1. Introduction

Cancer is not a monolithic disease but rather a dynamic and adaptive ecosystem characterized by complex interactions among genetically and phenotypically diverse cell populations. Within the tumor microenvironment, cancer cells compete for limited resources such as oxygen, nutrients, and physical space, while simultaneously engaging in cooperative behaviors that enhance survival and proliferation. This intricate interplay between competition and cooperation mirrors the strategic interactions observed in biological systems governed by evolutionary principles. Evolutionary game theory (EGT), originally developed to model strategic behavior in populations of interacting individuals, has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for understanding tumor dynamics. By conceptualizing tumor cells as rational agents making fitness-maximizing decisions under selective pressures, EGT enables researchers to analyze how cellular strategies evolve over time, leading to tumor progression, heterogeneity, and therapeutic resistance. This paper explores the application of evolutionary game theory to model tumor growth, competition, and cooperation, and discusses how these insights can inform more effective cancer treatment strategies.

Evolutionary game theory, an extension of classical game theory introduced by John Maynard Smith and George R. Price in the 1970s, provides a formal approach to studying how strategies evolve in populations through natural selection [

1]. Unlike classical game theory, which focuses on rational decision-making by individual agents, EGT examines the frequency-dependent success of strategies within a population. A strategy’s fitness—its reproductive success—depends not only on the strategy itself but also on the distribution of other strategies in the population. This frequency dependence is particularly relevant in cancer, where the success of a particular cell type (e.g., a fast-proliferating or invasive phenotype) depends on the composition of the surrounding tumor cell population.

In the context of cancer, tumor cells can be viewed as players in a game where the payoff is reproductive fitness—measured by proliferation rate, survival, and metastatic potential. Different phenotypic strategies, such as high proliferation, resource conservation, motility, or resistance to therapy, can be modeled as distinct strategies in an evolutionary game. For example, proliferative cells may outcompete slower-growing cells in nutrient-rich environments, but in hypoxic or resource-limited conditions, cells that adopt a quiescent or stress-resistant phenotype may gain a fitness advantage [

2]. The tumor microenvironment thus acts as a dynamic game board, with changing payoffs based on spatial constraints, immune surveillance, and therapeutic interventions.

One of the most influential applications of EGT in oncology is the "War of Attrition" model, which explains the coexistence of multiple cell types within a tumor. In this model, aggressive and cooperative strategies can stably coexist because the fitness of each strategy depends on its frequency in the population. For instance, "cheater" cells that exploit resources without contributing to collective functions (e.g., angiogenesis) may thrive when rare but suffer reduced fitness when common, due to the collapse of cooperative mechanisms [

3]. This frequency-dependent selection helps explain tumor heterogeneity and the persistence of non-aggressive cell types even in advanced cancers.

A key insight from EGT is that cooperation among tumor cells—once thought to be counterintuitive in a competitive environment—can be evolutionarily stable under certain conditions. Cancer cells often engage in cooperative behaviors such as the production of growth factors, extracellular matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis. These public goods benefit all cells in the vicinity, including non-producers, creating a social dilemma akin to the "tragedy of the commons" [

4]. However, EGT models show that cooperation can persist through mechanisms such as spatial structure, kin selection, or enforcement of fairness [

5].

For example, in glioblastoma, tumor cells produce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to stimulate blood vessel formation. Cells that do not produce VEGF ("free riders") benefit from the resulting vascularization without paying the metabolic cost. However, if too many cells adopt the free-rider strategy, angiogenesis fails, leading to tumor collapse. EGT models incorporating spatial structure demonstrate that clustering of producer cells can protect cooperative strategies from invasion by cheaters, allowing stable coexistence [

6]. This has important implications for anti-angiogenic therapies, which may inadvertently select for non-producing, more aggressive cell types.

Another illustrative example is the "Go vs. Grow" game, which models the trade-off between cell motility (invasion and metastasis) and proliferation. Cells that invest in motility ("Go" strategy) may escape local competition but reproduce more slowly, while "Grow" cells prioritize division but remain vulnerable to resource depletion. EGT analyses reveal that the optimal strategy depends on environmental conditions: in dense, resource-limited tumors, motility may be favored, whereas in sparse environments, proliferation dominates [

7]. This dynamic helps explain the emergence of metastatic subclones and suggests that therapies targeting one strategy may inadvertently promote the other.

The application of evolutionary game theory to cancer biology offers transformative insights for treatment design. Traditional therapies often aim to eradicate as many tumor cells as possible, but this approach can impose strong selective pressures that favor resistant or aggressive clones—a phenomenon known as "competitive release." EGT provides a framework for anticipating such evolutionary responses and designing adaptive therapies that manage rather than maximize cell kill.

