Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

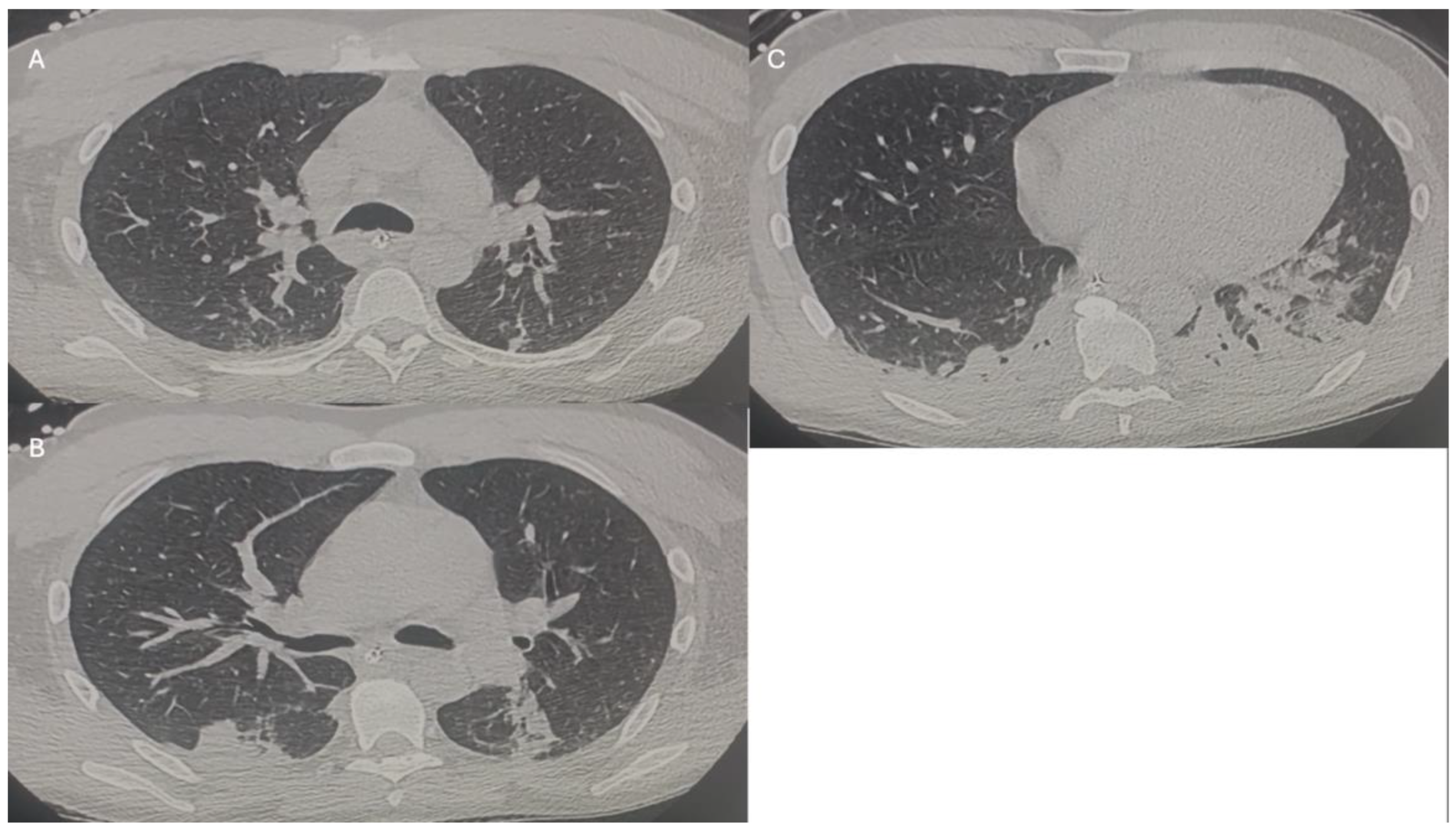

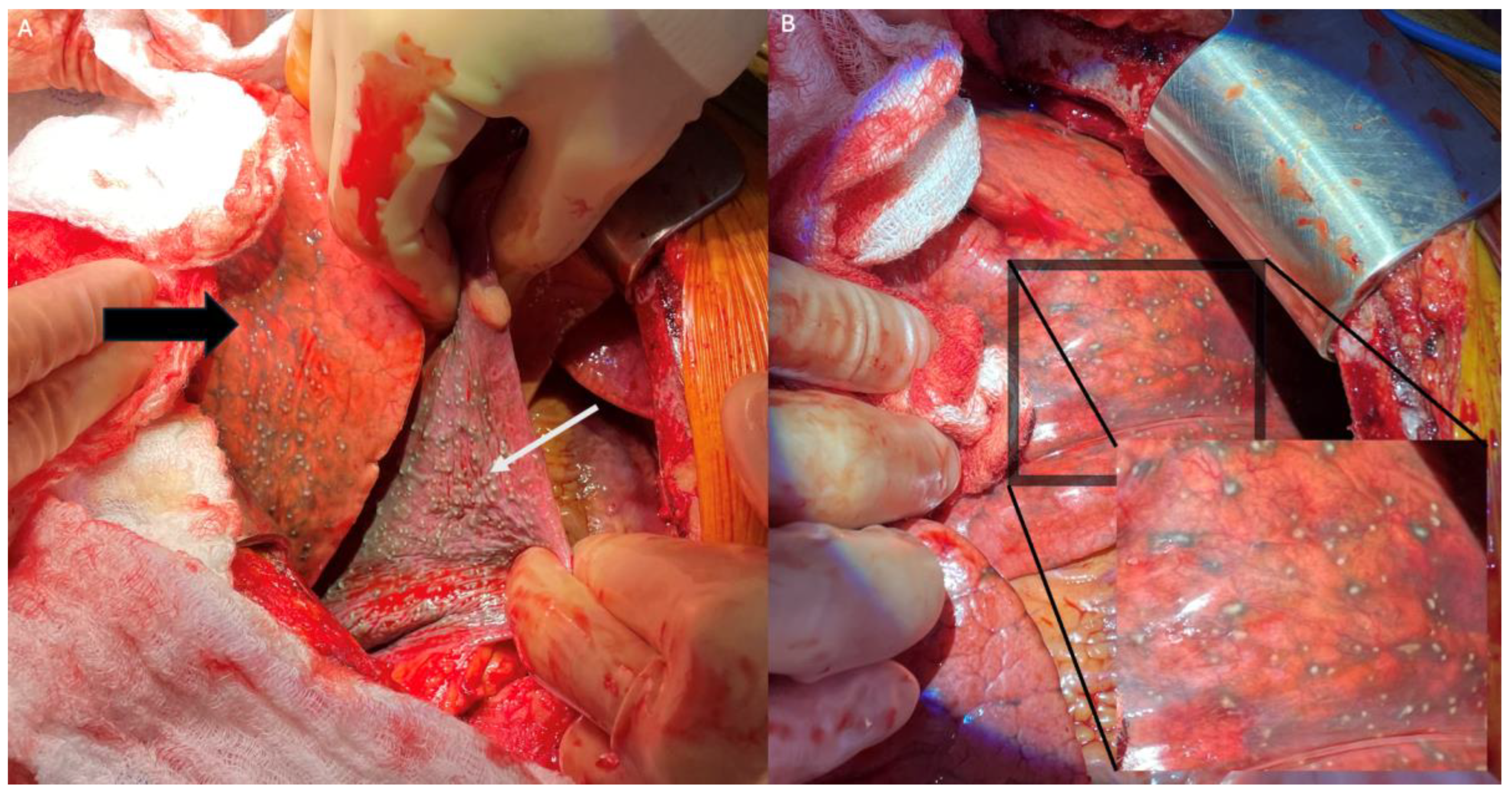

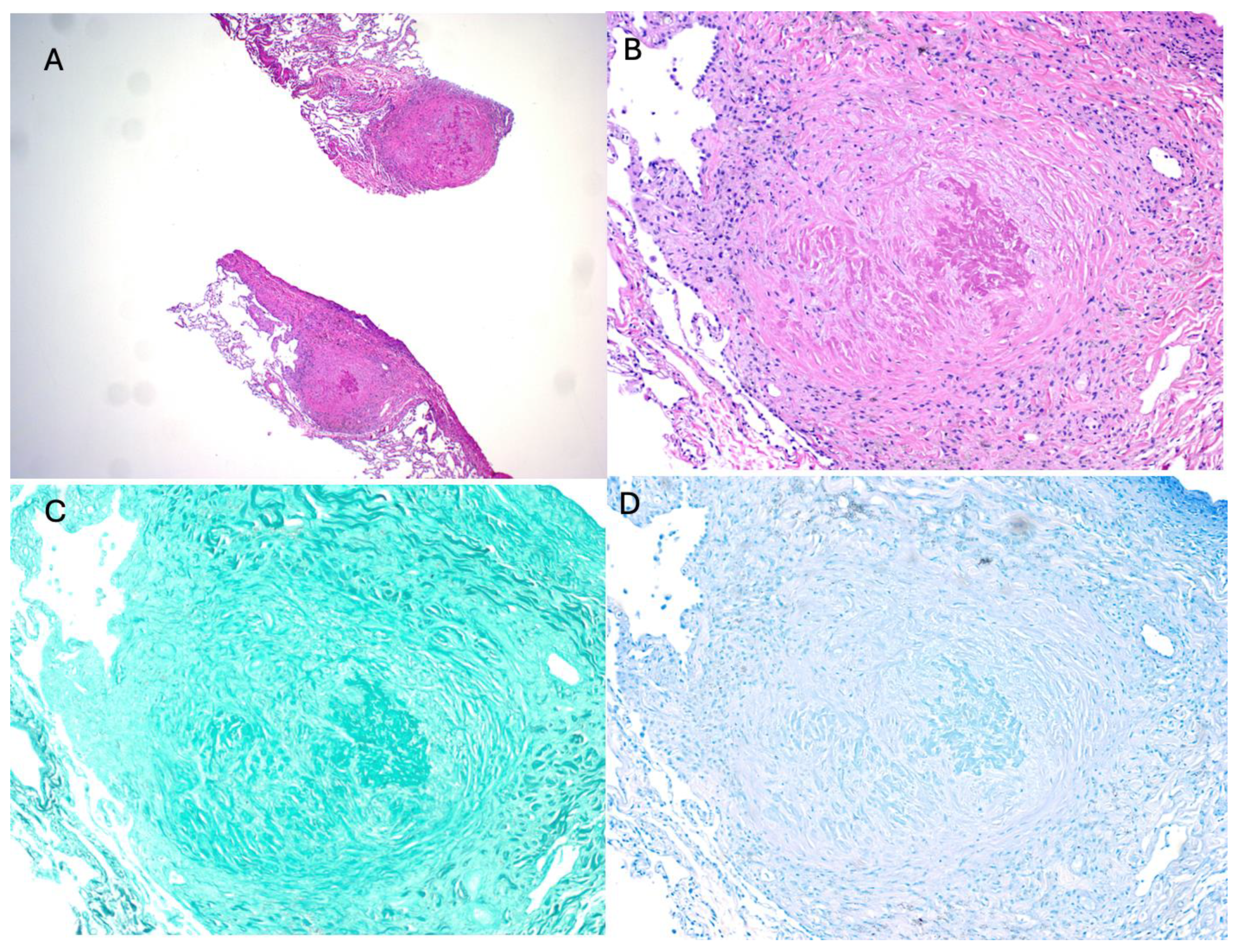

2. Index Case

3. Sarcoidosis: Complexity in Diagnosis and Pathogenesis

4. Occupational Exposure to Silica: A Rising Concern and Possibly an Inducer of Sarcoidosis

5. Transplantation: Unexpected Challenges in Organ Donation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Authorship

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Statement

Abbreviation Page:

References

- Grunewald J: Grutters JC, Arkema EV, et al. Sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):45.

- Lin NW, Maier LA. Occupational exposures and sarcoidosis: current understanding and knowledge gaps. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2022;28(2):144-51. [CrossRef]

- Fazio JC, Gandhi SA, Flattery J, et al. Silicosis Among Immigrant Engineered Stone (Quartz) Countertop Fabrication Workers in California. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):991-8.

- Kramer MR, Blanc PD, Fireman E, et al. Artificial stone silicosis [corrected]: disease resurgence among artificial stone workers. Chest. 2012;142(2):419-24.

