1. Introduction

As environmental challenges grow and standards shift, companies are increasingly prioritizing sustainability in their strategic and operational approaches. A significant advancement in this area is the increasing implementation of GHRM, a framework that integrates environmental factors into key HR activities like recruitment and selection, performance management and appraisal, training and development, rewards and compensation, and empowerment. The goal is to encourage environmentally friendly behavior while synchronizing workforce practices with larger ecological aims [

1]. Research has progressively shown that GHRM practices relate to GEB, which includes both voluntary and job-related behaviors that promote sustainability in the workplace [

2,

3]. However, little research has been done on the specific mechanisms through which GHRM promotes these behaviors, particularly with regard to the internal resources that support this behavioral shift. A theoretical framework that offers significant insights is GHC, which is the culmination of environmental knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values acquired through organizational initiatives. GHC can serve as a catalyst for eco-friendly innovation in corporate environments and allows individuals to play a significant role in sustainability initiatives [

4]. It encompasses not only technical know-how and environmental consciousness, but also the driving forces behind long-lasting environmentally friendly behavior [

5]. Prior research has demonstrated that GHC can impact the relationship between GHRM and broader organizational outcomes, such as green innovation and environmental performance [

6,

7]. Even with these results, there has been little empirical focus on GHC’s influence in the more precise connection between GHRM practices and GEB.

To address this research gap, the present study investigates whether GHC serves as a mediating factor in the connection between GHRM and GEB. By examining this relationship, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how environmental values and capabilities embedded within the workforce can translate HRM initiatives into tangible behavioral outcomes offering both theoretical advancement and practical direction for sustainability-oriented organizational development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Human Resource Management

GHRM is now widely acknowledged as a strategic approach that synchronizes environmental sustainability requirements with human resource functions. GHRM aims to develop workforce capabilities that support ecological objectives and strengthen an organizational culture focused on sustainability by integrating environmental priorities into hiring, training, performance reviews, and employee engagement [

8,

9]. These practices have been shown to improve environmental performance as well as employee engagement, well-being, and a sense of shared responsibility for sustainable development goals [

10].

The impacts of GHRM are especially noticeable in service-oriented industries, where the actions of daily employees are crucial in determining the environmental impact of the organization [

11]. Research indicates that regular implementation of GHRM practices promotes the growth of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, which enhances environmental performance at the individual and organizational levels. Leadership support and managerial commitment to environmental issues enhance the impact of GHRM by creating a culture where sustainability is integrated into daily operations [

12,

13].

Additionally, businesses that invest in eco-innovation and incorporate GHRM into larger environmental strategies are more likely to see noticeable improvements in sustainability outcomes. These strategic alignments reinforce the relationship between GHRM and enhanced environmental performance by acting as mediators [

14].

The strategic significance of GHRM in creating environmentally conscious organizations is highlighted throughout the literature. It is essential to attaining long-term organizational resilience and environmental stewardship because of its ability to promote eco-friendly behaviors, foster innovation, and enhance overall sustainability performance.

2.2. Green Employee Behavior

GEB includes a broad range of workplace activities that support environmental sustainability, including waste reduction, energy conservation, and involvement in eco-innovation projects. As a behavioral result, GEB is essential for enhancing an organization's environmental performance and advancing long-term sustainability goals [

15].

The growth and stability of GEB are influenced by a number of organizational and individual factors, including formal sustainability policies, environmental context, and leadership commitment [

16]. These actions can be mandatory, like adhering to environmental laws, or optional, like making the independent decision to adopt eco-friendly practices. Each type is influenced by unique motivating factors and workplace interactions. Research continuously shows that when employees feel strong organizational support and work in an environment that blatantly prioritizes environmental responsibility, they are more likely to engage in GEB [

17,

18].

Motivational conditions like a sense of duty toward the environment and the awareness of a sustainable organizational atmosphere have demonstrated their role in connecting pro-environmental beliefs with real actions. This indicates that both internal traits and external incentives are essential to initiate and maintain environmentally responsible behavior [

19].

Significantly, participating in GEB has been associated with improved employee well-being. Workers involved in sustainability initiatives frequently express a heightened sense of purpose and psychological satisfaction, emphasizing the possibility of mutually beneficial outcomes for both organizational objectives and personal achievements [

20].

The literature collectively depicts GEB as a multifaceted and evolving concept influenced by the interaction of individual, organizational, and psychological elements. GEB acts not only as a sign of environmental dedication but also as a means by which organizations can encourage a more profound incorporation of sustainability into routine operations.

2.3. Green Human Capital

GHC has become significant as an essential intangible asset for organizations dedicated to promoting environmental sustainability. Characterized by the environmental knowledge, skills, competencies, and eco-aware values developed in employees, GHC empowers the staff to actively promote green innovation and enhance environmental performance. It is progressively viewed as a fundamental component of green intellectual capital and an essential facilitator of both ecological and economic value generation within companies [

21].

