Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- What is the geographic distribution of studies on generative AI in African higher education?

- What opportunities have generative AI tools created for higher education in Africa?

- What ethical concerns are raised in the literature regarding the use of generative AI among African university students and institutions?

- To what extent are African higher education institutions prepared for adoption, based on policies, infrastructure, and faculty readiness?

Theoretical Framework

Methodology

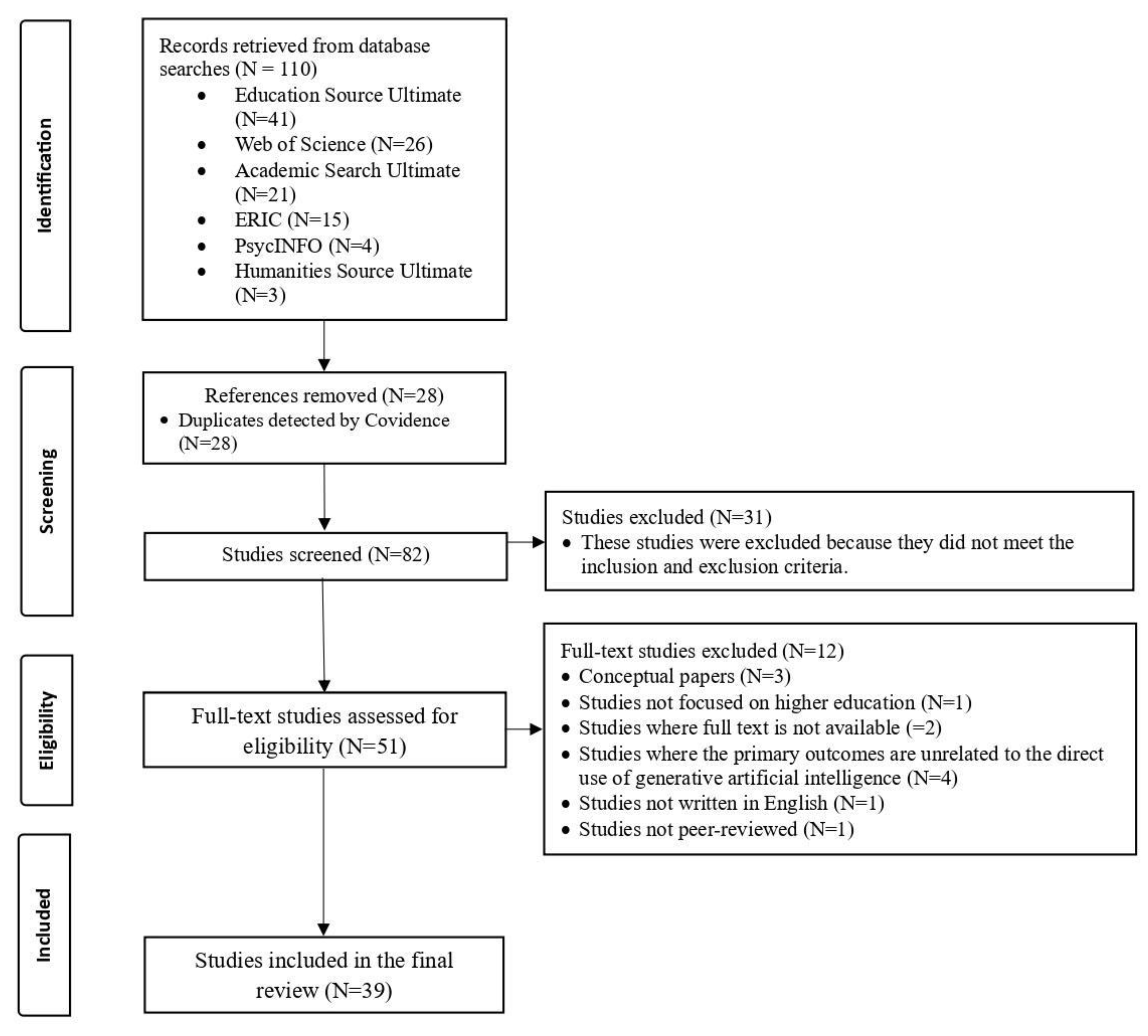

Systematic Review Approach

Search Strategy

Data Sources

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Type | Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers | Reviews, conceptual papers, logs, opinion pieces, non-scholarly sources, editorials, book reviews |

| Language | English | Non-English publications (unless translated) |

| Time Frame | 2022-2025 | Articles published before 2022 |

| Geographical Focus | Studies conducted in or focused on Africa | Studies with no relevance to African contexts |

| Educational Level | Higher education: universities, colleges, polytechnics, teacher education | Studies do not focus on higher education (e.g., K–12 education, corporate training, or informal learning settings) |

| AI Tools Used | Focus on GenAI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard, Gemini, LLaMA, Consensus App, NotebookLM) | Studies do not focus on AI or use only traditional AI (e.g., expert systems, predictive analytics) |

| Methodology | Empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed). | Technical engineering papers without relevance to educational use or context |

| References | Country | AI Tools Used | Focus | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdaljaleel et al. (2024) | Egypt | ChatGPT | Determinants of attitude and usage; validation of the TAME-ChatGPT scales. | Students showed positive attitudes toward ChatGPT driven by ease of use, perceived usefulness, social influence, and low perceived risk. Usage was relatively high, highlighting the need for AI literacy and tailored institutional policies. |

