Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Nature and Scope of NSSI

1.2. Risk and Resilience for NSSI Engagement

1.3. Motives for NSSI Engagement

1.4. Traditional African Conceptualizations of Disease and Distress

1.5. This Review

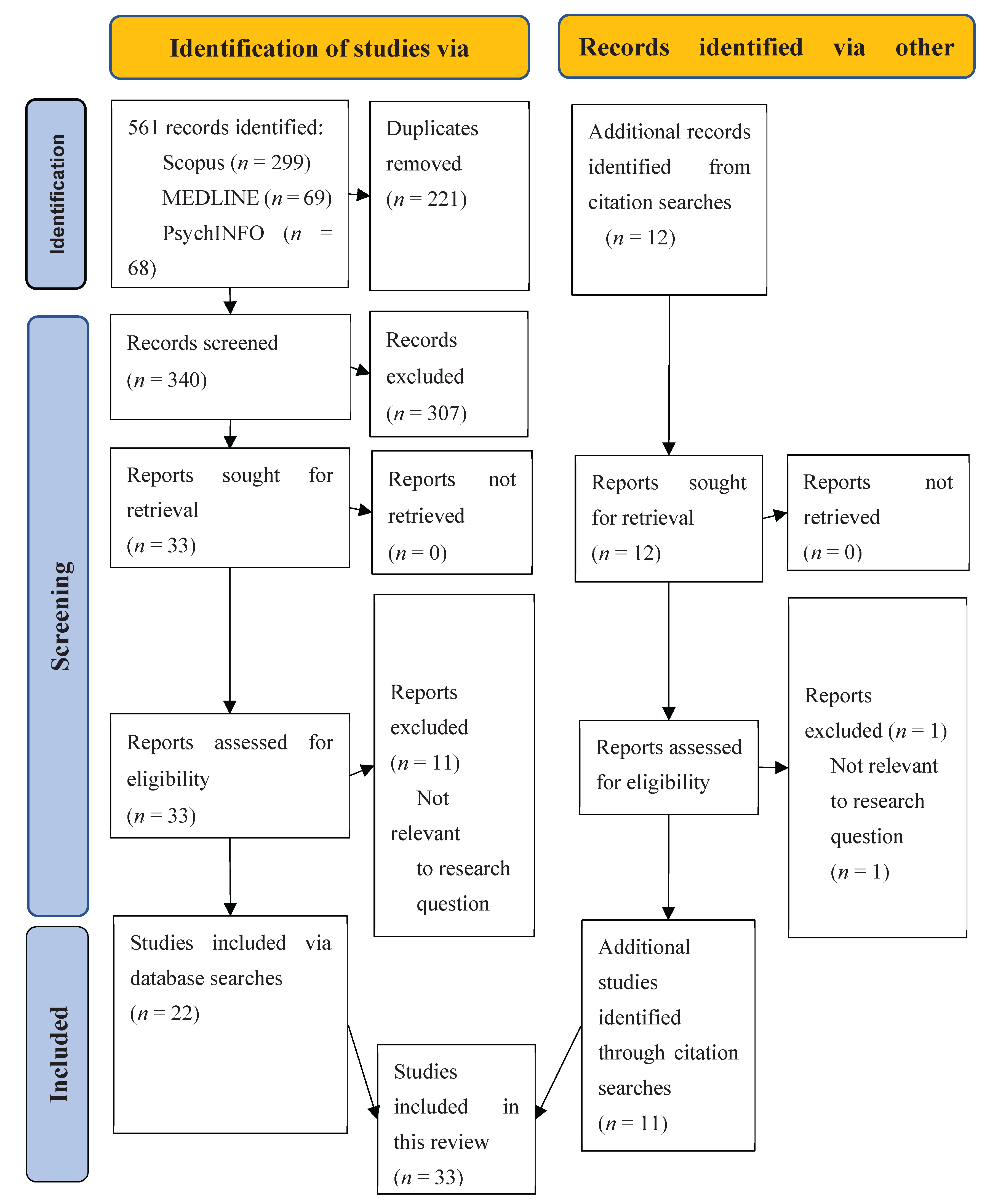

2. Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Descriptions

3.2. Data Synthesis

3.1.1. Analytic Theme 1: The Nature of NSSI

3.1.2. Analytic Theme 2: Risk/Protective Factors for NSSI

3.2.3. Analytic Theme 3: Functions of NSSI

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Research on NSSI

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angelotta C. Defining and refining self-harm: A historical perspective on nonsuicidal self-injury. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015, 203(2), 75-80. [CrossRef]

- Chaney, S. Psyche on the Skin: A History of Self-Harm. Reakton Books: London, 2017.