GHC enhances individuals' ability to participate in sustainability initiatives, leading to more adaptable and effective solutions to environmental issues. Its advancement is frequently propelled by targeted investments in training, education, and personnel practices that highlight environmental awareness and technical skills in sustainable operations [

22]. Research indicates that entities with elevated GHC levels tend to adopt eco-efficient practices, embrace cleaner technologies, and promote innovations that are in line with sustainability objectives [

23].

Beyond internal outcomes, GHC has been identified as a mediating factor in the relationship between environmental policy implementation and sustainable performance. GHC supports both green innovation and industry upgrading, enabling organizations to remain competitive while meeting environmental standards [

24].

Moreover, the influence of GHC extends to broader organizational metrics, including competitive advantage, financial returns, and corporate social responsibility. These associations underscore its strategic significance in fostering long-term sustainable development [

25]. Importantly, support from top management has been shown to be instrumental in building GHC, as leadership commitment creates the necessary conditions for embedding environmental values into workforce development and operational practices [

26].

Empirical findings affirm the role of human capital, including its green dimensions, in promoting green growth and long-term sustainability, especially in emerging and developing economies [

27,

28]. The accumulation of GHC enables economies to transition more effectively toward low-carbon, knowledge-based systems that prioritize environmental resilience [

29,

30].

In summary, the literature consistently demonstrates that GHC is a strategic resource that supports organizational and societal efforts toward environmental sustainability by driving innovation, enhancing performance, and facilitating compliance with environmental standards.

2.4. The mediating role of GHC in the relationship between GHRM and GEB

GHRM has increasingly been recognized as a vital organizational mechanism for fostering GEB, which encompasses employees’ voluntary and task-related actions aimed at minimizing environmental harm and promoting sustainability within the workplace. A growing body of empirical research affirms that the strategic application of GHRM practices plays a significant role in fostering GEB across a variety of organizational contexts [

31,

32,

33]. These practices help shape employees' attitudes and behaviors toward the environment by creating an atmosphere where sustainability is not only valued but also internalized as a core organizational principle [

34,

35].

GHRM encourages employees to participate in voluntary green projects by integrating environmental priorities into HR operations, creating an environment that goes beyond mere compliance. This is accomplished by employing tactics like fostering a green mindset, offering pertinent training, and launching projects that enable individuals to take charge of sustainability objectives [

36,

37].

In order to shed light on how organizational practices translate into individual-level actions, factors such as perceived organizational support for sustainability, environmental motivation, and green self-efficacy have emerged as critical mediators [

38]. This relationship is further strengthened when leadership actions are in line with GHRM values; leaders who make environmental issues a priority increase the legitimacy and uptake of eco-friendly practices throughout the company [

39,

40].

Crucially, this relationship's strength has been shown in a variety of institutional and cultural contexts, indicating that it is applicable outside of particular geographic or sectoral contexts. For instance, research conducted in emerging economies shows that GHRM can significantly drive employee engagement in green behavior, even in environments with weaker regulatory frameworks, provided that organizational culture and leadership align with sustainability values [

41,

42]. Additionally, models integrating technological acceptance theory suggest that GHRM facilitates not only behavioral change but also openness to environmentally oriented innovations and tools [

43]. Evidence suggests that when organizations implement robust GHRM systems, they effectively foster a workforce equipped with the environmental knowledge and competencies required to support and lead sustainability initiatives [

44].

Empirical studies confirm that GHRM has a direct and significant impact on the development of GHC, which in turn mediates the effect of GHRM on other sustainability-related outcomes such as green innovation and environmental performance. This mediation emphasizes the role of GHC as a critical mechanism through which HR practices translate into tangible environmental results [

45]. Furthermore, the development of GHC through GHRM practices strengthens organizational commitment and employee alignment with sustainability values, thus reinforcing long-term behavioral change [

46].

Studies indicate that GHRM fosters GHC by embedding sustainability in core human resource functions such as green-oriented recruitment, training, performance evaluation, and employee involvement. These practices build a workforce that is environmentally aware, motivated, and capable of engaging in pro-environmental behaviors [

47,

48]. The enhancement of GHC, in turn, strengthens employees’ psychological readiness and technical capacity to perform green behaviors, positioning GHC as a key intermediary in this behavioral transformation [

49].

While GHRM creates the structural and motivational framework for green behavior, GHC acts as the individual-level asset that enables employees to operationalize environmental initiatives. The integration of green training and knowledge sharing as GHRM practices directly contributes to employees’ skill development, fostering consistent engagement in green behavior [

50]. Although studies often emphasize moral norms and leadership as moderators, the presence of green capabilities among employees remains a necessary condition for the successful translation of HRM initiatives into environmentally responsible outcomes [

51].