- Oliver LC, Sampara P, Pearson D, et al. Sarcoidosis in Northern Ontario hard-rock miners: A case series. Am J Ind Med. 2022;65(4):268-80. [CrossRef]

- Quero A, Urrutia C, Martinez C, et al. [Silicosis and sarcoid pulmonary granulomas, silicosarcoidosis?]. Med Clin (Barc). 2002;118(2):79.

- Arkema EV, Grunewald J, Kullberg S, et al. Sarcoidosis incidence and prevalence: a nationwide register-based assessment in Sweden. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(6):1690-9.

- Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: recent estimates of incidence, prevalence and risk factors. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(5):527-34.

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis Based on Health Care Use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1244-52.

- Brito-Zerón P, Kostov B, Superville D, et al. Geoepidemiological big data approach to sarcoidosis: geographical and ethnic determinants. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(6):1052-64.

- Fidler LM, Balter M, Fisher JH, et al. Epidemiology and health outcomes of sarcoidosis in a universal healthcare population: a cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(4). [CrossRef]

- Hena KM. Sarcoidosis Epidemiology: Race Matters. Front Immunol. 2020;11:537382.

- Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(3):234-41. [CrossRef]

- Drent M, Crouser ED, Grunewald J. Challenges of Sarcoidosis and Its Management. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385(11):1018-32.

- Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(11):2085-91.

- Rossides M, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Familial aggregation and heritability of sarcoidosis: a Swedish nested case-control study. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(2).

- Sverrild A, Backer V, Kyvik KO, et al. Heredity in sarcoidosis: a registry-based twin study. Thorax. 2008;63(10):894-6.

- Rivera NV, Ronninger M, Shchetynsky K, et al. High-Density Genetic Mapping Identifies New Susceptibility Variants in Sarcoidosis Phenotypes and Shows Genomic-driven Phenotypic Differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):1008-22.

- Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, et al. HLA-DRB1*1101: a significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(4):720-35.

- Schurmann M, Reichel P, Muller-Myhsok B, et al. Results from a genome-wide search for predisposing genes in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(5):840-6.

- Berlin M, Fogdell-Hahn A, Olerup O, et al. HLA-DR predicts the prognosis in Scandinavian patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1601-5. [CrossRef]

- Fischer A, Nothnagel M, Schurmann M, et al. A genome-wide linkage analysis in 181 German sarcoidosis families using clustered biallelic markers. Chest. 2010;138(1):151-7. [CrossRef]

- Fischer A, Rybicki BA. Granuloma genes in sarcoidosis: what is new? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21(5):510-6.

- Fischer A, Schmid B, Ellinghaus D, et al. A novel sarcoidosis risk locus for Europeans on chromosome 11q13.1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):877-85.

- Hofmann S, Fischer A, Nothnagel M, et al. Genome-wide association analysis reveals 12q13.3-q14.1 as new risk locus for sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(4):888-900. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann S, Franke A, Fischer A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies ANXA11 as a new susceptibility locus for sarcoidosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1103-6. [CrossRef]

- Martinetti M, Tinelli C, Kolek V, et al. "The sarcoidosis map": a joint survey of clinical and immunogenetic findings in two European countries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(2):557-64.

- Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37(4):357-64.

- Crouser ED, Culver DA, Knox KS, Julian MW, Shao G, Abraham S, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies MMP-12 and ADAMDEC1 as potential pathogenic mediators of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(10):929-38. [CrossRef]

- Lockstone HE, Sanderson S, Kulakova N, et al. Gene set analysis of lung samples provides insight into pathogenesis of progressive, fibrotic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(12):1367-75.

- Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):e26-e51.

- Grunewald J, Eklund A. Sex-specific manifestations of Lofgren's syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):40-4. [CrossRef]

- Poate TW, Sharma R, Moutasim KA, et al. Orofacial presentations of sarcoidosis--a case series and review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2008;205(8):437-42.

- Rosen Y. Four decades of necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis: what do we know now? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):252-62. [CrossRef]

- Spiteri MA, Matthey F, Gordon T, et al. Lupus pernio: a clinico-radiological study of thirty-five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112(3):315-22.