Adaptive therapy, inspired by EGT principles, seeks to maintain a stable tumor burden by allowing sensitive cells to persist and suppress resistant ones through competitive interactions. In prostate cancer, for example, intermittent androgen deprivation therapy has been shown to prolong time to progression compared to continuous treatment, as sensitive cells outcompete resistant ones in the absence of therapy [

8]. Mathematical models based on EGT have guided the optimization of drug scheduling to maintain this competitive balance, demonstrating the clinical potential of evolutionary-informed strategies.

Furthermore, EGT can inform combination therapies that exploit evolutionary trade-offs. For instance, drugs that induce a "Grow" phenotype may sensitize tumors to anti-motility agents, or vice versa. Similarly, therapies that disrupt cooperative mechanisms—such as inhibitors of public goods production—can destabilize tumor ecosystems and reduce overall fitness [

9]. These approaches move beyond static targeting of molecular pathways toward dynamic management of tumor evolution.

Despite its promise, the application of EGT in oncology faces challenges. Accurate modeling requires detailed knowledge of payoff structures, which are context-dependent and difficult to measure in vivo. Additionally, tumor ecosystems involve interactions with stromal cells, immune cells, and the extracellular matrix, complicating the definition of players and strategies. Future research should integrate EGT with multi-omics data, spatial transcriptomics, and agent-based modeling to build more comprehensive and predictive frameworks.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Basics of Game Theory

Game theory is a mathematical framework used to model and analyze situations in which multiple decision-makers—referred to as “players”—interact with one another, each seeking to maximize their own outcomes, or “payoffs.” While traditionally developed in economics and political science, game theory has become an increasingly influential tool in biology, especially in the study of evolutionary dynamics. In cancer biology, the framework of game theory provides a valuable lens through which the complex, adaptive, and often competitive interactions between tumor cells can be analyzed and interpreted.

In a game-theoretic model, the fundamental components include players, strategies, and payoffs. In the context of tumor biology, the players are typically individual cells or groups of cells with distinct phenotypic characteristics. These can include variations in growth rate, metabolism, motility, or resistance to therapeutic agents. Each of these traits can be considered a type of “strategy” that a cell adopts to survive and replicate in its microenvironment.

Strategies in this context refer to the behavioral or physiological traits that determine how a cell interacts with its environment and with neighboring cells. For instance, some cancer cells may adopt highly proliferative strategies, rapidly dividing to dominate spatial niches. Others may prioritize migratory behavior, enabling them to invade surrounding tissues or metastasize to distant organs. Still others may engage in cooperative strategies, such as the secretion of growth factors that benefit not just the producer cell but also nearby cells. These cooperative strategies often resemble phenomena modeled in evolutionary game theory, such as the Public Goods game. Conversely, some cells may adopt “cheating” strategies, exploiting the shared benefits provided by other cells without incurring the metabolic costs of production themselves.

Payoffs represent the reproductive success or survival advantage a particular strategy provides. In biological terms, this could be quantified as the rate of cell division, the likelihood of avoiding immune detection, or the ability to resist chemotherapy. Importantly, the payoff to any given strategy is not fixed but depends on the strategies adopted by other players in the population. This frequency-dependent selection means that the success of one phenotype often depends on the presence or absence of competing phenotypes within the tumor microenvironment.

A classic example is the Hawk-Dove game, adapted from behavioral ecology, which models interactions between aggressive (Hawk-like) and non-aggressive (Dove-like) cells. When two Hawks meet, they incur a high cost due to conflict, potentially representing energy depletion or immune activation. When a Hawk meets a Dove, the Hawk gains the full benefit with no cost, while the Dove gains nothing. When two Doves meet, they share the resource without conflict. Over time, the system may reach an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS)—a population mix that resists invasion by alternative strategies. In a tumor, such dynamics may explain the coexistence of aggressive and non-aggressive clones, or the cycling of dominant phenotypes over time.

Another key concept in evolutionary game theory is that interactions are non-zero-sum; that is, the gain of one player does not always result in an equal loss for another. In tumors, this is particularly relevant because some strategies (like the secretion of angiogenic factors or immunosuppressive cytokines) can raise the overall fitness of multiple clones, at least temporarily. This leads to the emergence of complex and sometimes counterintuitive outcomes, such as the proliferation of otherwise weak clones that benefit from a niche created by more robust or cooperative ones.

2.2. Tumor Heterogeneity and Evolution

One of the defining features of cancer is its intra-tumor heterogeneity—the existence of genetically and phenotypically distinct cell populations within the same tumor mass. This diversity arises from a combination of genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations, microenvironmental variability, and stochastic factors influencing gene expression. Tumor heterogeneity presents a major challenge for both understanding cancer progression and designing effective therapies, as different cell subpopulations may respond differently to treatment or engage in distinct modes of interaction with the host environment.