This review of research literatures emphasizes the importance of understanding the mechanisms through which GHRM influences GEB, with GHC emerging as a critical mediating variable. GHC, as the accumulation of employees’ environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes fostered by GHRM practices, is theorized to bridge the gap between organizational-level green strategies and individual-level behavioral outcomes. Investigating the mediating role of GHC is therefore essential, as it provides insight into how environmentally focused HRM systems translate into sustainable employee actions, offering a deeper explanation of the relationship between GHRM and GEB that guides more effective implementation of green initiatives within organizations.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

The conceptual framework presented reflects a growing scholarly effort to understand employee behavior in the context of organizational sustainability. It shows the influence of GHRM practices on GEB, suggesting both direct effects and indirect pathways mediated by GHC. Positioned as an intermediary construct, GHC captures the environmental competencies, awareness, and values that are fostered through deliberate HR strategies. These internalized capabilities serve as a foundation for encouraging environmentally responsible actions among employees, linking organizational practices to individual behavior in a meaningful and measurable way.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative research approach, utilizing a causal research design to investigate the mechanisms and pathways through which GHRM practices influence GEB, with GHC as a mediating variable. Mediation analysis was utilized to explore the indirect connection between GHRM practices and GEB, concentrating on uncovering the function of GHC as a possible mediating variable. This analytical method facilitated a deeper comprehension of the ways GHRM practices can affect pro-environmental behavior at work by improving employees' environmental skills.

A purposive sampling technique was employed to guarantee the contextual suitability and relevance of the data. The sample consisted of 171 regular workers from particular Iligan City food service businesses. These individuals were chosen due to their active involvement in daily operations and their keen interest in organizational procedures and sustainability initiatives. Their frontline work experiences gave them valuable perspectives on how GHRM initiatives are perceived, implemented, and carried out in their specific organizational environments. The study's evaluation of the practical effects of strategic HRM practices on environmental behavior benefited greatly from their comments.

3.2. Data Collection

A standardized survey questionnaire served as the main data collection tool for this investigation. The tool's three primary sections—GHRM practices, GHC, and GEB—all addressed one of the study's central ideas.

The Saeed et al. (2018) model [

52], from which the GHRM practices section was derived, featured five elements that are well known in the literature: green empowerment, sustainable rewards and compensation, environmentally conscious performance management and assessment, environmentally friendly training and development, and environmentally friendly hiring and selection. This section of the instrument included forty-four items: nine that assessed green recruitment and selection, eight that assessed performance management and evaluation, twelve that assessed training and development, nine that assessed rewards and compensation, and six that assessed empowerment. A five-point Likert scale was used to collect responses, where 1 meant "does not apply" and 5 meant "always applies."

The study evaluated the attitudes, skills, and environmental awareness of the workers using a five-item scale that was modified from Chen (2008) [

53]. Responses were gathered using a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 meant "strongly disagree" and 7 meant "strongly agree."

GEB was measured using a six-item scale that was modified from Huo et al. (2022) [

54] and covered a variety of aspects of environmentally conscious workplace behavior. This section employed a seven-point Likert scale, which followed the same agreement spectrum as the GHC section.

To guarantee measurement accuracy and content validity, the tool was evaluated by a university professor with experience in human resource management. After expert validation, a pilot test was carried out to evaluate the items' coherence, clarity, and alignment with the intended constructs. The pilot results validated the consistency of the measures, with each subscale obtaining Cronbach's alpha coefficients above the suggested minimum of 0.70. These results showed strong internal consistency and eliminated the need for additional item modifications.

Table 1.

Cronbach’s alphas test of reliability.

Table 1.

Cronbach’s alphas test of reliability.

| Constructs |

Items |

Cronbach's alpha |

Internal Consistency |

| GHRM |

44 |

0.964 |

Excellent |

| GHC |

24 |

0.953 |

Excellent |

| GEB |

20 |

0.950 |

Excellent |

3.3. Data Analysis

The overall suitability of the structural model was assessed by analyzing a number of commonly used goodness-of-fit indices. These indices provide a statistical basis for assessing whether the suggested relationships between the constructs are backed by empirical data and how well the suggested model fits the observed data. The Chi-square/Degrees of Freedom (χ²/df) and p-value, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were among the criteria used in this study to assess model fit. Each of these metrics offers a different perspective on model performance, allowing for a more thorough assessment of structural validity. The results of this model evaluation are presented in the discussion that follows, which also looks at potential alternatives in light of the observed alignment.

Table 2.

