Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Ovalbumin Immunization

Infection

In Vitro Cell Culture

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

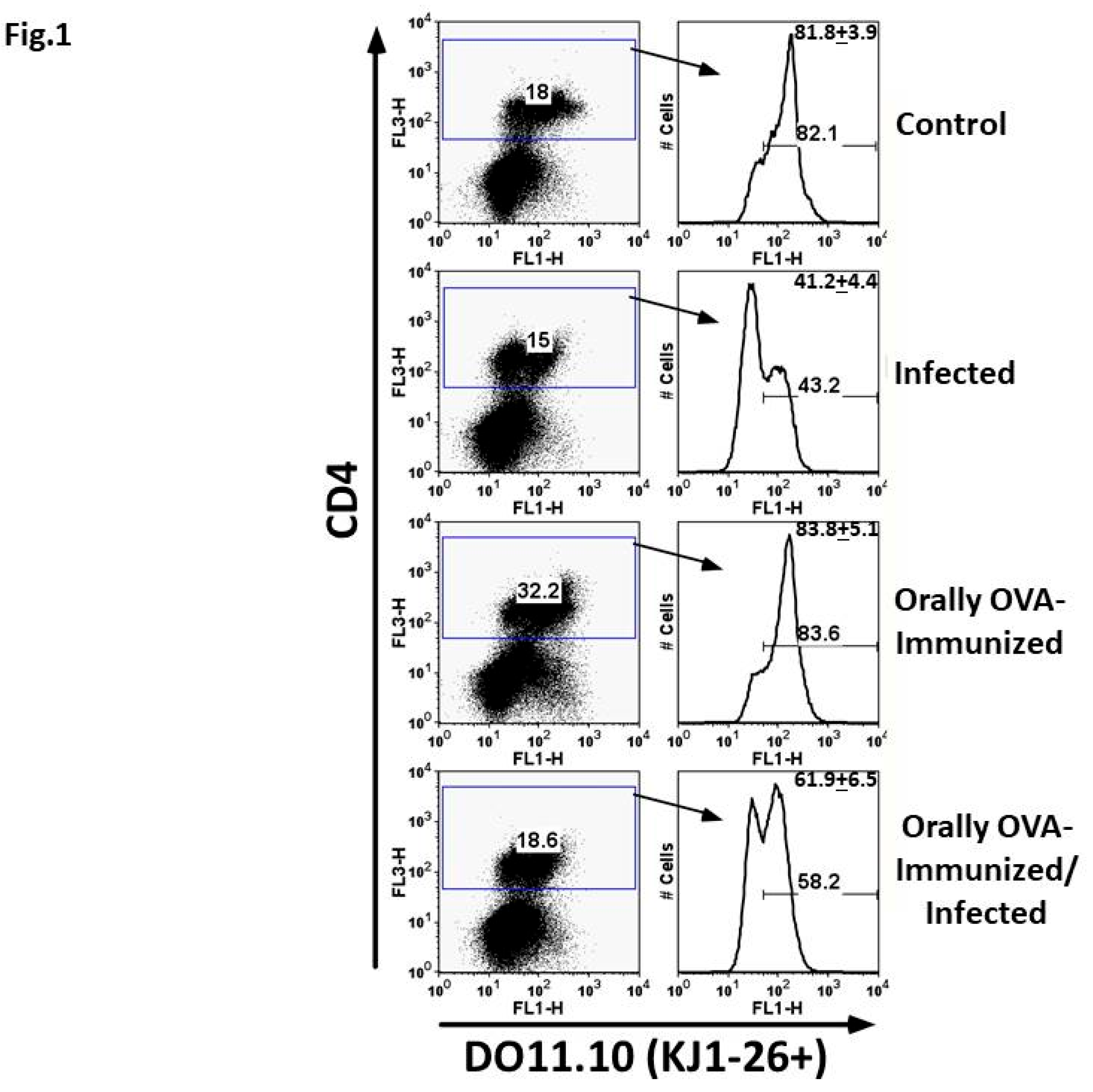

Percentage of CD4+DO11.10+ T Cells in Experimental Groups Submitted to Different Treatments

