1. Introduction

Biomedical term normalization—the process of mapping natural language expressions to standardized ontology concepts with machine-readable identifiers—is a cornerstone of precision medicine and biomedical research. Accurate normalization enables clinical and scientific text to be aligned with structured knowledge resources, supporting reproducible analyses and computational reasoning.

Widely adopted ontologies include SNOMED CT, which provides standardized terminology for patient care, and the Gene Ontology (GO), which supports functional annotation in gene and protein research. The Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), a structured vocabulary for describing phenotypic abnormalities associated with human disease [

1,

2,

3], plays a particularly important role in elucidating genetic disease mechanisms. With more than 18,000 terms and over 268,000 disease annotations, each linking a phenotypic feature and its ontology identifier to a specific disease, the HPO connects phenotypic, genomic, and disease knowledge. This integration enables large-scale biomedical research into the genetic basis of human disease [

4].

Successful use of the HPO for disease annotation relies on the accurate linking of each phenotype term to its corresponding ontology identifier [

2]. For example, Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2B2 is annotated with phenotypic features such as

Distal muscle weakness (HP:0002460),

Areflexia (HP:0001284), and

Distal sensory impairment (HP:0002936). Each HPO term is expressed in title case and uniquely identified by a seven-digit code prefixed with HP:. Precise alignment of the term–identifier pair is essential for ensuring semantic accuracy and interoperability, enabling downstream applications such as diagnostic decision support, cohort discovery, and automated biomedical data analysis.

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used in biomedical natural language processing (NLP) tasks such as entity recognition, relation extraction, and term normalization [

5]. Despite their broad success, LLMs often struggle with the seemingly straightforward task of biomedical term normalization [

6]. Even state-of-the-art models frequently fail to link Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms to their correct identifiers. A core limitation lies in the pre-training paradigm: autoregressive LLMs such as GPT-4 and LLaMA 3.1 are optimized for next-token prediction, not explicit fact memorization. While these models are exposed to vast biomedical corpora during pre-training, many rare biomedical concepts remain sparsely represented. As a result, model performance drops sharply across the long tail of biomedical vocabularies, where domain-specific terms are underexposed [

7]. For instance, when GPT-4 was queried for identifiers corresponding to 18,880 HPO terms, it returned the correct identifier for only 8% [

6].

Fine-tuning offers a potential remedy. Targeted adaptation using parameter-efficient methods such as LoRA has shown promise for injecting missing knowledge into large language models (LLMs) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, recent evaluations caution that these gains are often inconsistent: smaller models struggle to generalize reliably, and improvements in newly injected content may come at the cost of degrading existing knowledge—particularly when that knowledge is fragile or only weakly anchored [

8,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

A growing body of work suggests that while fine-tuning enables models to memorize new term–identifier mappings, it instills a limited ability to generalize from these mappings to unseen expressions [

16,

17]. Rather than promoting conceptual integration, fine-tuning may act as a form of rote injection, reinforcing isolated facts without building robust representations. Consequently, the success of fine-tuning appears to depend not only on the added data but also on how well the target concept is already embedded in the model’s pretraining knowledge [

17,

19]. The jury is still out on whether certain biomedical ontologies, by virtue of their innate structure or prevalence of their concepts in training data, may support broader conceptual generalization during fine-tuning than other less robust ontologies.

This raises a core question: Which biomedical terms are most likely to benefit from fine-tuning, and which are most vulnerable to degradation? We hypothesize that both improvement and degradation are systematically shaped by the model’s prior knowledge of each term–identifier pair.

To test this hypothesis, we evaluate the predictive value of three dimensions of prior knowledge, defined as the model’s ability to produce or approximate correct identifier mappings before fine-tuning:

Latent probabilistic knowledge: Hidden or partially accessible knowledge revealed through probabilistic querying of the model, even when deterministic (greedy) decoding fails [

20]. For example, if an LLM is queried 100 times and returns the correct ontology ID only 5% of the time, this indicates Latent probabilistic knowledge, distinct from not known at all.

Partial subtoken knowledge: Incomplete but non-random knowledge of the subtoken sequences comprising ontology identifiers, reflected in deterministic outputs that are close to, but not exactly, correct. For example, an LLM that predicts HP:0001259 for Ataxia instead of the correct HP:0001251 demonstrates Partial subtoken knowledge, even though greedy decoding produces an incorrect response.

Term familiarity: The likely exposure of the model to specific term–identifier pairs during pre-training, estimated using external proxies such as annotation frequency in OMIM and Orphanet [

21,

22], and identifier frequency in the PubMed Central (PMC) corpus [

23]. For example, the LLM is more likely to be familiar with the term

Hypotonia (decreased tone), which has 1,783 disease annotations in HPO, than with

Mydriasis (small pupils), which has only 25 annotations.

Across these three dimensions, Latent probabilistic knowledge, Partial subtoken knowledge, and Term familiarity, we uncover a striking pattern: terms with intermediate levels of prior knowledge, neither fully consolidated nor entirely absent [

20], are the most responsive to fine-tuning. These reactive middle terms exhibit both the largest improvements and the greatest degradations, whereas terms at the extremes remain more stable and less affected by fine-tuning. This dual effect suggests that fine-tuning is both most effective and most disruptive in regions of moderate prior knowledge. Our findings extend prior work by Pletenev et al. [

17] and Gekhman et al. [

19,

20], and underscore the importance of considering term susceptibility to fine-tuning when attempting knowledge injection.

This raises a core question: Which biomedical terms are most likely to benefit from fine-tuning, and which are most vulnerable to degradation? We hypothesize that both improvement and degradation are systematically shaped by the model’s prior knowledge of each term–identifier pair.

To test this hypothesis, we evaluate the predictive value of three dimensions of prior knowledge, defined as the model’s ability to produce or approximate correct identifier mappings before fine-tuning:

Latent probabilistic knowledge: Hidden or partially accessible knowledge revealed through probabilistic querying of the model, even when deterministic (greedy) decoding fails [

20]. For example, if an LLM is queried 100 times and returns the correct ontology ID only 5% of the time, this indicates Latent probabilistic knowledge, distinct from not known at all.

