Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

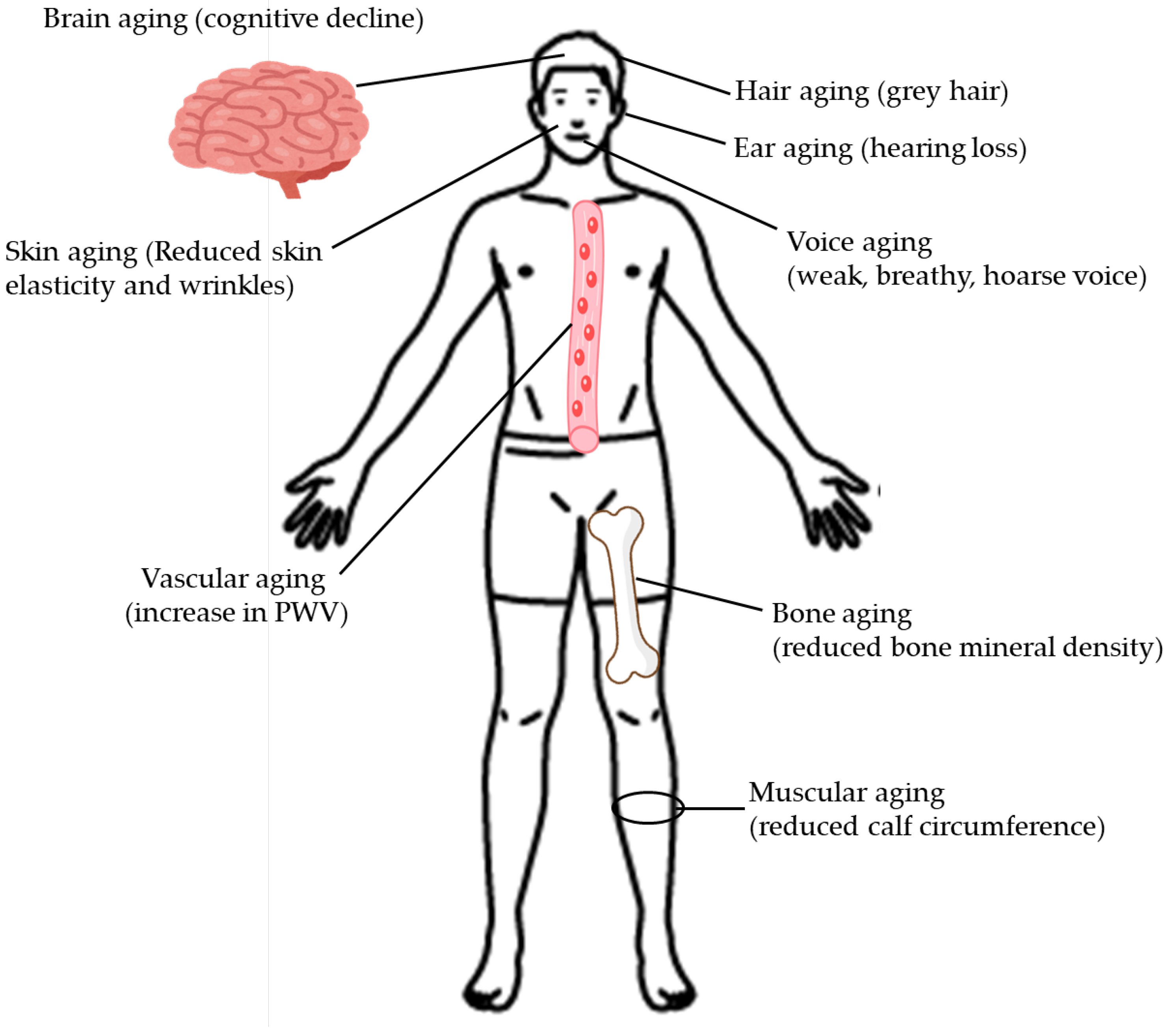

2. The Influence of Type 2 Diabetes on the Clinical Manifestations of Aging

2.1. Hair Aging

2.2. Skin Aging

2.3. Voice Aging

2.4. Ear Aging

2.5. Brain Aging

2.6. Bone Aging

2.7. Vascular Aging

2.8. Muscular Aging

2.9. Effect of Type 2 Diabetes on the Clinical Manifestations of Aging

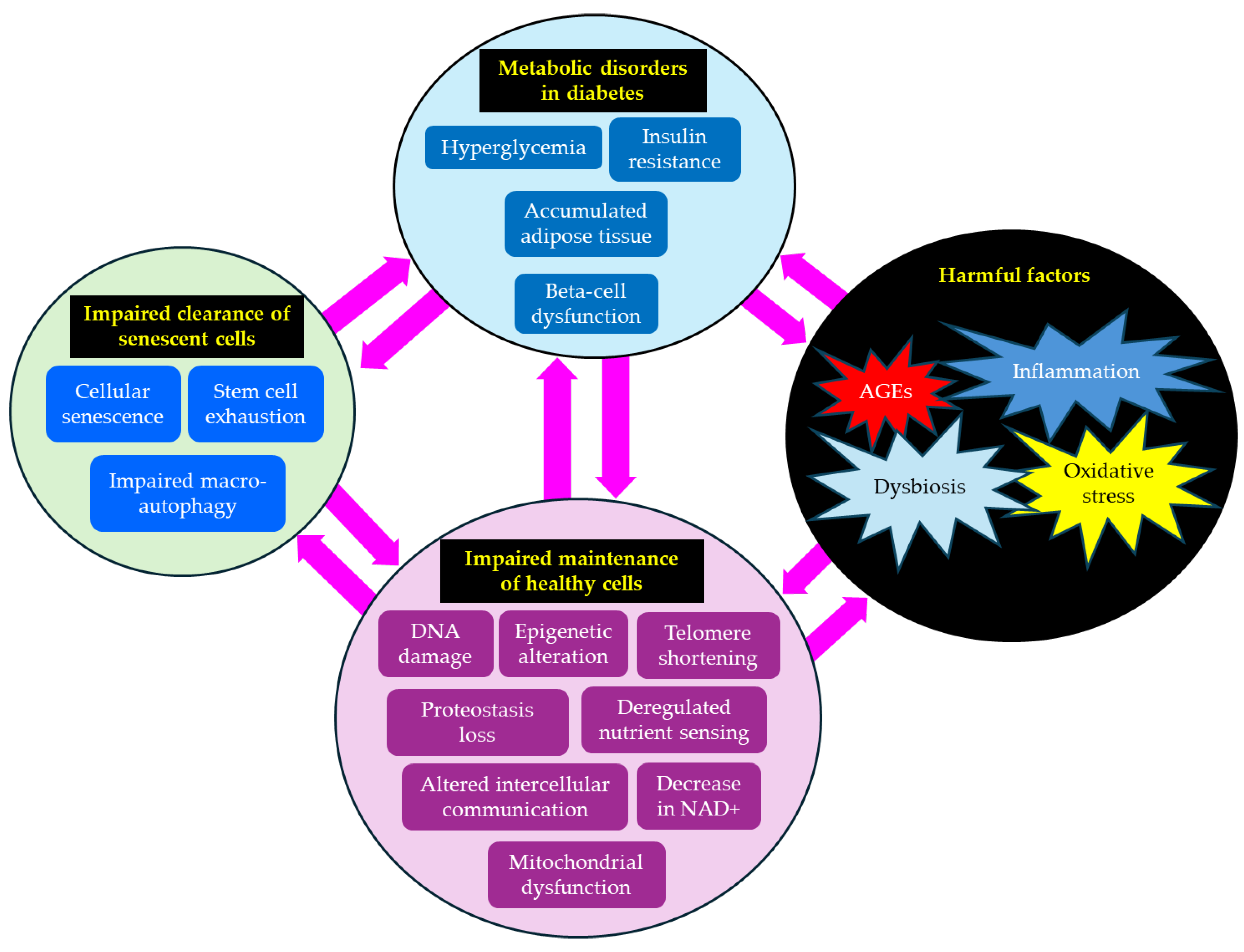

3. The Hallmarks of Aging and Their Association with Type 2 Diabetes

3.1. Oxidative Stress

3.2. Inflammation

3.3. AGEs

3.4. Dysbiosis

3.5. DNA Damage

3.6. Telomere Shortening

3.7. Epigenetic Alterations

3.8. Loss of Protein Balance

3.9. Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

3.10. Altered Intercellular Communication

3.11. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

3.12. A Decline in Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+)

