1. Concept of “We Are What We Eat”

The concept “We Are What We Eat” has evolved into a powerful framework for understanding the intricate connections between human health, dietary patterns, and the wider sociocultural and environmental context. Over time, what began as a philosophical observation it now highlights that food choices and specific nutrients, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly omega-3 (ω-3) and omega-6 (ω-6), play critical roles in shaping not only individual health and well-being but also collective societal and ecological outcomes.

ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs are widely recognized for their roles in supporting brain function and cardiovascular (CV) health, these PUFAs are among the most commonly used nutritional supplements, with numerous studies validating their efficacy [

1,

2]. Notably, their physiological importance is reinforced by the fact that mammals are unable to synthesize these fatty acids (FA) endogenously, making their regular dietary intake essential for maintaining health and preventing diseases.

Although much is known about ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids, existing scientific literature tends to focus either on specific health benefits or provides broad overviews of their roles in human physiology, creating gaps in integrating nutritional, molecular, and therapeutic insights. Therefore, this review aims to provide a more comprehensive and detailed overview of the current knowledge on ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs, covering their nutritional relevance, molecular structures, primary dietary sources, established and emerging health benefits, as well as other critical aspects associated with their biological functions and therapeutic potential.

Despite their popularity, nutritional supplements like food based ω-3 and ω-6, are subject to quality, safety and efficacy requirements that differ significantly from those applied to medicines, being regulated by different entities. This means that the research and investment on robust assays to ensure the safety, quality and efficacy behind food supplements is much scarcer than those on medicines. With the growth of the food supplementation market, it becomes increasingly urgent to implement standardized procedures to safeguard consumers. Moreover, the adverse effects and interactions with other substances, such as prescription medicines, are not well known and understood by consumers, posing additional risks.

This review, gathering information about the biological effects of the ω-3 and ω-6 and the current state of knowledge on existing supplements and their claimed outcomes, aims to spread knowledge about their health and therapeutic potential and awareness on the importance of having standardized procedures to ensure the safety, quality and efficacy of these food supplements. Pharmacists and vendors have a critical task in this process, by being well-informed about these topics and able to properly advise and alert the consumer ensuring that the product has the expected health benefits and that the consumption is made consciously, minimizing any risks. This information should also be used by the manufacturers, which bear responsibility for transparent communication and accurate information.

To guide the analysis, several key questions frame this review: “How much ω-3 and ω-6 should be consumed?”, “Is supplementation necessary or can diet provide the amounts needed?”, “What are their mechanisms of action?”, “What are the main health benefits of omegas?”, “Are there any recently discovered health benefits associated with omegas?”, “What risks and side effects are associated with misuse and how can they be prevented?”, “Are there any interactions with prescribed medicines? If so, which ones?”. Accordingly, this review addresses the effects of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs on hypertriglyceridemia, CV health, on brain function and neurodegenerative diseases, on the inflammation process and on cancer prevention, as well as discussing the main reported adverse effects.

The main databases used for this review were Pubmed and Pubchem. The scientific articles used were all in English, dated between 2010 and 2025 and the keywords used for the search were: ”Omega”, “Omega 3”, “Omega 6”, “Omega fatty acids”, “Health benefits”, “Cardiovascular”, “Neurodegenerative”, “brain function”, “Depression”, “Depressive disorder”, “Alzheimer’s disease”, “Parkinson’s disease”, “Inflammation”, “anti- inflammatory”, “cancer”. When searched with only “omega 3” as keyword there were 27.197 articles available, with “omega 6” there were 25.301. To further enhance the search, a combination of different keywords was used. Conference proceedings and data from other language besides English were excluded.

2. Nutritional Aspects of Diet

2.1. Macronutrients and Micronutrients

Macronutrients, such as fats, proteins and carbohydrates, are required by the body in larger quantities, whereas micronutrients are needed in smaller amounts, such as vit-amins and minerals. Generally, the diet can provide both macro and micronutrients at the same time, for example, fish and plant oils, seeds and dry fruits are the main dietary sources of ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids (FA). In addition, these same foods also contribute valuable micronutrients, such as vitamins A and D from fish oils, some minerals like zinc, iron, and manganese from plant oils, seeds and dry fruits [

3,

4]. However, despite the variety of dietary sources, deficiencies in certain macro- or micronutrients can still occur due to inadequate intake, disease and other conditions, leading to deficiencies or increased physiological demands. In such cases, supplementation be-comes an important strategy to help meet nutritional requirements and prevent associated health problems.

2.2. Historical Aspects and Impacts of Diet

The diet plays a significant role in both physical and physiological health. Having a balanced diet throughout life improves one’s health and help the body and brain to better develop. Having a balanced diet with all the macro and micronutrients in good quantities is essential. Omega FA, for example, play a big role in the development of brain function and in the prevention of cardiovascular incidents, others play a role in maintaining the good functioning of other parts of the body, such as the immune system or the metabolism, for example [

2,

5].

Throughout history, the diet patterns were always connected to the culture, where countries that are situated closer to the sea, like Portugal, have more fish in their diet. This fact has an impact on the population’s diet and on what nutrients they ingest, throughout life. The financial situation of a country also affects the way people eat. In richer countries, people tend to overeat more, which leads to a more overweight population, where in poorer countries, that does not happen as much [

6,

7].

Nowadays, with the industrialization of the food industry, processed foods and bad diet habits are more common than ever, playing a big role in the development of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, high cholesterol levels, obesity and increasing the risk of cardiovascular and heart diseases. Besides that, social media is more present than ever, leading to people comparing themselves with what they see online. This puts a lot of pressure on the idea of having to have a perfect body to fit in and focus on appearance-based eating rather than health-driven nutrition. Consequently, this might lead to more stress, anxiety and depression, especially in the younger population. Having a healthy and nutritious diet not only contributes to a healthier body, but also to a healthier mind [

2,

5,

6,

7].

2.3. Dietary Guidelines and Nutritional Recommendations

Throughout life, the needs in terms of nutrients and energy intake varies. According to WHO, for an adult, a healthy diet must include fruits, vegetables, legumes (e.g. lentils and beans), nuts and whole grains (e.g. unprocessed maize, oats, wheat and brown rice); daily, an adult should eat 400 grams of fruits and vegetables, excluding potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava and other starchy roots; the intake of free sugars should be equivalent to less than 10% (ideally 5%) of the total energy intake which, for an average healthy adult who consumes 2000 calories a day, is equivalent to 50 grams of free sugars; the intake of fats should be equivalent to less than 30% of the total energy intake, unsaturated fats (found in fish, avocado, nuts and olive oil, for example), such as the ω-3 and ω-6, are preferable over saturated fats (found in fatty meat, butter, palm and coconut oil, for example), that should have a maximum intake of 10% of total energy, and trans-fats (found in baked and fried foods and pre-packaged snacks and foods, for example), that should have a maximum intake of 1% of total energy; salt consumption should be less than 5 grams per day [

5].

During childhood, optimal nutrition is key to ensure a healthy growth and cognitive development. WHO recommends to, exclusively, breastfeed infants up to 6 months old, after that, breastfeeding should be complemented with adequate, safe and nutrient-dense foods [

5].

In order to achieve and maintain a healthy diet, WHO also provides some practical advices, such as to include a portion of vegetables in every meal, eat fruits and vegetables raw as a snack, replacing saturated and trans-fats with unsaturated fats, steam and boil instead of frying, using healthier oils to cook, such as soybean and sunflower oils, not having salt or high sodium sauces on the table, limiting the consumption of salty snacks, checking the quantity of salt when buying groceries and limiting the consumption of foods and drinks with high amounts of sugars [

5].

3. Omega Fatty Acids

ω-3 and ω-6 are a class of FA, FA can be monounsaturated (MUFAs) or PUFAs, the difference being the number of double bonds in the carbon chain, where MUFAs have only one double bond and PUFAs have more than one. Between ω-3 and ω-6, the difference resides on the placement of the first double bond, ω-3 are FA with a double bond between the third and fourth carbon atoms from the methyl end of the carbon chain and ω-6 are the ones with a double bond between the sixth and seventh carbon atom from the methyl end of the carbon chain. The omegas can be further divided into four different groups, depending on the size of the carbon chain. If it has a carbon chain of 1 to 6 carbon atoms, it is a Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA), also known as Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) [

8], if it has seven to 12 carbon atoms , it is a Medium-Chain Fatty Acid (MCFA) [

8], if it has 14 to 18 carbon atoms it is a Long-Chain Fatty Acid (LCFA) [

9] and if it has more than 20 carbon atoms it is a Very Long-Chain Fatty Acid (VLCFA) [

10].

