1. Introduction

1.1. Vanadium Catalysts

Vanadium catalysts have played a significant role in the development of industrial technologies for processing chemical compounds for decades. They are used in sulfuric acid production [

1,

2], biomass transformation [

3], biodiesel production [

4], and in oxidation, dehydrogenation, or oxidative dehydrogenation of hydrocarbons [

5,

6,

7,

8], as well as in the removal of NOx from effluent gases [

9,

10], among other applications. However, extensive studies and environmental monitoring have determined that vanadium catalysts can no longer be used in certain applications. Due to their high toxicity and susceptibility to sublimation [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], vanadium-containing catalysts, especially those with higher oxidation states, have been banned from use in mobile pollution sources.

Vanadium-containing catalysts, in particular Mg-V-O mixed oxides, have been studied for many years as efficient catalysts for the conversion of alkanes to the corresponding alkenes [

17]. These catalysts are usually obtained by impregnation of Mg-containing supports with a solution of vanadium salts or by a solid-state reaction between magnesia and vanadia [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Another possible route is the calcination of V-containing hydrotalcite-like precursors [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

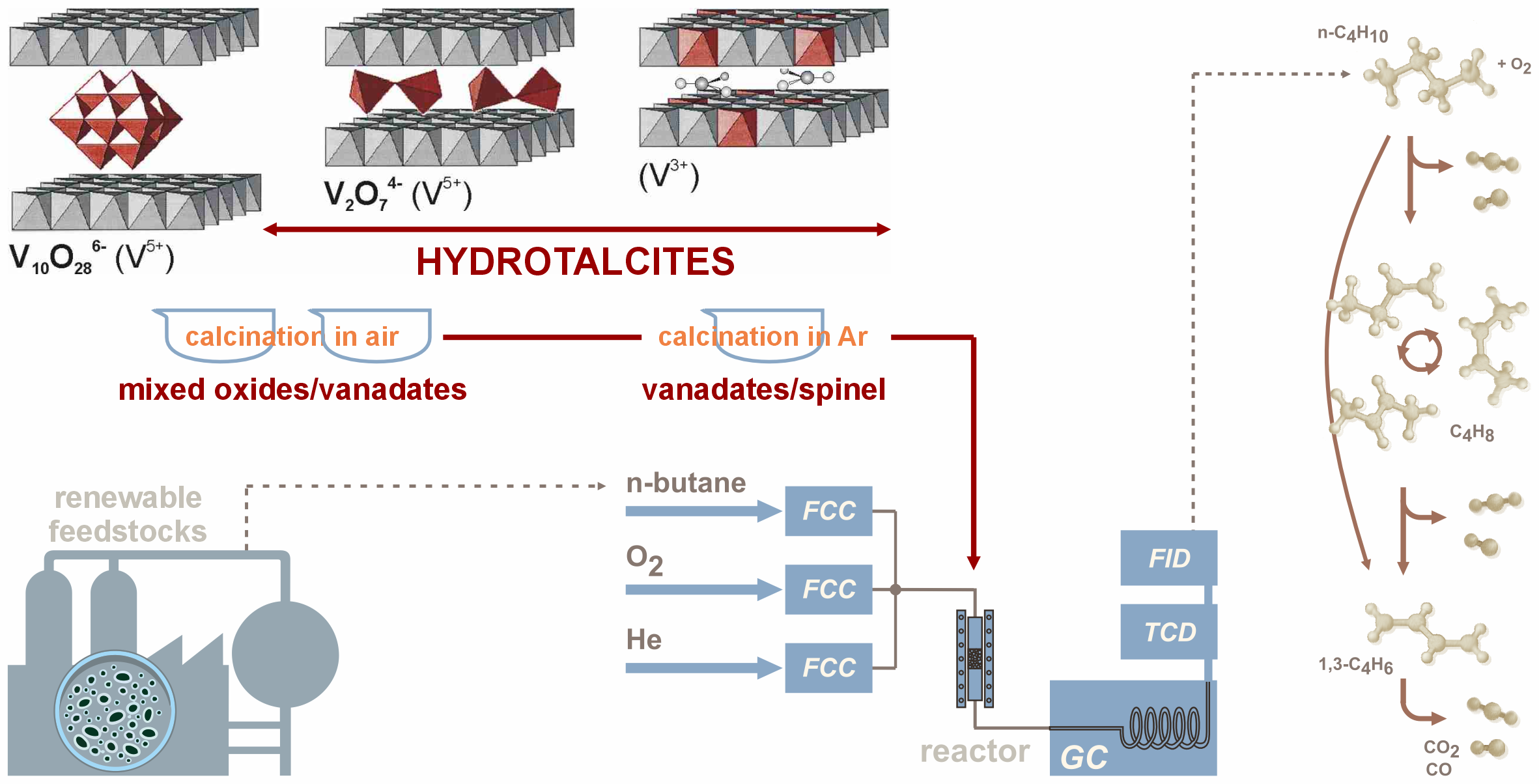

Layered double hydroxides, known as hydrotalcites, consist of brucite-like layers in which part of the divalent cations (M

2+) is substituted by trivalent ones (M

3+). The resulting excess positive charge is balanced by hydrated anions (A

n-) located between the layers. Thus, the general formula of hydrotalcites (HTs) can be expressed as:

The chemical composition of these materials can be varied over a wide range by substituting metal cations (e.g., Cu

2+, Ni

2+, Zn

2+, Fe

3+, Cr

3+) or interlayer anions (e.g., . Cr

2O

72-, Mo

7O

246-, V

2O

74-) [

29,

30,

31,

32]. In the present work, doping within the brucite-like sheets with V

3+, as well as interlayer modification by introducing vanadates (V

5+), was applied to obtain V-containing Mg-Al hydrotalcite-like precursors. These were subsequently converted into V-containing catalysts with varying vanadium contents and oxidation states. Maintaining a lower oxidation state was intended to achieve higher catalytic activity while reducing harmful emissions. Furthermore, the use of a hydrotalcite precursor was aimed at increasing vanadium dispersion, thereby preventing excessive sintering, phase segregation, and ultimately the formation of vanadium oxide clusters. Hydrotalcite precursors are considered cheap, easy to prepare in the laboratory, extremely flexible in terms of composition modification and enabling the properties of the catalysts obtained from them to be adjusted [

29].

1.2. Beyond Fossil Fuels - Transition into Circular Economy

Despite limitations arising from harmful emissions, the use of vanadium catalysts in closed installations still offers significant advantages. Such catalysts can support the transition to a circular economy not only through their role in pollutant removal [

33,

34] or the potential for catalyst recycling [

35,

36,

37], but also through their application in processes where fossil fuels can be replaced by renewable raw materials [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Consequently, increasing research attention is being devoted to the production of alternative fuels (e.g., biodiesel) and the processing of industrial, agricultural, forestry, food or plastic waste [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

A circular economy aims to close material loops by transforming waste streams into value-added products [

47,

48,

49]. Producing butane, a key chemical feedstock and fuel, from renewable resources offers both environmental and economic benefits, as it reduces reliance on fossil fuels while valorizing organic waste. Traditionally, n-butane is obtained from petroleum via distillation, but its green analog, biobutane (renewable butane), can be generated through the conversion of biomass or organic residues. Although n-butane production is not as extensively developed as n-butanol fermentation, several studies demonstrate the feasibility of this process. Therefore, butane, selected here as a model molecule, can be considered part of a growing group of renewable materials. The bioeconomy, including biorefineries, is increasingly promoted as a fundamental element of the circular economy, with waste from various origins, particularly food-processing residues, serving as the preferred raw material [

50].

Processes for producing bio-LPG blends or alternative fuels are highly valued and actively investigated. These typically require engineered microbial strains capable of operating efficiently under relevant conditions. For example, butyric acid from waste biomass has been used as a carbon source for microbial fuel production [

51].

Halomonas, a robust extremophilic microbial chassis, can operate in non-sterile environments to convert organic compounds into a gaseous alkane mixture. Ideally, microbial fermentation-based bio-LPG production systems could be tuned to control the propane-to-butane ratio according to market needs. Alternative biosynthetic pathways have also been proposed, such as producing propane, isobutane, and n-butane from the amino acids valine, leucine, and isoleucine, respectively, using engineered

E. coli.

The strong demand for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and the pressure to decarbonize energy systems have incentivized the development of both biological and chemical production routes. In addition to microbial conversion, chemical processes play a significant role in maximizing production and waste valorization [

52]. Bio-LPG can be produced as either a main product or a by-product in processes such as hydrotreating or dehydrogenating bio-oils, glycerol hydrolysis and fermentation, gas-phase conversion and synthesis from cellulose or organic waste, as well as in more energy-intensive methods like gasification and pyrolysis.

Compared with bioethanol and biodiesel, microbial alkane/alkene production still suffers from low yields, limiting industrial scalability. Nevertheless, microorganisms such as

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and

Escherichia coli have been tested for alkane production using glucose, fatty acids, and aldehydes as carbon sources [

53]. Additionally, certain newly isolated strains from natural habitats show exceptional performance, for instance,

Aureobasidium melanogenum was reported to be 30% more efficient in alkane/alkene production when grown on inulin.

Selective production of n-butane from renewable carbon sources has also been achieved in model-assisted, two-stage fermentation processes [

54]. Here, engineered enzymes converted acetate, produced via electrocatalytic CO reduction, into n-butane, with a modified

E. coli strain increasing n-butane titers by 168-fold (from 0.04 to 6.74 mg/L). In another example, levulinic acid (LA), a bio-based platform chemical, was transformed over a base-treated Pt/C catalyst in a one-step reaction yielding 95.5% n-butane via hydrodeoxygenation of LA to valeric acid (VA), followed by VA decarboxylation [

55].

