Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

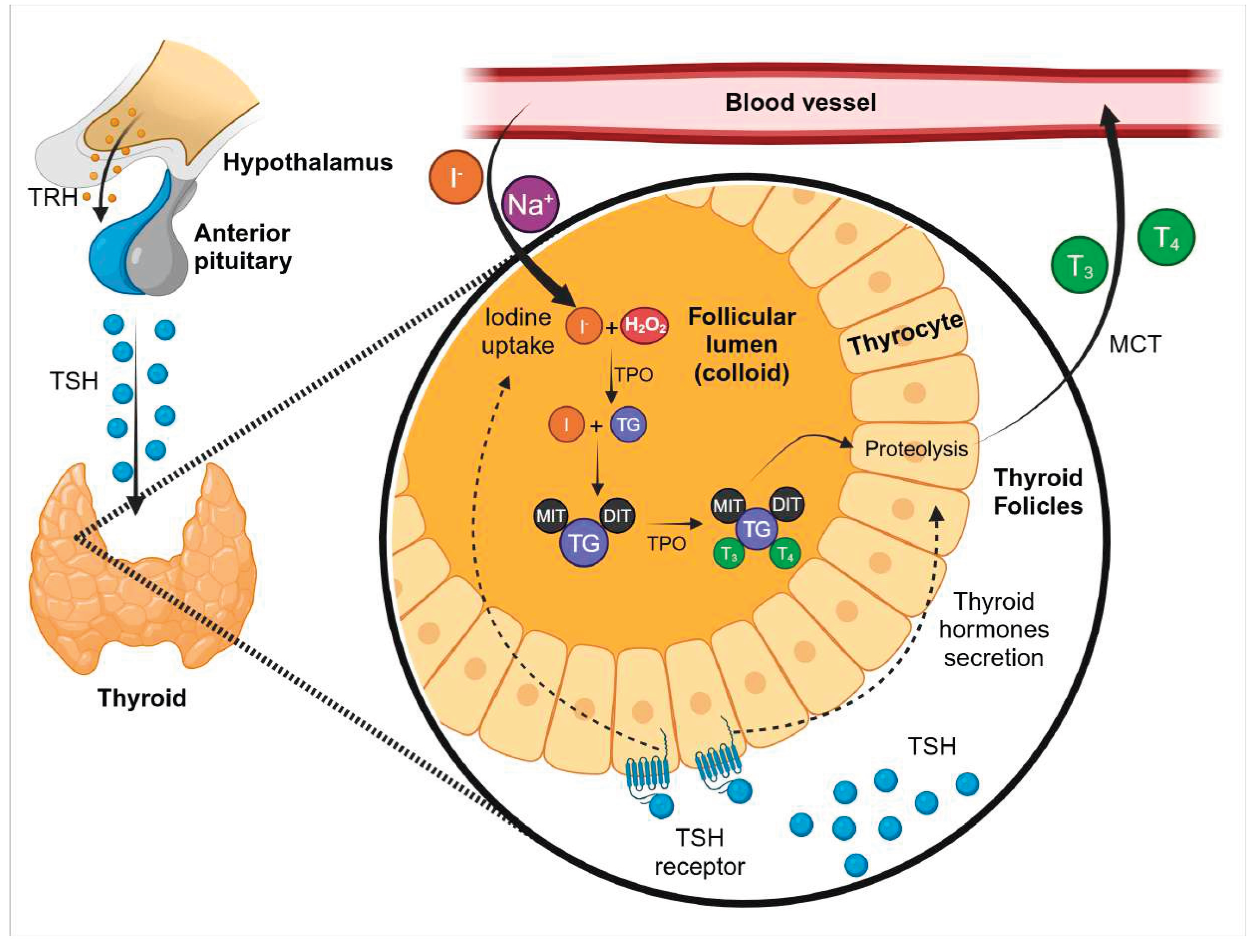

Thyroid Hormones Synthesis

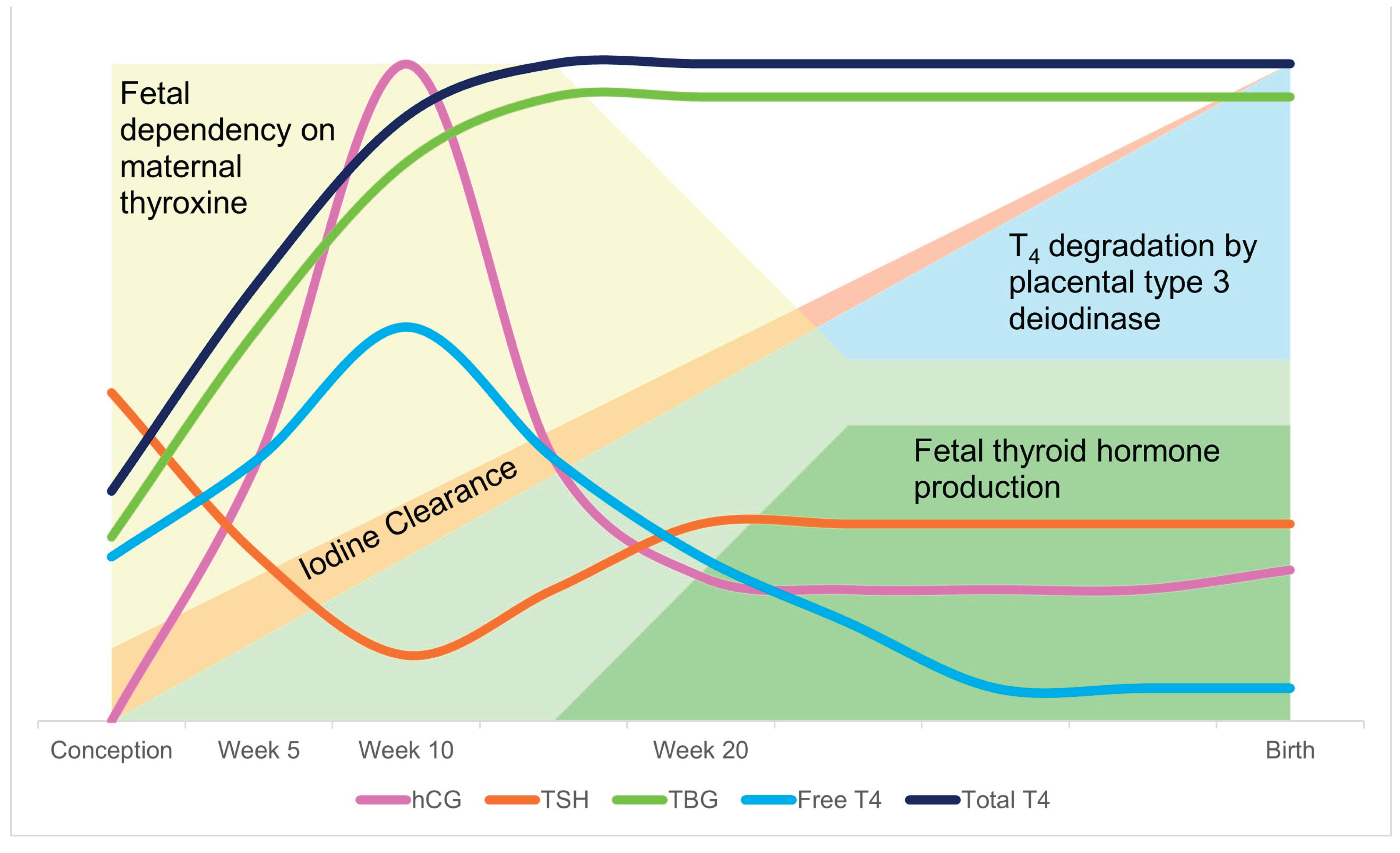

Thyroid Hormones and Placenta

The Critical Role of Thyroid Hormones for Fetal Development

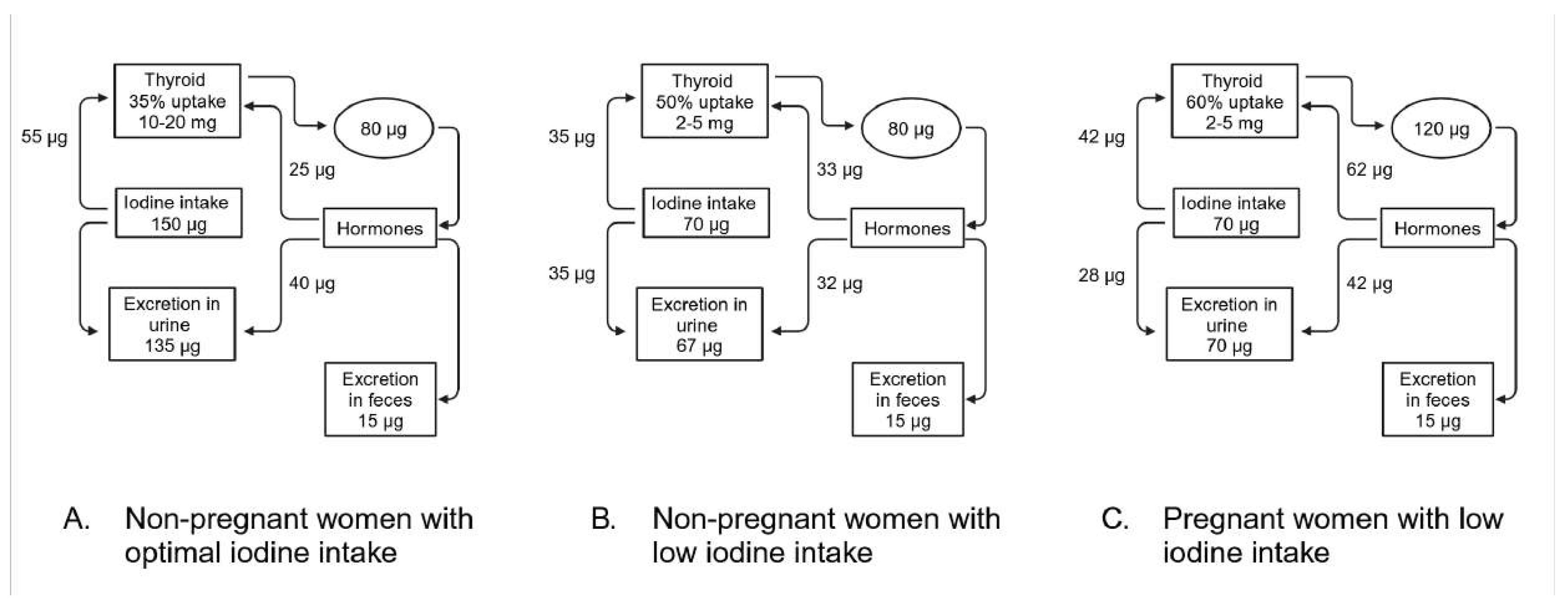

Iodine Metabolism During Pregnancy

Iodide Requeriment During Pregnancy

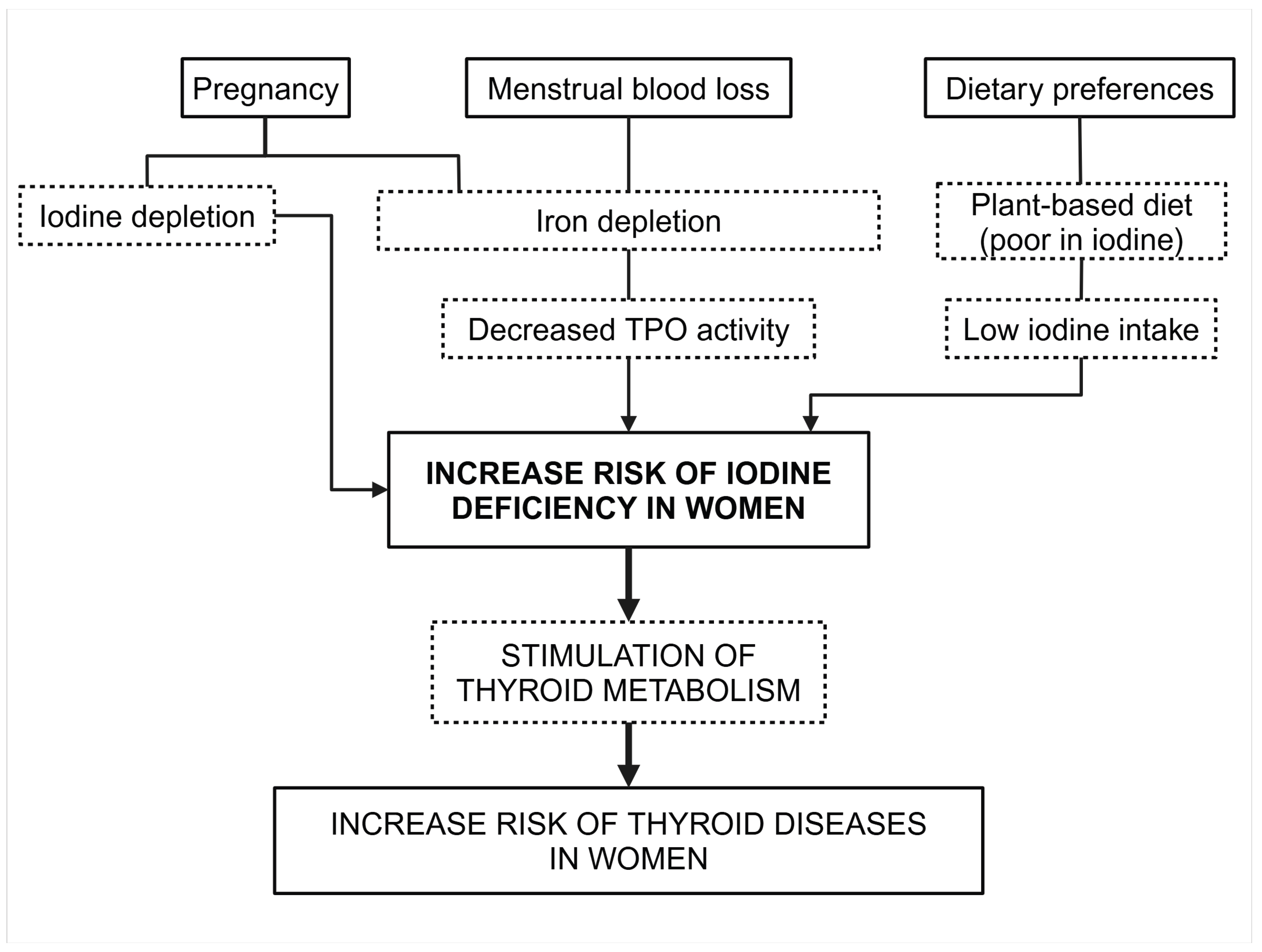

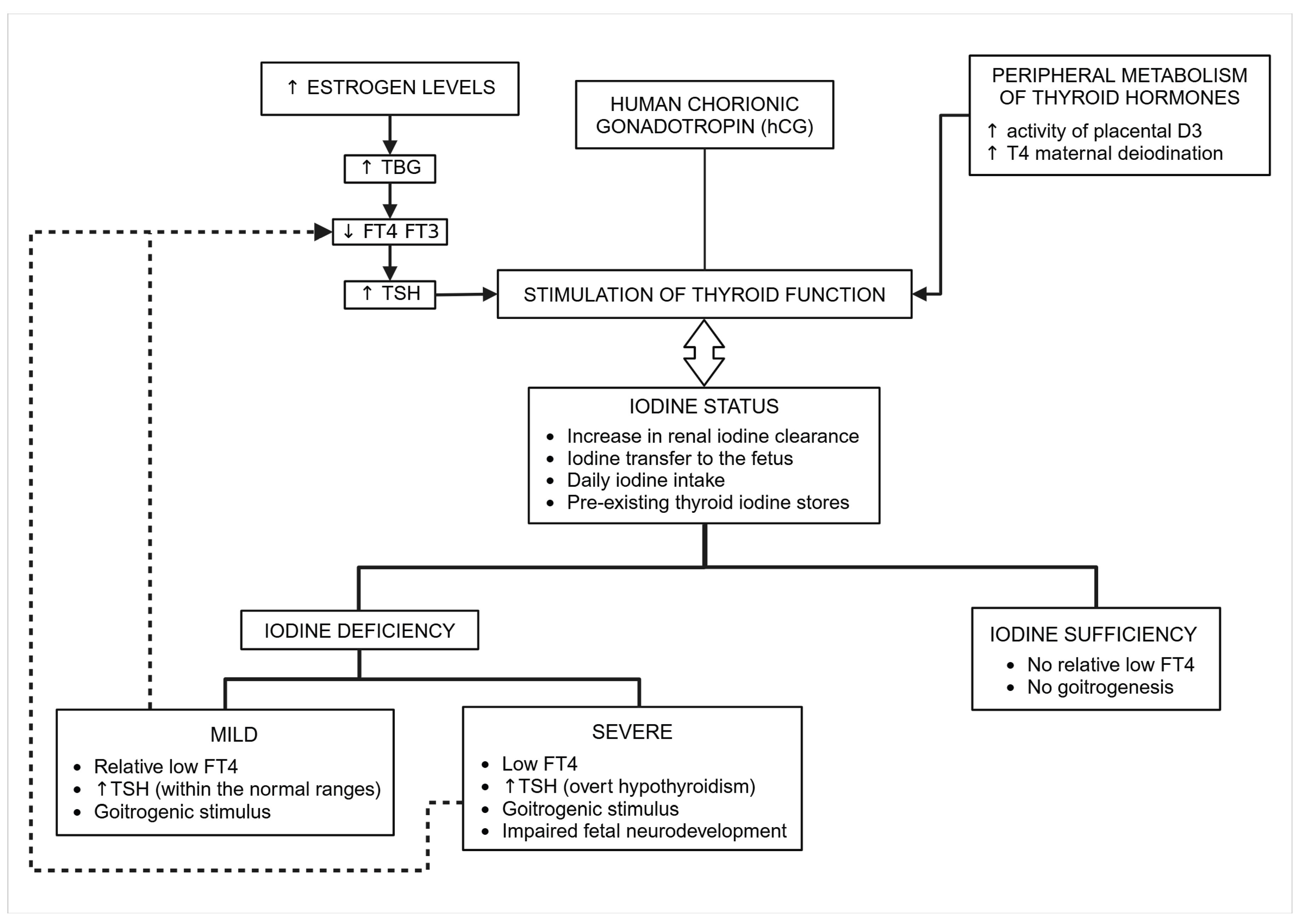

Physiological Adaptation of Thyroid Function During Pregnancy

Clinical and Biological Consequences of Mild Iodine Deficiency in Pregnant Women and Newborns

Clinical and Biological Consequences of Severe Iodine Deficiency In pregnant Women and Newborns

Iodine Excess

2. Discussion

3. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Publisher’s note

References

- Sorrenti, S.; Baldini, E.; Pironi, D.; Lauro, A.; D'Orazi, V.; Tartaglia, F.; et al. Iodine: Its Role in Thyroid Hormone Biosynthesis and Beyond. Nutrients. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnaro-Green, A.; Abalovich, M.; Alexander, E.; Azizi, F.; Mestman, J.; Negro, R.; et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011, 21, 1081–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B. The effects of iodine deficiency in pregnancy and infancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012, 26 (Suppl 1), 108–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, D.; Korevaar, T.I.M.; Bath, S.C.; Murcia, M.; Dineva, M.; Llop, S.; et al. Association of Maternal Iodine Status With Child IQ: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 104, 5957–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.N.; Lazarus, J.H.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Zimmermann, M.B. Consequences of iodine deficiency and excess in pregnant women: an overview of current knowns and unknowns. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016, 104 (Suppl 3), 918S–23S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Asuka, E.; Fingeret, A. Physiology, Thyroid Function. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Oppenheimer, J.H. Role of plasma proteins in the binding, distribution and metabolism of the thyroid hormones. N Engl J Med. 1968, 278, 1153–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.; Sharma, R.; Kaur, K. An unusual 'w' shaped thyroid gland with absence of isthmus - a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014, 8, AD03–4. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.S.; Farhana, A. Histology, Thyroid Gland. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Shahid, M.A.; Ashraf, M.A.; Sharma, S. Physiology, Thyroid Hormone. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Köhrle, J. Selenium, Iodine and Iron-Essential Trace Elements for Thyroid Hormone Synthesis and Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, J.P.; Carrasco, N.; Masini-Repiso, A.M. Dietary I(-) absorption: expression and regulation of the Na(+)/I(-) symporter in the intestine. Vitam Horm. 2015, 98, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Levay, B.; Lantos, A.; Sinkovics, I.; Slezak, A.; Toth, E.; Dohan, O. The master role of polarized NIS expression in regulating iodine metabolism in the human body. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2023, 67, 256–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullur, R.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Brent, G.A. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2014, 94, 355–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiga-Carvalho, T.M.; Chiamolera, M.I.; Pazos-Moura, C.C.; Wondisford, F.E. Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis. Compr Physiol. 2016, 6, 1387–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-e-Sousa, R.H.; Hollenberg, A.N. Minireview: The neural regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Endocrinology. 2012, 153, 4128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiamolera, M.I.; Wondisford, F.E. Minireview: Thyrotropin-releasing hormone and the thyroid hormone feedback mechanism. Endocrinology. 2009, 150, 1091–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.P.; Dupuy, C. Thyroid hormone biosynthesis and release. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 458, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, N. Iodide transport in the thyroid gland. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993, 1154, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royaux, I.E.; Suzuki, K.; Mori, A.; Katoh, R.; Everett, L.A.; Kohn, L.D.; Green, E.D. Pendrin, the protein encoded by the Pendred syndrome gene (PDS), is an apical porter of iodide in the thyroid and is regulated by thyroglobulin in FRTL-5 cells. Endocrinology. 2000, 141, 839–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyffels, L.; Strickaert, A.; Virreira, M.; Massart, C.; Van Sande, J.; Wauquier, C.; et al. Anoctamin-1/TMEM16A is the major apical iodide channel of the thyrocyte. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014, 307, C1102–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Jeso, B.; Arvan, P. Thyroglobulin From Molecular and Cellular Biology to Clinical Endocrinology. Endocr Rev. 2016, 37, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto, I.; Pusztaszeri, M.; Mavromati, M. H2O2 Metabolism in Normal Thyroid Cells and in Thyroid Tumorigenesis: Focus on NADPH Oxidases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameziane-El-Hassani, R.; Morand, S.; Boucher, J.