1. Introduction

The observed accelerated expansion of the universe (Riess et al., 1998) [

1] implies that, in the distant past, the cosmos was compressed into a state of extreme density and gravitational potential—conditions under which general relativity (GR) predicts substantial time dilation relative to present-day proper time experienced by a present-day observer. In this paper, we demonstrate that the prevailing ΛCDM–FLRW cosmological framework, as conventionally applied to estimate the age of the universe (AoU), does not account for relativistic time dilation. Rather than discarding the comoving frame, we apply a redshift-dependent correction that transforms it into an observer-centric frame aligned with proper time. This approach retains the structural integrity of ΛCDM while enabling a re-interpretation of high-redshift anomalies—such as the early formation of massive galaxies and black holes—without invoking speculative or exotic physics.

Over the past two decades, increasingly sensitive telescopes, culminating in the launch of the

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), have unveiled a suite of observational anomalies that challenge the standard ΛCDM cosmological framework [

2], which assumes large-scale homogeneity and isotropy, enabling cosmic time to be treated as a globally defined parameter within a comoving frame. Galaxies such as GN-z11[

3,

4], HD1[

5,

6], GLASS-z13[

7,

8], JADES-GS-z11-0[

9] and GS-z14[

10] exhibit stellar masses and ultraviolet luminosities suggestive of extraordinarily rapid structure formation within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang[

11]. Recent JWST observations[

12] have uncovered a population of ultra-high-redshift galaxies in the SMACS 0723 field, including a dwarf galaxy candidate at z = 11.5 with a compact size (< 0.5 kpc) and a stellar mass in the range 10

7.8 – 10

8.2 M⊙, while additional galaxy candidates at z > 11, reported in the JADES field[

13], reinforce the emerging picture of accelerated early structure formation. Several of these galaxies also show signs of chemical maturity, including detectable oxygen and nitrogen emission lines, implying multiple generations of star formation[

14,

15]. The discovery of such seemingly evolved systems so close to the cosmic dawn challenges the standard cosmological model. In parallel, luminous quasars at redshifts z > 7 are found to host supermassive black holes (SMBHs) with masses exceeding 10⁹ M☉[

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Such early and massive black holes are difficult to reconcile with standard accretion models operating within the brief window allowed by the conventional Age of the Universe (AoU), approximately 13.79 Gyr. Similarly, statistical studies of early galaxy number counts and elevated star formation rates (SFRs) at z > 10 indicate a significant overabundance of massive, UV-bright galaxies compared to ΛCDM predictions[

24,

25,

26,

27]. Reconstructions of high-redshift luminosity functions suggest both a steepening of the faint-end slope and an excess of bright galaxies, further intensifying the discrepancy[

28,

29,

30]. Recent spectroscopic follow-up studies have confirmed the existence of several luminous galaxies at z > 10, while revising the redshifts of others, collectively affirming the rapid assembly of early massive systems[

31]. These findings further deviate from predictions of ΛCDM-based semi-analytic models calibrated to Planck cosmology, which anticipate a more gradual buildup of stellar mass and star formation activity[

32].

These findings suggest either the need for exotic astrophysical mechanisms or, more fundamentally, an oversimplification in how cosmic time is modeled. Building on this tension, we argue that these anomalies can be naturally resolved by reinterpreting the cosmological timeline through the lens of relativistic time dilation—specifically as experienced along the worldline of a present-day observer. To this end, we propose the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU): a framework grounded in general relativity that replaces the comoving-frame abstraction of cosmic time with the integrated proper time experienced by an observer in the present epoch. The concept of EAoU has been recently proposed as a relativistic treatment of the cosmic timeline[

33]. By reweighting early epochs accordingly, EAoU significantly extends the effective temporal window available for the formation and evolution of early structures, while remaining fully consistent with ΛCDM dynamics.

The standard Age of the Universe (AoU) is defined within the comoving frame, an idealized coordinate system in which all observers are assumed to move uniformly with the Hubble flow. While mathematically convenient, this frame is not physically realizable, and there is no observational or theoretical proof that it corresponds to our actual frame of observation. As such, the AoU derived from this construct may not represent the proper time experienced along the worldline of a present-day observer. Interpreting observational data through this abstraction can therefore introduce conceptual inconsistencies, particularly when extrapolated to high-redshift epochs.

This tension is underscored by the so-called Hubble Tension, in which the Planck 2018 cosmic microwave background (CMB)[

34] analysis yields H₀ = 67.4 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc[

35,

36], while distance ladder measurements using Cepheid-calibrated Type Ia supernovae produce values of H₀ ≈ 73–74 km/s/Mpc[

37]. Most notably a value of H₀ = 74.03 ± 1.42 km/s/Mpc using Cepheid-based calibrations[

38,

39] anchored by multiple distance indicators is confirmed, a result subsequently reaffirmed with JWST's high-resolution observations. These findings, including the comprehensive analysis yielding H₀ = 73.04 ± 1.04 km/s/Mpc[

40], substantially reinforce earlier SH0ES measurements and leave little room for reconciliation through conventional systematic error explanations

This persistent tension deepens the challenge of bridging early- and late-universe determinations of the Hubble constant within the Standard Model of Cosmology (SMC)—namely, the ΛCDM framework grounded in general relativity and an inflationary early universe[

41,

42,

43].

