Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Isolation and Characterization of Heavy Oil-Degrading Bacteria

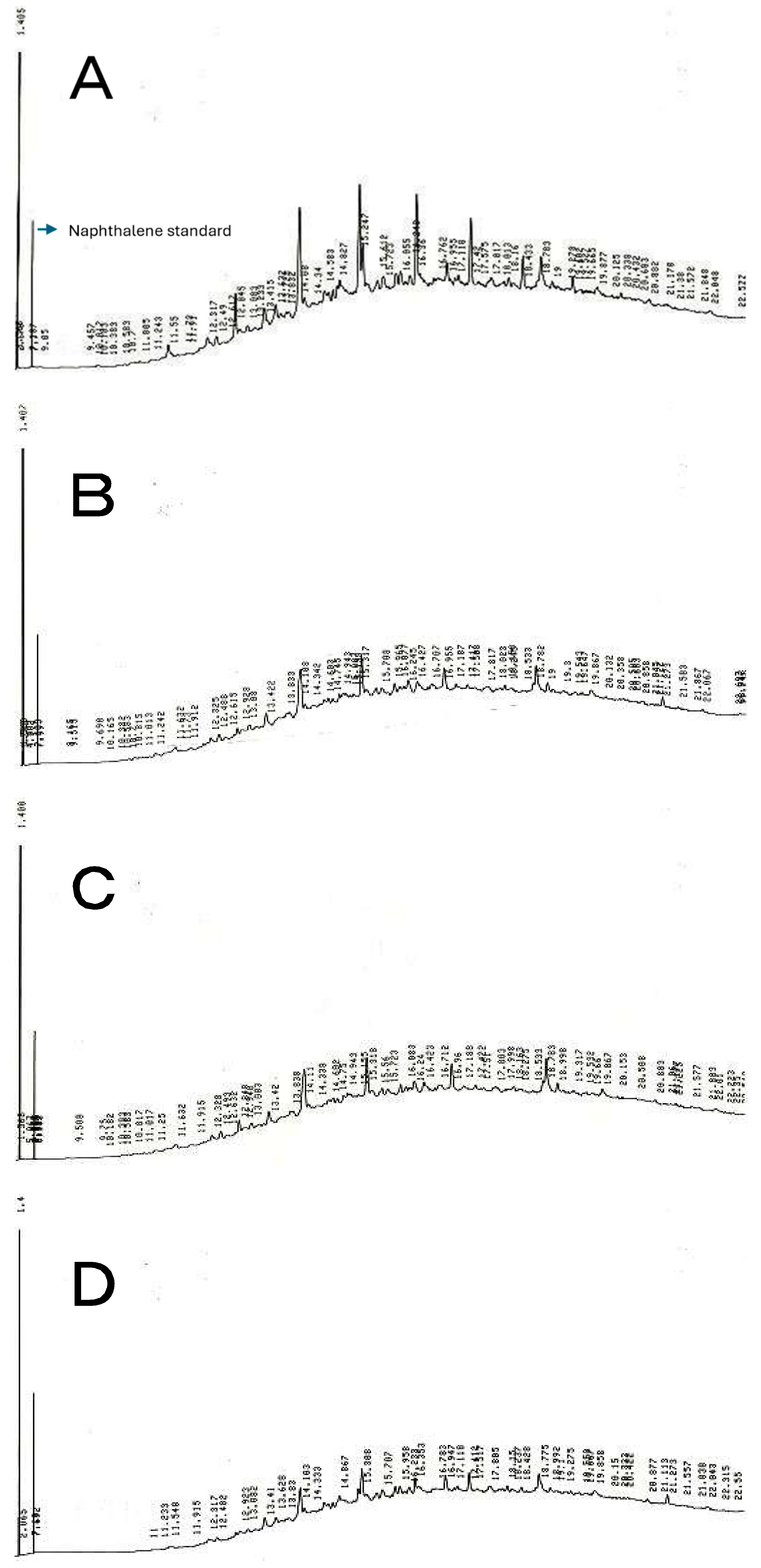

2.1.1. GC analysis of heavy oil biodegradation by isolated strains

