1. Introduction

As a result of COVID-19, a pediatric mental health emergency was declared by the American Academy of Pediatrics [

1]. Young children experienced significant increases in mental health concerns during and following COVID-19, including anxiety, emotion dysregulation, and tantrums [

2,

3]. This surge in emotional difficulties created challenges for caregivers, professionals, and paraprofessionals who interact with children. Specifically, access to mental health services has been limited, with significant waitlists reported nationwide [

4], underscoring a critical public health need for accessible interventions that can equip early childhood professionals (e.g., health professionals, educators, allied health professionals) with tools to support children experiencing emotional difficulties and behavioral problems.

Addressing emotional and behavioral concerns in families with young children (during their early formative years) is particularly crucial, as early experiences and environmental interactions significantly influence children's academic, emotional, and social development [

5]. To alleviate pressure on the mental health system, virtual and on-demand single-session interventions have emerged as promising tools for providing skill-training to individuals who might otherwise face delays in accessing support [

6]. Among these brief intervention approaches, simulation training has demonstrated superior outcomes in changing future behaviors and generalizing to real-world situations compared to traditional educational modalities (e.g., online static courses) [

7,

8].

1.1. VR Simulation Training for Professionals Who Serve Young Children.

Virtual reality (VR) simulations have shown promise in enhancing training across various medical, allied health, and education professions. In pediatric medical residency training, VR simulations have improved residents' skills in providing behavioral health anticipatory guidance and supporting vaccine adherence when coaching parent avatars, although additional research is needed to assess implementation in real clinic visits [

9,

10,

11]. Nursing students also reported increased preparedness for patient communications after engaging with AI-powered VR simulations [

12], and those who combined VR experiences with web-based modules demonstrated better knowledge acquisition and retention compared to web-based learning alone [

13]. Within education settings, VR simulation training has been used to improve teachers' understanding of child development, behavior management skills, and self-efficacy [

14,

15,

16]. While VR simulations have long been used in child mental health treatment (e.g., exposure-based and ADHD VR simulations) [

17]

, its application to directly train mental health professionals on approaches for interacting with young children is yet to be examined. Overall, initial research suggests that VR simulation training holds significant promise for educating professionals who work with young children; however, limitations remain, including the static nature of some VR simulations, small sample sizes, and a limited understanding of whether VR training leads to sustained changes in professional behavior.

1.2. VR Simulation Training Design Elements

A critical limitation of many current VR simulation training approaches is their lack of inclusivity. Most VR simulations do not feature avatars that reflect the cultural and linguistic diversity of the children and families that professionals serve [

18]. This is particularly concerning in the United States, where approximately 22% of households speak a language other than English, with Spanish being the most common [

19,

20]. Despite this, most VR simulation training for professionals remains monolingual, missing a critical opportunity to provide multilingual professional development. This gap is consequential, as professionals may struggle to effectively communicate technical information to children and families in a language or dialect different from their training, leading to confusion and reduced care quality [

19]. Culturally and linguistically responsive VR education offers a promising pathway to address these disparities by developing multilingual simulations and incorporating avatars that reflect the professionals, children, and families served [

21].

In addition to cultural and linguistic considerations, disparities in VR training effectiveness across demographic groups have been identified. Younger and male healthcare professionals have been found to perform better in VR simulations relative to their older and female colleagues [

22]. If unaddressed, such disparities could hinder efforts to build a diverse, skilled workforce capable of delivering high-quality care to young children and families.

Building on these needs and opportunities, we designed an innovative multilingual VR simulation designed to teach early childhood professionals evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions while prioritizing cultural and linguistic inclusivity.

1.3. VR Regulators

The VR Regulators simulations were developed to extend the reach of existing models [

23] by providing early childhood professionals with accessible, standardized training in evidence-based emotion management techniques that are consistent with Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) and Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM) Strategies [

24,

25,

26]. Within the VR simulation, professionals elect to complete the simulation in English or Spanish and select an avatar representative of children they typically serve (e.g., White, Hispanic, African American/Black, Asian). Participants also completed a brief video tutorial in which they learned strategic attention verbal (e.g., labeled praise, behavior descriptions, emotion labeling) and nonverbal skills (e.g., looking toward child) when the child avatar was demonstrating a prosocial behavior (e.g., calm, talking nicely to the participant, brave behavior). Similarly, they were taught selective ignoring skills (not looking at or speaking to the child avatar) when they were engaged in maladaptive behaviors (e.g., whining, name calling, temper tantrums, clingy behaviors). Through these practice opportunities, VR Regulators is designed to equip early childhood professionals with practical tools to support children’s emotional regulation in a culturally and linguistically responsive manner and reduce future risk of emotional or behavioral concerns.

1.4. The Current Study

The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate VR Regulators, a multilingual VR simulation designed to teach early childhood professionals (e.g., educators, healthcare, allied health) who regularly interact with young children evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions. Specifically, we examined whether completing the VR simulation was associated with changes in early childhood professionals’ intentions to use evidence-based emotion management strategies and their actual use of these strategies over time. Research Hypothesis 1. We hypothesized that early childhood professionals who completed VR Regulators would report increased intent to use evidence-based emotion management strategies one month after completing VR Regulators compared to the month prior. Research Hypothesis 2. We hypothesized that early childhood professionals would report an increase in their actual use of evidence-based emotion management strategies with children one month after completing VR Regulators compared to the month prior. Research Hypothesis 3. We explored whether early childhood professional sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, language, education, occupation) and/or VR simulation characteristics (e.g., simulation type, time spent in simulation) were associated with changes in professionals’ intent to use and actual use of evidence-based emotion management strategies. Research Hypothesis 4. We hypothesized that professionals would report high levels of acceptability and satisfaction with the VR Regulators simulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Early childhood professionals (N=107) were recruited from a major metropolitan area within the southeastern United States. Recruitment flyers were emailed and posted at pediatrician offices, early childhood learning institutions, and allied health professional offices. Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were adults aged 18 years or older, they were employed as an educator, child allied health professional, or medical professional who regularly works with children between the ages of 3 and 6 years old. Individuals were excluded from participation if they did not speak English or Spanish, had a history of significant motion sickness, were actively experiencing nausea and vomiting, or had a diagnosis of epilepsy. See

Table 1 for early childhood professional demographics. Demographic information was collected via Research Electronic Database Capture (REDCap) [

27]. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the university (20231355) and all participants who agreed to be in the study signed an informed consent. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the IRB.

2.2. Procedures

Participants completed informed consent and a survey collecting sociodemographic characteristics. Participants also completed brief baseline measures related to their own emotion regulation and how they manage young children’s strong emotions. Measures were provided to participants in English or Spanish based on their preference. Participants were then instructed to place the VR headset (i.e., Meta Quest Pro) on their head. Study personnel assisted participants with putting on the VR headset and ensured proper visual clarity of simulation and audio levels. Study personnel informed participants that they could stop the simulation at any time if they experienced nausea or motion sickness. Within the VR simulation, each participant watched a brief video tutorial that explained how to complete the simulation and then engaged in the VR simulation (temper tantrum or separation anxiety regulation simulation, based on their preference). Participants varied in the amount of time spent completing the Temper Tantrum Simulation (M = 844.03 seconds, SD = 284.63 seconds) and the Separation Anxiety Simulation: M = 912.00 seconds, SD = 316.82 seconds). Seventy-one participants completed the temper tantrum simulation, and thirty-six completed the separation anxiety simulation. Following completion of the VR simulation, participants were asked to complete brief outcome measures related to how they intended to manage children’s strong emotions over the next month and a satisfaction survey. One month following completion of the VR simulation, participants were emailed via REDCap a follow-up measure of how they managed children’s strong emotions over the past month.