| Combrinck (2024) | South Africa | ChatGPT, Julius AI | Integration of generative AI in mixed methods research data analysis (tutorial and case study) | Demonstrated how ChatGPT can assist with qualitative coding, quantitative descriptive analysis, and integration of mixed methods data. Found descriptive statistics outputs to be reliable, and qualitative coding moderately aligned with human coding when trained with examples. |

| Indrawati et al. (2025) | Botswana | ChatGPT | Adoption determinants (UTAUT2) using survey (n=518) and SmartPLS | Personalized support is seen to improve learning performance. Digital divides and resource constraints limit equitable uptake. Personal innovativeness and performance expectancy were the strongest predictors of adoption; social influence and resource availability mattered less; the model explained of the variance in intention/usage, which calls for training and infrastructure upgrading. |

| Maphoto et al., 2024 | South Africa | ChatGPT, DWAs/APTs/AWE | Lecturers’, students’, markers’ views on academic writing | GenAI positively impacted teaching/learning, motivating students, and reducing monotony in large ODeL cohorts. Risks of misconduct/over-reliance; Turnitin limitations with AI-generated text highlighted. Advocates for human–AI collaboration frameworks and critical pedagogy to guide use. |

| Venter et al., 2025 | South Africa | Conversational AI (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Copilot) | Use in teaching/research; mixed-methods; activity theory | CAI supports qualitative analysis (theme discovery, time savings). Academics raise ethics and alignment-to-education concerns. Younger academics used CAI more for research than teaching; usage varied by faculty (science for teaching; business for research). |

| Ya’u & Mohammed, 2025 | Nigeria | AI-assisted writing tools (Grammarly, QuillBot, Turnitin feedback; LLMs) | Usage, proficiency effects, ethics (quantitative, n=350) | Heavy uptake (75% users) mainly for grammar (85%) and sentence structuring (70%); 65% believe AI enhances writing. 47% associate AI with plagiarism and 49% with harm to originality (risk of dependence and weakened independent literacy). Recommends structured integration that couples AI with critical-thinking instruction. |

| Sallam et al., 2025 | Egypt | ChatGPT | Apprehension scale development/validation (FAME) and anxiety toward GenAI (n=587) | Prior use of ChatGPT was linked to lower apprehension. Apprehension was neutral on average; Mistrust scored highest, then Ethics; pharmacy & medical laboratory students were most apprehensive. The scale confirms a valid, reliable FAME tool; it urges curricula that blend technical proficiency with ethics. |

| Ahmad et al., 2024 | Egypt, Sudan | ChatGPT, Bard AI, Bing AI, Chatsonic, Writesonic, OpenAI Playground, Claude, Socratic, Jasper, Falcon LLM, LaMDA2 | Awareness, benefits, threats, attitudes, satisfaction | Users reported greater benefits than non-users. ChatGPT used by 81% of AI-aware respondents; results signal a readiness gap and need for awareness/skills programs. |

| van den Berg & du Plessis (2023) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Contribution of generative AI (ChatGPT) to lesson planning, critical thinking, and openness in teacher education |

ChatGPT can generate basic lesson plans, worksheets, and visual presentations, saving teachers time and promoting openness and equity. Its use can enhance teachers critical thinking by requiring evaluation and adaptation of AI-generated content. Limitations include potential bias, inaccuracies, and plagiarism concerns; thus, ChatGPT should supplement, and not replace teachers. |

| Venter et al., 2024 | South Africa | ChatGPT | Opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations in using conversational AI in teaching, learning, and research | Many academics use CAI for research support; recognize numerous advantages for teaching/research. The study highlights ethical integration challenges in the adoption of ChatGPT. |

| Ivanov et al., 2024 | Egypt | ChatGPT | Factors influencing adoption of generative AI through the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | Perceived strengths/advantages of GenAI significantly increase attitude, subjective norms, and perceived control. |

| Oluwadiya et al., 2023 | Nigeria | ChatGPT (43.6%); other AI (grammar checkers 62.3%) | Perceptions, benefits, and risks of AI among medical students and lecturers (10 universities) | Students reported higher prior use than lecturers and were more likely to fear dehumanized care, skill decline, redundancy, and patient harm (e.g., 70.6% vs. 60.8%; 79.3% vs. 71.3%). Opportunities co-existed with pronounced ethical and patient-safety concerns, underscoring a need for curriculum integration and guidance. |

| Adewale, 2025 | South Africa | ChatGPT | ChatGPT usage among female academics and researchers | Mixed perceptions: Many used ChatGPT to support research productivity, but some feared that its unethical use could compromise integrity. ChatGPT improved productivity, but required guidelines and mentoring for ethical use and upskilling of female academics. |

| Hidayat-ur-Rehman & Ibrahim, 2024 | Egypt | ChatGPT | Factors shaping educators’ adoption (mixed-methods; 243 surveys) | Intention to use is influenced by effort expectancy, autonomous motivation, learner AI competency, and innovative behavior. Resistance arose from perceived unfair evaluation, overreliance, and bias/inaccuracy; concerns about fraudulent use were insignificant. The study highlights the need for training and ethical safeguards |

