Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

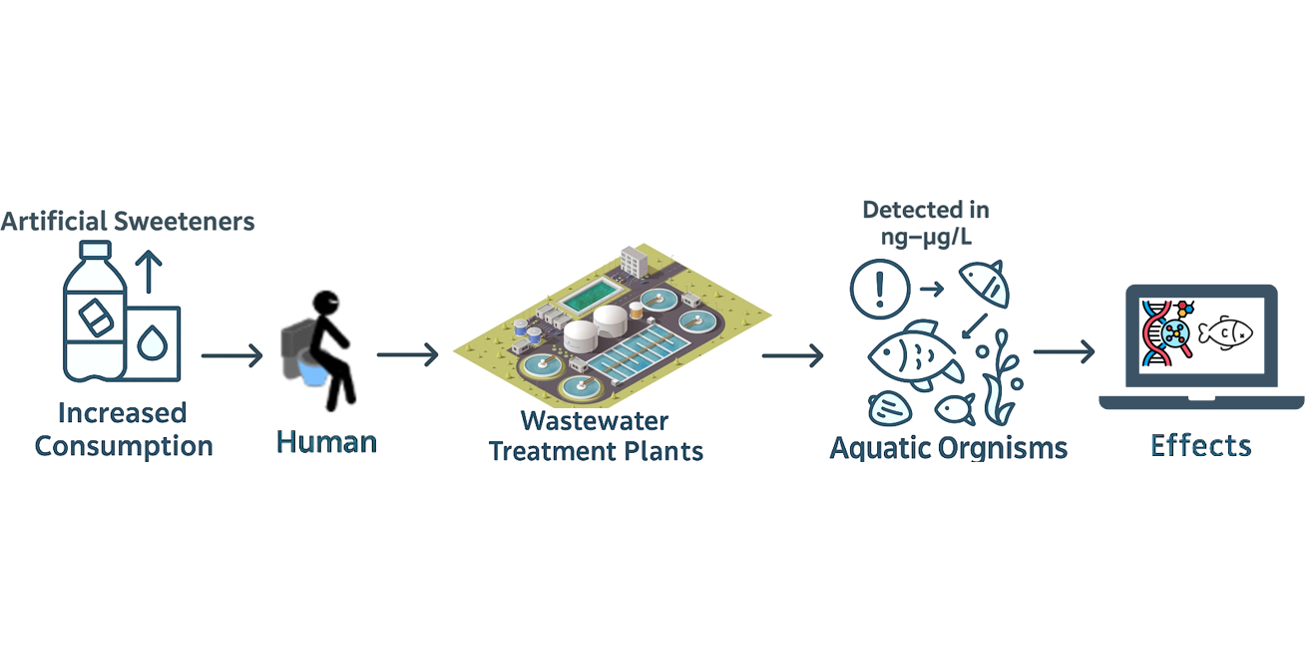

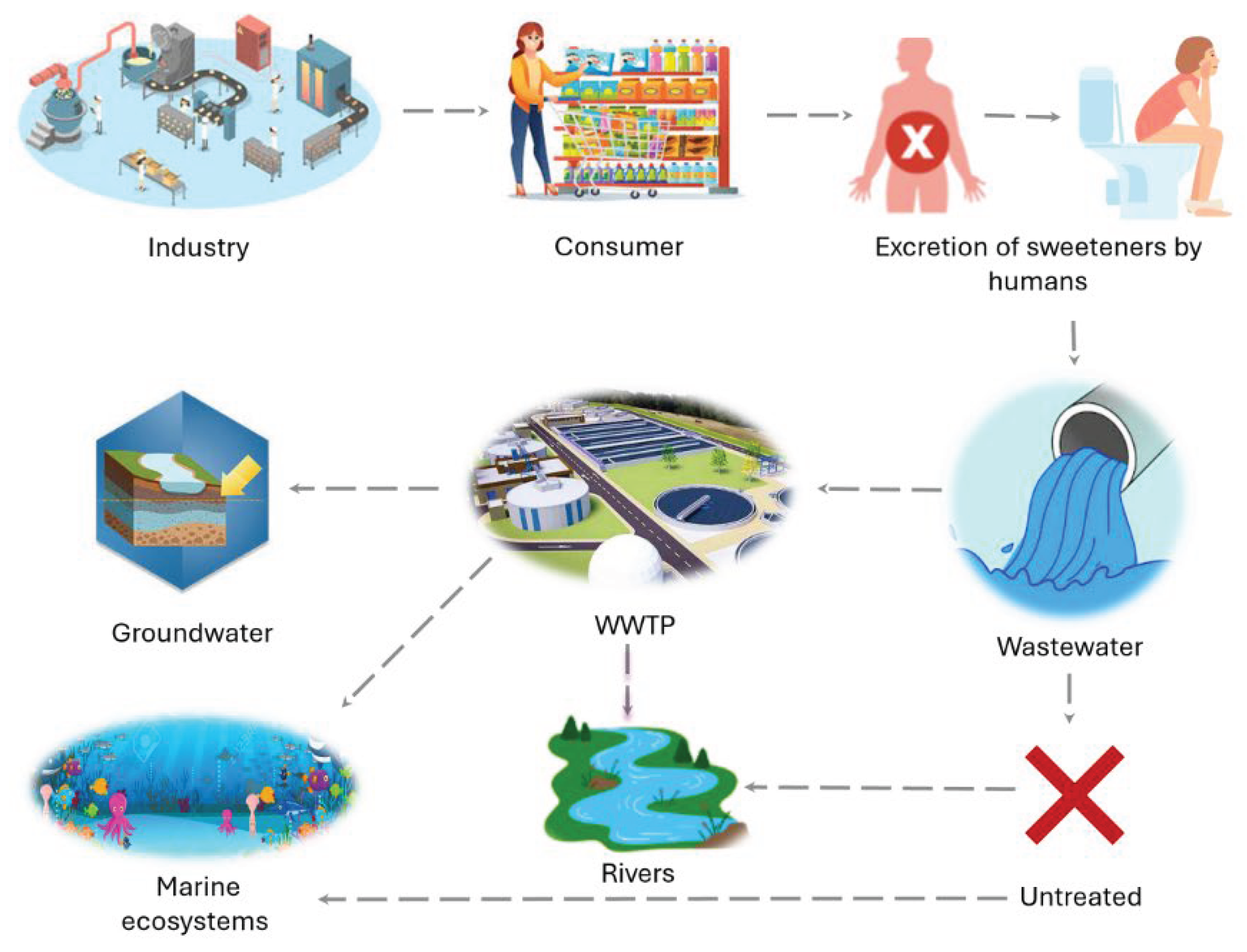

1. Introduction

2. Bibliographic Search

3. Use and Consumption

4. Sources of Artificial Sweeteners in Aquatic Ecosystems

5. Concentrations of Sweeteners in Environmental Matrices

| Sweeteners | Country | Aquatic environmental | Concentrations (μg L-1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclamate | Germany | WWTP influent | 190 | [36] |