2.2.1. Virtual Reality Regulators: Temper Tantrum Edition Simulation Overview

The simulation for managing children’s temper tantrums was based on behavioral strategies from PCIT. PCIT is an evidence-based intervention for reducing disruptive behavior in children aged 2-7, increasing compliance, and reducing parenting stress [

28]. It teaches caregivers skills to enhance the caregiver-child relationship and improve family functioning through live in-vivo coaching [

29]. Caregivers receive real-time feedback from therapists as they interact with their child, learning positive communication skills to reinforce appropriate behavior and ignore undesirable behavior.

The VR simulation of an adult-child interaction, during which a child avatar exhibits a temper tantrum, provides a mechanism for teaching PCIT techniques for managing children's strong emotions. Participants learned to implement positive attention by selecting verbal praise to reinforce desirable behavior and strategically ignoring undesirable behavior. The simulation emphasized removing both verbal and visual attention when ignoring negative behavior to prevent reinforcement. Participants also learned to model calm behavior and use coping skills. The VR tutorial stresses the importance of active observation, strategic attention, and self-monitoring as essential skills for managing child dysregulation and reinforcing positive behavior. Additional details of the simulation are provided in the following section.

VR Regulators: Temper Tantrum Edition Technical Aspects

The temper tantrum VR simulation began with a menu, in which participants were allowed to change the language (i.e., English or Spanish), the race/ethnicity of the child avatar (i.e., White, Hispanic, Asian, Black or African American), and the setting of the simulation (i.e., home, school, or medical office). After making their selections, participants viewed a tutorial delivered via an AI-generated text-to-speech video (Synthesia.io), allowing designers to provide identical content in both English and Spanish with ease.

The video explained the skills to manage strong emotions in children; skills that are commonly taught in PCIT (see section above). It further described how participants should interact with the child avatar to strategically attend to the child avatar’s appropriate behaviors (e.g., child avatar taking deep breaths, quieting down) and selectively ignoring negative attention seeking behaviors (e.g., crying, whining, negative statements toward the participant). Participants were also taught the timing of their nonverbal (i.e., looking at or looking away from the child avatar) and verbal management skills (i.e., choosing verbal phrases to be stated to the child) impacted the child avatar’s emotions. That is, if the participant looked at the child avatar or selected any verbal statement to the child avatar when the avatar was engaged in maladaptive behavior (e.g., yelling), the avatar’s temper tantrum would become worse. The tutorial visually demonstrated these skills using pre-recorded VR headset point-of-view footage, allowing participants to preview precisely how to perform the actions within the simulation. For example, if the participant were to look at the child avatar while the avatar was actively acting out, then the tantrum would intensify. As well, if the participant chose a critical statement (e.g. “Why aren’t you listening to me?”), the child avatar’s temper tantrum would also intensify (e.g., increased yelling and screaming). Similarly, if the participant chose a specific praise (e.g. “Thank you so much for staying calm.”) while the child avatar was quiet, the child avatar’s temper tantrum decreased. The timing of these verbal selections was critical in that if positive statements were provided when the child was demonstrating tantrum behaviors (e.g., crying or yelling), it had no effect on the child avatar’s tantrum. However, if the positive statement was provided when the child avatar was demonstrating calming behaviors (e.g., deep breaths, quiet), the tantrum level would decrease.

The avatar's tantrum appeared very similar to a real child's behavior, including screaming, crying, kicking, etc. The participants were able to gauge the child avatar's strong emotion levels, from the tantrum meter (ranging from a score of 0: completely calm to 100: extreme temper tantrum) that was visually presented as a sliding scale on the top left of the participant’s visual field. The temper tantrum simulation always began with a meter of 30 (as the simulation starts after the child avatar is told that they cannot use the participant’s phone to play games), and would end after one of three conditions was met: 1) the participant was able to reduce the tantrum meter to zero by using the proper strong emotion management, 2) the participant failed to manage the tantrum and the meter stayed between 80-100 for thirty-seconds (to prevent the participant from listening to constant yelling in their VR headset from the child avatar), or 3) if the participant was not able to manage the tantrum meter after five minutes of trying.

Once the simulation ended, a concluding educational AI-generated text-to-speech video was provided to all participants. The video varied depending on whether the participant succeeded or failed in managing the child avatar’s strong emotion. If the participant failed, the participants were re-educated via a video tutorial reiterating evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions. If the participant succeeded, then they were provided a video reaffirming their use of the evidence-based strategies they used within the simulation. Participants could choose to attempt the simulation again if they failed or they could choose to exit the simulation. Total time engaged in the simulation was tracked.

