Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Life Cycle and Biological Background of Vibrio cholerae

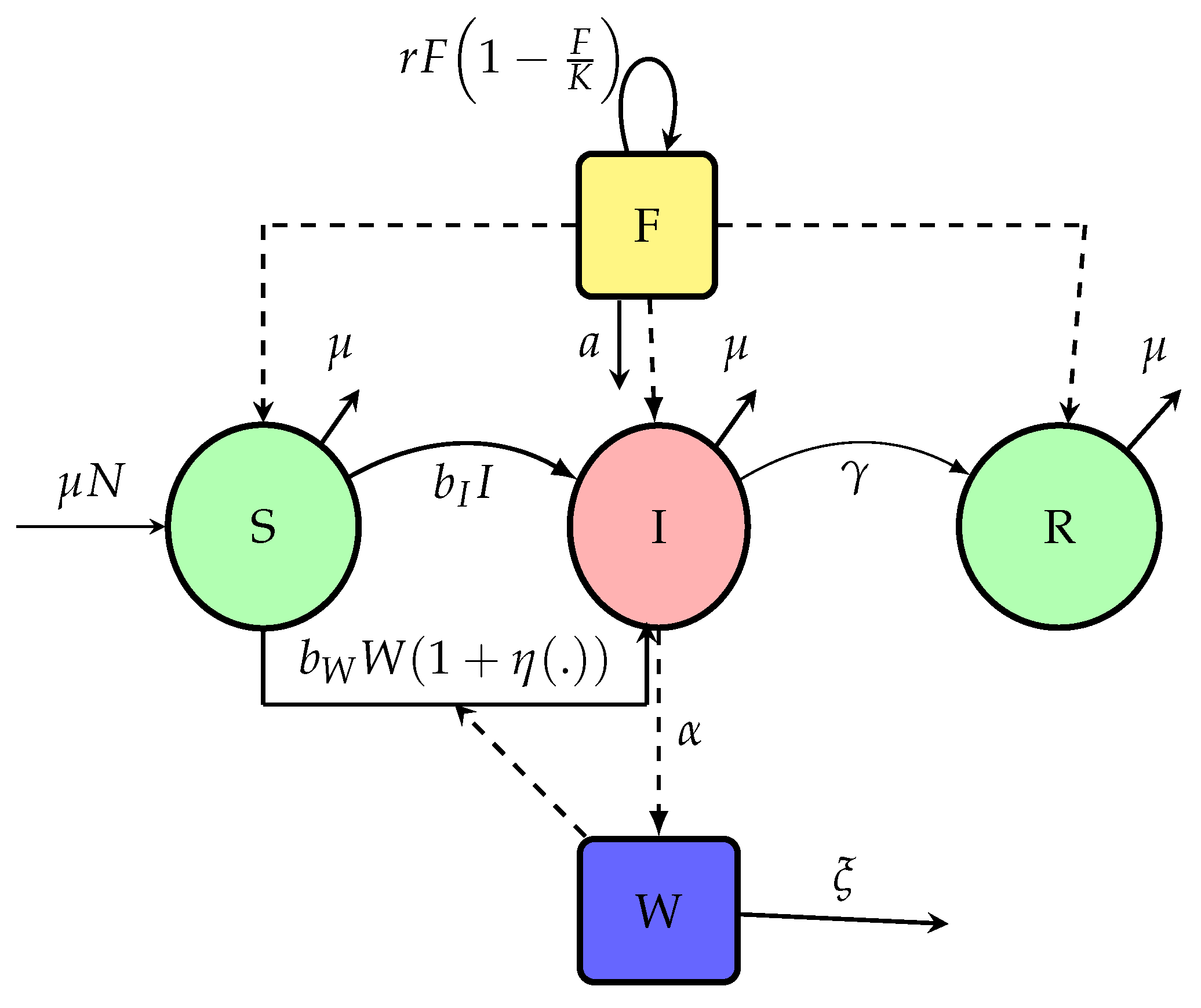

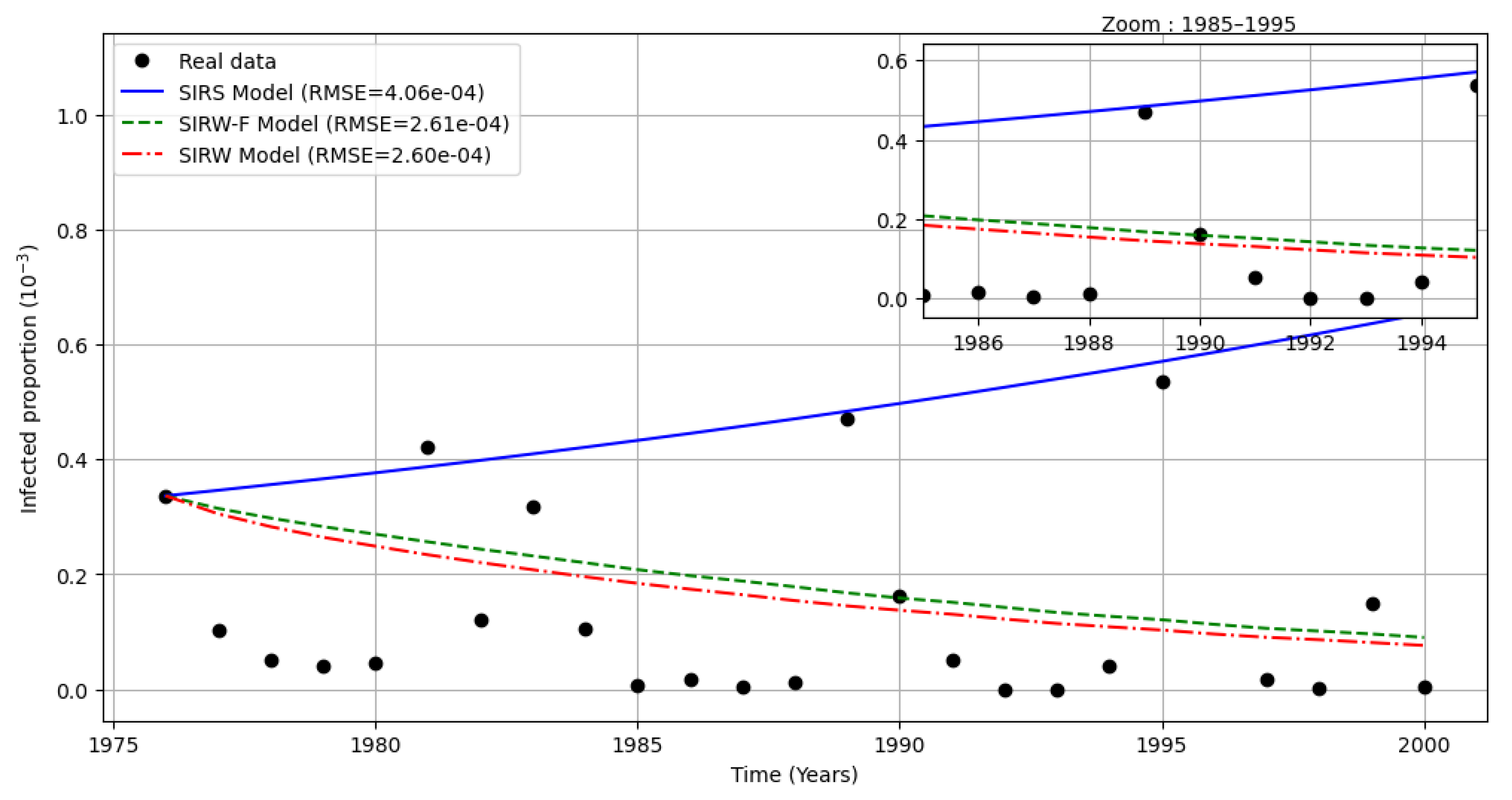

3. A Revision of Old Models: SIWR-F

3.1. Basic Properties of the SIWR-F Model

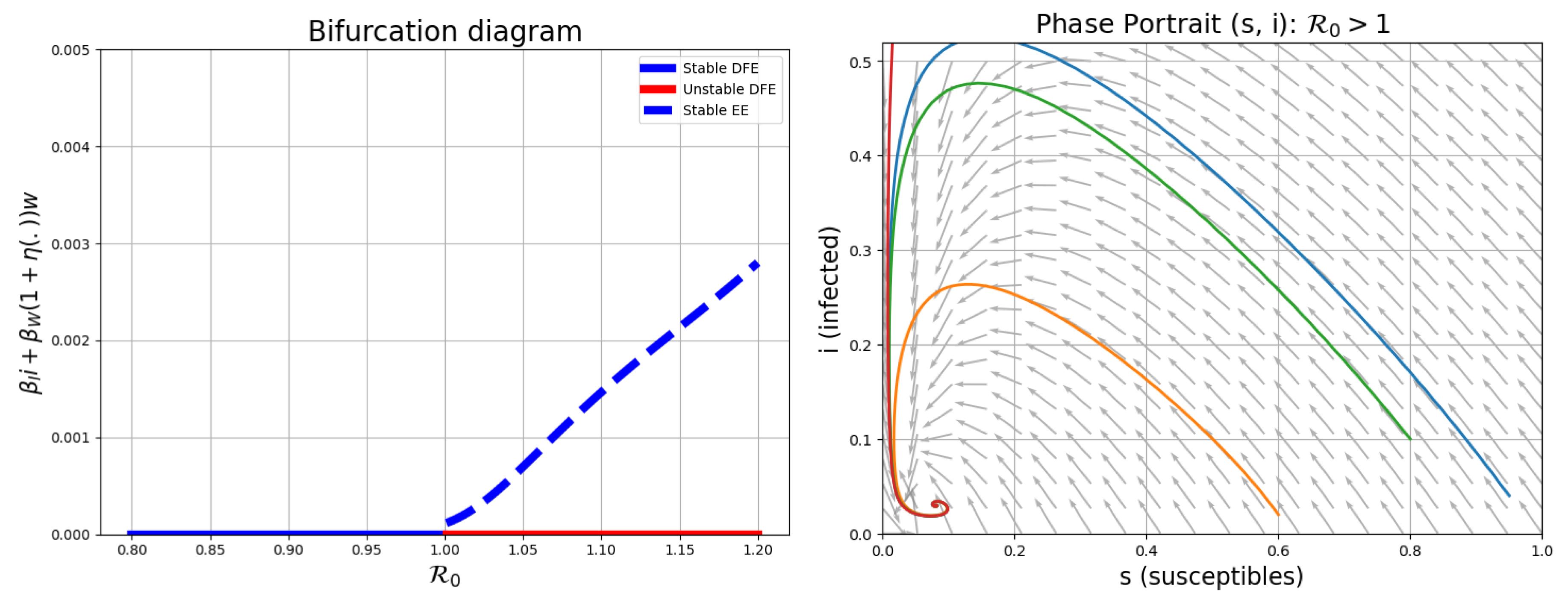

3.2. Stability of the Endemic Equilibrium

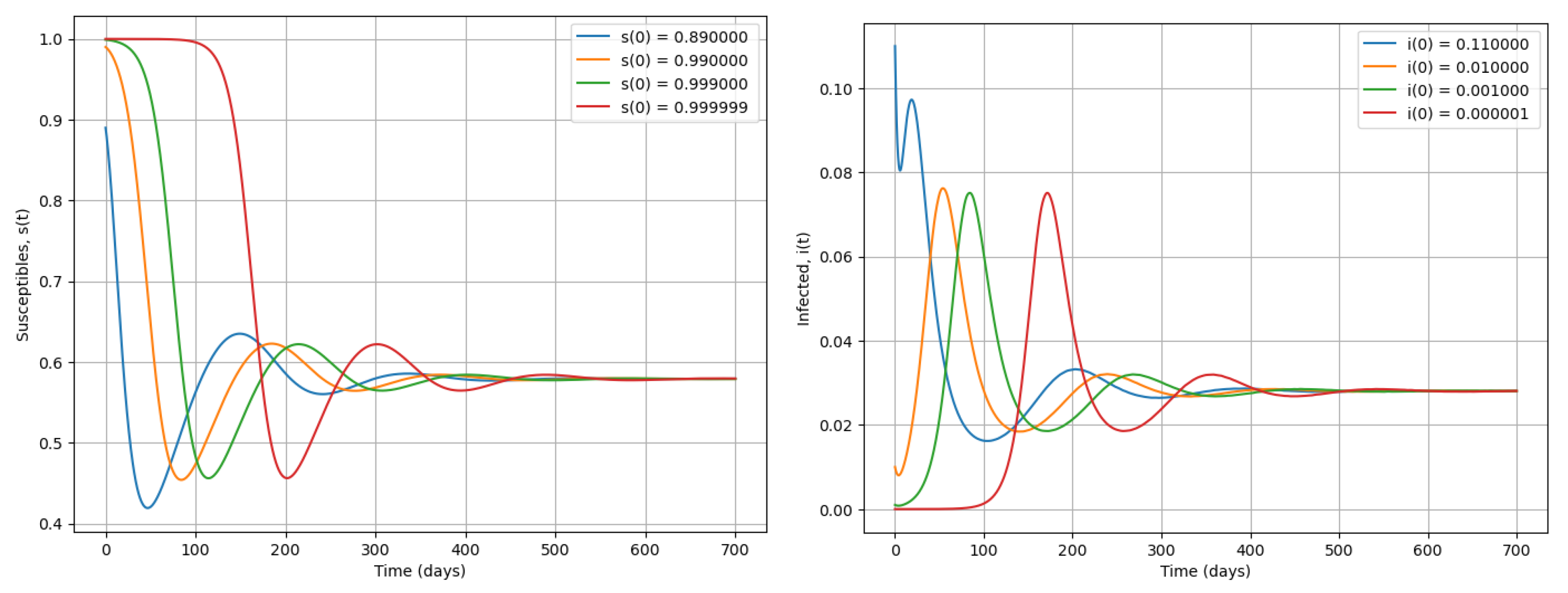

3.3. Comparison of SIR, SIWR and SIWR-F Dynamics

4. An Extension: Multi-Patch Framework

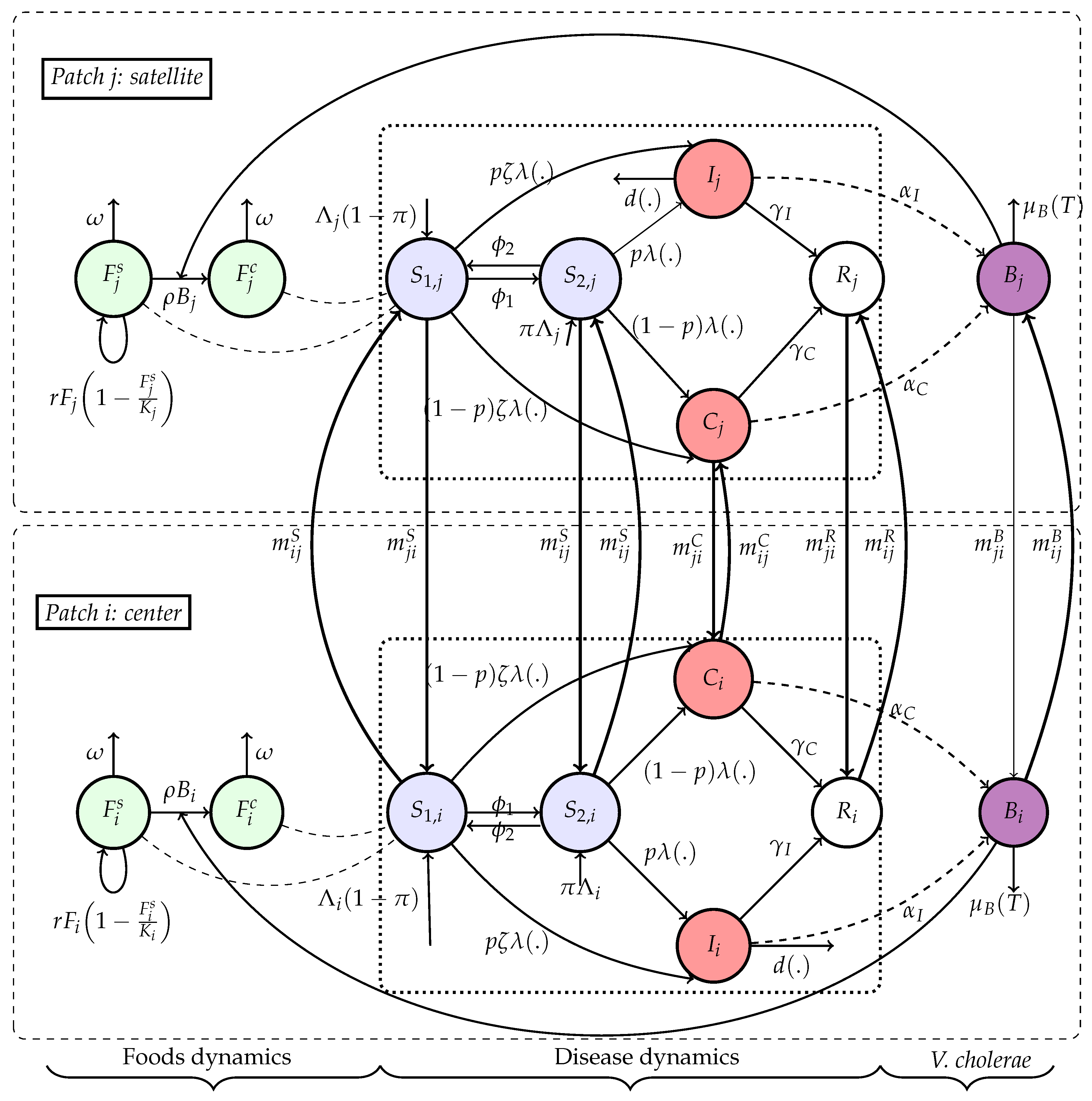

4.1. Model Formulation

- The foodborne transmission channel mediates environmental contamination by V. cholerae, thus capturing both indirect environmental and ingestion-based exposure routes. Then, where is the force of infection with