1. Introduction

Geopolitical risks (GPRs) are defined as the risks associated with acts of terrorism, as well as tensions and conflicts between nations (Caldara and Iacoviello, 2022). In an increasingly integrated global economy, the GPRs have emerged as significant factors influencing international trade dynamics. The GPRs impact trade flows through several key mechanisms, such as supply chain disruptions, trade barriers, investment flows, consumer behavior. The effect of GPRs on international trade has received considerable attention from scholars over the last few decades. Most empirical studies have reported that the GPRs have a significantly negative effect on trade flows between countries (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2018; Goswami & Panthamit, 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2023; Kim & Jin, 2023; Leitão, 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024; Liu & Fu, 2024; Zehri et al., 2025). It is noted that these studies have assumed that the effect of GPRs on international trade is symmetric, meaning that a decrease in GPRs has the same impact on international trade as an increase in GPRs with the same magnitude. However, the effect of the GPRs on international trade could be asymmetric due to some reasons as follows. First, negative geopolitical events tend to have immediate and pronounced adverse effects on international trade, while positive changes could not lead to equivalent benefits, as they often take time to influence trade dynamics. Second, international traders could be risk-averse in the face of geopolitical instability. Therefore, they could react to negative geopolitical events in a different way compared to positive one.

Over the past few decades, Vietnam's economy has undergone a transitional period marked by extensive integration into the global economy. Events like the Russia–Ukraine conflict and the U.S. – China trade war have disrupted Vietnam’s exports through sanctions, logistical bottlenecks, and shifts in global supply chains. In this context, Vietnam's international trade is very vulnerable to shocks from geopolitical events. Although the effect of GPRs on international trade has been investigated in both developed and developing countries, very little has been known about the effect of GPRs on Vietnam’s international trade. Therefore, this study focuses on examining the impact of GPRs on Vietnam's exports. This study contributes to the literature covering the effects of GPRs on international trade as follows. First, this study enriches the literature on the effect of GPRs on international trade in a transition economy. Vietnam, as a transitional economy with an extensive integration into the world economy, provides a unique context for examining the effect of GPRs on export performance. Second, while most empirical studies have investigated symmetrical effects of the GPRs on international trade, this study explores the asymmetric effects of the GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. Understanding asymmetric effects is crucial for policymakers, as it highlights the need for tailored strategies rather than the one-size-fits-all approach. Third, by using the NARDL bounds test approach to estimate the short-term and long-term relationships, this study provides comprehensive insights into the mechanisms through which the GPRs influence on export dynamics.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature while

Section 3 describes the data and methodology employed in the study.

Section 4 reports and discusses the research findings. Finally,

Section 5 provides the conclusions and implications.

2. Literature Review

The Gravity model of trade is a fundamental framework used to explain and predict international trade flows between countries. According to the Gravity model, the exports from one country to another are generally determined by the size of their economies and the geographical distance between them. Many empirical studies have utilized the Gravity model to examine the effect of geopolitical risks on international trade flows between countries for the last few decades. Specifically, based on the Gravity model, Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018) developed a model to determine the effects of terrorism on trade, highlighting that firms in trading nations face varying costs due to both domestic and transnational terrorism. The empirical findings derived from the model revealed that domestic and transnational terrorism have little or no significant effect on the overall trade of primary products, but both forms of terrorism significantly diminish the overall trade of manufactured goods. In addition, both domestic and transnational terrorism negatively impact manufactured imports. Moreover, domestic terrorism decreases manufactured exports and stimulates primary exports, whereas transnational terrorism leads to a decrease in primary exports. Similarly, Gupta et al. (2019) employed GPR index in a gravity model to investigate the effect of geopolitical risks (GPRs) on the trade flows between 164 developing and developed countries from 1985 to 2013. The main finding of the study is that GPRs have a negative effect on the trade flows. Additionally, using a gravity model framework, Goswami & Panthamit (2020) determined the effect of political risk on bilateral trade flows between Thailand and its trading partners for the period from 1984 to 2015. The study reported that increases in political risk substantially diminishes bilateral trade flows, highlighting the importance of political stability in promoting foreign trade relationships. Besides, Singh et al. (2023) employed a gravity model to examine the effect of GPRs on trade patterns for seven of the largest economies in Latin America from 2000 to 2020. This study also found a negative effect of GPRs on trade flows between the countries with some countries being more vulnerable than others. Moreover, Kim & Jin (2023) determined the effect of GPRs on South Korea’s international trade for the period from 1991 to 2020. This study documented that an increase in geopolitical tension results in a decrease in South Korea’s international trade. Additionally, the adverse effects of GPRs differ among trading partners, primarily depending on the relative importance of each country. Furthermore, Leitão (2023) explored the effect of country risks on Portuguese exports to 11 main trading partners from 1990 to 2021. The main finding of the study is that the partner country risk is negatively associated with Portuguese exports, implying that countries with lower risks experience reduced trade costs, which enhances competitiveness among countries.