3.13. Cellular Senescence

3.14. Stem Cell Exhaustion

3.15. Impaired Macro-Autophagy

3.16. The Association Between Hallmarks of Aging and Type 2 Diabetes

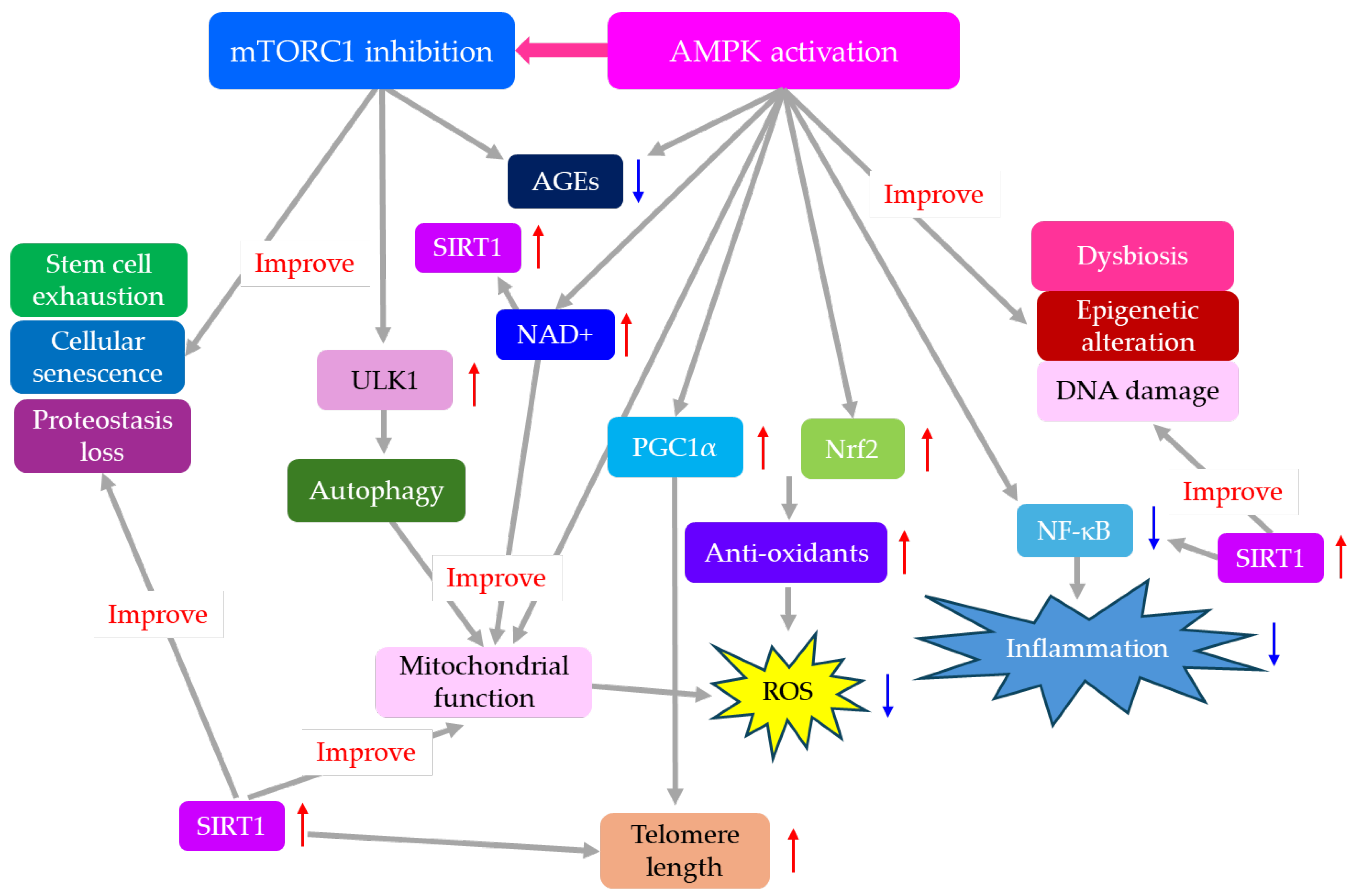

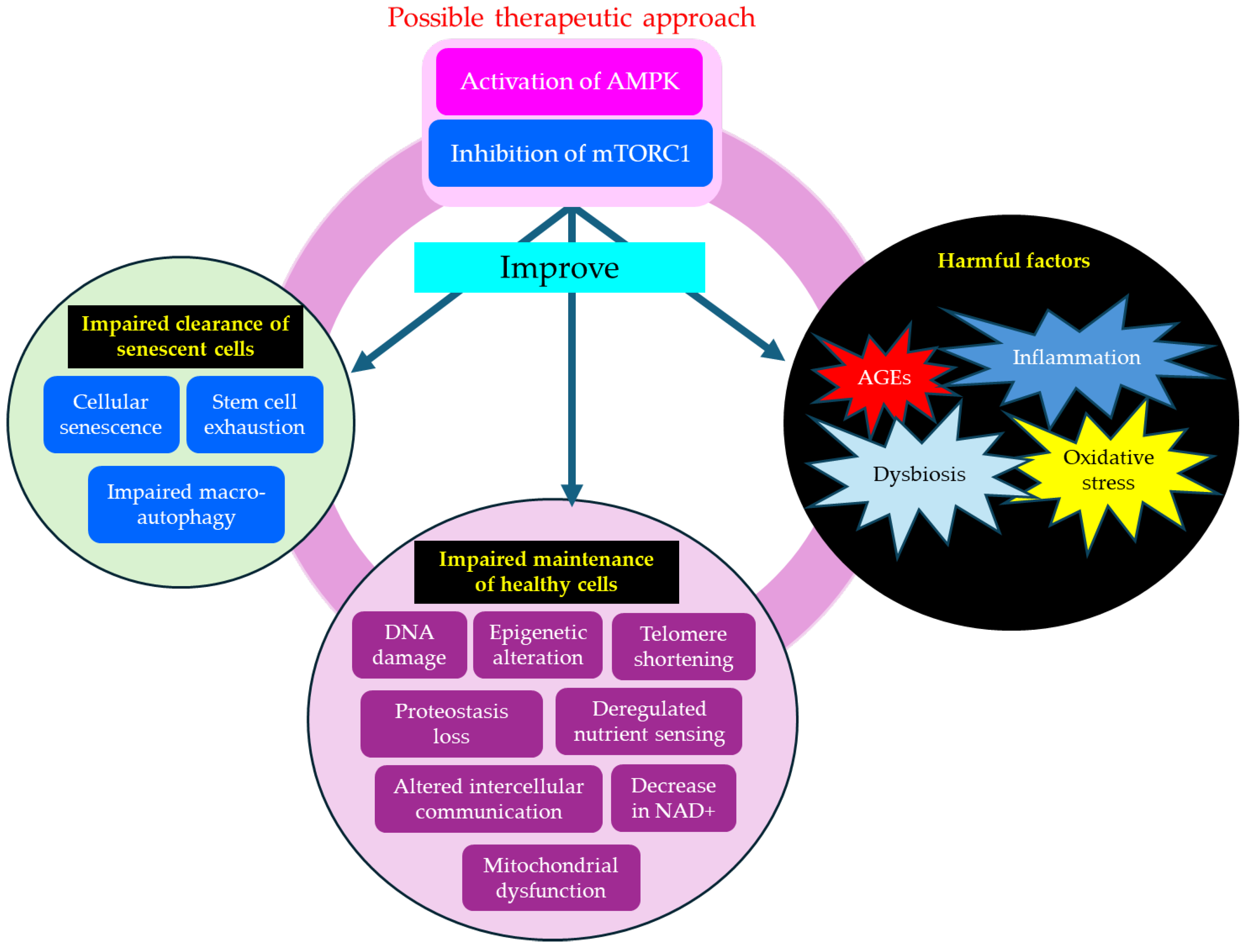

4. The Significance of AMPK Activation and mTORC1 Inhibition for Anti-Aging Medicine

5. Effects of AMPK Activation and mTORC1 Inhibition on Diabetic Complications

5.1. Diabetic Neuropathy

5.2. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

5.3. Diabetic Nephropathy

5.4. CVD

5.5. AD

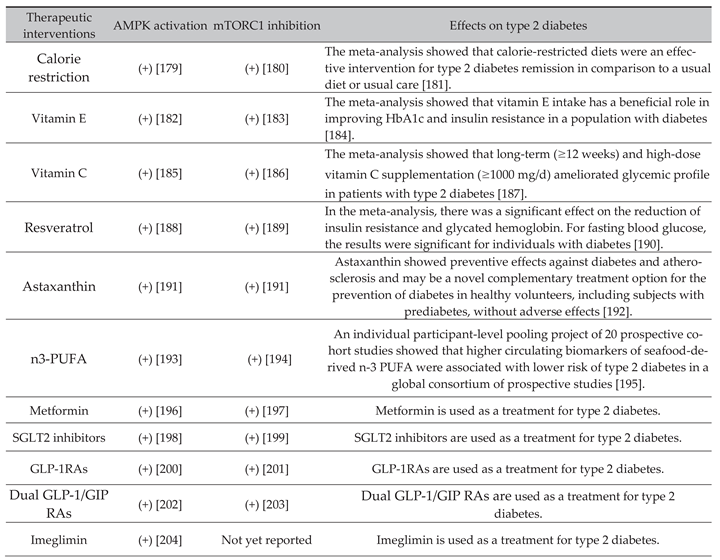

6. Effects of Nutritional Interventions and Drugs That Improve Aging Hallmarks by AMPK Activation and mTORC1 Inhibition on Type 2 Diabetes

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AGEs | advanced glycation end products |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| CTRP3 | C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-3 |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CVD | cardiovascular diseases |

| DR | diabetic retinopathy |

| DKD | Diabetic Kidney disease |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| GIP | glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GLP-1RAs | glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| hs-CRP | high-sensitive C-reactive protein |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| MD | mean difference |

| NSN | nutrient-sensing network |

| mTORC1 | mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 |

| PGC1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- γ Coactivator 1α |

| PWV | pulse wave velocity |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RAGE | Receptors for advanced glycation end products |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SGLT2 | sodium glucose co-transporter-2 |