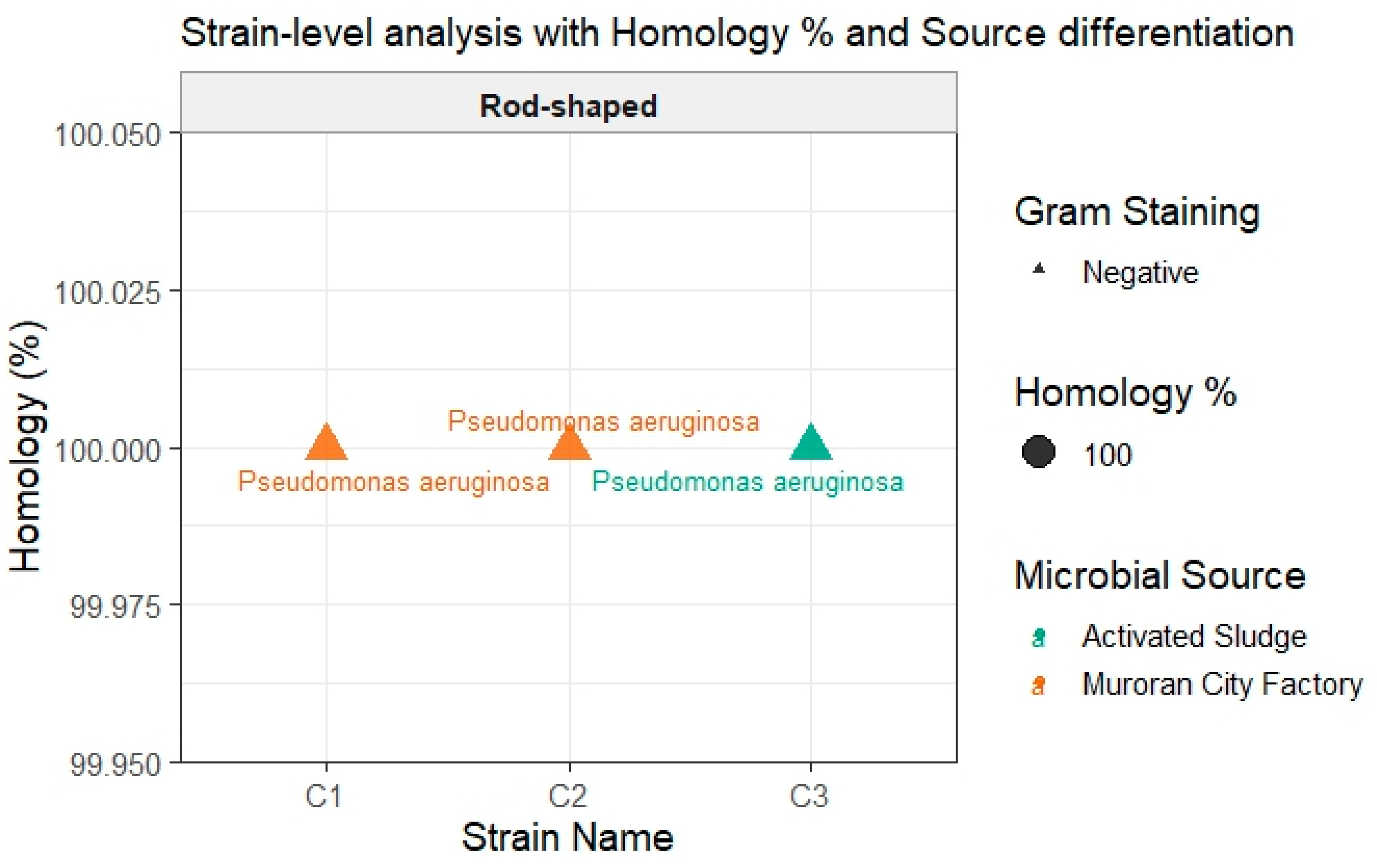

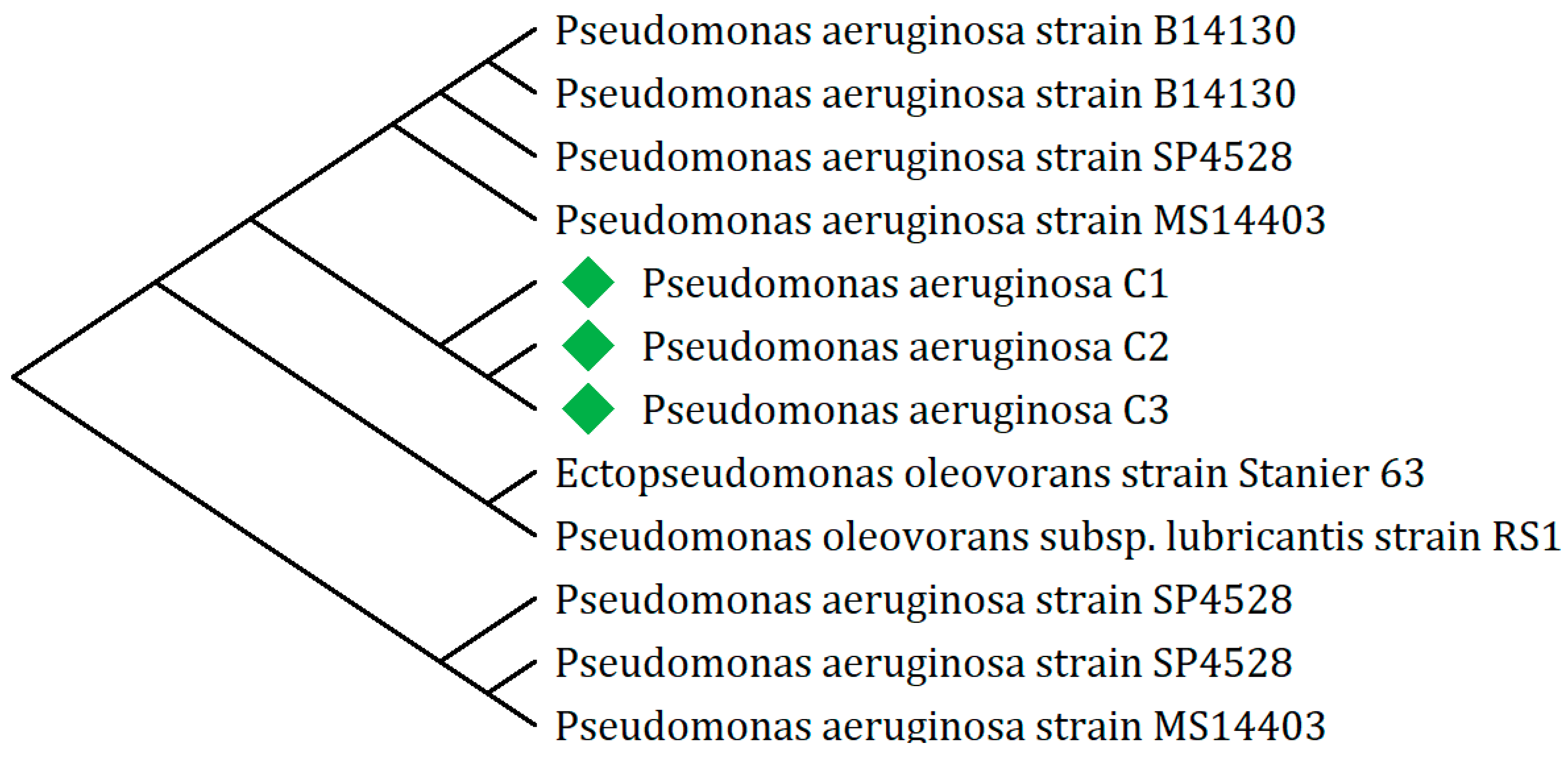

2.1.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Heavy Oil-Degrading Bacteria