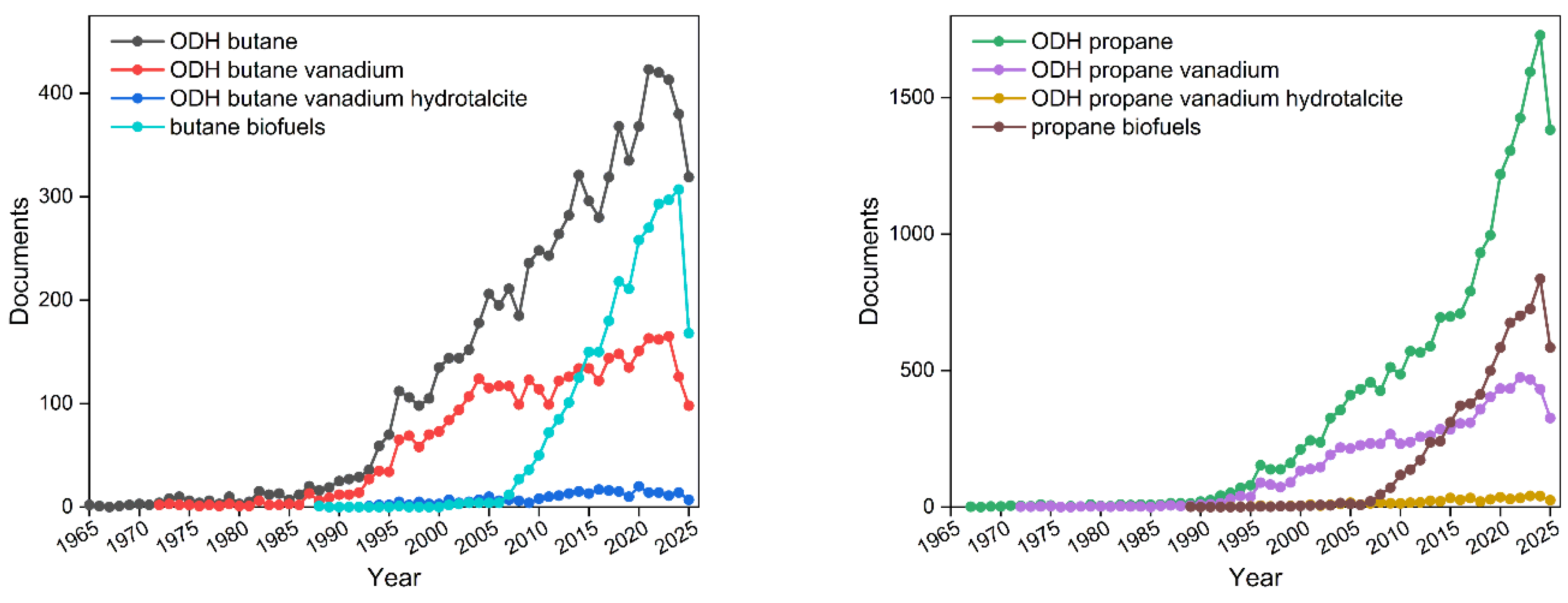

The increasing number of studies on biofuel production highlights the growing interest in efficient processes for n-butane oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH). Literature trends (

Figure 1) indicate that dehydrogenation of propane and butane was most intensively studied in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Over the past two decades, however, research interest has shifted toward bio-based production of propane and butane as renewable feedstocks for further transformations, alongside continuing investigation into vanadium-based catalysts.

2. Materials and Methods

The parent Mg-Al hydrotalcites containing either carbonates or nitrates as compensating anions were prepared using a standard co-precipitation method at constant pH. A solution of Mg(NO3)2 . 6 H2O (51.2 g, 0.2 mol) and Al(NO3)3 . 9 H2O (37.5 g, 0.1 mol) in 200 cm3 of distilled water was added dropwise to 100 cm3 of H2O or an aqueous solution of Na2CO3 (6.6 g, 0.06 mol) to obtain nitrate (NV0) or carbonate (CV0) hydrotalcites, respectively. Co-precipitation was carried out at 60 °C under vigorous stirring at pH = 10.0 ± 0.2, controlled by simultaneous addition of a 10% aqueous NaOH solution. The suspensions were stirred for 1 h at 60 °C.

The same conditions were applied for the direct co-precipitation of a vanadate-intercalated Mg-Al hydrotalcite, except that Mg and Al salts were added to an aqueous solution containing 0.40 mol of V2O74- (sample DV13).

The parent hydrotalcites were subjected to ion exchange at pH = 4.5 (CV0) or 9.5 (CV0 and NV0). The pH of an approximately 5% hydrotalcite suspension was adjusted using HNO₃ (1:10) or a 10% NaOH solution, followed by the addition of an appropriate vanadate solution in 25% excess. The vanadate solution was prepared by dissolving 11.7 g of NaVO3 . H2O in 280 cm3 of H₂O and adjusting the pH to 4.5 for decavanadate or 9.5 for pyrovanadate. The total time for addition and aging at 60 °C was 1 h at pH = 4.5 and 2 h at pH = 9.5. The decavanadate-exchanged sample was denoted CV25, while the pyrovanadate-exchanged sample was denoted NV12. Another sample with pyrovanadates adsorbed on the surface at pH = 9.5 was denoted CV3.

At constant pH = 9.0 ± 0.2, two samples doped with V3+ were obtained. For sample AV18, a mixture of MgCl2 . 6 H2O (13.2 g, 0.06 mol) and VCl3 (5.1 g, 0.03 mol) was used, for sample AV8, a mixture of MgCl2 . 6 H2O (13.8 g, 0.07 mol), AlCl3 . 6 H2O (5.5 g, 0.01 mol), and VCl3 (1.8 g, 0.02 mol) was used. In each case, the salts were dissolved in 65 cm3 of deionized H2O and added dropwise at room temperature to 100 cm3 of Na2CO3 solution (3.6 g, 0.05 mol). A 10% aqueous NaOH solution was used to maintain pH. Both samples were subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 150 °C for 6 days under autogenous pressure in the mother solution.

After short aging or aging followed by hydrothermal treatment, the suspensions were filtered, washed with distilled water, and dried in air at 60 °C for 18 h, or in argon at 40 °C for 24 h for the V3+-doped samples. An inert atmosphere (Ar) was also applied during the calcination of samples containing reduced vanadium cations, while other samples were thermally treated in static air. Calcination was carried out at 700 °C for 13 h. To distinguish hydrotalcite precursors from mixed oxides, the letter “c” was added to the names of the calcined samples. The number in the sample name indicates the vanadium content (wt%) in the mixed oxide.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the hydrotalcites (precursors) and the hydrotalcite-derived oxides (catalysts) were obtained using a Philips X’pert PW 3710 diffractometer (CuKα radiation, λ = 1.54184 Å). FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker IFS 48 spectrometer using the KBr pellet technique. Structural analysis was supported by chemical bulk analysis performed using an elemental analyser (Euro Vector EuroEA 3000), flame atomic absorption spectrometry (F-AAS, ContrAA 800 D, Jena Analytik), and ion chromatography (Shimadzu IC-CDD equipped with a Shim-pack IC-C4 cation column and conductivity detector) after dissolution of the catalysts in nitric acid.

Textural properties of the calcined materials were determined by low-temperature N2 adsorption using an ASAP 2010 (Micromeritics) sorptometer. Surface acid-base properties were assessed by temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) of NH3 and CO2. After outgassing in an N2 flow and cooling to ambient temperature, the flow of NH3 (1% NH3/He, 20 cm3/min) or CO2 (85 cm3/min) was applied. For CO2 adsorption, the samples were transferred into a desiccator and kept for 24 h in a pure CO2 atmosphere. Desorption was monitored using a VG SX-200 quadrupole mass spectrometer.

Catalytic activity in n-butane ODH was studied in a plug-flow microreactor loaded with 50 mg of catalyst. After outgassing in N₂ at 550 °C, the catalyst bed was fed with a reaction mixture (10% n-C4H10, 10% O2, 80% N₂, total flow = 100 cm3/min). Substrates and products were analyzed online using a Varian 3400 gas chromatograph equipped with TCD and FID detectors. Catalytic performance was expressed as conversion of substrate (X, %) and selectivity to products (S, %), as well as specific activity (SX) and specific yield of ODH products (SY) per catalyst surface area (mmol/h . m2).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Hydrotalcite-Like Materials

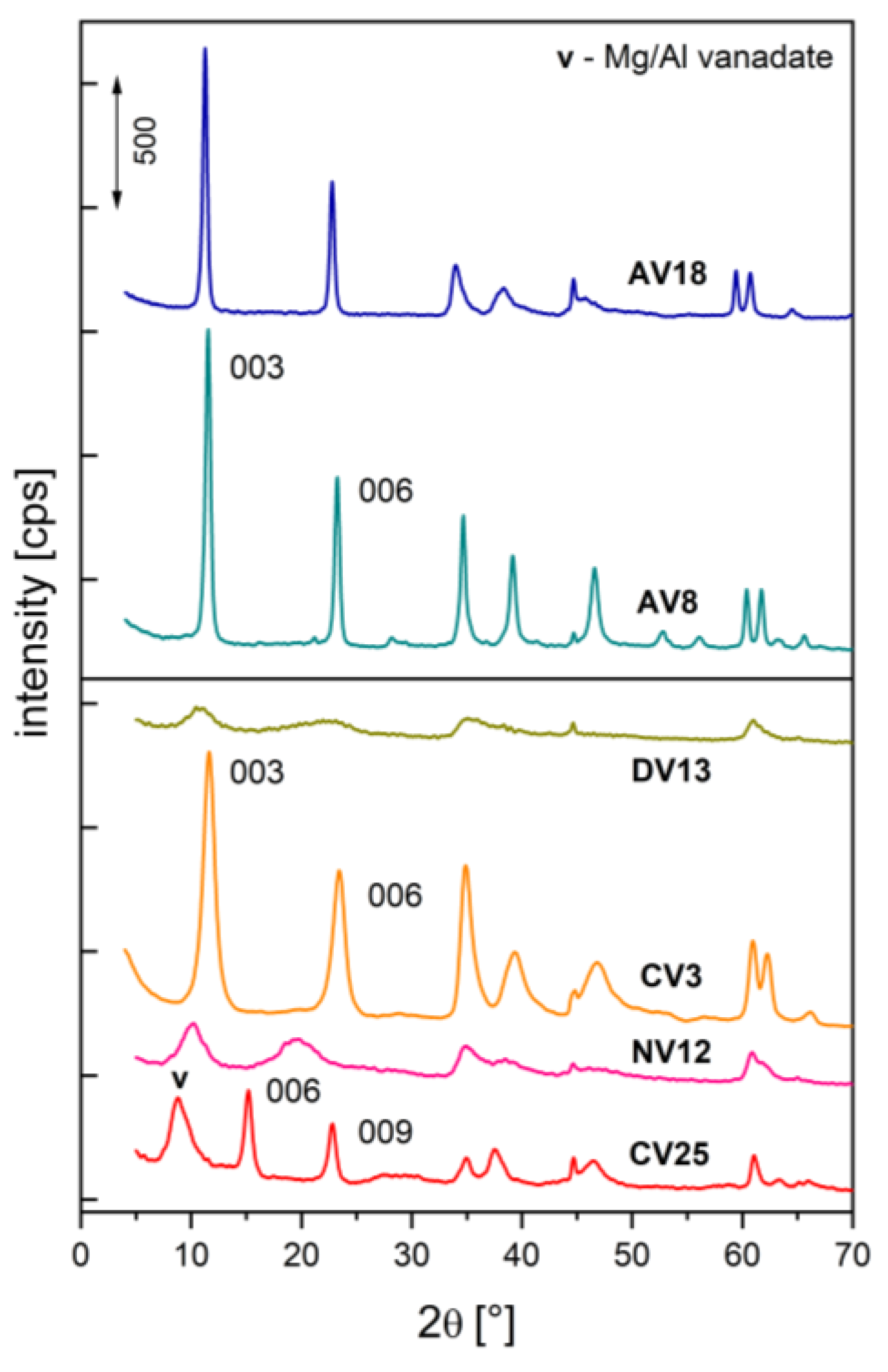

The X-ray powder diffraction patterns shown in

Figure 2 are characteristic of layered double hydroxides (LDHs) with rhombohedral symmetry 3R1 [

56]. However, due to different preparation procedures, discrepancies were observed in the crystallinity of the obtained samples, the positions of basal reflections (00l), and the occurrence of side phases.