The evolutionary nature of cancer is now widely recognized. Tumors evolve through a process akin to Darwinian selection, wherein individual clones acquire mutations and traits that confer varying levels of fitness. Under selective pressures—including hypoxia, nutrient scarcity, immune surveillance, and pharmacological interventions—subpopulations that adapt most effectively are preferentially expanded. This process is not merely passive but is shaped by active interactions among different cell types, including both cancerous and non-cancerous cells within the tumor microenvironment.

Game theory becomes especially relevant in this context because it allows for the modeling of strategic interactions among heterogeneous tumor cell populations. Each subclone can be considered a player in an evolutionary game, competing or cooperating with others for access to limited resources and favorable conditions. For example, one subpopulation might secrete extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes that enable invasion, inadvertently benefiting neighboring cells that do not produce these enzymes. This sets up a public goods dynamic in which producers and free-riders coexist, potentially destabilizing the tumor ecology if one group outcompetes the other.

Moreover, spatial heterogeneity within tumors adds another layer of complexity. Cells at the tumor core often experience different microenvironmental conditions than those at the invasive edge. The resulting gradients in oxygen, pH, immune activity, and drug penetration influence the selection pressures acting on different clones. Spatially explicit game-theoretic models can account for such variation, allowing for more accurate simulations of tumor evolution and therapeutic response.

An important insight from game theory is that heterogeneous populations may be more stable than homogeneous ones, particularly when interactions lead to negative frequency-dependent selection. That is, a strategy that is advantageous when rare may become less so when it becomes common, thereby maintaining diversity. This explains, in part, why tumors often do not converge toward a single dominant clone, but instead maintain a dynamic equilibrium among multiple competing strategies.

This evolutionary heterogeneity also has significant implications for treatment resistance. Traditional therapies often target the most proliferative clones, but in doing so, they may inadvertently select for resistant subpopulations. These resistant cells, though initially rare, can expand rapidly once their competitors are removed—a classic case of ecological release. Game-theoretic approaches propose alternative strategies such as adaptive therapy, where the goal is to manage rather than eliminate the tumor, maintaining a balance among sensitive and resistant populations to prevent dominance by any one group.

3. Game-Theoretic Models in Tumor Biology

Tumor progression is not merely a product of unregulated proliferation but rather the consequence of complex ecological and evolutionary interactions among diverse cellular subpopulations. These interactions can often be understood through the lens of evolutionary game theory, which models the strategic behavior of players (here, tumor cell phenotypes) competing over limited resources. Several classic game-theoretic models—originally developed in evolutionary biology and economics—have been adapted to cancer research to explain phenomena such as cooperation, competition, and resistance. This section explores three such models: the Hawk-Dove game, Public Goods games, and the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and discusses their biological interpretations and implications for tumor growth and treatment resistance.

3.1. Hawk-Dove Game

The Hawk–Dove game describes a competitive scenario in which two distinct types of individuals—or, in the context of oncology, two distinct tumor cell phenotypes—compete for access to a shared and limited resource. The framework was originally introduced in ethology to explain animal conflict behaviors, but it has since been adapted to cancer biology to explore how aggressive and non-aggressive tumor cell types can coexist within the same microenvironment.

In the oncological interpretation of the model, “Hawk” cells correspond to highly invasive and aggressive phenotypes. These cells pursue a confrontational strategy, directly competing for nutrients, oxygen, and physical space. Their behavior is often characterized by elevated motility, secretion of proteolytic enzymes capable of degrading the extracellular matrix, and rapid proliferation rates. By contrast, “Dove” cells represent less aggressive phenotypes that avoid direct confrontation. Rather than investing energy in fighting for resources, they tend to adopt a more conservative growth strategy, which may involve slower proliferation and prioritization of metabolic efficiency over rapid expansion.

The outcome of interactions between these phenotypes depends on the relative benefit of securing the contested resource, denoted by

B, and the cost of engaging in aggressive conflict, denoted by

C. When two Hawk cells encounter each other, both engage in a costly fight, each having an equal chance of winning; the expected payoff for each in this case is

When a Hawk cell competes with a Dove cell, the Hawk secures the resource unopposed, gaining the full benefit

B, while the Dove receives nothing. When two Dove cells meet, they avoid conflict entirely, sharing the resource equally, resulting in a payoff of

for each.

Applied to tumor ecology, the Hawk–Dove model predicts that the dominance of one phenotype over the other is not inevitable. Instead, the system tends toward an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), a stable proportion of Hawks and Doves that cannot be invaded by a small number of mutants adopting a different strategy. The precise composition of this ESS depends critically on the relationship between the benefit of resource acquisition and the cost of aggression. When the cost C is sufficiently high relative to B, the system favors the persistence or even dominance of Dove-like cells, since aggressive behavior becomes too costly to sustain. Conversely, when the benefit B greatly exceeds the cost C, aggressive Hawk phenotypes may predominate. In intermediate regimes, a dynamic balance emerges in which both phenotypes coexist, each maintained in the population by the evolutionary pressures generated by the other.

