Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

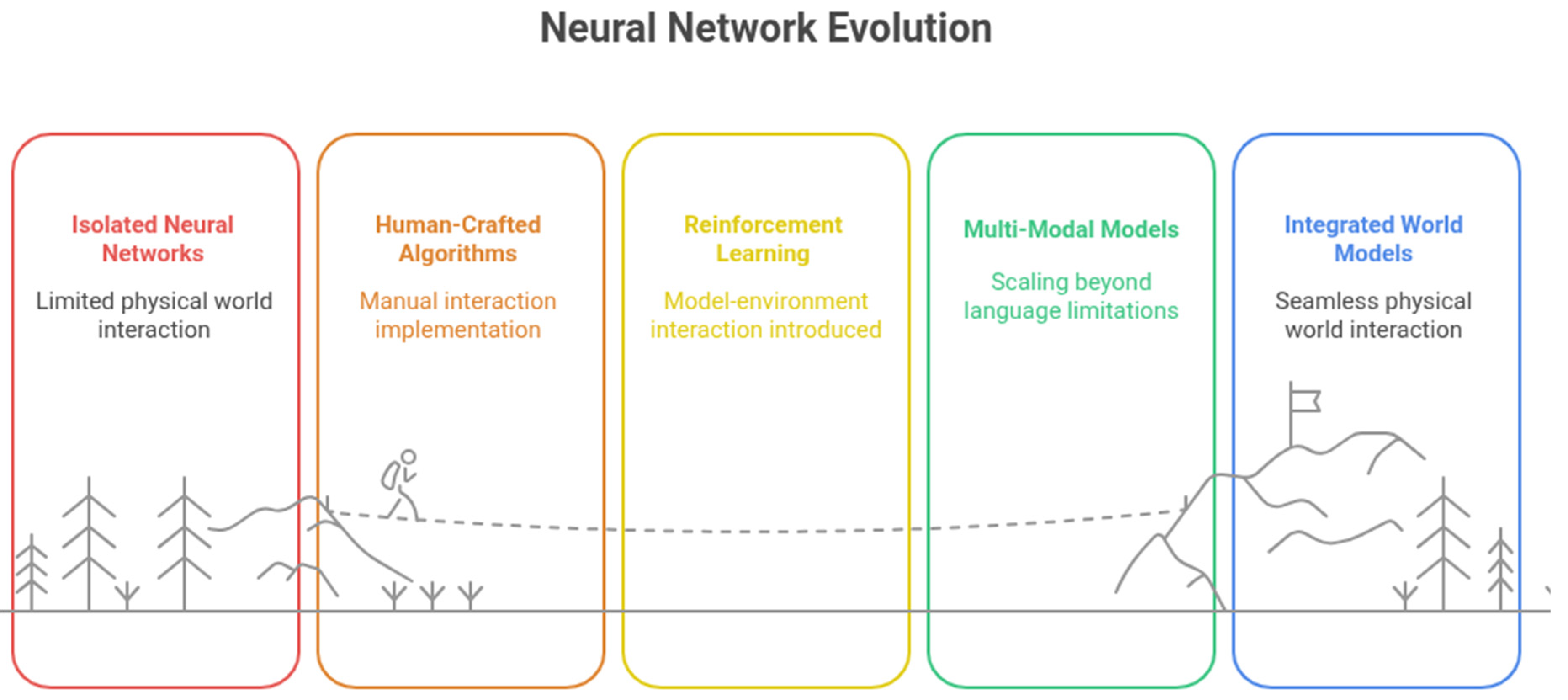

1. Introduction

- ●

- Hallucination: Models can generate unrealistic or factually inconsistent outputs that diverge from real-world phenomena.

- ●

- Misalignment: Models may not perform as intended, necessitating further training or recalibration to align with desired behaviors.

- ●

- Security Risks: Models might fail to adequately cope with complex or unforeseen environmental conditions. A common example is the need for human intervention (takeover) in autonomous vehicles when the system encounters challenging scenarios.