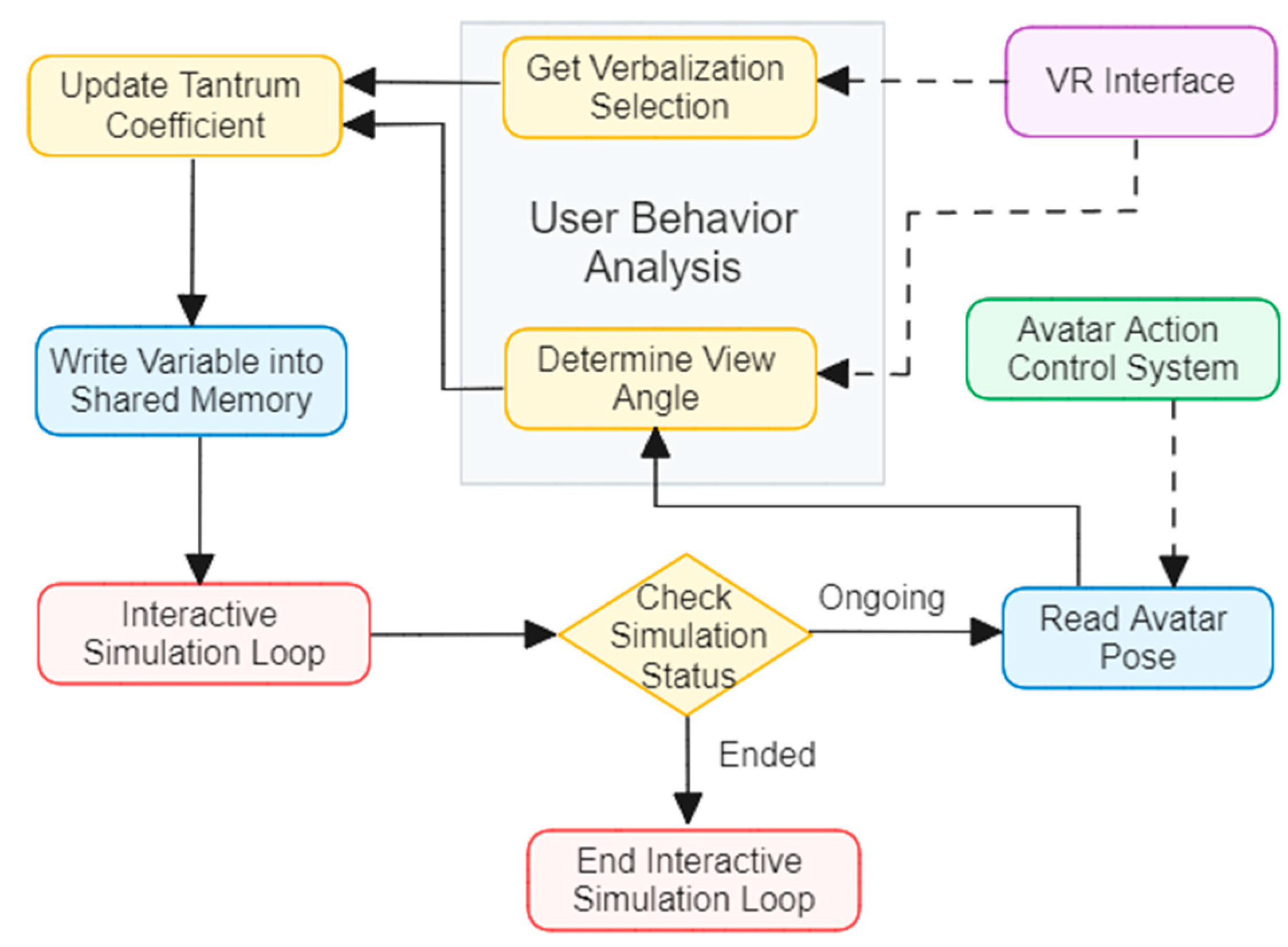

Avatar Interaction System

The temper tantrum VR simulation used a multimodal data collection system to create a realistic environment with a child avatar; in which the participant was provided real-time feedback through the behaviors of the avatar, in accordance with their verbal selection and visual-spatial angle. There were three main systems that worked cohesively to integrate outside data (i.e. participant responses) into the simulation. The avatar interaction system (AIS) was used to analyze the participants' visual and selected verbal responses to the child avatar, which was later used in the planning of the avatar's responsive action. That is, the participant’s actions, including their visual-spatial angle, phrase selection, and timing of their responses, determined whether the child avatar's strong emotion animations and verbalizations would intensify, or decrease. The AIS decided the appropriate next action of the avatar using a tantrum meter range (0-100), see

Figure 1. The AIS is used to connect the actions of the participant to the real-life reaction of the child avatar within the simulation.

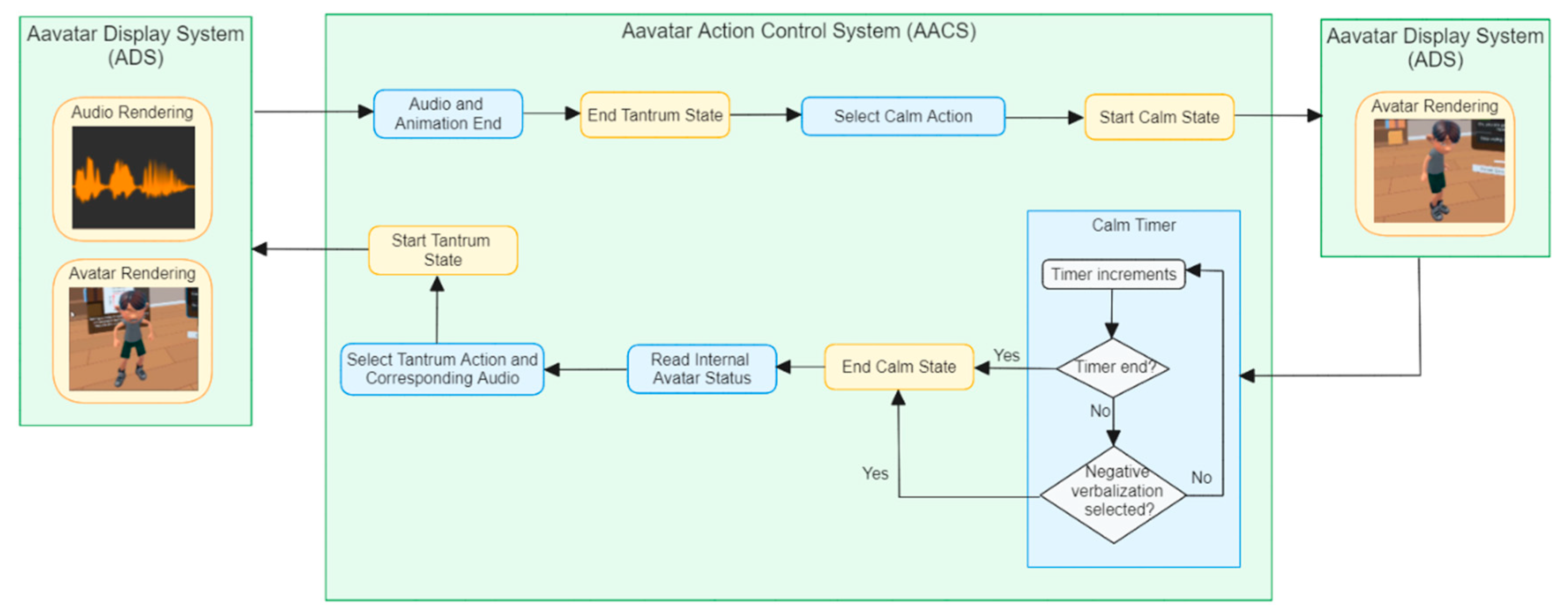

Avatar Action Control System

The avatar action control system (AACS) used the planned action from the AIS system and connected the information to the appropriate avatar actions. The AACS controls the actions of the avatar, choosing from a predetermined dataset of options (see

Figure 2). The avatar display system (ADS) used the information provided from the AACS system and was responsible for the display of the avatars actions. The ADS used the information passed from the AIS and AACS to display the predetermined reactions for the child avatar. These three models worked in unison to provide a smooth and realistic transition between actions of the participants and the avatar.

2.2.2. VR Regulators: Separation Anxiety Edition Technical Aspects

The separation anxiety and the temper tantrum VR simulations had a similar data flow and integration process but taught different necessary emotion management skills. Similar to the tantrum simulation, participants began with selecting their preferred language, ethnicity/race of the child avatar, and location (i.e., doctor’s office or school) on the menu screen. Once the participant selected the “Continue” button, an AI-generated text-to-speech tutorial video was provided. Within the tutorial video, the participants were taught to ignore negative anxiety-related behaviors by looking away (i.e. turning their head) from the child avatar and not providing attention to this behavior visually or with verbalizations; and to give positive visual and verbal attention to brave child avatar behaviors (e.g., child avatar is quiet, taking deep breaths, or separating from the adult participant). This simulation differed from the temper tantrum simulation by encouraging participants to model brave behaviors (e.g., walking further into the room). Some examples of anxious/avoidant behaviors exhibited by the child avatar included: whining, crying, staying close to the participant, screaming, and kicking. Participants were further able to determine the child avatar’s intensity of anxiety by looking at the anxiety meter (0-100).

The game portion of the simulation began with the participant stating in neutral language what the child was to expect (i.e., separation from the adult participant); this was done using AI-generated speech (i.e. not the participant speaking aloud). After that was shown, the child began exhibiting anxious behaviors at an anxiety meter of 70 (to resemble high levels of anxiety that a child may experience at the beginning of separating from an adult), and the participant was expected to manage them. The simulation would end if one of the three conditions was met: the participant was able to reduce the anxiety meter to zero by using the proper strong emotion management, the participant failed to lower the anxiety meter and it stayed between 80 to 100 for 30 seconds, and/or the participant could not properly manage the anxiety meter (i.e. lower the meter) after five minutes within the simulation. If the participant ignored these anxious behaviors, rewarded the child avatar for exhibiting calm behavior, selected neutral wording of what the child avatar was to expect, and/or modeled the wanted calm behavior for the child, then the child avatar would demonstrate a decrease in anxious behavior. If the participant chose a critical statement (e.g. you are making everyone late) when the child avatar was exhibiting anxious behavior or when the child avatar had calmed, then the anxious behaviors would intensify. If the participant chose a positive reinforcing statement (e.g. thank you so much for staying calm), and/or a statement that encourages the child to move further in the room (e.g. I love how brave you are being by walking further into the room) when the child avatar was displaying calm or brave behaviors, then the anxiety meter would decrease. Once the participant had failed or succeeded in managing the child’s strong emotions, a concluding direct presenter video was given. The concluding video varied according to the participant's success, similar to the temper tantrum simulation. Participants could choose to replay the simulation, or they could exit the simulation. Total time engaged in the simulation was tracked.

