Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

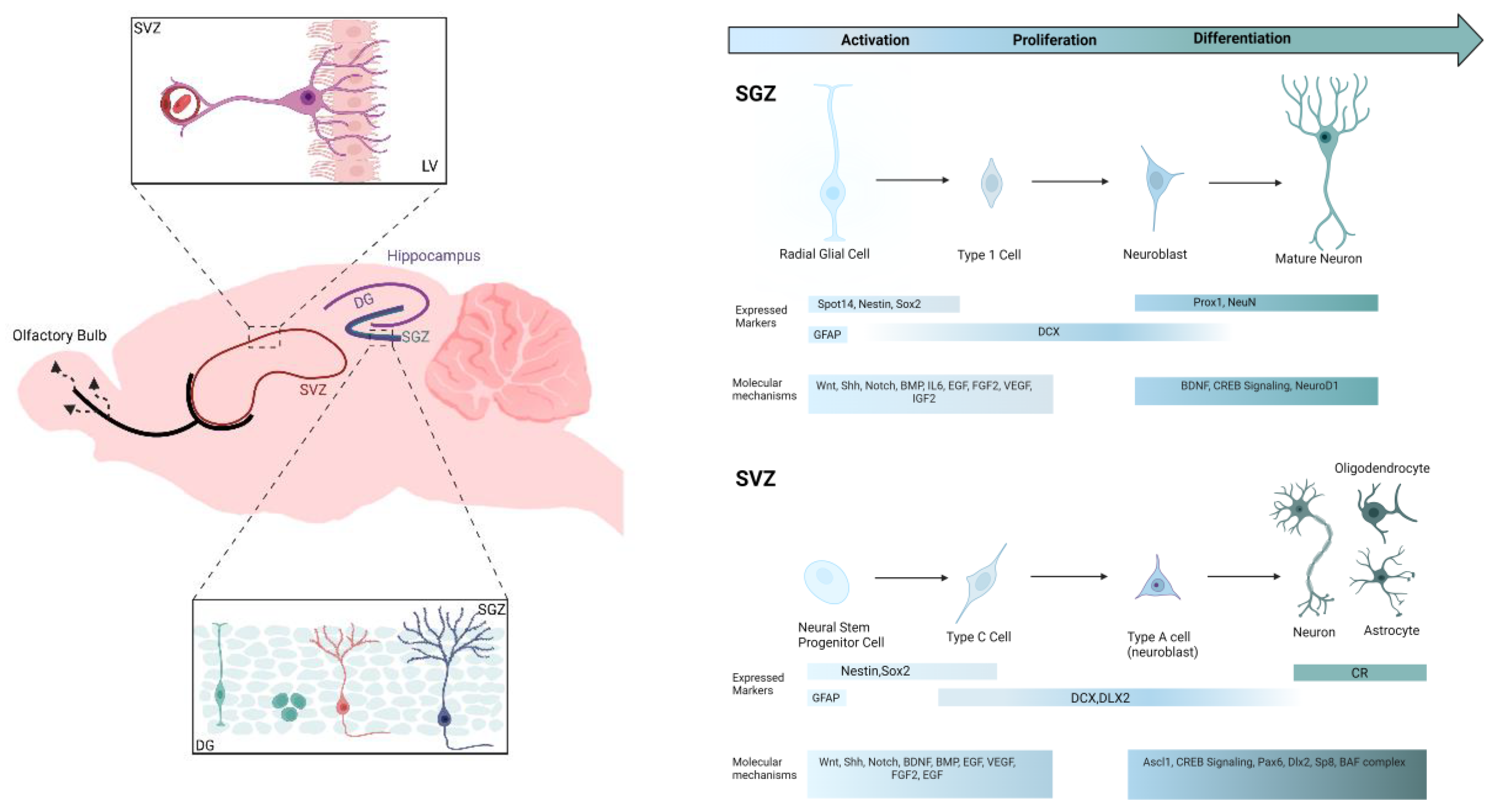

Adult Neurogenesis: Neurogenic Niches and Biomarkers

Hippocampal and SVZ Brain Plasticity

Molecular Biomarkers

Ultrasound Effect on Neurons: Then and Now

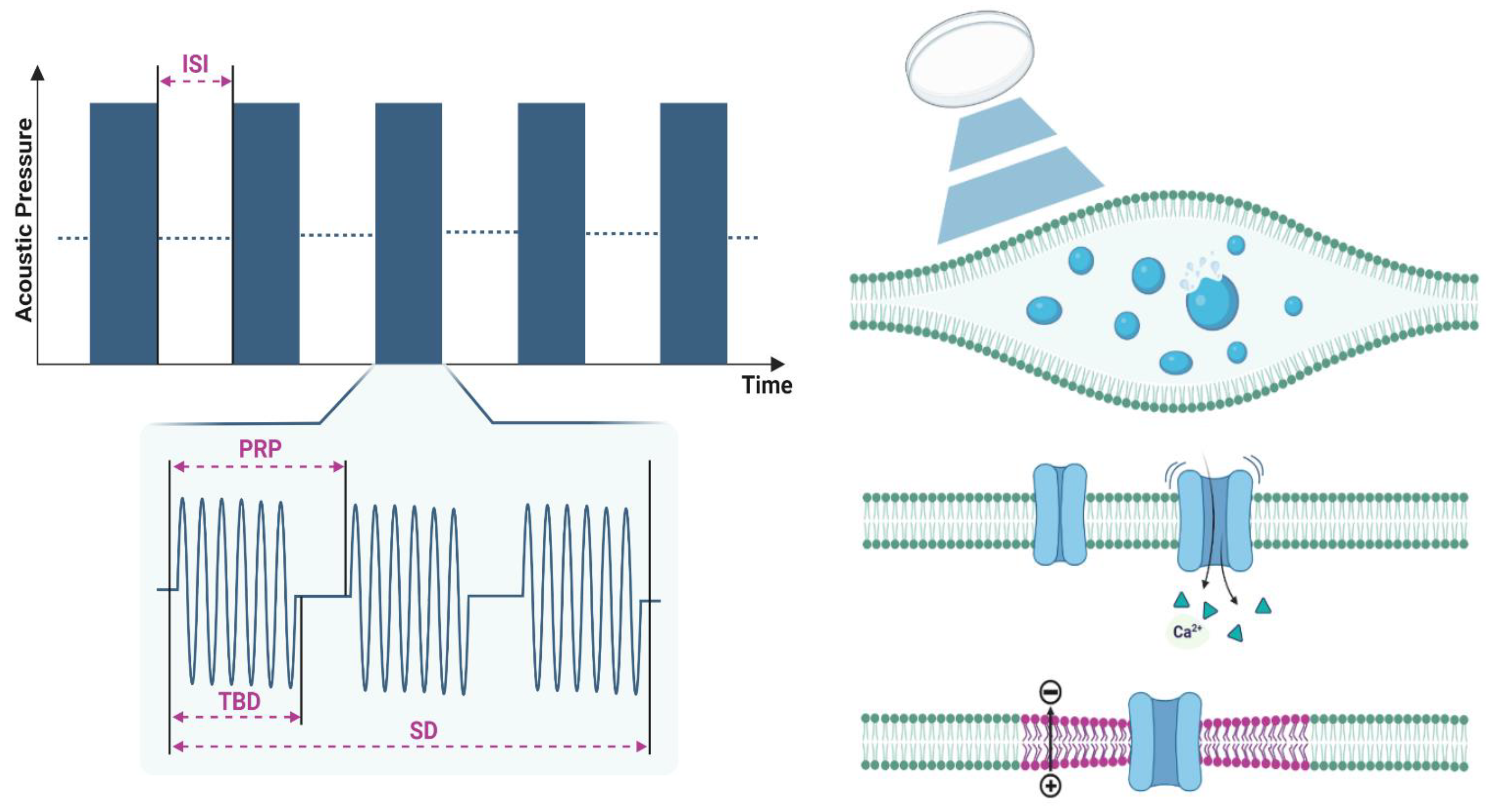

Physical Properties

Mechanism of LIFUS Effect on Neurons

Intramembrane Cavitation

Mechanosensitive Ion Channels

Membrane Conformational Changes

Ultrasound Induced-Neurogenesis

In-Vitro Applications

In-Vivo Applications

| Study | Cell Culture | F MHz |

PRF Hz |

DC % |

TBD ms |

Ispta mW/cm2 |

Isppa W/cm2 |

SD min |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [148] | Schwann cells | 1 | 20 | - | - | 0.3 | 3 | ↑IL-1, ↓IL-6, ↓TNF-α | |

| [150] | iPSCs–NCSCs | 1 | 100 | 20 | - | 500 | - | 10 | ↑NF-M, ↑S100β, ↑GFAP |

| [91] | NSPC cultures | 1.8 | 20 | - | - | 100 to 500 | - | 5 | ↑NGF, ↑MAP-2, ↑GFAP, ↑NO |

| [116] | Rat brain astrocyte cells | 1 | 10 | 50 | 50 | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF, ↑GDNF, ↑VEGF ↑GLUT1 |

| [124] | hBM-MSC | 0.04 | - | - | - | 50 | - | 60 | ↑MAP2, ↑ND1, ↑NF-L,↑Tau, ↑DCX ↑NESTIN, ↑p-CREB, ↑p-ERK |

| [147] | PC12 | 1 | 100 | 20 | - | 50 | - | 10 | ↑p-ERK1/2 ↑p-Akt ↑p-CREB ↑Trx-1 |

| [155] | hAD-MSC | 0.25 | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 30 | - | 30 | ↑ERK1/2, ↑Akt, ↑Cyclin D1, ↑Cyclin E1, ↑Cyclin A2, and ↑Cyclin B1 |

