Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Impact of Antibiotics on Mealworm Weight

2.2. Evaluation of Homogeneity and Stability of Antibiotic-Containing Feed Samples Using LC-MS/MS Analysis

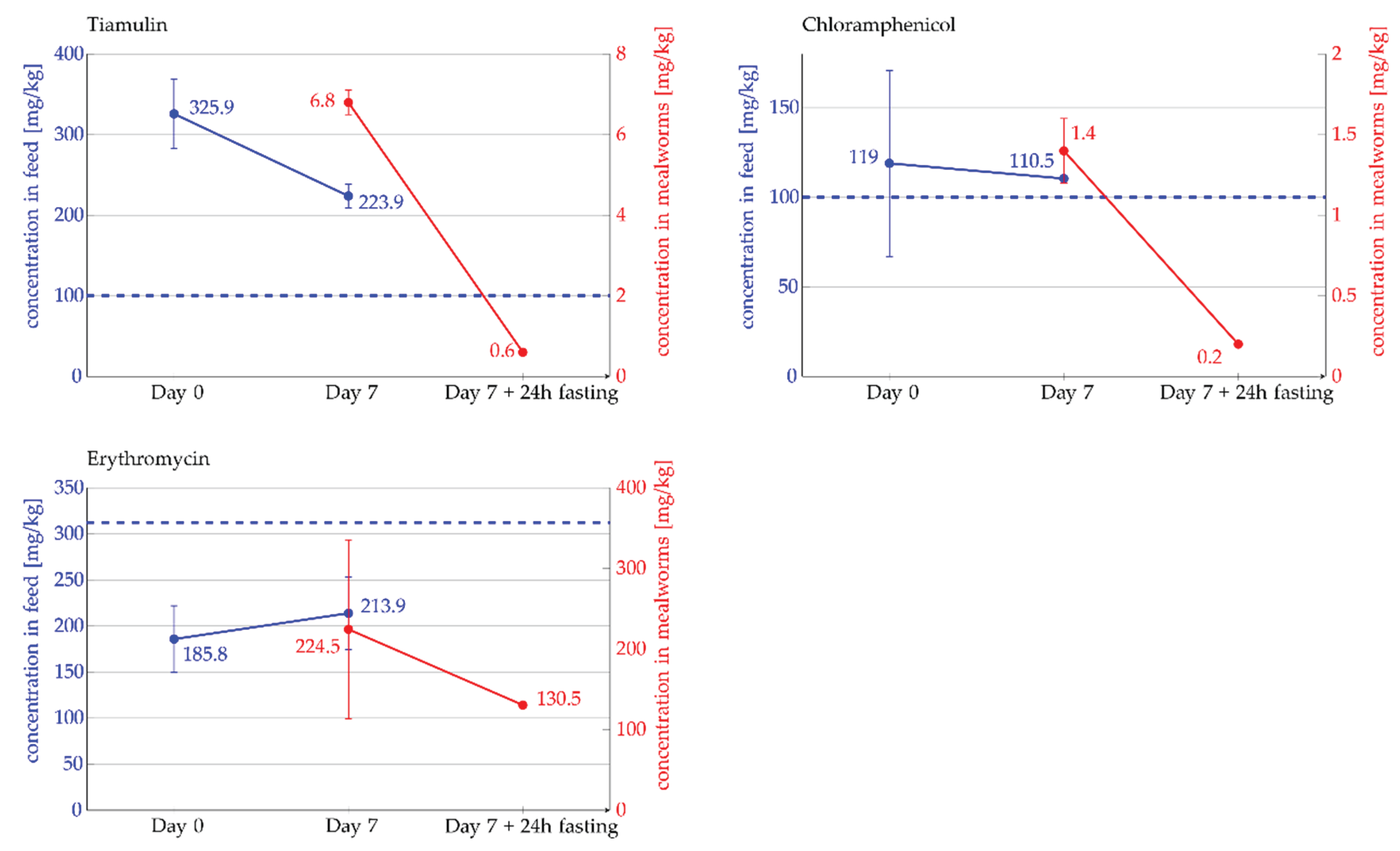

2.3. Detection and Quantification of Antibiotics in Mealworms Using LC-MS/MS Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antibiotics

4.2. Supplementing Feed with Antibiotics

4.3. Feeding Experiment

4.4. Evaluation of Homogeneity and Stability of Antibiotic-Containing Feed Samples Using LC-MS/MS Analysis

4.5. Detection and Quantification of Antibiotics in Mealworms Using LC-MS/MS Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| SPE | Solid Phase Extraction |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| MRL | Maximum Residue Limit |

| VDLUFA | Association of German Agricultural Analytic and Research Institutes (Verband deutscher landwirtschaftlicher Untersuchungs- und Forschungsanstalten e.V.) |

References

- Angerer, M.; Dubuni, S.; Ellrott, T.; Gebhard, M.; Gebhardt, B.; Hacker, A.; Hirschfelder, G.; Gabriele, K.; Krüger, J.; Kussmann, M.; et al. Wie is(s)t Deutschland 2030?, Frankfurt am Main, 2015.

