1. Introduction

As a vital natural resource that sustains millions of humans, the coconut tree (Cocos nucifera), which belongs to the palm family, is a prominent player in the small islands of the Pacific [

1]. The tough lignocellulose agricultural waste that constitutes the coconut shell is not edible. Coconut shell makes up 15–20% of the coconut [

2]. One popular way to remove rid of coconut shells is to burn them openly. However, the biocomposites industry can develop new manufacturing methods using coconut shells as a raw material [

3]. These innovative methods can lead to the creation of sustainable products, such as biodegradable packaging and construction materials. By repurposing coconut shells, we not only reduce waste but also promote eco-friendly practices in various industries. Natural-organic fillers are increasingly utilized in the production of polymer composites due to their characteristics, including low density, cost-effectiveness, availability, non-abrasiveness, and renewability [

4,

5,

6,

7].

In 2023, Doss et al. [

8] investigated the impact of varying coconut fiber content (0–50 wt%) on thermoplastic starch/beeswax composites. Results indicated that higher fiber content enhanced thermal stability and mechanical properties. Notably, the composite with 50 wt% coconut fiber exhibited a tensile strength of 20.7 MPa and a flexural strength of 30.3 MPa, demonstrating the potential of coconut fiber as a reinforcement in biodegradable thermoplastic composites. Meanwhile, Jha & Mishra et al. [

9] explored the effects of chemically modifying coconut fibers with alkoxysilanes on poly (lactic acid) (PLA) composites. The study found that silanization improved interfacial bonding, increased crystallinity, and enhanced thermal and dynamic mechanical properties. For instance, the composite with VTMS-modified fibers exhibited a 325% increase in elastic modulus compared to unmodified PLA.In a copolymer of acrylonitrile and butadiene rubber, coconut shell (CS) is a proven cost-effective filler. The composites containing 25 wt% and 50 wt% CS had superior hardness and tensile strength properties compared to those containing 25 wt% of CS [

10].

Kumar & Ramesh et al. [

11] investigated the thermo-mechanical performance of 3D printed coir fiber powder/PLA biocomposites. Specimens containing 0.1–0.5 wt% coir fiber were annealed at 90°C for 120 minutes. The annealed composite with 0.1 wt% coir fiber exhibited a 13.5% higher tensile strength and a 12.7% higher flexural strength than neat PLA, along with improved crystallinity and thermal stability. Singh et al. [

12] developed coir fiber-reinforced composites using glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-functionalized ethylene butylene acrylate (EBA). The study found that the composites exhibited higher tensile properties than pristine EBA, with increased storage and loss moduli. The 30 wt% coir fiber/EBA composite showed the highest tensile strength of 10.93 MPa. These studies underscore the growing interest in utilizing coconut fiber as a sustainable reinforcement in thermoplastic composites, offering enhanced mechanical properties and environmental benefits. To create high-performance composite materials with the best qualities and ensure the wide use of composite materials, further research and development must be done on the combination of CS with other natural fibers. In this sense, CS is a perfect filler material because it is widely accessible, affordable, and abundant [

13].

Previous years, natural resources e.g., oil palm, straw, cornstalk and bagasse have been used for making composites with acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, polypropylene, polyethylene, polyester, polyurethane, polyvinyl acetate, and polylactic acid [

14]. Coconut fiber has been extensively studied in PLA, starch, and EBA matrices, CS has not been adequately explored in a PP matrix. Previous CS composite studies are limited and did not cover thermal and mechanical behavior. Furthermore, limited investigation into how CS affects PP composites specifically, particularly for thermal stability and mechanical reinforcement. Thus, this study’s objective is to investigate how reinforced material affects the mechanical and thermal properties of a CS/ PP composite. Some techniques were used to characterize the properties of the blends including scanning electron microscope (SEM), thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA), tensile testing and flexural testing. It is anticipated that the study’s findings will give researchers and industry practitioners comprehensive information and data on the CS/PP composite, enabling the use of the knowledge gained in a variety of fields, particularly packaging, automotive components, and medical devices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The husk of a coconut and flesh are separated by the coconut shell. A Chinese manufacturer supplied the v PP thermoplastics in granules. To remove the unwanted soluble cellulose, lignin, hemicellulose and moisture, the CS was immersed in water for two days and in a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution for two hours. It then spent a day drying in the sun. 30 wt.% of CS and 70 wt.% of PP were used to create the CS/PP composite. Pre-mixing with a high-speed mixer set to 3000 rpm for five minutes would be the next step. Gotech hot press machines with specialized molds were utilized to obtain tensile and flexural samples in compliance with ASTM D638 and ASTM D790. The CS/PP composite was hot-pressed for 30 minutes at 240°C, and virgin PP was hot-pressed for 20 minutes at 160°C. The next methods were performed the mechanical testing (tensile and flexural), thermal testing and microstructure evaluation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of research methodology for CS/PP composites.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of research methodology for CS/PP composites.