and i.e inside the principal node, the transmission look the standard incidence function () and the mass action law for their satellites ().

- . For the transition to vulnerable individuals, it is assumed that vulnerability appears when the amount of nutriments absorbed (converted into biomass) is below than a threshold K (2000 calories.day−1), i.e , or even . Individuals become vulnerable at rate , with δ the apparition rate of vulnerability.

- (i)

- Individuals who are food insecure or nutritionally vulnerable are more likely to become infected and suffer severe outcomes if exposed to cholera.

- (ii)

- Individuals within a given patch are homogeneously mixed, but inter-patch coupling exists via human mobility and environmental contamination.

- (iii)

- Food contamination arises from bacterial load in the environment and is modulated by local food availability and hygiene conditions.

- (v)

- We assume that food and water ingestion occur jointly during meals, as is common in many societies worldwide. Therefore, waterborne and foodborne exposures are combined into a single ingestion-based transmission route. This simplifies the model compared to classical cholera frameworks where water is treated separately.

- (vi)

- Food contamination is assumed to result primarily from environmental exposure to V. cholerae, reflecting the dominant route of contamination observed in cholera-endemic settings. Direct human contamination (e.g., via food handling) is not explicitly modeled, as its contribution is generally secondary compared to water-related pathways.

- Direct human-to-human transmission, proportional to the prevalence of infectious individuals.

- Food-borne transmission through ingestion of contaminated food, governed by a saturation function of disease.

5. Mathematical Analysis

5.1. Basic Properties of (17)

- Movements within the same patch are ignored ().

- In this paper, authors assimilate vulnerable individuals at individuals in food insecurity.

- Generally, when we have patch model in case without movement (), using [3] the basic reproduction number may be given by:

5.2. Disease-Free Equilibrium

- 1.

- A state of equilibrium with susceptible individuals but without food.

- 2.

- A state of equilibrium where there are individuals and food.