| WWTP influent | 250 | [37] | ||

| Korea | Groundwater | 0.155 | [38] | |

| Surface water | 120 | [39] | ||

| Canada | Groundwater | 0.003 | [40] | |

| Spain | WWTP influent | 26.7–78.3 | [41] | |

| Coastal waters | 0.01–0.08 | |||

| WWTP effluent | 0.03–0.06 | |||

| Surface water | 0.08 | [42] | ||

| WWTP effluent | 19.2 | |||

| Neotame | China | WWTP influent | 0.03 | [43] |

| WWTP effluent | 0.03 | [43] | ||

| WWTP effluent | 10 | [12] | ||

| Surface water | 9.3 | [12] | ||

| Drinking water | 6.94 | [44] | ||

| Aspartame | Vietnam | WWTP effluent | 3.1 | [45] |

| China | Surface water | 0.21 | [39] | |

| River sediments | 0.3 | [43] | ||

| Spain | WWTP influent | 0.07 | [41] | |

| WWTP effluent | 0.09 | [41] | ||

| Switzerland | WWTP effluent | 0.01 | [42] | |

| USA | WWTP effluent | 0.1 | [9] | |

| WWTP influent | 0.1 | |||

| WWTP influent | 1.6 | [26] | ||

| WWTP effluent | 1.8 | |||

| WWTP influent | 0.13 | [33] | ||

| Saccharin | Germany | WWTP influent | 40 | [36] |

| Australia | WWTP effluent | 7.1 | [46] | |

| China | Coastal waters | 0.21 | [47] | |

| WWTP effluent | 0.42 | [39] | ||

| Seawater | 50.2 | [33] | ||

| Spain | WWTP effluent | 9.1 | [48] | |

| WWTP influent | 18.4 | |||

| Seawater | 0.00523 | [35] | ||

| India | WWTP influent | 303.0 | [26] | |

| USA | WWTP effluent | 15.1 | [26] | |

| WWTP influent | 1.4 | [26] | ||

| Vietnam | Surface water | 1.3 | [45] | |

| Table 1. Cont | ||||

| Switzerland | WWTP effluent | 16.2 | [42] | |

| Acesulfame | Australia | Groundwater | 0.34 | [49] |

| Germany | Groundwater | 34 | [50] | |

| WWTP influent | 22.9 | [51] | ||

| WWTP influent | 40 | [36] | ||

| Brazil | WWTP effluent | 13 | [33] | |

| Canada | Surface water | 0.227 | [52] | |

| Groundwater | 0.653 | [51] | ||

| Korea | Groundwater | 0.0329 | [38] | |

| China | Surface water | 2.78 | [53] | |

| Surface water | 2.9 | [51] | ||

| Spain | WWTP effluent | 155 | [42] | |

| Italy | WWTP effluent | 2,500 | [13] | |

| Norway | Surface water | 25 | [54] | |

| Nigeria | WWTP effluent | 16 | [55] | |

| Czech Republic | WWTP influent | 22.67 | [56] | |

| Switzerland | Groundwater | 0.524 | [57] | |

| Groundwater | 4.7 | [24] | ||

| Singapore | WWTP effluent | 29.9 | [51] | |

| 135.76 | [58] | |||

| 10.51 | [59] | |||

| USA | WWTP effluent | 50 | [60] | |

| Sucralose | Norway | Surface water | 8 | [61] |

| Sweden | Surface water | 3.5 | [61] | |

| Korea | WWTP influent | 1.5 | [62] | |

| Brazil | WWTP influent | 31 | [33] | |

| China | WWTP effluent | 1.9 | [46] | |

| China | WWTP effluent | 1.5 | [43] | |

| WWTP influent | 1.0 | [43] | ||

| Spain | WWTP influent | 5.3 | [48] | |

| WWTP effluent | 18.1 | |||

| Italy | River | 0.344 | [61] | |

| Switzerland | WWTP effluent | 4.5 | [63] | |

| WWTP influent | 4.5 | [24] | ||

| USA | Surface water | 1.8 | [62] | |

| Drinking water | 2.4 | [64] | ||

| WWTP effluent | 650 | [26] | ||

| 30 | [63] | |||

| 1.8 | [47] | |||

| Table 1. Cont | ||||

| 0.9 | [65] | |||

| WWTP influent | 1 | [60] | ||

| 1.9 | [64] | |||

| 27.7 | [26] | |||

6. Effects

| Sweeteners | Organisms | Concentration µg L-1 |

Assay | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ace-K | Danio rerio | 50 | Biomarker assay | Increased HPC and LPX activity | [16] |

| 10,000 | Light/dark preference test (LDP) | Increased anxiety | [72] | ||

| 10,000 | Test NTDT | Increased anxiety | [72] | ||

| 10,000 | CPP behavioral testing | Impaired learning and memory capacity | [72] | ||

| >1,000,000 | Acute toxicity test LC50 - 96h | Mortality | [51] | ||

| 24 | Toxicity test IC50 -24h | Effects on swimming and feeding | [67] | ||

| Cyprinus carpio | 0.05 | Biomarker assay | Increased HPC and SOD activity |

[76] | |

| Carassius auratus | 100 | Biomarker Assay | Increased SOD activity | [75] | |

| Daphnia magna | 100 | In vivo cardiac toxicity assay | Increased cardiac | [77] | |

| 24 | Toxicity test IC5O-24h | Swimming impairment | [67] | ||

| 28 | Toxicity test IC5O-24h | Affecting feeding activity | [67] | ||

| 1,600,000 | Acute Toxicity Test LC50 - 48h | Mortality | [56] | ||

| 0.1 | Biomarker assay | Decreased AChE activity | [67] | ||

| Aspartame | Daphnia magna | 0.1 | Biomarker assay | Increased AChE activity | [67] |

| Danio rerio | 0.49 | In situ hybridization assay | Inhibition of neutrophil production | [78] | |

| 20 | Teratogenicity test | Cartilage malformation | [71] | ||

| 20 | In vitro Toxicity Assay | Decreased in locomotor activity | [71] | ||

| 60 | Western Blot Technique | Decreased expression of SIRT1 and FOXO3a proteins in neurons. | [71] | ||