Model fit test.

| Fitting Index |

Model Value |

Criteria for Good fit |

Verbal interpretation |

| χ²/df |

3.023 |

>0.05 |

Acceptable |

|

p-value |

<0.001 |

> 0.05 |

Fail |

| RMSEA |

0.106 |

< 0.08 |

Fail |

| CFI |

0.734 |

> 0.90 |

Fail |

| TLI |

0.723 |

> 0.90 |

Fail |

| NFI |

0.231 |

> 0.90 |

Fail |

| SRMR |

0.064 |

< 0.08 |

Acceptable |

The χ²/df value of 3.023 shows an acceptable fit but the significant chi-square p-value suggests a misfit between the observed and predicted covariance matrices. The CFI, TLI and NFI also fails to reach the criteria of good fit which are below the suggested cutoff of 0.90. Additionally, the RMSEA exceeds the acceptable limit of 0.08, indicating poor model fit. And, SRMR value of 0.064 falls within the acceptable range. These findings highlight substantial concerns regarding the adequacy of the model.

In light of the model fit challenges identified, reconsidering the analytical approach is warranted. PLS-SEM offers a robust and flexible alternative, particularly well-suited for research that prioritizes prediction, involves complex model structures, or is constrained by smaller sample sizes. Unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM is more tolerant of multicollinearity and specification issues, making it effective in exploratory studies or when traditional methods yield unsatisfactory results.

PLS-SEM is specifically designed to model complex causal relationships and to support theory development by estimating both direct and indirect effects among latent variables [

55,

56]. In this study, PLS-SEM was applied to examine the structural relationships among GHRM practices as the independent variable, GHC as the mediating variable, and GEB as the dependent variable. This method enabled a comprehensive analysis of the strength and significance of the hypothesized paths, offering valuable insights into the predictive and mediating mechanisms embedded within the proposed model.

4. Results

Table 3.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling for each path relationship test.

Table 3.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling for each path relationship test.

| Path Relationship |

Original sample (O) |

T Statistics |

p Values |

| GHRM -> GEB |

0.063 |

0.609 |

0.542 |

| GHRM -> GHC |

0.821 |

21.820 |

<0.001* |

| GHC -> GEB |

0.803 |

10.531 |

<0.001* |

According to the path relationship test results, the green human resource management do not have a direct effect on green employee behavior with a low coefficient (0.063), low t-statistic (0.609) and high p-value (> 0.05). While GHRM practices may play a role in fostering a green workplace, their direct influence on employee behavior is negligible in this model.

The path relationship between the green human resource management to green human capital indicates a highly significant and demonstrates a strong positive effect of GHRM practices on the development of green human capital with a strong path coefficient (0.821), high t-statistic (21.82), and a p-value of < 0.001. This indicates that green-focused HRM strategies effectively build the environmental competencies of employees.

In the path relationship between green human capital and green employee behavior, the result shows a strong path coefficient (0.803), high t-statistic (10.531), and a p-value of < 0.001 which indicate a strong and statistically significant positive relationship. This suggests that employees with higher environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes are much more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace.

Table 4.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling mediation analysis.

Table 4.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling mediation analysis.

| GHRM -> GHC -> GEB |

| Effect Type |

Original sample (O) |

T Statistics |

p Values |

| Total Effect |

0.722 |

10.496 |

<0.001* |

| Direct Effect |

0.063 |

0.609 |

0.542 |

| Indirect Effect |

0.659 |

8.987 |

<0.001* |

The total effect of GHRM practices on GEB was found to be strong and statistically significant (β = 0.722, t = 10.496, p-value < 0.001). This indicates that GHRM initiatives are meaningfully associated with increased environmentally responsible behavior among employees. However, it is critical to recognize that this total effect encompasses both direct and indirect pathways, and thus requires further examination to understand the underlying mechanism of influence.

The direct effect of GHRM on GEB was not statistically significant (β = 0.063, t = 0.609, p-value = 0.542). This means that green human resource management practices do not directly cause employees to adopt green behaviors. The result implies that green practices alone may create awareness, but not action, unless they are internalized.

The indirect effect of GHRM on GEB, mediated by GHC, was found to be highly significant (β = 0.659, t = 8.987, p-value < 0.001). This confirms that the relationship between GHRM and GEB is fully mediated by GHC. This means that GHRM practices influence behavior only when they foster the development of environmental competencies. GHC which comprises knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to environmental responsibility serves as the internal mechanism through which employees are empowered to act in environmentally sustainable ways.

Table 4.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling mediation analysis.

