1. Introduction

Accession of East and Central European countries to European Union in May 2004 created a new situation in European Union transport system. There was written in the White Paper on European transport policy for 2010 [

1]: “As identified by Agenda 2000 trans-European transport network of the candidate countries amounts to some 19000 km of roads, 21000 km of railway lines, 4000 km of inland waterways, 40 airports, 20 seaports and 58 inland ports”. There were 112 mln tonnes of goods exported from NAS to the EU (worth 68000 mln euros), while the imported goods weighed 50 mln tonnes but were worth 90000 mln euros. Bottlenecks were forming at the borders, which created a risk of saturation on the main East-West corridors.

The share of railway transport in East and Central Europe was high – 40%, but it is estimated to be lower to 30% by 2010. Freight traffic decrease started in the nineties and reached its lower point (65% of the 1990 year volume) in 1995, and studies undertaken by different consultants focused on the railways’ financial problems. However, there exists an opportunity to use the potential of the existing railway network, especially on electrified lines. The problem of interoperability of international railway transport, quite apart from under-investment of infrastructure and lack of resources for rolling stock was resulted from different power supply systems (with domination of 3 kV DC), as well as different signalling and track gauge (wide gauge in Baltic states while 1435 mm was used in other countries). General information about railway traction in this region in 2004 is set in

Table 1 based on [

2].

2. Railways in Poland in 2004

Due to its central position, Poland had 4 corridors and the most extended network of electrified railways, so it played the leading role in the region. The main operator, Polish State Railways (PKP), as a state company, has been operating since the twenties and nineties of the XX century, having a hierarchical structure with the vertical dependence of the local area units under the regional directorates, which were under the central office – Directorate of PKP. PKP is quite different from the traffic operating units included within its structures: maintenance and rolling stock service companies, construction companies, repairing factories, sleeper factories, social service units, offices for administration of PKP-owned buildings and flats, health service, railway warden service, etc.

During the years 1990-1995, some measures were undertaken in order to reduce the activity of PKP, trying to get rid of non-transport units as technical support companies and all the service-social areas. The financial state of PKP was weak, and restructuring was required, including structural and organizational changes and personnel reduction.

In 1995, a new act on the state-owned company Polish State Railways was put into law, transforming PKP into a One-Person Company of the State Treasury.

In 1998, the structure of PKP was changed, singling out four operational sectors: freight traffic, passenger traffic, infrastructure and traction-workshop support and eleven technical and administrative vertical units (automatics, telecommunication, power supply, training, buildings, etc.).

In 2000, a new act on the commercialization of PKP was put into law, according to which the division of PKP started with the creation of new companies based on the previously organized structures.

Company PKP PLK (Polish Railway Lines) S.A., based on the Infrastructure Sector of PKP, was created in 2001. The range of activity of PKP PLK S.A. included: management of railway lines and organization of transport and railway traffic, administration of railway lines, technical maintenance of railway lines, assuring continuity and reliability of railway transport, giving operators access to the railway lines, undertaking investments on railway lines. The company managed a railway network length of 23500 km, including 19700 km of being in service (in future about 17000 km), from which 4200 km are main trunk lines, 10500 km of main lines, about 5000 km of secondary and local lines, 3800 km with wholly or partially suspended service. The area of operation included: line and station track, turnouts, civil engineering constructions, overhead catenary, turnout electrical heating devices, electrical installations of illumination of railway areas and buildings, signalling and control devices. The company’s real estate property included: ground, buildings and civil engineering constructions, technical devices and machines, and railway roads. As a result of reorganisation, PKP CARGO S.A. was organised in 2001. The company owns the property of the previous Directorate of Railway Freight Traffic CARGO, which was within PKP structures from September 1999. PKP S.A. is the founder and the shareholder of PKP Cargo. The company’s property in 2001 included: 1763 electrical locomotives (3 kV DC), 2054 diesel locomotives, 25 steam locomotives, and 90185 freight wagons. Main types of locomotives which were being in operation in Poland in 2004 are presented in

Table 2.

Company PKP Regional Traffic Ltd. delivers railway transport services in agglomeration and regional and interregional markets. The properties of the company include: over 5000 passenger wagons, 1100 electric traction units (mainly EN57 type with maximum speed 110 km/h and rated power 0.58 MW, while newer ones EW60 – 0.82 kW), a dozen or so diesel motor wagons, railway station buildings.

3. Modernisation of Rail Rolling Stock in Poland

3.1. Modernisations Since 2004 – Poland’s Accession to the EU

Poland’s accession to the EU in May 2004 and funding from infrastructure aid programs (e.g., Operational Programme Infrastructure and Environment (POIiŚ), Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), etc.) made it possible to begin renovations and modernisation of the railway network and rolling stock. Due to the high costs of purchasing new rolling stock at the time, decisions were made to modernise traction rolling stock and trams. Rolling stock reengineering is one of the methods for improving the standard of operating rolling stock due to the lack of funds for purchasing new rolling stock and domestic production capacity, and it can be a transitional approach to rolling stock renewal. This solution is known and used in several countries and by leading companies [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Issues regarding the scope and forms of rolling stock modernisation in Poland were the subject of numerous conferences, publications and government documents [

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], presenting the policies of operators and manufacturers regarding traction rolling stock. Among the most important issues were those related to modernisation, which were discussed during these conferences [

11]. The main goal of modernising the locomotive fleet is to obtain traction vehicles adapted to transport tasks, as well as to reduce maintenance costs, reduce operating costs, reduce environmental impact, and increase comfort and safety of operation and maintenance.

Initially, this modernisation typically involved retrofitting old locomotives with systems and devices related to traffic safety within the PKP PLK railway network. These include [

14]:

overhaul of the drive system, which can be disabled with traction motor, engine replacement;

modernisation of driver’s cabs and other devices (if installed) used for:

- fuel/electricity consumption measurement,

- event and speed recording;

installing communication elements and systems such as

- radiotelephones,

- data transmission, communication, and control devices (for operating the speed meter, electricity and fuel consumption meter, and other devices).

These activities led to the following effects:

improving the technical and operational parameters of rolling stock;

meeting UIC, Polish, and European Standards requirements and, later, TSI requirements (in particular regarding gauge, track impact [

15], exhaust emissions, noise, and ergonomics);

reducing maintenance costs thanks to:

i. the use of diagnostics and interoperability with IT systems supporting the management of locomotive operation and maintenance,

ii. extending the intervals between repairs and inspections, reducing labour intensity,

iii. improving reliability and increasing availability rates,

iv. reducing fuel/energy consumption, reducing the wear of parts and consumables,

v. improving traffic safety and working conditions,

vi. eliminating harmful materials (e.g., asbestos).

The primary electric locomotives operating during this period were the EU07 (passenger traction) and the ET22 (freight traction). The main modernisation efforts for these locomotives and electric multiple-units (EMU), which were the basis for passenger transport in Poland, are presented in

Table 3.

The socio-economic transformation in Poland after 1989 year resulted in significant changes in the market for industrial plants that had previously been engaged in the production and repair of railway rolling stock, including locomotives and electric multiple-units [

16].

Most of the plants previously engaged in rolling stock repair and overhaul (in Polish - Zakłady Naprawcze Taboru Kolejowego (ZNTK)) were liquidated, and only a few managed to survive and transform into new plants and refocus on rolling stock production and modernisation. Plants such as NEWAG in Nowy Sącz and PESA in Bydgoszcz entered the market as manufacturers. Some ZNTKs were acquired by Western corporations, such as Konstal Chorzów by Alstom, and Pafawag Wrocław by Adtranz/Bombardier, who began manufacturing using new technologies and new market contacts [

17,

18]. Meanwhile, plants such as Fablok Chrzanów, ZNTK Poznań, and Kolzam Racibórz slowly went out of business.

Let us briefly describe the scope of modernisation of the basic electric traction rolling stock in service after 2004, which has been gradually modernised.

3.2. Modernisation of Electric Multiple-Unit Trains Fleet

3.2.1. Modernisation of EN57 Electric Multiple-Unit Train

The EN57 electric multiple-unit train (EMU) is one of the most recognizable Polish trains. It was produced at the Pafawag plant in Wrocław from 1962 to 1993. Over 1400 units were built.

The modernisation of the EN57 series electric multiple-units began in the early 21st century. One of the first modernised units was the EN57-1400, which underwent a major overhaul in the middle of 2002 (currently a Level 5, P5 inspection). Initially, the scope of the modernisation was limited to replacing seats, laminates, floor coverings, windows and installation of electronic displays in place of traditional films. Only in subsequent years did the scope of modernisation begin to expand significantly.

The first extensive modernisations of 75 vehicles of the EN57 series were carried out at PESA Bydgoszcz, ZNTK Mińsk Mazowiecki, and Newag Nowy Sącz in 2006-2007, commissioned by the then-PKP Przewozy Regionalne company. The order initiated a practice that continues to this day of changing the vehicles’ exterior appearance by replacing their front ends with new, streamlined designs made of plastic. For some passengers, this change gave the impression that the vehicle was a completely new vehicle. The installation of the new front ends necessitated a redesign of the driver’s cab, seeking to provide the driver with better working conditions. Furthermore, the vehicles underwent a thorough interior modernisation, including the replacement of walls, floors, seats, toilet cubicles, and the installation of external displays. The vehicle bogies were also modernised, providing slightly more stable train operation. However, the energy-intensive vehicle drive, based on an outdated resistor starter, remained unchanged. In 2007, PKP SKM in Tricity and Koleje Mazowieckie went a step further and, in addition to the work mentioned above, commissioned the installation of internal displays, wastewater tanks in the toilets, air conditioning in the driver’s cabins, reducing the partition walls in the compartments by one-third, making the interior more spacious and safe. Most importantly, they implemented a pulse start instead of the energy-intensive resistor start. This significantly reduced electricity consumption and allowed for a smooth start-up, positively impacting travel comfort. These vehicles were rebuilt again in subsequent years.

In 2009, Koleje Mazowieckie and PKP SKM Tricity commissioned an even more extensive modernisation of their vehicles, which included a complete drive replacement in addition to the work mentioned above. A completely new system based on AC asynchronous motors was used, which doubled the vehicle’s starting acceleration from 0.45 m/s² to 1.0 m/s². The vehicles also gained electrodynamic braking, allowing for electrical energy recovery during braking. The vehicles for Koleje Mazowieckie were additionally equipped with air conditioning in the passenger compartment. The EN71-045 vehicle, identical to the EN57 series but one unit longer, belonging to PKP SKM, had a completely different interior design. Instead of partitions, short windbreaks were installed, some seats were removed, and in the outer sections, the seats were positioned sideways to the direction of travel, metro-style. Due to the two motor cars, its maximum acceleration was even higher, reaching 1.4 m/s², also comparable to metro vehicles. Only one trainset was built with this modernisation. The scope of modernisation mentioned in the previous paragraph was so successful that the mass modernisation of EN57 series vehicles began similarly. A total of 40 different variants of the EN57 modernisation were created, with the largest scope including the replacement of the drivetrain. Individual variants differ from each other in terms of components, interior design, shape of new fronts, type of entrance doors, presence or absence of air conditioning, standard equipment, such as 230V sockets, wireless internet, presence or absence of ticket vending machines, snack and beverage vending machines, and number of toilets. New designations were assigned to the vehicles to distinguish them. Currently, vehicles have been created with the following subtypes: EN57AKM – the oldest, abbreviated as AKM.