| Cyclamate | Danio rerio | 100 | Biomarker assay | Increased AChE activity |

[68] |

| Table 2. Cont. | |||||

| Daphnia magna | 1,000 | Chronic toxicity test 21-d | Difficulty in reproduction | [73] | |

| Saccharin | Danio rerio | 1,000 | Light/dark preference tests (LDP) | Alteration of neurotrans-mitter homeostasis in the brain. | [79] |

| 100,000 | Acute Toxicity Test EC50-48h | Immobilization | [80] | ||

| 1,000 | Light/dark preference test (LDP) | Excessive increase during swimming | [81] | ||

| 100 | Biomarker assay | Increased dopamine | [68] | ||

| Sucralose | Danio rerio | 0.05 | Biomarker assay |

Increased in LPX, HPC, and PCC activity |

[74] |

| 0.05 | qRT-PCR molecular technique | Over-expression of Nrf1a and Nrf2a genes | [74] | ||

| 116. 5 | Acute Toxicity Test LC50-96h | Mortality | [74] | ||

| Cyprinus carpio | 0.05 | Comet assay | DNA damage | [70] | |

| Tunnel test | Apoptosis | [70] | |||

| 0.05 | Biomarker assay | Increased in HPC, LPX, PCC and SOD activity | [82] | ||

| Gammarus zaddachi | 500 | Biomarker assay | Increased AChE and LPX activity | [83] | |

| 5,000 | Toxicity test 14-d | Increased respiration | [84] | ||

| Daphnia magna | 20.1 | Biomarker assay | Increased AChE activity | [67] | |

| 5 | Toxicity Test (Toximeter II) |

Increased swimming | [84] | ||

| 0.1 | Biomarker assay | Increased AChE activity | [83] | ||

| 175 | Toxicity test IC50-24h |

Abnormal swimming | [67] | ||

| 235 | Toxicity test IC50-24h |

Alteration in feeding activity | [67] | ||

| Nitocra spinipes | 0.5 | Acute Toxicity Test LC50-96h | Mortality | [84] | |

| Calanus glacialis | 0.05 | Toxicity test 72-h | Decrease in egg production | [85] | |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- von Rymon Lipinski, G.W. The New Intense Sweetener Acesulfame K. Food Chem 1985, 16, 259–269. [CrossRef]

- Sang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Tsoi, Y.K.; Leung, K.S.Y. Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Artificial Sweeteners: A Study of Their Distributions, Photodegradation and Toxicities. Water Res 2014, 52, 260–274. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.; Denny, V.; Zahedi, I.; Bidaisee, S. The Whey and Casein Protein Powder Consumption: - ProQuest Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2136005450?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.; Babu, K.; Deuster, P.A.; Shearer, J. Energy Drinks: A Contemporary Issues Paper. Curr Sports Med Rep 2018, 17, 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Sievenpiper, J.L.; Chan, C.B.; Dworatzek, P.D.; Freeze, C.; Williams, S.L. Nutrition Therapy. Can J Diabetes 2018, 42, S64–S79. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R.; Arias Espana, V.A.; Liu, Y.; Jit, J. Emerging Contaminants in the Environment: Risk-Based Analysis for Better Management. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 350–357. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Colás-Ruiz, N.R.; Bolívar-Anillo, H.J.; Anfuso, G.; Hampel, M. Occurrence and Effects of Antimicrobials Drugs in Aquatic Ecosystems. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 13428 2021, 13, 13428. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. The Safety and Regulatory Process for Low Calorie Sweeteners in the United States. Physiol Behav 2016, 164, 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Praveena, S.M.; Cheema, M.S.; Guo, H.R. Non-Nutritive Artificial Sweeteners as an Emerging Contaminant in Environment: A Global Review and Risks Perspectives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 170, 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ren, Y.; Fu, Y.; Gao, X.; Jiang, C.; Wu, G.; Ren, H.; Geng, J. Fate of Artificial Sweeteners through Wastewater Treatment Plants and Water Treatment Processes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0189867. [CrossRef]

- Trawiński, J.; Skibiński, R. Stability of Aspartame in the Soft Drinks: Identification of the Novel Phototransformation Products and Their Toxicity Evaluation. Food Research International 2023, 173, 113365. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Deng, J.; Lu, S.; Li, X.; Dietrich, A.M. Aqueous Degradation of Artificial Sweeteners Saccharin and Neotame by Metal Organic Framework Material. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 761, 143181. [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Carvalho, R.; António, D.C.; Comero, S.; Locoro, G.; Tavazzi, S.; Paracchini, B.; Ghiani, M.; Lettieri, T.; Blaha, L.; et al. EU-Wide Monitoring Survey on Emerging Polar Organic Contaminants in Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents. Water Res 2013, 47, 6475–6487. [CrossRef]