2.2. Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermo-Gravimetric Analyzer was used to generate the thermal analysis data for CS/PP composite. The temperature range for the test was 25°C to 600°C, with the heating rate set at 10°C per minute. The test’s primary objective is to continually assess the material’s weight loss in relationship to temperature and time.

2.3. Mechanical Testing

Figure 2 shows the tensile and flexural tests set-up as per ASTM 638 and ASTM D790. The tests were performed using the universal testing machine (Shimadzu Autograph AGSX, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) at the temperature of 23 °C and relative humidity of 50±5%. Three samples were measured with a 5 kN load cell and 5mm/min crosshead speed. The tensile strength formula can be found in Equation (1), where

A is the material’s initial cross-sectional area,

P is the force needed to break it, and σ

t is the tensile strength. In essence, it determines the stress at which a material will break under a tensile force. The flexural strength and modulus are calculated using Equations (2) and (3), where σ

f indicates the flexural strength, Ef indicates flexural modulus,

S for the dimension between load sites,

b for sample width,

L and

d are length and thickness of support span,

P is load at yield and

t for sample thickness.

2.4. Morphological Analysis

A scanning electron microscope (SEM), model JEOL (JSM-6010PLUS/LV), with platinum coating and 20 kV acceleration, was used to examine the morphology of the CS/PP composite.

2.5. One-way ANOVA

One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significant difference in the main variables. It is used to determine whether the means of two or more independent groups differ significantly when you have a continuous dependent variable and one independent variable with many levels.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Figure 3 shows the TGA results for both the CS/PP composite and plain PP. TGA was used to identify the properties of composite materials that show mass gain or loss primarily as the outcome of oxidation, breakdown, and volatile loss. Each PP and CS/PP composite curve shows an endothermic reaction and a single-stage breakdown. The analysis reveals that the CS/PP composite exhibits enhanced thermal stability compared to plain PP, indicating that the incorporation of fiber significantly influences its degradation behavior. This improved performance suggests potential applications in environments where thermal resistance is crucial. The oil palm fiber composite discovered by Ahmad et al. [

15] displayed a trend that was comparable to the TGA graph. Increasing the temperature in TGA thermograms causes the sample’s weight to decrease due to deterioration. The thermal decomposition temperature rose in tandem with the heating rate. The point at which weight loss abruptly grew was used to determine the degradation temperature. Both the CS/PP and plain PP completely disintegrated down at 600°C and 460°C, respectively, leaving approximately 1.9 and 2.0% residue. The longer it takes to respond, the more filler there is in the composition. This observation highlights the significant influence of filler materials on the thermal stability of the composites. As the filler content increases, the thermal degradation process becomes more complex, potentially leading to variations in both the degradation temperature and the residue left behind after burning.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