| [158] | Rat astrocyte cell line | 1 | 10 | 50 | 50 | 110 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF, ↑NF-κB, ↑ TrkB/PI3K/Akt, ↑Ca/CaMK |

| [152] | NSCs | 4.36 | - | - | - | 496 | - | 10 | no differentiation |

| [156] | Schwann cells | 1 | - | - | - | 27.37 | - | 10 | ↑FGF, ↑NGF, ↑BDNF, ↑GDNF, ↑Cyclin D1 |

| [149] | Rat BMSC | 1 | - | - | - | 50 | - | 3 | ↑BDNF, ↑NGF |

| [163] | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | 1.5 | 1000 | - | 0.2 | 30 +- 5.0 | - | 20 | ↑YAP/TAZ |

| [154] | hBM-MSC | 1.5 | 1000 | 20 | - | 50 or 60 | - | 5 | ↑PI3K/AKt ↑Cyclin D1 |

| [115] | NSCs | 1 | - | - | - | 69.3 | - | 5 | ↑NeuN, ↓GFAP, ↑NGF, ↑NT-3, ↑BDNF |

| [41] | SH-SY5Y and primary glial cells | 1.5 | 1000 | 20 | - | 15 | - | 5 | ↑BDNF, ↑DCX |

| [157] | human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma | 1.5 | 100 | 20 | - | 60 | - | 20 | ↑ERK1/2, ↑p-ERK |

| Study | Animal Model | Brain Targets |

F MHz |

PRF Hz | DC % | TBD ms | Ispta mW/cm2 | Isppa W/cm2 | SD mins | Outcome |

| [30] | Healthy wild-type mice | Unilateral hippocampi | 0.35 | 1500 | - | 0.0002 | 36.2 | - | 30 | ↑BDNF+ |

| [38] | AD in SD rats | Bilateral hippocampi | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF, ↑GDNF, ↑VEGF ↓AChE, ↓Aβ |

