Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

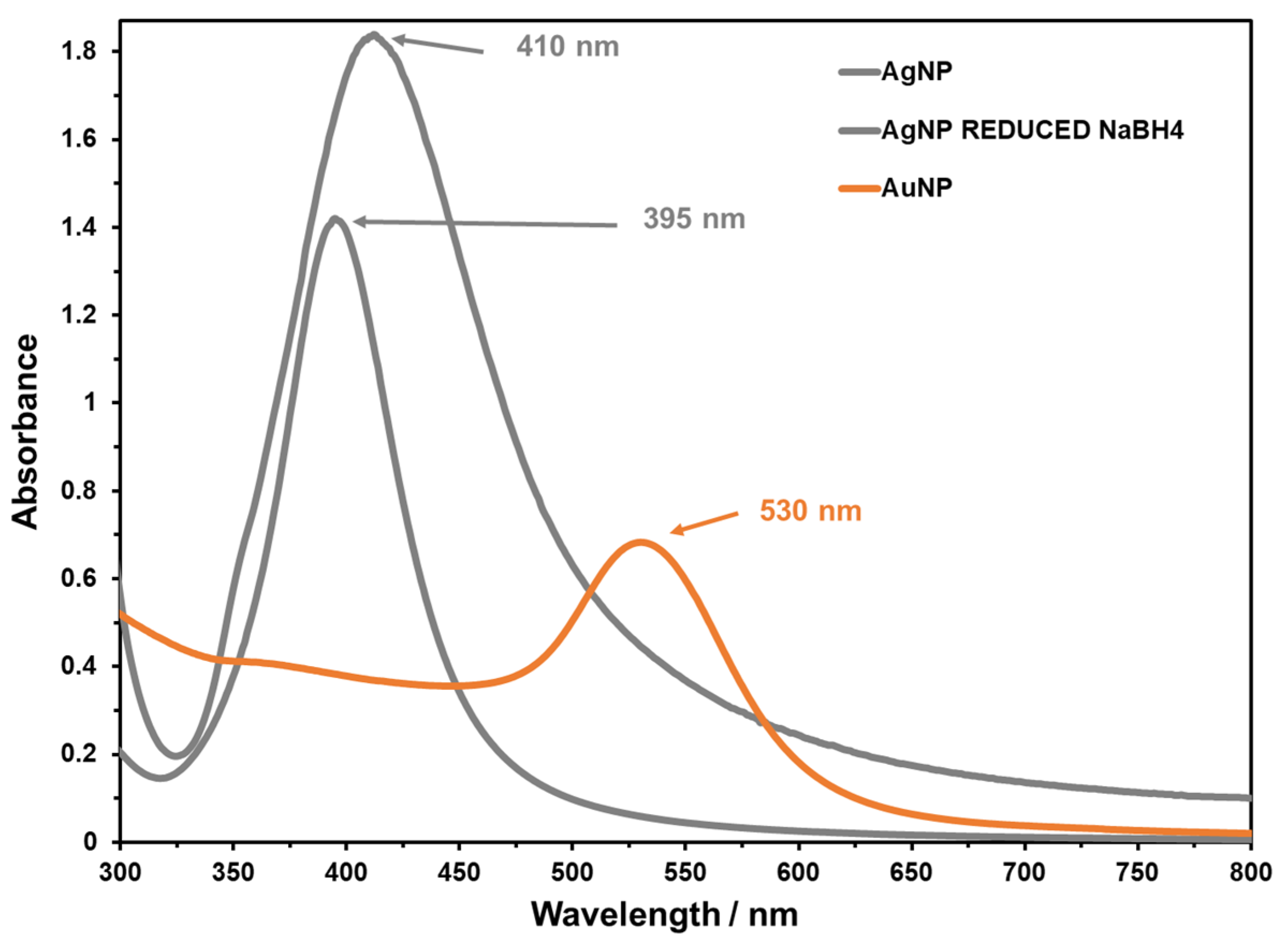

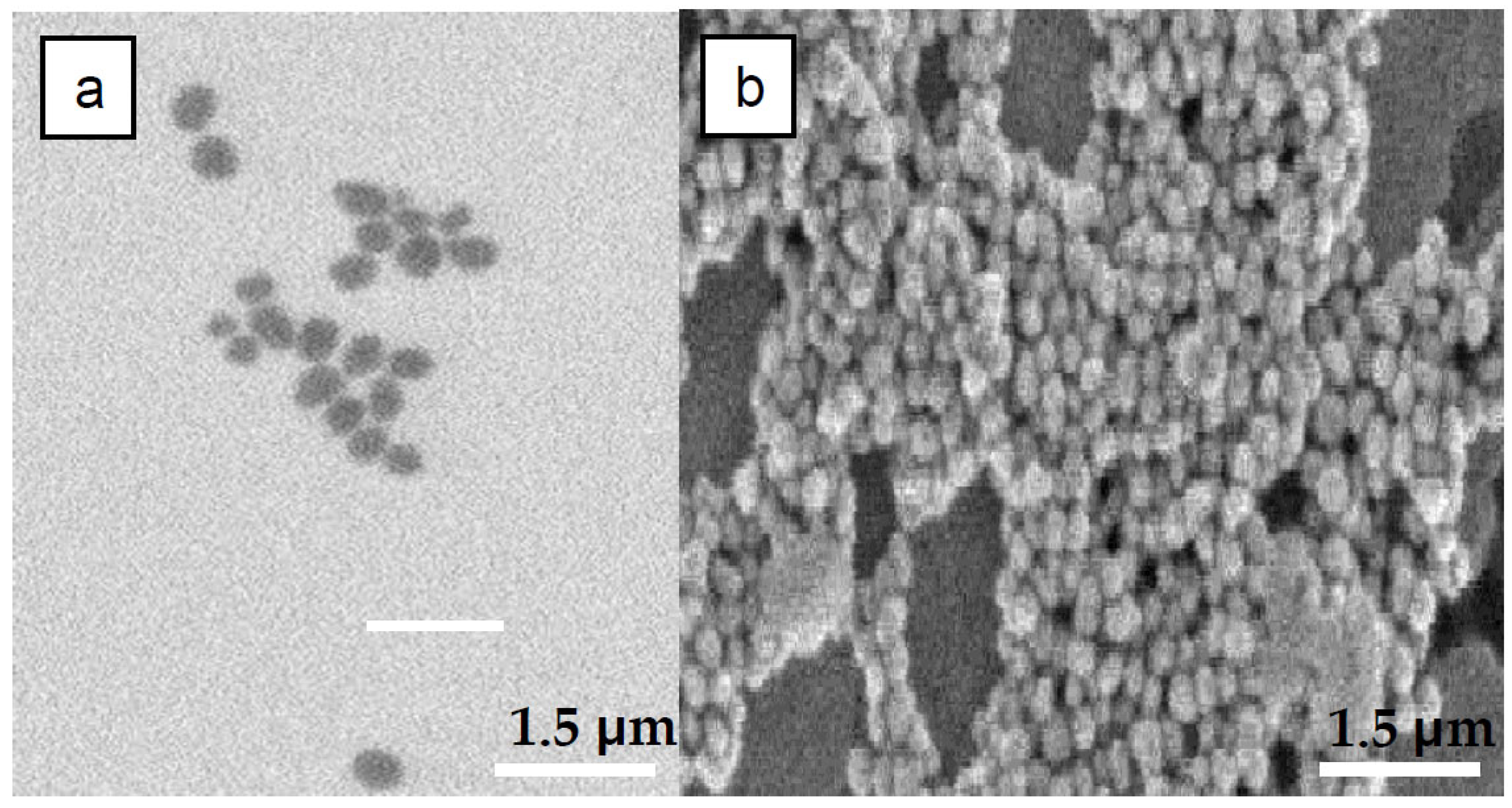

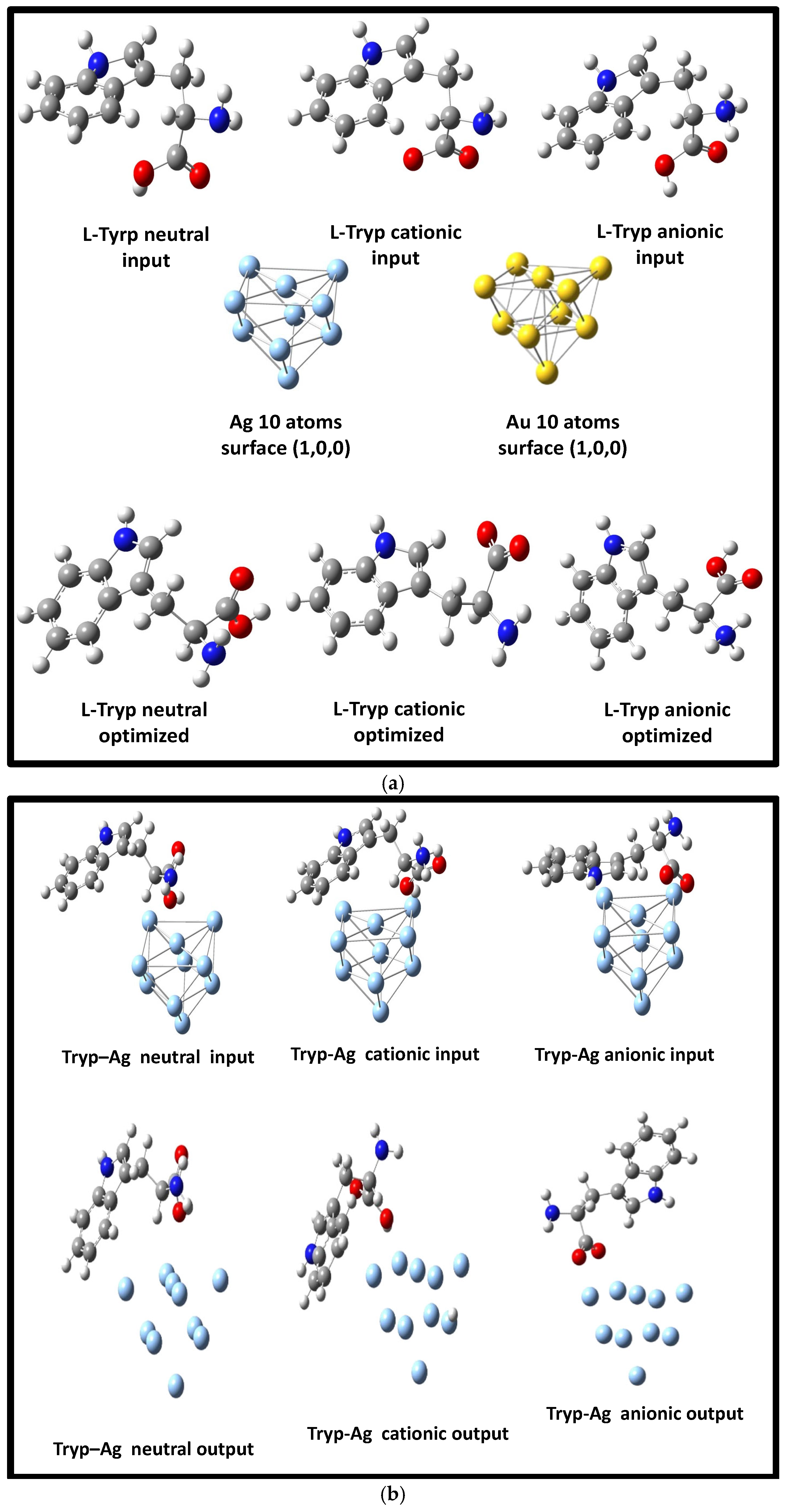

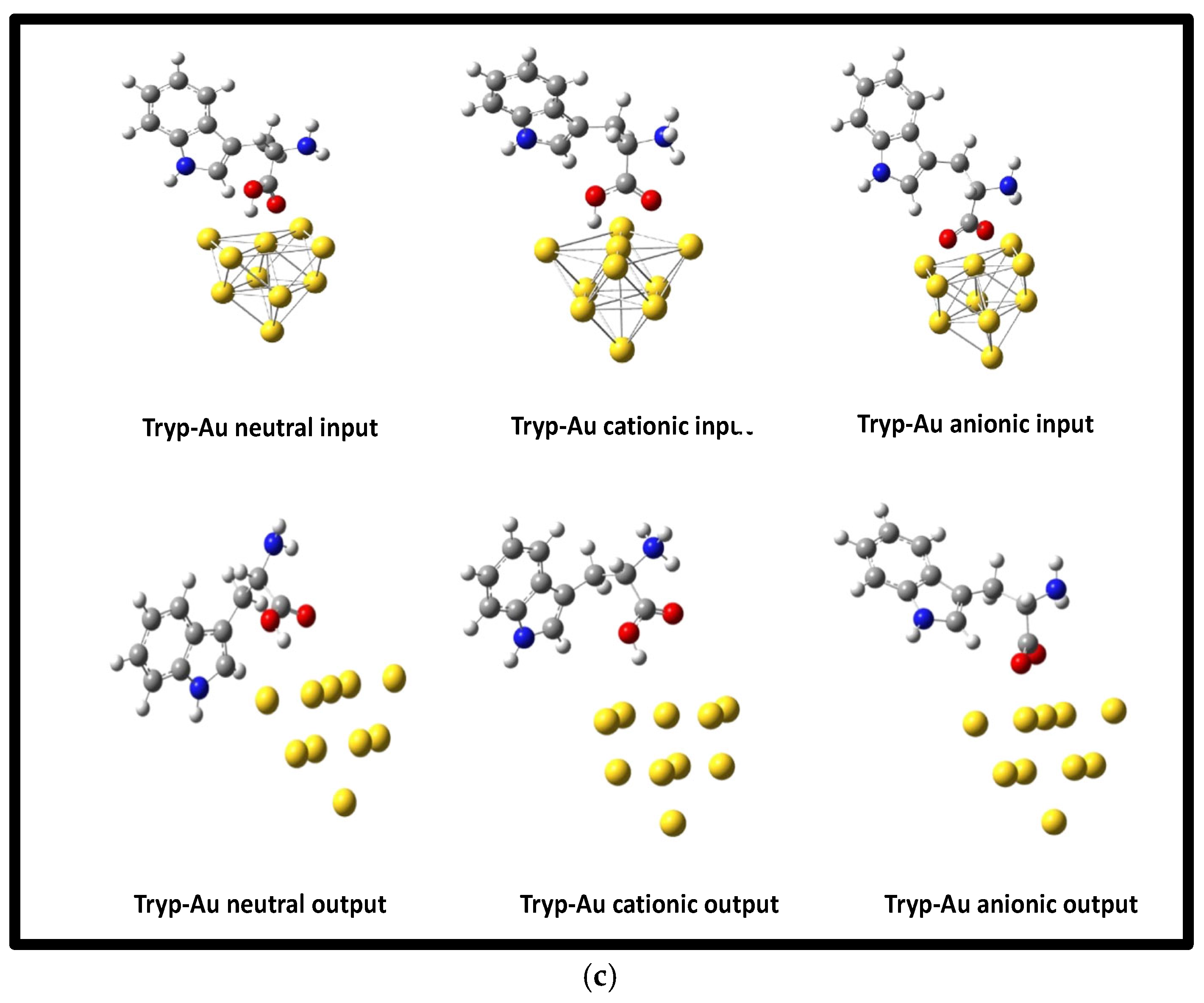

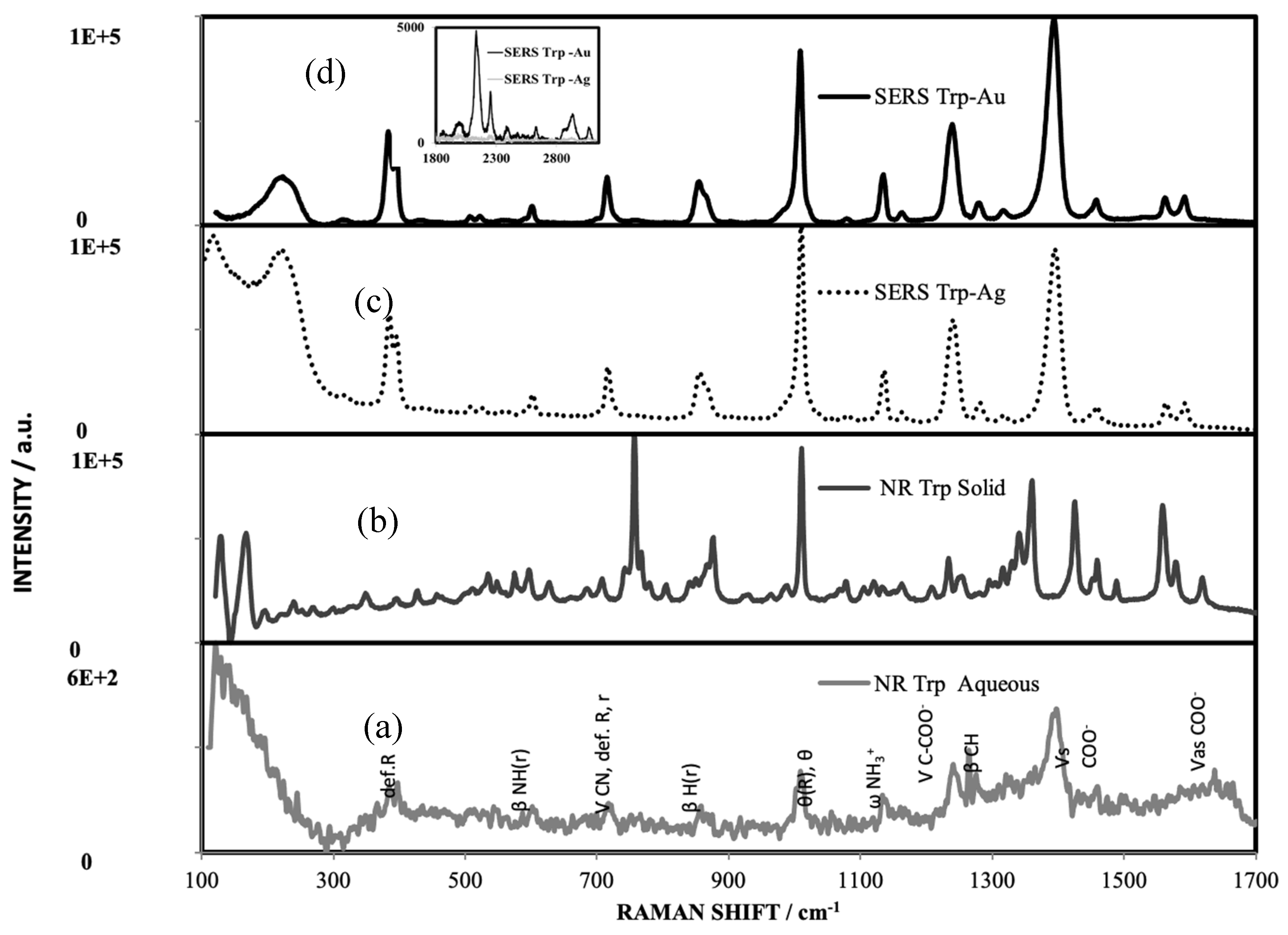

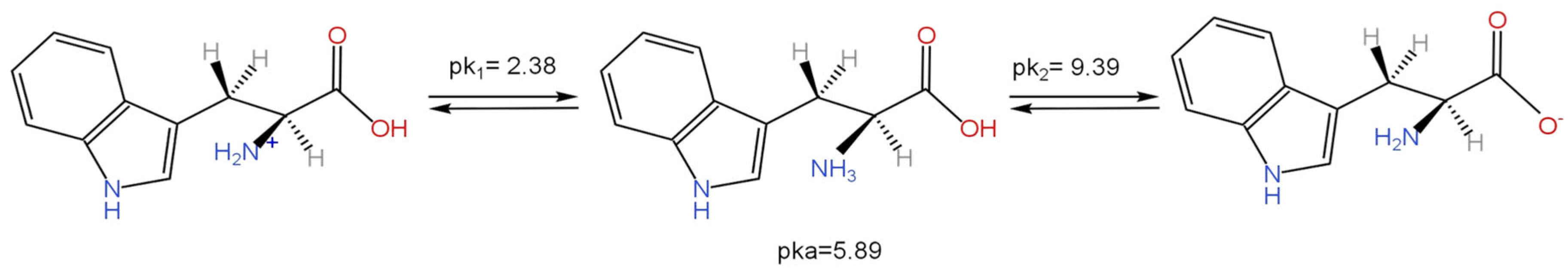

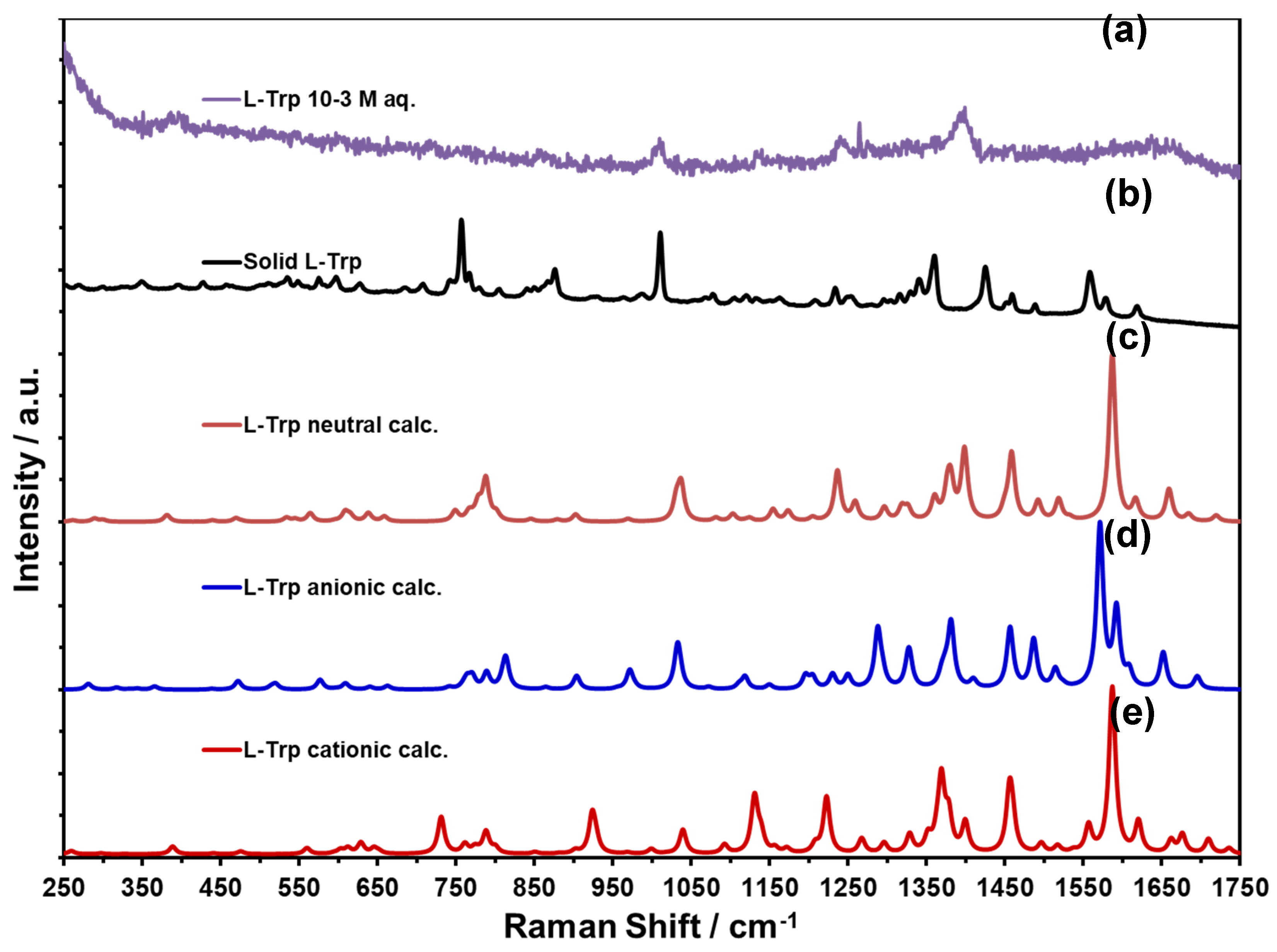

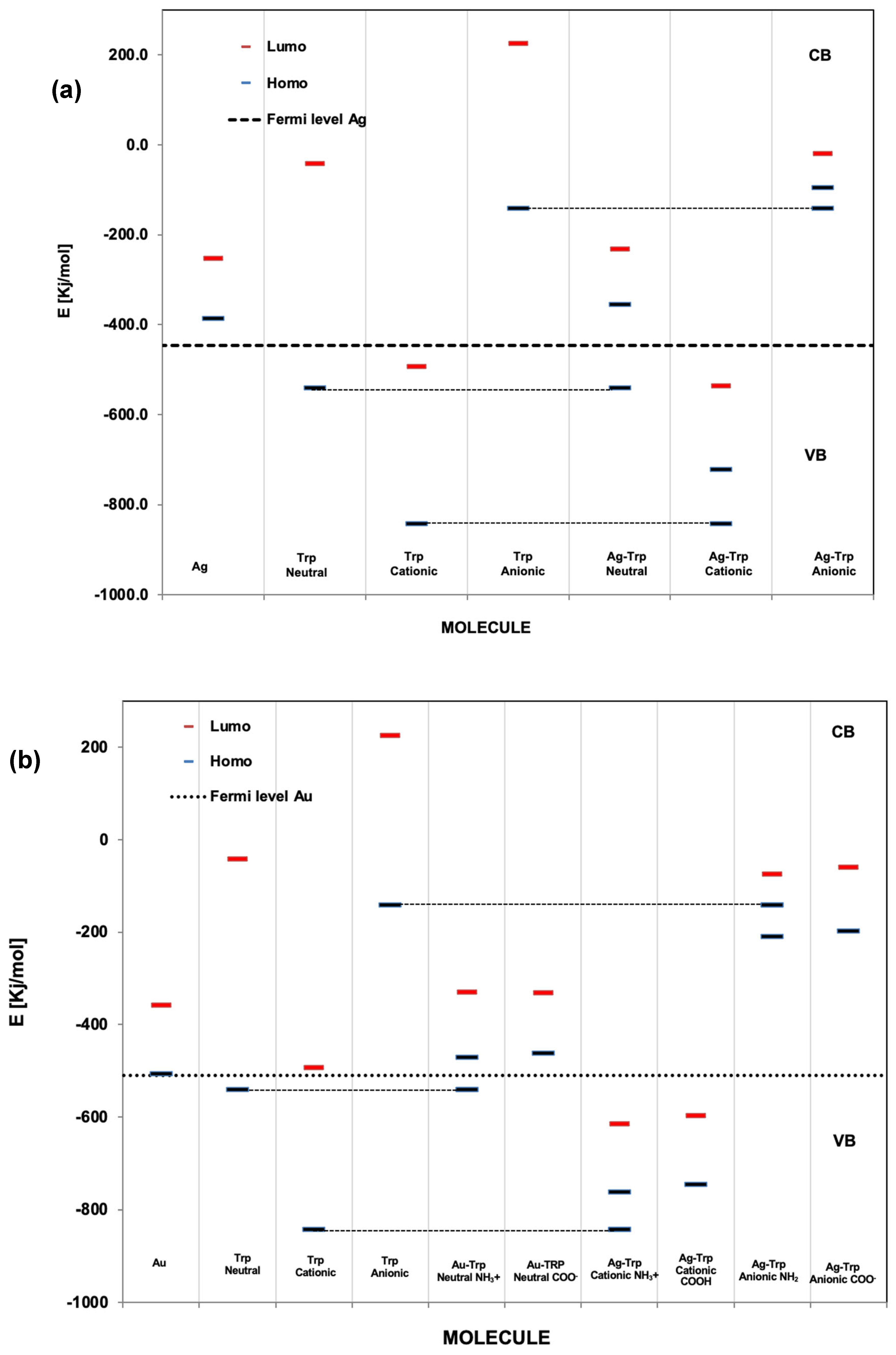

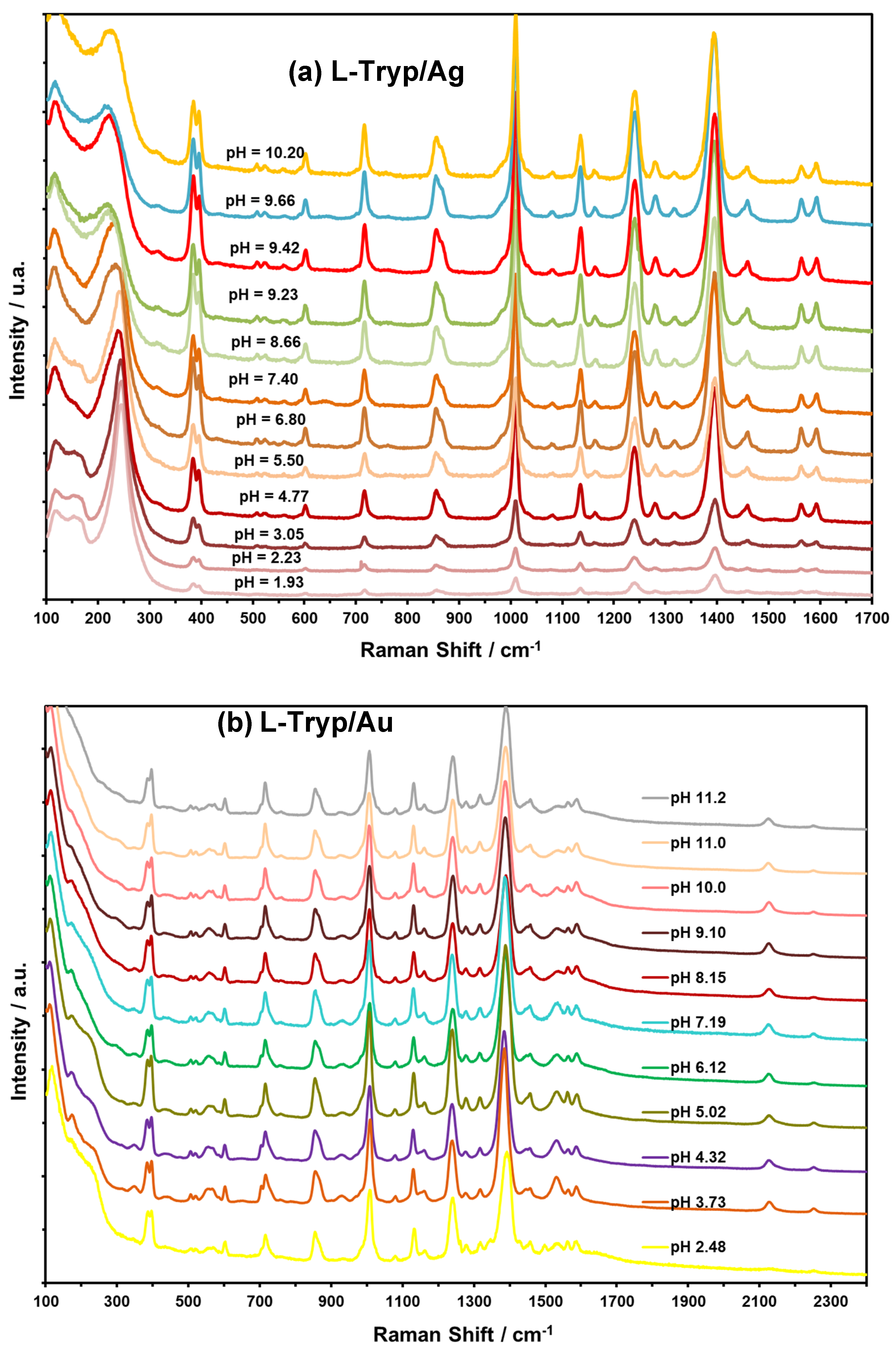

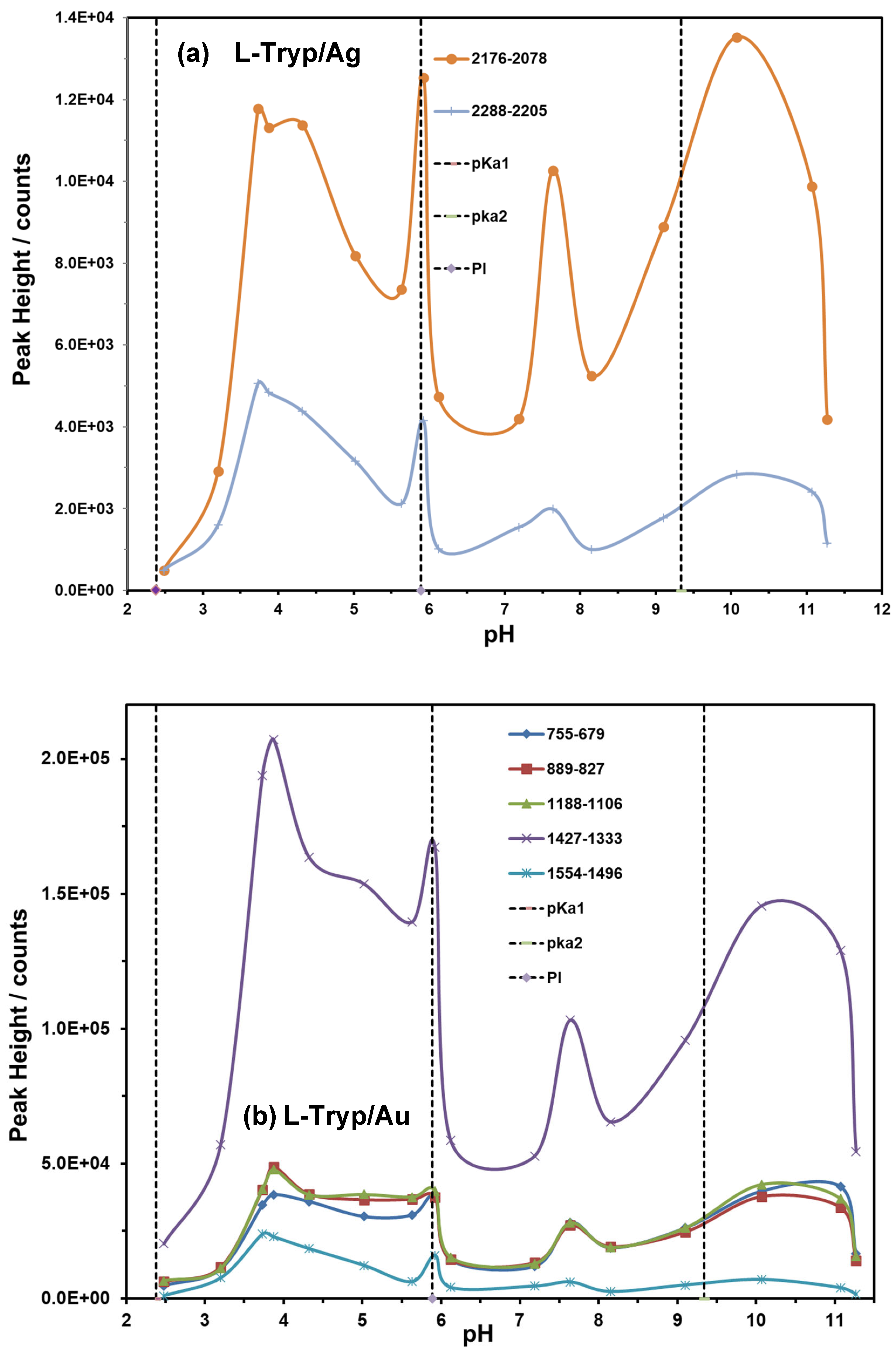

The objective of this study was to determine the most stable conformation of L-tryptophan (L-Tryp) on gold and silver nanoparticles. In addition, this work explored how these parameters