Recently, some studies have investigated the effect of GPRs on foreign trade of China, the second biggest economy in the world. Specifically, Wang et al. (2021) examined the effect of country risk on foreign trade for the Belt and Road (BRI) countries for the period from 2003 to 2018. This study documented that a decrease in country risk results in an increase in bilateral trades between China and these countries. Similarly, Wang et al. (2024) determined the effect of GPRs on China’s bilateral trade flows with its key trading partners, considering the moderating impact of the BRI for the period from 2014 to 2022. The results confirmed that the GPRs has negative effects on China’s bilateral trade flows. However, the effects are difference between BRI and non-BRI countries. In fact, the negative effect generally holds to non-BRI economies while China’s economic ties with BRI countries tend to strengthen in the face of rising GPRs. In addition, Liu et al. (2024) examined the effect of GPRs on China’s exports and its specific internal mechanisms during the period from 2003 to 2021. The study reported that GPRs have a significantly negative effect on exports of China. Especially, the researchers found that China’s outward foreign direct investment plays a crucial role in alleviating the negative impact of GPRs on the exports. In addition, the findings confirmed that GPRs have a more pronounced effect on China’s exports in non-BRI economies compared to BRI members. Moreover, Liu & Fu (2024) explored the effect of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports from 1995 to 2020. The empirical results show that China’s agricultural exports decline when its trading partners face GPRs and the agricultural land of trading partners plays a key role in reducing the negative impact of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports. Similar to the findings of Liu et al. (2024), this study confirmed the effect of GPRs on China’s agricultural exports is stronger in non-BRI countries than BRI economies.

Additionally, other studies have examined the effect of GPRs on energy trade. Li et al. (2021) discovered the effect of GPRs on energy trade of 17 emerging economies during the period from 2000 to 2020. Based on the empirical evidence, the authors asserted that GPRs have a significantly negative effect on energy trade, with the effect on exports being more pronounced than on imports. Recently, Zehri et al. (2025) explored how GPRs impact energy trade differently in 55 emerging and advanced economies for the period from 1990 to 2023. The study documented that GPRs generally hinder energy trade with long-term effects outweighing temporary shocks. However, emerging economies tend to be more vulnerable to GPRs, experiencing greater disruptions in energy trade compared to their advanced counterparts due to their significant dependence on energy exports and weaker institutional capacity.

From a different perspective, Atacan & Açık (2023) examined the relationship between GPRs and international trade proxied by container volumes. Using a sample of 15 countries for the period from 2000 to 2020, the authors found that positive shocks in GPRs lead to negative shocks in container volumes. Using data from 119 countries for the period from 1985 to 2022, Yan & Piao (2025) investigated the effect of GPRs on national trade openness. The empirical findings revealed that GPRs have a significantly negative effect on trade openness. In addition, enhanced fiscal freedom and stable fiscal conditions are shown to effectively mitigate this negative effect, emphasizing the importance of strong fiscal institutions in bolstering national resilience to external shocks. Moreover, the results indicated that the detrimental impact of GPRs is more significant in countries with lower government integrity and weaker monetary freedom.

In summary, the reviewed literature generally supports the notion that GPRs adversely affect international trade. Key findings indicated that increased geopolitical tensions lead to disruptions in trade flows, altering established trade patterns. However, there are discrepancies regarding the extent of these effects across different countries and sectors. Vietnam is a highly export-driven economy, with key export items including electronics, machinery, textiles, and agricultural products. Its major trading partners—such as the United States, China, and South Korea–account for a substantial share of export revenue, exposing the country to geopolitical tensions among global powers. Additionally, the dominance of foreign-invested enterprises in export production highlights Vietnam’s deep integration into global supply chains, making it particularly sensitive to external shocks. These characteristics underscore the relevance of examining how geopolitical risks asymmetrically impact on Vietnam’s export performance. Based on the reviewed evidence, it is hypothesized that the GPRs have a negative effect on Vietnam’s export.