Two samples with pyro-/metavanadates intercalated via ion exchange (NV12) or co-precipitation (DV13) exhibited diffuse, poorly developed structures. No shift of the basal reflections, indicative of anion exchange, was observed for the carbonate-containing hydrotalcite (CV3). In contrast, the decavanadate-pillared hydrotalcite (CV25) showed a significant shift of the basal reflection, along with the presence of a side phase, as a result of Mg

2+ leaching under the acidic conditions used for ion exchange. As shown previously [

57], in the case of some cations, such as V

3+, an additional procedure is necessary to obtain a well-developed structure. Hydrothermal treatment at elevated temperature and pressure resulted in well-resolved XRD patterns with sharp peaks for samples AV8 and AV18.

The cell parameters c and a were calculated according to the following equations:

The crystallite sizes k

a and k

c were estimated from line broadening using the Debye-Scherrer equation:

where

D is the crystalline size,

K is the Scherrer constant or the shape factor (here equal 0.89), and

β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peaks. The results are presented in

Table 1.

As mentioned above, the sample obtained under acidic conditions (CV25) was successfully intercalated with decavanadates. The c parameter value is only slightly lower than values reported for V

10O

286- with its C

2 axis oriented parallel to the brucite-like sheets [

30,

58,

59]. A decrease in the a parameter compared to the parent material (CV0) was also observed, confirming Mg

2+ extraction from the hydroxide layers. No such effect was observed for samples contacted with basic vanadate solutions (CV3, NV12). Based on the c parameter values, it can be concluded that carbonates can be exchanged by higher charge-density anions such as V

10O

286-, but not by pyro- or metavanadates. The small amount of vanadium in sample CV3 is most likely due to adsorption of vanadates on the external crystallite surfaces.

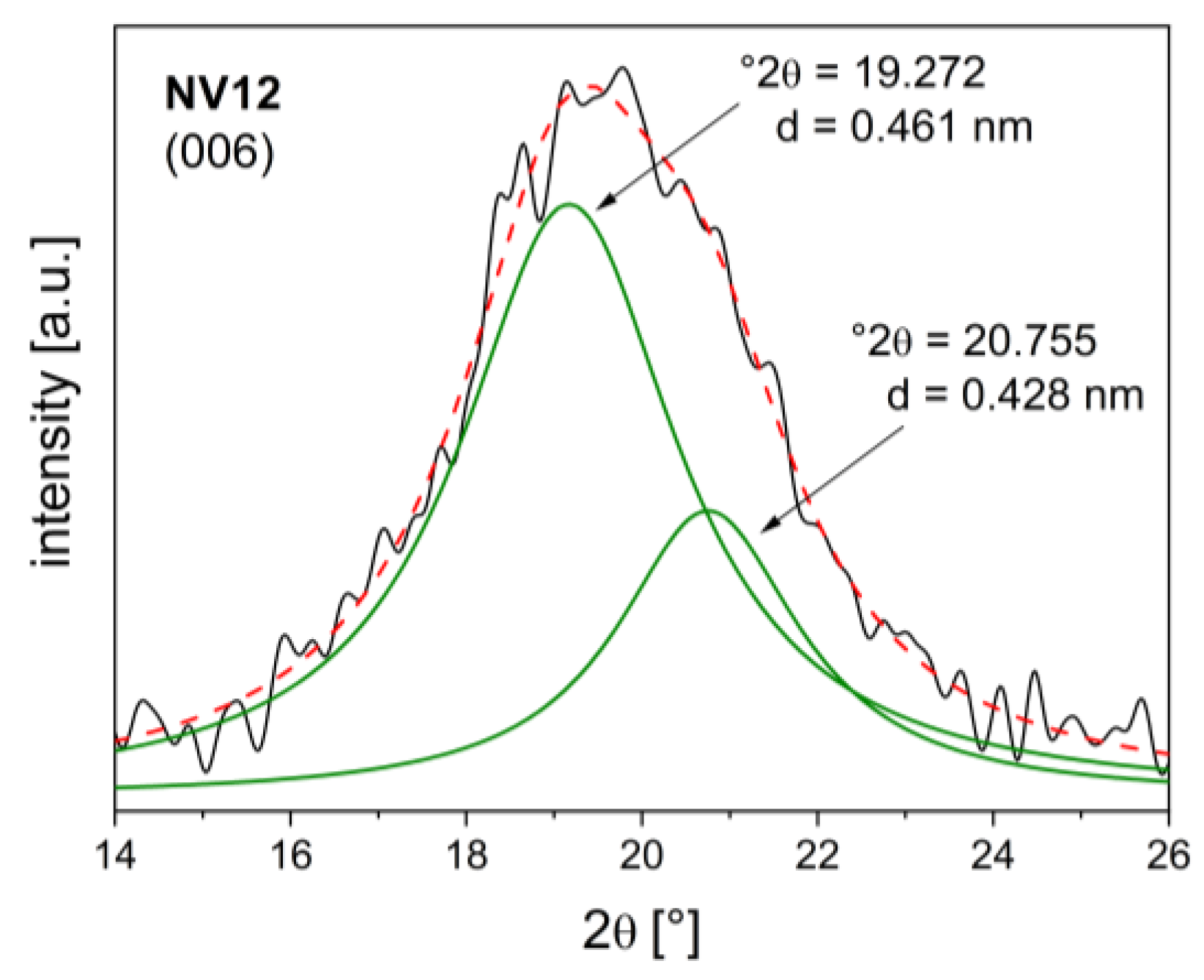

The diffuse patterns of NV12 and DV13 can be attributed to turbostratic disorder, undetectable impurities, or the presence of anion mixtures [

59,

60]. Deconvolution of the basal reflection (

Figure 3) gave c parameter values close to those for both pyrovanadate- and carbonate-intercalated hydrotalcites [

24,

61,

62]. Therefore, crystallite size could not be reliably determined from the broadening of the basal reflections. A similar phenomenon was reported for hydrotalcites intercalated with a CO

32-/NO

3- mixture [

63].

The results do not provide a clear answer as to which vanadate species was incorporated into the interlayers, as similar c values have been reported for both metavanadate- and pyrovanadate-intercalated hydrotalcites [

59,

60,

64]. For V

3+-doped hydrotalcites, the interlayer distances correspond to those of carbonate-intercalated hydrotalcites (AV8) or are slightly higher (AV18). The latter may be explained by the lower positive charge of the brucite-like layer in AV18 [

29]. Complete substitution of Al

3+ by V

3+ led to an increase in the a parameter. Hydrothermal treatment also increased crystallite size -

ka and

kc values for AVx samples were 3-4 times higher than those of the other materials.

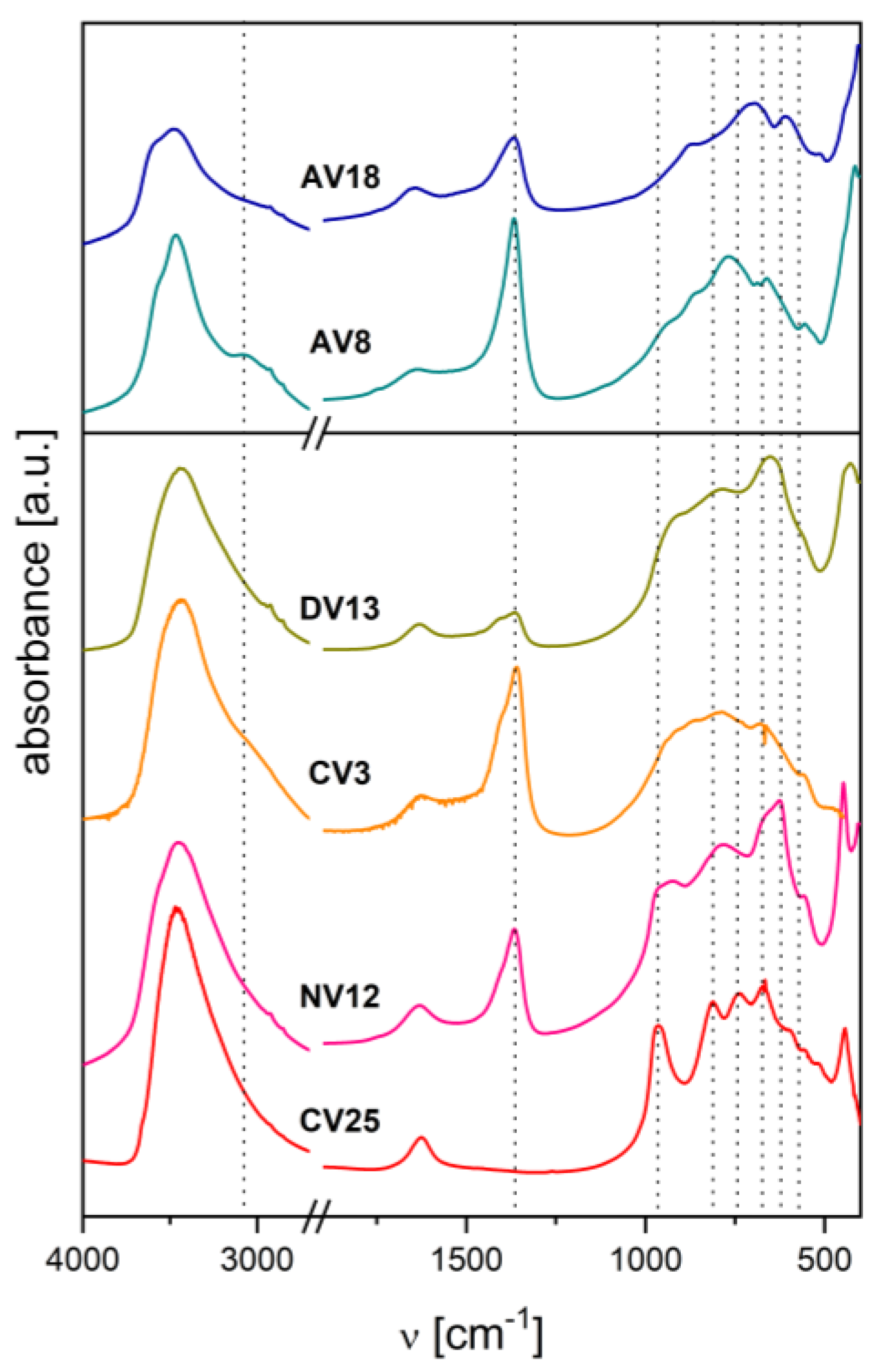

The FTIR spectra (

Figure 4) confirmed the presence of V

10O

286- in the interlayers of CV25. Several infrared bands characteristic of decavanadates were identified: 964 cm

-1 (symmetric stretching vibrations of VO

2 or terminal V=O), 813 and 517 cm

-1 (antisymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations in V-O-V chains), 739 cm

-1 (V-O stretching), and 673 cm

-1 (assigned to H

xV

10O

286-x, x = 1-3) [

65,

66,

67].

All spectra also showed bands associated with OH

- stretching vibrations (~3450 cm

-1) and bending modes of interlayer water molecules (1626-1650 cm

-1). Interlayer carbonates were present in all samples prepared under basic conditions, either co-precipitated with carbonates (AVx) or contaminated with CO

32- (CV3, NV12, DV13), as indicated by modes at 3060 cm

-1 (bridging CO

32-–H

2O), 1360/1405 cm

-1 (ν

3 stretching CO

32-), and 850 cm

-1 (ν

2 stretching CO

32-) [

29,

68]. One band not observed in other samples appeared in AV18 at 711 cm

-1, assigned to V-O vibrations in brucite-like layers [

69].