- ●

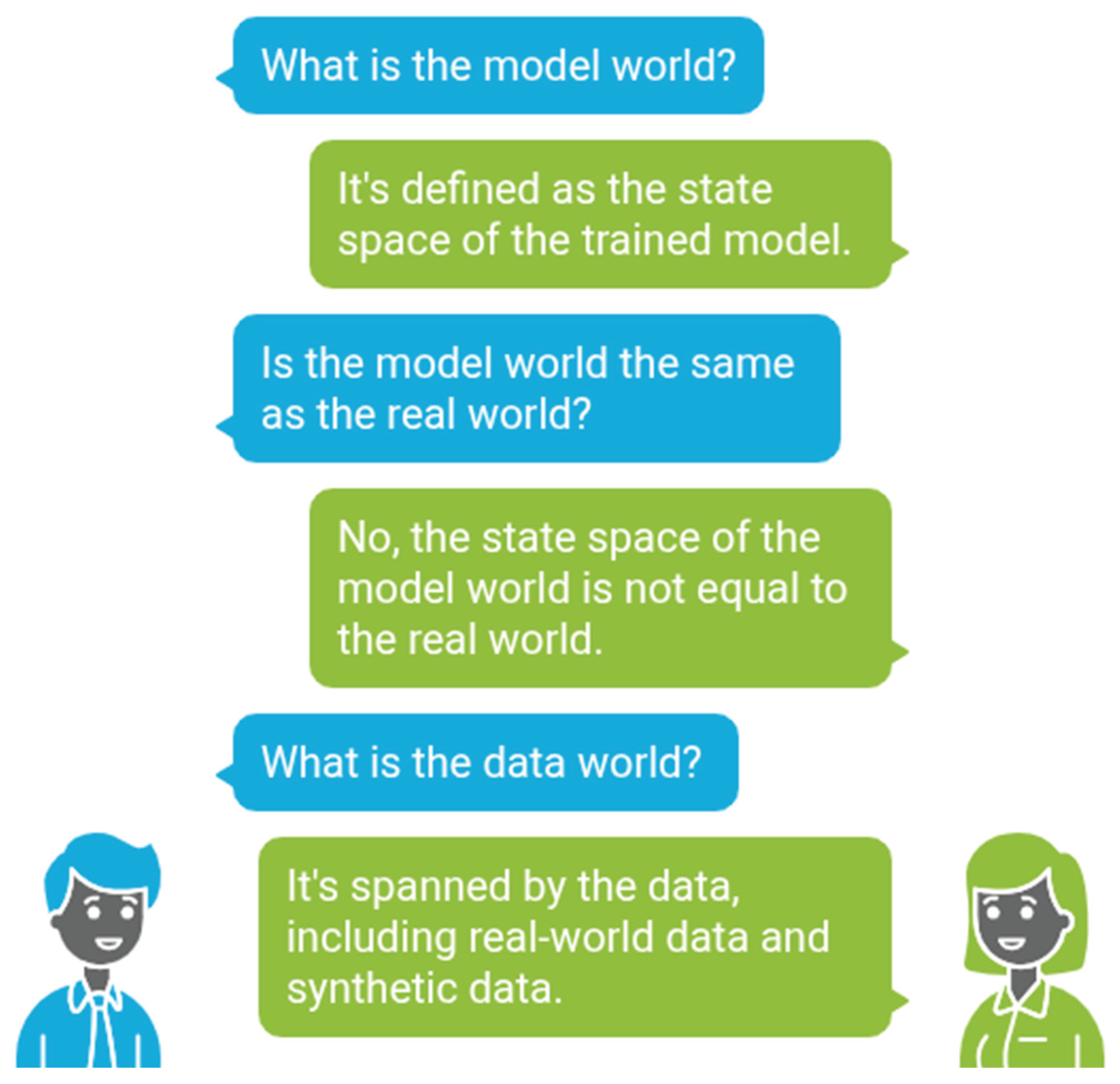

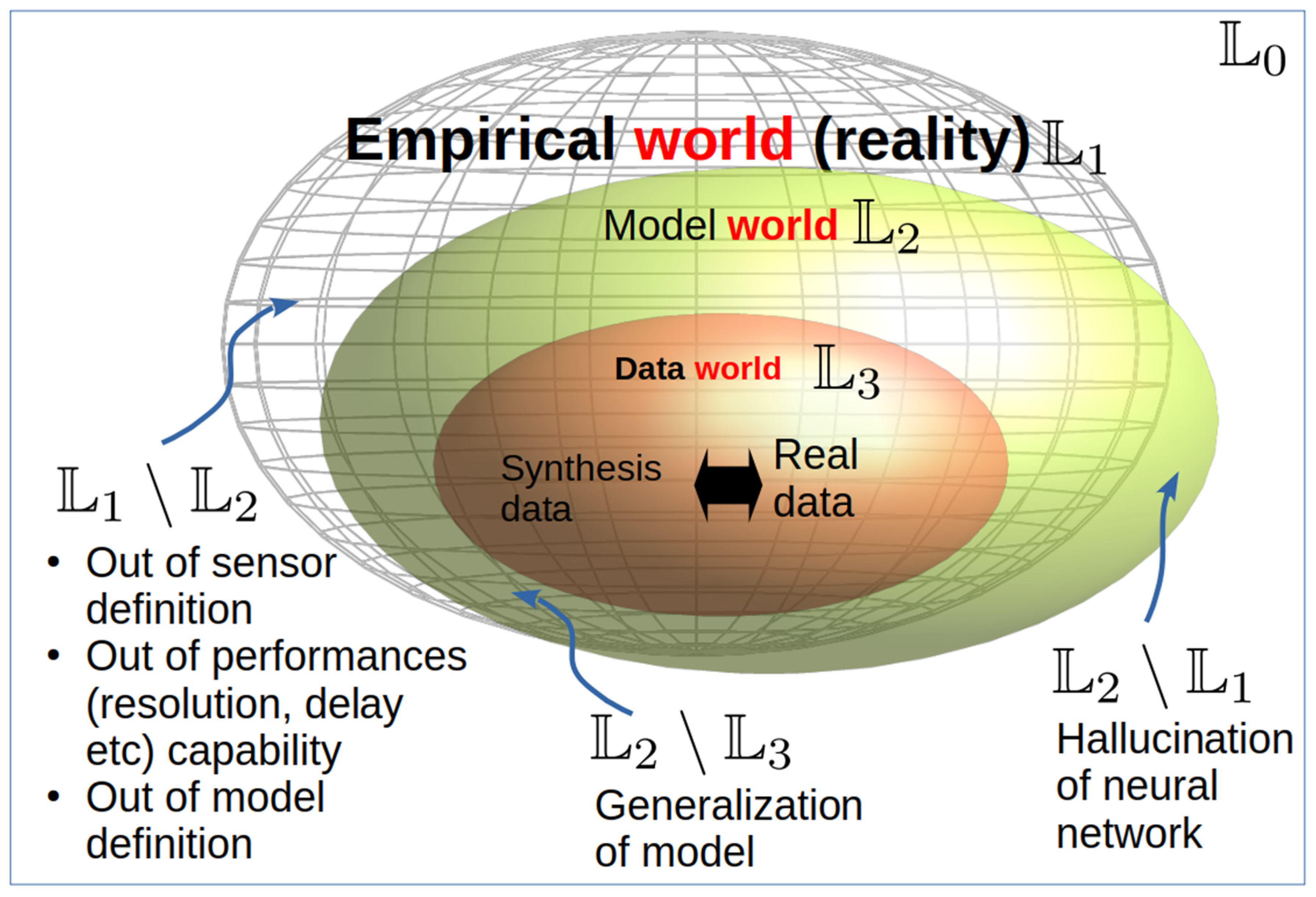

- The "model world" is defined as the state space of the trained neural network model. This model world's state space is distinct from that of the real world.

