1. Introduction

The surgical management of brain tumors has undergone significant technological evolution over the past decades, with the introduction of advanced visualization systems representing a major milestone in neurosurgical practice. Traditional operating microscopes, while providing excellent magnification and illumination, present inherent limitations including restricted positioning flexibility, ergonomic challenges for surgeons, and limited integration with modern digital workflows. The introduction of exoscope technology has addressed many of these limitations, offering high-definition 3D visualization on external monitors while maintaining the precision required for complex neurosurgical procedures[

1,

2]. Exoscopes provide several theoretical advantages over conventional microscopy, including improved ergonomics through natural head positioning, enhanced surgical team visualization, better integration with navigation systems, and the potential for superior depth perception through advanced 3D imaging [

3]. However, the clinical impact of these technological advantages on surgical outcomes, particularly in relation to the complexity of craniotomy approaches and the extent of tumor resection, remains incompletely characterized in the literature[

4].

The relationship between surgical complexity and clinical outcomes in brain tumor surgery is multifaceted. Craniotomy complexity is influenced by numerous factors including tumor location, size, proximity to eloquent brain areas, and the specific surgical approach required. Deep-seated lesions often necessitate more complex surgical corridors, potentially increasing operative time, technical difficulty, and the risk of complications. Conversely, superficial lesions may allow for more straightforward surgical approaches but can present their own challenges depending on their relationship to critical cortical areas. Gross total resection (GTR) remains the gold standard for most brain tumor pathologies, in particular for glioma surgery, with extensive literature demonstrating its correlation with improved survival outcomes and reduced recurrence rates [

5,

6]. However, achieving GTR must be balanced against the risk of neurological morbidity, particularly when tumors are located in eloquent brain regions or require complex surgical approaches. The extent of resection is influenced by multiple factors including tumor characteristics, surgical technique, visualization quality, and the surgeon's ability to distinguish tumor from normal brain tissue [

7].

The integration of advanced visualization technologies, such as exoscopes, into neurosurgical practice has the potential to influence both the feasibility of achieving GTR and the associated complication rates [

8]. Enhanced visualization may facilitate more precise tumor-brain interface identification, potentially improving resection rates while minimizing damage to surrounding normal tissue [

7]. However, the learning curve associated with new technology and potential changes in surgical workflow must also be considered when evaluating clinical outcomes [

4,

9]. Previous studies examining exoscope technology in neurosurgery have primarily focused on technical feasibility, surgeon satisfaction, and basic safety parameters [

10,

11]. Limited data exists regarding the relationship between exoscope use and surgical outcomes across different levels of craniotomy complexity. Understanding this relationship is crucial for optimizing patient selection, surgical planning, and outcome prediction in the era of advanced surgical visualization. The present study aims to evaluate the relationship between craniotomy complexity and surgical outcomes in brain tumor patients operated using exoscope technology. Specifically, we sought to determine whether craniotomy complexity correlates with extent of resection and complication rates, and whether outcomes differ between superficial and deep lesions when utilizing exoscope visualization. By systematically analyzing these relationships, we aim to provide evidence-based insights into the clinical utility of exoscope technology across the spectrum of neurosurgical complexity. Our hypothesis was that while deep lesions would require more complex craniotomy approaches, the advanced visualization capabilities of the exoscope would maintain consistent surgical outcomes across different complexity levels, potentially demonstrating the technology's ability to mitigate some of the traditional challenges associated with complex neurosurgical approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethical Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our Institution the and all the patients gave the informed consent for the procedure and for the treatment of the data. The statistical analysis used appropriate non-parametric statistical methods given the small sample size, ordinal complexity scores, and binary outcomes with a significance value stated at p<0.01 (Phyton, Python Software Foundation).

This retrospective study analyzed 26 consecutive patients who underwent brain tumor resection using exoscope technology (Orbeye Surgical Visualization System, Olympus Corporation) between January 2024 and January 2025 at Ospedale Papardo, Messina, Italy. Patients were categorized into two groups based on lesion depth and surgical complexity: superficial lesions (n=13, mean age 53.8±13.3 years) accessible through standard craniotomies (Pterional, parietal, frontal, temporo-parietal, frontoparietal, frontotemporal approach) and deep lesions (n=13, mean age 59.6±14.3 years) requiring violation of eloquent brain tissue and or/ deep anatomical structures (Precuneal interemipheric, suboccipital median, retrosigmoid, parietal, frontal interemispheric transcallosal, temporal, pterional, bicoronal, fronto-temporo-orbito-zigomatic (FTOZ) (