3. Data and Research Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

The data employed in this study consist of monthly series for the GPR Index, Vietnam’s exports, real exchange rate (RER), and industrial production index (IPI) covering the period from January 2010 to December 2024. The data are obtained from various reliable sources, namely the Geopolitical Risk Index Report, the General Statistics Office (GSO) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It is noted that this study utilizes the geopolitical risk index that was developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Specifically, the data sources are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Research Methodology

To investigate the asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s export, the following baseline regression model is employed:

where:

- -

LNEX is the natural logarithm of Vietnam’s exports;

- -

is the natural logarithm of positive change of GPR index;

- -

is the natural logarithm of negative change of GPR index;

- -

LNRER is the natural logarithm of real exchange rate of USD/VND. The real exchange rate (RER) is computed by equation (2) as follow:

NER is the nominal exchange rate of USD/VND.

is the Vietnam consumer price index.

is the United States consumer price index.

LNIPI is the natural logarithm of Vietnam’s industrial production index.

To examine the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s TB, this study employs the Non-linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) bounds testing model proposed by Shin et al. (2014), which extends the ARDL model developed by Pesaran et al. (2001). In this model, the GPR is decomposed in positive and negative partial sum series. This study employs the NARDL model because this model has some main advantages compared to other alternative cointegration methods. Firstly, the NARDL does not require all variables in a model to have the same order of integration. Instead, it only requires that the integration order of all variables in the model does not exceed 1. Secondly, the NARDL test is relatively more efficient and reliable than other approaches in the case of small sample sizes. Finally, a key advantage of the model compared to other cointegration methods is that it allows for the derivation of an error correction model (ECM) from the NARDL model, enabling the simultaneous estimation of both short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of independent variables on the dependent variable. As mentioned previously, the NARDL bounds test for cointegration requires all studied variables in the model to be either I(0) or I(1). Therefore, a unit root test should be performed prior to conducting the NARDL bounds test. In this study, the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test is utilized to determine the stationarity of the variables in the model.

Before estimating the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of the GPRs on the TB, a cointegration test should be conducted as a required condition. In this study, the NARDL bound test for cointegration between variables in the model is represented by the following equation:

where:

- -

is the first difference of the variables;

- -

k1, k2, k3, k4, k5 represent the optimal number of lags for the variables in the model, as determined by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) technique.

The null hypothesis of the bound test estimated by equation (3) is no co-integration in the long-run between variables. If the null hypothesis is rejected, it can be concluded that a long-term relationship exists between the variables in the model. In this case, the short-run and long-run asymmetric effects of the GPR on the TB are estimated by equation (4) and (5), respectively.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Based on the data collected, descriptive statistics for the studied variables during the period from January 2010 to December 2024 are computed and summarized in

Table 2.

Table 2 indicates that the average of Vietnam’s exports during the sample period is USD 18,765.5 million, with a range from USD 3,717.3 million to USD 38,085.6 million. In addition, it is shown in

Table 2 that the GPR Index had highly fluctuated during the sample period. Specifically, the average of GPR Index is 91.5 points while the lowest score and highest score are 28.5 and 251.0 points respectively. Moreover, it is found in

Table 2 that the mean of RER (USD/VND) is 28,951. The RER has increased significantly for the studied period, meaning that the Vietnamese Dong had depreciated over the period. Specifically, the lowest rate is 17,322, whereas the highest rate is 33,465. Besides,

Table 2 reveals that the average of IPI Index for the period from January 2010 to December 2024 is 94.3 points, ranging from 57.0 points to 124.7 points.

4.2. Results of the ADF Test

As previously noted, this study utilizes the ADF test to determine whether all variables in the model meet the stationary condition required for the ARDL bound test. The test is conducted for both cases of constant only and constant with time trend. The results presented in

Table 3 confirm that the LNEX,

,

and LNRER series are I(1) whereas the LNIPI series is I(0). These findings indicate that all the variables meet the requirements for the ARDL bound test.

Table 2.

Results of the ADF test.

Table 2.