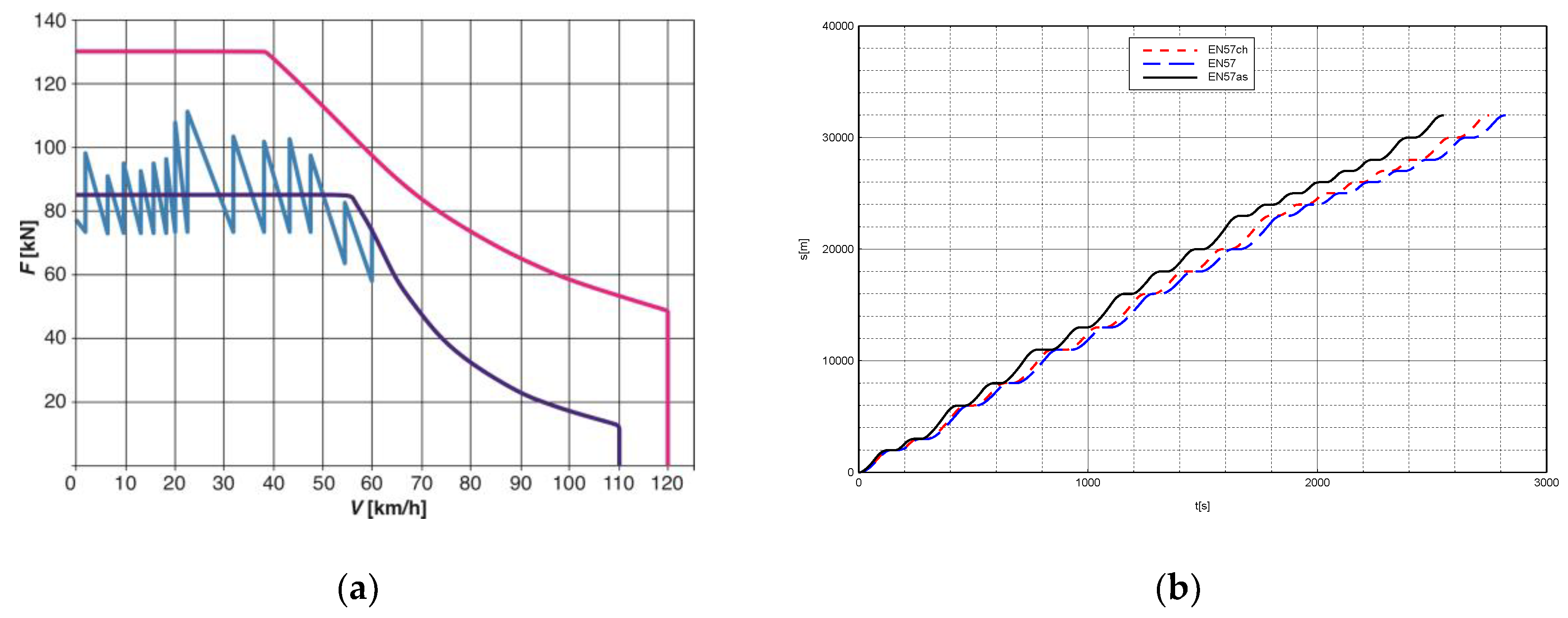

Figure 1 (a) compares the traction characteristics of the EN57 unit before modernisation and the modernised EN57AKM unit.

Currently, modernisations of the EN57 series are being carried out by ZNTK Mińsk Mazowiecki (factory belonging to PESA Bydgoszcz S.A.) and, to a lesser extent, FPS Poznań. It is expected that the ongoing modernisations will be among the last modernisations of units in this series. Carriers and manufacturers are increasingly focusing on entirely new vehicles, which are the future of regional rail in Poland. Re-engineering of EN57 emus allowed for an increase in rolling stock speed. Maintaining DC motors but exchanging rheostatic control (EN57) for choppers (EN57ch) only slightly increases running speed (reducing travel time by 2.6%) while installing AC motors with inverters (EN57as) reduces running time on a 32 km route by 9.6% (

Figure 1 (b)).

The costs of a comprehensive EN57 modernisation can and should be compared to the costs of purchasing a new vehicle [

14,

19]. In this case, the comparison can be made with domestic vehicles such as Impuls (Newag) and Elf (Pesa Bydgoszcz) – both modern and very passenger-friendly, including for people with disabilities. In 2015, in a tender for two brand new four-car vehicles for the Tricity SKM operator, the cost of the Impuls EZT was 17.8 million PLN per train. Meanwhile, the price of a thorough modernisation of the EN57 vehicle is approximately 9 million PLN.

3.2.2. Modernisation of Suburban Railway Transport WKD

The suburban railway line named WKD on a route Warsaw-Grodzisk Mazowiecki was constructed in 1927 and in 2004 was supplied by 660 V DC. In fact, till 2004, the only old rolling stock with DC traction motors and rheostatic control was used. The first modern train with AC motors and inverters, constructed by PESA Bydgoszcz in 2004, appeared on this route and was unsuccessful. Next delivery of modern rolling stock by Pesa of EN97 type (from 2012) and by Newag of EN100 type (from 2016), prepared to be supplied by 3 kV DC voltage, which was introduced in 2016 in this route, and allowed to resign from the old type of rolling stock. Modernisations were co-financed by Swiss-Polish Cooperation Pro-gramme.

3.3. Modernisation of Locomotive Fleet

3.3.1. Modernisation of EU07 Locomotive

The EU07 locomotive (with types of 4E, 303E, 303E, and 303Ec) is a series of standard-gauge, universal electric locomotives primarily used for passenger and freight transport. It was manufactured at the Pafawag plant in Wrocław and HCP in Poznań under an English Electric license based on the EU06 locomotive documentation from 1964-1974 and 1983-1992. These locomotives were designed to haul express trains weighing up to 700 t at a maximum speed of 125 km/h or light freight trains weighing up to 2000 t at a maximum speed of 70 km/h, hence their universal nature (EU stands for electric, universal).

Since 2011, 24 locomotives of the EU07 series were modernised for PKP Cargo. There were two main types: the 303Eb version features improved driver ergonomics, including air conditioning, lighting control, and train communication devices. The control panels, functional seats, and electrically controlled windshield wipers have also been modernised. The cab has also been thermally and acoustically insulated. Modernised traction motors and a modern ETCS-compliant speedometer have been installed. An additional converter to power on-board electronic equipment has also been installed, along with traction motor disconnect switches from the driver’s cab.

The second version, the 303Ec, also features high- and low-voltage electrical cabinets. The high-voltage cabinet design is based on electronically controlled electrical contactors. A computer-based control and diagnostic system, operator panels in the cabs, and a joystick-type controller were also installed, replacing the steering wheel-type controller.

In 2011-2012, Tabor Szynowy Opole purchased and modernised nine EU07 locomotives and two EP07 locomotives previously operated by PKP Intercity.

3.3.2. Modernisation of EP07 Locomotive

The EP07 locomotives (with types of 4E, 303E, 303E-FPS, and 303Ea) are a series of standard-gauge electric locomotives adapted for passenger service (electric-electric, passenger 07). They are rebuilt locomotives of the EU07 series.

Since 1995, some EU07 locomotives (initially, only the 303E type was planned for reconstruction; ultimately, both types – 4E and 303E – have been rebuilt) have undergone reconstruction, which included the installation of new traction motors with a higher permissible operating temperature – LKb535 – and a change in the gear ratio from 79:18 to 76:21. Modernisations have been carried out by companies such as ZNTK Oleśnica, ZNTK Mińsk Mazowiecki, HCP Poznań, and Newag Nowy Sącz. However, changing the gear ratio did not increase the design speed (an unsuitable drive system – the hollow shaft was mounted on slide bearings). Still, it did reduce the engine speed, making it more difficult to operate freight trains with this locomotive. Maintaining the locomotive’s maximum speed has become easier while reducing the failure rate. Starting speed has also increased, especially at higher speeds, which is achieved with less excitation weakening (and therefore greater engine power). The new LKb535 traction motors, instead of the EE541, are designed for a higher permissible operating temperature. The maximum permitted speed of the EE541b motors is 2390 rpm. In EU07 series locomotives, with wheelset rims worn to the maximum 120 km/h speed, the traction motors reach 2380 rpm, while the EP07 motors in the same situation reach only 1962 rpm. This increases their durability. The rebuilt units retained their rolling stock numbers (e.g., EU07-351 became locomotive EP07-351).

In 2006, 74 locomotives of EP07 and EU07 types belonging to PKP Cargo were sold to PKP Przewozy Regionalne. These locomotives were modernised, with the EU07 receiving a new main gearbox. They also received a new paint job, multiple control sockets were removed, the driver’s cabs received thermal and acoustic insulation, new driver and assistant seats, and electric windshield wipers and halogen headlights were installed.

One of the EU07-099 locomotives underwent a minor modernisation: the traction motors were rewired, new half-pantographs were installed, and the cabs were modernised. Locomotives EU07-075, 315, 006, and 007 also had their front ends modernised. In 2012-2013, five EU07 locomotives were converted to the EP07P type. The modernisation included the installation of a static converter, the installation of high-voltage and low-voltage cabinets, the overhaul of the traction motors, the installation of new dashboards in the driver’s cabs, and air conditioning. An LED display was installed at the front end.

During further modernisation, during a level P5 overhaul, two EP07 locomotives were converted to EU07 locomotives, although EP07 locomotives retain greater durability due to the reduced speed of the traction motors. All worn components were replaced during the overhaul, while the hollow shaft slide bearings were retained. In the case of two EP07 locomotives, the gear ratio was changed. The driver’s cab was equipped with new seats and new thermal and acoustic insulation. All locomotives were modernised at ZNTKiM Gdańsk and ZNTK Oleśnica.

3.3.3. Modernisation of ET22 Locomotive

Work on the locomotive, originally designated type 7E, continued until 1966, and at that time, it was planned that the prototype would be built at Pafawag around the turn of 1967/68. Ultimately, the first two vehicles, whose type had meanwhile been changed to 201E following a change in regulations, were built in late 1969 and designated ET22-001 and 002 by PKP. Contrary to their designation, they were assigned the ET22 series, intended for electric freight locomotives.

Since the end of production of the 201E type locomotives in 1989, PKP did not purchase any other locomotives for hauling freight trains for over a decade, so at the beginning of the 21st century, the need arose to modernise its existing vehicles. On December 23, 2003, PKP Cargo signed a contract with Zakłady Naprawcze Lokomotyw Elektrycznych (Electric Locomotive Repair Plant) in Gliwice for the thorough modernisation of one ET22 series locomotive. The conversion was to produce a prototype that would provide, among other things, better working conditions for the driver, easy operation and cost-effective operation, increased reliability and safety, improved driving characteristics, and reduced environmental impact. In 2004, the modernisation to the 201Em type was completed, according to documentation prepared by the Institute of Rail Vehicles “Tabor”. The converted ET22-315 electric locomotive was designated ET22-2000, and due to its successful operation, the carrier decided to order a series of modernisations. On September 12, 2007, a contract was signed for the reconstruction of 49 ET22 series locomotives, and in December, an additional four modernisations were ordered. In 2009–2010, ZNLE Gliwice completed further conversions to the 201Em type, producing ET22 electric locomotives numbered 2001 to 2027. In mid-August 2010, PKP Cargo decided to reduce the modernisation scope of this series and ultimately discontinue it.