Table 1). Gender distribution was equal across groups (7 males, 6-7 females per group). In both groups, all the lesions suspected for glial lesions were administered 5-amino levulinic acid (5-ALA), 6 hours before the procedure: superficial lesion cases utilized 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) fluorescence guidance, while 53.8% of deep lesion cases was administered 5-ALA. The most common pathologies were glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) in both groups, with additional cases including meningiomas, cavernous angiomas, and metastases. Surgical outcomes were assessed by extent of resection (gross total resection (GTR )vs. subtotal resection (STR) and perioperative complications. Complications were categorized as lesion-related (directly attributable to tumor characteristics and location) or potentially technique-related (possibly influenced by exoscope limitations) (

Table 2).

3. Results

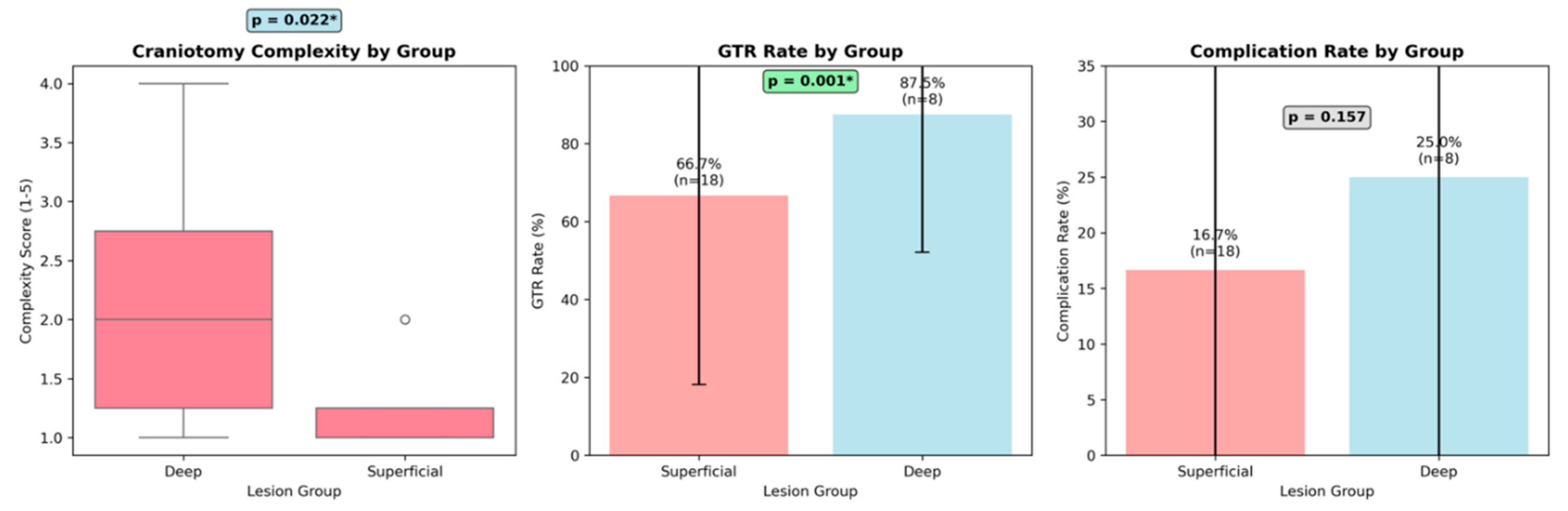

Gross total resection was achieved in 100% of superficial lesions compared to 46.2% of deep lesions (p<0.001). Overall complication rates were 14.3% (2/14) for superficial lesions and 23.1% (3/13) for deep lesions. In the superficial group, both complications were intraoperative seizures occurring in patients with frontal lesions (patients 5 and 10), which were classified as lesion-related due to the inherent epileptogenic nature of frontal cortex manipulation. These seizures were successfully managed intraoperatively without permanent sequelae. In the deep lesion group, complications included postoperative hemorrhage in two patients (thalamic cavernous angioma and paratrigonal metastasis) and cranial nerve palsy in one patient with a ponto-mesencephalic angioma. Deep lesion complications were categorized as mixed etiology, being primarily lesion-related due to complex vascular anatomy and critical location, but potentially influenced by exoscope limitations in depth perception for deep-seated structures. All superficial lesion complications appeared to be entirely lesion-related, with the exoscope potentially offering advantages through enhanced visualization for cortical mapping. Deep lesion complications demonstrated mixed etiology, with lesion complexity as the primary factor but possible contribution from exoscope technological limitations in providing optimal depth perception for critical anatomical structures. Statistical analysis of 27 neurosurgical cases using the exoscope revealed significant differences between superficial and deep brain tumor resections across multiple clinical parameters. Patient positioning showed a highly significant association with lesion depth (χ² = 26.0, p < 0.001), with all superficial lesions (100%) utilizing supine positioning compared to none of the deep lesions (0%), which required non-supine approaches. Gross Total Resection (GTR) rates demonstrated a statistically significant difference between groups (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.005), with superficial lesions achieving universal GTR success (13/13, 100%) versus deep lesions achieving GTR in only 46.2% of cases (6/13). Complication rates, while numerically higher in the deep lesion group (23.1% vs 14.3%), did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.648), suggesting that despite the increased technical complexity, the exoscope maintained acceptable safety profiles across both groups. Craniotomy complexity analysis revealed a trend toward more complex surgical approaches in deep lesions (23.1% vs 0%, p = 0.098), though this did not reach statistical significance. These findings provide robust statistical evidence supporting the clinical observation that while superficial lesions benefit from the exoscope's enhanced visualization in predictable surgical scenarios, deep lesions derive particular value from the system's 360° rotational capability and flexible positioning, which becomes essential when traditional microscope ergonomics are inadequate for complex anatomical approaches (

Table 3;