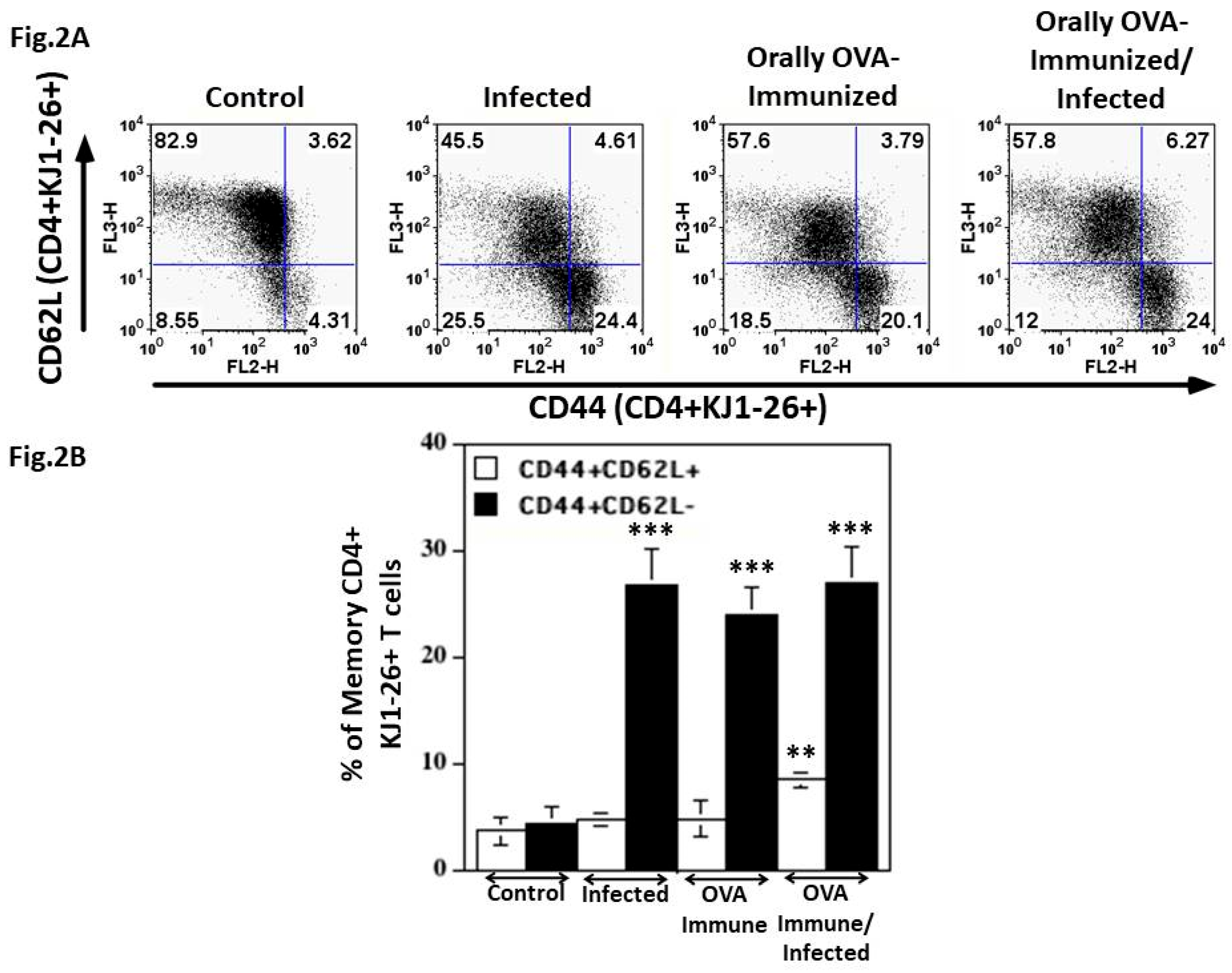

DO11.10 Transgenic CD4+ T Cells are Activated to Effector Memory Lymphocytes During the Acute T. cruzi Infection