It was not possible to distinguish between pyro- and metavanadates in NV12 and DV13 by FTIR. According to various authors, bands around 961-940 cm

-1 may arise from vibrations in metavanadate chains or cyclic V

4O

124-, bands at 925-927 cm

-1 correspond to symmetric stretching modes (VO

2) in HV

2O₇³⁻ or (VO

3)

nn-, the 785 cm

-1 band is assigned to symmetric stretching modes (VO

2) in (VO

3)

nn-, and bands at 616-627 cm

-1 correspond to V-O-V stretching modes in (VO

3)

nn- [

70,

71,

72].

3.2. Characterization of the Catalysts

The diversity of the preparation procedures yielded a series of hydrotalcite-like materials that, upon heating, formed mixed metal oxides with different chemical compositions, oxidation states of the transition metal, and, consequently, distinct physicochemical properties. A summary of the bulk structural and chemical analyses is given in

Table 2.

The highest V loading (25 wt%) was obtained for the CV25c sample, whose LDH precursor was pillared with V

10O

286-. However, this value was lower than expected. This may be due to the high trivalent cation ratio and the large size of the decavanadate species, which caused strong anion-anion repulsion, resulting in less than the required amount of anions being introduced into the interlayers. A different explanation must be considered for the discrepancies V

3+ in V content observed in both V

3+-doped samples (AVxc): the susceptibility of V

3+ to oxidation and its large ionic radius hinder quantitative precipitation and incorporation into the brucite-like layer [

57,

69].

In the other samples, the expected and obtained V-loadings were similar, although it cannot be excluded that some vanadates used during synthesis were adsorbed on the surface (CV3c, NV12c) or formed amorphous side phases (NV12c, DV13c).

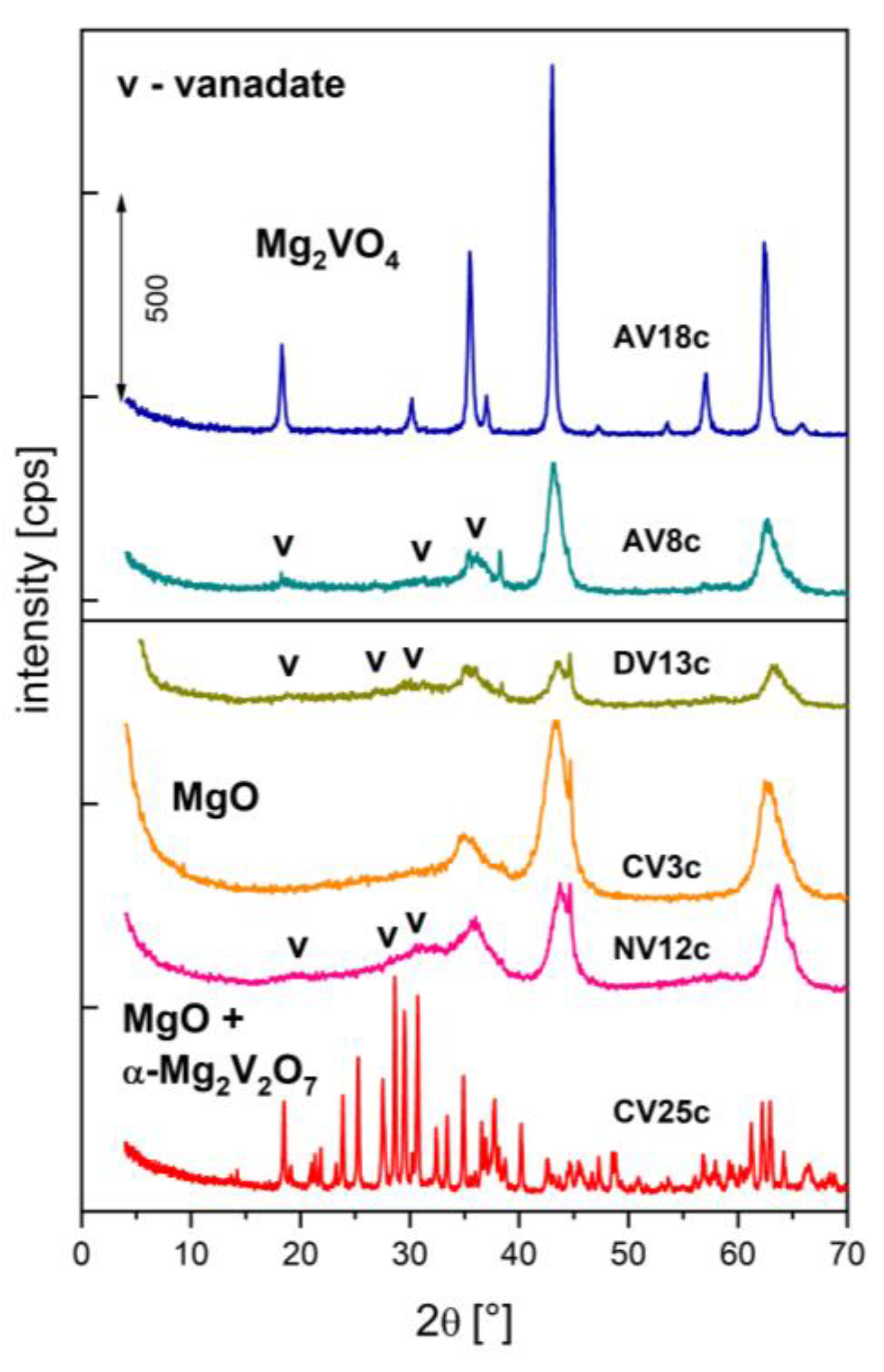

As shown in

Figure 5, the V loading determines the structure of the catalysts. In the CV25c sample, a mixture of highly crystalline α-Mg

2V

2O

7 and MgO was detected, consistent with previous results for similar hydrotalcite-derived catalysts [

22,

24,

25] and with phase diagrams of the MgO-V

2O

5 oxide system [

73,

74,

75]. Another V-rich catalyst, AV18c, was obtained from a V

3+-doped hydrotalcite calcined under inert atmosphere. In this case, a crystalline phase was also detected, but surprisingly, such a structure has not previously been reported from a hydrotalcite-like precursor. A few sharp peaks indicated the presence of spinel-like Mg

2VO

4 instead of orthovanadate Mg

3V

2O

8 [

23,

25,

26,

57,

69,

76,

77]. Weak reflections assigned to Mg

2VO

4 were also visible in the XRD pattern of another reduced-V sample, AV8c, although the main component was nearly amorphous MgO (periclase), with broad reflections at 2θ ≈ 36°, 43°, and 63°. Similar features were observed for other low-V catalysts (DV13c, NV12c), but in these cases, an additional vanadate phase and a disturbed pattern in the range 2θ ≈ 20°, 30°, 32° could be due to the presence of a dispersed orthovanadate phase. The CV3c sample consisted mostly of MgO. However, as it was shown recently, upon calcination gradual segregation of periclase in calcined Mg-containing hydrotalcites is expected [

78].

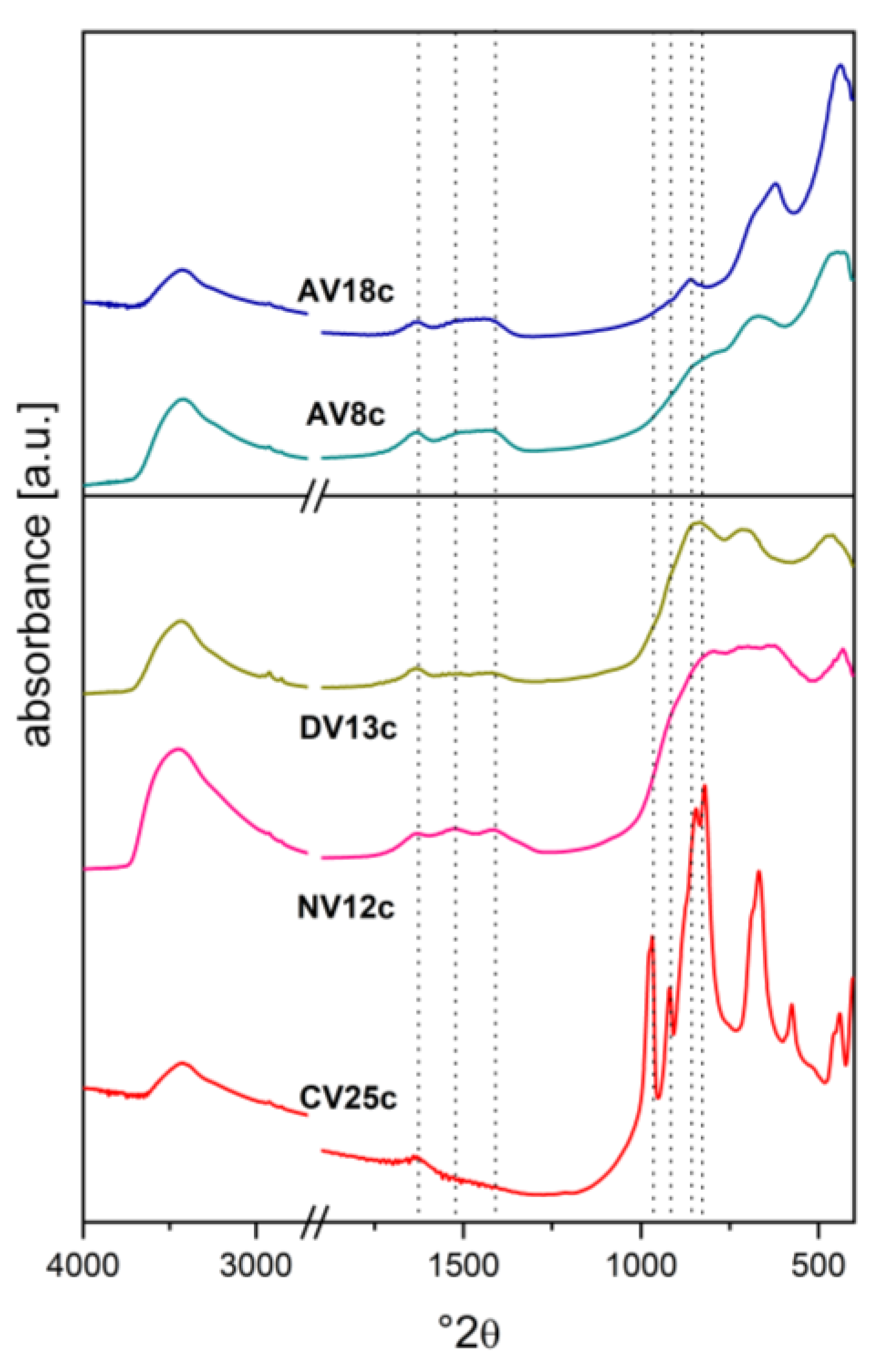

Additional insights into the catalyst structures were obtained from infrared spectra (

Figure 6). The most intense bands in CV25c were assigned to α-Mg

2V

2O

7 (970, 919, 848, 822 cm

-1), although some could also arise from Mg

3V

2O

8 vibrations (919, 822 cm

-1) [

22,

28,

57,

79]. Similarly, the IR spectra of DV13c and NV12c showed modes at 925/918 cm

-1 (ν

s VO

4), 835/823 cm

-1, and 469/492 cm

-1 (ν

s V-O-V) derived from Mg

3V

2O

8 vibrations, although magnesium pyrovanadate has characteristic modes in similar positions. Analysis of the 1400-1660 cm

-1 region provided information on CO

2 adsorption capacity. In addition to bands of re-adsorbed water, modes of bidentate CO

32- (1622-1630 cm

-1, ν

as) and unidentate CO

32- (1521-1523 cm

-1, ν

as, 1418-1428 cm

-1, ν

s) were observed, surprisingly even for low-surface-area AVxc samples [

80]. Only CV25c showed no visible CO

2 adsorption.