- Kobeticová, K.; Mocová, K.A.; Mrhálková, L.; Petrová, Š. Effects of Artificial Sweeteners on Lemna Minor. https://cjfs.agriculturejournals.cz/doi/10.17221/413/2016-CJFS.html 2018, 36, 386–391. [CrossRef]

- Tollefsen, K.E.; Nizzetto, L.; Huggett, D.B. Presence, Fate and Effects of the Intense Sweetener Sucralose in the Aquatic Environment. Science of the Total Environment 2012, 438, 510–516. [CrossRef]

- Colín-García, K.; Elizalde-Velázquez, G.A.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; García-Medina, S. Influence of Sucralose, Acesulfame-k, and Their Mixture on Brain’s Fish: A Study of Behavior, Oxidative Damage, and Acetylcholinesterase Activity in Danio Rerio. Chemosphere 2023, 340. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. wei; Shen, Z. wei; Hua, Z. lin; Li, X. qing Global Development and Future Trends of Artificial Sweetener Research Based on Bibliometrics. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 263. [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Rother, K.I. Trends in the Consumption of Low-Calorie Sweeteners. Physiol Behav 2016, 164, 446–450. [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.N.; Morgan, J.B.; Avery, G.B.; Kieber, R.J.; Kirk, A.M.; Skrabal, S.A.; Willey, J.D. Occurrence of the Artificial Sweetener Sucralose in Coastal and Marine Waters of the United States. Mar Chem 2009, 116, 13–17. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Oturan, M.; Kim, H. Oxidation of Artificial Sweetener Sucralose by Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 8525–8533. [CrossRef]

- Cp, K. Determination of the Saccharin Content in Some Ice Creams Available in Market. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition www.foodsciencejournal.com 2018, 3, 158–160.

- Bahndorf, D.; Kienle, U. World Market of Sugar and Sweeteners; 2004;

- Q Yang Gain Weight by “Going Diet?” Artificial Sweeteners and the Neurobiology of Sugar Cravings: Neuroscience 2010 - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20589192/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Buerge, I.J.; Buser, H.R.; Kahle, M.; Müller, M.D.; Poiger, T. Ubiquitous Occurrence of the Artificial Sweetener Acesulfame in the Aquatic Environment: An Ideal Chemical Marker of Domestic Wastewater in Groundwater. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43, 4381–4385. [CrossRef]

- Foodchem Consumo de Edulcorantes de Alta Intensidad a Nivel Mundial - FOODCHEM Available online: https://www.foodchem.cn/News/126.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Subedi, B.; Kannan, K. Fate of Artificial Sweeteners in Wastewater Treatment Plants in New York State, U.S.A. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, 13668–13674. [CrossRef]

- Colín García, K. Efectos Tóxicos Inducidos Por Concentraciones Ambientalmente Relevantes de Sucralosa, Acesulfame- k y Sus Mezclas En Danio Rerio. 2024.

- John, B.A.; Wood, S.G.; Hawkins, D.R. The Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Sucralose in the Mouse. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2000, 38, 107–110. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Renwick, A.G.; Sims, J.; Snodin, D.J. Sucralose Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics in Man. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2000, 38, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, H. Periodate Activation for Degradation of Organic Contaminants: Processes, Performance and Mechanism. Sep Purif Technol 2022, 292. [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, M.; Feng, M. Emerging Periodate-Based Oxidation Technologies for Water Decontamination: A State-of-the-Art Mechanistic Review and Future Perspectives. J Environ Manage 2022, 323, 116241. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Oturan, N.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Oturan, M.A. Cold Incineration of Sucralose in Aqueous Solution by Electro-Fenton Process. Sep Purif Technol 2017, 173, 218–225. [CrossRef]

- Alves, P. da C.C.; Rodrigues-Silva, C.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Rath, S. Removal of Low-Calorie Sweeteners at Five Brazilian Wastewater Treatment Plants and Their Occurrence in Surface Water. J Environ Manage 2021, 289, 112561. [CrossRef]

- Coronado-Apodaca, K.G.; Rodríguez-De Luna, S.E.; Araújo, R.G.; Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; González-Meza, G.M.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Sosa-Hernandez, J.E.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldivar, R. Occurrence, Transport, and Detection Techniques of Emerging Pollutants in Groundwater. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102160. [CrossRef]

