Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

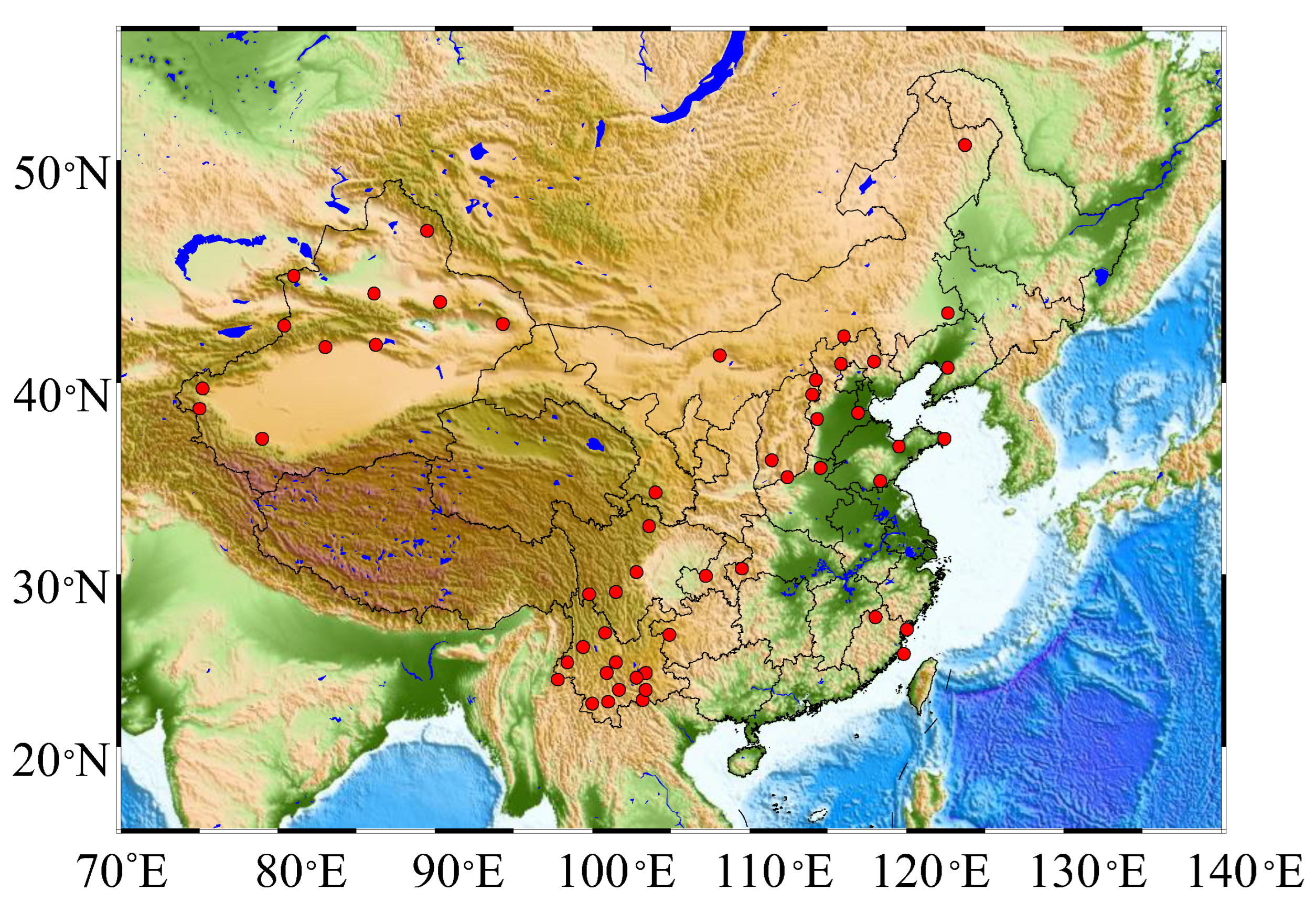

2.1. Data

2.2. Methods

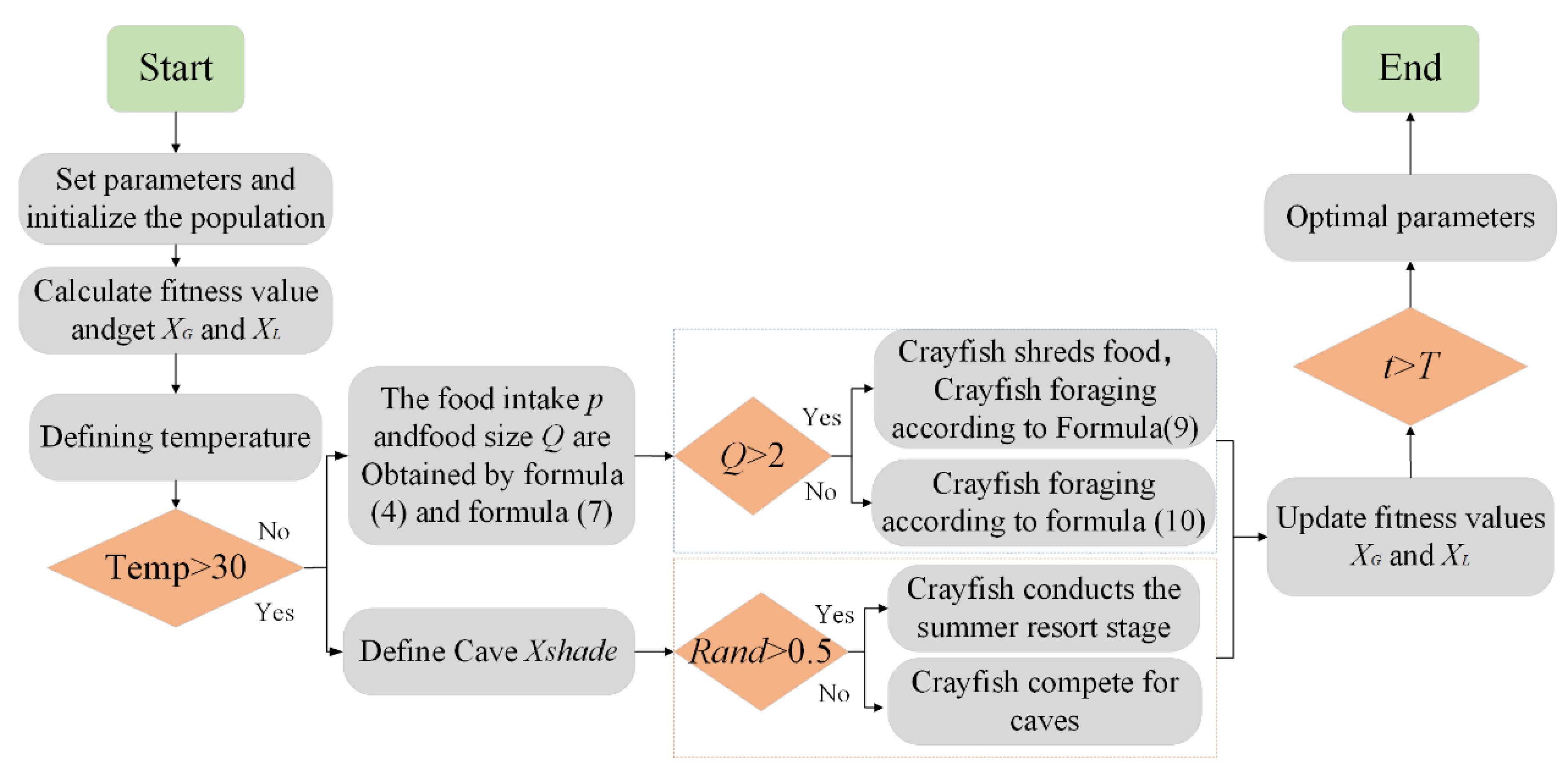

2.2.1. Crayfish Optimization Algorithm

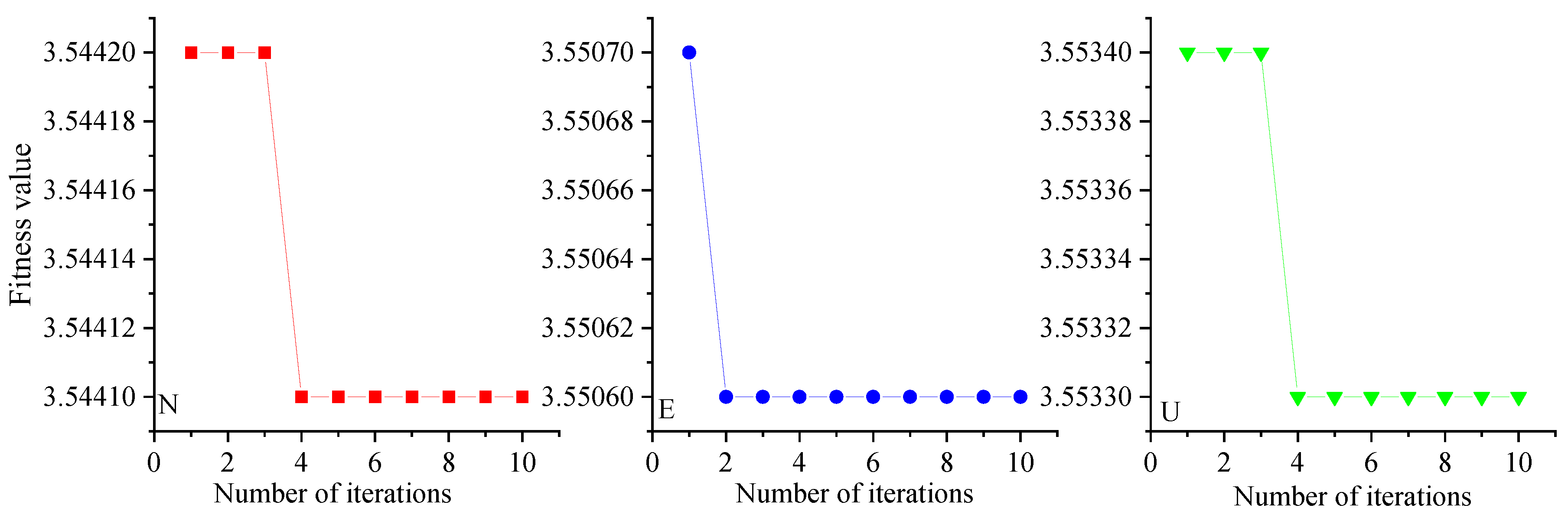

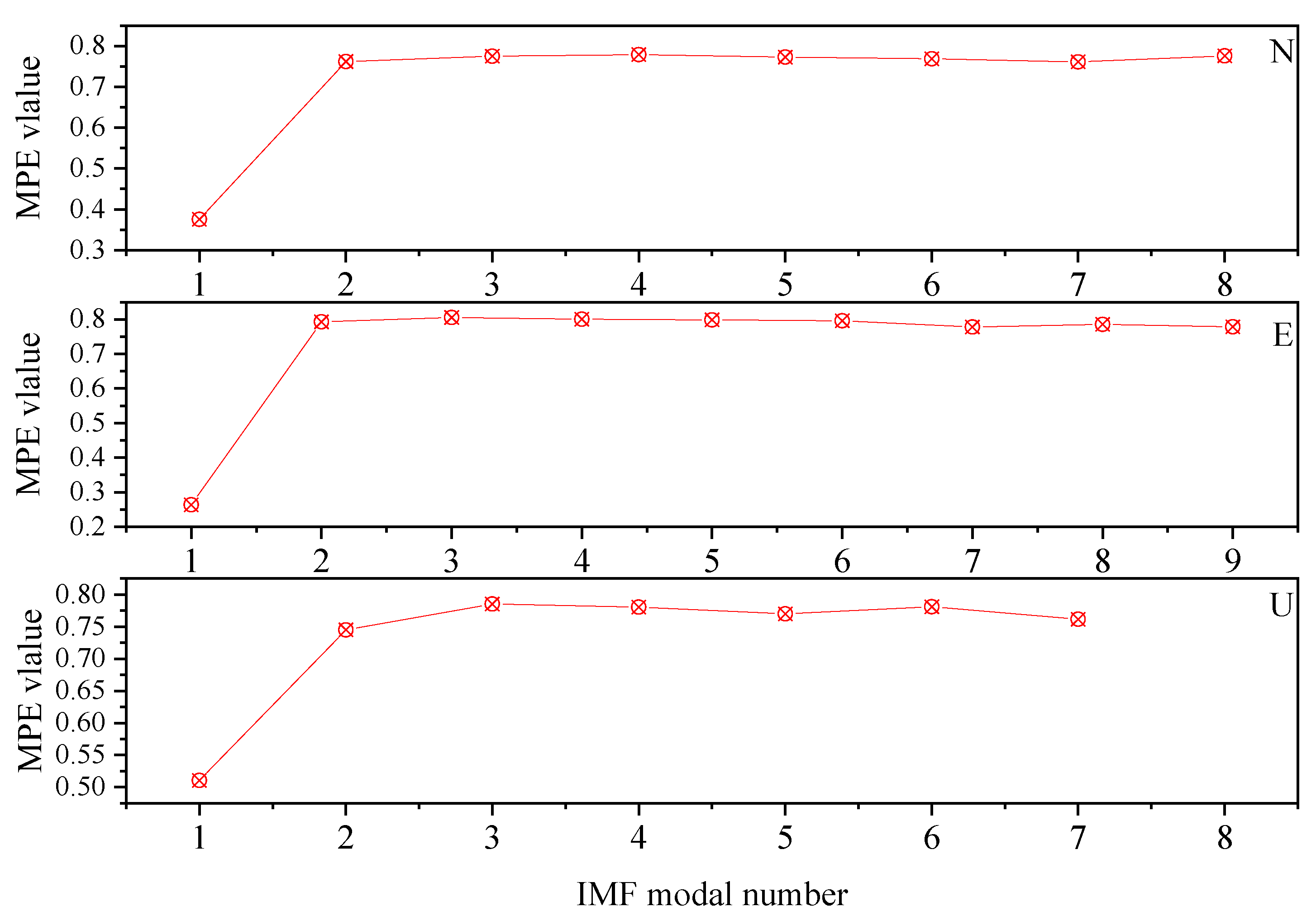

