1. Introduction

The management of regional lymph nodes in patients with cutaneous melanoma has undergone a profound transformation over the past several decades. This evolution reflects significant advances in surgical techniques, diagnostic modalities, and a growing understanding of melanoma biology and its metastatic behavior.

Historically, complete lymphadenectomy was considered the standard of care for patients presenting with clinically palpable lymphadenopathy or following the identification of a positive sentinel lymph node (SLN). This approach was grounded in the oncologic principle that early removal of regional nodal metastases could potentially interrupt disease progression, thereby improving disease-specific survival and overall outcomes.

However, this paradigm began to shift with the emergence of large-scale prospective randomized controlled trials, most notably the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (MSLT-II) [

1] and the DeCOG-SLT trial [

2]. The accumulated evidence from these studies demonstrated that immediate complete lymph node dissection (CLND) did not confer a statistically significant advantage in melanoma-specific survival compared to observation alone, although it did improve regional disease control.

Moreover, CLND was associated with a substantially increased risk of surgical morbidity, including lymphedema, wound complications, and sensory neuropathies—adverse effects that can significantly impair patients’ quality of life. These findings have prompted a major paradigm shift in clinical practice, favoring more individualized and risk-adapted strategies over routine and universal lymphadenectomy.

This narrative review aims to critically examine this transition, synthesizing the latest clinical trial data and evolving surgical principles to inform a more selective and evidence-based approach to the management of regional lymph nodes in cutaneous melanoma.

2. Materials and Methods

To support this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed using three major biomedical databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search focused on publications from the past 15 years, reflecting the most current evidence and evolving perspectives in the field.

The strategy incorporated a targeted set of keywords, including “cutaneous melanoma,” “lymphadenectomy,” “sentinel lymph node biopsy,” “selective lymphadenectomy,” and “regional nodal management.” These terms were selected to capture the breadth of research related to surgical approaches and nodal evaluation in melanoma.

Priority was given to high-quality sources, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and updated clinical practice guidelines. Articles were screened for relevance based on their study design, the characteristics of the patient population, and clinical endpoints pertaining to survival, recurrence, and surgical morbidity.

