Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

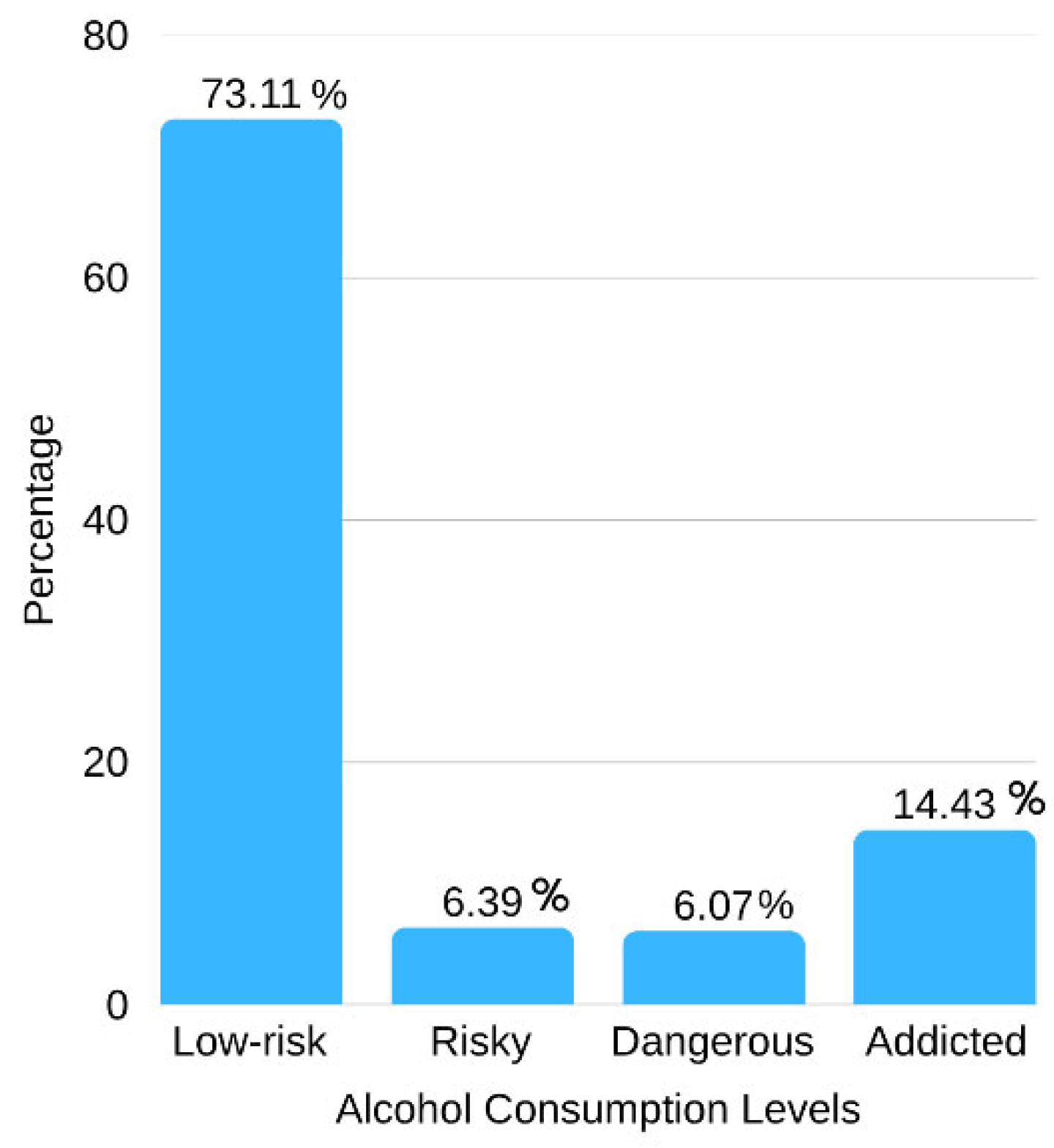

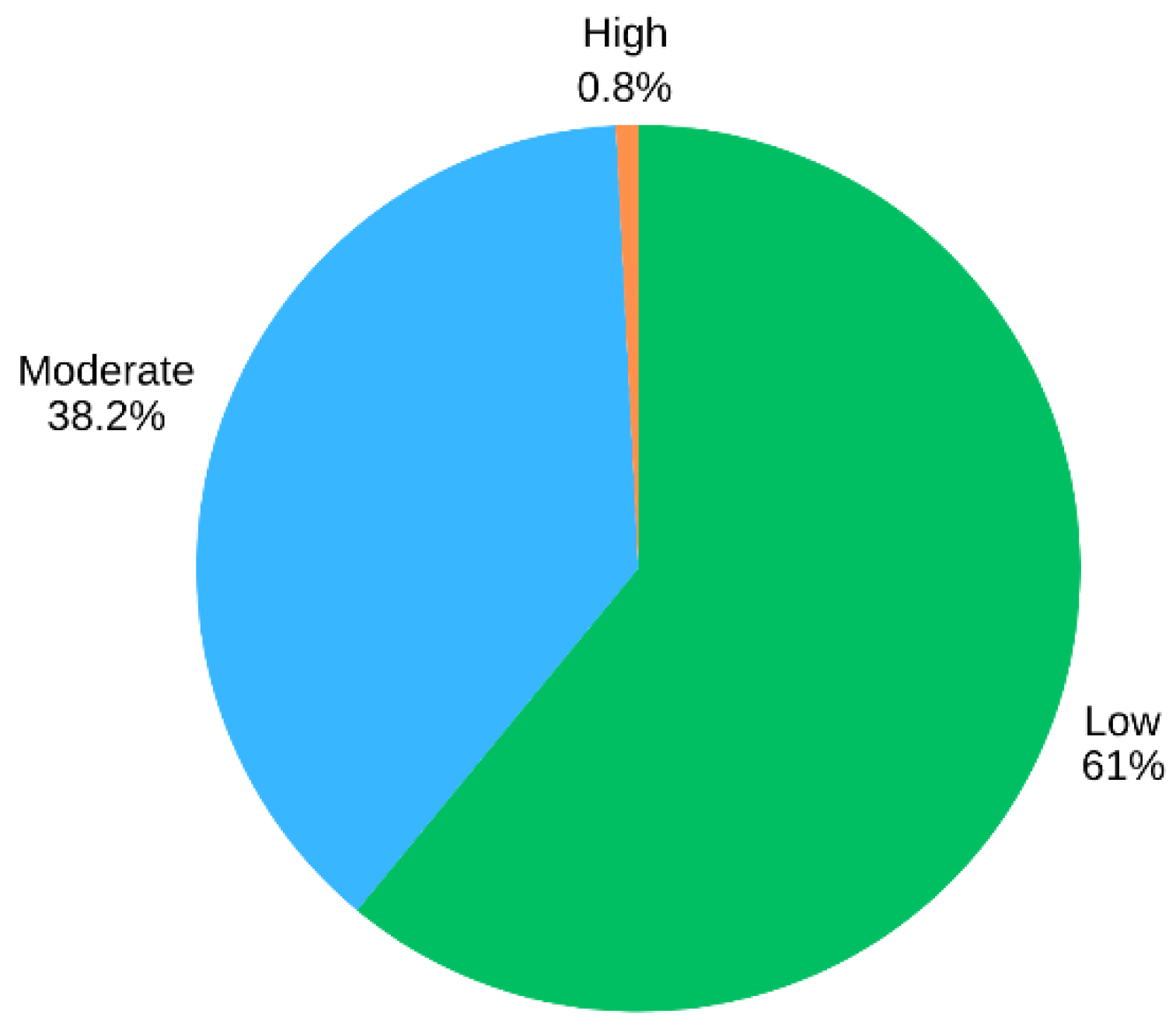

Background: Alcohol use poses significant health and social risks among migrant workers, yet limited research explores how various factors interact to shape its impact. Methods: This cross-sectional study surveyed 610 Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand (Sep 2023–Mar 2024) using multi-stage random sampling. Paper-based questionnaires assessed alcohol-related outcomes, and generalized linear mixed models identified associated factors. Results: Among the participants, 38.20% reported a moderate level of impact from alcohol consumption (95% CI: 34.41–42.12), while 0.82% reported a high level of impact (95% CI: 0.34–1.95). Alcohol addiction significantly increased the likelihood of adverse health, family, and social outcomes (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.70 [1.61–1.79]). Rural workers were disproportionately affected compared to urban workers (6.52 [4.35–9.77]). The risk was also heightened by housing problems (5.00 [2.70–9.24]). Other significant covariates included poor sleep quality (2.09 [1.51–2.90]), moderate/poor health (2.11 [2.02–2.22]), longer work hours (2.39 [1.02–5.60]), daily work schedules (2.39 [1.64-3.49]), and strained co-worker relationships (1.89 [1.88–1.90]). Conclusions: Alcohol-related harms among migrant workers are shaped by environmental and occupational stressors. Primary care and community health systems should integrate screening, targeted health promotion, and culturally appropriate support services to reduce harm and promote well-being.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design, Sampling and Participants

2.2. Research Instrument and Validity

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Crude OR | Crude Odds ratio |

| Adj. OR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| 95% CI | 95% Confidence interval |

