1. Introduction

Proprioception, the sense of body position and movement in space, is essential for postural control, joint stability, and the coordination of complex movements, though it typically operates outside of conscious awareness [

1,

2,

3]. This system relies on sensory feedback from mechanoreceptors in muscles, tendons, and joints, which provide the brain with information about the body’s spatial position [

4]. Proprioception is critical for maintaining balance and performing everyday tasks, allowing individuals to adjust their movements based on body segment positions in relation to their surroundings [

5,

6]. When proprioception is impaired, maintaining stable posture and executing movements accurately becomes difficult. Such impairment is frequently observed in musculoskeletal disorders, affecting various regions from the cervical spine to the ankle [

7].

For women undergoing the menopausal transition, proprioception is particularly vulnerable due to both the natural aging process and menopause-specific changes [

8]. Aging reduces muscle mass, bone density, and joint function, which directly contribute to proprioceptive decline [

9,

10]. This manifests as reduced balance confidence, joint stiffness, and diminished mobility, all of which can negatively impact daily functioning [

11,

12]. In addition, the decline in estrogen during menopause further exacerbates these issues, leading to an increase in intra-abdominal fat and other body composition changes, impairing balance and functional mobility [

13,

14]. As a result, women in the menopausal transition are at an increased risk of falls and fractures, with this risk escalating with age, as proprioception is key in maintaining postural control and balance [

15,

16].

While many proprioception assessments exist, most are conducted in clinical or laboratory settings using specialized equipment [

1,

17,

18,

19]. Additionally, many of these assessments are designed for individuals with neurological injuries or conditions, such as stroke patients, who often undergo robotic-assisted testing [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Although accurate, these methods are not feasible for home use, especially for midlife women who lack access to specialized equipment.

Physical exercise has been shown to significantly mitigate these risks. Exercises targeting proprioception and balance, such as Pilates, Tai Chi, Qigong, and 3D movement methods, have proven effective in improving postural stability, enhancing balance, and increasing functional mobility, all of which are vital for reducing fall risk in postmenopausal women [

11,

13,

25,

26,

27].

Despite the benefits of physical exercise, many midlife women face time and resource constraints that make it difficult to engage in regular, structured exercise programs. The demands of family, professional, and personal responsibilities limit their ability to attend in-person classes or commit to long-term physical activity regimens [

28,

29,

30]. To overcome these barriers, many women turn to remote exercise programs, including online and blended options, which gained popularity during the lockdown and after COVID-19 pandemic [

31,

32].

However, few studies have explored how women in the menopausal transition engage with remote or hybrid movement programs, particularly those that require self-monitoring in the absence of live supervision. The challenges of maintaining proprioceptive health, body awareness, and motor control during this life stage remain insufficiently addressed, especially through low-tech, accessible formats.

To respond to this gap, the MAS protocol was developed as a flexible, self-guided system for proprioceptive screening and movement-based assessment. Designed for home or hybrid use, the protocol includes functional tests, reflective tools, and a structured movement practice grounded in the Zarina del Mar 3D Method. It is primarily intended for use with a smartphone, allowing participants to record and review their movements as part of the self-assessment process. For users with limited technological access or low digital literacy, the protocol also offers a simplified version using a mirror and printed guides.

The approach is informed by body schema theory [

33,

34,

35], which refers to the unconscious sensorimotor representation of the body that supports posture and movement control. In contrast to the more static concept of body image, the body schema is continuously updated through proprioceptive, vestibular, and visual input. A decline in proprioceptive accuracy, which is often observed during the menopausal transition, can disrupt this internal model and lead to postural instability and movement inaccuracy. The MAS protocol is designed to support the refinement of the body schema through self-assessment, structured movement practice, and reflective sensory engagement.

The current study presents a first-phase evaluation of the MAS protocol using a single-case design focused on Participant L, a midlife woman with prior experience in the 3D method. It examines the feasibility and interpretive depth of the protocol’s multi-modal components, including self-assessment, movement practice, and expert review.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a single-case design, selected for its ecological validity and ability to detect meaningful individual change in applied movement contexts [

36]. Widely used in sports and rehabilitation research, this approach enables in-depth tracking of personalized outcomes over time. Unlike group-based designs focused on statistical averages, single-case studies support contextualized observation of functional change and embodied experience.