In this paper, we demonstrate that relativistic time dilation is not incorporated into the prevailing ΛCDM–FLRW cosmological framework used to estimate the age of the universe (AoU). Building on this insight, we introduce the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU), which embeds a time dilation factor directly into the cosmological timeline, yielding an observer-centric reformulation of cosmic age. We then extend this reinterpretation beyond age estimates by reformulating the FLRW metric to include a redshift-dependent temporal component, g₀₀ = –f(z)², and by deriving an observer-centric Hubble parameter, Heff(z) = H(z)/(1+z). Together, these developments provide a consistent relativistic framework that links cosmic chronology, expansion dynamics, and metric geometry—offering a unified approach to resolving high-redshift anomalies and the Hubble tension without invoking new physics.

Building on this insight, we introduce the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU)—a novel, observer-centric reformulation of cosmological time grounded in general relativity. Unlike the conventional Age of the Universe (AoU), defined within a comoving-frame abstraction, EAoU expresses cosmic chronology as the accumulated proper time from any given epoch to the present, as experienced along the worldline of a present-day observer. This shift yields substantially extended effective timescales at high redshift, naturally accommodating the formation of massive galaxies, chemically enriched systems, and billion-solar-mass black holes without recourse to exotic physics. In this work, we extend the EAoU concept beyond temporal reinterpretation by reformulating the FLRW metric to include a redshift-dependent temporal term g00 = −f(z)2 and deriving an observer-centric Hubble parameter Heff(z)=H(z)/(1+z). Together, these advances provide a unified relativistic framework that consistently links cosmic age, metric geometry, and expansion dynamics—offering a coherent route to resolving both high-redshift anomalies and the Hubble tension within the ΛCDM paradigm.

2.0. Relativistic Framework and Definition of EAoU

In the standard ΛCDM cosmology, the age of the universe at a given redshift “z” is computed by integrating the inverse Hubble parameter, weighted by the cosmological scale factor[

42,

43,

44]. This yields the proper time elapsed since the Big Bang for a comoving observer. However, this formulation does not account for the relativistic time dilation experienced when viewing early epochs from the present day.

We begin with Einstein’s field equation given by:

Where, is the Einstein tensor (curvature), Λ the cosmological constant, the stress-energy tensor (matter–energy content), and the metric tensor.

The expansion rate in ΛCDM is governed by the Friedmann equation:

The standard Age of the Universe (AoU) from redshift z until today is then given by:

And the total AoU from the Big Bang to the present is:

2.1. Limitations of the Standard FLRW Cosmology with Respect to Time Dilation

In four-dimensional spacetime, the metric tensor g

μν is a 4×4 symmetric matrix:

Under the assumptions of isotropy and homogeneity, the only allowed solution to Einstein’s field equations is the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric. This reduces the metric tensor to a diagonal form in comoving spherical coordinates[

45]:

(Note: in spherical coordinates:μ,ν=0→t;1→r;2→θ;3→ϕ)

This structure confirms that g

00 = −1 and all mixed terms g

0i = 0, eliminating both gravitational and kinematic time dilation effects. The coordinate time t is thus universally identified with proper time

for all comoving observers, enforcing a global synchronization of clocks. For any comoving worldline, the proper time interval satisfies:

While this construction is mathematically consistent, it is physically restrictive. It assumes that all observers move with the Hubble flow and experience identical time evolution — a condition that suppresses relativistic effects such as differential aging and time dilation due to either curvature or recessional motion.

The line element corresponding to this metric is:

This widely used form contains no dependence on gravitational potential or relative velocity. As such, the FLRW metric — despite being a solution of general relativity — does not explicitly encode relativistic time dilation in any operational sense. It models a universe where all comoving clocks tick in perfect unison, regardless of epoch, density, or redshift.

This idealized construction stands in contrast to real cosmological observations. Type Ia supernovae light curves are empirically observed to stretch by a factor of 1+z[

46], directly demonstrating relativistic time dilation. Similarly, spectral and dynamical features of high-redshift galaxies evolve over longer intervals when viewed from the present epoch — effects that cannot be accounted for within a comoving-frame treatment of time.

To illustrate this inconsistency, consider the standard cosmic age integral, restated from Equation (3) for clarity:

This relation defines the age of the universe at redshift z as measured in the comoving frame, where the factor (1+z′)−1 adjusts coordinate time into proper time for a comoving observer. However, this is a coordinate-based prescription, not one derived from physically comparing clocks in distinct relativistic frames. It does not reflect how time would be measured by an observer today looking back at earlier epochs across relativistic distances.

Consequently, the standard FLRW cosmology:

- -

Does not include explicit relativistic time dilation between observers and high-redshift sources,

- -

Assumes a universal proper time across all epochs, contradicting both general relativity and observations,

- -

Yields an age of the universe that underestimates the actual proper time accumulated along the observer’s worldline.

This foundational limitation necessitates a reformulation of cosmic time. We thus introduce the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU), a relativistically consistent framework that restores proper-time differentials across cosmological epochs by replacing comoving coordinate time with the accumulated proper time experienced in the observer’s frame.Top of Form

Bottom of Form

To incorporate relativistic time dilation from the perspective of a present-day observer, we introduce the Time Dilation Factor (TDF), defined as:

Multiplying the standard Age of the Universe (AoU) integrand by TDF reweights earlier epochs to reflect the stretching of time as experienced in the current observational frame. This leads to a modified formulation of the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU):

Substituting TDF(z′)=1+z′, this simplifies to:

In a related paper by the present author[

47] (preprint available), the EAoU expression (equation 11) was rigorously derived by incorporating the time dilation factor into the FLRW framework. This formulation yields the accumulated proper time experienced along the worldline of a present-day observer, offering a more physically meaningful timescale for interpreting the chronology of early cosmic structure formation.

