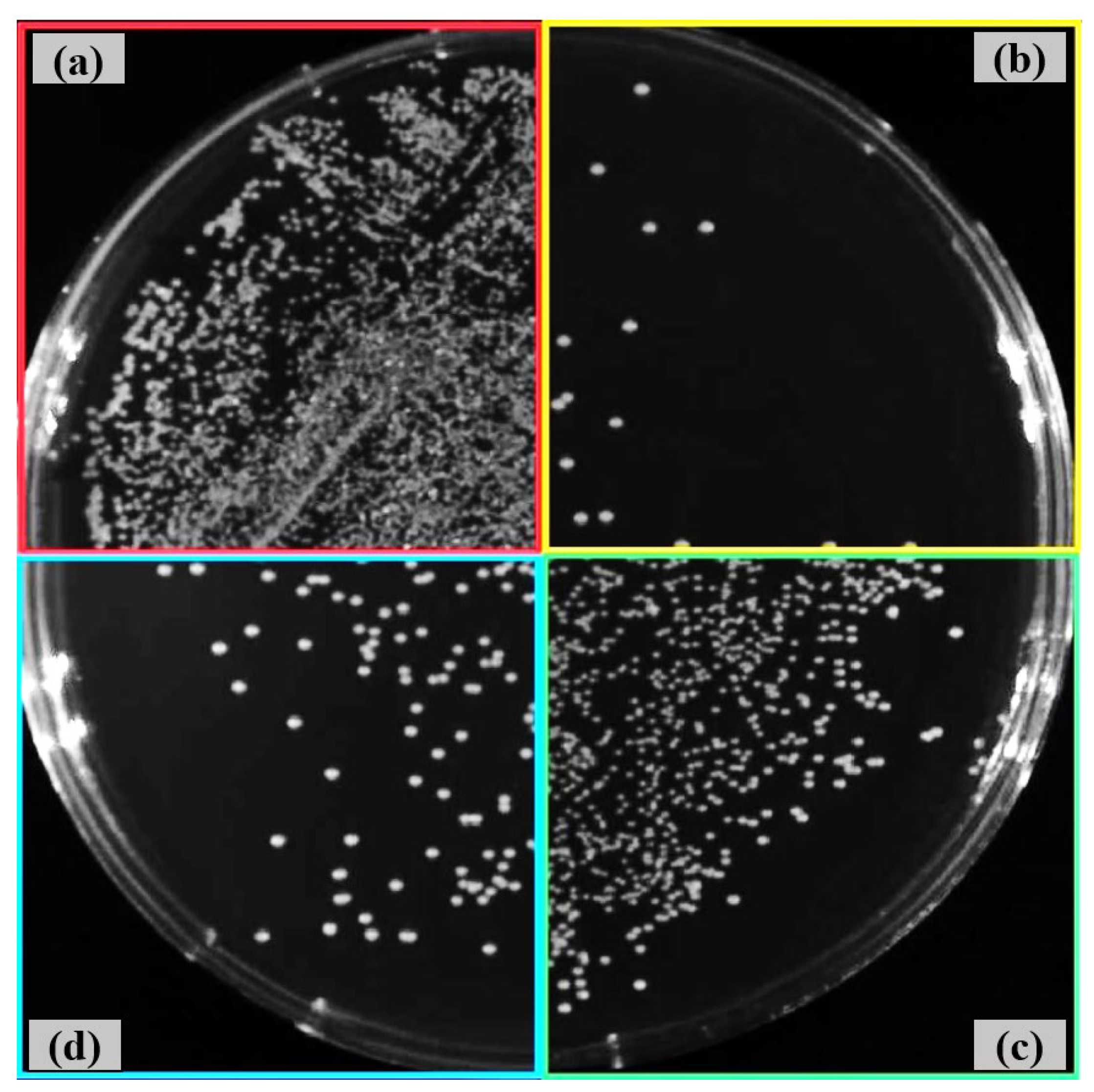

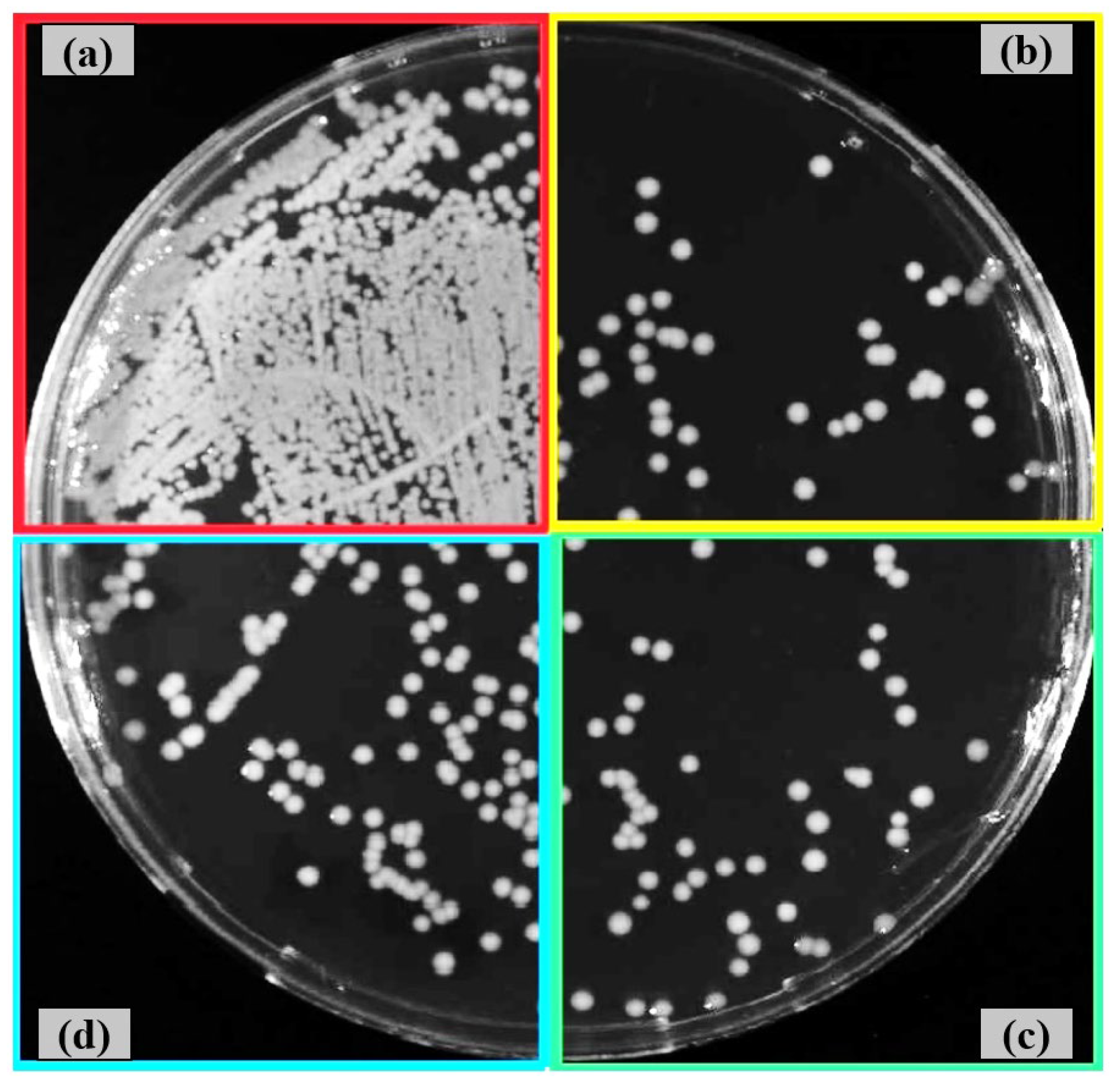

3.4. Antibacterial Activity After Shot Peening

4. Conclusions

- Surface characteristics were strongly influenced by shot size and energy. Conventional shot peening (700–1000 µm) induced rougher, irregular surfaces with higher peak-valley features (Sa ≈ 2.78 µm), while fine shot peening (100–200 µm) produced more homogeneous textures with smoother topographies (Sa ≈ 1.69 µm), minimizing potential surface damage.

- Wettability shifted from hydrophilic to hydrophobic after peening, with fine shot peening achieving a contact angle of ~91° and conventional peening exceeding 99°. These changes are attributed to the formation of micro-dimples and hierarchical textures, which reduce solid–liquid interaction and may favor antibacterial behavior.

- Both shot peening techniques largely preserved the intrinsic antibacterial activity of the Ti6Al4V alloy, with some strain-specific variation. The smoother fine-peened surfaces may offer an improved balance between reduced bacterial adhesion and topographical suitability for biomedical integration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shivakoti I., K.G., Cep R., Pradhan B. B., Sharma A. Laser Surface Texturing for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Coatings 2021.

- Sandoval-Robles J. A., R.C.A., García-López E. Laser Surface Texturing and Electropolishing of CoCr and Ti6Al4V-ELI Alloys for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2020.