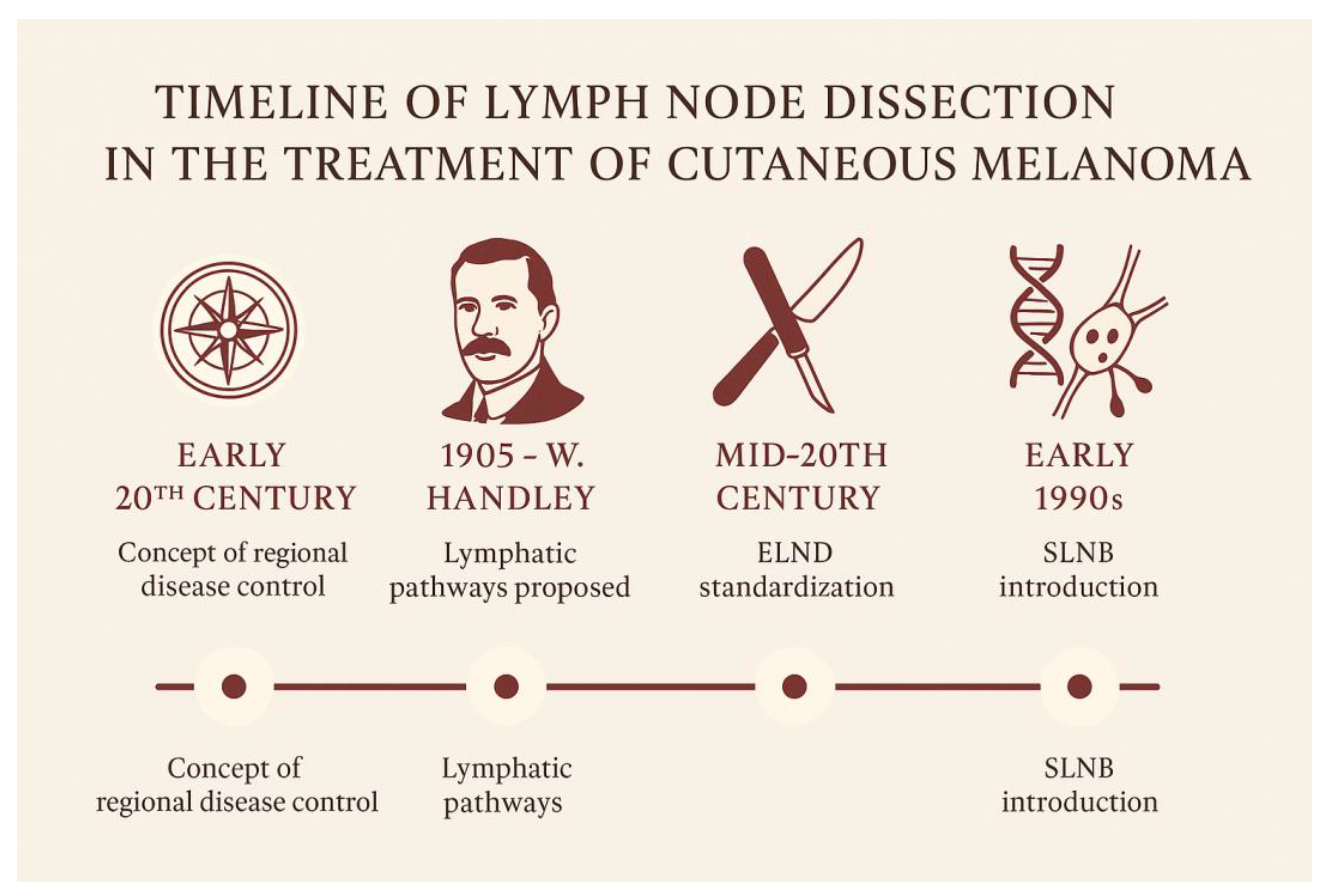

3. From Handley to Morton: The Development of Lymphatic Surgery in Melanoma

The origins of lymph node dissection in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma can be traced back to the early 20th century, rooted in the prevailing concept of regional disease control. Among the earliest and most influential figures in this domain was William Heneage Ogilvie Handley, a British surgeon and pathologist. In 1905, Handley published a landmark monograph in which he proposed a hypothesis on the lymphogenous spread of melanoma [

3].

Through meticulous anatomical dissections and the innovative use of mercury injections into lymphatic vessels, Handley demonstrated a centrifugal pattern of lymphatic drainage from cutaneous melanomas to regional nodal basins. He theorized that tumor cells disseminated along these pathways, forming microscopic satellite metastases and eventually colonizing regional lymph nodes. Based on these observations, he advocated for wide local excision of the primary tumor in continuity with the draining lymphatic basin—even in the absence of clinically palpable adenopathy. This procedure, later termed elective lymph node dissection (ELND), was conceived as both a staging tool and a potentially curative intervention.

Throughout the early and mid-20th century, Handley’s principles were widely embraced by surgical oncologists. ELND became increasingly standardized, particularly in patients with thicker primary melanomas or lesions located in anatomically high-risk regions such as the head and neck or extremities. Surgeons like Herbert Snow [

4] and Alexander Brunschwig [

5] further advanced this surgical doctrine, promoting radical lymphadenectomy as a strategy to interrupt regional spread and improve survival outcomes. These extensive dissections reflected the aggressive surgical philosophy of the era.

Yet despite its widespread adoption, the clinical utility of ELND remained a subject of ongoing debate. The absence of randomized controlled data and the inability to reliably identify patients harboring occult nodal metastases raised concerns about overtreatment. Pathologic examination of dissected nodal basins revealed that a significant proportion of patients undergoing ELND had no histologic evidence of nodal involvement, suggesting that many were exposed to unnecessary surgical risk.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the landscape began to shift. Advances in histopathologic techniques and a more nuanced understanding of melanoma biology prompted clinicians and researchers to seek less invasive methods for staging the regional nodal basin—methods that could spare patients from the morbidity associated with extensive dissections. This search culminated in the development of the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) technique, which would prove to be a transformative milestone in melanoma surgery.