| [116] | MS in male SD rats | Bilateral hemispheres | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF, and ↑GDNF, =VEGF, =GLUT1 |

| [124] | Ischemic model in C57BL/6N mice | Whole brain | 0.04 | - | - | - | 50 | - | 20 | ↑p-ERK, ↑p-CREB |

| [89] | Healthy C57BL/6 mice | Unilateral hippocampi | 1.68 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 81.12 | - | 2 | =BrdU-NeuN or DCX |

| [117] | BCCAO in rats | Bilateral hemispheres | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF |

| [118] | TBI in male C57BL/6 J mice | Injured cortical areas | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 5 | ↑BDNF, ↑VEGF, ↑TrkB/Akt-CREB, =GDNF |

| [120] | MCAO in C57BL/6 mice | Injured cortical area | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF |

| [123] | VD in male C57BL/6 mice | Whole brain | 1.875 | 6000 | - | - | 90 | - | 20 | ↑t-eNOS, ↑CXCR4, ↑FGF2, ↑VEGF, ↑NGF |

| AD in 5XFAD transgenic mice | Whole brain | 1.875 | 6000 | - | - | 90 | 20 | ↑t-eNOS, ↓Aβ, ↑Hsp 90, ↑NGF, ↑pro-BDNF, =VEGF | ||

| [119] | dMCAO in adult male SD rats | Whole brain | 0.5 | 1000 | - | 0.5 | - | 2.6 | 10 | ↑ BDNF |

| [121] | MCAO in C57BL6J mice | Injured cortical area | 1 | 1 | 50 | - | 528 | - | 15 | ↑BDNF and ↑Bcl-2/ Bax |

| [90] | AD in male C57BL/6 J mice | Hippocampus and Cortex | 1 | 1 | 5 | - | 528 | - | 15 | ↑TLR4/NF-κB, ↑CREB/BDNF, ↓TNF-α, ↓IL-1β, ↓IL-6 |

| [162] | MCAO in adult male ICR mice | Ipsilateral hemisphere | 0.5 | 1000 | - | 0.5 | 120 | - | 10 | ↑M2 microglia, ↑IL-10, ↑IL-10R |

| [41] | Female C57BL/6 mice treated with demyelinating drug CPZ | Whole brain | 1.5 | 1000 | 20 | - | 25 | - | 20 | ↑DCX, ↑BDNF |

| [39] | AD in Wistar male rats | Whole brain | 3.3 | 100 | 50 | 5 | - | 0.8 | 5 | ↑BDNF, ↑NGF-β, ↑IL-10 |

| [40] | MCAO in Wild-type mice | Whole brain | 0.5 | 780 | - | 0.064 | 193 | - | 20 | ↑VEGF, ↑eNOS, ↑DCX+, ↑SDF-1α, ↑CXCR4 |

| [33] | Aged C57BL/6 wild-type mice | Whole brain | 1 | 10 | 10 | 20000 | 120 | - | 4 | ↑DCX |

| [87] | Healthy wildtype mice | Whole brain | 1 | 1000 | 1 | 5 | - | 5 | ↑DCX, ↑p-ERK | |

| [122] | PD model in Female SD rats | Right striatum | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 528 | - | 5 | ↑GDNF, ↓LCN2, ↓IL-1β |

| [161] | TBI in male C67BL/6 N rat | Hippocampus | 0.8 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 10 | ↑Brdu+NeuN+, ↑Dcx |

| [160] | PD in C57BL/6 wild-type mice | CA1 area | 1 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 8.67 | - | 25 | ↑LFP |

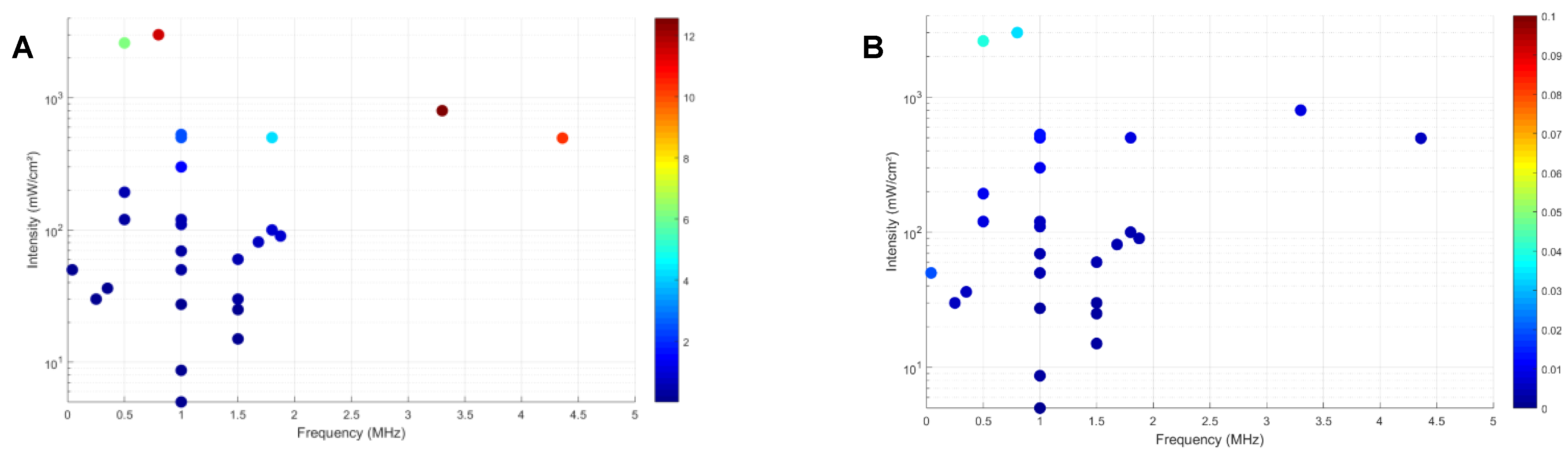

Ultrasound Parameters

Future Perspectives

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Kirmani, B.F., L.A. Shapiro, and A.K. Shetty, Neurological and neurodegenerative disorders: novel concepts and treatment. Aging and disease, 2021. 12(4): p. 950. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M., et al., Stem cell transplantation therapy and neurological disorders: current status and future perspectives. Biology, 2022. 11(1): p. 147. [CrossRef]

