Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. General Settings of Rodolith Beds at Coiba National Park

3. Results and Discussion

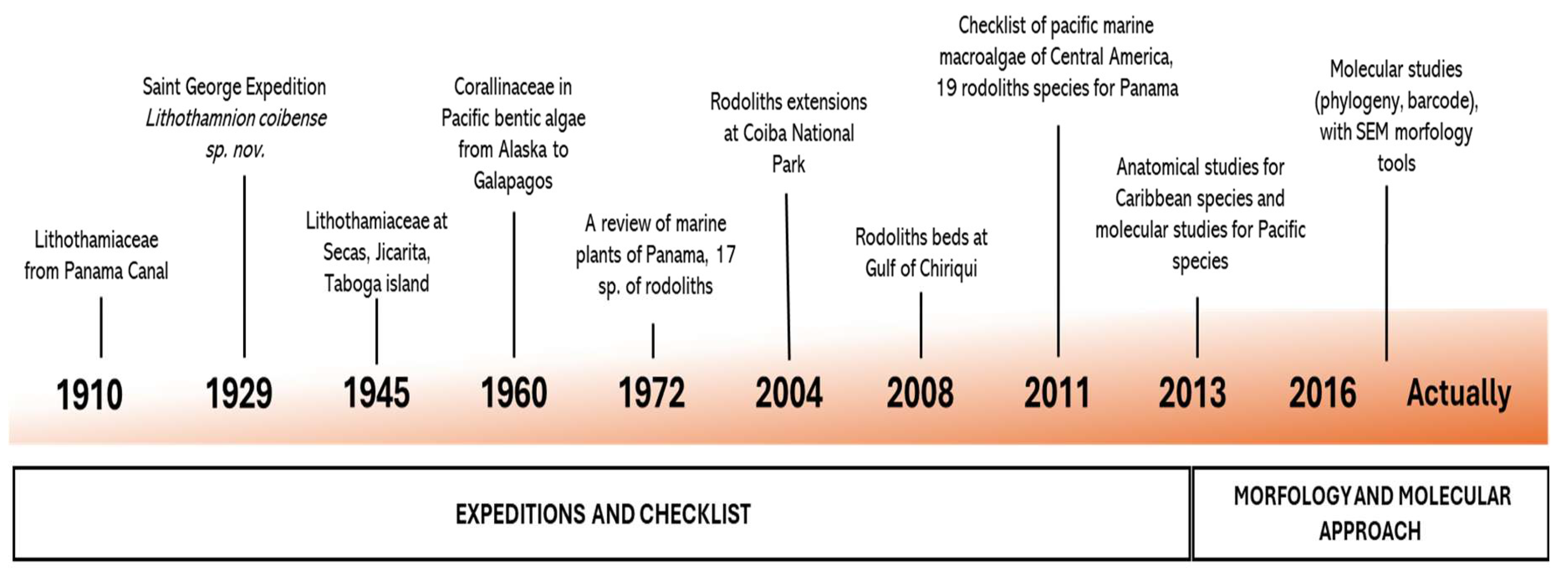

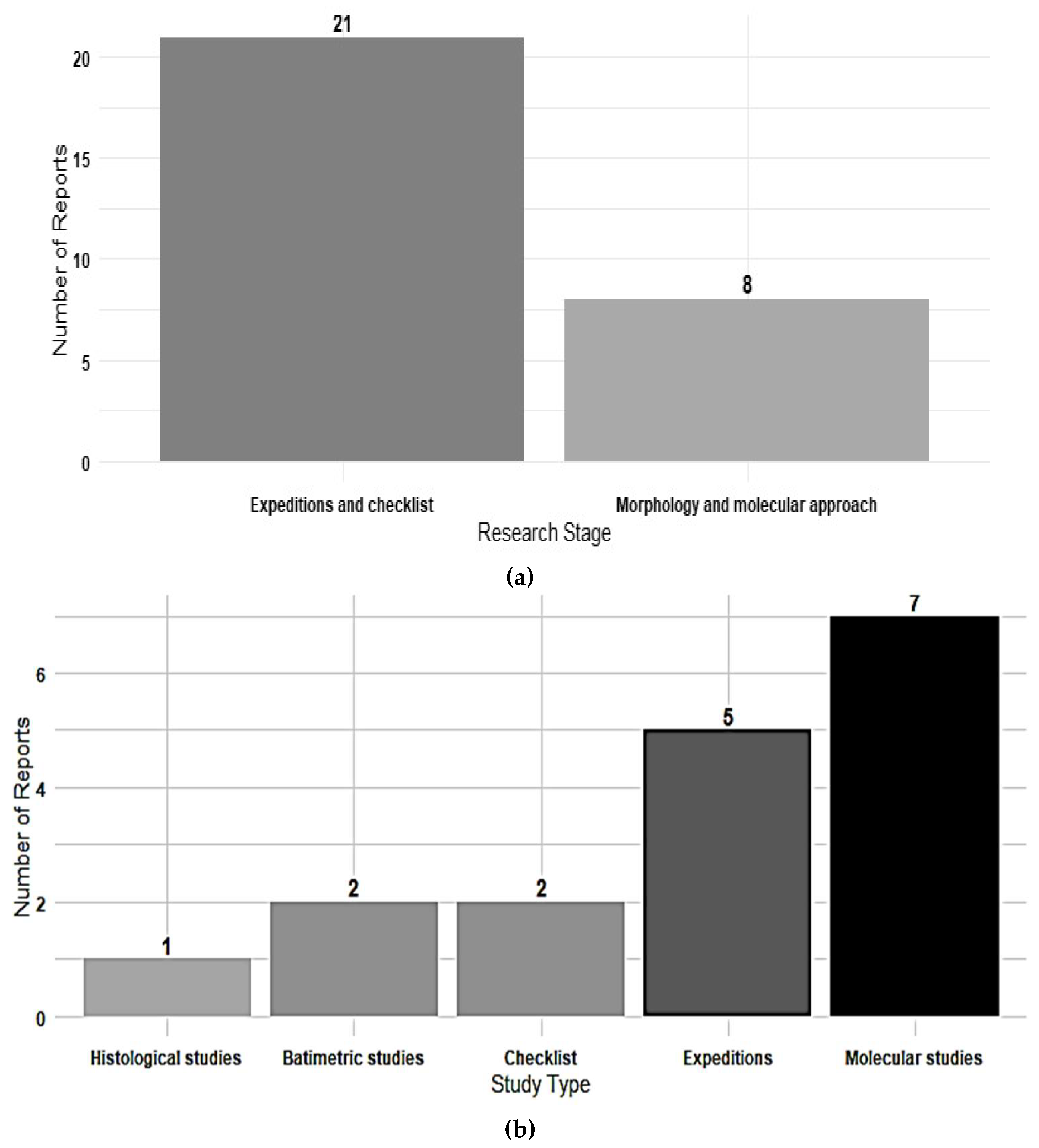

3.1. Historical Review

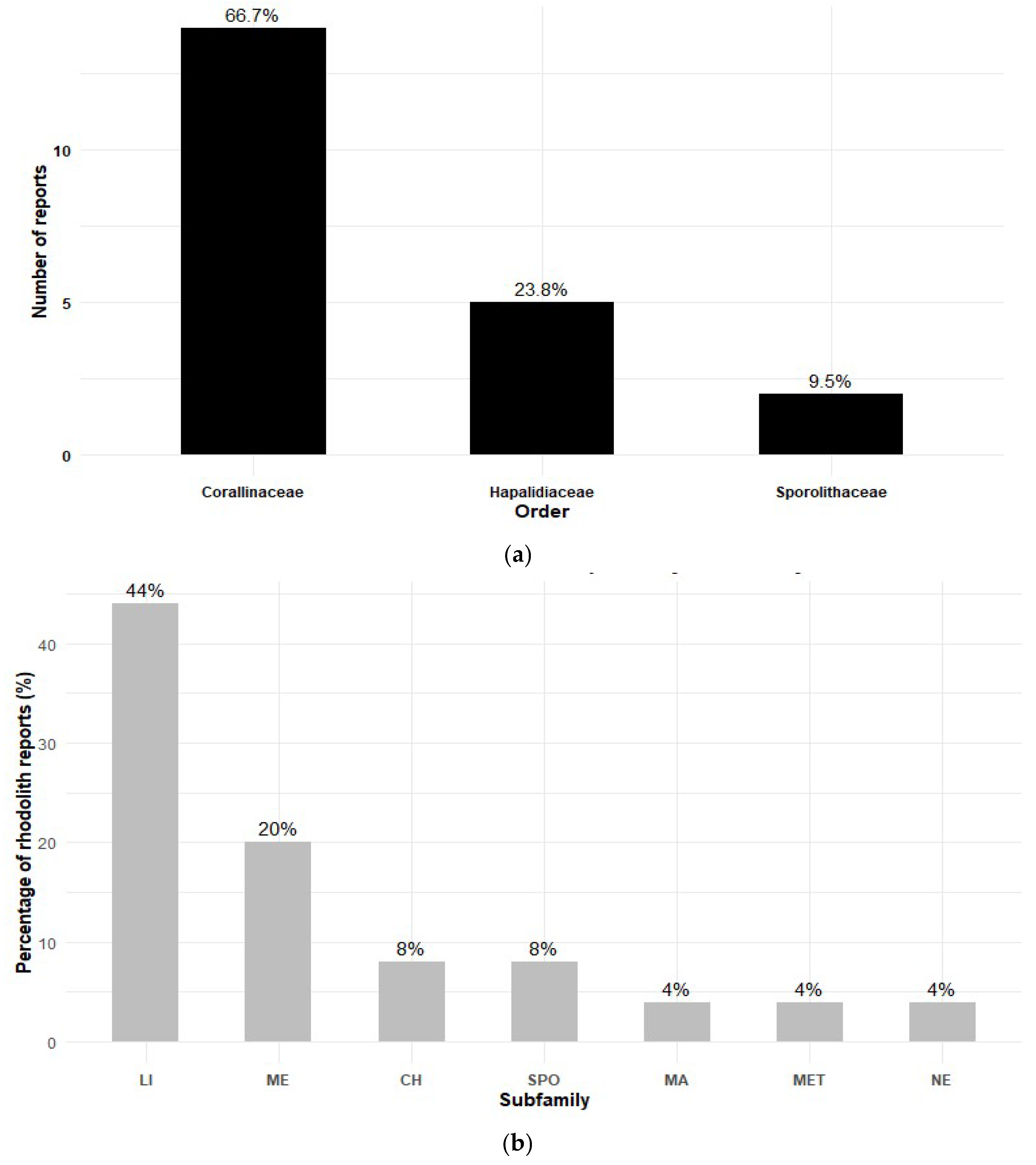

3.2. Checklist of Rhodoliths Species in Panama

3.3. Reports to Be Confirmed

3.4. Misreportings

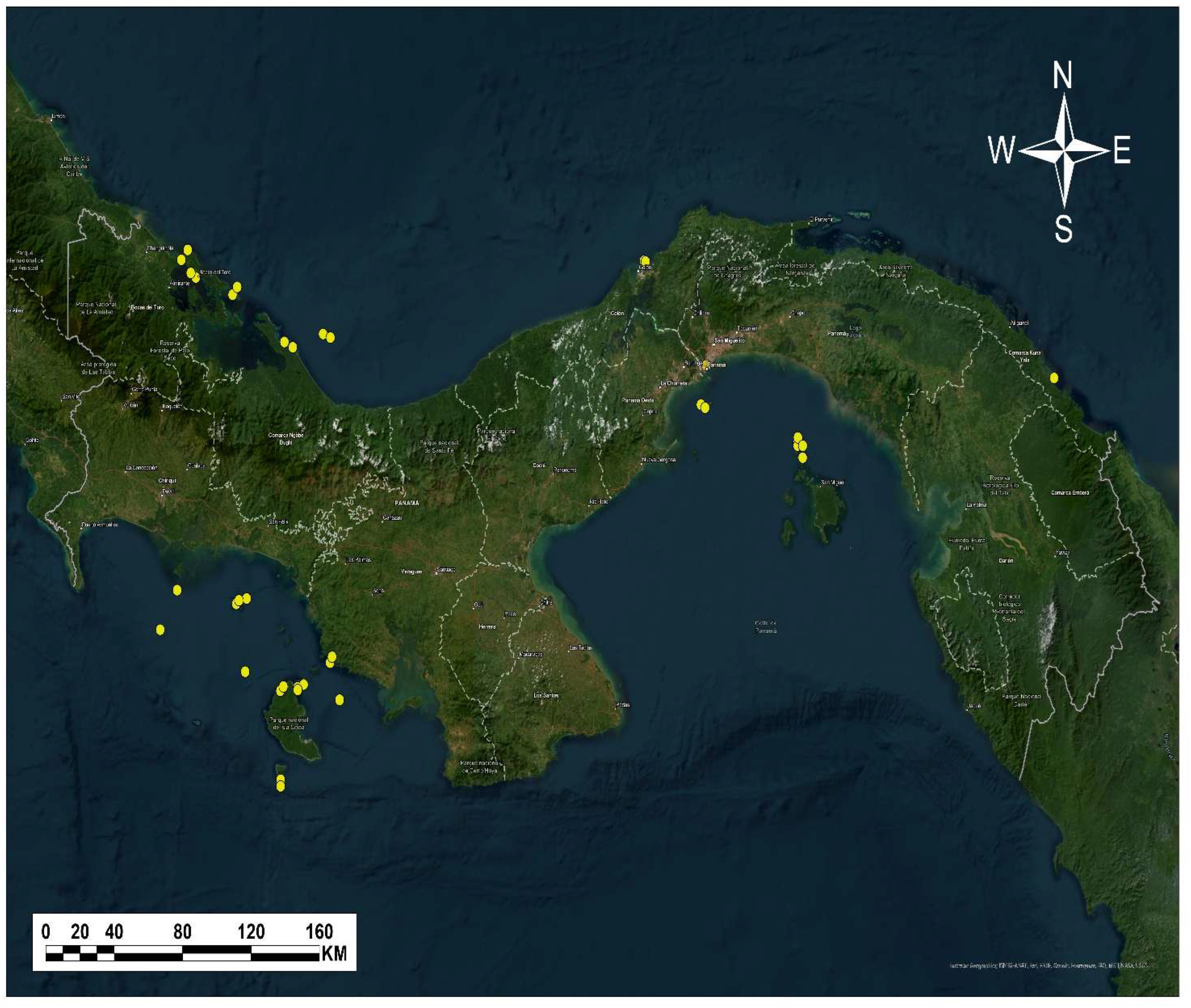

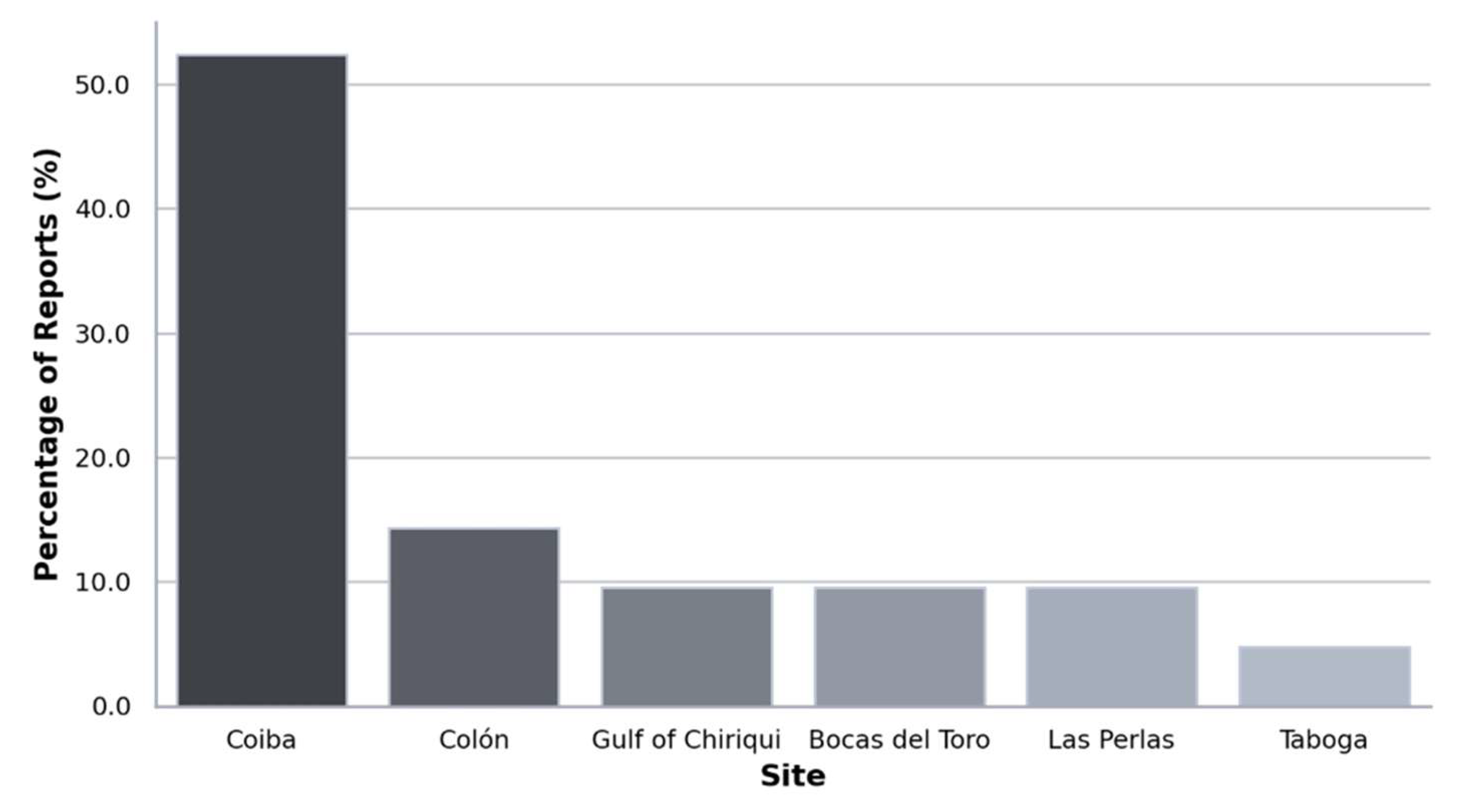

3.5. Localization and Diversity

3.6. Molecular Studies Data

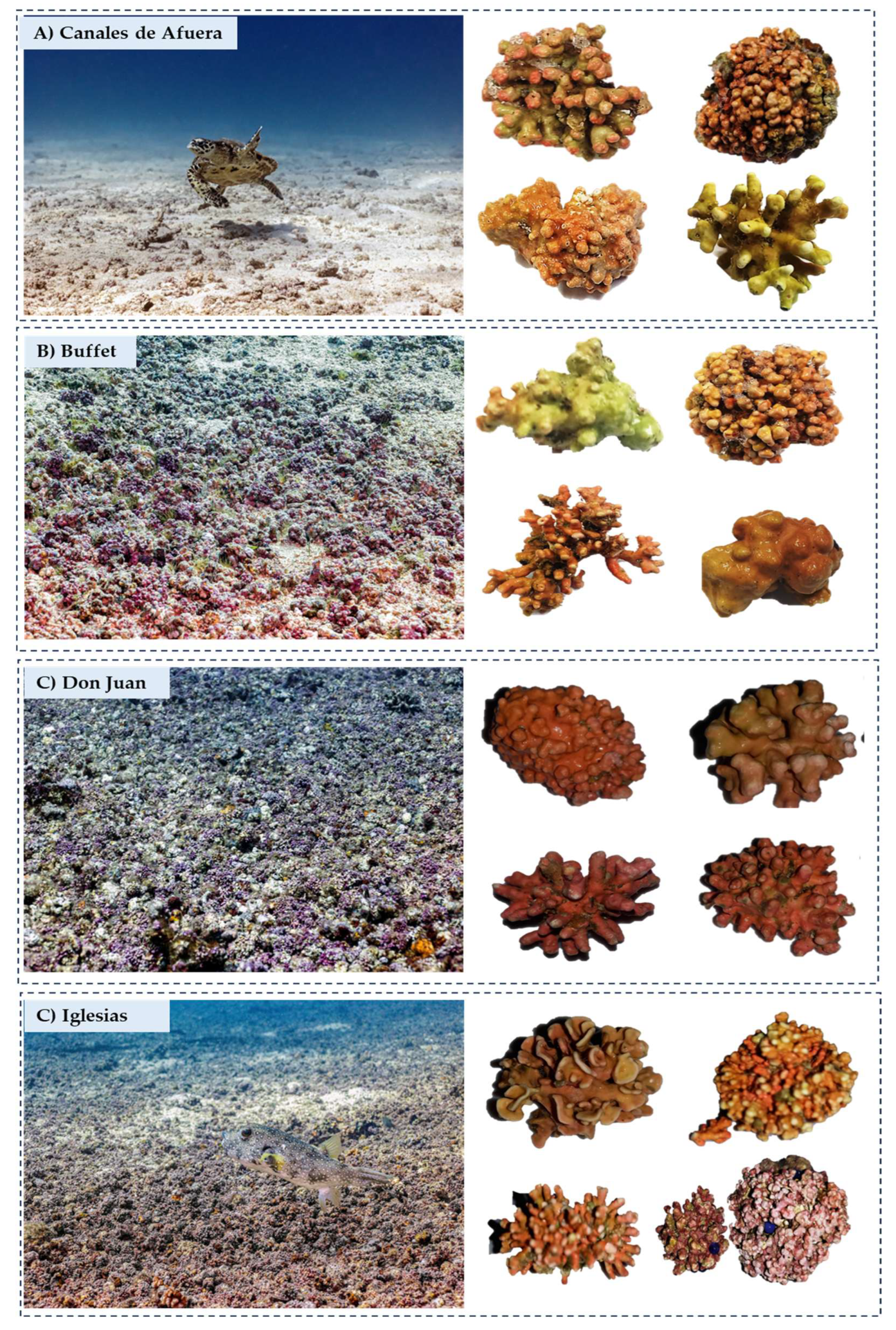

3.7. Rhodolith Beds at Coiba National Park (PNC)

3.8. Ecological Role, Threats and Conservation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PNC | Coiba National Park |

| CMAR | Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor |

| EBSA | Ecologically or Biologically significant Marine Areas |

| SNF | Small Natural Features |

| NE | North East |

Appendix A

| # | Specie | Locality | ID | GenBank Accesion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX2 | LSU | COI | rbcL | UPA | psbA | ||||

| 1 | Harveylithon sp. | Wild Cay, BT | PHYKOS 7053 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | MW452886 |

| 2 | H. munitum | Escudo de Veraguas, BT | PHYKOS_3593 | ---- | MW457636.1 | ---- | MF979962 | ---- | ---- |

| 3 | Lithophyllum sp. | Cebaco Island, VE | LAF7219 | ---- | KJ412333.1 | KJ418417.1 | ---- | ---- | KJ418411.1 |

| 4 | Lithophyllum sp. 3 | Swan Cay, BT | FBCS12912 | KJ801356.1 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 5 | Lithophyllum sp.3 | Sand Fly Bay, BT | FBCS12913 | KJ801357.1 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 6 | Lithothamnion sp. 4 | Swan Cay, BT | FBCS12920 | KJ801364.1 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 7 | Lithothamnion sp. D | Gulf of Chiriqui | LAF6631 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | KU519740 | KU557500 |

| 8 | Lithothmanion 1 | Swan Cay, BT | FBCS12917 | KJ801365.1 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 9 | Lithothmnion sp. J | Tintorera Island, VE | PHYKOS7249 | ---- | KR075891.1 | KU504277 | ---- | KU504275 | KP844865 |

| 10 | L. neocongestum | Bocas del Toro | NCU 598862 | ---- | ---- | ---- | KX020485 | ---- | ---- |

| 11 | L. neocongestum | Bocas del Toro | US223011 | ---- | ---- | ---- | KX020484.1 | ---- | KX020466 |

| 12 | L. neocongestum | Bocas del Toro | US169412 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | KX020486 |

