Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Text and Music Reading

Eye Movements

Understanding the effects of the most basic features of music notation on the targeting and timing of eye movements seems essential before combining these observations with the effects of expertise, added visual elements, violation of musical expectations in complex settings, or even the distribution of attention between two staves.

Method

Analysis

Study 1 (Kinsler & Carpenter, 1995)

Study 2 (Polanka, 1995)

Study 3 (Waters et al., 1997), experiment 2

Study 4 (Waters & Underwood, 1998)

Study 5 (Penttinen & Huovinen, 2011)

Study 6 (Ahken et al., 2012)

Study 7 (Arthur et al., 2016)

Study 8 (Huovinen et al., 2018), experiment 2

Complexity of Musical Stimuli

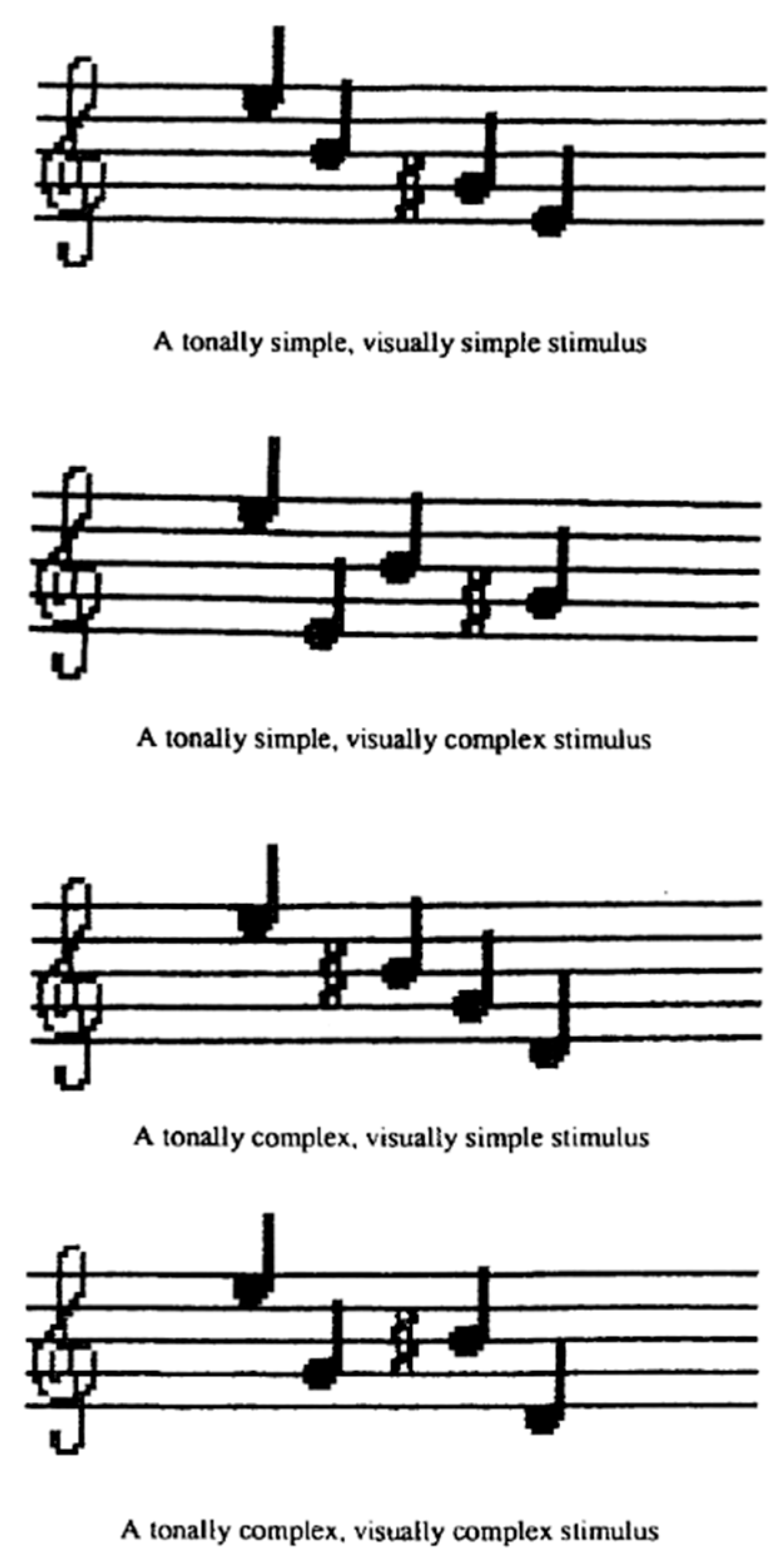

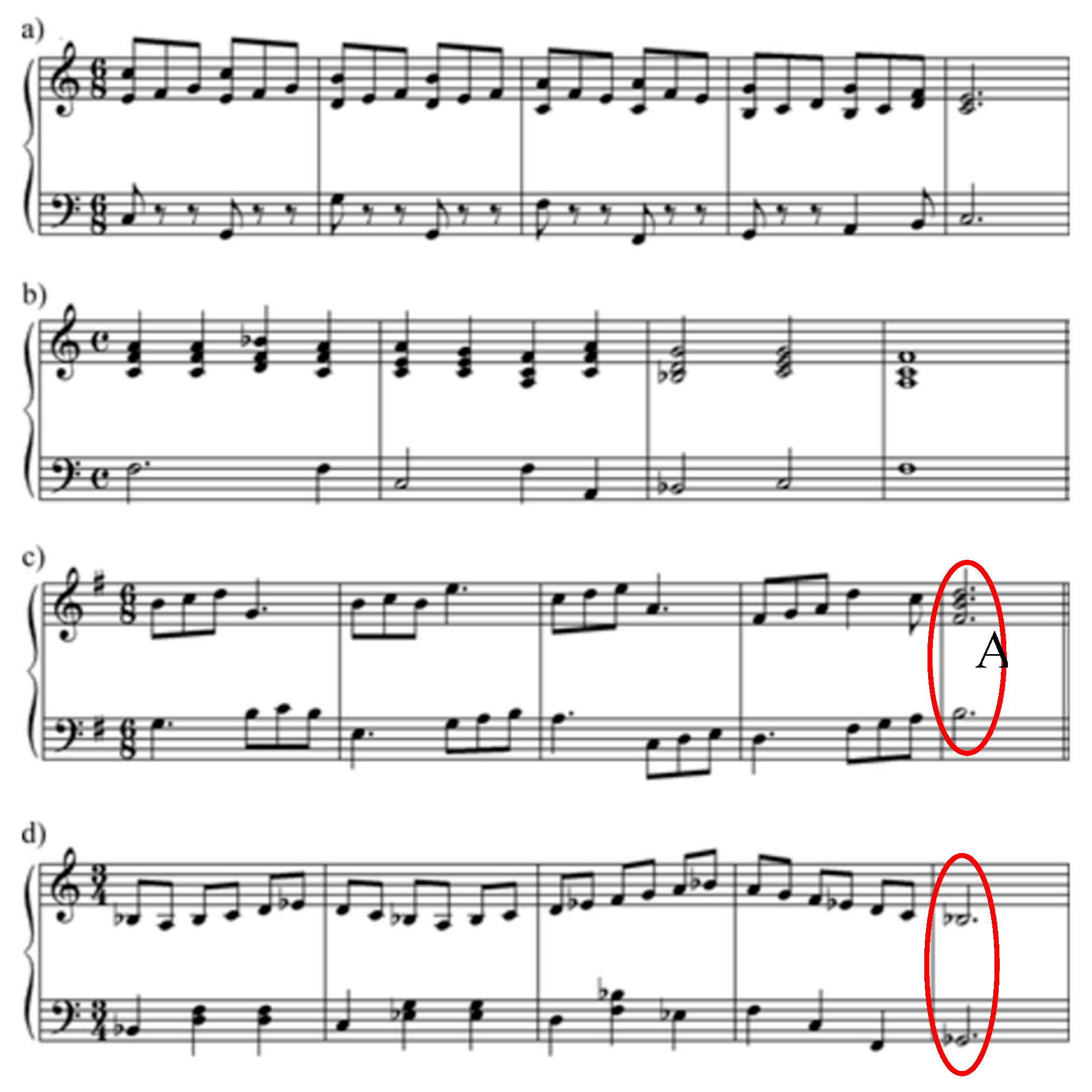

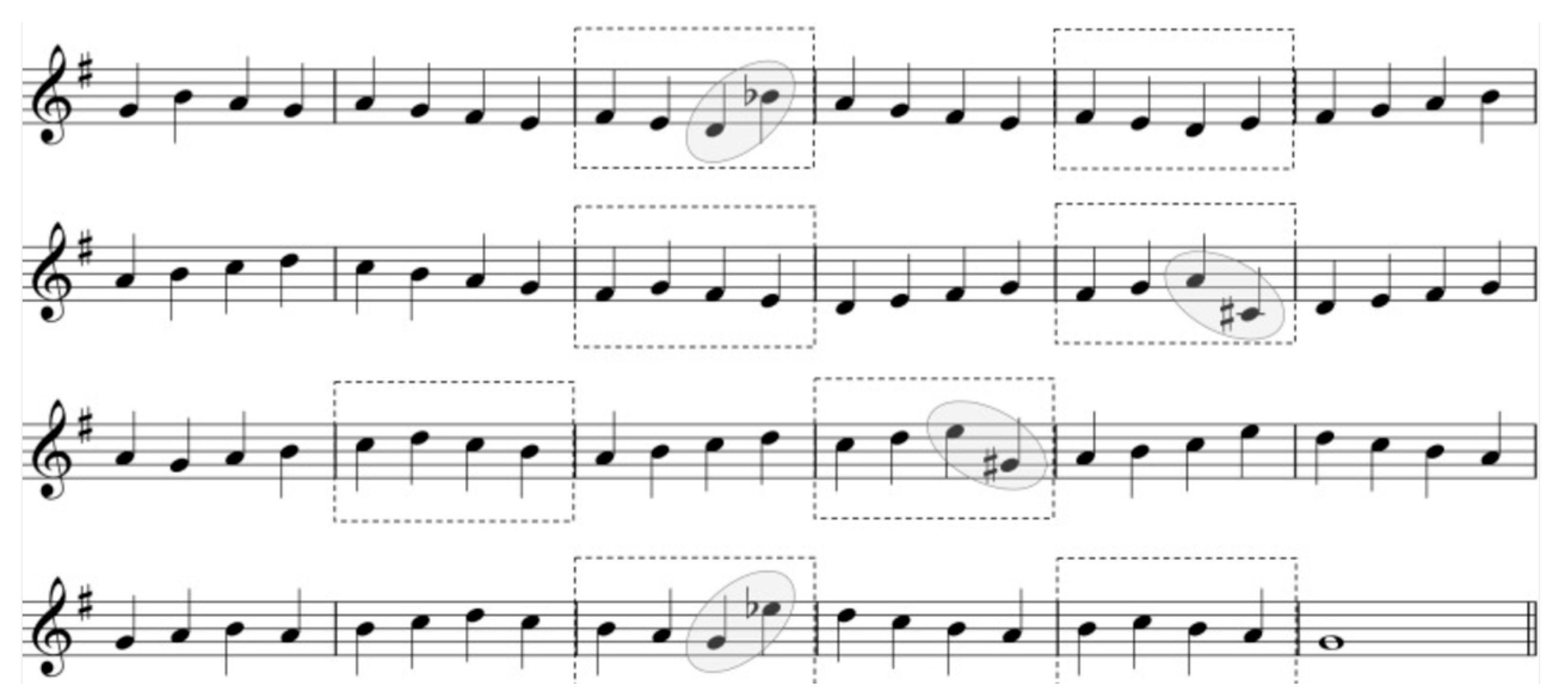

Twenty “Tonally Simple, Visually Simple” stimuli were composed with four notes preceded by a treble clef, forming simple scale or arpeggio structures. All notes fit within a single major diatonic scale, each containing two or fewer accidentals and one or no contour changes. Twenty “Tonally Simple, Visually Complex” stimuli retained the same musical structures but were arranged to include two contour changes. Twenty “Tonally Complex, Visually Simple” stimuli were created by altering one or two notes so they no longer