1. Introduction

The Sundarbans ecosystem, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, serves as a transitional zone in between the freshwater inputs of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna River system and the saline waters of the mighty Bay of Bengal. This dynamic environment subjects it to continuous sedimentation, which significantly impacts aquatic biodiversity [

1]. The Sundarbans mangrove forest, covering approximately 10,000 square kilometres, over the 2 countries India and Bangladesh, is home to a diverse range of flora and fauna, including the keystone species, the Bengal tiger. The region’s unique hydrological and geomorphological characteristics make it a critical area for studying the interactions between sediments and aquatic life.

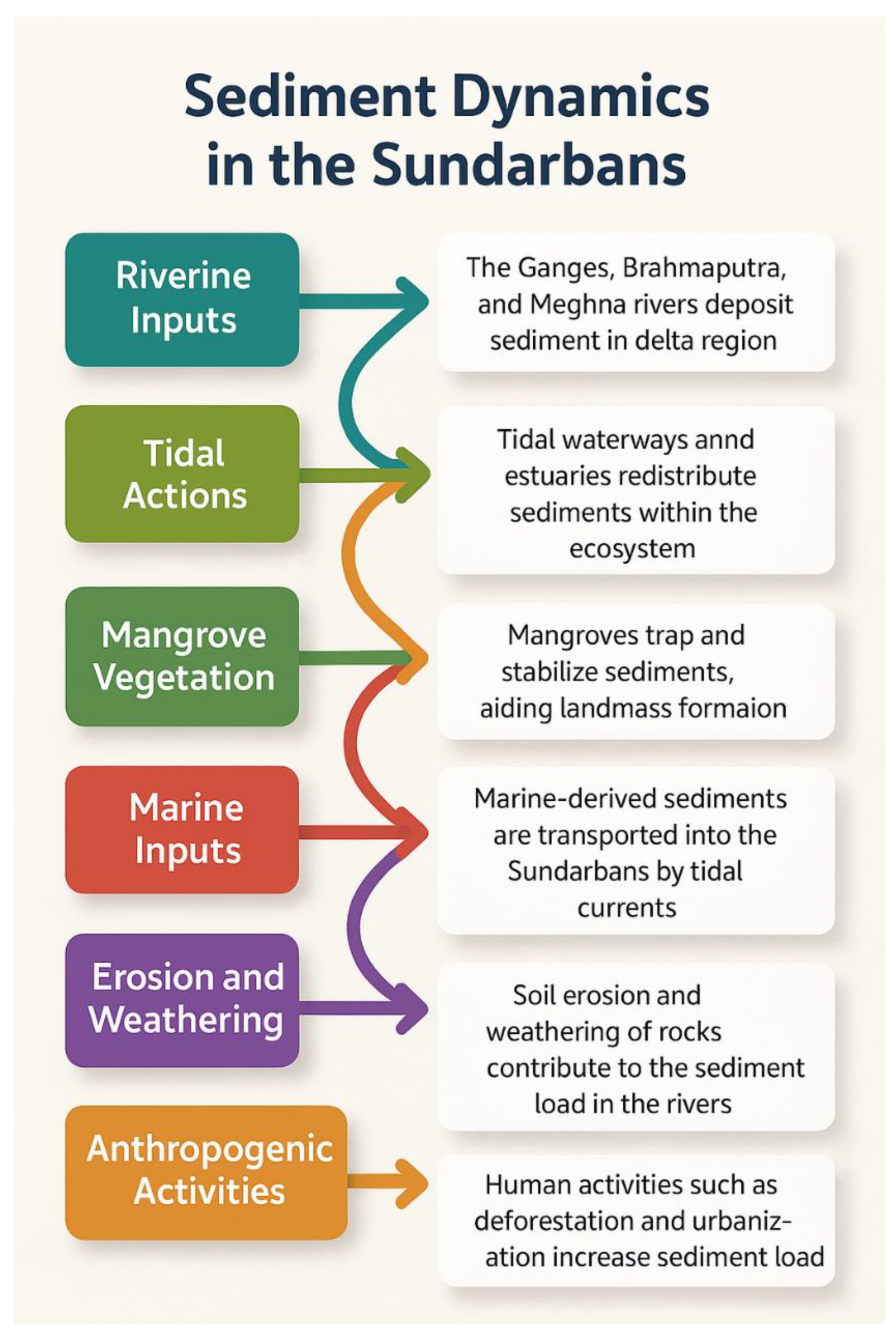

Sediments in the Sundarbans, like many other regions, originate from riverine input, tidal deposition, and anthropogenic sources. These sediments influence water transparency, dissolved oxygen levels, and the distribution of planktonic and benthic organisms. Understanding the interaction between sediment properties and aquatic life is crucial for conservation efforts, especially in the face of increasing anthropogenic pressures and climate change (

Figure 1).

Aquatic sediments in the Sundarbans originate from various sources, influenced by both natural processes and anthropogenic activities. Some key sources of aquatic sediments in the Sundarbans are mentioned above [

2].