To formalize this, let

p denote the proportion of Hawks in the population, so that

is the proportion of Doves. The average payoff for a Hawk,

, and for a Dove,

, are given by

The mean fitness of the population is

Under replicator dynamics, the change in the proportion of Hawks is governed by

At equilibrium,

, which occurs either when

(all Doves),

(all Hawks), or when

. Setting

gives

This corresponds to the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), representing the equilibrium fraction of aggressive (Hawk) phenotypes in the tumor cell population. For , we have , meaning that Hawks and Doves coexist. For , the equilibrium suggests a predominance of Hawks, while for , Doves dominate.

3.1.1. Biological Implications

In the context of cancer progression, Hawk and Dove phenotypes can have markedly different implications for tumor behavior and patient prognosis. Hawk-like tumor cells, with their heightened motility and invasive potential, are more prone to migrate away from the primary tumor mass, infiltrate surrounding tissues, and establish colonies in distant organs—a process central to metastasis. By contrast, Dove-like cells tend to remain within the primary site, contributing primarily to the maintenance and expansion of the local tumor mass rather than initiating secondary growths elsewhere in the body.

The distinction between these phenotypes also extends to therapeutic resistance. Aggressive, Hawk-like cells often display a greater capacity to withstand treatment, whether through intrinsic resistance mechanisms, such as upregulated drug efflux pumps or enhanced DNA repair, or through adaptive changes induced by the treatment itself. This resilience means that therapies aimed at eliminating aggressive clones may, paradoxically, create ecological space for less aggressive Doves to flourish. In some cases, these surviving Doves can subsequently repopulate the tumor, contributing to relapse after an initial treatment response.

Spatial structure within the tumor further shapes the balance between these phenotypes. In peripheral tumor regions, where access to healthy tissue facilitates invasion and escape into circulation, Hawks often dominate due to the selective advantage of their invasive traits. In contrast, Doves may persist in the central core of the tumor, where cell density is high, competition is intense, and cooperative sharing of limited resources offers a survival advantage.

Understanding the dynamics between these two strategies is crucial for designing effective therapeutic interventions. By deliberately altering the tumor microenvironment—such as increasing immune-mediated clearance of invasive cells or manipulating nutrient availability—it may be possible to shift the cost–benefit balance in ways that make aggressive behavior less advantageous. In doing so, oncologists could encourage the persistence of less invasive phenotypes, potentially slowing disease progression and reducing the risk of metastasis.

3.2. Public Goods Games

The Public Goods game captures scenarios in which individuals invest resources into a shared pool that benefits all members of the community, regardless of their personal contribution. In tumor biology, this framework is especially relevant to understanding cooperative behaviors among cancer cells, such as the secretion of diffusible growth factors, pro-angiogenic molecules like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), or immunosuppressive cytokines that modulate the tumor microenvironment to favor cancer survival. These products act as “public goods” in the sense that they diffuse through the local environment, conferring benefits on both producers and non-producers alike.

Within this setting, one can distinguish between two functional strategies. Cells adopting a cooperative phenotype actively produce the public good, enhancing the growth and survival of neighboring cells as well as their own. However, this contribution comes at a metabolic or energetic cost, diverting resources from other vital processes such as proliferation or stress resistance. In contrast, “cheater” cells abstain from producing the public good, yet still enjoy the advantages provided by nearby cooperators. By avoiding the energetic expense of production, cheaters can allocate more resources toward their own replication and survival, potentially outcompeting cooperators in the short term.

This tension between cooperative investment and selfish exploitation creates a complex evolutionary landscape within the tumor. If cooperators become too rare, the overall availability of the public good may drop below the threshold needed to sustain rapid tumor growth, harming both strategies. Conversely, if cooperators are sufficiently abundant, cheaters may proliferate disproportionately, exploiting the benefits without bearing the costs. The resulting dynamics can lead to fluctuating proportions of cooperators and cheaters over time, shaped by local resource availability, spatial structure, and selective pressures from the host environment. In some cases, spatial clustering of cooperators can stabilize cooperation by preferentially conferring benefits on other cooperators, thereby reducing the relative success of cheaters.

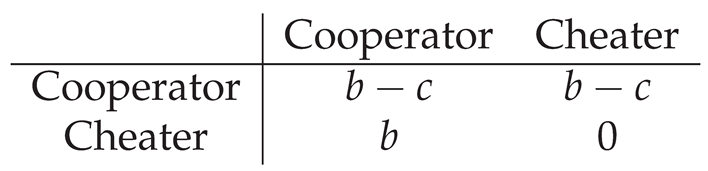

The interaction can be formalized as follows. Let

c denote the cost of producing the public good,

b the per-capita benefit received by each individual from a single cooperator, and

n the group size. If there are

k cooperators in the group (including the focal individual if it is a cooperator), the total benefit is

, shared among all group members. The payoff to a cooperator is therefore

while the payoff to a cheater (defector) is

For a simple two-player version of the game, the payoff matrix is in

Table 1.