2.1. Participant

Participant L, a 48-year-old woman with prior experience in the Zarina del Mar 3D movement method, was selected through voluntary recruitment. Familiarity with the 3D method was required to ensure accurate engagement with the intervention. Prior to the study, she submitted a sample performance video to support the development of a tailored practice sequence. She met all inclusion criteria and provided informed consent. Selection criteria excluded individuals with neurological or psychiatric diagnoses, central nervous system-affecting medications, or professional athletic backgrounds. Detailed demographic and fitness characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

2.2. MAS protocol for home-based proprioceptive training and evaluation

The MAS (Movement, Awareness, Sensation) protocol is a structured system for self-assessment and proprioceptive training developed by the author. It integrates guided movement practice, functional testing, and reflective tools into a unified framework aimed at enhancing bodily awareness and internal perception. Designed for flexible use in home-based or hybrid settings, the protocol can be implemented as a fully low-tech model using pen, paper, and a smartphone for optional video recording and playback. For practitioners in regions with limited technological infrastructure, or for participants who are not comfortable using smartphones, the protocol can be performed using a printed guide, self-observation in a mirror, and manual scoring or drawing. In contrast, those familiar with mobile devices may use a fully remote version involving digital forms, video-based self-analysis, and app-supported mapping. This dual structure ensures accessibility while allowing for future technological development, including app or AI-based formats.