5.3. Basic Reproduction Number

6. Model Application

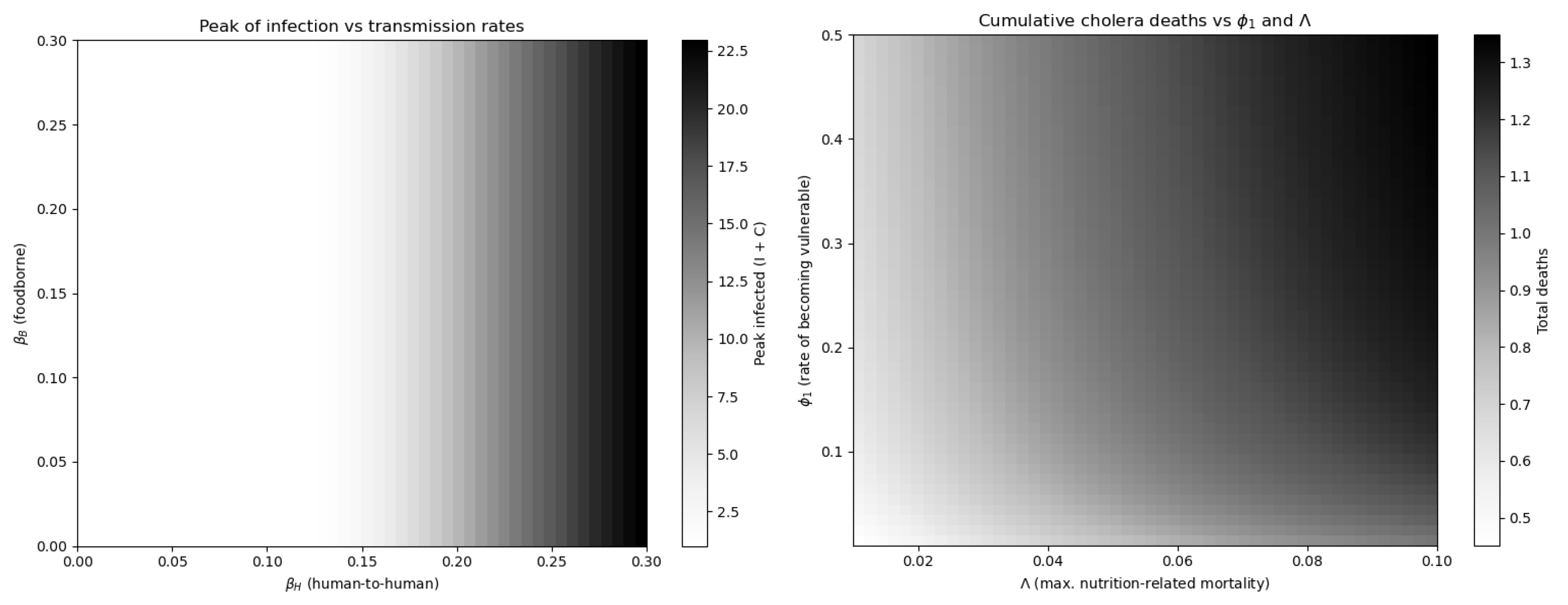

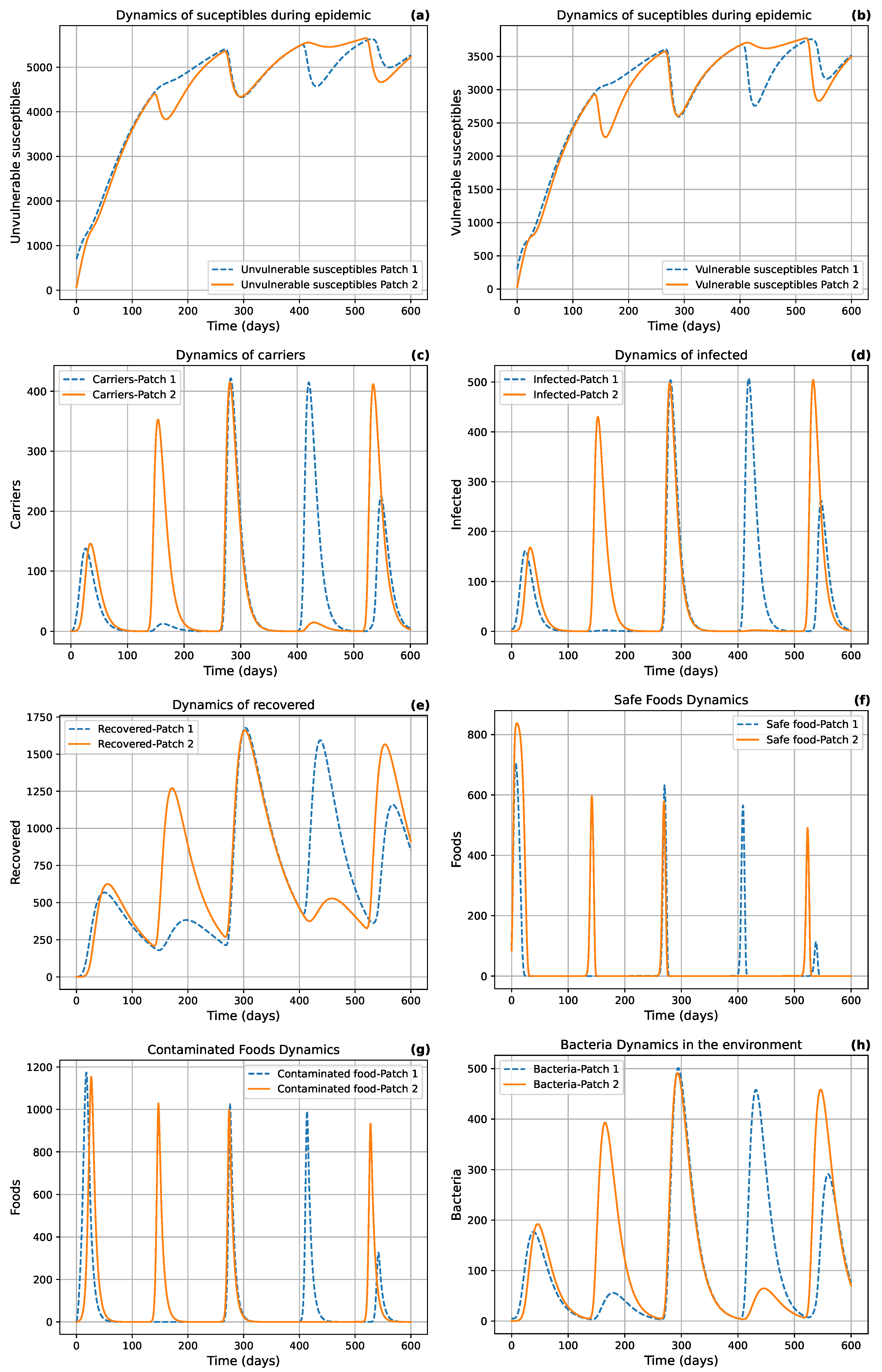

6.1. Numerical Simulations

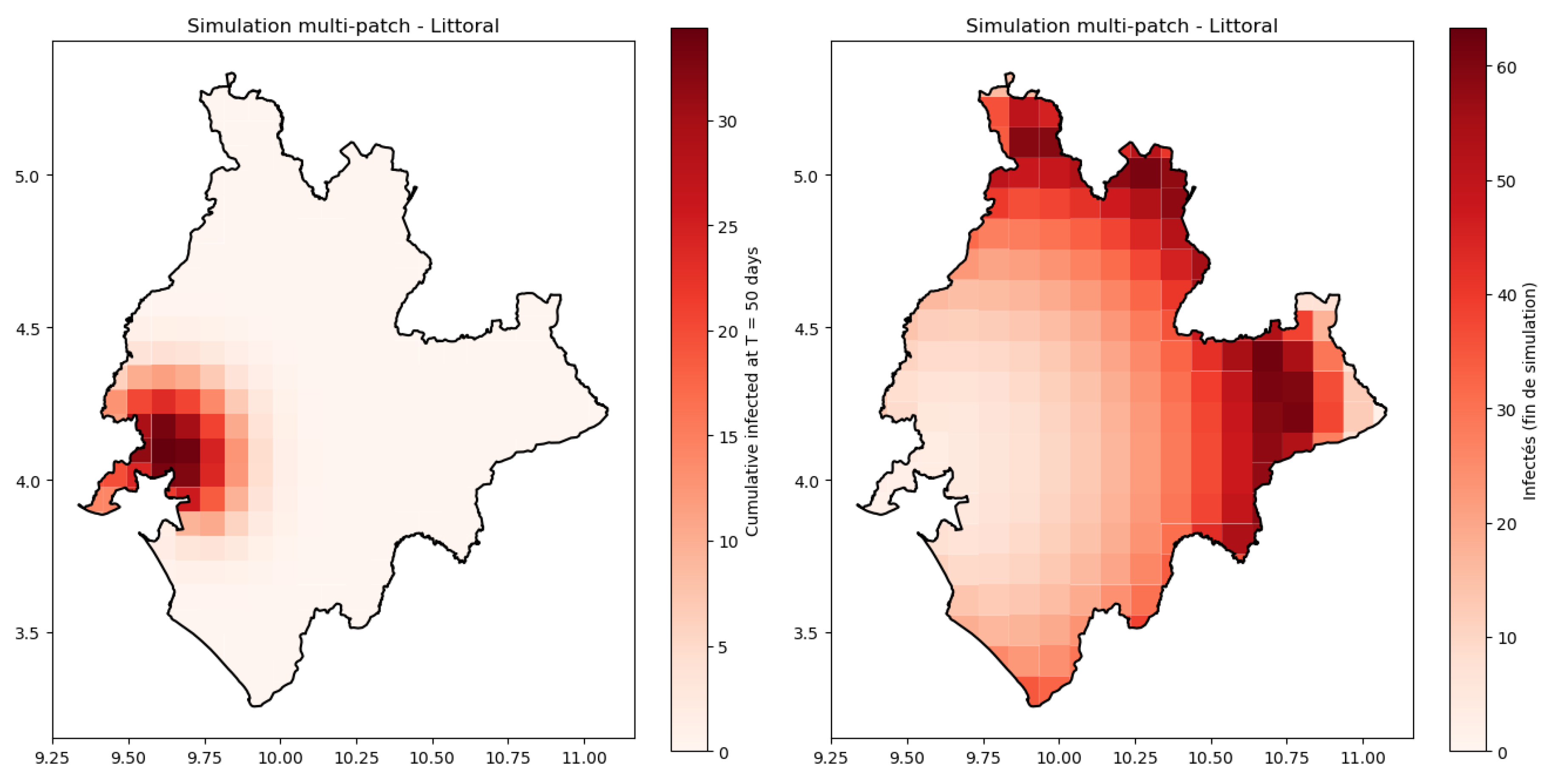

6.2. Case Study of Littoral (Douala) and Its Surroundings Areas

- a central node representing Douala,

- and three surrounding patches: Bonaberi, Bomono, and Yassa connected to Douala through human movement and food exchange.

- , where the temperature is in degree Celsius. represents the dependency on temperature, ( according to [4]), and correspond respectively to the maximum and mean temperature of Douala city over the 20 years.