In a well-mixed population where the fraction of cooperators is

p, the expected payoffs become

Under replicator dynamics, the change in the proportion of cooperators is

In the classic, one-shot well-mixed public goods game, whenever , meaning that cheaters always have a selective advantage. This captures the fundamental cooperation problem: without additional mechanisms such as spatial structure, repeated interactions, or punishment, cooperation cannot persist. In tumors, however, microenvironmental constraints and spatial clustering can alter the effective payoff structure, making cooperation evolutionarily viable.

Understanding these public goods dynamics in tumors offers potential therapeutic insights. By targeting the production or diffusion of key public goods, it may be possible to undermine the cooperative infrastructure that supports malignant growth. Alternatively, manipulating the tumor microenvironment to increase the metabolic burden of public good production could tilt the balance toward less cooperative—and potentially less resilient—cell populations.

4. Evolutionary Game Theory Model: A Glycolytic vs. Oxidative Tumor Cell Case Study

In this study, we focus on a specific example of tumor heterogeneity involving two primary metabolic phenotypes:

glycolytic (G) cells, which preferentially use anaerobic glycolysis even under normoxic conditions (the Warburg effect), and

oxidative (O) cells, which rely on oxidative phosphorylation [

10,

11,

12]. Glycolytic cells excrete lactic acid, lowering extracellular pH and creating an acidic tumor microenvironment. This acidity can impair oxidative cells but imposes an energetic cost on glycolytic cells due to their lower ATP yield per glucose molecule. Conversely, oxidative cells are more energy-efficient but are more vulnerable to acid-mediated cytotoxicity.

We model the tumor as a well-mixed population of n distinct phenotypes (strategies), indexed by . In our case study, :

Let

be the proportion of phenotype

i in the population, satisfying:

4.0.1. Payoff Matrix for the Glycolytic–Oxidative Game

The interactions between phenotypes are quantified by a

payoff matrix , where

is the fitness payoff to phenotype

i when interacting with phenotype

j. Based on the parameterization from

12, a representative payoff matrix is:

where:

: payoff for a glycolytic cell interacting with another glycolytic cell (acidic environment, lower ATP efficiency).

: payoff for a glycolytic cell interacting with an oxidative cell (acidic advantage over opponent).

: payoff for an oxidative cell interacting with a glycolytic cell (acid-sensitive disadvantage).

: payoff for an oxidative cell interacting with another oxidative cell (neutral pH, optimal energy production).

4.0.2. Fitness Function

Given

A and the current composition

, the fitness of phenotype

i is:

Here, represents the effective reproductive success of glycolytic cells, while corresponds to oxidative cells.

4.0.3. Replicator Dynamics

The average fitness of the population is:

The replicator equation, which governs the change in frequency of phenotype

i, is:

where

is given by Equation (

16).

For our two-strategy system, we only need to track

(since

). The dynamics reduce to:

4.0.4. Interpretation in Tumor Cell Growth

This formalism captures the essential evolutionary competition between glycolytic and oxidative cells:

If glycolytic cells have a higher relative payoff than the population average (), they will expand in proportion, potentially leading to an acidic and more aggressive tumor environment.

If oxidative cells gain higher payoffs (e.g., through pH buffering therapies), they may outcompete glycolytic cells.

Stable coexistence occurs when , which defines an internal equilibrium point in .

This payoff-based framework naturally leads into the numerical simulation in

Section 5, where we integrate Equation (

19) over time for different initial tumor compositions and therapeutic scenarios.