Table 4.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling mediation analysis.

| GHRM -> GHC -> GEB |

| Original sample (O) |

T Statistics |

p-value |

Type of Mediation |

| 0.659 |

8.987 |

<0.001* |

Full Mediation |

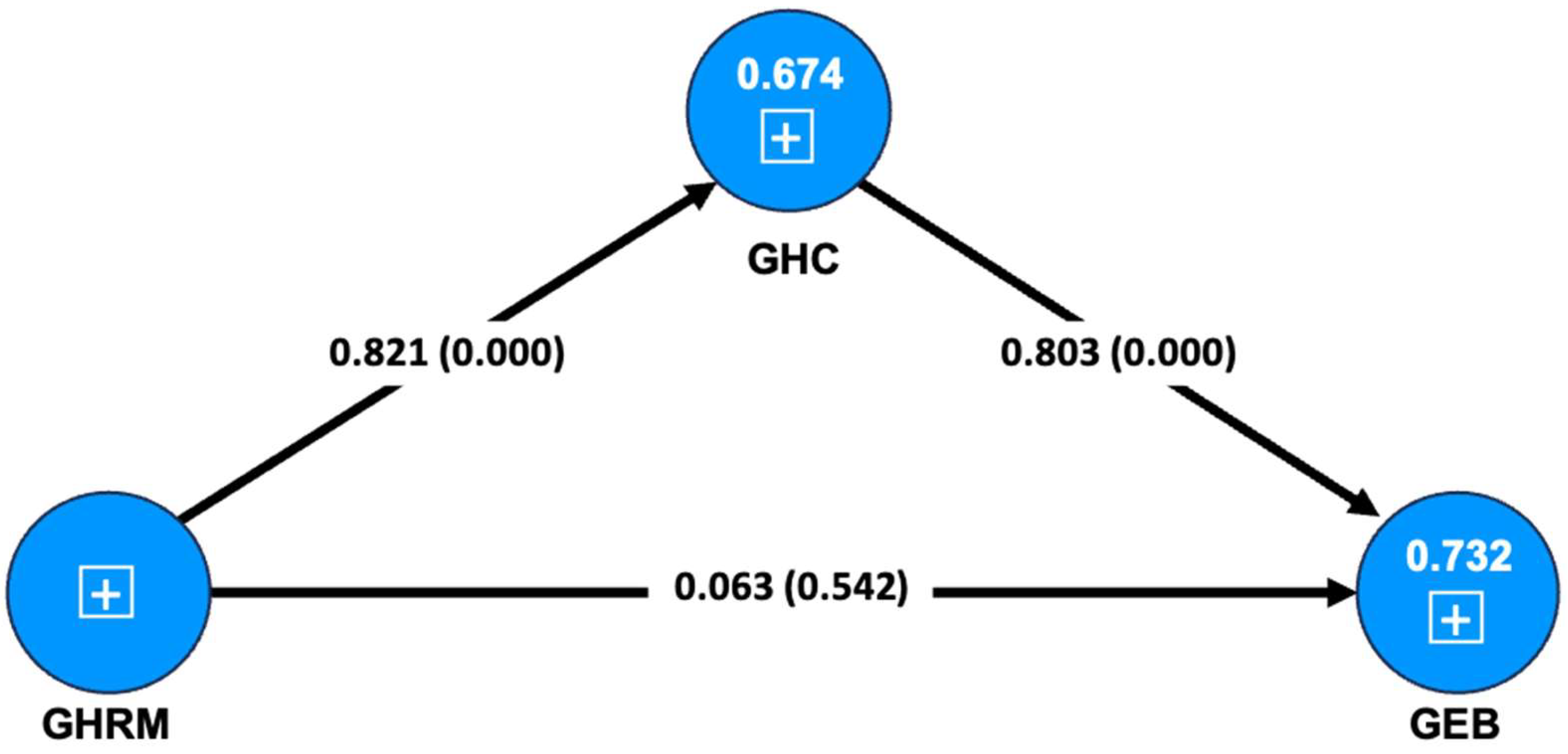

Figure 2.

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis Plot.

Figure 2.

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis Plot.

The findings confirm that while GHRM practices are significantly associated with GEB, this relationship is fully mediated by GHC. The strong path coefficient (β = 0.821), substantial t-value (21.82), and a highly significant p-value (< 0.001) indicate that GHRM practices do not exert a direct influence on employee green behavior. Rather, its contributions operate indirectly through the development of GHC which collectively comprises employees’ environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

5. Discussion

This finding highlights the transformational role of GHC as a mechanism that converts human resource practices into tangible behavioral outcomes. Employees are unlikely to adopt pro-environmental behaviors solely because green policies exist; instead, they must first internalize green values and develop the competencies required to act sustainably. This is supported by evidence showing that GHRM practices such as green training, environmental awareness programs, and sustainability-focused recruitment contribute directly to the formation of GHC, which in turn empowers employees to engage in environmentally responsible actions [

4,

6,

7].

The mediating function of GHC is further reinforced by research emphasizing that GEB emerges not just from organizational mandates but from the individual-level environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes cultivated through strategic HR practices [

5,

32]. Moreover, studies have shown that even when organizations have strong managerial support or well-structured green policies, employees are less likely to consistently engage in pro-environmental behavior unless they personally internalize the necessary environmental knowledge, skills, and values that form the core of Green Human Capital [

48,

49].