The primary goal of modernising the ET22 locomotive was to reduce maintenance costs, modernise the main and auxiliary circuits, upgrade the locomotive’s running gear, improve driver working conditions and reduce noise. The scope of the modernisation can be summarized as follows:

changes in the design of the first and second stage suspensions: the first stage of the suspension was rebuilt to provide individual wheelset guidance; coil springs and hydraulic dampers were introduced; the wishbone and leaf spring system was eliminated; the existing axle box guides were replaced with guides with trapezoidal cutouts, facilitating assembly operations and featuring increased durability of the metal-rubber elements; in the second stage of the suspension, eight Z502a metal-rubber supports were replaced with twenty large-sized flexi-coil springs (five per bogie side);

changes in the locomotive control method: the electrical circuits and brake are controlled by a microprocessor system that includes, among other things, automatic start control, set-speed travel, braking, slip detection and elimination, and on-board diagnostics; The existing classic (contact) travel controller, as well as pneumatic brake valves and conventional control panels, have been eliminated; the new panels have been adapted to the needs resulting from the control system requirements and ergonomics, thus separating the execution and information levels. The driver has an operator panel, enabling communication with the system. The operator panel displays numerical data and messages that support the decision-making process or inform about actions performed by the system automatically without the driver’s involvement;

application of a new type of high-speed circuit breaker: the outdated WSp1600 electromagnetic circuit breaker has been replaced with a new-generation DCN-L 3/1.6 ultra-fast vacuum circuit breaker, which switches off short-circuit and overload currents by countercurrent under vacuum conditions. This circuit breaker, in addition to having internal overvoltage protection, limits the generation of overvoltages;

a comprehensive change in the method of recording events and driving parameters: the current system, based on a mechanical speedometer recording data on tape about the locomotive’s operation, has been replaced with an electronic system capable of recording and storing dozens of freely selectable parameters; the parameter recorder is functionally linked to the locomotive control system;

application of new main converters: the previous LKPm368 rotating main converters have been replaced with PSM-80 static converters based on IGBT transistors; each converter is powered by the traction line and has two outputs – the first is an AC output with parameters of 3×400 V/75 kVA, primarily used to power the fan motors and main compressors, and the second is a DC output of 110 V/5 kW, mainly intended for charging the batteries, powering contactor coils, and for other low-voltage electrical devices;

modification of the traction motor fan drives: before modernisation, the fans were powered by DC motors, which required frequent inspections and replacement of consumables and were characterized by relatively low efficiency. After modernisation, the traction motor fans are powered by AC motors. Air is drawn in from outside the locomotive, not from inside the engine compartment as before – this eliminates the frequent and troublesome phenomenon of negative pressure in the driver’s cab.

improving of brake control: the locomotive retains its pneumatic brake system, but instead of conventional driver valves (main and auxiliary), electric actuators transmitting control pulses to a pneumatic board with a control valve are used. Brake control can be performed directly by the driver by reducing the set speed or intentionally applying a combined brake (or an auxiliary brake). Automatic brake control without driver intervention is the result of speed correction (“downward”) by the set speed system, which is a component of the microprocessor-based locomotive control system;

application of new main compressors: inefficient, emergency, and noisy piston compressors driven by DC motors supplied by the traction line were replaced with modern screw compressors driven by AC motors. Compressor control is fully automated and driver-independent. The main compressors operate in alternating modes, meaning that if the air pressure in the main tanks drops below 0.86 MPa, the control system activates the compressor with a shorter total operating time. The compressors, pneumatic and braking equipment are housed in a special pneumatic container;

replacing of HV contactors and relays: the locomotive was equipped with contactors with asbestos-free quenching chambers (PKG324, SPG400, SPO250M/B) with high switching parameters, much more reliable and cheaper to operate than the previous ones (for example, some spare parts for old types of traction contactors, production of which was discontinued approximately 12 months ago);

modifications of the traction motors: the EE541 traction motors (the same as before the modernisation) were re-wound using class H insulation subjected to vacuum-pressure impregnation, making them much more resistant to moisture and contamination; the brush holders were permanently mounted in the neutral zone using a rotating ring, which eliminates cases of inaccurate assembly that would result in poor commutation and, consequently, excessive sparking under the brushes during locomotive operation; modern brush holders with ribbon springs were used, ensuring constant pressure on the carbon brushes throughout their wear range;

shortening of inspection and repair cycles: the labour intensity of individual tasks will be reduced, leading to lower operating costs for the modernised locomotive;

improving driver comfort: the driver’s cab panel has been completely rebuilt to an ergonomic version, providing easy and convenient access to gauges and instruments. The cab is equipped with high-class acoustic and thermal insulation.

3.3.4. Rolling Stock Replacement Program 2007–2020

The process of strengthening the role of railways in the country’s transport system involves not only investments in rail infrastructure but also the purchase and modernisation of rolling stock [

20]. The rolling stock replacement program implemented by carriers and transport organisations is steadily improving the condition of rolling stock, which allowed energy and CO

2 emission reduction [

21].

In the EU 2007-2013 perspective, 14 projects were implemented under the Infrastructure and Environment Operational Programme, involving the modernisation/purchase of rolling stock for interregional connections. The total value of these projects amounted to PLN 6.3 billion (EUR 1.5 billion), of which EU funding amounted to PLN 2.7 billion. 440 units of rolling stock were purchased or modernised.

In addition, 14 rolling stock projects worth PLN 3.3 billion were implemented in the agglomeration transport sector, with EU funding totalling approximately PLN 2.1 billion.

These activities resulted in significant improvements in comfort and safety, and an expansion of the transport options available. In the EU 2014–2020 perspective, PLN 1.9 billion was allocated from the Operational Programme Infrastructure and Environment to modernise/purchase rolling stock intended for interregional and metropolitan connections. These funds have not been fully utilised. Investments in this area are supplemented by projects implemented under the Regional Operational Programmes of individual voivodeships. These are regional investments. Nearly 400 new/modernised rolling stock units were acquired from the Operational Programme Infrastructure and Environment funds. The effects of the projects involving the purchase/modernisation include:

complementing the broad scope of rail infrastructure modernisation work,

making rail transport more attractive by increasing comfort and safety,

improving transport options,

increasing the accessibility of rail transport,

creating a low-emission alternative to road transport.

The quantitative status of electric traction rolling stock over the years from 2004 to 2022 is presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5. The data in

Table 5 show that the rolling stock inventory remained approximately unchanged in 2014-2022. Reductions or increases in rolling stock by type range from a few to 10%. Therefore, the age of rolling stock may be important information.

Table 6 presents the average age of rolling stock at the disposal of passenger carriers between 2018 and 2022. For electric locomotives, the average age is approximately 34 years, which is not ideal for transport operations, while for electric multiple-units, the average age is approximately 25 years. Both datasets demonstrate the state of rolling stock in Poland. Modernisations have not improved the average age of rolling stock but have contributed to its extension.

3.4. Modernisation of the Tram Fleet

3.4.1. Trams in Poland

A study commissioned by the World Bank in the mid-1990s, led by Professor Wojciech Suchorzewski, on the development of public transport systems in Poland, positively assessed the extensive track and network infrastructure in Polish cities, while also pointing out the need to intensify work aimed at improving its technical condition and traffic organization (priorities, integration of urban public transport systems) in order to achieve standards comparable to those in developed European Union countries [

17,

18].

In Poland, in 2004, tram systems were operated by 14 public transport companies (Elbląg, Gdańsk, Gorzów Wielkopolski, Grudziądz, Silesia Conurbation, Crakow, Łódź, Poznań, Szczecin, Toruń, Warsaw, Wrocław) shown in

Figure 2. In 2015, the tram returned to Olsztyn. Currently, tram systems serve 31 cities with a population of approximately 8.7 million. The total length of tram routes in 2004 was 905.7 km, of which 76% were dedicated tracks, along which over 2,300 km of tram lines ran. A high proportion of dedicated tracks is crucial in achieving high speeds with relatively low investment costs, provided that trams are prioritised at intersections.

In 2004, over 3 thousand tram wagons were used, mainly of the old type (105Na with DC series motors and rheostatic control); only a few were modernised with DC motors and choppers or AC motors with recuperation capability. So, due to a lack of enough funds, one of the modernisation methods of tram fleets, specifically in smaller towns, involved buying used trams from tram operators in Western European cities after 25-30 years of exploitation (types as: Duewag M9C, M6S, GT6, GT8N, EI, Pt8, Tatra RT6) [

22]. To have regenerative braking, local companies often re-engineered such models with choppers (DC/DC converters) in case of DC motors or even with DC/AC inverters when AC drives were installed. Acquisition of withdrawn foreign tram and railway rolling stock, their re-engineering: obsolete equipment, ergonomics, Polonization. Even now, in some tram systems, used trams are acquired for modernisation for further use [

23].