- Schiel, L.; Wind, C.; Braun, P.G.; Koethe, M. Legal framework for the marketing of food insects in the European Union. Ernahrungs Umschau 2020, 67, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordiean, A.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Stolarski, M.J.; Peni, D. Growth Potential of Yellow Mealworm Reared on Industrial Residues. Agriculture 2020, 10, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Harahap, I.A.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Saikia, T.; Wu, Y.S.; Fernando, I.; Perestrelo, R.; Câmara, J.S. Bioconversion of organic waste by insects – A comprehensive review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2024, 187, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; van Itterbeeck, J.; Heetkamp, M.J.W.; van den Brand, H.; van Loon, J.J.A.; van Huis, A. An exploration on greenhouse gas and ammonia production by insect species suitable for animal or human consumption. PLoS One 2010, 5, e14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; van Broekhoven, S.; van Huis, A.; van Loon, J.J.A. Correction: Feed Conversion, Survival and Development, and Composition of Four Insect Species on Diets Composed of Food By-Products. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0222043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Francis, F.; Haubruge, E.; Le Gall, P.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Miranda, C.D.; Jordan, H.R.; Picard, C.J.; Pino, M.; Ramos-Elordy, J.; et al. A worldwide overview of the status and prospects of edible insect production. entomologia 2024, 44, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A. Edible insects: Challenges and prospects. Entomological Research 2022, 52, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A. Potential of insects as food and feed in assuring food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Tettey, E.; Yunusa, B.M.; Ngah, N.; Debrah, S.K.; Yang, X.; Fernando, I.; Povetkin, S.N.; Shah, M.A. Legal situation and consumer acceptance of insects being eaten as human food in different nations across the world-A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2023, 22, 4786–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippel, F.-W. Insekten: Das Fleisch der Zukunft? Available online: https://www.doccheck.com/de/detail/articles/42719-insekten-das-fleisch-der-zukunft (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Favaro, R.; Lupi, D.; Jucker, C.; Cappellozza, S.; Faccoli, M. An artificial diet for rearing three exotic longhorn beetles invasive to Europe. Bulletin of Insectology 2017, 70, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellozza, L.; Cappellozza, S.; Saviane, A.; Sbrenna, G. Artificial diet rearing system for the silkworm Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae): Effect of vitamin C deprivation on larval growth and cocoon production. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2005, 40, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzoli, F.; Tata, A.; Massaro, A.; Bragolusi, M.; Passabì, E.; Cappellozza, S.; Saviane, A.; Tassoni, L.; Piro, R.; Belluco, S. Microbiological and chemical safety of Bombyx mori farmed in north-eastern Italy as a novel food source. JIFF 2023, 9, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed. EFSA Journal 2015, 13, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek-van den Hil, E.F.; van de Schans, M.; Bor, G.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J. Effects of veterinary drugs on rearing and safety of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Xu, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Jones, D.L.; Zou, J. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils: A systematic analysis. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, R.; Scott, A.; Tien, Y.-C.; Murray, R.; Sabourin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Topp, E. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5701–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, H.C.S.; Ashworth, A.J.; Arsi, K.; Rojas, M.G.; Morales-Ramos, J.A.; Donoghue, A.; Robinson, K. Insect frass composition and potential use as an organic fertilizer in circular economies. Journal of Economic Entomology 2024, 117, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asendorf, T.; Wind, C.; Rullmann, A.; Vilcinskas, A. Comparison of DNA-based methods for the detection of meat feeding in Alphitobius diaperinus larvae. JIFF 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.L.; Caffrey, N.P.; Nóbrega, D.B.; Cork, S.C.; Ronksley, P.E.; Barkema, H.W.; Polachek, A.J.; Ganshorn, H.; Sharma, N.; Kellner, J.D.; et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e316–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grispoldi, L.; Karama, M.; El-Ashram, S.; Saraiva, C.M.; García-Díez, J.; Chalias, A.; Barbera, S.; Cenci-Goga, B.T. Hygienic Characteristics and Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Crickets (Acheta domesticus) Breed for Flour Production. Microbiology Research 2021, 12, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Pasquini, M.; Aquilanti, L.; Garofalo, C.; Taccari, M.; Cardinali, F.; Riolo, P.; Clementi, F. Getting insight into the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in specimens of marketed edible insects. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 227, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimani, A.; Milanović, V.; Cardinali, F.; Garofalo, C.; Clementi, F.; Ruschioni, S.; Riolo, P.; Isidoro, N.; Loreto, N.; Galarini, R.; et al. Distribution of Transferable Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Laboratory-Reared Edible Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor L.). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimani, A.; Garofalo, C.; Milanović, V.; Taccari, M.; Cardinali, F.; Aquilanti, L.; Pasquini, M.; Mozzon, M.; Raffaelli, N.; Ruschioni, S.; et al. Insight into the proximate composition and microbial diversity of edible insects marketed in the European Union. Eur Food Res Technol 2017, 243, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, E.; Cao, S.; Berg, O.G.; Ilbäck, C.; Sandegren, L.; Hughes, D.; Andersson, D.I. Selection of resistant bacteria at very low antibiotic concentrations. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schemmel, D.; Rukavina, M. BVL-Report 19.4: Berichte zur Lebensmittelsicherheit 2023. 2025. Available online: www.bvl.bund.de (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Hegmanns, M.; Kopf, G.; Schiel, L.; Wind, C.; Krüger, S.; Pietsch, K.; Müller, M.; Schill, S. Ergebnisse der Untersuchungen aus dem Insekten Internetprojekt, Freiburg, 2021. Available online: https://www.ua-bw.de/pub/beitrag.asp?subid=3&Thema_ID=2&ID=3406&Pdf=No&lang=DE (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Herrman, T.; Behnke, K.C.; Loughin, T. Mixing and clean-out properties of sulfamethazine and carbadox in swine feed (1995). Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station Research Reports 1995, 10, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimani, A.; Cardinali, F.; Aquilanti, L.; Garofalo, C.; Roncolini, A.; Milanović, V.; Pasquini, M.; Tavoletti, S.; Clementi, F. Occurrence of transferable antibiotic resistances in commercialized ready-to-eat mealworms (Tenebrio molitor L.). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 263, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Y.I.; Lahaye, L.; Gong, M.M.; Peng, J.; Gong, J.; Liu, S.; Gay, C.G.; Yang, C. Innovative drugs, chemicals, and enzymes within the animal production chain. Vet. Res. 2018, 49, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, E.; Panizzi, A.R.; Cattelan, A.J. Potential Use of Antibiotic to Improve Performance of Laboratory-Reared Nezara viridula (L.) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Neotropical Entomology 2006, 35, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickel, F.; Freitak, D.; Mappes, J. Long-Term Prophylactic Antibiotic Treatment: Effects on Survival, Immunocompetence and Reproduction Success of Parasemia plantaginis (Lepidoptera: Erebidae). J. Insect Sci. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T. Fumagillin Affects Nosema apis and Honey Bees (Hymonopterai Apidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 1994, 87, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellozza, S.; Saviane, A.; Tettamanti, G.; Squadrin, M.; Vendramin, E.; Paolucci, P.; Franzetti, E.; Squartini, A. Identification of Enterococcus mundtii as a pathogenic agent involved in the “flacherie” disease in Bombyx mori L. larvae reared on artificial diet. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011, 106, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.M. Modification of feeding ‘preference’ in the flea-beetle, Halitica lythri (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). Entomologia Exp Applicata 1977, 21, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, J.K.; Kainulainen, E.; Hänninen, O. Palatability of herbicide-treated maize to the Indian stick insect (Carausius morosus). Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 1991, 36, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, H.R.; Collier, C.T.; Anderson, D.B. Antibiotics as growth promotants: mode of action. Anim. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niewold, T.A. The nonantibiotic anti-inflammatory effect of antimicrobial growth promoters, the real mode of action? A hypothesis. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilenberg, J.; Vlak, J.M.; Nielsen-LeRoux, C.; Cappellozza, S.; Jensen, A.B. Diseases in insects produced for food and feed. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2015, 1, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel-Vergara, G.; Jensen, A.B.; Lecocq, A.; Eilenberg, J. Diseases in edible insect rearing systems. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2021, 7, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałęcki, R.; Sokół, R. A parasitological evaluation of edible insects and their role in the transmission of parasitic diseases to humans and animals. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunder, H.C.; Wolkers-Rooijackers, J.; Korpela, J.M.; Nout, M. Microbiological aspects of processing and storage of edible insects. Food Control 2012, 26, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Milanović, V.; Cardinali, F.; Aquilanti, L.; Clementi, F.; Osimani, A. Current knowledge on the microbiota of edible insects intended for human consumption: A state-of-the-art review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambros, L.; Montoya, L.; Kreil, V.; Waxman, S.; Albarellos, G.; Rebuelto, M.; Hallu, R.; San Andres, M.I. Pharmacokinetics of erythromycin in nonlactating and lactating goats after intravenous and intramuscular administration. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 30, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Switała, M.; Hrynyk, R.; Smutkiewicz, A.; Jaworski, K.; Pawlowski, P.; Okoniewski, P.; Grabowski, T.; Debowy, J. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol, thiamphenicol, and chloramphenicol in turkeys. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 30, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazab, S.T.; Elshater, N.S.; Hashem, Y.H.; Park, S.-C.; Hsu, W.H. Tissue Residues and Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Tiamulin Against Mycoplasma anatis in Ducks. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 603950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laber, G.; Schütze, E. Blood level studies in chickens, turkey poults and swine with tiamulin, a new antibiotic. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1977, 30, 1119–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartini, I.; Vercelli, C.; Lebkowska-Wieruszewska, B.; Lisowski, A.; Fadel, C.; Poapolathep, A.; Dessì, F.; Giorgi, M. Pharmacokinetics and antibacterial activity of tiamulin after single and multiple oral administrations in geese. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucă, V.C.; Rusănescu, C.O.; Safta, V.V. Analysis of Transfer of Tiamulin to Animal Tissue after Oral Administration: An Important Factor for Ensuring Food Safety and Environmental Protection. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, E.; Wiggins, D.; Fielding, B.; Gould, A.P. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature 2007, 445, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrese, E.L.; Soulages, J.L. Insect fat body: energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Z.; Subramanyam, B.; Zurek, L.; Herrman, T. Diversity and antibiotic resistance of enterococci associated with stored-product insects collected from feed mills. Journal of Stored Products Research 2008, 44, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N.; Anjali, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Shreyata, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Sabu, B.; Jamwal, R.; Devi, P.P.; Yadav, K.; Raina, H.S.; Rajagopal, R. Understanding the role of insects in the acquisition and transmission of antibiotic resistance. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Roncolini, A.; Garofalo, C.; Aquilanti, L.; Pasquini, M.; Tavoletti, S.; Vignaroli, C.; Canonico, L.; Ciani, M.; et al. Investigation of the Dominant Microbiota in Ready-to-Eat Grasshoppers and Mealworms and Quantification of Carbapenem Resistance Genes by qPCR. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, Y.; Glaeser, S.P.; Mvie, J.; Bartz, J.-O.; Müller, A.; Gutzeit, H.O.; Vilcinskas, A.; Kämpfer, P. The gut and feed residue microbiota changing during the rearing of Hermetia illucens larvae. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1323–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Richter, A.; Potschka, H. Pharmakotherapie bei Haus- und Nutztieren; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, 2014; ISBN 9783830412502. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewska, M.; Błażejewska, A.; Czapko, A.; Popowska, M. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Animal Manure - Consequences of Its Application in Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 610656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzam, K.; Nessel, T.; Quick, J. Erythromycin. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532249/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Alippi, A.M.; Albo, G.N.; Leniz, D.; Rivera, I.; Zanelli, M.L.; Roca, A.E. Comparative study of tylosin, erythromycin and oxytetracycline to control American foulbrood of honey bees. Journal of Apicultural Research 1999, 38, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methode 14.1.5, Bestimmung ausgewählter Antibiotika in Futtermitteln mittels LC-MSMS.; VERBAND DEUTSCHER LANDWIRTSCHAFTLICHER UNTERSUCHUNGS- UND FORSCHUNGSANSTALTEN, Ed.; VDLUFA-Verlag: Darmstadt, 2018. Darmstadt.

| Tiamulin | Chloramphenicol | Erythromycin | Erythromycin/1000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| average X̅ [mg/kg] | 325.9 | 119 | 185.8 | 0.3 |

| SD [mg/kg] | 43.4 | 52 | 36.2 | 0.03 |

| coefficient of variation (CV) [%] | 13.3 | 43.7 | 19.5 | 11.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).