The separation anxiety VR simulation used a multimodal system, like that of the tantrum simulation (See

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). However, the separation anxiety VR multimodal system differed from the tantrum edition in that it not only included a child avatar but an adult avatar (i.e., teacher or healthcare provider) in order to better simulate a naturalistic situation in which a child must separate from their caregiver. Moreover, as the child avatar became calmer, the avatar walked farther into the room, distancing from the participant (i.e., successfully separating from the caregiver).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Information

A short demographic form was completed by all participants to gather sociodemographic information [i.e., age, gender, race, ethnicity, preferred language (1= English, 2= Spanish), education, profession, income range, Housing & Urban Development Low Income (based on income and household size)].

2.3.2. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18), was used to assess professionals’ self-report of their own frequency of dysregulation (e.g., When I'm upset, I have difficulty getting work done) based on a five-point Likert Scale (Almost Never to Almost Always). The DERS-18 yields a total Difficulties in Emotion Regulation score that ranges from 18 to 90, with higher scores indicating more self-reported difficulties with emotion regulation [

30]. The Total Difficulties score was used for this study. This measure was administered at baseline to establish participants' initial levels of emotion regulation prior to engaging in the VR simulation and to better understand how professionals’ own emotion regulation impacts the effectiveness of the VR simulations. The DERS-18 was also utilized to establish convergent validity of the Adult Responses to Children’s Strong Emotions Scale through examination of correlations between the two measures. Within the current sample, the internal consistency of the DERS-18 Total Score was good (Cronbach’s

α = .85)

2.3.3. Adult Responses to Children’s Strong Emotions Scale (ARCSES)

Adult-child interaction emotion-socialization strategies were measured via an adapted version of the Coping with Toddler’s Negative Emotions Scale [

31], which has been validated in English and Spanish). The adapted measure, the Adult Responses to Children’s Strong Emotions Scale (ARCSES), is an adult-report measure consisting of scenarios describing young children’s negative emotions (i.e., temper tantrum, separation anxiety). Within the baseline and the one-month surveys, participants rated the frequency they utilized various strategies for managing children’s temper tantrums and separation anxiety (1= 0-10% to 6= 91-100% of the time) on a brief 8-item scale [4 items related to managing temper tantrums (e.g., I praise them when they look like they are starting to calm down.) and 4 items related to managing separation anxiety (e.g., I model relaxation strategies they can use when feeling nervous or afraid)] over the past 30 days. Within the immediate post-test following VR simulation completion, participants rated on the same scale the extent they expected to utilize various strategies to manage children’s strong emotions over the next 30 days. A total score is computed from summing the items with scores ranging from 8 to 40, with higher scores representing more reported frequent use of evidence-based emotion regulation strategies. Strategies listed within the scale are based on evidence-based emotion regulation skills (Stump et al., 2009) that were taught in the VR simulations (e.g., praise, strategic attention, selective ignoring, modeling brave behaviors). Within the current sample, the internal consistency of the ARCSES Total Score was good (Cronbach’s

α = .86). The ARCSES total score significantly negatively correlated with the DERS-18 Total Score (

r = -0.27,

p < .01), establishing preliminary convergent validity of the measure.

2.3.4. Virtual Reality Satisfaction Survey

Study investigators created a 7-item questionnaire to measure participants’ perceptions of usability and interaction, knowledge acquisition, time and efficiency of the VR simulations, and comparative effectiveness relative to other learning methods. Participants rated the extent they agreed with statements (e.g., The virtual reality practice exercise helped me learn strategies more effectively than reading a book) provided from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely agree). Internal consistency for the scale was high (Cronbach’s α = .94). An open-ended response prompt was also provided for participants to complete regarding how to improve future iterations of the VR simulations.

2.3.5. Virtual Reality Simulation Duration

Virtual reality simulation duration was measured for each simulation type within REDCap. Research associates timestamped the participant record when participants started the VR simulation tutorial and at the end of the simulation. VR simulation duration was measured in seconds.

2.4. Data Analytic Plan

SPSS 29.0 was used for all study analyses. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all sociodemographic characteristics to better understand the professional composition of the sample.

2.4.1. Research Hypothesis 1

Pre-post paired sample t-tests were conducted to determine the impact of the VR simulation on professionals’ intent to engage in higher rates of using evidence-based strategies to manage strong child emotions as measured by the ARCSES, over the next month.

2.4.2. Research Hypothesis 2

Pre- one month follow-up paired sample t-tests were conducted to determine the impact of the VR simulation on professionals’ reported changes in using evidence-based strategies to manage strong child emotions over a one month period, also measured by the ARCSES.

2.4.3. Research Hypothesis 3

Given the diversity of participants and professional roles, we were interested in exploring the extent different participant characteristics (i.e., race, ethnicity, education, language, professional role) and VR simulation characteristics (i.e., type of VR simulation completed, length of time completing the VR simulation) were associated with reported outcomes (i.e., intent to engage in evidence-based emotion regulation practices, as measured by the ARCSES. Therefore, all categorical variables of interest were dummy coded (1= if variable, 0= if else).

To identify relevant predictor variables for inclusion in our regression analyses, we first conducted partial correlations between potential predictors and post-participant intent to use evidence-based strategies to respond to child strong emotion regulation scores (ARCSES post total score) while controlling for pre-adult emotion regulation strategies (ARCSES pre total score) used over the past month. This approach allowed us to identify variables that were meaningfully associated with post- VR simulation outcomes beyond their relationship with initial scores. Participant preferred language (

r = .27,

p < .05) and age (

r = .29,

p < .05) were both significantly correlated with participants’ intent to use evidence-based emotion regulation strategies over the next month (See

Appendix A Table A1 for preliminary correlations). Therefore, these two variables were included as predictors in subsequent linear regression analyses, with pre-professional self-reported emotion regulation strategy use entered as a covariate to account for baseline differences. Partial correlations were conducted to examine associations between potential predictors and participants’ reported use of evidence-based emotion regulation strategies to manage children’s strong emotions at one-month follow-up (ARCSES one month follow-up total score), controlling for their reported use of emotion regulation strategies (ARCSES pre total score). Caribbean ethnicity (

r = -.24,

p < .05), preferred language (

r = .49,

p < .01), and educator role (

r =

.23, p < .05) were all significantly correlated with participants’ reported use of evidence-based emotion regulation strategies to manage children’s strong emotions at one-month follow-up (See

Appendix A Table A2 for preliminary correlations). Therefore, these predictor variables were included in the linear regression analysis to examine what predicted changes in participants’ self-reported behaviors related to managing children’s strong emotions.

2.4.4. Research Hypothesis 4

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each VR Satisfaction Survey item. An open-ended response prompt invited participants to provide suggestions for improving future iterations of the VR simulation. Rapid qualitative analysis was conducted using a structured template summary approach [

32]. One research associate and the lead author independently reviewed all responses and summarized key points into templated domains. The team then met to reconcile summaries and identify recurring themes, supporting quotes, and actionable recommendations for VR simulation refinement.