| SIRT | sirtuin |

| TBF | Tang Bi formula |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

References

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Bao, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Molecular mechanisms of aging and anti-aging strategies. Cell. Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Umetani, M.; Nishio, M.; Shigetomi, H.; Imanaka, S.; Hashimoto, H. Molecular Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence in Age-Related Endometrial Dysfunction. Cells. 2025, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.L.; Rowe, J.H.; Garcia-de-Alba, C.; Kim, C.F.; Sharpe, A.H.; Haigis, M.C. The aging lung: Physiology, disease, and immunity. Cell. 2021, 184, 1990–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tu, C.; Chen, X.; He, R. Advanced Glycation End Products in Disease Development and Potential Interventions. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, E.N.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M.E. The gut microbiota and unhealthy aging: disentangling cause from Consequence. Cell. Host. Microbe. 2020, 28, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsegiani, A.S.; Shah, Z.A. The influence of gut microbiota alteration on age-related neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Neural. Regeneration. Res. 2022, 17, 2407–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Simon, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. DNA damage and repair in age-related inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, E.R.; Bjedov, I. Balancing DNA repair to prevent ageing and cancer. Exp. Cell. Res. 2021, 405, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Hu, X. Causality of Aging Hallmarks. Aging. Dis. Online ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wei, P.; Yi, L.; Lin, S. Epigenetic Insights Into Aging: Emerging Roles of Natural Products in Therapeutic Interventions. Phytother Res. Online ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltsas, A. Multi-Omics Perspectives on Testicular Aging: Unraveling Germline Dysregulation, Niche Dysfunction, and Epigenetic Remodeling. Cells. 2025, 14, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holwerda, A.M.; Paulussen, K.J.M.; Overkamp, M.; Goessens, J.P.B.; Kramer, I.F.; Wodzig, W.K.W.H.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Dose-Dependent Increases in Whole-Body Net Protein Balance and Dietary Protein-Derived Amino Acid Incorporation into Myofibrillar Protein During Recovery from Resistance Exercise in Older Men. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slack, C.; Alic, N.; Foley, A.; Cabecinha, M.; Hoddinott, M.P.; Partridge, L. The Ras-Erk-ETS-Signaling Pathway Is a Drug Target for Longevity. Cell. 2015, 162, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.A.; Westerhof, T.M.; Sabin, K.; Merajver, S.D.; Aguilar, C.A. Engineered Tools to Study Intercellular Communication. Adv. Sci (Weinh). 2020, 8, 2002825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafián-Labora, J.A.; O'Loghlen, A. Classical and Nonclassical Intercellular Communication in Senescence and Ageing. Trends. Cell. Biol. 2020, 30, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Li, X.; Tian, Y. Mitochondrial-to-nuclear communication in aging: an epigenetic perspective. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Deng, H.; Ma, R.; Liao, J.Y.; Liang, H.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Cai, J.; et al. Targeting Mitochondria-Located circRNA SCAR Alleviates NASH via Reducing mROS Output. Cell. 2020, 183, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Miura, M.; Williams, E.; Jaksch, F.; Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T.; Guarente, L. NAD+ supplementation rejuvenates aged gut adult stem cells. Aging. Cell. 2019, 18, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Zhang, L.; Gao, W.; Huang, C.; Huber, P.E.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Shen, G.; Zou, B. NAD+ metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qian, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Xiao, N.; Liang, G.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. Mechanisms of endothelial senescence and vascular aging. Biogerontology. 2025, 26, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamakis, G.; Brüne, D.; Ravichandran, S.; Bolz, J.; Fan, W.; Ziebell, F.; Stiehl, T.; Catalá-Martinez, F.; Kupke, J.; Zhao, S.; et al. Quiescence Modulates Stem Cell Maintenance and Regenerative Capacity in the Aging Brain. Cell. 2019, 176, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, A.; Tripodi, N.; Feehan, J. Running on empty: Exploring stem cell exhaustion in geriatric musculoskeletal disease. Maturitas. 2024, 188, 108066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Tasset, I.; Arias, E.; Pampliega, O.; Wong, E.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Cuervo, A.M. Autophagy and the hallmarks of aging. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, L.D.; Narita, M. Autophagy at the intersection of aging, senescence, and cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 3259–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, P.; Caldarelli, M.; Miccoli, E.; Guazzarotti, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gambassi, G.; Cianci, R. Sex Differences in Immune Responses to Infectious Diseases: The Role of Genetics, Hormones, and Aging. Diseases. 2025, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matina, S.S.; Cohen, E.; Mokwena, K.; Mendenhall, E. Menopause and aging in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Climacteric. 2025, 28, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Age-related changes in AMPK activation: Role for AMPK phosphatases and inhibitory phosphorylation by upstream signaling pathways. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2016, 28, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Tekinalp, S.G.; Tuzcu, B.; Cam, F.; Sevik, M.O.; Tatar, E.; Deepak Kalaskarf, D.; Emin Cam, M.E. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase activators on energy balance and cellular metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obesity. Medicine. 2025, 53, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannick, J.B.; Lamming, D.W. Targeting the biology of aging with mTOR inhibitors. Nat. Aging. 2023, 3, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Tana, J. Type 2 diabetes - unmet need, unresolved pathogenesis, mTORC1-centric paradigm. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Miao, Y.; Hu, Z. Research progress on the regulation of grey hair production by disruption of melanocyte stem cell homeostasis. Chin. J. Plast. Surg. 2017, 33, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Han, X. Lipidomics: Techniques, applications, and outcomes related to biomedical sciences. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Li, S.; He, C. Lipidomics Combined with Network Pharmacology to Explore Differences in the Mechanisms of Grey Hair Development Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Normal Populations (Female). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, V.R.; Melo, M.O.; Maia Campos, P.M.B.G. Evaluation of Morphological and Structural Skin Alterations on Diabetic Subjects by Biophysical and Imaging Techniques. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.; Bogdanski, E.; Mattei, A.; Michel, J.; Giovanni, A. Presbyphonia: A Scoping Review for a Comprehensive Assessment of Aging Voice. J. Voice. 2024, S0892-1997, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Azevedo, S.; Sousa, F.; Machado, A.S.; Santos, P.C.; Freitas, S.V.; Almeida, E.; Sousa, C.; da Silva, Á.M. Presbylarynx: Is It a Sign of the Health Status of the Elderly? J. Voice. 2023, 37, e1–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samocha-Bonet, D.; Wu, B.; Ryugo, D.K. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss: A review. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, B.; McMahon, L.P.; Sultan, S.F.; Lithen, A.; Wexler, D.J.; Dickerson, B.; Ratai, E.M.; Mujica-Parodi, L.R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus accelerates brain aging and cognitive decline: Complementary findings from UK Biobank and meta-analyses. Elife. 2022, 11, e73138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, H.; Chen, H.; Ma, W.; Li, Y. Type 2 diabetes and bone mineral density: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024, 103, e40468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Asmar, R.; Gautier, I.; Laloux, B.; Guize, L.; Ducimetiere, P.; Benetos, A. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001, 37, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, C.; Aznaouridis, K.; Stefanadis, C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F.; Hwang, S.J.; Vasan, R.S.; Larson, M.G.; Pencina, M.J.; Hamburg, N.M.; Vita, J.A.; Levy, D.; Benjamin, E.J. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010, 121, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Lee, J.M.; Seo, J.B.; Chung, W.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Zo, J.H.; Kim, M.A. The effects of metabolic syndrome and its components on arterial stiffness in relation to gender. J. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masding, M.G.; Stears, A.J.; Burdge, G.C.; Wootton, S.A.; Sandeman, D.D. Premenopausal advantages in postprandial lipid metabolism are lost in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. Care. 2003, 26, 3243–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonna, R.; Balistreri, C.R.; De Rosa, S.; Muscoli, S.; Selvaggio, S.; Selvaggio, G.; Ferdinandy, P.; De Caterina, R. Impact of sex differences and diabetes on coronary atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Cockcroft, J.; Van Bortel, L.; Boutouyrie, P.; Giannattasio, C.; Hayoz, D.; Pannier, B.; Vlachopoulos, C.; Wilkinson, I.; Struijker-Boudier, H.; et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur. Heart. J. 2006, 27, 2588–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.R.; Wilkinson, I.B.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Avolio, A.P.; Chirinos, J.A.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Heffernan, K.S.; Lakatta, E.G.; McEniery, C.M.; Mitchell, G.F.; et al. Recommendations for improving and standardizing vascular research on arterial stiffness: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2015, 66, 698–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapei, Y.; Xiaoyan, R.; Sha, Z.; Li, P.; Xiao, M.; Shuangfeng, C.; Lexin, W.; Lianqun, C. Clinical Significance of Arterial Stiffness and Thickness Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Up-To-Date Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 21, 2467–2475. [Google Scholar]