- Lamptey, R.N., et al., A review of the common neurodegenerative disorders: current therapeutic approaches and the potential role of nanotherapeutics. International journal of molecular sciences, 2022. 23(3): p. 1851. [CrossRef]

- Cenini, G., A. Lloret, and R. Cascella, Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases: from a mitochondrial point of view. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2019. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Elfawy, H.A. and B. Das, Crosstalk between mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and age related neurodegenerative disease: Etiologies and therapeutic strategies. Life sciences, 2019. 218: p. 165-184. [CrossRef]

- Russo, I., S. Barlati, and F. Bosetti, Effects of neuroinflammation on the regenerative capacity of brain stem cells. Journal of neurochemistry, 2011. 116(6): p. 947-956. [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G., et al., Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2017. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Christen, Y., Oxidative stress and Alzheimer disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2000. 71(2): p. 621S-629S.

- Yuan, T.-F., et al., Oxidative stress and adult neurogenesis. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 2015. 11: p. 706-709. [CrossRef]

- Rubinsztein, D.C., How does the Huntington's disease mutation damage cells? Science of Aging Knowledge Environment, 2003. 2003(37): p. pe26-pe26.

- Lücking, C. and A. Brice*, Alpha-synuclein and Parkinson's disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS, 2000. 57: p. 1894-1908.

- Bayés-Genis, A., A. González, and J. Lupón, ST2 in Heart Failure. 2018. p. e005582.

- Winner, B., Z. Kohl, and F.H. Gage, Neurodegenerative disease and adult neurogenesis. European Journal of Neuroscience, 2011. 33(6): p. 1139-1151. [CrossRef]

- Terreros-Roncal, J., et al., Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science, 2021. 374(6571): p. 1106-1113. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.M., et al., Physiological changes in neurodegeneration—mechanistic insights and clinical utility. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2018. 14(5): p. 259-271. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S., et al., Current therapies for neurological disorders and their limitations, in Phytonutrients and Neurological Disorders. 2023, Elsevier. p. 107-130.

- Vashist, A., et al., Recent advances in nanotherapeutics for neurological disorders. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 2023. 6(7): p. 2614-2621.

- Beisteiner, R., M. Hallett, and A.M. Lozano, Ultrasound neuromodulation as a new brain therapy. Advanced Science, 2023. 10(14): p. 2205634. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S., et al., Direct inductive stimulation for energy-efficient wireless neural interfaces. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2012. 2012: p. 883-6.

- Cheyuo, C., M. Aziz, and P. Wang, Neurogenesis in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Role of MFG-E8. Front Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 569. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.K., et al., Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2021. 17(2): p. 75-87. [CrossRef]

- Elias, W.J., et al., A randomized trial of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016. 375(8): p. 730-739. [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.E., et al., Safety and efficacy of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for patients with medication-refractory, tremor-dominant Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA neurology, 2017. 74(12): p. 1412-1418. [CrossRef]

- Croft, P.G., The assessment of pain perception. Journal of Mental Science, 1952. 98(412): p. 427-432.

- Kubanek, J., Neuromodulation with transcranial focused ultrasound. Neurosurgical focus, 2018. 44(2): p. E14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., et al., Excitatory-inhibitory modulation of transcranial focus ultrasound stimulation on human motor cortex. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 2023. 29(12): p. 3829-3841. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y., K. Hynynen, and N. Lipsman, Applications of focused ultrasound in the brain: from thermoablation to drug delivery. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2021. 17(1): p. 7-22. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.N. and K.A. Mesce, A review of the bioeffects of low-intensity focused ultrasound and the benefits of a cellular approach. Frontiers in physiology, 2022. 13: p. 1047324. [CrossRef]

- Badawe, H.M., P. Raad, and M.L. Khraiche, High-resolution acoustic mapping of tunable gelatin-based phantoms for ultrasound tissue characterization. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2024. 12: p. 1276143. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, Y., et al., Transcranial pulsed ultrasound stimulates intact brain circuits. Neuron, 2010. 66(5): p. 681-694. [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, D.G., D. Razansky, and J. Götz, Ultrasound as a versatile tool for short-and long-term improvement and monitoring of brain function. Neuron, 2023. 111(8): p. 1174-1190. [CrossRef]

- Badawe, H.M., et al., Experimental and Computational Analysis of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Thermal Ablation in Breast Cancer Cells: Monolayers vs. Spheroids. Cancers (Basel), 2024. 16(7). [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, D.G., et al., Low-intensity ultrasound restores long-term potentiation and memory in senescent mice through pleiotropic mechanisms including NMDAR signaling. Molecular Psychiatry, 2021. 26(11): p. 6975-6991. [CrossRef]

- Khraiche, M.L., et al. Ultrasound induced increase in excitability of single neurons. in 2008 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2008. IEEE.

- Blackmore, J., et al., Ultrasound neuromodulation: a review of results, mechanisms and safety. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2019. 45(7): p. 1509-1536. [CrossRef]

- Badawe, H., J.P. Harouz, and M. Khraiche. Effect of Ultrasound-Induced Temperature on the Dynamics of the Hodgkin-Huxley Neuron. in 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). 2024. IEEE.

- Badawe, H. and M. Khraiche, Modeling of Calcium-dependent Low Intensity Low Frequency Ultrasound Modulation of a Hodgkin–Huxley Neuron. Proceedings of EMBC 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2023/7.