Partial subtoken knowledge: Incomplete but non-random knowledge of the subtoken sequences comprising ontology identifiers, reflected in deterministic outputs that are close to, but not exactly, correct. For example, an LLM that predicts HP:0001259 for Ataxia instead of the correct HP:0001251 demonstrates Partial subtoken knowledge, even though greedy decoding produces an incorrect response.

Term familiarity: The likely exposure of the model to specific term–identifier pairs during pre-training, estimated using external proxies such as annotation frequency in OMIM and Orphanet [

21,

22], and identifier frequency in the PubMed Central (PMC) corpus [

23]. For example, the LLM is more likely to be familiar with the term

Hypotonia (decreased tone), which has 1,783 disease annotations in HPO, than with

Mydriasis (small pupils), which has only 25 annotations.

Across these three dimensions—latent probabilistic knowledge, partial subtoken knowledge, and term familiarity—we uncover a striking pattern: terms with intermediate levels of prior knowledge, neither fully consolidated nor entirely absent [

20], are the most responsive to fine-tuning. These reactive middle terms exhibit both the largest improvements and the greatest degradations, whereas terms at the extremes remain more stable and less affected. This dual effect suggests that fine-tuning is both most effective and most disruptive in regions of moderate prior knowledge. Our findings extend prior work by Pletenev et al. [

17] and Gekhman et al. [

19,

20], and underscore the importance of considering a term’s amenability to fine-tuning when designing knowledge injection strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the materials and methods, including the experimental setup, probabilistic querying protocol, subtoken analysis, and familiarity scoring.

Section 3 presents the results of our evaluation of fine-tuning performance and the predictive value of the three dimensions of prior knowledge.

Section 4 discusses the implications of these findings, including how latent knowledge and term amenability shape fine-tuning outcomes, and outlines directions for future research.

Section 5 concludes with practical recommendations for designing effective knowledge injection strategies for biomedical term normalization.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and Fine-Tuned Performance of LLaMA 3.1 8B on HPO Term Normalization

The baseline LLaMA 3.1 8B model demonstrated significantly higher accuracy on the curated test set of 799 clinically relevant HPO terms compared to the full HPO vocabulary. When evaluated on all 18,988 HPO terms, the model correctly linked only 96 terms (0.5%), whereas on the curated test set, it correctly linked 32 terms (4.0%). A chi-square test confirmed that this difference was highly significant (). This suggests that the curated test terms represent more common clinical terms that the model was more likely to have encountered during pretraining, making them easier to normalize than the broader, rarer long-tail terms in the complete HPO.

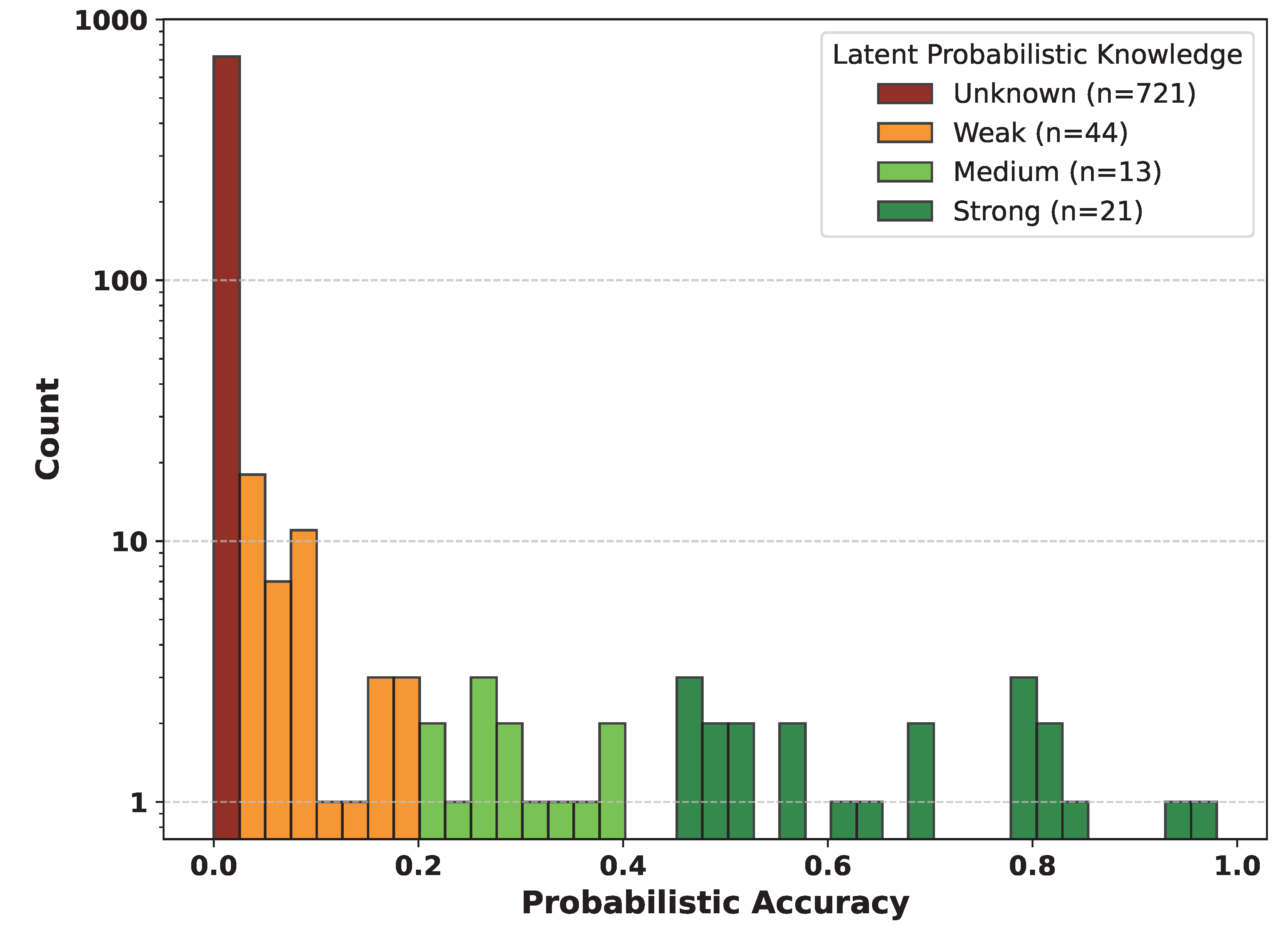

Figure 1.