The full mediation implies that GHRM practices are effective only when they successfully foster green capabilities among employees. The direct path from GHRM to GEB being insignificant supports the view that policy alone is insufficient to drive change. Strategic capability-building must therefore be at the core of sustainable human resource initiatives. This result is supported by evidence showing that GHRM practices lead to sustainable outcomes primarily through the development of GHC, which equips employees with the competencies and motivation needed to engage in green behavior. Studies have demonstrated that without fostering these green capabilities, the direct effect of GHRM on GEB tends to diminish, highlighting the crucial mediating role of GHC in translating policy into action [

47,

50]. This supports the view that policy alone is insufficient to drive change which suggests that strategic capability-building through GHC must be embedded within human resource initiatives to ensure behavioral transformation.

5.1. Implications

In light of the study’s findings, it is strongly recommended that administrators and human resource practitioners prioritize the development of GHC as a strategic component of sustainability initiatives. Given that GHRM practices influence GEB only through GHC, investing in programs that enhance employees’ environmental competencies is essential. This can be achieved through structured green training, continuous learning modules, and employee empowerment initiatives that cultivate environmental knowledge, skills, and values. Additionally, integrating environmental goals into performance evaluation and providing recognition for green contributions can help reinforce sustainable behaviors in the workplace. By doing so, organizations can create a culture of sustainability that is rooted in capacity-building and internal motivation.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Even though the study was meticulously planned to meet its goals, it is important to recognize some of its limitations. The results may not be as generalizable to other industries or regions because the data were collected exclusively from employees of food service establishments in Iligan City, Philippines. By using a more diverse sample that represents various industries and regions, future studies could increase external validity. Greater representation could lead to a better comprehension of the applicability of the GHRM–GHC–GEB framework in various cultural and organizational contexts. The study only employed a quantitative approach, relying on survey data evaluated using PLS-SEM. Using qualitative techniques, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, could improve comprehension of employees' experiences and opinions regarding GHRM practices, even though this method provided a clear statistical summary of the relationships between variables. These techniques may offer crucial contextual information about how GHC develops, is internalized, and is translated into behavior in organizational settings. Future studies may also examine the distinct effects of specific GHRM practices on the development of various GHC and GEB components. Dissecting these procedures could help identify the interventions that work best for encouraging environmentally conscious behavior and sustainable employee actions. The potential to improve strategic HR initiatives and promote more targeted, data-driven approaches for long-term human resource development is presented by this field of study.

6. Conclusions

In investigating the mediating role of GHC in the relationship between the GHRM practices and GEB, the study found that GHRM practices do not directly influence GEB. The direct path was weak and statistically insignificant. However, GHRM practices have a strong and significant indirect effect on GEB through GHC. This means that green human resource efforts are effective only when the organizations help employees develop the environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to act sustainably.

The results confirm that GHC fully mediates the relationship between GHRM and GEB. Employees are not likely to change their behavior just because green policies exist. The organizations need to understand, value, and feel capable of engaging in green practices and the role of GHC.

These insights have clear practical implications. Organizations should focus less on policy declarations and more on employee capability-building. Green recruitment and selection, green performance management and appraisal, green training and development, green empowerment, and green performance systems should be designed to strengthen GHC. Only then can human resource practices lead to real behavioral change in support of environmental sustainability.

Overall, GHRM practices shape employee behavior only through the development of the GHC. Therefore, building employees’ environmental knowledge, skills, and attitudes must be a core component of human resource strategies aimed at promoting organizational sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P., S.D., A.B., A.G., E.P., and F.V.; methodology, H.P., S.D., A.B., A.G., E.P., and F.V.; software, S.G.; validation, H.P., F.V. and E.P.; formal analysis, S.G., H.P., S.D., A.B. A.G. E.P., and F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.P. and V.P.; writing—review and editing, H.P. and V.P.; visualization, H.P., V.P, and S.G.; supervision, H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their heartfelt appreciation to Dr. Elnor C. Roa, Chancellor of Mindanao State University at Naawan, for her unwavering support, dedication, and motivating leadership, which significantly aided the successful realization of this research publication. Sincere gratitude is likewise extended to Dr. Rey Y. Capangpangan, Vice Chancellor for Research, Innovation, and Global Engagement, for his invaluable support, motivation, and dedication to promoting a research-oriented academic atmosphere. Their constant guidance and support have been crucial during the execution and finalization of this academic endeavor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GHRM |

Green human resource management |

| GHC |

Green human capital |

| GEB |

Green employee behavior |

| PLS-SEM |

Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

References

- Faisal, S. (2023). Green human resource management-a synthesis. Sustainability, 15(2259), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.M., Rauvola, R.S., Rudolph, C.W., & Zacher, H. (2022). Employee green behavior: A meta-analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 29(5), 1146-1157. [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Ren, S., Wang, M., Li, Y., & Zhang, S. (2023). Employee green behaviour: A review and recommendations for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev., 25(2), 297-317. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Chen, S. & Ruangkanjanases, A. (2021). Understanding the antecedents and consequences of green human capital. Sage Open, 11(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Meng, C., Shi, D., & Wang, B. (2023). The impact of green human capital of entrepreneur on enterprise green innovation: a study based on the theory of pro-environmental behavior. Finance Res. Lett., 58B, 104453. [CrossRef]