2.2. Effect of Temperature on Biodegradation of Heavy Oil by Isolated Strains

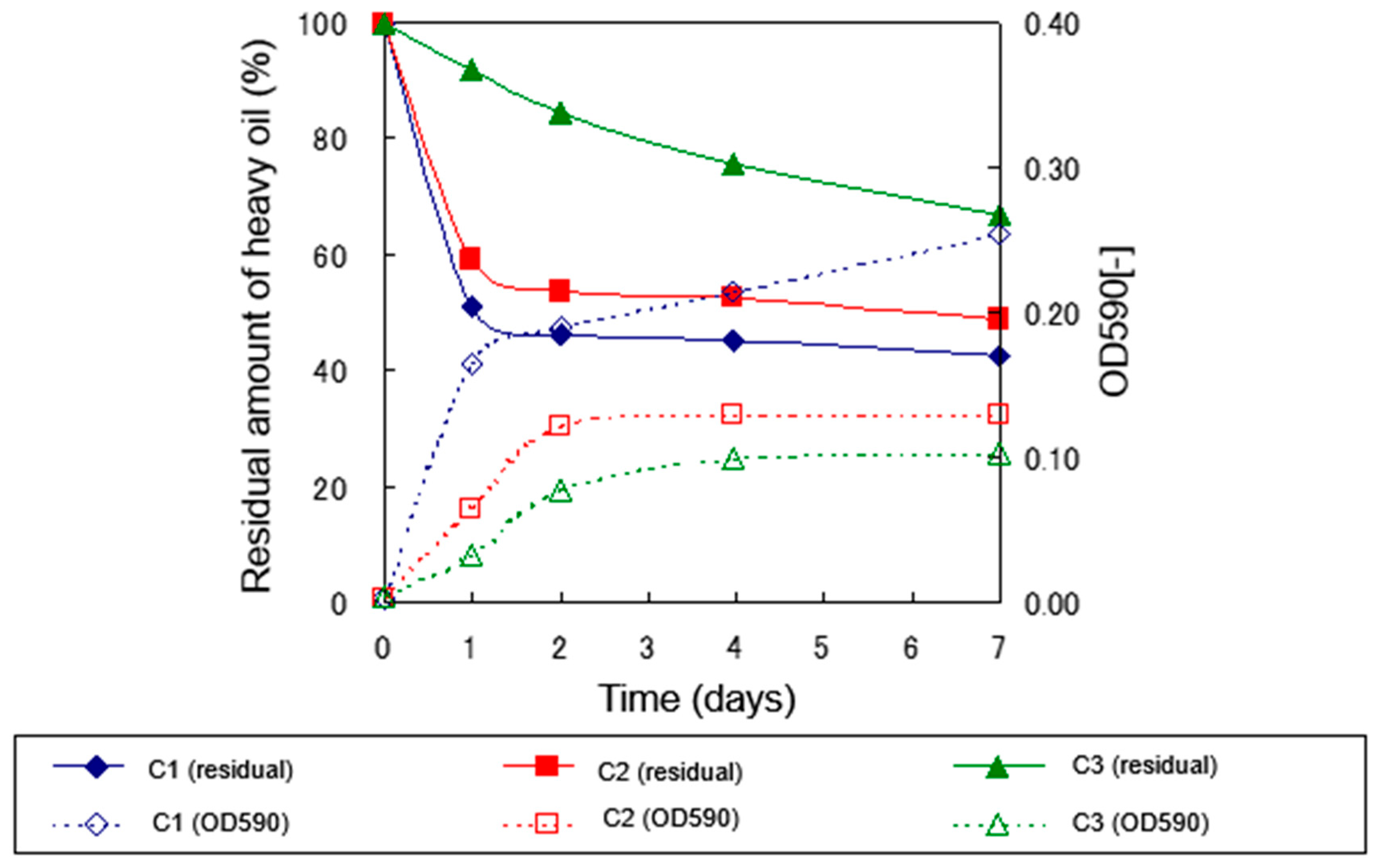

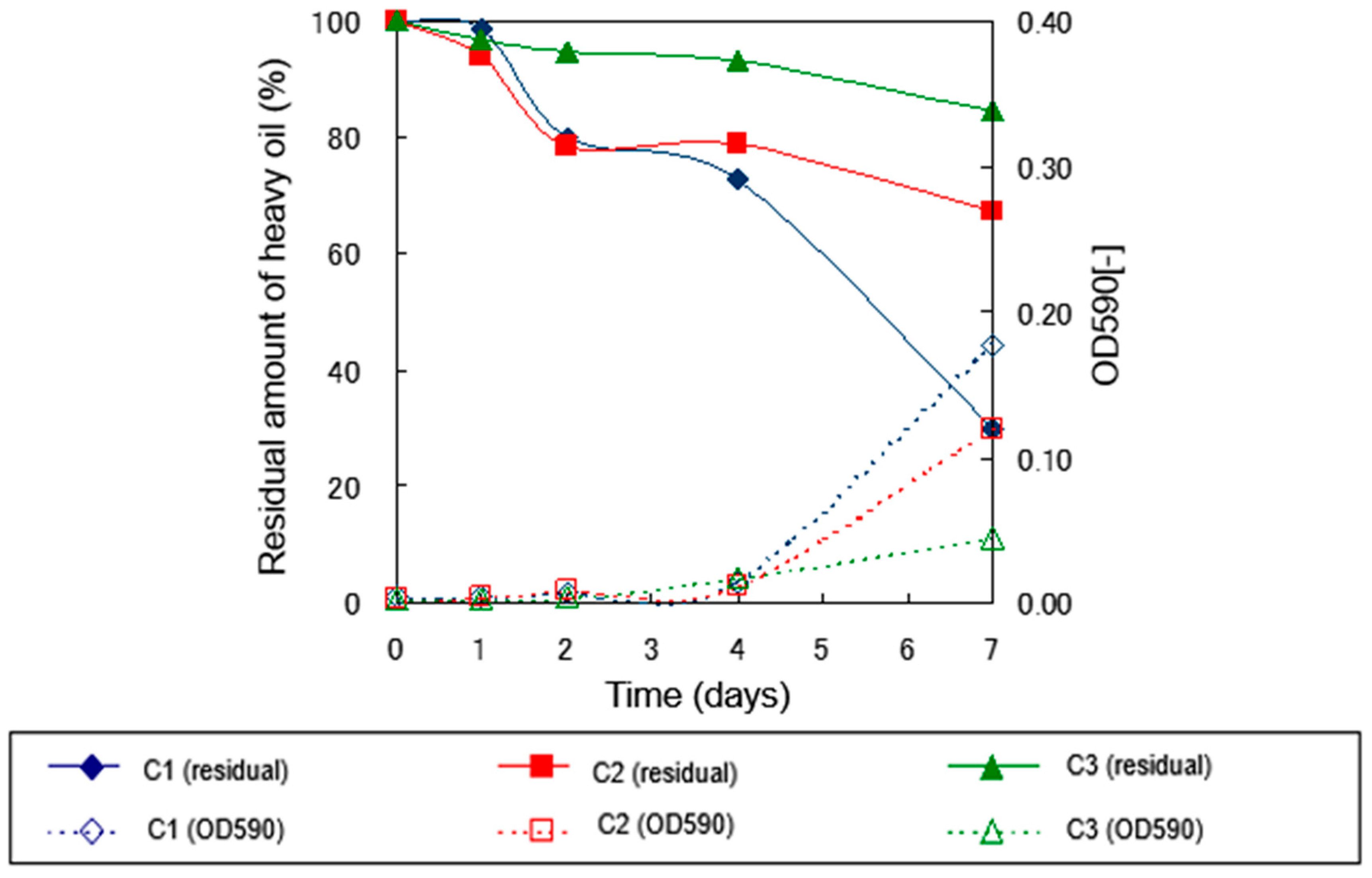

2.2.1. Degradation Experiment under 30°C Culture Conditions

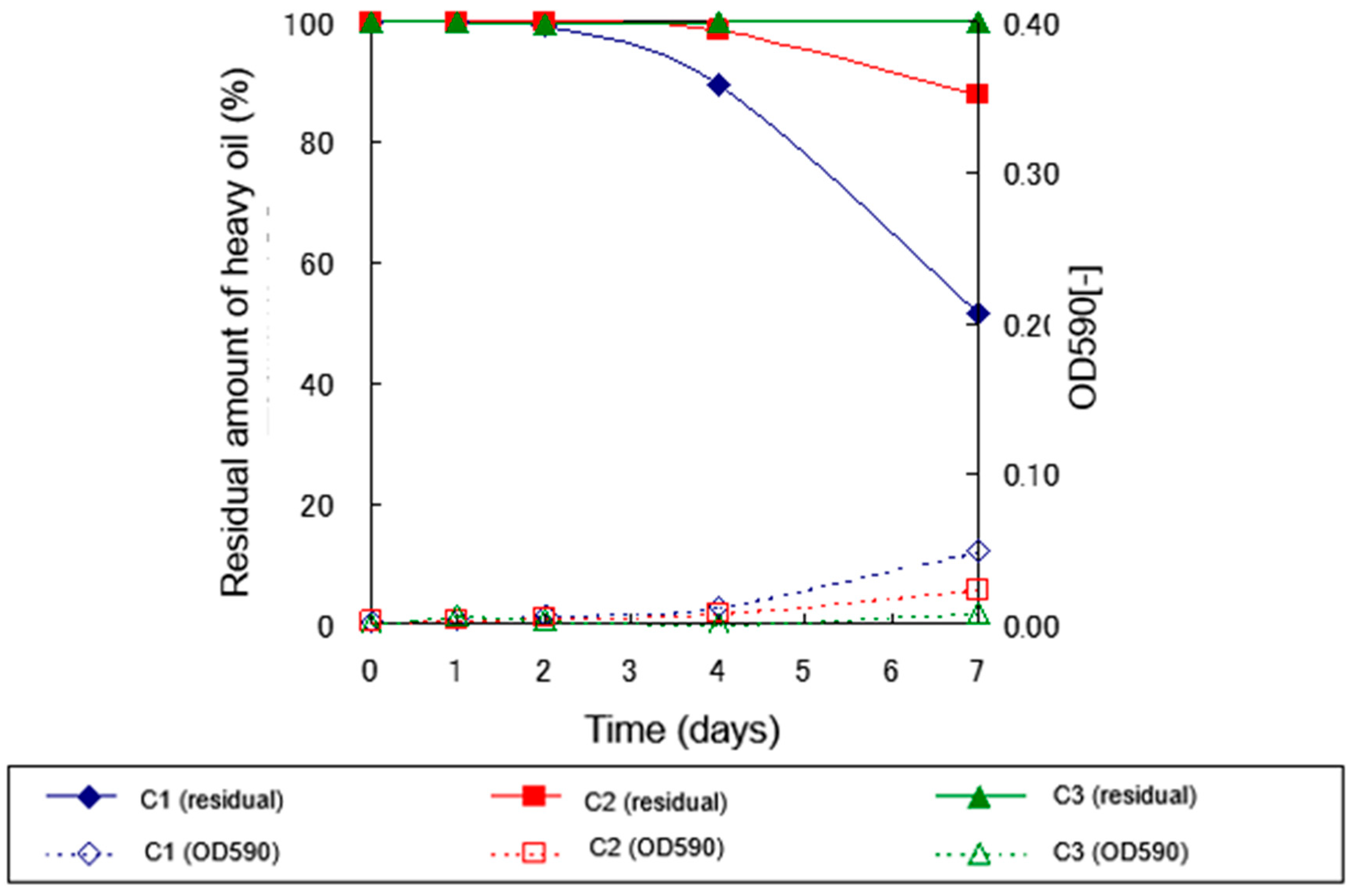

2.2.2. Degradation Experiment under 15°C Culture Conditions

2.2.3. Degradation Experiment under 10°C Culture Conditions

2.3. Long-Term Degradation Experiment at Low Temperatures

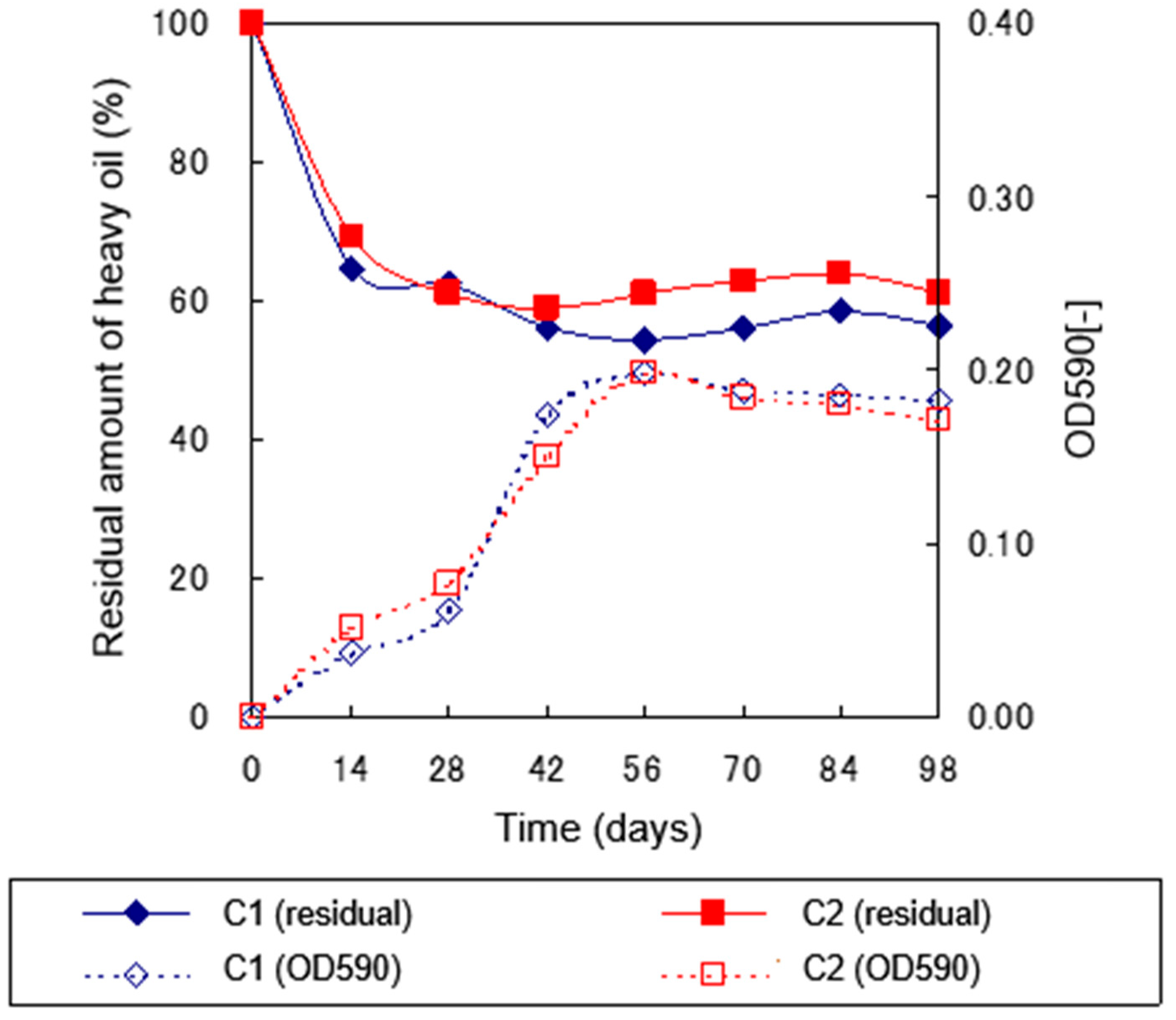

2.3.1. Long-Term Degradation Experiment at 10°C

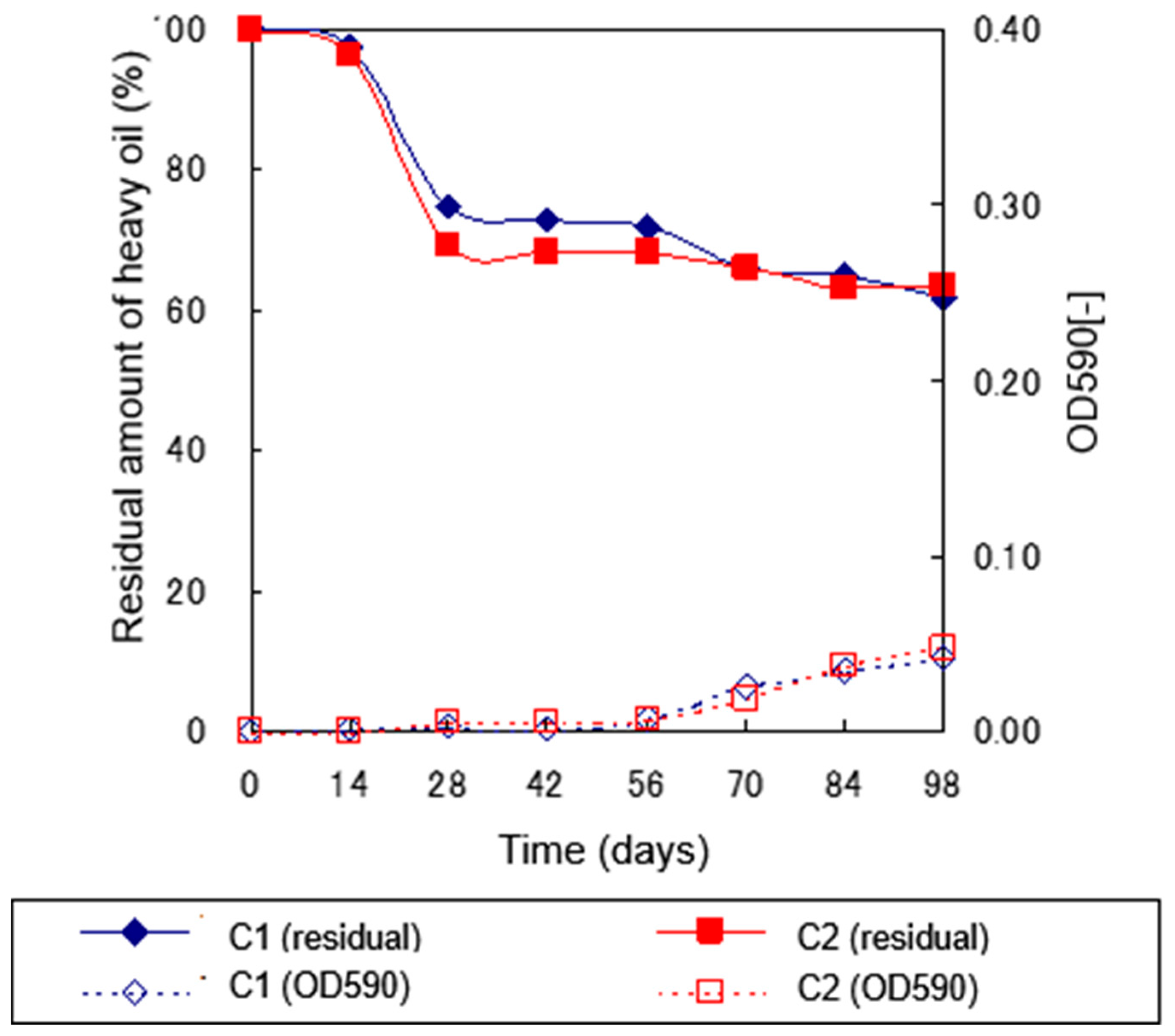

2.3.2. Degradation Experiment under 5°C Culture Conditions

2.4. Heavy Oil Degradation Experiments Using Test Soil

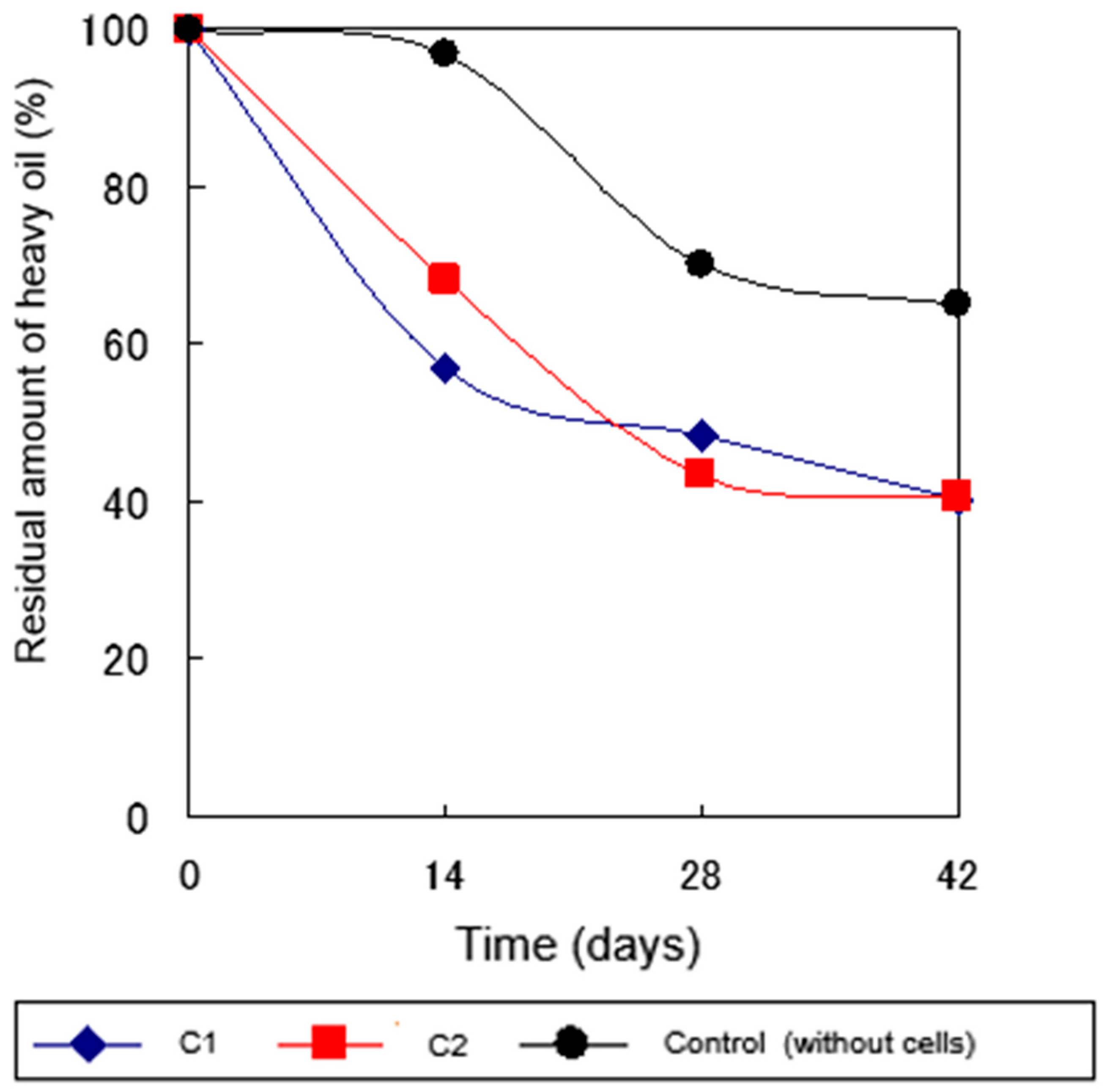

2.4.1. Heavy Oil Degradation in Sterile Soil at 30°C

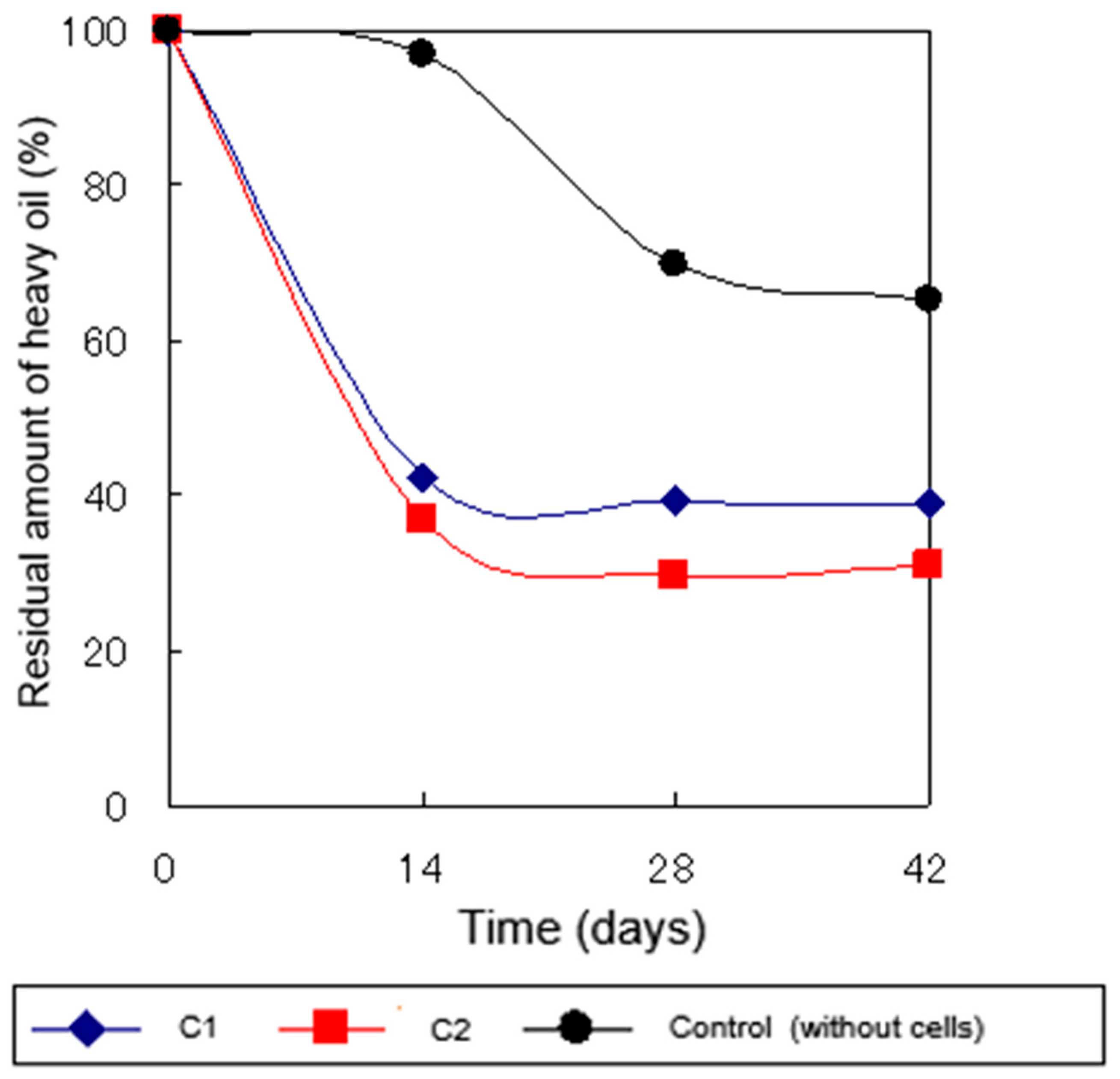

2.4.2. Heavy Oil Degradation in Sterile Soil at 5°C