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This study represents one of the first systematic evaluations of the relationship between craniotomy complexity and surgical outcomes in patients undergoing brain tumor resection with exoscope technology. Our findings provide several important insights into the clinical utility of advanced visualization systems across the spectrum of neurosurgical complexity. Our analysis of 26 consecutive cases revealed significant differences in surgical complexity between superficial and deep lesions, with deep lesions requiring more complex craniotomy approaches (p = 0.022). This finding aligns with established neurosurgical principles, as deep-seated tumors typically necessitate more extensive bone removal, complex surgical corridors, and potentially multiple approach angles to achieve adequate visualization and safe resection [

12,

13]. The systematic complexity scoring system we developed (ranging from 1-5) effectively captured these differences, with deep lesions showing a higher median complexity score compared to superficial lesions. Despite the increased surgical complexity associated with deep lesions, we observed a paradoxical finding regarding gross total resection (GTR) rates. Superficial lesions demonstrated significantly higher GTR rates compared to deep lesions (p = 0.001), suggesting that lesion depth and the anatomical site remains a critical factor in determining resection extent even with advanced visualization technology. This finding is consistent with previous literature indicating that tumor location and accessibility are primary determinants of extent of resection [

14,

15,

16]. Importantly, our analysis revealed no significant correlation between craniotomy complexity and complication rates (r = 0.154, p = 0.453), nor did we observe significant differences in complication rates between superficial and deep lesion groups (p = 0.157). This finding suggests that the exoscope technology may provide sufficient visualization quality to maintain safety across different levels of surgical complexity, potentially mitigating some of the traditional risks associated with more complex approaches. The lack of correlation between surgical complexity and complications has important clinical implications for surgical planning and patient counseling. Traditionally, complex approaches for deep seated lesions have been associated with increased morbidity risk [

4,

17]. Our findings suggest that with appropriate visualization technology, the complexity of the surgical approach may be less predictive of complications than previously assumed. This could influence surgical decision-making, potentially encouraging surgeons to utilize more complex approaches when necessary to optimize tumor exposure and resection.

The superior GTR rates observed in superficial lesions (despite similar complication rates) highlight the continued importance of tumor location in surgical planning. While exoscope technology provides excellent visualization, it cannot overcome the fundamental anatomical challenges posed by deep-seated lesions, including longer surgical corridors, proximity to eloquent structures, and limited maneuverability. These findings emphasize the need for careful patient selection and realistic outcome expectations when treating deep lesions. The consistent safety profile observed across different complexity levels may reflect several advantages of exoscope technology. The high-definition 3D visualization provided by modern exoscopes offers superior depth perception compared to traditional 2D monitors, while maintaining the magnification capabilities of operating microscopes [

18]. The ergonomic benefits, including natural head positioning and reduced neck strain, may contribute to improved surgical precision during lengthy procedures [

19,

20]. Additionally, the ability to share the surgical view with the entire operative team through large external monitors may enhance surgical safety through improved communication and collaborative decision-making [

2]. This is particularly relevant for complex cases where multiple team members need to understand the surgical anatomy and potential risks.