- Lin, W.-T., et al., Protective effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on aluminum-induced cerebral damage in Alzheimer's disease rat model. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 9671. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Tramontin, N., et al., Effects of low-intensity transcranial pulsed ultrasound treatment in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, 2021. 47(9): p. 2646-2656. [CrossRef]

- Ichijo, S., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy promotes recovery from stroke by enhancing angio-neurogenesis in mice in vivo. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 4958. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., et al., Exploratory study on neurochemical effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound in brains of mice. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, 2021. 59: p. 1099-1110. [CrossRef]

- Habli, Z., et al., Single-cell fluid-based force spectroscopy reveals near lipid size nano-topography effects on neural cell adhesion. Lab Chip, 2024. 24(4): p. 707-718. [CrossRef]

- Leal-Galicia, P., et al., Adult neurogenesis: a story ranging from controversial new neurogenic areas and human adult neurogenesis to molecular regulation. International journal of molecular sciences, 2021. 22(21): p. 11489. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M., A.-C. Petit, and P.-M. Lledo, The impact of adult neurogenesis on affective functions: of mice and men. Molecular Psychiatry, 2024: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., et al., Versatile strategies for adult neurogenesis: Avenues to repair the injured brain. Neural Regeneration Research, 2024. 19(4): p. 774-780. [CrossRef]

- Urbán, N. and F. Guillemot, Neurogenesis in the embryonic and adult brain: same regulators, different roles. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 2014. 8: p. 396. [CrossRef]

- Lie, D.C., et al., Neurogenesis in the adult brain: new strategies for central nervous system diseases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 2004. 44: p. 399-421. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Buylla, A. and D.A. Lim, For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron, 2004. 41(5): p. 683-686.

- Lledo, P.-M., M. Alonso, and M.S. Grubb, Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2006. 7(3): p. 179-193. [CrossRef]

- Sahay, A., et al., Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature, 2011. 472(7344): p. 466-470. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-D., et al., Hypothalamic modulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice confers activity-dependent regulation of memory and anxiety-like behavior. Nature neuroscience, 2022. 25(5): p. 630-645. [CrossRef]

- Chamaa, F., et al., Thalamic stimulation in awake rats induces neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Brain stimulation, 2016. 9(1): p. 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Chamaa, F., et al., Long-term stimulation of the anteromedial thalamus increases hippocampal neurogenesis and spatial reference memory in adult rats. Behavioural brain research, 2021. 402: p. 113114. [CrossRef]

- Chamaa, F., et al., Sustained activation of the anterior thalamic neurons with low doses of Kainic Acid boosts hippocampal neurogenesis. Cells, 2022. 11(21): p. 3413. [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.-l. and H. Song, Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron, 2011. 70(4): p. 687-702. [CrossRef]

- Fontán-Lozano, Á., et al., To become or not to become tumorigenic: subventricular zone versus hippocampal neural stem cells. Frontiers in Oncology, 2020. 10: p. 602217. [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G., H. Song, and F.H. Gage, Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2015. 7(9): p. a018812.

- Ehninger, D. and G. Kempermann, Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Cell and tissue research, 2008. 331: p. 243-250.

- Christian, K.M., H. Song, and G.-l. Ming, Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annual review of neuroscience, 2014. 37: p. 243-262. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.A. and A. Alvarez-Buylla, The adult ventricular–subventricular zone (V-SVZ) and olfactory bulb (OB) neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2016. 8(5): p. a018820. [CrossRef]

- Nissant, A., et al., Adult neurogenesis promotes synaptic plasticity in the olfactory bulb. Nature neuroscience, 2009. 12(6): p. 728-730. [CrossRef]

- Hack, M.A., et al., Neuronal fate determinants of adult olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Nature neuroscience, 2005. 8(7): p. 865-872. [CrossRef]

- Sanai, N., et al., Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature, 2011. 478(7369): p. 382-386. [CrossRef]

- Khraiche, M.L., et al., Sustained elevation of activity of developing neurons grown on polyimide microelectrode arrays (MEA) in response to ultrasound exposure. Microsystem Technologies, 2017. 23: p. 3671-3683. [CrossRef]

- Taupin, P., BrdU immunohistochemistry for studying adult neurogenesis: paradigms, pitfalls, limitations, and validation. Brain research reviews, 2007. 53(1): p. 198-214. [CrossRef]

- Duque, A. and R. Spector, A balanced evaluation of the evidence for adult neurogenesis in humans: implication for neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain Structure and Function, 2019. 224(7): p. 2281-2295. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al., Increased BrdU incorporation reflecting DNA repair, neuronal de-differentiation or possible neurogenesis in the adult cochlear nucleus following bilateral cochlear lesions in the rat. Experimental brain research, 2011. 210: p. 477-487. [CrossRef]

- Duque, A. and P. Rakic, Different effects of bromodeoxyuridine and [3H] thymidine incorporation into DNA on cell proliferation, position, and fate. Journal of Neuroscience, 2011. 31(42): p. 15205-15217.

- Maga, G. and U. Hubscher, Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a dancer with many partners. Journal of cell science, 2003. 116(15): p. 3051-3060. [CrossRef]

- Ayanlaja, A.A., et al., Distinct features of doublecortin as a marker of neuronal migration and its implications in cancer cell mobility. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience, 2017. 10: p. 199. [CrossRef]

- Dayer, A.G., et al., New GABAergic interneurons in the adult neocortex and striatum are generated from different precursors. The Journal of cell biology, 2005. 168(3): p. 415-427. [CrossRef]

- Zuccato, C. and E. Cattaneo, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2009. 5(6): p. 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Dawbarn, D. and S. Allen, Neurotrophins and neurodegeneration. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology, 2003. 29(3): p. 211-230.

- Fumagalli, F., et al., Neurotrophic factors in neurodegenerative disorders: potential for therapy. CNS drugs, 2008. 22: p. 1005-1019.