- Munawar, S., Yousaf, H.Q., Ahmed, M., & Rehman, S. (2022). Effects of green human resource management on green innovation through green human capital, environmental knowledge, and managerial environmental concern. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag., 52, 141-150. [CrossRef]

- Badwy, H.E., Qalati, S.A. & El-Bardan, M.F. (2025). Revolutionizing sustainable success: Unveiling the power of green human resource management, green innovation and green human capital. Benchmarking, ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.N., & Geetha, S.N. (2020). A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod., 247(119131). [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Chen, Y., Jiang, Y., Paille, P., & Jia, J. (2018). Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour., 56(1), 31–55. [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P., & Buonomo, I. (2020). Green human resource management: An evidence-based systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(5974), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Tanova, C., & Bayighomog, S.W. (2022). Green human resource management in service industries: the construct, antecedents, consequences, and outlook. Serv. Ind. J., 42(5-6), 412-452. [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z., Khan, I.U., Islam, T., Sheikh, Z. & Naeem, R.M. (2020). Do green HRM practices influence employees' environmental performance?. Int. J. Manpow., 41(7), 1061-1079. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Yu, H. & Xu, H. (2021). Effects of green human resource management and managerial environmental concern on green innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag., 24(3), 951-967. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J. Abid, N., Cucari, N., & Savastano, M. (2022). Green human resource management and environmental performance: The role of green innovation and environmental strategy in a developing country. Bus. Strateg. Environ., 32(4), 1782-1798. [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.M., Rauvola, R.S., Rudolph, C.W., & Zacher, H. (2023). Employee green behavior as the core of environmentally sustainable organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav., 10, 465-494. [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L., Davis, M.C., Russell, S.V., & Bretter, C. (2021). Employee green behaviour: How organizations can help the environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol., 42, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Norton, T. A., Zacher, H., Parker, S.L., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2017). Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav., 38(7), 996–1015. [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., Rudolph, C.W. & Katz, I.M. (2022). Employee Green Behavior as the Core of Environmentally Sustainable Organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav., 10, 465–494. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H., Zhang, J. & Li, J. (2020). The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 27, 7341–7352. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Yang, L., Cheng, X., & Chen, F. (2021). How Does Employee Green Behavior Impact Employee Well-Being? An Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18(4), 1669. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A., Jahan, S. & Riaz, M. (2021). Does green intellectual capital spur corporate environmental performance through green workforce?. J. Intellect. Cap., 22(5), 823-839. [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y. & Tang, L. (2021). The relationship among green human capital, green logistics practices, green competitiveness, social performance and financial performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag., 32(7), 1377-1398. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H., & Juo, W. (2021). An environmental policy of green intellectual capital: Green innovation strategy for performance sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ., 30(7), 3241-3254. [CrossRef]

- Ni, L., Ahmad, S.f., Alshammari, T.O., Liang, H., Alsanie, G., Irshad, M., Alyafi-AlZahri, R.A., BinSaeed, R.H., Al-Abyadh, M.H.A., Bakir, S.M.M.A., & Ayassrah, A.Y.A. (2023). The role of environmental regulation and green human capital towards sustainable development: The mediating role of green innovation and industry upgradation. J. Clean. Prod., 42, 138497. [CrossRef]

- Soto, G.H. (2024). The role of high human capital and green economies in environmental sustainability in the Asia-Pacific region, 1990–2022. Manag. Environ. Qual., 35(8), 1929-1952. [CrossRef]

- Alkaf, A., Yusliza, M., Ehido, A., Saputra, J., & Muhammad, Z. (2023). Top management support, green intellectual capital and green hrm: a proposed framework for sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. Tour., 14(5), 2308-2318. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Wang, G., Sun, C., Majeed, M.T., & Andlib, Z. (2023). An analysis of the effects of human capital on green growth: Effects and transmission channels. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 30(8), 10149-10156. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., & Go, S. (2020). Human capital and environmental sustainability. Sustainability, 12(4736), 1-14. https://doi:10.3390/su12114736.

- Jacobs, S. (2011). Human capital and sustainability. Sustainability, 3, 97-154. https://doi:10.3390/su3010097.