fit within a single diatonic scale, or by repositioning accidentals. Finally, twenty “Tonally Complex, Visually Complex” stimuli combined these tonal alterations with two contour changes.

Unexpected Findings

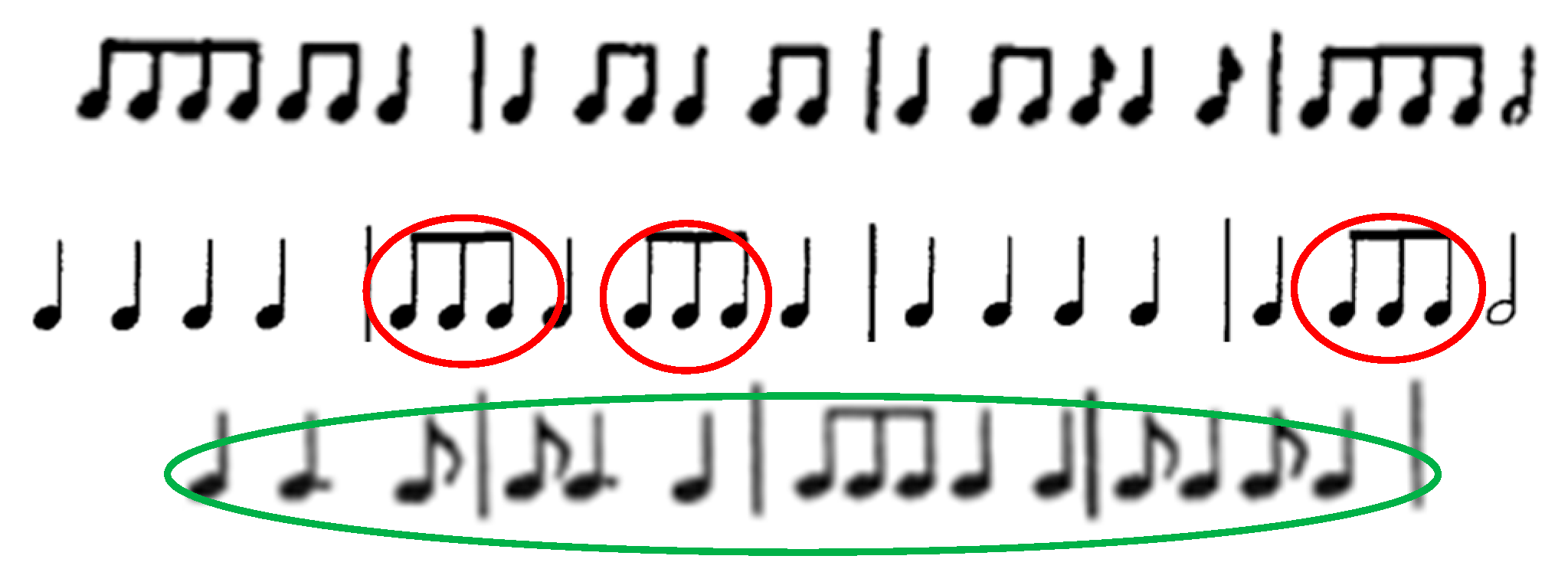

Sometimes a subject may fixate each of a pair of quavers individually, sometimes only one of them, or neither. (…) Comparison of the number of saccades made when performing musically identical bars with quavers notated either as isolated or beamed showed, for two subjects, a significant (P = 0.05) decrease with beaming, but for the other subject (RHSC), an equally significant increase—demonstrating again the idiosyncratic nature of the responses.