7. Discussions and Perspectives

Appendix A. Mathematical Proofs and Tools

-

Step 1: linearization on the disease-free boundary and the invasion criterion.Consider the infectious subsystem when s and f are frozen at the boundary values and . The linearization at the DFE restricted to isLet be the characteristic polynomial. Evaluating at we getHence if and only if , i.e. . But as , so if there exists a positive real root of . Thus A has a positive eigenvalue . The corresponding eigenvector can be chosen strictly positive because off-diagonal entries of A are nonnegative and A is cooperative on .Therefore is equivalent to the linearized infectious subsystem at the DFE having exponential growth (positive principal eigenvalue), i.e. the DFE is linearly unstable w.r.t. infectious perturbations.Step 2: local exponential growth from small infections (linear comparison). Because K is compact and the vector field is continuous, there exists a neighborhood of the DFE boundary point such that, for all with , (for some small ), the Jacobian matrix of the -subsystemsatisfies(componentwise) for some small . (This follows from continuity of the entries of J in .) The inequality is understood entrywise; the system for is cooperative (all off-diagonal infection/transmission terms are nonnegative), hence one may apply the comparison principle for cooperative linear systems.Fix . By continuity there exists so that whenever and the inequality above holds. Define the exit timeOn the time interval the vector satisfies the differential inequality (entrywise)By standard linear comparison, we then have forBecause A has principal eigenvalue , the matrix has a positive growth exponent . Hence there exists (independent of sufficiently small initial infectious perturbations) and a positive vector such thatfor some proportional to the size of the initial condition. In particular, any nontrivial initial infection (no matter how small) is amplified while the trajectory remains in the neighborhood U.Two remarks are in order: (i) for initial data not already in U, after some finite time the solution will enter a compact set where the same local argument works (use that solutions cannot stay forever in a small neighborhood of the boundary without the linearization forcing them away); (ii) the cooperative structure ensures the constants can be chosen uniformly for all small initial infectious states in a small ball (uniformity needed for the next step).

-

Step 3: uniform weak persistence.From Step 2 one deduces there exists and such that for every solution with sufficiently small,By compactness of the absorbing set K and continuity of the flow, the threshold can be chosen uniformly for all initial data in the compact set . This is the assertion of uniform weak persistence: there exists so that for every solution with we have .

-

Step 4: upgrade to uniform strong persistence.We now use a standard result from persistence theory (see e.g. the persistence theorems of Hale & Waltman, Butler & Waltman, or the corresponding theorems in Thieme’s framework): for a semiflow on a compact positively invariant set K, if the boundary set is invariant and is a uniform weak repeller (equivalently the system is uniformly weakly persistent), and if satisfies a mild compactness/acyclicity condition (no complicated chain-recurrent dynamics connecting boundary invariant sets), then weak uniform persistence implies strong uniform persistence. In our situation the semiflow is defined on the compact set K, the boundary is invariant (if then ), and linear instability of the DFE together with the compactness of K rules out the pathological boundary chain-recurrence required to block the upgrade (this is exactly the set of hypotheses used in [24] Theorem 1.3).Hence there exists such that for every solution with ,This completes the proof of Theorem 3.1.

Appendix B

Appendix C. Theorem of Kamgang and Sallet

- : Model system is defined in a positively invariant subset D of Ω and its dissipative in D.

- : The sub-system is globally asymptotically stable at the equilibrium in the canonical projection of Ω on D.

- : The matrix is Metzler (A Metzler matrix is a matrix with all-diagonal entices non-negative and irreducible for any given x ∈ D.

- : There exists an upper bound matrix for ; with the property that if (i.e: ) then, for any (i.e. The points where the maximum is realized are contained in the disease free sub-manifold).

- : The largest real part of the eigenvalue of denoted by has to be negative.

Appendix D. Theorem of Castillo-Chavez and Song

References

- Anderson, Roy M. and Robert M. May. 1991. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Arino, Julien, N. Bajeux, and S. Kirkland. 2019. Number of source patches required for population persistence in a source-sink metapopulation. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 81(6), 1916–1942. [CrossRef]

- Arino, Julien and P. Driessche. 2004, 09. A multi-city epidemic model. Mathematical Popultion Studies 10, 175–193. [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzo, Enrico, Lorenzo Mari, L. Righetto, , Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 2010. Modeling cholera epidemics: the role of waterways, human mobility and sanitation. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 7(50), 321–333. [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Zulfiqar A., Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 2008. What works? interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The Lancet 371(9610), 417–440. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Chavez, Carlos and Baojun Song. 2004. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 1(2), 361–404. [CrossRef]

- Che, Eric Ngang, Yeona Kang, and Abdul-Aziz Yakubu. 2019. Risk structured model of cholera infections in cameroon. Mathematical Biosciences 320, 108–124. [CrossRef]

- Codeço, Cláudia T. 2001. Endemic and epidemic dynamics of cholera: the role of the aquatic reservoir. BMC Infectious Diseases 1(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Colwell, Rita R. and Anwar Huq. 2004. Environmental reservoir of vibrio cholerae: the causative agent of cholera. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1025, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- de Magny, Constantin, R. Murtugudde, M. R. Pascual, et al. 2008. Environmental signatures associated with cholera epidemics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(46), 17676–17681.

- Eisenberg, Marisa C., Zhisheng Shuai, Joseph H. Tien, and Pauline van den Driessche. 2013. A cholera model in a patchy environment with water and human movement. Mathematical Biosciences 246(1), 105–112. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2021. The state of food security and nutrition in the world. FAO/IFAD/UNICEF/WFP/WHO Joint Report.

- Guerrant, Richard L., Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 2013. The impoverished gut–a triple burden of diarrhoea, stunting and chronic disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology-Hepatology 10(4), 220–229. [CrossRef]

- Hartley, David M., Jonathan G. Morris, and David L. Smith. 2006. Hyperinfectivity: a critical element in the ability of v. cholerae to cause epidemics? PLoS Medicine 3(1), e7. [CrossRef]

- Huq, Anwar, Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 1995. Association of vibrio cholerae with the marine plankton in the aquatic environment. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 61, 4022–4024.

