1. Introduction

With the widespread deployment of 5G networks and the ongoing development of 6G technologies, communication systems are advancing toward higher data rates, lower latency, and stronger security. In light of the growing severity of information security challenges in future mobile communications, quantum communication—particularly Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)—has emerged as a pivotal technology for enabling next-generation secure networks [

1]. QKD, grounded in the no-cloning theorem and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, allows theoretically unconditional secure key exchange, ensuring absolute confidentiality of shared keys between communication parties [

2,

3]. QKD demonstrates strong potential for applications in high-security domains, including military communications [

4], financial data protection [

5], and confidential government communications [

6].

As QKD network technology matures, its architecture is evolving from simple point-to-point links to more complex topologies supporting multi-hop routing, multi-user access, and concurrent services. Currently, QKD network architectures can be broadly categorized into three types: optical node-based, quantum node-based, and trusted-relay node-based [

7]. Optical and quantum node networks generate point-to-point quantum keys by establishing temporary quantum channels between users on demand. While these approaches support multi-user and long-distance key distribution in principle, they are constrained by signal attenuation and the immaturity of critical technologies such as quantum memory. As a result, optical node QKD networks are mainly suited for local-area applications, and quantum node QKD networks remain in the experimental stage. In contrast, trusted-relay QKD networks perform key relaying at the upper layer of quantum key generation, enabling multi-user, long-distance key distribution via hop-by-hop forwarding. Due to its relative technological maturity and scalability, this architecture has become the most practical approach for current large-scale QKD network deployments [

8].

At the current stage of development, a critical challenge facing trusted-relay QKD networks is efficient scheduling and stable transmission of key resources through appropriate routing strategies under complex physical conditions and limited resources. Unlike traditional communication networks that primarily optimize metrics such as latency and bandwidth, the performance of QKD links is fundamentally governed by physical-layer factors. These factors result in inherently low key generation rates, pronounced spatial heterogeneity, and significant temporal variability [

9]. Consequently, resource management in such networks faces challenges that can be broadly categorized into the following three aspects:

Quantum key generation is fundamentally constrained by physical factors such as quantum bit error rate (QBER) and channel attenuation, leading to substantial heterogeneity in link performance. Links with insufficient capacity are unable to sustain frequent transmissions, which can cause local key pool exhaustion and disrupt services.

Key demand is tightly coupled with dynamic traffic patterns and often exhibits unpredictable and bursty behavior. During traffic surges or directional load concentrations, key resources on specific paths can be rapidly exhausted. In addition, imbalanced path selection and uneven request distribution may cause localized link overuse, leading to resource bottlenecks and reduced transmission efficiency.

Existing routing strategies, such as shortest-path-first and maximum residual key, rely on static or instantaneous network states without modeling key pool dynamics. This limits their adaptability to resource fluctuations, leading to greater key transmission failures and degraded network performance. Routing in QKD network must intelligently adapt to dynamic conditions, integrating key generation, consumption, and control feedback to ensure efficient and reliable key delivery.

The primary contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- 1.

We propose a resource-aware key scheduling framework for trusted-relay QKD networks that integrates real-time link state monitoring, online Q-Learning–based adaptive routing, and multidimensional path feasibility verification to ensure dynamic congestion avoidance and stable key distribution under time-varying traffic and network conditions.

- 2.

We constructed a discrete-time model to characterize key dynamics, where the normalized occupancy ratio was uniformly discretized into states, and the action space was defined by adjacent neighbor sets. A composite reward function, integrating occupancy deviation, consumption penalty, and generation incentive, enabled adaptive balancing between network load and key resource replenishment.

- 3.

The simulation results demonstrate the proposed method substantially enhances trusted-relay QKD network performance by improving transmission efficiency, optimizing resource utilization, and effectively mitigating congestion to ensure robust stability under high-load conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work, followed by the presentation of the system model and fundamental mechanisms in

Section 3.

Section 4 formulates the problem and elaborates on the design of the Q-learning model. Final simulation results and comprehensive performance discussions are provided in

Section 5 before the paper concludes with insights and future directions in Section 6.

2. Related Work

With the continuous expansion of trusted-relay QKD network, the demands for efficient quantum key resource allocation and stable service delivery have increased significantly. Integrating efficient and adaptive routing algorithms has become essential for achieving balanced load distribution and improving overall network service capacity. To support ongoing research and practical deployment of trusted-relay QKD network, a variety of routing algorithms have been proposed.

The Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) protocol, a classical link state routing mechanism, was first applied in the experimental DARPA QKD network [

10]. Building on this foundation, the SECOQC project modified OSPF to address the specific demands of relay path selection in QKD network [

11]. The Tokyo QKD network adopted a hybrid routing strategy combining static and dynamic elements. Despite its limited scale and relatively simple dynamic algorithms, it effectively coordinated data and key transmission by incorporating link quality and key generation rate into node configurations [

12]. In a larger deployment, the Beijing–Shanghai QKD backbone implemented an enhanced OSPF protocol, integrating real-time metrics such as key generation rate, link reliability, and relay node security to improve path selection adaptability [

13]. As network architectures and service demands become more complex, recent efforts have focused on advanced dynamic routing strategies. For example, Bi et al. [

14] proposed an environment-sensitive algorithm that balances key generation and traffic load across diverse topologies. Yu et al. [

15] further introduced a hierarchical routing framework that integrates OSPF with quantum key management, significantly enhancing scalability and robustness.

To enhance key-awareness in routing, reference [

16] incorporated the effective key volume of each link into OSPF-based path computation. Expanding on this, [

17] jointly considered both the current key pool size and the key generation rate, enabling more precise and dynamic resource scheduling. To mitigate key exhaustion at bottleneck links, [

18] introduced a hierarchical routing-based path optimization method to enhance transmission flexibility and overall performance. Reference [

19] selected optimal routes using a combined metric of physical distance and key availability, while reference [

20] incorporated controlled randomness to increase path diversity and robustness. Reference [

21] developed a multifactor link cost model in conjunction with a key-aware routing strategy, significantly improving the key exchange success ratio. Within the realm of multipath routing, Han et.al [

22] designed a multi-user routing algorithm aimed at optimizing quality of service (QoS) in optical QKD networks. Reference [

23] presented a dynamic routing scheme comprising a Hello protocol, routing algorithm, and link state update mechanism to adapt to evolving network conditions. Furthermore, Reference [

24] implemented a node labeling strategy for multipath selection, effectively preventing routing loops and node conflicts, thus ensuring routing stability and efficiency.

Given the structural similarities between trusted-relay QKD network and Wireless Ad Hoc Networks (WANETs)—notably their dynamic topologies—several studies have adapted classical WANET routing protocols to address frequent link state changes in QKD scenarios [

25,

26]. In quantum key distribution over Optical Networks (QKD-ON), joint routing, wavelength, and time-slot assignment (Routing and Wavelength Assignment/Routing and Resource Assignment, RWA/RRA) poses significant complexity beyond that of traditional optical networks [

27,

28]. To cope with this, key-on-demand strategies based on software-defined optical networks and key pool mechanisms were introduced for adaptive resource management [

29]. Time scheduling models have also been developed to coordinate provisioning across domains [

30], while heuristic RWA/RRA algorithms using enhanced node structures and auxiliary graphs help minimize key waste and avoid untrusted relays [

31]. For secure multicast, distributed subkey relay trees have been designed to support efficient delivery of one to many keys [

32]. Research on routing protocols for QKD networks has also been conducted from various perspectives, including adaptation to different types of QKD networks [

33,

34], enhancement of security [

35], and suppression of crosstalk [

36].

While considerable advancements have been made, fundamental challenges remain unresolved. Most routing protocols rely on instantaneous link states, lacking foresight into resource dynamics and risking unstable or bottleneck-prone paths. Many link cost functions are based on fixed parameters, limiting adaptability to changing conditions. Resource allocation approaches often emphasize local, short-term optimization, neglecting long-term efficiency and cross-task coordination. Addressing these issues requires proactive path selection under dynamic resource conditions and the development of intelligent, forward-looking routing mechanisms to enhance QKD network performance.