The main ω-3 PUFAs being focused on this paper are ɑ-linoleic acid (C

18H

30O

2) (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (C

20H

30O

2) (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (C

22H

32O

2) (DHA) and the main ω-6 PUFAs are linoleic acid (C

18H

32O

2) (LA), the predecessor of arachidonic acid (C

20H

32O

2) (ARA) [

9,

11].

ALA and LA are classified as essential FA because they can only be acquired from dietary sources and cannot be synthesized endogenously. Even though the other PUFAs (EPA, DHA and ARA) can be synthesized endogenously starting from ALA and LA, they are essential to have in the daily diet. The main dietary sources of the omegas are, for example, fish (e.g. salmon, tuna or sardines), dry fruits (e.g. nuts or cashew) and seeds (e.g. chia seeds) [

9,

12,

13,

14].

The ω-3 FA are involved in the development of brain function and preventing neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and dementia and in preventing cancer [

15,

16]. ω- 3 and ω-6 also have an impact on blood cholesterol levels, helping to prevent cardiovascular problems and on the inflammatory process, helping the body give a more adequate response when needed [

2,

9,

14,

15].

For the omegas to have the expected health benefits, the ratio between the ingestion of ω-6 and ω-3 is key. Nowadays, many diets have a bigger intake of ω-6 compared to a much lower intake of ω-3. A ratio of 4-1 to 1-1 of ω-6 to ω-3 is considered the most balanced and to have health benefits. A variation on this ratio can be more effective for different diseases, for example, a ratio of 4/1 was associated with a bigger prevention of cardiovascular events, whereas a 2.5/1 ratio reduced rectal cell proliferation in patients with colorectal cancer [

9,

17].

4. Main Dietary Sources of ω-3 and ω-6

As mentioned before, ω-3 and ω-6, more specifically, ALA and LA are considered essential FA because humans cannot produce it and, even though the other omegas that are being mentioned in this review can be synthesized through metabolism pathways in the human organism starting from ALA and LA, their production is limited because they use the same enzymes. With that in mind, it is necessary to have good and healthy amounts of all omegas from the diet.

A study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2003 to 2008, based on the American population, concluded that the population consumed, from food sources, an average of 0.17 g/day of ω-3 PUFAs, more specifically, EPA and DHA, when the American Heart Association recommends consuming 0.5 g/day [

18]. Nowadays, the National Academy of Medicine recommends a daily intake of 1.6 g/day and 1.1 g/day of ALA for men and women, respectively [

19]. From the survey, it was possible to determine that fish is the main source of EPA and DHA in the population since the ones that consumed a deficient amount of ω-3 were the ones that consumed less fish in their diet, contrary to the population with the highest intake where fish was the main ω-3 source [

18]. One reason for fish to be such a great source of EPA and DHA is the fact that they consume algae. Algae is a great source of EPA and DHA [

20].

ω-3 PUFAs can be found in some fish, nuts, seeds and plant oils, more specifically, EPA can be found in great amounts in herring, wild sardine and pollock roe, being rather rare its presence in plants; DHA can be found in flying fish, herring, pollock, salmon roe, and jackal berry; ALA, on the other hand, is more common in plants and seeds than in fish, being found in flaxseed, chia, and canola oil. These are not all the sources of ω-3 but are some of the more noteworthy ones [

4,

9,

13,

14].

One important point to consider when trying to consume enough ω-3 is that, since fish are the main source of EPA and DHA, as previously mentioned, frequent consumption of fish can expose the human body to high levels of methylmercury, found in many fish species because of their environment. Methylmercury has a neurotoxic effect, making it very important to have alternate sources of these nutrients in the daily diet. This problem can spread to food supplements based on extracts of fish oils, where methylmercury can also be present [

9]. ω-6 PUFAs can be found in many oils and seeds, such as corn sunflower, soybean, canola, safflower and flaxseed oils, chia, walnuts, hazelnuts and almonds. Smaller amounts of LA can also be found in some vegetables and fish and ARA can be found mostly in meat, eggs and dairy products but also, in some fish, like salmon, herring, sardine, trout and cod but in smaller amounts [

12,

21,

22,

23]. A more detailed list of some of the food sources and the amount of each omega fatty acid they contain can be found in

Table 1.

5. Metabolism and Bioavailability of ω-3 and ω-6

In plants and animal-based food, ω-3 and ω-6 are mostly found in the form of triacylglycerols (TAG), phospholipids (PL), Diacylglycerols (DAG) and Cholesterol Esters (CL) [

22] but they may also appear as free fatty acids (FFA) and ethyl esters (EE) [

15], being PLs the most bioavailable because of their aliphatic characteristics. When ingested, these PUFAs are mostly assimilated into TAG and their digestion starts in the stomach, where gastric lipases break down TAGs into DAG and FFA. The complete digestion occurs then in the intestine lumen with the aid of bile salt and pancreatic lipases. ω-3 FAs in the form of EEs, TAGs or PLs have shown to be better digested and absorbed when the fat content of the food is high because it enhances the activity of the pancreatic enzymes [

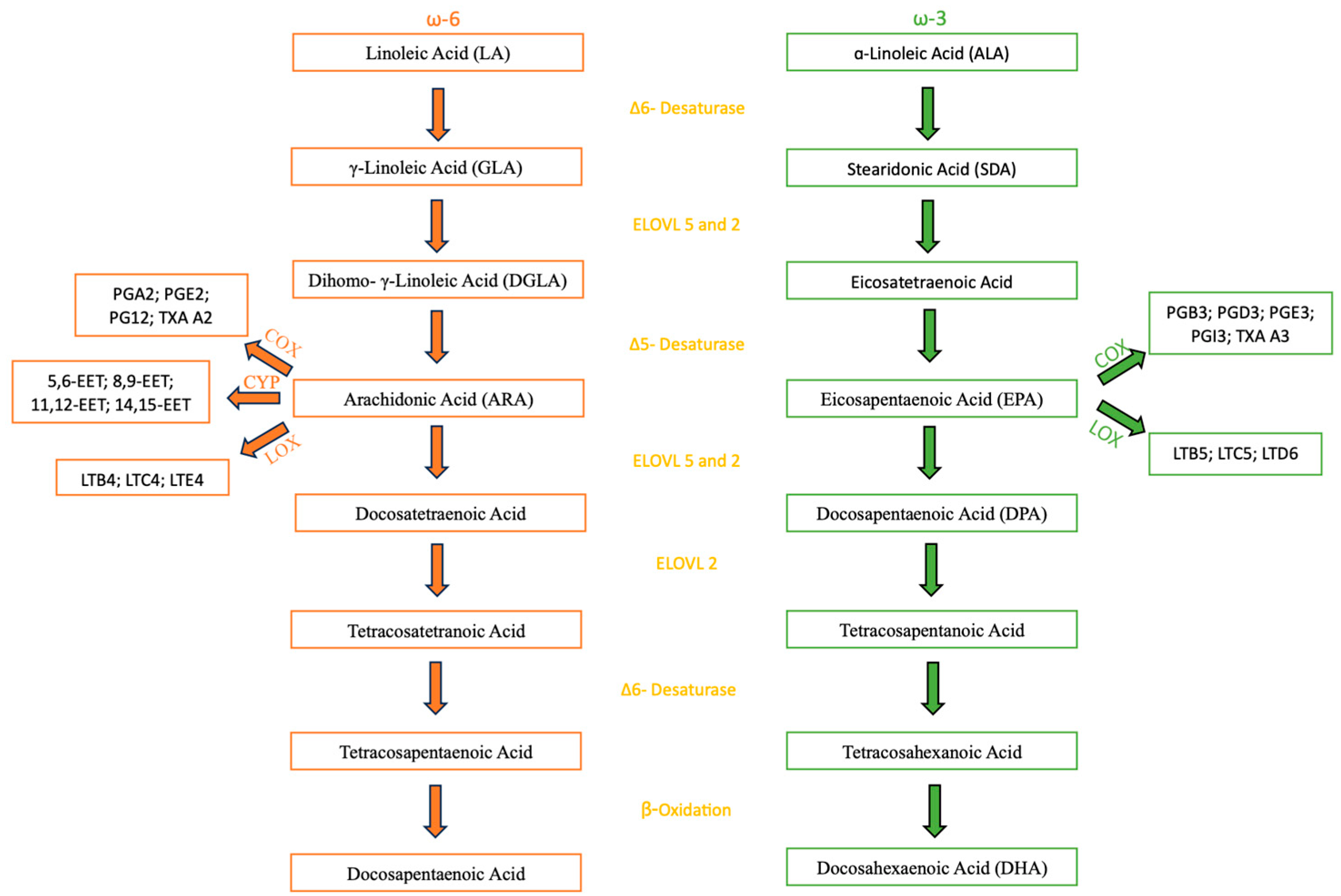

15]. The release of the FAs allows absorption and transportation into the bloodstream. After that, the FAs can either undergo esterification into cellular lipids as PL, TAG or CE; a beta-oxidation to provide energy; go through the metabolic pathway described further and illustrated on