2.3. 3D movement intervention as core component of MAS

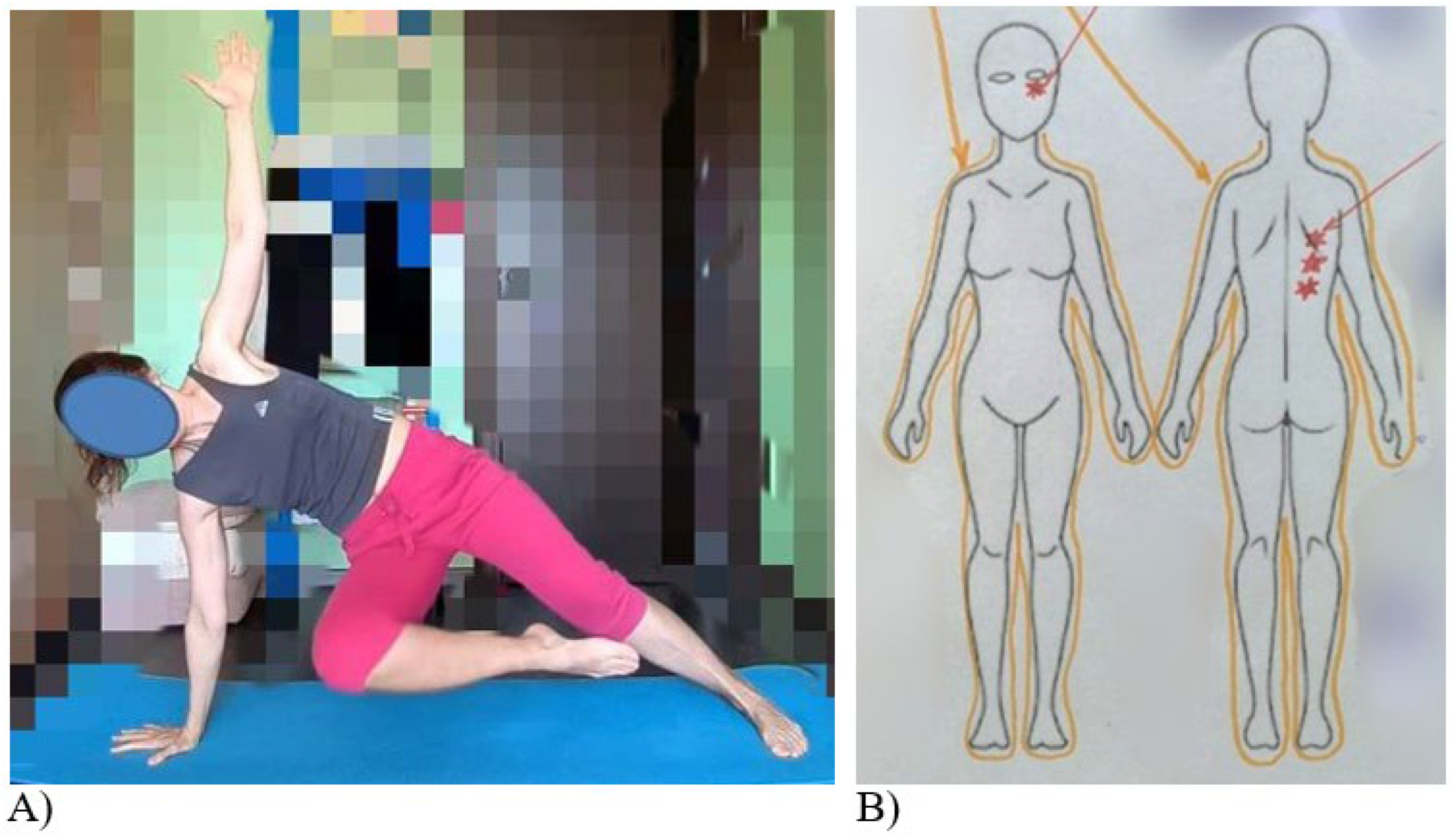

The movement component of the protocol is built around the Zarina del Mar 3D Movement Method, a somatic training system emphasizing biomechanical alignment, sensory-motor integration, and attentional engagement. This method has been applied across diverse female populations and was tailored in this study to the specific physical profile of participant L.

Following baseline assessment, a four-minute personalized sequence was developed incorporating four foundational exercises - side plank, shrimp squat, push-up, and mermaid stretch. These were performed either as a continuous flow or in isolated segments, depending on comfort and ability. The method promotes proprioceptive awareness through spatially varied, internally guided movement that emphasizes amplitude, precision, and postural control.

2.4. Functional test batteries for pre- and post-assessment

To evaluate changes in proprioception and sensorimotor coordination, two original test batteries were developed and implemented within the MAS protocol: the Proprioceptive and Postural Readiness Battery (PPRB) and the Sensorimotor Coordination and Balance Battery (SCBB).

While the individual tasks within these batteries were created for this study, their structure and objectives are grounded in research traditions from rehabilitation and sports science that use functional movement tests to assess alignment, mobility, and coordination in female populations of various age ranges [

12,

37,

38].

2.5. Proprioceptive and Postural Readiness Battery (PPRB)

The PPRB consists of five tasks: posture analysis, roll-down and roll-up, spinal twist, Z-set (left and right), and overhead squat. These tasks are designed to evaluate alignment, segmental control, and cognitive-motor coordination. Each task was scored by Participant L using a 10-point scale ranging from severe deficits to optimal execution. Task-specific reflection prompts, formulated in accessible language and reviewed by two physical education experts, supported her self-evaluation.

Posture analysis focused on craniocervical alignment, scapular symmetry, and spinal curvature. The roll-down and roll-up sequence assessed spinal articulation and pelvic stability. The spinal twist tested rotational mobility and smoothness, while the Z-set examined hip mobility and pelvic control. The overhead squat served as a compound movement to evaluate full-body coordination in a functional context. To supplement these assessments, Participant L captured video screenshots and used schematic mapping techniques adapted from Kim et al. [

39] to annotate joint positions and alignment, enhancing spatial awareness through visual self-analysis. This approach aligns with findings emphasizing proprioceptive feedback and segmental awareness in complex motor regulation [

40].

2.6. Sensorimotor Coordination and Balance Battery (SCBB)

The SCBB included eight tasks targeting balance and coordination in both static and dynamic conditions: Romberg position, single-leg stance, shoulder and elbow rotation, hip abduction, straight-leg hip rotation, stomping, and clapping. The same self-assessment strategy applied in the PPRB was used, including 10-point task ratings and structured reflection questions.