- Rossi, C., et al., Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is required for the enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis following environmental enrichment. European Journal of Neuroscience, 2006. 24(7): p. 1850-1856. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.-Y., et al., MANF promotes differentiation and migration of neural progenitor cells with potential neural regenerative effects in stroke. Molecular therapy, 2018. 26(1): p. 238-255. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, D., et al., The non-survival effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on neural cells. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 2017. 10: p. 258. [CrossRef]

- d’Anglemont de Tassigny, X., A. Pascual, and J. López-Barneo, GDNF-based therapies, GDNF-producing interneurons, and trophic support of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway. Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in neuroanatomy, 2015. 9: p. 10.

- Wang, F., et al., GDNF-pretreatment enhances the survival of neural stem cells following transplantation in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience research, 2011. 71(1): p. 92-98. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.M., D.J. Bouchier-Hayes, and J.H. Harmey, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its role in non-endothelial cells: autocrine signalling by VEGF, in Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. 2013, Landes Bioscience. [CrossRef]

- Barth, K., et al., EGFL7 loss correlates with increased VEGF-D expression, upregulating hippocampal adult neurogenesis and improving spatial learning and memory. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2023. 80(2): p. 54.

- Zhang, L., H. Jiang, and Z. Hu, Concentration-dependent effect of nerve growth factor on cell fate determination of neural progenitors. Stem Cells and Development, 2011. 20(10): p. 1723-1731. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., et al., Erk1/2 promotes proliferation and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Neuroscience letters, 2009. 461(3): p. 252-257. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-C., et al., Effect of single growth factor and growth factor combinations on differentiation of neural stem cells. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, 2008. 44(6): p. 375. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M., et al., Combinatorial protein display for the cell-based screening of biomaterials that direct neural stem cell differentiation. Biomaterials, 2007. 28(6): p. 1048-1060. [CrossRef]

- Levenberg, S., et al., Neurotrophin-induced differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on three-dimensional polymeric scaffolds. Tissue engineering, 2005. 11(3-4): p. 506-512. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., et al., ASIC1a is required for neuronal activation via low-intensity ultrasound stimulation in mouse brain. Elife, 2021. 10: p. e61660. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Transcranial ultrasound stimulation directly influences the cortical excitability of the motor cortex in Parkinsonian mice. Movement Disorders, 2020. 35(4): p. 693-698. [CrossRef]

- Mooney, S.J., et al., Focused ultrasound-induced neurogenesis requires an increase in blood-brain barrier permeability. PloS one, 2016. 11(7): p. e0159892. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-T., T.-H. Lan, and F.-Y. Yang, Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound attenuates LPS-induced neuroinflammation and memory impairment by modulation of TLR4/NF-κB signaling and CREB/BDNF expression. Cerebral Cortex, 2019. 29(4): p. 1430-1438. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-C., et al., Differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells using low-intensity ultrasound. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2014. 40(9): p. 2195-2206. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, E.N., The effect of high frequency sound waves on heart muscle and other irritable tissues. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content, 1929. 91(1): p. 284-290. [CrossRef]

- Khraiche, M.L., et al., Ultrasound induced increase in excitability of single neurons. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2008. 2008: p. 4246-9.

- Fry, F., H. Ades, and W. Fry, Production of reversible changes in the central nervous system by ultrasound. Science, 1958. 127(3289): p. 83-84. [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, V., N. Vykhodtseva, and V. Elagin, Spreading depression in the cortex and subcortical structures of the brain of the rat induced by exposure to focused ultrasound. Neirofiziologiia= Neurophysiology, 1986. 18(1): p. 55-61.

- Velling, V. and S. Shklyaruk, Modulation of the functional state of the brain with the aid of focused ultrasonic action. Neuroscience and behavioral physiology, 1988. 18: p. 369-375. [CrossRef]

- Muratore, R., et al. Bioeffective ultrasound at very low doses: Reversible manipulation of neuronal cell morphology and function in vitro. in AIP Conference Proceedings. 2009. American Institute of Physics.

- Tyler, W.J., et al., Remote excitation of neuronal circuits using low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasound. PloS one, 2008. 3(10): p. e3511. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., et al., Noninvasive transcranial stimulation of rat abducens nerve by focused ultrasound. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2012. 38(9): p. 1568-1575. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., et al., Suppression of EEG visual-evoked potentials in rats through neuromodulatory focused ultrasound. Neuroreport, 2015. 26(4): p. 211-215. [CrossRef]

- King, R.L., et al., Effective parameters for ultrasound-induced in vivo neurostimulation. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2013. 39(2): p. 312-331. [CrossRef]

- King, R.L., J.R. Brown, and K.B. Pauly, Localization of ultrasound-induced in vivo neurostimulation in the mouse model. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2014. 40(7): p. 1512-1522. [CrossRef]

- Papp, T., et al., Ultrasound Used for Diagnostic Imaging Facilitates Dendritic Branching of Developing Neurons in the Mouse Cortex. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2022. 16: p. 803356. [CrossRef]

- Hameroff, S., et al., Transcranial ultrasound (TUS) effects on mental states: a pilot study. Brain stimulation, 2013. 6(3): p. 409-415. [CrossRef]

- Kubanek, J., et al., Remote, brain region–specific control of choice behavior with ultrasonic waves. Science advances, 2020. 6(21): p. eaaz4193.