- Szablewski, L. Changes in Cells Associated with Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kaji, A.; Sakai, R.; Okamura, T.; Kitagawa, N.; Okada, H.; Nakanishi, N.; Majima, S.; Senmaru, T.; et al. Sarcopenia Is Associated With a Risk of Mortality in People With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 783363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laohajaroensombat, O.; Limpaarayakul, T.; Sathavarodom, N.; Boonyavarakul, A.; Samakkarnthai, P. A comparative analysis of sarcopenia screening methods in Thai people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in an outpatient setting. BMC. Geriatr. 2025, 25, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iakovou, E.; Kourti, M.A. Comprehensive Overview of the Complex Role of Oxidative Stress in Aging, The Contributing Environmental Stressors and Emerging Antioxidant Therapeutic Interventions. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2022, 14, 827900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. J. Signal. Transduct. 2012, 2012, 646354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, J.; Aran, J.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: Drivers of Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, S.; Schurman, S.H.; Harboe, C.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Bohr, V.A. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage and association with cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis. 2009, 30, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erusalimsky, JD. Oxidative stress, telomeres and cellular senescence: What non-drug interventions might break the link? Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 150, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesupatham, A.; Saraswathy, R. Role of oxidative stress in prediabetes development. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 43, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawi, J.; Misakyan, Y.; Affa, S.; Kades, S.; Narasimhan, A.; Hajjar, F.; Besser, M.; Tumanyan, K.; Venketaraman, V. Oxidative Stress, Glutathione Insufficiency, and Inflammatory Pathways in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Biomedicines. 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klisic, A.; Karakasis, P.; Patoulias, D.; Khalaji, A.; Ninić, A. Are oxidative stress biomarkers reliable part of multimarker panel in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metab. Syndrome. Related. Disord. 2024, 22, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, D. Litchi pericarp extract treats type 2 diabetes mellitus by regulating oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and energy metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel Switzerland). 2024, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Schurman, S.H.; Bektas, A.; Kaileh, M.; Roy, R.; Wilson, D.M. 3rd.; Sen, R.; Ferrucci, L. Aging and Inflammation. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, V.; La Grotta, R.; Carreras, F.; Giuliani, A.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Olivieri, F.; Berra, C.C.; Ceriello, A.; Prattichizzo, F. Inflammatory Trajectory of Type 2 Diabetes: Novel Opportunities for Early and Late Treatment. Cells. 2024, 13, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhans, M.S.; Hagman, D.K.; Kuzma, J.N.; Schmidt, K.A.; Kratz, M. Contribution of Adipose Tissue Inflammation to the Development of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J.; Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 105, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, A.; Shahwan, M.; Husain, F.M.; Khan, M.S. Characterization of methylglyoxal induced advanced glycation end products and aggregates of human transferrin: Biophysical and microscopic insight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. Hyperglycemia-induced accumulation of advanced glycosylation end products in fibroblast-like synoviocytes promotes knee osteoarthritis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, J.; Bains, Y.; Guha, S.; Kahn, A.; Hall, D.; Bose, N.; Gugliucci, A.; Kapahi, P. The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in Aging and Metabolic Diseases: Bridging Association and Causality. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaobelina, K.; Cougnard-Gregoire, A.; Delcourt, C.; Gin, H.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Rigalleau, V. Autofluorescence of skin advanced glycation end products: marker of metabolic memory in elderly population. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Petroianu, G.; Adem, A. Advanced glycation end products and diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and perspectives. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowotny, K.; Jung, T.; Höhn, A.; Weber, D.; Grune, T. Advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomolecules. 2015, 5, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Jeong, M.S.; Jang, S.B. Molecular characteristics of RAGE and advances in small-molecule inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengstie, M.A.; Chekol Abebe, E.; Behaile Teklemariam, A.; Tilahun Mulu, A.; Agidew, M.M.; Teshome Azezew, M.; Zewde, E.A.; Agegnehu Teshome, A. Endogenous advanced glycation end products in the pathogenesis of chronic diabetic complications. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1002710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanimozhi, N.V.; Sukumar, M. Aging through the lens of the gut microbiome: Challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics Plus 2 2025, 100142. [Google Scholar]