Pioneered by Donald L. Morton [

6] and colleagues in the early 1990s, SLNB was initially validated in melanoma and later extended to other solid tumors, including breast cancer. The technique was based on the principle of intraoperative lymphatic mapping, allowing surgeons to identify and analyze the initial lymph node(s) receiving drainage from the primary tumor. SLNB offered a minimally invasive method for regional staging, preserving oncologic accuracy while significantly reducing the morbidity associated with ELND.

The timeline of the history of lymph node dissection is illustrated in

Figure 1.

4. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy vs Completion Lymph Node Dissection: Evidence from Clinical Trials

In the past two decades, the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) versus completion lymph node dissection (CLND) in the management of cutaneous melanoma has been rigorously evaluated through several randomized clinical trials. These studies have reshaped surgical decision-making, emphasizing the balance between oncologic benefit and procedural morbidity.

One of the earliest and most influential investigations was the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial I (MSLT-I)

[7]. This landmark study compared two approaches: wide excision plus SLNB (with immediate CLND if the SLNB was positive) versus wide excision followed by nodal observation, with delayed therapeutic lymphadenectomy in the event of nodal recurrence. Although SLNB did not demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in overall survival compared to nodal observation, it did yield a notable advantage in disease-free survival. Importantly, SLNB provided critical prognostic information, particularly for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas (1.2–3.5 mm), by enabling early detection of micrometastases and guiding subsequent therapeutic decisions. The procedure also contributed to improved regional disease control.

Building on these findings, the MSLT-II trial

[1] addressed a pivotal clinical question: should patients with a positive sentinel lymph node undergo immediate CLND, or can they be safely managed with active surveillance using regular nodal ultrasound? Enrolling over 1900 patients, the study found no statistically significant difference in melanoma-specific survival between the immediate CLND group and the observation group. However, immediate CLND did reduce the risk of regional nodal recurrence and allowed for more accurate staging, identifying additional positive non-sentinel nodes in approximately 12% of patients. Despite these benefits, the procedure was associated with increased surgical morbidity, including lymphedema, wound infections, and nerve injuries [

8].

These results were further supported by the DeCOG-SLT trial

[2], which focused specifically on patients with micrometastatic involvement of the sentinel node. The trial confirmed that omitting CLND did not negatively impact distant metastasis-free survival or overall survival, reinforcing observation as a safe and effective strategy in appropriately selected patients. Moreover, the DeCOG-SLT trial highlighted the importance of individualized patient selection, particularly the assessment of tumor burden within the sentinel node, as a key factor in guiding management decisions [

2].

Together, these trials have contributed to a more nuanced understanding of nodal management in melanoma, shifting the emphasis from routine completion dissection to selective, evidence-based strategies that prioritize both oncologic outcomes and patient quality of life.

5. Complications Associated with Lymphadenectomy

Completion lymph node dissection (CLND), while historically considered a standard approach for managing nodal metastases in melanoma, carries a significant burden of postoperative morbidity. These complications not only affect short-term recovery but also have lasting impacts on patient quality of life.

Among the most frequent and debilitating complications is lymphedema, which can persist chronically and severely impair limb function. Reported incidence ranges from 20% to 50%, influenced by factors such as the anatomical site of dissection, extent of nodal clearance, patient obesity, and the use of adjuvant radiation therapy [

9,

10]. Notably, inguinal lymphadenectomy is associated with a higher risk of lymphedema compared to axillary dissection, due to differences in lymphatic architecture and anatomical complexity [

11]. Chronic lymphedema predisposes patients to recurrent cellulitis and functional limitations, making it one of the most feared long-term outcomes of CLND.