Romberg testing was employed to isolate visual and proprioceptive contributions to postural control [

41,

42], while single-leg balance tasks examined lower-limb stability despite their known limitations in detecting proprioceptive deficits at specific joints such as the knee [

43]. Rotational and dynamic elements reflected established protocols for evaluating joint position sense and neuromuscular integration in applied contexts.

Together, the PPRB and SCBB provided a multi-faceted view of Participant L’s proprioceptive status, allowing for detailed analysis of postural strategy, balance control, symmetry, and body awareness through low-tech, user-led tools embedded within the MAS protocol.

2.7. Somatic screening component

The somatic screening segment of the MAS protocol was designed to explore internal bodily perception through guided introspection. Drawing from the principles of the Feldenkrais Method [

44], it emphasized subtle movement, spatial orientation, and asymmetry as tools for enhancing proprioceptive awareness. Participant L completed the screening twice, once before and once after the 3D movement intervention, allowing for comparative analysis of changes in somatic perception.

Each session involved two stages. First, Participant L performed a slow, eyes-closed body scan, progressing from head to feet while initiating small, exploratory movements. She recorded real-time verbal reflections describing areas of ease, restriction, or imbalance. This was followed by a written account using open-ended prompts from the MAS protocol. She was encouraged to elaborate using imagery, metaphor, or emotion to provide deeper access to embodied experience.

This form of self-observation aligns with evidence linking somatic awareness to improved motor coordination, learning, and self-regulation [

45]. Somatic methods have also been shown to deepen attentional engagement and support embodied agency with potential applications in creativity and self-efficacy [

46]. Within this protocol, the somatic screening added a qualitative dimension to proprioceptive evaluation, capturing shifts in internal bodily presence alongside observable performance.

2.8. Body Mapping Component

Body mapping was the final element of the MAS protocol, designed to capture changes in proprioceptive and interoceptive awareness through symbolic visual representation. It enabled Participant L to externalize her internal sensations, spatial orientation, and postural perception as they evolved across the intervention.

Participant L was instructed to complete one body map per day during the seven-day movement practice. However, she produced additional maps when shifts in sensation were noted, often drawing two or three maps per day to reflect states before, during, and after practice. Visual templates of front and back body outlines were provided, though she was free to modify these or draw her own. A basic set of symbolic colors was offered to represent sensations such as tension, stiffness, pain, warmth, and relaxation. She was also encouraged to develop personal annotation systems and to add written descriptions when drawing alone did not fully convey the experience.

The maps functioned as qualitative self-assessment tools, helping her localize and express proprioceptive states related to alignment, movement amplitude, and structural coherence. By comparing sequences of maps, it was possible to track how proprioceptive organization shifted in relation to movement practice. An interpretive rubric was applied to assess visual completeness, anatomical consistency, and expressive detail, in line with previous somatic mapping approaches.

This application draws from embodied research traditions. Cochrane et al. [

47] highlighted body maps as effective for visualizing somatic states in design contexts, while Crivelli et al. [

45] noted their relevance for motor learning and embodied regulation. Similar uses have been documented in therapeutic and participatory research, where mapping supports reflection on shifting bodily experience [

48]. Within the MAS protocol, body mapping provided a structured yet expressive way to link movement practice with perceptual change.

2.9. Participant Evaluation and Expert Review Procedures

To assess the effectiveness and interpretability of the MAS protocol, a multi-layered evaluation strategy was implemented, incorporating self-assessment, expert review, and reflective participant feedback. The process began with a short feedback questionnaire completed by Participant L immediately after the post-test phase. This questionnaire included open-ended items on the clarity, usefulness, and personal relevance of the MAS protocol components, such as the functional tests, body mapping, and somatic screening. However, the responses were brief and insufficient for in-depth analysis.

To address this, a follow-up reflective interview was conducted via Zoom on Day 17, approximately one week after completion of the MAS cycle. The semi-structured interview lasted 80 minutes and explored the participant’s embodied experience with the protocol across three thematic dimensions: movement, awareness, and sensation. The interview guide is provided in the supplementary materials.