Results of the ADF test.

| Variables |

Without trend |

With trend |

| LNEX |

|

|

| Level |

-3.36**

|

-2.82 |

| First difference |

-4.69***

|

-10.88***

|

|

|

|

| Level |

0.62 |

-3.43 |

| First difference |

-14.49***

|

-14.51***

|

|

|

|

| Level |

0.54 |

-3.01 |

| First difference |

-16.85***

|

-16.84***

|

| LNRER |

|

|

| Level |

-4.51***

|

-3.05 |

| First difference |

-8.21***

|

-9.02***

|

| LNIPI |

|

|

| Level |

-5.07***

|

-5.09***

|

4.3. ARDL Bound Test for Cointegration

This study employs the bounds test developed by Pesaran et al. (2001) to determine the long-term relationship among the variables. Based on the Akaike Information Criterion, the optimal model for the bounds test is ARDL (3,0,0,3,4). The results of the bounds test summarized in

Table 3 indicate that the null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables is rejected at the one percent significance level. This evidence confirms the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between Vietnam’s exports and the independent variables.

4.4. Short-Term and Long-Term Influences of GPRs on Vietnam’s Exports

Given the evidence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between the Vietnam’s exports and the independent variables, the short-term and long-term asymmetric effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports are estimated by using the NARDL (3,0,0,3,4) model. The empirical findings shown in

Table 4 reveal that in the short-term, the GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports, suggesting that positive and negative changes in the GPRs have a distinct effect on Vietnam’s exports. The negative changes in the GPRs have a significantly negative effect on the exports at the ten percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in negative changes in the GPRs immediately leads to a 0.0234 percent decrease in Vietnam’s exports. However, the positive changes in the GPRs have no significant impact on the exports. In addition, the results shown in

Table 4 indicate that the RER has a significantly positive effect on the exports at the five percent level for the one-month lag, suggesting that the depreciation of VND (Vietnam Dong) boosts Vietnam’s exports. Specifically, a one percent increase in RER in previous month leads to a 2.3197 percent increase in the exports in current month. Moreover, it is observed from

Table 4 that the IPI has a significantly positive effect on the exports in the short-term at the five percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in the IPI is contemporaneously associated with a 1.17981% increase in the exports leads to 0.1092 percent increase in the exports for the three-month lag. Furthermore, the coefficient of error correction terms is -0.3482 and statistically significant at the one percent level, suggesting that 34.82 percent of the divergence from the long-run equilibrium caused by a shock this month will be corrected and adjusted back toward equilibrium in the following month.

Similarly, in the long-term, the estimated results presented in Panel B of

Table 4 indicate that negative changes in the GPRs have a significantly negative effect on Vietnam’s exports at the ten percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in the negative changes in the GPRs is associated with 0.0672% decrease in the exports. However, the results confirm that in the long-term, the positive changes in the GPRs have no impact on the exports. Besides, the empirical findings reveal that, in the long-term, RER has a significantly positive impact on the exports at the one percent level. Specifically, a one percent increase in RER is associated with a 0.5748 percent increase in Vietnam’s exports. However, we find no evidence of a long-term effect of IPI on the exports.

Overall, this study finds that the GPRs have asymmetric effects on Vietnam’s exports both in the short-term and long-term. Specifically, negative changes in the GPRs have a significantly negative effect on the exports while positive changes in the GPRs have no significantly impact on the exports. This evidence partially aligns with the previous findings of Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018), Gupta et al. (2018), Goswami & Panthamit (2020), Singh et al. (2023), Kim & Jin (2023), Leitão (2023), Wang et al. (2024), Liu et al. (2024), Liu & Fu (2024) that GPR has a significantly negative impact on trade flows between countries. However, these studies are based the assumption that the effect of GPR is symmetric, meaning that positive and negative changes in GPR have the same effect on the trade flows. Contrary to these findings, our findings confirm that only negative changes in the GPR negatively impact on Vietnam’s exports while positive changes in the GPR have no impact on the exports. The asymmetric effects of GPR on Vietnam’s exports could be explained by several reasons. First, increased negative changes in GPR can significantly disrupt supply chains and increase trade costs, leading to a decline in exports. This is especially relevant for Vietnam that is heavily dependent on specific trade partners. In addition, an increase in negative changes in GPR can lead to tariffs and other trade barriers, which negatively affects export volumes by driving up the prices of goods. Although positive changes in GPRs can create favorable conditions for boosting exports, their actual effects on Vietnam's exports are less significant compared to the negative impact of adverse events due to various factors. Specifically, positive changes in GPRs could not lead to immediate increases in exports due to the time required for businesses to adjust their strategies, expand operations, or explore new markets. Besides, since Vietnam’s exports are predominantly agricultural and labor-intensive products, even with positive changes in GPRs, the potential for increasing exports is also limited by production capacity.