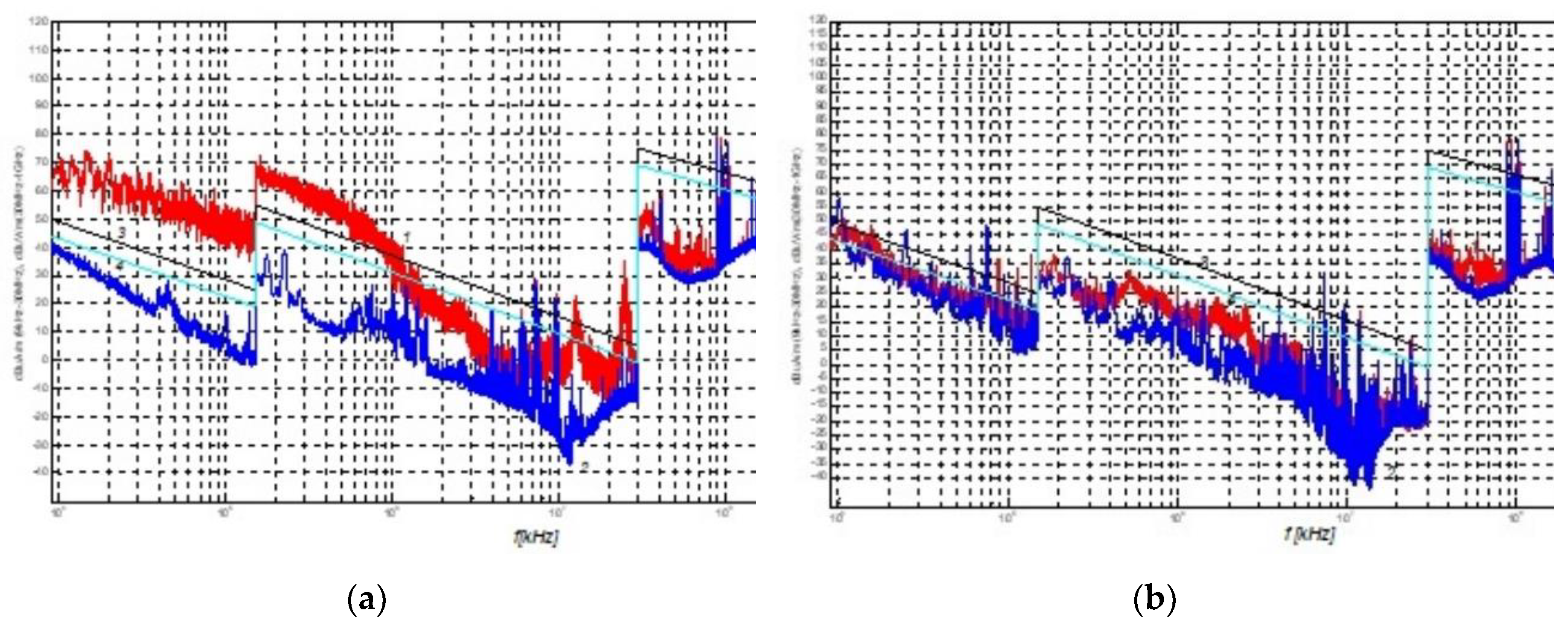

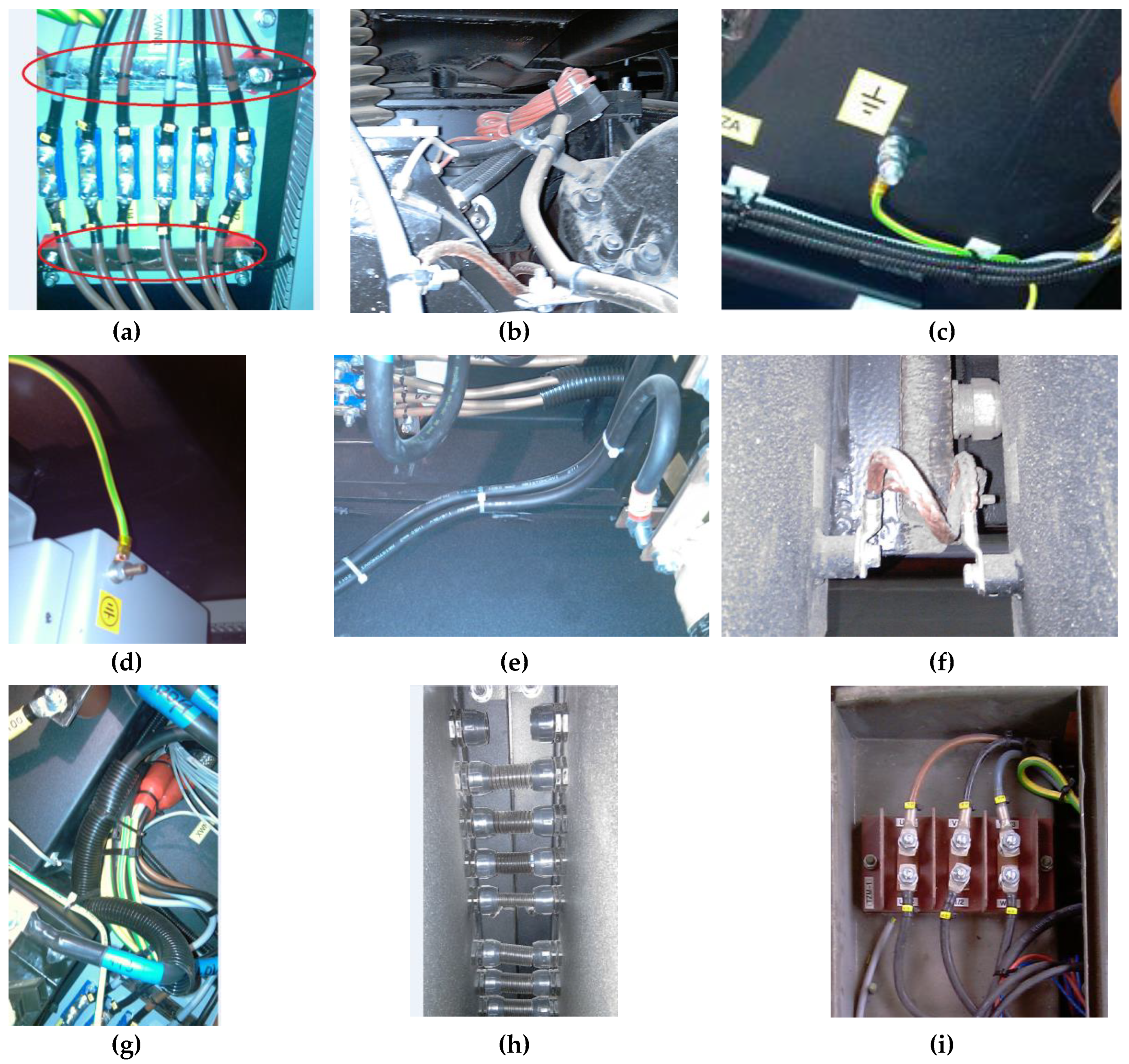

After such modernisation, EMC tests were required, among others, to be passed according to standards [

24]. Due to orientation on low-cost modernisation and lack of experienced staff in many cases, many changes were required in installations and wiring, and more effort was put into reducing emissions to satisfy the limits required by the standards [

25]. Some examples from measurement tests and the reasons for excessive emissions from modernised trams are presented in the following sub-chapter.

3.4.2. EMC Problems of Modernised Trams

During EMC measurements of modernised trams, in many cases, it was found that a lack of staff experience with EMC issues caused failures in passing tests acc. to standards [

24,

26]. Some of the examples, from test measurements done by Division Traction and Electrical Power Economy Division are presented below. An old tram with DC motors controlled by rheostats was refitted with the AC motors and inverters. The results of measurements show exceeding radiated emission in a wide spectrum, as shown in

Figure 3 (a). Magnetic components were measured during tram motion in the frequency range of 9 kHz – 30 MHz, and vertical electric components were measured in the frequency range of 30 MHz – 1 GHz, with significant exceeding of limits observed. The values are observed to exceed the limits for the frequency 1 MHz and range from 12 to 25 MHz. The application of corrective measures and elimination of these errors, and in some cases, changes in the parameters of input filters or the use of EMC filters, allowed the elimination of exceeded emissions and compliance with the requirements of the standards shown in

Figure 3 (b). Examples of incorrect installation solutions in trams that contributed to the occurrence of exceeded emissions are shown in the photos in

Figure 4(a)-(i).

3.4.3. Current Situation

Since 2004, various manufacturers of trams in Poland, with the leading role of Pesa Bydgoszcz S.A. and other companies, have been delivering modern low-floor trams with AC drives and regeneration capability to Polish cities. Some of these trams are also equipped with energy storage devices to store energy during regenerative braking, which reduces energy consumption up to 30%. EU funds support environmentally friendly urban transport, such as trams or trolleybuses. It helped to eliminate high-energy-consuming, not modernised, old rolling stock with DC motors and rheostatic control.

3.5. Warsaw Metro

Currently, the four types of rolling stock are in operation in Warsaw metro; they are shown in

Table 7. In 2004, only the metro trains of the 81 type and the Metropolis type were in operation.

The 81 type metro train is used only on the M1 metro line. It has an outdated design with DC motors, rheostatic control, and no regenerative braking. This type of metro train is the most energy-intensive. It is currently in operation, particularly during peak hours on the M1 metro line. Even if the Metropolis (made by Alstom), Inspiro (made by Siemens), and Varsovia (delivered by Śkoda) metro trains are also currently in operation, the operation of the 81 type metro train results in a significant increase in unitary energy consumption. The 81-type metro train is expected to be in operation till 2025. The withdrawn metro trains of the 81 type were transferred to metro systems in Ukraine.

4. Railway and Tram Rolling Stock of Croatia

4.1. Croatian Rolling Stock Modernisation

Croatian Railways was founded in 1991 from the former JŽ (“Yugoslav Railways”) Zagreb Division [

27], following Croatia’s secession from Yugoslavia. Its vehicle fleet was initially the one it inherited at the time of the breakup of Yugoslavia. It has been modernised over time, and further modernisation is currently being carried out. From November 2012 the three operational companies became completely independent:

HŽ Cargo d.o.o. (responsible for cargo transport);

HŽ Putnički prijevoz d.o.o. (responsible for passenger transport);

HŽ Infrastruktura d.o.o. (responsible for railway Infrastructure).

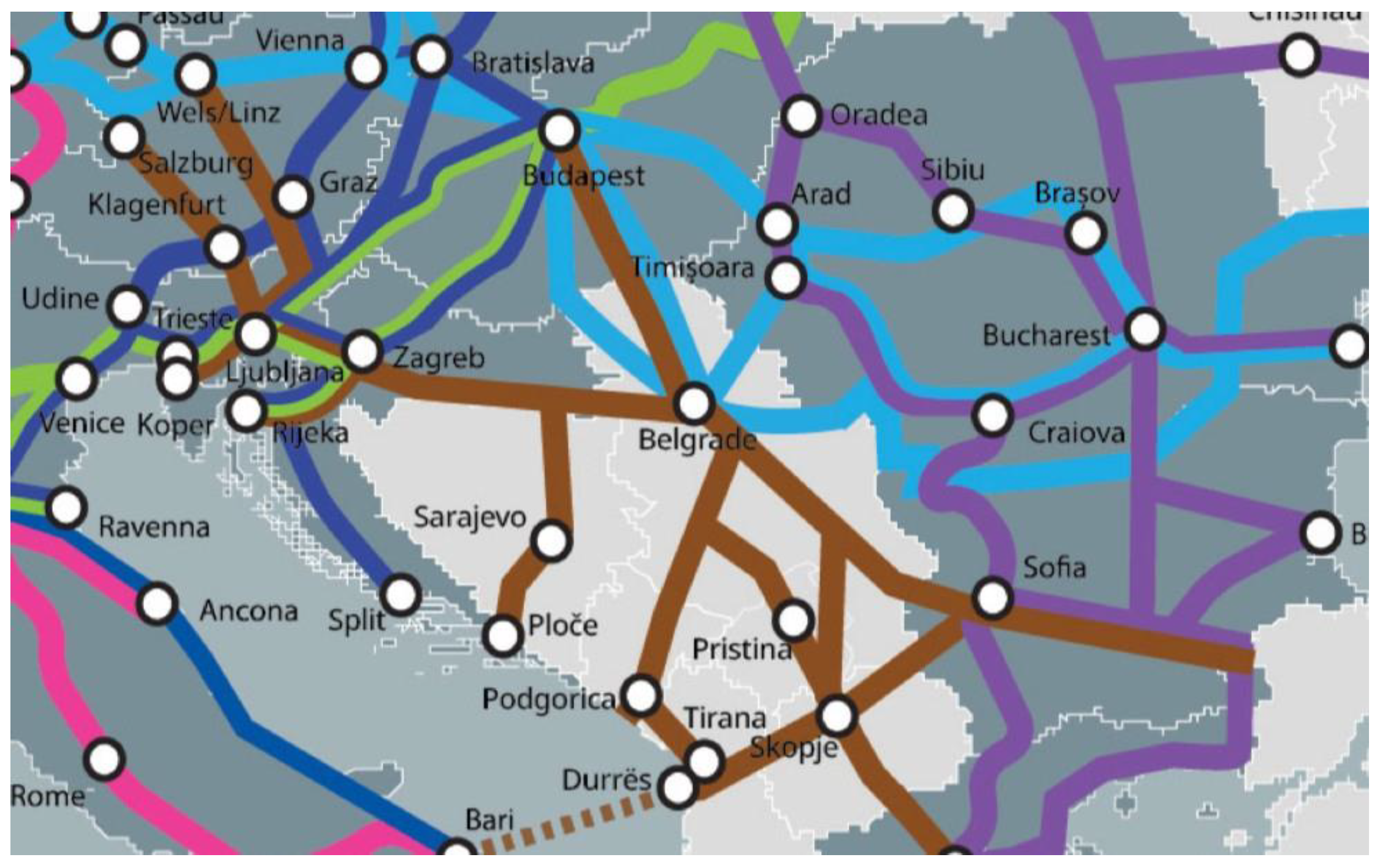

The Croatian railway network [

28] shown in

Figure 5 and consist of:

2617 km of railway lines (2341 km single-track and 276 km double-track);

549 stations and stops;

1448 level crossings;

109 tunnels;

543 bridges;

632 passenger and 102 freight trains operate daily (average);

electrification system: 1010 km 25 kV 50 Hz and 3 km DC.