2.4.5. Data Missingness

At one month follow-up, 85.98% of participants completed the follow-up assessment time point. Chi-square analyses (for sociodemographic characteristic categorical variables) and one-way ANOVAs (for quantitative variables including the pre- DERS total score, pre- ARCSES total score, and participant age) were conducted to determine if there were any differences between participants who completed the one-month follow-up assessment and those who were lost to follow-up. No significant differences existed in sociodemographic characteristics and participants’ pre-emotion regulation measures between participants who completed the one-month follow-up and those who were lost to follow-up.

3. Results

3.1. Research Hypotheses 1 and 2: Changes in Intent and Actual Use of Evidence-Based Emotion Regulation Strategies for Strong Child Emotions

Participants who completed a VR Regulators simulation reported a significant increase in their intent to use evidence-based strategies to manage children's strong emotions relative to their reported use of these strategies over the past month (See

Table 2). The effect size for this difference was medium (Cohen's

d = 0.51). However, at one month follow-up, professionals' actual use of evidence-based emotion management strategies did not change from pre-simulation reported frequencies of utilizing evidence-based emotion management strategies (See

Table 2).

3.2. Research Hypotheses 3: Characteristics Associated with Participants’ Intent and Actual Used of Evidence-Based Emotion Regulation Strategies for Strong Child Emotions

A hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the impact of professional and VR characteristics on participants' intent to employ evidence-based strategies for managing strong child emotions (See

Table 3). The overall model was statistically significant, accounting for 52% of the variance in post-intervention intent (

R² = .52,

p < .001). Baseline use of evidence-based strategies for managing strong child emotions emerged as the strongest predictor of post-intervention intent (

β = .61,

p < .001). This indicates that professionals who reported higher baseline use of these strategies were significantly more likely to express intent to use them after the VR simulation. Professional characteristics including preferred Spanish language (

β = .17,

p = .024) and older age (

β = .16,

p = .027) also significantly predicted post-simulation intent to use evidence-based strategies to manage children’s strong emotions. Specifically, participants whose preferred language was Spanish were more likely to intend to use evidence-based emotion management strategies. Similarly, older participants were more likely to report intentions to use evidence-based emotion management strategies.

A linear regression analysis was also conducted to investigate factors predicting participants' actual reported use of evidence-based strategies for managing children's strong emotions one month after completing the VR Regulators simulation (

Table 4). The overall model was statistically significant, explaining 34% of the variance in strategy use at follow-up (

R² = .34,

p < .001). Baseline use of evidence-based emotion management strategies significantly predicted follow-up use (

β = .31,

p < .001), suggesting that professionals who initially reported higher use of these strategies were more likely to continue using them one month after the VR simulation. Participants’ preferred language of Spanish was also a significant predictor (

β = .37,

p < .001) of improvements in using evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions at the one-month follow-up compared to professionals who preferred English. Professionals who identified as Caribbean were not predictive of evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions at follow-up.

3.3. Research Hypotheses 4: VR Simulation Satisfaction

Overall, participants reported high levels of satisfaction with their VR simulation experience (See

Table 5). Participants, on average, strongly agreed that the VR simulations were interactive and easy to use, indicating the technology was participant-friendly and accessible. They also endorsed learning valuable strategies to help manage children's strong emotions, which suggests the content of the simulations was relevant and informative. Moreover, the participants expressed a strong intention to use the strategies learned during the VR simulations, demonstrating the practical applicability of the knowledge gained. They also agreed the length of time required to learn and practice the skills within the simulations was reasonable, indicating the pacing and duration of the simulations were appropriate. Participants reported high levels of confidence in their abilities to use the strategies learned during the VR simulations. Notably, participants rated the VR practice exercises as being more effective for learning strategies compared to reading a book or watching a video example. Overall, satisfaction ratings indicated that the VR simulations were well-received and considered valuable for learning and applying strategies to manage children's strong emotions.

Beyond the satisfaction survey, participants were provided an open prompt regarding how the VR simulation might be improved, and a few themes emerged. The most common improvement suggestions were related to further personalization of the game, including the scenario/environment, timing restraint, font size, feedback, and verbal choices. For example, one participant suggested that “Adding the verbal characteristics to the sim [avatar] instead of phrases choices and selection,” might further aid the participant in obtaining strong emotion management skills. This suggests that by using active recall (as opposed to verbal selection) of the skills presented in the tutorial, the simulation may be more effective. Some participants found it tough to relate the simulation game scenario to what they experience in their work environment; for instance, one participant stated that it would help to, “include additional students in the classroom setting as that is more likely to be the actual scenario.” Some participants reported experiencing difficulties with the timing of the simulation; that is, they found it difficult to make verbal selections on time when the child avatar was calm. Possible refinements for these issues include adding a pause feature to the simulation or allowing spoken participant responses. One addition that is necessary is the creation of different font size options for those of varying visual abilities as some participants reported difficulty reading the text within the VR simulations.

Some participants also suggested the need for additional tutorials and practice prior to the simulation. Some suggestions included instilling a practice run prior to the simulation and having a tutorial on exactly what tools (e.g. controller button) are needed to accomplish the task. Many participants believed, “more time to practice and getting used to using it would be nice.” While research assistants instructed participants how to use the device, a guided video demonstration within the VR headset with practice opportunities for how to use the controllers (e.g., which buttons to use, how to use the controller as a pointer) and the headset (e.g., looking at or away from the child avatar) may be more effective.

4. Discussion

There is an urgent public health need to broaden access points for young children to receive support related to their mental health [

2,

4]. VR Regulators was developed as an early childhood professional development tool to train individuals who regularly interact with young children on how to manage their strong emotions (i.e., temper tantrums, separation anxiety). By delivering evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotion through a VR simulation, we aimed to equip professionals with practical skills that can be applied in everyday settings (e.g., educational settings, pediatrician offices, allied health professional settings such as speech and language, audiology, and mental health). This on-demand, scalable training model may help increase access to professional development, ultimately helping children who may need additional emotional and behavioral support. This pilot study investigated the efficacy of VR Regulators, a VR simulation, in improving early childhood professionals’ intent and actual use of evidence-based emotion management strategies. Findings offer valuable insights into the potential of VR as an engaging and potentially transformative professional development tool in early childhood educational, medical, and allied health fields.

4.1. Immediate Impact vs. Long-Term Behavior Change

A key finding of our study was the significant increase in early childhood professionals' intent to use evidence-based strategies immediately after completing the VR simulation. This aligns with previous research demonstrating the immediate positive effects of VR training on professionals' skills and confidence [

11,

12]. However, the lack of long-term change in actual use of evidence-based emotion strategies at the one-month follow-up raises important questions about the sustainability of brief VR-based learning as a stand-alone intervention. That is, while VR Regulators appears to effectively convey information and increase professional motivation in the short term, additional support and practice with the VR simulations may be necessary to translate emotion management skills into sustained professional practice. On average, participants completed the simulation experience in 14-15 minutes depending on the simulation they selected (i.e., temper tantrum, separation anxiety). While professionals may not need to repeat the tutorial portion, additional practice sessions in the simulation environment (e.g., complete VR Regulators until successfully completing the simulation, spaced practice over multiple days) could offer valuable opportunities for behavioral rehearsal of emotion management strategies before implementing them with children in their professional practice.

4.2. The Role of Professional Prior Experience, Age, and Language Preference

Participants past use of evidence-based emotion management strategies was a significant predictor of both post-VR simulation intent and follow-up use of evidence-based emotion management strategies. This finding underscores the importance of building on professionals' existing knowledge and practices, a principle well-established in adult learning theory [

33]. Findings also suggest that VR Regulators may be helpful as a tool for enhancing and refining professional emotion management skills rather than introducing entirely new skills.