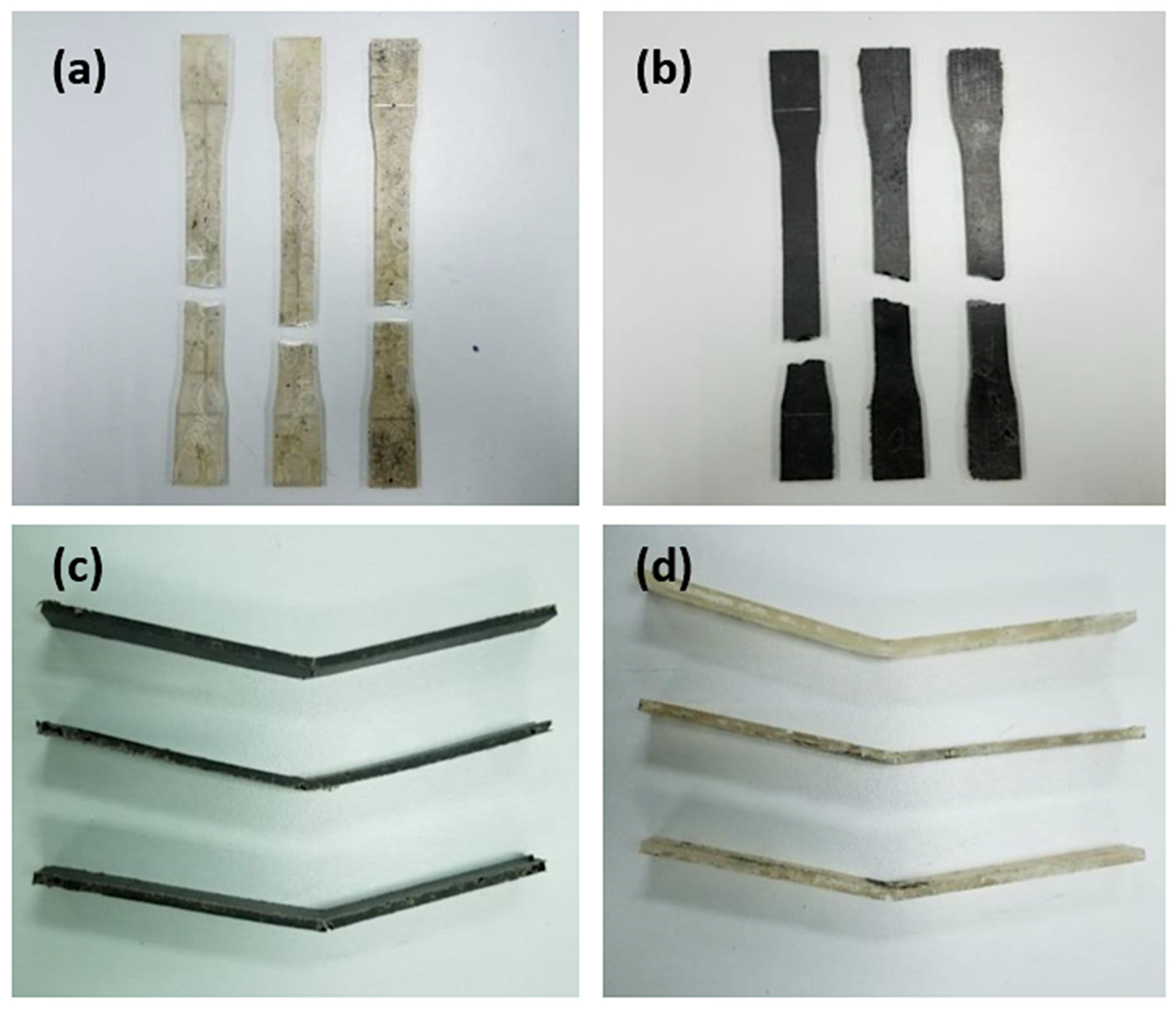

Figure 4 displays the tensile and flexural test samples (post-testing) of the CS/PP composite and pure PP. These tests were carried out to evaluate the mechanical properties of CS/PP composite.