Figure 1 to form the other ω-3 and ω-6 FAs [

22]. The latter occurs mostly in the liver, occurring in other tissues but in an insignificant amount [

23]. As for the biosynthesis in the human body, both ω-3 and ω-6 metabolism share the same enzymes through their metabolic pathways, a group of elongases and desaturases situated mostly in the liver, starting from ALA and LA, respectively. The first step in the metabolic pathway is catalyzed by the Δ6-fatty acid desaturase (FADS) that adds a double bond at the sixth carbon position from the carboxyl group of ALA and LA, resulting in the formation of Stearidonic Acid (SDA) and γ-Linoleic Acid (GLA), respectively. This first step is of special importance in the metabolic pathway because the Δ6-FADS is a rate-limiting step in humans, meaning it is the slowest one, therefore dictating the overall reaction rate. The second step is an elongation that leads to the synthesis of eicosatetraenoic Acid (ETA) and Dihomo-eta-Linoleic Acid (DGLA). After that, Δ5- FADS adds a new double bond to the fifth carbon from the carboxyl group, resulting in the formation of ARA and EPA. From there, both metabolic pathways still undergo some more steps, being the most important to mention in the ω-3 pathway, that ends up in the formation of DHA, one of the PUFAs being studied in this review. Both metabolic pathways are represented on

Figure 1 [

22].

The highest rate of conversion from ALA to EPA and DHA in the hepatic cells occurs when the ratio of ALA and LA is 1:1. The conversion rates recorded were 17% and 0,7% for EPA and DHA respectively. This data highlights the importance of having DHA supplementation or, at least, to have incorporated into the daily diet food containing DHA because the conversion rate from ALA is low [

26]. As mentioned, the ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs share the same enzymes through their metabolic pathways and, because of that, the rate of conversion of ALA and LA into EPA and ARA, respectively, depends on the availability of the substrate. Nowadays, many diets have much higher amounts of ω-6 than ω-3, it is expected that LA, being the dominant substrate, becomes more converted into ARA than ALA into EPA and DHA, thus explaining why, usually, the levels of ω-6 PUFAs are higher in the organism. This could explain the observed low rates of conversion of ALA into EPA and DHA [

2]. A report made by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) pointed to the fact that conversion rates of both ω-3 and ω-6 can also be affected by other factors. The Δ5-FADS appears to have a lower rate of activity in people that are diabetic, and the Δ6-FADS also appears to have a lower rate of activity when insulin levels are low or there is a deficiency of proteins and some vitamins like iron, zinc, copper and magnesium. Lower rate of activity of these enzymes results in lower rates of conversion of ALA and LA into EPA and ARA, respectively, since both enzymes have a present role in the metabolic pathways. This, once again, reflects on the importance of having implemented supplementation of these nutrients into the diet, to get the health benefits from them [

27].

When needed, ω-3 and ω-6 FAs can be used to form different types of oxylipins, by oxygenase enzymes, such as lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and maresins. Oxylipins are bioactive signaling molecules with different functions such as pro/anti-inflammatory and immune response regulation. These reactions are led by specific enzymes, cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX) and cytochrome P450 (CYP) [

28].

ω-3 FAs concentration can be measured in plasma, serum, blood cells and lymph. When trying to evaluate the content of FAs in the diet in a medium-long term, plasma is the best indicator, when evaluating a long-term supply, blood cells are the best indicator. There are, also, other ways to calculate the bioavailability of ω-3, the most important being the ω-3 index and maximum concentration (Cmax). The ω-3 index is the proportion of the sum of EPA and DHA content in the total FA content in the erythrocyte membrane, expressed as a percentage. This is a good indicator of the bioavailability for the past 80-120 days due to the long lifetime and the abundance of these cells. The Cmax of EPA and DHA in the plasma can be determined five to nine hours after administration, while the persistent levels can be achieved after two weeks of daily supplementation [

9].

ω-3 FAs are present in many tissues and organs, such as the heart, nervous tissue and the retina. It is also present in the cerebrospinal fluid. A way to improve its passage through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) up to 10 times is by using a carrier particle. In the case of DHA, the carrier particle used is 1-lyso,2-docosahexaenoyl-glycerophosphocholine (LysoPC-DHA). It is a brain specific particle that improves the passage through the BBB but not to other tissues or organs [

9].

6. Main Health Benefits of ω-3 and ω-6

6.1. Effects on Hypertrigliceridemia

To the best of knowledge, in Portugal, there is only one medicine based on ω-3 PUFAs (EPA+DHA) prescribed for hypertriglyceridemia. The mechanism behind this effect is still not fully understood but studies point towards it being due to the suppression of the lipogenic gene expression, the increase of ꞵ-oxidation of FA, the increase of the expression of lipoprotein-lipase (LPL) and the influence on total body lipid accretion [

29].

The suppression of lipogenic gene expression is achieved by decreasing the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP). SREBPs are a membrane bound enzyme that, when cleaved, transcribe enzymes that are involved in the production of cholesterol, LDL and FAs. A diet rich in ω-3 PUFAs decrease the activation of the SREBP 1c due to negative feedback, leading to a decrease in the production of cholesterol through the enzymes that it regulates (farnesyl diphosphate synthase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase) [

29].

To produce energy from FAs, the body uses ꞵ-oxidation. ω-3 PUFAs can enhance the rate of ꞵ-oxidation, primarily through their regulatory effects on carnitine acyltransferase (CAT1) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). CAT1 acts on facilitating the transportation of FAs into the mitochondria. Inside it, the FAs are converted into acyl-CoA, which serves as a precursor to acetyl-CoA, a central molecule in ATP production through various metabolic pathways. Additionally, EPA indirectly stimulates ꞵ-oxidation by inhibiting ACC, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing malonyl-CoA, a potent inhibitor of CAT1. Furthermore, ω-3 PUFAs have been shown to reduce CAT1’s sensitivity to malonyl-CoA, further promoting FA utilization for energy production [

29].

LPL is an enzyme responsible for the removal of triacylglycerol components from chylomicrons, LDL and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) in the blood. ω-3 PUFAs have been shown to increase the activity of LPL, reducing the levels of LDL, VLDL and chylomicron size [

29].

ω-3 PUFAs can also influence total body lipid accretion. Studies have demonstrated that the use of ω-3 PUFAs for more than 6 weeks can increase the body’s metabolic rate and decrease total body fat. Participants in the studies have shown an increase in lean body mass, a reduction in adipose tissue, elevated resting metabolic rate, greater energy expenditure during physical activity and enhanced ꞵ-oxidation, both while resting and physical activity [

30,

31]. These facts occur because ω-3 PUFAs can act as a ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). PPARs can then regulate both ꞵ-oxidation and glucose metabolism and change the basal metabolism of the cell [

29].

Through all these four mechanisms, ω-3 PUFAs have support its efficacy in the reduction of the level of triglycerides. Therefore, daily intake of ω-3 PUFAs, either through the diet or with supplementation, might be advisable for patients with diagnosed hypertriglyceridemia and even healthy people as a way of prevention.

6.2. Effects on Cardiovascular Health

Nowadays, the effects of ω-3 in cardiovascular health are still a subject of debate. Throughout the many trials and the meta-analysis available on the subject, the opinions are not unanimous and, while the cardioprotective effects of the ω-3 are noticeable in most studies, others do not show the same results.

One of the first landmark trials for ω-3 supplementation was the GISSI-P, a study with approximately 11 000 subjects and almost four years of follow up that showed that a supplementation of 1g/day of ω-3 (EPA + DHA) decreased the risk of death, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke in patients with recent MI (<3 months). However, many subsequent studies did not achieve the same results [

32].

More recently, in 2018, three large trials were released but also with divergent conclusions. The trials were called ASCEND, VITAL and REDUCE-IT. The ASCEND trail included 15 480 patients and had a follow up for 7.4 years. It used 1 g/day of EPA + DHA supplementation as the primary prevention in patients with diabetes but found no reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. Through the study was found, however, an 18% relative risk reduction in vascular death, defined as death from coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke or other vascular causes [

33].