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

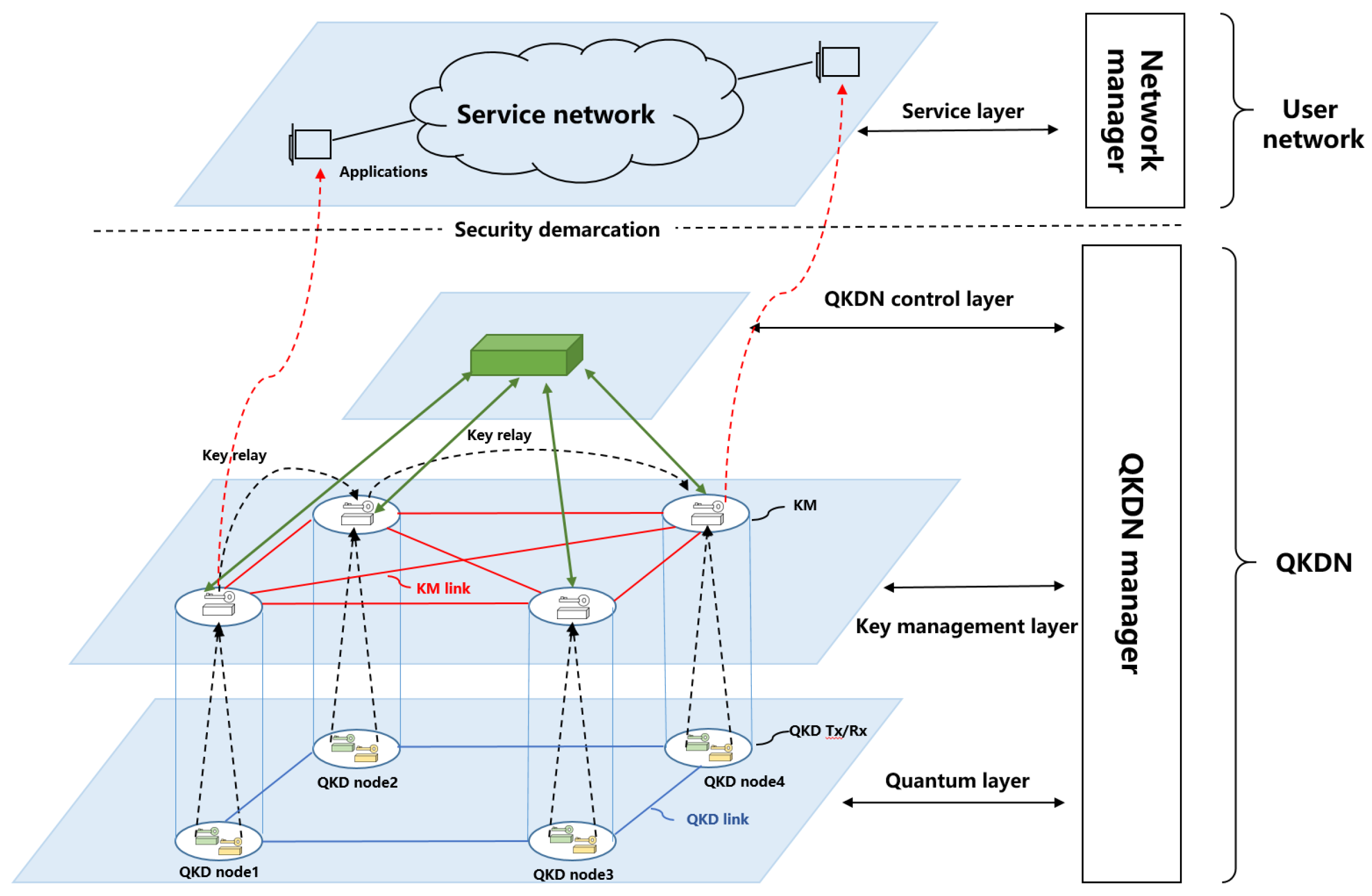

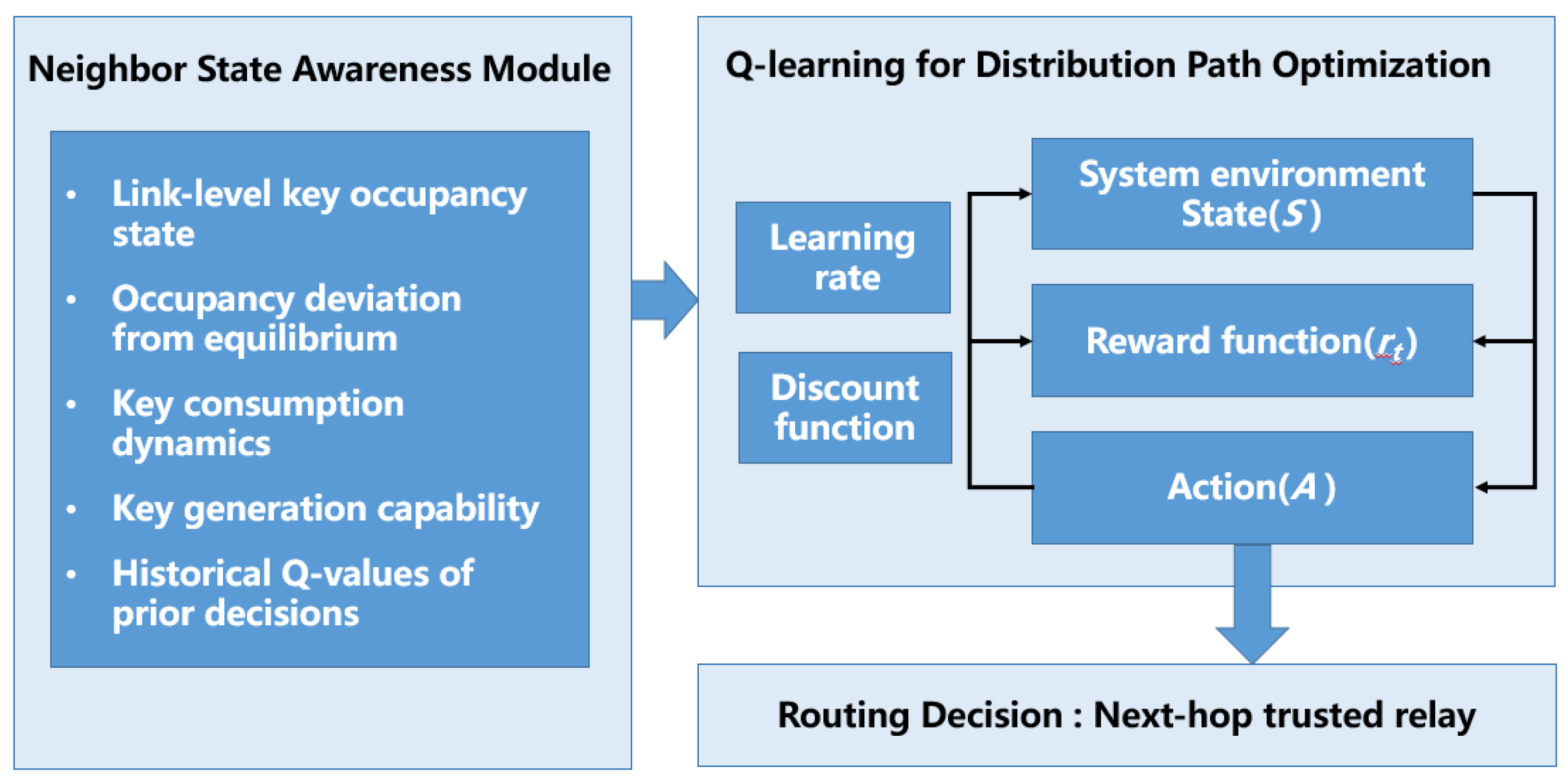

To address the challenges of uneven resource distribution and dynamically changing key consumption in trusted relay QKD networks, we propose a Q-learning-based key scheduling framework for adaptive and resource-aware path selection. As shown in

Figure 1, the framework comprises three key modules. The

Neighbor State Awareness Module continuously monitors adjacent links, extracting critical features such as key occupancy rate, deviation from ideal balance, consumption rate, and generation capability, constructing a comprehensive state representation. The scheduler adopts an episodic online Q-learning framework, where each routing request simultaneously evaluates the current policy and updates the Q-table based on immediate rewards. As the core decision-making mechanism, the

Online Q-learning scheduler is driven by a reward function designed to balance resource distribution uniformity and consumption efficiency, penalizing over-concentration and rapid depletion while promoting stable replenishment. Finally, the

Routing and Validation Module generates trusted relay paths based on the learned policies, ensuring compliance with network topology and current resource conditions to achieve efficient and stable key distribution.

3.1. QKDN Model and Constraints

3.1.1. Network Topology Model

In this study, the trusted-relay QKD network is modeled as an undirected graph , where the vertex set represents the trusted-relay nodes within the network. Each node is equipped with QKD devices as well as key management (KM) modules, enabling it to generate keys locally via physical quantum channels, store these keys, and securely forward keys to neighboring nodes through the key management layer.

The edge set E consists of key management links , which represent logical secure key relay channels between nodes and . These links serve as the backbone for multi-hop key forwarding and distribution within the trusted relay architecture. It should be noted that each key management link is supported by underlying physical quantum links that enable raw key generation between adjacent nodes. Edges in the graph correspond to the logical connections used for key relay rather than the physical quantum channels themselves.

To accurately characterize the operational attributes of each quantum link, two key parameters are defined for every : the key distribution rate limit and the key pool capacity . Specifically, denotes the maximum rate at which quantum keys can be distributed through link , while represents the maximum capacity of the key pool between adjacent nodes.

3.1.2. Quantum Key Pool Model

Each link in the trusted-relay QKD network is associated with a key pool

, which stores the quantum keys shared between adjacent nodes

and

. This key pool supports key generation, storage, and consumption, and dynamically reflects the availability of key resources on the corresponding link. The key pool is bidirectionally symmetric, i.e., for any node pair

and

, the shared key pool satisfies

. The state of the key pool on link

at time

t is defined as a triplet:

where: denotes the amount of remaining usable keys; represents the key generation rate; represents the key consumption rate.

To ensure system stability and prevent the key pool from exceeding its maximum capacity, the key pool evolves over discrete time steps of duration

according to the following update rule:

This formulation guarantees that the number of available keys remains within the allowed limits, thereby enabling dynamic control over key resources and supporting the sustainable operation of the QKD network.

3.1.3. Routing Constraints

Quantum key distribution request is defined as a triplet , where the source node intends to transmit quantum keys to the destination node with a transmission demand of R. To ensure the feasibility of key transmission and efficient allocation of network resources, the selected routing path must satisfy the following constraints.

- 1.

Connectivity constraint: For any pair of adjacent nodes along the routing path, a physical link must exist to guarantee topological continuity.

- 2.

Bandwidth constraint: At any time

t, for each link

, the cumulative key distribution rate incurred by all active requests traversing this link must not exceed

:

where

denotes the instantaneous key distribution rate associated with request

R on link

at time

t.

- 3.

Key resource availability constraint: To ensure path viability, all links must have positive remaining key resources at time

t, satisfying:

where

represents the path from source node

s to destination node

d.

3.2. Online Q-Learning Model Design

3.2.1. State Space Definition

The agent’s state representation captures both routing information and the dynamic status of key resource utilization. Based on this, the state space is formally defined as:

where denotes the current node of the quantum key at time t, and represents the destination node for the key distribution task. The set N includes all trusted-relay nodes in the network. represents the agent’s perception of the status of key resources on the link , which is a crucial input to decision-making as it reflects the degree of resource contention after normalization and discretization.

To accommodate the discrete nature of the Q-learning model, the continuous key occupancy value is discretized as follows.

- 1.

Normalization: Given the known maximum capacity of the key pool on each link

, the remaining key amount is first normalized into a key occupancy ratio:

- 2.

Interval Partitioning: The range of occupancy ratios

is uniformly divided into

M intervals of equal width

, forming a discrete set of states:

- 3.

State Mapping: The continuous occupancy ratio is mapped to a discrete state label using:

Here, denotes the discretized state of the key pool on link . A higher discrete level indicates a higher key occupancy ratio, implying greater resource contention on the link. This feature enables the agent to make routing decisions that are more responsive to the availability of real-time resources.

3.2.2. Action Space Definition

For an agent currently located at node

, its set of possible actions is constrained by the set of neighboring nodes. The neighbor set is formally defined as:

This represents all directly connected adjacent nodes to which the quantum key can be forwarded from node

. Therefore, the agent’s action space at time

t is defined as:

Here, the action denotes the agent’s decision to transmit the quantum key from its current node to one of its neighboring nodes. The action space characterizes all feasible and permissible movements available to the agent at a given decision point.

3.2.3. Reward Function Design

In Q-learning-based routing, the reward function should comprehensively account for link resource utilization, key consumption and replenishment dynamics to ensure balanced allocation, alleviate congestion, and mitigate the risk of key exhaustion. To this end, a reward function is constructed based on the effectiveness of quantum key resource usage, defined as:

Here, denotes the key occupancy ratio on link at time t, while represents the predefined ideal occupancy ratio. The absolute deviation serves as a penalty for imbalance in resource distribution.

The term corresponds to the instantaneous key consumption rate of the link. A higher consumption rate leads to greater penalty, discouraging the selection of links with rapid key depletion. Conversely, denotes the key generation rate, serving as a positive incentive to encourage routing through links with sufficient and sustainable resource supply. Together, and capture the dynamic consumption and replenishment capabilities of the key pool, which are critical to efficient resource utilization.

The parameters , and are tunable hyperparameters that balance the relative importance of each component in the reward calculation. By incorporating both positive and negative incentives, this reward structure not only penalizes deviation from balanced resource states, but also promotes link selection strategies that prioritize adequate key availability and moderate utilization. This design allows the agent to dynamically adapt to evolving network conditions by applying the reward immediately after each hop, enabling real-time policy updates that enhance the stability and efficiency of quantum key distribution services.

3.2.4. Policy and Update Mechanism

In the Q-learning framework tailored for quantum key distribution, the environment is designed to simulate the dynamic evolution of key pools on all links after each action. This real-time feedback mechanism ensures that the agent consistently perceives key resource availability during learning, enabling context-aware decision-making.