However, on the first stimulus presentation, it is interesting that there was no evidence that the tonal complexity of the material had any effect on the fixation durations of the experts, as might be predicted from Kinsler and Carpenter’s model. This is a curious finding since we would have expected the experts’ drop in accuracy on the more difficult material to have been due to encoding difficulties on the first stimulus presentation. Furthermore, there was no suggestion from the spatial data that the experts used larger saccade sizes for the tonally simple material. In other words, there was no evidence for any differences in eye movement behaviour between tonally simple and tonally complex material for the expert group.

Results and Discussion

Melodic and Harmonic Patterns

Rhythm Patterns

Complexity

- Does the use of accidentals contribute to tonal complexity, visual complexity, or both? In a musical context, accidentals increase harmonic complexity, but they also make the score visually more intricate.

- Do scales and triads affect tonal or visual complexity? These are basic and high-frequency musical structures.

- Can we meaningfully discuss musical structure, tonal progression, and complexity when the stimulus consists of only four notes, as in Waters and Underwood [47]?

- How do different note values and rhythmic patterns influence the complexity of a score, both generally and in relation to the instrument used in the experiment?

- Do accidentals increase complexity visually, tonally, or both?

- Does the use of two treble clefs or two bass clefs on a piano staff make the score more complex than the more common treble and bass clef combination?

- How do basic elements like scales and triads—and their density relative to tonally unrelated notes—affect perceived complexity?

- Is piano music with fingering more or less complex to read than music without fingering?

Music Instrument and Motor Planning

Interpretation of the Unexpected Findings

Comparison to Linguistic Stimuli

Conclusion

Funding

Statements and Declarations

References

- Ahken, S., Comeau, G., Hébert, S., & Balasubramaniam, R. (2012). Eye movement patterns during the processing of musical and linguistic syntactic incongruities. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 22(1), 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, R. (1994). Music and Language: Parallels and Contrasts. In R. Aiello & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), (pp. 40-63). Oxford University Press.

- Arthur, P., Khuu, S., & Blom, D. (2016). Music sight-reading expertise, visually disrupted score and eye movements. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 9(7), 35.

- Babayigit, Ö. (2019). The Reading Speed of Elementary School Students on the All Text Written with Capital and Lowercase Letters. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 7(2), 371-380.

- Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1975). The mind’s eyes in chess. In W. G. Chase (Ed.), Visual Information Processing (pp. 215-281). Academic.

- Clifton, C., Ferreira, F., Henderson, J. M., Inhoff, A. W., Liversedge, S. P., Reichle, E. D., & Schotter, E. R. (2016). Eye movements in reading and information processing: Keith Rayner’s 40year legacy. Journal of Memory and Language, 86, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Clifton, C., Staub, A., & Rayner, K. (2007). Eye movements in reading words and sentences. In R. P. G. Van Gompel, M. H. Fischer, W. S. Murray, & R. L. Hill (Eds.), Eye movements (pp. 341-371). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Dambacher, M., Slattery, T. J., Yang, J., Kliegl, R., & Rayner, K. (2013). Evidence for direct control of eye movements during reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39(5), 1468-1484. [CrossRef]

- Drake, C., & Palmer, C. (2000). Skill acquisition in music performance: relations between planning and temporal control. Cognition, 74(1), 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to Read Words: Theory, Findings, and Issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188. [CrossRef]

- Emond, B., & Comeau, G. (2013). Cognitive modelling of early music reading skill acquisition for piano: A comparison of the Middle-C and Intervallic methods. Cognitive Systems Research, 24, 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Feist, J. (2017). Berklee contemporary music notation. Hal Leonard Corporation.

- Fink, L. K., Lange, E. B., & Groner, R. (2019). The application of eye-tracking in music research. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Goolsby, T. W. (1994). Profiles of Processing: Eye Movements During Sightreading. Music Perception, 12, 97-123. [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010). Advances in music-reading research. Music Education Research, 12(4), 331-338. [CrossRef]

- Halsband, U., Binkofski, F., & Camp, M. (1994). The role of the perception of rhythmic grouping in musical performance: Evidence from motor-skill development in piano playing. Music Perception, 11(3), 265-288.

- Hambrick, D. Z., Oswald, F. L., Altmann, E. M., Meinz, E. J., Gobet, F., & Campitelli, G. (2014). Deliberate practice: Is that all it takes to become an expert? Intelligence, 45, 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D., Bernstorf, E., & Stuber, G. M. (2014). The music and literacy connection. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hodges, D. A., & Nolker, D. B. (1992). The acquisition of music reading skills. In R. Colwell (Ed.), Handbook of research on music teaching and learning (pp. 466-471). Schrimer Books.

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & Van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford University Press.

- Honing, H. (2013). Structure and interpretation of rhythm in music. In D. Deutsch (Ed.), The psychology of music (Vol. 3, pp. 369-404). Academic Press.

- Huovinen, E., Ylitalo, A. K., & Puurtinen, M. (2018). Early Attraction in Temporally Controlled Sight Reading of Music. J Eye Mov Res, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Kinsler, V., & Carpenter, R. H. S. (1995). Saccadic eye movements while reading music. Vision Research, 35(10), 1447-1458. [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S., Kasper, E., Sammler, D., Schulze, K., Gunter, T., & Friederici, A. D. (2004). Music, language and meaning: brain signatures of semantic processing. Nature neuroscience, 7(3), 302-307.