Wound complications, including infection, necrosis, and delayed healing, affect approximately 10–30% of patients undergoing CLND [

7,

12]. The Groin Lymphadenectomy in Melanoma (GOLM) study [

13] identified several independent predictors of wound morbidity, such as high body mass index, smoking status, and extensive nodal dissection. These factors underscore the importance of preoperative risk stratification and perioperative optimization.

Seroma formation is another common early postoperative issue, occurring in 20–40% of cases. While often benign, seromas may require repeated aspirations and can increase the risk of secondary infection [

14].

Nerve injury is a particularly concerning complication, especially in anatomically complex regions. In inguinal dissections, the femoral, obturator, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves are vulnerable, while axillary dissections may affect the long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves. These injuries can result in sensory deficits, neuropathic pain, and motor weakness, with long-term sequelae documented in up to 15% of patients [

15].

The cumulative morbidity associated with CLND was a driving force behind the design of pivotal trials such as MSLT-II [

1] and DeCOG-SLT [

2]. These studies demonstrated that immediate CLND following a positive SLNB did not improve melanoma-specific survival but significantly increased complication rates. In the MSLT-II trial, the incidence of lymphedema was markedly higher in the CLND group (24.1%) compared to the observation arm (6.3%) [

1]. Similarly, the DeCOG-SLT trial reported a 19% overall complication rate in patients undergoing CLND [

2].

These findings have led to a paradigm shift in clinical practice, favoring nodal observation and ultrasound surveillance in selected patients. This approach minimizes unnecessary surgical morbidity while maintaining oncologic safety, reflecting a more patient-centered and evidence-based strategy in melanoma management.

6. The Evolving Role of Lymph Node Dissection in the Era of Systemic Therapy for Melanoma

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies has dramatically transformed the therapeutic landscape of stage III cutaneous melanoma, reshaping the role of lymph node dissection within a broader, multidisciplinary framework. Once considered a cornerstone of regional disease control, completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is now increasingly viewed through the lens of systemic efficacy and individualized risk stratification.

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that adjuvant systemic therapies significantly improve both relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with resected stage III melanoma. The KEYNOTE-054 trial [

16] showed that pembrolizumab reduced the risk of recurrence by 43% compared to placebo (hazard ratio 0.57; p<0.001), with a 3-year RFS of 63.7% versus 44.1%. Similarly, the CheckMate-238 trial [

17] reported superior RFS with nivolumab compared to ipilimumab (58% vs. 45% at 3 years; HR 0.65; p<0.001). For patients harboring BRAF mutations, the COMBI-AD trial [

18] demonstrated that the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib improved 3-year RFS to 58%, compared to 39% with placebo.

These findings underscore the critical importance of accurate nodal staging—primarily achieved through sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)—in identifying candidates for adjuvant systemic therapy. As a result, CLND is no longer routinely performed in SLN-positive patients, given the lack of survival benefit and the increased risk of surgical morbidity.

Emerging evidence from neoadjuvant trials further challenges the traditional indications for lymphadenectomy. The OpACIN-neo [

19] and PRADO [

20] trials investigated neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in patients with stage III melanoma. In the PRADO study, 61% of patients achieved a major pathologic response (defined as ≤10% viable tumor) following neoadjuvant treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab. In these responders, therapeutic lymph node dissection was omitted, and no excess recurrences were observed at 2-year follow-up. These results suggest that pathologic response may serve as a reliable biomarker for surgical de-escalation, paving the way for more personalized and less invasive treatment strategies.

In light of these developments, the role of lymph node dissection has become increasingly selective and context-dependent. While CLND remains appropriate in cases of gross nodal disease, progression during systemic therapy, or symptomatic lymphadenopathy, it is no longer indicated as a default intervention following a positive SLNB. Instead, surgical management is now tailored to complement systemic approaches, reflecting a paradigm shift toward precision oncology in melanoma care.