In parallel, two independent experts in physical education reviewed Participant L’s pre- and post-test recordings for the full set of motor tasks (PPRB and SCBB). They rated each task using a 10-point scale and submitted written evaluations focused on performance quality, alignment, and control. An additional movement analysis expert provided visual feedback based on screenshot annotations submitted by the participant.

Finally, a non-evaluative commentary was contributed by Zarina del Mar, the creator of the 3D Movement Method, which served as the central practice within the MAS protocol. Although she did not assess performance formally, she reviewed submitted videos of the daily movement sessions and offered interpretive notes on the participant’s adaptation of the method.

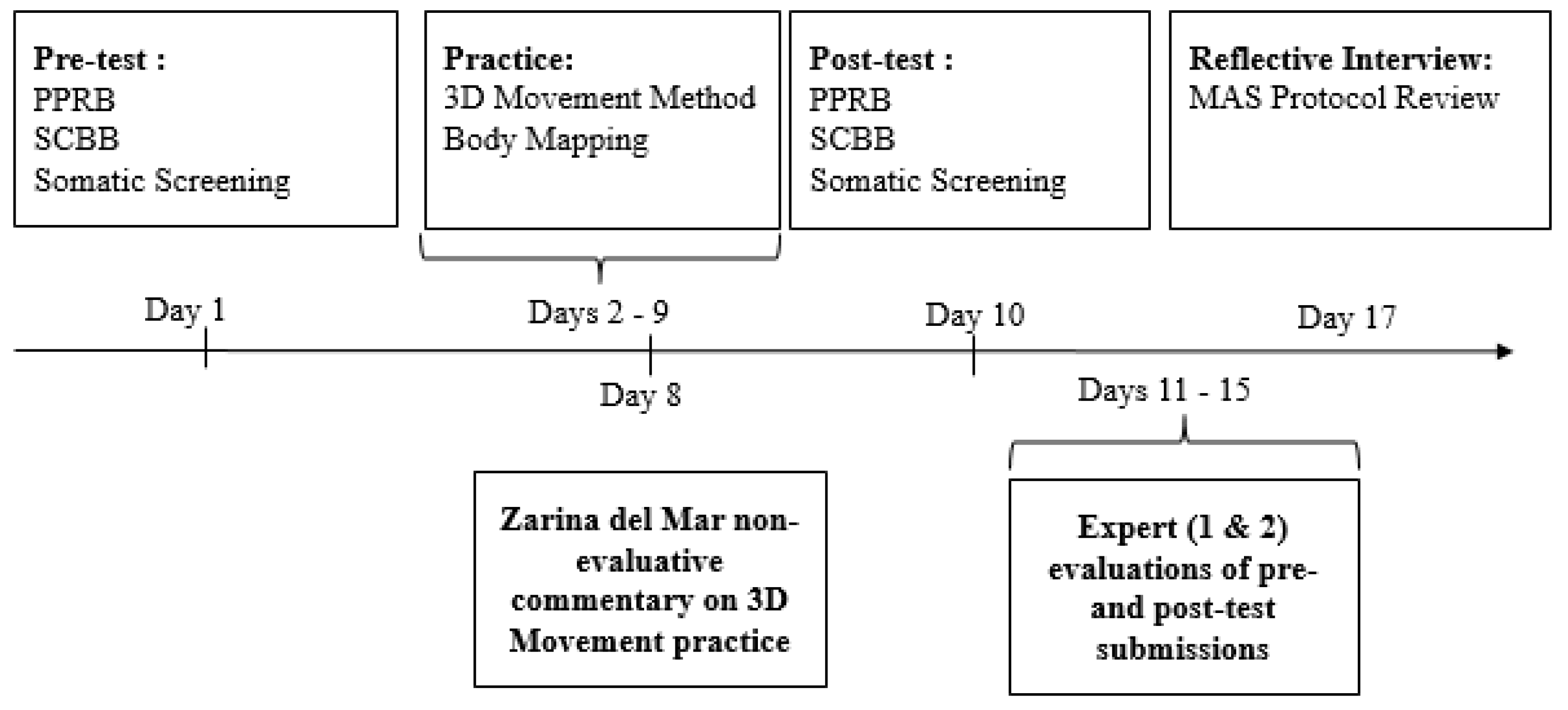

The full structure and timeline of the study, including all MAS protocol components, are presented in

Figure 1 below.