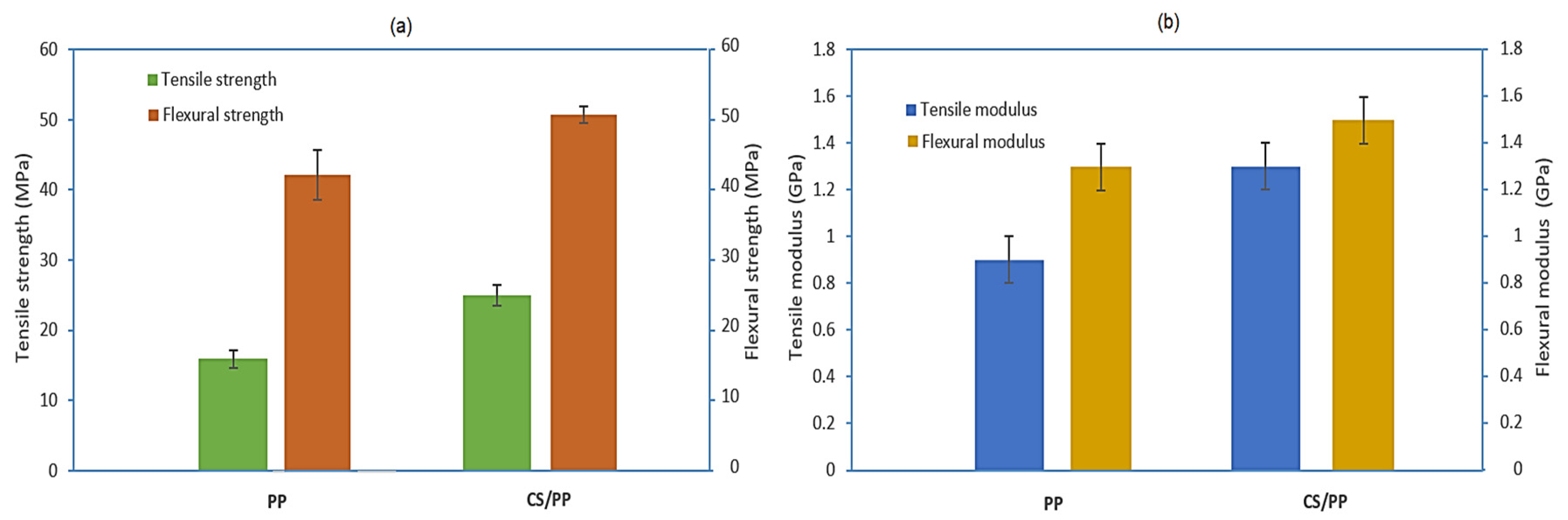

Figure 5a,b show the tensile strength, tensile modulus, flexural strength, and flexural modulus of pure PP and CS/PP composites. The tensile strength and tensile modulus of CS/PP composite had improved 36% and 30%, respectively, when compared to pure PP. Meanwhile, the flexural strength and flexural modulus of CS/PP composite improved 16% and 13%, respectively, when compared to pure PP. As compared to pure PP (0 wt%), the tensile strength for the CS/PP composite was slightly greater. The tensile strength graph and the tensile modulus results show a similar pattern. These enhancements indicate that the incorporation of CS into the PP matrix significantly influences the mechanical properties of the composite. Future studies could explore the effects of varying CS content and processing conditions to further optimize these characteristics. The tensile modulus of oil CS/PP composite increased compared to pure PP. According to Osman and Atia [

16], the maximum flexural stress and Young’s modulus significantly dropped as the percentage of rice straw in the ABS matrix rose. As compared to a previous study by Bledzki [

17], it shows the tensile strength for CS/PP composite varies between 20 and 25 MPa. The tensile result was slightly different from pure PP because they used CS fiber in powder form (100-200 µm). This variation highlights the influence of fiber morphology on mechanical properties. Additionally, it suggests that optimizing the fiber size and distribution could further enhance the performance of CS/PP composites in practical applications.