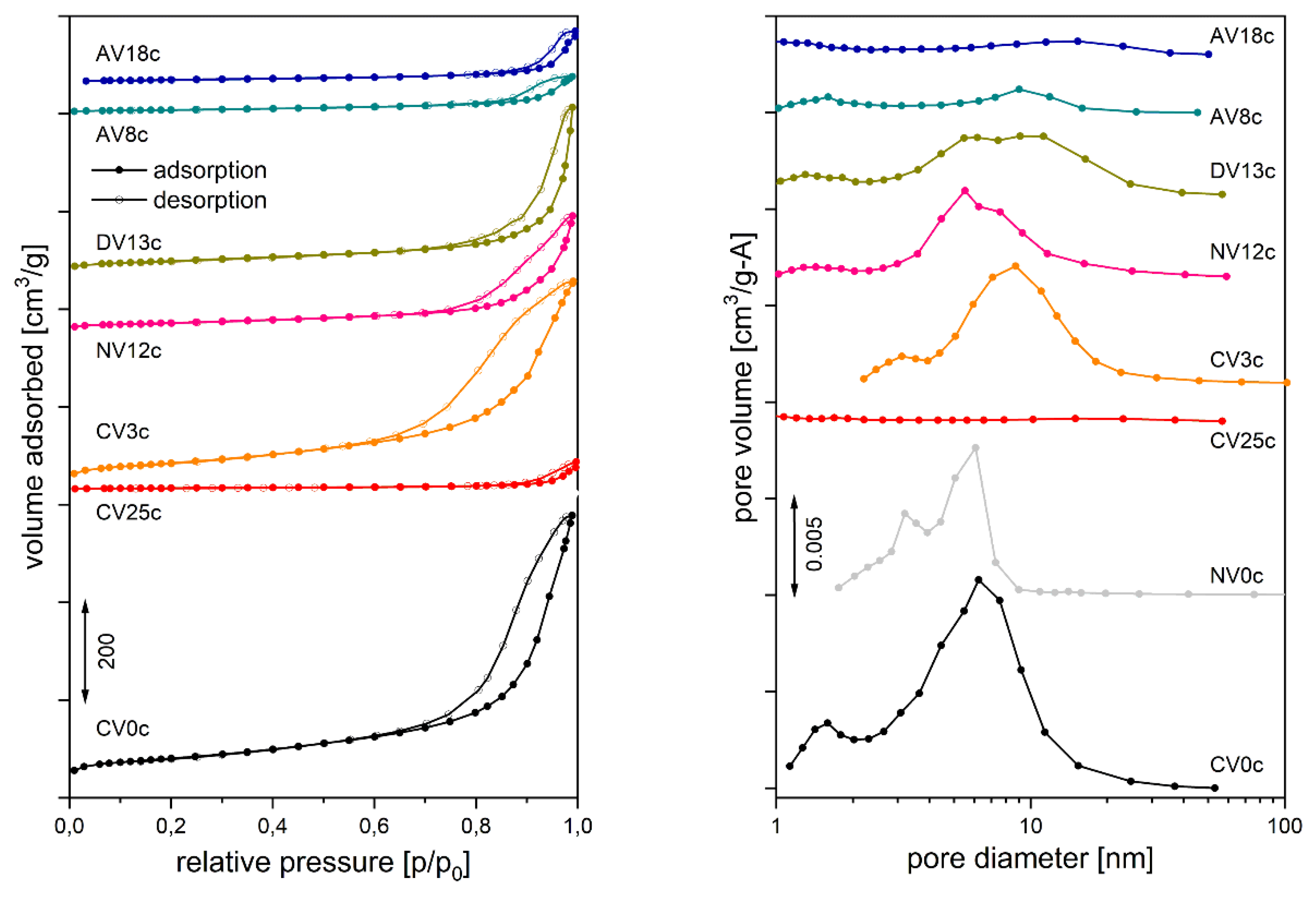

The catalysts also differed in textural parameters such as surface area, total pore volume, pore shape, and pore size distribution (

Table 3). The reduced-V samples (AVxc) and the highly loaded CV25c were nearly non-porous solids with surface areas of ~30 m

2/g and ~15 m

2/g, respectively. The quasi-amorphous structure of the other catalysts resulted in greater accessibility to gas molecules. Surface adsorption of vanadates followed by calcination of CV3 caused only a small decrease in surface area (from 216 to 196 m

2/g) and total pore volume (from 0.757 to 0.593 cm

3/g) compared to the undoped calcined parent material (CV0c). However, further increasing the V loading promoted sintering, reducing the surface area to 104 m

2/g (DV13c) and 79 m

2/g (NV12c). The hysteresis loop shapes (

Figure 7, right panel) were characteristic of mesoporous materials with bottle-shaped pores [

81,

82]. The pore size distribution was broad, with the most frequent values between 5 and 10 nm (

Figure 7, left panel). However, it would be worthwhile to consider depositing the precursor on a support with a high specific surface area, such as vermiculite [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89], which is resistant to high processing temperatures and has good adsorption capacity. This would improve the dispersion of the active phase and reduce the amount of metal required for the reaction.

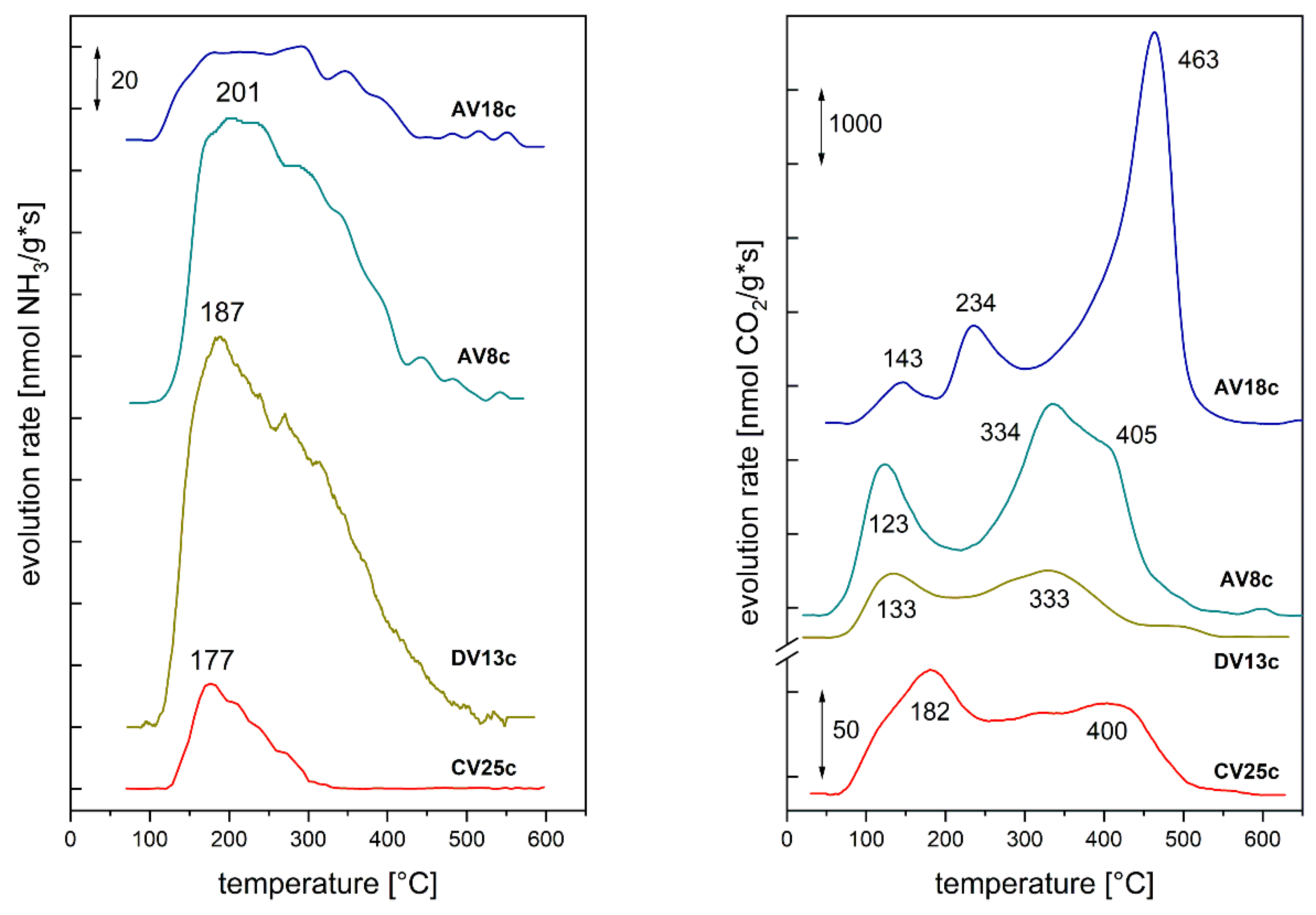

Temperature-programmed desorption of probe molecules was used to determine surface acid - base properties. The amount of NH

3 desorbed varied between 20 and 143 μmol/g, but the acid site density was similar for most samples (~1.4 μmol/m). Only AV8c, partially doped with reduced vanadium, showed a threefold higher acid site density. All catalysts exhibited a similar NH

3 desorption profile (

Figure 8, right panel): desorption began around 100-120 °C with a maximum rate below 200 °C. The broad, asymmetric peaks likely indicate uniformly distributed sites of similar strength, along with diffusion effects and molecule re-adsorption.

In contrast, CO

2 desorption profiles (

Figure 8, left panel) displayed several peaks, particularly well resolved for reduced-V samples (AVxc). The first desorption stage occurred at 120-145 °C, although for the pyrovanadate sample (CV25c) another maximum appeared at 180 °C, overlapping the first peak. For the spinel-like Mg

2VO

4 catalyst (AV18c), an additional step was observed at 235 °C. This suggests that complete substitution of Al by V and formation of a distinct structure rearranged the basic site strength distribution, favoring strong basic sites. The final significant CO

2 desorption occurred between 320 and 405 °C, with CO

2 remaining on Mg

2VO

4 surfaces up to 465 °C. However, prolonged CO

2 adsorption led to bulk carbonate formation and multilayer adsorption, meaning the results should be considered qualitative.