| 13 | L. neocongestum | , Flat Rock Beach, BT | US170968 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | KX020440 |

| 14 | L. neocongestum | Sand Fly Bay, BT | US170967 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | KX020441 |

| 15 | Neogoniolithon sp | Panama | VPF00177 | ---- | ---- | KM392370.1 | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 16 | S. episporum | Punta Toro, Colón | NY_900041 | ---- | ---- | ---- | KY994125.1 | ---- | ---- |

| 17 | S. episporum | Bocas del Toro | NCU_598843 | ---- | ---- | KY994113.1 | KY994124.1 | ---- | MF034547.1 |

| 18 | Sporolithon sp. | Mono Feliz, GC | PHYKOS_4623 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | MF034548.1 |

References

- Riosmena-Rodríguez, R. Chapter 1: Natural History of Rhodolith/Maërl Beds: Their Role in Near-Shore Biodiversity and Management. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 3–26.

- Fredericq, S.; Krayesky, S.; Sauvage, T.; Richards, J.; Kittle, R.; Arakaki, N.; Schmidt, W. The Critical Importance of Rhodoliths in the Life Cycle Completion of Both Macro- and Microalgae, and as Holobionts for the Establishment and Maintenance of Marine Biodiversity. Front. Mar. Sci 2018, 5, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenos, N.; Burdett, H.; Darrenougue, N. Chapter 2: Coralline Algae as Recorders of Past Climatic and Environmental Conditions. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp.27-53.

- Martin, S.; Hall-Spencer, J. Chapter 3: Effects of Ocean Warming and Acidification on Rhodolith/Maërl Beds. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 55–85.