To balance exploration and exploitation, a temporal-difference (TD) learning framework with an

-greedy policy is employed. The behavior policy

is defined as:

Here,

denotes the exploration rate, and

is the number of available actions at state

s. This strategy allows for sufficient exploration in the early training phase while enabling convergence to the optimal policy

as learning progresses. The Q-value are updated according to the TD-maximization rule:

where

is the learning rate and

is the discount factor.

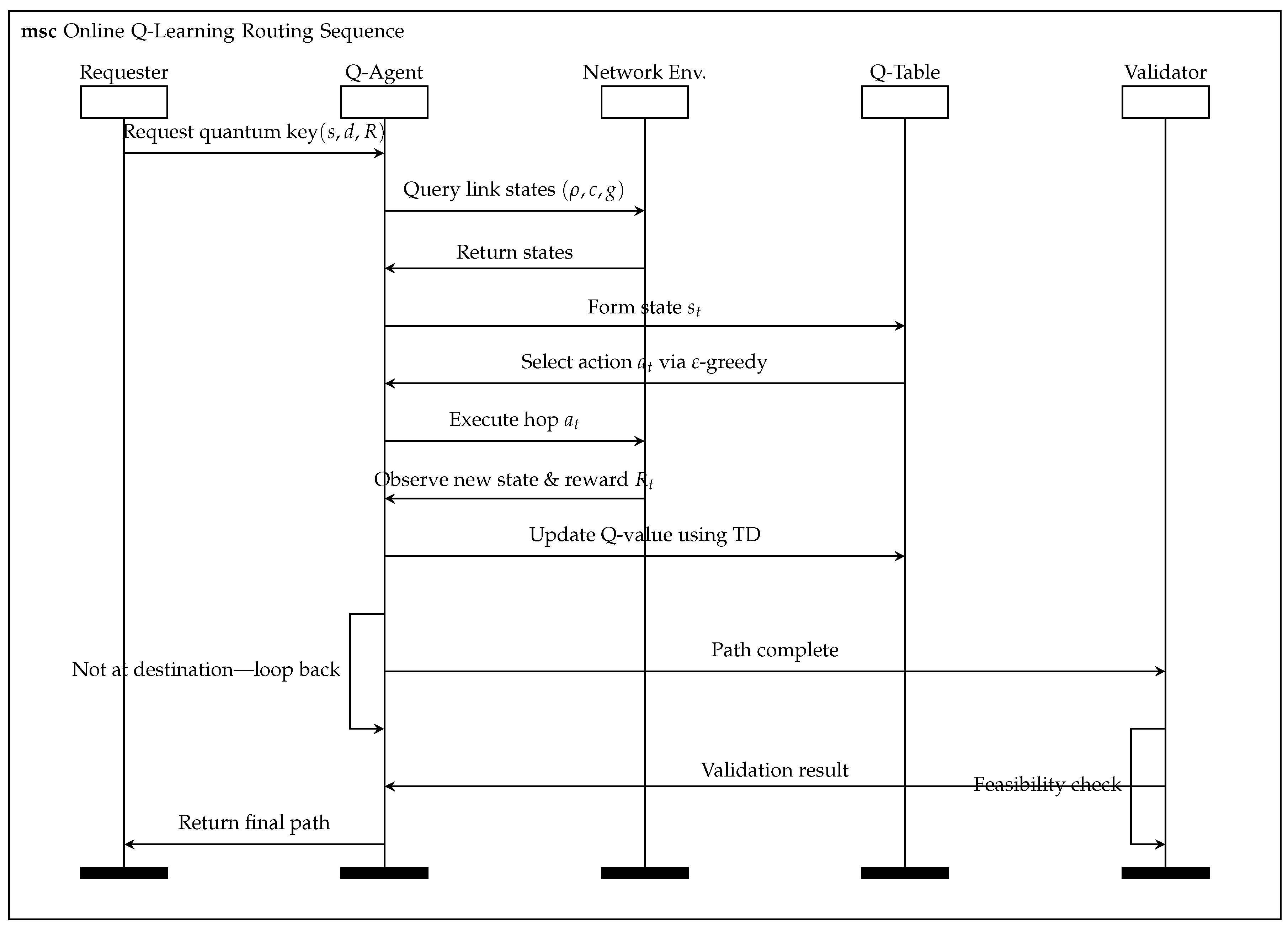

is the reward signal, which jointly considers quantum key consumption, generation, and occupancy balance. These Q-value updates occur online during deployment, allowing the agent to learn on the fly. Guided by a task-specific reward model that aligns learning with resource efficiency, the agent progressively acquires optimal routing strategies through real-time interaction with the dynamic QKD environment. The detailed training procedure is outlined in Algorithm 1. The algorithm runs in an online fashion: at each hop the agent selects an action, observes reward, and updates its Q-table before proceeding.

The end-to-end quantum key routing process is structured into four tightly integrated phases—

Initialization,

Local State Perception,

Path Decision & Value Update, and

Feasibility Verification & Feedback—which together form a closed-loop optimization cycle. As shown in

Figure 2. During live operation, each routing decision prompts an immediate Q-table update, and this cycle operates continuously until the policy converges.

|

Algorithm 1 Episodic Online Q-Learning for Key Scheduling |

Input: QKD network , max key capacity , learning rate , discount factor , exploration rate , interval count M, reward weights , , , target occupancy

Output: Optimal routing policy

- 1:

for each episode do

- 2:

Randomly initialize and

- 3:

Observe on outgoing links from

- 4:

Discretize:

- 5:

Construct state

- 6:

while do

- 7:

Select using -greedy strategy - 8:

Execute , observe updated key pool

- 9:

Observe new state

- 10:

- 11:

Update Q-value using TD rule:

- 12:

- 13:

return

|

4. Results and Performance Discussion

4.1. Simulation Setting

We develop a modular simulation framework based on QKDNetSim (NS-3.41) to emulate quantum key management and routing in dynamic trusted-relay QKD network. Simulations run on Ubuntu 22.04 with an Intel i7 CPU and 128GB RAM. Algorithms are implemented in Python 3.9 via Anaconda 3.2.0 for reproducibility.

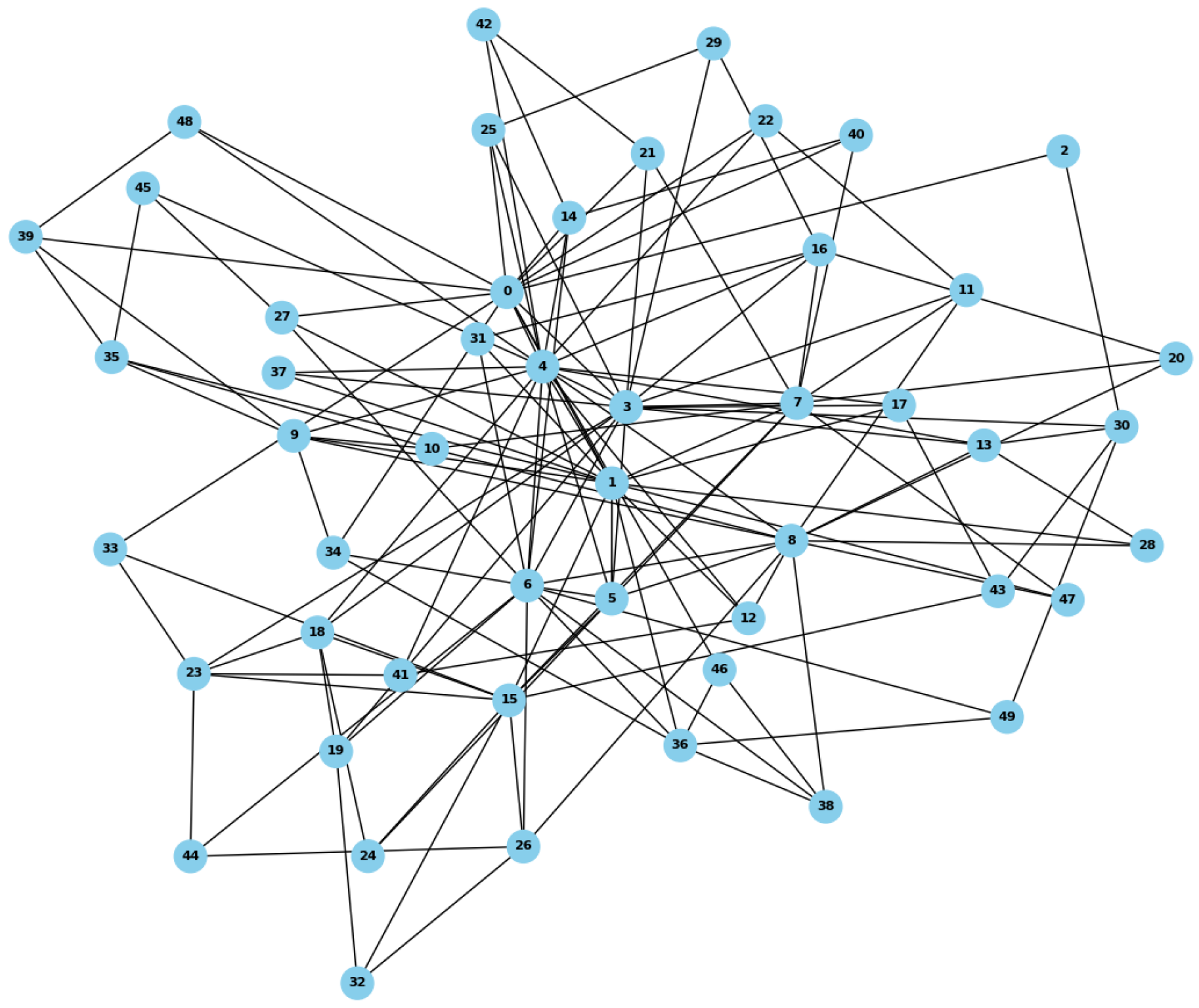

In this paper, training and testing are conducted on a 50-node Barabási–Albert network, as shown in

Figure 3. Each edge in the logical graph represents a virtual key channel at the key management layer, abstracting the availability and service efficiency of quantum keys. Three static attributes characterize each channel: the initial key weight, denoting the starting amount of available key; the effective channel delay, indicating latency or congestion levels; and the sine-state variable, representing the baseline pattern of periodic capacity fluctuations caused by environmental or physical factors.

Table 1 summarizes core settings for modeling network topology, traffic, and link dynamics.

Table 2 outlines Q-learning hyperparameter tuning across training stages to match traffic and resource variations.

The simulation models two components: dynamic virtual key channels and key request lifecycles. (1) Channel states evolve via edge deletion/restoration, random walk, and sinusoidal delay modulation. Routing must adapt in real time to ensure efficient key delivery. (2) Key requests are packet-like units with source, destination, and ID. randomGeneratePackets initializes a fixed number of requests at non-saturated sources and adds them to the sending_queue, ensuring distinct destinations and respecting max_send_capacity and max_receive_capacity. Delivered or rejected requests are replaced via GeneratePacket to maintain constant load. Blocked requests enter the PurgatoryList and are reinjected later to prevent congestion and deadlock.