- Brumovský, M.; Bečanová, J.; Kohoutek, J.; Borghini, M.; Nizzetto, L. Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the Open Sea Waters of the Western Mediterranean. Environmental Pollution 2017, 229, 976–983. [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, M.; Brauch, H.J.; Lange, F.T. Analysis and Occurrence of Seven Artificial Sweeteners in German Waste Water and Surface Water and in Soil Aquifer Treatment (SAT). Anal Bioanal Chem 2009, 394, 1585–1594. [CrossRef]

- Zirlewagen, J.; Licha, T.; Schiperski, F.; Nödler, K.; Scheytt, T. Use of Two Artificial Sweeteners, Cyclamate and Acesulfame, to Identify and Quantify Wastewater Contributions in a Karst Spring. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 547, 356–365. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Hamm, S.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.K.; Oh, J.E. Occurrence and Distribution of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, Artificial Sweeteners, and Pesticides in Groundwater from an Agricultural Area in Korea. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 659, 168–176. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, P.; Ren, X. Transformation of Acesulfame in Water under Natural Sunlight: Joint Effect of Photolysis and Biodegradation. Water Res 2014, 64, 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Van Stempvoort, D.R.; Roy, J.W.; Grabuski, J.; Brown, S.J.; Bickerton, G.; Sverko, E. An Artificial Sweetener and Pharmaceutical Compounds as Co-Tracers of Urban Wastewater in Groundwater. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 461–462, 348–359. [CrossRef]

- Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; Traverso-Soto, J.M.; Biel-Maeso, M.; Villar-Navarro, E.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Sources and Trends of Artificial Sweeteners in Coastal Waters in the Bay of Cadiz (NE Atlantic). Mar Pollut Bull 2018, 135, 607–616. [CrossRef]

- Arbeláez, P.; Borrull, F.; Pocurull, E.; Marcé, R.M. Determination of High-Intensity Sweeteners in River Water and Wastewater by Solid-Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2015, 1393, 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, J.; Gao, Y. Tracking the Fate of Artificial Sweeteners within the Coastal Waters of Shenzhen City, China: From Wastewater Treatment Plants to Sea. J Hazard Mater 2021, 414, 125498. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A.M.; Pang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Ma, X. Mini Review: Will Artificial Sweeteners Discharged to the Aqueous Environment Unintentionally “Sweeten” the Taste of Tap Water? Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021, 6, 100100. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Bach, L.T.; Van Dinh, P.; Prudente, M.; Aguja, S.; Phay, N.; Nakata, H. Ubiquitous Detection of Artificial Sweeteners and Iodinated X-Ray Contrast Media in Aquatic Environmental and Wastewater Treatment Plant Samples from Vietnam, the Philippines, and Myanmar. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2016, 70, 671–681. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; O’Brien, J.W.; Tscharke, B.J.; Choi, P.M.; Zheng, Q.; Ahmed, F.; Thompson, J.; Li, J.; Mueller, J.F.; Sun, H.; et al. National Wastewater Reconnaissance of Artificial Sweetener Consumption and Emission in Australia. Environ Int 2020, 143, 105963. [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.Q.; Zafar, T.; Shrivastava, V.K. Environmental Impact of the Presence, Distribution, and Use of Artificial Sweeteners as Emerging Sources of Pollution. J Environ Public Health 2021, 2021, 6624569. [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, E.Y.; Quintana, J.B.; Rodil, R.; Cela, R. Determination of Artificial Sweeteners in Water Samples by Solid-Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2012, 1256, 197–205. [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; Torres-Martínez, J.A.; Capparelli, M. V.; Zabala, A.; Mahlknecht, J. Effects of Wastewater Irrigation on Groundwater Quality: An Overview. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2022, 25, 100322. [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.T.; Scheurer, M.; Brauch, H.J. Artificial Sweeteners-A Recently Recognized Class of Emerging Environmental Contaminants: A Review. Anal Bioanal Chem 2012, 403, 2503–2518. [CrossRef]

- Belton, K.; Schaefer, E.; Guiney, P.D. A Review of the Environmental Fate and Effects of Acesulfame-Potassium. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2020, 16, 421–437. [CrossRef]