2.10. Data analysis

Data analysis integrated a triangulated, multi-method framework to evaluate proprioceptive development through the MAS protocol. Participant L's progression was examined across several qualitative and structured sources: self-evaluations, expert ratings, somatic screening outcomes, body maps, and interview transcripts. No quantitative metrics directly assessed practice performance.

A thematic analysis approach [

49] was applied to interview and written responses, focusing on emerging patterns in awareness, coordination, and embodied control. Reflexive journals and body map visuals were used to interpret changes in internal body schema and somatosensory perception.

To enhance analytical rigor, three triangulation methods were implemented. Data triangulation compared self-reports, video recordings, and expert feedback to identify convergence or dissonance in perception and evaluation. Methodological triangulation linked video analysis, somatic screening, and reflective feedback to ensure multidimensional insight into proprioceptive change. Researcher triangulation cross-referenced evaluations by multiple observers to reduce subjectivity and validate interpretive claims.

This integrative process allowed for a robust synthesis of data, providing a comprehensive picture of the participant’s proprioceptive trajectory within a self-guided assessment model.

2.11. Ethical Considerations

This study involved one adult participant engaged in a self-directed, non-invasive movement protocol. No clinical procedures, biomedical interventions, or sensitive health data were collected. Based on institutional and national guidelines for minimal-risk research with healthy adults, formal ethical approval was not required.

The study’s aims and procedures were explained verbally and in writing, and Participant L provided written informed consent. This covered all elements of the study, including recorded exercises, body maps, somatic screening, and reflective materials, with explicit permission for anonymized use in publications. Participant identity was protected throughout.

Although Participant L had previously trained in the Zarina del Mar 3D method, there was no direct contact with the trainer during the study. All materials were standardized to ensure consistency, and all data were submitted directly to the first author, who coordinated independent expert evaluation. All procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.12. Data Protection and Privacy

Data were securely stored and accessible only to the research team. To preserve anonymity, video recordings featured face blurring, plain attire, and concealed identifying features using gloves and socks. Videos were recorded against a neutral background, avoiding personal items or visible outdoor views. These measures ensured confidentiality and minimized identification risk.

3. Results

3.1. Functional Assessment Result

The 7-day 3D movement intervention produced measurable improvements in coordination, balance, and proprioceptive function in Participant L, as indicated by the combination of self-assessment, expert ratings, and visual analysis of test markups. Despite these improvements, noticeable discrepancies remained between the participant’s self-evaluations and expert assessments, especially in proprioception-focused tasks.