- Yang, P.-F., et al., Neuromodulation of sensory networks in monkey brain by focused ultrasound with MRI guidance and detection. Scientific reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 7993. [CrossRef]

- Legon, W., et al., Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans. Nature neuroscience, 2014. 17(2): p. 322-329. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J., et al., Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates intrinsic and evoked EEG dynamics. Brain stimulation, 2014. 7(6): p. 900-908. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W., et al., Image-guided transcranial focused ultrasound stimulates human primary somatosensory cortex. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 8743. [CrossRef]

- Deffieux, T., et al., Low-intensity focused ultrasound modulates monkey visuomotor behavior. Current Biology, 2013. 23(23): p. 2430-2433. [CrossRef]

- Sanguinetti, J.L., et al., Transcranial focused ultrasound to the right prefrontal cortex improves mood and alters functional connectivity in humans. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 2020. 14: p. 494085. [CrossRef]

- Folloni, D., et al., Manipulation of subcortical and deep cortical activity in the primate brain using transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation. Neuron, 2019. 101(6): p. 1109-1116. e5. [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, L., et al., Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates. Elife, 2019. 8: p. e40541. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.-F., et al., Neuromodulation-based stem cell therapy in brain repair: recent advances and future perspectives. Neuroscience Bulletin, 2021. 37: p. 735-745. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound regulates proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells through notch signaling pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2020. 526(3): p. 793-798. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-Y., et al., Enhancement of neurotrophic factors in astrocyte for neuroprotective effects in brain disorders using low-intensity pulsed ultrasound stimulation. Brain stimulation, 2015. 8(3): p. 465-473. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-L., et al., Protective effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on memory impairment and brain damage in a rat model of vascular dementia. Radiology, 2017. 282(1): p. 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-S., et al., Transcranial ultrasound stimulation promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor and reduces apoptosis in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Brain Stimulation, 2017. 10(6): p. 1032-1041. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., et al., Readout-segmented echo-planar diffusion-weighted MR at 3.0 T for the evaluation the effect of low-intensity transcranial ultrasound on stroke in a rat model. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2020. 67: p. 79-84. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M., et al., Preventive effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasound against experimental cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via apoptosis reduction and brain-derived neurotrophic factor induction. Scientific reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 5568. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T., et al., Low intensity pulsed ultrasound prevents recurrent ischemic stroke in a cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury mouse model via brain-derived neurotrophic factor induction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2019. 20(20): p. 5169. [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.-Y., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances neurotrophic factors and alleviates neuroinflammation in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Cerebral Cortex, 2022. 32(1): p. 176-185. [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, K., et al., Whole-brain low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy markedly improves cognitive dysfunctions in mouse models of dementia-Crucial roles of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Brain Stimulation, 2018. 11(5): p. 959-973. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-E., et al., The effect of ultrasound for increasing neural differentiation in hBM-MSCs and inducing neurogenesis in ischemic stroke model. Life Sciences, 2016. 165: p. 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J., S.W. Lani, and G.M. Hwang, Ultrasonic modulation of neural circuit activity. Current opinion in neurobiology, 2018. 50: p. 222-231. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.E., T.E. Chemaly, and M. Khraiche. Towards A Biomechanical Model for Ultrasound Effect on Neural Excitability. in 2018 IEEE International Multidisciplinary Conference on Engineering Technology (IMCET). 2018.

- Khraiche, M.L., J. Rogul, and J. Muthuswamy, Design and Development of Microscale Thickness Shear Mode (TSM) Resonators for Sensing Neuronal Adhesion. Front Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 518. [CrossRef]

- Khraiche, M. and J. Muthuswamy, Multi-modal biochip for simultaneous, real-time measurement of adhesion and electrical activity of neurons in culture. Lab Chip, 2012. 12(16): p. 2930-41. [CrossRef]

- Legon, W., et al., A retrospective qualitative report of symptoms and safety from transcranial focused ultrasound for neuromodulation in humans. Scientific reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 5573. [CrossRef]

- Krasovitski, B., et al., Intramembrane cavitation as a unifying mechanism for ultrasound-induced bioeffects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011. 108(8): p. 3258-3263. [CrossRef]

- Plaksin, M., S. Shoham, and E. Kimmel, Intramembrane cavitation as a predictive bio-piezoelectric mechanism for ultrasonic brain stimulation. Physical review X, 2014. 4(1): p. 011004. [CrossRef]

- Plaksin, M., E. Kimmel, and S. Shoham, Cell-type-selective effects of intramembrane cavitation as a unifying theoretical framework for ultrasonic neuromodulation. eneuro, 2016. 3(3). [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J., Noninvasive neuromodulation with ultrasound? A continuum mechanics hypothesis. The Neuroscientist, 2011. 17(1): p. 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, S., et al., Sonogenetics is a non-invasive approach to activating neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature communications, 2015. 6(1): p. 8264. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z., et al., Targeted neurostimulation in mouse brains with non-invasive ultrasound. Cell reports, 2020. 32(7). [CrossRef]

- Kubanek, J., et al., Ultrasound modulates ion channel currents. Scientific reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 24170. [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.E. and P.F. Juranka, Nav channel mechanosensitivity: activation and inactivation accelerate reversibly with stretch. Biophysical journal, 2007. 93(3): p. 822-833. [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, K. and C. Montell, TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 2007. 76: p. 387-417.

- Yoo, S., et al., Focused ultrasound excites cortical neurons via mechanosensitive calcium accumulation and ion channel amplification. Nature communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 493. [CrossRef]

- Sukharev, S. and D.P. Corey, Mechanosensitive channels: multiplicity of families and gating paradigms. Science's STKE, 2004. 2004(219): p. re4-re4. [CrossRef]

- Heimburg, T. and A.D. Jackson, On soliton propagation in biomembranes and nerves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2005. 102(28): p. 9790-9795. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.G., Flexoelectricity of model and living membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 2002. 1561(1): p. 1-25.

- Prieto, M.L., et al., Dynamic response of model lipid membranes to ultrasonic radiation force. PLoS One, 2013. 8(10): p. e77115. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J., et al., Capacitive detection of low-enthalpy, higher-order phase transitions in synthetic and natural composition lipid membranes. Langmuir, 2017. 33(38): p. 10016-10026. [CrossRef]

- Badawe, H.M., R.H. El Hassan, and M.L. Khraiche, Modeling ultrasound modulation of neural function in a single cell. Heliyon, 2023. 9(12). [CrossRef]

- Badawe, H.M. and M.L. Khraiche. Modeling of Calcium-dependent Low Intensity Low Frequency Ultrasound Modulation of a Hodgkin–Huxley Neuron. in 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). 2023. IEEE.