3.3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

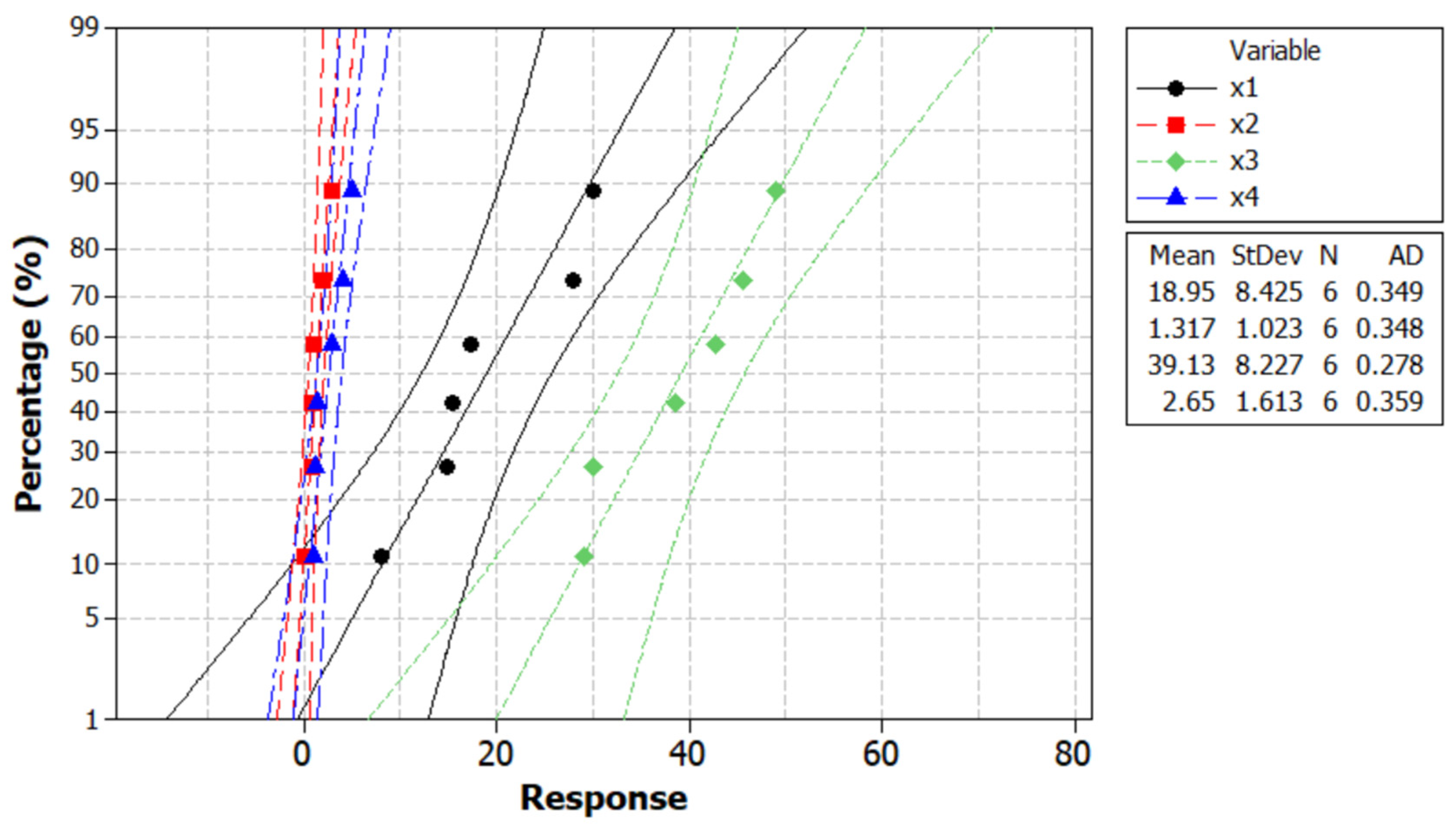

The one-way ANOVA results presented in the

Table 1 evaluates the influence of a single factor (e.g., material type and fiber content) on four responses: tensile strength, tensile modulus, flexural strength, and flexural modulus. Notably, all four properties have

p-values less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences between the groups for each property tested. The flexural modulus stands out with a very high

F-value, indicating a strong effect of the tested factor. The low

p-value confirms this significance with high confidence. This suggests that the material’s stiffness during bending is highly sensitive to the experimental variable, such as fiber reinforcement. For flexural strength the results show the factor significantly affected the bending strength of the samples. This is important in applications where materials undergo bending or flexural loading, indicating improved structural behavior under such stress. Overall, all responses exhibit statistically significant differences, reinforcing the conclusion that the factor studied (e.g., natural fiber reinforcement, filler percentage, etc.) has a consistent and measurable effect on the mechanical performance of the material. The strongest effect is seen on the flexural modulus, followed by moderate effects on tensile and flexural strengths. These findings provide a strong foundation for optimizing the material design, especially for applications that require enhanced stiffness and strength under various loading conditions.

Figure 6 illustrates that the experimental data exhibits strong agreement with the fitted regression line across all measured responses. The low Anderson–Darling (AD) statistics confirm adherence to a normal distribution. Normal probability plots further demonstrate that the residuals are evenly distributed and closely aligned with the reference line, with no observable outliers. This distribution pattern indicates that the error terms are normally and independently distributed, thereby satisfying one of the fundamental assumptions of the regression model. Additionally, the consistent spread of residuals across the experimental runs suggests homoscedasticity, further supporting the validity of the model.