Distribution of latent probabilistic knowledge across 799 HPO terms. Probabilistic accuracy was estimated from 50 stochastic model outputs at temperature 1.0 and binned as Unknown, Weak, Medium, or Strong. The y-axis is logarithmic. Most terms were classified as Unknown.

Figure 1.

Distribution of latent probabilistic knowledge across 799 HPO terms. Probabilistic accuracy was estimated from 50 stochastic model outputs at temperature 1.0 and binned as Unknown, Weak, Medium, or Strong. The y-axis is logarithmic. Most terms were classified as Unknown.

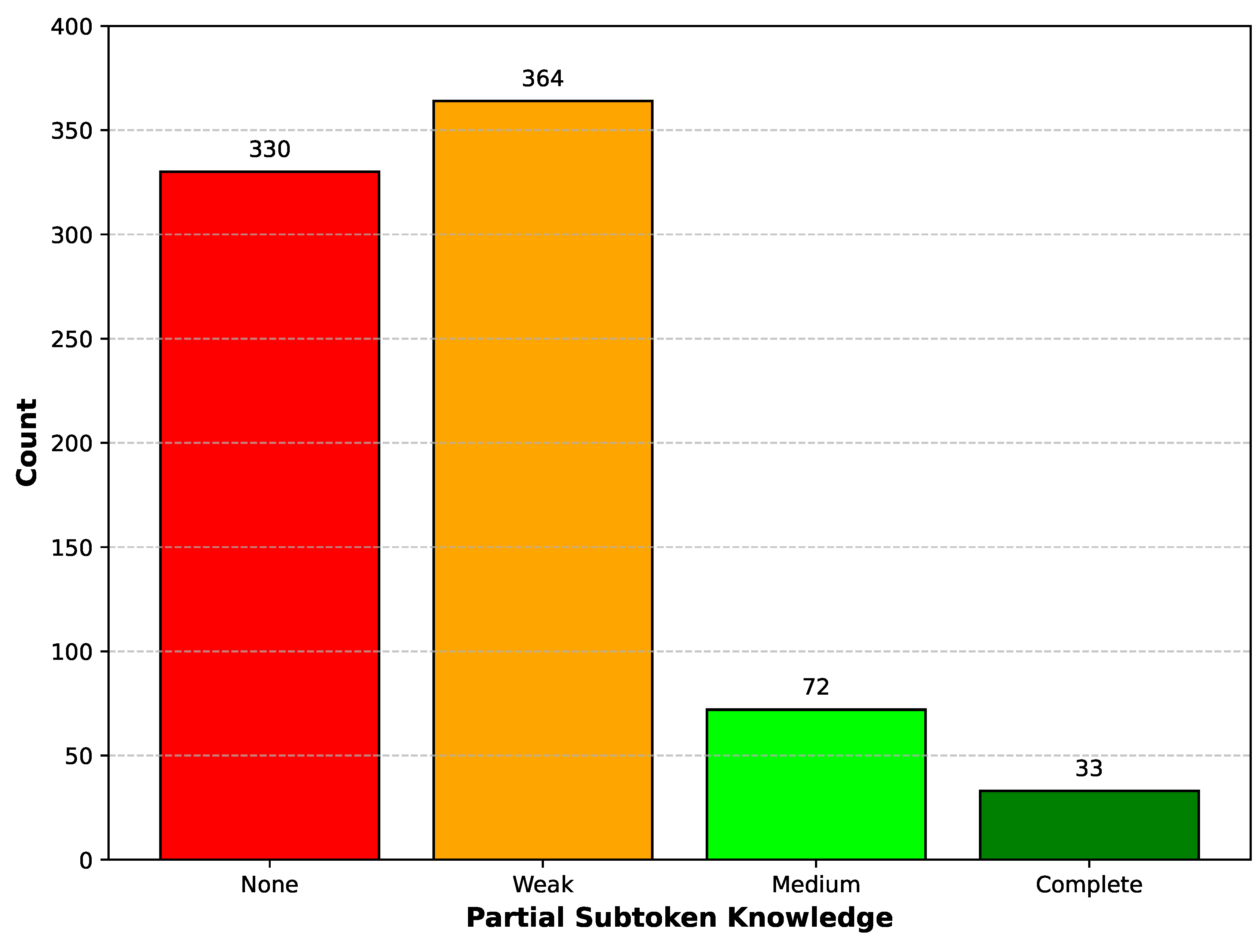

Figure 2.

Partial subtoken knowledge categories for predicted HPO identifiers. Bars show counts of terms with None (no matching subtokens), Weak (1 of 3 subtokens match), Medium (2 of 3 match), or Complete (all 3 subtokens match). The 7-digit HPO identifier is tokenized into three numeric subtokens by LLaMA 3.1 in the format of 123-456-7.

Figure 2.

Partial subtoken knowledge categories for predicted HPO identifiers. Bars show counts of terms with None (no matching subtokens), Weak (1 of 3 subtokens match), Medium (2 of 3 match), or Complete (all 3 subtokens match). The 7-digit HPO identifier is tokenized into three numeric subtokens by LLaMA 3.1 in the format of 123-456-7.