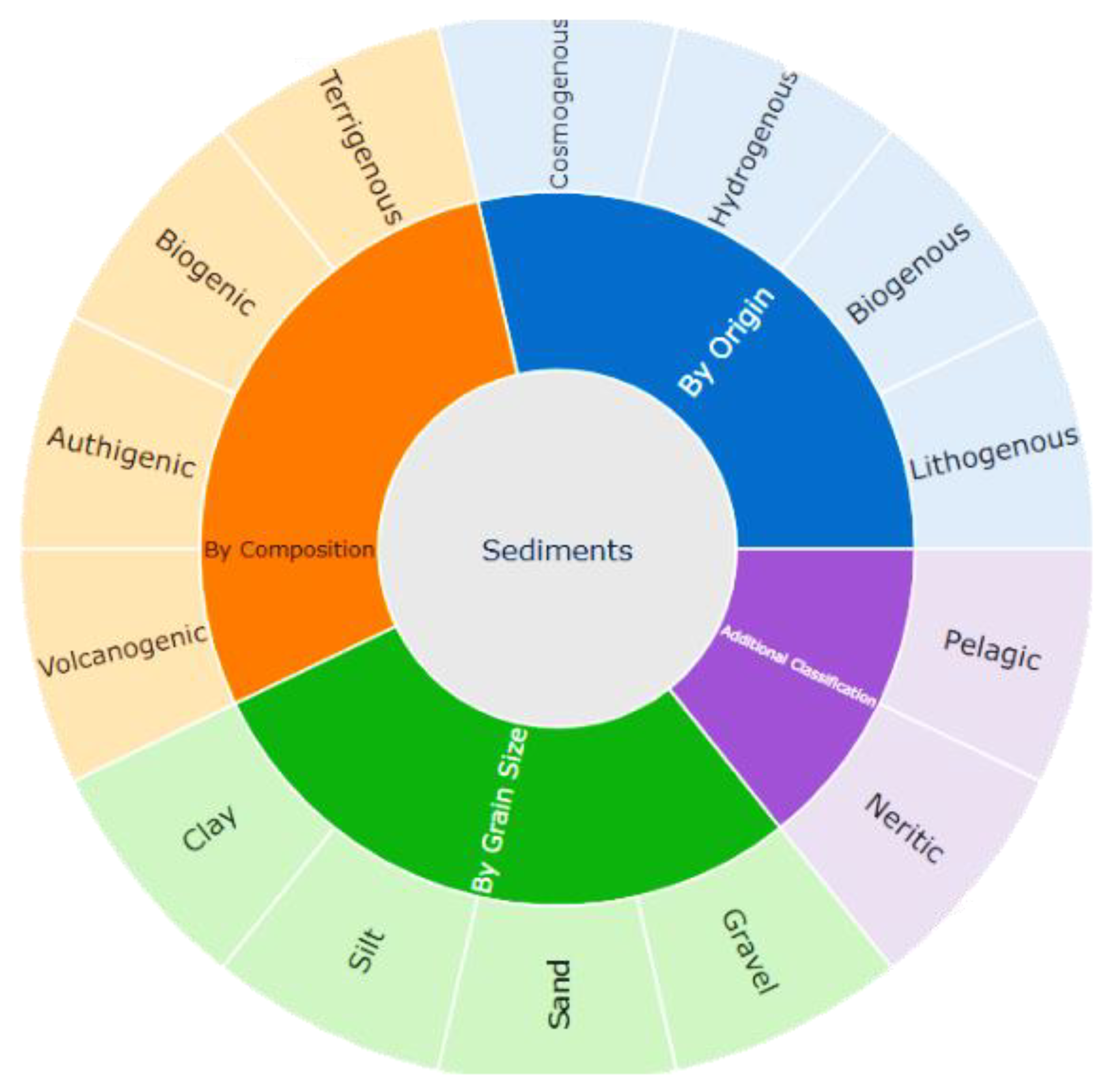

Classification of Marine Sediments- The hydrological regime of the Sundarbans is characterized by strong tidal influences, with tidal ranges of up to 6 meters. The tidal currents play a significant role in the transport and deposition of sediments, leading to the formation of extensive mudflats and tidal creeks. The sediments in the Sundarbans are also influenced by the seasonal monsoon, which brings heavy rainfall and increased river discharge, leading to higher sediment loads in the water column (

Figure 2) [

3].

Anthropogenic activity generated metal composition in Sediments

A recent study by Islam et al. revealed that the mass accumulation rates (MAR) of sediments ranged from 0.06 to 3.20 kg m⁻² y⁻¹. The sedimentation rates showed a significant increase after the year 2000, likely due to increased anthropogenic activities such as industrialization and urbanization in the region.

The high metal concentrations in the Hoogli transect were attributed to the large catchment area and significant anthropogenic inputs from industrial and urban activities [

4]. The Matla transect was less influenced by industrial activities, resulting in lower metal contamination while the Saptamukhi transect is relatively pristine, with minimal anthropogenic influence.

Residual Fractions The residual fraction was dominating at more than 80% level for Fe in all the transects and for Cu, Ni, and Co in Hugli. In Saptamukhi and Matla, more than 70% of Ni was associated with residual fraction. indicating that these metals were strongly bound to silicate minerals and were less bioavailable.