2.2. Reassessment of the Hubble Constant under the EAoU Framework

The Hubble constant H

0 plays a pivotal role in cosmology as the present-day expansion rate of the universe. It is conventionally defined via the relation[

41,

44]:

and operationally inferred from a combination of standard candles (e.g., Type Ia supernovae), cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies, and baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO)[

48]. However, the observed tension between the locally inferred value (e.g., H

0∼73 km/s/Mpc from SH0ES)[

40] and the CMB-inferred value (H

0∼67.4 km/s/Mpc from Planck)[

43] signals a deeper inconsistency in the cosmological framework itself. The EAoU formulation offers a new lens through which this discrepancy may be understood and reinterpreted.

As established in

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2, the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) accounts for relativistic time dilation by integrating along the proper-time worldline of a present-day observer, with the standard (1+z)

−1 factor eliminated. This yields significantly larger age estimates at all redshifts as seen in equation (11):

This integral implies that more proper time has elapsed between redshifts than what is computed under standard comoving-frame formulations. For any redshift z, including z = 0, the EAoU will always be greater than the standard Age of the Universe (AoU). Since,

a larger denominator (i.e., Δt) for the same redshift interval naturally leads to a smaller inferred expansion rate. This reinterprets the observed expansion as

slower than what is derived under the comoving-time formalism.

Hence, we define a relativistically consistent Hubble parameter:

Given EAoU estimates of ~30–45 Gyr, this implies:

This range sits significantly below both Planck and SH0ES values, suggesting that the standard H0 measurements may be overestimated due to the neglect of time dilation effects in cosmic age formulations.

2.2.1. Subtlety: Space Expansion vs. Motion Through Space

It is crucial to emphasize that the Hubble parameter does not measure motion through space, but rather the expansion of space itself in km/s per MPc. This distinguishes it from relativistic and non-relativistic velocities in space in special relativity and requires caution when applying intuitive time dilation or length contraction analogies.

Nonetheless, if relativistic time dilation stretches time intervals in the observer’s frame, then there may be a corresponding need to reassess distance measures as well — including the cosmological interpretation of megaparsecs (Mpc) and luminosity distances — particularly under conditions of high curvature and gravitational potential in the early universe.

Standard cosmology allows for a redshift-dependent expansion rate as shown earlier in equation (2):

However, within the EAoU framework, a more nuanced understanding of H(z) emerges. Since both time and (potentially) spatial metrics are relativistically reweighted, H(z) becomes a frame-dependent quantity. While H0 pertains to z = 0, an EAoU-consistent cosmology must develop a redshift-corrected Heff(z) that encapsulates relativistic observational perspectives at various epochs.

This opens a new frontier: rederiving H(z) from first principles under a proper-time-based FLRW generalization that includes time dilation as encoded in the metric structure. Such an extension is developed in the following section.

2.3. Toward a Reformulated FLRW Metric under EAoU Principles

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric is a solution to Einstein's field equations under the assumptions of homogeneity, isotropy, and the use of a global comoving coordinate system. In its standard form, it is expressed as shown in equation (8) :

where “t” is the cosmic time, shared equally by all comoving observers. As previously shown, this formulation suppresses relativistic time dilation across cosmological epochs by assuming:

All observers are comoving and experience identical proper time dτ = dt

The temporal metric component g00 = −1 is constant, enforcing uniform clock rates throughout the manifold.

2.3.1. Incorporating Proper-Time Accumulation via EAoU

Under the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) paradigm, we shift the reference frame to the present-day observer, for whom early epochs of the universe unfold under significant gravitational and kinematic time dilation. To accommodate this, we must:

- -

Replace the coordinate time t with the accumulated proper time τ

- -

Recognize that dτ ≠ dt and thus the time part of the metric must carry a time-dilation factor, say f(z), which could vary with redshift or energy density

This yields a generalized form of the metric:

Here:

- -

f(z) ≡ dτ/dt, which under special-relativistic approximation reduces to 1/1+z

- -

f(z) < 1 implies clock slowing in earlier epochs when viewed from today

This modification reflects a non-trivial time component, making g00 = −f(z)2 ≠ −1. The universe is no longer globally synchronized. Proper time is observer-dependent, and this observer-centric foliation of spacetime reflects realistic relativistic aging

2.3.2. Implications for Einstein's Equations and Friedmann Dynamics

Einstein’s field equations (equation 1):

are traditionally solved using a static time component in the metric tensor, with g00 = −1. However, the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) formulation redefines the temporal structure by introducing a proper-time-based coordinate system, replacing cosmic time t with observer-centric proper time τ. This necessitates a reevaluation of the underlying spacetime geometry.

2.3.3. Modified Metric Tensor

Under the EAoU framework, the metric tensor acquires a dynamic time component:

Where,

reflects time dilation relative to the observer’s frame. This modification alters the structure of the Christoffel symbols and Ricci tensor, as ∂g

00 / ∂z ≠ 0, introducing proper-time derivatives into the curvature dynamics.

In the standard FLRW metric, g00 = −1 is constant, so its derivative with respect to redshift vanishes, ∂g00/∂z = 0. This encodes the assumption that cosmic time is homogeneous and universal for all comoving observers. In the EAoU formulation, however, the temporal metric component becomes g00(z)=−f(z)2 with f(z) =1+z, so ∂g00/∂z ≠ 0. Physically, this means that the rate of proper-time flow changes with redshift, introducing an explicit time dilation into the metric. This modification affects the Christoffel symbols, and therefore the Ricci tensor, altering the dynamical evolution equations compared to the standard ΛCDM–FLRW case. The full implications of this redshift-dependent g00 for curvature, geodesic deviation, and cosmic dynamics remain to be explored in greater detail in future work.