4.5. Diagnostic and Structural Stability Tests

The results of Breusch-Godfrey test shown in

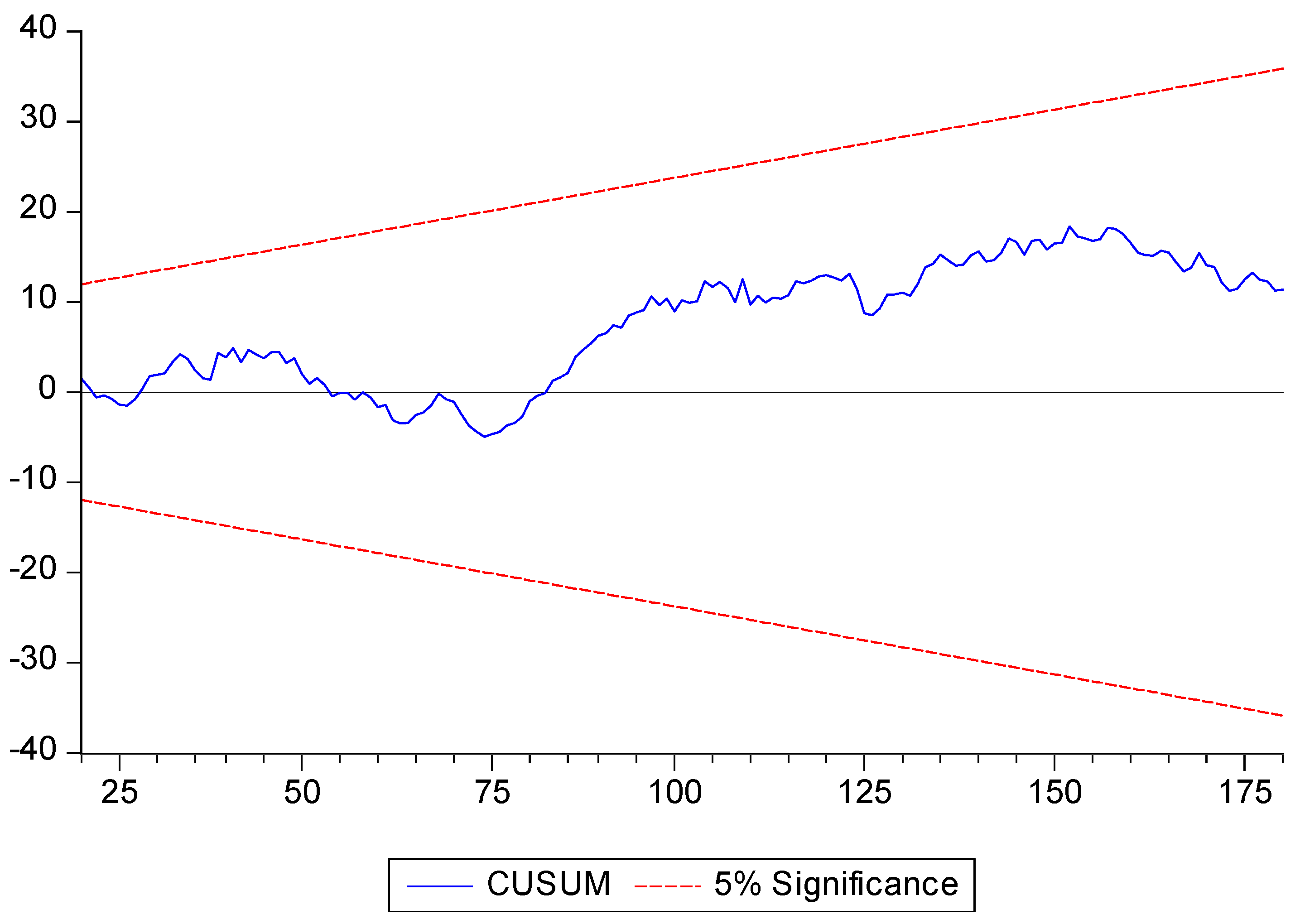

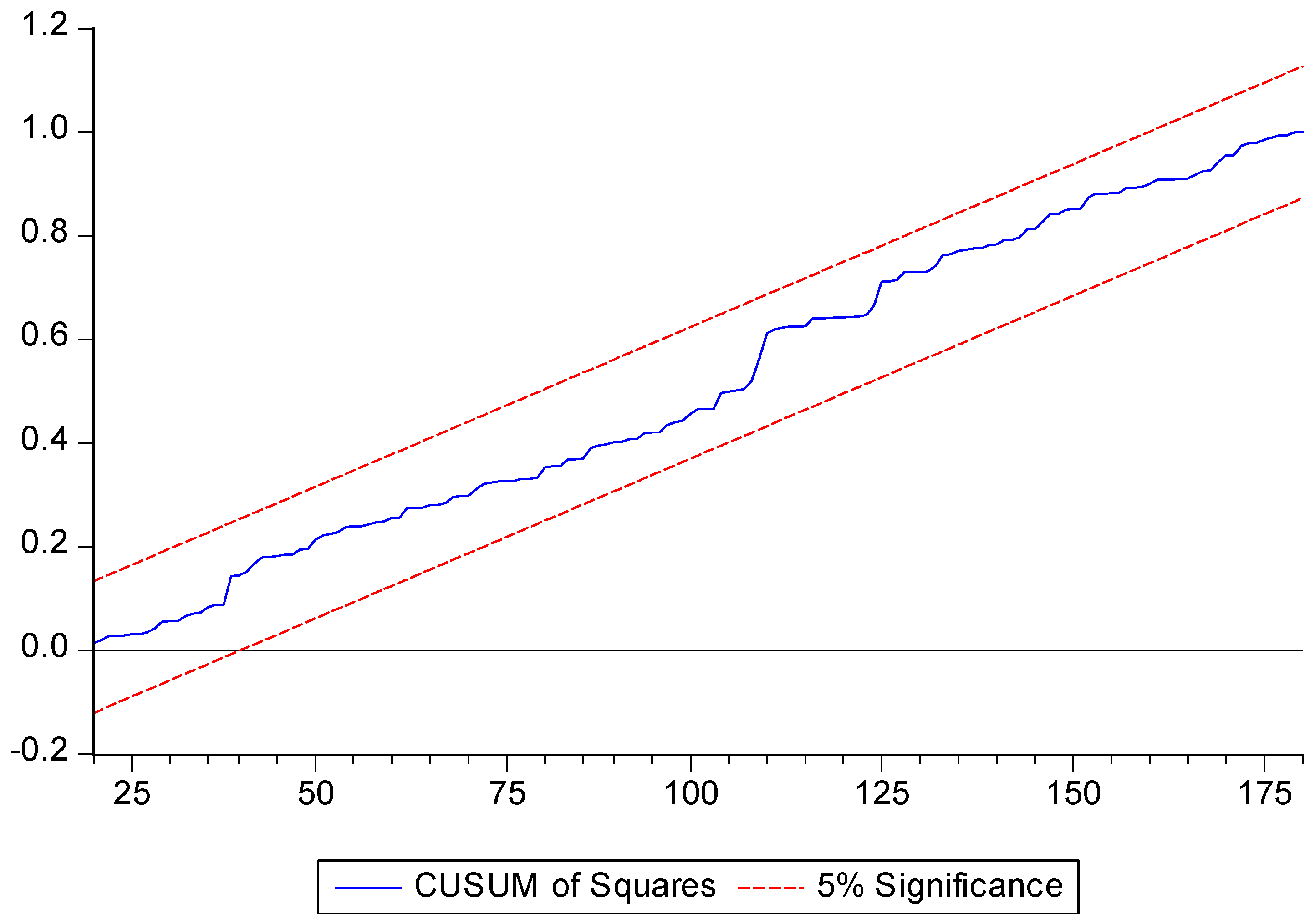

Table 5 reveal that the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation in the model cannot be rejected at the significance level of 5%, suggesting that there is no autocorrelation among the residuals. In addition, the results of the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test confirm that the residuals of the model are homoscedastic. Moreover,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show that the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots remain within the critical bounds at the five percent significance level. These results ensure the reliability and validity of the estimated results.