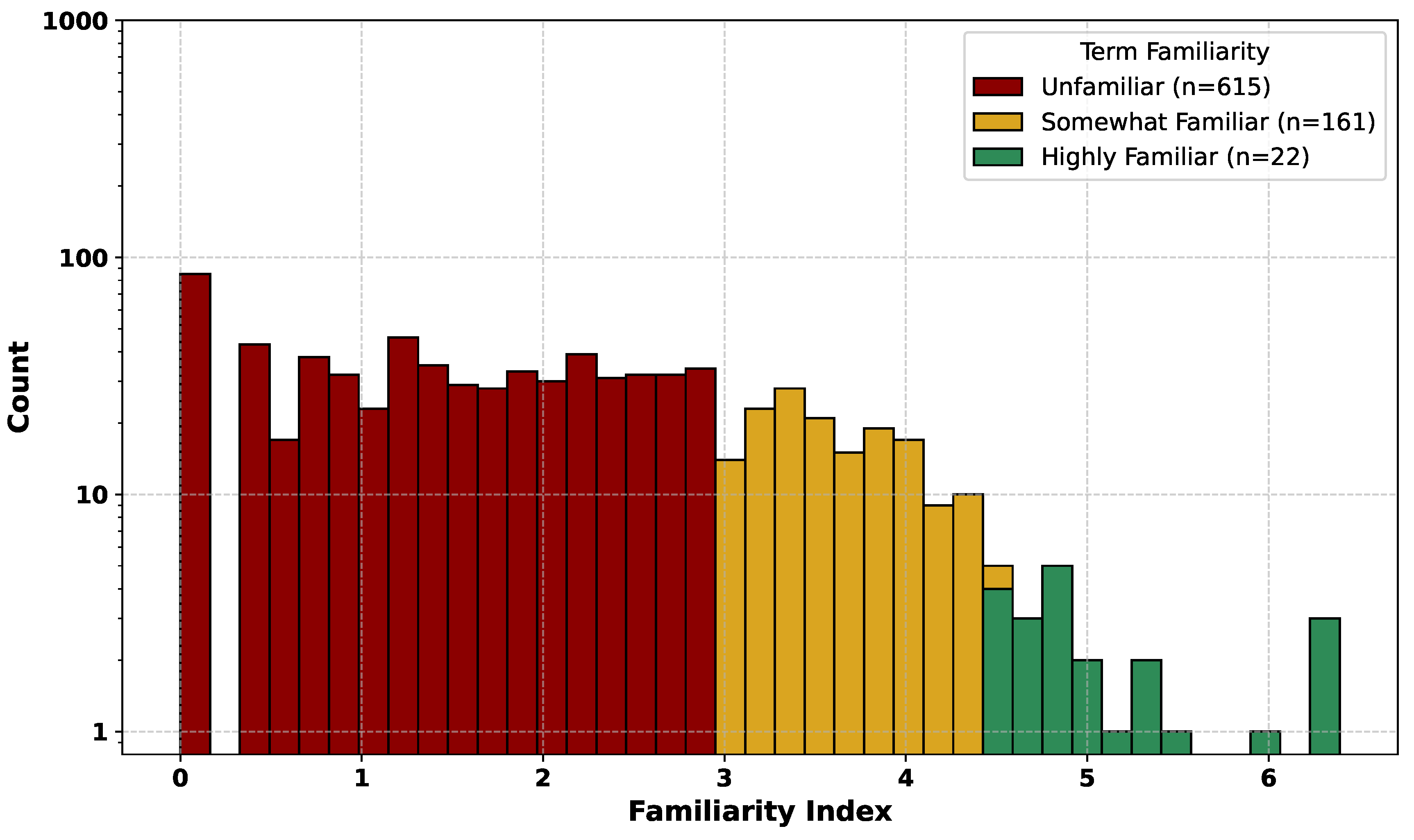

Figure 3.

Distribution of term familiarity among 799 HPO terms. Familiarity is calculated from the combined frequency of disease annotations and PubMed Central (PMC) identifier counts. Bins are Unfamiliar, Somewhat Familiar, and Highly Familiar. The y-axis is logarithmic.

Figure 3.

Distribution of term familiarity among 799 HPO terms. Familiarity is calculated from the combined frequency of disease annotations and PubMed Central (PMC) identifier counts. Bins are Unfamiliar, Somewhat Familiar, and Highly Familiar. The y-axis is logarithmic.

Fine-tuning substantially improved model performance on the curated set of 799 HPO terms. The baseline model correctly linked 32 terms (4.0%), whereas the fine-tuned model correctly linked 118 terms (14.8%). This represents a more than three-fold improvement in deterministic accuracy. A chi-square test confirmed that the increase in correct mappings after fine-tuning was highly significant ().

3.2. Latent Probabilistic Knowledge Predicts Fine-Tuning Success

Latent probabilistic knowledge, as described in Materials and Methods and adapted from Gekhman et al. [

20], was quantified by computing the proportion of correct responses across 50 probabilistic queries (temperature = 1.0). Each term was classified into one of four categories:

Unknown,

Weak,

Medium, or

Strong (

Figure 1).