- Kopiez, R., & Lee, J. I. (2008). Towards a General Model of Skills Involved in Sight Reading Music. Music Education Research, 10(1), 41-62. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A. C., Sloboda, J. A., & Woody, R. H. (2007). Psychology for musicians: understanding and acquiring the skills. Oxford University Press.

- Lerdahl, F., & Jackendoff, R. (1996). A generative theory of tonal music. MIT Press.

- Lim, Y., Park, J. M., Rhyu, S.-Y., Chung, C. K., Kim, Y., & Yi, S. W. (2019). Eye-hand span is not an indicator of but a strategy for proficient sight-reading in piano performance. Scientific reports, 9(1), 17906. [CrossRef]

- Lörch, L. (2021). The association of eye movements and performance accuracy in a novel sight-reading task. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 14(4), 10.16910/jemr. 16914.16914. 16915.

- Madell, J., & Hébert, S. (2008). Eye Movements and Music Reading: Where Do We Look Next? Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 26(2), 157-170. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J. (2014). Improving sightreading accuracy: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Music, 42(2), 131-156. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. D. (2008). Music, Language, and the Brain. Oxford University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/hisbib/docDetail.action?docID=10211997.

- Patel, A. D. (2012). Advancing the comparative study of linguistic and musical syntactic processing. In P. Rebuschat, M. Rohrmeier, J. A. Hawkins, & I. Cross (Eds.), Language and music as cognitive systems (pp. 248-253). Oxford University Press.

- Penttinen, M., & Huovinen, E. (2011). The Early Development of Sight-Reading Skills in Adulthood:A Study of Eye Movements. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59(2), 196-220. [CrossRef]

- Perra, J., Latimier, A., Poulin-Charronnat, B., Baccino, T., & Drai-Zerbib, V. (2022). A Meta-analysis on the Effect of Expertise on Eye Movements during Music Reading. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Pike, P. D., & Carter, R. (2010). Employing Cognitive Chunking Techniques to Enhance Sight-Reading Performance of Undergraduate Group-Piano Students. International Journal of Music Education, 28(3), 231-246. [CrossRef]

- Polanka, M. (1995). Research Note: Factors Affecting Eye Movements During the Reading of Short Melodies. Psychology of Music, 23(2), 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Puurtinen, M. (2018). Eye on Music Reading: A Methodological Review of Studies from 1994 to 2017. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Radach, R., & Kennedy, A. (2013). Eye movements in reading: Some theoretical context. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66(3), 429-452. [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological bulletin, 124(3), 372. [CrossRef]

- Rebuschat, P., Rohrmeier, M., Hawkins, J. A., & Cross, I. (Eds.). (2012). Language and music as cognitive systems. Oxford University Press.

- Rosemann, S., Altenmüller, E., & Fahle, M. (2016). The art of sight-reading: Influence of practice, playing tempo, complexity and cognitive skills on the eye–hand span in pianists. Psychology of Music, 44(4), 658-673. [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, J. A. (2005). Exploring the musical mind: cognition, emotion, ability, function. Oxford University Press.

- Waller, D. (2010). Language literacy and music literacy: a pedagogical asymmetry. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 18(1), 26-44. [CrossRef]

- Waters, A., Townsend, E., & Underwood, G. (1998). Expertise in musical sight reading: A study of pianists. British Journal of Psychology, 89, 123-149.

- Waters, A. J., & Underwood, G. (1998). Eye Movements in a Simple Music Reading Task: A Study of Expert and Novice Musicians. Psychology of Music, 26(1), 46-60. [CrossRef]

- Waters, A. J., Underwood, G., & Findlay, J. M. (1997). Studying expertise in music reading: Use of a pattern-matching paradigm. Perception & Psychophysics, 59(4), 477-488. [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, K., & McPherson, G. E. (2022). Sight-reading. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance, Volume 1. Oxford University Press.

| Study | Aim (related to syntactic processing) | Participants | Stimuli | Procedure | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Kinsler & Carpenter, 1995) | To examine saccades while reading music: to be able to dissociate the contributions of factors associated with the input (the printed music) and with the output (the rate of execution). | No data. | Short rhythmic phrases presented as a single line of notes with bar lines. | Participants were suddenly presented with a line of notes on a computer screen and asked to tap the corresponding rhythm on a microphone. | At slow speeds with complex sequences there may be considerably more saccades than notes; with a fast speed and simple pattern---as here more notes than eye movements. |