- Sérodes, J.B.; Behmel, S.; Simard, S.; Laflamme, O.; Grondin, A.; Beaulieu, C.; Proulx, F.; Rodriguez, M.J. Tracking Domestic Wastewater and Road De-Icing Salt in a Municipal Drinking Water Reservoir: Acesulfame and Chloride as Co-Tracers. Water Res 2021, 203, 117493. [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Wang, L.; Wei, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, Y. Sucralose and Acesulfame as an Indicator of Domestic Wastewater Contamination in Wuhan Surface Water. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 189, 109980. [CrossRef]

- Kokotou, M.G.; Asimakopoulos, A.G.; Thomaidis, N.S. Artificial Sweeteners as Emerging Pollutants in the Environment: Analytical Methodologies and Environmental Impact. Analytical Methods 2012, 4, 3057–3070. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.X.; Olaitan, O.J.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.Y.; Chimezie, A.; Adepoju-Bello, A.A.; Ying, G.G.; Chen, C.E. What Is in Nigerian Waters? Target and Non-Target Screening Analysis for Organic Chemicals. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131546. [CrossRef]

- Kerberová, V.; Zlámalová Gargošová, H.; Čáslavský, J. Occurrence and Ecotoxicity of Selected Artificial Sweeteners in the Brno City Waste Water. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 19, 9055–9066. [CrossRef]

- Ens, W.; Senner, F.; Gygax, B.; Schlotterbeck, G. Development, Validation, and Application of a Novel LC-MS/MS Trace Analysismethod for the Simultaneous Quantification of Seven Iodinated X-Ray Contrast Media and Three Artificial Sweeteners in Surface, Ground, and Drinking Water. Anal Bioanal Chem 2014, 406, 2789–2798. [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Ong, S.L. Suitability of Artificial Sweeteners as Indicators of Raw Wastewater Contamination in Surface Water and Groundwater. Water Res 2014, 48, 443–456. [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Gan, J.; Nguyen, V.T.; Chen, H.; You, L.; Duarah, A.; Zhang, L.; Gin, K.Y.H. Sorption and Biodegradation of Artificial Sweeteners in Activated Sludge Processes. Bioresour Technol 2015, 197, 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, J.; Eaton, A.; Badruzzaman, M.; Haghani, A.W.; Jacangelo, J.G. Occurrence and Suitability of Sucralose as an Indicator Compound of Wastewater Loading to Surface Waters in Urbanized Regions. Water Res 2011, 45, 4019–4027. [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Gawlik, B.M.; Boettcher, K.; Locoro, G.; Contini, S.; Bidoglio, G. Sucralose Screening in European Surface Waters Using a Solid-Phase Extraction-Liquid Chromatography–Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry Method. J Chromatogr A 2009, 1216, 1126–1131. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Thurman, E.M. Analysis of Sucralose and Other Sweeteners in Water and Beverage Samples by Liquid Chromatography/Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2010, 1217, 4127–4134. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; O’Brien, J.W.; Tscharke, B.J.; Choi, P.M.; Zheng, Q.; Ahmed, F.; Thompson, J.; Li, J.; Mueller, J.F.; Sun, H.; et al. National Wastewater Reconnaissance of Artificial Sweetener Consumption and Emission in Australia. Environ Int 2020, 143, 105963. [CrossRef]

- Mawhinney, D.B.; Young, R.B.; Vanderford, B.J.; Borch, T.; Snyder, S.A. Artificial Sweetener Sucralose in U.S. Drinking Water Systems. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 8716–8722. [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, M.G.; Katz, D.R.; Sullivan, J.C.; Shapley, D.; Lipscomb, J.; Epstein, J.; Juhl, A.R.; Knudson, C.; O’Mullan, G.D. Spatial Patterns of Pharmaceuticals and Wastewater Tracers in the Hudson River Estuary. Water Res 2018, 137, 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Soh, L.; Connors, K.A.; Brooks, B.W.; Zimmerman, J. Fate of Sucralose through Environmental and Water Treatment Processes and Impact on Plant Indicator Species. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 1363–1369. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, A.K.E.; Guo, X.; Gorokhova, E. Cardiotoxic and Neurobehavioral Effects of Sucralose and Acesulfame in Daphnia: Toward Understanding Ecological Impacts of Artificial Sweeteners. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology 2023, 273. [CrossRef]