- Kahan, J.; Pattison, E.M. Proposal for a distinctive diagnosis: The Deliberate Self-Harm Syndrome (DSH). Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1984. 14, 17-35. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Ed. American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M.; Lundh, L-G.; Dahlström, Ö.; Svedin, C.G. Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41(5), 759–773. [CrossRef]

- Brager-Larsen, A.; Zeiner, P.; Mehlum, L. DSM-5 non-suicidal self-injury disorder in a clinical sample of adolescents with recurrent self-harm behavior. Arch. Suicide Res. 2023, 28(2), 523–536. [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Brausch, A.M.; Washburn, J.J. How much is enough? Examining frequency criteria for NSSI disorder in adolescent inpatients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85 (6), 611–619. [CrossRef]

- Armoon, B.; Mohammadi, R.; Griffiths, M.D. The global prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury, suicide behaviours, and associated risk factors among runaway and homeless youth: A meta-analysis. Community Ment. Health 2024, 60, 919–944. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, B.F.; Takacs, Z.K.; Kollárovics, N.; Balázs, J. The prevalence of self-injury in adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 33(10), 3439-3458. [CrossRef]

- Gillies, D.; Christou, M.A.; Dixon, A.C.; Featherston, O.J.; Rapti, I.; Garcia-Anguita, A.; Villasis-Keever, M.; Reebye, P.; Christou, E.; Al Kabir, N.; Christou, P.A. Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: Meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990-2015. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018, 57(10):733-741. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.S.; Wong, C.H.; McIntyre, R.S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tran, B.X.; Tan, W.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16(22):4581. [CrossRef]

- Moloney, F.; Amini, J.; Sinyor, M.; Schaffer, A.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Mitchell, R.H.B. Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Netw, Open 2024, 7(6), e2415436. [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Claes, L.; Havertape, L.; Plener, P.L. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2012, 30(6). [CrossRef]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; St John, N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat, Behav. 2014, 44(3):273-303. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Hou, D.; Huang, X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 912441. [CrossRef]

- Bresin, K.; Schoenleber, M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015, 38, 55-64. [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, E.N.; Waterman, M.G.; House, A.O. Self-harm with suicidal and non-suicidal intent in young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020, 20(1), 234. [CrossRef]

- Penning, S.L.; Collings, S.J. Perpetration, revictimization, and self-injury: Traumatic re-enactments of child sexual abuse in a nonclinical sample of South African adolescents. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2014, 23(6), 708–726. [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, L. Self-destructive behaviour in adolescents. S. Afr. Med. J. 1985, 68(11), 792-795. https:/ut/journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA20785135_5340.

- van der Walt, F. Self-harming behaviour among university students: A South African case study. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26(6), 508–512. [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, W; George, A.A. Social support-oriented coping and resilience for self-harm protection among adolescents. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28(3), 237–241. [CrossRef]

- Plener, P.L.; Schumacher, T.S.; Munz, L.M.; Groschwitz, RC. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2015, 30, 2:2. [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G.; Hasking, P.; Claes, L.; Mortier, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Boyes, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Kessler, R.C.; Nock, M.K.; Bruffaerts, R. The DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder among incoming college students: Prevalence and associations with 12-month mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35(7), 629-637. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, X. Non-suicidal self-injury function: prevalence in adolescents with depression and its associations with non-suicidal self-injury severity, duration and suicide. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1188327. [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.J.; Valjee, S.R. A multi-mediation analysis of the association between adverse childhood experiences and non-suicidal self-injury among South African Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1221. [CrossRef]