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Figure 6a,b represent the CS/PP composite and pure PP surface morphology respectively. It shows that the surface of pure PP is relatively smooth compared to the CS/PP surface. It is comparable to the findings of Nukala et al. [

18], who discovered that the pure recycling PP had a fine surface microstructure and no distinct characteristics. The virgin PLA surface was smoother than the wood fiber/PLA composite surface [

19]. Nehel et al. [

20] also discovered that the ABS-palm leaf fiber composite surface was rougher than the neat ABS surface. There were some cracks, defects, voids and some damages on the fiber surface. It is due to the presence of inhomogeneous size fiber and larger particles. Hence, it shows the bonding between fiber and thermoplastic matrix was less strong. Furthermore, an agglomeration was seen in the CS/PP composite, and the phase separation shown in both images was further emphasized because of the immiscible polymers [

21]. Young’s modulus, tensile, flexural, and impact strength were among the mechanical performance metrics that were significantly impacted by the quantity of agglomerations. This phenomenon was also observed by Shahar et al. [

15], who conducted research on creating composite filament. They asserted that the PLA composite reinforced with kenaf fibers had a lower tensile strength due to agglomerations in the composite matrix. Obasi et al. [

22] reported the aggregation of coconut shell particles with the matrix. This is feasible because when there is a lot of filler, the fibers tend to not interact with the matrix, which produces holes and gaps.

Figure 7.

SEM micrograph of (a) pure PP, magnification of 100µm (b) CS/PP composite under 100µm magnification (c) pure PP, magnification of 500µm and (d) CS/PP composite, magnification of 500µm.

Figure 7.

SEM micrograph of (a) pure PP, magnification of 100µm (b) CS/PP composite under 100µm magnification (c) pure PP, magnification of 500µm and (d) CS/PP composite, magnification of 500µm.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of utilizing grain by-products, specifically coconut shell (CS), as substitute fillers for reinforcement in composite materials. At the highest test temperature of 260 °C, the CS/PP composite maintained good thermal stability, exhibiting greater resistance to degradation compared to plain PP. Mechanical testing revealed notable improvements over pure PP, with tensile strength and tensile modulus increasing by 36% and 30%, respectively, and flexural strength and flexural modulus increasing by 16% and 13%, respectively. Surface analysis indicated the presence of inhomogeneous regions due to unrefined coconut shell particles. Beyond performance benefits, incorporating agricultural waste such as coconut shell into composites offers a sustainable approach that reduces landfill waste and supports circular economy practices, thereby lowering the environmental footprint of material production. These findings highlight the viability of CS/PP composites for applications in sectors such as automotive components and medical devices. For future work, it is recommended to use coconut shell fiber in finely powdered form as a filler during the compounding process with thermoplastic matrices to enhance uniformity and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.A.; methodology, M.N.A and M.N.P.; software, M.N.A.; validation, M.N.A; formal analysis, M.N.A; investigation, M.N.A and M.N.P.; resources, M.N.A; data curation, M.N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.A.; writing—review and editing, M.N.A.; visualization, M.N.A.; supervision, M.N.A; project administration, M.N.A.; funding acquisition, M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Centre of Research and Innovation Management, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka for supporting this research work. Special appreciation and gratitude to Faculty of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering Technology for giving the full cooperation towards this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS |

Coconut Shell |

| PP |

Polypropylene |

| PLA |

Poly (lactic acid) |

| EBA |

Ethylene Butylene Acrylate |

| GMA |

Glycidyl Methacrylate |

| TGA |

Thermo-gravimetric Analysis |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscope |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| AD |

Anderson–Darling |

References

- Gunasekaran K, Annadurai R and Kumar P. Long term study on compressive and bond strength of coconut shell aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater 2012; 28(1): 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Zohary, D., & Hopf, M. (2000). Domestication of plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of cultivated plants in West Asia, Europe and the Nile Valley (No. Ed. 3). Oxford university press.