- Saputra, F.; Lai, Y.H.; Fernandez, R.A.T.; Macabeo, A.P.G.; Lai, H.T.; Huang, J.C.; Hsiao, C. Der Acute and Sub-Chronic Exposure to Artificial Sweeteners at the Highest Environmentally Relevant Concentration Induce Less Cardiovascular Physiology Alterations in Zebrafish Larvae. Biology 2021, Vol. 10, Page 548 2021, 10, 548. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, A.K.E.; Breitholtz, M.; Bengtsson, B.E.; Adolfsson-Erici, M. Sucralose – An Ecotoxicological Challenger? Chemosphere 2012, 86, 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Heredia-García, G.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Orozco-Hernández, J.M.; Luja-Mondragón, M.; Islas-Flores, H.; SanJuan-Reyes, N.; Galar-Martínez, M.; García-Medina, S.; Dublán-García, O. Alterations to DNA, Apoptosis and Oxidative Damage Induced by Sucralose in Blood Cells of Cyprinus Carpio. Sci Total Environ 2019, 692, 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Pandaram, A.; Paul, J.; Wankhar, W.; Thakur, A.; Verma, S.; Vasudevan, K.; Wankhar, D.; Kammala, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Jaganathan, R.; et al. Aspartame Causes Developmental Defects and Teratogenicity in Zebra Fish Embryo: Role of Impaired SIRT1/FOXO3a Axis in Neuron Cells. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 855. [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Li, X.; Han, G.; Du, L.; Li, M. Zebrafish Neuro-Behavioral Profiles Altered by Acesulfame (ACE) within the Range of “No Observed Effect Concentrations (NOECs)”. Chemosphere 2019, 243, 125431–125431. [CrossRef]

- Perkola, N. Fate of Artificial Sweeteners and Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Aquatic Environment. 2014.

- Colín-García, K.; Elizalde-Velázquez, G.A.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Islas-Flores, H.; García-Medina, S.; Galar-Martínez, M. Acute Exposure to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Sucralose Disrupts Embryonic Development and Leads to an Oxidative Stress Response in Danio Rerio. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154689. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Geng, J.; Li, F.; Ren, H.; Ding, L.; Xu, K. The Oxidative Stress in the Liver of Carassius Auratus Exposed to Acesulfame and Its UV Irradiance Products. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 571, 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rojas, C.; SanJuan-Reyes, N.; Fuentes-Benites, M.P.A.G.; Dublan-García, O.; Galar-Martínez, M.; Islas-Flores, H.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M. Acesulfame Potassium: Its Ecotoxicity Measured through Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio). Science of The Total Environment 2019, 647, 772–784. [CrossRef]

- Ferry Saputra; Lai, Y.-H.; Fernandez, R.A.; Macabeo, A.P.G.; Lai, H.-T.; Huang, J.-C.; Hsiao, C.-D. In Vivo Modelling of Toxicity of Eight Commercial Artificial Sweeteners in Daphnia Neonates and Zebrafish Embryos through Cardiac Performance Assessments. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Evaluation of Aspartame Effects at Environmental Concentration on Early Development of Zebrafish: Morphology and Transcriptome1. Environmental Pollution 2024, 361, 124792. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, G.; Han, G.; Du, L.; Li, M. Zebrafish Behavioral Phenomics Links Artificial Sweetener Aspartame to Behavioral Toxicity and Neurotransmitter Homeostasis. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 15393–15402. [CrossRef]

- Kobetičová, K.; Mocová, K.A.; Mrhálková, L.; Fryčová, Z.; Kočí, V. Artificial Sweeteners and the Environment. Czech Journal of Food Sciences 2016, 34, 149–153. [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Han, G.; Li, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Li, M. Phenotyping Aquatic Neurotoxicity Induced by the Artificial Sweetener Saccharin at Sublethal Concentration Levels. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 2041–2050. [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Vence, K.; Elizalde-Velázquez, A.; Dublán-García, O.; Galar-Martínez, M.; Islas-Flores, H.; SanJuan-Reyes, N.; García-Medina, S.; Hernández-Navarro, M.D.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M. Toxicological Hazard Induced by Sucralose to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations in Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio). Science of the Total Environment 2017, 575, 347–357. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson Wiklund, A.K.; Adolfsson-Erici, M.; Liewenborg, B.; Gorokhova, E. Sucralose Induces Biochemical Responses in Daphnia Magna. PLoS One 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, A.K.E.; Breitholtz, M.; Bengtsson, B.E.; Adolfsson-Erici, M. Sucralose – An Ecotoxicological Challenger? Chemosphere 2012, 86, 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, M.; Hansen, J.H.; Camus, L. Short-Term Effects of Sucralose on Calanus Finmarchicus and Calanus Glacialis in Disko Bay, Greenland. Chemistry and Ecology 2010, 26, 385–393. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).