were affected by analyte concentration, nanoparticle size, and pH. The purpose was to establish whether L-Tryp molecules interact with the nanoparticles through the carboxylate end, the amino group end, or both. This research has brought diverse applications in biophysics and medical diagnostics, potentially opening new avenues in these fields. Moreover, it may enrich the disciplines of chemistry and nanotechnology by offering innovative approaches for future research. These findings represent a significant advancement in understanding the interactions between L-Tryp and nanoparticles, making a meaningful contribution to biophysics and medical diagnostics. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) spectra of L-Tryp in the 200–3500 cm⁻¹ spectral range were obtained using a 785 nm laser for excitation. Gold and silver nanoparticles were synthesized using the citrate reduction method. The experimental procedure involved the use of electrolytes (such as NaCl) for colloid activation, which resulted in very high SERS signals. Modification of nanoparticle surface charge was achieved by adjusting the pH of Au and Ag colloidal suspensions between 2 and 11. The SERS spectra indicate that small-sized nanoparticles require high concentrations of L-Tryp to achieve high sensitivity, whereas larger nanoparticles perform effectively at lower concentrations. The pronounced enhancement of stretching vibrations in the COO⁻ group in the SERS spectra strongly suggests that the carboxylate group attaches to silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). Conversely, for gold nanoparticle (AuNP), a new band at approximately 2136 cm⁻¹ was observed, indicating that the amino group of L-Tryp interacts with Au in its neutral form. These analyses were complemented with theoretical modeling, employing the Density Functional Theory (DFT) running under Gaussian™ to study molecular models in which L-Tryp interacted with the AgNPs and AuNPs substrates in neutral, cationic, and anionic forms.