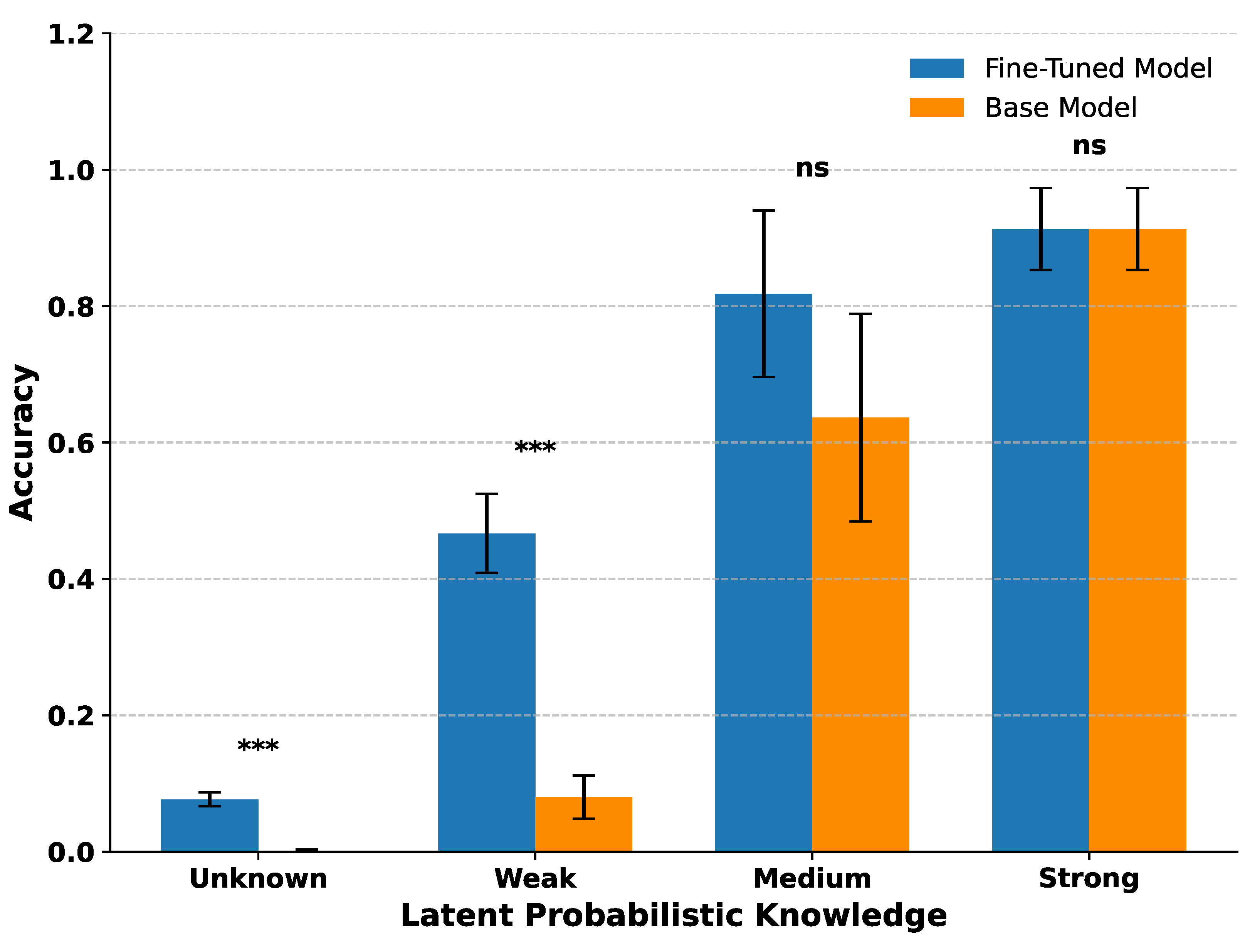

Figure 4 shows the mean deterministic accuracy of both the base and fine-tuned models for each latent probabilistic knowledge category, with standard error bars and significance markers from two-sample t-tests.

Fine-tuning significantly improved accuracy for terms with Weak latent probabilistic knowledge () and modestly for those classified as Unknown (), though absolute accuracy for Unknown terms remained low. For terms with Medium latent probabilistic knowledge, accuracy improvements did not reach statistical significance, and for Strong latent probabilistic knowledge, both models already performed near ceiling levels with no measurable gain.

These results suggest that fine-tuning is most beneficial for terms where the model possesses partial but incomplete latent probabilistic knowledge, the hypothesized reactive middle. Gains are limited for completely unknown terms and negligible for strongly represented terms.

Figure 4.

Fine-tuning effects across latent probabilistic knowledge categories. Mean deterministic accuracy of base and fine-tuned models grouped by latent knowledge level (Unknown, Weak, Medium, Strong). Fine-tuning yielded the largest gains for Weak terms, with smaller improvements for Unknown. No significant changes were observed for Medium or Strong terms. Error bars show standard errors; t-test significance: *** indicates , ns indicates not significant.

Figure 4.

Fine-tuning effects across latent probabilistic knowledge categories. Mean deterministic accuracy of base and fine-tuned models grouped by latent knowledge level (Unknown, Weak, Medium, Strong). Fine-tuning yielded the largest gains for Weak terms, with smaller improvements for Unknown. No significant changes were observed for Medium or Strong terms. Error bars show standard errors; t-test significance: *** indicates , ns indicates not significant.