- Shenk, C.E.; Noll, J.G.; Cassarly, J.A. A multiple mediational test of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39(4), 335–342. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.D.; Wong, P.W.C.; Lee, A.M.; Lam, T.H.; Fan, Y.S.S.; Yip, P.S.F. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: Prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013, 48, 1133-1144. [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, B.S. Early childhood environment and genetic interactions: The diathesis for suicidal behavior. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 86. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Lugo-Marín, J.; Oriol, M.; Pérez-Galbarro, C.; Restoy, D.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Ferrer, M. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2024, 157, 107048. [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.Y.Y.; Hartanto, A.; Wan, T.S.; Teo, S.S.M.; Sim, L.; Sandeeshwara Kasturiratna, K.T.A. The impact of childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect on suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2025, 5(1), 100202. [CrossRef]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M.; Sivagurunathan, M.; Lateef, R.; Alaggia, R.; McElvaney, R.; Simpson, M. “How many times did I not want to live a life because of him”: The complex connections between child sexual abuse, disclosure, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. BPDED 2021, 8, 1. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Conrad, R.; Tang, Y.L. Factors associated with non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 30(12), 747031. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, L. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: Testing a moderated mediating model. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39(5-6), 925-948. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Shang, Y.; Huang, T.; Jiang, W.; Yuan, Y. Child maltreatment exposure and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of difficulty in emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Gong, T.; Liu, X.; Leung, F.; You, J. Distress intolerance mediates the relationship between child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 2220-2230. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Scopelliti, K.M.; Pittman, S.K.; Zamora, A.S. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5(1), 51-64. [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, M.H.; Boonmann, C. Child sexual abuse and problems reported by survivors of CSA: A meta-review. J. Child Sex Abuse 2021, 31(2), 147–176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022, 46,101350. [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, J.K.; Millner, A.J.; Joyce, V.W.; Nash, C.C.; Buonopane, R.; Nock, M.K.; Kleiman, E.M. Social support and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022, 50(10):1351-1361. [CrossRef]

- Simundic, A.; Argento, A.; Mettler, J.; Heath, N. L. Perceived social support and connectedness in non-suicidal self-injury engagement. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, W.; Ding, W.; Song, S.; Qian, L.; Xie, R. Your support is my healing: the impact of perceived social support on adolescent NSSI — a sequential mediation analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X. Social support and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: The differential influences of family, friends, and teachers. J. Youth Adolescence 2025, 54, 414–425. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Hoye, A.; Slade, A.; Tang, B.; Holmes, G.; Fujimoto, H.; Zheng, W.Y.; Ravindra, S.; Christensen, H.; Calear, A.L. Motivations for self-Harm in young people and their correlates: A systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2025, January, 29. [CrossRef]

- Westers, N.J. Cultural interpretations of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: Insights from around the world. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2024, 29(4):1231-1235. [CrossRef]

- Lurigio, A.J.; Nesi, D.; Meyers, S.M. Nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults and adolescents: Historical, cultural and clinical understandings. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2023, 22(1), 122–148. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Hou, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Influential factors of non-suicidal self-Injury in an Eastern cultural context: A qualitative study from the perspective of school mental health professionals. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 681985. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Sheehan, A.E.; Walsh, R.F.L.; Sanzari, C.M.; Cheek, S.M.; Hernandez, E.M. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019, 74, 101783. [CrossRef]

- Meisler, S.; Sleman, S.; Orgler, M.; Tossman, I.; Hamdan, S. Examining the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and mental health among female Arab minority students: The role of identity conflict and acculturation stress. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1247175.

- Elvina, N.; Bintari, D.R. The role of religious coping in moderating the relationship between stress and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI). Humaniora 2023, 14(1), 11-21. [CrossRef]

- Good, M.; Chloe Hamza, H.; Willoughby, T. A longitudinal investigation of the relation between nonsuicidal self-injury and spirituality/religiosity Psychiatry Res. 2017, 250, 106-112. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.S. Cross-cultural representations of NSSI. In The Oxford Handbook of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E., Baetens, I., Whitlock J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 167–186. Oxford University Press.2024; pp.167-186, 2024,.