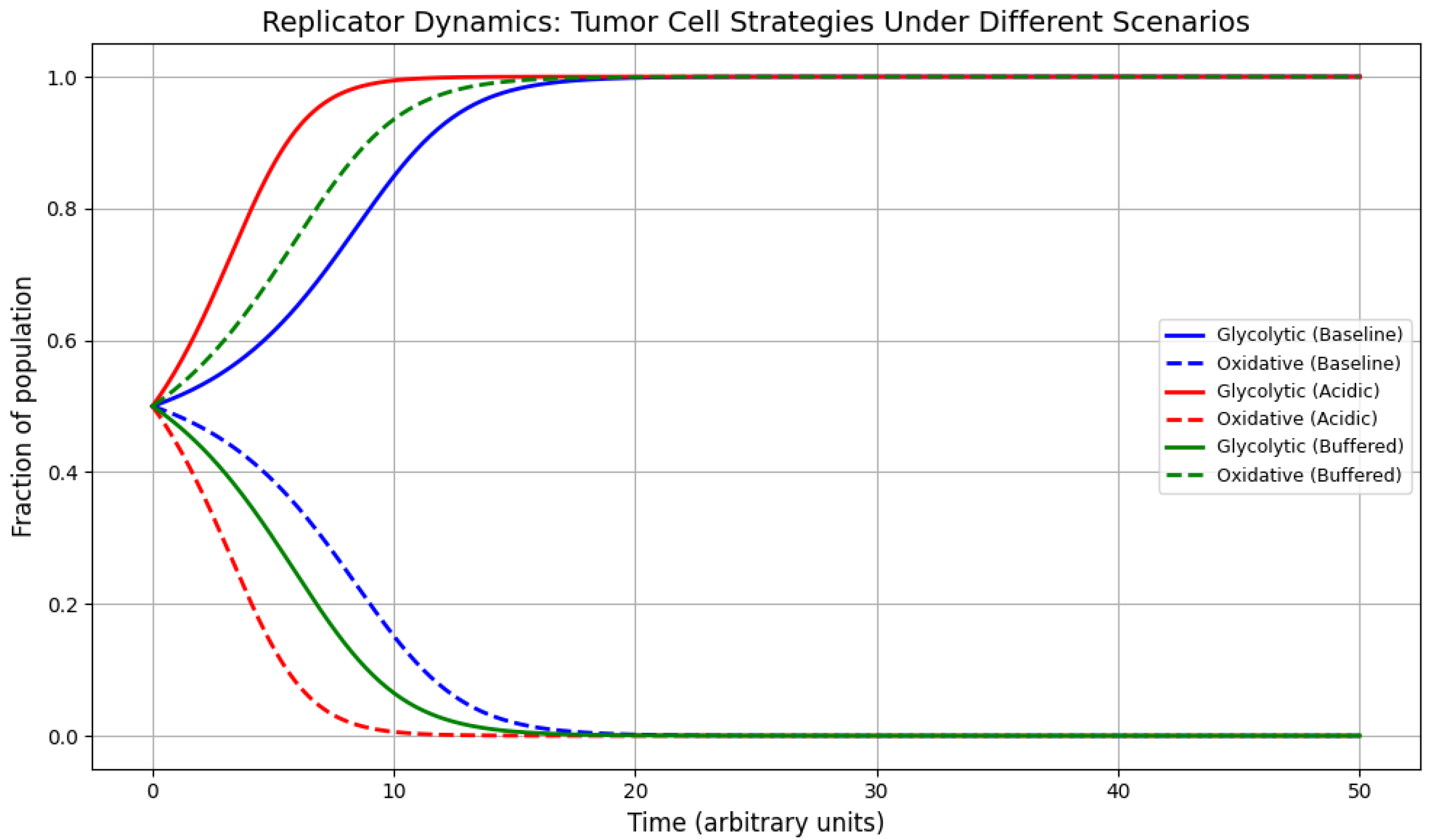

5. Numerical Simulation and Interpretation

To explore the evolutionary dynamics of glycolytic (G) and oxidative (O) tumor cell populations under different microenvironmental conditions, we numerically integrated the replicator dynamics (Equation

19) using three distinct payoff matrices. The simulations were performed with an initial condition of

and

, over a time span of

(arbitrary units). The parameters for each scenario are as follows:

-

Baseline scenario (Kim et al. [

13]):

This matrix represents the standard competitive balance between glycolytic and oxidative cells, with moderate acid-induced disadvantage for oxidative cells and moderate metabolic inefficiency for glycolytic cells.

-

Acidic microenvironment scenario:

Here, glycolytic cells gain an increased payoff when interacting with both phenotypes, while oxidative cells incur a greater penalty when facing glycolytic cells. This models a tumor microenvironment with stronger acid-mediated cytotoxicity and/or nutrient competition.

-

pH-buffered therapy scenario:

In this case, the negative impact of acidity on oxidative cells is reduced, possibly through therapeutic interventions such as systemic bicarbonate administration [

11]. This scenario tests whether altering the microenvironment can shift the competitive balance in favor of oxidative metabolism.

5.1. Simulation Results

Figure 1 shows the time evolution of the fractions

and

under each scenario. Several qualitative patterns emerge:

Baseline: The two phenotypes evolve towards a stable coexistence equilibrium. Glycolytic cells initially gain a slight advantage due to their acidification strategy, but oxidative cells retain a non-zero fraction owing to their higher efficiency in non-acidic interactions. This equilibrium composition is consistent with experimental observations of mixed metabolic phenotypes in many tumors [

13].