4.2. Online Episodic Training Performance

This section outlines an evaluation framework for the proposed Q-learning-based routing strategy in trusted relay QKD networks, considering three dimensions: operational efficiency, resource distribution, and service quality. To support this, six performance metrics are defined and monitored during training: average delivery time, average and maximum key utilization ratios, proportions of idle and overloaded nodes, and delivery failure ratio. These metrics characterize system behavior under dynamic conditions and assess the effectiveness of the strategy in achieving resource-aware and efficient routing.

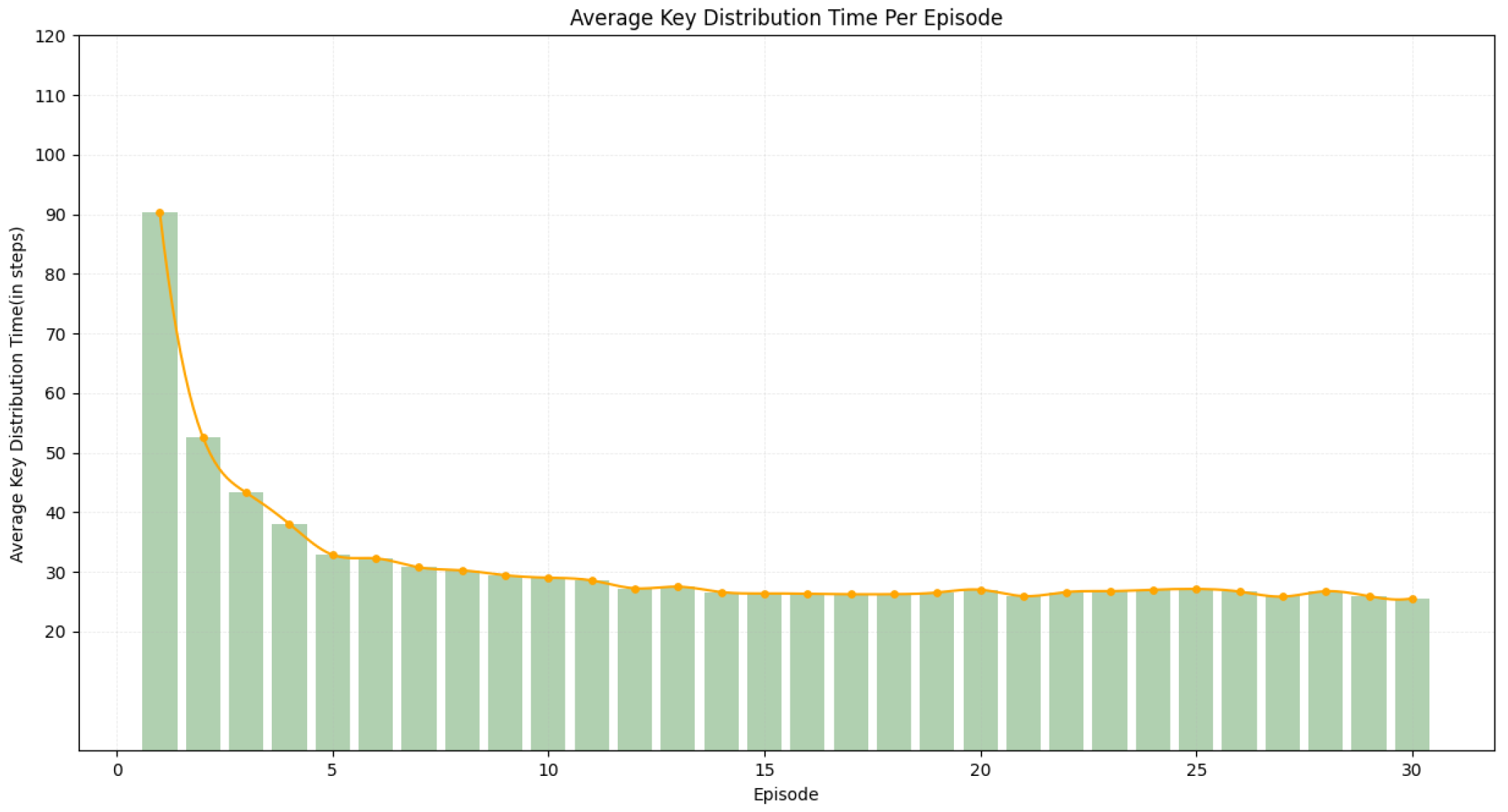

4.2.1. Average Key Distribution Time Per Episode

The average delivery time quantifies the mean number of hops that successfully delivered quantum key packets traverse from the source to the destination, serving as an indicator of routing efficiency. It is formally defined as:

where

denotes the average delivery time,

is the number of successful key transmissions within the current training episode, and

represents the hop count of the

k-th successful transmission. A smaller

implies that the learned Q-values effectively guide the agent toward shorter routing paths, reflecting both improved convergence behavior and reduced routing overhead.

At the initial training stage, with Q-values initialized to 0, the policy relies on

-greedy fully random exploration, resulting in traffic heavily concentrated on hub nodes and pushing the average hop count to approximately 90. As the penalty term

effectively suppresses the overloading of high-cost hub links, the average hop count sharply decreases to around 32. During the mid-term phase, the sinusoidal edge weight fluctuations create alternating link qualities. The reward factor

promotes timely use of high-quality links, while

prevents over-concentration. The average hop count steadily declines to 26 with minor fluctuations. In the late stage, as

nears 0, the policy becomes deterministic and sensitive to link dynamics. Optimal paths periodically shift between hubs and peripheries, causing a brief rebound (

) before stabilizing at 25.5, indicating robust adaptability and convergence, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

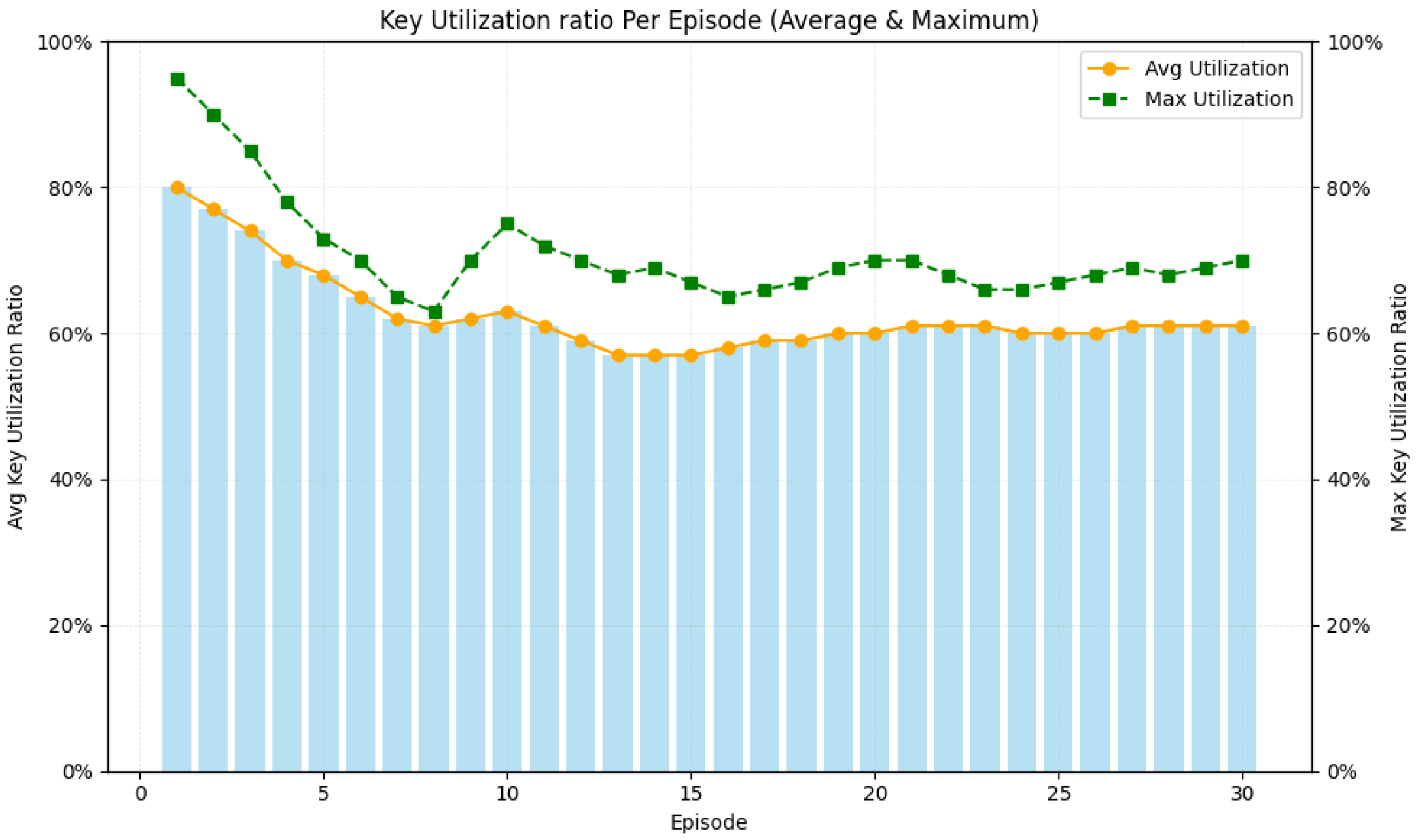

4.2.2. Key Utilization Ratio Per Episode (Average & Maximum)

To accurately reflect the resource usage status of the trusted-relay QKD network at the end of each training episode, we adopts a metric based on the instantaneous utilization of active links.

: The set of all links in the network; denotes the total number of links; : The index of the training episode, where . : Maximum key pool capacity of link . : Remaining key amount on link at the end of episode e, representing the currently available key.

The active link set is defined as:

This includes links that carried at least one key distribution operation during episode

e, and serves as the denominator in utilization computation.

For any active link

, the instantaneous utilization at the end of episode

e is defined as:

Maximum Key Utilization: The highest instantaneous utilization among active links at the end of episode

e.

This metric captures the link that is most critically depleted in terms of key resources. A value of suggests severe congestion and necessitates dynamic rerouting or capacity scaling.

Average Key Utilization: The arithmetic average of instantaneous utilizations across all active links at the end of episode

e. It characterizes the overall resource stress level of all active links.

As shown in

Figure 5, average key utilization decreased from 80% to 70% during the first two episodes. In Episode 1, the high exploration rate

led to excessive traffic on hub links, pushing utilization to 80%. In Episode 2, the introduction of the penalty term

and balancing factor

redirected traffic toward peripheral links, reducing utilization to 70%. From Episodes 3 to 10, the agent began to exploit structurally balanced and sustainable paths. The reward term

—associated with key generation rate—helped prioritize links with high replenishment capacity, contributing to a steady decline in key utilization from 65% to 60%. Starting from Episode 11, experience replay reinforced historically efficient routes, bringing utilization down to a minimum of 57%. In later episodes, as

approached 0, sporadic exploration caused minor fluctuations, but utilization remained steady around 58%-60%. Ultimately, the convergence of Q-values and the long-term guidance of the

-discounted reward led the policy to favor consistently efficient links, stabilizing utilization at 60%-61%.