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Ag and Au Colloids

2.3. Instrumentation

2.4. RS Experiments

2.5. Computational Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nanoparticles Characterization

3.2. Optimization of Geometries of L-Tryp on NP substrates models

3.3. RS Spectra

3.4. Theoretical Discussion

3.5. Effect of pH on Vibrational Bands of L-Tryp on Ag and Au Colloids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Code: Data: and Materials Availability

Abbreviations

| L-tryptophan - L-Tryp RS – Raman Scattering and Normal Raman Scattering - NR Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering - SERS Ag – silver Nanoparticles - NPs silver nanoparticles - AgNPs Au - gold Gold nanoparticles - AuNPs Density Functional Theory - DFT Ultraviolet-visible - UV-Vis |

References

- Aliaga, A.E.; Osorio, I.; Leyton, P.; Garrido, C.; Caniulefa, C.; Diaz, G.; Celis, F.; Diaz, G.; Clavijo, E.; Gomez, S.; Campos, M. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009, 40, 164–169.

- Kandakkathara, A.; Utkin, I.; Fedosejevs, R.; App. Spec. 65, 5, 2011, 507 – 513.

- Dechan, M.F.; Lu, D.; You, R.; Chem, C.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huiying, S.; Feng, S. Anal. Chim. Acta., 2020, 1 – 30.