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Microbial Source, Culture Conditions, and Identification of Heavy Oil-Degrading Bacteria

4.1.1. Microbial Sources

4.1.2. Heavy Oil Used

4.1.4. Preparation of Microbial Inoculum

4.1.5. Enrichment Culture

4.1.6. Isolation of Bacteria

4.1.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.2. Culture Conditions and Analytical Methods

4.3. Heavy Oil Degradation Experiments Using Test Soil

4.3.1. Preparation of Heavy Oil-Contaminated Soil

4.3.2. Medium and Cultivation Conditions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| MSM | Minimum Salt Media |

| HC | Hydrocarbons |

| TPH | Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons |

| LB media | Luria Bertani Media |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| OMM | Organic Mineral Matter |

| HCL | Hydrochloric Acid |

References

- Song, Q.; Zhou, B.; Song, Y.; Du, X.; Chen, H.; Zuo, R.; Zheng, J.; Yang, T.; Sang, Y.; Li, J. Microbial community dynamics and bioremediation strategies for petroleum contamination in an in-service oil Depot, middle-lower Yellow River Basin. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1544233. [CrossRef]

- Evans, F.G.; Nkalo, U.H.; Amachree, D.; Raimi, M.O. From Killer to Solution: Evaluating Bioremediation Strategies on Microbial Diversity in Crude Oil-Contaminated Soil over Three to Six Months in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 05, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Guedes, P.; Mateus, E.P.; Jensen, P.E.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Couto, N. (2021). Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soil in Cold Climate Conditions: Electrokinetic-Bioremediation Technology as a Remediation Strategy. Electrokinetic Remediation for Environmental Security and Sustainability, 173-190.