Maximum key utilization drops from 95% in Episode 1 (high -driven exploration overloads hub nodes, with average hop count around 90 and failure ratio of 18.5%) to 70% by Episode 6 as long-term reward and balance factor redirect traffic to suboptimal paths. Between Episodes 7 and 15, a decaying drives exploitation of effective low-latency links, smoothing utilization fluctuations despite occasional reroutes. In Episodes 16 to 30 the policy stabilizes into a balanced rotation between hub and peripheral links with max_util oscillating between 66% and 70%.

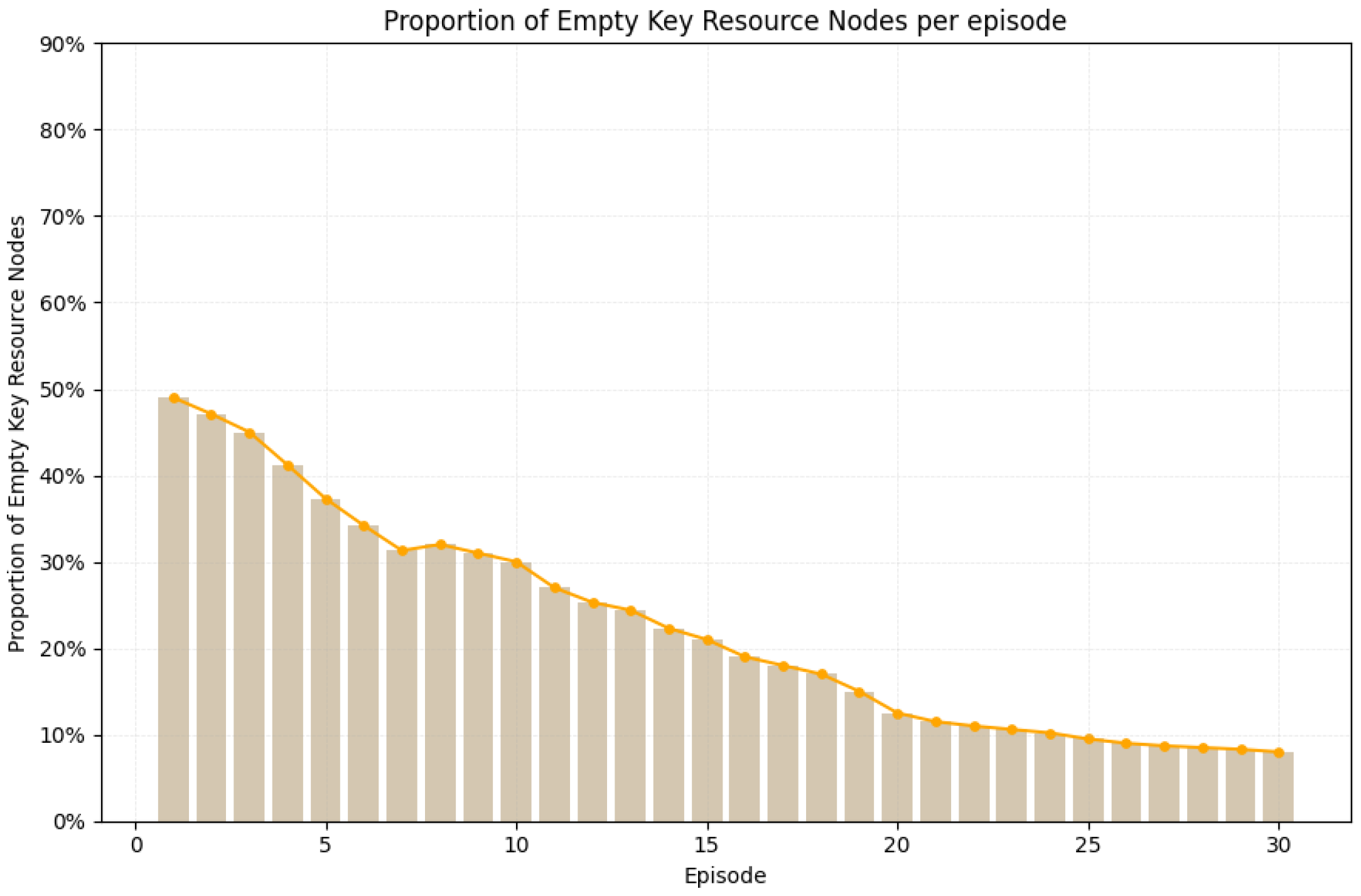

4.2.3. Proportion of Idle Key Resource Nodes Per Episode

The idle link set comprises links that experienced no key consumption during the training episode. The proportion reflects the degree of idle resources in the network.

As shown in

Figure 6, the idle node ratio drops from 49% in Episode 1, where hub-centric exploration leaves peripheral nodes underutilized, to 47.1% in Episode 2 as the penalty term

and incentive factors

begin redirecting traffic toward edge links. During Episodes 6 to 10, experience replay and the decaying exploration rate

mitigate minor supply–demand mismatches, reducing the ratio to 30%. Between Episodes 11 and 15, the prioritized reuse of historically efficient paths—guided by

,

balancing and the long-term reward accumulation under

—further accelerates the decline to 21%. In Episodes 16 to 20, dynamic adjustments to the learning rate and

counter occasional exploratory detours, further lowering the ratio to 12.5%. Finally, refined exploration strategies, improved path replay, and calibrated reward parameters ensure full link participation, stabilizing the idle node ratio at 8%.

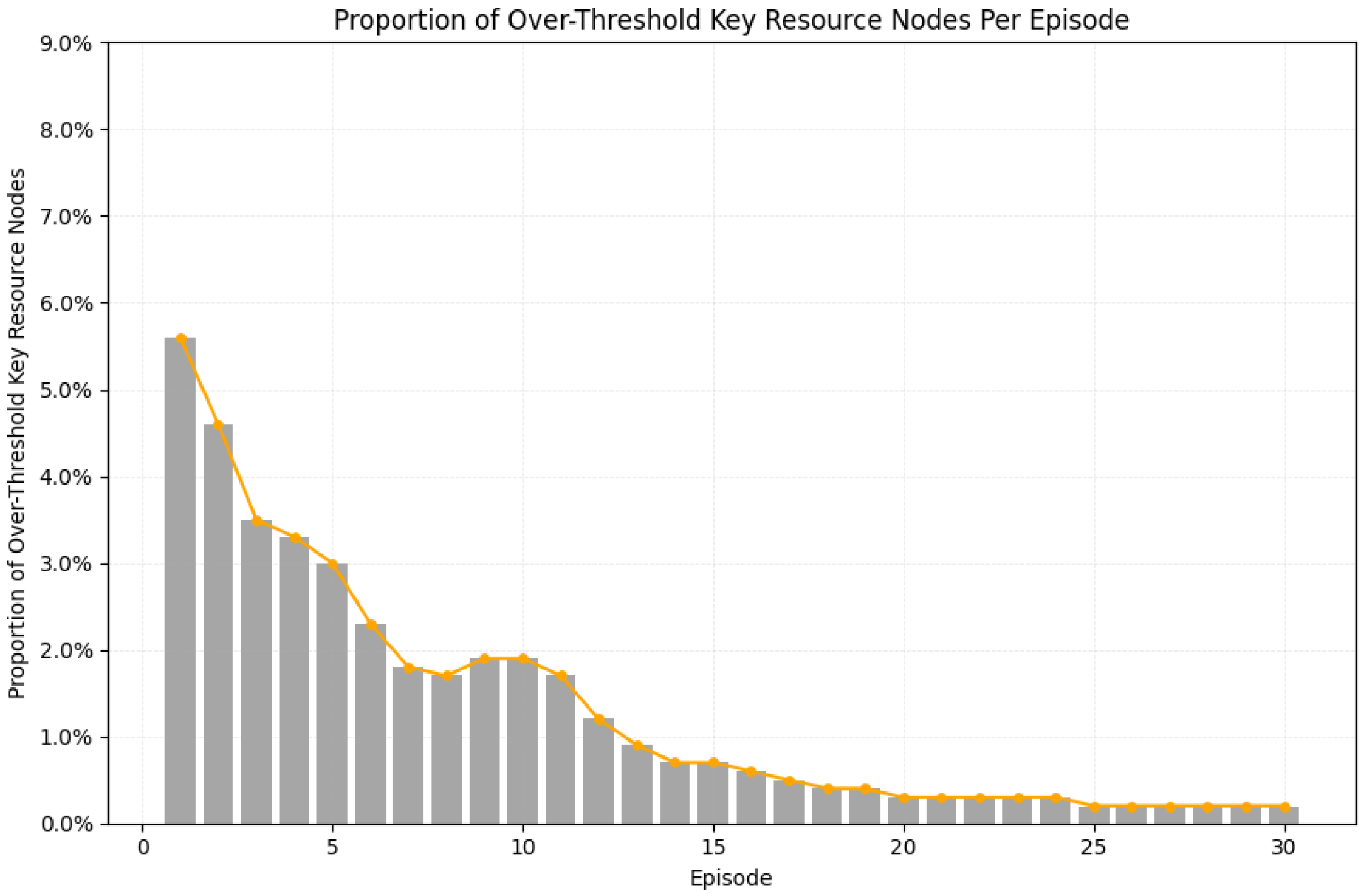

4.2.4. Proportion of Over-Threshold Key Resource Nodes Per Episode

Given a utilization threshold

, the over-threshold link set at the end of episode

e includes all links whose consumed key ratio exceeds

. To quantify network-wide congestion risk, we define the over-threshold link ratio

as:

The ratio indicates the fraction of potentially congested links.

The results (see

Figure 7) indicate that the overloaded node ratio decreases from 5.6% in Episode 1 to 0. 2% in Episodes 24 to 30. In Episode 2, the activation of secondary branches during traffic surges, combined with the penalty term

, reduces the ratio to 4.6%. From Episodes 3 to 5, the further balance between

and

alongside the capacity of parallel branches drives the ratio down to 3%. Transient mismatches between supply and demand, coupled with occasional hub reuse under the

-greedy exploration strategy, slow the decline to 2.3% by Episode 9. The synchronization of traffic and sustained

-weighted rewards from Episodes 14 to 18 guide the policy toward resource-rich, moderately loaded paths, further reducing the ratio from 1.9% to 0.4%. Following local load adjustments through

and

in Episodes 19 to 23, the overloaded node ratio stabilizes at 0.2% from Episode 24 onward.