| Ojo (2024) | Nigeria | ChatGPT | Factors influencing students’ adoption of ChatGPT in learning (Technology Acceptance Model) | Behavioral intention to use ChatGPT was strongly predicted by perceived usefulness, ease of use, personal innovativeness, and social influence. Perceived risk negatively influenced intention. The study highlights ethical issues (e.g., academic integrity, critical thinking) and emphasizes the need for policies and balanced use of AI. |

| Essien et al., 2024 | Nigeria | ChatGPT | Socio-cultural influences on GenAI engagement (activity theory; 899 students, 17 universities) | Student engagement is enhanced by ease of use and alignment with educational goals. Engagement is hindered by frequent need for technical support and socio-cultural barriers (e.g., norms, infrastructure gaps). The study recommends user-friendly tools, robust support, and culturally aligned policies. |

| Baidoo-Anu et al., (2024) | Ghana | ChatGPT | Develop and validate the Students’ ChatGPT Experiences Scale (SCES) and examine awareness, perceptions, and demographic differences among higher education students. | SCES supported a three-factor solution: perceived academic benefits, accessibility, attitude, and academic concerns. |

| Daha & Altelwany (2025) | Egypt | ChatGPT | ChatGPT use is linked to goal orientations and self-efficacy. | Students with a high learning goal orientation and academic self-efficacy were less likely to use ChatGPT frequently, whereas those with an avoidant performance orientation used it more frequently. ChatGPT use was associated with procrastination and reduced academic performance. Institutions need policies to manage misuse and promote balanced use. |

| Opesemowo et al. (2024) | Nigeria | ChatGPT | Lecturers’ attitudes and perceptions on ChatGPT for instructional assessment. | Lecturers had low attitudes and perceptions of ChatGPT’s potential for assessment. Concerns focused on reliability, ethics, and risks to academic integrity. The study recommended targeted training to enhance lecturer readiness and improve their effective use in assessments. |

| Sevnarayan (2024) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Impact of ChatGPT in open distance e-learning (ODeL) | Students found ChatGPT more engaging/interactive, with personalized feedback and instant support; it also enhanced accessibility, including language support. Lecturers reported negative attitudes, risks of over-reliance, cheating, and authenticity issues. The study highlights the need for responsible-use guidance, lecturer training, policy, and assessment redesign to address equity and integrity. |

| Yusuf et al. (2024) –(a) | Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, Burkina Faso | ChatGPT, GrammarlyGo, Bard, DALLE, JukeBox, Synthesia, Stable Diffusion, MidJourney, ChatSonic, YouChat | Opportunities and threats of GenAI in higher education from multicultural perspectives | High awareness and positive intentions to use GenAI for information retrieval and text paraphrasing. Benefits include enhanced learning and productivity. Ethical concerns include academic dishonesty, declining cognitive skills, and culturally influenced views on responsible AI use. Emphasis on the need for robust, culturally sensitive policies for ethical integration. |

| Pramjeeth & Ramgovind (2024) | South Africa | ChatGPT, Copilot, Midjourney, and DALL-E | Ethical implications of GenAI tools in higher education. | The study highlighted the need for clear ethical guidelines and policies to ensure fairness and protect institutional reputations. |

| van Wyk et al (2023) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Views of academics on ChatGPT as an AI-based learning strategy at an open distance e-learning (ODeL) institution of higher education. | The study found three major themes that emerge from the analysis of the chat posting: awareness of ChatGPT as an AI conventional-based learning tool, benefits and drawbacks of ChatGPT as a conventional-based learning approach, and ChatGPT as a tool for enhancing student learning. |

| Ravšelj et al. (2025) | Egypt, Tanzania, Ghana | ChatGPT | Early student experiences and perceptions of ChatGPT’s usage, capabilities, ethics, satisfaction, learning-outcomes, skills development, labor-market implications, and emotional responses. | ChatGPT is primarily being used for brainstorming, text summarization, and literature search. The author expressed concerns about reliability, academic integrity, and the need for AI regulation. |

| Eldakar et al. (2025) | Egypt | GenAI | Integrate three models into one integrated model: TAM, UTAUT, and SCT to understand how GenAI self-efficacy, perceived ethics, academic integrity, social influence, facilitating conditions, perceived risks, ease of use, and perceived usefulness influenced academic researchers’ intention to adopt GenAI in research. | The study showed that GenAI self-efficacy, social influence, and perceived ethics are significantly related to perceptions of ease of use, usefulness, and intention to use GenAI. Facilitating conditions have a negative effect on perceived ease of use, and perceived risk does not affect perceived usefulness or intention to use significantly. Also, the study found that ethics and academic integrity affect perceptions of GenAI’s usage and utility. |

| Yusuf et al. (2024) - (b) | Nigeria | ChatGPT | Development and validation of a five-phase framework (familiarizing, conceptualizing, inquiring, evaluating, synthesizing) to train students' critical thinking in synthesizing AI-generated texts. | The framework significantly improved students’ critical thinking (CrT) scores across tasks (Practice M=2.84; Mastery M=3.68; Challenge M=4.33). In a comparative experiment, the framework outperformed a self-regulated learning model and an unstructured approach on interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation. |