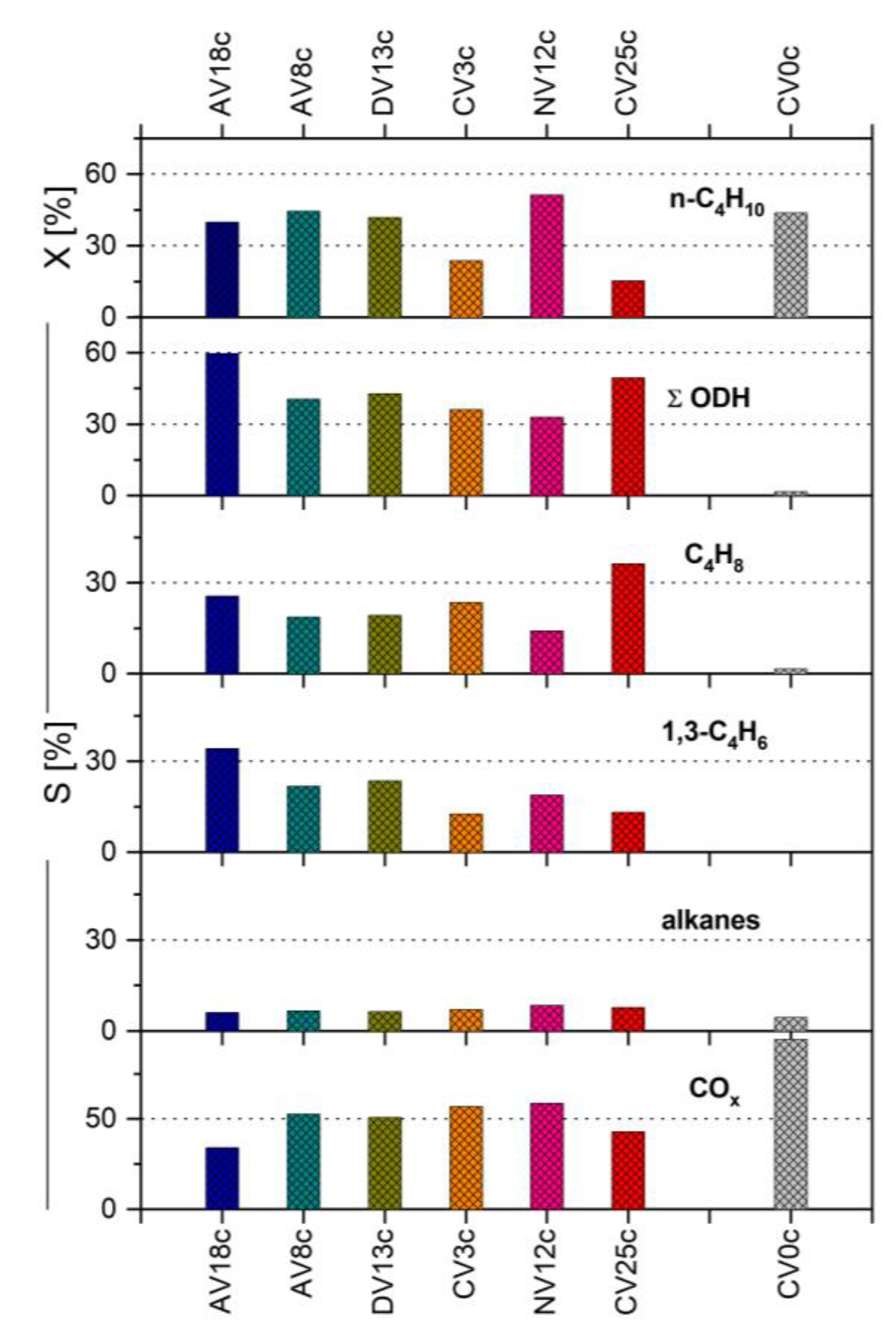

3.3. Catalytic Study

Hydrotalcite-derived vanadium-containing catalysts were studied in the oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) of n-butane using O

2 as an oxidant (

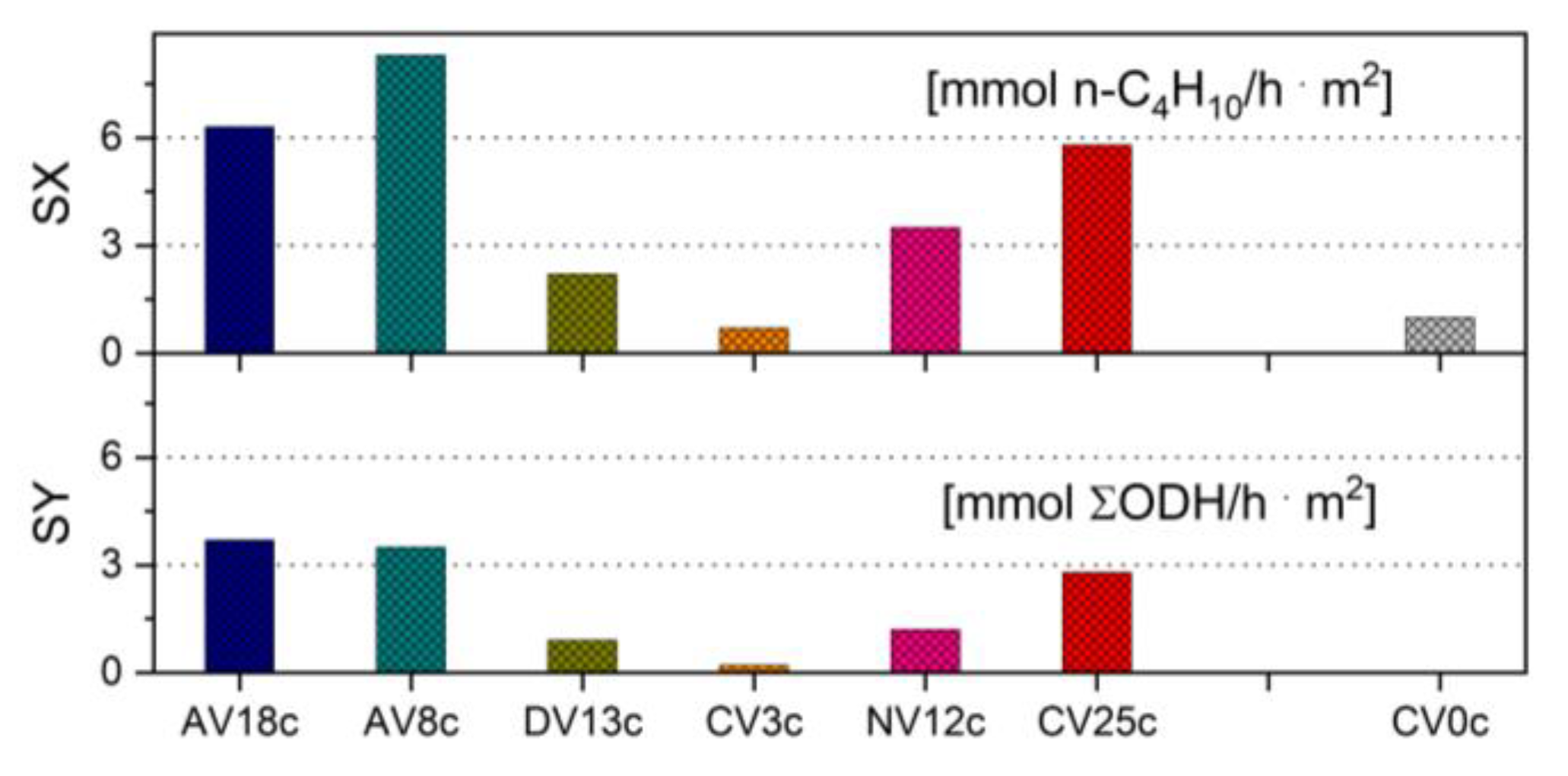

Figure 9). No straightforward correlation between chemical composition and physico-chemical properties could be established. The highest n-butane conversion (up to 51%) was obtained for samples derived from pyro-/metavanadate-pillared LDH precursors (NV12c, DV13c) as well as catalysts containing reduced vanadium (AVxc), for which the conversion reached 40-44%. Furthermore, these two latter samples exhibited the highest specific activity per surface area (SX), in the range of 6.3-8.3 mmol n-C

4H

10/h

. m

2 (

Figure 10).

Interestingly, another highly loaded sample, CV25c, also showed high specific activity (5.3 mmol n-C

4H

10/h

. m

2) but only low conversion (15%). Surprisingly, the undoped Mg/Al catalysts (CV0c, NV0c) were also very active (conversion of n-C

4H

10 around 44%), although their main products were CO

x. This is probably due to the fact that on high-surface-area catalysts such as NV12c or CV0c, total oxidation to carbon oxides occurs via acidic centers associated with dispersed Al

3+ cations [

28].

Moreover, the presence of specific structures such as α-Mg

2V

2O

7 (CV25c) or dispersed, easily reducible isolated VO

4 tetrahedra, suggested to be present on the surface of amorphous catalysts like DV13c, NV12c, or even CV3c, may enhance activity towards CO

x formation [

90,

91]. Nevertheless, high total selectivity to dehydrogenated species was recorded for these samples: 50%, 43%, 33%, and 36%, respectively.

Another possible explanation for high selectivity in n-butane ODH is the presence of magnesium in V-O-Mg units, which increases the basicity of the mixed oxides compared to V-O-V units. Additionally, the presence of reduced V cations in the structure, or their in situ reduction by alkanes, can further enhance basicity, leading to faster desorption of butenes [

18,

19,

77,

91,

92,

93].

Due to the synergistic effect between specific structure, basic properties, and high transition metal loading, the highest specific yields (SY) of alkenes per surface area, 2.8, 3.5, and 3.7 mmol/h . m2, were achieved for catalysts CV25c, AV8c, and AV18c, respectively. Formation of butene isomers was favored on CV25c (36%), whereas 1,3-butadiene formation reached 22% and 34% for AV8c and AV18c, respectively. The latter also showed limited selectivity to COx (34%).

Selection of a suitable V-containing LDH precursor and careful control of the preparation procedure can be highly beneficial for catalytic activity in n-butane ODH and for selectivity towards desired products. Within the studied group, the best catalytic results were obtained when V

3+-doped hydrotalcites were calcined in an inert atmosphere. However, special care must be taken during the catalytic reaction to avoid excessive oxidation and subsequent deactivation of the catalysts [

77]. On the other hand, optimum conditions must also be identified to prevent coke formation.

4. Conclusions

Hydrotalcites doped with vanadium via four different procedures exhibited a variety of XRD patterns within the range typical for these materials.

Samples obtained by pyrovanadate exchange displayed low-crystalline, diffuse structures pillared with vanadates, with basal reflections shifted to lower 2θ angles (NV12) or without significant changes (CV3) when nitrate- or carbonate-containing parent materials were used, respectively. The sample precipitated directly in the presence of a vanadate solution (DV13) also showed a diffuse structure, and the position of its basal reflections indicated the presence of pyro-/metavanadates in the interlayer space. In all of the above samples, carbonate contamination was detected.

In the sample pillared with decavanadates (CV25), the hydrotalcite structure was identified along with an additional Mg/Al vanadate phase, formed as a result of acidic leaching during the ion-exchange process. Samples doped with V3+ (AVx) showed a well-defined hydrotalcite structure pillared with carbonates. High crystallinity in these materials was attributed to the hydrothermal treatment applied during synthesis.