5. Conclusions

While most studies have examined the systematic effect of GPR on trade flows between countries, this study investigates asymmetrically short-term and long-term effects of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. Using the NARDL bounds testing model, this study found that in both the short-term and the long-term, the GPRs have asymmetric effects on the exports. Specifically, the negative changes in the GPRs have a significantly negative effect on the exports while the positive changes in the GPRs have no significant impact on the exports. These findings are partially consistent with the findings of Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018), Gupta et al. (2018), Goswami & Panthamit (2020), Singh et al. (2023), Kim & Jin (2023), Leitão (2023), Wang et al. (2024), Liu et al. (2024), Liu & Fu (2024) that GPR has symmetrically adverse effects on trade flows between countries. Moreover, the findings confirmed that, real exchange rate has a significantly positive effect on the exports, meaning that the depreciation of Vietnam Dong enhances Vietnam’s exports.

Based on the empirical findings, several policy implications can be suggested for Vietnamese policymakers to mitigate the adverse effect of GPRs on the exports. First, the government should promote the signed free trade agreements with countries so that businesses can take advantage of opportunities to mitigate the negative impacts of GPRs. In addition, the government should actively pursue and negotiate new free trade agreements to expand market access and reduce the negative effect of GPRs on Vietnam’s exports. Second, the government should enhance diplomatic ties with a diverse range of countries to diversify markets for exporters. This can help secure stable export markets and mitigate risks. Finally, the government should establish robust monitoring and early warning systems to regularly assess the GPRs in trading partner countries. This system can facilitate timely adjustments to trade strategies.

While this study has enriched the literature on the impact of GPRs on exports in a transition economy, it still has several limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. First, the effect of GPRs can vary significantly across different sectors, but this study does not explore these sector-specific variations, which could offer more nuanced insights. Second, the study does not account for other external factors, such as global economic conditions or pandemics, that could interact with GPRs and influence the exports. These limitations await further studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.T. and D.T.N.; methodology, L.D.T. and N.T.N.; software, L.D.T. and N.T.N.; validation, D.T.N.; formal analysis, L.D.T. and D.T.N.; investigation, N.T.N.; resources, N.T.N.; data curation, D.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.T.; writing—review and editing, D.T.N. and N.T.N.; visualization, L.D.T.; project administration, L.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Atacan, C., & Açık, A. (2023). Impact of geopolitical risk on international trade: Evidence from container throughputs. Transactions on Maritime Science, 12(2), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S., Sandler, T., & Younas, J. (2018). Trade and terrorism: A disaggregated approach. Journal of Peace Research, 55(5), 656-670. [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D., & Iacoviello, M. (2022). Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1194-1225. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, G. G., & Panthamit, N. (2020). Does political risk lower bilateral trade flow? A gravity panel framework for Thailand vis-à-vis her trading partners. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(2), 600-620. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Gozgor, G., Kaya, H., & Demir, E. (2019). Effects of geopolitical risks on trade flows: evidence from the gravity model. Eurasian Economic Review, 9(4), 515–530. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Y., & Jin, H. (2023). Does geopolitical risk affect bilateral trade? Evidence from South Korea. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 29(4), 1834–1853. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, N. C. (2023). The impact of geopolitical risk on Portuguese exports. Economies, 11 (12), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Yang, C., Li, Z., & Failler, P. (2021). Does geopolitics have an impact on energy trade? Empirical research on emerging countries. Sustainability, 13(9), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Fu, Q., Ma, Q., & Ren, X. (2024). Does geopolitical risk affect exports? Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 81, 1558–1569. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., & Fu, Q. (2024). Does geopolitical risk affect agricultural exports? Chinese evidence from the perspective of agricultural land. Land, 13(3), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16, 289–326. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y., Yu, B., & Greenwood-Nimmo, M. (2014). Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric methods and applications; Sickles, R. C., & Horrace, W. C. Eds; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 281-314.

- Singh, V., Correa da Cunha, H., & Mangal, S. (2023). Do geopolitical risks impact trade patterns in Latin America? Defence and Peace Economics, 35(8), 1102–1119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zong, Y., Dan, Y., & Jiang, S.-J. (2021). Country risk and international trade: Evidence from the China-B&R countries. Applied Economics Letters, 28(20), 1784–1788. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Yao, X., & Kim, C. Y. (2024). Is a friend in need a friend indeed? Geopolitical risk, international trade of China, and Belt & Road Initiative. Applied Economics Letters, 32(7), 1021–1028. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X., & Piao, L. (2025). The effect of global geopolitical risks on trade openness. International Review of Economics and Finance, 102, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zehri, C., Alsadan, A., & Ben Ammar, L. S. (2025). Asymmetric impacts of geopolitical risks on energy Trade: Divergent vulnerabilities in emerging vs. advanced economies. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 32, e00427. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).