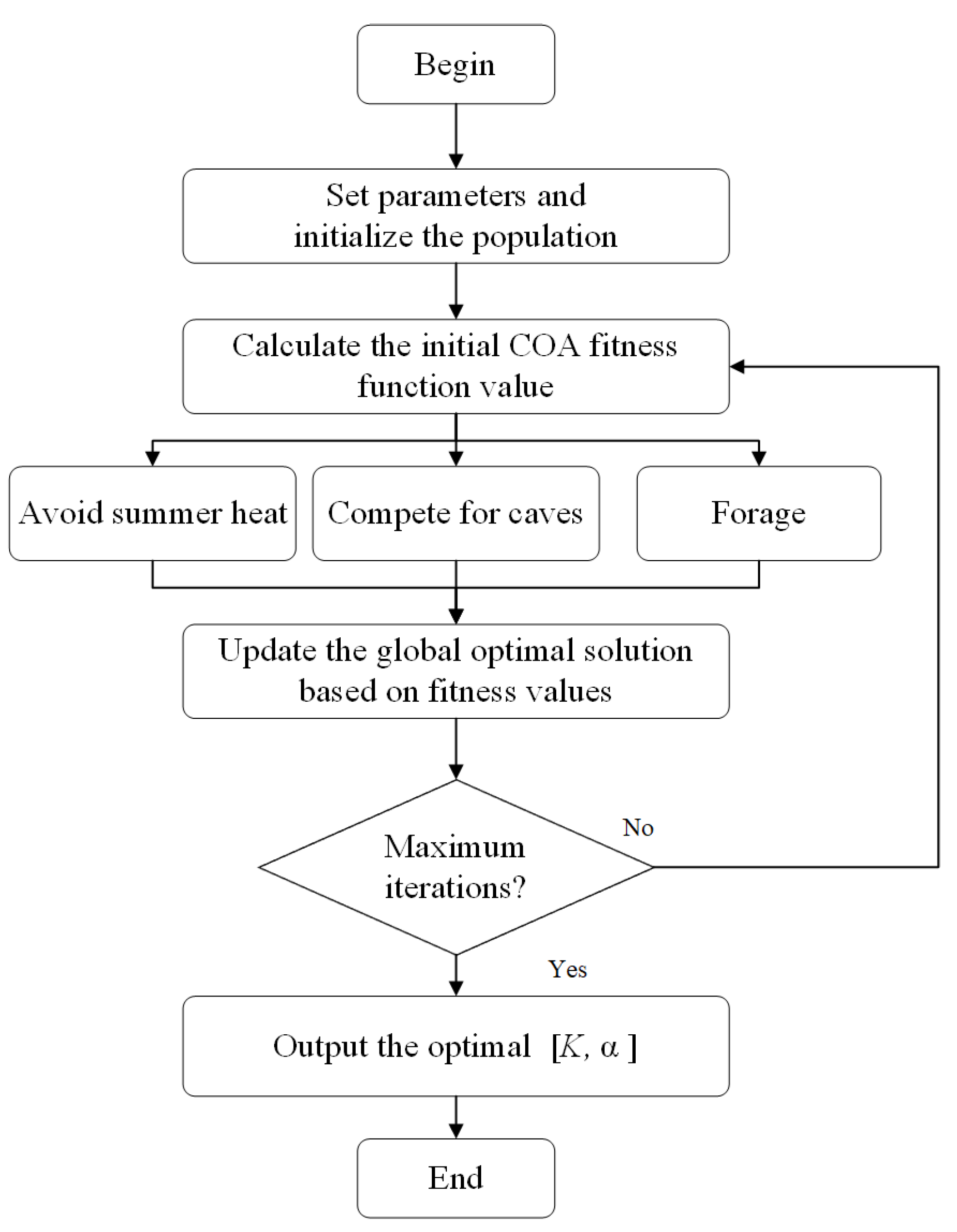

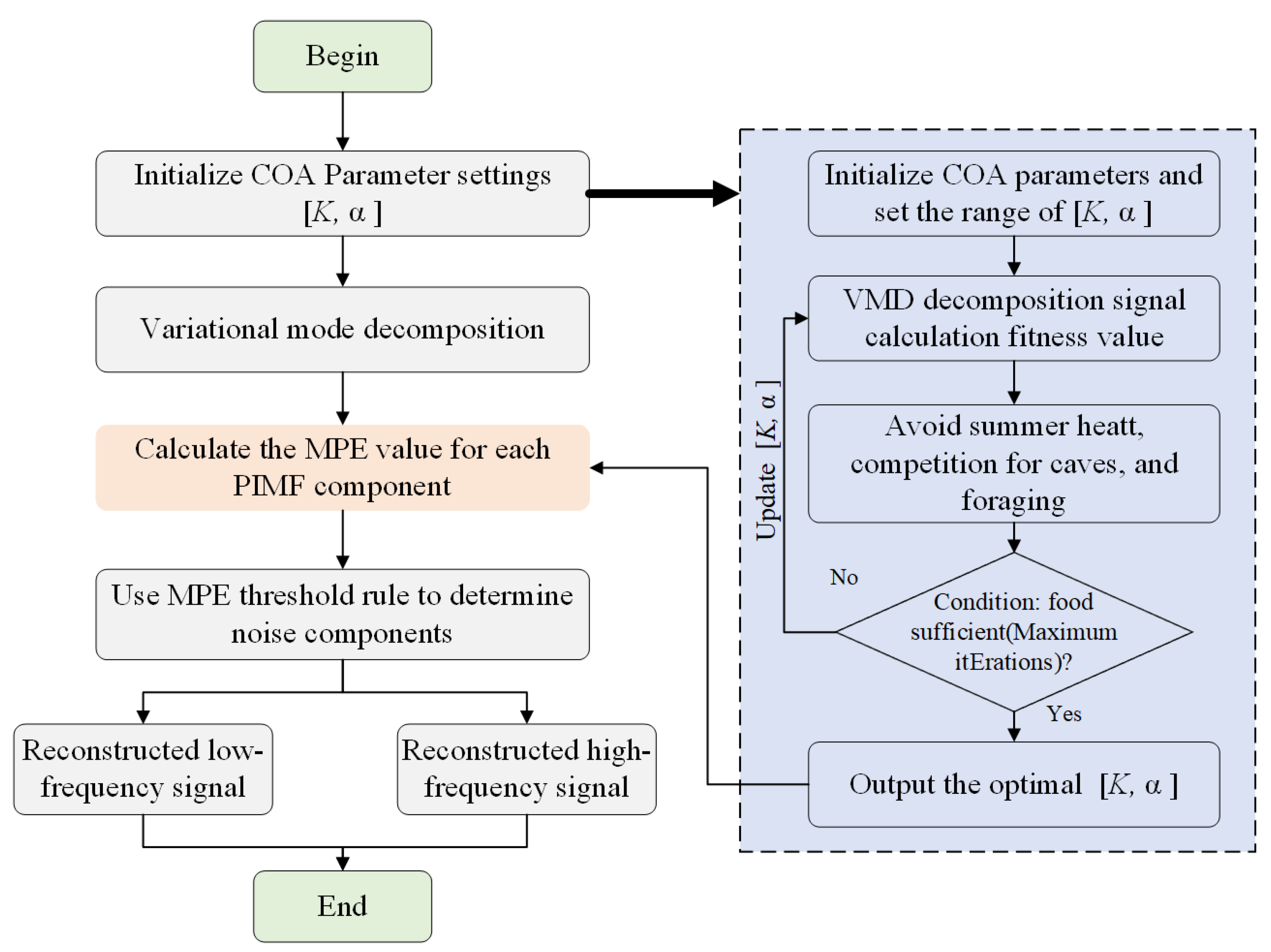

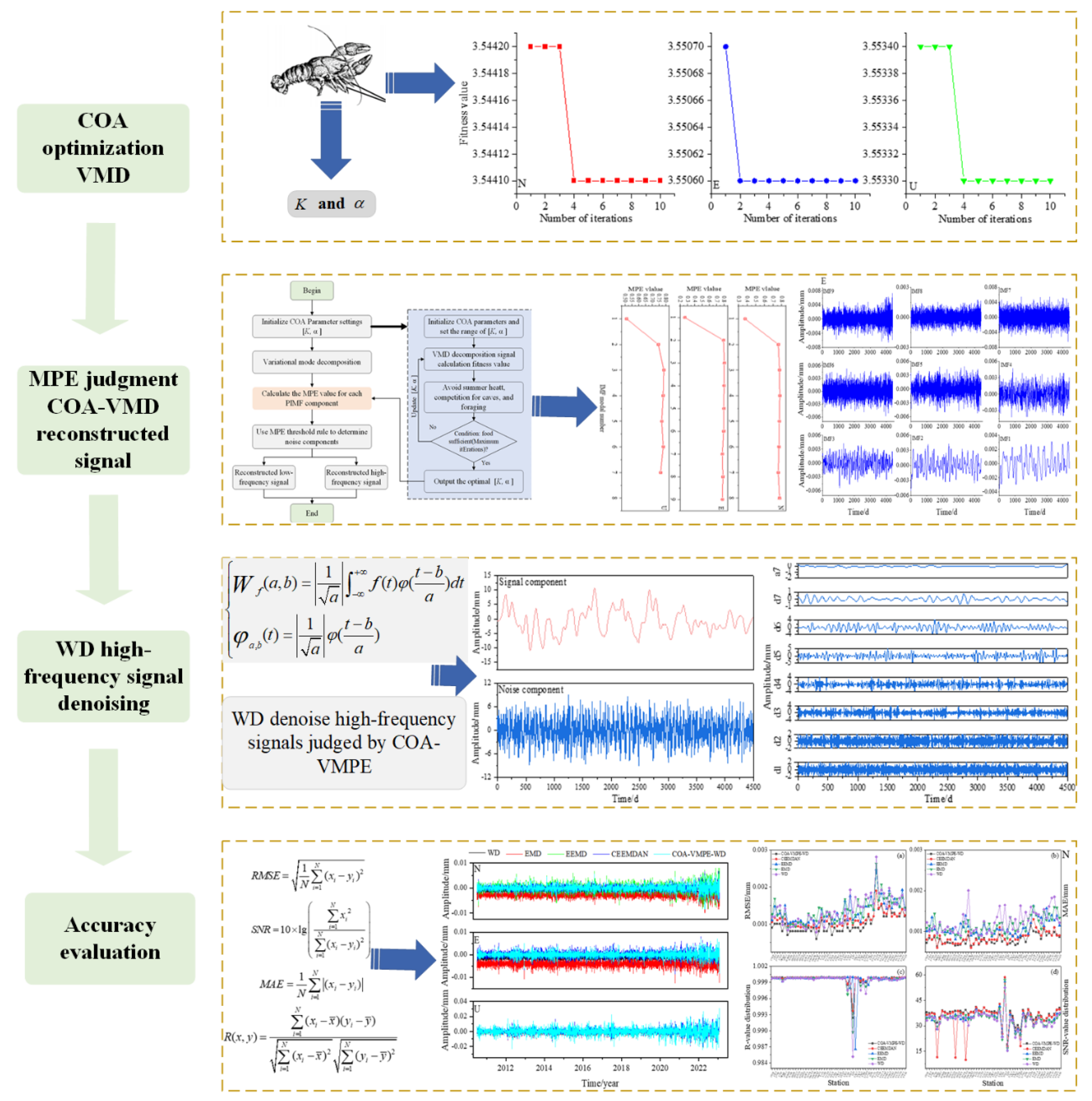

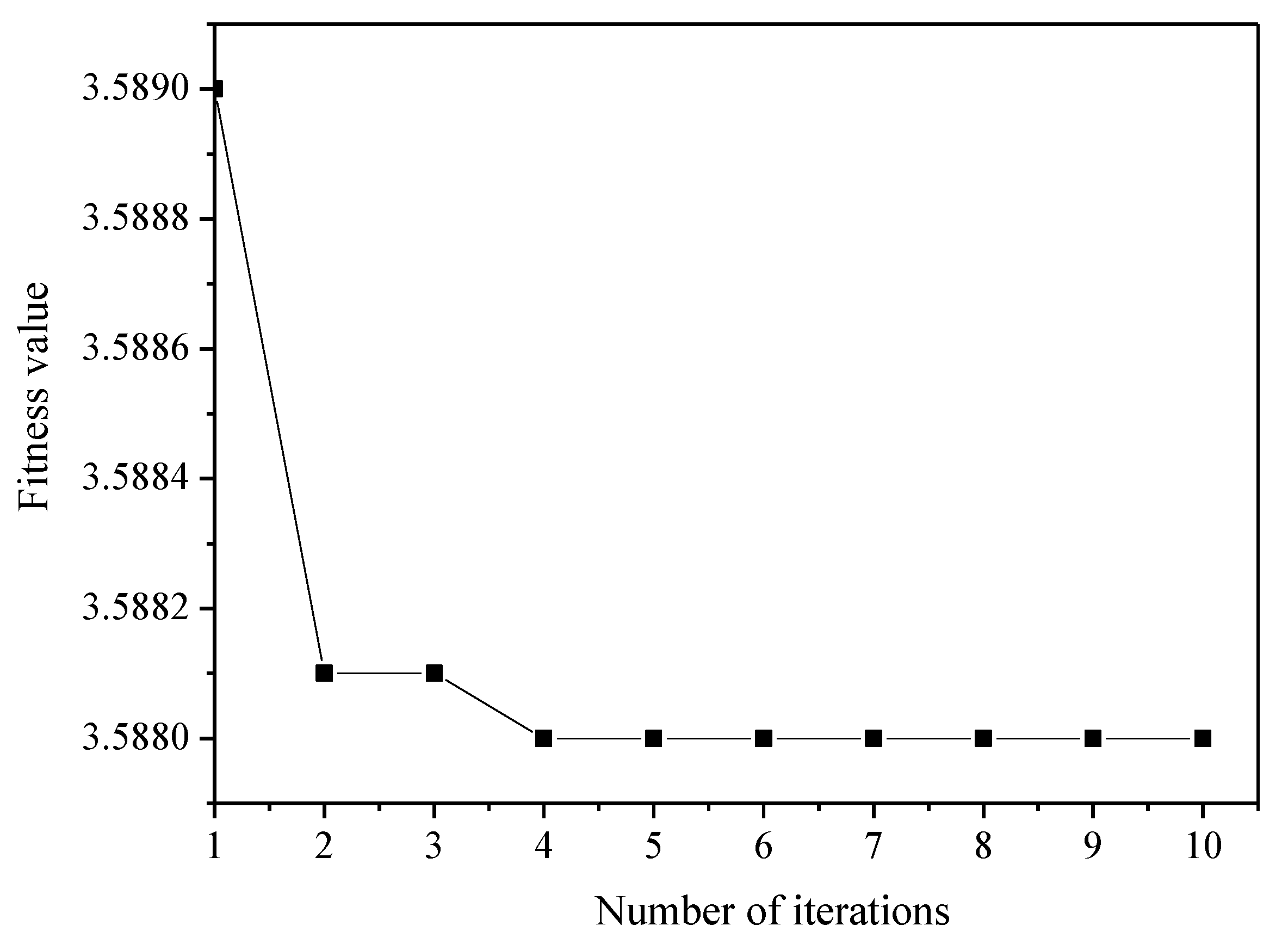

2.2.2. COA optimization VMD

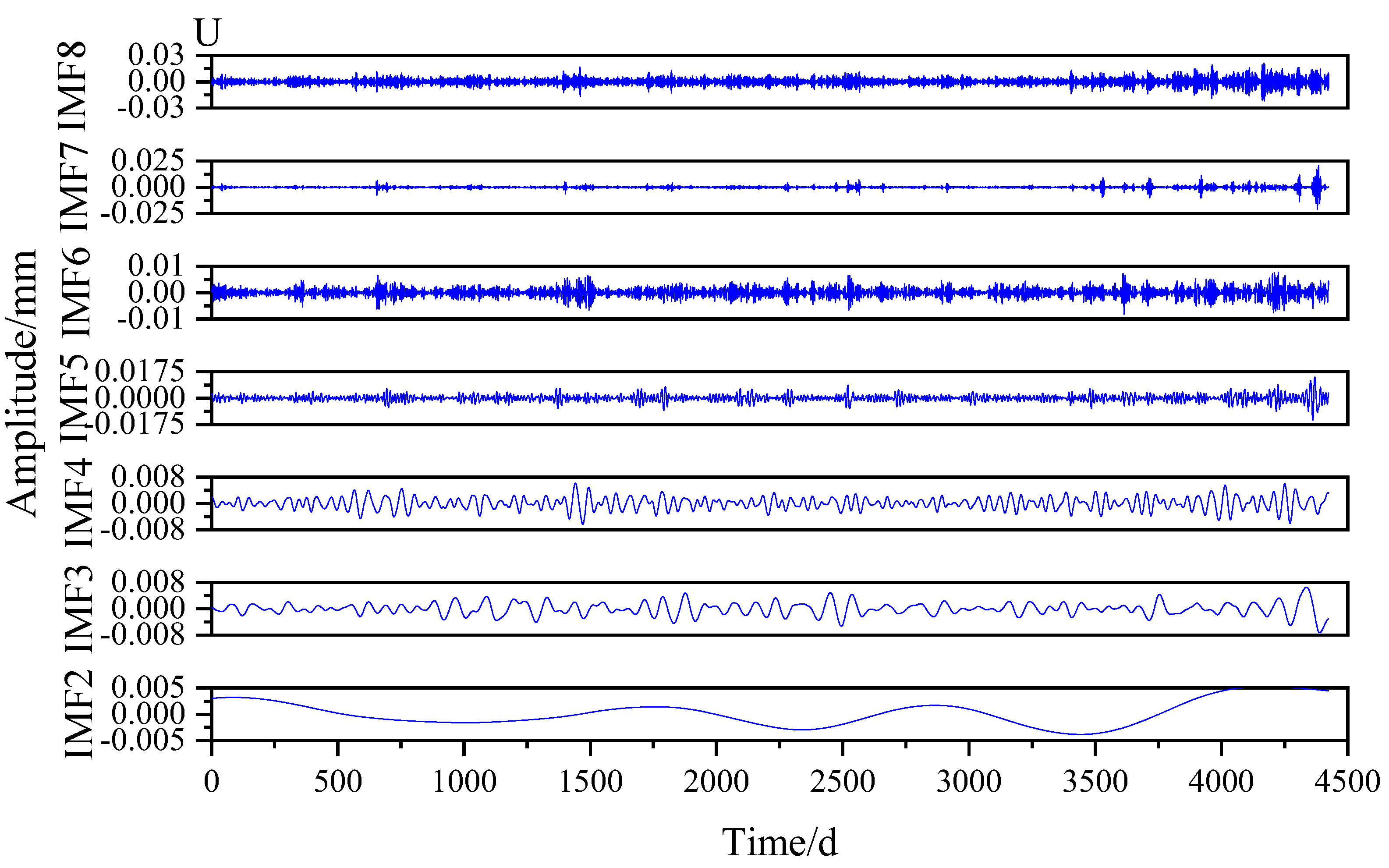

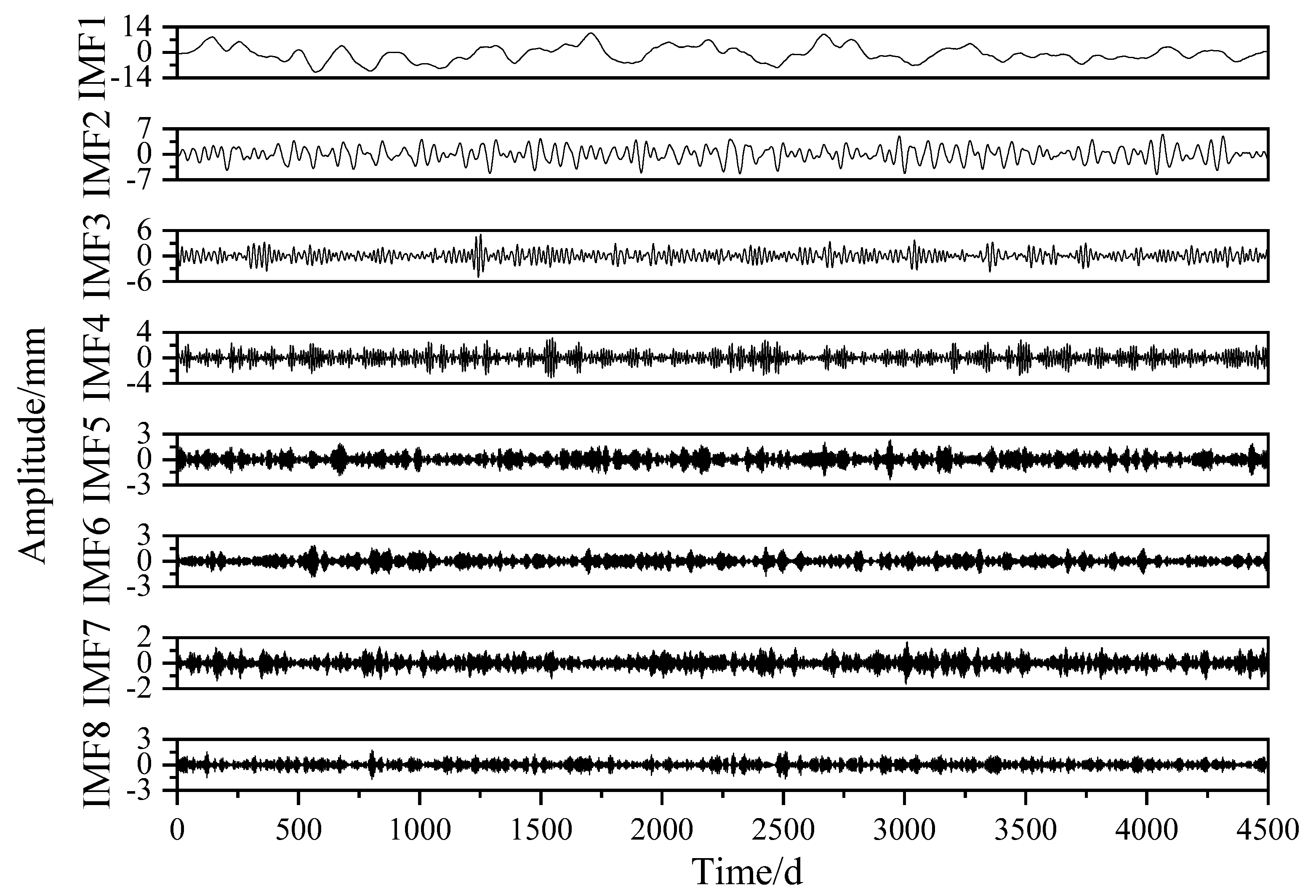

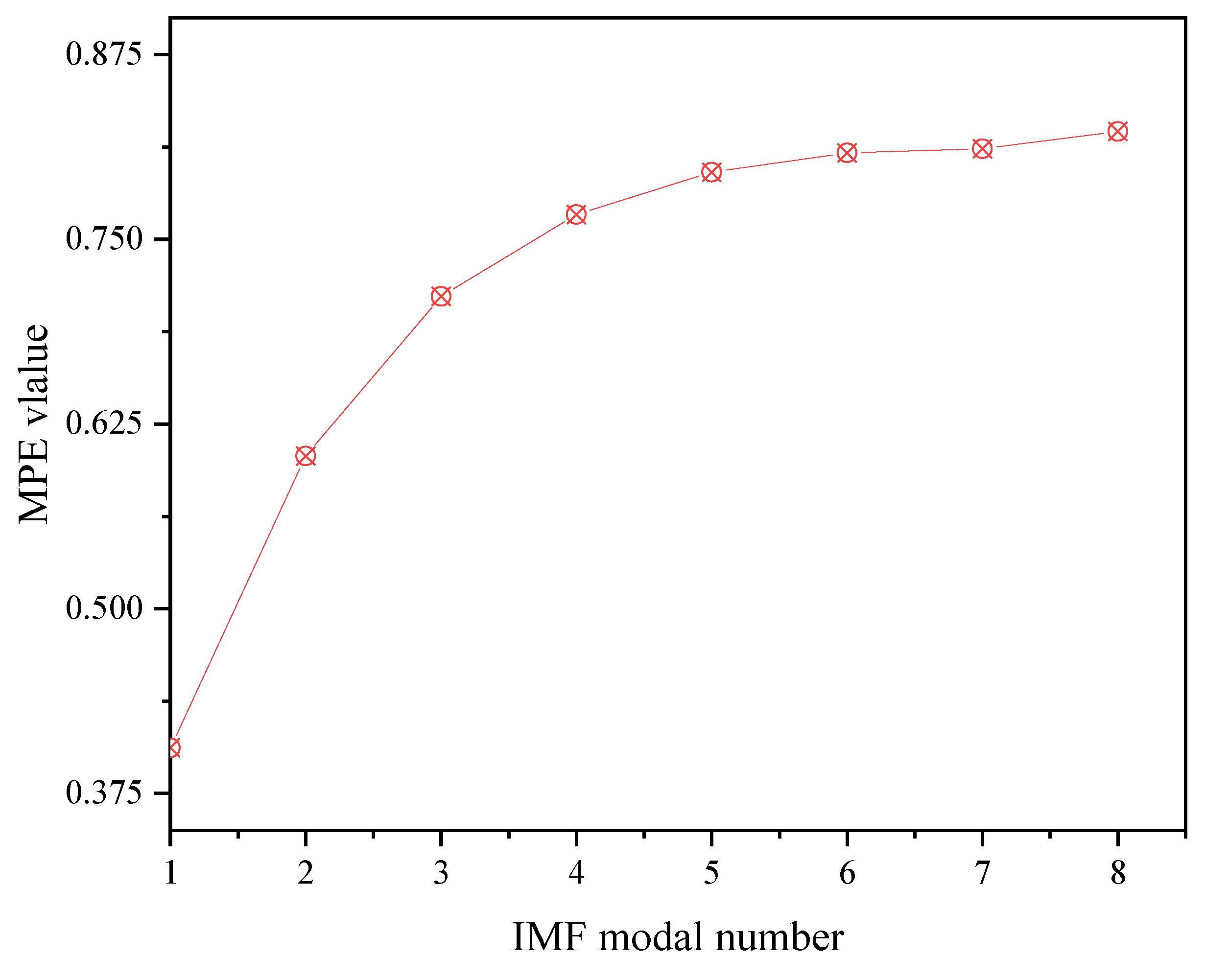