Organic Fractions: The organic fraction of Zn was quite prominent in all the transects and present in the order of Saptamukhi (36.2%) > Hugli (33.2%) > Matla (27.6%).

The highest (39.4%) association of Pb was found with organic fraction in Saptamukhi followed by Matla (27.5%), suggesting that these metals were associated with organic matter in the sediments. Carbonate-bound fractions were prominent for Mn, Cu, and Pb, indicating that these metals were bound to carbonate minerals and could be released under acidic conditions [

4].

Impact of sediments of different types of Ecosystems in Sundarban

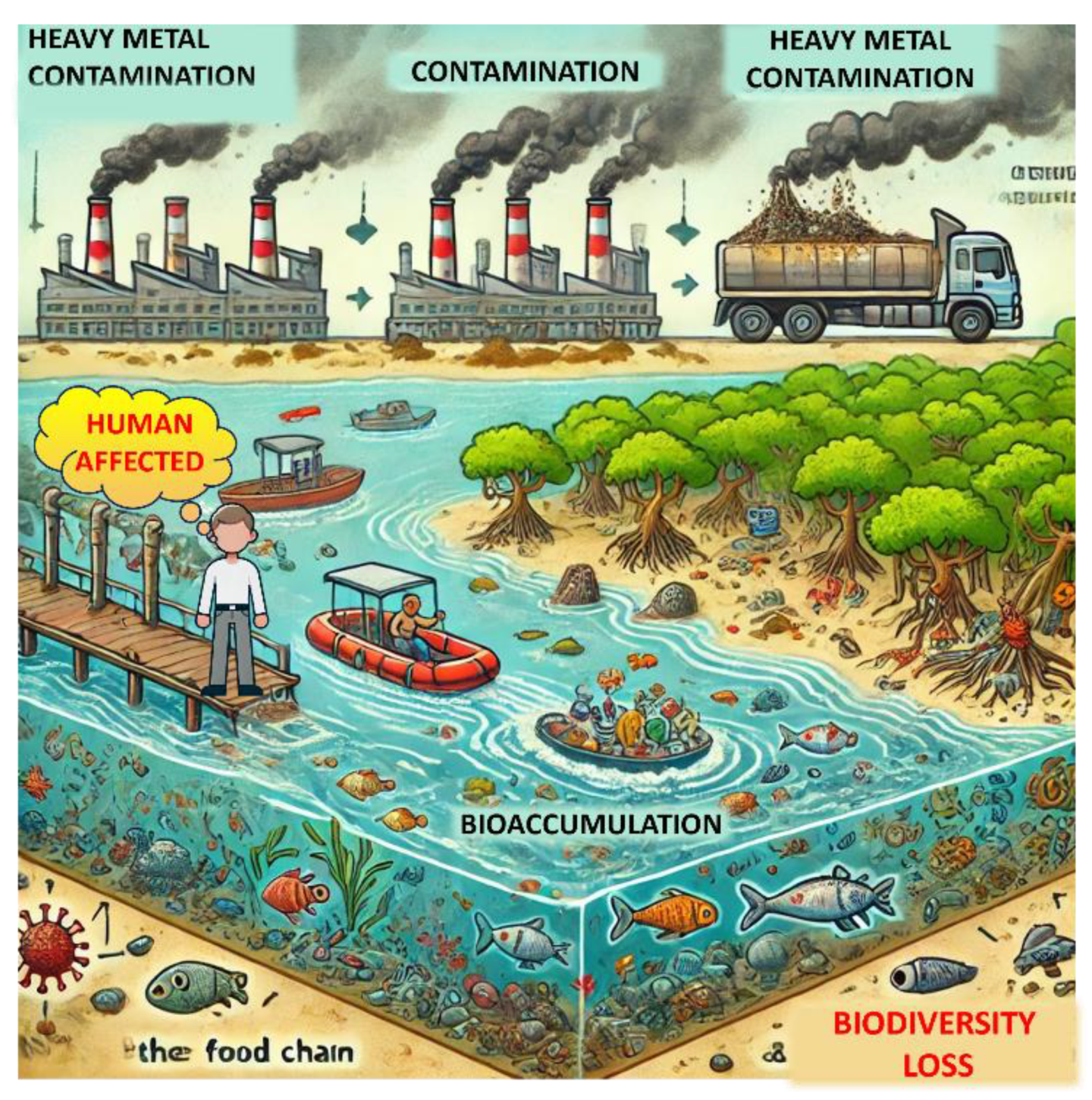

Impact of heavy metal accumulation and toxicity in the aquatic ecosystem

Zooplanktons can play an important role in serving as a potential detector of heavy metal pollution. The highest concentration was found for Fe (1552.86 µg/g) and Zn (1312.69 µg/g of dry weight of copepods). The Order of bioaccumulation was found to be Fe > Zn > Mn > Cu > Cr > Ni > Pb. One of the major discoveries found that Hooghly estuary copepods showed consistently higher metal loads, correlating with anthropogenic influence; on the other hand, in Matla, the concentration of these metals were significantly lower suggesting lesser anthropogenic activities and interference. Pb and Ni showed low accumulation, possibly due to low bioavailability or biological regulation by copepods [

5].