The emergence of language preference as a significant predictor of both intents to use and actual use of evidence-based strategies is a novel and intriguing finding. Spanish-speaking professionals demonstrated greater intent to use the strategies post-intervention and reported higher use at follow-up compared to their English-speaking counterparts. This aligns with research highlighting the importance of linguistically appropriate training in healthcare and education [

19]. However, it is also unclear what is driving this linguistic difference. One possible explanation is that the VR Regulators helped addressed this gap, providing Spanish-speaking professionals with access to training resources more aligned with their cultural and linguistic needs. This is consistent with literature emphasizing the need for diversity in professional development tools, particularly in fields serving multilingual populations [

21], as most professional development opportunities offered in the United States are provided in English.

Converse to prior VR professional development research [

22], older professionals were somewhat more likely to have an increased intent to utilize evidence-based strategies for managing young children’s strong emotions following completion of the VR simulation. While not directly measured in this study, it may be that older professionals have more clinical or field experience. Over time, they may have encountered situations where traditional or non-evidence-based approaches were less effective for managing children’s strong emotions. It may be that the VR simulation provided older professionals with practical tools that could be easily integrated into their actual practices with children. Alternatively, unmeasured constructs such as prior knowledge of evidence-based emotion management strategies or professional attitudes toward technology may have influenced outcomes.

4.3. VR as a Tool for Inclusive Early Childhood Professional Development

High satisfaction rates reported by professionals, along with the notable benefits for Spanish-speaking participants, underscore the potential of VR as a tool for creating more inclusive and effective professional development experiences. Delivering brief VR simulation training directly within settings where professionals interact with children (e.g., educational, healthcare, allied health) may enhance access to evidence-based strategies for managing children’s strong emotions. Embedding this training within early childhood educational settings could be particularly impactful, as it allows for the dissemination of evidence-based practices within classrooms while maintaining teacher-to-child ratio standards. This approach is especially timely given the current pediatric mental health crisis and the urgent need to expand the reach of effective, scalable interventions.

Simulations like VR Regulators offer several advantages over traditional training methods. The VR simulations provide a standardized, immersive experience that can be easily scaled and adapted to different languages and cultural contexts. This addresses some of the challenges in providing consistent, high-quality training across different professional groups [

34]. Moreover, the interactive nature of VR may be particularly well-suited to teaching complex interpersonal skills, such as managing children's strong emotions, which are difficult to convey through didactic methods alone. VR simulations offer professionals a safe environment to practice managing high-intensity, potentially infrequent events like children's temper tantrums or separation anxiety, potentially enhancing their preparedness to effectively respond to intense child emotions in real-world situations.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

While pilot findings are promising, several limitations must be acknowledged. The lack of a control group limits our ability to attribute changes solely to the VR intervention. Future studies should employ randomized controlled designs to more rigorously assess the efficacy of VR Regulators compared to traditional training methods. The reliance on self-report measures, while common in professional development research, may not fully capture changes in actual practice. Incorporating direct behavioral observations in real-world settings would provide more robust evidence of the VR simulation’s impact. Additionally, the single follow-up point at one month provides limited insight into the longer-term effects of the VR simulation training. Longitudinal studies with longer-term follow-up assessments would offer a more comprehensive understanding of how VR-based learning translates into sustained practice change. The differential effects observed for Spanish-speaking professionals warrant further investigation. Future research should explore whether these benefits are replicated in other linguistic minority groups and examine the specific components of the VR experience that contribute to these outcomes. This could inform the development of other culturally and linguistically responsive and effective professional development tools.

4.5. Conclusions

VR Regulators demonstrates potential as an innovative, culturally responsive training tool for teaching early childhood professionals evidence-based strategies for managing young children's strong emotions. Its effectiveness, particularly for Spanish-speaking professionals, underscores the importance of developing culturally and linguistically appropriate VR simulation training tools. As professionals continue to grapple with the challenges of providing timely and effective mental health interventions for children, VR simulations may offer a scalable solution for equipping a diverse workforce with critical skills. However, the gap between immediate increased intent and sustained behavior change highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach to professional development. Future research and implementation efforts should focus on integrating VR-based learning with ongoing support and practice opportunities to potentially maximize its impact on real-world practice [

35].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alexis Landa, Jason F. Jent, Mei Ling Shyu, Duy Nguyen Data curation, Arianna De Landaburu, Lauren Pancavage, Abigail O’Reilly, Jennifer Coto, Ivette Cejas, Betty Alonso, Austin Garilli, Formal analysis, Jason F. Jent; Funding acquisition, Alexis Landa and Jason F. Jent; Investigation, Alexis Landa and Jason F. Jent; Methodology, Alexis Landa, Jason F. Jent, Mei Ling Shyu, Duy Nguyen; Project administration, Alexis Landa and Arianna De Landaburu; Resources, Jason F. Jent; Software, Jason F. Jent; Supervision, Jason F. Jent, Alexis Landa, Ruby Natale; Validation, Jason F. Jent; Visualization, Duy Nguyen and Jason jent; Writing – original draft, Alexis Landa, Jason F. Jent, Mei Ling Shyu, Duy Nguyen; Writing – review & editing, Jason F. Jent, Alexis Landa, Mei Ling Shyu, Duy Nguyen, Arianna De Landaburu, Jennifer Coto, Ivette Cejas, Betty Alonso, Dainelys Garcia, Elana Mansoor, Austin Garilli, Michelle Schladant, and Ruby Natale. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Children’s Trust (Grant Number: 2332-7571).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (protocol code: 20231355; date of approval for this study: 12/11/2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We extend our deepest appreciation to the participating families whose invaluable contributions made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Adult Responses to Children's Strong Emotions Scale (ARCSES), Avatar action control system (AACS), avatar display system (ADS), avatar interaction system (AIS), Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18), Institutional Review Board (IRB), Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Research Electronic Database Capture (REDCap), Virtual reality (VR).

Appendix A

Table A1.

Correlations Among All Study Variables of Interest and Post Intent to Use Evidence-Based Emotion Management Strategies.

Table A1.

Correlations Among All Study Variables of Interest and Post Intent to Use Evidence-Based Emotion Management Strategies.

| Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

| 1. ARCSES Post Total |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Pre-DERS total |

-.06 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Some high school |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. High school |

-.13 |

-.04 |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Some college/Associate's |

-.06 |

-.01 |

- |

-.22* |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Bachelor's Degree |

.13 |

-.01 |

- |

-.33** |

-.36** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Master's Degree |

-.03 |

-.01 |

- |

-.22* |

-.25* |

-.36** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Advanced/Doctoral degree |

.07 |

.08 |

- |

-.11 |

-.18 |

-.22* |

-.19 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. White |

-.05 |

-.07 |

- |

.18 |

.11 |

.02 |

-.18 |

-.15 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Black/African American |

-.00 |

-.03 |

- |

-.15 |

-.09 |

-.10 |

.17 |

.22* |

-.74** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. American Indian/Alaska Native |

.07 |

.08 |

- |

-.04 |

-.08 |

-.09 |

.11 |

.15 |

-.28** |

-.07 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Asian |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13. Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14. Bi/Multi-racial |