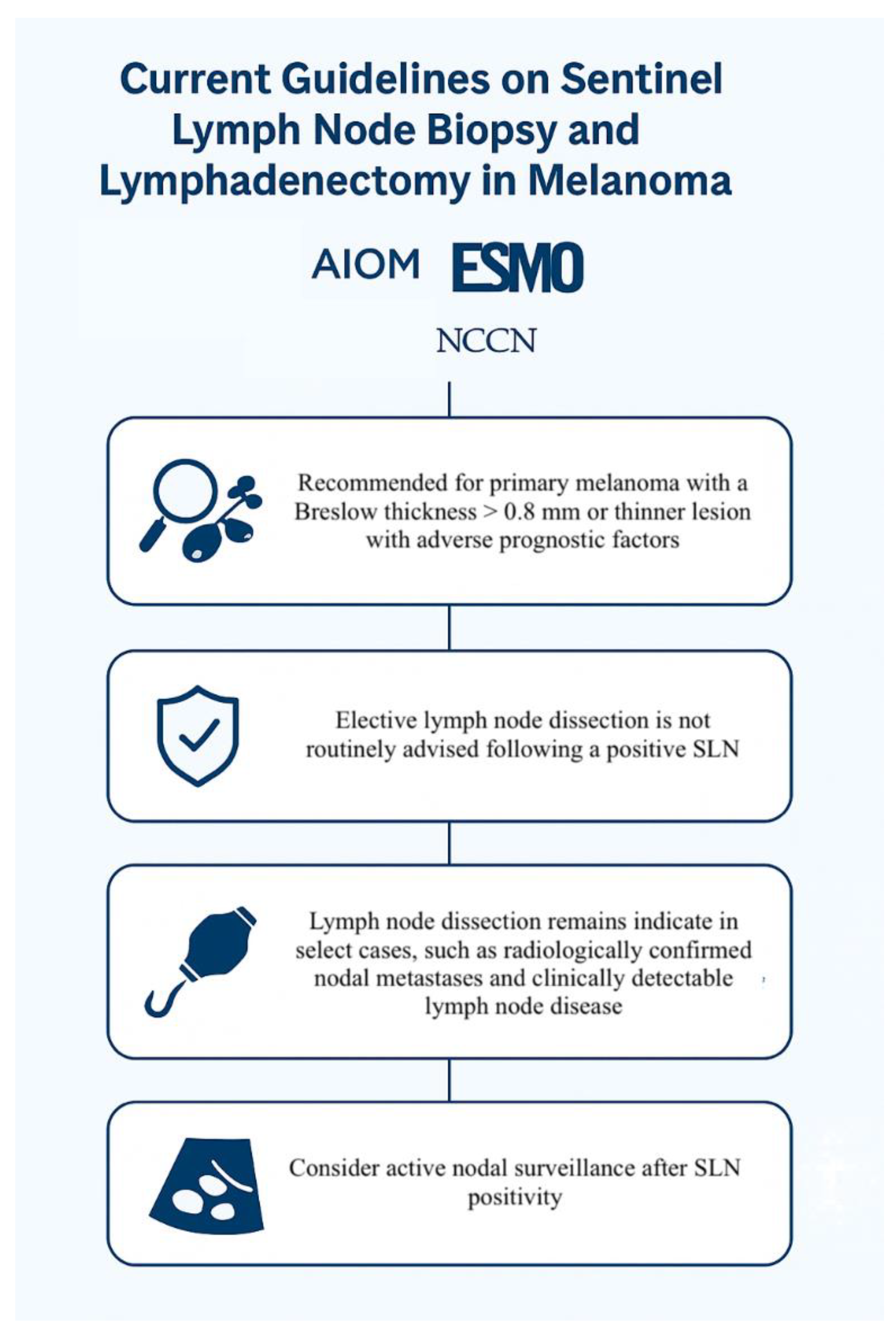

7. Current Guidelines on Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Lymphadenectomy in Melanoma: AIOM, ESMO, and NCCN Perspectives

Contemporary clinical guidelines from leading oncology societies—including the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM), the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)—reflect a unified shift in the management of regional lymph nodes in melanoma, emphasizing precision staging and minimizing unnecessary surgical morbidity.