- Ragazzola, F.; Foster, L. C.; Form, A.; Anderson, P. S.; Hansteen, T. H.; Fietzke, J. Ocean acidification weakens the structural integrity of coralline algae. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A. J.; Bates, N. R. .; Mackenzie, F. T. Dissolution of carbonate sediments under rising pCO2 and ocean acidification: observations from Devil’s Hola, Bermuda. Aquat. Geochem. [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. .; Andersson, A.; Mackenzie, F. Initial responses of carbonate-rich shelf sediments to rising atmospheric pCO2 and “ocean acidification”: Role of high Mg-calcites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 5814–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Licona, C.; Schubert, N.; González-Gamboa, V.; Tuya, F.; Azofeifa-Solano, J.; Fernández-García, C. Rhodolith beds in the Eastern Tropical Pacific: Habitat structure and associated biodiversity. Aquat. Bot. 2025, 2025 201, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente. Plan de Manejo del Parque Nacional Coiba 2024. Panamá. https://miambiente.gob.pa/download/plan-de-manejo-del-parque-nacional-coiba-borrador-final-may24/.

- Howe, M. Report on a botanical visit to the Isthmus of Panama. J. N Y Bot. Gard. 1910, 11, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M. On some fossil and recent Lithothamnieae of the Panama Canal Zone. Bull. U.S. Nat. Mus. 1918, 103, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, M. P. Les Corallinacees de l’ Archipel des Galapagos et du Golfe de Panama. Arch. Mus. Hist. Nat. 1929, 6, 47–88. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W. R. Pacific marine algae of the Allan Hancock expeditions to the Galapagos Islands. Allan Hancock Pac. Exp. 1945, 12, 1–528. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, E. New records of marine algae from Pacific Mexico and Central America. Pac. Nat. 1960, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, S. A review of the marine plants of Panama. Bull. Biol. Soc. Wash. 1972, 2, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, H.; Guevara, C.; Breddy, O. Distribution, diversity, and conservation of coral reefs and coral communities in the largest marine protected area of Pacific Panama (Coiba Island). Environ. Conserv. 2004, 31, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littler, M.; Litller, D. Coralline algal rhodoliths form extensive benthic communities in the Gulf of Chiriqui, Pacific Panama. Coral Reefs 2008, 27(3), 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrínez, J. Extensiones de rango y nuevas especies de algas coralinas (Corallinales, Rodophyta) formadoras de mantos de rodolitos en el Caribe. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, La Paz, Mexico, 2013.

- Richards, J.; Vieira-Pinto, T.; Schmidt, W.; Sauvage, T.; Gabrielson, P.; Oliveira, M.; Fredericq, S. Molecular and Morphological Diversity of Lithothamnion spp. (Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta) from Deepwater Rhodolith Beds in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Phytotaxa 2016, 278, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Sauvage, T.; Schmidt, W.; Fredericq, S.; Hughey, J.; Gabrielson, P. The coralline genera Sporolithon and Heydrichia (Sporolithales, Rhodophyta) clarified by sequencing type material of their generitypes and other species. J. Phycol 2017, 53, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Schmidt, W.; Fredericq, S.; Sauvage, T.; Peña, V.; Gall, L. ; Mateo-Cid, L;, Mendoza-González, A.; Hughey, J.; Gabrielson, P. DNA sequencing of type material and newly collected specimens reveals two heterotypic synonyms for Harveylithon munitum (Metagoniolithoideae, Corallinales, Rhodophyta) and three new species. J. Phycol. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Kittle, R.; Schmidt, W.; Sauvage, T.; Gurgel, C.; Gabriel, D.; Fredericq, S. Assessment of Rhodolith Diversity in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico Including the Description of Sporolithon gracile sp. nov. (Sporolithales, Rhodophyta), and Three New Species of Roseolithon (Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, E. Y. A guide to the literature and distributions of Pacific benthic algae from Alaska to the Galapagos Islands. Pac. Sci. 1961, 15, 370–461. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-García, C.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Wysor, B.; Tejeda O., L.; Cortés, J. Checklist of the Pacific marine macroalgae of Central America. Bot. Mar. 2011, 2011. 54, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W. Caribbean Marine Algae of the Allan Hancock Expedition, Rep. Allan Hancock Atlant. Exped. 1939, 2, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Kantun, J.; Gabrielson, P.; Hughey, J.; Pezzolesi, L.; Rindi, F.; Robinson, N.; Peña, V.; Riosmena-Rodriguez, R.; Gall, L.; Adey, W. Reassessment of branched Lithophyllum spp. (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) in the Caribbean Sea with global implications. Phycolog. 2016, 55, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W. Marine Algae of the Eastern Tropical and Subtropical Coasts of the Americas. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1960, pp. 870.

- Taylor, W. R. Notas sobre las algas del Océano Atlántico tropical. Revista americana de botánica 1929, 621-630.

- Gabrielson. P.; Hughey. R.; Diaz-Pulido, G. Genomics reveals abundant speciation in the coral reef building alga Porolithon onkodes (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 429–434. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, D.; Pérez, H. Estimación de la riqueza y abundancia de macroalgas en los arrecifes de Punta Galeta, 15 años después de un derrame de petróleo. Bachelor Thesis, Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Panamá, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, N. Sistemática de las especies de algas coralinas (Corallinophycidae, Rodophyta) formadoras de mantos de rodolitos en el Pacífio Tropical Oriental. Master Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, México, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, E. Marine algae from the 1958 Cruise of the Stella Polaris in the Gulf of California. Los Angeles County Mus.Contr. Sci. 1959, 27, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracterización morfoestructural y molecular de rodolitos (Corallinales ) del Parque Nacional Coiba. XII Congreso de Ficología de Latinoamérica y el Caribe, Costa Rica, November 18-22, 2024.