Another study found iron to be the highest while the toxic metals specially the Ni, Pb, and Cd were alarmingly high nearshore. Higher concentrations of Fe, Zn, Cu, Co, Cr, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Cd were found in nearshore copepods than in offshore ones indicating greater anthropogenic pollution. This was quite alarming as through bioaccumulation these toxic metals could even reach higher organisms like humans, disrupting the ecosystem. Study also needs to be done on the growth of species of zooplankton that are immune to these toxic metals over the viable ones [

6].

Using morphological and biochemical methods certain major bacterial strains were observed, petroleum-degrading bacteria included species such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

P. putida,

Mycobacterium,

Acinetobacter,

Micrococcus,

Nocardia, and

Klebsiella aerogenes. Haldia exhibited the highest percentage of petroleum-degrading bacteria (2.0% of total heterotrophs), while Cheemaguri had the lowest (0.08%). This indicates a strong correlation between industrial pollution and the abundance of hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria. Among them,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain BBW1 showed the highest degradation ability—degrading up to 78% of crude oil in 20 days and 73% within just 72 hours which is quite significant in this context. The astonishing fact was that, BBW1 exhibited plasmid-mediated resistance to multiple antibiotics (ampicillin, penicillin, cephalexin, nitrofurantoin) and heavy metals (Mn²⁺, Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Ni²⁺), carried on a single 70-kb plasmid named pBN70. This might lead to horizontal gene transfer affecting the biota. A high percentage of petroleum-degrading bacteria could mean that natural microbial diversity is declining, with pollution-tolerant species dominating and ecologically beneficial microbes getting wiped out [

7].

The rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and metal toxicity bacteria in polluted coastal waters can wipe out native microbial communities by outcompeting them through rapid replication and resistance to environmental stressors. These MDR strains often carry plasmids that encode both degradation and resistance traits, giving them a survival advantage in toxic conditions. As they proliferate, they suppress or eliminate sensitive, non-resistant microbes essential for nutrient cycling and ecological balance. These pathogens further through gene transfers, pass through the resistance, hampering the ecosystem. The loss of natural pathogens and higher growth of these is an alarming sign toward ecological breakdown of not only the microbial world but also the other organisms dependent on it for various factors.

Untreated industrial and agricultural waste discharge frequently contaminates coastal and estuarine water with conservative pollutants (such as heavy metals), many of which build up in the tissues of resident creatures like seaweed, fish, oysters, crabs, shrimp, and others. Fish is a staple diet in many regions of the world, particularly on tiny islands and along the shore, where it provides all the necessary nutrients for life processes in a balanced way. Therefore, it’s critical to look into the amounts of heavy metals in these organisms to determine whether the concentration is within acceptable bounds and won’t endanger consumers [

8]. The heavy metals in the estuary water originate from these units. Due to the poisonous nature of some heavy metals, these chemical constituents disrupt the ecology of a given ecosystem and pose a risk to human health when they reach the food chain. Numerous researchers have noted that the accumulation of pollutants in the marine environment, particularly in fish, is caused by the release of heavy metals into the sea through rivers and streams [

9].

Impact of sediments on Phytoplankton in the Sundarbans

Phytoplankton are the primary producers in aquatic ecosystems, forming the base of the food web. In the Sundarbans, phytoplankton productivity is heavily influenced by sediment deposition, nutrient availability, and light penetration. The availability of nutrients in sediments, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, plays a vital role in phytoplankton blooms, which are essential for supporting higher trophic levels [

1]. Diatoms are a major group of phytoplankton in the Sundarbans, contributing significantly to primary productivity. The study on the impact of multispecies diatom blooms on the plankton community structure in the Sundarbans [

10]. The study revealed that diatom blooms are a common occurrence in the northern regions of the Sundarbans, where sediment deposition improves water transparency by up to 4.65 times, allowing for greater light penetration and enhanced photosynthetic activity.

The availability of nutrients in sediments is a key driver of phytoplankton productivity in the Sundarbans. Studies have shown that sediment deposition enhances nutrient cycling, particularly in the northern regions where freshwater inputs from the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna river system introduce high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus [

1]. However, excessive sedimentation can lead to nutrient overloading and algal blooms, which can have detrimental effects on water quality and aquatic life.

Seasonal Variability: Diatom blooms in the Sundarbans exhibit strong seasonal variability, with peak blooms occurring during the post-monsoon period (October–December). This period is characterized by high nutrient inputs from riverine discharge and sediment deposition, establishing ideal conditions for diatom growth.

Ecological Impact: Diatom blooms play a crucial role in the Sundarbans ecosystem by supporting zooplankton populations, which in turn serve as a food source for fish and other aquatic organisms. However, excessive diatom blooms can lead to eutrophication and hypoxic conditions, particularly in areas with excessive sediment loads [

10].