- ●

- The "data world" is spanned by the data used for training and validation, encompassing both real-world and synthetic data.

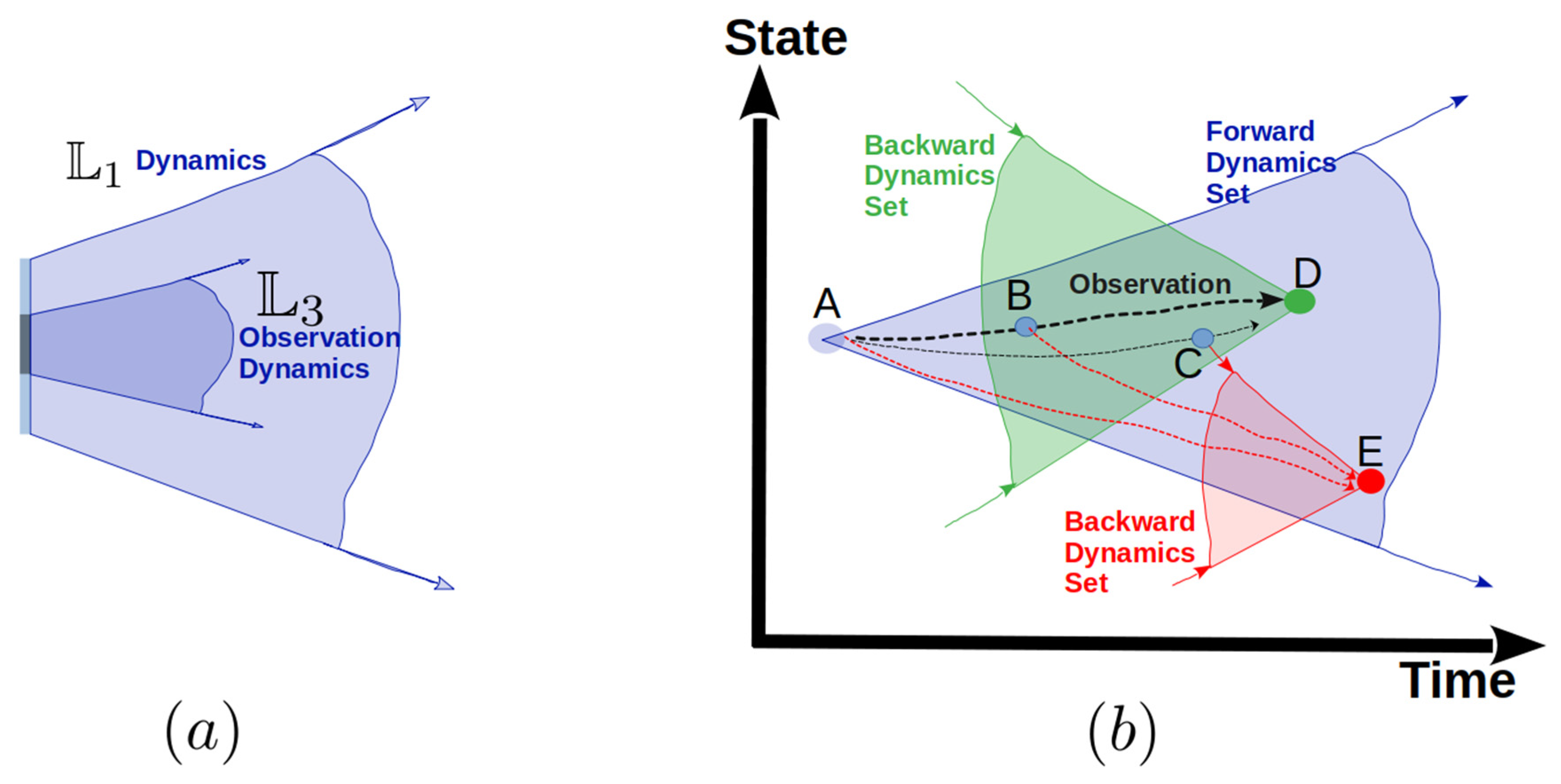

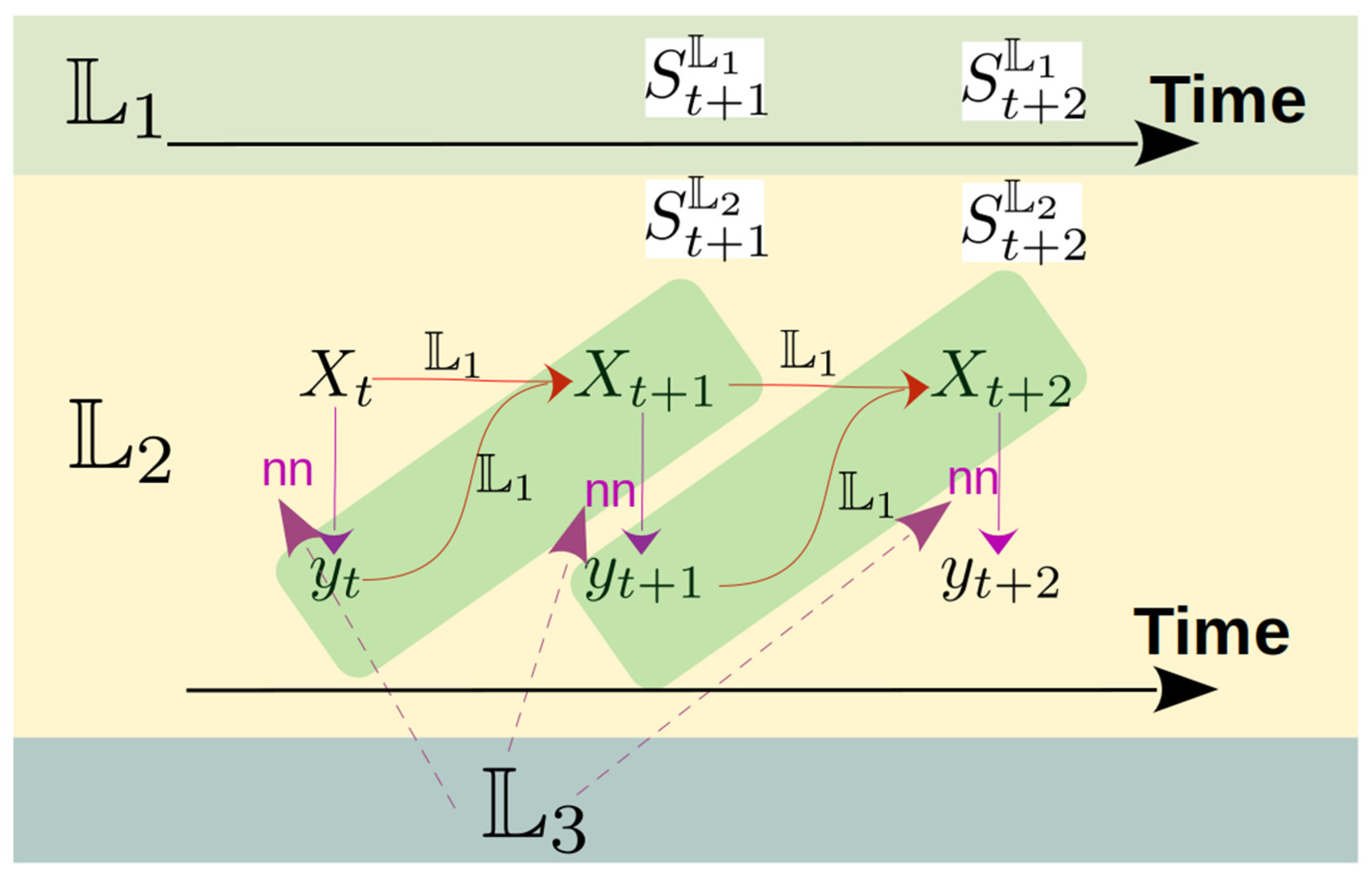

2. Three-World Hierarchy

- ●

- Empirical World ()

- ●

- Model World ()

- ∎

-

States Not Covered by the Model (∖): This set difference represents aspects of the Empirical World that fall outside the model's perceptual or operational capabilities. Several factors contribute to this:

- ◆

- Undefined Sensor Modalities: The model's sensors may not be designed to capture certain states. For example, an autonomous vehicle lacking an infrared detector cannot directly sense pavement temperature, even if it could be indirectly estimated.

- ◆

- Performance Limitations: The model's capabilities may be insufficient to resolve certain details within its defined state space. For instance, an autonomous vehicle's detectors might have limited resolution, preventing the detection of nanoscale pavement details.

- ◆

- Out-of-Definition States: The state space is simply beyond the model's fundamental definition. A standard large language model, for example, cannot inherently perceive audio.

- ∎

- Model-Generated States Not Existing in Reality (\): This set difference signifies instances where the model generates outputs that have no corresponding existence in the Empirical World. These outputs are often referred to as hallucinations. Examples include a large language model generating a non-existent reference or a text-to-image model producing physically impossible or "weird" images. Numerous underlying reasons contribute to the generation of these non-existent states.

- ●

- Data World ()

3. Frechet World Distance for Multi-Modal Configurations

3.1. Conventional Frechet Distance

3.2. Frechet World Distance for Unimodal C

- -

-

Beginning and ending of the sequence are matched together:

- ∎

- ∎

- -

-

The sequence is monotonically increasing in both i and j:

- ∎

- ∎

3.3. Frechet World Distance for Multi Modal

4. Related Work

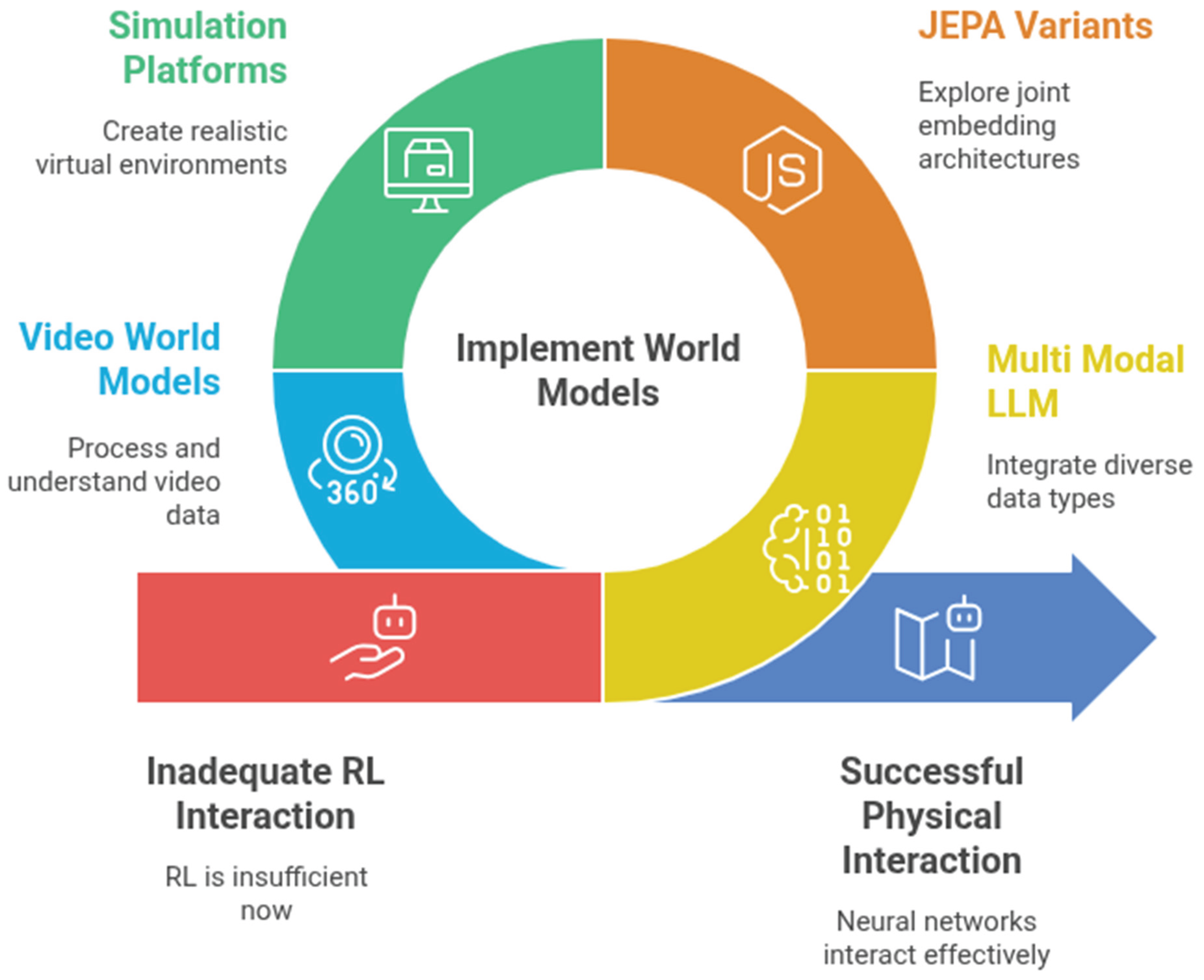

4.1. World Model

4.2. JEPA and Its Variants

4.3. Frechet Distance

4.4. Potential Harms of Neural Networks Model in Physical World

5. Discussion and Conclusion

- 1)

- Develop three-worlds hierarchy JEPA models to encapsulate complex dynamics. In the JEPA model, the cost modules can be implemented via the Frechet world distance.

- 2)

- Develop models that detect the hallucination of the neural network models. The hallucination is defined over the difference operation between model world and the real world. Given that the FWD can measure the difference between different levels of world, the FWD can serve as objective that train the models with minimal hallucination.

Disclaimer

References

- Ainslie, J., Lee-Thorp, J., de Jong, M., Zemlyanskiy, Y., Lebrón, F., & Sanghai, S. (2023). GQA: Training Generalized Multi-Query Transformer Models from Multi-Head Checkpoints. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2305.13245. [CrossRef]

- Aithal, S. K., Maini, P., Lipton, Z. C., & Kolter, J. Z. (2024a). Understanding Hallucinations in Diffusion Models through Mode Interpolation. In A. Globerson, L. Mackey, D. Belgrave, A. Fan, U. Paquet, J. Tomczak, & C. Zhang (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 37, pp. 134614–134644). Curran Associates, Inc. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/f29369d192b13184b65c6d2515474d78-Paper-Conference.pdf.

- Ashuach, T., Gabitto, M. I., Koodli, R. V., Saldi, G.-A., Jordan, M. I., & Yosef, N. (2023). MultiVI: deep generative model for the integration of multimodal data. Nature Methods, 20(8), 1222-+. [CrossRef]

- Assran, M., Bardes, A., Fan, D., Garrido, Q., Howes, R., Mojtaba, Komeili, Muckley, M., Rizvi, A., Roberts, C., Sinha, K., Zholus, A., Arnaud, S., Gejji, A., Martin, A., Hogan, F. R., Dugas, D., Bojanowski, P., Khalidov, V., … Ballas, N. (2025). V-JEPA 2: Self-Supervised Video Models Enable Understanding, Prediction and Planning. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2506.09985. [CrossRef]

- Assran, M., Duval, Q., Misra, I., Bojanowski, P., Vincent, P., Rabbat, M., LeCun, Y., & Ballas, N. (2023a). Self-Supervised Learning from Images with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2301.08243. [CrossRef]

- Assran, M., Duval, Q., Misra, I., Bojanowski, P., Vincent, P., Rabbat, M., LeCun, Y., & Ballas, N. (2023b, April). Self-Supervised Learning from Images with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z., Wang, P., Xiao, T., He, T., Han, Z., Zhang, Z., & Shou, M. Z. (2024). Hallucination of Multimodal Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2404.18930. [CrossRef]