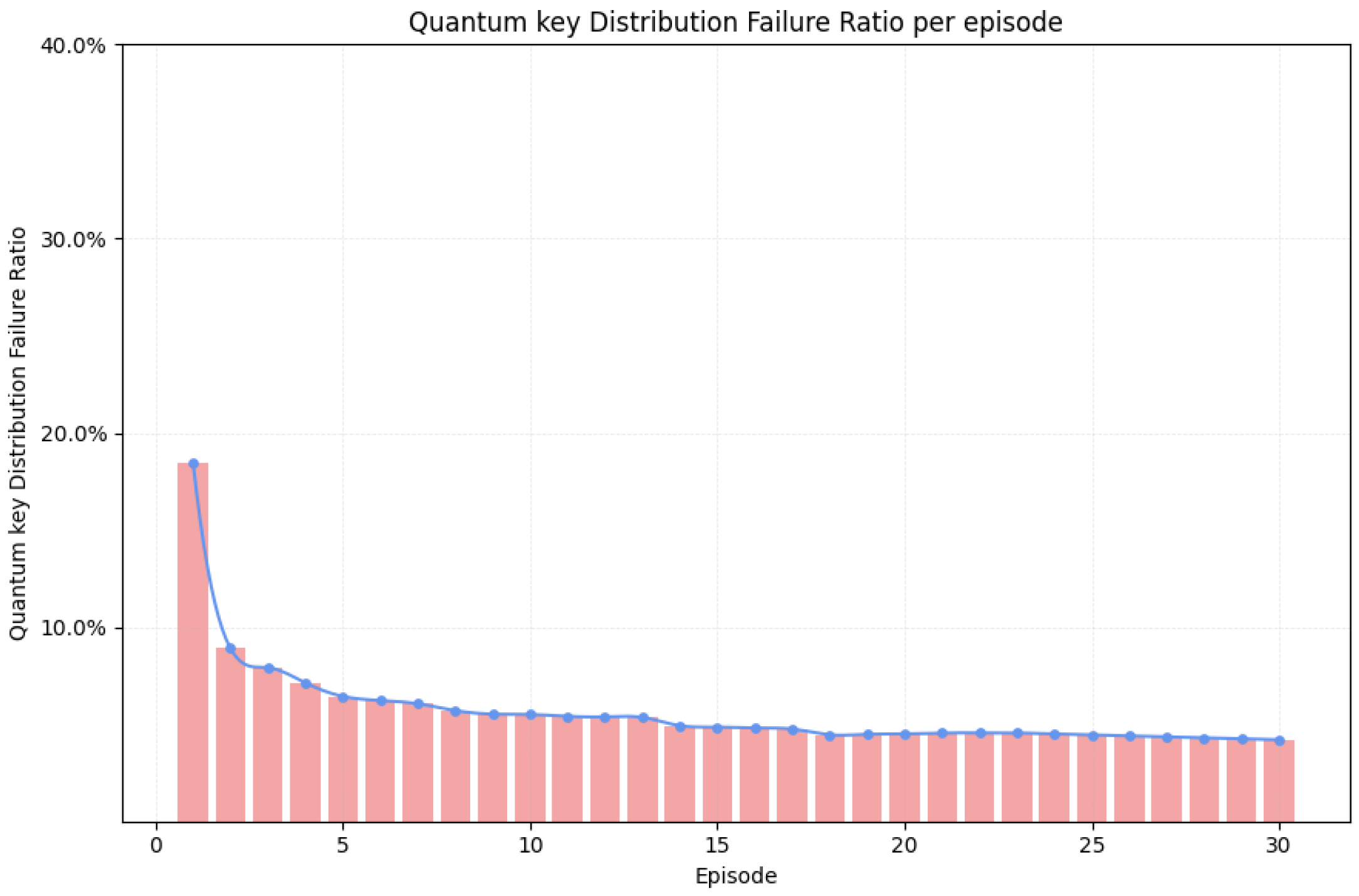

4.2.5. Quantum Key Distribution Failure Ratio Per Episode

The key distribution failure ratio quantifies the proportion of failed key distribution attempts relative to the total number of attempts. It is defined as:

where:

: number of successful key transmissions;

: total number of key distribution attempts. This metric serves as a direct indicator of the overall reliability and effectiveness of the routing strategy under the current network configuration and learning policy. Failures may arise from key pool depletion, disconnected topologies, insufficient path length, or suboptimal Q-value guidance.

Statistical analysis (see

Figure 8) shows the packet failure ratio of 18.48% in Episode 1, caused by queue overflows and transient link breaks on hub routes. Subsequent episodes exhibit minor fluctuations due to supply phase variations and decay of

, but adaptive learning rates and replay of experiences reduce the failure rate to 5.5%. Between Episodes 10 and 13, the continued exploration of

-greedy conditions combined with

incentives lowers it further to 5.35%. The alignment of the full network supply and the convergence of the Q-value in episodes 14 to 18 bring it down to 4.45%. Episodes 19 to 23 see brief fluctuations from localized

-

switching, while residual exploration, path replay, and optimized hub-branch routing from Episodes 24 to 30 stabilize the failure ratio at 4.2%.

4.3. Offline Policy Evaluation for Testing Performance

In trusted-relay QKD networks, rising load causes sharp spikes in metrics such as maximum utilization, overload ratio, and failure ratio due to key depletion thresholds, routing feedback delay and BA topology. This effect is pronounced in the Dijkstra route, where the hub links saturate rapidly, intensifying early congestion. Conversely, Q-learning leverages key buffer feedback and delivery rewards to gradually balance traffic, resulting in smoother utilization and lower idle node ratio, thereby mitigating systemic overload.

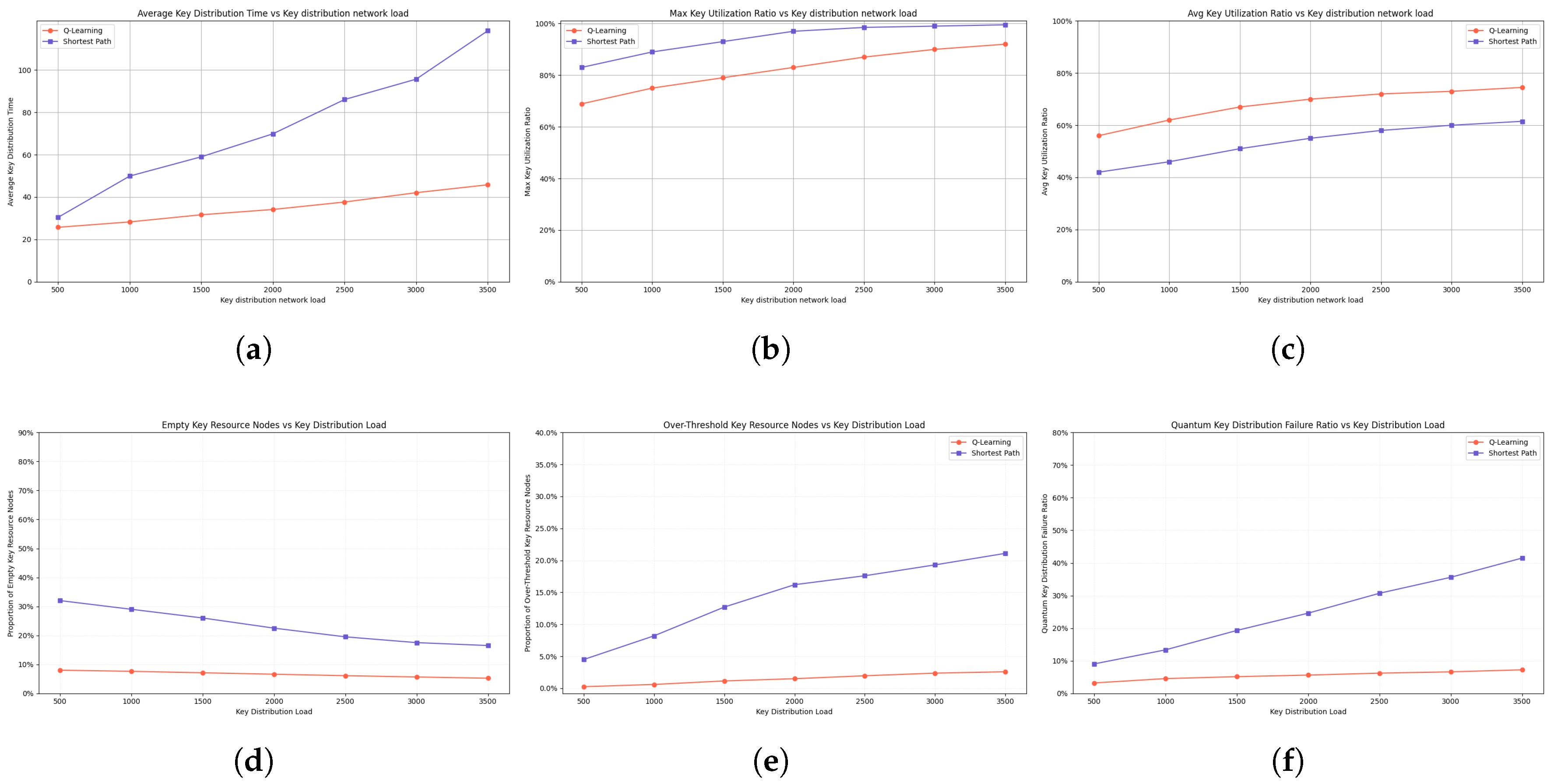

4.3.1. Performance Comparison of 50-Node Dijkstra vs. Q-Learning

Average key distribution time (see

Figure 9(a)): As traffic scales from 500 to 3500 requests, Q-learning maintains near-linear growth from 25.7 to 45.8 hops, while Dijkstra exhibits exponential delay escalation from 30.4 to 118.5 hops, over 2.5 times higher. This divergence results from Q-learning’s adaptive, experience-based avoidance of congested links and sensitivity to time-varying edge delays. In contrast, Dijkstra selects static shortest paths without network state awareness, causing persistent hub overload in scale-free topologies. Under Dijkstra routing, elevated failure ratio and max key utilization exacerbate delays.

Max key utilization (see

Figure 9(b)): As traffic increases from 500 to 3500 requests, Q-learning increases utilization moderately from 68.9% to 92%, while Dijkstra rapidly escalates from 83% to 99.5%, nearing capacity saturation. This contrast arises from Q-learning’s adaptive avoidance of overloaded links via experience-driven routing, distributing traffic across peripheral paths. Once utilization under Dijkstra exceeds 97%, failure ratio exceeds 30%, triggering retransmissions and latency spikes. Q-learning sustains lower peaks and smoother progression, offering greater resilience and efficiency under high-load conditions.

Average key utilization (see

Figure 9(c)): As the load increases from 500 to 3500, Q-learning steadily improves the average utilization from 56% to 74.5%, while Dijkstra rises more slowly from 42% to 61.5%. This disparity stems from routing behavior: Q-learning, guided by the exploration of the

gray areas and the updates of the Q-value, activates a broader set of links and achieves a more balanced traffic distribution. In contrast, Dijkstra concentrates load on static shortest paths, leaving peripheral resources underutilized. Q-learning promotes peripheral usage early on, avoids congestion mid-training, and sustains balanced routing near saturation. Dijkstra, by contrast, exhibits slow gains and early bottlenecks, plateauing under high load. Higher average utilization in Q-learning reduces the risk of overload, increases capacity use, and improves end-to-end performance, demonstrating greater adaptability in dynamic QKD environments.

Proportion of idle key resource nodes (see

Figure 9(d)): As load increases from 500 to 3500, Q-learning steadily reduces idle nodes from 8% to 5.23%, while Dijkstra drops from 32% to only 16.5%. This shows how Q-learning uses peripheral and low-degree nodes more effectively than Dijkstra’s static routing. Lower idle ratios in Q-learning align with improved utilization and reduced core congestion, while Dijkstra’s high idle ratio highlights poor adaptability and resource inefficiency.