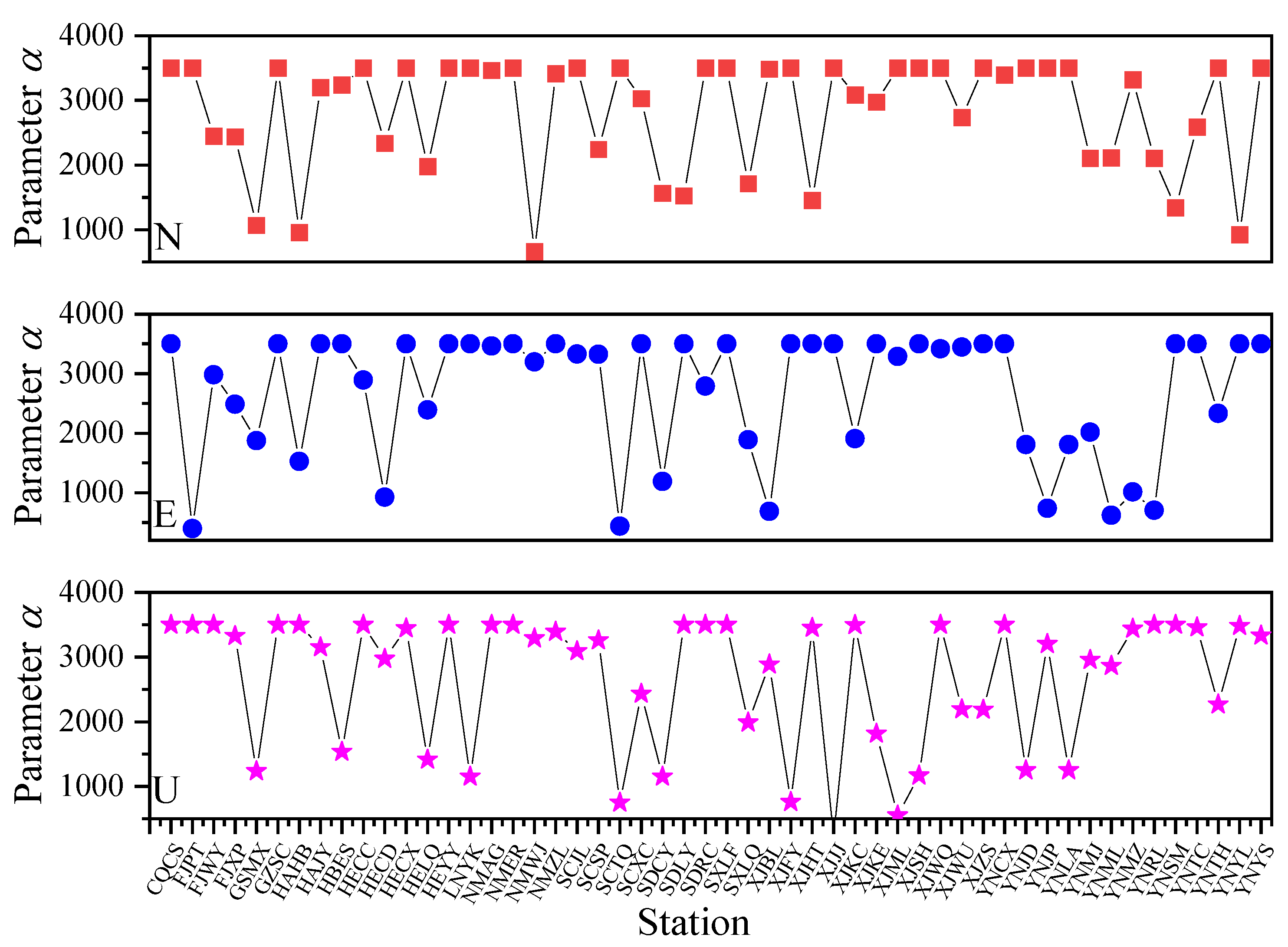

2.2.3. Multi-scale Permutation Entropy Judgment of COA-VMD Reconstructed Signal

2.2.4. COA-VMPE-WD Algorithm

2.2.5. Evaluation Index

3. Results

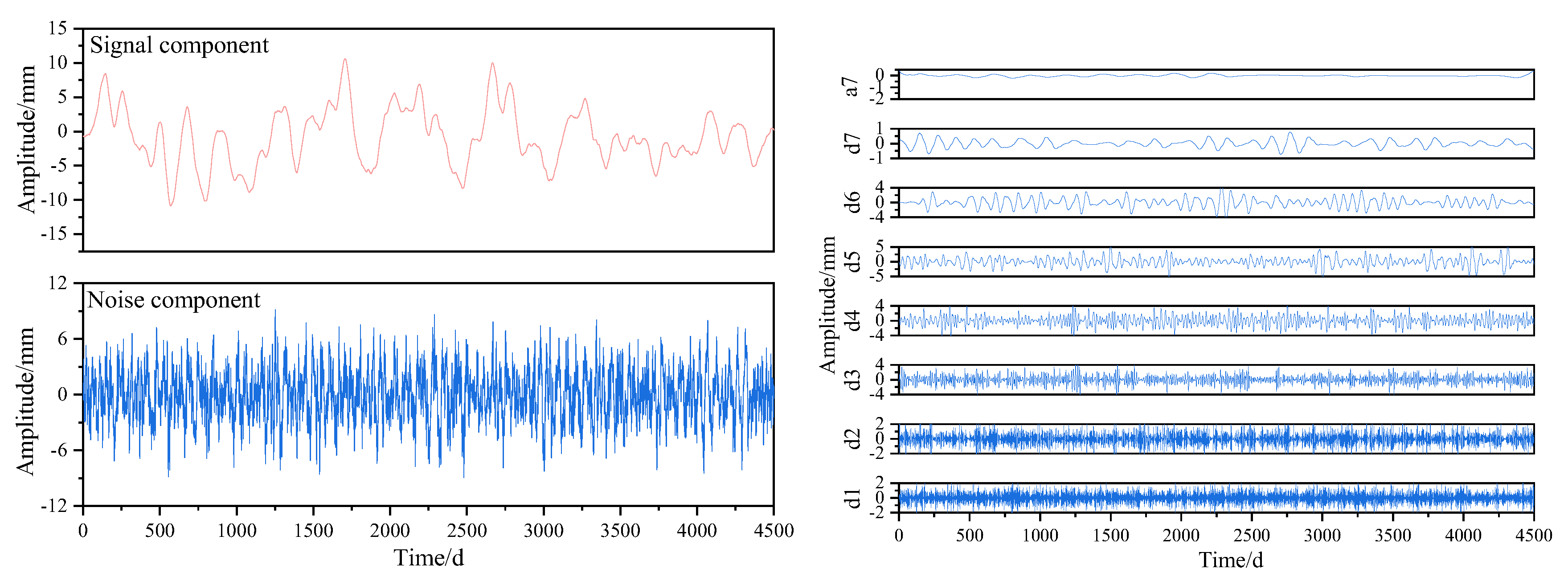

3.1. Simulation Signal Decomposition

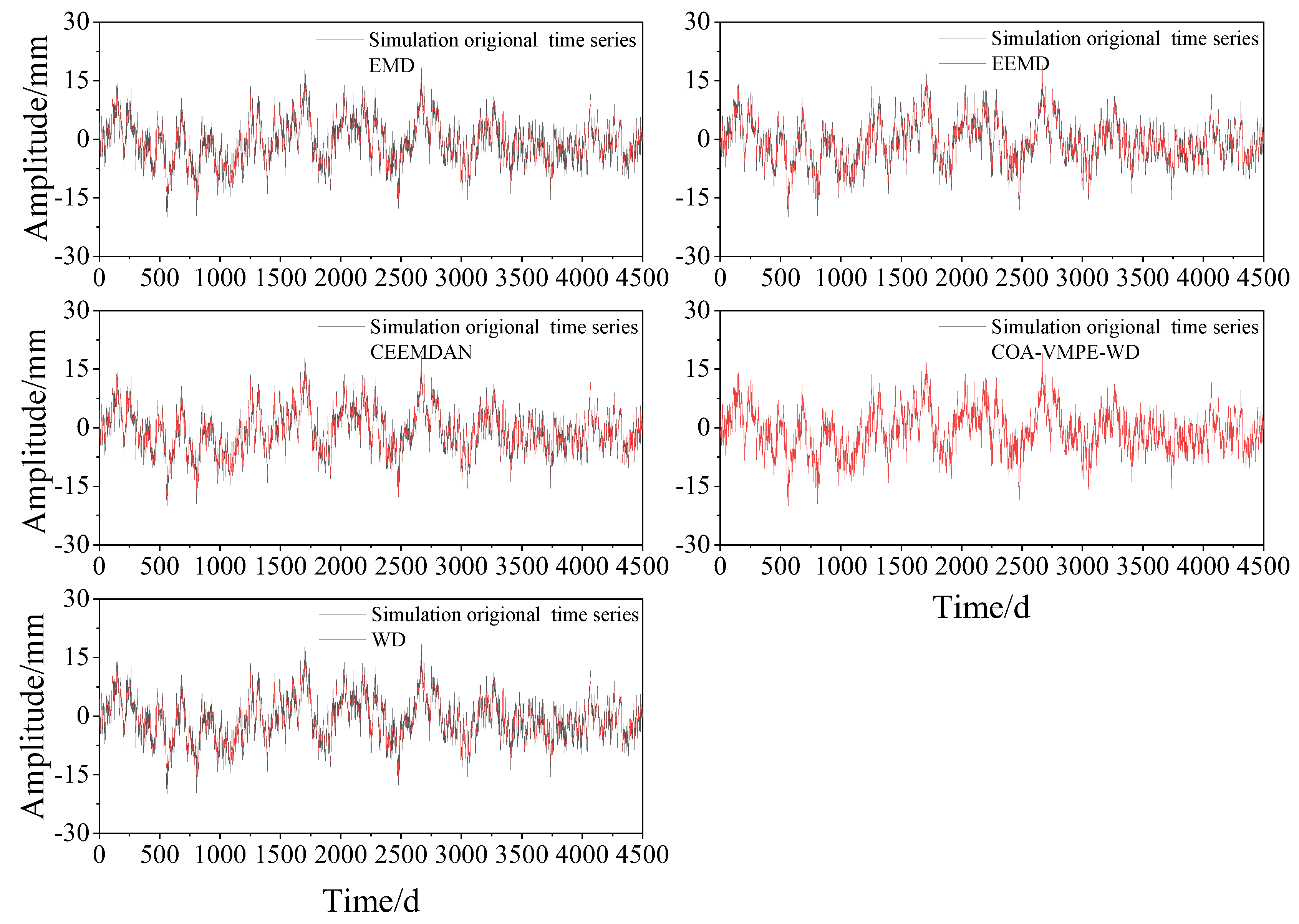