2.3.4. Impact on Friedmann Dynamics in Observer-Centric Time

In the standard ΛCDM framework, the Hubble parameter is defined in terms of comoving coordinate time t as:

However, this formulation assumes that t corresponds to the proper time of all comoving observers, which—as discussed—is a restrictive idealization. In a relativistically consistent (EAoU) framework, we must account for the time dilation experienced by a present-day observer relative to earlier epochs. This leads to a transformation between comoving time t and observer time τ, given by:

Using this, the derivative with respect to observer proper time becomes:

Substituting back into the Hubble expression gives the observer-centric Hubble parameter:

2.4. Interpretation and Implications

Observer Time Elongation: Since dτ > dt, a process that involves time period Δt in the comoving frame will appear stretched in the observer's proper time. This time elongation lowers the effective rate of expansion as seen by present-day observers.

Reduced Effective Expansion Rate: The effective Hubble parameter Heff(z) is always smaller than the comoving Hubble rate H(z) for z > 0, reflecting that in the observer frame, expansion appears slower in earlier epochs.

Proper-Time Consistency: The transformation preserves relativistic consistency across the manifold by aligning expansion rates with elapsed proper time, thus embedding EAoU within the Friedmann dynamics.

3. EAoU Application to High-Redshift Anomalies

A core motivation for introducing the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) is to reconcile the mounting observational evidence of mature cosmic structures at extreme redshifts with the limited time available under the conventional Age of the Universe (AoU) framework. Based on the parameters given in

Table 1,

Table 2 presents a side-by-side comparison of AoU and EAoU values at representative redshifts, z = 1 to 20, calculated using both the Planck 2018 and SH0ES Hubble constants. Across all models, EAoU yields significantly extended lookback times compared to AoU, scaling by a relativistic dilation factor of 1 + z. For instance, at z = 10, the standard AoU estimate of ~470 Myr expands to over ~15 Gyr under EAoU (Planck) and nearly ~13.9 Gyr (SH0ES), significantly enhancing the effective time available for structure formation. These expanded temporal windows critically alter the interpretation of early-universe objects and alleviate the need for exotic or fine-tuned formation mechanisms.

