1. Introduction

Tokenization, the process of segmenting raw text into fundamental units, is a critical initial step in any Natural Language Processing (NLP) pipeline. The chosen strategy directly dictates how linguistic information is structured for a model, thereby influencing its performance, robustness, and computational demands. While subword-based tokenizers like WordPiece [

1] and Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) [

2] are standard for high-resource languages, their efficacy for morphologically complex, low-resource languages such as Sinhala remains underexplored.

This research addresses this gap by investigating a central question: What is the optimal tokenization strategy for Sinhala NLP, considering the trade-off between model performance, robustness to textual noise, and computational efficiency?

To answer this, we conduct a comparative analysis of five distinct tokenization methods: Byte-level, Character-level, Grapheme Cluster, WordPiece (subword), and Word-level. We evaluate these by training Transformer-based classification models from scratch on four datasets designed to mirror real-world conditions: a clean dataset from social media, and three variants synthetically generated to include typographical errors and code-mixing (the use of Romanized "Singlish").

Although pre-training large language models (e.g., BERT [

3]) from scratch for each tokenizer would be ideal, the prohibitive computational cost necessitates a more focused approach. This study therefore provides a rigorous evaluation of tokenizer effectiveness within a controlled experimental framework, offering a vital baseline for researchers and practitioners building robust NLP systems for the Sinhala language.

2. Methodology

The core of our methodology involves a systematic comparison of five distinct tokenization strategies in the four different Sinhala NLP corpus. This results in a total of 20 experimental setups (), allowing for a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between tokenization and task performance.

2.1. Tokenization Strategies

We evaluate five tokenization methods, ranging from simple character splits to complex subword segmentation.

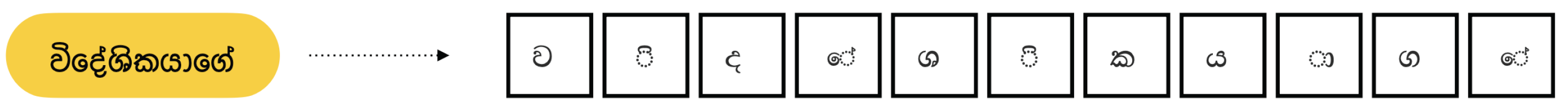

2.1.1. Character-Level Tokenization

This is the most granular tokenization method, where the input text is decomposed into individual characters. While this approach creates a small, fixed vocabulary and avoids any out-of-vocabulary (OOV) issues, it disassembles semantically meaningful units (like words or morphemes) into components that lack intrinsic context.

Figure 1.

An example of Character-Level Tokenization in Sinhala.

Figure 1.

An example of Character-Level Tokenization in Sinhala.

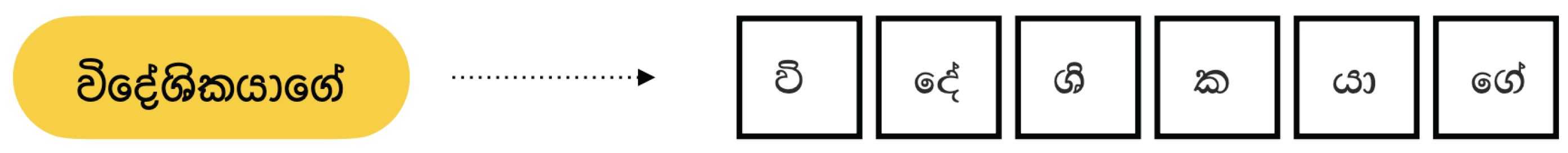

2.1.2. Grapheme Cluster Tokenization

Unlike simple character splitting, Grapheme Cluster Tokenization splits text into visually and linguistically cohesive units. In Sinhala, a single perceived "letter" is often composed of a base consonant and one or more diacritics (vowel signs, or "pili"). This tokenizer correctly groups these components into a single token, which preserves more semantic meaning than an individual character.

Figure 2.

An example of Grapheme Cluster Tokenization, which correctly groups base consonants with their diacritics.

Figure 2.

An example of Grapheme Cluster Tokenization, which correctly groups base consonants with their diacritics.

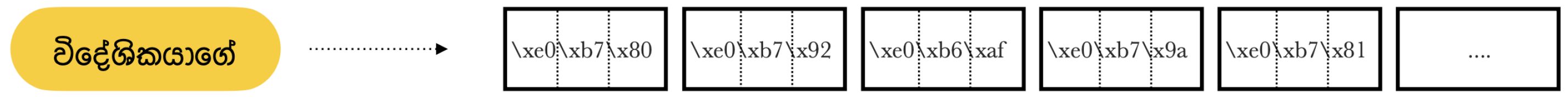

2.1.3. Byte-Level Tokenization

This method tokenizes text at the raw byte level based on its UTF-8 encoding. As Sinhala characters are typically represented by 3 bytes, this results in significantly longer token sequences. The primary advantage is the ability to model any text without encountering OOV tokens. The trade-off is that it creates long sequences and splits fundamental grapheme clusters into meaningless byte tokens, posing a challenge for the model.