- Kaper, J. B., J. G. Morris, and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cholera. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 8(1), 48–86. [CrossRef]

- Korobeinikov, Andrei and Graham Wake. 2002. Lyapunov functions and global stability for SIR, SIRS, and SIS epidemiological models. Applied Mathematics Letters 15(8), 955–961. [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, J.P. 1976. The Stability of Dynamical Systems. CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Lipp, Erin K., Anwar Huq, and Rita R. Colwell. 2002. Effects of global climate on infectious disease: the cholera model. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 15(4), 757–770. [CrossRef]

- Lizárraga-Partida, M. L., Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 2009. Association of vibrio cholerae with plankton in coastal areas of mexico. Environmental Microbiology 11(1), 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Merrell, D. Scott, Susan M. Butler, Firdausi Qadri, Nadia A. Dolganov, Ahsfaqul Alam, Mitchell B. Cohen, Stephen B. Calderwood, Gary K. Schoolnik, and Andrew Camilli. 2002. Host-induced epidemic spread of the cholera bacterium. Nature 417(6889), 642–645. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Eric J., Jason B. Harris, J. Glenn Morris Jr, Stephen B. Calderwood, and Andrew Camilli. 2009. Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nature Reviews Microbiology 7(10), 693–702. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, James D. 2005. The viable but nonculturable state in bacteria. Journal of Microbiology 43(Special No), 93–100.

- Thieme, Horst R. 1993. Persistence under relaxed point-dissipativity (with application to an endemic model). SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis 24(2), 407–435.

- Tien, Joseph H. and David JD. Earn. 2010a. Multiple transmission pathways and disease dynamics in a waterborne pathogen model. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 72(6), 1506–1533. [CrossRef]

- Tien, Joseph H. and David J. D. Earn. 2010b. Multiple transmission pathways and disease dynamics in a waterborne pathogen model. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 72, 1506–1533. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 2022. Severe acute malnutrition: A global emergency. Global Nutrition Report.

- van den Driessche, P. and J. Watmough. 2002. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical Biosciences 180, 29–48. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2025. World development indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed: 2025-08-11.

- World Health Organization. 2022. Global health observatory data repository by category: Cholera. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.174?lang=en. Accessed: 2025-08-11.

| Symbol | Biological meanings | Value | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food-related parameters | ||||

| r | Growth rate of available food | 0.1-0.5 | Assumed | |

| K | Food holding capacity | [5] | ||

| a | Nutrition/degradation rate | [0.5,1] | Assumed | |

| Bacteria-related parameters | ||||

| Contact rate with V. cholerae in the environment | [0.1,0.3] | [8] | ||

| Death rate of V. cholerae in water reservoir | [0.1,1] | [23] | ||

| Production of V. cholerae by infected | [23] | |||

| Human-related parameters | ||||

| Contact rate with V. cholerae from the human-to-human pathway | [0.05,0.15] | [4] | ||

| Natural death rate of humans | World Bank Data | |||

| Recovery rate | [13] | |||

| Variables of system (1) | ||||

| S(t) Susceptible individual at time t | ||||

| I(t) Infected individual at time t | ||||

| R(t) Recovered individual at time t | ||||

| W(t) Pathogen concentration in water reservoir | ||||

| F(t) Biomass/Food density at time t | ||||

| Symbols | Biological meanings | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptible without food insecurity | Number | |

| Susceptible in food insecurity | Number | |

| Number of asymptomatic | Number | |

| Number of infected | Number | |

| Recovered individuals | number | |

| Available healthy foods | calories | |

| Contaminated foods | calories | |

| Number of bacteria in environment | cells.ml−1 |

| Symbols | Biological meanings | Value | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate of available food | 0.1-0.5 | Assumed | ||

| K | Critical limit of food consumption | 2000 | [12] | |

| Food holding capacity | 2500-3000 | Assumed | ||

| Contact rate with V. cholerae in the environment | 0.1-0.3 | [8] | ||

| Contact rate with V. cholerae from the human-to-human pathway | 0.05-0.15 | [4] | ||

| Half saturation rate for V. cholerae | Assumed | |||

| Half saturation rate for foods | Assumed | |||

| Mortality rate due to disease | 0.02-0.03 | WHO, 2022 | ||

| Transition rate to vulnerable individuals | 0.1-1 | Assumed | ||

| Natural mortality rate | World Bank | |||

| Mortality rate for V. cholerae | 0.1-1 | Assumed | ||

| Apparition rate of vulnerability | 0.01-0.1 | Assumed | ||

| Production of V. cholerae by asymptomatic | Assumed | |||

| Production of V. cholerae by infected | Assumed | |||

| a | Nutrition rate | 0.5-1 | Assumed | |

| e | Conversion rate of food consumption | Assumed | ||

| Recovered rate for asymptomatic individuals | 0.14-0.2 | Assumed | ||

| Recovered rate for infected individuals | 0.1-0.14 | Assumed | ||

| Migration to patch i from patch j | 0.1-0.4 | Assumed | ||

| Rate of V. cholerae - foods association | 0.37 | Assumed | ||

| Natural decay for contaminated foods | 0.15 | Assumed | ||

| Colonization coefficient of bacteria | 0.3-0.5 | Assumed | ||

| p | Proportion of direct infectious state | 0.6 | WHO, 2022 | |

| Rate to contract infection for individuals living in food security | 0.42 | Assumed | ||

| Recruitment rate at patch i | Assumed | |||

| Proportion of recruitment for vulnerable | 0.3-0.5 | Assumed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).