- Lin N., L. D., Zou J., Xie R., Wang Z., Tang B. Surface Texture-Based Surface Treatments on Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloys for Tribological and Biological Applications: A Mini Review. Materials 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., L.Y., Li X., Dong G. Pulse Laser-İnduced Cell-Like Texture On Surface Of Titanium Alloy For Tribological Properties İmprovement. Wear 2021.

- Shen X., S. P., Nath S., Lawrence J. Improvement in Mechanical Properties of Titanium Alloy (Ti-6Al-7Nb) Subject to Multiple Laser Shock Peening. Surf. Coat. 2017, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Abakay, E.; Armağan, M.; Yıldıran Avcu, Y.; Guney, M.; Yousif, B.F.; Avcu, E. Advances in improving tribological performance of titanium alloys and titanium matrix composites for biomedical applications: a critical review. Front. Mater. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedikoğlu M., K.A., Tutuş H., Toker S. M. Current Approaches in Surface Processing of Biomedical Alloys; Laser Processes. J. Sci. 2021, 413-431.

- Günther D., S.D., Hess R., Wolf-Brandstetter C., Grosse Holthaus M., Lasagni A.F. High Precision Patterning of Biomaterials Using the Direct Laser İnterference Patterning Technology. Laser Surf. Modif. Biomater. 2016.

- Niemann, R.; Hahn, S.; Diestel, A.; Backen, A.; Schultz, L.; Nielsch, K.; Wagner, M.F.X.; Fähler, S. Reducing the nucleation barrier in magnetocaloric Heusler alloys by nanoindentation. APL Mater. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Hu, S.; Yao, C.; Dong, B.; Ma, C.; Lu, L.; Chen, J. Bioinspired femtosecond laser surface texturing for enhancing tribological properties of Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Tribol. Int. 2026, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hu, J.; Yu, Z.; Pan, J. Effect of pulsed laser biomimetic patterns on surface properties and cell migration of titanium alloys. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Xiang, J.; Zou, X.; Zou, S. Effect of laser shock peening on the surface integrity and fretting fatigue properties of high-strength titanium alloy TC21. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 4533–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puoza, J.C. Research progress of surface texturing and thermal diffusion technology to improve tribological properties of materials. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlcak, P.; Fojt, J.; Koller, J.; Drahokoupil, J.; Smola, V. Surface pre-treatments of Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta beta titanium alloy: The effect of chemical, electrochemical and ion sputter etching on morphology, residual stress, corrosion stability and the MG-63 cell response. Results Phys. 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, R.; Fleischer, M.; Kern, D.P. An anisotropic dry etch process with fluorine chemistry to create well-defined titanium surfaces for biomedical studies. Microelectron. Eng. 2012, 97, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J. Effects of water-guided laser surface strengthening on surface properties and fatigue life of TC4 titanium alloy in tension-tension fatigue tests. Vacuum 2025, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Aissa, C.; Khlifi, K. CAE-PVD synthesis and characterization of titanium-based biocompatible coatings deposited on titanium alloy for biomedical application. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 42, A10–A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M. Enhancing biomedical applications of Ti–6Al–4V alloys: The role of boron nitride and titanium diboride coatings in mechanical and radiation shielding performance. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, M.; Atapour, M.; Ashrafizadeh, F.; Elmkhah, H.; di Confiengo, G.G.; Ferraris, S.; Perero, S.; Cardu, M.; Spriano, S. Nanostructured multilayer CAE-PVD coatings based on transition metal nitrides on Ti6Al4V alloy for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 23367–23382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milles S., D.J., Soldera M., Lasagni A.F. Stable Superhydrophobic Aluminum Surfaces Based on Laser-Fabricated Hierarchical Textures. Materials 2021.

- Yao J., W.Y., Wu G., Sun M., Wang M., Zhang Q. Growth Characteristics and Properties of Micro-Arc Oxidation Coating on SLM-Produced TC4 Alloy for Biomedical Applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 727-737.