Figure 3.

An example of Byte-Level Tokenization, showing how a single grapheme is split into multiple byte tokens.

Figure 3.

An example of Byte-Level Tokenization, showing how a single grapheme is split into multiple byte tokens.

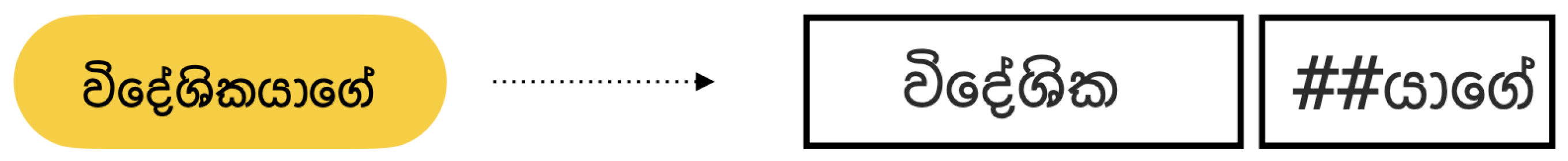

2.1.4. Subword-Based Tokenization (WordPiece)

Subword tokenization is the de facto standard in modern NLP. We use the

WordPiece algorithm, notably employed by BERT [

3]. WordPiece starts with a vocabulary of individual characters and iteratively merges frequent pairs of subword units to maximize the likelihood of the training corpus. This method strikes a balance between character- and word-level approaches, keeping common words intact while breaking rare words into meaningful subword units, effectively handling morphology and reducing the OOV problem.

Figure 4.

An example of WordPiece subword tokenization.

Figure 4.

An example of WordPiece subword tokenization.

2.1.5. Word-Based Tokenization

We also evaluate a traditional word-based tokenizer that splits text based on spaces and punctuation. While this method produces the shortest token sequences, it suffers from the out-of-vocabulary (OOV) problem, where any word not seen during training is mapped to a single "unknown" token. This is particularly problematic for morphologically rich languages like Sinhala. Nevertheless, it is included in our analysis to provide a comprehensive baseline.

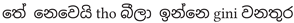

3. Model Architecture

The classification model used for all experiments is based on the Transformer encoder architecture introduced by Vaswani et al. [

4]. As depicted in

Figure 5, our classification model comprises three main components: an embedding layer, a stack of Transformer encoder blocks, and a final classification head.

First, the input sequence of token IDs is converted into dense vector representations by the Token Embedding layer. To provide the model with information about the order of the tokens, these embeddings are added element-wise with Positional Embeddings. The resulting combined embeddings are passed through a stack of N identical Transformer Blocks. Each block contains two primary sub-layers: a Multi-Head Self-Attention mechanism and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN). A residual connection followed by layer normalization is applied after each sub-layer.

Finally, for classification, the output representation of the first token in the sequence (i.e., the `[CLS]` token) from the final encoder block is used as an aggregate representation for the entire sequence. This vector is passed through a linear layer followed by a softmax function to produce a probability distribution over the target classes.

4. Experiment Setup

4.1. Datasets and Data Augmentation

To assess tokenizer effectiveness for a low-resource language in a manner that reflects real-world use cases, we used the original SOLD [

5] dataset as a baseline and created three synthetic variants. Real-world text data often contains typographical errors and code-mixing. Therefore, our data augmentation process was designed to simulate these practical concerns by generating the following datasets:

Minor Typos: Each character in the original text has a 5% probability of being randomly deleted, replaced, or swapped with an adjacent character.

Aggressive Typos: The character-level error probability is increased to 10%.

Code-Mixing and Typos: This variant combines minor typos (5% character error rate) with code-mixing, where each word has a 30% probability of being transcribed into its romanized form ("Singlish").

An example of the data augmentation is shown below:

Original:

Aggressive Typos:

Code-Mixing:

4.2. Model Training and Hyperparameters

For each of the 20 experiments, we train the Transformer-based classification model from scratch. While the vocabulary size varies with the tokenizer, the core architecture hyperparameters are kept constant to ensure a fair comparison. All models are trained using the AdamW optimizer. Model performance is evaluated using the macro F1-score, which is suitable for potentially imbalanced datasets. The key hyperparameters are detailed in

Table 1.