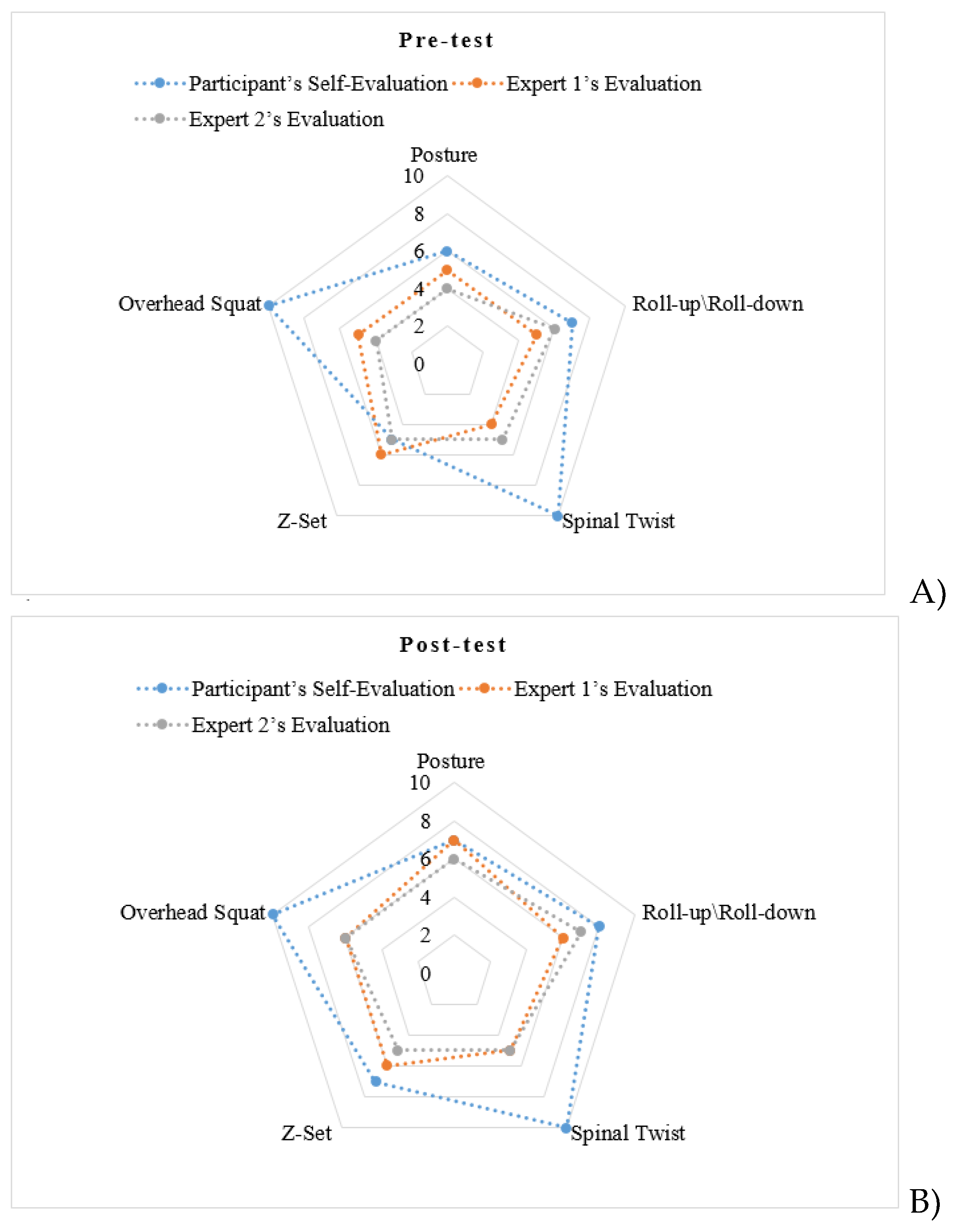

In the PPRB, pre-test results showed that Participant L consistently overestimated her performance relative to expert evaluations (

Figure 2A). In tasks such as the Spinal Twist and Overhead Squat, she rated herself 10/10, while Expert 1 and Expert 2 each gave scores of 4/10. In the Z-Set and Roll-up/Roll-down, her average rating was 8.5, compared to 6 (Expert 1) and 5 (Expert 2). Her overall mean score was 7.6 ± 2.1, while the experts' means were 5.0 ± 0.7 and 4.8 ± 0.8.

Post-test assessments (

Figure 2B) showed increases across both self and expert scores, though rating discrepancies persisted. For the Spinal Twist and Overhead Squat, Participant L reduced her rating to 9/10, while experts increased theirs to 6/10. For the Z-Set and Roll-up/Roll-down, her self-rating improved to 9/10, with corresponding expert scores of 7 (Expert 1) and 6 (Expert 2), suggesting both functional improvement and partial alignment in evaluation.