-.04 |

-.12 |

- |

.01 |

-.06 |

-.04 |

.22* |

-.17 |

-.13 |

-.07 |

-.10 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15. Other race |

.06 |

.16 |

- |

-.09 |

.03 |

.20 |

-.11 |

-.09 |

-.45** |

-.08 |

-.05 |

- |

- |

-.05 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16. Hispanic |

-.02 |

.01 |

- |

.09 |

.19 |

.07 |

-.11 |

-.34** |

.28** |

-.37** |

-.06 |

- |

- |

.21* |

-.01 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17. Non-Hispanic |

.10 |

-.03 |

- |

-.04 |

-.11 |

-.10 |

.06 |

.28** |

.08 |

-.04 |

.14 |

- |

- |

-.15 |

-.10 |

-.76** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18. Caribbean |

-.06 |

-.01 |

- |

-.05 |

-.08 |

-.10 |

-.08 |

.43** |

-.29** |

.42** |

-.05 |

- |

- |

-.08 |

-.04 |

-.28** |

-.09 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 19. Haitian |

-.08 |

-.01 |

- |

-.07 |

-.08 |

.05 |

.11 |

-.06 |

-.32** |

.43** |

-.03 |

- |

- |

-.02 |

-.03 |

-.33** |

-.06 |

-.02 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20. Other Ethnicity |

-.03 |

.07 |

- |

-.03 |

-.08 |

.08 |

.11 |

-.13 |

-.27* |

.18 |

-.07 |

- |

- |

-.12 |

.33** |

-.26* |

-.12 |

-.06 |

-.03 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21. Preferred Language |

.27* |

-.03 |

- |

.16 |

.15 |

.09 |

-.26* |

-.19 |

.13 |

-.26* |

-.07 |

- |

- |

.03 |

.20 |

.31** |

-.24* |

-.08 |

-.12 |

-.06 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 22. Age |

.29** |

-.18 |

- |

.11 |

.05 |

-.10 |

-.01 |

-.03 |

.08 |

-.06 |

-.06 |

- |

- |

.01 |

-.02 |

.06 |

-.02 |

.16 |

-.19 |

-.07 |

.16 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| 23. Educator Role |

.16 |

-.24* |

- |

.21* |

.00 |

.20 |

-.13 |

-.41** |

.10 |

-.05 |

-.06 |

- |

- |

-.13 |

-.00 |

.16 |

-.17 |

-.07 |

.09 |

-.06 |

.37** |

.39** |

- |

|

|

|

|

| 24. Allied Health Professional |

-.04 |

.13 |

- |

-.18 |

-.08 |

-.25* |

.22* |

.42** |

.04 |

.02 |

-.10 |

- |

- |

.19 |

-.11 |

-.12 |

.16 |

.11 |

-.07 |

-.11 |

-.31** |

-.27* |

-.83** |

- |

|

|

|

| 25. Medical Professional |

-.20 |

.18 |

- |

-.11 |

.09 |

.10 |

-.14 |

.04 |

-.20 |

.04 |

.25* |

- |

- |

-.07 |

.15 |

-.07 |

.02 |

-.05 |

-.04 |

.25* |

-.19 |

-.25* |

-.39** |

-.14 |

- |

|

|

| 26. Simulation Time |

.19 |

-.02 |

- |

.03 |

-.11 |

.16 |

-.03 |

-.10 |

-.07 |

.04 |

.20 |

- |

- |

.04 |

-.09 |

-.27* |

.22* |

.02 |

.25* |

-.06 |

.03 |

.21 |

.26* |

-.27* |

-.08 |

- |

|

| 27. VR Simulation Type |

.12 |

.07 |

- |

-.03 |

-.20 |

.15 |

.10 |

-.07 |

-.08 |

.03 |

.01 |

- |

- |

.08 |

.06 |

-.13 |

.19 |

-.14 |

.05 |

.01 |

-.06 |

-.03 |

.10 |

-.11 |

-.02 |

.19 |

- |

Table A2.

Correlations Among All Study Variables of Interest and Follow-up Actual Reported Use of Evidence-Based Emotion Management Strategies.

Table A2.

Correlations Among All Study Variables of Interest and Follow-up Actual Reported Use of Evidence-Based Emotion Management Strategies.

| Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

| 1. ARCSES One Month Follow-UpTotal |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. DERS Total |

-.12 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Some high school |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. High school |

.06 |

-.01 |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Some college/Associate's |

.15 |

.05 |

- |

-.22* |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Bachelor's Degree |

-.10 |

-.05 |

- |

-.33** |

-.36** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Master's Degree |

-.02 |

-.00 |

- |

-.23* |

-.26* |

-.39** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Advanced/Doctoral degree |

-.11 |

.04 |

- |

-.10 |

-.14 |

-.20 |

-.17 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. White |

.09 |

-.02 |

- |

.19 |

.07 |

-.01 |

-.20 |

-.05 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Black/African American |

-.09 |

-.07 |

- |

-.15 |

-.08 |

-.09 |

.19 |

.19 |

-.75** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. American Indian/Alaska Native |

-.11 |

.06 |

- |

-.03 |

-.05 |

-.07 |

.20 |

-.08 |

-.20 |

-.05 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Asian |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13. Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14. Bi/Multi-racial |

-.01 |

-.14 |

- |

.00 |

-.05 |

-.06 |

.21 |

-.16 |

-.14 |

-.07 |

-.10 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15. Other race |

.03 |

.17 |

- |

-.09 |

.03 |

.20 |

-.13 |

-.09 |

-.48** |

-.09 |

-.04 |

- |

- |

-.06 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16. Hispanic |

.13 |

-.04 |

- |

.09 |

.23* |

.04 |

-.14 |

-.33** |

.33** |

-.47** |

.10 |

- |

- |

.19 |

-.03 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17. Non-Hispanic |

-.02 |

.02 |

- |

-.02 |

-.16 |

-.06 |

.12 |

.20 |

.08 |

.01 |

-.06 |

- |

- |

-.09 |

-.08 |

-.73** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18. Caribbean |

-.24* |

-.01 |

- |

-.05 |

-.08 |

-.11 |

-.10 |

.55** |

-.31** |

.45** |

-.05 |

- |

- |

-.10 |

-.05 |

-.32** |

-.07 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 19. Haitian |

-.05 |

-.01 |

- |

-.07 |

-.08 |

.05 |

.11 |

-.05 |

-.34** |

.45** |

-.02 |

- |

- |

-.03 |

-.04 |

-.36** |

-.05 |

-.03 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20. Other Ethnicity |

.02 |

.08 |

- |

-.04 |

-.07 |

.07 |

.10 |

-.12 |

-.29** |

.19 |

-.07 |

- |

- |

-.15 |

.32** |

-.30** |

-.08 |

-.07 |

-.03 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21. Preferred Language |

.49** |

-.08 |

- |

.15 |

.14 |

.10 |

-.27* |

-.17 |

.11 |

-.26* |

-.05 |

- |

- |

.01 |

.21 |

.30** |

-.23* |

-.09 |

-.12 |

-.07 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 22. Age |

.08 |

-.14 |

- |

.08 |

.06 |

-.15 |

-.03 |

.12 |

.03 |

-.02 |

.00 |

- |

- |

-.01 |

-.03 |

.03 |

.03 |

.15 |

-.20 |

-.09 |

.17 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| 23. Educator Role |

.23* |

-.24* |

- |

.21 |

-.06 |

.18 |

-.16 |

-.29** |

.03 |

-.00 |

.09 |

- |

- |

-.17 |

-.01 |

.13 |

-.12 |

-.09 |

.09 |

-.08 |

.36** |

.35** |

- |

|

|

|

|

| 24. Allied Health Professional |

-.15 |

.12 |

- |

-.18 |

-.04 |

-.24* |

.25* |

.37** |

.07 |

-.06 |

-.08 |

- |

- |

.22 |

-.11 |

-.13 |

.18 |

.13 |

-.07 |

-.11 |

-.31** |

-.23* |

-.85** |

- |

|

|

|

| 25. Medical Professional |

-.21 |

.18 |

- |

-.11 |

.13 |

.14 |

-.14 |

-.09 |

-.13 |

.07 |

-.04 |

- |

- |

-.06 |

.18 |

-.01 |

-.09 |

-.05 |

-.04 |

.29** |

-.19 |

-.25* |

-.37** |

-.12 |

- |

|

|

| 26. Simulation Time |

-.02 |

-.00 |

- |

-.00 |

-.14 |

.18 |

.03 |

-.15 |

-.09 |

.11 |

.05 |

- |

- |

.10 |

-.08 |

-.24* |

.13 |

.05 |

.30** |

-.03 |

.03 |

.19 |

.29** |

-.23* |

-.20 |

- |

|

| 27. VR Simulation Type |

.05 |

.06 |

- |

-.04 |

-.19 |

.16 |

.07 |

-.08 |

-.05 |

.04 |

-.13 |

- |

- |

.06 |

.05 |

-.15 |

.25* |

-.16 |

.04 |

-.01 |

-.05 |

-.04 |

.12 |

-.09 |

-.10 |

.25* |

- |

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. October 19, 2021. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/.