All three organizations endorse sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as the standard of care for staging clinically node-negative patients with intermediate- or high-risk primary cutaneous melanoma. Specifically, SLNB is recommended for tumors with a Breslow thickness ≥ 0.8 mm, or for thinner lesions exhibiting adverse features such as ulceration or high mitotic rate.

In contrast, elective completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is no longer routinely advised following a positive SLNB. This recommendation is grounded in robust evidence from randomized trials (e.g., MSLT-II, DeCOG-SLT) demonstrating no melanoma-specific survival benefit and a higher rate of complications with immediate CLND. Instead, guidelines advocate for active nodal surveillance, typically via high-resolution ultrasound, reserving CLND for patients with clinically evident nodal disease, radiologically confirmed metastases, or high tumor burden within the sentinel node.

The AIOM guidelines emphasize the prognostic and therapeutic value of SLNB and discourage routine CLND in SLN-positive patients, aligning with international standards and the Italian National Health System’s evidence-based approach.

The ESMO guidelines similarly recommend SLNB for patients with AJCC stage pT1b or higher, and explicitly state that CLND should not be performed routinely after SLN positivity. They highlight the role of SLNB in identifying candidates for adjuvant systemic therapy and stress the importance of individualized decision-making, especially in patients eligible for neoadjuvant approaches.

The NCCN guidelines reinforce these principles, advising SLNB for patients with stage IB (T2a) or higher melanoma, and recommending observation over CLND in SLN-positive cases unless there is gross nodal disease or progression during systemic therapy. They also support the integration of SLNB findings into therapeutic planning, particularly for adjuvant immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

Collectively, these guidelines reflect a paradigm shift: lymph node surgery is no longer a default intervention but a selective tool, guided by tumor biology, imaging, and systemic treatment strategies. A flowchart summarizing these recommendations is presented in

Figure 2.

8. Current Guidelines on Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Lymphadenectomy in Melanoma: AIOM, ESMO, and NCCN Perspectives

Contemporary clinical guidelines from leading oncology societies—including the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM), the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)—reflect a unified shift in the management of regional lymph nodes in melanoma, emphasizing precision staging and minimizing unnecessary surgical morbidity.

All three organizations endorse sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as the standard of care for staging clinically node-negative patients with intermediate- or high-risk primary cutaneous melanoma. Specifically, SLNB is recommended for tumors with a Breslow thickness ≥ 0.8 mm, or for thinner lesions exhibiting adverse features such as ulceration or high mitotic rate.

In contrast, elective completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is no longer routinely advised following a positive SLNB. This recommendation is grounded in robust evidence from randomized trials (e.g., MSLT-II, DeCOG-SLT) demonstrating no melanoma-specific survival benefit and a higher rate of complications with immediate CLND. Instead, guidelines advocate for active nodal surveillance, typically via high-resolution ultrasound, reserving CLND for patients with clinically evident nodal disease, radiologically confirmed metastases, or high tumor burden within the sentinel node.

The AIOM guidelines emphasize the prognostic and therapeutic value of SLNB and discourage routine CLND in SLN-positive patients, aligning with international standards and the Italian National Health System’s evidence-based approach.

The ESMO guidelines similarly recommend SLNB for patients with AJCC stage pT1b or higher, and explicitly state that CLND should not be performed routinely after SLN positivity. They highlight the role of SLNB in identifying candidates for adjuvant systemic therapy and stress the importance of individualized decision-making, especially in patients eligible for neoadjuvant approaches.

The NCCN guidelines reinforce these principles, advising SLNB for patients with stage IB (T2a) or higher melanoma, and recommending observation over CLND in SLN-positive cases unless there is gross nodal disease or progression during systemic therapy. They also support the integration of SLNB findings into therapeutic planning, particularly for adjuvant immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

Collectively, these guidelines reflect a paradigm shift: lymph node surgery is no longer a default intervention but a selective tool, guided by tumor biology, imaging, and systemic treatment strategies. A flowchart summarizing these recommendations is presented in

Figure 2.