The consistent safety profile observed across different complexity levels may reflect several advantages of exoscope technology, particularly the revolutionary 360-degree rotational camera capability. The high-definition 3D visualization provided by modern exoscopes offers superior depth perception compared to traditional 2D monitors, while maintaining the magnification capabilities of operating microscopes [

7]. The ergonomic benefits, including natural head positioning and reduced neck strain, may contribute to improved surgical precision during lengthy procedures [

20].

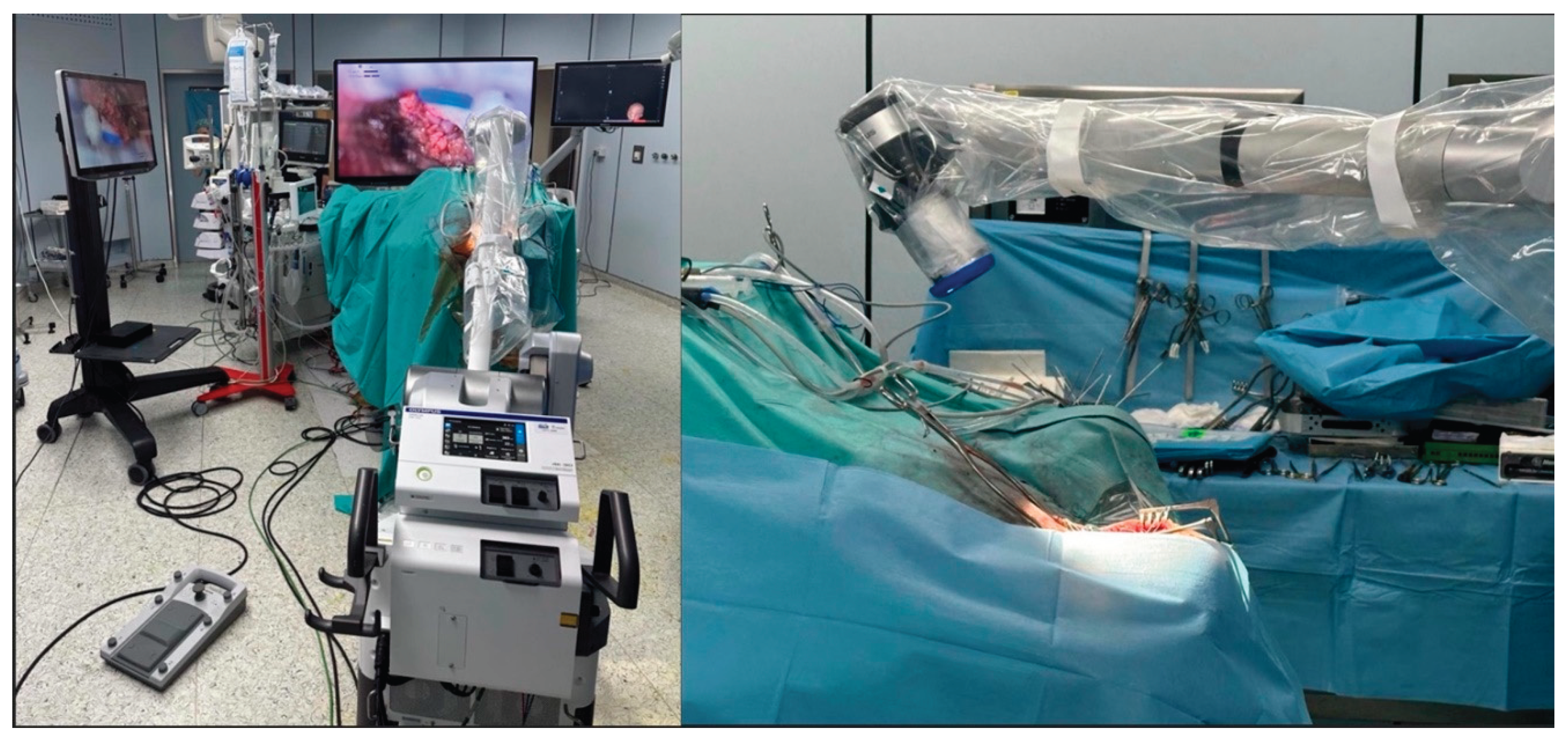

The 360-degree rotational functionality of the exoscope camera represents a paradigm shift in neurosurgical visualization, offering unprecedented flexibility in viewing angles without requiring repositioning of the entire optical system [