- Robinson, N.; Fernández-García, C.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Rosas-Alquicira, E.; Konar, B.; Chenelot, H.; Jewett, S.; Melzer, R.; Meyer, R.; Försterra, G.; Häussermann, V.; Macaya, E. Chapter 13: Eastern Pacific. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 319–333.

- Wysor, B.; Kooistra, W. An annotated list of marine Chlorophyta from the Caribbean coast of the Republic of Panama. Nova Hedwig. Beih 2003, 77, 487–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysor, B. An annotated list of marine Chlorophyta from the Pacific Coast of the Republic of Panama with a comparison to Caribbean Panama species. Nova Hedwig. Beih 2004, 78, 209–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuya, F.; Schubert, N.; Aguirre, J.; Basso, D.; Bastos, E.; Berchez, F.; Bernardino, A.; Bosch, N.; Burdett, H. ; Espino,F.; Fernández-Garcia, C.; Francini-Filho, R.; Gagnon, P.; Hall-Spencer, J.; Haroun, R.; Hofmann, L.; Horta, P.; Kamenos, N.; Le Gall, L.; Magris, R.; Martin, S.; Nelson, W.; Neves, P.; Olivé, I.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Peña, V.; Pereira-Filho, G.; Ragazzola, F.; Rebelo, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Rinde, E.; Schoenrock, K.; Silva, J.; Sissini, M.; Tâmega, F. Levelling-up rhodolith-bed science to address global-scale conservation challenges. Sci. Total Environ, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Acuña, V.; Bauer, D.; Bell, K.; Calhoun, A.; Felipe-Lucia, M.; Fitzsimons, J.; González, E.; Kinnison, M.; Lindenmayer, D.; Lundquist, C.; Medellin, R.; Nelson, E.; Poschlod, P. Conserving small natural features with large ecological roles: A synthetic overview. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211(B), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Filho, G.; Bahia, R; Guilherme, H.; Pereira-Filho, G.; Longo, L. Chapter 12: South Atlantic Rhodolith Beds: Latitudinal Distribution, Species Composition, Structure and Ecosystem Functions, Threats and Conservation Status. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 299–314.

- Díaz Licona, C. Mantos de rodolitos (rhodophyta) del pacífico costarricense: caracterización e identificación de posibles servicios ecosistémicos para generar recomendaciones de manejo. Master Thesis, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2024.

- Amado-Filho, G. M.; Maneveldt, G. W.; Pereira-Filho, G. H.; Manso, R. C.; Bahia, R. G.; Barros-Barreto, M. B.; Guimarães, S. M. Seaweed diversity associated with a Brazilian tropical rhodolith bed. Cien. Mar. 2010, 36, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Barquero, A; Sibaja-Cordero, J; Cortés, J. Macrofauna associated with a rhodolith bed at an oceanic island in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Isla del Coco National Park, Costa Rica). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Documentando a los rodolitos:bioingenieros del Parque Nacional Coiba. XIX Congreso Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Panama, September 27, 2023.

- Bassi, D.; Simone, L.; Nebelsick, J. Chapter 6: Re-sedimented Rhodoliths in Channelized Depositional Systems. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 139–168.

- Acuña, F. .; Cortés, J.; Garese, A.; González-Muñoz, R. The sea anemone Exaiptasia diaphana (Actiniaria: Aiptasiidae) associated to rhodoliths at Isla del Coco National Park, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop 2020, 68, S283–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Nutbrown, C.; Hollingsworth, P.; Fernandes, T.; Kamphausen, L.; Baxter, J.; Burdett, H. Species Distribution Modeling Predicts Significant Declines in Coralline Algae Populations Under Projected Climate Change with implications for conservation Policy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 575825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenos, N.; Burdett, H.; Darrenougue, N. Chapter 2: Coralline Algae as Recorders of Past Climatic and Environmental Conditions. In Rhodolith/maërl beds: a global perspective, 1st ed.; R. Riosmena- Rodríguez, W. Nelson, J. Aguirre, Eds.; Springer, Suiza, 2017; pp. 27–53.

- Ragazzola, F.; Foster, L.; Form, A.; Anderson, P.; Hansteen, T.; Fietzke, J. Ocean acidification weakens the structural integrity of coralline algae. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, D.; Maggs, C.; Dring, M. An overview of assessing and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs1998, Scottish Association for Marine Science (UK Marine SACs Project).