- Bardes, A., Garrido, Q., Ponce, J., Chen, X., Rabbat, M., LeCun, Y., Assran, M., & Ballas, N. (2024, February). Revisiting Feature Prediction for Learning Visual Representations from Video. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bardes, A., Ponce, J., & LeCun, Y. (2023a). MC-JEPA: A Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Self-Supervised Learning of Motion and Content Features. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2307.12698. [CrossRef]

- Bardes, A., Ponce, J., & LeCun, Y. (2023b, July). MC-JEPA: A Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Self-Supervised Learning of Motion and Content Features. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, J., Agrawal, R., Tilak, A., Neeraj, C., & Mitra, S. (2025, February). HEP-JEPA: A foundation model for collider physics using joint embedding predictive architecture. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Batool, A., Zowghi, D., & Bano, M. (2023). Responsible AI Governance: A Systematic Literature Review. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2401.10896. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, L., Tong, M., Kaufmann, M., Balesni, M., Cooper Stickland, A., Korbak, T., & Evans, O. (2023). The Reversal Curse: LLMs trained on “A is B” fail to learn “B is A.” arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2309.12288. [CrossRef]

- Bilaloglu, C., Löw, T., & Calinon, S. (2023, November). Whole-Body Ergodic Exploration with a Manipulator Using Diffusion. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, K., Künnemann, M., & Nusser, A. (2019). Walking the Dog Fast in Practice: Algorithm Engineering of the Fréchet Distance. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1901.01504. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Hu, J., Wei, X., & Wu, E. (2025, February). Denoising with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Chrysos, G., Li, Y., Angelopoulos, A. N., Bates, S., Plank, B., & Khan, M. E. (n.d.). Quantify Uncertainty and Hallucination in Foundation Models: The Next Frontier in Reliable AI. ICLR 2025 Workshop Proposals.

- Ciesielski, M., & Lewicki, G. (2021). Admissibility of Frechet spaces. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2112.00349. [CrossRef]

- Conmy, A., Mavor-Parker, A. N., Lynch, A., Heimersheim, S., & Garriga-Alonso, A. (2023). Towards Automated Circuit Discovery for Mechanistic Interpretability. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2304.14997. [CrossRef]

- Conradi, J., Driemel, A., & Kolbe, B. (2024). Revisiting the Fréchet distance between piecewise smooth curves. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2401.03339. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, C. T. J. (2011). Some recent work in Frechet geometry. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1109.4241. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., Li, R., Wu, Y., Nguyen, T. T., Chong, J. S. X., Ji, F., Tong, N. R. J., Chen, C. L. H., & Zhou, J. H. (2024, September). Brain-JEPA: Brain Dynamics Foundation Model with Gradient Positioning and Spatiotemporal Masking. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Driemel, A., & Har-Peled, S. (2013). Jaywalking Your Dog: Computing the Fréchet Distance with Shortcuts. SIAM Journal on Computing, 42(5), 1830–1866. [CrossRef]

- Du, L., Wang, Y., Xing, X., Ya, Y., Li, X., Jiang, X., & Fang, X. (2023). Quantifying and attributing the hallucination of large language models via association analysis. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2309.05217.

- Dunefsky, J., Chlenski, P., & Nanda, N. (2024). Transcoders Find Interpretable LLM Feature Circuits. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2406.11944. [CrossRef]

- Eftekharinasab, K. (2022). Multiplicity Theorems for Frechet Manifolds. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2210.09270. [CrossRef]

- Farahbakhsh Touli, E. (2020). Frechet-Like Distances between Two Merge Trees. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2004.10747. [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z., Fan, M., & Huang, J. (2023). A-JEPA: Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture Can Listen. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2311.15830. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Guo, S., Tan, X., Xu, K., Wang, M., & Ma, L. (2022). Rethinking efficient lane detection via curve modeling. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition.

- Fu, Y., Peng, R., & Lee, H. (2023). Go Beyond Imagination: Maximizing Episodic Reachability with World Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2308.13661. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Anantha, R., Vashisht, P., Cheng, J., & Littwin, E. (2024, October). UI-JEPA: Towards Active Perception of User Intent through Onscreen User Activity. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gao, N., Li, J., Huang, H., Zeng, Z., Shang, K., Zhang, S., & He, R. (2024). Diffmac: Diffusion manifold hallucination correction for high generalization blind face restoration. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2403.10098.

- Ghaemi, H., Muller, E., & Bakhtiari, S. (2025, May). seq-JEPA: Autoregressive Predictive Learning of Invariant-Equivariant World Models. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Ghamisi, P., Yu, W., Marinoni, A., Gevaert, C. M., Persello, C., Selvakumaran, S., Girotto, M., Horton, B. P., Rufin, P., Hostert, P., Pacifici, F., & Atkinson, P. M. (2024). Responsible AI for Earth Observation. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2405.20868. [CrossRef]

- Girgis, A. M., Valcarce, A., & Bennis, M. (2025, July). Time-Series JEPA for Predictive Remote Control under Capacity-Limited Networks. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Goellner, S., Tropmann-Frick, M., & Brumen, B. (2024). Responsible Artificial Intelligence: A Structured Literature Review. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2403.06910. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Liao, H., Li, Z., Hu, J., Yuan, R., Li, Y., Zhang, G., & Xu, C. (2024). World Models for Autonomous Driving: An Initial Survey. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.02622.