-L.; Frapart, Y.-M.; Apostolou, D.; Agnandji, D.; et al. Dual oxidase-2 has an intrinsic Ca2+-dependent H2O2-generating activity. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 30046–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Driessens, N.; Costa, M.; De Deken, X.; Detours, V.; Corvilain, B.; et al. Roles of hydrogen peroxide in thyroid physiology and disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92, 3764–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citterio, C.E.; Targovnik, H.M.; Arvan, P. The role of thyroglobulin in thyroid hormonogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourian, A.R. Metabolic pathways of tetraidothyronine and triidothyronine production by thyroid gland: a review of articles. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnidehou, S.; Caillou, B.; Talbot, M.; Ohayon, R.; Kaniewski, J.; Noël-Hudson, M.-S.; et al. Iodotyrosine dehalogenase 1 (DEHAL1) is a transmembrane protein involved in the recycling of iodide close to the thyroglobulin iodination site. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1574–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; McInnes, J.; Kizilirmak, C.; Rehders, M.; Qatato, M.; Wirth, E.K.; et al. Interdependence of thyroglobulin processing and thyroid hormone export in the mouse thyroid gland. Eur J Cell Biol. 2017, 96, 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.C.; Privalsky, M.L. Thyroid hormones, t3 and t4, in the brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refetoff, S. Thyroid Hormone Serum Transport Proteins. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.