17,

18,

19,

20]. This capability is particularly advantageous in complex craniotomy cases where multiple surgical corridors and approach angles are necessary. Traditional operating microscopes require physical repositioning or tilting of the entire optical assembly to achieve different viewing angles, which can be time-consuming, disruptive to surgical flow, and may compromise sterility. In contrast, the 360-degree rotational camera allows surgeons to seamlessly transition between different viewing perspectives with simple digital controls, maintaining continuous visualization while exploring various aspects of the surgical field. This is especially valuable when working around critical neurovascular structures, where the ability to quickly assess anatomy from multiple angles can enhance safety and surgical decision-making (

Figure 2).

Furthermore, the 360-degree rotation eliminates the need for frequent microscope repositioning, which traditionally required interruption of the surgical procedure and potential loss of anatomical orientation. This continuous visualization capability may contribute to reduced operative times and improved surgical efficiency, particularly in complex cases requiring extensive tumor dissection from multiple angles. The rotational camera technology also enhances surgical education and team collaboration by allowing optimal viewing angles to be shared simultaneously with all team members on external monitors [

19,

21]. This shared perspective can improve communication during critical surgical moments and facilitate real-time consultation with colleagues, regardless of their physical position in the operating room.

Several limitations of our study warrant consideration. The relatively small sample size (n = 26) limits the statistical power to detect smaller effect sizes and may not capture rare complications. The single-center design and specific exoscope system used may limit generalizability to other institutions and technologies. The complexity scoring system, while systematic, remains somewhat subjective and would benefit from validation in larger cohorts. The retrospective nature of our analysis prevents definitive causal inferences about the relationship between exoscope use and outcomes. Future prospective studies comparing exoscope technology to traditional microscopy across matched complexity levels would provide stronger evidence for the technology's clinical benefits. Our analysis focused on immediate surgical outcomes and did not evaluate long-term oncological outcomes, quality of life measures, or cost-effectiveness considerations. These factors are crucial for comprehensive technology assessment and should be addressed in future investigations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that while craniotomy complexity differs significantly between superficial and deep brain lesions, the use of exoscope technology appears to maintain consistent safety profiles across complexity levels. The superior GTR rates in superficial lesions reflect persistent anatomical challenges rather than technological limitations. These findings support the continued adoption of exoscope technology in neurosurgical practice while emphasizing the importance of appropriate patient selection and realistic outcome expectations based on tumor characteristics rather than surgical complexity alone. Future research should focus on larger prospective studies, long-term outcome assessment, and comparative analyses with traditional microscopy to further define the optimal role of exoscope technology in modern neurosurgical practice.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Messina.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| | GTR |