- Guetschel, P., Moreau, T., & Tangermann, M. (n.d.). S-JEPA: Towards seamless cross-dataset transfer through dynamic spatial attention. [CrossRef]

- Gui, A., Gamper, H., Braun, S., & Emmanouilidou, D. (2023). Adapting Frechet Audio Distance for Generative Music Evaluation. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2311.01616. [CrossRef]

- Gurnee, W., Nanda, N., Pauly, M., Harvey, K., Troitskii, D., & Bertsimas, D. (2023). Finding Neurons in a Haystack: Case Studies with Sparse Probing. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2305.01610. [CrossRef]

- Ha, D., & Schmidhuber, J. (2018). World Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1803.10122. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y., Zhen, H., Chen, P., Zheng, S., Du, Y., Chen, Z., & Gan, C. (2023). 3D-LLM: Injecting the 3D World into Large Language Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2307.12981. [CrossRef]

- Hu, N., Cheng, H., Xie, Y., Li, S., & Zhu, J. (2024, September). 3D-JEPA: A Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture for 3D Self-Supervised Representation Learning. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Jesson, A., Beltran Velez, N., Chu, Q., Karlekar, S., Kossen, J., Gal, Y., Cunningham, J. P., & Blei, D. (2024). Estimating the hallucination rate of generative ai. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 31154–31201.

- Jiang, J., Hong, G., Zhou, L., Ma, E., Hu, H., Zhou, X., Xiang, J., Liu, F., Yu, K., Sun, H., Zhan, K., Jia, P., & Zhang, M. (2024). DiVE: DiT-based Video Generation with Enhanced Control. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2409.01595. [CrossRef]

- Kalapos, A., & Gyires-Tóth, B. (2024). CNN-JEPA: Self-Supervised Pretraining Convolutional Neural Networks Using Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture. 1111–1114. [CrossRef]

- Karypidis, E., Kakogeorgiou, I., Gidaris, S., & Komodakis, N. (2025a). Advancing Semantic Future Prediction through Multimodal Visual Sequence Transformers. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2501.08303.

- Kenneweg, T., Kenneweg, P., & Hammer, B. (2025). JEPA for RL: Investigating Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures for Reinforcement Learning. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2504.16591. [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, K., Zuluaga, M., Roblek, D., & Sharifi, M. (2018). Fréchet Audio Distance: A Metric for Evaluating Music Enhancement Algorithms. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1812.08466. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Jin, C., Diethe, T., Figini, M., Tregidgo, H. F., Mullokandov, A., Teare, P., & Alexander, D. C. (2024). Tackling structural hallucination in image translation with local diffusion. European Conference on Computer Vision, 87–103.

- Kissane, C., Krzyzanowski, R., Bloom, J. I., Conmy, A., & Nanda, N. (2024). Interpreting Attention Layer Outputs with Sparse Autoencoders. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2406.17759. [CrossRef]

- Kramár, J., Lieberum, T., Shah, R., & Nanda, N. (2024). AtP*: An efficient and scalable method for localizing LLM behaviour to components. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2403.00745. [CrossRef]

- Lauscher, A., Glavaš, G., & others. (2025). How Much Do LLMs Hallucinate across Languages? On Multilingual Estimation of LLM Hallucination in the Wild. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2502.12769.

- Oorloff, T., Yacoob, Y., & Shrivastava, A. (2025). Mitigating Hallucinations in Diffusion Models through Adaptive Attention Modulation. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2502.16872.

- LeCun, Y. (2022). A path towards autonomous machine intelligence version 0.9. 2, 2022-06-27. Open Review, 62(1), 1–62.

- Li, W., Wei, Y., Liu, T., Hou, Y., Li, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, Y., & Liu, L. (2024). Predicting Gradient is Better: Exploring Self-Supervised Learning for SAR ATR with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 218, 326–338. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Gui, A., Emmanouilidou, D., & Gamper, H. (2024). Rethinking Emotion Bias in Music via Frechet Audio Distance. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2409.15545. [CrossRef]

- Mahowald, K., Ivanova, A. A., Blank, I. A., Kanwisher, N., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Fedorenko, E. (2023). Dissociating language and thought in large language models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2301.06627. [CrossRef]

- Makelov, A., Lange, G., & Nanda, N. (2024). Towards Principled Evaluations of Sparse Autoencoders for Interpretability and Control. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2405.08366. [CrossRef]

- Marks, S., Rager, C., Michaud, E. J., Belinkov, Y., Bau, D., & Mueller, A. (2024). Sparse Feature Circuits: Discovering and Editing Interpretable Causal Graphs in Language Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2403.19647. [CrossRef]

- Mo, S., & Yun, S. (2024, May). DMT-JEPA: Discriminative Masked Targets for Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y. (2023). Beyond XAI:Obstacles Towards Responsible AI. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2309.03638. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., & Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2103.00020. [CrossRef]

- Rajamanoharan, S., Conmy, A., Smith, L., Lieberum, T., Varma, V., Kramár, J., Shah, R., & Nanda, N. (2024). Improving Dictionary Learning with Gated Sparse Autoencoders. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2404.16014. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P. L., Louzada, F., Ramos, E., & Dey, S. (2018). The Frechet distribution: Estimation and Application an Overview. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1801.05327. [CrossRef]

- Rani, A., Rawte, V., Sharma, H., Anand, N., Rajbangshi, K., Sheth, A., & Das, A. (2024). Visual hallucination: Definition, quantification, and prescriptive remediations. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2403.17306.

- Rathkopf, C. (2025). Hallucination, reliability, and the role of generative AI in science. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2504.08526.

