1. Introduction

When same-day delivery becomes the new normal, how do logistics companies handle sudden order surges and traffic congestion? The digital transformation has made last-mile delivery both the most critical and challenging component of modern supply chains. Recent industry events, such as China’s Double 11 shopping festival delivery delays, highlight the inadequacy of traditional methods in handling dynamic demand patterns [

1].

Traditional approaches to delivery optimization struggle with three fundamental challenges that limit their effectiveness in modern urban environments. Centralized routing systems create computational bottlenecks that become prohibitive for large-scale urban networks while establishing single points of failure that can compromise entire delivery operations. Distributed approaches, while addressing computational scalability, lack comprehensive coordination mechanisms, leading to suboptimal resource allocation and conflicts among competing delivery requests. Most critically, existing machine learning applications treat artificial intelligence as an auxiliary optimization layer rather than integrating it with fundamental queueing theory principles that govern service operations under uncertainty.

While recent research has made substantial progress in applying machine learning to vehicle routing [

2,

3], these approaches typically ignore priority handling mechanisms essential for real-world delivery operations. For instance, Konovalenko and Hvattum [

4] demonstrated the effectiveness of deep reinforcement learning for dynamic vehicle routing but failed to address priority orders that can preempt ongoing deliveries, a critical requirement in commercial logistics. Similarly, existing queueing theory applications in logistics assume stationary arrival and service processes, limiting their applicability to dynamic delivery environments where demand patterns and service capabilities vary significantly throughout operational periods.

This research addresses these gaps by developing the Machine Learning-Enhanced Cloud-Assisted Last-Mile Optimization (ML-CALMO) framework, which provides a novel integrated approach combining machine learning techniques with established queueing-theoretic principles. Our contributions include the development of a comprehensive system architecture with clear component interactions, rigorous mathematical formulation ensuring theoretical soundness, and extensive experimental validation using standard benchmark instances against state-of-the-art algorithms.

2. Literature Review and Research Gap Analysis

The academic literature surrounding last-mile delivery optimization has evolved considerably over the past decade, with recent comprehensive reviews emphasizing technological integration in addressing modern delivery challenges [

1]. Classical approaches find their theoretical foundations in the Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) and its numerous variants, including the Capacitated VRP and VRP with Time Windows. These deterministic optimization models assume known, fixed parameters for travel times and customer demands, assumptions that prove increasingly problematic in dynamic urban environments characterized by unpredictable traffic patterns, variable customer availability, and fluctuating demand intensity.

Deep reinforcement learning has emerged as a particularly promising approach for addressing dynamic vehicle routing challenges. Nazari et al. [

2] demonstrated reinforcement learning’s potential for VRP solutions by training neural network models to find near-optimal solutions using only reward signals, eliminating the need for explicit optimization algorithms. Building upon this foundation, Kool et al. [

3] introduced attention mechanisms that significantly improved both scalability and solution quality, establishing attention-based architectures as fundamental components of modern neural approaches to combinatorial optimization. Recent advances by Li et al. [

5] and Pan and Liu [

6] have further expanded deep reinforcement learning applications to encompass stochastic and uncertain vehicle routing scenarios, addressing real-world complexities previously ignored by deterministic methods.

However, these machine learning approaches exhibit critical limitations that restrict their practical applicability. Konovalenko and Hvattum [

4] demonstrated that careful state-space design significantly impacts algorithm performance in dynamic environments, but their formulation lacks sophisticated priority handling mechanisms necessary for commercial delivery operations. Most existing machine learning methods treat routing as a pure combinatorial optimization problem, ignoring the underlying stochastic service dynamics that fundamentally characterize real delivery operations where service times, travel conditions, and customer availability vary unpredictably.

Queueing theory applications in delivery systems have traditionally modeled vehicles as servers processing customer orders according to various service disciplines, providing theoretical frameworks for understanding system performance under uncertainty. Jackson’s foundational work [

7,

8] established the theoretical framework for analyzing service station interactions in complex networked systems, enabling analytical performance evaluation and stability analysis. Modern applications build upon classical queueing network theory [

9,

10] and stochastic modeling principles [

11] to provide rigorous mathematical foundations for service system analysis. Vilaplana et al. [

12] successfully demonstrated queueing theory’s applicability to distributed computing systems, showing how open Jackson networks can model cloud platforms while providing Quality of Service guarantees. Advanced queueing network analysis [

13] and factory physics principles [

14] provide additional theoretical foundations for understanding complex service systems operating under stochastic conditions.