3.2. Evaluation of Noise Reduction Effect of Simulated Signals

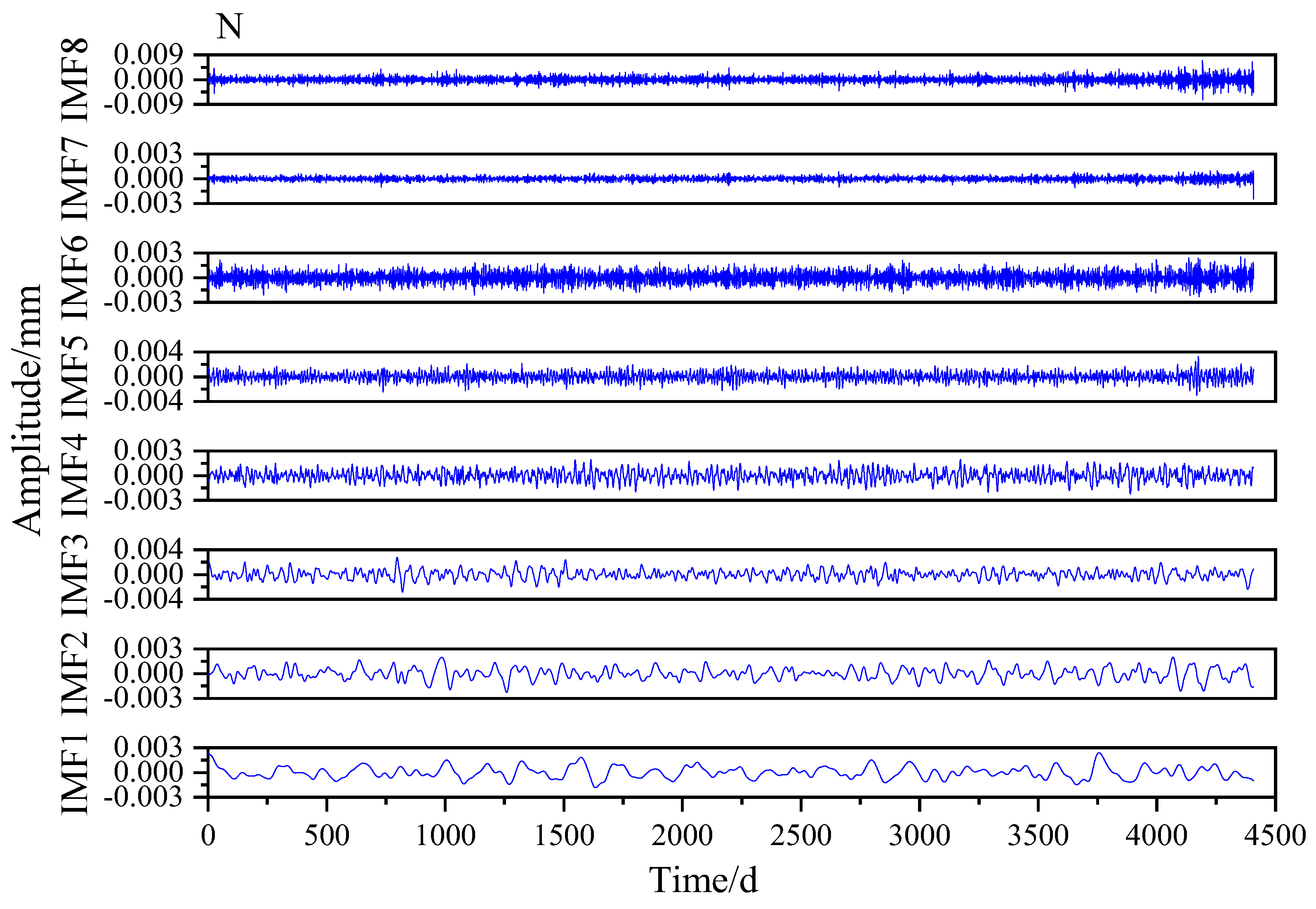

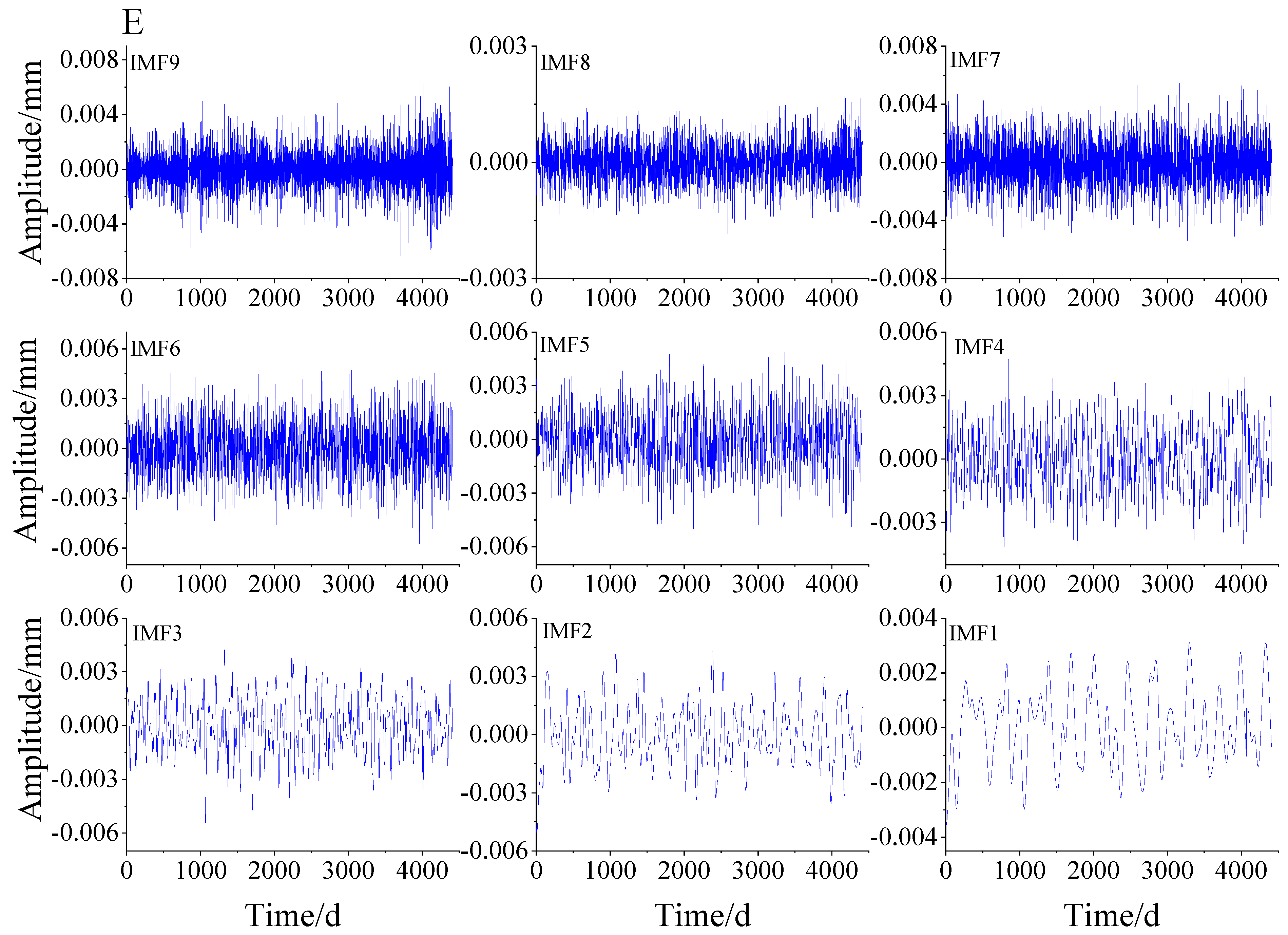

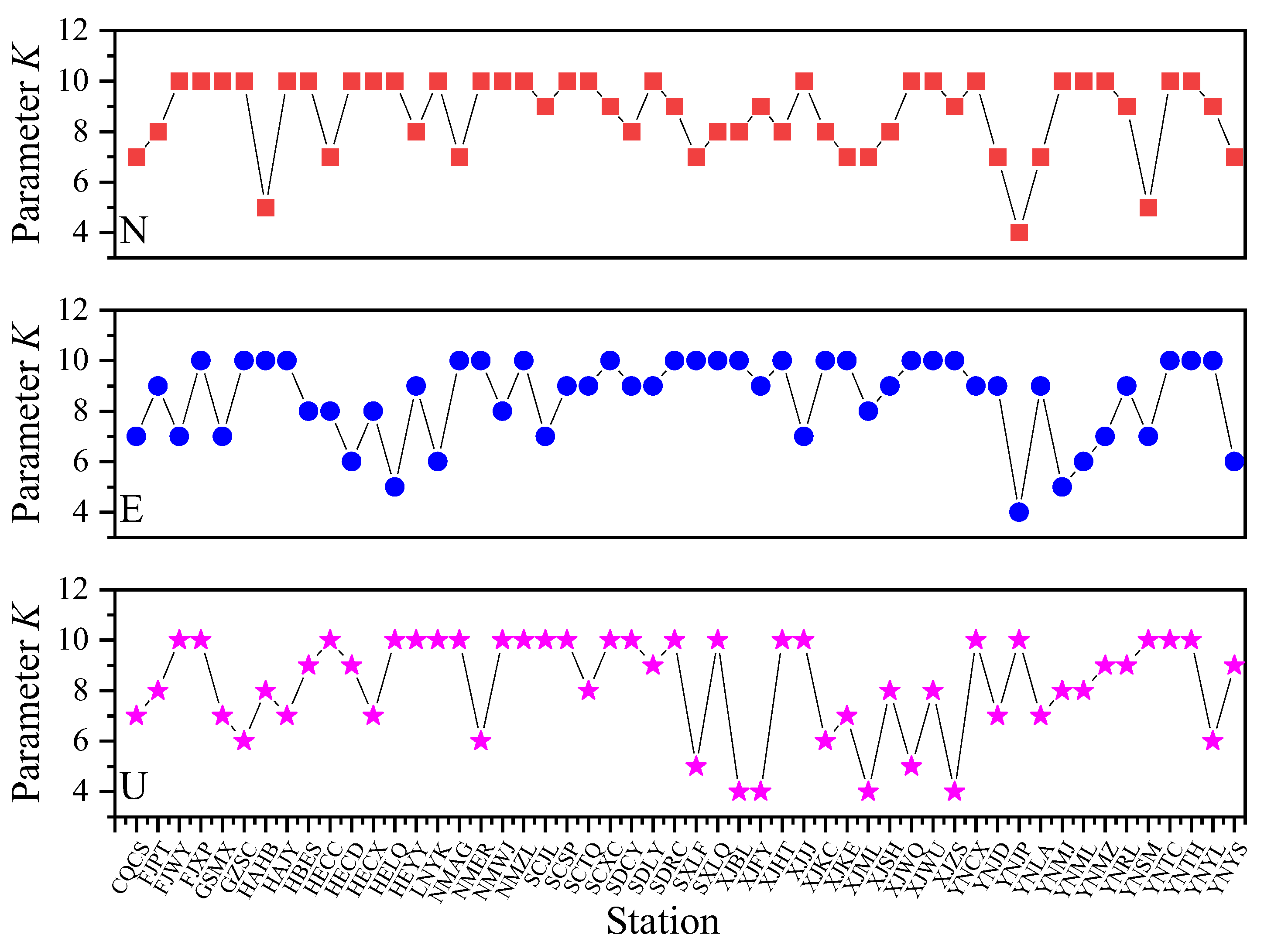

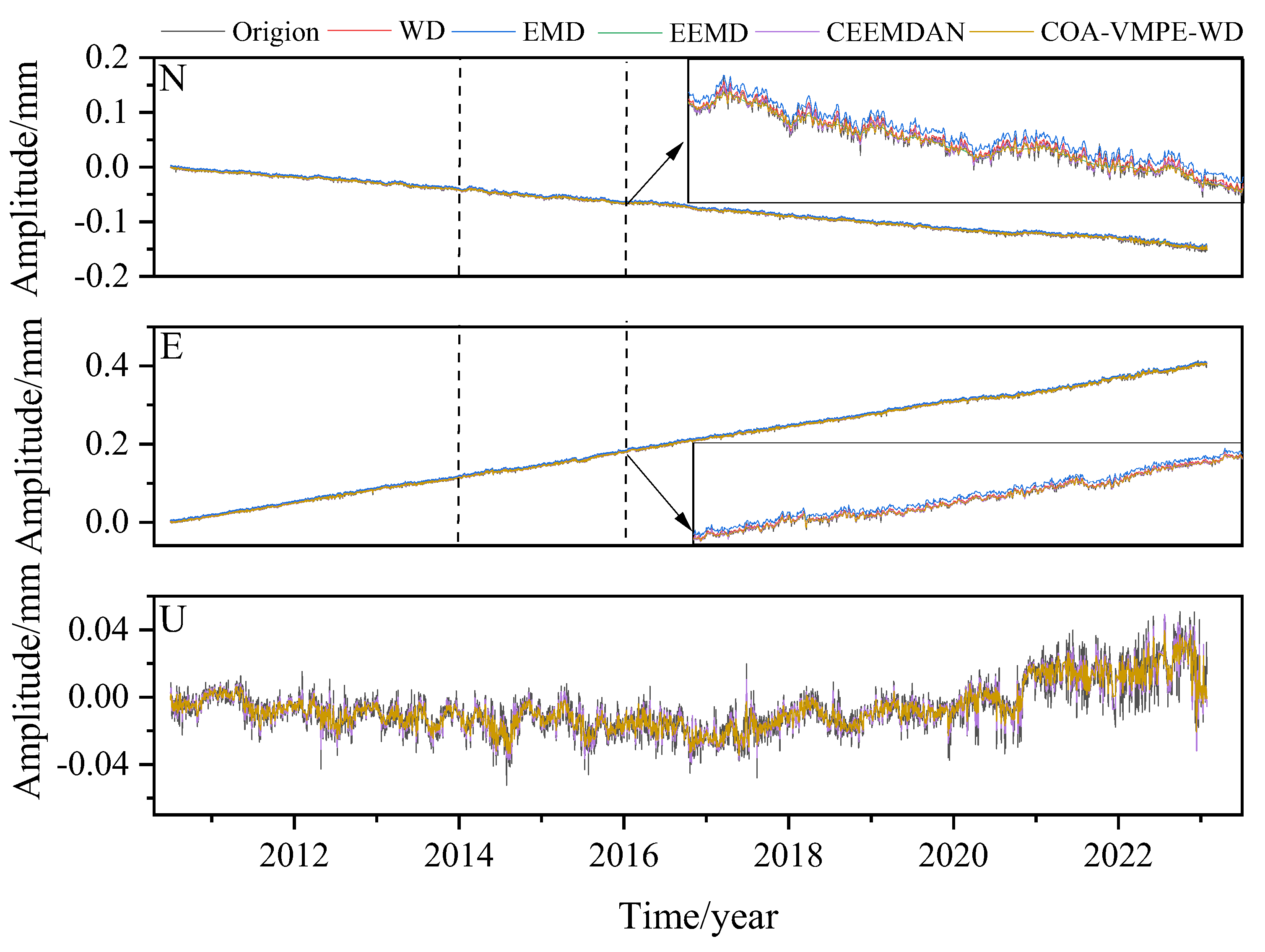

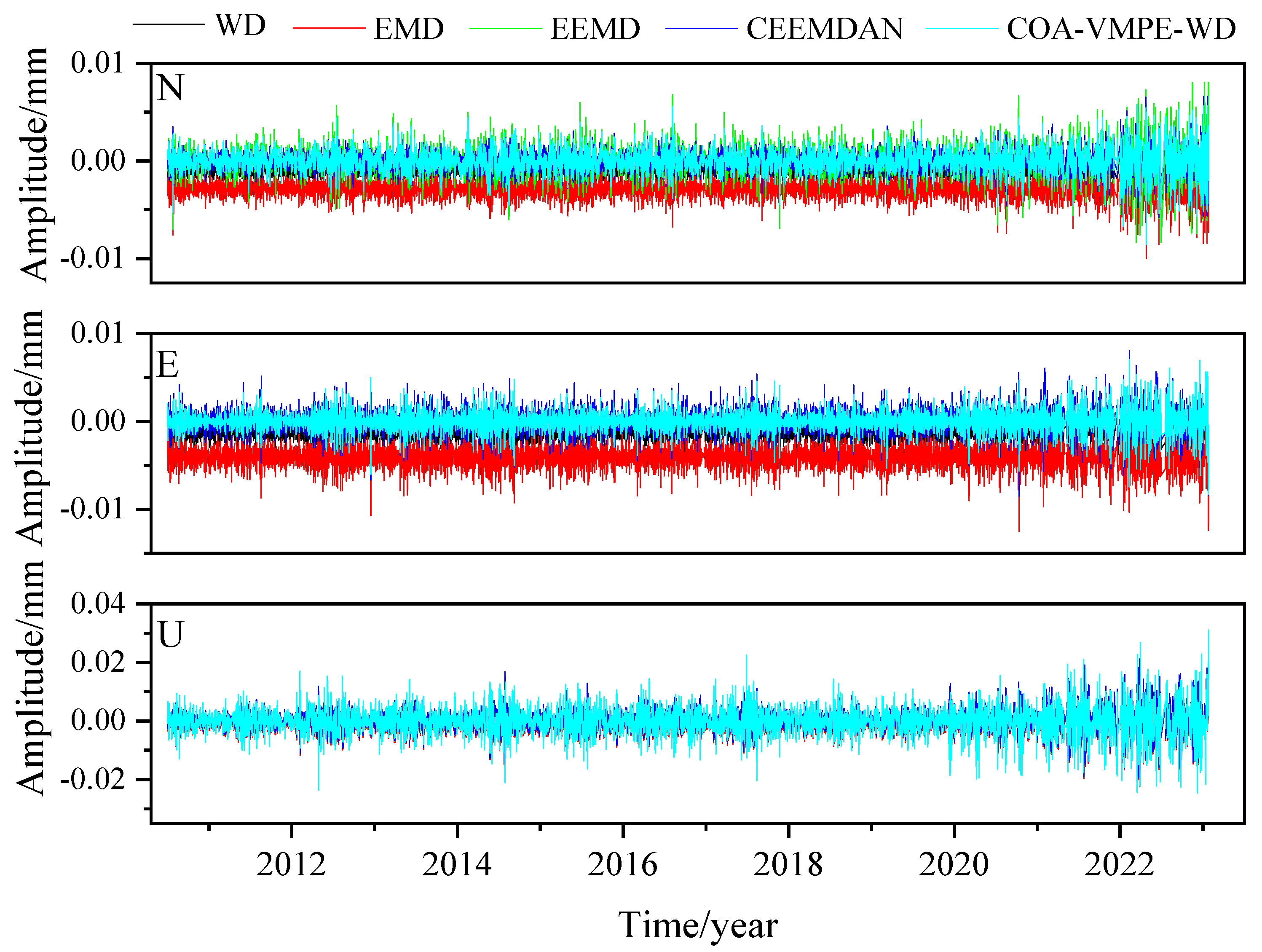