- Reimering, S., Muñoz, S., & McHardy, A. C. (2018). A Fréchet tree distance measure to compare phylogeographic spread paths across trees. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 17000. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z., Wei, Y., Guo, X., Zhao, Y., Kang, B., Feng, J., & Jin, X. (2025). VideoWorld: Exploring Knowledge Learning from Unlabeled Videos. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2501.09781. [CrossRef]

- Retkowski, J., Stępniak, J., & Modrzejewski, M. (2024). Frechet Music Distance: A Metric For Generative Symbolic Music Evaluation. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2412.07948. [CrossRef]

- Rimon, Z., Jurgenson, T., Krupnik, O., Adler, G., & Tamar, A. (2024). MAMBA: an Effective World Model Approach for Meta-Reinforcement Learning. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2403.09859. [CrossRef]

- Riou, A., Lattner, S., Hadjeres, G., Anslow, M., & Peeters, G. (2024, August). Stem-JEPA: A Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Musical Stem Compatibility Estimation. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P., Meharia, P., Ghosh, A., Saha, S., Jain, V., & Chadha, A. (2024). A comprehensive survey of hallucination in large language, image, video and audio foundation models. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2405.09589.

- Saito, A., Kudeshia, P., & Poovvancheri, J. (2025, February). Point-JEPA: A Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture for Self-Supervised Learning on Point Cloud. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, L., Chughtai, B., Batson, J., Lindsey, J., Wu, J., Bushnaq, L., Goldowsky-Dill, N., Heimersheim, S., Ortega, A., Bloom, J., Biderman, S., Garriga-Alonso, A., Conmy, A., Nanda, N., Rumbelow, J., Wattenberg, M., Schoots, N., Miller, J., Michaud, E. J., … McGrath, T. (2025). Open Problems in Mechanistic Interpretability. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2501.16496. [CrossRef]

- Shazeer, N. (2020). GLU Variants Improve Transformer. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2002.05202. [CrossRef]

- Sobal, V., Zhang, W., Cho, K., Balestriero, R., Rudner, T. G. J., & LeCun, Y. (2025). Learning from Reward-Free Offline Data: A Case for Planning with Latent Dynamics Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2502.14819. [CrossRef]

- Soloveitchik, M., Diskin, T., Morin, E., & Wiesel, A. (2021a). Conditional Frechet Inception Distance. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2103.11521. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M., & Matsuo, Y. (2022). A survey of multimodal deep generative models. Advanced Robotics, 36(5–6), 261–278. [CrossRef]

- Tauman Kalai, A., & Vempala, S. S. (2023). Calibrated Language Models Must Hallucinate. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2311.14648. [CrossRef]

- Thimonier, H., Costa, J. L. D. M., Popineau, F., Rimmel, A., & Doan, B.-L. (2025, May). T-JEPA: Augmentation-Free Self-Supervised Learning for Tabular Data. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Vodolazskiy, E. (2021). Discrete Frechet distance for closed curves. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2106.02871. [CrossRef]

- Vujinović, A., & Kovačević, A. (n.d.). ACT-JEPA: Novel Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture for Efficient Policy Representation Learning.

- Wang, A., Datta, T., & Dickerson, J. P. (2024). Strategies for Increasing Corporate Responsible AI Prioritization. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2405.03855. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Cao, J., Liu, J., Zhou, X., Huang, H., & He, R. (2024). Hallo3d: Multi-modal hallucination detection and mitigation for consistent 3d content generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 118883–118906.

- Wang, Y., He, J., Fan, L., Li, H., Chen, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Driving into the Future: Multiview Visual Forecasting and Planning with World Model for Autonomous Driving. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2311.17918. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Bingham, G., Yu, A. W., Le, Q. V., Luong, T., & Ghiasi, G. (2024). Haloquest: A visual hallucination dataset for advancing multimodal reasoning. European Conference on Computer Vision, 288–304.

- Wei, J., Yao, Y., Ton, J.-F., Guo, H., Estornell, A., & Liu, Y. (2024). Measuring and reducing llm hallucination without gold-standard answers. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2402.10412.

- Weimann, K., & Conrad, T. O. F. (2024, October). Self-Supervised Pre-Training with Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture Boosts ECG Classification Performance. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Jain, S., & Kankanhalli, M. (2024). Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2401.11817. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., & Sennrich, R. (2019). Root Mean Square Layer Normalization. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1910.07467. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H., Qiu, X., Chen, P., Yang, J., Yan, X., Du, Y., Hong, Y., & Gan, C. (2024). 3D-VLA: A 3D Vision-Language-Action Generative World Model. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2403.09631. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W., Chen, W., Huang, Y., Zhang, B., Duan, Y., & Lu, J. (2023). OccWorld: Learning a 3D Occupancy World Model for Autonomous Driving. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.16038.

- Zhu, H., Dong, Z., Topollai, K., & Choromanska, A. (2025, January). AD-L-JEPA: Self-Supervised Spatial World Models with Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture for Autonomous Driving with LiDAR Data. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Huang, B., Zhang, S., Jordan, M., Jiao, J., Tian, Y., & Russell, S. (2024). Towards a Theoretical Understanding of the “Reversal Curse” via Training Dynamics. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2405.04669. [CrossRef]

- Zürn, J., Gladkov, P., Dudas, S., Cotter, F., Toteva, S., Shotton, J., Simaiaki, V., & Mohan, N. (2024). WayveScenes101: A Dataset and Benchmark for Novel View Synthesis in Autonomous Driving. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2407.08280. [CrossRef]

- Zyrianov, V., Che, H., Liu, Z., & Wang, S. (2024). LidarDM: Generative LiDAR Simulation in a Generated World. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.02903.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).