- Zaheer, Z.; Ahmad-Malika, M.; Al-Nowaiser, F.M.; Khana, Z. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2010, 81, 587–592.

- Berg, J.M.; Tymoczko, J.L.; Stryer, L. Biochemistry. 5th ed., New York: W.H. Freeman; (2002). Section 3.1, Proteins Are Built from a Repertoire of 20 Amino Acids. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22379/.

- Dehghan, M.; Fouladi, J.; Mousavinezhad, S. J. Paramedical Sciences (JPS), 2010, 1, 2, 19 – 25.

- Badawy, A.; Inter. J. Tryp Research, 10, 1 – 20, 2017 . [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J.D. J. of Nutr. 142, 2236S 0 224S, 2012. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Contreiras, I. B.; Toscano, A.E.; Cabral, D.; Barreta, M.S.; Manhaes, R.; Bonfim, T. C.; Barreto, J. M. Euro. J. Pharma., 836, 2018, 129 – 135.

- Powers, R.; Cilp-Hill, R.; Ludwig, M.; Smith, K.; Waugh, K.; Minter, R.; Tuttle, K.; Lewis, H.; Rachbinki, A.; Gransrath, R.; Carmona-Iragui, M.; Wilkerson, R.; Kahn, D.; Joshi, M.; Lleo, A.; Blesa, R.; Fortea, J.; Alessaandro, A.; Costello, J.; Sullivan, K.; Espinosa, J.; Nature Commu, 10:4766, 2019, 1 – 11.

- Floc’h, N.; Otten, W.; Merlot, E. Amino Acid, 2011, 41, 5, 195 – 205.

- Chung, K.T.; Gadupudi. G.S. Environ. Mol. Mutagen., 2011, 52: 81–104.

- Oliveira, M.M.; Ugarte, D.; Zanchet, D.; Zarbin, A.J.G. J. Colloid Interf Sci., 2005, 292, 429- 435.

- Hugh, C.; Chena, Y.; J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009, 40, 150–156.

- Guiherme, B.; Sodre, L. Sant’Ana, Spectroquim. Acta P A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 190, 2017, 383–391.

- Ramanauskaite, L.; Snitka, V. Chemical Physics Letters 623, 2015, 46–50.

- Alvarez, R.; Arceo, E.; Goulet, P.; Garrido, J.; Aroca, R. J. Phys. Chem. B., 2005, 109, 3787 – 3792.

- Murphy, C.J.; Gole, A.M.; Stone, J.W.; Sisco, P.N.; Alkilany, A.M.; Goldsmith E.C.; Baxter, S.C. Acc. Chem. Res., (2008), 41 (12), 1721–1730.

- Fleger, Y.; Mastai, Y.; Rosenbluha, M.; Dressler, D.H. J. Raman Spectrosc., 2009, 40, 1572–1577.

- Ahern, M.; Garrell, R.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 846.

- Lee, H.I.; Suh, S.W.; Kim, M.S. J. Raman Spectrosc., 1988, 19, 491- 495.

- Aliaga, A.E.; Osorio, I.; Leyton, P.; Garrido, C.; Carcamo, J.; Caniulef, C.; Celis, F.; Diaz, G.; Clavijo, E.; Gomez, J.; Campos, M, J. Raman Spec., 2008, 76, 164-169.

- Kim, S.K.; Kim, M.S.; Suh, S.W. J. Raman Spectrosc. (1987), 18, 171.

- M. Kazanci, J.P. Schulte, C. Douglas, P. Fratzl, D. Pink, T. Smith-Palmer, Appl. Spec., (2008) 63 214-223.

- Lee P.C.; Meisel, D. J. Physical Chemistry, 1982, 88, 3391.

- Lisiecki, I.; Billoudet, F.; Pileni, M.P. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 1996, 4160–4166.

- Chamoun-Emanuelli, A.M.; Primera-Pedrozo, O.M.; Barreto-Caban, M.I.; Jerez-Rozo, J.; Hernandez-Rivera, S.P. Nanoscience and Nanotechnology for Chemical and Biological Defense, American Chemical Society, 2009, 217-232.

- Primera-Pedrozo, O.M.; Rodríguez, G.D.M.; Castellanos, J.; Felix-Rivera, H.; Resto, O.; Hernández-Rivera, S.P. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2012, 87, 77-85.

- Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A.V.; Bloino, J., Janesko, B.G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H.P., Ortiz, J.V., Izmaylov, A.F., Sonnenberg, J.L., Williams-Young, D., Ding, F., Lipparini, F., Egidi, F., Goings, J., Peng, B., Petrone, A., Henderson, T., Ranasinghe, D., Zakrzewski, V.G., Gao, J., Rega, N., Zheng, G., Liang, W., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Throssell, K., Montgomery Jr., J.A., Peralta, J.E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M.J., Heyd, J.J., Brothers, E.N., Kudin, K.N., Staroverov, V.N., Keith, T.A., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A.P., Burant, J.C., Iyengar, S.S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Millam, J.M., Klene, M., Adamo, C., Cammi, R., Ochterski, J.W., Martin, R.L., Morokuma, K., Farkas, O., Foresman, J.B., Fox, D.J. Gaussian™ 16.0 and GaussView™ 5.0, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT (2016) Wallingford, E.U.A.

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. J. Phys. Chem. B.; 2003, 107, 668–677.

- Suh, J.S.; Moskovits, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108, 4711.

- Cao, X.; Fisher, G. J. Phys. Chem. B, 1999, 103, 9995- 10003.

- Kandakkathara, A.; Utkin, I.; Fedosejevs, R.; App. Spec., 2011, 65, 506 – 513.

- Madzharova, F.; Heiner, Z.; Kneipp, J.; J. Phys. Chem. C., 2016, 1 – 31.

- Ruthven, D.M. Principles of Adsorption and Adsorption Processes, John Wiley: New York, 1984.

- Takigawa, T.; Ashida, T.; Sasada, Y.; Kakudo, M.; Chem. Soc. Japan, 1966, 39, 2369 – 2378.

- Chuang, C.H.; Chen, Y.T. J. Raman Spectrosc. (2009) 40, 150-156.

- Markovits, A.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Ricart, J.M.; Illas. F. J. Phys. Chem. B, 1999, 103, 509.

- Suh J.S.; Kim. J. J. Raman Spectrosc, 1998, 29, 143.

- Bae, S.J.; Lee, C.; Choi, I.S.; Hwang, C.S.; Gong, M.S.; Kim, K.; Joo, S.W. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2002, 106, 7076.

- T. Nibbering, T. Elsaesser, Chem. Rev., 2004, 104, 10.