Phytoplankton dynamics in the Sundarbans region reveal several key characteristics and changes over time. Diatoms are the dominant group, thriving in conditions of low salinity and high nutrient levels, with nitrate concentrations between 2.0-10.0 µM, phosphate between 0.02-0.5 µM, and silicate between 0.5-5.0 µM. The mean numerical abundance of phytoplankton increased significantly by 2007, becoming 3-fold higher than in 1990 and 2000. Notably, there were shifts in the abundance and size of key diatom species; for example, the relative abundance of

Coscinodiscus eccentricus decreased from 29.14% in 1990 to 4.59% in 2007, while its cell size increased from 0.103 to 1.11 million µm³ cell⁻¹ over the same period [

3].

Impact of sediments on Zooplankton in the Sundarbans

Zooplankton are secondary producers in aquatic ecosystems, serving as a critical link between phytoplankton and higher trophic levels such as fish. In the Sundarbans, zooplankton abundance and diversity are closely linked to sediment properties, particularly the availability of organic matter and nutrients [

11].

The study in the tidal creeks of the Sundarban estuarine system revealed a diverse zooplankton community. A total of 63 zooplankton taxa were recorded. Copepoda was the predominant group, making up 59.55% to 73.13% of the total zooplankton population [

12].

Sediments play a dual role in shaping zooplankton dynamics in the Sundarbans. On one hand, suspended sediments can filter organic matter, providing a rich feeding ground for zooplankton. On the other hand, excessive sedimentation can smother benthic habitats, reducing the availability of prey for zooplankton and other aquatic organisms [

11].

Impact of sediments on Marine Eutrophication in the Sundarbans

Eutrophication is a significant environmental issue in the Sundarbans, driven by excessive nutrient inputs from anthropogenic and natural sources [

13]. Diatoms are primary contributors to this. During eutrophication, excessive nutrient influx primarily nitrogen and phosphorus stimulates their rapid proliferation, leading to algal blooms. While diatoms initially contribute to oxygen production through photosynthesis, their overgrowth can disrupt the ecosystem. When these blooms decay, microbial decomposition consumes large amounts of dissolved oxygen, creating hypoxic (low-oxygen) conditions that can be detrimental to aquatic life. This oxygen depletion can lead to fish kills, biodiversity loss, and overall ecosystem degradation.

Impact of Sediments on Fish Populations

Fishes are a vital component of the Sundarbans ecosystem, supporting both ecological balance and local livelihoods. The distribution and abundance of fish populations in the Sundarbans are influenced by sediment properties, water quality, and the availability of food resources such as zooplankton and phytoplankton. The Sundarbans is home to a diverse range of fish species, including Hilsa (

Tenualosa ilisha), Pomfret (

Pampus argenteus), and Catfish (

Arius spp.). These species exhibit varied responses to sediment loads, with demersal fish (bottom-dwelling species) exhibits more sensitive to changes in sediment composition [

14].

High sediment loads can have both positive as well as negative effects on fish populations in the Sundarbans. While sediments provide essential nutrients that support the base of the food web, excessive sedimentation can reduce water clarity, limit light penetration, and smother benthic habitats, leading to much reduced fish populations [

14].

The impact of sedimentation on shrimp culture has been extensively studied in tidal reservoirs. Sediment stabilization in reservoirs improves water quality, enhances dissolved oxygen levels, and reduces nutrient loads, making it suitable for shrimp farming (Chanratchakool et al., 1994). However, sediment overload can lead to disease outbreaks and reduced productivity [

1].

Shrimp aquaculture is an important economic activity in the Sundarbans, providing livelihoods for thousands of people. However, the industry is vulnerable to changes in sediment dynamics, which can affect water quality and the health of the shrimp. High sediment loads can lead to the accumulation of organic matter, which can deplete oxygen levels in the water and create conditions conducive to the growth of harmful bacteria and parasites [

15].

Impact of sediments on microbial ecosystem

Sundarbans, a region of vast flora and fauna, also harbours a huge variety of microbes. These Microbial communities are essential in biogeochemical cycling, decomposing mangrove litter and recycling elements like carbon, nitrogen, sulphur, and phosphorus. In a study, among all, 6 different types of microbes were accounted for, they included, Cellulose Decomposing Bacteria (CDB), Nitrifying Bacteria, Free-living Nitrogen Fixers, Phosphorus Solubilizing Bacteria (PSB), Sulphate Reducing Bacteria (SRB), Fungi.

CDB had maximum population during post-monsoon (max: 6.189 × 10⁶ CFU/g at Station 1), especially in the deep forest due to high organic matter from accumulated litter. Fungal populations peaked in pre-monsoon, (max: 3.424 × 10⁶ CFU/g at Station 2) especially in the rooted region, and were lowest in the deep forest due to lower moisture. SRB also showed seasonal dependence, highest in pre-monsoon and lowest during monsoon thereby indicating sensitivity to waterlogging and sulphate inhibition. Nitrifying and nitrogen-fixing bacteria were highest in post/pre-monsoon depending on specific region. For Free-Living Nitrogen Fixers Highest growth was in pre-monsoon, linked to aerobic conditions and carbon availability while in cases of Nitrifying Bacteria Abundance highest in post-monsoon, lowest during monsoon; showing preferences for moderately aerobic zones. Phosphorus Solubilizing Bacteria (PSB) on the other hand Station-specific peaks, generally post-monsoon for rooted areas, monsoon for unrooted zones.