Proportion of key resource nodes above the threshold (see

Figure 9(e)): As load scales from 500 to 3500, Q-learning maintains a low and stable ratio 0.25% to 2.59%, while Dijkstra exhibits a sharp rise (4.5% to 21.1%). This stems from Q-learning’s reward-guided detouring around overloaded nodes, in contrast to Dijkstra’s static path reuse. The trends show that Q-learning achieves steady control, whereas Dijkstra rapidly saturates hub nodes. Higher overload ratios observed in Dijkstra correspond to increased failure rates and limited routing flexibility, highlighting Q-learning’s enhanced adaptability and load balancing capabilities.

Quantum key distrbution failure ratio (see

Figure 9(f)): As the load increases from 500 to 3500, the failure ratio in Q-learning increases steadily from 3.2% to 7.2%, while in Dijkstra it increases dramatically from 9 0% to 41.5%. This disparity arises because Q-learning dynamically updates routing based on feedback, avoiding congested links through exploration, thus reducing queuing pressure. In contrast, Dijkstra’s fixed shortest-path approach lacks load awareness, causing persistent congestion and packet loss on central links when queues are overflowing. Failure ratio strongly correlates with overloaded node ratio and maximum key utilization, which are higher in the Dijkstra scenario. Overall, Q-learning’s adaptive routing effectively controls failure growth and maintains network stability under heavy load, whereas Dijkstra’s static routing exacerbates degradation.

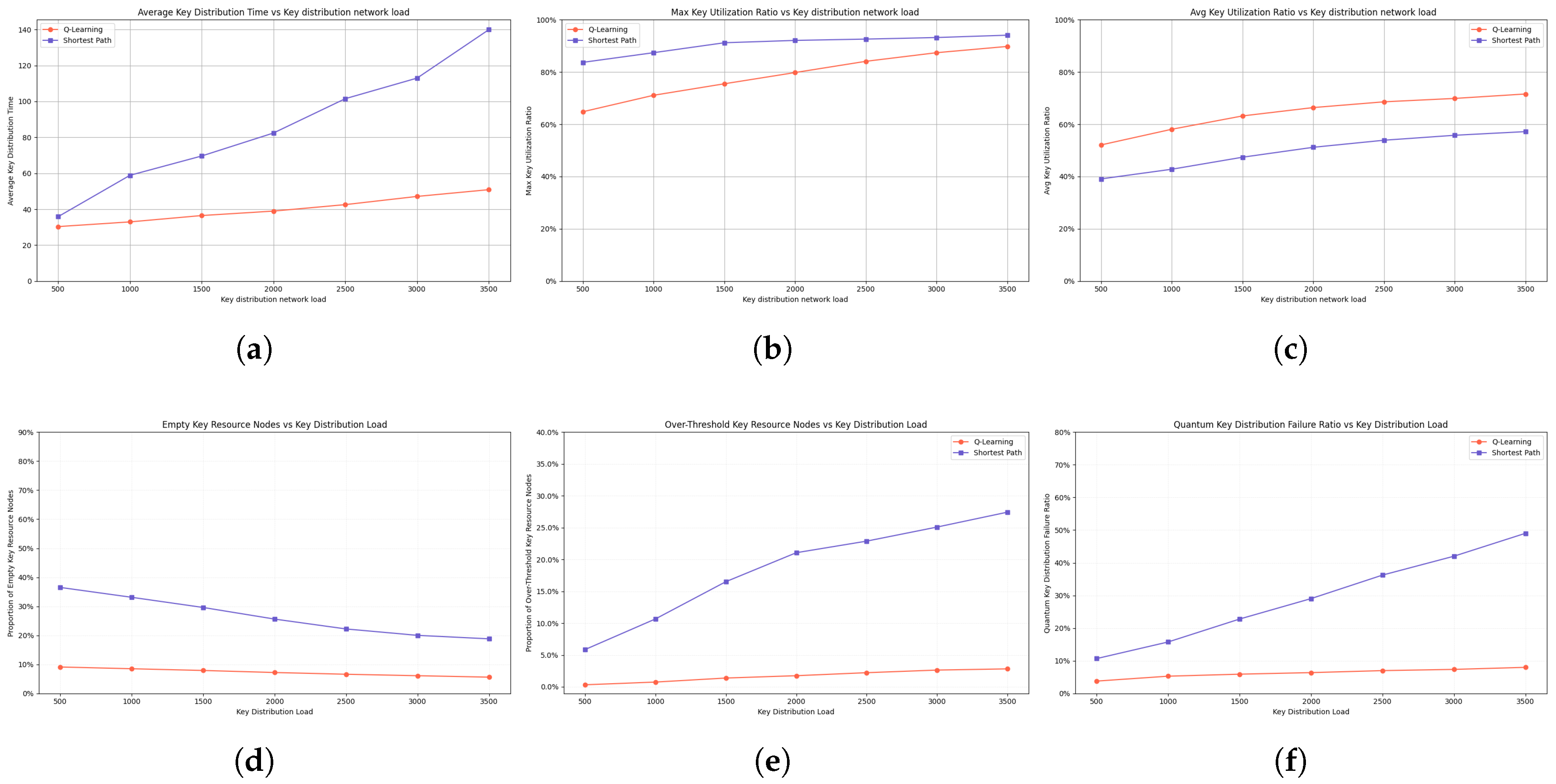

4.3.2. Performance Comparison of 100-Node Dijkstra vs. Q-Learning

Average key distribution time (see

Figure 10(a)): Under varying loads, Q-learning shows moderate growth in average hop count. In the 100-node network, it increases from 30.3 to 36.5 hops under low load (500 to 1500 packets), and from 38.9 to 47.1 hops under medium load (2000 to 3000 packets), benefiting from reward terms that promote traffic dispersion and key-efficient paths. Even under high load (3500 packets), it maintains 50.9 hops, reflecting robustness near saturation. In contrast, the Dijkstra exhibits sharp increases: from 35.9 to 69.6 hops under low load, 82.4 to 113 hops under medium load, and up to 139.9 hops under high load, due to traffic concentration on fixed routes. Similar trends appear in the 50-node network with lower absolute hop count values, but the performance gap widens with scale, highlighting the limitations of static routing under dynamic traffic conditions.

Max key utilization (see

Figure 10(b)): As traffic increases from 500 to 3500 packets, Q-learning raises maximum key utilization gradually from 64.8% to 89.8%, remaining within system limits and preserving roughly 10% of capacity. In contrast, Dijstra routing rises rapidly from 83.7% to 94.1%, already exceeding 88% at just 1000 packets and initially maintaining up to 16% higher utilization than Q-learning, reflecting more severe congestion. Q-learning achieves controlled growth under low and medium loads by distributing traffic and preventing overload, whereas Dijkstra quickly saturates hub links. At high load, Q-learning retains buffer space, while Dijkstra leaves less than 6% headroom, pushing the network toward saturation.

Average key utilization (see

Figure 10(c)): As traffic increases from 500 to 3500 packets, Q-learning steadily improves average utilization from 52.1% to 71.6% by progressively activating peripheral links. In contrast, Dijkstra routing rises from 39.1% to just 57.2%, leaving a significant portion of links underutilized. Under low load, Q-learning rapidly engages backup paths through reward incentives, while Dijkstra concentrates traffic on fixed shortest paths, resulting in slower utilization growth. At medium and high loads, while Dijkstra exhibits slower utilization growth, reflecting its limited ability to exploit available resources. This disparity stems from the scale-free topology’s abundance of low-degree nodes, which Q-learning effectively leverages by distributing traffic and adapting to fluctuating link quality. In smaller networks, Q-learning starts with slightly higher utilization due to fewer routing alternatives, but converges toward the same performance as network size grows, indicating limited sensitivity to scale.

Proportion of idle key resource nodes (see

Figure 10(d)): Q-learning reduces the proportion of idle key resource nodes from 9.1% to 5.6%, demonstrating enhanced node activation and traffic distribution. In contrast, shortest-path routing lowers idle nodes from 36.5% to 18.8% but remains substantially higher, indicating persistent underutilization. Under low load, Q-learning achieves 7.9% idle nodes versus shortest-path’s 29.6%; at medium load, 6.1% versus over 20%; and at high load, 5.6% compared to nearly 20%. This disparity stems from Q-learning’s adaptive activation of peripheral nodes via load-balancing rewards, which enhances path diversity and reduces node idleness. In contrast, shortest-path routing remains biased toward hub-centered paths, leaving many nodes underutilized—especially in larger networks. Although idle ratios decrease for both methods in smaller networks, Q-learning consistently maintains lower values across scales, highlighting its superior scalability and resource efficiency.

Proportion of over-threshold key resource nodes (see

Figure 10(e)): Across all load levels, Q-learning keeps the over-threshold link ratio below 3%, demonstrating effective load balancing and minimal overload. In contrast, shortest-path routing shows a sharp increase, reaching 27.4%, indicating severe congestion. At low load, Q-learning’s ratio is 0.3% compared to shortest-path’s 5.85%; at medium load, 1.7% versus 21.1%; and at high load, Q-learning limits overload to 2.82% while shortest-path peaks at 27.4%. This difference arises from Q-learning’s adaptive traffic distribution that avoids high-consumption links, whereas shortest-path relies on fixed routes that repeatedly overload hub links. As network size increases, shortest-path routing shows a further rise in over-threshold links, indicating aggravated congestion and limited scalability. In contrast, Q-learning maintains consistently low overload ratios across different network sizes and traffic levels.

Quantum key distrbution failure ratio (see

Figure 10(f)): Q-learning maintains a low, steadily increasing failure ratio from 3.78% to 7.98%, demonstrating effective overload control. In contrast, shortest-path routing experiences a sharp rise from 10.67% to 49.02%, with nearly half of transmissions failing at high load due to persistent congestion and queue overflows on hub links. Under medium load, scaling from 50 to 100 nodes amplifies the instability of the shortest path, increasing the failure ratio from 19. 3% to 22. 8%, while the failure ratio of Q-learning increases marginally from 5. 12% to 5. 89%, demonstrating stronger scalability and stability.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel Q-learning-based key scheduling framework designed for trusted-relay QKD network, addressing the challenges posed by dynamic key consumption and heterogeneous resource allocation. The proposed framework comprises three integral components: a Neighbor State Awareness Module that provides comprehensive monitoring of adjacent link parameters; an Online Q-learning Scheduler that adaptively optimizes resource utilization through a rigorously defined reward function; and a Routing and Validation Module that guarantees feasible and resource-aware path selection under network constraints.

The episodic online learning paradigm facilitates real-time, fine-grained policy updates, promoting balanced utilization of key pools, preventing resource over-concentration, and maintaining stable replenishment. Simulation results substantiate that, the proposed Q-learning-based key scheduling framework significantly outperforms traditional Dijkstra routing in trusted-relay QKD networks by enhancing transmission efficiency, resource utilization, and network stability. Specifically, it maintains average hop counts between 25.7 and 45.8 compared to Dijkstra’s exponential increase up to 118.5 hops; achieves balanced key utilization with averages rising from 56% to 74.5% while keeping maximum utilization below 92%, unlike Dijkstra’s near-saturation at 99.5%; and ensures robust stability with overload ratios contained within 0.25% to 2.59% and failure ratio under 7.2%, far surpassing Dijkstra’s overloads of up to 21.1% and failure ratio exceeding 41.5%. These findings validate the framework’s ability to achieve load balancing, congestion mitigation, and scalable performance in dynamic QKD networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; methodology, Y.H.; software,Y.H.; validation,Y.H., Y.X. and W.G.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.H and Y.X.; resources, Y.H.; data curation, Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; visualization, Y.H.; supervision, J.T.; project administration, Y.X. and J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T and W.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (2021ZD0301300).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this article can be obtained from the author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. QKD Network Architecture

The trusted-relay QKD network comprises quantum key distribution links, key management (KM) links, and trusted QKD nodes. Each node integrates a quantum transmitter (QKD-Tx), receiver (QKD-Rx), and key management module. The quantum layer consists of point-to-point QKD device pairs that independently generate keys, which are then relayed through KM modules and links. The key management layer handles key distribution and interconnection across arbitrary node pairs within the QKD network. Above these, the control layer coordinates network elements via distributed controllers, while the management layer oversees global monitoring and administrative tasks. Finally, keys are delivered to cryptographic applications within the service layer of the user network by the KM nodes.