- Evrard, O.; Chalaux-Clergue, T.; Chaboche, P.-A.; Wakiyama, Y.; Thiry, Y. Research and management challenges following soil and landscape decontamination at the onset of the reopening of the Difficult-to-Return Zone, Fukushima (Japan). SOIL 2023, 9, 479–497. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang (2019), ZHANG, M. (2019). Challenges of solving the problem of soil and groundwater contamination—An interdisciplinary approach—. Synthesiology English Edition, 12(1), 41-50.

- Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Xue, Q. Potential applications of microbial enhanced oil recovery to heavy oil. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 459–474. [CrossRef]

- Kondrat, R. G. (2000). Punishing and Preventing Pollution in Japan: Is American-Style Criminal Enforcement the Solution?. Pac. Rim L. & Pol'y J., 9, 379.

- Mayans, B.; Antón-Herrero, R.; García-Delgado, C.; Delgado-Moreno, L.; Guirado, M.; Pérez-Esteban, J.; Escolástico, C.; Eymar, E. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons polluted soil by spent mushroom substrates: Microbiological structure and functionality. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 473, 134650. [CrossRef]

- Beilig, S.; Pannekens, M.; Voskuhl, L.; Meckenstock, R.U. Assessing anaerobic microbial degradation rates of crude light oil with reverse stable isotope labelling and community analysis. Front. Microbiomes 2024, 3, 1324967. [CrossRef]

- Van Stempvoort, D., & Biggar, K. (2008). Potential for bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons in groundwater under cold climate conditions: A review. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 53(1), 16-41.