In the growth and distribution of microbial systems, the physicochemical factors like The Organic carbon content (highest in the deep forest region due to low tidal flushing and litter accumulation), Soil salinity and silicate concentration (higher in the rooted and unrooted zones, due to proximity to river input). Soil pH, salinity, and nutrient levels (nitrate, nitrite, phosphate, sulphate) (varied by season and region) played a pivotal role. Among all the factors organic carbon was shown to play the most pivotal growth in bacterial growth (R² = 77.9%, p = 0.004).

High CDB dominance indicates vigorous cellulose degradation, contributing to CO₂ and CH₄ emissions. While SRB abundance reflects anoxic sediment conditions and organic matter decomposition. And PSB and nitrifiers suggest active phosphorus and nitrogen cycling, crucial for ecosystem productivity [

16].

Identified Strains and Their Characteristics

The isolates were identified through 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The following table details the MDR strains, their identities, sampling origins, antibiotic MIC ranges, and detected resistance genes.

Dominance of Pollution-Tolerant Groups: In sediments exposed to higher loads of heavy metals and PAHs, bacteria that can tolerate or even thrive in polluted conditions—most notably certain Proteobacteria (especially Gammaproteobacteria)—become more prevalent. These groups often possess metabolic pathways or resistance mechanisms that help detoxify or degrade pollutants.

Reduction of Sensitive Taxa: Bacterial groups that are not adapted to high levels of heavy metals or aromatic hydrocarbons tend to decrease in abundance. This leads to a community structure that is more specialized for stress, with lower overall diversity in some cases. [

17]. Another one isolated was Mangrovibacter sp. SLW1, a Gram-negative pathogen isolated from Sundarbans mangrove has a draft genome of 5.53 Mbp with a G+C content of 49.45% distributed over 27 contigs [

18]. In silico analyses reveal that the genome harbors an extensive suite of metal resistance genes including multiple P-type ATPases (conferring efflux of Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cu²⁺), mntH (for cadmium uptake and efflux), and arsC (for arsenate reduction). Additional resistance mechanisms are provided by genes involved in copper resistance (proteins A, B, and C, plus the putative ABC transporter yadG), as well as corC and rcnB that maintain magnesium–cobalt and nickel–cobalt homeostasis, respectively.

In parallel, the genome encodes several key antibiotic resistance determinants such as emrR, rsmA, CRP, H-NS, and qacG, which likely contribute to broad-spectrum resistance through efflux pump regulation and target modification. Together, these findings underscore the adaptive capacity of

Mangrovibacter sp. SLW1 to withstand both heavy metal pressures and antibiotic exposure in polluted mangrove environments, positioning it as a potential model for studying microbial resilience and bioremediation in coastal ecosystems [

19].

Effect sediments on aquatic food chain

Aquatic food chains are significantly impacted by sediments, which also damage creatures directly, disrupt ecosystems, and reduce light penetration. A slew of detrimental consequences may result from this, affecting anything from fish populations to tiny algae and even the safety of food sources for human use. In Primary Producers (C. decandra, N. pubescens) Low levels of all heavy metals were found representing baseline environmental concentrations. N. pubescens shows higher uptake of Zn (19.97 µg/g) and Cu (15.81 µg/g) than C. decandra, suggesting species-specific accumulation. The Mercury (Hg) and arsenic (As) levels are very low, indicating minimal risk of bioaccumulation at this level. The entire sequence proves the initial entry of heavy metals into the trophic levels. The Benthic Crustaceans (S. serrata, P. monodon), representing the second group in trophic levels showed Very high Zn (177.55 µg/g) and Cu (60.72 µg/g) in S. serrata, typical of crustaceans due to physiological need. Most importantly Elevated Hg levels (0.171 in S. serrata) show early signs of biomagnification. S. serrata has extremely high As (8.936 µg/g), suggesting strong sediment-associated accumulation. Cd, Pb, and Cr are also higher than in producers, indicating significant environmental exposure. In Low to Mid Trophic Fish (A. mola, M. cephalus, H. nehereus, T. ilisha) A. mola has high Zn (115.82) and Hg (0.180), indicating dietary accumulation. H. nehereus shows highest Cr (4.01) and Cd (0.2295), reflecting contaminated habitats. T. ilisha has highest As (5.041) among all fish, possibly due to planktonic feeding in contaminated waters. The General trend that was found hee was of increasing Hg, Pb, and As from crustaceans towards mid-trophic fish Finally coming to the Top Predators (L. calcarifer, A. berda, H. limbatus, P. argenteus) A. berda has the highest Hg (0.350), consistent with biomagnification up the food chain. P. argenteus shows high As (3.609) and Cr (3.14), suggesting accumulation from lower trophic prey. while Zn and Cu levels remain moderate, likely regulated physiologically. Cd and Pb remain low, but Hg and As show clear biomagnification risk. Zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) are essential trace elements. Their levels vary irregularly across trophic levels. This is due to species-specific physiological regulation rather than bioaccumulation. Mercury (Hg) and arsenic (As) are on the other hand non-essential and toxic. They show a progressive increase across trophic levels in the Sundarban ecosystem indicating biomagnification in aquatic food chains [

20].