9. Conclusions

The paradigm of lymphadenectomy in cutaneous melanoma has undergone a profound transformation over recent decades. Once considered a routine step following sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is now reserved for select clinical scenarios. This shift reflects a growing body of evidence from randomized trials, real-world data, and evolving systemic therapies that have redefined the role of surgery in regional disease management.

Current international guidelines—including those from AIOM, ESMO, and NCCN—consistently advocate SLNB as the cornerstone for accurate staging in patients at intermediate or high risk of nodal involvement. CLND is no longer routinely recommended after SLN positivity, with active surveillance emerging as the preferred strategy in most cases. The integration of adjuvant and neoadjuvant systemic therapies has further reduced the need for extensive nodal surgery, especially in patients with favorable biological responses.

As melanoma treatment continues to evolve, the role of lymphadenectomy must be continually reassessed within a multidisciplinary framework. Ongoing research, including prospective trials and biomarker-driven strategies, will be essential to refine patient selection, optimize outcomes, and minimize morbidity. Ultimately, the future of nodal management in melanoma lies in personalized, evidence-based care—where surgical decisions are guided not by tradition, but by data, biology, and patient-centered priorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and R.C., methodology, M.M., investigation, M.M. and R.C.., writing—original draft preparation, M.M., R.C., C.B. and P.C.., writing—review and editing, M.M., R.C., S.G., B.C., V.D., D.C., A.P., F.F., M.A., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable because not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable because not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the finding of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT for the purposes of generating Figure 1 and Figure 2. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faries, M.B.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; Andtbacka, R.H.; Mozzillo, N.; Zager, J.S.; Jahkola, T.; Bowles, T.L.; Testori, A.; Beitsch, P.D.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Moncrieff, M.; Ingvar, C.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Sabel, M.S.; Levine, E.A.; Agnese, D.; Henderson, M.; Dummer, R.; Rossi, C.R.; Neves, R.I.; Trocha, S.D.; Wright, F.; Byrd, D.R.; Matter, M.; Hsueh, E.; MacKenzie-Ross, A.; Johnson, D.B.; Terheyden, P.; Berger, A.C.; Huston, T.L.; Wayne, J.D.; Smithers, B.M.; Neuman, H.B.; Schneebaum, S.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Ariyan, C.E.; Desai, D.C.; Jacobs, L.; McMasters, K.M.; Gesierich, A.; Hersey, P.; Bines, S.D.; Kane, J.M.; Barth, R.J.; McKinnon, G.; Farma, J.M.; Schultz, E.; Vidal-Sicart, S.; Hoefer, R.A.; Lewis, J.M.; Scheri, R.; Kelley, M.C.; Nieweg, O.E.; Noyes, R.D.; Hoon, D.S.B.; Wang, H.J.; Elashoff, D.A.; Elashoff, R.M. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, Hohenberger W, Brockmeyer NH, Berking C, Sunderkötter C, Kaatz M, Schatton K, Lehmann P, Vogt T, Ulrich J, Herbst R, Gehring W, Simon JC, Keim U, Verver D, Martus P, Garbe C. ; German Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group. Final Analysis of DeCOG-SLT Trial: No Survival Benefit for Complete Lymph Node Dissection in Patients With Melanoma With Positive Sentinel Node. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37, 3000–3008. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, W.S. (1907) The Pathology of Melanotic Growths in Relation to Their Operative Treatment. The Lancet, 1, 927-933, 996-1003.