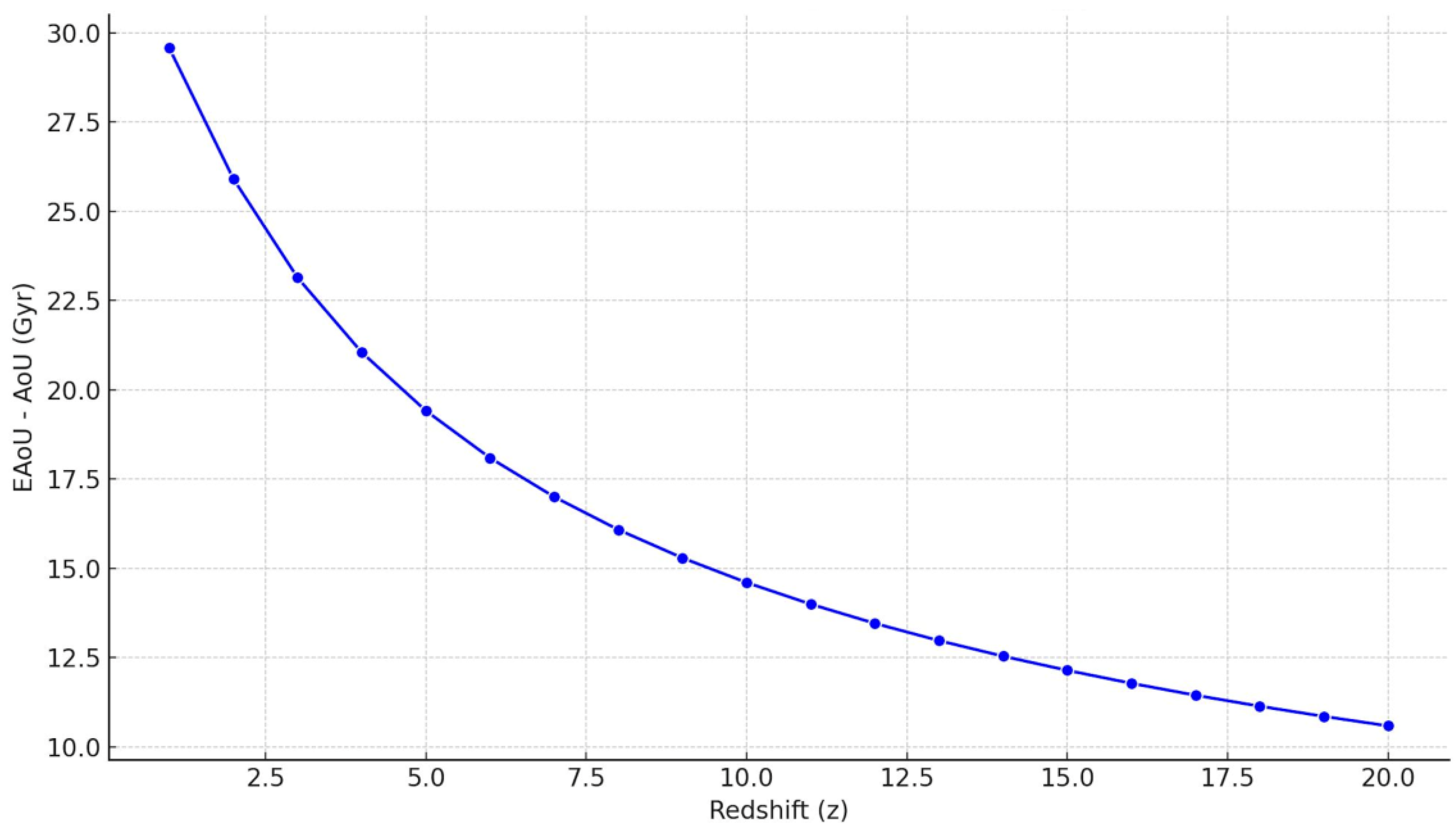

In

Figure 1 we show how EAoU and AoU are related to z under Planck and SHOES scenarios. It can be seen that EAoU provides for an effective age in excess of 45 Gyr. The “EAoU – AoU” plot in

Figure 2 shows significantly more effective time available for structure formation at z = 12.5 to 15.

In the subsections below, we apply the EAoU framework to specific observational anomalies, including ultra-early galaxies, chemically enriched systems, and supermassive black holes — and demonstrate how EAoU resolves timing inconsistencies that otherwise challenge ΛCDM cosmology.

3.1. EAoU Implications on Structure Formation

We re-examine a selection of recently identified cosmic structures to evaluate how their apparent anomalies are resolved under the EAoU framework.

Table 3 summarizes the EAoU-derived parameters for several representative high-redshift objects.

3.1.1. GN-z11: Revisiting Structure Formation at z = 10.6

GN-z11, observed at a redshift of z = 10.6, represents one of the earliest and most luminous galaxies detected near the edge of the current observational reach. Under the standard Age of the Universe (AoU) framework, this redshift corresponds to merely ~440 million years after the Big Bang, an extremely short timespan in which to assemble a galaxy with an estimated stellar mass of ~10⁹ M⊙ and unusually high UV luminosity. Such early and rapid buildup strains ΛCDM expectations, especially under models constrained by feedback-regulated star formation and metallicity evolution.

However, under the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) framework, the available time for evolution is substantially extended. At z = 10.6, EAoU (Planck) assigns an effective time interval of approximately 14.7 Gyr from the Big Bang to the observed epoch, as experienced along the observer’s worldline. This radically alters the interpretation: Formation of GN-z11 is no longer limited to a 440 Myr window, but instead within a 14.7 Gyr evolutionary timescale—a timeline consistent with the gradual buildup of stellar mass at an average SFR of just ~0.07 M⊙/yr. Additionally, the detection of oxygen and nitrogen lines—signatures of previous star-forming generations—is now naturally accommodated within this extended duration.

Thus, what appears under AoU as a galaxy in tension with ΛCDM formation scenarios becomes, in the EAoU view, a typical high-redshift system evolving over a cosmologically reasonable timeframe.

3.1.2. JADES-GS-z14-0: Resolving the Earliest Galaxy Formation

A similar reinterpretation applies to the even earlier system JADES-GS-z14-0, currently among the most distant known galaxies at z ≈ 13.9. Under the standard Age of the Universe (AoU) framework, this redshift corresponds to a mere ~300 million years after the Big Bang, an extremely narrow window for the formation of a luminous galaxy exhibiting detectable rest-frame UV and infrared emission. Semi-analytic models calibrated to Planck cosmology struggle to predict the emergence of such massive systems within this timeframe.

By contrast, the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) recasts this timeline dramatically. At z ≈ 13.9, EAoU assigns an effective time since the Big Bang of ~12.8 Gyr to the galaxy's frame. This extended effective duration allows for sequential processes of gas cooling, gravitational collapse, multiple stellar generations, and substantial chemical enrichment—providing a coherent explanation for the presence of oxygen and nitrogen emission lines observed in such systems. Instead of invoking exotic physics (e.g., enhanced Population III star formation or modified dark matter scenarios), JADES-GS-z14-0 emerges naturally within a universe that appears older from the standpoint of a relativistically consistent observer.

3.1.3. HD1 and Starburst Activity at Cosmic Dawn

HD1, a candidate galaxy at redshift z ≈ 13.3, exhibits an exceptionally high star formation rate, estimated at nearly 100 M⊙/yr, placing it among the most extreme known starburst systems near the cosmic dawn. Under the standard AoU model, this would imply a stellar mass buildup of nearly 109 M⊙ within just ~300 Myr after the Big Bang, a timeline that challenges even the most optimistic cooling, feedback, and merger scenarios within ΛCDM.

Within the EAoU framework, however, the effective time available for HD1’s evolution extends dramatically to over 13.3 Gyr, depending on the adopted H0. This temporal expansion alleviates the need for exceptionally rapid stellar formation and allows for a more gradual, regulated growth process. Star formation can proceed either continuously or episodically over extended intervals, yielding a stellar mass and spectral features consistent with known astrophysical processes. Moreover, this duration provides sufficient time for chemical enrichment, offering a natural explanation for emerging hints of evolved stellar populations. What appears anomalous under AoU becomes entirely plausible within the relativistically consistent EAoU framework.