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, M.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, P.; Xu, X. Family intimacy and adaptability and non-suicidal self-injury: A mediation analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024 Mar 18;24(1):210. [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Xiang, Y. Child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of psychological resilience and loneliness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 133, 106335. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, Z.; Ma, T.; Jiang, X.; Yu, C.; Xu, Q. Stressful life events and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of depression and resilience. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 944726. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cai, Y.; Pan, M. Correlation analysis of non-suicidal self-injury behavior with childhood abuse, peer victimization, and psychological resilience in adolescents with depression. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2024, 52(3), 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Zorobi, M.A.; Mahfar, M.; Fakhruddin, F.M.; Senin, A.A. The Relationship between resilience, loneliness, and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents in Johor Bahru. IJRBS 2024, 14(2), 1714–1726. [CrossRef]

- Nock, M,K.; Prinstein, M.J. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Oct;72(5):885-90. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J Affect Disord. 2018, 227, 759-769. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Luyckx, K.; Adhikari, A.; Parmar, D.; Desousa, A.; Shah, N.; Maitra, S.; Claes, L. Non-suicidal self-injury and its association with identity formation in India and Belgium: A cross-cultural case-control study. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021 Feb;58(1):52-62. [CrossRef]

- Gholamrezaei, M.; De Stefano, J.; Heath, N.L. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury across cultures and ethnic and racial minorities: A review. Int. j. psychol. 2017, 52(4), 316–326. [CrossRef]

- 61 Sogolo, G. On a socio-cultural conception of health and disease in Africa. Africa: Rivista Trimestrale Di Studi e Documentazione Dell’Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente 1984, 41(3), 390-404. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40760024.

- Edet, R.; Bello, O.I.; Babajide, J. Culture and the development of traditional medicine in Africa. J Adv Res Humani Social Sci 2019, 6(3), 22-28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/827.

- Curtis, A.C. Defining adolescence. JAFH 2015, 7, 2, 2. https://scholar.utc.edu/jafh/vol7/iss2/2.

- Lizarondo, L.; Stern, C.; Carrier, J.; Godfrey, C.; Rieger, K.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Loveday, H. Mixed methods systematic reviews (2020). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, Eds.; JBI, Chapter 8, 2024. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global Accessed on: 30 November 2024).

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual, Health Res. 2012, 22(10):1435-1443. [CrossRef]

- Bramer ,W.M.; Giustini, D.; de Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016, 104(3):240-243. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. Motives underlying bulimic and self-mutilating behaviour. Master’s Thesis, Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1996. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10210/7573 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Toerien, S. Selfdestruktiewe gedrag by die adolessent: ‘n Maatskaplikewerk perspektief (Self-destructive behaviour in the adolescent: A social work perspective). Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/7a6f4c05-46b8-43e8-8e79-96ab9fd07cac/content (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Kok, R.; Kirsten, D.K.; Botha, K.F.H. Exploring mindfulness in self-injuring adolescents in a psychiatric setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2011, 21(2), 185–195.

- Pretorius, S. Deliberate self-harm among adolescents in South African children’s homes. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/df293fe8-579c-4236-81d3-bc819f33a9e4/content (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bheamadu, C.; Fritz, E.; Pillay, J. The experiences of self-injury amongst adolescents and young adults within a South African context. J. Psychol. Afr. 2012, 22(2), 263–268. [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, M.J. Every scar tells a story: The meaning of adolescent self-injury. Master’s Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa.; Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/items/62e33aab-f581-4033-a7da-039bfced87f9 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Akhaddar, A.; Malih, M. Neglected painless wounds in a child with congenital insensitivity to pain. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17, 95. [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, D.; Jacobs, I. An only-child adolescent’s lived experience of parental divorce. Child Abuse Research: A South African Journal 2015, 16(2), 116-129. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC180366 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Idemudia, E,S.; Mokoena, K.M.; Maepa, M.M. Dynamics of gender, age, father involvement and adolescents’ self-harm and risk-taking behaviour in South Africa. Gend. Behav. 2016, 14(1), 6846-6859. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC19234471.