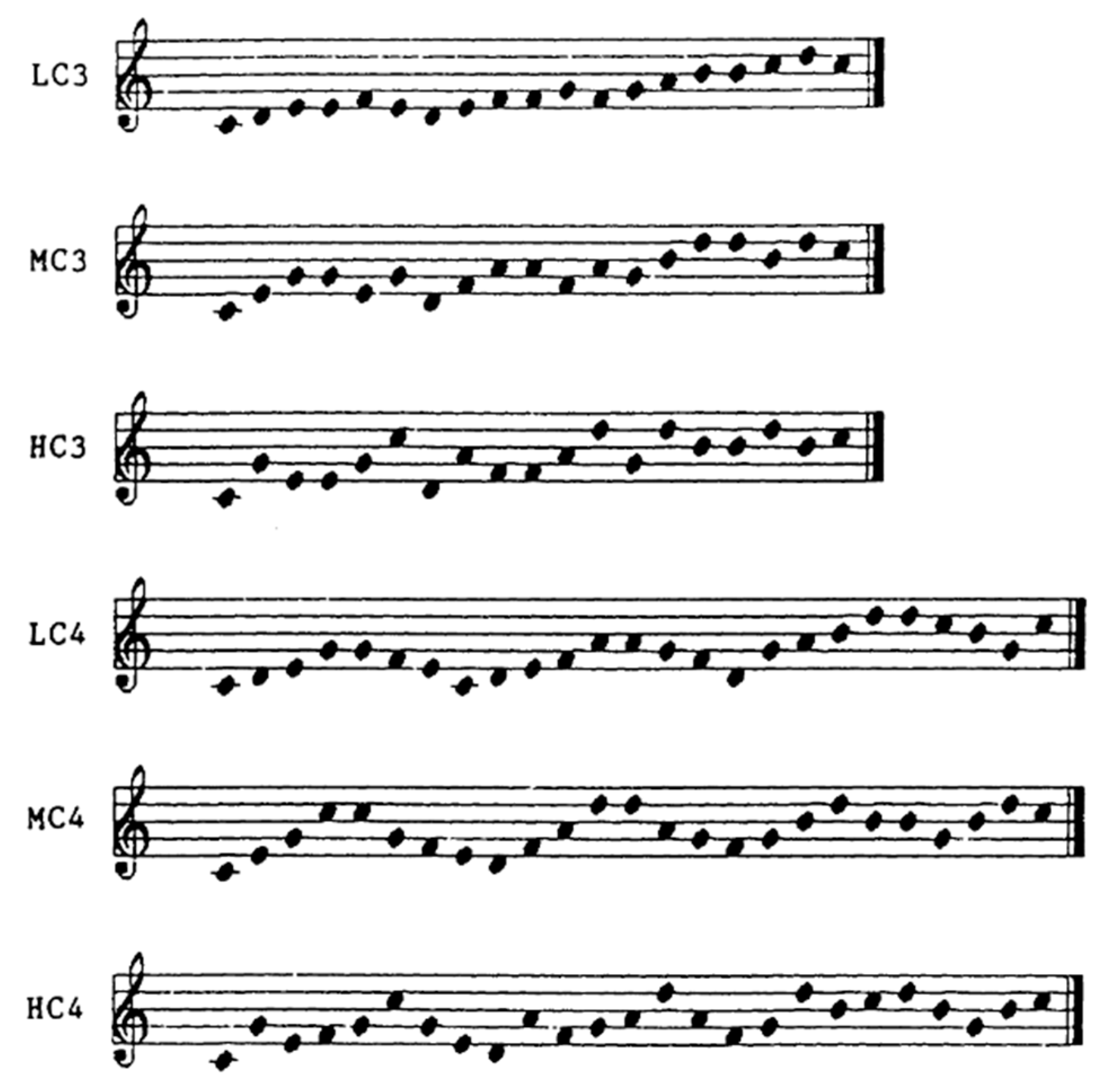

| 2 (Polanka, 1995) | To determine whether musicians read in higher order structures (patterns) or note by note by monitoring their eye movements as they sight-read. | 18 undergraduate music majors (11 females, 7 males), divided into three skill groups based on a sight-singing pretest. | Six melodies—three composed of three-note pitch patterns and three of four-note patterns, each with varying complexity (low, medium, high). | Subjects read each melody twice, once silently and once humming and their vocal responses were recorded on audio tape. | Better readers tended to process larger units than poorer readers. Pattern size influenced eye movement behavior. Stepwise patterns were processed in smaller units than triadic patterns. |

| 3 (Waters et al., 1997) exp.2 |

To test whether skilled sight-reading is associated with rapid processing of note groups and to examine the relationship between expertise and eye-movement parameters (e.g., fixation duration). | Three groups of 8 subjects each: two “expert” groups (full time music students playing a monophonic instrument) and a novice group (familiar with the names of the notes). | Sixty 10-note melodies in 3/4 or 4/4 time, each consisting of two bars of five notes each. No key signature or accidentals. Each melody had a randomized counterpart. | Silent reading, matching pairs of stimuli as same or different by pressing a button as quickly as possible. | Experienced musicians used larger units and processed them with fewer and shorter fixations. Musicians made more errors on duration-different trials, while nonmusicians made more errors on pitch-different trials. |

| 4 (Waters & Underwood, 1998) | To determine the effect of the tonal complexity of the stimuli on task performance and eye movement behaviour. To determine whether there was any difference in task performance and eye movement behaviour for expert and novice musicians. | Twenty-two subjects divided into two groups: “expert” group, experienced musicians playing at least one musical instrument associated with the treble clef register. The “novice” group, familiar with musical notation. | Twenty “Tonally Simple, Visually Simple” stimuli: four notes encompassed within one major diatonic scale, preceded by the treble clef, consisting of simple scale or arpeggio structures. Other stimuli with various complexity level were created by shifting some of the notes. | Silent reading. Each subject made a “same” response with their preferred hand, and a “different” response with their non-preferred hand. | Experts outperformed novices in speed and accuracy. Experts showed reduced performance on tonally complex material, while novices showed no difference. There was no evidence for any differences in eye movement behavior between tonally simple and tonally complex material for the expert group. |