3.1.4. Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) and Early Growth

The discovery of ULAS J1120+0641, a luminous quasar at z = 7.1 hosting a ∼109 M⊙ supermassive black hole (SMBH), has long posed a major challenge to ΛCDM under the standard Age of the Universe (AoU) formulation, which offers only ~760 million years for black hole seed formation and growth. Achieving such a massive SMBH within this limited window typically requires sustained Eddington or even super-Eddington accretion — conditions often regarded as implausible due to radiative feedback and hierarchical growth constraints.

Under the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) framework, however, the timeline for SMBH growth is dramatically extended. At z = 7.1, EAoU yields an effective time since the Big Bang of approximately 17.77 Gyr (Planck) or 16.40 Gyr (SH0ES), many times longer than the AoU estimate. This generous growth window makes Eddington-limited accretion scenarios, with moderate duty cycles and no need for exotic seeds, fully viable within the standard ΛCDM framework.

Semi-analytic models support such outcomes under extended timelines[

49,

50]. As JWST continues to reveal quasars at even higher redshifts, EAoU provides a consistent relativistic framework for interpreting their rapid emergence, without requiring modifications to the underlying physics of cosmic structure formation.

3.2. EAoU and Entropy

The Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) not only addresses timing discrepancies at high redshift but also prompts a reevaluation of the universe’s thermodynamic evolution. By redefining cosmic time from the perspective of a present-day observer, EAoU introduces a temporal framework in which early epochs appear significantly lengthened. This extended perspective has direct implications for the pace at which entropy-producing processes unfolded in the early universe.

In particular, EAoU links cosmic entropy evolution to the relativistic slowdown of physical processes at high redshift. Since the characteristic speeds, v(z) of non-relativistic processes scale as:

the rates of entropy-generating mechanisms—such as stellar fusion, accretion flows, and dissipative shock heating—are correspondingly reduced when viewed from the observer’s proper-time frame. This slower effective pace means that, even in the high-density conditions of the early universe, thermodynamic complexity would accumulate more gradually than is implied by the comoving-frame view. Consequently, the extended EAoU timeline not only accommodates the early appearance of massive structures but also renders their chemical and entropic maturity a natural outcome of prolonged, moderated energy dissipation.

In the conventional Age of the Universe (AoU) frame, early galaxies such as JADES-GS-z14-0 (z ≈ 13.9) and HD1 (z ≈ 13.3) seemed to form within just ~300 Myr after the Big Bang. However, in the EAoU framework, these same galaxies are situated at ~12.8–13.3 Gyr on the effective-time axis—implying a vastly longer effective duration since the Big Bang. Similarly, GN-z11 at z ≈ 10.6, which under AoU formed within ~440 Myr, now effectively emerges at ~14.7 Gyr in EAoU. The quasar ULAS J1120+0641 at z = 7.1, typically interpreted as forming within ~760 Myr, is now situated at ~17.8 Gyr under EAoU (Planck).

These extended durations imply that entropy generation—via star formation, black hole accretion, and chemical enrichment—occurred over cosmologically reasonable timescales rather than being compressed into narrow bursts. This alleviates the need for exotic feedback processes, extreme accretion rates, or unusually rapid chemical enrichment, all of which are typically invoked in the AoU framework. Entropy production in EAoU is thus more gradual, smoothing the buildup of complexity and moderating early starburst episodes.

Rather than conflicting with thermodynamic principles, EAoU reframes them within a relativistically consistent context aligned with the observer's proper time. This reinterpretation of early entropy buildup complements EAoU’s ability to ease the Hubble tension, offering a unified framework where both the timing and thermodynamic consequences of structure formation emerge as natural, internally consistent outcomes.

3.3. EAoU and the Hubble Tension

The implications of EAoU extend directly to one of the most persistent puzzles in contemporary cosmology: the discrepancy between the Hubble constant (H₀) inferred from early-universe observations (e.g., Planck CMB data) and late-universe measurements (e.g., SH0ES Cepheid calibrations). This “Hubble tension,” amounting to a ~ 5 – 6 km/ s/ Mpc difference, has remained a major challenge to the internal consistency of ΛCDM.

EAoU reframes this problem by replacing the conventional comoving-time metric with a proper-time formulation rooted in the worldline of a present-day observer. In standard cosmology, early epochs appear 'contracted' due to the (1+z)⁻¹ scaling embedded in the cosmic age integral—effectively shrinking the perceived time available for early cosmic evolution. EAoU eliminates this apparent compression by discarding the (1+z)⁻¹ factor, instead integrating over the full relativistic proper time.

This leads to a stretched, observer-centric timeline in which early and late epochs are both extended consistently. As a result, the expansion history is interpreted over a longer temporal baseline, meaning the required Hubble expansion rate (H₀) to achieve the present-day scale factor, logically speaking, should be correspondingly lower. Both Planck- and SH0ES-derived values of H₀ are therefore expected to shift downward under EAoU framework, narrowing the gap and potentially reconciling the two measurements within a unified relativistic framework—without invoking new physics.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a fundamental reinterpretation of cosmic chronology through the introduction of the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU)—a proper-time-based framework that redefines the temporal structure of cosmology from the perspective of a present-day observer. By replacing the conventional comoving coordinate time with the accumulated proper time along the observer’s worldline, EAoU restores relativistic consistency to the FLRW–ΛCDM model without altering its core physical assumptions.

The reformulation yields multiple profound consequences. First, it resolves longstanding high-redshift anomalies by dramatically extending the effective time available for early structure formation. Galaxies such as GN-z11, HD1, and JADES-GS-z14-0, which appear anomalously evolved within the conventional age window of ~300–500 Myr, are shown to have evolved over extended timescales exceeding 13–15 Gyr in observer time. Similarly, the formation of ~10⁹ M☉ supermassive black holes becomes plausible under prolonged accretion histories within the EAoU framework.