- Avcu, Y.Y.; Iakovakis, E.; Guney, M.; Çalım, E.; Özkılınç, A.; Abakay, E.; Sönmez, F.; Koç, F.G.; Yamanoğlu, R.; Cengiz, A.; et al. Surface and Tribological Properties of Powder Metallurgical Cp-Ti Titanium Alloy Modified by Shot Peening. Coatings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcu, E.; Abakay, E.; Yıldıran Avcu, Y.; Çalım, E.; Gökalp, İ.; Iakovakis, E.; Koç, F.G.; Yamanoglu, R.; Akıncı, A.; Guney, M. Corrosion Behavior of Shot-Peened Ti6Al4V Alloy Produced via Pressure-Assisted Sintering. Coatings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiran Avcu, Y.; Yetik, O.; Guney, M.; Iakovakis, E.; Sinmazcelik, T.; Avcu, E. Surface, Subsurface and Tribological Properties of Ti6Al4V Alloy Shot Peened under Different Parameters. Mater. (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žagar, S.a.J.G. Surface Modification Analysis after Shot Peening of AA 7075 in Different States. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tini, S.C.; Zeren, A.; Avcu, Y.Y.; Abakay, E.; Iakovakis, E.; Sınmazçelik, T.; Guney, M.; Avcu, E. Effect of shot peening on the cavitation erosion of manganese aluminium bronze alloy: Microstructural and morphological insights. Mater. Lett. 2025, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Q., L.H., Zhu C., Chen D., Zhou S. Effects of Different Shot Peening Parameters on Residual Stress, Surface Roughness and Cell Size. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020.

- Avcu, Y.Y.; Gonul, B.; Yetik, O.; Sonmez, F.; Cengiz, A.; Guney, M.; Avcu, E. Modification of Surface and Subsurface Properties of AA1050 Alloy by Shot Peening. Mater. (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.M.; Guo, J.W.; Zhuang, J.P.; Jing, Y.B.; Shao, Z.K.; Jin, M.S.; Zhang, J.; Wei, D.Q.; Zhou, Y. Development and characterization of MAO bioactive ceramic coating grown on micro-patterned Ti6Al4V alloy surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 299, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhai, J. Influence of process parameters of ultrasonic shot peening on surface roughness and hydrophilicity of pure titanium. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 317, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, V.K.S.; Shih, M.-H.; Wu, H.-C.; Wu, T.-I. Comparative Study of Surface Modification Techniques for Enhancing Biocompatibility of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy in Dental Implants. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uanlee, T.; Khantachawana, A. Effect of fine shot peening on physical and biological properties of SUS316L and Ti-6Al-4V for medical applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th Biomedical Engineering International Conference (BMEiCON), 31 Aug.-2 Sept. 2017, 2017; pp. 1–4.