- Copyright © 2000-2025, MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- Sanguinetti, C.; Minniti, M.; Susini, V.; Caponi, L.; Panichella, G.; Castiglione, V.; et al. The Journey of Human Transthyretin: Synthesis, Structure Stability, and Catabolism. Biomedicines. 2022;10(8).

- Landers, K.; Richard, K. Traversing barriers - How thyroid hormones pass placental, blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 458, 22–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowska-Myjak, B.; Strawa, A.; Zborowska, H.; Jakimiuk, A.; Skarzynska, E. Associations between the thyroid panel and serum protein concentrations across pregnancy. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, R.P.; Visser, T.J. Metabolism of Thyroid Hormone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- Russo, S.C.; Salas-Lucia, F.; Bianco, A.C. Deiodinases and the Metabolic Code for Thyroid Hormone Action. Endocrinology. 2021, 162, bqab059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereben, B.; Zavacki, A.M.; Ribich, S.; Kim, B.W.; Huang, S.A.; Simonides, W.S.; et al. Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr Rev. 2008, 29, 898–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Landers, K.; Li, H.; Mortimer, R.H.; Richard, K. Delivery of maternal thyroid hormones to the fetus. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 22, 164–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubiere, L.S.; Vasilopoulou, E.; Bulmer, J.N.; Taylor, P.M.; Stieger, B.; Verrey, F.; et al. Expression of thyroid hormone transporters in the human placenta and changes associated with intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2010, 31, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, E.A.; Wang, Y.X.; Ding, Y.B. The interplay between thyroid hormones and the placenta: a comprehensive reviewdagger. Biol Reprod. 2020, 102, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Vega, S.; Armella, A.; Mennickent, D.; Loyola, M.; Covarrubias, A.; Ortega-Contreras, B.; et al. High levels of maternal total tri-iodothyronine, and low levels of fetal free L-thyroxine and total tri-iodothyronine, are associated with altered deiodinase expression and activity in placenta with gestational diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0242743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Gutierrez, E.; Veas, C.; Leiva, A.; Escudero, C.; Sobrevia, L. Is a low level of free thyroxine in the maternal circulation associated with altered endothelial function in gestational diabetes? Front Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Brent, G.A. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2012, 122, 3035–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnin, M.; Kondos-Devcic, D.; Chincarini, G.; Cumberland, A.; Richardson, S.J.; Tolcos, M. Role of thyroid hormones in normal and abnormal central nervous system myelination in humans and rodents. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 61, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.Y.; Leonard, J.L.; Davis, P.J. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010, 31, 139–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Goglia, F.; Leonard, J.L. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Su, Y.F.; Hsieh, M.T.; Lin, S.; Meng, R.; London, D.; et al. Nuclear monomeric integrin alphav in cancer cells is a coactivator regulated by thyroid hormone. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Sun, M.; Tang, H.Y.; Lin, C.; Luidens, M.K.; Mousa, S.A.; et al. L-Thyroxine vs. 3,5,3'-triiodo-L-thyronine and cell proliferation: activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C980–91. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P.J.; Davis, F.B.; Mousa, S.A.; Luidens, M.K.; Lin, H.Y. Membrane receptor for thyroid hormone: physiologic and pharmacologic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011, 51, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Feng, X.; Lin, Z.; Li, X.; Su, S.; Cheng, H.; et al. Thyroid hormone transport and metabolism are disturbed in the placental villi of miscarriage. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyetei-Anum, C.S.; Roggero, V.R.; Allison, L.A. Thyroid hormone receptor localization in target tissues. J Endocrinol. 2018, 237, R19–R34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; van der Sman, A.S.E.; Groeneweg, S.; de Rooij, L.J.; Visser, W.E.; Peeters, R.P.; Meima, M.E. Thyroid Hormone Transporters in a Human Placental Cell Model. Thyroid. 2022, 32, 1129–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabl, J.; de Maiziere, L.; Huttenbrenner, R.; Hutter, S.; Juckstock, J.; Mahner, S.; et al. Cell Type- and Sex-Specific Dysregulation of Thyroid Hormone Receptors in Placentas in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11).

- Barber, K.J.; Franklyn, J.A.; McCabe, C.J.; Khanim, F.L.; Bulmer, J.N.; Whitley, G.S.; Kilby, M.D. The in vitro effects of triiodothyronine on epidermal growth factor-induced trophoblast function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90, 1655–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.A.; Dorfman, D.M.; Genest, D.R.; Salvatore, D.; Larsen, P.R. Type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase is highly expressed in the human uteroplacental unit and in fetal epithelium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88, 1384–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.; Kachilele, S.; Hobbs, E.; Bulmer, J.N.; Boelaert, K.; McCabe, C.J.; et al. Placental iodothyronine deiodinase expression in normal and growth-restricted human pregnancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88, 4488–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, K.A.; Li, H.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Mortimer, R.H.; Richard, K. Transthyretin-thyroid hormone internalization by trophoblasts. Placenta. 2013, 34, 716–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhr, J.; Arbor, T.C.; Ackerman, K.M. Embryology, Gastrulation. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2024.