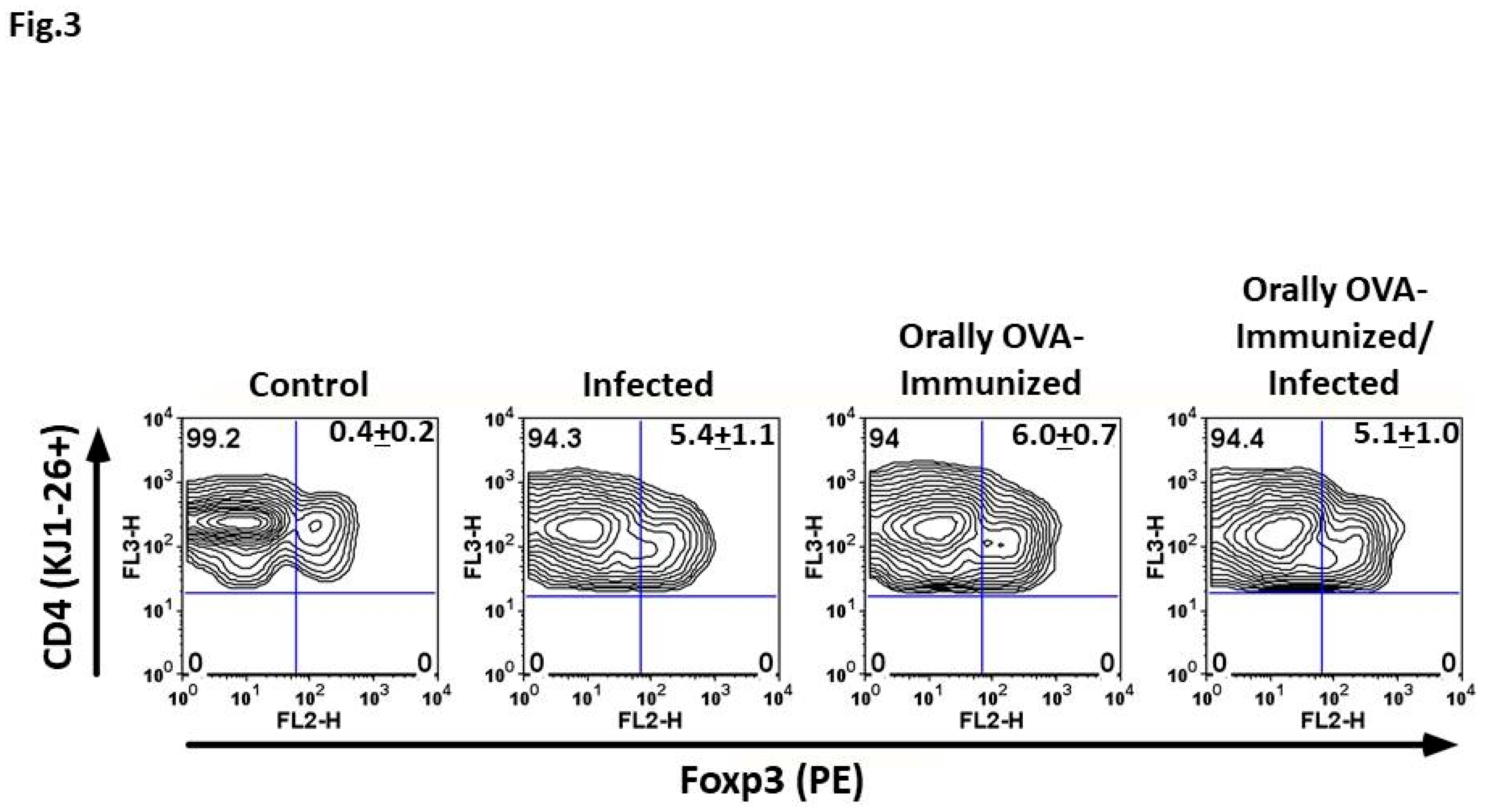

T. cruzi Infection Induces Foxp3 Expression in DO11.10+ CD4+ Splenic T Cells