The VITAL trial included 25 871 subjects and had a median follow up of 5.3 years. It used 2000 IU/ day of Vitamin D and 1 g/day of EPA + DHA supplementation for the primary prevention of CVD and cancer. Like the ASCEND trial, the VITAL trial found no significant difference between the intervention and the placebo groups in risk reduction but found a significant reduction in total MI. It also showed that patients that consumed less than 1.5 fish meals per week and then had ω-3 supplementation had a significant reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and risk of MI by 19% and 40%, respectively, which points to the importance of having a threshold level of ω-3 to have the therapeutic effects [

34].

The REDUCE-IT trial included 8 179 patients with established CVD or diabetes receiving statin therapy. The patients were followed for a median of 4.9 years. It used 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl, a highly purified EPA formulation. The primary endpoint of this trial was CVD death, non-fatal stroke, CV revascularization and unstable angina and a reduction of 25% was observed in the treatment group, as well as a reduction of 26% on the secondary endpoint (MACE). In the USA population there was a significant relative risk reduction of 30% and a 2.6% absolute risk reduction in all-cause mortality. While the other populations included in the trial also showed significant reductions in the primary and key secondary endpoints, it was more noticeable in the USA [

35].

In the last years, there were some noteworthy meta-analyses published about this topic which, like the previously mentioned trials, highlighted inconsistent results. One in particular is the meta-analysis by Bernasconi et al. [

36], where ω-3 supplementation was associated with a risk reduction of MI (relative risk (RR) 0,87), CHD events (RR 0,90), fatal MI (RR 0,65), CHD mortality (RR 0,91), and, not so significant but present in CVD events (RR 0,95). Important to mention that the risk reduction of MI and CVD events seems to be dose dependent. This meta-analysis included a total of 40 studies and examined, not only the effects on the risk reduction of various outcomes, but also the level of heterogeneity for each result, this information is summarized in

Table 2 [

36].

Overall, this meta-analysis concluded that ω-3 supplementation, despite having some trials that do not show results in reducing risk in many outcomes, most of the studies support that ω-3 supplementation is effective, as previously discussed [

36].

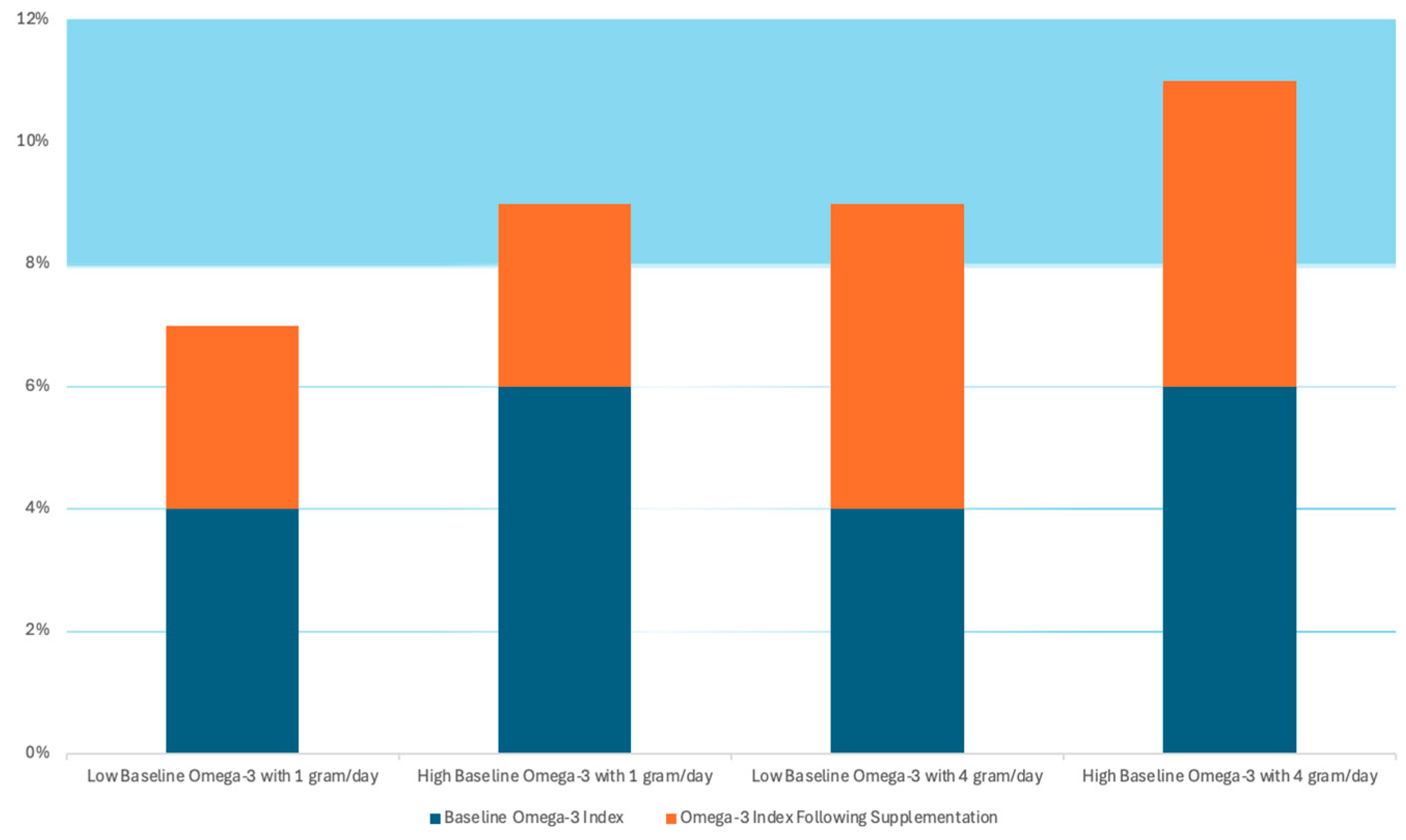

As mentioned, in certain outcomes (CVD events and MI), the benefits of the ω-3 appear to be dose-dependent, such can explain why, in studies like GISSI-P, where the subjects were from Italy, a country where fish is very much present in the daily diet, resulting in the presence of a threshold level of ω-3 and contributing to reaching a therapeutic level of ω-3 with lower dose supplementation (1 g/day), where other studies showed better results with higher dose supplementation (4 g/day). This idea is well demonstrated in a hypothetical representation present in

Figure 2 [

32]. In this Figure, the blue columns represent the baseline levels of ω-3, and the orange columns represent the supplementation levels. The study suggests that an ω-3 index >8% is necessary to predict a lower CV risk and it can, also, potentially reduce the risk of fatal CHD by approximately 35% [

32].

The effect of ω-3 has also been studied in heart failure (HF). GISSI-HF was a trial that included nearly 7 000 HF patients (91% with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)) with a median follow-up of 3.9 years. It used 1 g/day of ω-3 supplementation against placebo and found a number needed to treat (NNT) of 56 to prevent one death or NNT of 44 to avoid one death or hospital admission for CVD reasons. These results lead the American Heart Association (AHA) to provide a class IIa indication that ω-3 supplementation is reasonable for the treatment of patients with HFrEF [

32].

In late 2020, two more studies about the effects of ω-3 supplementation on CV health, OMEMI and STRENGTH, found no CV benefits on high-risk patients. Even though these trials add to the confusion around the benefits of ω-3 supplementation on CV diseases, they did not cancel out the findings of previous trials and meta-analysis that concluded a more positive view on the usefulness of ω-3 supplementation [

32].

In terms of the mechanisms that allow ω-3 to have the benefits described, it was suggested to be associated with the potential modulation of key CV risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high serum triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL)- cholesterol, elevated post-prandial lipidemia, endothelial dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmia, heart rate and heart rate variability and a tendency towards thrombosis and inflammation. Many studies have indeed confirmed that EPA and DHA have effects by improving all the above mentioned, while increasing both low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and HDL-cholesterol. Throughout the studies, the reduction of inflammation is marked by the reduction of the C-reactive protein (CRP), pro-inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 [

37].

While ω-3 has an acknowledged effect on CVD risk reduction, especially EPA and DHA, ω-6 PUFAs don’t have such acknowledgement. A study by Chowdhury et al [

38] found no evidence of dietary intake of ω-6 having any effect in reducing CVD risk. On the other hand, a meta-analysis published by Farvid et al. [

39], estimated that replacing 5% of the dietary energy of saturated FA with LA was associated with a lower risk of CHD events and CHD deaths by 9% and 13%, respectively [

39].