- Hamjane, N.; Mechita, M.B.; Nourouti, N.G.; Barakat, A. Gut microbiota dysbiosis-associated obesity and its involvement in cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. A systematic review. Microvasc. Res. 2024, 151, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Its Impact on Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Strategies. Metabolites. 2025, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, E.; Sherzai, A.; Adeghate, J.; Sherzai, D. Gut dysbiosis, insulin resistance and Alzheimer's disease: review of a novel approach to neurodegeneration. Front. Biosci (Schol Ed). 2021, 13, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, U.; Li, Q.; Rydén, M.; Spalding, K.L. Cellular senescence and its role in white adipose tissue. Int. J. Obes (Lond). 2021, 45, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, B.; Schwingshackl, L.; Wagner, K.H. Chromosomal damage measured by the cytokinesis block micronucleus cytome assay in diabetes and obesity - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2020, 786, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, D.; LaBella, K.A.; DePinho, R.A. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2021, 184, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorelli, S.; Passos, J.F. Telomeres and cell senescence-size matters not. EBioMedicine. 2017, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shammas, M.A. Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2011, 14, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, Y.; Takubo, K.; Aida, J.; Araki, A.; Ito, H. Telomere attrition and diabetes mellitus. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16 Suppl 1, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, M.J.; Hughes, D.A. Chromosomal telomere attrition as a mechanism for the increased risk of epithelial cancers and senescent phenotypes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006, 49, 1726–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bure, I.V.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Kuznetsova, E.B. Histone modifications and non-coding RNAs: mutual epigenetic regulation and role in pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherazi, S.A.M.; Abbasi, A.; Jamil, A.; Uzair, M.; Ikram, A.; Qamar, S.; Olamide, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Fried, P.J.; Ljubisavljevic, M.; et al. Molecular hallmarks of long non-coding RNAs in aging and its significant effect on aging-associated diseases. Neural. Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 959–968. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.J.; Kim, K. New Insights into the Role of Histone Changes in Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Grant, P.A. The role of DNA methylation and histone modifications in transcriptional regulation in humans. Subcell. Biochem. 2012, 61, 289–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gharipour, M.; Mani, A.; Amini Baghbahadorani, M.; de Souza Cardoso, C.K.; Jahanfar, S.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; de Oliveira, C.; Silveira, E.A. How Are Epigenetic Modifications Related to Cardiovascular Disease in Older Adults? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Mao, C.; Liu, S.; Tao, Y.; Xiao, D. Epigenetic modifications in obesity-associated diseases. MedComm (2020). 2024, 5, e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rönn, T.; Ofori, J.K.; Perfilyev, A.; Hamilton, A.; Pircs, K.; Eichelmann, F.; Garcia-Calzon, S.; Karagiannopoulos, A.; Stenlund, H.; Wendt, A.; et al. Genes with epigenetic alterations in human pancreatic islets impact mitochondrial function, insulin secretion, and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odimegwu, C.L.; Uwaezuoke, S.N.; Chikani, U.N.; Mbanefo, N.R.; Adiele, K.D.; Nwolisa, C.E.; Eneh, C.I.; Ndiokwelu, C.O.; Okpala, S.C.; Ogbuka, F.N.; et al. Targeting the Epigenetic Marks in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Will Epigenetic Therapy Be a Valuable Adjunct to Pharmacotherapy? Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 3557–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Chakraborty, R.; Faizy, A.F.; Moin, S. Exploring the key role of DNA methylation as an epigenetic modulator in oxidative stress related islet cell injury in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. J. Diabetes. Metab. Disord. 2024, 23, 1699–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasishta, S.; Ammankallu, S.; Poojary, G.; Gomes, S.M.; Ganesh, K.; Umakanth, S.; Adiga, P.; Upadhya, D.; Prasad, T.S.K.; Joshi, M.B. High glucose induces DNA methyltransferase 1 dependent epigenetic reprogramming of the endothelial exosome proteome in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2024, 176, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Hodge, A.M.; Southey, M.C.; Giles, G.G.; Dugué, P.A. Association of Epigenetic Markers of Aging With Prevalent and Incident Type 2 Diabetes. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glaf085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, C.S.; Rasmussen, B.B. Skeletal muscle protein balance and metabolism in the elderly. Curr. Aging. Sci. 2011, 4, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, B.T.; Gorissen, S.H.; Pennings, B.; Koopman, R.; Groen, B.B.L.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Aging is accompanied by a blunted muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion. PLoS. ONE. 2015, 10, e0140903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, C.S.; Kobayashi, H.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Aarsland, A.; Wolfe, R.R. Aging is associated with diminished accretion of muscle proteins after the ingestion of a small bolus of essential amino acids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, D.; Smith, K.; Babraj, J.; Leese, G.; Waddell, T.; Atherton, P.; Wackerhage, H.; Taylor, P.M.; Rennie, M.J. Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle. FASEB. J. 2005, 19, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, E.T.; Morimoto, R.I.; Dillin, A.; Kelly, J.W.; Balch, W.E. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009, 78, 959–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Nathan, J.A.; Goldberg, A.L. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.; Nielsen, S.; Mogensen, C.E.; Jakobsen, J. Muscle strength in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004, 53, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Kuller, L.H.; Broudeau, R.; Kammerer, C.; de Rekeneire, N.; Harris, T.B.; Schwartz, A.V.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Cho, Y.; Newman, A.B. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes. Care. 2007, 30, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.Y.; Wei, H.J.; Tang, Y.Y. Isthmin: A multifunctional secretion protein. Cytokine. 2024, 173, 156423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Voilquin, L.; Jung, Y.; Aikio, M.A.; Sahai, T.; Dou, F.Y.; Roche, A.M.; Carcamo-Orive, I.; Knowles, J.W.; et al. Isthmin-1 is an adipokine that promotes glucose uptake and improves glucose tolerance and hepatic steatosis. Cell. Metab. 2021, 33, 1836–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Banhos Danneskiold-Samsøe, N.; Ulicna, L.; Nguyen, Q.; Voilquin, L.; Lee, D.E.; White, J.P.; Jiang, Z.; Cuthbert, N.; et al. Phosphoproteomic mapping reveals distinct signaling actions and activation of muscle protein synthesis by Isthmin-1. Elife. 2022, 11, e80014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hou, R.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Pan, X.; Zhu, X. Lifestyle effects on aging and CVD: A spotlight on the nutrient-sensing network. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.L.; Lamming, D.W.; Fontana, L. Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2022, 23, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Cao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, N.; Lu, Q.; Crimmins, E.M.; Gill, T.M.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z. Association of Unhealthy Lifestyle and Childhood Adversity With Acceleration of Aging Among UK Biobank Participants. JAMA. Netw. Open. 2022, 5, e2230690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Rodrigues, T.M.; Kelly, G.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Girao, H. Intercellular communication and aging. Aging, Fundam. Biol. Soc. Impact 2023, 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, N.; Azzimato, V.; Choudhury, R.P.; Aouadi, M. Extracellular vesicles in metabolic disease. Diabetologia. 2019, 62, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, G.A.; Georgiadou, E.; Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Pullen, T.J. Metabolic and functional specialisations of the pancreatic beta cell: gene disallowance, mitochondrial metabolism and intercellular connectivity. Diabetologia. 2020, 63, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guan, T.; Shafiq, K.; Yu, Q.; Jiao, X.; Na, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Kong, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2023, 88, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinti, M.V.; Fink, G.K.; Hathaway, Q.A.; Durr, A.J.; Kunovac, A.; Hollander, J.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an organ-based analysis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 316, E268–E285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Joseph, A.J.; Adedoyin, E.D.; Iheagwam, O.T.; Ejoh, S.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetes: Shedding Light on a Widespread Oversight. Pathophysiology. 2025, 32, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolla, T.A.; Denu, J.M. NAD+ deficiency in age-related mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell. Metab. 2014, 19, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McReynolds, M.R.; Chellappa, K.; Baur, J.A. Age-related NAD+ decline. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 134, 110888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covarrubias, A.J.; Perrone, R.; Grozio, A.; Verdin, E. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2021, 22, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickam, R.; Santhana, S.; Xuan, W.; Bisht, K.; Tipparaju, S. Nampt: a new therapeutic target for modulating NAD(+) levels in metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 103, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskovska, T.; Bernlohr, D.A. The Role of NAD(+) in Metabolic Regulation of Adipose Tissue: Implications for Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance. Biomedicines. 2023, 11, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Baker, D.; d'Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2021, 22, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Zhu, Y. Cellular senescence: a key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e158450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo-Mazzucato, C.; Andle, J.; Lee, T.B.; Midha, A.; Talemal, L.; Chipashvili, V.; Hollister-Lock, J.; van Deursen, J.; Weir, G.; Bonner-Weir, S. Acceleration of β cell aging determines diabetes and senolysis improves disease outcomes. Cell. Metab. 2019, 30, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F.; Li, Q. Expressions of IGF-1R and Ki-67 in breast cancer patients with diabetes mellitus and an analysis of biological characteristics. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 38, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudurí, E.; Soriano, S.; Almagro, L.; García-Heredia, A.; Rafacho, A.; Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Nadal, Á.; Quesada, I. (2022). The effects of aging on male mouse pancreatic β-cell function involve multiple events in the regulation of secretion: influence of insulin sensitivity. Journals. Gerontology. Ser. A, Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, J.; Reinisch, I.; Schupp, M.; Schulz, T.J.; Prokesch, A. p53 functions in adipose tissue metabolism and homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Inagaki, N.; Kondoh, H. Cellular senescence in diabetes mellitus: distinct senotherapeutic strategies for adipose tissue and pancreatic β cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 869414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Hu, J.; Li, N.; Gao, J.; Huo, R.; Peng, X.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, R.; et al. The Mechanism of Stem Cell Aging. Stem. Cell. Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenzi, D.C.; Trac, J.Z.; Teoh, H.; Gerstein, H.C.; Bhatt, D.L.; Al-Omran, M.; Verma, S.; Hess, D.A. Vascular Regenerative Cell Exhaustion in Diabetes: Translational Opportunities to Mitigate Cardiometabolic Risk. Trends. Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadini, G.P.; Ciciliot, S.; Albiero, M. Concise Review: Perspectives and Clinical Implications of Bone Marrow and Circulating Stem Cell Defects in Diabetes. Stem. Cells. 2017, 35, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, Y.; Schmauck-Medina, T.; Hansen, M.; Morimoto, R.I.; Simon, A.K.; Bjedov, I.; Palikaras, K.; Simonsen, A.; Johansen, T.; Tavernarakis, N.; et al. Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nat. Aging. 2021, 1, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metaxakis, A.; Ploumi, C.; Tavernarakis, N. Autophagy in Age-Associated Neurodegeneration. Cells. 2018, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.S.; Lee, M.S. Macroautophagy in homeostasis of pancreatic beta-cell. Autophagy. 2009, 5, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Choi, M.E. Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 224, R15–R30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivot, K.; Pasquier, A.; Goginashvili, A.; Ricci, R. Breaking Bad and Breaking Good: beta-Cell Autophagy Pathways in Diabetes. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 1494–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, C.; Conteh, A.M.; Marasco, M.R.; Crowder, J.J.; Kuipers, J.; de Boer, P.; Linnemann, A.K. Pancreatic beta cell autophagy is impaired in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021, 64, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemkour, Y.; Lenoir, O. Endothelial Autophagy Dysregulation in Diabetes. Cells. 2023, 12, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznick, R.M.; Zong, H.; Li, J.; Morino, K.; Moore, I.K.; Yu, H.J.; Liu, Z.X.; Dong, J.; Mustard, K.J.; Hawley, S.A.; et al. Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell. Metab. 2007, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, V.; Benedetti, F.; Buriani, A.; Fortinguerra, S.; Caudullo, G.; Davinelli, S.; Zella, D.; Scapagnini, G. Immunomodulatory and Antiaging Mechanisms of Resveratrol, Rapamycin, and Metformin: Focus on mTOR and AMPK Signaling Networks. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022, 15, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Guo, Z.; Song, C. AMPK, a key molecule regulating aging-related myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell. Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via an integrated signaling network. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, J.; Bains, Y.; Guha, S.; Kahn, A.; Hall, D.; Bose, N.; Gugliucci, A.; Kapahi, P. The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in Aging and Metabolic Diseases: Bridging Association and Causality. Cell. Metab. 2018, 28, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Aragones, G.; Renneburg, C.; Francisco, S.G.; Kageyama, S.; Komatsu, M.; Taylor, A. Targeting mTOR pathway to ameliorate glycation-derived proteotoxicity in retinal and lens cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 3099. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, M.J. AMP-activated protein kinase: a therapeutic target in intestinal diseases. Open. Biol. 2017, 7, 170104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gongol, B.; Sari, I.; Bryant, T.; Rosete, G.; Marin, T. AMPK: An Epigenetic Landscape Modulator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Maiuri, A.R.; O'Hagan, H.M. The emerging role of epigenetic modifiers in repair of DNA damage associated with chronic inflammatory diseases. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019, 780, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.M.; Pendlebury, D.F.; Nandakumar, J. Structural biology of telomeres and telomerase. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2020, 77, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.R.; Choi, H.C. Telomere stabilization by metformin mitigates the progression of atherosclerosis via the AMPK-dependent p-PGC-1α pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1967–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoli, D.; Boulay, K.; Kazak, L.; Pollak, M.; Mallette, F.A.; Topisirovic, I.; Hulea, L. mTOR as a central regulator of lifespan and aging. F1000Res. 2019, 8, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Luo, W.; Liu, R.; Xu, D.; Diao, L.; Liao, L.; Liu, Z. Phosphorylation of ULK1 affects autophagosome fusion and links chaperone-mediated autophagy to macroautophagy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, A.S.; Basu, A. The Emerging Roles of mTORC1 in Macromanaging Autophagy. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Sauve, A.A. NAD+ content and its role in mitochondria. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2015, 1241, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cantó, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feige, J.N.; Lagouge, M.; Noriega, L.; Milne, J.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Puigserver, P.; Auwerx, J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009, 458, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.K.; Konja, D.; Singh, S.; Chlopicki, S.; Wang, Y. Endothelial SIRT1 as a target for the prevention of arterial aging: promises and challenges. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 2021, 78, S63–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Hu, C.; Zhao, D.; Li, X. SIRT1-SIRT7 in diabetic kidney disease: biological functions and molecular mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne), 2022, 13, 801303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Bai, S.; Liang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liao, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, B.; Huang, D.; Chen, M.; Wu, D. The role of Sirtuin 1 and its activators in age-related lung disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Luo, X.; Zhang, B. Activating SIRT1 deacetylates NF-κB p65 to alleviate liver inflammation and fibrosis via inhibiting NLRP3 pathway in macrophages. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yao, S.Y.; Chen, Q.; Jin, H.; Du, M.Q.; Xue, Y.H.; Liu, S. True or false? Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes: Evidences from bench to bedside. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerra, V.G.; Areti, A.; Kumar, A. Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase Abates Hyperglycaemia-Induced Neuronal Injury in Experimental Models of Diabetic Neuropathy: Effects on Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Autophagy and Neuroinflammation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2301–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy Chowdhury, S.K.; Smith, D.R.; Saleh, A.; Schapansky, J.; Marquez, A.; Gomes, S.; Akude, E.; Morrow, D.; Calcutt, N.A.; Fernyhough, P. Impaired adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase signalling in dorsal root ganglia neurons is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy in diabetes. Brain. 2012, 135, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Yu, H.; Zhou, L.; Su, H.; Li, X.; Qi, W.; Lian, F. Tang Bi formula alleviates diabetic sciatic neuropathy via AMPK/PGC-1α/MFN2 pathway activation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.H.; Lv, X.; Du, W.; Cheng, M.J.