3.3. Application of COA-VMPE-WD for GNSS Time Series Denoising Analysis

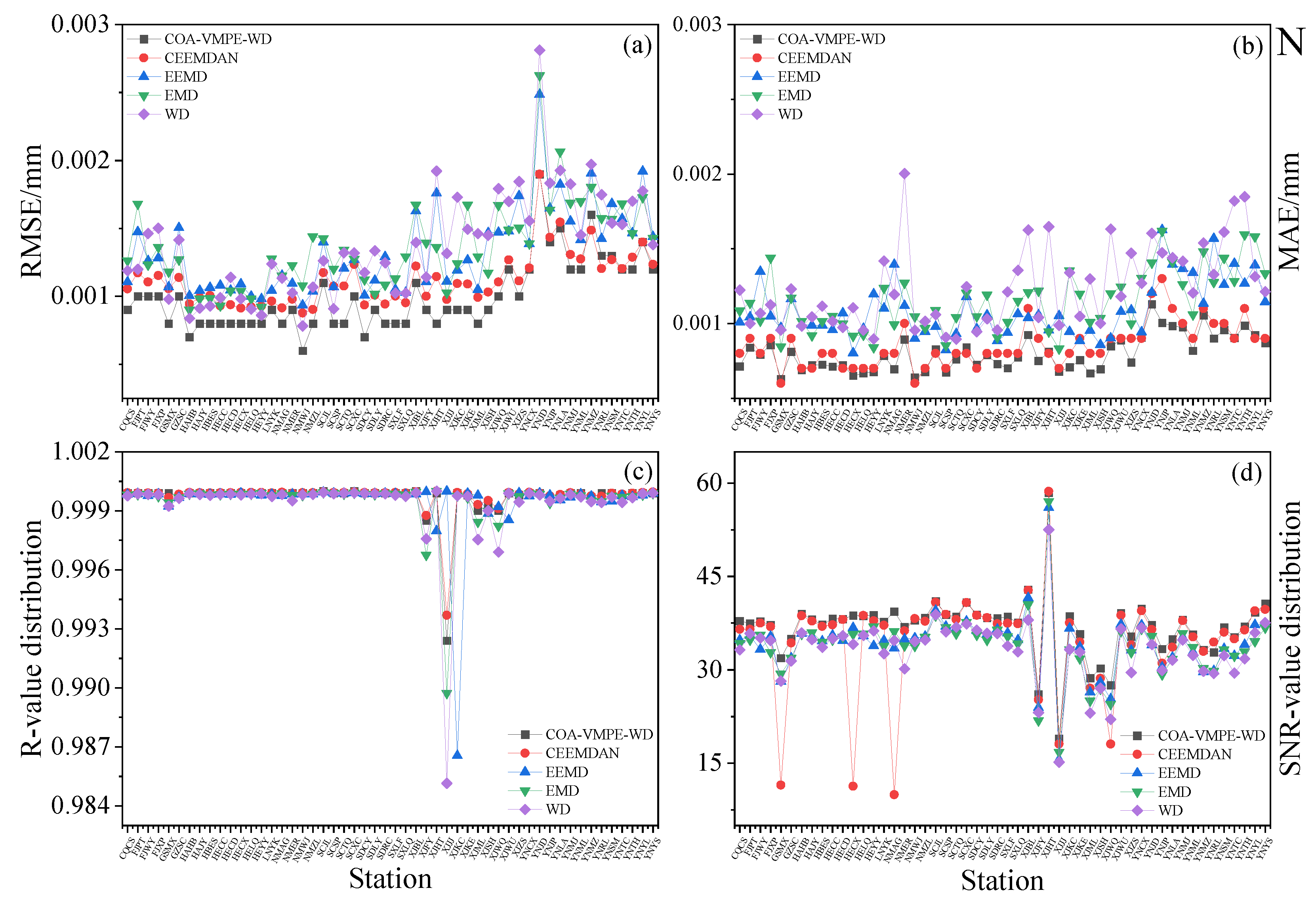

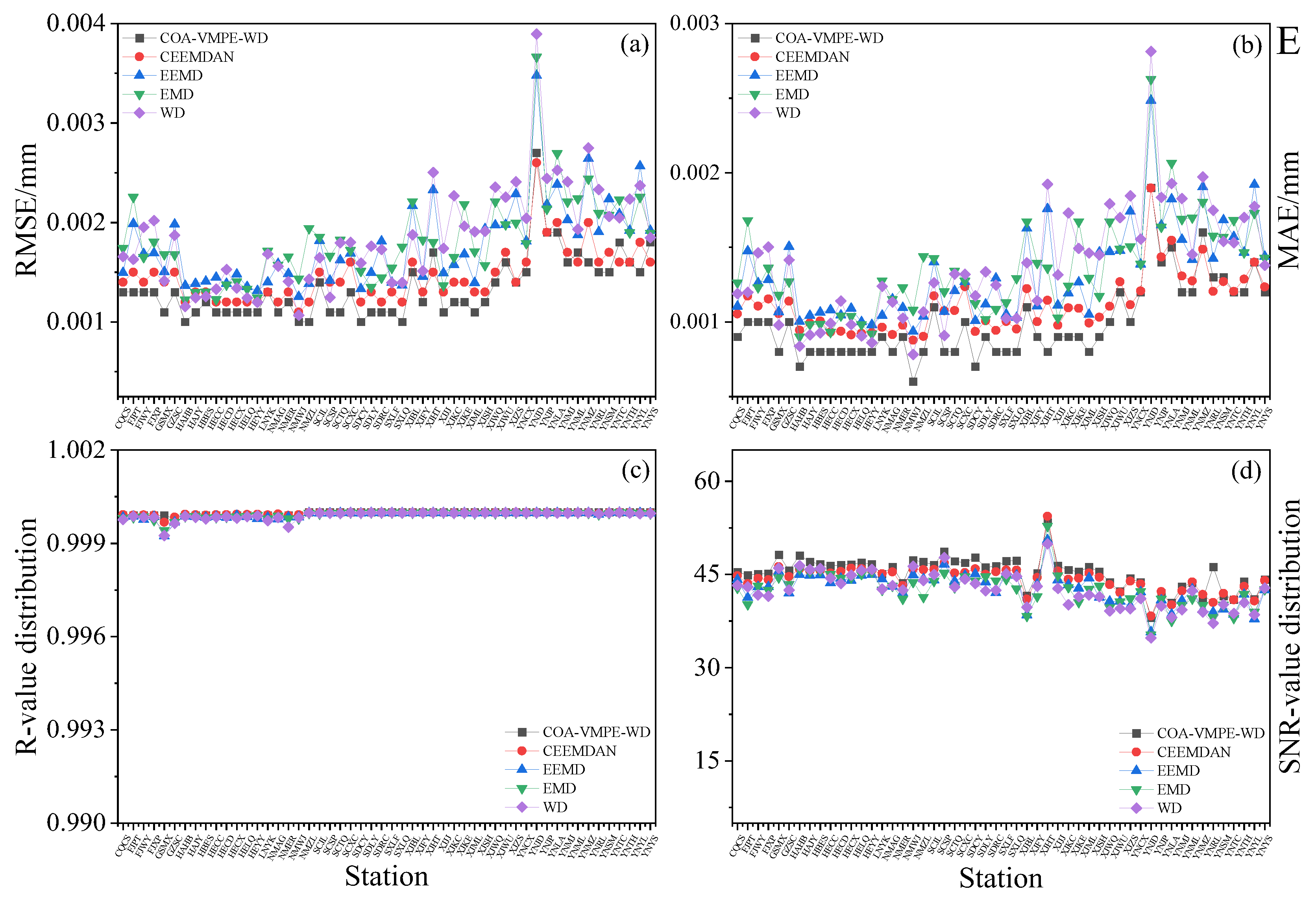

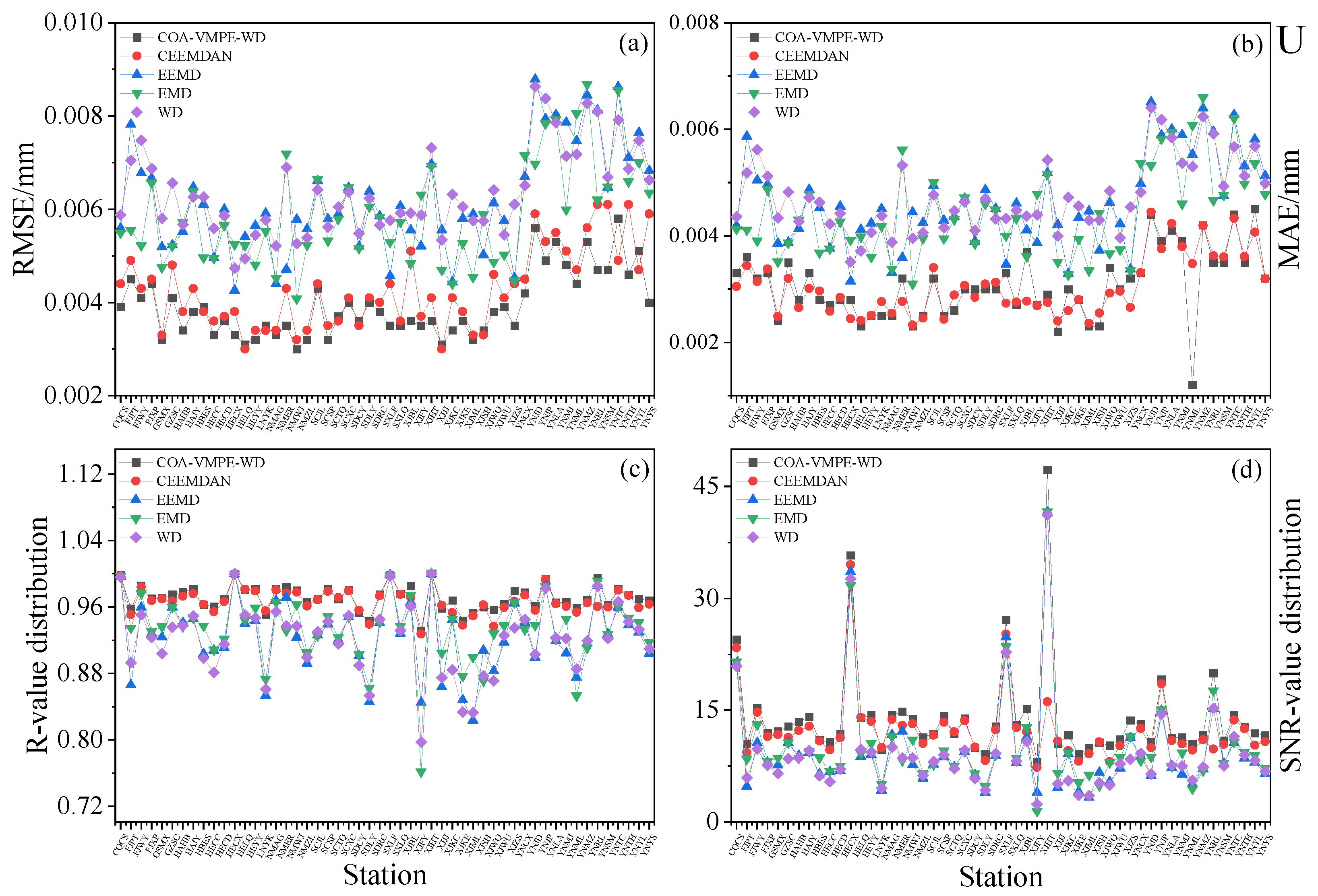

3.4. Comparative Analysis of COA-VMPE-WD

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Optimal Noise Models Using Different Methods