- Snow, H.M. Melanotic cancerous disease. Lancet. 1982, 140, 869–922. [Google Scholar]

- BRUNSCHWIGA Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma; a one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer. 1948, 1, 177–83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.L.; Wen, D.R.; Wong, J.H.; et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992, 127, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.L.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; Mozzillo, N.; Nieweg, O.E.; Roses, D.F.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Karakousis, C.P.; Puleo, C.A.; Coventry, B.J.; Kashani-Sabet, M.; Smithers, B.M.; Paul, E.; Kraybill, W.G.; McKinnon, J.G.; Wang, H.J.; Elashoff, R.; Faries, M.B. ; MSLT Group. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014 Feb 13;370:599-609. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faries, M.B.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel-node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliadou, E.S.; Kakagia, D.; Lazaridis, L.; Skordoulis, G. Management of lower limb lymphedema following lymphadenectomy for melanoma. Journal of Vascular Nursing 2018, 36, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, R.C.; Grotz, T.E.; Ruiz, R.M.; Pockaj, B.A.; Vetto, J.T.; Ross, M.I. Regional lymph node basin recurrence and lymphedema following complete lymph node dissection for melanoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2016, 23, 2100–2106. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkley, K.S.; Shultz, D.B.; Chagpar, A.B.; Horowitz, D.P. Surgical complications and quality of life after inguinal versus axillary lymph node dissection for cutaneous melanoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2014, 21, 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A.; Hess, K.R.; Sondak, V.K.; Long, G.V.; Ross, M.I.; Thompson, J.F. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2017, 67, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, L.A.; Glass, G.E.; Lees, V.C.; Grobmyer, S.R. Groin lymphadenectomy in melanoma: a prospective multicenter study (GOLM study). Annals of Surgical Oncology 2019, 26, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A.M.; Morton, D.L.; Essner, R. Complications associated with groin dissection in melanoma patients. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2015, 22, 2891–2897. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, W.E.; Benda, R.K.; Vasiliou, V.; Carson, C. Nerve injury associated with axillary lymph node dissection for melanoma: incidence and clinical implications. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013, 107, 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont, A.M. M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Robert, C. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Mandala, M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.M.; Cowey, C.L.; Ascierto, P.A. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Hauschild, A.; Santinami, M.; Atkinson, V.; Mandalà, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Schadendorf, D. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozeman, E.A.; Menzies, A.M.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Dekker, T.; Krijgsman, O.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Blank, C.U. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN-neo): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology 2021, 22, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozeman, E.A.; Hoefsmit, E.P.; Reijers, I.L.M.; Sikorska, K.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Eriksson, H.; Blank, C.U. Survival and biomarker analyses from the PRADO trial of response-directed neoadjuvant therapy in stage III melanoma. Nature Medicine 2023, 29, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM). (2023). Linee guida melanoma cutaneo. Versione 4.0. https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/AIOM_LineeGuida_Melanoma_2023.pdf.

- European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). (2022). Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cutaneous-melanoma.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2024). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Melanoma. Version 2.2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/melanoma.pdf.

- Ferrari, M.; Rossi, G.; Bianchi, L. Minimally invasive approaches in melanoma surgery: impact on postoperative outcomes. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2019, 120, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, E.C.; Patel, K.M.; & Wong, S.L.; Wong, S. L. Comparison of morbidity between minimally invasive and open lymph node dissection for melanoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2020, 27, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, R.; Bianchi, G.; Conti, A. Challenges and learning curve in laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for melanoma. Surgical Endoscopy 2021, 35, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, E.; Garcia, A.F.; & Smith, D.L.; Smith, D. L. Robotic-assisted lymphadenectomy in melanoma: surgical technique and outcomes. Journal of Robotic Surgery 2020, 14, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, P.; Kowalski, M.; Nowak, J. Robotic lymph node dissection in melanoma: a systematic review of perioperative outcomes. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2022, 48, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, M.; Bruzzone, P.; Pinto, S.; Covarelli, P.; Boselli, C.; Popivanov, G.I.; Cirocchi, R. A Review of the Literature on Videoscopic and Robotic Inguinal-Iliac-Obturator Lymphadenectomy in Patients with Cutaneous Melanoma. J Clin Med. 2024 Dec 1;13:7305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).