Acidic microenvironment: Glycolytic cells rapidly dominate the population, driving oxidative cells to near extinction. This reflects a scenario where extracellular pH is significantly reduced, strongly favoring acid-resistant phenotypes. Such an outcome is associated with increased tumor aggressiveness, invasiveness, and metastatic potential [

11,

12].

pH-buffered therapy: Oxidative cells increase in relative abundance compared to the baseline case, sometimes approaching majority composition. The equilibrium is shifted toward a more balanced or even oxidative-dominated population. This supports the hypothesis that microenvironmental interventions can reduce the fitness advantage of glycolytic phenotypes, potentially slowing tumor progression and altering therapeutic response.

5.2. Biological Interpretation

These simulations illustrate how small changes in the payoff matrix—representing altered metabolic costs, resource access, or microenvironmental conditions—can lead to qualitatively different tumor evolutionary trajectories. In the context of evolutionary game theory, such parameter shifts change the location and stability of equilibria in the replicator dynamics.

From a clinical perspective:

Acidic conditions push the evolutionary game towards glycolytic dominance, which is generally associated with more malignant phenotypes and poorer patient outcomes.

Buffering the tumor microenvironment can reverse or mitigate this trend, increasing the prevalence of oxidative cells and possibly rendering tumors more susceptible to conventional therapies.

The framework demonstrates that tumor evolution is not fixed but can be strategically perturbed through environmental modification, aligning with the concept of

evolutionary therapy [

15].

These results provide a quantitative, model-based rationale for combining metabolic or pH-modifying interventions with existing treatment regimens to reshape the evolutionary game being played within the tumor.

Table 2 summarizes the equilibrium fractions of glycolytic (G) and oxidative (O) tumor cells obtained from the replicator dynamics simulations under three distinct scenarios. Each equilibrium corresponds to a stable state of the system in which the relative proportions of phenotypes no longer change over time. These values result directly from the payoff matrix parameters, which encode the competitive advantages and disadvantages of each metabolic strategy in a given microenvironment.

In the baseline scenario, glycolytic and oxidative cells coexist in equal proportions (, ), indicating a balanced fitness landscape where neither metabolic phenotype dominates. This equilibrium reflects a tumor ecosystem in which both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation contribute comparably to cellular reproduction and survival.

The acidic microenvironment scenario produces a dramatic shift toward near-complete glycolytic dominance (), with oxidative cells nearly eliminated (). This outcome arises because the acidic conditions—often a result of glycolytic lactate production—create a strong selective advantage for glycolytic phenotypes, which are better adapted to low pH, while penalizing oxidative metabolism. Such dominance is associated with more aggressive tumor growth and therapy resistance.

In contrast, the pH-buffered therapy scenario alters the competitive balance, reducing the glycolytic fraction to and increasing oxidative prevalence to . By mitigating extracellular acidity, buffering therapy diminishes the advantage of glycolysis, enabling oxidative cells—often slower-growing and potentially more therapy-sensitive—to gain ground. This suggests that targeted modification of the tumor microenvironment can substantially reshape evolutionary outcomes.

6. Cancer Interpretation

The numerical results obtained from our evolutionary game theory simulations provide a mechanistic understanding of how metabolic heterogeneity in tumors can be shaped by microenvironmental conditions. In the baseline scenario, where the payoff matrix reflects a balanced competition between glycolytic (G) and oxidative (O) cells, the population evolves toward a stable coexistence equilibrium of approximately

and

(

Table 2). This balance aligns with the metabolic diversity often observed in real tumors, where both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation contribute to tumor growth and survival [

14,

15].

In contrast, the acidic microenvironment scenario shifts the equilibrium drastically toward glycolytic dominance (

), driving oxidative cells to near extinction. Biologically, this reflects a tumor niche in which extracellular acidosis, often driven by lactate production from glycolysis, creates a selective landscape that strongly penalizes oxidative metabolism [

11]. This outcome is associated with aggressive phenotypes, enhanced invasiveness, and resistance to certain chemotherapies [

16].

Conversely, the pH-buffered therapy scenario alters the evolutionary trajectory in favor of oxidative cells, leading to an equilibrium of approximately

and

. By reducing the acid-mediated suppression of oxidative phenotypes, buffering interventions weaken the relative fitness advantage of glycolytic cells, allowing oxidative metabolism to recover. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that altering the tumor microenvironment can fundamentally change the "rules" of the evolutionary game being played within the tumor [

17].

7. Therapeutic Applications

The insights derived from this model have direct implications for cancer therapy design. First, the acidic microenvironment scenario highlights a critical vulnerability: aggressive glycolytic tumors are evolutionarily favored under low pH conditions. Therapies that inadvertently exacerbate acidity, such as certain hypoxia-inducing treatments, may unintentionally accelerate glycolytic dominance and worsen patient outcomes. This underscores the importance of considering ecological side effects when designing interventions.