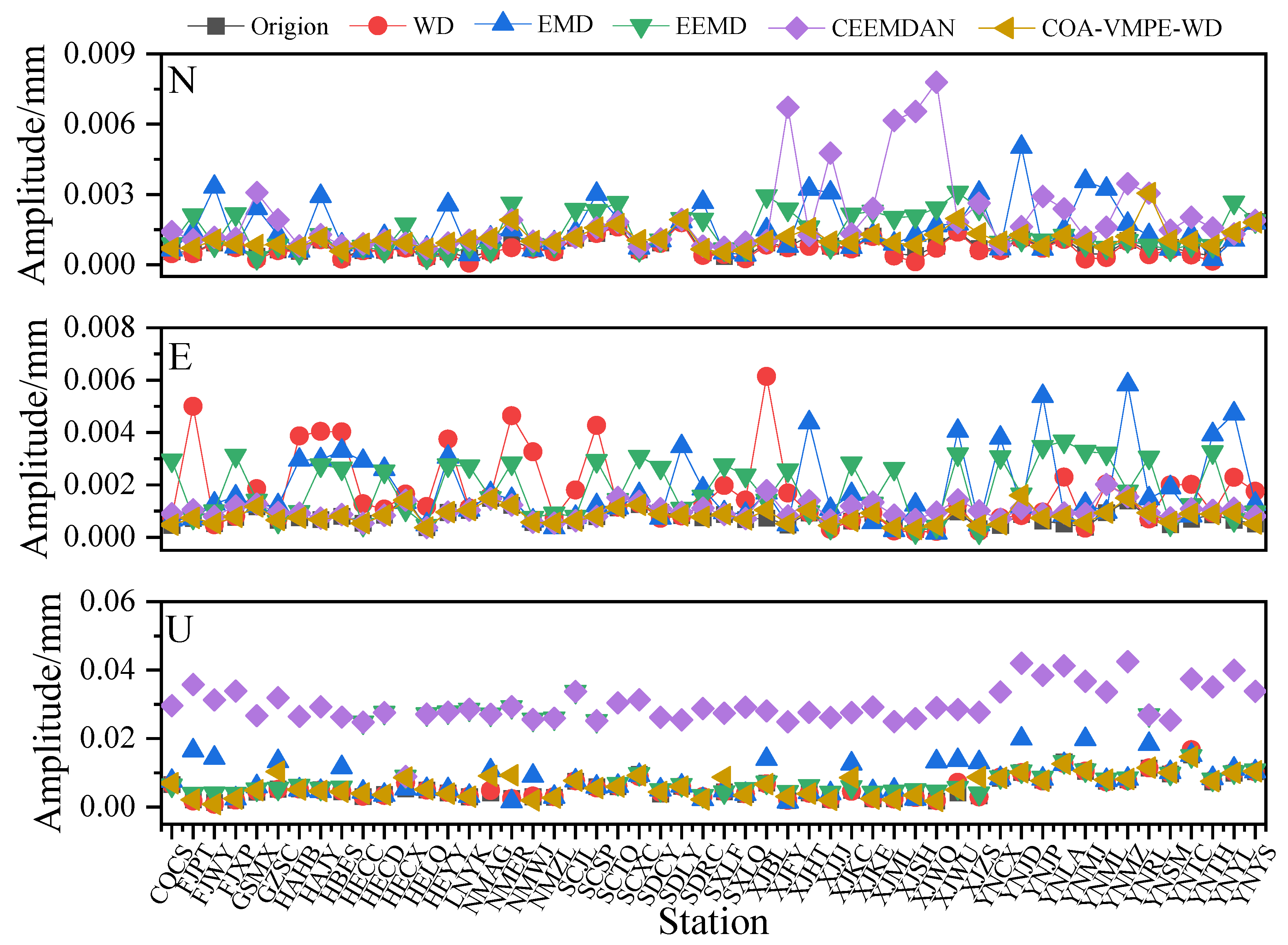

4.2. Analysis of GNSS Station Velocity And Annual Term Using Different Methods

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Simulation signal experiments show that compared to traditional EMD and WD methods, VMD method can effectively alleviate modal aliasing and endpoint effects, and has better signal feature extraction ability. In terms of noise reduction, the COA-VMPE-WD method outperforms the WD, EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN methods in terms of RMSE, R, and SNR evaluation metrics, effectively removing noise from the original data.