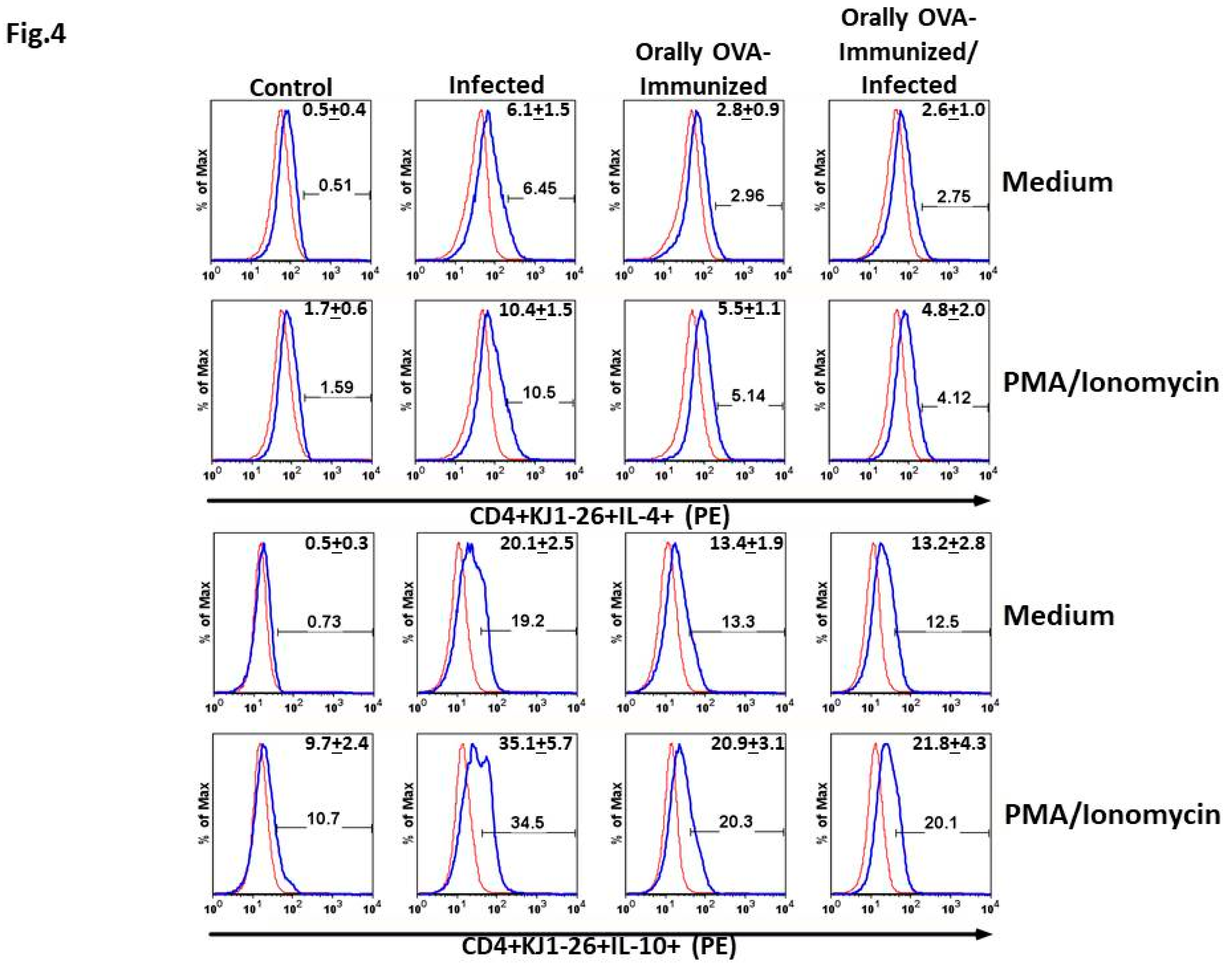

DO11.10 Transgenic CD4+ T Cells Spontaneously Produce IL-4 and IL-10 upon T. cruzi Infection