- Binesh F, Halvani H, Navabii H. Systemic sarcoidosis with caseating granuloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012.

- Ma Y, Gal A, Koss MN. The pathology of pulmonary sarcoidosis: update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24(3):150-61.

- Rossi G, Cavazza A, Colby TV. Pathology of Sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49(1):36-44.

- Soler P, Basset F. Morphology and distribution of the cells of a sarcoid granuloma: ultrastructural study of serial sections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:147-60. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Wilcox BE, Myers JL, et al. Pulmonary necrotizing granulomas of unknown cause: clinical and pathologic analysis of 131 patients with completely resected nodules. Chest. 2013;144(3):813-24.

- Buk SJ. Simultaneous demonstration of connective tissue elastica and fibrin by a combined Verhoeff's elastic-Martius-scarlet-blue trichrome stain. Stain Technol. 1984;59(1):1-5.

- Sakthivel P, Bruder D. Mechanism of granuloma formation in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2017;24(1):59-65. [CrossRef]

- Silva E, Souchelnytskyi S, Kasuga K, et al. Quantitative intact proteomics investigations of alveolar macrophages in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1331-9.

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101-17.

- Huntley CC, Patel K, Mughal AZ, et al. Airborne occupational exposures associated with pulmonary sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2023;80(10):580-9.

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(12):1324-30.

- Kucera GP, Rybicki BA, Kirkey KL, et al. Occupational risk factors for sarcoidosis in African-American siblings. Chest. 2003;123(5):1527-35.

- Beijer E, Meek B, Kromhout H, et al. Sarcoidosis in a patient clinically diagnosed with silicosis; is silica associated sarcoidosis a new phenotype? Respir Med Case Rep. 2019;28:100906. [CrossRef]

- Kawano-Dourado LB, Carvalho CR, Santos UP, Canzian M, Coletta et al. Tunnel excavation triggering pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(4):390-4.

- Ronsmans S, Verbeken EK, Adams E, et al. Granulomatous lung disease in two workers making light bulbs. Am J Ind Med. 2019;62(10):908-13.

- Uzmezoglu B, Simsek C, Gulgosteren S, et al. Sarcoidosis in iron-steel industry: mini case series. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34(4):365-72.

- Mochizuka Y, Kono M, Katsumata M, et al. Sarcoid-like Granulomatous Lung Disease with Subacute Progression in Silicosis. Intern Med. 2022;61(3):395-400. [CrossRef]

- Carreno Hernandez MC, Garrido Paniagua S, Colomes Iess M, et al. Accelerated silicosis with bone marrow, hepatic and splenic involvement in a patient with lung transplantation. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(12).

- Vihlborg P, Bryngelsson IL, Andersson L, et al. Risk of sarcoidosis and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis from occupational silica exposure in Swedish iron foundries: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e016839.

- Graff P, Larsson J, Bryngelsson IL, et al. Sarcoidosis and silica dust exposure among men in Sweden: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e038926.

- Jonsson E, Jarvholm B, Andersson M. Silica dust and sarcoidosis in Swedish construction workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2019;69(7):482-6.

- Nathan N, Montagne ME, Macchi O, et al. Exposure to inorganic particles in paediatric sarcoidosis: the PEDIASARC study. Thorax. 2022;77(4):404-7. [CrossRef]

- Rezai M, Nayebzadeh A, Catli S, et al. Occupational exposures and sarcoidosis: a rapid review of the evidence. Occup Med (Lond). 2024;74(4):266-73.

- Worker Exposure to Silica during Countertop Manufacturing, Finishing and Installation [Available from: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OSHA3768.pdf.

- Silicosis, mortality, prevention and control—United States, 1968–2002. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/ mmwrhtml/mm5416a2.htm.

- Barnes H, Goh NSL, Leong TL, et al. Silica-associated lung disease: An old-world exposure in modern industries. Respirology. 2019;24(12):1165-75.

- Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):2008-18.

- Wu N, Xue C, Yu S, Y et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis in China: A prospective comparison with natural stone-associated silicosis. Respirology. 2020;25(5):518-24.

- Chaney J, Suzuki Y, Cantu E, 3rd, et al. Lung donor selection criteria. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(8):1032-8.