- (2)

- Experimental data shows that WD, EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN methods can remove white noise from the original coordinate time series and significantly reduce the amplitude of colored noise. Compared with WD, EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN methods, COA-VMPE-WD has a more significant noise reduction effect and better preserves the characteristics of the original signal.

- (3)

- The WD, EMD, EEMD, CEEMDAN COA-VMPE-WD methods have a significant impact on the U-component in terms of the velocity and uncertainty of the reference station, the COA-VMPE-WD method reduced station velocity by an average of 50.00%, 59.09%, 18.18%, and 64.00% compared to the WD, EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN methods, The noise reduction effect is higher than the other four methods. The above results verify the effectiveness and reliability of the COA-VMPE-WD denoising method. However, the method proposed in this paper reduces computational efficiency to a certain extent. Therefore, further research is needed on how to construct a simple and efficient denoising method based on VMD.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Klos, A. , Bogusz, J., Bos, M. S., & Gruszczynska, M. Modelling the GNSS time series: different approaches to extract seasonal signals. Geodetic time series analysis in earth sciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2019, 211-237.

- Kaczmarek, A. , & Kontny, B. Identification of the noise model in the time series of GNSS stations coordinates using wavelet analysis. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1611. [Google Scholar]

- Montillet, J. P. , Tregoning, P., McClusky, S., & Yu, K. Extracting white noise statistics in GPS coordinate time series. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2012, 10, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. , Bos, M. S., Montillet, J. P., & Fernandes, R. M. S. Investigation of the noise properties at low frequencies in long GNSS time series. Journal of Geodesy 2019, 93, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, K. , Segall, P., & Bradley, A. M. Effects of linear trends on estimation of noise in GNSS position time series. Geophysical Journal International 2016, ggw391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, J. Methods for rapidly estimating velocity precision from GNSS time series in the presence of temporal correlation: a new method and comparison of existing methods. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB019132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoist, C. , Collilieux, X., Rebischung, P., Altamimi, Z., Jamet, O., Métivier, L.,... & Bel, L. Accounting for spatiotemporal correlations of GNSS coordinate time series to estimate station velocities. Journal of Geodynamics 2020, 135, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Gallegos, A. , Borque-Arancón, M. J., & Gil-Cruz, A. J. Present-Day Crustal Velocity Field in Ecuador from GPS Position Time Series. Sensors 2023, 23, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebischung, P. , & Gobron, K. Modeling random isotropic vector fields on the sphere: theory and application to the noise in GNSS station position time series. Journal of Geodesy 2024, 98, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoda, M. , & Rutkowska, M. An analysis of the Eurasian tectonic plate motion parameters based on GNSS stations positions in ITRF2014. Sensors 2020, 20, 6065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jagoda, M. Determination of motion parameters of selected major tectonic plates based on GNSS station positions and velocities in the ITRF2014. Sensors 2021, 21, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. , Yu, K., Montillet, J. P., Xiong, C., Lu, T., Zhou, S.,... & Ming, F. GNSS-TS-NRS: An Open-source MATLAB-Based GNSS time series noise reduction software. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Hou, Z., Xu, K., Hu, X., Gao, X., & Zhang, Z. Noise Reduction of GNSS Coordinate Time Series Based on Adaptive Wavelet Basis Optimization and an Improved Threshold Function. Measurement Science and Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Zhang, S., Dong, Z., Dou, X., Xue, Y., Wang, L.,... & Li, P. Research on GNSS time series noise reduction combining principal component decomposition and compound evaluation index. China Satellite Navigation Conference (CSNC 2021) Proceedings: Volume III. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021; 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , Cao, C. D., Jiang, W. P., & Zhou, L. Elimination of colored noise in GNSS station coordinate time series by using wavelet packet coefficient information entropy. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2021, 46, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, K. , Shen, Y., & Wang, F. Signal extraction from GNSS position time series using weighted wavelet analysis. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. , van Dam, T., Sneeuw, N., Collilieux, X., Weigelt, M., & Rebischung, P. Singular spectrum analysis for modeling seasonal signals from GPS time series. Journal of Geodynamics 2013, 72, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazraei, S. M. , & Amiri-Simkooei, A. R. On the application of Monte Carlo singular spectrum analysis to GPS position time series. Journal of Geodesy 2019, 93, 1401–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. , Li, Z., He, Y., Hou, X., He, Z., & Wang, Q. Extracting of periodic component of GNSS vertical time series using EMD. Sci. Surv. Mapp 2018, 43, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L. , Gao, Y., Jijian, L., Li, F., Gao, X., & Wang, T. Improving GNSS-RTK multipath error extraction with an integrated CEEMDAN and STD-based PCA algorithm. GPS Solutions 2024, 28, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunpu, J. , & Yunzhong, S.. Dyadic wavelet transform and signal extraction of GNSS coordinate time series with missing data. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2020, 49, 537. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D. , Fang, P., Bock, Y., Cheng, M. K., & Miyazaki, S. I. Anatomy of apparent seasonal variations from GPS-derived site position time series. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2002, 107, ETG–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Ding, Z., Li, Y., & Liu, Z. Application of EMD to GNSS time series periodic term processing. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2023, 48, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, J. R. , Shieh, J. S., & Huang, N. E. Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A novel noise enhanced data analysis method. Advances in adaptive data analysis 2010, 2, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka, W. , & Dawid, K. Modeling seasonal oscillations in GNSS time series with Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. GPS Solutions 2022, 26, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K. , & Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE transactions on signal processing 2013, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. , & Guo, J. Extraction of periodic signals in Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) vertical coordinate time series using the adaptive ensemble empirical modal decomposition method. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics 2024, 31, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. , Yan, P., Zhou, H., Huang, Q., Wu, D., Zhu, J., & Ni, Z. Noise reduction and feature enhancement of hob vibration signal based on parameter adaptive VMD and autocorrelation analysis. Measurement Science and Technology 2022, 33, 125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G. , Zhao, Z., Zhang, R., Wang, J., Li, M., Shi, X., & Wang, H. Optimized VMD algorithm for signal noise reduction based on TDLAS. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2024, 312, 108807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. , Cao, S., & Wang, Z. Application of variational mode decomposition to seismic random noise reduction. Journal of Geophysics and Engineering 2017, 14, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Lu, T., Hu, S., Wang, H., Wang, Z., He, X.,... & Zhang, Y. A New Algorithm for Predicting Dam Deformation Using Grey Wolf-Optimized Variational Mode Long Short-Term Neural Network. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. , & Xie, J.Deformation monitoring data de-noising method based on variational mode de-composition combined with sample entropy. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2021, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. , Zhou, X., Zhang, J., Abualigah, L., Yildiz, A. R., & Hussien, A. G Modified crayfish optimization algorithm for solving multiple engineering application problems. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H. , Rao, H., Wen, C., & Mirjalili, S. Crayfish optimization algorithm. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 1919–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, A. E. , Shukla, A. K., Nath, R., Akinyelu, A. A., Agushaka, J. O., Chiroma, H., & Muhuri, P. K. Metaheuristics: a comprehensive overview and classification along with bibliometric analysis. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 4237–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Liu, P., & Li, Y. Implementation of an enhanced crayfish optimization algorithm. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. , Yang, Z., Tian, Z., Yang, B., & Liang, P. Denoising Method for GNSS Time Series Based on GA-VMD and Multi-scale Permutation Entropy. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2023, 48, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Zanin, M. , Zunino, L., Rosso, O. A., & Papo, D. Permutation entropy and its main biomedical and econophysics applications: A review. Entropy 2012, 14, 1553–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. , He, J., He, X., & Tao, R. GNSS coordinate time series denoising method based on parameter-optimized variational mode decomposition. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2024, 49, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Starck, J. L. , Fadili, J., & Murtagh, F. The undecimated wavelet decomposition and its reconstruction. IEEE transactions on image processing 2007, 16, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S. . On the use of the wavelet decomposition for time series prediction. Neurocomputing 2002, 48, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K. , Shen, Y., & Wang, F. Signal extraction from GNSS position time series using weighted wavelet analysis. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 992. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F. E. N. G. , Xiao-dan, S. H. I., Xiao-min, H. U. A. N. G., & Zhi-jie, Z. H. A. N. G. Signal de-noising method based on wavelet decomposition. Journal of Measurement Science & Instrumentation 2014, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Quellec, G. , Lamard, M., Josselin, P. M., Cazuguel, G., Cochener, B., & Roux, C. Optimal wavelet transforms for the detection of microaneurysms in retina photographs. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2008, 27, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Briggs, R. J. Transformation of Small-Signal Energy and Momentum of Waves. Journal of Applied Physics 1964, 35, 3268–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. , He, X., Hu, S., & Ming, F. Impact of offsets on GNSS time series stochastic noise properties and velocity estimation. Advances in Space Research 2025, 75, 3397–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , He, X., Montillet, J. P., Wang, S., Hu, S., Sun, X.,... & Ma, X. An improved ICEEMDAN-MPA-GRU model for GNSS height time series prediction with weighted quality evaluation index. GPS Solutions 2025, 29, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Lu, T., & Wang, Z. Comparative Analysis of Different Deep Learning Algorithms for the Prediction of Marine Environmental Parameters Based on CMEMS Products. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 2024, 21, 343–363. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. , Lu, T., Hu, S., Huang, J., He, X., Montillet, J. P.,... & Huang, Z The relationship of time span and missing data on the noise model estimation of GNSS time series. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. , Yang, Z., Tian, Z., Yang, B., & Liang, p. Denoising Method for GNSS Time Series Based on GA-VMD and Multi-scale Permutation Entropy. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2023, 48, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modal component | IMF1 | IMF2 | IMF3 | IMF4 | IMF5 | IMF6 | IMF7 | IMF8 |

| MPE | 0.4059 | 0.6033 | 0.7113 | 0.7668 | 0.7955 | 0.8085 | 0.8113 | 0.8229 |

| Noise reduction methods | Evaluation | |||

| RMSE/mm | SNR/dB | MAE/mm | R | |

| WD | 1.1971 | 12.8760 | 0.9734 | 0.8777 |

| EMD | 1.3119 | 25.1553 | 0.2329 | 0.9722 |

| EEMD | 1.2384 | 12.8041 | 0.9913 | 0.9300 |

| CEEMDAN | 1.2136 | 13.1049 | 1.0139 | 0.9145 |

| COA-VMPE-WD | 0.2291 | 27.8397 | 0.1780 | 0.9757 |

| Station | N | E | U | Station | N | E | U |

| CQCS | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNWN | SXLF | FNWN | PLWN | FNWN |

| FJPT | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNRWWN | SXLQ | FNWN | PLWN | FNWN |

| FJWY | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNRWWN | XJBL | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN |

| FJXP | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN | XJFY | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| GSMX | FNRWWN | FNRWWN | FNRWWN | XJHT | PLWN | FNWN | PLWN |

| GZSC | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN | XJJJ | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HAHB | FNWN | PLWN | FNRWWN | XJKC | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN |

| HAJY | FNWN | FNWN | FNWN | XJKE | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HBES | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN | XJML | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HECC | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | XJSH | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HECD | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | XJWQ | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HECX | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN | XJWU | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN |

| HELQ | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | XJZS | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| HEYY | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNWN | YNCX | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN |

| LNYK | FNWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNJD | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN |

| NMAG | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNJP | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN |

| NMER | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNLA | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN |

| NMWJ | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNMJ | PLWN | FNWN | PLWN |

| NMZL | FNWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNML | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN |

| SCJL | FNRWWN | FNRWWN | PLWN | YNMZ | FNRWWN | FNWN | FNRWWN |

| SCSP | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNWN | YNRL | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN |

| SCTQ | FNRWWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNSM | FNRWWN | PLWN | PLWN |

| SCXC | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | YNTC | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN |

| SDCY | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN | YNTH | FNWN | FNWN | PLWN |

| SDLY | PLWN | PLWN | FNWN | YNYL | PLWN | FNWN | FNRWWN |

| SDRC | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNWN | YNYS | PLWN | FNWN | FNWN |

| Component | Orgion | WD | EMD | EEMD | CEEMDAN | COA-VMPE-WD |

| N | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN FNRW |

PLWN FNRW |

| E | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN |

| FNRWWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | FNRWWN | FNRW | |

| U | FNRWWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN |

| FNWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | PLWN | FNRW |

| Component | Origin | WD | EMD | EEMD | CEEMDAN | COA-VMPE-WD |

| N | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.010 |

| E | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.018 |

| U | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).