| Mahfouz & AbdelMohsen (2025) | Egypt | ChatGPT | Students perceived ease of use, usefulness, ethical appropriateness, and concerns (privacy/security and impact on higher-order thinking skills) when using ChatGPT for EFL essay writing. | Students view ChatGPT as useful and easy to use. However, concerns exist about negative impacts on creativity, higher-order thinking, and scientific integrity. The paper recommendation includes regulatory practices, new assessment methods, and educator training to mitigate ethical risks. |

| Mutanga et al. (2024) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Lecturers’ attitudes toward and experiences of integrating AI tools into their teaching. | Enthusiastic lecturers praised AI for providing immediate, personalized feedback and supporting interactive lesson design. Cautiously optimistic lecturers piloted AI integration as a supplement to traditional methods, stressing professional development and balance. Skeptical lecturers raised concerns over accuracy, academic integrity, and potential misuse without adequate monitoring. |

| Namatovu & Kyambade (2025) | Uganda | ChatGPT | Leveraging AI in academia: university students’ adoption of ChatGPT for writing coursework (take home) assignments through the lens of UTAUT2 |

The findings show that performance expectancy, habit, and social influence significantly impact adoption, while effort expectancy and price value have less influence. |

| Singh (2023) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Maintaining the integrity of the South African university: The impact of ChatGPT on plagiarism and scholarly writing | Professors interviewed in the study expressed a welcoming stance toward generative AI tools such as ChatGPT. Rather than demonizing these technologies, they stressed the importance of educating students on how to engage with them responsibly and ethically. Much of the responsibility, they argued, falls on lecturers and academic institutions to cultivate a teaching and learning environment that embraces these tools. By integrating AI thoughtfully into pedagogy and curriculum design, universities can help shape more adaptive and forward-thinking scholarly practices |

| Abdelhafiz et al., (2025) | Egypt | ChatGPT | Knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, and practices of undergraduate medical students | 78.5% of students had used ChatGPT; positive perceptions, attitudes, and practices were reported; concerns existed about reliability, potential misuse, and impact on academic integrity and critical thinking. |

| Segbenya et al. (2024) | Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda. | ChatGPT, OpenAI, and QuillBot. | Modelling the influence of antecedents of artificial intelligence on academic productivity in higher education: a mixed-method approach |

The study found that academics hardly use the main AI tools/platforms, and those mainly used for research and teaching-related activities were ChatGPT, OpenAI, and Quillbot. These AI tools were used mostly for general searches for information on course-related concepts, course materials, and plagiarism checks, among others. The study further revealed that challenges associated with AI usage influenced the productivity of academics significantly. Finally, the availability of AI tools was found to engender AI usage, but does not directly translate into the productivity of academics. |

| Chauke et al. (2024) | South Africa | ChatGPT | Postgraduate Students’ Perceptions on the Benefits Associated with Artificial Intelligence Tools on Academic Success: In Case of ChatGPT AI tool | The study found that ChatGPT proves beneficial for postgraduate students, with some utilising the AI tool to refine their research topics before submission to their supervisors. Moreover, ChatGPT assists postgraduate students in identifying grammatical errors and paraphrasing their academic writing, contributing to the enhancement of their writing skills. |

| Mohlake & Mohale (2024) | South Africa | None (Questionnaire responses to learners’ adaptation to blended learning using artificial intelligence) | Student Assistants’ Perceived Leadership Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Reading and Writing Landscape | An analysis of the responses from 44 language consultants revealed three key findings. First, the majority do not consider AI a threat to their job security. Second, while they recognize the benefits of generative AI, they acknowledge the need for substantial reskilling to use it effectively. Third, many express concern that AI use among students may hinder creativity and critical thinking, while encouraging academic laxity and plagiarism. |

| Yakubu et al. (2025) | Nigeria | ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini | Students' behavioural intention to use content generative AI for learning and research: A UTAUT theoretical perspective | The findings showed that three of the factors, performance expectancy (α = 0.551, p < 0.001), effort expectancy (α = 0.466, p < 0.001), and social influence (α = 0.507, p < 0.001) were observed to be determinants of behavioural intentions to use CG-AI tools. Facilitating conditions, perceived risks, and attitude towards technology, on the other hand, showed no significant impact on students’ behavioural intention to use CG-AI tools. |

| Ofem et al. (2024) | Nigeria | ChatGPT | Examine students’ perceptions, attitudes, and utilization of ChatGPT, and the role of sex and age in these linkages. | The study found that regardless of sex or age, students with positive perceptions of ChatGPT were more prone to use it for dishonest academic purposes. Also, a sex disparity in the direct impact of perception on ChatGPT use, which was particularly pronounced for female students. Interestingly, significant age-related differences were observed, with a stronger effect observed for younger students, and a negative direct effect of attitude on ChatGPT use for academic dishonesty was recorded, with attitude further serving as a significant negative mediator of the relationship between perception and ChatGPT use. This mediating effect was consistent across sexes but varied with age, being stronger among younger students than among their older counterparts. |

| Ringo (2025) | Tanzania | ChatGPT | Explore the effect of ChatGPT use (GPU) on the doctoral students’ academic research progress (ARP) and the moderating role of hedonic gratification (HEG) in this relationship through the use of PROCESS macro and confirmatory factor analysis. | The study showed that ChatGPT use (GPU) significantly enhances academic research progress (ARP). Also, hedonic gratification (HEG) significantly moderates this relationship, with the positive effect of GPU on ARP intensifying as levels of HEG increase. |

| Aggarwal et al. (2025) | Ghana, South Africa | ChatGPT, Canva, Grammarly AI, Mentimeter, QuillBot, ResearchRabbit, and Scribd | The utilization of AI among academicians in audiology and speech-language therapy (ASLT) |