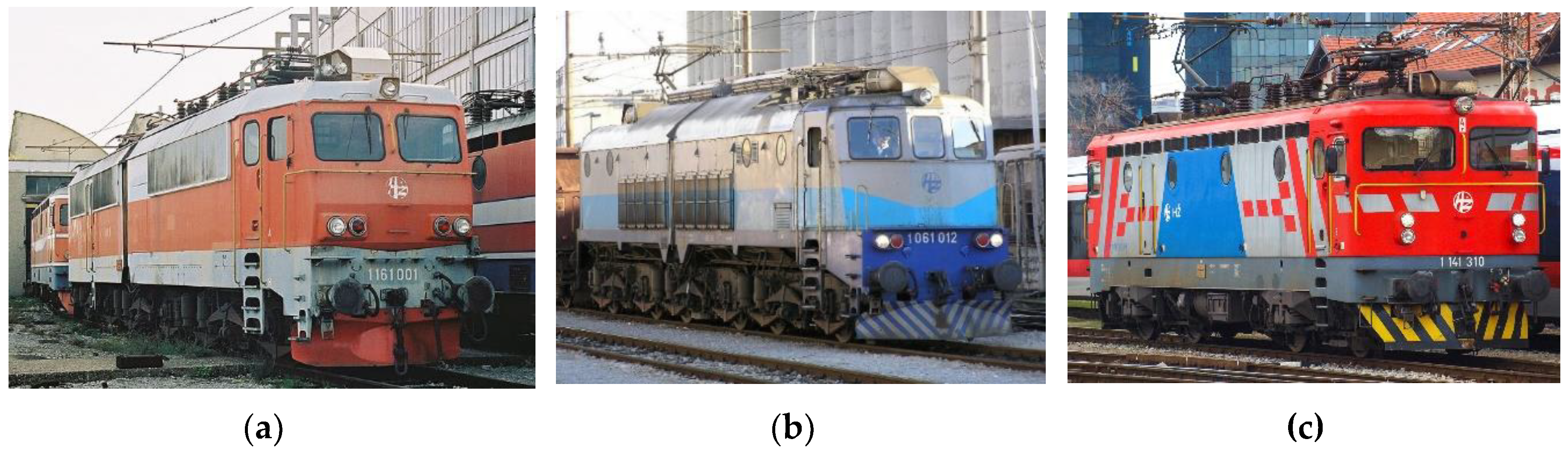

4.2. Ansaldo Breda Locomotives (HŽ Class 1161)

Until 2013, in area of the largest Croatian Adriatic port of Rijeka, a voltage of 3 kV DC was used for the electrification of the railway network in a length of 130 km [

30]. Electric six-axle locomotives HŽ class (type) 1061 (Ansaldo Breda) were used for train traction. After the change of electrification of the railway line from 3 kV DC to 25 kV 50 Hz, two locomotives for voltage 25 kV 50 Hz were produced based on the HŽ class 1061 locomotive shown in

Figure 6 (a) and

(b) [

31]. This was a significant project where the voltage of locomotives previously running on 3 kV DC was converted to operate on 25 kV 50 Hz to match the updated infrastructure around Rijeka’s port. To keep costs down, it was planned to reuse as many parts as possible. Also, newly used parts had to be compatible with the HŽ class 1141 locomotive for 25 kV 50 Hz. The modified locomotive had also to comply with the technical regulations. The bogies were reused, the main frame was reinforced. The traction motors and pantographs had to be modified for the higher voltage. Newly used parts included: the main transformer, new direction switch, new electrical amplifier, new air compressor and some parts of the pneumatic equipment. After two locomotives were produced, serial production never happened, and the project ended unsuccessfully. Technical data:

wheel arrangement: Bo’Bo’Bo’;

max. speed: 120 km/h;

length: 19.44 m;

mass: 129 t;

max. power: 3869 kW (permanent), 4386 kW (hourly);

traction force: 239 kN (permanent), 359 kN (5 minute).

4.3. Končar Locomotive Class 1141-3xx

The Croatian company Končar produced electric four-axle locomotives of the class 1141 with diode voltage selector under the license of the Swedish company ASEA. The locomotives units are now used in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Turkey and Romania.

During modernisation, the entire control and regulation system of the locomotive’s main electric drive was replaced. The existing high-voltage switch and diode-based voltage selector were removed and replaced with four semi-controlled thyristor rectifiers [

32]. This upgrade enabled continuous voltage regulation for the traction motors and allowed individual control over each twin-motor group, which improved the main drive’s adaptability to changes in operating mode and provided effective slip protection.

The electric drive is managed by a microprocessor-based control system, allowing automatic maintenance of the set travel speed, continuous monitoring of the locomotive’s measurement and safety systems, and adjustment of traction mode based on track configuration. The locomotive’s main transformer was modified to have a fixed transmission ratio, while the traction motors and high-voltage equipment were retained in their existing versions. As part of the modernisation, the locomotives were additionally equipped with an electrodynamic brake with a total braking power of 1740 kW, complementing the existing pneumatic brake.

The control desks were upgraded with a new type of main controller, an additional auxiliary controller for shunting, and a display showing essential information on the locomotive’s status and safety system performance. The modernised locomotives were assigned numbers 1141 376-390, based on their delivery sequence, which began in late February 2002. The modernisation was completed in March 2003, with the delivery of the final locomotive from the first generation of thyristorized HŽ 1141 series to Croatian Railways. Locomotives numbered 1141 376-390 differed from the prototype 1141 301 in transmission ratio, with a maximum speed of 140 km/h. The second thyristorization of locomotives of the class 1141 was carried out in 2008 and 2009, and the locomotives were assigned numbers 1141 302-311 shown in

Figure 6 (c). Technical data:

wheel arrangement: Bo’Bo’;

max. speed: 140 km/h;

length: 15.50 m;

mass: 80 t;

max. power: 3860 kW (permanent), 4080 kW (hourly);

traction force: 150 kN (permanent), 236.5 kN (5 minute).

4.4. Tramcar Vehicle TMK 2100

The TMK 2100 tram, shown in

Figure 7, is a tramcar vehicle produced by Croatian companies Končar and TŽV Gredelj in 1997, using parts (bogies and traction motors) from old tram class TMK 201 (produced in 1973 by Croatian company Đuro Đaković). 16 trams have been ordered and delivered for the City of Zagreb public transportation company ZET (Zagreb electric tramway).

TMK 2100 was made in three sections (two-joints), eight-axle tram with four traction motors of 60 kW supplied by choppers with GTO-thyristors [

34]. Operating the tram is facilitated: air-conditioned driver’s cabin and ergonomic control console and driver’s seat. Construction of steel frame, brake equipment, motor cooling, steel construction of control desk and other auxiliary devices for 16 tram sets, were produced by the TŽV Gredelj. Technical data:

system: 600 V DC;

continuous output: 240 kW;

max. speed: 58 km/h;

wheel arrangement: Bo′ 2′ 2′ Bo′;

gauge: 1000 mm;

min. curve radius: 16.5 m;

overall length: 27300 mm;

width: 2200 mm;

floor height: 900 mm;

seated passengers: 45;

standees: 119 (4 pas/m2).

5. Railway and Urban Transport of Ukraine

5.1. Current State and Modernisation Needs

The plan of development of railways, was created in 1840 by Austro-Hungarian Empire. with the basic connection with the main line Bochnia – Dębica – Rzeszów – Przeworsk – Przemyśl – Lviv, which included modern territories of Poland and Ukraine. By this line, the first train was arrived from Vien to Lviv on 4 November 1861. In 1932-1935 created the program and started electrification by 3 kV DC system [

35] on the route Zaporizhzhia – Dolhyntsevo. App. till the end of XIX the network of basic railway connections was formed. Currently, total length of Ukrainian railway network is app. 19.8-22.3 thsnd. km, including electrified lines app. 9.9-10.1 thsnd. km [

36], i.e. 45-50%. The railways use 25 kV 50 Hz AC and 3 kV DC systems. Both electrification systems are equally spreader, correspondingly app. 52% AC and 48% DC relatively to the total length of electrified railway lines or 56.6% AC and 43.4 DC relatively to the catenary length [

37]. During the electrification of existing railway lines of new railway connections, the electrification of railways is mainly performed by the 25 kV AC system, but depending on the location, railway lines also continue to be electrified by the 3 kV DC system.

According to [

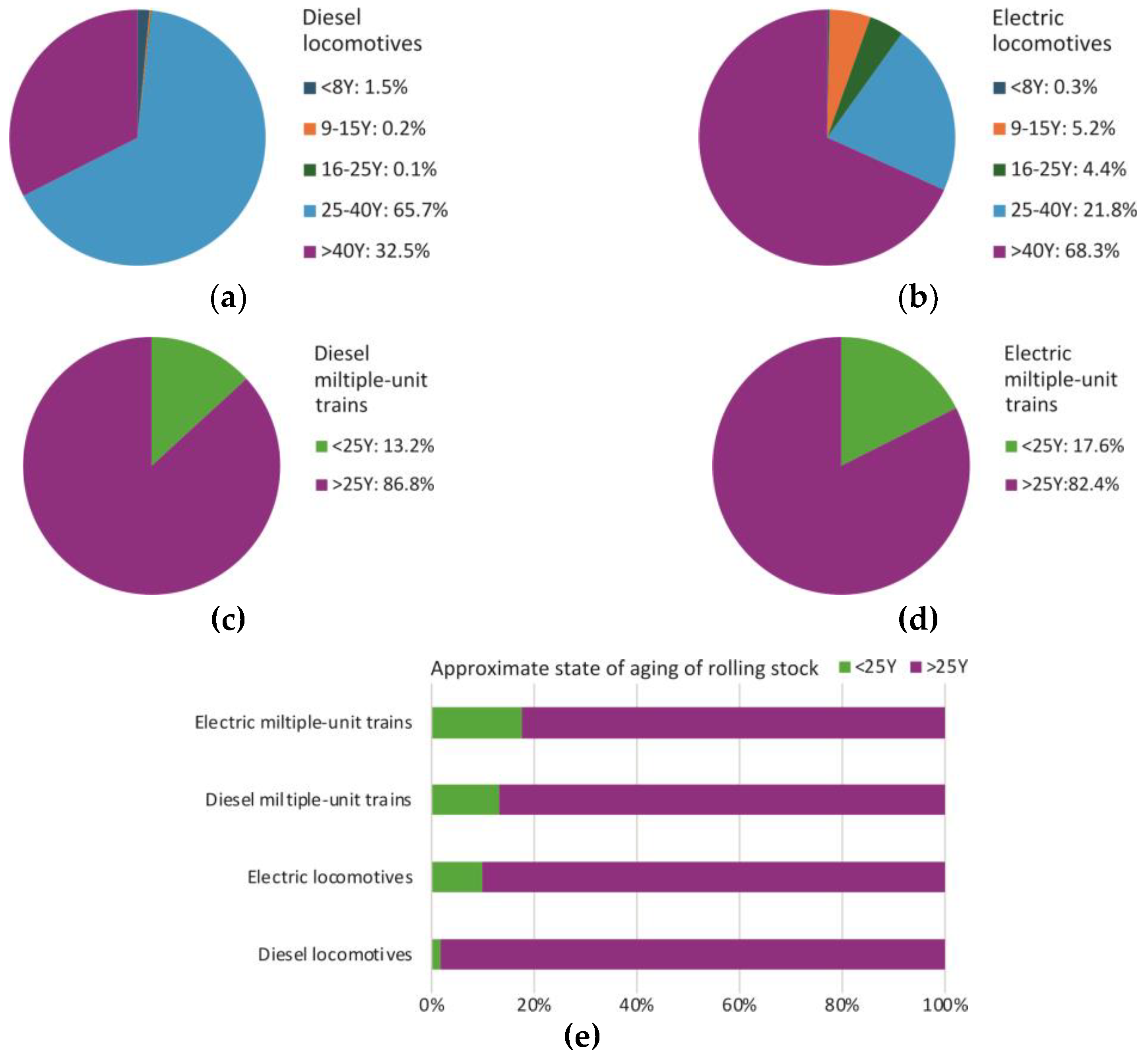

38], Ukraine railways has 1970 diesel locomotives, 1595 electric locomotives, 346 electric multiple-unit trains and 152 diesel multiple-unit trains, but not all of them are in operations. The distribution of railway rolling stock (passenger stock) by year of production is shown in

Table 8 and

Figure 8.