- Davidson, B.C., Schmidt, E., Mallar, C., Mahmoud, F., Rothenberg, W., Hernandez, J., Berkovits, M. Jent, J.F., Delamater, A., & Natale, R. (2021). Risk and Resilience of Well-being in Parents of Young Children in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11, 305-313. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K. M., Drawve, G., & Harris, C. (2020). Facing new fears during the COVID-19 pandemic: The State of America’s mental health. Journal of anxiety disorders, 75, 102291. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, H. (2023, April 1). Providers predict longer wait times for mental health services. Here’s who it impacts most. Monitor on Psychology, 54(3). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/04/mental-health-services-wait-times.

- Meek, S. E., & Gilliam, W. S. (2016). Expulsion and suspension in early education as matters of social justice and health equity. NAM Perspectives.

- Schleider, J. L., Dobias, M. L., Sung, J. Y., & Mullarkey, M. C. (2019). Future Directions in Single-Session Youth Mental Health Interventions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(2), 264–278. [CrossRef]

- Allcoat D., & von Mühlenen A. (2018). Learning in virtual reality: Effects on performance, emotion and engagement. Research in Learning Technology, 26. [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., Gutworth, M. B., & Jacobs, R. R. (2021). A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106808. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R., Rybak, T., Meisman, A., Whitehead, M., Rosen, B., Crosby, L. E., ... & Real, F. J. (2021). A virtual reality resident training curriculum on behavioral health anticipatory guidance: development and usability study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 4(2), e29518. [CrossRef]

- Real, F. J., DeBlasio, D., Beck, A. F., Ollberding, N. J., Davis, D., Cruse, B., Samaan, Z., McLinden, D., & Klein, M. D. (2017). A Virtual Reality Curriculum for Pediatric Residents Decreases Rates of Influenza Vaccine Refusal. Academic pediatrics, 17(4), 431–435. [CrossRef]

- Real, F. J., Whitehead, M., Ollberding, N. J., Rosen, B. L., Meisman, A., Crosby, L. E., Klein, M. D., & Herbst, R. (2023). A Virtual Reality Curriculum to Enhance Residents' Behavioral Health Anticipatory Guidance Skills: A Pilot Trial. Academic pediatrics, 23(1), 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S., Ang, E., Ng, E. D., Yap, J., Lau, L. S. T., & Chui, C. K. (2020). Communication skills training using virtual reality: A descriptive qualitative study. Nurse education today, 94, 104592. [CrossRef]

- Farra, S., Miller, E., Timm, N., & Schafer, J. (2013). Improved training for disasters using 3-D virtual reality simulation. Western journal of nursing research, 35(5), 655-671. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, A. (2020). Assessing the use of immersive environments for preparing teachers to address challenging student behaviors. Thesis. [CrossRef]

- Passig, D. , Noyman, T. (2002). Training Kindergarten Teachers with Virtual Reality. In: Watson, D., Andersen, J. (eds) Networking the Learner. WCCE 2001. IFIP — The International Federation for Information Processing, vol 89. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Richter, E., Klickmann, T., & Richter, D. (2023). Comparing video and virtual reality as tools for fostering interest and self-efficacy in classroom management: Results of a pre-registered experiment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(2), 467–488. https://doi-org.access.library.miami.edu/10.1111/bjet.13254.

- Emmelkamp, P. M., & Meyerbröker, K. (2021). Virtual reality therapy in mental health. Annual review of clinical psychology, 17(1), 495-519. [CrossRef]

- Do, T. D., Zelenty, S., Gonzalez-Franco, M., & McMahan, R. P. (2023). Valid: a perceptually validated virtual avatar library for inclusion and diversity. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 4, 1248915. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Garcia, D., & Montoya, H. (2018). Lost in translation: Training issues for bilingual students in health service psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(3), 142–148. [CrossRef]

- US. Census. (2025). Languages spoken at home. Retrieved 4/18/25. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/language/.

- Ibrahim, S. , Lok, J., Mitchell, M., Stoiljkovic, B., Tarulli, N., & Hubley, P. (2023). Equity, diversity and inclusion in clinical simulation healthcare education and training: An integrative review. International Journal of Healthcare Simulation. 10.54531/brqt3477.

- Katz, D., Hyers, B., Patten, E., Sarte, D., Loo, M., & Burnett, G. W. (2024). Relationship between demographic and social variables and performance in virtual reality among healthcare personnel: an observational study. BMC medical education, 24(1), 227. [CrossRef]

- Sun, A. , Tao, Y., Shyu, M. L., Chen, S. C., Blizzard, A., Rothenberg, W. A.,... & Jent, J. F. (2021, August). Multimodal data integration for interactive and realistic avatar simulation in augmented reality. In 2021 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI) (pp. 362-369). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jent, J. F., Rothenberg, W. A., Peskin, A., Acosta, J., Weinstein, A., Concepcion, R., ... & Garcia, D. (2023). An 18-week model of Parent–Child Interaction Therapy: clinical approaches, treatment formats, and predictors of success for predominantly minoritized families. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1233683. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S., & Mychailyszyn, M. (2021). A review of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT): Applications for youth anxiety. Children and Youth Services Review, 125, 105986. [CrossRef]

- Comer, J.S. , del Busto, C., Dick, A.S., Furr, J.M., Puliafico, A.C. (2018). Adapting PCIT to Treat Anxiety in Young Children: The PCIT CALM Program. In: Niec, L. (eds) Handbook of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics, 42(2), 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R., Abell, B., Webb, H. J., Avdagic, E., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2017). Parent-child interaction therapy: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 140(3). [CrossRef]

- Eyberg, S. M., & Funderburk, B. W. (2011). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy protocol. PCIT International.

- Victor, S.E., Klonsky, E.D. Validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18) in Five Samples. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 38, 582–589 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Spinrad, T. L., Stifter, C. A., Donelan-McCall, N., & Turner, L. (2004). Mothers’ regulation strategies in response to toddlers’ affect: Links to later emotion self-regulation. Social Development, 13(1), 40-55. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A. Rapid qualitative analysis: Updates/developments. VA Health Services Research & Development Cyberseminar. 2020.

- Knowles, M. S. , Holton III, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2014). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge.

- Eijlers, R., Utens, E. M., Staals, L. M., de Nijs, P. F., Berghmans, J. M., Wijnen, R. M., ... & Legerstee, J. S. (2019). Systematic review and meta-analysis of virtual reality in pediatrics: effects on pain and anxiety. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 129(5), 1344-1353. [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, J.M., Pike, C.K., Hogan, T.P. et al. The Engagement Problem: a Review of Engagement with Digital Mental Health Interventions and Recommendations for a Path Forward. Curr Treat Options Psych 10, 119–135 (2023). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).