The study showed that nearly sixty-eight percent of the academicicians used AI tools in their practice, while the major concerns reported in the study were the authenticity of the data, security, the addition of irrelevant information, and incorrect citations. |

| Komba (2024) | Tanzania | ChatGPT | The influence of ChatGPT, an AI-based chatbot, on the digital learning experience of students at Mzumbe University. | The study demonstrated that ChatGPT is widely used in educational contexts and has a positive influence on students’ study habits, academic performance, and understanding of course material. Students appreciated the system’s simplicity, tailored instruments, and the promptness and accuracy of the responses, despite the possibility of isolated mistakes. |

Results

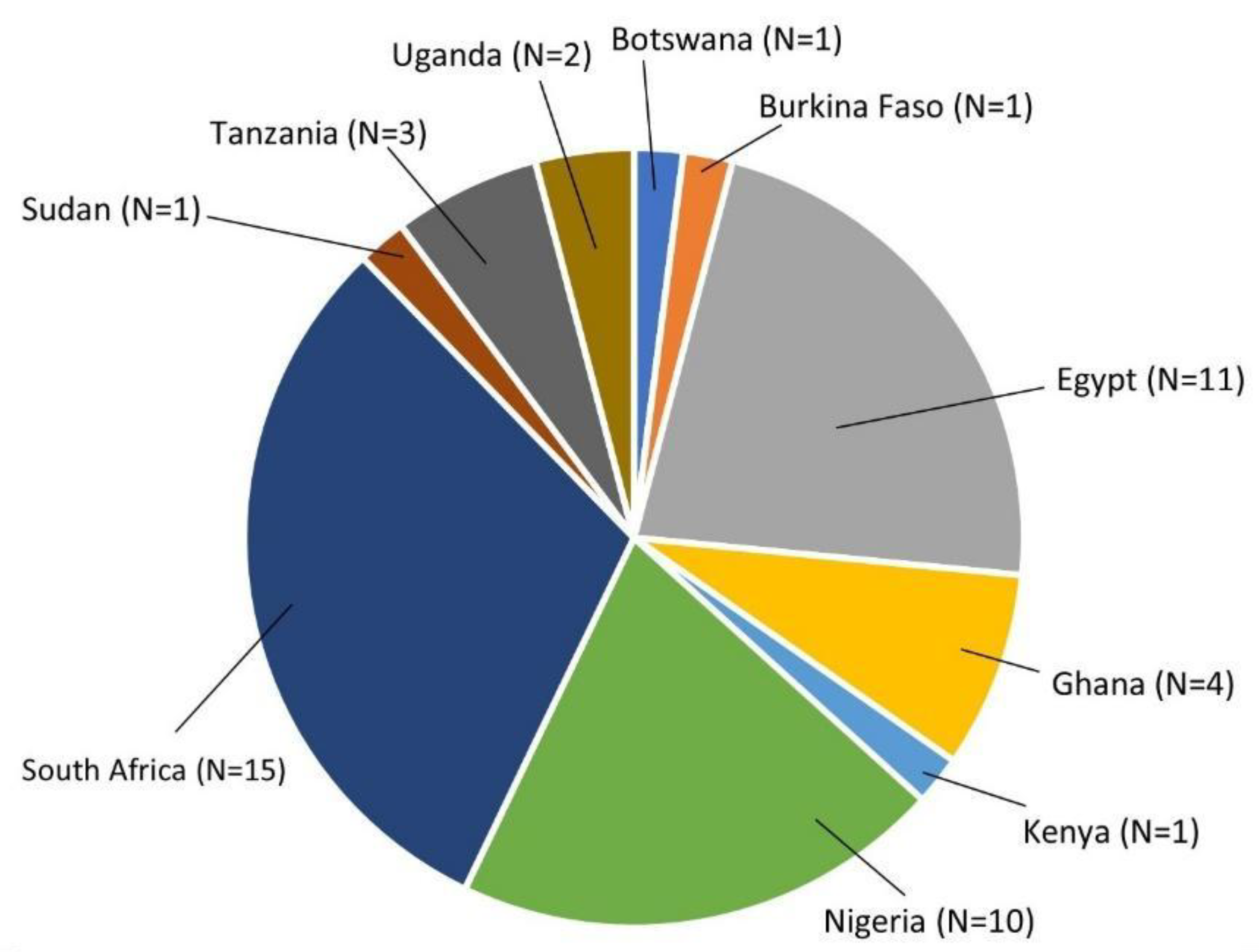

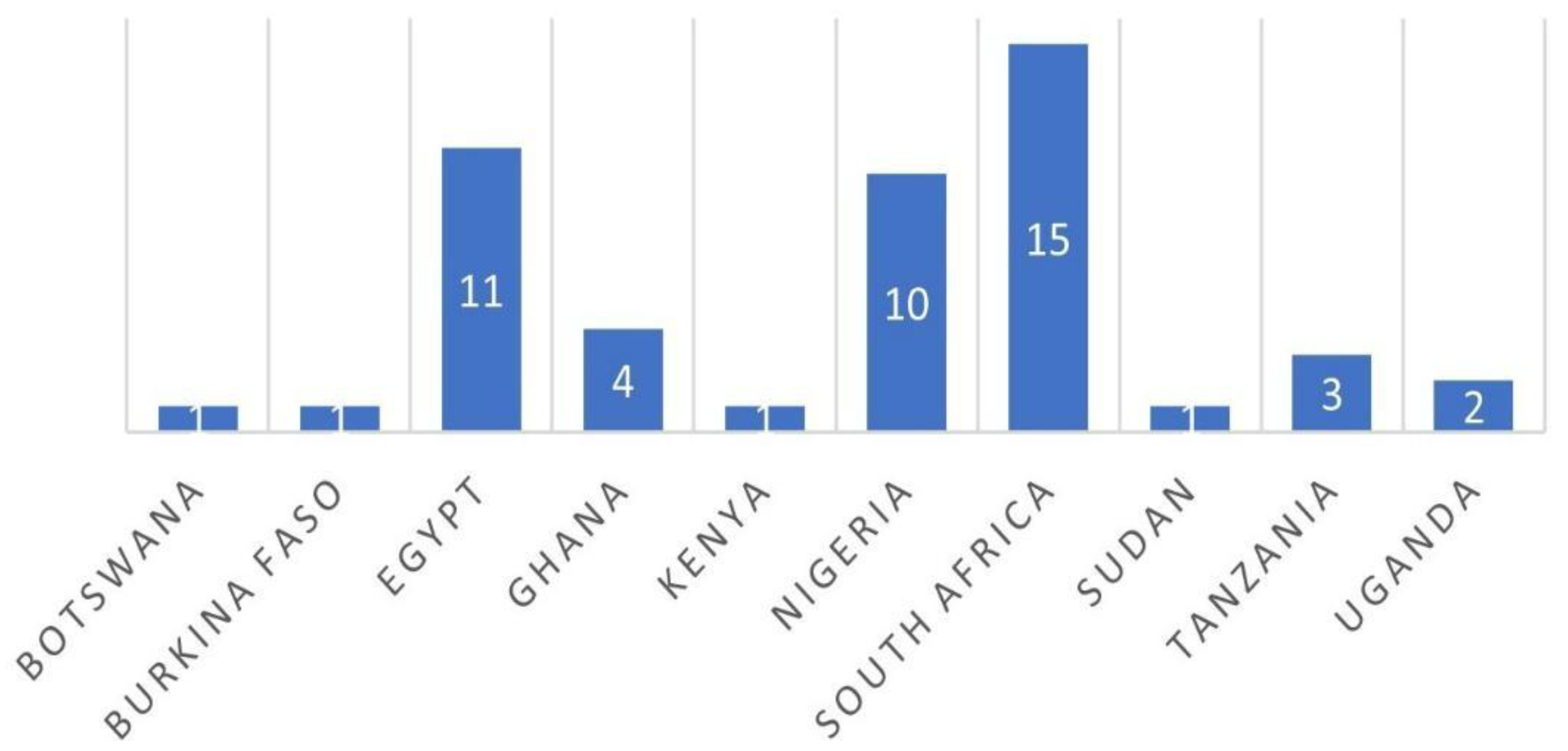

RQ1: Geographic Distribution of Studies on GenAI in African Higher Education

RQ2: Opportunities of GenAI in African Higher Education

RQ3: Ethical Concerns Regarding the Use of GenAI in African Higher Education

RQ4: Preparedness of African Higher Education Institutions for GenAI Adoption

Scholarly Significance of the Study

References

- Abdaljaleel, M. , Barakat, M., Alsanafi, M., Salim, N. A., Abazid, H., Malaeb, D., Mohammed, A. H., Hassan, B. A. R., Wayyes, A. M., Farhan, S. S., Khatib, S. El, Rahal, M., Sahban, A., Abdelaziz, D. H., Mansour, N. O., AlZayer, R., Khalil, R., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Hallit, R., … Sallam, M. A multinational study on the factors influencing university students’ attitudes and usage of ChatGPT. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, A. S. , Farghly, M. I., Sultan, E. A., Abouelmagd, M. E., Ashmawy, Y., & Elsebaie, E. H. Medical students and ChatGPT: analyzing attitudes, practices, and academic perceptions. BMC Medical Education 2025, 25, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, S. Exploring ChatGPT usage amongst female academics and researchers in the academia. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology 2025, 42, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K. , Ravi, R., & Yerraguntla, K. Use of artificial intelligence tools by audiologists and speech-language therapists: an international survey of academicians. Journal of Otology 2025, 20, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. , Subih, M., Fawaz, M., Alnuqaidan, H., Abuejheisheh, A., Naqshbandi, V., & Alhalaiqa, F. Awareness, benefits, threats, attitudes, and satisfaction with AI tools among Asian and African higher education staff and students. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apata, O. E. Ajamobe, J. O., Ajose, S. T., Oyewole, P. O., & Olaitan, G. I. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in enhancing classroom learning: Ethical, practical, and pedagogical considerations. In Proceedings of the 2025 ASEE Gulf-Southwest Annual Conference, University of Texas at Arlington. American Society for Engineering Education. https://peer.asee.org/55084.