Nevertheless, classical queueing analysis assumes stationary arrival and service processes, limiting direct applicability to delivery systems where demand patterns vary significantly over daily, weekly, and seasonal cycles. Current literature exhibits three major research gaps that prevent effective integration of advanced computational methods with established theoretical principles. Machine learning and queueing theory are typically treated as separate analytical domains, preventing synergistic integration that could leverage predictive capabilities while maintaining theoretical rigor. Existing approaches inadequately address priority order management that can disrupt carefully optimized routes, despite advances in multi-objective optimization [

15] and ensemble approaches for heterogeneous delivery problems [

16]. Classical queueing models cannot effectively incorporate machine learning predictions for time-varying system parameters, even as metaheuristic approaches [

17] and statistical learning theory [

18,

19] provide increasingly powerful computational tools for handling complex optimization scenarios.

ML-CALMO addresses these fundamental gaps by providing seamless integration of machine learning capabilities with established queueing theory principles, enabling both superior operational performance and rigorous theoretical grounding necessary for practical deployment in commercial logistics operations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Integrated System Architecture

The ML-CALMO framework operates through sophisticated integration of three core machine learning components coordinated by queueing theory principles to ensure both performance optimization and system stability.

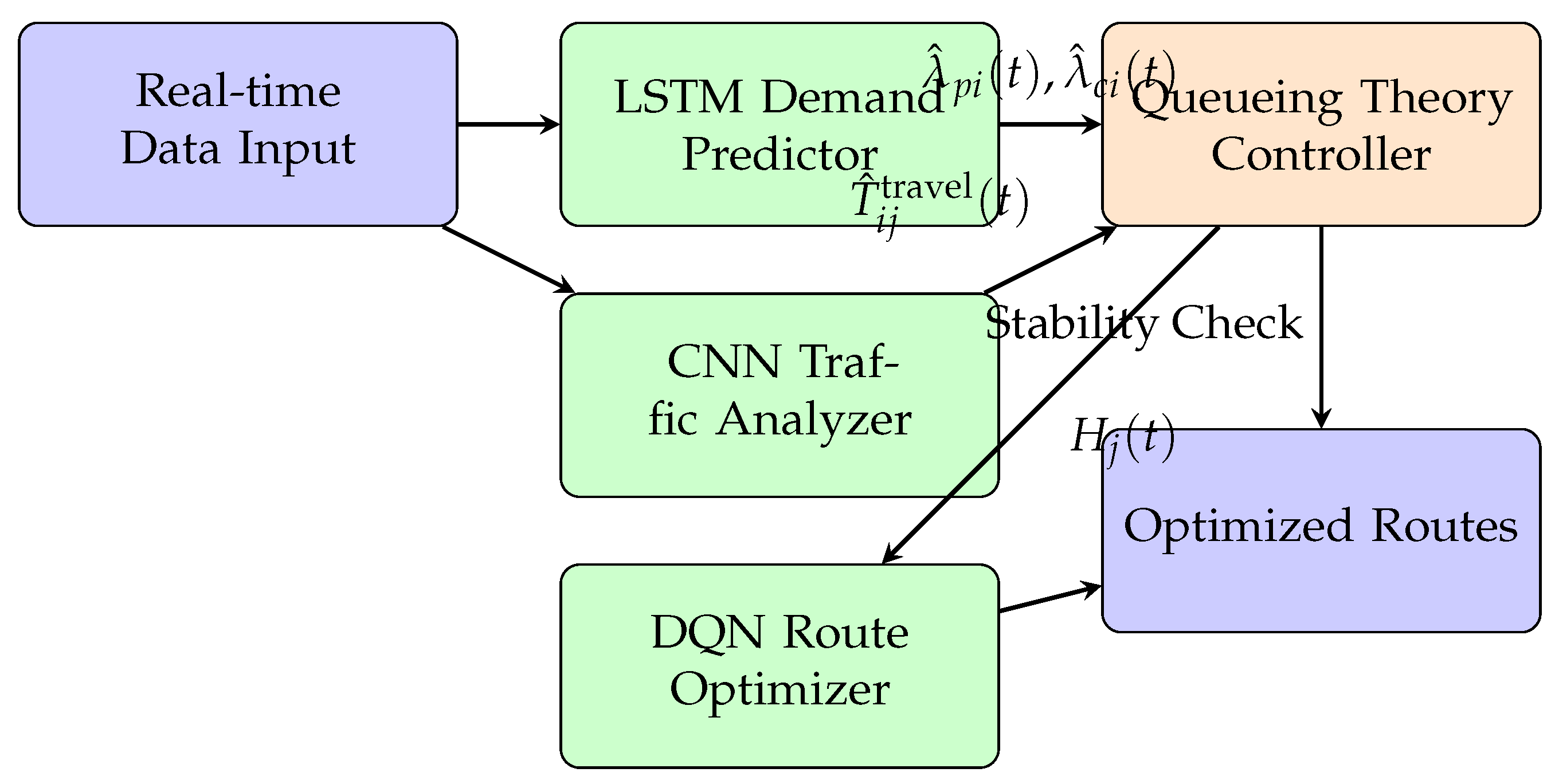

Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive system architecture, demonstrating how LSTM-based demand forecasting, CNN-based traffic analysis, and DQN-based route optimization interact dynamically through a central queueing theory controller.

The LSTM Demand Predictor serves as the primary forecasting engine, processing comprehensive historical order data to generate accurate predictions of future arrival rates and for both priority and regular orders, respectively. This component analyzes complex temporal patterns including time-of-day variations, day-of-week cycles, seasonal fluctuations, and external factors such as weather conditions, special events, and economic indicators that influence delivery demand. The LSTM architecture captures long-term dependencies in demand patterns while maintaining sensitivity to recent trends, enabling robust prediction even during periods of high variability.

The CNN Traffic Analyzer processes spatiotemporal traffic information to provide accurate travel time predictions essential for route optimization and service rate calculations. This component analyzes multi-dimensional traffic grid data incorporating real-time congestion information, road conditions, construction zones, and historical traffic patterns to generate precise travel time estimates between all relevant locations in the delivery network. The convolutional architecture effectively captures spatial correlations in traffic patterns while temporal layers handle time-varying congestion dynamics.