| Gross Total Resection |

| | STR |

| Subtotal Resection |

| | 5-ALA |

| 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| | GBM |

| Glioblastoma Multiforme |

| | FTOZ |

| Fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic |

| | CC |

| Corpus Callosum |

References

- Fiani B, Jarrah R, Griepp DW, Adukuzhiyil J. The Role of 3D Exoscope Systems in Neurosurgery: An Optical Innovation. Cureus. 2021 Jun 23;13(6):e15878. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi L, Chaichana KL, Cardia A, Stifano V, Rossini Z, Olivi A, Sturiale CL. The Exoscope in Neurosurgery: An Innovative "Point of View". A Systematic Review of the Technical, Surgical, and Educational Aspects. World Neurosurg. 2019 Apr;124:136-144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro N, Scerrati A, Ricciardi L, Trevisi G. The Exoscope in Neurosurgery: An Overview of the Current Literature of Intraoperative Use in Brain and Spine Surgery. J Clin Med. 2021 Dec 31;11(1):223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscas G, Battista F, Boschi A, Morone F, Della Puppa A. A Single-Center Experience with the Olympus ORBEYE 4K-3D Exoscope for Microsurgery of Complex Cranial Cases: Technical Nuances and Learning Curve. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2021 Sep;82(5):484-489. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apra C, Bemora JS, Palfi S. Achieving Gross Total Resection in Neurosurgery: A Review of Intraoperative Techniques and Their Influence on Surgical Goals. World Neurosurg. 2024 May;185:246-253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angileri FF, Raffa G, Curcio A, Granata F, Marzano G, Germanò A. Minimally Invasive Surgery of Deep-Seated Brain Lesions Using Tubular Retractors and Navigated Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Based Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography Guidance: The Minefield Paradigm. Oper Neurosurg. 2023 Jun 1;24(6):656-664. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garufi G, Conti A, Chaurasia B, Cardali SM. Exoscopic versus Microscopic Surgery in 5-ALA-Guided Resection of High-Grade Gliomas. J Clin Med. 2024 Jun 14;13(12):3493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raheja A, Mishra S, Garg K, Katiyar V, Sharma R, Tandon V, Goda R, Suri A, Kale SS. Impact of different visualization devices on accuracy, efficiency, and dexterity in neurosurgery: a laboratory investigation. Neurosurg Focus. 2021 Jan;50(1):E18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariffin MHM, Ibrahim K, Baharudin A, Tamil AM. Early Experience, Setup, Learning Curve, Benefits, and Complications Associated with Exoscope and Three-Dimensional 4K Hybrid Digital Visualizations in Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. Asian Spine J. 2020 Feb;14(1):59-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layard Horsfall H, Mao Z, Koh CH, Khan DZ, Muirhead W, Stoyanov D, Marcus HJ. Comparative Learning Curves of Microscope Versus Exoscope: A Preclinical Randomized Crossover Noninferiority Study. Front Surg. 2022 Jun 6;9:920252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa Y, Tobita M, Takahashi R, Ito T, Senda D, Tanaka R, Mizuno H, Sano K. Learning Curve and Ergonomics Associated with the 3D-monitor-assisted Microsurgery Using a Digital Microscope. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Jun 17;2(1):1-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson SB, Hendricks BK, Torregrossa F, Grasso G, Cohen-Gadol AA. Innovations in the Art of Microneurosurgery for Reaching Deep-Seated Cerebral Lesions. World Neurosurg. 2019 Nov;131:321-327. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Gadol, AA. The Paramedian Supracerebellar Approach: A Less Disruptive and More Flexible Operative Corridor to the Pineal and Posterior Upper Brainstem Regions. World Neurosurg. 2020 Nov;143:647-657. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutlay M, Durmaz O, Ozer İ, Kırık A, Yasar S, Kural C, Temiz Ç, Tehli Ö, Ezgu MC, Daneyemez M, Izci Y. Fluorescein Sodium-Guided Neuroendoscopic Resection of Deep-Seated Malignant Brain Tumors: Preliminary Results of 18 Patients. Oper Neurosurg. 2021 Jan 13;20(2):206-218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong CS, Prevedello DM, Elder JB. Comparison of endoscope- versus microscope-assisted resection of deep-seated intracranial lesions using a minimally invasive port retractor system. J Neurosurg. 2016 Mar;124(3):799-810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohl MA, Oppenlander ME, Spetzler R. A Prospective Cohort Evaluation of a Robotic, Auto-Navigating Operating Microscope. Cureus. 2016 Jun 30;8(6):e662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marenco-Hillembrand L, Prevatt C, Suarez-Meade P, Ruiz-Garcia H, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chaichana KL. Minimally Invasive Surgical Outcomes for Deep-Seated Brain Lesions Treated with Different Tubular Retraction Systems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020 Nov;143:537-545.e3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remacha J, Navarro-Díaz M, Larrosa F. Experience with three-dimensional exoscope-assisted surgery of giant mastoid process osteoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2022 Sep;136(9):875-877. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin H, Chen F, Lin T, Mo J, Chen Z, Wang Z, Liu W. Beyond Magnification and Illumination: Ergonomics with a 3D Exoscope in Lumbar Spine Microsurgery to Reduce Musculoskeletal Injuries. Orthop Surg. 2023 Jun;15(6):1556-1563. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schupper AJ, Hrabarchuk EI, McCarthy L, Hadjipanayis CG. Improving Surgeon Well-Being: Ergonomics in Neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2023 Jul;175:e1220-e1225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layard Horsfall H, Mao Z, Koh CH, Khan DZ, Muirhead W, Stoyanov D, Marcus HJ. Comparative Learning Curves of Microscope Versus Exoscope: A Preclinical Randomized Crossover Noninferiority Study. Front Surg. 2022 Jun 6;9:920252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).