5. Results and Discussion

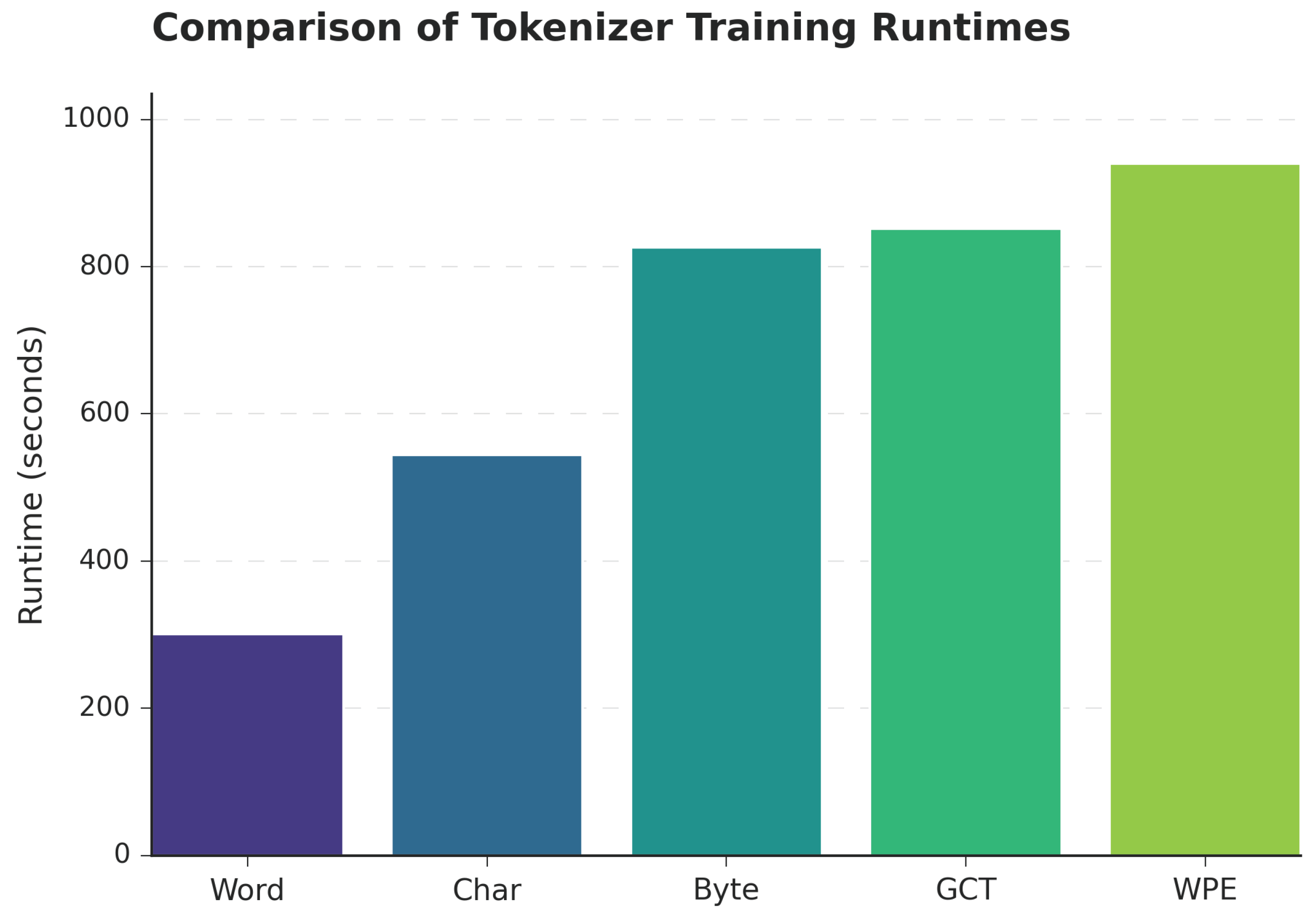

This section analyzes our empirical findings, focusing on the trade-offs between performance, robustness across different data conditions, and computational cost.

Discussion

Our results reveal a clear and critical trade-off between performance, robustness, and computational efficiency. We discuss these findings and their practical implications below.

The Efficiency-Robustness Trade-Off

Figure 6 starkly illustrates the computational cost of robustness. There is an inverse relationship between representational granularity and training speed. The Word-level tokenizer is the fastest by a significant margin, making it attractive for rapid prototyping. The most robust methods, WPE and Byte-level, are the slowest due to the much longer token sequences they produce, which increases the computational load on the Transformer architecture.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of five tokenization methods for Sinhala NLP, evaluating the trade-offs between performance, robustness, and efficiency.

The Word-level tokenizer is fastest and best on clean text but is too brittle for noisy, real-world data. Conversely, WordPiece (WPE) emerges as the most effective all-around strategy, offering the best robustness against textual corruption, making it the premier choice for production systems despite its high computational cost. For applications where this cost is prohibitive, the Grapheme Cluster (GCT) tokenizer presents an excellent, balanced alternative.

Future work should extend this analysis by pre-training large language models from scratch for each tokenization strategy to explore their full potential. Nonetheless, this study provides a crucial empirical foundation for making informed, scenario-aware decisions when developing NLP systems for Sinhala and other morphologically rich, low-resource languages.

References

- Wu, Y.; Schuster, M.; Chen, Z.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; et al. Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.08144. [Google Scholar]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.07909. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, pages 5998–6008, 2017.

- Ranasinghe, T.; Anuradha, I.; Premasiri, D.; et al. SOLD: Sinhala offensive language dataset. Lang Resources & Evaluation 2025, 59, 297–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).