- Kintu-Luwaga, R. The emerging trend of self-circumcision and the need to define cause: Case report of a 21-year-old male. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 2016, 25, 225-228. [CrossRef]

- Stancheva, V.P. Self-mutilation in adolescents admitted to Tara Psychiatric Hospital: Prevalence and characteristics. Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstreams/0659521b-efe5-4491-9b0c-78656fcc8dd7/download (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Guedria-Tekari, A.; Missaoui, S.; Kalai, W.; Gaddour, N.; Gaha, L. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Tunisian adolescents: Prevalence and associated factors. Pan Afr. med. j. 2019, 34, 105. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S. The prevalence, nature, and functions of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a South African student sample. SAJE 2019, 39(3), 1697. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mohamed, N.A. Prevalence and correlates of deliberate self-harming behaviors among nursing students. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 8(2), 52-61. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jnhs/papers/vol8-issue2/Series-7/G0802075261.pdf.

- Maepa, M.P., Ntshalintshali, T. Family structure and history of childhood trauma: Associations with risk-taking behavior among adolescents in Swaziland. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 563325. [CrossRef]

- Quarshie E.N-B.; Waterman, M.G.; House, O.A. Adolescent self-harm in Ghana: A qualitative interview-based study of first-hand accounts. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 275. [CrossRef]

- Reyneke, A.; Naidoo, S. An exploration of the relationship between interpersonal needs and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents. SAJSWSD 2020, 32 (3), 7640. [CrossRef]

- Boduszek, D.; Debowska, A.; Ochen, E.A.; Fray, C.; Nanfuka, E.K.; Powell-Booth, K.; Turyomurugyendo, F.; Nelson, K.; Harvey, R.; Willmott, D.; Mason, S.J. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among children and adolescents: Findings from Uganda and Jamaica, J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 172-178. [CrossRef]

- Oduaran, C.; Agberotimi, S. F. Moderating effect of personality traits on the relationship between risk-taking behaviour and self-injury among first-year university students. ADV MENT HEALTH 2021, 19(3), 247–259. [CrossRef]

- El Nagar, Z.M.; Barakat, D.H.; Rabie, M.A.E.M.; Thabeet, D.M.; Mohamed, M.Y. Relation of non-suicidal self-harm to emotion regulation and alexithymia in sexually abused children and adolescents. J Child Sex Abus. 2022, 31(4), 431-446. [CrossRef]

- Yedong, W.; Coulibaly, S.P.; Sidibe, A,M.; Hesketh, T. Self-harm, suicidal ideation and attempts among school-attending adolescents in Bamako, Mali. Children (Basel) 2022, 9(4), 542. [CrossRef]

- Ebalu, T.I.; Kearns, J.C.; Ouermi, L.; Bountogo, M.; Sié, A.; Bärnighausen, T.; Harling, G. Prevalence and correlates of adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A population-based study in Burkina Faso. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69(7), 1626-1635. [CrossRef]

- Gudugbe, S.; Acquah, E.P.K.; Akuaku, R.S.; Jaaga, B.N.N.B.; Maison, P. Teasing-induced self-circumcision in a teenager: A case report. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2023, 35 (24), 147-151. [CrossRef]

- Jaguga, F.; Mathai, M.; Ayuya, C.; Francisca, O; Musyoka, C.M.; Shah, J.; Atwoli, L. 12-month substance use disorders among first-year university students in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2023, 18(11), e0294143. [CrossRef]

- Kukoyi, O.; Orok, E; Oluwafemi, F.; Oni, O.; Oluwadare1, T.; Ojo, T.; Bamitale, T.; Jaiyesimi, B.; Iyamu, D. Factors influencing suicidal ideation and self-harm among undergraduate students in a Nigerian private university. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 2023, 30, 1. [CrossRef]