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhu, L.; Hao, J. The Akt/mTOR cascade mediates high glucose-induced reductions in BDNF via DNMT1 in Schwann cells in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Exp. Cell. Res. 2019, 383, 111502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, T.; Sureda, A.; Shirooie, S. Role of natural mTOR inhibitors in treatment of diabetes mellitus. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 37, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, C.; Meng, Z.; Gan, L.; Guo, R.; Liu, J.; Bond Lau, W.; Xie, D.; Zhao, J.; Lopez, B.L.; et al. C1q/TNF-Related Protein 3 Prevents Diabetic Retinopathy via AMPK-Dependent Stabilization of Blood-Retinal Barrier Tight Junctions. Cells. 2022, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.; Cha, S.; Lee, K.J.; Woo, H.N.; Park, K.; Lee, H. mTOR inhibition as a novel gene therapeutic strategy for diabetic retinopathy. PLoS. One. 2022, 17, e0269951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.C.; Tang, S.Q.; Liu, Y.T.; Li, A.M.; Zhan, M.; Yang, M.; Song, N.; Zhang, W.; Wu, X.Q.; Peng, C.H.; et al. AMPK agonist alleviate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis via activating mitophagy in high fat and streptozotocin induced diabetic mice. Cell. Death. Dis. 2021, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Jiao, Y.; Tian, J.; An, J.; Zou, G.; Zhuo, L. mTOR pathway: A key player in diabetic nephropathy progression and therapeutic targets. Genes. Dis. 2024, 12, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda-Yamahara, M.; Kume, S.; Maegawa, H. Roles of mTOR in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary Moghaddam, R.; Samimi, Z.; Asgary, S.; Mohammadi, P.; Hozeifi, S.; Hoseinzadeh-Chahkandak, F.; Xu, S.; Farzaei, M.H. Natural AMPK Activators in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 738420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldirim, M.; Lang, A.; Pfeiler, S.; Fiegenbaum, P.; Kelm, M.; Bönner, F.; Gerdes, N. Modulation of mTOR Signaling in Cardiovascular Disease to Target Acute and Chronic Inflammation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 907348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Z. Post-translational modifications orchestrate mTOR-driven cell death in cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1620669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, N.; Shi, F.X.; Xu, W.Q.; Cao, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, J.Z.; Tian, Q.; Zhou, X.W. Upregulation of AMPK Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease-Like Tau Pathology and Memory Impairment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 3349–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueed, Z.; Tandon, P.; Maurya, S.K.; Deval, R.; Kamal, M.A.; Poddar, N.K. Tau and mTOR: The Hotspots for Multifarious Diseases in Alzheimer's Development. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaka, D.; Bitra, V.R.; Challa, S.R.; Adiukwu, P.C. mTOR signaling as a molecular target for the alleviation of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Neurochem. Int. 2022, 155, 105311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, H.J.; Yao, P.; Huynh, F.K.; Escoubas, C.C.; Goncalves, R.L.; Burkewitz, K.; Laboy, R.; Hirschey, M.D.; Mair, W.B. Dietary Restriction and AMPK Increase Lifespan via Mitochondrial Network and Peroxisome Remodeling. Cell. Metab. 2017, 26, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsian, R.; Velingkaar, N.; Kondratov, R. Caloric restriction effects on liver mTOR signaling are time-of-day dependent. Aging (Albany NY). 2018, 10, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Shahinfar, H.; Gregg, E.W.; Shab-Bidar, S. Effect of calorie restriction in comparison to usual diet or usual care on remission of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, M.; Guo, L.; Chen, W.; Yu, L. Vitamin E exerts a mitigating effect on LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating macrophage polarization through the AMPK/NRF2/NF-κB pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 159, 114893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Hou, L.; Song, H.; Xu, P.; Sun, Y.; Wu, K. Akt/AMPK/mTOR pathway was involved in the autophagy induced by vitamin E succinate in human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 424, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asbaghi, O.; Nazarian, B.; Yousefi, M.; Anjom-Shoae, J.; Rasekhi, H.; Sadeghi, O. Effect of vitamin E intake on glycemic control and insulin resistance in diabetic patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Min, S.; Hong, R.; Zou, M.; Zhou, D. High-dose Vitamin C inhibits PD-L1 expression by activating AMPK in colorectal cancer. Immunobiology. 2025, 230, 152893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, G.; Chen, L.; Geng, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, C.; Wu, S.; Yao, J.; Deng, L. Pharmacological vitamin C inhibits mTOR signaling and tumor growth by degrading Rictor and inducing HMOX1 expression. PLoS. Genet. 2023, 19, e1010629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Hosseini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Salamat, S.; Nadery, M.; Yarmand, S.; Zamani, M.; Wong, A.; et al. The effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Weikel, K.A.; Cacicedo, J.M.; Ido, Y. Resveratrol-Induced AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activation Is Cell-Type Dependent: Lessons from Basic Research for Clinical Application. Nutrients. 2017, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Jeong, H.; Lee, M.N.; Koh, A.; Kwon, O.; Yang, Y.R.; Noh, J.; Suh, P.G.; Park, H.; Ryu, S.H. Resveratrol induces autophagy by directly inhibiting mTOR through ATP competition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino, F.M.; Figueiredo, L.M. Resveratrol supplementation and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 4465–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W. Activation of the AMPK-mTOR Pathway by Astaxanthin Against Cold Ischemia-Reperfusion in Rat Liver. Tohoku. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 265, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakaze, M.; Kobashi, C.; Satou, Y.; Shigeta, K.; Toshima, M.; Takagi, M.; Takahashi, J.; Nishida, H. The Beneficial Effects of Astaxanthin on Glucose Metabolism and Modified Low-Density Lipoprotein in Healthy Volunteers and Subjects with Prediabetes. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppedisano, F.; Macrì, R.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Bosco, F.; Nucera, S.; Caterina Zito, M.; Guarnieri, L.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines. 2020, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Pei, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Luo, H.; Sun, T. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids promotes locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 5894–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Ardisson Korat, A.V.; Imamura, F.; Marklund, M.; Tintle, N.; Virtanen, J.K.; Zhou, X.; Bassett, J.K.; Lai, H.; Hirakawa, Y.; et al. n-3 Fatty Acid Biomarkers and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: An Individual Participant-Level Pooling Project of 20 Prospective Cohort Studies. Diabetes. Care. 2021, 44, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.; Singh, H.; Kumari, P.; Chopra, H.; Sharma, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K.; et al. Metformin: Activation of 5' AMP-activated protein kinase and its emerging potential beyond anti-hyperglycemic action. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1022739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Lux, A.; O'Callaghan, F. The journey of metformin from glycaemic control to mTOR inhibition and the suppression of tumour growth. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaie, N.; Masoumi, S.; Alizadeh, S.; Mirzajanzadeh, P.; Nejabati, H.R.; Hajiabbasi, M.; Alivirdiloo, V.; Basmenji, N.C.; Derakhshi Radvar, A.; Majidi, Z.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and AMPK: The road to cellular housekeeping? Cell. Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, J.A.; AlAkwaa, F.M.; McCown, P.J.; Naik, A.S.; Nair, V.; Eddy, S.; Menon, R.; Otto, E.A.; Demeke, D.; Hartman, J.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors mitigate kidney tubular metabolic and mTORC1 perturbations in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2023, 133, e164486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Liu, M.; Lu, Z.; Hu, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cai, F.; et al. Activation of AMPK by GLP-1R agonists mitigates Alzheimer-related phenotypes in transgenic mice. Nat. Aging. 2025, 5, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parichatikanond, W.; Pandey, S.; Mangmool, S. Exendin-4 exhibits cardioprotective effects against high glucose-induced mitochondrial abnormalities: Potential role of GLP-1 receptor and mTOR signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 229, 116552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, P.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, S.; Ding, X.; Xiong, H. The novel GLP-1/GIP dual agonist DA3-CH improves rat type 2 diabetes through activating AMPK/ACC signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2023, 15, 11152–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, N.; Shi, W.; Xing, Y.; Liu, S.; Meng, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Y.; Xie, S.; Deng, W. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide/glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist tirzepatide promotes branched chain amino acid catabolism to prevent myocardial infarction in non-diabetic mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozumi, K.; Sugawara, K.; Ishihara, T.; Ishihara, N.; Ogawa, W. Effects of imeglimin on mitochondrial function, AMPK activity, and gene expression in hepatocytes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).