Second, by modifying the temporal component of the FLRW metric to account for time dilation (via a non-static g

00 = -f(z)

2) EAoU leads to a redshift-dependent redefinition of the expansion rate:

This observer-centric Hubble parameter reflects the slower effective expansion measured in proper time and mitigates the stronger early-epoch contraction of spatial intervals predicted by standard ΛCDM, as the EAoU framework incorporates relativistic time-dilation effects. The net implication is a universe that is older in age, but effectively smaller in spatial scale—a coherent consequence of relativistic interpretation.

Moreover, EAoU reframes the Hubble tension by implying a symmetric downward revision in the inferred value of H0 from both early- and late-universe observations. The extended effective timeline reduces the required expansion rate to reach the present scale factor, thus narrowing the discrepancy between Planck and SH0ES datasets without invoking new physics.

Finally, this temporal reconceptualization has thermodynamic implications. The gradual stretching of early epochs under EAoU leads to a more natural, less fine-tuned buildup of entropy, allowing standard processes like stellar evolution, accretion, and chemical enrichment to occur within reasonable timescales.

In summary, the EAoU framework preserves the core structure of general relativity and ΛCDM, while providing a more faithful mapping between cosmic history and observation. It resolves multiple observational tensions, enriches the conceptual architecture of cosmology, and offers a fertile ground for reinterpreting distance measures, growth functions, and cosmological parameters through the lens of proper time. As cosmology advances into a precision era, EAoU provides a compelling step toward a more coherent and relativistically complete universe.

References

- Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., et al. (1998). "Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant." The Astronomical Journal, 116(3), 1009-1038. [CrossRef]

- Nature Astronomy. (2023). Early results on the early Universe. Nature Astronomy, 7, 505. [CrossRef]

- Oesch, P. A. et al. “A Remarkably Luminous Galaxy at z = 11.1 Measured with Hubble Space Telescope Grism Spectroscopy.” The Astrophysical Journal 819, 129 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bunker et al. “ JADES NIRSpec Spectroscopy of GN-z11: Lyman-α emission and possible enhanced nitrogen abundance in a z = 10.60 luminous galaxy.” Astronomy & Astrophysics, A&A Volume 677, September 2023;

- Harikane, Y. et al. “HD1 and HD2: Two Bright z ≈ 13 Galaxy Candidates Discovered in the Early Universe.” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 519, L1–L7 (2023). [Note: Check exact volume/page]. [CrossRef]

- Harikane, Y., Ouchi, M., Oguri, M., et al. (2022). A Comprehensive Study of Galaxies at z ~ 10–14 Revealed by the James Webb Space Telescope Early Release Observations. The Astrophysical Journal, 929(1). [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R. P. et al. “GLASS-z13 and z14: JWST Spectroscopic Confirmation of the Most Distant Galaxies to Date.” Nature Astronomy 6, 123–131 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R Naidu et al. “A Cosmic Miracle: A Remarkably Luminous Galaxy at zspec=14.44 Confirmed with JWST,” arXiv:2505.11263 [astro-ph.GA].

- Robertson, B.E., Tacchella, S., Johnson, B.D. et al. Identification and properties of intense star-forming galaxies at redshifts z > 10. Nat Astron 7, 611–621 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Schouws, S. et al. “Detection of [O III] 88 μm in JADES-GS-z14-0 at z = 14.1793.” arXiv:2409.20549 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bouwens, R. J. et al. “The Bright End of the z ≈ 9–10 UV Luminosity Functions Using All Five CANDELS Fields.” The Astrophysical Journal 830, 67 (2016). [CrossRef]

- N J Adams, C J Conselice, L Ferreira, D Austin, J A A Trussler, I Juodžbalis, S M Wilkins, J Caruana, P Dayal, A Verma, A P Vijayan, Discovery and properties of ultra-high redshift galaxies (9 < z < 12) in the JWST ERO SMACS 0723 Field, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 518, Issue 3, January 2023, Pages 4755–4766, . [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty et al., “ Detection of New Galaxy Candidates at z > 11 in the JADES Field Using JWST NIRCam,” . [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. J. et al. “Nitrogen Enhancements 440 Myr after the Big Bang: Super-Solar N/O in GN-z11.” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 523, 3516–3525 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bouwens, R. J. et al. “The Bright End of the z ≈ 9–10 UV Luminosity Functions Using All Five CANDELS Fields.” The Astrophysical Journal 830, 67 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R. P. et al. “The Emergence of the First Massive Galaxy Archaeological Fossils.” Nature Astronomy 7, 611–621 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Labbe, I. et al. “Discovery of Very Massive Galaxies in the First 500 Myr of Cosmic Time with JWST.” The Astrophysical Journal Letters 936, L16 (2022). [CrossRef]

- ang, X. et al. “Quasars at z > 7 Host Supermassive Black Holes Exceeding 10⁹ M⊙.” The Astrophysical Journal 907, 61 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Inayoshi, K., Visbal, E., & Haiman, Z. “The Assembly of the First Massive Black Holes.” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 58, 27–97 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Natarajan et al. ,” First Detection of an Overmassive Black Hole Galaxy UHZ1: Evidence for Heavy Black Hole Seed Formation from Direct Collapse,” 2024 ApJ...960L...1N. [CrossRef]

- Mortlock et al. (2011); A luminous quasar at a redshift of z = 7.085, Nature, 474, 616–619.DOI: 10.1038/nature10159.