T. cruzi Infection Increases the Frequencies of Splenic TNF-α+ and IFN-γ+ DO11.10 Transgenic T Cells

DISCUSSION

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D.V. Andrade, K.J. Gollob, W.O. Dutra, Acute chagas disease: new global challenges for an old neglected disease, PLoS neglected tropical diseases 8(7) (2014) e3010. [CrossRef]

- F. Cardillo, R.T. de Pinho, P.R. Antas, J. Mengel, Immunity and immune modulation in Trypanosoma cruzi infection, Pathogens and disease 73(9) (2015) ftv082.

- P.M. Minoprio, A. Coutinho, M. Joskowicz, M.R. D'Imperio Lima, H. Eisen, Polyclonal lymphocyte responses to murine Trypanosoma cruzi infection. II. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Scandinavian journal of immunology 24(6) (1986) 669-79.

- D. Mason, A very high level of crossreactivity is an essential feature of the T-cell receptor, Immunology today 19(9) (1998) 395-404. [CrossRef]

- G. Petrova, A. Ferrante, J. Gorski, Cross-reactivity of T cells and its role in the immune system, Critical reviews in immunology 32(4) (2012) 349-72. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Lang, H. Jacobsen, S. Ikemizu, C. Andersson, K. Harlos, L. Madsen, P. Hjorth, L. Sondergaard, A. Svejgaard, K. Wucherpfennig, D.I. Stuart, J.I. Bell, E.Y. Jones, L. Fugger, A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis, Nature immunology 3(10) (2002) 940-3. [CrossRef]

- U. Christen, K.H. Edelmann, D.B. McGavern, T. Wolfe, B. Coon, M.K. Teague, S.D. Miller, M.B. Oldstone, M.G. von Herrath, A viral epitope that mimics a self antigen can accelerate but not initiate autoimmune diabetes, The Journal of clinical investigation 114(9) (2004) 1290-8.

- S. Sharma, P.G. Thomas, The two faces of heterologous immunity: protection or immunopathology, Journal of leukocyte biology 95(3) (2014) 405-16. [CrossRef]

- K.D. Moudgil, S.J. Thompson, F. Geraci, B. De Paepe, Y. Shoenfeld, Heat-shock proteins in autoimmunity, Autoimmune diseases 2013 (2013) 621417.

- R. van der Zee, S.M. Anderton, A.B. Prakken, A.G. Liesbeth Paul, W. van Eden, T cell responses to conserved bacterial heat-shock-protein epitopes induce resistance in experimental autoimmunity, Seminars in immunology 10(1) (1998) 35-41. [CrossRef]

- G. Zheng, T.T. Oo, S.S.S. Janjam, C. Ellis, S. Pallikonda Chakravarthy, S. Palani, W. Anthon, G. Tsaras, A. Williams, A. Feng, A. Chen, An antigen-less pro-vaccine for treating autoimmunity, Journal of immunology 214(7) (2025) 1477-1482. [CrossRef]

- Y. Belkaid, T.W. Hand, Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation, Cell 157(1) (2014) 121-41.

- F. Cardillo, R.P. Falcao, M.A. Rossi, J. Mengel, An age-related gamma delta T cell suppressor activity correlates with the outcome of autoimmunity in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection, European journal of immunology 23(10) (1993) 2597-605.

- F. Cardillo, A. Nomizo, J. Mengel, The role of the thymus in modulating gammadelta T cell suppressor activity during experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection, International immunology 10(2) (1998) 107-16.