- Khandaker, M.; Riahinezhad, S.; Sultana, F.; Vaughan, M.B.; Knight, J.; Morris, T.L. Peen treatment on a titanium implant: effect of roughness, osteoblast cell functions, and bonding with bone cement. Int J Nanomed. 2016, 11, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Hu, W.; Ping, L.; Liu, C.; Yao, L.; Deng, Z.; Wu, G. Antibacterial and Osteogenic Functionalization of Titanium With Silicon/Copper-Doped High-Energy Shot Peening-Assisted Micro-Arc Oxidation Technique. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 573464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Ren, J.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Liu, H.; Cao, F.; Sun, Q. Copper powder ultrasonic shot peening and its application in antifouling of Ti alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; You, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Lou, C. Enhanced mechanical properties and antimicrobial performance of TC4 titanium alloy via surface nanocrystallization and gas nitriding. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2025, 20, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linjee, S.; Bumrungpon, M.; Newyawong, P.; Wutikhun, T.; Songkuea, S.; Muengto, S.; Tange, M.; Suwanpreecha, C.; Manonukul, A. On the severe shot peening effect to generate nanocrystalline surface towards enhancing fatigue life of injection-moulded Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 15513–15528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S.; Fernandez-Pariente, I.; Ghelichi, R.; Guagliano, M. Effect of severe shot peening on microstructure and fatigue strength of cast iron. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 65, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Cheng, J.-h.; Guan, H.-j.; Tan, W.-j.; Zhang, Y.-h. Investigation of wet shot peening on microstructural evolution and tensile-tensile fatigue properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Duan, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Si, C. Effect of ultrasonic shot peening on microstructure evolution and corrosion resistance of selective laser melted Ti–6Al–4V alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, T.; Masuda, K.; Mimura, S.; Hirokawa, T.; Ishiguro, H.; Kumagai, M.; Ito, T. Antibacterial effect on microscale rough surface formed by fine particle bombarding. AMB Express 2022, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, T.; Hirokawa, T.; Ishiguro, H.; Ito, T. Mechanism of antibacterial property of micro scale rough surface formed by fine-particle bombarding. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2024, 25, 2376522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.K.; Pandey, V.; Barhanpurkar-Naik, A.; Wani, M.R.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Singh, V. Effect of ultrasonic shot peening duration on microstructure, corrosion behavior and cell response of cp-Ti. Ultrasonics 2020, 104, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcu, E.; Yıldıran Avcu, Y.; Baştan, F.E.; Rehman, M.A.U.; Üstel, F.; Boccaccini, A.R. Tailoring the surface characteristics of electrophoretically deposited chitosan-based bioactive glass composite coatings on titanium implants via grit blasting. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 123, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, J.; Ansheed, A.R.; Hameed, P.; Praveenkumar, K.; Pilz, S.; Andrea Alberta, L.; Swaroop, S.; Calin, M.; Gebert, A.; Manivasagam, G. Insights into the surface and biocompatibility aspects of laser shock peened Ti-22Nb alloy for orthopedic implant applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Shadangi, Y.; Bhatnagar, A.; Singh, V.; Chattopadhyay, K. Influence of Surface Nano-Structuring on Microstructure, Corrosion Behavior and Osteoblast Response of Commercially Pure Titanium Treated Through Ultrasonic Shot Peening. Jom 2022, 74, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S.; Hickey, D.J.; de Luca, A.C.; Malheiro, V.N.; Markaki, A.E.; Guagliano, M.; Webster, T.J. The influence of nanostructured features on bacterial adhesion and bone cell functions on severely shot peened 316L stainless steel. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, C.P.; Keerthi Krishnan, K.; Sudeep, U.; Ramachandran, K.K. Osteogenic and antibacterial properties of TiN-Ag coated Ti-6Al-4V bioimplants with polished and laser textured surface topography. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Noguchi, S.; Mitake, K.; Kurosaka, S.; Doi, K.; Harada, H. Surface modification of low-alloy steels by fine particle peening using combination of iron sulfide and spring steel particles. Mater. Lett. 2025, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesue, S.; Morita, T.; Misaka, Y.; Komotori, J. Rapid formation of titanium nitride coating by atmospheric-controlled induction-heating fine particle peening and investigation of its wear and corrosion resistance. Results Surf. Interfaces 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Z.Y.; Truong, V.K.; Murdoch, B.J.; Elbourne, A.; Caruso, R.A. Inherent variation in surface roughness of Selective Laser Melting (SLM) printed titanium caused by build angle changes the mechanomicrobiocidal effectiveness of nanostructures. J Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 696, 137866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Deng, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Ji, V. Study on surface characteristics and wear resistance of PBF-LB Ti-6Al-4V alloy treated by shot peening. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasubramanian, J.; Upadhyay, P.; Mallik, A.; Basu, A. Electrochemical corrosion behaviour of electrodeposited nickel coating subjected to ultrasonic shot peening treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ruiz, P.; Garcia-Blanco, M.B.; Vara, G.; Fernández-Pariente, I.; Guagliano, M.; Bagherifard, S. Obtaining tailored surface characteristics by combining shot peening and electropolishing on 316L stainless steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 492, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina-Perez, M.C.; Rivas, A.; Martinez, A.; Rodrigo, D. Antimicrobial potential of macro and microalgae against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms in food. Food Chem 2017, 235, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, A.; Elie, A.-M.; Plawinski, L.; Serro, A.P.; Botelho do Rego, A.M.; Almeida, A.; Urdaci, M.C.; Durrieu, M.-C.; Vilar, R. Femtosecond laser surface texturing of titanium as a method to reduce the adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus and biofilm formation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 360, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.K.; Lapovok, R.; Estrin, Y.S.; Rundell, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Fluke, C.J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. The influence of nano-scale surface roughness on bacterial adhesion to ultrafine-grained titanium. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3674–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Hays, M.P.; Hardwidge, P.R.; Kim, J. Surface characteristics influencing bacterial adhesion to polymeric substrates. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14254–14261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, R.; Fernandes, D.; Wood, J.; Palms, D.; Burzava, A.; Ninan, N.; Brown, T.; Barker, D.; Vasilev, K. Long-term antibacterial properties of a nanostructured titanium alloy surface: An in vitro study. Mater Today Bio 2022, 13, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño-Barris, G.; Camps-Font, O.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. The Influence of Implantoplasty on Surface Roughness, Biofilm Formation, and Biocompatibility of Titanium Implants: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Altenried, S.; Zogg, A.; Zuber, F.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Ren, Q. Role of the Surface Nanoscale Roughness of Stainless Steel on Bacterial Adhesion and Microcolony Formation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6456–6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical Composition (wt. %) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V | Al | Fe | Sn | Si | Ti |

| 2.769 | 5.629 | 0.089 | 0.006 | 0.052 | 91.455 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Shot type | Stainless steel shots |

| Shot hardness | 460 HV |

| Shot size | 100-200 µm (Fine shot peening) |

| 700-1000 µm (Conventional shot peening) | |

| Acceleration pressure | 5 bar |

| Duration | 2.5 min |

| Standoff distance | 40 mm |

| Nozzle diameter | 4.76 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).