- Adedeji, J.A.; Tetteh, E.K.; Amankwa, M.O.; Asante-Sackey, D.; Ofori-Frimpong, S.; Armah, E.K.; Rathilal, S.; Mohammadi, A.H.; Chetty, M. Microbial Bioremediation and Biodegradation of Petroleum Products—A Mini Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12212. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Lv, J.; Wei, W.; Guo, S. Bioremediation of heavy oil contaminated intertidal zones by immobilized bacterial consortium. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 158, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Uppar, R.; Dinesha, P.; Kumar, S. A critical review on vegetable oil-based bio-lubricants: preparation, characterization, and challenges. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 9011–9046. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Quinn, M.; Al-Haddad, A.; Al-Khalid, A.; Al-Qallaf, H.; Rashed, T.; Bhandary, H.; Al-Salman, B.; Bushehri, A.; Boota, A.; et al. Pollution of fresh groundwater from damaged oil wells, North Kuwait. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.; Sartaj, M. Field scale ex-situ bioremediation of petroleum contaminated soil under cold climate conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2013, 85, 375–382. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, N.; Fareed, A.; Alam Naqvi, S.T.; Zeb, B.S.; Amin, B.A.Z.; Khurshid, G.; Zaffar, H. Biodegradation Study of Used Engine Oil by Free and Immobilized Cells of the Pseudomonas oleovorans Strain NMA and Their Growth Kinetics. ACS Omega 2024, 10, 541–549. [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ji, H. Remediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils with Microbial and Microbial Combined Methods: Advances, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9267. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Yang, H. Biodegradation and removal of heavy oil using Pseudomonas sp. and Bacillus spp. isolated from oily sludge and wastewater in Xinjiang Oilfield, China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.M.; Tourova, T.P.; Babich, T.L.; Logvinova, E.Y.; Sokolova, D.S.; Loiko, N.G.; Myazin, V.A.; Korneykova, M.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Nazina, T.N. Crude Oil Degradation in Temperatures Below the Freezing Point by Bacteria from Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Arctic Soils and the Genome Analysis of Sphingomonas sp. AR_OL41. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 79. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, W. Biodegradation of hydrocarbons by Purpureocillium lilacinum and Penicillium chrysogenum from heavy oil sludge and their potential for bioremediation of contaminated soils. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2023, 178. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Altalbawy, F.M.A.; Sur, D.; Karim, S.A.; Chahar, M.; Verma, R.; Juraev, N.; Alamir, H.T.A.; Mohammed, F.; Kadhim, A.J.; et al. Isolation and Identification of Some Crude Oil-Degrading Bacterial From Soil Contaminated With Crude Oil. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Lu, A. Biodegradation of heavy oils by halophilic bacterium. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 997–1001. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, W.; Xue, Q. Biosurfactant production and oil degradation by Bacillus siamensis and its potential applications in enhanced heavy oil recovery. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2022, 169. [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, A. Y., Gladkov, E. A., Osipova, E. S., Gladkova, O. V., & Tereshonok, D. V. (2022). Bioremediation of soil from petroleum contamination. Processes, 10(6), 1224.

- Schreiber, L.; Hunnie, B.; Altshuler, I.; Góngora, E.; Ellis, M.; Maynard, C.; Tremblay, J.; Wasserscheid, J.; Fortin, N.; Lee, K.; et al. Long-term biodegradation of crude oil in high-arctic backshore sediments: The Baffin Island Oil Spill (BIOS) after nearly four decades. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116421. [CrossRef]

- Nordam, T.; Lofthus, S.; Brakstad, O.G. Modelling biodegradation of crude oil components at low temperatures. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126836. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bacosa, H.P.; Liu, Z. Potential Environmental Factors Affecting Oil-Degrading Bacterial Populations in Deep and Surface Waters of the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2131. [CrossRef]

- Zekri, A.Y.; Chaalal, O. Effect of Temperature on Biodegradation of Crude Oil. Energy Sources 2005, 27, 233–244. [CrossRef]

- Rike, A.G.; Schiewer, S.; Filler, D.M. (2008). Temperature effects on biodegradation of petroleum contaminants in cold soils. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons in cold regions, 84-108.

- Bargiela, R.; Mapelli, F.; Rojo, D.; Chouaia, B.; Tornés, J.; Borin, S.; Richter, M.; Del Pozo, M.V.; Cappello, S.; Gertler, C.; et al. Bacterial population and biodegradation potential in chronically crude oil-contaminated marine sediments are strongly linked to temperature. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11651. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.M.C.; Bautista, M.A.; Cramm, M.A.; Hubert, C.R.J.; Semrau, J.D. Diesel and Crude Oil Biodegradation by Cold-Adapted Microbial Communities in the Labrador Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0080021. [CrossRef]

- Chaîneau, C.H.; Yepremian, C.; Vidalie, J.F.; Ducreux, J.; Ballerini, D. Bioremediation of a Crude Oil-Polluted Soil: Biodegradation, Leaching and Toxicity Assessments. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2003, 144, 419–440. [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Liang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Z.; Huo, X. Biodegradation of Crude Oil Under Low Temperature by Mixed Culture Isolated from Alpine Meadow Soil. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, S.; Callahan, T.P.; Haydu, J.; Wood, T.K. Mesophilic aerobic degradation of a metal lubricant by a biological consortium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 65, 620–626. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Isha; Chang, Y.-C. Biodegradability of Heavy Oil Using Soil and Water Microbial Consortia Under Aerobic and Anaerobic Conditions. Processes 2025, 13, 2057. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Sui, H. Solvent extraction for heavy crude oil removal from contaminated soils. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 245–249. [CrossRef]

- Adebusoye, S.A.; Ilori, M.O.; Amund, O.O.; Teniola, O.D.; Olatope, S.O. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in a polluted tropical stream. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 23, 1149–1159. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).