- Abdou, E.A.; Haggag, W.; Anwar, K.A.; Sayed, H.; Ibrahim, O. Methods and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in an adolescent and young adult clinical sample. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 2024, 31(10). [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Wolke, D.; Bärnighausen, T.; Ouermi, L.; Bountogo, M.; Harling, G. Sexual victimisation, peer victimisation, and mental health outcomes among adolescents in Burkina Faso: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11(2):134-142. [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Maravilla, J.C.; Wado, Y.D.; Wahdi, A.E.; Loi, V.M.; Fine, S.L.; Li, M.; Ramaiya, A.; Wekesah, F.M.; Odunga, S.A.; Njeri, A.; Setyawan, A.; Astrini, Y.P.; Rachmawati, R.; Hoa, D.T.K.; Wallis, K.; McGrath, C…Scott, J.G. Prevalence of adolescent mental disorders in Kenya, Indonesia, and Viet Nam measured by the National Adolescent Mental Health Surveys (NAMHS): A multi-national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2024, 403, 10437, 1671-1680. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T…Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, M-C.; Vedel, I. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49-59. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, N.; Van Rompaey, C.; Metreau, E.; Eapen, S.G. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2022–2023, 2022. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, USA 2022. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health 2019/2021. Available at: https://icd.who.int/en/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Shoqer, Z. (2006). Scale of Diagnosing Self-Punishment, 1st Ed. Nahdet Misr Publishing, Cairo, 2006 (not available online). For a description of the scale see: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jnhs/papers/vol8-issue2/Series-7/G0802075261.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Theron, L.; Ungar, M.; Höltge, J. Pathways of resilience: Predicting school management trajectories for South African adolescents living in a stressed environment. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 69, 102062. [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Murphy, K.; Jeffries, P. Researching multisystemic resilience: A sample methodology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3808. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2021, 17, 521-549. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Basic Documents. 49th Ed. Geneva: WHO, 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-en.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Series, 1577, 3. Chicago: 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

| Construct | Operationalization of key constructs |

|---|---|

| Sample/ Participants/ Population |

patient, participant, sample, (the names of each African country), adolescent, young adult, youth, young people, teenager |

| Phenomenon of interest | non-suicidal self-injury, NSSI, self-injury, self-harm, parasuicide, self-mutilation, deliberate self-harm, self-inflicted violence, cutting, prevalence, incidence, risk, protective factors, resilience, function, interpersonal function, intrapersonal function, social function, cultural function |

| Design/data collection | prospective, cross-sectional, cross-sectional survey, chart review, cohort design, case-control study, clinical assessment, case study, questionnaire, survey, interview, autoethnography, focus group, observation, file review |

| Evaluation | statistical analysis, effect size, reliability, validity, credibility, prevalence, theme, thematic analysis, self-reflection, autoethnographic analysis, discourse analysis, self-reflexivity |

| Research type | quantitative, qualitative, mixed method |

|

Reference |

Researcher location |

Sample |

Procedure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Author (date) |

Country (income level) |

Source (sampling strategy) |

Size |

Age: M (SD) (range) |

% Female |

Measurement (mode of data collection) |

Design |

| Schlebusch (1985) [19] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience) |

548 | 15.80 (10-19) |

73.6 | Quantitative (review of clinical records) |

Cross-sectional |

| Moore (1996) [67] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience) |

4 | Median = 21.0 18-25 |

100.0 | Qualitative (in-depth interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Toerien (2005) 68] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Community sample (convenience) |

3 | Median = 16.0 14-17 |

100.0 | Qualitative (in-depth interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Kok, et al. (2011) [69] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience) |

8 | 14.50 (1.41) (13-17) |

62.5 | Mixed methods (interview/clinical records) |

Cross-sectional |

| Pretorius (2011) [70] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Community sample (convenience) |

12 | 14.5 (1.88) 12-17 |

83.3 | Mixed methods (questionnaire/interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Bheamadu et al. (2012) [71] |

South Africa (UMI) |

University students (convenience) |

12 | Median = 20.0 (18-22) |

91.7 | Qualitative (interview/journal review) |

Cross-sectional |

| Ridgway (2013) [72] |

South Africa UMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience) |

4 | Median 15.5 14-17 |

100.0 | Qualitative (in-depth interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Akhaddar; Malih (2014) [73] |

Morocco (LMI) |

Clinical case study (convenience) |

1 | 13 (N/A) |

00.0 | Qualitative (clinical assessment) |

Cross-sectional |

| Penning; Collings (2014) [18] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School children (convenience) |

718 | 15.5 (11.6) (15-20) |

34.0 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Dorfman; Jacobs (2015) [74] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Community sample (convenience) |

1 | An adolescent (not specified) |

100.0 | Qualitative (in-depth interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Idemudia et al. (2016) [75] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School children (convenience) |

479 | 16.60 (1.11) (14-20) |

36.7 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Kintu-Luwaga (2016) [76] |