Management of aquatic sediments in Sundarban

Sediments are a key factor in the ecological dynamics of the Sundarbans, affecting water chemistry, primary production, and aquatic biodiversity. While sedimentation can have positive effects on productivity and nutrient cycling, excessive sediment loads and contamination pose significant threats to the ecosystem. Sustainable management practices are necessary to mitigate these impacts and preserve the biodiversity of this unique mangrove habitat, else with the increasing levels of sedimentations, the Sundarbans will face tremendous challenges that will leave no stone unturned to affect the human as well as the animal population across India (Especially West Bengal) and Bangladesh. Another page of it is that, this is not only the story of Sundarbans, the same trend is replicated across the other parts of the world, making it a global concern, needing immediate attention of the international bodies, for instance, stunningly at the Baltic coast, V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus cells have been observed to survive within biofilms grown on microplastics (<5mm). This proves the globality of this concern [21]. Sediments and related pollutants, whether in pristine, protected areas or industrialized coastal zones, provide platforms (or “rafts”) for microbial colonization and gene exchange.

-

1.

Sedimentation and Erosion Control

Vegetative Buffer & Riparian Restoration: Establish wide buffers along riverbanks and coastal fringes using native vegetation. Such zones not only trap sediments and stabilize soils but also provide critical habitats for wildlife. Integrating riparian zone reconstruction with traditional buffer strips ensures a dual ecological and erosion control benefit.

Engineered Sediment Traps and Check Structures: Construct sediment basins, check dams, and diversion channels at key locations to intercept and capture sediments. Designs should incorporate modular and adaptive elements so that they can be fine-tuned based on real-time sedimentation data.

Innovative Erosion Control Methods: Implement a combination of contour ploughing, no-till farming, terracing, and the use of biodegradable geotextiles to reduce erosion. Advanced surface stabilization methods can complement these practices, especially in high-risk areas.

Advanced Monitoring and Predictive Analytics: Utilize drones, remote sensing, and IoT sensor networks for continuous measurement of sedimentation rates. These technologies, coupled with predictive analytics, can highlight erosion hotspots early—allowing for timely interventions before significant damage occurs.

Integrated Watershed Management: Develop and implement comprehensive watershed plans that harmonize agricultural practices, urban development, and conservation. Stakeholder collaboration ensures that sediment management is both scientifically informed and locally viable.

-

2.

Heavy Metal Remediation

Enhanced Phytoremediation: Use hyperaccumulator plant species—selected based on local heavy metal profiles—to absorb and store contaminants. Integrating these with periodic biomass harvesting can gradually decontaminate soils and sediments.

Composite Soil Amendments: Mix amendments such as biochar, lime, clay minerals, and organic compost to immobilize heavy metals in soils, thereby reducing their bioavailability and toxicity. The combination can also improve soil structure and fertility.

Targeted Bioremediation: Employ bioaugmentation (introducing specialized microorganisms) and biostimulation (enhancing native microbial activity) techniques to transform heavy metals into less toxic forms. Continuous research into microbial consortia can further optimize these approaches.

Cutting-Edge Nanotechnology & Genetic Approaches: Explore the use of functionalized nanomaterials to adsorb heavy metals more efficiently. Simultaneously, research into genetically engineered organisms with enhanced remediation capabilities can offer breakthrough solutions in the future.

Robust Policies and Regulatory Frameworks: Strengthen and enforce regulations on industrial emissions, waste disposal, and heavy metal discharge. Financial incentives and strict penalties can motivate industries to adopt cleaner, more sustainable technologies.

-

3.

Improving Turbidity and Light Penetration

Selective, Ecosystem-Sensitive Dredging: Undertake dredging campaigns that prioritize minimal disruption to aquatic habitats. Employ methods that ensure sediments are removed without excessive resuspension, and follow up with habitat restoration where needed.

Comprehensive Sediment Control Techniques: Incorporate silt fences, sediment ponds, and erosion control blankets in vulnerable areas. These measures should be integrated into broader urban and rural planning, with green infrastructure (like permeable pavements, rain gardens, and green roofs) reducing stormwater runoff.

Riparian and Coastal Zone Reclamation: Restore and conserve vegetation along waterways to act as natural filters, trapping sediment and enhancing water clarity. By combining structural and natural solutions, these zones help regulate light penetration essential for aquatic ecosystems.

Community Science and Engagement Platforms: Foster community involvement in regular water quality monitoring and reporting. Citizen-led initiatives—combined with scientific oversight—can offer early warnings and serve as a catalyst for local environmental stewardship.

-

4.

Nutrient Management to Counter Eutrophication

Precision Nutrient Management: Work with agricultural stakeholders to implement nutrient management plans that use precision farming techniques, crop rotation, and optimized fertilizer application. This minimizes runoff and curtails the nutrient load reaching water bodies.