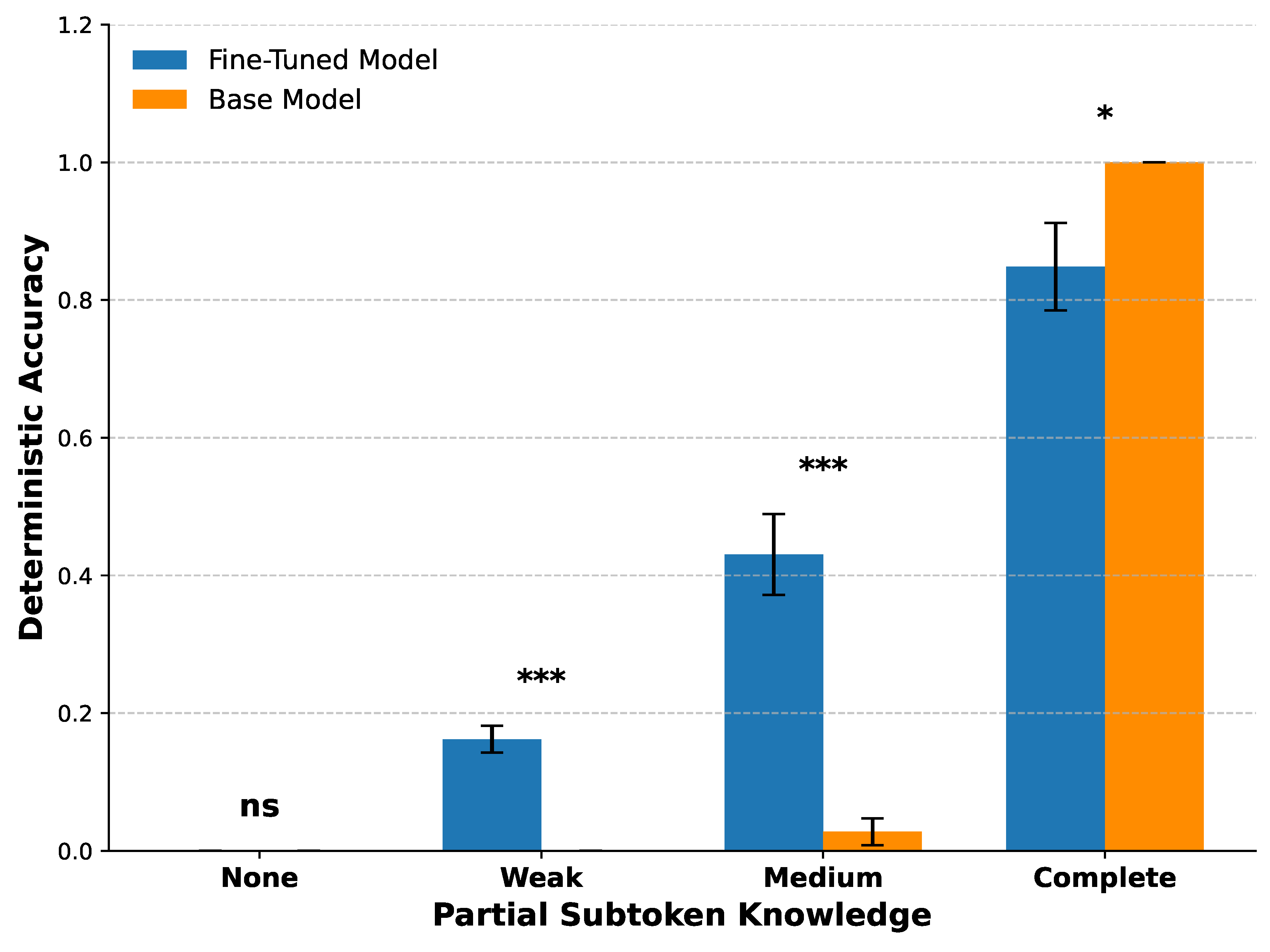

3.3. Partial Subtoken Knowledge Predicts Fine-Tuning Success

The LLaMA 3.1 tokenizer divides each 7-digit HPO identifier into three numeric subtokens in the format “123–456–7.” We assessed partial knowledge by comparing the model’s predicted identifier against the ground truth identifier at the subtoken level. Based on the number of correctly predicted numeric subtokens (0–3), each term was assigned to one of four Partial subtoken knowledge categories: None, Weak, Medium, or Complete.

Fine-tuning significantly improved deterministic accuracy in the

Weak and

Medium categories (p < 0.001), but showed no improvement in the

None category where both models performed poorly. In the

Complete category, the base model slightly outperformed the fine-tuned model (p < 0.05), indicating mild degradation of already well-consolidated knowledge. These results suggest that fine-tuning is most effective when partial knowledge is present but not yet fully established (

Figure 5).

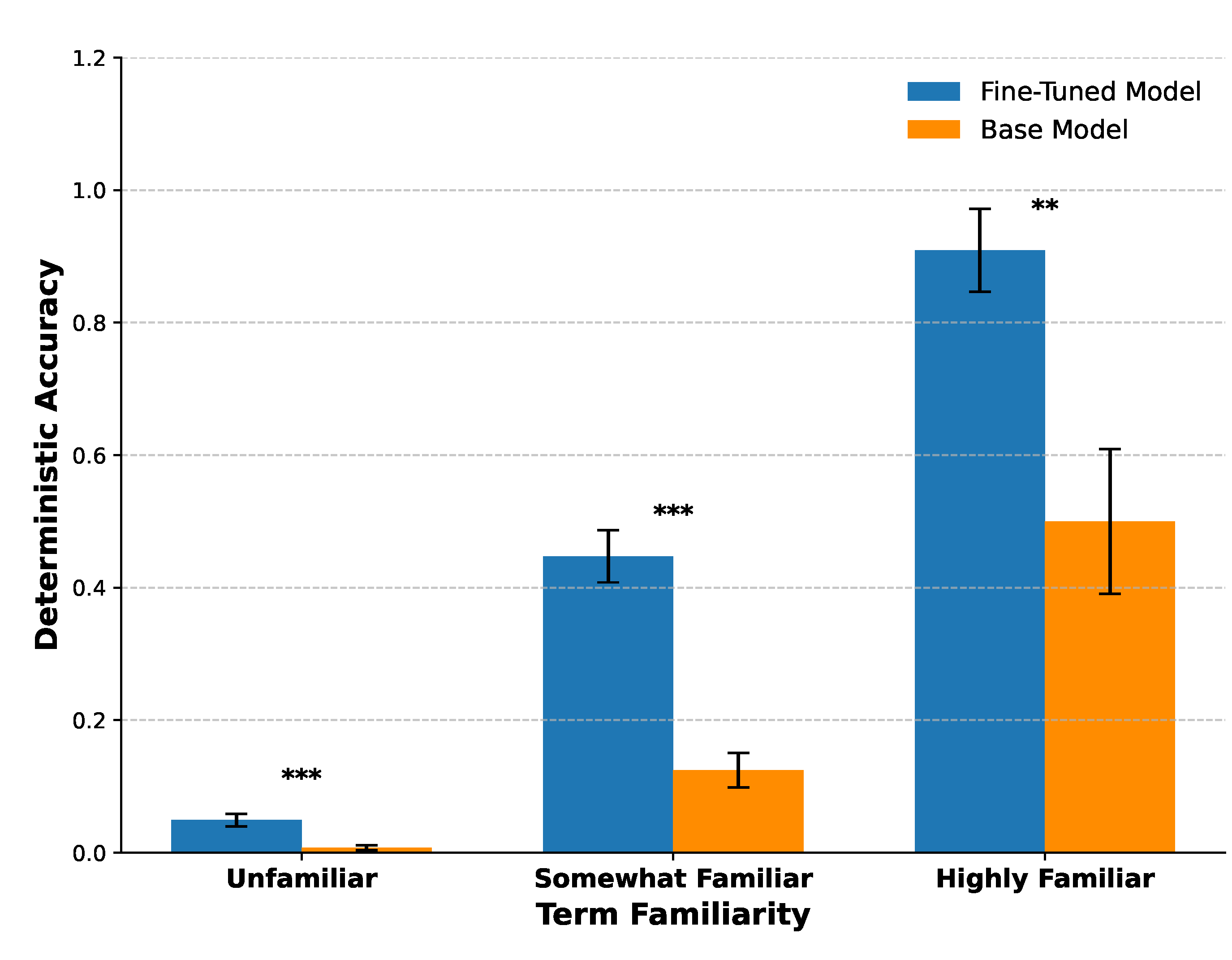

3.4. Term familiarity Predicts Fine-Tuning Success

We used the Term familiarity Index, a combined measure of phenotype annotation frequency and PubMed Central (PMC) identifier frequency, as a proxy for prior model exposure to HPO term–identifier pairs during pretraining. Fine-tuning significantly improved deterministic accuracy for both the Somewhat Familiar and Highly Familiar bins (two-sample t-tests, and , respectively). While relative gains were statistically significant for Unfamiliar terms, these terms contributed little to the overall increase in correct mappings due to their low absolute accuracy.