The vanadium content and/or oxidation state strongly influenced the phase composition of catalysts obtained by calcination of the corresponding hydrotalcites. All samples with low V content (up to 13 wt% in the mixed oxide - CV3c, NV12c, DV13c, AV8c), regardless of vanadium oxidation state, contained a periclase (MgO) phase and traces of vanadates, likely Mg3V2O8 or Mg2VO4 for samples doped with oxidized or reduced vanadium, respectively. The decavanadate-pillared hydrotalcite transformed into a mixture of MgO and α-Mg2V2O7 (CV25c), whereas the V3+-doped sample, after calcination in an inert atmosphere, formed a spinel-like phase, Mg2VO4.

Textural properties, such as surface area and total pore volume, were determined by both V loading and the initial vanadium oxidation state. Hydrotalcites containing reduced V cations (AVxc) and the highly V5+-loaded sample (CV25c) were nearly non-porous, with surface areas of ~30 and ~15 m²/g, respectively. Other catalysts (CV3c, NV12c, DV13c) exhibited higher surface areas (196, 79, and 104 m²/g, respectively) and bottle-shaped mesopores in the 2 nm and 6-10 nm ranges.

Basicity measurements for selected samples indicated significantly higher basicity than acidity. However, quantitative CO2 adsorption analysis for the high-surface-area DV13c sample and the reduced V-doped samples (AVxc) was affected by bulk carbonate formation and multilayer CO₂ adsorption.

In the catalytic study, the highest n-butane conversion, up to 51%, was recorded for catalysts containing reduced vanadium cations (AVxc) and for amorphous, medium-V-loaded, high-surface-area samples (DV13c, NV12c). The highest specific activity per surface area was observed for AVxc (6.3-8.6 mmol n-C4H10/h . m2) and CV25c (5.8 mmol n-C4H10/h . m2). These same samples also showed the highest specific yield of dehydrogenated products per surface area, reaching up to 3.7 mmol/h . m2.

Formation of butene isomers (up to 36%) was favored on highly basic, reduced-vanadium-doped catalysts (AVxc) and the highly V5+-loaded catalyst (CV25c), whereas the highest selectivity to 1,3-butadiene (S = 34%) was observed mainly for the AVxc group. Overall, the most effective catalysts in the ODH of n-butane, combining high activity with low total oxidation, were the highly basic catalysts containing reduced vanadium.

To fully utilize the potential of the designed vanadium catalysts, it is necessary to consider depositing the precursor on a support with a high specific surface area. High dispersion of the active phase will contribute to better utilization of the active sites and reduce metal loading. Furthermore, modifiers that further stabilize the active phase should be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W., methodology, A.W., validation, A.W. and P.M., investigation, A.W., A.K., P.M., data curation, A.W., P.M., writing—original draft preparation, A.W., A.K., writing—review and editing, A.W., W.M., visualization, A.W., A.K., supervision, A.W., funding acquisition, A.W., P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

The study was partially carried out using research infrastructure funded by the European Union in the framework of the Smart Growth Operational Programme, Measure 4.2, Grant Number POIR.04.02.00-00-D001/20, “ATOMIN 2.0 - Center for materials research on ATOMic scale for the INnovative economy.”

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. Lee, S.-H. Joo, D. J. Shin, and S. M. Shin, “Recovery of vanadium and cesium from spent sulfuric acid catalysts by a hydrometallurgical process,” Green Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 790–799, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. F. K. Mangini, R. B. G. Valt, M. J. J. de S. Ponte, and H. de A. Ponte, “Vanadium removal from spent catalyst used in the manufacture of sulfuric acid by electrical potential application,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 246, p. 116854, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Freire et al., “Supported Vanadium Catalysts: Heterogeneous Molecular Complexes, Electrocatalysis and Biomass Transformation,” in Vanadium Catalysis, The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020, pp. 241–284. [CrossRef]

- C. Domingues, M. J. N. Correia, R. Carvalho, C. Henriques, J. Bordado, and A. P. S. Dias, “Vanadium phosphate catalysts for biodiesel production from acid industrial by-products,” J Biotechnol, vol. 164, no. 3, pp. 433–440, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Chu, J. Luo, S. Paul, Y. Liu, A. Khodakov, and E. Bordes, “Synthesis and performance of vanadium-based catalysts for the selective oxidation of light alkanes,” Catal Today, vol. 298, pp. 145–157, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tian, X. Liu, W. Ma, S. Cheng, and L. Zhang, “Boosting activity of γ-alumina-supported vanadium catalyst for isobutane non-oxidative dehydrogenation via pure V3+,” J Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 652, pp. 508–517, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Marx, H.-J. Wölk, G. Mestl, and T. Turek, “Reaction scheme of o-xylene oxidation on vanadia catalyst,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 398, no. 1–2, pp. 37–43, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Rezaei, A. Najafi Chermahini, and H. A. Dabbagh, “Green and selective oxidation of cyclohexane over vanadium pyrophosphate supported on mesoporous KIT-6,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 314, pp. 515–525, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Ye et al., “Recent trends in vanadium-based SCR catalysts for NOx reduction in industrial applications: stationary sources,” Nano Converg, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 51, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, X. Li, P. Chen, and B. Zhu, “Research Status and Prospect on Vanadium-Based Catalysts for NH3-SCR Denitration,” Materials, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 1632, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kamika and M. N. B. Momba, “Effect of vanadium toxicity at its different oxidation states on selected bacterial and protozoan isolates in wastewater systems,” Environ Technol, vol. 35, no. 16, pp. 2075–2085, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “40 CFR Part 1065 Subpart L - Vanadium Sublimation In SCR Catalysts,” https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/part-1065/subject-group-ECFR402811cb661d755.

- P. Moreau et al., “Investigation of vanadium sublimation from SCR catalysts,” in SAE Technical Paper, Sep. 2015, p. 2503. [CrossRef]

- S. Hu et al., “Metals emitted from heavy-duty diesel vehicles equipped with advanced PM and NOX emission controls,” Atmos Environ, vol. 43, no. 18, pp. 2950–2959, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Chapman, “Behavior of titania-supported vanadia and tungsta SCR catalysts at high temperatures in reactant streams: Tungsten and vanadium oxide and hydroxide vapor pressure reduction by surficial stabilization,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 392, no. 1–2, pp. 143–150, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Z. G. Liu, N. A. Ottinger, and C. M. Cremeens, “Vanadium and tungsten release from V-based selective catalytic reduction diesel aftertreatment,” Atmos Environ, vol. 104, pp. 154–161, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Rostom and H. de Lasa, “Propane Oxidative Dehydrogenation on Vanadium-Based Catalysts under Oxygen-Free Atmospheres,” Catalysts, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 418, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Madeira and M. F. Portela, “Catalytic oxidative dehydrogenation of n -butane,” Catalysis Reviews, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 247–286, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. Chaar, “Selective oxidative dehydrogenation of butane over V$z.sbnd;Mg$z.sbnd;O catalysts,” J Catal, vol. 105, no. 2, pp. 483–498, Jun. 1987. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Kung and M. C. Kung, “Oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes over vanadium-magnesium-oxides,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 157, no. 1–2, pp. 105–116, Sep. 1997. [CrossRef]

- T. Blasco, J. M. L. Nieto, A. Dejoz, and M. I. Vazquez, “Influence of the Acid-Base Character of Supported Vanadium Catalysts on Their Catalytic Properties for the Oxidative Dehydrogenation of n-Butane,” J Catal, vol. 157, no. 2, pp. 271–282, Dec. 1995. [CrossRef]

- D. Siew Hew Sam, V. Soenen, and J. C. Volta, “Oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over VMgO catalysts,” J Catal, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 417–435, Jun. 1990. [CrossRef]

- G. Carja, R. Nakamura, T. Aida, and H. Niiyama, “Mg–V–Al mixed oxides with mesoporous properties using layered double hydroxides as precursors: catalytic behavior for the process of ethylbenzene dehydrogenation to styrene under a carbon dioxide flow,” J Catal, vol. 218, no. 1, pp. 104–110, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. Bahranowski, “Oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over calcined vanadate-exchanged Mg,Al-layered double hydroxides,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 185, no. 1, pp. 65–73, Sep. 1999. [CrossRef]

- R. Dula et al., “Layered double hydroxide-derived vanadium catalysts for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 230, no. 1–2, pp. 281–291, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Holgado, F. M. Labajos, M. J. S. Montero, and V. Rives, “Thermal decomposition of Mg/V hydrotalcites and catalytic performance of the products in oxidative dehydrogenation reactions,” Mater Res Bull, vol. 38, no. 14, pp. 1879–1891, Nov. 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. M. López Nieto, P. Concepción, A. Dejoz, H. Knözinger, F. Melo, and M. I. Vázquez, “Selective Oxidation of n-Butane and Butenes over Vanadium-Containing Catalysts,” J Catal, vol. 189, no. 1, pp. 147–157, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. Lopeznieto, A. Dejoz, and M. Vazquez, “Preparation, characterization and catalytic properties of vanadium oxides supported on calcined Mg/Al-hydrotalcite,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 132, no. 1, pp. 41–59, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- F. Cavani, F. Trifirò, and A. Vaccari, “Hydrotalcite-type anionic clays: Preparation, properties and applications.,” Catal Today, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 173–301, Dec. 1991. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Drezdzon, “Synthesis of isopolymetalate-pillared hydrotalcite via organic-anion-pillared precursors,” Inorg Chem, vol. 27, no. 25, pp. 4628–4632, Dec. 1988. [CrossRef]

- E. Gardner and T. J. Pinnavaia, “On the nature of selective olefin oxidation catalysts derived from molybdate- and tungstate-intercalated layered double hydroxides,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 167, no. 1, pp. 65–74, Feb. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang and D. O’Hare, “Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanosheets,” Chem Rev, vol. 112, no. 7, pp. 4124–4155, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, D. Wang, Q. Yang, Y. Peng, and J. Li, “Multi-pollutant control (MPC) of NO and chlorobenzene from industrial furnaces using a vanadia-based SCR catalyst,” Appl Catal B, vol. 285, p. 119835, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, Z. Liu, D. Wang, Y. Peng, and J. Li, “The effect of additives and intermediates on vanadia-based catalyst for multi-pollutant control,” Catal Sci Technol, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 323–326, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, X. Zhang, F. Yang, Y. Ai, Y. Chen, and D. Pan, “Strategy and Technical Progress of Recycling of Spent Vanadium–Titanium-Based Selective Catalytic Reduction Catalysts,” ACS Omega, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 6036–6058, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Ferella, “A review on management and recycling of spent selective catalytic reduction catalysts,” J Clean Prod, vol. 246, p. 118990, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Amato, N. M. Ippolito, M. D’Arcangelo, A. Becci, V. Innocenzi, and F. Ferella, “Vanadium, molybdenum and nickel: A sustainability analysis of the extraction from ores versus recovery from spent catalysts,” J Clean Prod, vol. 515, p. 145817, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, J. Q. Zhong, Z. Z. Wang, and C. H. Zhou, “Catalytic Glycerol Conversion over Bifunctional Montmorillonite-Supported Mo−V Oxide Catalysts: Insights into the Dehydration-Hydrogen Transfer Reaction Pathway Toward Allyl Alcohol,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 1994–2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, M. A. Jabed, D. M. Price, D. Kilin, and S. Kim, “Toward rational design of supported vanadia catalysts of lignin conversion to phenol,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 446, p. 136965, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Hou and W. Xie, “Exploring hierarchical porous γ-Al2O3 modified with MoV metal oxides used as a high-efficiency solid catalyst for sustainable biodiesel production from low-cost acidic oils,” Renew Energy, vol. 250, p. 123303, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gucbilmez, T. Dogu, and S. Balci, “Ethylene and Acetaldehyde Production by Selective Oxidation of Ethanol Using Mesoporous V−MCM-41 Catalysts,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 3496–3502, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Antonio, “Circular Economy Principles in Renewable Fuels,” in Hydrogen and Low-Carbon Fuels in Circular Bio-economy, 2025, pp. 27–49. [CrossRef]