- Visciano, C.; Prevete, N.; Liotti, F.; Marone, G. Tumor-Associated Mast Cells in Thyroid Cancer. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2015, 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, J.; Jernigan, T.L. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010, 20, 327–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenhaut, C.; Christophe, D.; Vassart, G.; Dumont, J.; Roger, P.P.; Opitz, R. Ontogeny, Anatomy, Metabolism and Physiology of the Thyroid. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- Huget-Penner, S.; Feig, D.S. Maternal thyroid disease and its effects on the fetus and perinatal outcomes. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2020, 40, 1077–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset, B.; Dupuy, C.; Miot, F.; Dumont, J. Chapter 2 Thyroid Hormone Synthesis And Secretion. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- Goldsmit, G.S.; Valdes, M.; Herzovich, V.; Rodriguez, S.; Chaler, E.; Golombek, S.G.; Iorcansky, S. Evaluation and clinical application of changes in thyroid hormone and TSH levels in critically ill full-term newborns. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2011;39(1).

- La Gamma, E.F.; Paneth, N. Clinical importance of hypothyroxinemia in the preterm infant and a discussion of treatment concerns. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2012, 24, 172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, M.; Nicolini, U.; Jowett, T.; De Elvira, M.C.R.; Ekins, R.P.; Rodeck, C.H. MATURATION OF THYROID FUNCTION IN NORMAL HUMAN FOETUSES. Clinical Endocrinology. 1989, 31, 565–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Williams, F.L.R.; Delahunty, C.; Van Toor, H.; Wu, S.Y.; Ogston, S.A.; et al. Serum Thyroid Hormones in Preterm Infants and Relationships to Indices of Severity of Intercurrent Illness. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005, 90, 1271–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, J. Thyroid Hormones and Brain Development. Vitamins & Hormones. 71: Elsevier; 2005. p. 95-122.

- Rovet, J.F. The Role of Thyroid Hormones for Brain Development and Cognitive Function. In: Szinnai G, editor. Endocrine Development. 26: S. Karger AG; 2014. p. 26-43.

- Moog, N.K.; Entringer, S.; Heim, C.; Wadhwa, P.D.; Kathmann, N.; Buss, C. Influence of maternal thyroid hormones during gestation on fetal brain development. Neuroscience. 2017, 342, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Suzuki, M. Congenital Hypothyroidism and Brain Development: Association With Other Psychiatric Disorders. Front Neurosci. 2021, 15, 772382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo, M.C.; Gianini, A.; Pancetti, F.; Azkcona, G.; Alarcón, L.; Lizana, R.; et al. Maternal Hypothyroxinemia Impairs Spatial Learning and Synaptic Nature and Function in the Offspring. Endocrinology. 2008, 149, 5097–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallie, P.D.; Naicker, T. The placenta as a window to the brain: A review on the role of placental markers in prenatal programming of neurodevelopment. Intl J of Devlp Neuroscience. 2019, 73, 41–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.B.; Neira, F.J.; Moreno-Sosa, T.; Michel Lara, M.C.; Viruel, L.B.; Germanó, M.J.; et al. Placental leukocyte infiltration accompanies gestational changes induced by hyperthyroidism. Reproduction. 2023, 165, 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, H.; Amin, P.; Lazarus, J.H. Hyperthyroidism and pregnancy. BMJ. 2008, 336, 663–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delange, F. The disorders induced by iodine deficiency. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association. 1994, 4, 107–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delange, F.; Camus, M.; Ermans, A.M. Circulating thyroid hormones in endemic goiter. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1972, 34, 891–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercbergs, A. Clinical Implications and Impact of Discovery of the Thyroid Hormone Receptor on Integrin alphavbeta3-A Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowachirapant, S.; Jaiswal, N.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Galetti, V.; Stinca, S.; Mackenzie, I.; et al. Effect of iodine supplementation in pregnant women on child neurodevelopment: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017, 5, 853–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dineva, M.; Fishpool, H.; Rayman, M.P.; Mendis, J.; Bath, S.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of iodine supplementation on thyroid function and child neurodevelopment in mildly-to-moderately iodine-deficient pregnant women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020, 112, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.M.; Laurberg, P.; Iversen, E.; Knudsen, P.R.; Gregersen, H.E.; Rasmussen, O.S.; et al. Amelioration of some pregnancy-associated variations in thyroid function by iodine supplementation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993, 77, 1078–83. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.E.; Silva, S. Interrelationships among serum thyroxine, triiodothyronine, reverse triiodothyronine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone in iodine-deficient pregnant women and their offspring: effects of iodine supplementation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981, 52, 671–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinoer, D.; Delange, F.; Laboureur, I.; de Nayer, P.; Lejeune, B.; Kinthaert, J.; Bourdoux, P. Maternal and neonatal thyroid function at birth in an area of marginally low iodine intake. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992, 75, 800–5. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, N.; Bülow, I.; Laurberg, P.; Ovesen, L.; Perrild, H.; Jørgensen, T. Parity is associated with increased thyroid volume solely among smokers in an area with moderate to mild iodine deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002, 146, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, M.; Sorvillo, F.; Mazziotti, G.; Balzano, S.; Iorio, S.; Savoia, A.; et al. The influence of parity on multinodular goiter prevalence in areas with moderate iodine deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002, 25, 442–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Bath, S.; Farrand, C.; Gerasimov, G.; Moreno-Reyes, R. Prevention and control of iodine deficiency in the WHO European Region: adapting to changes in diet and lifestyle. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2024.

- Zimmermann, M.; Trumbo, P.R. Iodine. Adv Nutr. 2013, 4, 262–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, D.; Wiafe, Y.A.; Danquah, K.O.; Adankwah, E.; Amissah, G.A.; Odame, A. Urinary iodine concentration and thyroid volume of pregnant women attending antenatal care in two selected hospitals in Ashanti Region, Ghana: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018, 18, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J. Thyroid Regulation and Dysfunction in the Pregnant Patient. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA)2000.