- Baha, B. Y. , & Okolo, O. Navigating the ethical dilemma of generative AI in higher educational institutions in Nigeria using the TOE framework. European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology 2024, 12, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo-Anu, D. , Asamoah, D., Amoako, I., & Mahama, I. Exploring student perspectives on generative artificial intelligence in higher education learning. Discover Education 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C. E. , Amory-Mazaudier, C., Barry, B., Chukwuma, V., Cottrell, R. L., Kalim, U., Mebrahtu, A., Petitdidier, M., Rabiu, B., & Reeves, C. eGY-Africa: Addressing the digital divide for science in Africa. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences 2009, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brokensha, S. Kotzé, E., & Senekal, B. A. (2023). AI in and for Africa: A humanistic perspective (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [CrossRef]

- Chauke, T. A. , Mkhize, T. R., Methi, L., & Dlamini, N. Postgraduate Students’ Perceptions on the Benefits Associated with Artificial Intelligence Tools for Academic Success: The Use of the ChatGPT AI Tool. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research 2024, 6, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrinck, C. A tutorial for integrating generative AI in mixed methods data analysis. Discover Education 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daha, E. S. , & Altelwany, A. A. Exploring the Impact of Using - ChatGPT in Light of Goal Orientations and Academic Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Instruction 2025, 18, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, A. , Salami, A., Ajala, O., Adebisi, B., Shodiya, A., & Essien, G. Exploring socio-cultural influences on generative AI engagement in Nigerian higher education: an activity theory analysis. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faloye, S. T. , & Ajayi, N. Understanding the impact of the digital divide on South African students in higher educational institutions. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 2021, 14, 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, N. J. , Jones, S., & Smith, D. P. Generative AI in higher education: Balancing innovation and integrity. British Journal of Biomedical Science 2025, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat-ur-Rehman, I. , & Ibrahim, Y. Exploring factors influencing educators’ adoption of ChatGPT: a mixed method approach. Interactive Technology and Smart Education 2024, 21, 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombana, T. Knowledge generation through open access and generative artificial intelligence. International Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, Letjani, K. P., Kurniawan, K., & Muthaiyah, S. Adoption of ChatGPT in educational institutions in Botswana: A customer perspective. Asia Pacific Management Review 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S. , Soliman, M., Tuomi, A., Alkathiri, N. A., & Al-Alawi, A. N. Drivers of generative AI adoption in higher education through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Technology in Society 2024, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izevbigie, H. I. , Olajide, O., Olaniran, O., & Akintayo, T. A. The ethical use of generative AI in the Nigerian higher education sector. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2025, 25, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, M. M. The influence of ChatGPT on digital learning: experience among university students. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, I. M. , & AbdelMohsen, M. M. Investigating College Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions of Using ChatGPT in Writing Language Essays. Arab World English Journal 2025, 1, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, A. M. , & Kuria, J. Building an AI future: Research and policy directions for Africa's higher education. 2024 IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa) 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphoto, K. B. , Sevnarayan, K., Mohale, N. E., Suliman, Z., Ntsopi, T. J., & Mokoena, D. Advancing Students’ Academic Excellence in Distance Education: Exploring the Potential of Generative AI Integration to Improve Academic Writing Skills. Open Praxis 2024, 16, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Eldakar, M. A. , Khafaga Shehata, A. M., & Abdelrahman Ammar, A. S. What motivates academics in Egypt toward generative AI tools? An integrated model of TAM, SCT, UTAUT2, perceived ethics, and academic integrity. Information Development 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohlake, M. M. , & Mohale, M. A. (2023). Student Assistants’ Perceived Leadership Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Reading and Writing Landscape. [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, M. B. , Jugoo, V., & Adefemi, K. O. Lecturers’ Perceptions on the Integration of Artificial Intelligence Tools into Teaching Practice. Trends in Higher Education 2024, 3, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namatovu, A. , & Kyambade, M. Leveraging AI in academia: university students’ adoption of ChatGPT for writing coursework (take home) assignments through the lens of UTAUT2. Cogent Education 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofem, U. J. , Owan, V. J., Iyam, M. A., Udeh, M. I., Anake, P. M., & Ovat, S. V. Students’ perceptions, attitudes and utilisation of ChatGPT for academic dishonesty: Multigroup analyses via PLS‒SEM. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 30, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O. (2024). Exploring Factors Influencing Nigerian Higher Education Students to Adopt ChatGPT in Learning. In International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT) (Vol. 20). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1461875.pdf.