Even though there is much evidence of ω-3 PUFAs having many cardioprotective effects, the evidence on ω-6 PUFAs is not so clear. This lack of conclusive information highlights the need for further investigation to better understand this topic.

6.3. Effects on Brain and Central Nervous System

6.3.1. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the two most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases, affecting millions of people over the age of 65 years and, with the extension of life expectancy, the number of people affected by these diseases tends to grow [

40].

The reasons behind the development of AD are still not fully understood but it is believed to be connected to a combination of factors, like environmental and genetic factors. Nowadays, there are three specific gene mutations that are connected to the development of this disease by affecting the production of amyloid-ꞵ [

41]. This disease is characterized by amyloid plaques and protein accumulation in the brain, contributing to loss of connection between nerve cells and, consequently, leading to brain tissue death [

40]. The main symptoms include dementia, memory loss and cognitive decline [

1].

The pathogenesis behind PD, like AD, is still not fully understood but is believed to be connected to environmental and genetic factors. The disease is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neuronal cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a region in the brain responsible for movement control, and the accumulation and aggregation of ɑ-synuclein protein in the form of Lewy bodies. The main symptoms include bradykinesia, resting tremor, muscular rigidity and postural instability [

42].

Although AD and PD have different pathogenesis and clinical manifestations, they share some common mechanisms, like mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. It is suggested that ω-3 PUFAs, more specifically DHA, is connected to these diseases and can play a role in preventing its development [

1].

A higher intake of DHA has been associated with a lower risk of developing cognitive impairment or AD. DHA induces the activation of synaptophysin-1 which is a glycoprotein found in synaptic vesicles that facilitates synaptogenesis and enhances cognitive performance. The biosynthesis and consequent phosphorylation of synaptophysin-1 is regulated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. DHA promotes synaptic transmission by upregulating the brain-derived neurotrophic factor and thereby augmenting neural plasticity. DHA can also inhibit tau phosphorylation [

1]. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that, when hyperphosphorylated, can cause microtubule decomposition and accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles [

43]. DHA can also mitigate amyloid-ꞵ caused neurotoxicity, as well as neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting the formation and aggregation of amyloid-ꞵ peptides [

1]. Between the studies available on the effects of ω-3 PUFAs on AD, the heterogeneity is significant, having some studies report a benefic effect of the use of ω-3 PUFAs supplementation and others mentioning no observed effect [

40]. This highlights the necessity of more and better studies to be made.

Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, DHA is also believed to be capable of slowing and preventing the development of PD. DHA can regulate the expression of ɑ-synuclein and maintain synaptic homeostasis and neuronal activity. It can also increase the expression of glial derived neurotrophic factors (GDNFs), preventing glial dysfunction [

1].

Many studies have tried to establish a correlation between the consumption of ω-3 PUFAs and the development of PD and, while many achieved promising results in showing that ω-3 PUFAs can indeed slow the progression of the disease, others did not show any correlation. This data shows, once again, the need for further investigation in order to fully understand the neuroprotective properties that ω-3 PUFAs show.

When it comes to the effects of ω-6 PUFAs, more specifically ARA, the results are very contradictory. While the consumption of ARA is essential for normal brain function, excessive consumption can lead to neuroinflammation and neuronal damage. It is also suggested that a high ratio of ω-6:ω-3 can be linked to the development of neurodegenerative diseases, being a ratio closer to 1:1 one of the most recommended [

40].

Studies on rats have shown that the consumption of ARA can help prevent cognitive impairment associated with the abnormal processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and, therefore, preventing the formation of insoluble amyloid-ꞵ in neuritic plaques. On the other hand, other studies on rats have shown that ARA can augment the production and deposition of amyloid-ꞵ. The difference can be due to differences in doses applied but such is not specified [

1].

Eicosatrienoic acid (EET) is a metabolite of ARA that is widely spread on the brain and shows antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, being constituted a therapeutic target in PD due to those properties. Studies on the Drosophila model show that it can increase the expression of antioxidant enzymes and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation. Moreover, in vitro studies have shown that ARA can promote the ɑ-helical folding of ɑ-synuclein, resulting in reduced neuronal toxicity. In PD, ɑ-synuclein typically aggregates into toxic ꞵ-sheet structures, whereas in healthy neurons, it predominantly exists as non-toxic ɑ-helical oligomers [

1].

In short, while a higher intake of ω-3 PUFAs is associated with enhanced synaptic plasticity, inhibition of inflammatory responses, protection of cholinergic neurons and brain nerve health, ω-6 PUFAs and its metabolites have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, leaving doubts in its beneficial effects and in need of more research.

6.3.2. Depressive Disorder

Depressive disorders, more commonly known as depression, is a common mental disorder that affects 4% of adult males, 6% of adult females and 5.7% of the population over 60 years old. Its main symptoms are feeling sad, irritable, empty and with no interests and pleasure in activities [

44].

ω-3 PUFAs have shown promising results as an emerging auxiliary treatment for depression. Preclinical studies on rats fed with a diet rich in EPA for 6 weeks showed increased levels of dopamine and serotonin in the hippocampus. Other studies on offspring rats showed that those lacking ω-3 PUFAs developed nerve damage in the hippocampus and had reduced levels of serotonin and norepinephrine. This points to the capability of ω-3 PUFAs in preventing depression-like behavior. In addition, studies have shown that there is a negative relation between the levels of cortisol on depressed patients [

1] (cortisol levels are usually high on depressed patients [

45]) and the levels of EPA and DHA in the blood due to its effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. It has also been shown that patients with depression who increase the intake of EPA for 8 weeks show a reduced HPA axis activity and improved depression symptoms [

1].

ω-6 PUFAs and its effects on depression are not so clear. Anandamide (AEA) is an endocannabinoid derived from ARA that, in some studies, appears to be inversely related with depression [

46] while in other studies, it is said to impair serotonin neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), inducing a depression-like phenotype in mice. Other conflicting studies on PFC samples of postmortem humans previously diagnosed with depression show that DHA levels were reduced and the ratio of ARA:DHA increased, while other study also using PFC samples of postmortem humans previously diagnosed claims that there were no changes observed [

1].

6.3.3. Brain Development of Specific Population

When it comes to the effects of ω-3 on infant brain development, the main PUFA is DHA. While there are studies that report adverse to no effects, most studies report a beneficial effect. For example, a study conducted in Europe between 1992 and 2013 found that supplementation with DHA and ARA improved problem-solving skills at nine to ten months and led to fast information processing skills at six years of age. Another study, also testing DHA and ARA supplementation, showed a higher sweep visual-evoked potential (VEP) acuity at 12 months, increased mental development index at 18 months, better inhibitory function at three to five years of age and better verbal and full-scale IQ at six years, when compared to a control group with no supplementation [

47].

Between the results of the studies, there is a difference that is noteworthy between premature infants and term infants. Starting in the last trimester of gestation until the first two years of life, there is an accumulation of DHA from the womb that is lacking in premature infants. This may partly explain why the positive cognitive effects of DHA supplementation are more consistent in studies involving premature infants rather than those involving term infants. This does not fully explain the heterogeneity in results because there are conflicting results even between studies that only involve premature infants [

47].

In brief, the usage of DHA in infants is important, especially in premature infants, and it improves visual acuity, visual recognition memory, attention, psychomotor and mental development and the maturation of the brain’s white matter [

47].

6.4. Effects on the Inflammatory Process

Inflammation is a natural process, and includes three stages: initiation, development and extinction. If the last one fails, it becomes a chronic inflammation, leading to the possible development of other diseases. The main signs of inflammation are redness, heat, swelling, pain and loss of function [

48]. There are many mediators that participate in inflammation, such as cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1ra, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-ꞵ [

28].

ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs can generate mediators that have a potent influence on the inflammation process through two pathways, non-enzymatic or enzymatic [

28].

Since PUFAs have double bonds, they are susceptible to free radicals and prone to free radical-induced autoxidation and photodegradation, leading to the formation of non- enzymatic metabolites, such as phytoprostanes (PhytoPs) from ALA, isoprostanes (IsoPs) from EPA and ARA and neuroprostanes (NeuroPs) from DHA. From these, PhytoPs and NeuroPs seem to be the ones with effects on the inflammatory process [

28]. PhytoPs appear to be able to modulate the synthesis and overall level of PGs during the inflammatory process [

49] and NeuroPs have potent anti-inflammatory effects, similar to protectins [

28].