- Beisembina, A., Gizzatova, A., Kunyazov, Y., Ernazarov, T., Mashrapov, N., & Dontsov, S. (2023). Investing in human capital for green and sustainable development. J. Environ. Manag. Tour., 14(5), 2300-2307. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. (2019). Green human resource management and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 27(2), 630-1641. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.Y., Farrukh, M., & Raza, A. (2020). Green human resource management and employees pro-environmental behaviours: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 28(1), 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, U., Joseph, M. S., & Parayitam, S. (2023). Green human resource management practices and employee green behavior. J. Environ. Plan. Manag., 67(12), 2810–2836. [CrossRef]

- Yadate, D.A., (2025). The effect of green human resource management on employee green behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 32(1), 404–418. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., & Kaur, S. (2024). A 2-1-1 multi-level perspective of understanding the relationship between green human resource management practices, green psychological climate, and green employee behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 31(5), 4068–4084. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Ren, S., Tang, G., Ji, H., Cooke, F.L., & Wang, Z. (2023). How green human resource management affects employee voluntary workplace green behaviour: An integrated model. Hum. Resour. Manag. J., 34(1), 91–121. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J., Zhang, X., Zhou, L., Wang, D. & Tian, F. (2022). Psychological mechanism linking green human resource management to green behavior. Int. J. Manpow., 43(3), 844-861. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Zhang, W., & Daim, T.U. (2022). The voluntary green behavior in green technology innovation: The dual effects of green human resource management system and leader green traits. J. Bus. Res., 165, 114049. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N. (2022). Is green leadership associated with employees’ green behavior? Role of green human resource management. J. Environ. Plan. Manag., 66(9), 1962–1982. [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, A., Natalisa, D., Poór, J., Perizade, B., & Szabó, K. (2022). Predicting the relationship between green transformational leadership, green human resource management practices, and employees’ green behavior. Adm. Sci., 13(5), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J., Mamun, A.A., Masukujjaman, M., Makhbul, Z.K.M., & Ali, K.A.M. (2023). Modeling the workplace pro-environmental behavior through green human resource management and organizational culture: Evidence from an emerging economy. Heliyon, 9(e19134). [CrossRef]

- Mehrajunnisa, M., Jabeen, F., Faisal, M. N., & Lange, T. (2022). The influence of green human resource management practices and employee green behavior on business performance in sustainability-focused organizations. J. Environ. Plan. Manag., 66(12), 2603–2622. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Lou, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhao, J. (2022). How green human resource management can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability, 11, 5408. https://doi:10.3390/su11195408.

- Yong, J.Y., Yusliza, M.Y., Ramayah, T., Farooq, K. & Tanveer, M.I. (2023). Accentuating the interconnection between green intellectual capital, green human resource management and sustainability. Benchmarking, 30(8), 2783-2808. [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y., Cao, Y, Mughal, Y.H., Kundi, G.M., Mughal, M.H., & Ramayah, T. (2020). Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability, 12, 3228. https://doi:10.3390/su12083228.

- Shoaib, M., Abbas, Z., Yousaf, M., Zámečník, R., Ahmed, J., & Saqib, S. (2021). The role of GHRM practices towards organizational commitment: A mediation analysis of green human capital. Cogent Bus. Manag., 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Ercantan, O., & Eyupoglu, S. (2022). How do green human resource management practices encourage employees to engage in green behavior? Perceptions of university students as prospective employees. Sustainability, 14(1718), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. (2022). Promoting employee green behavior in the Chinese and Vietnamese hospitality contexts: The roles of green human resource management practices and responsible leadership. Int. J. Hosp. Manag., 105, 103253. [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O., Yusliza, M.Y., Wan Kasim, W.Z., Mohamad, Z., & Halim, M.A.S.A. (2020). Exploring the interplay of green human resource management, employee green behavior, and personal moral norms. SAGE Open, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, U., Joseph, M.S., & Mittal, A. (2023). Green human resource management and employee green behaviour: Participation and involvement, and training and development as moderators. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag., 11(2), 227-309. [CrossRef]

- Albloush, A., Alharafsheh, M., Hanandeh, R., Albawwat, A., & Shareah, A. (2022). Human capital as a mediating factor in the effects of green human resource management practices on organizational performance. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan., 17(3), 981-990. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B. B., Afsar, B., Hafeez, S., Khan, I., Tahir, M., & Afridi, M. A. (2019). Promoting employee's proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 26(2), 424-438. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. (2008). The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. J. Bus. Ethics, 77, 271–286. [CrossRef]

- Huo, X., Azhar, A., Rehman, N., & Majeed, N. (2022). The role of green human resource management practices in driving green performance in the context of manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability, 14(24), 16776. [CrossRef]

- Cassel, C., Hackl, P., & Westlund, A. H. (1999). Robustness of partial least-squares method for estimating latent variable quality structures. J. Appl. Stat., 26(4), 435-446. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Binz Astrachan, C., Moisescu, O. I., Radomir, L., Sarstedt, M., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy, 12(3), 100392. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).