- Nadzri, S. N. I. H. A., Sultan, M. T. H., Shah, A. U. M., Safri, S. N. A., Talib, A. R. A., Jawaid, M., & Basri, A. A. (2020). A comprehensive review of coconut shell powder composites: preparation, processing, and characterization. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials. [CrossRef]

- Matuana LM, Balatinecz JJ, Park CB. Effect of surface properties on the adhesion between PVC and wood veneer laminates. Polym Eng Sci 1998; 38: 765–773. [CrossRef]

- Mengeloglu F, Matuana LM, King JA. Effects of impact modifiers on the properties of rigid PVC/wood-fibre composites. J Vinyl Addit Technol 2000; 6: 153–157. [CrossRef]

- Clemons C. Wood-plastic composites in the United States: the interfacing of two industries. For Prod J 2002; 52(6): 10–18.

- Clemons C. Elastomer modified polypropylene–polyethylene blends as matrices for wood flour–plastic composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2010; 41: 1559–1569. [CrossRef]

- Doss, R. M., Muthuraj, R., & Parameswaran, M. (2023). Effect of Coconut Fiber Loading on the Morphological, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties of Coconut Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Starch/Beeswax Composites. Polymers, 15(4), 875.

- Jha, P., & Mishra, D. (2023). Silanized Coconut Fiber Reinforced Poly (lactic acid) Composites: Interfacial Interaction, Crystallinity, and Thermomechanical Properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 140(25), 52816.

- Keerthika, M. Umayavalli, T. Jeyalalitha, N. Krishnaveni, Coconut shell powder as cost effective filler in copolymer of acrylonitrile and butadiene rubber, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 130 (2016) 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Ramesh, K. (2024). Thermo-Mechanical Performance of 3D Printed Coir Fiber/PLA Biocomposites. Polymer Composites, 45(4), 2891-2901.

- Singh, S., & Kumar, R. (2024). Coir Fiber Reinforced Chemically Functionalized Ethylene Butylene Acrylate Composites: A Study on Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Polymer Engineering & Science, 64(1), 47-57.

- M.T. Islam, S.C. Das, J. Saha, D. Paul, M.T. Islam, M. Rahman, M.A. Khan, Effect of coconut shell powder as filler on the mechanical properties of coir–polyester composites, Chem. Mater. Eng. 5 (4) (2017) 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. N., Ishak, M. R., Taha, M. M., Mustapha, F., & Leman, Z. (2023). Finite element analysis of oil palm fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites for fused deposition modeling. Materials Today: Proceedings, 74, 509-512. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. N., Ishak, M. R., Taha, M. M., Mustapha, F., & Leman, Z. (2023). Mechanical, thermal and physical characteristics of oil palm (Elaeis Guineensis) fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites for FDM–Type 3D printer. Polymer Testing, 120, 107972. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Osman, M.R.A. Atia., Investigation of ABS-rice straw composite feedstock filament for FDM Rapid Prototyp. J., 24 (2018), pp. 1067-1075.

- Bledzki, A. K., Mamun, A. A., & Volk, J. (2010). Barley husk and coconut shell reinforced polypropylene composites: the effect of fibre physical, chemical and surface properties. Composites Science and Technology, 70(5), 840-846. [CrossRef]

- S.G. Nukala, I. Kong, A.B. Kakarla, K.Y. Tshai, W. Kong. Preparation and characterisation of wood polymer composites using sustainable raw materials Polymers, 14 (15) (2022), p. 3183. [CrossRef]

- R. Guo, Z. Ren, H. Bi, Y. Song, M. Xu. Effect of toughening agents on the properties of poplar wood flour/poly (lactic acid) composites fabricated with Fused Deposition Modeling Eur. Polym. J., 107 (2018), pp. 34-45. [CrossRef]

- B. Neher, M.A. Gafur, M.A. Al-Mansur, M.M.R. Bhuiyan, M.R. Qadir, F. Ahmed. Investigation of the surface morphology and structural characterization of palm fiber reinforced acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (PF-ABS) composites, Mater. Sci. Appl., 5 (2014), pp. 378-386. [CrossRef]

- H. Bi, Z. Ren, R. Guo, M. Xu, Y. Song. Fabrication of flexible wood flour/thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer composites using fused deposition molding., Ind. Crop. Prod., 122 (2018), pp. 76-84 . [CrossRef]

- Obasi, H. C., Mark, U. C., & Mark, U. (2021). Improving the mechanical properties of polypropylene composites with coconut shell particles. Composites and Advanced Materials, 30, 26349833211007497. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).