These results indicate that terms with moderate to high pretraining exposure account for the majority of fine-tuning gains, whereas rarely seen terms remain challenging to normalize even after fine-tuning (

Figure 6).

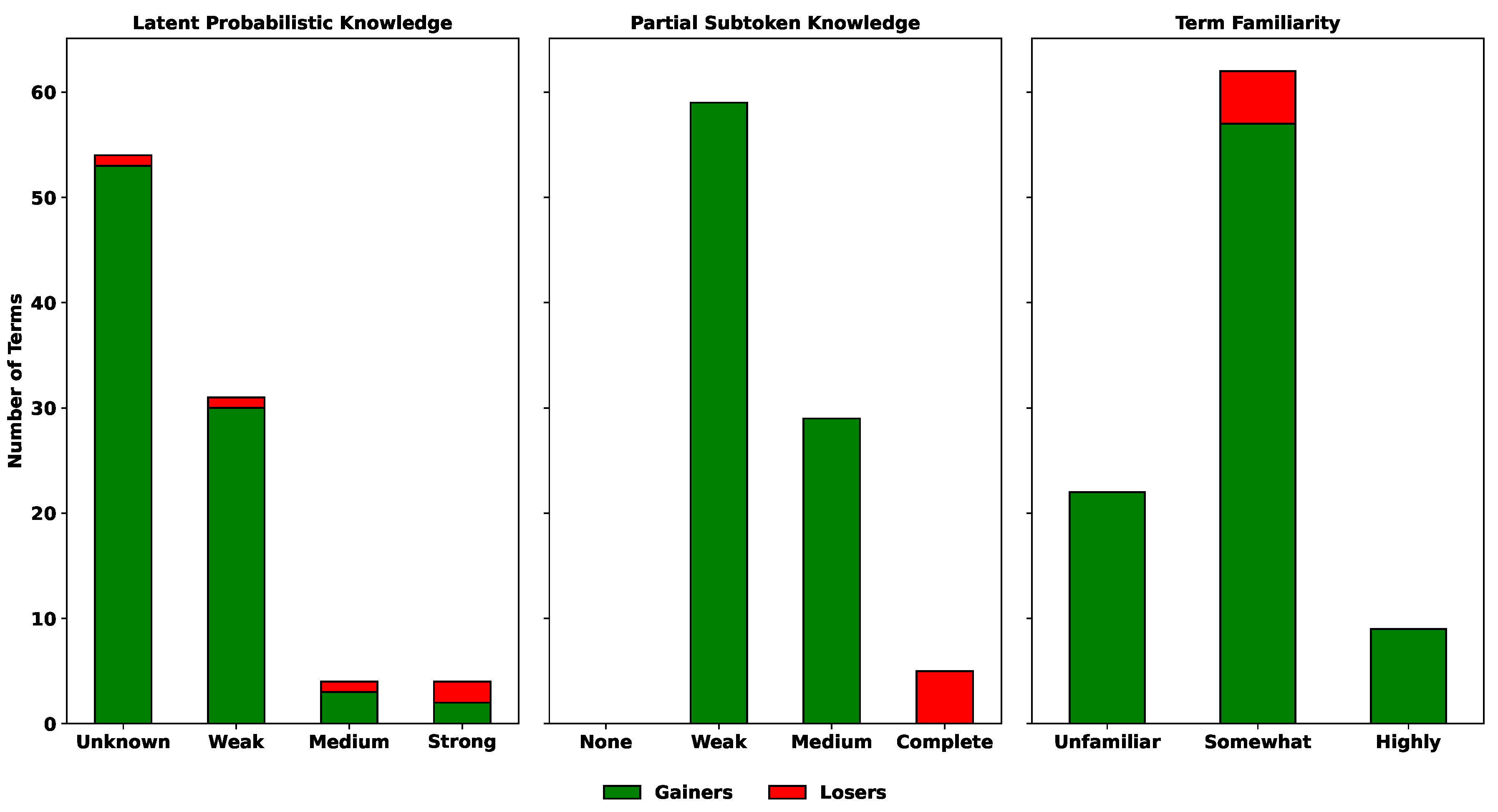

3.5. Positive and Negative Knowledge Flows during Fine-Tuning

Pletenev et al. [

17] have highlighted that fine-tuning can simultaneously introduce new knowledge and degrade existing knowledge. To quantify these effects, we classified each term as a

Gainer (incorrect before but correct after fine-tuning) or a

Loser (correct before but incorrect after). Terms that remained consistently correct or incorrect are not shown in

Figure 7.

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the majority of gains occurred in the

Unknown and

Weak bins of latent probabilistic knowledge, the

Weak and

Medium bins of partial subtoken knowledge, and the

Somewhat Familiar bin of term familiarity. These categories correspond to terms that were neither fully consolidated nor entirely novel, consistent with the reactive middle effect described earlier.

Losses were relatively rare but appeared across multiple bins. In Partial subtoken knowledge, losses occurred most often in the Complete bin, indicating that even fully known identifiers can degrade during fine-tuning. Similarly, smaller numbers of losses were observed in the Medium and Strong bins of Latent probabilistic knowledge and in the Highly Familiar bin of Term familiarity, suggesting that well-learned terms are not completely immune to negative knowledge flows.

Overall, fine-tuning produced a net positive knowledge transfer, with gains outnumbering losses in nearly all categories. However, the presence of losses in highly familiar and fully known terms underscores the risk of performance degradation during knowledge injection.

Figure 7.

Positive and negative knowledge flows during fine-tuning. Stacked bars show counts of terms that became correct (Gainers, green) or became incorrect (Losers, red) after fine-tuning. Terms with no change (Persistent Error or Robustly Correct) are omitted. Chi-square tests indicate significant differences in the distribution of gainers and losers across Latent Probabilistic Knowledge ((3) = 20.29, ) and Partial Subtoken Knowledge ((2) = 93.0, ), but not across Term Familiarity ((2) = 2.64, ).

Figure 7.