When it comes to the enzymatically originated mediators from PUFAs, they are called oxylipins, a broad term that includes many derivatives, including specialized pro-resolvin mediators (SPMs). SPMs are a novel group of compounds that derive from ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs and include lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and maresins. ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs are oxidized by specific groups of enzymes, COX, LOX and CYP. Generally, oxylipins originated from ω-3 PUFAs have more of an anti-inflammatory effect, while ω-6 PUFAs originated from oxylipins have more of a pro-inflammatory effect. The diet and supplementation influence the amount of each FA present in the organism, therefore the amount of oxylipins originated from each PUFA. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) is the enzyme responsible for realizing the PUFAs from the sn-2 position of phospholipids and turning them available to form oxylipins [

28].

Oxylipins can also be classified based on their precursors. Oxylipins derived from LA and ALA are called octadecanoids, from ARA and EPA are eicosanoids and from DHA are docosanoids [

28].

Besides the mediators synthesized from ω-3 PUFAs, another factor that contributes to the anti-inflammatory effects of EPA and DHA is the fact that they compete with ω-6 PUFAs’ enzymes to produce oxylipins. As mentioned, ω-3 PUFAs originate oxylipins with anti-inflammatory effects and ω-6 PUFAs originate oxylipins with pro-inflammatory effects, since they compete for the same enzymes to produce those oxylipins, a higher concentration of EPA and DHA means that the enzymes are less available for ω-6 PUFAs. Besides that, ω-3 PUFAs are also linked to the decrease of the levels of various inflammatory markers, such as cytokines like IL-1, acute-phase proteins like CRP and adhesion molecules [

2].

Since, as mentioned, ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs have both anti and pro-inflammatory effects, respectively, the concept of ω-6:ω-3 ratio becomes important again. A higher ratio might increase the levels of pro-inflammatory oxylipins and comprise the resolution of the inflammatory process. On the other hand, a higher intake of ω-3 PUFAs can lower the amounts of ω-6-derived oxylipins and comprise the correct initiation of the inflammatory process. A balanced ratio of 1:1 appears to be the most advisable [

40].

6.5. Effects on Cancer

Cancer is a complex disease characterized by the uncontrolled growth and division of abnormal cells. These cells can form a mass known as a tumor, which may be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Malignant tumors have the potential to invade nearby tissues and spread to other parts of the body through the bloodstream or lymphatic system in a process known as metastasis. This ability to spread makes cancer particularly challenging to treat [

50].

There are many studies that show an association between the intake of ω-3 PUFAs and a reduced risk of many types of cancer, such as leukemia [

51], breast cancer [

52], colon cancer [

53,

54], prostate cancer [

55] and melanoma [

56].

On the other hand, ω-6 PUFAs, more specifically ARA is associated with cancer-causing effects. Inflammation is a well-known factor in cancer development and, as mentioned in the point above, ω-6 PUFAs are more generally known to have a pro-inflammatory effect, being associated with cancer development through the production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, such as PGE2 that enhances tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis. However, it is also believed that ω-6 PUFAs can inhibit the growth and development of cancer through a mechanism that is also associated with ω-3 PUFAs, that is the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and mitochondrial damage, causing the death of the cancer cells [

1].

The ω-6:ω-3 PUFAs ratio is also a factor that can influence the development of cancer. Lower ratios are associated with the upregulation of the tumor suppressor SMAR1 expression and downregulation of the oncogenic factor MARBP Cux/ CDP expression. The increased SMAR1 expression also stimulates the expression of the p21 protein, inhibiting cell cycle progression [

1].

Besides the reduction of inflammation, ω-3 PUFAs, more specifically EPA and DHA, also have other known mechanisms through which they might influence the cancer development. DHA have shown a strong ability to induce apoptosis in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells through caspase-8 activation [

57]. EPA and DHA have also shown to significantly increase the mitochondrial membrane potential. This increased potential leads to the increase of ROS production in colorectal cancer cells, stimulating a proapoptotic mechanism by changing the active form of the caspase-3 and caspase-9 expression [

1].

The production of nitric oxide (NO) occurs in the mitochondria and is catalyzed by mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase (mtNOS). Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is an enzyme that produces NO. iNOS and NO are associated with cancer development. Peroxidation products of EPA and DHA can inhibit iNOS induction, consequentially reducing NO production in hepatocytes. An anti-inflammatory effect results from this mechanism, therefore having anti-cancer effects [

1].

Since ω-3 PUFAs and ω-6 PUFAs compete for the same enzymes to produce oxylipins, increased ω-3 PUFAs decrease the production of ω-6-derived oxylipins like PGE2 and acts as a natural COX inhibitor, inhibiting tumor cell growth [

15].

In order for the metastatic cell migration to occur, an upregulation of chemokine receptors is required. These chemokines receptors act as sensors for cell trafficking. A metabolite of DHA, resolvin D1 (RvD1), has shown to have the ability to reduce the surface expression of CXCR4, a chemokine receptor crucial in chemotherapy, and CXCR4-mediated cell migration [

1].

In addition, supplementation with ω-3 PUFAs have also shown to be associated with better tolerability of chemotherapy for certain groups [

58].

7. Omega-3 and Omega-6 and the Market: A Case Study in Portugal

7.1. Medicines and Natural Supplements Using ω-3 and ω-6

There is a wide range of food supplements available that are based on ω-3 and ω -6 fatty acids, with a particularly large variety focused on ω -3. Numerous brands offer different omega supplementation products, varying in source, formulation, and concentration. Some of the claims are reducing the CV risk, cholesterol levels, improving brain function in adults, while some are specific for children in order for them to have a better brain function and development, maintain eyesight and, in the case of children diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) to be used as a complement to the therapy used. There are also brands that offer supplements containing ω-6 in conjunction with ω-3 and, some also include ω-9 (which is not a target subject of this review). These products are directed towards a good CV health, skin health, immune function and general well-being [

59].

When it comes to medicines based on omega FAs, in Portugal, there is only one that is currently authorized, since 2003 and being commercialized. It is a medicine composed of ω-3 FAs in the EE form, having a total dose of 840 mg per soft gel capsule (460 mg of EPA and 380 mg of DHA). The therapeutic indication of this medicine is as a treatment of hypertriglyceridemia when diet alterations are not enough. It can be used as treatment to stage IV hypertriglyceridemia as a monotherapy and stage IIb/III hypertriglyceridemia in association with statins. In terms of posology, it is recommended to use 2 soft gel capsules per day, being possible to increase the dosage to 4 soft gel capsules if needed [

60,

61].

7.2. Market Perspectives and Legislation

ω-3 PUFAs supplements are the most prescribed food supplements which justifies their large availability in the market. The market is also predicted to grow by 6.5% from 2023 to 2032, exceeding 4.2 billion dollars by the year 2032 [

40].

The legislation and entities regulating food supplements are generally different from those for medicines. This regulatory gap raises several concerns, particularly regarding quality control and product safety. Unlike medicines, food supplements are not subject to mandatory pre-market testing to verify the accuracy of label claims, such as the exact dosage of active ingredients. As a result, many supplements may not contain the stated concentrations or may include unintended substances originating from the raw materials used in their production. For instance, ω-3 fatty acid supplements derived from fish oil can sometimes contain contaminants like methylmercury — a toxic compound known to pose serious health risks. The absence of strict, harmonized testing requirements across markets allows such risks to persist, potentially compromising both consumer safety and the reliability of the health claims made by manufacturers.

7.3. Drug Interactions with ω-3 and ω-6

While ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs offer therapeutic benefits, potential drug-nutrient interactions, especially in patients on anticoagulants, hypertensive or dyslipidemic individuals, those using immunosuppressants or anti-inflammatory drugs must be controlled [

62].

When it comes to drug-drug interactions, clinical trials have demonstrated that some medicines containing ω-3 can increase the time of bleeding causing an interaction with medicines that also increase the time of bleeding (e.g. anticoagulant and antiplatelet) [

61].

Therefore, careful clinical monitoring, individualized dose adjustment, and appropriate dietary counseling are essential to ensure the safety and efficacy of combined therapy.

8. Adverse Effects of Misuse

When talking about adverse effects of misuse of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs, it covers both not getting enough quantities on the daily diet or through supplementation, leading to a deficiency of these nutrients in the organism, overconsumption of fish or supplements from fish oils that can lead to a consumption of high levels of methylmercury, and the known adverse effects related with the use of ω-3 FA medicine.

Although rarely described in humans, a deficiency in ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs can lead to dermatitis, renal hypertension, mitochondrial activity disorder, CVDs, type 2 Diabetes, impaired brain development, arthritis, depression and decreased body resistance to infection. In short, it leads to the opposite of the health benefits that proper intake of these nutrients has and can and can highly comprise one’s health [

2].