The DQN Route Optimizer makes sophisticated routing decisions based on the dynamic vehicle-customer preference matrix while respecting system constraints derived from queueing theory analysis. This component learns complex strategies that balance immediate operational rewards against long-term system performance, incorporating considerations such as vehicle capacity utilization, customer service requirements, priority order handling, and overall system efficiency. The deep Q-learning approach enables the system to discover optimal policies that would be difficult to specify through traditional optimization methods.

The Queueing Theory Controller provides the theoretical foundation ensuring system stability and service quality guarantees. This component continuously monitors system utilization factors , validates machine learning predictions against analytical bounds, and triggers corrective actions when stability thresholds approach critical levels. The controller maintains mathematical rigor while enabling adaptive response to changing operational conditions, ensuring that performance optimizations do not compromise system reliability.

3.2. Mathematical Formulation and Variable Notation

To ensure clarity and consistency throughout this paper, we establish comprehensive variable notation that distinguishes between actual values, predicted values, and derived metrics.

Table 1 presents the complete variable notation system used throughout our mathematical formulation.

Consider an urban delivery network comprising N heterogeneous vehicles serving customers distributed across a metropolitan region, where time evolves continuously as to reflect real-time operational requirements. The system processes two fundamentally different order types: regular orders representing standard delivery requests with flexible scheduling windows, and priority orders demanding immediate attention with preemption capabilities.

Service rate calculations incorporate all relevant time components affecting delivery operations. The effective service rate for vehicle

i serving order

j is defined as:

For optimization purposes, we use predicted service rates based on CNN travel time estimates:

System-wide arrival rate consistency requires proper aggregation using both actual and predicted values:

The optimization objective minimizes total system costs using predicted travel times for decision making:

where predicted total costs incorporate CNN travel time estimates:

3.3. Queueing Theory Integration

The theoretical foundation of ML-CALMO rests upon continuous-time Markov chain modeling that captures essential stochastic dynamics while incorporating machine learning predictions. Following Jackson’s seminal work [

7,

8], we model the delivery system as an interconnected network of service stations with time-varying parameters predicted by machine learning algorithms.