| AUDIT | Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test |

| GLMM | Generalized Linear Mixed Model |

References

- Ramos-Vera, C.; Serpa Barrientos, A.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E.; Carvajal Guillen, C.; Saintila, J. Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages Associated With Physical Health Status in Adults: Secondary Analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey Data. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319211066205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Alcohol. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Balagopal, G.; Davidson, S.; Gill, S.; Barengo, N.; De La Rosa, M.; Sanchez, M. The impact of cultural stress and gender norms on alcohol use severity among Latino immigrant men. Ethnicity and Health 2022, 27, 1271–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Kang'ethe, M. The Nexus between Ramifications of Alcohol Abuse and Work Productivity (The Case of East London 2020 Research Study Participants). Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research 2022, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, L.H.; Nunes, F.; Dominguez, M.B. “Enhancers” and “copers”? Understanding drinking motives and alcohol use among international workers. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 2022, 21, 1361–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, D.; Shwe, V.D.T.; Bajcevic, P.; Gagnon, A. Alcohol use disorders among Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 2019, 15, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.N.N.; Shirayama, Y.; Moolphate, S.; Lorga, T.; Yuasa, M.; Aung, M.N. Acculturation and its effects on health risk behaviors among Myanmar migrant workers: a cross-sectional survey in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangsinsiri, C.; Youngkong, S.; Chaikledkaew, U.; Pattanaprateep, O.; Thavorncharoensap, M. Economic costs of alcohol consumption in Thailand, 2021. Global Health Research and Policy 2023, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Public Health of Thailand. Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in Thailand. Available online: https://thailand.un.org/en/159788-prevention-and-control-noncommunicable-diseases-thailand-%E2%80%93-case-investment (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Racal, S.J.; Sitthimongkol, Y.; Prasopkittikun, T.; Punpuing, S.; Chansatitporn, N.; Strobbe, S. , Factors influencing alcohol use among Myanmar young migrant workers in Thailand. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research 2020, 24, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Noosorn, N.; Phetpoom, J.; Yau, S.; Choudhury Robin, R. Prevalence and determinants of alcohol consumption behavior of migrant workers in the communities of the Lower Northern Region of Thailand. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339587001_Prevalence_and_Determinants_of_Alcohol_Consumption_Behavior_of_Migrant_Workers_in_the_Communities_of_the_Lower_Northern_Region_of_Thailand (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Britto, D.R.; Catherin, N.; Mathew, T.; Navshin, S.; Kurian, H.; Sherrin, S.; Goud, B.R.; Shanbhag, D. Alcohol use and mental health among migrant workers. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development 2016, 7, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pavarin, R.M.; Fioritti, A.; Fabbri, C.; Sanchini, S.; Ronchi, D.D. , Comparison of Mortality Rates between Italian and Foreign-born Patients with Alcohol Use Disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2022, 54, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, E.L.; Bailey, J.; Hyett, S.; Sedighi, S.; Snoo, M.L. d.; Williams, K.; Barry, R.; Erickson, A.; Foroutan, F.; Selby, P.; Rosella, L.; Kurdyak, P. Hazardous alcohol use and alcohol-related harm in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. The Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e177–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanri, L.; Mude, W. Alcohol, Other Drugs Use and Mental Health among African Migrant Youths in South Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organista, K.C.; Jung, W.; Neilands, T.B. A structural-environmental model of alcohol and substance-related sexual HIV risk in Latino migrant day laborers. AIDS and Behavior 2020, 24, 3176–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, H.; Larsen, J.; Catterall, E.; Moss, A.C.; Dombrowski, S.U. Peer pressure and alcohol consumption in adults living in the UK: a systematic qualitative review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AshaRani, P.V.; Sin, K.Y.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Shafie, S.; Shahwan, S.; Chang, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Subramaniam, M. The Relationship of Socioeconomic Status to Alcohol, Smoking, and Health: a Population-Level Study of the Multiethnic Population in Singapore. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2024, 22, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, A.D.; Morgillo, T.; Rossi, A.; Ventura, M.; Nosotti, L.; Cavani, A.; Costanzo, G.; Mirisola, C.; Petrelli, A. Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated with Harmful Use of Alcohol Among Economically and Socially Disadvantaged Immigrant Patients in Italy. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2020, 22, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44489 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Sharma, S.R.; Matheson, A.; Lambrick, D.; Faulkner, J.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Vaidya, A.; Page, R. The role of tobacco and alcohol use in the interaction of social determinants of non-communicable diseases in Nepal: A systems perspective. BMC Public Health 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J. Alcohol use among Latino migrant workers in South Florida. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2015, 151, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, F.Y.; Bloch, D.A.; Larsen, M.D. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine 1998, 17, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.P.; Sutherland, I.; Newcombe, R.G. Relations between alcohol, violence and victimization in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 2006, 29, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-U. ; Jong-Uk Won; Yoon, J.-H., Association between weekly working hours and risky alcohol use: a 12-year longitudinal, nationwide study from South Korea. Psychiatry Research 2023, 326, 115325. [Google Scholar]

- Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. AUDIT-The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary heath care. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309309791_AUDIT-The_Alcohol_Use_Disorders_Identification_Test_Guidelines_for_Use_in_Primary_Heath_Care_Second_Edition (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Kiess, H.; Green, B.A. Statistical concepts for the behavioral sciences., 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R.K.; Eignor, D.R. Guidelines for evaluating criterion-referenced tests and test manuals. Journal of Educational Measurement 1978, 15, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- David, W.; Hosmer, J.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression., 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Toronto, Canada, 2013; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.K.; Trinidad, N.; Correa, A.; Carlo, G. Correlates and predictors of alcohol consumption and negative consequences of alcohol use among Latino migrant farmworkers in Nebraska. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, M.; Gómez Carpinteiro, F. , The effects of problem drinking and sexual risk among mexican migrant workers on their community of origin. Human Organization 2009, 68, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, E.L.; Bailey, J.; Hyett, S.; Sedighi, S.; de Snoo, M.L.; Williams, K.; Barry, R.; Erickson, A.; Foroutan, F.; Selby, P.; Rosella, L.; Kurdyak, P. Hazardous alcohol use and alcohol-related harm in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. The Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e177–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.N.; O’Neill, S.E. Treatment of Alcohol Use Problems Among Rural Populations: a Review of Barriers and Considerations for Increasing Access to Quality Care. Current Addiction Reports 2022, 9, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Jin, L. Emptying villages, overflowing glasses: Out-migration and drinking patterns in Rural China. Journal of Migration and Health 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carceles, M.D.; Medina, M.D.; Perez-Flores, D.; Noguera, J.A.; Pereniguez, J.E.; Madrigal, M.; Luna, A. Screening for hazardous drinking in migrant workers in Southeastern Spain. Journal of Occupational Health 2014, 56, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludlow, T.; Fooken, J.; Rose, C.; Tang, K.K. Housing insecurity, financial hardship and mental health. Economics and Human Biology 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, M.; Buckle, C.; Rugel, E.; Donohoe-Bales, A.; McGrath, L.; Gournay, K.; Barrett, E.; Phibbs, P.; Teesson, M. ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. International Journal of Housing Policy 2023, 23, 260–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.; Lai, R.Y.S.; Hoi, B.; Li, M.Y.Y.; Chan, J.H.Y.; Sin, H.H.F.; Chung, E.S.K.; Cheung, R.T.Y.; Wong, E.L.Y. The effect of dwelling size on the mental health and quality of life of female caregivers living in informal tiny homes in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeno, T.; Tatsuse, T.; Sekine, M.; Yamada, M. A longitudinal study of the influence of work characteristics, work–family status, and social activities on problem drinking: the Japanese civil servants study. Industrial Health 2024, 62, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.K.; Sedivy, S.K.; Cisler, R.A. The influence of work environment stressors and individual social vulnerabilities on employee problem drinking. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 2009, 9, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, N.; Assanangkornchai, S.; Rajbhandari, I. Does husband's alcohol consumption increase the risk of domestic violence during the pregnancy and postpartum periods in Nepalese women? BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Pirmohamed, M. Associations between occupation and heavy alcohol consumption in UK adults aged 40–69 years: a cross-sectional study using the UK Biobank. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.A.; Omdahl, B.L.; Fritz, J.M.H. Turning points in relationships with disliked co-workers. Available online: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/cmm_fac_pub/7/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Morrison, R.L. Negative relationships in the workplace: associations with organisational commitment, cohesion, job satisfaction and intention to turnover. Journal of Management & Organization 2008, 14, 330–344. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, D.R.; Jason, L.A.; Davis, M.I.; Olson, B.D.; Ferrari, J.R. Friends, family, and alcohol abuse: an examination of general and alcohol-specific social support. The American Journal on Addictions 2007, 16, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M.M.; Skogen, J.C.; Bonsaksen, T.; Skarpaas, L.S.; Aas, R.W. Are workplace factors associated with employee alcohol use? The WIRUS cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravorty, S.; Kember, R.L.; Mazzotti, D.R.; Dashti, H.S.; Toikumo, S.; Gehrman, P.R.; Kranzler, H.R. The relationship between alcohol- and sleep-related traits: results from polygenic risk score and Mendelian randomization analyses. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2023, 251, 110912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, A.; fat, L. n.; neligan, A. The association between alcohol consumption and sleep disorders among older people in the general population. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AshaRani, P.V.; Karuvetil, M.Z.; Brian, T.Y.W.; Satghare, P.; Roystonn, K.; Peizhi, W.; Cetty, L.; Zainuldin, N.A.; Subramaniam, M. Prevalence and correlates of physical comorbidities in Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD): a pilot study in treatment-seeking population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buneviciene, I.; Bunevicius, R.; Bagdonas, S.; Bunevicius, A. The impact of pre-existing conditions and perceived health status on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health 2022, 44, e88–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | Number | Percentage |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 159 | 26.07 |

| Male | 451 | 73.93 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 19 | 18 | 2.95 |

| 20–29 | 187 | 30.66 |

| 30–39 | 239 | 39.18 |

| 40–59 | 147 | 24.10 |

| ≥ 60 | 19 | 3.11 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 34.80 (10.61) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 33 (18–73) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 208 | 34.10 |