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Boelaert, K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2015, 3, 286–95. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.E.; Peeters, R.P. Interpretation of thyroid function tests during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 34, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Burgi, H.; Hurrell, R.F. Iron deficiency predicts poor maternal thyroid status during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92, 3436–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Adou, P.; Torresani, T.; Zeder, C.; Hurrell, R. Persistence of goiter despite oral iodine supplementation in goitrous children with iron deficiency anemia in Côte d'Ivoire. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Reyes, R.; Corvilain, B.; Daelemans, C.; Wolff, F.; Fuentes Peña, C.; Vandevijvere, S. Iron Deficiency Is a Risk Factor for Thyroid Dysfunction During Pregnancy: A Population-Based Study in Belgium. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2021, 31, 1868–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.Y.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Arnold, M.; Langhans, W.; Hurrell, R.F. Iron deficiency anemia reduces thyroid peroxidase activity in rats. J Nutr. 2002, 132, 1951–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejbjerg, P.; Knudsen, N.; Perrild, H.; Laurberg, P.; Andersen, S.; Rasmussen, L.B.; et al. Estimation of iodine intake from various urinary iodine measurements in population studies. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2009, 19, 1281–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinoer, D. The regulation of thyroid function in pregnancy: pathways of endocrine adaptation from physiology to pathology. Endocr Rev. 1997, 18, 404–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparre, L.S.; Brundin, J.; Carlström, K.; Carlström, A. Oestrogen and thyroxine-binding globulin levels in early normal pregnancy. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1987, 114, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjöldebrand, L.; Brundin, J.; Carlström, A.; Pettersson, T. Thyroid associated components in serum during normal pregnancy. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1982, 100, 504–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korevaar, T.I.M.; Medici, M.; Visser, T.J.; Peeters, R.P. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: new insights in diagnosis and clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 610–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinoer, D.; de Nayer, P.; Bourdoux, P.; Lemone, M.; Robyn, C.; van Steirteghem, A.; et al. Regulation of maternal thyroid during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990, 71, 276–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Reyes, R.; Glinoer, D.; Van Oyen, H.; Vandevijvere, S. High prevalence of thyroid disorders in pregnant women in a mildly iodine-deficient country: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013, 98, 3694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinoer, D.; De Nayer, P.; Delange, F.; Lemone, M.; Toppet, V.; Spehl, M.; et al. A randomized trial for the treatment of mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995, 80, 258–69. [Google Scholar]

- Thilly, C.H.; Vanderpas, J.B.; Bebe, N.; Ntambue, K.; Contempre, B.; Swennen, B.; et al. Iodine deficiency, other trace elements, and goitrogenic factors in the etiopathogeny of iodine deficiency disorders (IDD). Biol Trace Elem Res. 1992, 32, 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, H.; Dudenhausen, J.W.; Wenzel, K.W.; Saling, E. Amniotic fluid concentrations of 3,3',5'-tri-iodothyronine (reverse T3), 3,3'-di-iodothyronine, 3,5,3'-tri-iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in normal and complicated pregnancy. Clinical Endocrinology. 1979, 10, 355–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeke, J.; Dybkjaer, L.; Granlie, K.; Eskjaer Jensen, S.; Kjaerulff, E.; Laurberg, P.; Magnusson, B. A longitudinal study of serum TSH, and total and free iodothyronines during normal pregnancy. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1982, 101, 531–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinoer, D.; Lemone, M.; Bourdoux, P.; De Nayer, P.; DeLange, F.; Kinthaert, J.; LeJeune, B. Partial reversibility during late postpartum of thyroid abnormalities associated with pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992, 74, 453–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi, M.; Amato, G.; Biondi, B.; Mazziotti, G.; Del Buono, A.; Rotonda Nicchio, M.; et al. Parity as a thyroid size-determining factor in areas with moderate iodine deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85, 4534–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Aeberli, I.; Andersson, M.; Assey, V.; Yorg, J.A.J.; Jooste, P.; et al. Thyroglobulin is a sensitive measure of both deficient and excess iodine intakes in children and indicates no adverse effects on thyroid function in the UIC range of 100-299 μg/L: a UNICEF/ICCIDD study group report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013, 98, 1271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, K.; McMullan, P.; Kayes, L.; McCance, D.; Hunter, A.; Woodside, J.V. Thyroglobulin levels among iodine deficient pregnant women living in Northern Ireland. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022, 76, 1542–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morreale de Escobar, G.; Pastor, R.; Obregon, M.J.; Escobar del Rey, F. Effects of maternal hypothyroidism on the weight and thyroid hormone content of rat embryonic tissues, before and after onset of fetal thyroid function. Endocrinology. 1985, 117, 1890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contempré, B.; Jauniaux, E.; Calvo, R.; Jurkovic, D.; Campbell, S.; de Escobar, G.M. Detection of thyroid hormones in human embryonic cavities during the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993, 77, 1719–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sava, L.; Tomaselli, L.; Runello, F.; Belfiore, A.; Vigneri, R. Serum thyroglobulin levels are elevated in newborns from iodine-deficient areas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986, 62, 429–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B. Iodine deficiency. Endocr Rev. 2009, 30, 376–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PHAROAHPOD; CONNOLLYKJ; EKINSRP; HARDINGAG MATERNAL THYROID HORMONE LEVELS IN PREGNANCY AND THE SUBSEQUENT COGNITIVE AND MOTOR PERFORMANCE OF THE CHILDREN. Clinical Endocrinology. 1984, 21, 265–70. [CrossRef]

- PHAROAHPOD; CONNOLLYKJ A Controlled Trial of lodinated Oil for the Prevention of Endemic Cretinism: A Long-Term Follow-Up. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1987, 16, 68–73. [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, P.O.; Connolly, K.J. Effects of maternal iodine supplementation during pregnancy. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1991, 66, 145–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouri, M.; Margetaki, K.; Koutra, K.; Kyriklaki, A.; Daraki, V.; Roumeliotaki, T.; et al. Urinary iodine concentrations in preschoolers and cognitive development at 4 and 6 years of age, the Rhea mother-child cohort on Crete, Greece. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2024, 85, 127486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilly, C.H.; Swennen, B.; Bourdoux, P.; Ntambue, K.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Gillies, J.; Vanderpas, J.B. The epidemiology of iodine-deficiency disorders in relation to goitrogenic factors and thyroid-stimulating-hormone regulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(2 Suppl):267S-70S.