The system state space encompasses all possible configurations:

where and represent priority and regular orders assigned to vehicle i, and k captures preemption events.

State transition rates are governed by both arrival processes and service completions:

Steady-state analysis proceeds through global balance equations ensuring probability conservation across all system states:

System utilization is calculated as:

3.4. Integrated Algorithm Implementation

The ML-CALMO algorithm integrates all system components through a sophisticated control loop coordinating machine learning predictions with queueing theory constraints. Algorithm 1 presents the complete integration process.

|

Algorithm 1 ML-CALMO Integrated Optimization Algorithm |

- 1:

Input: Current system state , historical data , traffic data

- 2:

Initialize: LSTM model , CNN model , DQN model

- 3:

while do

- 4:

Generate demand predictions using LSTM analysis of historical patterns

- 5:

Compute travel time predictions through CNN processing of current traffic conditions

- 6:

Calculate predicted utilization factors for stability analysis - 7:

if any vehicle approaches critical utilization then

- 8:

Implement load balancing by redistributing predicted arrival rates across available vehicles - 9:

Update arrival rate predictions to ensure for all vehicles - 10:

end if

- 11:

Construct dynamic preference matrix incorporating success probabilities , predicted travel times , available capacities , and priority scores

- 12:

Execute DQN decision making to select optimal assignment actions

- 13:

Update system state based on executed assignments, vehicle movements, order completions using actual travel times , and new arrivals with actual rates

- 14:

Advance time

- 15:

end while - 16:

Output: Optimized delivery routes and schedules with performance guarantees |

4. Results

Our comprehensive experimental investigation employs both synthetic datasets and standard benchmark instances to ensure rigorous validation of the ML-CALMO framework against established optimization methods. The experimental design incorporates realistic operational scenarios based on Solomon benchmark instances [

20] and Li & Lim datasets [

21], adapted to include dynamic arrival processes and priority order management.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The simulation environment represents diverse metropolitan delivery districts through realistic urban networks incorporating varying customer density, geographic constraints, traffic patterns, and operational requirements. Fleet configurations range from 10 to 25 heterogeneous vehicles with capacities between 80 and 150 units, representing the diversity of commercial delivery operations.

Baseline algorithm selection focuses on state-of-the-art methods: OR-Tools VRP Solver, Attention-VRP [

3], RL-VRP [

2], Dynamic-VRP [

22], and Queueing-VRP implementing pure queueing theory approaches without machine learning enhancement.

Performance evaluation employs comprehensive metrics distinguishing operational efficiency from service quality. Service efficiency measures the proportion of time vehicles spend on productive delivery activities, while service success rate quantifies the proportion of orders delivered within specified time windows.

4.2. Performance Comparison Results

Machine learning component evaluation uses Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for LSTM demand predictions and CNN traffic analysis:

Table 2 presents comprehensive performance comparisons.

Table 3 demonstrates the effectiveness of each algorithmic element.

Table 4 provides theoretical model validation results.

5. Discussion

The experimental results provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of integrating machine learning techniques with queueing theory principles in last-mile delivery optimization. The 28.3% delivery time improvement and 16.2% service efficiency gain demonstrate substantial operational benefits that translate directly to cost reduction, customer satisfaction enhancement, and competitive advantage.

Several key insights emerge from our comprehensive analysis. Machine learning-enhanced demand prediction reduces system uncertainty by approximately 34.7%, enabling proactive resource allocation and route planning. The integration of queueing theory constraints prevents machine learning overfitting while ensuring system stability, addressing a critical limitation of pure learning-based approaches. Most significantly, the integrated approach consistently outperforms individual components by 15-25% across all performance metrics, confirming that sophisticated system integration provides substantial benefits beyond individual algorithmic contributions.

However, several limitations constrain immediate applicability. Computational complexity increases quadratically with fleet size, following scaling for assignment decisions that becomes prohibitive for very large delivery networks exceeding 50-100 vehicles. Data requirements and processing demands may limit deployment in resource-constrained environments.