Another noteworthy adverse effect, previously mentioned in this review, is the possible overexposure to methylmercury. Methylmercury, present in some fishing areas, contaminates the fish that are one of the main sources of ω-3 PUFAs, is neurotoxic and can be especially harmful for the development of the central nervous system of the fetus. Since the legislation does not impose mandatory safety testing and content evaluation for food supplements, this problem can be carried on to the food supplements based on fish oils, presenting itself as a problem worth mentioning and raising awareness about [

9].

When it comes to ω-3 based medicine, the most common adverse effects that are expected when using it are: abdominal distention, abdominal pain, obstipation, diarrhea, dyspepsia, flatulence, burping, gastroesophageal reflux, nausea and vomiting [

61].

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Through this review, the importance of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs for human health becomes unquestionable, having many important health benefits. Despite those benefits, in many diets, such as the western diet, the ω-6:ω-3 ratio is very unbalanced in favor of the ω-6 PUFAs, which is not ideal and shows the importance of raising awareness to the general population and the health professionals to promote a healthier ratio closer to the 1:1, that is considered most effective in providing maximum health benefits. This raise of awareness should also focus on the health benefits offered by these nutrients, encouraging the population on incorporating ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs on the daily diet through both foods and supplements in a more informed and conscious manner.

It is also noteworthy that ω-3 fatty acid–based medicines have been available on the market for several decades and have demonstrated both safety and efficacy, particularly in managing hypertriglyceridemia and supporting CV health. However, statins remain the first-line therapy in most clinical guidelines for dyslipidemia and CV risk reduction. This preference is largely due to the extensive evidence supporting the effectiveness of statins. As a result, ω-3–based therapies are often considered adjunctive rather than primary treatment, despite their favorable safety profile and therapeutic potential.

Another relevant aspect is the current regulatory framework governing food supplements, which varies significantly between countries and differs from the more stringent systems applied to medicines. One of the key challenges identified is the limited mandatory oversight regarding the verification of nutrient content in supplements. This can lead to discrepancies between the declared and actual concentrations of active ingredients. For example, in fish oil–based ω -3 supplements, insufficient quality control may allow the presence of environmental contaminants such as methylmercury, which could pose health risks if not adequately managed.

Internationally, efforts are ongoing to harmonize standards and improve transparency in this sector, ensuring the application of standardized manufacturing practices and enhancing the overall quality, safety, and reliability of supplements marketed to the public.

Furthermore, integrating controlled extraction technologies could improve reproducibility and guarantee the consistency of composition in supplement formulations. Such advancements may support the broader use of food supplements as part of preventive healthcare strategies, aligned with global public health goals.

It is also important to raise awareness in the scientific community for the need of developing more and better studies in order to better understand the role and mechanisms behind all the health benefits of the ω-3 and ω-6 PUFAs, especially for ω-6 PUFAs since many of its health benefits are still not fully understood because there are studies that conclude both beneficial and harmful effects for this nutrient, becoming evident the need for more in-depth studies. Another important measure is the development of clear, universal and evidence-based recommendations on the dosages that should be taken daily.

Another measure that could be taken in the future is the incorporation of more complete and detailed information about the amount of ω-3 and ω-6 present in each product, as well as a very short description of the main health benefits associated with its consumption and the recommended daily amounts that each person should consume. This measure could be used, not only for ω-3 and ω-6 but also for other important nutrients, this way improving the ability of the consumer to make an informed and conscious decision and improve the general public’s literacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., C.P.R. and R. P.; methodology, D.G., C.P.R. and R.P.; formal analysis and investigation, D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing C.P.R. and R.P.; supervision, C.P.R. and R.P.; funding acquisition, C.P.R. and R.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this mancript:

| ω-3 |

Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

| ω-6 |

Omega-6 Fatty Acids |

| ACC |

Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ADHD |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AEA |

Anandamide |

| AHA |

American Heart Association |

| ALA |

ɑ-Linoleic Acid |

| APP |

Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| ARA |

Arachidonic Acid |

| ASAE |

Autoridade de Segurança Alimentar e Económica |

| BBB |

Blood-Brain Barrier |

| CAT1 |

Carnitine Acetyltransferase 1 |

| CE |

Cholesterol Esters |

| CHD |

Coronary Heart Disease |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| Cmax |

Maximum Concentration |

| COX |

Cyclooxygenase |

| cPLA2 |

Cytosolic Phospholipase A2 |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| CV |

Cardiovascular |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| CYP |

Cytochrome P450 |

| DAG |

Diacylglycerols |

| DGAV |

Direção-Geral da Alimentação e Veterinária |

| DGLA |

Dihomo-γ-Linoleic Acid |

| DHA |

Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| DiHOME |

Dihydroxy-Octadecenoic Acid |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| DPA |

Docosapentaenoic Acid |

| EE |

Ethyl Esters |

| EET |

Eicosatrienoic Acid |

| ELOVL |

Elongase |

| EPA |

Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| ETA |

Eicosatetraenoic Acid |

| FA |

Fatty Acid |

| FADS |

Fatty Acid Desaturase |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| FFA |

Free Fatty Acid |

| GDNF |

Glial Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| GLA |

γ-Linoleic Acid |

| HDL |

High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| HFrEF |

Heart Failure Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HODE |

Hydroxy-Octadecadienoic Acid |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal |

| INFARMED |

Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde, I.P. |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| IsoPs |

Isoprostanes |

| IU |

International Units |

| LA |

Linoleic Acid |

| LCFA |

Long-Chain Fatty Acid |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| LOX |

Lipoxygenase |

| LPL |

Lipoprotein-Lipase |

| LT |

Leukotrienes |

| MACE |

Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| MCFA |

Medium-Chain Fatty Acid |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MI |

Myocardial Infarction |

| mtNOS |

Mitochondrial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| NeuroPs |

Neuroprostanes |

| NNT |

Number Needed to Treat |

| NO |

Nitric Oxide |

| PD |

Parkinson’s Disease |

| PFC |

Prefrontal Cortex |

| PG |

Prostaglandin |

| PGI |

Prostacyclin |

| PhytoPs |

Phytoprostanes |

| PL |

Phospholipids |

| PPAR |

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| PSEN1 |

Presenilin 1 |

| PSEN2 |

Presenilin 2 |

| PUFA |

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RR |

Relative Risk |

| RvD1 |

Resolvin D1 |

| SCFA |

Short Chain Fatty Acid |

| SDA |

Stearidonic Acid |

| SPM |

Specialized Pro-resolvin Mediator |

| SREBP |

Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein |

| TAG |

Triacylglycerols |

| TGF |

Transforming Growth Factor |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| TNF |

Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TXA |

Thromboxane |

| USA |

United States of America |

| VEP |

Visual-Evoked Potential |

| VFA |

Volatile Fatty Acid |

| VLCFA |

Very Long-Chain Fatty Acid |

| VLDL |

Very-Low-Density Lipoproteins |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Xu, R.; Molenaar, A.J.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y. Mode and Mechanism of Action of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Unsaturated Fatty Acids in Chronic Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Heart Foundation [Internet]. 2022. What are macronutrients? Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/ask-the-expert/macronutrients.

- Johnson, B. Kendall Reagan Nutrition Center. 2022. Importance of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Available from: https://www.chhs.colostate.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Healthy Diet: Key Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Fischler, C. Food, self and identity. Social Science Information 1988, 27, 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. In: Annual Review of Public Health [Internet]. 2008. p. 253–72. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/docserver/fulltext/pu/29/1/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926.pdf?expires=1750673907&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=C3E11B49318D43D5690DDB5E226B604F.

- Schönfeld P, Wojtczak L. Short- and medium-chain fatty acids in energy metabolism: The cellular perspective [Internet]. Vol. 57, Journal of Lipid Research. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Inc.; 2016. p. 943–54. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4878196/.

- Cholewski M, Tomczykowa M, Tomczyk M. A comprehensive review of chemistry, sources and bioavailability of omega-3 fatty acids [Internet]. Vol. 10, Nutrients. MDPI AG; 2018. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6267444/.

- Sassa, T.; Kihara, A. Metabolism of Very Long-Chain Fatty Acids: Genes and Pathophysiology. Biomol. Ther. 2014, 22, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem Open Chemistry Database at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.-S. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Dietary sources, metabolism, and significance — A review. Life Sci. 2018, 203, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shurtleff, D.; Arensdorf, A.; Still, P.C.; Gust, S.W.; Chideya, S.; Hopp, D.C.; Belfer, I. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health: Priorities for Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 391, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Dietary Supplements [Internet]. 2022. Omega-3 Fatty Acids- Fact sheet for consumers. Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-Consumer/.