- Moreno-Reyes, R.; Boelaert, M.; el Badawi, S.; Eltom, M.; Vanderpas, J.B. Endemic juvenile hypothyroidism in a severe endemic goitre area of Sudan. Clinical Endocrinology. 1993, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Dos Santos, M.C.; Gonçalves, C.F.L.; Vaisman, M.; Ferreira, A.C.F.; de, C.a.r.v.a.l.h.o.DP. Impact of flavonoids on thyroid function. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvilain, B.; Contempré, B.; Longombé, A.O.; Goyens, P.; Gervy-Decoster, C.; Lamy, F.; et al. Selenium and the thyroid: how the relationship was established. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(2 Suppl):244S-8S.

- Contempré, B.; Duale, N.L.; Dumont, J.E.; Ngo, B.; Diplock, A.T.; Vanderpas, J. Effect of selenium supplementation on thyroid hormone metabolism in an iodine and selenium deficient population. Clinical Endocrinology. 1992, 36, 579–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Nascimento, C.; Nunes, M.T. Perchlorate, nitrate, and thiocyanate: Environmental relevant NIS-inhibitors pollutants and their impact on thyroid function and human health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 995503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, J.M. Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, J.M.; Puche-Juarez, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Gonzalez-Palacios, P.; Rivas, A.; Ochoa, J.J.; Diaz-Castro, J. Implications of Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Offspring Development: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2024;16(11).

- Brambilla, M.M.; Perrone, S.; Shulhai, A.M.; Ponzi, D.; Paterlini, S.; Pisani, F.; et al. Systematic review on Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in breastmilk and neuro-behavioral development: Insight into the early ages of life. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2025, 169, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.N.; Okosieme, O.E.; Murphy, R.; Hales, C.; Chiusano, E.; Maina, A.; et al. Maternal perchlorate levels in women with borderline thyroid function during pregnancy and the cognitive development of their offspring: data from the Controlled Antenatal Thyroid Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014, 99, 4291–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tu, F.; Wan, Y.; Qian, X.; Mahai, G.; Wang, A.; et al. Associations of Trimester-Specific Exposure to Perchlorate, Thiocyanate, and Nitrate with Childhood Neurodevelopment: A Birth Cohort Study in China. Environ Sci Technol. 2023, 57, 20480–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, P.H.; Cardona, G.R.; Fang, S.L.; Previti, M.; Alex, S.; Carrasco, N.; et al. Escape from the acute Wolff-Chaikoff effect is associated with a decrease in thyroid sodium/iodide symporter messenger ribonucleic acid and protein. Endocrinology. 1999, 140, 3404–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, K.; Georgopoulos, N.; Kyriazopoulou, V.; Vagenakis, A.G. Iodine-Induced hypothyroidism. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2001, 11, 501–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, K.J.; Boston, B.A.; Pearce, E.N.; Sesser, D.; Snyder, D.; Braverman, L.E.; et al. Congenital hypothyroidism caused by excess prenatal maternal iodine ingestion. J Pediatr. 2012, 161, 760–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanoine, J.P.; Pardou, A.; Bourdoux, P.; Delange, F. Withdrawal of iodinated disinfectants at delivery decreases the recall rate at neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism. Arch Dis Child. 1988, 63, 1297–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, I.B.; Knudsen, N.; Jørgensen, T.; Perrild, H.; Ovesen, L.; Laurberg, P. Thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin autoantibodies in a large survey of populations with mild and moderate iodine deficiency. Clinical Endocrinology. 2003, 58, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosso, L.; Margozzini, P.; Trejo, P.; Domínguez, A.; Solari, S.; Valdivia, G.; Arteaga, E. [Thyroid stimulating hormone reference values derived from the 2009-2010 Chilean National Health Survey]. Rev Med Chil. 2013, 141, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Han, C.; Li, C.; Mao, J.; Wang, W.; Xie, X.; et al. Optimal and safe upper limits of iodine intake for early pregnancy in iodine-sufficient regions: a cross-sectional study of 7190 pregnant women in China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015, 100, 1630–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégier, C.; Dumery, G.; Luton, D. Iodine and Thyroid Maternal and Fetal Metabolism during Pregnancy. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossklaus, R.; Liesenkotter, K.P.; Doubek, K.; Volzke, H.; Gaertner, R. Iodine Deficiency, Maternal Hypothyroxinemia and Endocrine Disrupters Affecting Fetal Brain Development: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(10).

- Abel, M.H.; Caspersen, I.H.; Sengpiel, V.; Jacobsson, B.; Meltzer, H.M.; Magnus, P.; et al. Insufficient maternal iodine intake is associated with subfecundity, reduced foetal growth, and adverse pregnancy outcomes in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeaff, S.A. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy: the effect on neurodevelopment in the child. Nutrients. 2011, 3, 265–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpff, C.; De Schepper, J.; Tafforeau, J.; Van Oyen, H.; Vanderfaeillie, J.; Vandevijvere, S. Mild iodine deficiency in pregnancy in Europe and its consequences for cognitive and psychomotor development of children: a review. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013, 27, 174–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougma, K.; Aboud, F.E.; Harding, K.B.; Marquis, G.S. Iodine and mental development of children 5 years old and under: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2013, 5, 1384–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).