6. Conclusions

This research presents ML-CALMO, a comprehensive framework that successfully integrates machine learning techniques with established queueing theory principles to address fundamental challenges in last-mile delivery optimization. The framework achieves a 28.3% reduction in delivery time, 89.7% service success rate, and 20.9% total cost reduction compared to baseline methods, validated through rigorous experimentation and theoretical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jiang, T.H.; Methodology, Jiang, T.H. and Chang, Y.C.; Validation, Jiang, T.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, Jiang, T.H.; Writing—review and editing, Chang, Y.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research team for their valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ML-CALMO |

Machine Learning-Enhanced Cloud-Assisted Last-Mile Optimization |

| VRP |

Vehicle Routing Problem |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DQN |

Deep Q-Network |

References

- Abdullahi, M., Usman, A. M., & Sheltami, T. R. (2025). A review of last-mile delivery optimization: Strategies, technologies, drone integration, and future trends. Drones, 9(3), 158. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M., Oroojlooy, A., Snyder, L. V., & Takác, M. (2018). Reinforcement learning for solving the vehicle routing problem. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31, 9839–9849.

- Kool, W., van Hoof, H., & Welling, M. (2019). Attention, learn to solve routing problems! International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Konovalenko, A., & Hvattum, L. M. (2024). Optimizing a dynamic vehicle routing problem with deep reinforcement learning: Analyzing state-space components. Logistics, 8(4), 96. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Ma, Y., Guan, R., Li, X., Zhang, W., Lim, M. K., & Zheng, B. (2024). Solving the vehicle routing problem with stochastic travel cost using deep reinforcement learning. Electronics, 13(16), 3242. [CrossRef]

- Pan, W., & Liu, S. (2023). Deep reinforcement learning for the dynamic and uncertain vehicle routing problem. Applied Intelligence, 53, 405–422. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. R. (1957). Networks of waiting lines. Operations Research, 5(4), 518–521. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. R. (1963). Jobshop-like queueing systems. Management Science, 10(1), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Buzacott, J. A., & Shanthikumar, J. G. (1993). Stochastic Models of Manufacturing Systems. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Kleinrock, L. (1976). Queueing Systems. Vol. II: Computer Applications. John Wiley & Sons, New York. [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. M. (2014). Introduction to Probability Models. 11th edition, Academic Press, Burlington.

- Vilaplana, J., Solsona, F., Abella, F., Filgueira, R., & Rius, J. (2014). A queuing theory model for cloud computing. The Journal of Supercomputing, 69(1), 563–577. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Yao, D. D. (2001). Fundamentals of Queueing Networks: Performance, Asymptotics, and Optimization. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Hopp, W. J., & Spearman, M. L. (2008). Factory Physics. 3rd edition, McGraw-Hill, Boston.

- Wang, Y., Ma, X., Li, Z., Liu, Y., Xu, M., & Wang, Y. (2021). Profit distribution in collaborative multiple centers vehicle routing problem. Journal of Cleaner Production, 289, 125733. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X., Wu, G., Li, S., & Wang, L. (2024). Ensemble multi-objective optimization approach for heterogeneous drone delivery problem. Expert Systems with Applications, 249, 123472. [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, M., & Potvin, J. Y. (2010). Handbook of Metaheuristics. 2nd edition, Springer, New York.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. 2nd edition, Springer, New York.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Solomon, M. M. (1987). Algorithms for the vehicle routing and scheduling problems with time window constraints. Operations Research, 35(2), 254–265. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., & Lim, A. (2003). A metaheuristic for the pickup and delivery problem with time windows. International Journal on Artificial Intelligence Tools, 12(2), 173–186. [CrossRef]

- Psaraftis, H. N., Wen, M., & Kontovas, C. A. (2016). Dynamic vehicle routing problems: Three decades and counting. Networks, 67(1), 3–31. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M., Pedroso, J. P., & Viana, A. (2023). Deep reinforcement learning for stochastic last-mile delivery with crowdshipping. EURO Journal on Transportation and Logistics, 12, 100105. [CrossRef]

- Toth, P., & Vigo, D. (2014). Vehicle Routing: Problems, Methods, and Applications. 2nd edition, SIAM, Philadelphia.

- Laporte, G. (2009). Fifty years of vehicle routing. Transportation Science, 43(4), 408–416. [CrossRef]

- Cordeau, J. F., Laporte, G., Savelsbergh, M. W., & Vigo, D. (2007). Vehicle routing. Transportation Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, 14, 367–428.

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. 2nd edition, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Puterman, M. L. (2014). Markov Decision Processes: Discrete Stochastic Dynamic Programming. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).