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avallone, R.; Vitale, G.; Bertolotti, M. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Neurodegenerative Diseases: New Evidence in Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, AP. Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases [Internet]. Vol. 233, Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2008. p. 674–88. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18408140/.

- Richter, C.K.; Bowen, K.J.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Skulas-Ray, A.C. Total Long-Chain n-3 Fatty Acid Intake and Food Sources in the United States Compared to Recommended Intakes: NHANES 2003–2008. Lipids 2017, 52, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, L. Williamson L. American Heart Association. 2023. Are you getting enough omega-3 fatty acids? Available from: https://www.heart.org/en/news/2023/06/30/are-you-getting-enough-omega-3-fatty-acids.

- Fialkow, J. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Formulations in Cardiovascular Disease: Dietary Supplements are Not Substitutes for Prescription Products. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2016, 16, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nur Mahendra MY, Kamaludeen J, Pertiwi H. Omega-6: Its Pharmacology, Effect on the Broiler Production, and Health [Internet]. Vol. 2023, Veterinary Medicine International. Hindawi Limited; 2023. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9995196/.

- Balić, A.; Vlašić, D.; Žužul, K.; Marinović, B.; Bukvić Mokos, Z. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Chugh, V.; Gupta, A.K. Essential fatty acids as functional components of foods- a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 51, 2289–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banca Dati di Composizione Degli Alimenti Per Studi Epidemiologici in Italia [Internet]. BDA. Available from: https://bda.ieo.it/?page_id=29&lang=en.

- U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Food Data Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Harnack, K.; Andersen, G.; Somoza, V. Quantitation of alpha-linolenic acid elongation to eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid as affected by the ratio of n6/n3 fatty acids. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition : report of an expert consultation, 10-14 November 2008, Geneva [Internet]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2010. Available from: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/nutrition/docs/requirements/fatsandfattacidsreport.pdf.

- Liput, K.P.; Lepczyński, A.; Ogłuszka, M.; Nawrocka, A.; Poławska, E.; Grzesiak, A.; Ślaska, B.; Pareek, C.S.; Czarnik, U.; Pierzchała, M. Effects of Dietary n–3 and n–6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Cancerogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa KN, Fritz K, Parmar M. omega-3 Fatty Acids. StatPearls Publishing LLC [Internet]. 2024 Feb 28; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564314/.

- Logan, S.L.; Spriet, L.L.; Nishi, D. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation for 12 Weeks Increases Resting and Exercise Metabolic Rate in Healthy Community-Dwelling Older Females. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0144828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Noreen, E.; Sass, M.J.; Crowe, M.L.; A Pabon, V.; Brandauer, J.; Averill, L.K. Effects of supplemental fish oil on resting metabolic rate, body composition, and salivary cortisol in healthy adults. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2010, 7, 31–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elagizi, A.; Lavie, C.J.; O’keefe, E.; Marshall, K.; O’keefe, J.H.; Milani, R.V. An Update on Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, L.; Mafham, M.; Wallendszus, K.; Stevens, W.; Buck, G.; Barton, J.; Murphy, K.; Aung, T.; Haynes, R.; et al.; Ascend Study Collaborative Group Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.-M.; Christen, W.; Bassuk, S.S.; Mora, S.; Gibson, H.; Albert, C.M.; Gordon, D.; Copeland, T.; et al. Marine n−3 Fatty Acids and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Steg, P.G.; Miller, M.; Brinton, E.A.; Jacobson, T.A.; Ketchum, S.B.; Doyle, R.T., Jr.; Juliano, R.A.; Jiao, L.; Granowitz, C.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Icosapent Ethyl for Hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernasconi AA, Wiest MM, Lavie CJ, Milani R V., Laukkanen JA. Effect of Omega-3 Dosage on Cardiovascular Outcomes: An Updated Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Interventional Trials. Mayo Clin Proc 2021, 96, 304–13.

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Marine Omega-3 (N-3) Fatty Acids for Cardiovascular Health: An Update for 2020. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, Crowe F, Ward HA, Johnson L, et al. Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids With Coronary Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med Available from: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M13-1788?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. 2014, 160.

- Farvid, M.S.; Ding, M.; Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Chiuve, S.E; Steffen, L.M.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Dietary Linoleic Acid and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Circulation 2014, 130, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousparou, C.; Fyrilla, M.; Stephanou, A.; Patrikios, I. DHA/EPA (Omega-3) and LA/GLA (Omega-6) as Bioactive Molecules in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez JAS, González HM, Léger GC. Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2019, 167, 231–255.

- Gómez-Benito M, Granado N, García-Sanz P, Michel A, Dumoulin M, Moratalla R. Modeling Parkinson’s Disease With the Alpha-Synuclein Protein [Internet]. Vol. 11, Frontiers in Pharmacology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.00356/full.

- Johnson GV, Hartigan JA. Tau Protein in Normal and Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: An Update * [Internet]. Vol. 1, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. IOS Press; 1999. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12214129/.

- Organisation, W.H. Depression. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Dziurkowska, E.; Wesolowski, M. Cortisol as a Biomarker of Mental Disorder Severity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Hillard, C.J. Role of endocannabinoid signaling in anxiety and depression. In Behavioral neurobiology of the endocannabinoid system; Springer, 2009; pp. 347–371. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Lee S, Rayalam S, Park HJ. DHA Supplementation and Infant Brain Development: Role of Gut Microbiome. Nutrition Research [Internet]. 2024 Nov; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S027153172400112X.

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. 2025. In brief: What is an inflammation? Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279298/.

- Campillo, M.; Medina, S.; Fanti, F.; Gallego-Gómez, J.I.; Simonelli-Muñoz, A.; Bultel-Poncé, V.; Durand, T.; Galano, J.M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á.; et al. Phytoprostanes and phytofurans modulate COX-2-linked inflammation markers in LPS-stimulated THP-1 monocytes by lipidomics workflow. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 167, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCI. What Is Cancer? 2021 [cited 2023; National Cancer Institute]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer.

- Arita, K.; Kobuchi, H.; Utsumi, T.; Takehara, Y.; Akiyama, J.; A Horton, A.; Utsumi, K. Mechanism of apoptosis in HL-60 cells induced by n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids 1 1Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; CsA, cyclosporin A; Cyt.c, cytochrome c; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate; DPA, docosapentaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; HE, hydroethidine; JC-1, 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazol carbocyanine iodide; MPT, membrane permeability transition; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species; and z-VAD-fmk, z-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 62, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Stavro, P.M.; Thompson, L.U. Dietary Flaxseed Inhibits Human Breast Cancer Growth and Metastasis and Downregulates Expression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Nutr. Cancer 2002, 43, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calviello G, Nicuolo F Di, Gragnoli S, Piccioni E, Serini S, Maggiano N, et al. n-3 PUFAs reduce VEGF expression in human colon cancer cells modulating the COX-2/PGE induced ERK-1 and -2 and HIF-1α induction pathway. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 2303–2310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberland, J.P.; Moon, H.-S. Down-regulation of malignant potential by alpha linolenic acid in human and mouse colon cancer cells. Fam. Cancer 2014, 14, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, J.C.; Masko, E.M.; Wu, C.; Keenan, M.M.; Pilla, D.M.; Aronson, W.J.; Chi, J.-T.; Freedland, S.J. Fish oil slows prostate cancer xenograft growth relative to other dietary fats and is associated with decreased mitochondrial and insulin pathway gene expression. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013, 16, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Hakozaki, M.; Uemura, A.; Yamashita, T. Effect of fatty acids on melanogenesis and tumor cell growth in melanoma cells. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung Kang, K.; Wang, P.; Yamabe, N.; Fukui, M.; Jay, T.; Ting Zhu, B.T. Docosahexaenoic Acid Induces Apoptosis in MCF-7 Cells In Vitro and In Vivo via Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Caspase 8 Activation. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moceliin MC, Camargo C de Q, Fabre ME de S, Trindade EBS de M. Fish oil effects on quality of life, body weight and free fat mass change in gastrointestinal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A triple blind, randomized clinical trial. J Funct Foods 2017, 31, 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WELL’S [Internet]. WELL’S. Available from: https://wells.pt.

- INFARMED [Internet]. INFOMED. Available from: https://extranet.infarmed.pt/INFOMED-fo/index.xhtml.

- RCM omacor [Internet]. BASF AS; 2003. Available from: https://extranet.infarmed.pt/INFOMED-fo/detalhes-medicamento.xhtml.

- MedScape [Internet]. Drug Interaction Checker. Available online: https://reference.medscape.com/drug-interactionchecker.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).