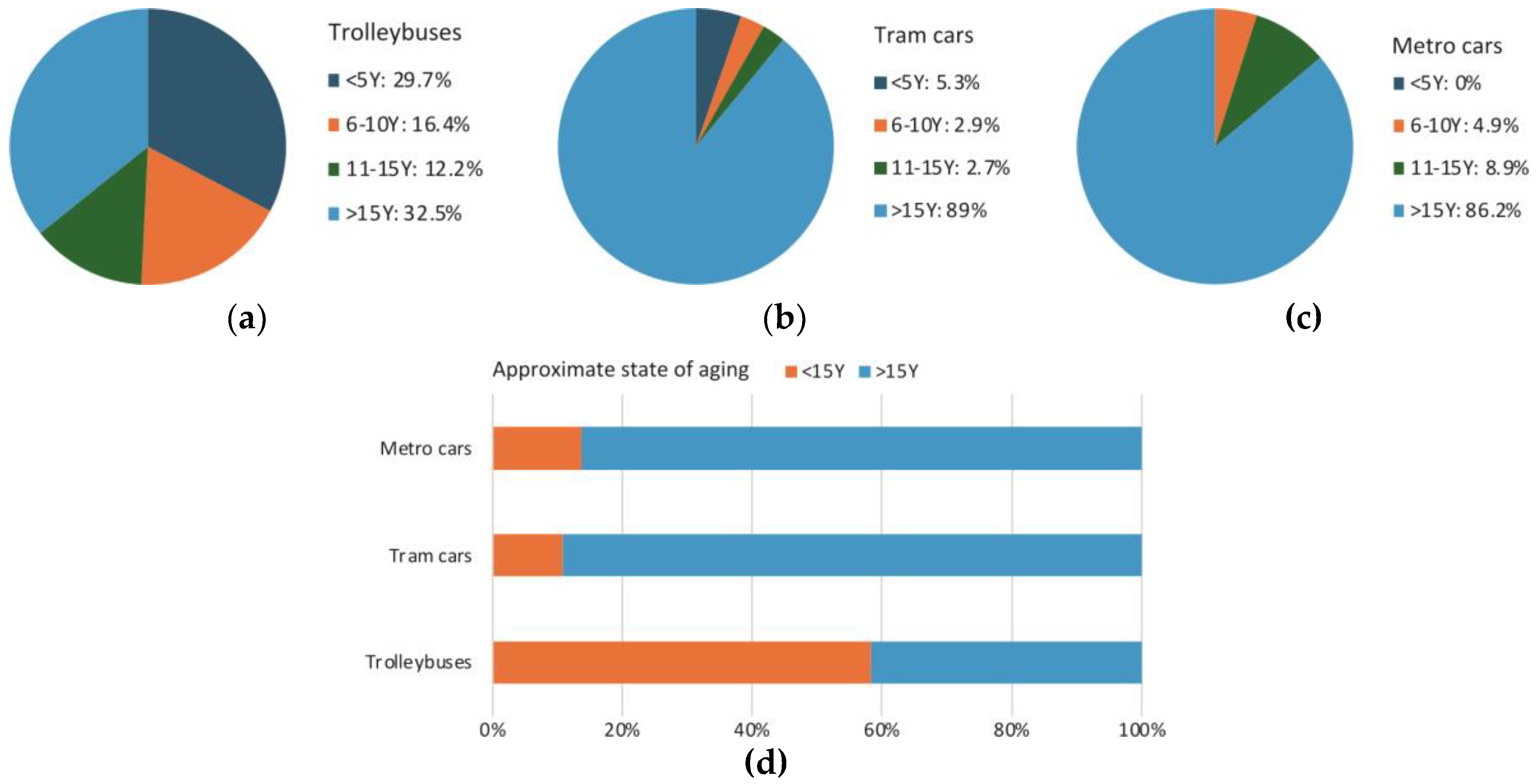

As we can conclude, the last mass deliveries of locomotives and trains took place in the mid-1980s and the biggest part of them were equipped by DC traction motors. The current state of the locomotive park has reached critical importance. Today, the average wear and tear of rolling stock of Ukrainian railways is more than 90%. With a high degree of wear and low rates of renewal of the fleet of rolling stock, the overall technical condition is very low. A significant part of the traction rolling stock has practically served its extended service life and must be replaced by new units or undergo deep modernisation. In the case of purchase, significant investments and a short period of time are required. In this case, it will be economically expedient to modernise or repair the traction rolling stock instead of purchasing new or in parallel with the purchase of new rolling stock, the latter will allow to speed up the replenishment of the existing rolling stock. Urban electric transport (trolleybuses, metro, trams) has quite similar situation. According to [

39], 2667 trolleybuses, 1880 tram cars and 1192 metro cars are in operation in Ukraine. All of them are electrified by DC power supply. The total length of trolleybus roads is 3040 km, tramways 1356 km and metro 113 km. The distribution of rolling stock (passenger stock) by year of production is shown in

Table 9 and

Figure 9. As it is seen, the average wear of urban transport is app. 90%.

In Poland, all electrified transport is based on DC power supply systems only, and the situation looks better. There are a lot of railway vehicles equipped with AC traction motors because of significant investments of the Polish Government with the support of EU funds in a new means of transport and infrastructure. But this doesn’t mean that DC motors are not operated. The older or modernised types of railway vehicles still use DC traction motors. The analysis of the currently used electric vehicles in Poland showed that nearly 86% of electric locomotives [

40,

41,

42], nearly 77% of electric multiple-unit trains [

43,

44], nearly 68% of trams [

45,

46,

47,

48], nearly 29% of metro trains [

43,

49,

50], which will be reduced till 0% in 2025, and 8% of trolleybuses [

51,

52] are based on DC traction motors application.

A significant level of physical wear and tear of rolling stock of Ukraine in railway and urban traffic hinders the effective functioning of transportation. At least 10% of the total number, i.e. at least 800 new units of different rolling stock, need to be purchased every year to replace all existing rolling stock in less than 10 years. In the conditions of limited financing of locomotive fleet renewal programs, there is still a need to extend their service life, even if the standard service life is exceeded. The task is to make this process effective, so re-engineering, modernisation and repairs will be the most promising way from the economical point of view.

All mentioned above allows to conclude that currently, many railway vehicles are still equipped with DC traction motors and are older than 10-25 years old, so there is a significant background and need for re-engineering, modernising or reusing them. On the other hand, the production and supply of new electric locomotives is also associated with certain time and costs. To deliver a new rolling stock, at least 3 years will passe from the agreement to their appearance on the lines. Therefore, the first units of new electric rolling stock unlikely can appear in Ukraine not earlier than 2030. But considering all the realities of today the replacement of old rolling stock by a new one is strongly limited because of a huge financial investment. Based on the above, the most rational decision to provide the railways of Ukraine with reliable DC electric locomotives is a deep modernisation and re-engineering of existing rolling stock, with a mandatory replacement of the bogie frame with a new one. This modernisation will be much cheaper than investment into the new rolling stock and be implemented within 2 years from the moment of allocation of locomotives and financing for these purposes. Considering the aging of rolling stock part above 80-90%, the depth modernisation and re-engineering will prolong the lifetime for the next decade when first new rolling stock will be delivered to the lines and will begin the phased replacement of existing and modernised rolling stock.

5.2. Experience of Repairing, Modernisation and Depth Modernisation

The repairing consists in restoring of functionality, performance and also safety of electrical circuits and mechanical nodes [

53]. The preparing is different types which differed by depth, such as current, middle and overhaul. The last one is a kind of repairing which includes a complex restoration of a locomotive and its return to conditions close to new. The overhaul in comparison to other repairing kinds includes complete disassembly, restoration and even replacement most systems and components with restoration of the original functionality and characteristics of the locomotive and extends significantly the lifetime. At the same time, overhaul can include modernisation and even depth modernisation, which consists of improving functional and technical characteristics compared to the fabric. In general, the depth modernisations is concentrated on the systems and nodes allowing to return the highest reliability and achieve the highest possible traction characteristics for the lowest (i.e. the most optimal) costs including improving the parameters mentioned below [

54]:

increasing specific power;

increasing reliability in order to increase the mileage between overhauls;

increasing the efficiency;

expanding the limits of unification and typification of used units and parts;

improving the design in order to reduce the cost of future repair;

increasing the degree of automation of the operation of individual units and the locomotive as a whole;

improving traction properties;

increasing the loads from the wheelset on the rail;

reducing the dynamic impact on the track;

increasing traffic safety;

increasing the design speed;

improving the working conditions of locomotive crews.

The modernisation should provide effective and maximally automated control of rolling stock traction force and motion speed. The modernisation of an onboard control system concentrates on the full automation as much as possible, including improving the working conditions of the drivers, optimisation of train driving modes, maximisation of the adhesion coefficient use, minimisation the energy or fuel consumption etc. The control system modernisation also requires the changes in power scheme, sometimes dept or even total reengineering, including the replacement of power converter must provide the highest possible efficiency, power factor and the lowest influence on the voltage distortion in the catenary system. All changes in power scheme and auxiliary equipment cannot introduce any time restrictions in the rolling stock operation, as well as must allow it for operation with the pantograph voltage variation in wide range (within the permissible limits). Let as describe some examples of modernisation on example of Ukrainian railways.

Currently, the locomotive fleet of Ukrainian railways is mainly based on freight VL8, VL10, VL11, VL11M, DE1, as well as passenger ChS2, ChS7 electric locomotives of 3 kV DC with DC traction motors that were manufactured in period from the late 60s to the early 90s; a significant part of the aforementioned locomotives still in operation. Having the significant amount of obsolete rolling stock, there is a significant problem with updating the fleet, that is, replacing it with new and modern rolling stock. These conditions, unfortunately, contribute to and lead to the only option as carrying out major repairs and depth modernisation that allows to continue to extend the service life from 15 and up to 55, 60, 65 years. But currently, not all locomotives are suitable for deep modernisation. For example, one of the oldest is the VL8 series of locomotives. The last modernisation was performed in 2011, so app. 150 locomotives are being in operation despite their considerable age from 55 to 65 years. Current condition of these electric locomotives does not allow for the depth modernisation, because of high investments and due to the high cost and fatigue wear of steel structures of key body frame components. The high risk of cracks in structural metal is unpredictable. The duration and nature of the cracks do not allow them to be repaired by performing a complex of welding works and increasing the rigidity of individual components. This carries a high risk of unpredictable cracks in the metal structures. At the same time, the length, depth and nature of the cracks do not allow to repair them by welding. At the same time, there is a huge possibility for basic overhaul of VL11, VL11M, VL10, DE1 and ChS7 locomotives without replacing the frames or depth modernisation with mandatory replacement of the trolley frame with a new one. The overhaul repair of ChS7 locomotives includes different activities from reaping the bogies, wheelsets, traction motors, axillary devices till replacement of wires, insulators, ergonomics and comfort systems, which are usually performed according to instruction [

55]. The activities do not include modernisation of power circuit, application of DC/DC converters, installation of new automation and control system. The analogue situations are in case of modernisation of multiple-unit trains, trams, metro trains and trolleybuses, which consists mostly in repairing and improving the ergonomics and comfort conditions. In case of trams, metro trains and trolleybuses the only some chosen units achieve the modernisation with the change of dive system.

The experience of modernisation of diesel locomotives quite differs from electric locomotives. Currently, diesel locomotives of the ChME3, 2TE10M, 2M62U, TEM2 series are mainly used on Ukrainian railways, and more modern DPKr-3, Pesa 730M and General Electric ТЕ33А and diesel trains and locomotives have been purchased. Generally, the modernisations of diesel locomotives are performed to meet modern requirements for efficiency, safety and environmental friendliness including changes in the power scheme, automation, control, ergonomics and comfort. During modernisation of TEM2 diesel locomotive a new engine of Cummins QST30L2 type and AC traction unit of A735 type were installed. The engine allowed to increase efficiency to 96% and reduce emissions by 25% compared to previous models. The traction unit has an efficiency factor of up to 92%, thereby reducing energy consumption by 15%.