- Bañados et al. (2018); An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5, Nature, 553, 473–476.; DOI: 10.1038/nature25180.

- Wang et al. (2021) A Luminous Quasar at Redshift 7.642 The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 907:L1.; DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/abd8c6.

- Pacucci, F. et al. “Are the Newly-Discovered z ≈ 13 Drop-out Sources Starburst Galaxies or Quasars?” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters 514, L1–L5 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G. et al. “Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for Determining the Hubble Constant … Physics beyond ΛCDM.” The Astrophysical Journal 876, 85 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shengdong Lu, Carlos S Frenk, Sownak Bose, Cedric G Lacey, Shaun Cole, Carlton M Baugh, John C Helly, A comparison of pre-existing ΛCDM predictions with the abundance of JWST galaxies at high redshift, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 536, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 1018–1034, . [CrossRef]

- Fulvio Melia, The cosmic timeline implied by the JWST high-redshift galaxies, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, Volume 521, Issue 1, May 2023, Pages L85–L89, . [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration VI. “Planck 2018 Results. VI. Cosmological Parameters.” Astronomy & Astrophysics 641, A6 (2020). [CrossRef]

-

[1] Bouwens, R. J. et al. “UV Luminosity Functions at z > 10 from HST and JWST Data.” The Astrophysical Journal 907, 91 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Boylan-Kolchin, M. “Steep Faint-end Slopes in the z > 10 UV Luminosity Functions: A Challenge for ΛCDM.” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 482, L49–L53 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Arrabal Haro, P., Dickinson, M., Finkelstein, S.L. et al. Confirmation and refutation of very luminous galaxies in the early Universe. Nature 622, 707–711 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bruno M. B. Henriques, Simon D. M. White, Peter A. Thomas, Raul Angulo, Qi Guo, Gerard Lemson, Volker Springel, Roderik Overzier, Galaxy formation in the Planck cosmology – I. Matching the observed evolution of star formation rates, colours and stellar masses, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 451, Issue 3, 11 August 2015, Pages 2663–2680 . [CrossRef]

- Hossain, J. Effective Age of the Universe: Application of Relativistic Time Dilation. Preprint at ResearchGate (2025). DOI: https//doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25271.43688.

- 3K: The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, by R. B. Partridge, pp. 393. ISBN 0521352541. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, September 1995.

- Riess, A. G., Anand, G. S., Yuan, W., Macri, L. M., Casertano, S., Dolphin, A., Breuval, L., Scolnic, D., Perrin, M., & Anderson, R. I. (2024). JWST Observations Reject Unrecognized Crowding of Cepheid Photometry as an Explanation for the Hubble Tension at 8 sigma Confidence. ArXiv. /abs/2401.04773.

- Planck 2018 results - I. Overview and the cosmological legacy of Planck, Planck Collaboration, N. Aghanim, et. al, A&A 641 A1 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G., Anand, G. S., Yuan, W., Casertano, S., Dolphin, A., Macri, L. M., Breuval, L., Scolnic, D., Perrin, M., & Anderson, R. I. (2023). Crowded No More: The Accuracy of the Hubble Constant Tested with High-Resolution Observations of Cepheids by JWST. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, published October 1, 2023; arXiv:2307.15806.

- Riess, A. G., Casertano, S., Yuan, W., Macri, L. M., & Scolnic, D., Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant and Stronger Evidence for Physics Beyond LambdaCDM. 2019, ApJ, 876, 85, arXiv:1903.07603.

- Riess, A.G., Casertano, S., Yuan, W., Bradley Bowers, J., Macri, L., Zinn, J.C., et al . (2021) Cosmic Distances Calibrated to 1% Precision with Gaia Edr3 Parallaxes and Hubble Space Telescope Photometry of 75 Milky Way Cepheids Confirm Tension with ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal Letters , 908, Article ID: L6. [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G., et al. (2022). " A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km/s/Mpc Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team”, arXiv:2112.04510v3 [astro-ph.CO].

- Peebles, PJE, “Standard Cosmological Model,” In Les Rencontres de Physique de la Vallee d’Aaosta (1998) ed. M. Greco, Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University (accessed on December 22, 2024).

- Weinberg, S. (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471925675.

- Planck Collaboration. (2020). "Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters." Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

- Barbara Ryden, Introduction to Cosmology (2nd ed., 2017), Cambridge University Press — Section 5.4 ("Lookback Time and Age of the Universe"). ISBN: 978-1107154834.

- Carroll, S. M. (2004/2019). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108488396.

- Goldhaber et al. (2001), "Timescale stretch parameterization of type Ia supernova B-band light curves," The Astrophysical Journal, 558, pp. 359–368.

- Hossain, J. (2025). Relativistic Reformulation within the FLRW–ΛCDM Framework. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Freedman, W. L., & Madore, B. F. "The Hubble Constant." Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 57, 335–375 (2019). — a comprehensive review of all major methods, including SNe Ia, CMB, and BAO . [CrossRef]

- Rosa Valiante, Raffaella Schneider, Marta Volonteri, Kazuyuki Omukai, From the first stars to the first black holes, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 457, Issue 3, 11 April 2016, Pages 3356–3371, . [CrossRef]

- Majda Smole, Miroslav Micic, Nemanja Martinović, SMBH growth parameters in the early Universe of Millennium and Millennium-II simulations, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 451, Issue 2, 01 August 2015, Pages 1964–1972, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).