| Married (with a marriage certificate) | 217 | 35.57 |

| Married (without a marriage certificate) | 136 | 22.30 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 49 | 8.03 |

| Highest education level | ||

| No formal education | 33 | 5.41 |

| Primary school | 180 | 29.51 |

| Lower secondary school | 187 | 30.66 |

| High school or equivalence | 153 | 25.08 |

| Diploma or equivalence | 44 | 7.21 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 13 | 2.13 |

| Main occupational group | ||

| Fishing sector | 235 | 38.52 |

| Service industry sector | 153 | 25.08 |

| Agriculture and animal feeding sector | 114 | 18.69 |

| Construction sectors | 43 | 7.05 |

| Household | 39 | 6.40 |

| Manufacturing industry sector | 7 | 1.15 |

| Others | 19 | 3.11 |

| Average monthly income (baht/month) | ||

| None | 15 | 2.46 |

| < 7,500 | 37 | 6.07 |

| 7,500–9,999 | 224 | 36.72 |

| 10,000–12,499 | 227 | 37.21 |

| ≥ 12,500 | 107 | 17.54 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 10,195.41 (3,169.76) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 10,000 (0–21,000) | |

| Average monthly expenditure (baht/month) | ||

| None | 15 | 2.46 |

| < 2,500 | 35 | 5.74 |

| 2,500–4,999 | 110 | 18.03 |

| 5,000–7,499 | 355 | 58.19 |

| ≥ 7,500 | 95 | 15.67 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 5,457.37 (2,099.68) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 5,000 (0–12,000) | |

| Financial status | ||

| Not enough and debt | 94 | 15.41 |

| Not enough and not debt | 143 | 23.44 |

| Enough but not saving | 225 | 36.89 |

| Enough and saving | 148 | 24.26 |

| Live in province | ||

| Songkhla | 240 | 39.34 |

| Surat Thani | 370 | 60.66 |

| Worked in Thailand (years) | ||

| < 2 | 100 | 16.39 |

| 2–5 | 234 | 38.36 |

| 6–10 | 161 | 26.40 |

| > 10 | 115 | 18.85 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 6.71 (6.30) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 5 (0.08–36) | |

| Status of migrant | ||

| Illegal | 59 | 9.67 |

| Legal | 551 | 90.33 |

| Health insurance | ||

| No | 83 | 13.61 |

| Yes | 527 | 86.39 |

| Working hours per day (hours) | ||

| No job | 14 | 2.30 |

| ≤ 8 | 466 | 76.39 |

| > 8 | 130 | 21.31 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 8.18 (1.64) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 8 (0–15) | |

| Working days per week (days) | ||

| No job | 14 | 2.30 |

| ≤ 6 | 507 | 83.11 |

| Everyday | 89 | 14.59 |

| Mean (Standard deviation) | 5.88 (1.10) | |

| Median (Min–Max) | 6 (0–7) | |

| Worked part-time | ||

| Never | 417 | 68.36 |

| Yes | 193 | 31.64 |

| Annual health checkup during work | ||

| Never | 161 | 26.39 |

| Yes | 449 | 73.61 |

| Health behavior, physical health, and health information | Number | Percentage |