- Zhao, L., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth through mechanotransduction-mediated ERK1/2–CREB–Trx-1 signaling. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 2016. 42(12): p. 2914-2925. [CrossRef]

- Tsuang, Y.H., et al., Effects of low intensity pulsed ultrasound on rat Schwann cells metabolism. Artificial organs, 2011. 35(4): p. 373-383. [CrossRef]

- Ning, G.Z., et al., Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulated with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound: better choice of transplantation treatment for spinal cord injury: treatment for SCI by LIPUS-BMSCs transplantation. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 2019. 25(4): p. 496-508.

- Lv, Y., et al., Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on cell viability, proliferation and neural differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells-derived neural crest stem cells. Biotechnology letters, 2013. 35: p. 2201-2212. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-C., H.-J. Wu, and H.-L. Liu, Dual-frequency ultrasound induces neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and growth factor utilization by enhancing stable cavitation. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2019. 10(3): p. 1452-1461. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A., et al., Neural stem cells influenced by ultrasound: Frequency and energy density dependencies. Physics in Medicine, 2017. 4: p. 8-16. [CrossRef]

- El Hassan, R.H., et al., Frequency dependent, reversible focused ultrasound suppression of evoked potentials in the reflex arc in an anesthetized animal. J Peripher Nerv Syst, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes the proliferation of human bone mesenchymal stem cells by activating PI3K/AKt signaling pathways. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 2019. 120(9): p. 15823-15833.

- Ling, L., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound activates ERK 1/2 and PI 3K-Akt signalling pathways and promotes the proliferation of human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell proliferation, 2017. 50(6): p. e12383. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes Schwann cell viability and proliferation via the GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. International journal of biological sciences, 2018. 14(5): p. 497. [CrossRef]

- Al-Maswary, A.A., et al., Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound induces proliferation of human neural stem cells. Clinical and Translational Discovery, 2024. 4(2): p. e259. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H., et al., Ultrasound enhances the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in astrocyte through activation of TrkB-Akt and calcium-CaMK signaling pathways. Cerebral cortex, 2017. 27(6): p. 3152-3160. [CrossRef]

- Adelegan, O.J., et al., Fabrication of 2D Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer (CMUT) Arrays on Insulating Substrates With Through-Wafer Interconnects Using Sacrificial Release Process. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems, 2020. 29(4): p. 553-561. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., et al., Transcranial Ultrasound Stimulation Improves Memory Performance of Parkinsonian Mice. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2024. 32: p. 1284-1291. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., et al., LIPUS-induced neurogenesis: A potential therapeutic strategy for cognitive dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology, 2024. 371: p. 114588. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., et al., Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation improves neurorehabilitation after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Aging and disease, 2021. 12(1): p. 50. [CrossRef]

- Şen, T., O. Tüfekçioğlu, and Y. Koza, Mechanical index. Anatolian journal of cardiology, 2015. 15(4): p. 334.

- Khraiche, M.L., et al., Ultra-High Photosensitivity Silicon Nanophotonics for Retinal Prosthesis: Electrical Characteristics. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2011.

- Tarhini, A., et al., The effect of temperature on the electrical and thermal conductivity of graphene-based polymer composite films. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2022. 139(14): p. 51896. [CrossRef]

- Chou, Z., et al., Bidirectional neural interface: Closed-loop feedback control for hybrid neural systems. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2015. 2015: p. 3949-52.

| Biomarkers | Function |

|---|---|

| Nestin | Supports neural progenitor cells during early development |

| DCX | Indicates ongoing neurogenesis in immature neurons |

| NeuN | Identifies mature neurons (not all types) |

| GFAP | Supports neuron function and health via astrocytes |

| BrdU | Tracks cell proliferation |

| BDNF | Promotes neuron survival, growth, and synapse formation |

| CREB | Regulates neuronal plasticity, learning, and memory |

| PCNA | Supports DNA synthesis and repair in proliferating cells |

| Tuj1 | Identifies early post-mitotic neurons |

| VEGF | Promotes angiogenesis and neuroprotection |

| NGF | Supports neuron survival, growth, and neuroplasticity |

| GLUT1 | Facilitates glucose transport for brain energy |

| Intensity (mW/cm2) | 3000 | [151] | |||||||||||

| 2600 | [114] | ||||||||||||

| 800 | [33] | ||||||||||||

| 528 | [111] | ||||||||||||

| [117] | |||||||||||||

| [86] | |||||||||||||

| [116] | |||||||||||||

| [115] | |||||||||||||

| [113] | |||||||||||||

| [112] | |||||||||||||

| [111] | |||||||||||||

| [32] | |||||||||||||

| 500 | [142] | [87] | |||||||||||

| 496 | [144] | ||||||||||||

| 300 | [140] | ||||||||||||

| 193 | [34] | ||||||||||||

| 120 | [152] | [29] | |||||||||||

| 110 | [149] | ||||||||||||

| 100 | |||||||||||||

| 90 | [118] | ||||||||||||

| 81.12 | [85] | ||||||||||||

| 69.3 | [110] | ||||||||||||

| 60 | [148] | ||||||||||||

| [145] | |||||||||||||

| 50 | [119] | [141] | |||||||||||

| [139] | |||||||||||||

| 36.2 | [27] | ||||||||||||

| 30 | [146] | [153] | |||||||||||

| 27.37 | [147] | ||||||||||||

| 25 | [35] | ||||||||||||

| 15 | [35] | ||||||||||||

| 8.67 | [150] | ||||||||||||

| 5 | [83] | ||||||||||||

| 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.68 | 1.8 | 1.875 | 3.3 | 4.36 | ||

| Frequency (MHz) | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).