- Kotloff RM, Blosser S, Fulda GJ, et al. Management of the Potential Organ Donor in the ICU: Society of Critical Care Medicine/American College of Chest Physicians/Association of Organ Procurement Organizations Consensus Statement. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(6):1291-325.

- Aigner C, Winkler G, Jaksch P, et al. Extended donor criteria for lung transplantation--a clinical reality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27(5):757-61. [CrossRef]

- Lardinois D, Banysch M, Korom S, et al. Extended donor lungs: eleven years experience in a consecutive series. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27(5):762-7.

- Mulligan MJ, Sanchez PG, Evans CF, et al. The use of extended criteria donors decreases one-year survival in high-risk lung recipients: A review of the United Network of Organ Sharing Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(3):891-8 e2.

- Sommer W, Kuhn C, Tudorache I, et al. Extended criteria donor lungs and clinical outcome: results of an alternative allocation algorithm. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(11):1065-72.

- Whiting D, Banerji A, Ross D, et al. Liberalization of donor criteria in lung transplantation. Am Surg. 2003;69(10):909-12.

- Committee JUKUBTaTTSPA. Sarcoidosis [Available from: https://www.transfusionguidelines.org/dsg/wb/guidelines/sa004-sarcoidosis#:~:text=Must%20not%20donate.&text=Chronic%20Sarcoidosis%20can%20cause%20a,this%20condition%20should%20not%20donate.

- Burke WM, Keogh A, Maloney PJ, et al. Transmission of sarcoidosis via cardiac transplantation. Lancet. 1990;336(8730):1579.

- Heatly T, Sekela M, Berger R. Single lung transplantation involving a donor with documented pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13(4):720-3.

- Padilla ML, Schilero GJ, Teirstein AS. Donor-acquired sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2002;19(1):18-24.

- Kono M, Hasegawa J, Wakai S, et al. Living Kidney Donation From a Donor With Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Transplant Proc. 2017;49(5):1183-6.

- Milman N, Andersen CB, Burton CM, et al. Recurrent sarcoid granulomas in a transplanted lung derive from recipient immune cells. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):549-52. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu DN, Hunt JL, Lomago D, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in lung transplant allografts: granulomas are of recipient origin. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2005;14(3):140-5.

- Schultz HH, Andersen CB, Steinbruuchel D, et al. Recurrence of sarcoid granulomas in lung transplant recipients is common and does not affect overall survival. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(2):149-53.

- Churg A, Muller NL. Update on Silicosis. Surg Pathol Clin. 2024;17(2):193-202.

- Tomic D, Hoy RF, Sin J, et al. Autoimmune diseases, autoantibody status and silicosis in a cohort of 1238 workers from the artificial stone benchtop industry. Occup Environ Med. 2024;81(8):388-94. [CrossRef]

- Shtraichman O, Blanc PD, Ollech JE, et al. Outbreak of autoimmune disease in silicosis linked to artificial stone. Occup Med (Lond). 2015;65(6):444-50.

- Liu Y, Rong Y, Steenland K, et al. Long-term exposure to crystalline silica and risk of heart disease mortality. Epidemiology. 2014;25(5):689-96.

- Chakraborty P, Isser HS, Arava SK, et al. Ventricular Tachycardia: A Rare Case of Myocardial Silicosis. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2(14):2256-9.

- Jiang Y, Shao F. A stone miner with both silicosis and constrictive pericarditis: case report and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:71. [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani N. Silica nephropathy. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2010;1(3):108-15.

- Millerick-May ML, Schrauben S, Reilly MJ, et al. Silicosis and chronic renal disease. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(7):730-6.

- Rosenman KD, Moore-Fuller M, Reilly MJ. Kidney disease and silicosis. Nephron. 2000;85(1):14-9.

- Steenland K, Rosenman K, Socie E, et al. Silicosis and end-stage renal disease. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(6):439-42.

- Zawilla N, Taha F, Ibrahim Y. Liver functions in silica-exposed workers in Egypt: possible role of matrix remodeling and immunological factors. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2014;20(2):146-56. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad K, Pluhacek JL, Brown AW. Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion: A Review of Current and Future Application in Lung Transplantation. Pulm Ther. 2022;8(2):149-65.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).