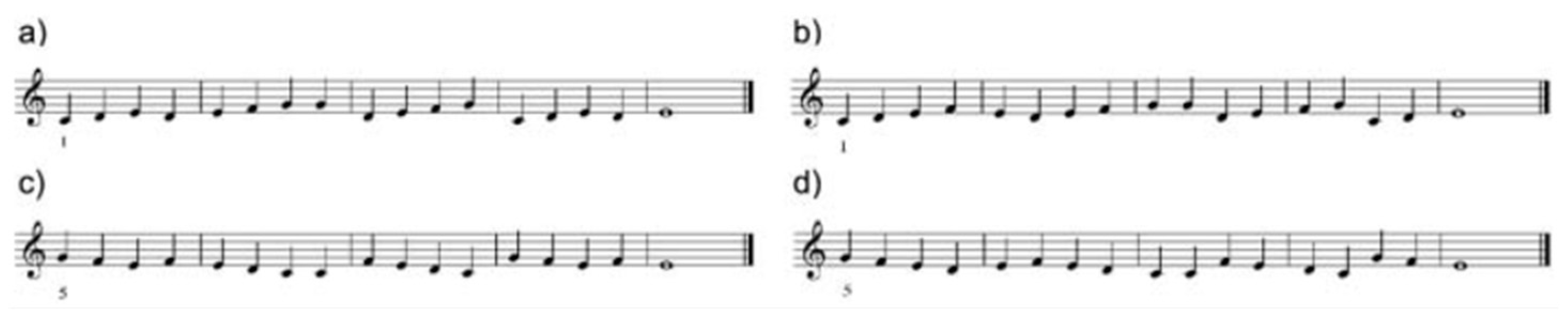

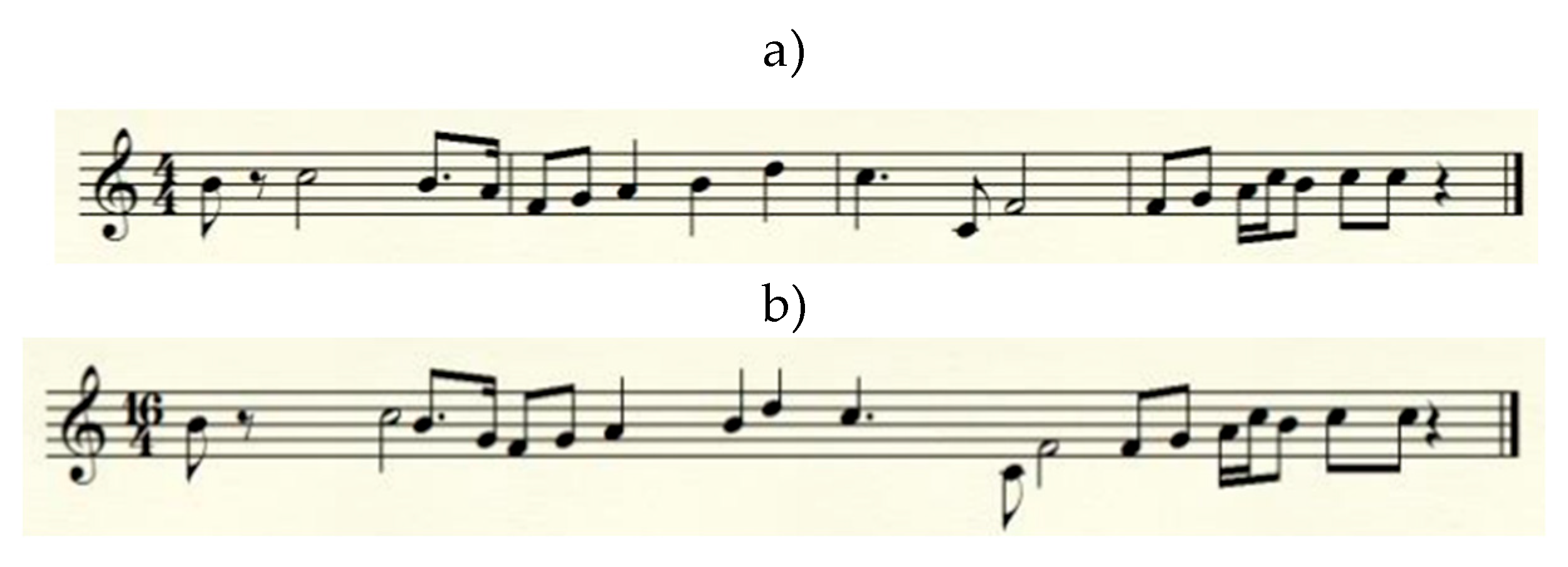

| 5 (Penttinen & Huovinen, 2011) | To elucidate the early stages of learning to read music in adulthood by examining the various measures of fixation time in elementary sight-reading tasks, and compare novices with experienced music amateurs. | 49 second-year teacher education students in Finland, all enrolled in a year-long compulsory music course. |