- Herne, T.M.; Ahern, A. M.; Garrell, R.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 846.

- Allen, C.S.; Van Duyne, R.P. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 7497.

- Roy, D.; Furtak, T.E. J. Chem. Phys.,1984, 81, 4168.

- Adamson, A.W. Physical Chemistry of surfaces, John Wiley and Sons: New York, 1990.

- Bhattacharya, S.; Vyas, N.; Ojha, A.K.; Dasgupta, S.; Roya, A. J. Raman Spectrosc.,2012, 43, 718–723.

|

NR Trp Neutral DFT Calculations |

NR L-Tryp Solid | NR L-Tryp Aqueous Solution |

SERS DFT Calculations CCSDE |

SERS Experimental CCSDE |

Assignment (cm-1) DFT Calculations LANL2DZ CCSDE, and Compared from Ref. [32,33] | |||

| Ag | Au | Ag | Au | Ag | Au | |||

| 260 | 243 | 245 | 232 | νAg-O | ||||

| 359 | 352 | 380 | 323 | 329 | 359 | ω -NH2 | ||

| 408 | 395 | 385 | 385 | 386 | def. R. | |||

| 430 | 412 | 396 | 398 | def. R, r | ||||

| 476 | 472 | 467 | β -CC- R, r, γ -CH2 | |||||

| 526 | 514 | 579 | 523 | 520 | β -N-H (r) ν R, r | |||

| 537 | 533 | 590 | 529 | 536 | δ(r), β i.p. | |||

| 595 | 598 | 551 | 599 | 574 | 574 | β (R)oop; γ -CH2 (high intensities in SERS) | ||

| 630 | 607 | 620 | 640 | 604 | 607 |

γ -CH2; α -NH2; β C-O |

||

| 689 | 679 | ν R, r | ||||||

| 710 | 722 | 718 | 711 | Def. R, r,ν -CN | ||||

| 748 | 748 | 749 | 724 | 744 | 740 | 721 |

ω -H(R); γ -CH2; β -COO1- |

|

| 771 | 757 | 759 | 771 | 758 | θ (R), θ (r) | |||

| 778 | 778 | 768 | 793 | 775 | Def. R, r, α -COO- | |||

| 787 | 788 | 789 | 790 | β (R) -CC-; β (r) | ||||

| 808 | γ-CH2, β -COO1- | |||||||

| 845 | 845 | 846 | 869 | 843 | 824 | β -CH(r), | ||

| 858 | 859 | 858 | 864 | δ-H(R),β-CH(-NH) (r) | ||||

| 878 | 878 | 877 | 891 | 889 | 868 | β -H(R), α -H(r) | ||

| 902 | 902 | 933 | 929 | 893 | 942 | ν-CC- (r);ν-CNC-, (r) | ||

| 959 | 974 | 975 | 980 | δ-CH(r); γ-CH2; β-CH; γ-NH2 | ||||

| 969 | 969 | 993 | 976 | 984 | δ -CH2; ν -CN | |||

| 1001 | 1010 | 1011 | 1010 | 1015 | 1011 | 1009 | θ(R), θ (r); β H(R) | |

| 1031 | 1031 | 1028 | 1024 | γ -NH3+, β H(C) | ||||

| 1037 | 1066 | 1060 | 1036 |

α(R)s in plane, β-H (R) |

||||

| 1081 | 1079 | 1065 | 1085 | 1090 | 1083 | αH(r) | ||

| 1103 | 1103 | 1112 | 1125 | 1100 | ω -NH3 +, β -H(C) | |||

| 1124 | 1109 | 1137 | 1132 | ω NH3 +, β H(C) | ||||

| 1154 | 1154 | 1143 | 1140 | 1148 | 1153 |

α -H(R), ω -NH3 +, β -CH |

||

| 1174 | 1174 | 1167 | 1170 | 1169 | 1174 | 1170 | 1168 | γ -CH2, α -H(R); |

| 1204 | 1213 | 1206 | υ -(r), υ -C-COO - | |||||

| 1236 | 1236 | 1235 | 1243 | 1237 | 1241 | 1242 | 1243 | α-H(R), γ-H(r) |

| 1259 | 1264 | 1264 | 1267 | 1250 | 1251 |

γ -H(R), γ -H(r), β -CH |

||

| 1296 | 1296 | 1300 | 1276 | 1277 | 1284 | 1289 | β -H(-CH2) | |

| 1318 | 1318 | 1318 | 1319 | 1291 | 1296 | υ (R), υ (r) | ||

| 1326 | 1326 | 1337 | 1324 | 1316 | 1331 | 1334 | ν -CN, β -CH; ω -CH2 | |

| 1342 | 1345 | 1343 | β -CH, β -H (-CH2) | |||||

| 1360 | 1360 | 1361 | 1361 | 1365 | ω -CH2, β -CH | |||

| 1376 | 1376 | 1374 | 1375 | 1374 | υ (r), υ (R) | |||

| 1380 | 1380 | 1391 | 1398 |

γ -CH(R); ν (r); β -CH (-NH); δ -CH2 |

||||

| 1398 | 1398 | 1427 | 1399 | 1404 | 1405 | 1396 | 1387 | υs -COO1- |

| 1450 | 1450 | 1457 | 1416 | 1416 | 1463 | 1457 | α -CH2, δ -NH2 | |

| 1459 | 1459 | 1461 | 1461 | 1453 | 1441 | 1464 | υ (r), υ (R),νs -NH3 + | |

| 1492 | 1492 | 1490 | 1489 | 1479 | β -CH(R) | |||

| 1517 | 1517 | 1504 | 1513 | 1506 |

δ -CH2; SERS: ν(R) -CC-, β -CH, β -CH (r) (-NH) |

|||

| 1560 | 1557 | 1541 | 1560 | 1541 | ν(r),ν(R) | |||

| 1587 | 1587 | 1581 | 1603 | 1598 | 1595 | 1578 | α -NH3+ | |

| 1616 | 1616 | 1628 | 1638 | 1618 | 1618 | 1594 | Φ (ringst) -CC-st, β -CC-bend, β -CHalk; β -CH (r) (-NH), δ -CH2 | |

| 1653 | νas -COO -, α -CCO | |||||||

| 1659 | 1659 | 1666 | 1661 | 1667 | ν(R)-CC-, β-CC-, βCHalk; β-CH (r) (-NH), α-NH3+ | |||

| 2136 | νas -CN | |||||||

| 2254 | νs -CN | |||||||

| 2952 | 2950 | 2942 | νas -H(R) | |||||

| 3065 | 3059 | 3083 | νs -NH3+ | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).