Positive and negative knowledge flows during fine-tuning. Stacked bars show counts of terms that became correct (Gainers, green) or became incorrect (Losers, red) after fine-tuning. Terms with no change (Persistent Error or Robustly Correct) are omitted. Chi-square tests indicate significant differences in the distribution of gainers and losers across Latent Probabilistic Knowledge ((3) = 20.29, ) and Partial Subtoken Knowledge ((2) = 93.0, ), but not across Term Familiarity ((2) = 2.64, ).

4. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the success of fine-tuning in improving term-to-identifier linking in biomedical ontologies is systematic rather than random and is strongly influenced by the model’s prior knowledge of each term–identifier pair. We evaluated three distinct forms of prior knowledge, latent probabilistic knowledge, partial subtoken knowledge, and term familiarity, and found all three to be predictive of fine-tuning outcomes. Latent probabilistic knowledge refers to hidden or weakly accessible knowledge revealed through stochastic sampling, even when deterministic decoding fails. Partial subtoken knowledge measures the model’s ability to reproduce components of an identifier’s numeric subtokens correctly, despite failing to generate the complete identifier. Term familiarity captures the degree of prior exposure during pretraining, estimated from annotation frequencies in biomedical databases and identifier frequencies in PubMed Central.

A consistent pattern emerged: terms with intermediate levels of prior knowledge, those neither fully unknown nor well consolidated, were the most responsive to fine-tuning. This reactive middle group exhibited both the largest gains and the most significant losses in deterministic accuracy. Specifically, these terms were characterized by intermediate latent probabilistic knowledge (

Figure 1), intermediate partial subtoken knowledge (

Figure 2), and moderate term familiarity (

Figure 3). In contrast, terms with unknown latent knowledge showed minimal improvement, while highly familiar or strongly known terms tended to remain stable, or, in some cases, experienced slight degradation with fine-tuning.

These observations align with the theoretical frameworks proposed by Gekhman et al.[

20] and Pletenev et al.[

17], which suggest that fine-tuning can reinforce weakly consolidated representations while simultaneously destabilizing previously stored knowledge. Our findings extend this framework by quantitatively characterizing fine-tuning effects along three axes of prior knowledge, latent probabilistic knowledge, partial subtoken knowledge, and term familiarity. We show that both gains and losses are most pronounced when pre-existing knowledge is partial and unconsolidated. In contrast, when prior knowledge is strongly consolidated (e.g., highly familiar or strongly known terms) or completely absent (unknown terms), the impact of fine-tuning is comparatively small.

We find partial alignment with the results of Wang et al. [

28], who demonstrated that parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods such as LoRA can achieve high memorization performance, particularly when trained over many epochs. In their experiments, fine-tuning LLaMA 2 model with 7B parameters over 99 epochs resulted in near-perfect knowledge injection. Unlike our findings, Wang et al. reported no evidence of knowledge degradation or catastrophic forgetting during extensive fine-tuning. We used the LLaMA 3.1 8B model, fine-tuned with Unsloth for only three epochs. This limited training capacity likely contributed to both the modest overall accuracy gains and the performance degradations observed in previously known terms. Unlike Wang et al. [

28], we were not able to reach 99 training epochs.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we evaluated only a single model architecture, LLaMA 3.1 8B, and our findings may not generalize to larger models or those pretrained on domain-specific biomedical corpora. Second, we focused exclusively on the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO); it remains unknown whether similar patterns would emerge for other biomedical ontologies such as the Gene Ontology (GO), SNOMED CT, or RxNorm. Third, while our ground truth test set of 799 terms was derived from real-world clinical notes, it represents only a small subset of the full HPO vocabulary. Moreover, because the training set included all 18,988 terms while evaluation was limited to 799 terms, a training–test mismatch may have influenced the results. Finally, our fine-tuning procedure was constrained to three epochs with five prompt variants per term. Alternative strategies, including broader prompt diversity, longer training durations, or expanded context windows, may yield different outcomes.

We also did not explicitly address the ongoing debate over whether parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods such as LoRA enable true generalization or merely reinforce memorized associations [

15]. Our findings suggest that fine-tuning primarily acts as a structured memorization mechanism, improving mappings for terms already partially known or inconsistently encoded. However, we did not evaluate whether PEFT promotes deeper semantic abstraction beyond the training set.

4.2. Future Work

Future research should investigate whether the observed patterns of fine-tuning responsiveness generalize across other biomedical ontologies, different model sizes, and alternative training strategies. It will be valuable to systematically compare fine-tuning techniques, including QLoRA, Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), and full-model fine-tuning, to assess their effects on knowledge injection and retention.

Additionally, future work should examine how temperature settings influence the estimation of latent probabilistic knowledge, potentially improving our ability to predict fine-tuning outcomes. A particularly promising direction is the exploration of targeted fine-tuning approaches that focus specifically on a reactive middle, that is, terms where model prior knowledge is partial and unconsolidated. Such targeted strategies may provide greater efficiency and higher accuracy while minimizing degradation of well-consolidated mappings.

Finally, we plan to study the velocity of fine-tuning, investigating whether certain terms adapt more rapidly to training than others and identifying the predictive factors that govern this responsiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the effectiveness of fine-tuning for term-to-identifier linking in biomedical ontologies is not uniform but is systematically governed by a model’s prior knowledge of term-identifier pairs. We evaluated three distinct dimensions of prior knowledge, latent probabilistic knowledge, partial subtoken knowledge, and term familiarity, and found each to be predictive of fine-tuning outcomes.

Our central finding is the identification of a reactive middle: terms with intermediate levels of prior knowledge undergo the most substantial changes during fine-tuning, showing both the largest performance gains and the greatest degradations. In contrast, terms that are either well-consolidated or completely unknown remain largely unaffected by fine-tuning.

These results challenge the assumption that fine-tuning is universally beneficial. Instead, they highlight its dual nature, acting both as a corrective mechanism for incompletely learned mappings and as a potentially disruptive force for fragile but previously accurate knowledge. By explicitly modeling and quantifying prior knowledge, we can better anticipate term-level susceptibility to and vulnerability from fine-tuning, enabling the development of more efficient strategies that maximize accuracy gains while minimizing knowledge degradation.