- Hall-Spencer, J. Conservation issues relating to maerl beds as habitats for molluscs. J. Conchol. 1998, 2, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Spencer, J.; Grall, J.; Moore, P.; Atkinson, R. Bivalve fishing and maerl-bed conservation in France and the UK-retrospect and prospect. Aquat. Conserv. 2003, 13, S33–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, W.; Halfar, J.; Williams, B. The coralline genus Clathromorphum Foslie emend. Adey; biological, physiological and ecological factors controlling carbonate production in an Arctic/Subarctic climate archive. Smithsonian Contr. Mar. Sc. 2013. 40, 1–83. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Teichert, S.; Bracchi, V.; Rasser, M.; Basso, D. Crustose coralline red algae frameworks and rhodoliths: Past and present. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1090091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunez Horta, P.; Riul, P.; Amado Filho, G.; Gurgel, C.; Berchez, F.; de Castro, J.; Figueiredo, M. Rhodoliths in Brazil: Current knowledge and potential impacts of climate change. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 2016, 64, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J. J.; Herrera, B.; Corrales, L.; Asch, J.; Paaby, P. Identificación de las prioridades de conservación de la biodiversidad marina y costera en Costa Rica, Rev. Biol. Trop 2011, 59, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family/Sub-family/Species | Locality |

|---|---|

|

Corallinaceae Sub-family Chamberlainoideae |

|

| Chamberlainium decipiens (Foslie) Caragnano, Foetisch, Maneveldt & Payri (as Spongites decipiens) [23,24] | Pacific |

| Pneophyllum confervicola (Kützing) YMChamberlain: (as Heteroderma minutulum) [23,24] | Pacific |

|

Sub-family Lithophylloideae |

|

| Lithophyllum coibense Me. Lemoine [12,24] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum brachiatum (Heydrich) Me.Lemoine [12,24,25] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum alternans Me.Lemoine [17,24] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum okamurae Foslie [20] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum prototypum (Foslie) Foslie (as Goniolithon tessellatum) [15,23,24] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum pallescens (Foslie) Foslie [23,24] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum divaricatum M. Lemoine [13,24] | Pacific |

| Lithophyllum neocongestum JJHernandez-Kantun, WHAdey & PWGabrielson [26] | Caribbean |

| Titanoderma pustulatum (JVLamouroux) Nägeli [15,27,28] | Caribbean |

| Sub-family Mastophoroideae | |

|

Goniolithon decutescens (Heydrich) Foslie ex M.Howe [20,25] |

Caribbean |

| Sub-family Metagoniolithoideae | |

|

Harveylithon munitum (Foslie & M.Howe) A.Rösler, Perfectti, V.Peña & JCBraga [21,29] |

Caribbean |

| Sub-family Neogoniolithoideae | |

|

Neogoniolithon trichotomum (Heydrich)Setchell et L.R. Mason [23,24] |

Pacific |

| Hapalidiaceae | |

|

Sub-family Melobesioideae |

|

| Lithothamnion australe Foslie [23,24] | Pacific |

| Lithothamnion australe f.americanum Foslie [13,24] | Pacific |

| Lithothamnion crispatum Hauck (as L. indicum) [12,17,24] | Pacific |

| Lithothamnion australe f. minutulum Foslie (as Mesophyllum australe var. minutula ) [12] | Pacific |

|

Mesophyllum australe var. tualense (Foslie) Mc. Lemoine [12,24] |

Pacific |

| Sporolithaceae | |

| Sporolithon episporum (M.Howe) EYDawson [12,15,17,27] | Caribbean |

|

Sporolithon howei (Lemoine) N.Y. Yamaguishi-Tomita ex M-J. Wynne: (asArchaeolithothamnion howei) [12,14,24] |

Pacific |

| Locality/Species |

|---|

|

CARIBBEAN Ϯ Clathromorphum Foslie |

| Hydrolithon farinosum (J.V.Lamouroux) Penrose & Y.M.Chamberlain (as Fosliella farinosa) [15,25,27] |

| Lithophyllum corallinae (P.Crouan y H.Crouan) Heydrich [18] |

| Ϯ Lithophyllum kaiseri (Heydrich) Heydrich |

| Lithophyllum stictaeforme (Areschoug) Hauck [19] |

| Ϯ Mesophyllum mesomorphum (Foslie) WHAdey |

| Neogoniolithon spectabile (Foslie) Setchell & LRMason [30] |

| Ϯ Neogoniolithon strictum (Foslie) Setchell y LRMason |

|

Porolithon sp. Foslie [15] |

| PACIFIC |

| Fosliella fertilis (M. Lemoine) Segonzac [17,24] |

| Fosliella minuta W.R. Taylor [13,15,24] |

| Ϯ Hydrolithon boergesenii (Foslie) Foslie |

| Ϯ Hydrolithon breviclavium (Foslie) Foslie |

| ϮHydrolithon boergesenii (Foslie) Foslie |

| Ϯ Lithophyllum imitans Foslie |

| Ϯ Lithophyllum kotschyanum Foslie |

| Ϯ Phymatolithon lenormandii (Areschoug) WHAdey |

| Ϯ Mesophyllum engelhartii (Foslie) WHAdey |

| Phymatolithon masonianum Wilks & Woelkerling [31] |

| Ϯ Porolithon onkodes (Heydrich) Foslie [24,32] |

| Ϯ Porolithon sonorense EY Dawson |

| ϮSpongites fruticulosus Kützing [33] |

| SITE | Latitude °N | Longitude°W | Coverage (%) | Depth (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canales de Afuera | 7.68888 | -81.63419 | 46 | 45 |

| Buffet | 7.68537 | -81.61061 | 49 | 55 |

| Don Juan | 7.39809 | -81.63869 | 65 | 42 |

| Iglesias | 7.64542 | -81.69166 | 69 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).