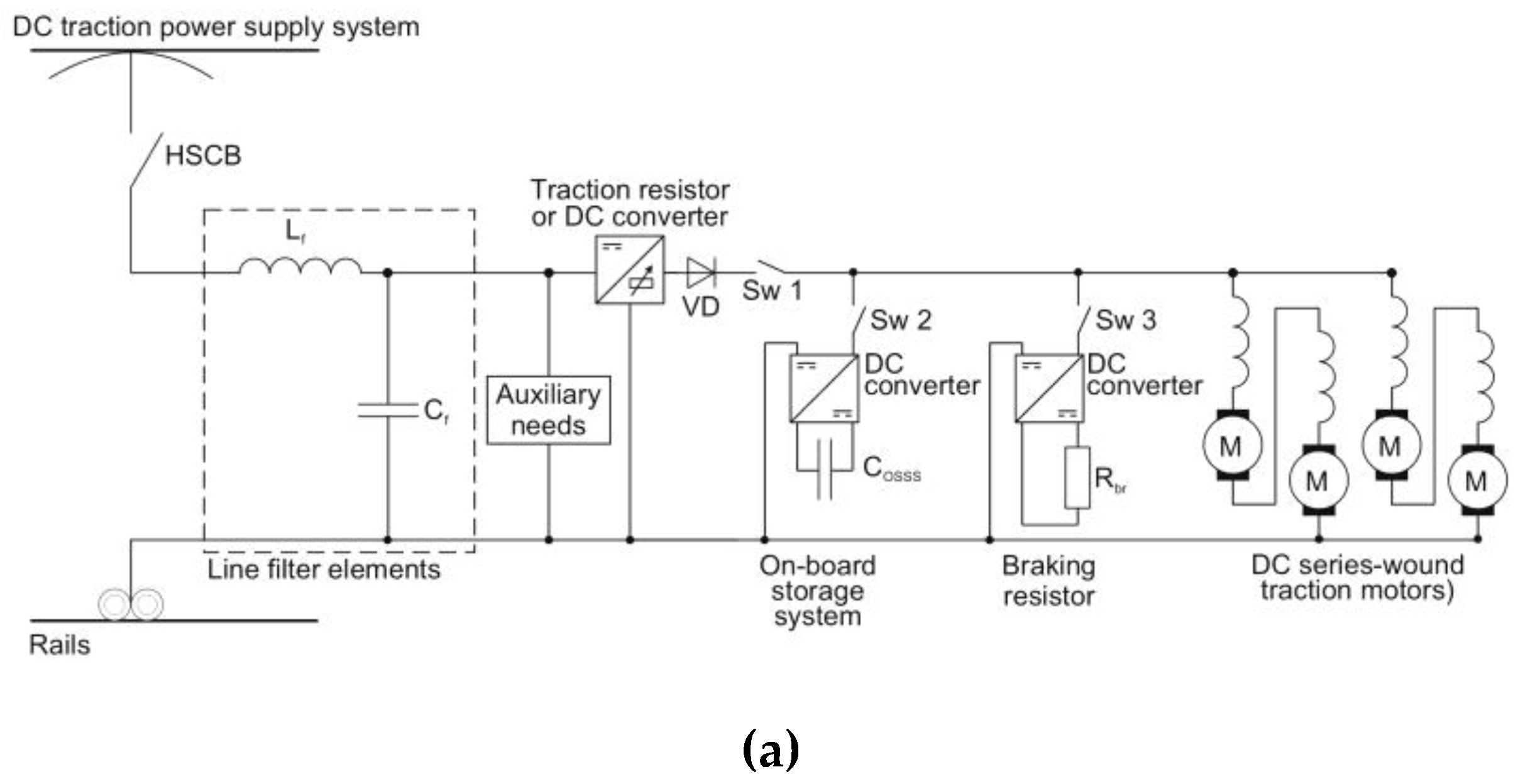

6. Re-Engineering of Rolling Stock into Autonomous or Hybrid One with the Use of Energy Storages

Based on the experience described above of the modernisation of the Polish and Croatian railway transport, the modernisation of the power circuit is reasonable in terms of energy effectiveness. Still, at the same time, it is the most expensive part. There are a variety of ways of power circuit modernisation to increase effectiveness, including the following variants and combinations shown in

Figure 10:

replacement of rheostatic control by DC converters;

replacement of machine excitation (such as motor-generator) by DC converters;

improving the regenerative braking, for example by implementation of on-board supercapacitor storage systems (OSSS);

application of DC converters for any equipment of auxiliary needs (technological needs, such as funs of traction motors).

Finally, replacing the DC power circuit with AC based on inverters and AC traction motors can be alternatively applied to rolling stock modernisation. Since the costs of replacing DC traction motors with AC can account for a significant portion of the costs of modernisation, based on Polish and Croatian experience, it can be said that modernisation using existing DC traction motors is the most optimal in terms of investment payback periods. In addition to schematic solutions, the other issue is the necessity of increasing the energy recovery of the regenerative braking mode (RBM). For this reason, the comprehensive re-design of schemes for different kinds of electro-dynamic braking, i.e. regenerative or rheostatic, in the numerous locomotives is necessary because their power circuits are frequently unstable, faulty or do not have the regenerative scheme. On the other hand, the instability of the automatic control systems of RBM causes instability in the energy recovery process, which causes faults and damages, such as burnout of the traction motors’ windings, etc. There is a significant problem in generating, transmitting and consuming the regenerative braking energy, which can be solved by an autonomous phase mode of regenerative braking (ARBM) of electric rolling stock equipped with an on-board supercapacitor energy storage system [

56]. The autonomy of RBM from the catenary system allows us to leave this energy on the board of rolling stock and prevent its spreading in power supply systems. At the same time, the phaseness of RBM and traction modes allows for optimising the OSSS capacity and reducing its mass-volume indices, especially in the case of multiple-unit trains, trams and diesel locomotives shown in

Figure 10 (a) and

(c). Alternatively, energy stored by the OSSS can also be used not only for traction but also for supplying the auxiliary needs, especially in the case of freight locomotives shown in

Figure 10 (b), which have comparatively long braking distances, and all the recovered energy can’t be stored on board.

7. Conclusions

In CEEC countries, after entering the EU in 2004, a step-by-step transformation of railway transport was observed to accommodate local transport policy to EU rules. The process of strengthening the role of railways, as practically the only sustainable means of transport in the country’s mass transport system involves both investments in rail infrastructure and rolling stock. One of the measures was the reengineering process of railway rolling stock, due to the lack of sufficient funds. The rolling stock replacement programs, in the first years mainly with a variety of re-engineering projects (due to lack of funds for buying new rolling stock) implemented by carriers and transport organisations was steadily improving the condition of rolling stock. This process boosted when EU funds for modernisation of railways became available.

After joining the European Union in 2004, Poland became a member of the European market. For many companies, this was an opportunity for further development, but it became a cause of decline for many others. Rail transport underwent a significant transformation, adapting to the prevailing situation. Most of these companies underwent privatisation; some achieved great success, while others had to close their operations or join a stronger partner. Poland’s accession to the European Union expanded the scope of operations for companies, new markets offered prospects for further development and enabled easier access to new technologies, which were applied in construction of rolling stock delivered not only for Polish railway market but as well abroad. According to PKP PLK, between 2004 and 2023, total expenditure on railway investments – including those co-financed by the European Union – amounted to nearly PLN 116 billion. The work covered approximately 17000 kilometers of track.

The Republic of Croatia plans to invest approximately €6 billion in railway infrastructure and rolling stock by 2032, with most of the funding sourced from EU funds. These investments are primarily focused on the construction, reconstruction, and modernisation of corridor railway lines (part of the TEN-T network), as well as on the procurement of new electric, battery-powered and hybrid rolling stock.

As 60% of the Croatian railway network remains non-electrified and given the questionable economic viability of electrifying many of these lines, the current strategy aims to address this challenge through the modernisation of the diesel-powered vehicle fleet. Upon completion of the battery motor units (BMU) and hybrid trainset procurement, the use of diesel locomotives for passenger coaches’ traction will be phased out, except for certain long-distance services (e.g., sleeping cars, couchette cars and dining cars).

In the freight sector, operations on non-electrified lines remain significantly more complex. While new private freight operators are increasingly deploying modern diesel locomotives, a large proportion of services are still operated with outdated, inefficient and environmentally harmful locomotives powered by two-stroke diesel engines. Although hybridization projects for these locomotives — based on battery and hydrogen propulsion combined with the existing diesel drive — are currently under development, the implementation path remains long and uncertain. Upon completion, a thorough evaluation of the justification, cost-efficiency and overall effectiveness of such hybridization efforts will be required.

Today, Ukraine, under severe fight with Russia, is experiencing not only similar, but even more complicated problems with rolling stock, a significant part of which is outdated and needs to be quickly replaced. Based on the experience of Poland and Croatia, from the point of view of the need for a colossal amount of train fleet, it will be difficult and even impossible to overcome this stage by purchasing new rolling stock, since, in addition to the enormous financial component, the procurement and production procedures themselves can take decades. Therefore, today, there may be no alternative to replacing old rolling stock without the implementation of re-engineering programs for existing rolling stock. After lesser or deeper modernisation, a large number of trains can continue to serve for the next decade. But it should also be added that the modernisation itself will only extend the term and gain additional time for the purchase and production of new rolling stock; therefore, in addition to the modernisation itself, it is necessary to actively search for and purchase new rolling stock that will also subsequently meet European railway standards, which complicates the task.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.S. and M.N.; formal analysis, A.C.; investigation, A.S. and A.N.; resources, A.C. and M.N.; data curation, A.S. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.C., A.N. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and A.N.; visualization, A.N.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained withing the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Comision. White Paper. European Transport Policy for 2010: Time to Decide; 2001. https://obserwatoriumbrd.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/White-paper-European-transport-policy-for-2010-time-to-decide_2.pdf.

- Szeląg, A.; Mierzejewski, L.; Altus, J.; Drabek, J. Railway Electric Traction in the New EU Members – Central and East European Countries. International Conference MET’2005 - Modern Electric Traction 2005.

- Gomes, V.M.; de Jesus, A.M. Additive Manufacturing in the Railway Rolling Stock: Current and Future Perspective. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 53, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, R. Modernizacja Taboru Szynowego – Cele, Zamierzenia, Efekty (Modernization of Rolling Stock – Goals, Intentions, Effects). Przegląd Komunikacyjny 2012, No. 7–8, 10–13.

- Kaewunruen, S.; Lee, C.K. Sustainability Challenges in Managing End-of-Life Rolling Stocks. Front. Built Environ. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Rungskunroch, P.; Jennings, D. A through-life evaluation of end-of-life rolling stocks considering asset recycling, energy recovering, and financial benefit. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tułecki, A.; Szkoda, M. Ecology, energy efficiency and resource efficiency as the objectives of rail vehicles renewal. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABB. Retrofit for the suburban trains in Berlin. https://new.abb.com/news/detail/7185/retrofit-for-the-suburban-trains-in-berlin.

- Bartczak, A. Analiza Taboru Kolejowego w Polsce (Analysis of the Rolling Stock in Poland). TTS 2015, 121780–121785. [Google Scholar]

- Chudzikiewicz, A.; Uhl, T. Nowoczesny Proces Modyfikacji Konstrukcji Pojazdów (A Modern Process of Vehicles’ Modification). TTS 1999, No. 5.

- Railway Conferences (Series), 2014, 2021, 2022, 2023.