South Sudan (low-income) |

Clinical case study (convenience) |

1 | 21 .00 (N/A) |

00.0 | Qualitative (clinical assessment |

Cross-sectional |

| Stancheva (2016) [77] |

South Africa (UMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience |

334 | 15.8 (1.31) (13-18) |

73.2 | Quantitative Review of clinical records |

Cross-sectional |

| van der Walt (2016) [20] |

South Africa (UMI) |

University students (convenience) |

201 | 21.40 (19-24) |

55.0 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Van der Wal; George (2018) [21] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School children (convenience |

962 | 16.34 (0.84) (14-18) |

57.9 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Guedria-Tekari, et al. (2019) [78] |

Tunisia (LMI) |

School children (probability) |

821 | 17.70 (0.97) (13-19) |

68.2 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Naidoo (2019) [79] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School/university (convenience) |

623 | 17.81 (2.42) (13-24) |

73.8 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Ramadan; Mohamed (2019) [80] |

Egypt (LMI) |

University students (convenience) |

1,272 | 20.38 (1.55) 18-25 |

59.7 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Maepa; Ntshalintshali 2020 [81] | Eswatini (LMI) |

School students (convenience) |

470 | 16.57 (2.19) (12-25) |

50.6 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Quarshie, et al. (2020 [82] |

Ghana (LMI) |

Community/school (convenience) |

36 | 16.70 (13-20) |

72.2 | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) |

Cross-sectional |

| Reyneke; Naidoo (2020) [83] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School children (convenience) |

216 | 15.20 (13-19) |

76.9 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Boduszek et al. (2021) [84] |

Uganda (low-income) |

School children (convenience) |

11,518 | 13.74 (1.97) (9-17) |

60.8 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Oduaran; Agberotimi (2021) [85] |

South Africa (UMI) |

University students (convenience) |

312 | 18.51 (0.62) (17-19) |

59.6 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| El Nagar, et al. (2022) [86] |

Egypt (LMI) |

University students (convenience) |

80 | 15.37 (10-24) |

56.0 | Quantitative (interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Yedong et al. (2022) [87] |

Mali (low-income) |

School/university (convenience) |

606 | 16.1 (2.4) (10-20) |

47.5 | Quantitative (Questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Ebalu, et al. (2023) [88] |

Burkina Faso (low-income) |

Community sample (probability) |

1,538 | 15.20 (2.30) (12-20) |

40.4 | Quantitative (Questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Gudugbe et.al. (2023) [89] |

Ghana (LMI) |

Clinical case study (convenience) |

1 |

13 (N/A) |

00.0 | Qualitative (clinical interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Jaguga et al. (2023) [90] |

Kenya (LMI) |

University students (convenience) |

334 | 19.50 (1.4) (18-24) |

45,8 |

Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Kukoyi et al. (2023) [91] |

Nigeria (LMI) |

University students (convenience) |

450 | 20.20 (1.9) (17-27) |

61.3 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Abdou et al. (2024) [92] |

Egypt (LMI) |

Clinical sample (convenience) |

100 | 19.20 (1.8) (14-21) |

78.0 | Quantitative (interview/questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Collings; Valjee (2024) [25] |

South Africa (UMI) |

School children (convenience) |

636 | 15.40 (1.5) 12-18 |

34.4 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Lee et al. (2024) [93] |

Burkina Faso (low-income) |

Community sample (probability) |

1,644 | 15.10 (0.81) (12-20) |

40.4 | Quantitative (interview) |

Cross-sectional |

| Erskine et al. (2024) [94] |

Kenya (LMI) |

Community sample (probability) |

5,155 | 13.30 (280) (10-17) |

49.9 | Quantitative (questionnaire) |

Cross-sectional |

| Risk factors | Protective factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intrapersonal threats to an individual’s wellbeing |