The pH-buffered therapy scenario offers a compelling proof-of-principle for

evolutionary therapy [

17]. By modifying the tumor microenvironment—through systemic buffering agents such as sodium bicarbonate, or through vascular normalization strategies that reduce hypoxia—it may be possible to shift the competitive balance in favor of oxidative phenotypes. Oxidative cells often have slower proliferation rates and may be more susceptible to conventional therapies such as radiotherapy and certain chemotherapeutic agents [

18].

Furthermore, this EGT framework enables predictive therapy planning: clinicians could estimate the payoff matrix for an individual patient’s tumor using metabolic imaging (e.g., FDG-PET for glycolysis, hyperpolarized MRI for oxidative flux) and histological analysis, then simulate treatment scenarios to forecast the likely evolutionary trajectory. Such personalized predictions could guide therapy selection to prevent the emergence of therapy-resistant glycolytic dominance.

Another potential application is in

adaptive therapy, where treatment intensity and modality are modulated over time to maintain a stable, controllable tumor composition rather than attempting total eradication [

19]. The replicator dynamics approach provides a mathematical foundation for designing such schedules, ensuring that no single phenotype achieves unchecked dominance.

8. Conclusions

In this work, we applied evolutionary game theory to model the competition between glycolytic and oxidative tumor cell populations, incorporating numerical simulations under three distinct microenvironmental scenarios. The results reveal that:

Under baseline conditions, glycolytic and oxidative cells coexist at stable proportions.

Increased acidity drives the system toward complete glycolytic dominance, a hallmark of aggressive tumors.

pH-buffering interventions can reverse this trend, increasing oxidative prevalence and potentially enhancing therapeutic susceptibility.

These findings emphasize that tumor evolution is not solely determined by genetic mutations but is profoundly shaped by ecological interactions within the microenvironment. The payoff matrix formalism provides a compact yet powerful way to encode these interactions, and replicator dynamics offer an intuitive description of the resulting evolutionary trajectories.

From a clinical standpoint, the model supports a paradigm shift from purely cytotoxic strategies toward ecological interventions that reshape the tumor fitness landscape. By identifying and targeting the environmental factors that favor aggressive phenotypes, it may be possible to steer tumor evolution toward less harmful equilibria, improving both survival and quality of life for patients.

Future work should extend this framework to include more phenotypes (e.g., therapy-resistant clones), spatial heterogeneity, and stochastic effects, as well as experimental validation of payoff matrices in patient-derived tumor models. Ultimately, integrating EGT models with real-time clinical monitoring could make evolutionary steering a practical tool in oncology.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially sponsored with national funds through the Fundação Nacional para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal-FCT, under projects UIDB/04674/2020 (CIMA). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04674/2020

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maynard Smith, J.; Price, G.R. The logic of animal conflict. Nature 1973, 246, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, I.P.M. Game-theory models of interactions between tumour cells. European Journal of Cancer 1997, 33, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, R.; Axelrod, D.E.; Pienta, K.J. Evolution of cooperation among tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 13474–13479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, M.A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 2006, 314, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, A.M.; Lima, E.A.B.F.; Hormuth, D.A.; McKenna, M.T.; Feng, X.; Ekrut, D.A.; Yankeelov, T.E. Mathematical models of tumor cell proliferation: A review of the literature. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 2018, 18, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadell, C.D.; Foster, K.R.; Xavier, J.B. Emergence of spatial structure in cell groups and the evolution of cooperation. PLoS Computational Biology 2010, 6, e1000716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Silva, A.S.; Gillies, R.J.; Frieden, B.R. Adaptive therapy. Cancer Research 2009, 69, 4894–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archetti, M.; Pienta, K.J. Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2019, 19, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Gawlinski, E.T. The Glycolytic Phenotype in Carcinogenesis and Tumor Invasion: Insights through Mathematical Models. Cancer Research 2003, 63, 3847–3854. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Stolarska, M.A.; Othmer, H.G. The role of the microenvironment in tumor growth and invasion. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2011, 106, 353–379, Epub 2011 Jun 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archetti, M. Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to tumour metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell 2016, 166, 546–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, M.G.V.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrella, V.; Chen, M.; Lloyd, E.; et al. . Acidity Generated by the Tumor Microenvironment Drives Local Invasion. Cancer Research 2013, 73, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.; Vincent, T. Lessons from Applied Ecology: Cancer Control Using an Evolutionary Double Bind. Cancer Research 2009, 69, 7499–7502, Epub 2009 Sep 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.S.; Gillies, R.D.; Gatenby, R.A. Adaptation to Hypoxia and Acidosis in Carcinogenesis and Tumor Progression. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2008, 18, 330–337, Epub 2008 Mar 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enriquez-Navas, P.M.; Wojtkowiak, J.G.; Gatenby, R.A. Application of Evolutionary Principles to Cancer Therapy. Cancer Research 2016, 76, 3136–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).