| Meals per day in past month | ||

| < 3 | 131 | 21.48 |

| 3 | 450 | 73.77 |

| > 3 | 29 | 4.75 |

| Exercise in past month | ||

| No | 227 | 37.21 |

| Yes | 383 | 62.79 |

| Problems with not sleeping well | ||

| No | 259 | 42.46 |

| Yes | 351 | 57.54 |

| Tobacco used | ||

| Non-smoker | 390 | 63.93 |

| Former smoker | 17 | 2.79 |

| Smoker | 203 | 33.28 |

| Physical health | ||

| Not strong | 5 | 0.82 |

| Moderate | 229 | 37.54 |

| Strong | 376 | 61.64 |

| Chronic illness | ||

| No | 511 | 83.77 |

| Yes | 99 | 16.23 |

| Received health-related information | ||

| No | 230 | 37.70 |

| Yes | 380 | 62.30 |

|

Received health information materials in Myanmar language |

||

| No | 174 | 28.52 |

| Yes | 436 | 71.48 |

| Environment and relationship factors | Number | Percentage |

| Type of community | ||

| Myanmar workers community | 323 | 52.95 |

| Urban community | 148 | 24.26 |

| Rural community | 100 | 16.39 |

| Semi-urban, semi-rural community | 37 | 6.07 |

| Others | 2 | 0.33 |

| Type of residence | ||

| Worker camp | 447 | 73.28 |

| Shared rental house | 88 | 14.43 |

| Detached rental house | 66 | 10.82 |

| Apartment | 5 | 0.82 |

| Others | 4 | 0.66 |

| Live with | ||

| Family | 397 | 65.08 |

| Friend | 168 | 27.54 |

| Alone | 43 | 7.05 |

| Others | 2 | 0.33 |

| Environmental problems in housing | ||

| Low | 548 | 89.84 |

| Moderate | 57 | 9.34 |

| High | 5 | 0.82 |

| Nature of workplace | ||

| Outdoor | 213 | 34.91 |

| Both outdoor and indoor | 187 | 30.66 |

| Indoor | 182 | 29.84 |

| Others | 28 | 4.59 |

| Environmental problems in workplace | ||

| Low | 560 | 91.80 |

| Moderate | 50 | 8.20 |

| High | 0 | 0 |

| Perceived relationship with neighbors | ||

| Poor | 49 | 8.03 |

| Moderate | 308 | 50.49 |

| Good | 253 | 41.48 |

| Perceived relationship with workmates | ||

| Poor | 48 | 7.87 |

| Moderate | 287 | 47.05 |

| Good | 275 | 45.08 |

| Perceived relationship with family | ||

| Poor | 44 | 7.21 |

| Moderate | 219 | 35.90 |

| Good | 347 | 56.89 |

| Perceived relationship with employer | ||

| Poor | 52 | 8.52 |

| Moderate | 259 | 42.46 |

| Good | 299 | 49.02 |

| Factors | Number | % Moderate-high impact | Crude OR |

Adj. OR |

95% CI | p value |

| Level of alcohol consumption and environmental factors | ||||||

| Level of alcohol consumption | 0.020 | |||||

| Low-risk drinker | 446 | 34.30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Risky–dangerous drinker | 76 | 38.16 | 1.18 | 1.65 | 1.08–2.52 | |

| Addicted to drinking | 88 | 63.64 | 3.35 | 1.70 | 1.61–1.79 | |

| Type of community | < 0.001 | |||||

| Urban community | 148 | 11.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Myanmar workers community | 323 | 40.25 | 5.19 | 1.31 | 1.20–1.42 | |

| Rural community or other | 139 | 65.47 | 14.60 | 6.52 | 4.35–9.77 | |

| Environmental problems in housing | < 0.001 | |||||

| Low | 548 | 34.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Moderate/high | 62 | 79.03 | 7.15 | 5.00 | 2.70–9.24 | |

| Other covariates | ||||||

| Period of work (hours per day) | 0.044 | |||||

| ≤ 8 | 480 | 30.83 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| > 8 | 130 | 69.23 | 5.04 | 2.39 | 1.02–5.60 | |

| Amount of time to work (day/week) | <0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 6 | 521 | 33.01 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Everyday | 89 | 74.16 | 5.82 | 2.39 | 1.64–3.49 | |

| Problems with not sleeping well | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 259 | 25.10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 351 | 49.29 | 2.90 | 2.09 | 1.51–2.90 | |

| Physical health | <0.001 | |||||

| Strong | 376 | 25.80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Not strong/moderate | 234 | 60.26 | 4.36 | 2.11 | 2.02–2.22 | |

| Relationships with co-workers | <0.001 | |||||

| Good | 275 | 30.91 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Moderate/poor | 335 | 45.67 | 1.87 | 1.89 | 1.88–1.90 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).