- Ministerstwo Infrastruktury. Zmieniamy Polską Kolej (Change the Polish Railways); 2021. https://www.cupt.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/zmieniamy-polska-kolej_770.pdf.

- Ministerstwo Transportu, Budownictwa i Gospodarki Morskiej. Strategia Rozwoju Transportu Do 2020 Roku (z Perspektywą Do 2023 Roku) (Transport Development Strategy until 2020 (with a Perspective until 2023)); Warsaw, 2013.

- Szymajda, M. Czy modernizacje EN57 mają sens (Do EN57 modernizations make sense?). Rynek Kolejowy. https://www.rynek-kolejowy.pl/wiadomosci/czy-modernizacje-en57-maja-sens-75927.html.

- Chudzikiewicz, A. Simulation of Rail Vehicle Dynamics in MATLAB Environment. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2000, 33, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska-Janiak, A. Konkurencyjność Polskich Producentów Taboru Szynowego w Świetle Doświadczeń Wybranych Firm (Competitiveness of Polish Rolling Stock Producers in the Light of the Experience of Selected Companies). Roczniki Ekonomiczne 2015, No. 8.

- Graff, M. Lokomotywy Bombardiera TRAXX F140 MS Dla PKP Cargo (Lokomotywy Bombardiera TRAXX F140 MS Dla PKP Cargo). TTS 2007, No. 12.

- Graff, M. Producenci taboru kolejowego oraz nowe pojazdy szynowe w Polsce. Probl. Kolejnictwa - Railw. Rep. 2021, 65, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyński, J. Life Cycle Cost as a Criterion in Purchase of Rolling Stock. MATEC Web of Conferences, 13th International Conference Modern Electrified Transport – MET’2017.

- Urząd Transportu Kolejowego. Sprawozdanie z Funkcjonowania Rynku Transport Kolejowego (Report on the Functioning of the Rail Transport Market); 2022.

- Pomykala, A.; Szelag, A. Reduction of Power Consumption and CO2 Emissions as a Result of Putting into Service High-Speed Trains: Polish Case. Energies 2022, 15, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesz, B.; Sikora, A.; Szeląg, A.; Karwowski, K.; Gold, H.; Żurkowski, A. Comparison of different tram cars in Poland basing on drive type, rated power and energy consumption. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraśnicki, A. Tramwaje Szczecińskie dostaną prawie 11 mln zł na modernizację tramwajów pamiętających Czechosłowację i Berlin Wschodni (Szczeciń will receive almost PLN 11 million for the modernization of trams dating back to Czechoslovakia and East Berlin). Wyborcza Szczecin. https://szczecin.wyborcza.pl/szczecin/7,34939,31068633,tramwaje-szczecinskie-dostana-prawie-11-mln-zl-na-modernizacje.html.

- EN 50121-2: 2017 Railway Applications - Electromagnetic Compatibility - Part 2: Emission of the Whole Railway System to the Outside World.

- Patoka, M.; Szeląg, A. Considerations on Measurement of Low Frequency Emissions Generated by Traction Vehicles. IMEKO TC-4, Benevento, Italy 2014.

- EN 50121-3-1: 2017 Railway Applications - Electromagnetic Compatibility - Part 3-1: Rolling Stock - Train and Complete Vehicle.

- HŽ – Hrvatske željeznice d. o., o. Hrvatska Tehnička Enciklopedija – Portal Hrvatske Tehničke Baštine (Croatian Technical Encyclopedia – Portal of Croatian Technical Heritage); Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža: Zagreb, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- HŽ – Hrvatske željeznice d. o., o. HŽ Infrastruktura – Network Statement 2025; Zagreb, 2024.

- European Commission. Mobility and Transport; 2025. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/document/download/41528897.

- Nikšić, M.; Mlinarić, T.; Brkić, M. Determining Traffic and Technical Characteristics of New Locomotives on Rijeka-Zagreb Line after the Catenary Voltage Unification. International Conference Modern Electrified Transport – MET’2013, Warsaw 2013, 27–31.

- valjek, I.; Kožulj, T.; Bošnjak, M. Tehničko-Eksploatacijski Pokazatelji i Značajke Vučnih Vozila Hrvatskih Željeznica (Technical-Operational Indicators and Characteristics of Traction Vehicles of Croatian Railways); Zagreb, 2003.

- Gršković, I.; Perić, Z. Tehnički Opis Serije HŽ 1141 - 300 Remontirane i Modernizirane Za Hrvatske Željeznice: Tiristorizacija (Technical Description of the HŽ Class 1141-300 Refurbished and Modernized for Croatian Railways: Thyristorization), 2nd ed.; Končar – Električne lokomotive d.d.: Zagreb, 2002. [Google Scholar]

-

Zagrebački Električni Tramvaj – 105 Godina (Zagreb Electric Tram – 105 Years); ZET 105; Zagrebački električni tramvaj (ZET): Zagreb, 1996.

- Končar - Električna Vozila, d.d. : Tramvaj TMK 2100.

- Polishko, T. World Experience and Features of Railway Electrification in Ukraine. Science and Transport Progress 2009, No. 28.

- Railway Transport of Ukraine. http://proukraine.net.ua/?page_id=461.

- Diakov, V.; Bosyi, D.; Antonov, A. Contact Network of Electrified Railways. Arrangement of Contact Network; Standar-Service: Dnipro, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Transport of Ukraine 2021. Statistical Publication; Kyiv, 2022; p 112. https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2022/zb/10/zb_Transpot.pdf.

- State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Transport of Ukraine 2023. Statistical Publication; Kyiv, 2024; p 92. https://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2024/zb/10/zb_Trans_23.pdf.

- Lista lokomotyw elektrycznych eksploatowanych w Polsce (List of electric locomotives operated in Poland). Wikipedia.

- Urząd Transportu Kolejowego. Tabor Kolejowy (Rolling Stock); Warszawa, 2019.

- Urząd Transportu Kolejowego. Tabor Kolejowy Przewoźników Towarowych - Stan Obecny i Plany Do 2023 r. (Freight Carriers’ Rolling Stock - Current Status and Plans until 2023); Warszawa, 2018.

- Lista elektrycznych zespołów trakcyjnych i wagonów eksploatowanych w Polsce (List of electric multiple units and railcars operated in Poland). Wikipedia.

- Terczyński, P. Elektryczne Zespoły Trakcyjne w Polsce – Stan Obecny i Bliska Perspektywa (Electric Multiple Units in Poland – Current Status and near Future). Technika Transportu Szynowego 2010, No. 5–6, 13–20.

- Lista tramwajów produkowanych w Polsce (List of trams produced in Poland). Wikipedia.

- Górnikiewicz, W. Transport tramwajowy w Polsce – funkcjonowanie i organizacja. Urban Dev. Issues 2020, 66, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izba Gospodarcza Komunikacji Miejskiej IGKM. Komunikacja w Liczbach, Dane Za Rok 2018 (Communication in Numbers, Data for 2018); Warszawa, 2019.

- Graff, M. Nowy Tabor Tramwajowy w Polsce. Technika Transportu Szynowego 2015, No. 7–8, 46–63.

- Metro Warszawskie. Informacje o Taborze (Information about the Rolling Stock); 2021.

- Graff, M. Metro w Warszawie (Metro in Warsaw). Technika Transportu Szynowego 2008, No. 12, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Połom, M. Przemiany Funkcjonowania Komunikacji Trolejbusowej w Polsce w Latach 1989-2013 (Changes in the Functioning of Trolleybus Transport in Poland in the Years 1989-2013); Pelplin: Gdańsk, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacji Trolejbusowej, Sp. z o.o. w Gdyni. Tabor (Stock); 2021.

- Repair, remotorisation or modernisation of a locomotive?. Railway Supply. https://www.railway.supply/uk/remont-remotorizacziya-chi-modernizacziya-lokomotiva/.

- Panchenko, S.; Babayev, M.; Blindyuk, V. Design and Dynamics of Electric Rolling Stock: Textbook. Part 1; UkrDUZT: Kharkiv, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ukrainian Railways. Rules for the Overhaul of Electric Locomotives of the ChS7 and ChS8 Series 105.86000.94504; Kyiv, 2004.

- Nikitenko, A. Regenerative Braking Effectiveness Improvement of DC Supplied Electric Rolling Stock with DC Motors, Ph.D. Thesis; Warsaw University of Technology: Warsaw, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Modernisation of EN57 trams: (a) comparison of the traction characteristics of the EN57 and EN57AKM units; (b) graph of travel time versus distance on a 32 km long section of the Warsaw-Otwock suburban route by EN57 electric multiple-units in various versions: EN57 – basic DC motors and rheostatic control, EN57cz – re-engineered with DC motors and choppers, EN57as – re-engineered with AC motors and inverters.

Figure 1.

Modernisation of EN57 trams: (a) comparison of the traction characteristics of the EN57 and EN57AKM units; (b) graph of travel time versus distance on a 32 km long section of the Warsaw-Otwock suburban route by EN57 electric multiple-units in various versions: EN57 – basic DC motors and rheostatic control, EN57cz – re-engineered with DC motors and choppers, EN57as – re-engineered with AC motors and inverters.

Figure 2.

Rail urban and suburban electrified systems in Poland (T-trams).

Figure 2.

Rail urban and suburban electrified systems in Poland (T-trams).

Figure 3.

Examples of EMS measurement on the tram after modernisation: (a) with significant exceeding of limits; (b) after tram wiring corrections and with allowed limits (the dark blue curve – background field, the red curve – the field of modernised tram during measurements) (results of test measurements done by Division of Traction and Electrical Power Economics of Warsaw University of Technology).

Figure 3.

Examples of EMS measurement on the tram after modernisation: (a) with significant exceeding of limits; (b) after tram wiring corrections and with allowed limits (the dark blue curve – background field, the red curve – the field of modernised tram during measurements) (results of test measurements done by Division of Traction and Electrical Power Economics of Warsaw University of Technology).

Figure 4.

Examples of incorrect installation solutions in trams: (a) shields in cable box not connected to anything (shielding break); (b) no cable nadir needed; (c) ground wires connected through varnish; (d) ground cables connected by varnish; (e) unnecessary loops; (f) equipotential bonding (EMC) through bituminous mastic; (g) general lack of segregation of cable; (h) lack of EMC tightness. Plastic glands, conduit cables, unused holes; (i) screens in cable box, lack of segregation (photos took during test measurements done by Division of Traction and Electrical Power Economics of Warsaw University of Technology).

Figure 4.

Examples of incorrect installation solutions in trams: (a) shields in cable box not connected to anything (shielding break); (b) no cable nadir needed; (c) ground wires connected through varnish; (d) ground cables connected by varnish; (e) unnecessary loops; (f) equipotential bonding (EMC) through bituminous mastic; (g) general lack of segregation of cable; (h) lack of EMC tightness. Plastic glands, conduit cables, unused holes; (i) screens in cable box, lack of segregation (photos took during test measurements done by Division of Traction and Electrical Power Economics of Warsaw University of Technology).

Figure 5.

Croatian railway network and TEN-T corridors [

29].

Figure 5.

Croatian railway network and TEN-T corridors [

29].

Figure 6.

Locomotives:

(a) 1161 class;

(b) 1061 class [

31];

(c) 1141-3xx class [

32].

Figure 6.

Locomotives:

(a) 1161 class;

(b) 1061 class [

31];

(c) 1141-3xx class [

32].

Figure 7.

TMK 2100

(a) and TMK 201

(b) trams [

33].

Figure 7.

TMK 2100

(a) and TMK 201

(b) trams [

33].

Figure 8.

Percentage distribution of rolling stock of Ukrainian railways by the year of production: (a)-(e) for different types.

Figure 8.

Percentage distribution of rolling stock of Ukrainian railways by the year of production: (a)-(e) for different types.

Figure 9.