Figure A1, based on the ITU-T Y.3800 standard, depicts the reference architecture and core components of both the QKD and user networks.

Figure A1.

QKD network architecture.

Figure A1.

QKD network architecture.

In typical operations, cryptographic applications in the service layer initiate key requests to nearby KM nodes. These nodes verify local availability and, if sufficient keys exist, provision them directly to the application. Otherwise, a relay process is triggered. KM nodes cooperate with controllers to compute relay paths under the supervision of the manager, which continuously monitors network conditions. Keys are securely relayed across intermediate KM nodes along the selected path and finally delivered in a standardized format to the requesting application, ensuring secure, end-to-end key provisioning.

Appendix A.2. Relay Routing Mechanism in QKD Network

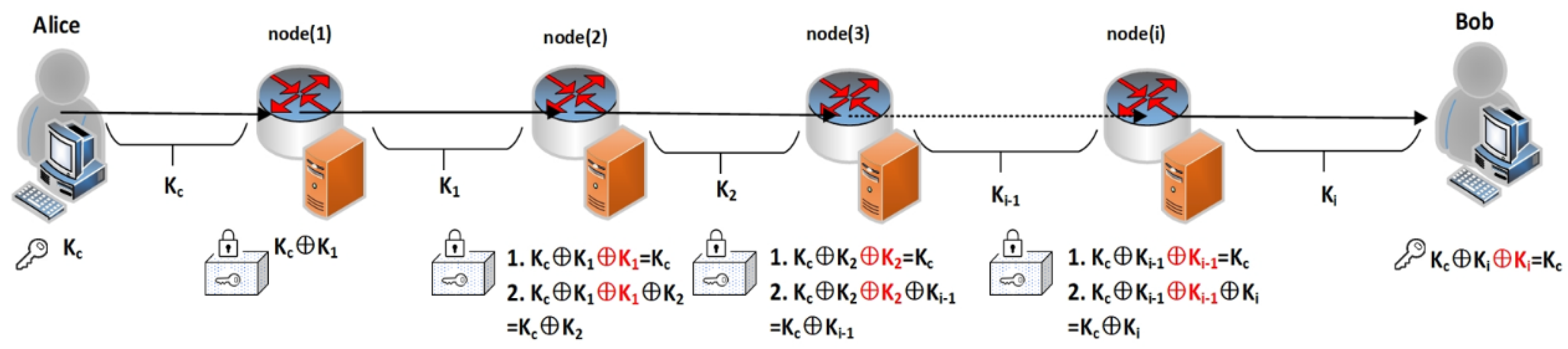

The trusted relay process of quantum key distribution, guided by routing algorithms, is illustrated in

Figure A2 and consists of four steps, where the relay is performed using one-time pad (OTP) encryption to guarantee unconditional security.

1. In initialization phase, the source node Alice (node 1) identifies relay nodes within its communication range. Utilizing a classical network routing discovery protocol, responses are collected from various nodes. All responding nodes are included in the candidate set for the next-hop relay nodes, thereby initializing the routing algorithm.

2. According to the routing algorithm,

Alice (node 1) generates a global key

(communication key) and simultaneously negotiates a local key

with node 2 based on the BB84 quantum key distribution protocol. The global key is sequentially forwarded by trusted-relay nodes. In the example shown in

Figure 1, node 2 is selected to relay the global key

.

3. Under frequently changing network topologies, the routing algorithm dynamically senses the availability of key resources within the network to select candidate relay nodes, ensuring efficient key distribution. Detailed description of this algorithm is provided in

Section 4.

4. Node 1 and node 2 share the local key . node 2 receives the encrypted message from node1 and decrypts it using the shared key to recover . Concurrently, node 2 negotiates a local key with node 4 and encrypts the transmission as .

In this example, node 4 serves as the destination Bob. Generally, in network with multiple relay nodes, the relay process repeats steps 2, 3, and 4 until the destination node obtains the global key . At this point, both Alice and Bob possess the global key , enabling secure communication.

Figure A2.

Relay routing mechanism in QKD network.

Figure A2.

Relay routing mechanism in QKD network.

References

- Engin Zeydan, Chamitha De Alwis, Rabia Khan, Yekta Turk, Abdullah Aydeger, Thippa Reddy Gadekallu, and Madhusanka Liyanage, Quantum technologies for beyond 5G and 6G networks: Applications, opportunities, and challenges, arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.17133, 2025. [CrossRef]

- William K. Wootters and Wojciech H. Zurek, A single quantum cannot be cloned, Nature, vol. 299, no. 5886, pp. 802–803, 1982. [CrossRef]

- Artur K. Ekert, Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem, Physical Review Letters, vol. 67, no. 6, p. 661, 1991. [CrossRef]

- M. Krelina, Quantum technology for military applications, EPJ Quantum Technology, vol. 8, no. 1, article 24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liang, Employing quantum key distribution for enhancing network security, in Proc. 2023 International Conference on Image, Algorithms and Artificial Intelligence (ICIAAI 2023), Atlantis Press, 2023, pp. 518–526. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sahu and K. Mazumdar, State-of-the-art analysis of quantum cryptography: applications and future prospects, Frontiers in Physics, vol. 12, 2024, article 1456491. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Tsai, C. W. Yang, J. Lin, et al., Quantum key distribution networks: challenges and future research issues in security, Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 9, article 3767, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Yu, Y. Liu, X. Zou, et al., Secret-key provisioning with collaborative routing in partially-trusted-relay-based quantum-key-distribution-secured optical networks, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 3530–3545, 2022.

- H. Zhou, K. Lv, L. Huang, et al., Quantum network: security assessment and key management, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 1328–1339, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Elliott, A. Colvin, D. Pearson, et al., Current status of the DARPA quantum network, in Quantum Information and Computation III, SPIE, vol. 5815, pp. 138–149, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Peev, C. Pacher, R. Alléaume, et al., The SECOQC quantum key distribution network in Vienna, New Journal of Physics, vol. 11, no. 7, article 075001, 2009.

- M. Sasaki, M. Fujiwara, H. Ishizuka, et al., Field test of quantum key distribution in the Tokyo QKD Network, Optics Express, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 10387–10409, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Chen, Q. Zhang, T. Y. Chen, et al., An integrated space-to-ground quantum communication network over 4,600 kilometres, Nature, vol. 589, no. 7841, pp. 214–219, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Bi, M. Miao, and X. Di, A dynamic-routing algorithm based on a virtual quantum key distribution network, Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 15, article 8690, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, S. Qiu, and T. Yang, Optimization of hierarchical routing and resource allocation for power communication networks with QKD, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 504–512, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tanizawa, R. Takahashi, and A. R. Dixon, A routing method designed for a quantum key distribution network, in Proc. 2016 Eighth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), IEEE, 2016, pp. 208–214. [CrossRef]

- W. Han, X. Wu, Y. Zhu, et al., QKD network routing research based on trust relay, Journal of Military Communications Technology, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 43–48, 2013.

- C. Ma, Y. Guo, J. Su, et al., Hierarchical routing scheme on wide-area quantum key distribution network, in Proc. 2016 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), IEEE, 2016, pp. 2009–2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, D. Quan, C. Zhu, et al., A quantum cryptography communication network based on software defined network, in ITM Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, vol. 17, article 01008, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, D. Quan, and C. Zhu, Stochastic routing in quantum cryptography communication network based on cognitive resources, in Proc. 2016 8th International Conference on Wireless Communications & Signal Processing (WCSP), IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, H. Zhang, and J. Su, Quantum key distribution network: Optimal secret-key-aware routing method for trust relaying, China Communications, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 33–45, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Q. Han, L. Yu, W. Zheng, et al., A novel QKD network routing algorithm based on optical-path-switching, J. Inf. Hiding Multim. Signal Process., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 13–19, 2014.

- C. Yang, H. Zhang, and J. Su, The QKD network: Model and routing scheme, Journal of Modern Optics, vol. 64, no. 21, pp. 2350–2362, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Ma, Y. Guo, and J. Su, A multiple paths scheme with labels for key distribution on quantum key distribution network, in Proc. 2017 IEEE 2nd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), IEEE, 2017, pp. 2513–2517. [CrossRef]

- M. Mehic, O. Maurhart, S. Rass, et al., Implementation of quantum key distribution network simulation module in the network simulator NS-3, Quantum Information Processing, vol. 16, pp. 1–23, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Yao, Y. Wang, Q. Li, et al., An efficient routing protocol for quantum key distribution networks, Entropy, vol. 24, no. 7, article 911, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao, Y. Zhao, X. Yu, et al., Resource assignment strategy in optical networks integrated with quantum key distribution, Journal of Optical Communications and Networking, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 995–1004, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, Y. Cao, W. Wang, et al., Resource allocation in optical networks secured by quantum key distribution, IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 56, no. 8, pp. 130–137, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao, Y. Zhao, C. Colman-Meixner, et al., Key on demand (KoD) for software-defined optical networks secured by quantum key distribution (QKD), Optics Express, vol. 25, no. 22, pp. 26453–26467, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao, Y. Zhao, Y. Wu, et al., Time-scheduled quantum key distribution (QKD) over WDM networks, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 36, no. 16, pp. 3382–3395, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Dong, Y. Zhao, X. Yu, et al., Auxiliary graph based routing, wavelength, and time-slot assignment in metro quantum optical networks with a novel node structure, Optics Express, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 5936–5952, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Dong, Y. Zhao, A. Nag, et al., Distributed subkey-relay-tree-based secure multicast scheme in quantum data center networks, Optical Engineering, vol. 59, no. 6, article 065102, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Zou, X. Yu, Y. Zhao, et al., Collaborative routing in partially-trusted relay based quantum key distribution optical networks, in Proc. 2020 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–3.

- O. Amer, W. O. Krawec, and B. Wang, Efficient routing for quantum key distribution networks, in Proc. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), IEEE, 2020, pp. 137–147.

- X. Yu, X. Liu, Y. Liu, et al., Multi-path-based quasi-real-time key provisioning in quantum-key-distribution enabled optical networks (QKD-ON), Optics Express, vol. 29, no. 14, pp. 21225–21239, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, X. Yu, Y. Zhao, et al., Routing and wavelength allocation in spatial division multiplexing based quantum key distribution optical networks, in Proc. 2020 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), IEEE, 2020, pp. 268–272. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).