Constructed and Preserved Wetlands: Design constructed wetlands that simulate natural filtration processes to remove excess nutrients. Equally, conserve natural wetlands to maintain their invaluable role as nutrient sinks in the ecosystem.

Vegetative Buffer Zones with Dual Functionality: Expand traditional buffer strips to serve both sediment interception and nutrient absorption. Using a diversity of native plants maximizes nutrient uptake while enhancing biodiversity.

-

5.

Preserving Zooplankton Diversity and Abundance

Targeted Habitat Restoration: Safeguard and restore key zooplankton habitats such as wetlands, estuaries, and coastal lagoons. Protected areas help maintain stable and diverse zooplankton populations, which are critical to aquatic food webs.

Integrated Water Quality Improvement: Lower pollutant and nutrient inputs to create conditions that favor zooplankton health. This strategy includes controlling runoff, reducing chemical discharges, and continuous water quality monitoring.

Adaptive Ecological Management: Deploy advanced sensor networks and ecological monitoring systems to track changes in zooplankton populations. Adaptive management practices can be refined over time based on real-world data and predictive models.

Climate Resilience Initiatives: Develop strategies specifically to mitigate climate-induced stressors. Adaptive measures might include engineered refuges or localized microclimate adjustments that keep water temperatures within optimal ranges.

-

6.

Reducing Fish Mortality and Preventing Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation

Stringent Pollution Control Measures: Implement and enforce tight controls on both industrial and agricultural pollutants through modern treatment technologies and strict regulatory oversight.

Habitat Enhancement and Fishery Management: Enhance natural habitats with artificial reefs, spawning grounds, and restoration projects that support resilient fish populations. Moreover, use selective fish stocking programs to maintain robust populations with species less susceptible to heavy metal accumulation.

Robust Public Awareness and Education Campaigns: Educate communities about the impacts of heavy metals and encourage practices that reduce pollutant loads. Informed citizenry can drive demand for cleaner production methods and sustainable fisheries.

System-Wide Bioremediation Integration: Combine pollution controls and bioremediation efforts within aquatic systems to address heavy metal contamination holistically. Integrated remediation minimizes bioaccumulation in fish and preserves both ecosystem and human health.

-

7.

Managing Diatom Blooms and Oxygen Depletion

Aggressive Nutrient Input Reduction: Target nutrient sources from agriculture, wastewater, and industrial discharges. Upgraded treatment plants and revised nutrient discharge standards are key to preventing diatom and harmful algal blooms.

Innovative Aeration and Natural Mixing Solutions: Use mechanical aerators, solar-powered mixers, and wind-driven circulators to boost oxygen levels in water bodies. These systems help counteract hypoxic conditions while supporting aerobic aquatic life.

Proactive Algal Bloom Surveillance: Develop early warning systems using satellite imagery, real-time sensors, and community science networks. Early detection facilitates rapid responses through algaecides, biological controls, or dilution strategies.

Integrated Ecosystem Management: Establish a comprehensive framework linking nutrient management, aeration, and water quality monitoring. Multifaceted plans that engage local governments, research institutions, and community groups ensure that interventions are timely and effective.

Cross-Sector Partnerships: Promote collaborations between environmental agencies, policy makers, and research centers to innovate integrated solutions and share best practices for managing diatom blooms and associated oxygen deficits.

-

8.

Prevention of MDR Pathogens in Sediments

Preventing the formation and spread of MDR pathogens in sediments involves targeted strategies that reduce the sources of antibiotic selection pressure and carefully manage microbial communities:

Advanced Wastewater Treatment Upgrades: Increase treatment standards to remove both antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria from wastewater effluent. Upgrades include membrane bioreactors, UV disinfection, and ozonation that help target both chemical residues and existing pathogens before they settle into sediments.

Strict Prescription and Dispensation Controls: Implement and enforce tighter regulatory controls over antibiotic usage in healthcare and agriculture. Proper waste disposal and guidelines can significantly reduce the antibiotic residues entering natural water bodies.

Microplastic Reduction Initiatives: Reduce microplastic pollution, since microplastics can serve as surfaces supporting biofilm formation, where MDR pathogens tend to thrive. Policies such as the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive and India’s Plastic Waste Management Rules aid this cause.

In Situ Bioremediation and Microbial Management: Investigate approaches such as introducing beneficial microbial consortia that outcompete or inhibit MDR pathogens within sediments. Strategies may include targeted phage therapies or microbial remediation processes that shift community dynamics toward less harmful profiles.

Real-Time Molecular Monitoring: Utilize advanced molecular tools like quantitative PCR, metagenomics, and biosensors to monitor the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and MDR pathogens in sediment samples. Early detection can inform targeted interventions before resistant strains spread further.

One Health Approach: Foster interdisciplinary cooperation between environmental scientists, healthcare professionals, and agricultural experts. A One Health framework emphasizes the interconnection between human, animal, and ecosystem health—thus, it’s integral to preventing the emergence and propagation of MDR pathogens across all sectors.