- Oluwadiya, K. S. , Adeoti, A. O., Agodirin, S. O., Nottidge, T. E., Usman, M. I., Gali, M. B.,... & Zakari, L. Y. U. Exploring artificial intelligence in the Nigerian medical educational space: an online cross-sectional study of perceptions, risks and benefits among students and lecturers from ten universities. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal 2023, 30, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opesemowo, O. A. G. , Abanikannda, M. O., & Iwintolu, R. O. Exploring the potentials of ChatGPT for instructional assessment: Lecturers’ attitude and perception. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research 2024, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramjeeth, S. , & Ramgovind, P. Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools in Higher Education: A Moral Compass for the Future? African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 2024, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravšelj, D. , Keržič, D., Tomaževič, N., Umek, L., Brezovar, N., Iahad, N. A., Abdulla, A. A., Akopyan, A., Segura, M. W. A., AlHumaid, J., Allam, M. F., Alló, M., Andoh, R. P. K., Andronic, O., Arthur, Y. D., Aydin, F., Badran, A., Balbontín-Alvarado, R., Saad, H. Ben, … Aristovnik, A. Higher education students’ perceptions of ChatGPT: A global study of early reactions. PLoS ONE 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringo, D. S. The effect of generative AI use on doctoral students’ academic research progress: the moderating role of hedonic gratification. Cogent Education 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. , Al-Mahzoum, K., Alaraji, H., Albayati, N., Alenzei, S., AlFarhan, F., Alkandari, A., Alkhaldi, S., Alhaider, N., Al-Zubaidi, D., Shammari, F., Salahaldeen, M., Slehat, A. S., Mijwil, M. M., Abdelaziz, D. H., & Al-Adwan, A. S. Apprehension toward generative artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multinational study among health sciences students. Frontiers in Education 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segbenya, M. , Senyametor, F., Aheto, S. P. K., Agormedah, E. K., Nkrumah, K., & Kaedebi-Donkor, R. Modelling the influence of antecedents of artificial intelligence on academic productivity in higher education: a mixed method approach. Cogent Education 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevnarayan, K. Exploring the dynamics of ChatGPT: Students and lecturers’ perspectives at an open distance e-learning university. Journal of Pedagogical Research 2024, 8, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Maintaining the integrity of the South African university: The impact of ChatGPT on plagiarism and scholarly writing. South African Journal of Higher Education 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L. G. , & Fleischer, M. (1990). The processes of technological innovation. Lexington Books.

- van den Berg, G. , & du Plessis, E. ChatGPT and Generative AI: Possibilities for Its Contribution to Lesson Planning, Critical Thinking and Openness in Teacher Education. Education Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, M. M. , Adarkwah, M. A., & Amponsah, S. Why All the Hype about ChatGPT? Academics’ Views of a Chat-based Conversational Learning Strategy at an Open Distance e-Learning Institution. Open Praxis 2023, 15, 214–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, I. M. , Blignaut, R. J., Cranfield, D. J., Tick, A., & Achi, S. El. AI versus tradition: shaping the future of higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 2025, 17, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, I. M. , Cranfield, D. J., Blignaut, R. J., Achi, S., & Tick, A. (2024). Conversational AI in Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Ethical Considerations. INES 2024 - 28th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems 2024, Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Wakunuma, K. , & Eke, D. Africa, ChatGPT, and generative AI systems: Ethical benefits, concerns, and the need for governance. Philosophies 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya’u, M. S. , & Mohammed, M. S. AI-Assisted Writing and Academic Literacy: Investigating the Dual Impact of Language Models on Writing Proficiency and Ethical Concerns in Nigerian Higher Education. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 2025, 13, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, M. N. , David, N., & Abubakar, N. H. Students’ behavioural intention to use content generative AI for learning and research: A UTAUT theoretical perspective. Education and Information Technologies 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A. , Bello, S., Pervin, N., & Tukur, A. K. Implementing a proposed framework for enhancing critical thinking skills in synthesizing AI-generated texts. Thinking Skills and Creativity 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A. , Pervin, N., & Román-González, M. Generative AI and the future of higher education: a threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Generative AI | ("generative AI" OR "large language models" OR "LLMs" OR "ChatGPT" OR "Bard" OR "Gemini" OR "NotebookLM" OR "Consensus app" OR "Meta LLaMA" OR "language models" OR "AI-generated content" OR "natural language generation" OR "text generation") |

| Education Level | ("higher education" OR "tertiary education" OR "universities" OR "college students" OR "postsecondary education" OR "academic institutions") |

| Geographic Location | ("Africa" OR "Sub-Saharan Africa" OR "East Africa" OR "West Africa" OR "North Africa" OR "Nigeria" OR "Ghana" OR "Kenya" OR "South Africa" OR "Ethiopia" OR "Uganda" OR "Tanzania" OR "Egypt" OR "Senegal" OR "Rwanda" OR "Botswana") |

| Thematic Focus | ("opportunities" OR "benefits" OR "impact" OR "use cases" OR "ethics" OR "academic integrity" OR "plagiarism" OR "AI misuse" OR "policy" OR "infrastructure" OR "training" OR "faculty readiness" OR "AI governance") |

| S/N | Country | Frequencies |

| 1 | Botswana | 1 |

| 2 | Burkina Faso | 1 |

| 3 | Egypt | 11 |

| 4 | Ghana | 4 |

| 5 | Kenya | 1 |

| 6 | Nigeria | 10 |

| 7 | South Africa | 15 |

| 8 | Sudan | 1 |

| 9 | Tanzania | 3 |

| 10 | Uganda | 2 |

| Total | 49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).