- N. Tsolakis, W. Bam, J. S. Srai, and M. Kumar, “Renewable chemical feedstock supply network design: The case of terpenes,” J Clean Prod, vol. 222, pp. 802–822, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumagai, K. Fujiwara, T. Nishiyama, Y. Saito, and T. Yoshioka, “Chemical Feedstock Recovery Through Plastic Pyrolysis: Challenges and Perspectives Toward a Circular Economy,” ChemSusChem, vol. 18, no. 16, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Palkovits and I. Delidovich, “Efficient utilization of renewable feedstocks: the role of catalysis and process design,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 376, no. 2110, p. 20170064, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ewing, N. Nouse, M. van Lint, J. van Haveren, J. Hugenholtz, and D. S. van Es, “Fermentation for the production of biobased chemicals in a circular economy: a perspective for the period 2022–2050,” Green Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 17, pp. 6373–6405, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T.-L. Chen, H. Kim, S.-Y. Pan, P.-C. Tseng, Y.-P. Lin, and P.-C. Chiang, “Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 716, p. 136998, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Guarieiro et al., “Reaching Circular Economy through Circular Chemistry: The Basis for Sustainable Development,” J Braz Chem Soc, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Linder, “Ripe for disruption: reimagining the role of green chemistry in a circular economy,” Green Chem Lett Rev, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 428–435, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Amer, H. Toogood, and N. S. Scrutton, “Engineering nature for gaseous hydrocarbon production,” Microb Cell Fact, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 209, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Amer et al., “Renewable and tuneable bio-LPG blends derived from amino acids,” Biotechnol Biofuels, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 125, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Johnson, “Process Technologies and Projects for BioLPG,” Energies (Basel), vol. 12, no. 2, p. 250, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang and K. Zhu, “Microbial production of alka(e)ne biofuels,” Curr Opin Biotechnol, vol. 50, pp. 11–18, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Systems engineering of Escherichia coli for n-butane production,” Metab Eng, vol. 74, pp. 98–107, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Jiang et al., “Efficient Preparation of Bio-based n -Butane Directly from Levulinic Acid over Pt/C,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 59, no. 13, pp. 5736–5744, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Newman, W. Jones, P. O’Connor, and D. N. Stamires, “Synthesis of the 3R2 polytype of a hydrotalcite-like mineral,” J Mater Chem, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 153–155, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Labajos, V. Rives, P. Malet, M. A. Centeno, and M. A. Ulibarri, “Synthesis and Characterization of Hydrotalcite-like Compounds Containing V 3+ in the Layers and of Their Calcination Products,” Inorg Chem, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1154–1160, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Taehyun. Kwon, G. A. Tsigdinos, and T. J. Pinnavaia, “Pillaring of layered double hydroxides (LDH’s) by polyoxometalate anions,” J Am Chem Soc, vol. 110, no. 11, pp. 3653–3654, May 1988. [CrossRef]

- V. Rives and M. Angeles Ulibarri, “Layered double hydroxides (LDH) intercalated with metal coordination compounds and oxometalates,” Coord Chem Rev, vol. 181, no. 1, pp. 61–120, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- K. Han, “Intercalation process of metavanadate chains into a nickel–cobalt layered double hydroxide,” Solid State Ion, vol. 98, no. 1–2, pp. 85–92, Jun. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D. B. Hall, and T. J. Barnes, “Novel oligovanadate-pillared hydrotalcites,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 10, no. 1–2, pp. 57–67, Aug. 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. Twu and P. K. Dutta, “Structure and reactivity of oxovanadate anions in layered lithium aluminate materials,” J Phys Chem, vol. 93, no. 23, pp. 7863–7868, Nov. 1989. [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn, A. Rafalska-Łasocha, D. Majda, R. Dziembaj, and H. Papp, “The influence of mixed anionic composition of Mg–Al hydrotalcites on the thermal decomposition mechanism based on in situ study,” J Therm Anal Calorim, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 443–457, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- K. Han, “A new metavanadate inserted layered double hydroxide prepared by ‘chimie douce,’” Solid State Ion, vol. 84, no. 3–4, pp. 227–238, Apr. 1996. [CrossRef]

- F. Kooli, V. Rives, and M. A. Ulibarri, “Preparation and Study of Decavanadate-Pillared Hydrotalcite-like Anionic Clays Containing Transition Metal Cations in the Layers. 1. Samples Containing Nickel-Aluminum Prepared by Anionic Exchange and Reconstruction,” Inorg Chem, vol. 34, no. 21, pp. 5114–5121, Oct. 1995. [CrossRef]

- E. Lopez Salinas and Y. Ono, “Thermal Transformation of a Layered Double Hydroxide Pillared with Decavanadate Isopolyanions,” Bull Chem Soc Jpn, vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 2465–2470, Sep. 1992. [CrossRef]

- M.-A. Ulibarri, F. M. Labajos, V. Rives, R. Trujillano, W. Kagunya, and W. Jones, “Comparative Study of the Synthesis and Properties of Vanadate-Exchanged Layered Double Hydroxides,” Inorg Chem, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 2592–2599, Jun. 1994. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kloprogge and R. L. Frost, “Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Local Structure of Mg-, Ni-, and Co-Hydrotalcites,” J Solid State Chem, vol. 146, no. 2, pp. 506–515, Sep. 1999. [CrossRef]

- F. Kooli, I. Crespo, C. Barriga, M. A. Ulibarri, and V. Rives, “Precursor dependence of the nature and structure of non-stoichiometric magnesium aluminium vanadates,” J Mater Chem, vol. 6, no. 7, p. 1199, 1996. [CrossRef]

- W. P. Griffith, “Vibrational spectra of metaphosphates, meta-arsenates, and metavanadates,” Journal of the Chemical Society A: Inorganic, Physical, Theoretical, p. 905, 1967. [CrossRef]

- W. P. Griffith and T. D. Wickins, “Raman studies on species in aqueous solutions. Part I. The vanadates,” Journal of the Chemical Society A: Inorganic, Physical, Theoretical, p. 1087, 1966. [CrossRef]

- S. Onodera and Y. Ikegami, “Infrared and Raman spectra of ammonium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium metavanadates,” Inorg Chem, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 615–618, Mar. 1980. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Clark and R. Morley, “A study of the MgOV2O5 system,” J Solid State Chem, vol. 16, no. 3–4, pp. 429–435, Jan. 1976. [CrossRef]

- M. Del Arco, M. J. Holgado, C. Martín, and V. Rives, “New route for the synthesis of V2O5-MgO oxidative dehydrogenation catalysts,” J Mater Sci Lett, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 616–619, May 1987. [CrossRef]

- S. Köbel, D. Schneider, C. Chr. Schüler, and L. J. Gauckler, “Sintering of vanadium-doped magnesium oxide,” J Eur Ceram Soc, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 2267–2274, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Labajos, M. J. Sánchez-Montero, M. J. Holgado, and V. Rives, “Thermal evolution of V(III)-containing layered double hydroxides,” Thermochim Acta, vol. 370, no. 1–2, pp. 99–104, Apr. 2001. [CrossRef]

- W. S. Chang, Y. Z. Chen, and B. L. Yang, “Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene over VIV and VV magnesium vanadates,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 221–243, Apr. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn et al., “Towards Sorption Degradation Mechanism: Transformation of Hydrotalcite to Periclase and Spinel upon Calcination — Experimental Studies and DFT Modelling,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 377, p. 133963, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao, P. Ruiz, Q. Xin, X. Guo, and B. Delmon, “Preparation and characterization of three pure magnesium vanadate phases as catalysts for selective oxidation of propane to propene,” Catal Letters, vol. 23, no. 3–4, pp. 321–337, 1994. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Di Cosimo, V. K. Dı́ez, M. Xu, E. Iglesia, and C. R. Apesteguı́a, “Structure and Surface and Catalytic Properties of Mg-Al Basic Oxides,” J Catal, vol. 178, no. 2, pp. 499–510, Sep. 1998. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaneko, “Determination of pore size and pore size distribution,” J Memb Sci, vol. 96, no. 1–2, pp. 59–89, Nov. 1994. [CrossRef]

- G. Leofanti, M. Padovan, G. Tozzola, and B. Venturelli, “Surface area and pore texture of catalysts,” Catal Today, vol. 41, no. 1–3, pp. 207–219, May 1998. [CrossRef]

- W. Stawiński, A. Węgrzyn, T. Dańko, O. Freitas, S. Figueiredo, and L. Chmielarz, “Acid-base treated vermiculite as high performance adsorbent: Insights into the mechanism of cationic dyes adsorption, regeneration, recyclability and stability studies,” Chemosphere, vol. 173, pp. 107–115, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Stawiński, A. Węgrzyn, O. Freitas, L. Chmielarz, and S. Figueiredo, “Dual-function hydrotalcite-derived adsorbents with sulfur storage properties: Dyes and hydrotalcite fate in adsorption-regeneration cycles,” Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, vol. 250, pp. 72–87, Sep. [CrossRef]

- W. Stawiński, A. Węgrzyn, O. Freitas, L. Chmielarz, G. Mordarski, and S. Figueiredo, “Simultaneous removal of dyes and metal cations using an acid, acid-base and base modified vermiculite as a sustainable and recyclable adsorbent,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 576, pp. 398–408, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn et al., “Study of adsorptive materials obtained by wet fine milling and acid activation of vermiculite,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 155, pp. 37–49, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Silva et al., “Application of vermiculite-derived sustainable adsorbents for removal of venlafaxine,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 25, no. 17, pp. 17066–17076, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Stawiński, A. Węgrzyn, G. Mordarski, M. Skiba, O. Freitas, and S. Figueiredo, “Sustainable adsorbents formed from by-product of acid activation of vermiculite and leached-vermiculite-LDH hybrids for removal of industrial dyes and metal cations,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 161, pp. 6–14, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn et al., “Vermiculite as a potential functional additive for water treatment bioreactors inhibiting toxic action of heavy metal cations upsetting the microbial balance,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 433, p. 128812, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. S. Owen, M. C. Kung, and H. H. Kung, “The effect of oxide structure and cation reduction potential of vanadates on the selective oxidative dehydrogenation of butane and propane,” Catal Letters, vol. 12, no. 1–3, pp. 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Patel, “Oxidative dehydrogenation of butane over orthovanadates,” J Catal, vol. 125, no. 1, pp. 132–142, Sep. 1990. [CrossRef]

- S. Albonetti, F. Cavani, and F. Trifirò, “Key Aspects of Catalyst Design for the Selective Oxidation of Paraffins,” Catalysis Reviews, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 413–438, Nov. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Grzybowska-Świerkosz, “Active centres on vanadia-based catalysts for selective oxidation of hydrocarbons,” Appl Catal A Gen, vol. 157, no. 1–2, pp. 409–420, Sep. 1997. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).