Intrapersonal protective factors |

|||

| Personal characteristics | Personal characteristics | |||

| Younger adolescents (<15 years) at greater risk) [25,79] | Older age (>15 years) [87] | |||

| Self-identifying as female [18,19,20,75,76,77,78.83,90] | ||||

| A high pain threshold [73] | ||||

| Mental health | Mental/disorders | |||

| Emotion dysregulation [25,82,86] | High self-esteem [87] | |||

| PTSD [88,94] | ||||

| Depression [68.77,78,79,84,87,88,90,91,94] | ||||

| Anxiety [68,80,84,87,88,90,94] | ||||

| A substance use disorder [19,68,77,90] | ||||

| Low self-esteem [67,68,78,91] | ||||

| Personality traits and coping styles | Personality traits and coping styles | |||

| High scores on measures of mindfulness [69] | Social support orientated coping [21] | |||

| Openness to experience [85] | Low levels of mindfulness [69] | |||

| Low levels of emotional self-awareness [86] | Resilient personality traits [21] | |||

| Biographical risk factors | Biographical salutary factors | |||

| A history of adverse childhood experiences | Social support in the home [81,82] | |||

| A history of child maltreatment [18,82.88] | ||||

| Homelessness [82] | ||||

| Witnessing violence in the family home [68,72,74,77,82] | ||||

| Mental illness in the family home [19,77] | ||||

| Substance abuse in the family home [77,82] | ||||

| Adultification [82] | ||||

| Punitive and abusive parenting styles [82] | ||||

| Orphan hood [69,81] | ||||

| A past history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts [19,77,78] | ||||

|

Interpersonal threats to an individual’s wellbeing |

Intrapersonal protective factors |

|||

| Invalidating parental relationships [68,69,71] | Social support | |||

| Punitive, or abusive parenting styles [82] | From parents/surrogate parents [82,91] | |||

| Low levels of paternal involvement [75] | From peers [68,82] | |||

| Single-parent households [81] | Paternal involvement (75) | |||

| Social isolation and exclusion [71,89] | ||||

| Self-Perceptions of being a burden to others [83] | ||||

| Low levels of social support [68,90] | ||||

| Peer bullying [87] | ||||

| Peer contagion [70,87] | ||||

|

Socially/spiritually mediated threats to an individual’s wellbeing |

Socially mediated protective factors |

|||

| Parenting styles reflecting age/gender discrimination [82] | A desire to not violate religious beliefs about self-harm [82] | |||

| Discrimination (race, sex, and/or LGBTQ+ status) [25] | ||||

| Acculturation [82] | Self-harm viewed as a crime or a religious transgression [82] | |||

| Tabooed forms of emotional expression [82] | ||||

| Involvement in satanic cults [82] | Social support from charitable or welfare agencies [82] |

|||

| Manipulation by malevolent spiritual forces [82] | ||||

| Noncompliance with culturally prescribed rituals [76] | ||||

| Function | Illustrative example | |

|---|---|---|

|

Intrapersonal functions |

||

| Coping with distressing emotional states | ||

| Affect regulation | Reducing emotional/cognitive distress [68,70,71,72,74,79,92] | |

| Anti-suicide | Reducing suicidal urges [68.83] | |

| Anti-dissociation | Regulating dissociative feelings [68,79] | |

| Self-punishment | Guilt-driven self-punishment [72,80,86] | |

| Achieving a desired emotional state | ||

| An improved emotional state | “I had this euphoric feeling, a kind of high afterwards” [68,71] | |

|

Interpersonal functions |

||

| Coping with distressing relationships | ||

| Distressing family relationships | “My mom’s boyfriend hit her, I had to cut myself” [69,70,71,79] | |

| Distressing peer relationships | “I never fitted in, I loathed myself. Cutting took it away” [71] | |

| Obtaining a desired reaction from others | “I wanted to know if someone really cared about me” [68,79,82] | |

|

Socially mediated functions |

||

| Coping with socially mediated distress | ||

| Social derision and exclusion | Coping with sociocultural pressure to comply with culturally prescribed rituals and rites of passage [76] | |

| Discrimination | Coping with distress relating to discriminatory practices in relation to age and/or sex [25,82] | |

| Punitive parenting styles | Coping with punitive culturally sanctioned parenting styles [82] | |

| Obtaining a desired social reaction | ||

| Addressing the causes of social harm | Self-circumcision in order to avoid social derision [76,89] | |

| Conforming to social expectations | Ceasing self-injury to comply with cultural prescriptions [82] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).