- M.E. Bunkofske, P. Dash, W. Awad, P.G. Thomas, R.L. Tarleton, Highly cross-reactive and competent effectors dominate the CD8+ T cell response in Trypanosoma cruzi infection, Journal of immunology (2025). [CrossRef]

- K.M. Murphy, A.B. Heimberger, D.Y. Loh, Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo, Science 250(4988) (1990) 1720-3.

- P. Zhou, R. Borojevic, C. Streutker, D. Snider, H. Liang, K. Croitoru, Expression of dual TCR on DO11.10 T cells allows for ovalbumin-induced oral tolerance to prevent T cell-mediated colitis directed against unrelated enteric bacterial antigens, Journal of immunology 172(3) (2004) 1515-23. [CrossRef]

- J. Nihei, F. Cardillo, J. Mengel, The Blockade of Interleukin-2 During the Acute Phase of Trypanosoma cruzi Infection Reveals Its Dominant Regulatory Role, Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 11 (2021) 758273.

- F. Cardillo, F.Q. Cunha, W.M. Tamashiro, M. Russo, S.B. Garcia, J. Mengel, NK1.1+ cells and T-cell activation in euthymic and thymectomized C57Bl/6 mice during acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection, Scandinavian journal of immunology 55(1) (2002) 96-104.

- A.C.O. Silva, M. Bonfim, J.L.M. Fontes, W.L.C. Dos-Santos, J. Mengel, F. Cardillo, C57BL/6 Mice Pretreated With Alpha-Tocopherol Show a Better Outcome of Trypanosoma cruzi Infection With Less Tissue Inflammation and Fibrosis, Frontiers in immunology 13 (2022) 833560. [CrossRef]

- D. Li, M. Wu, Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases, Signal transduction and targeted therapy 6(1) (2021) 291.

- S.P. Hickman, L.A. Turka, Homeostatic T cell proliferation as a barrier to T cell tolerance, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 360(1461) (2005) 1713-21. [CrossRef]

- D.L. Martin, D.B. Weatherly, S.A. Laucella, M.A. Cabinian, M.T. Crim, S. Sullivan, M. Heiges, S.H. Craven, C.S. Rosenberg, M.H. Collins, A. Sette, M. Postan, R.L. Tarleton, CD8+ T-Cell responses to Trypanosoma cruzi are highly focused on strain-variant trans-sialidase epitopes, PLoS pathogens 2(8) (2006) e77.

- G.A. DosReis, M.F. Lopes, The importance of apoptosis for immune regulation in Chagas disease, Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 104 Suppl 1 (2009) 259-62. [CrossRef]

- E. Kondo, H. Wakao, H. Koseki, T. Takemori, S. Kojo, M. Harada, M. Takahashi, S. Sakata, C. Shimizu, T. Ito, T. Nakayama, M. Taniguchi, Expression of recombination-activating gene in mature peripheral T cells in Peyer's patch, International immunology 15(3) (2003) 393-402. [CrossRef]

- C.J. McMahan, P.J. Fink, RAG reexpression and DNA recombination at T cell receptor loci in peripheral CD4+ T cells, Immunity 9(5) (1998) 637-47. [CrossRef]

- P. Serra, A. Amrani, B. Han, J. Yamanouchi, S.J. Thiessen, P. Santamaria, RAG-dependent peripheral T cell receptor diversification in CD8+ T lymphocytes, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99(24) (2002) 15566-71.

- L.Y. Derksen, K. Tesselaar, J.A.M. Borghans, Memories that last: Dynamics of memory T cells throughout the body, Immunological reviews 316(1) (2023) 38-51. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Kaech, E.J. Wherry, R. Ahmed, Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development, Nature reviews. Immunology 2(4) (2002) 251-62.

- D. Antunes, A. Marins-Dos-Santos, M.T. Ramos, B.A.S. Mascarenhas, C.J.C. Moreira, D.A. Farias-de-Oliveira, W. Savino, R.Q. Monteiro, J. de Meis, Oral Route Driven Acute Trypanosoma cruzi Infection Unravels an IL-6 Dependent Hemostatic Derangement, Frontiers in immunology 10 (2019) 1073.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).