Twelve five-bar melodies in C major, using quarter notes and a whole note in the final bar. Melodic range: C4–G4. Fingering marked for the first note. The melodic movement in each melody was primarily stepwise, with the exceptions of two larger intervals at the temporal distance from one another. | Participants sight-read four melodies on piano with a metronome (60 bpm) at three time points: start, mid-point (16 weeks), and end of the course. | Sight-reading skills improved significantly. Fixation times decreased for central notes in large intervals, but not for surrounding notes. |

| 6 (Ahken et al., 2012) | Investigating the eye movements of readers during the visual processing of music and linguistic syntactic incongruities. To examine the role of key signature and accidentals to establish tonality. | Eighteen experienced pianists. | Sixteen short musical phrases (5–7 bars), grouped in fours. Half were syntactically congruent; the rest ended with a non-tonic chord or note. | Participants were instructed to play each musical sequence at the piano with hands together and no preview time, at any speed they liked. | Incongruent stimuli elicited more fixations, longer fixation durations, and longer trial durations. Effects were less pronounced for stimuli with accidentals than for those with key signatures. |

| 7 (Arthur, et al., 2016) | To explore how visual expectations influence sight-reading expertise, focusing on working memory, cross-modal integration, and visual crowding. The study examined eye movement responses to unexpected changes in notation observed in expert and non-expert music sightreaders. | 20 participants: 9 were assigned to the expert sight-reader group and 13 to the non-expert sightreader group. No data about their main instrument. | Ten four-bar melodies in treble clef, right-hand only, using white notes. Notational features were altered (e.g., bar line removal, stem direction, spacing). | Participants sight-read the 9 specifically composed musical excerpts of 4 bars duration on the piano. | Score disruption had no effect on total task time. Saccadic latency increased significantly for experts only when encountering disrupted notation. |

| 8 (Huovinen, et al., 2018), exp 2 | To examine the hypothesis stating that local increases in music-structural complexity (and thus visual salience) of the score may bring about local, stimulus-driven lengthening of the ETS [eye-time span]. | 14 professional piano students from three Finnish universities. | Eight mostly stepwise melodies in 4/4 time, each six bars long and composed entirely of quarter notes. The melodies were divided into two sets in the keys of G, C, F, and B♭. In each melody, one larger intervallic skip (a minor sixth) was inserted in one of bars 3–5. | The participants were instructed to sight-read the melodies on the piano in time with a metronome. | Experienced musicians appeared to react sensitively to upcoming deviant elements. Target notes triggered longer-than-average eye-time spans for notes occurring several beats before the target itself. Sight-readers often responded to the target element as early as six beats in advance. |

| Study | Syntactic units of information possible to “chunk” | Could be a part of an authentic piece | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melodic | Rhythmic | Harmonic | Phrases/ Repetitions | ||

| 1 (Kinsler & Carpenter, 1995) | Not applicable | limited | Not applicable | limited | no |

| 2 (Polanka, 1995) | limited | no | no | no | no |

| 3 (Waters et al., 1997), exp 2 | no | no | no | limited | no |

| 4 (Waters & Underwood, 1998) | no | no | limited | no | limited |

| 5 (Penttinen & Huovinen, 2011) | no | no | no | no | no |

| 6 (Ahken et al., 2012) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 7 (Arthur et al., 2016) | no | no | no | no | no |

| 8 (Huovinen et al., 2018), experiment 2 | no | no | no | no | no |

| Study | Description of the musical stimuli in the context of musical syntactic processing | Fictious equivalent of linguistic stimuli with the same degree of syntactic structure |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Kinsler & Carpenter, 1995) | Rhythmic stimuli without a time signature; complexity is introduced by violating notational conventions. | Unrelated words placed within a sentence in simple tasks, and non-words used in complex tasks. |

| 2 (Polanka, 1995) | A set of equally spaced dots indicating pitch on a staff with a treble clef, designed as short patterns. | Short, unrelated words written in an unusual font, presented as single capital letters with equal spacing in a continuous row. |

| 3 (Waters et al., 1997), exp 2 | Two-bar excerpts with a time signature but no key signature; pitches do not conform to C major tonality; rhythmic rules are intentionally violated. | Short sentences composed of non-words |

| 4 (Waters & Underwood, 1998) | Four-note excerpts on a staff, using quarter notes with or without accidentals, forming either major triads or random pitch sequences. | Single short words and similar non-words |

| 5 (Penttinen & Huovinen, 2011) | Five-bar excerpts using a random succession of notes from C4 to G4, with no rhythmic differentiation, time signature, or key signature. | Unrelated short words and non-words composed of the same five letters, placed within a sentence. |

| 6 (Ahken et al., 2012) | Five- to seven-bar excerpts in piano score format, with time and key signatures, harmonic and rhythmic patterns, and a syntactically incongruent final bar. | Meaningful sentences in which the final word does not match the context. |

| 7 (Arthur et al., 2016) | Four-bar excerpts with a time signature but no key signature; pitches and note values are randomly ordered and lack syntactic structure; spacing is manipulated. | Four complex non-words resembling real words, placed in a sentence with irregular spacing between letters, making word boundaries visually ambiguous. |

| 8 (Huovinen et al., 2018), experiment 2 | 24-bar excerpts with a key signature but no time signature or rhythmic variation (quarter notes only); no harmonic progression; complexity introduced via accidentals. | Unrelated short words and non-words, some with difficult spelling, placed in an unnaturally long sentence without punctuation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).