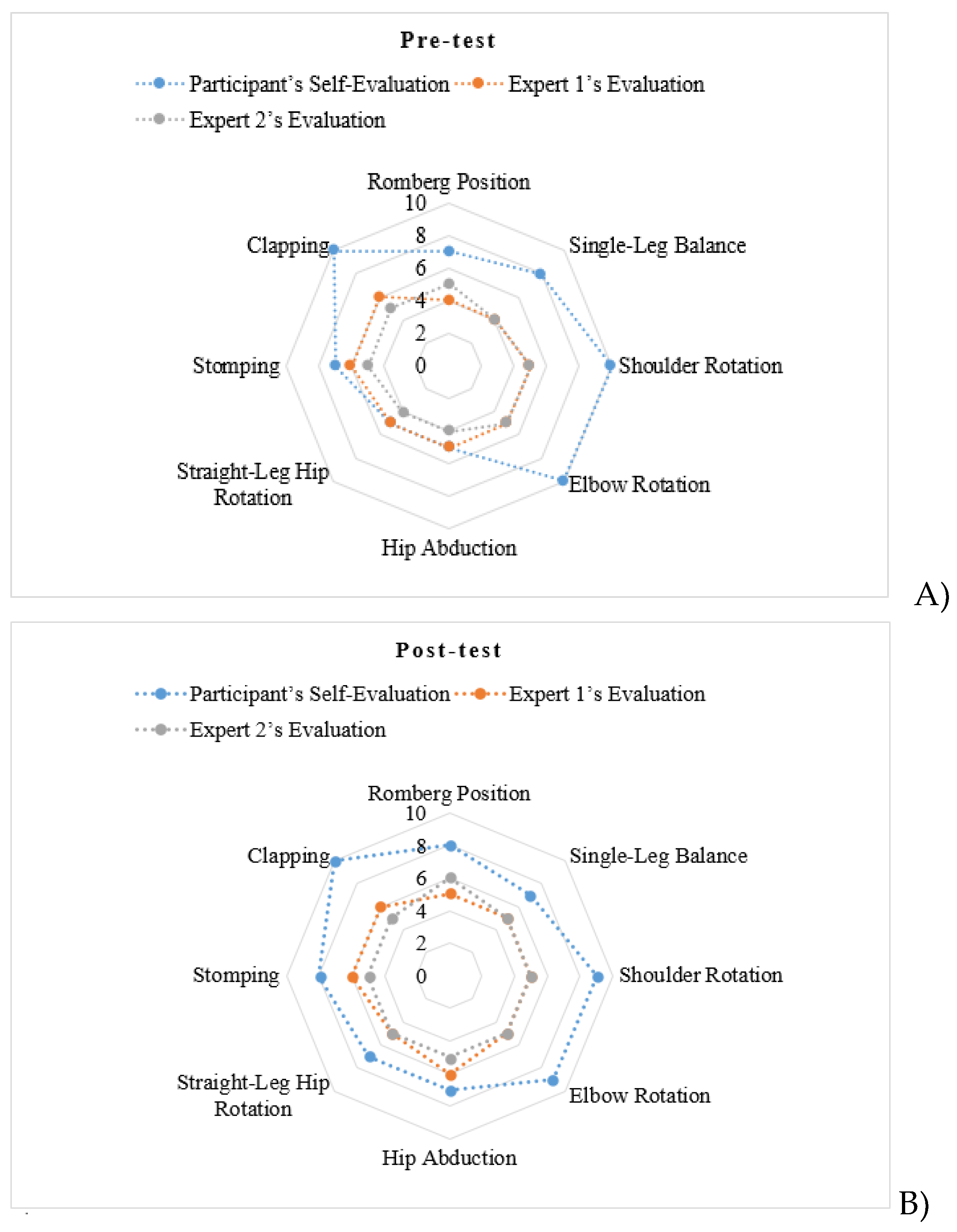

Similar trends were seen in the SCBB. In pre-test results (

Figure 3A), tasks like Single-Leg Balance and Clapping were notably overestimated by the participant. She rated these at 8/10 and 10/10 respectively, while experts gave scores of 4/10 for Single-Leg Balance and 6/10 and 5/10 for Clapping. The participant’s SCBB mean was 8.0 ± 1.3, versus 5.3 ± 0.9 and 5.0 ± 0.8 from Expert 1 and Expert 2.

Following the intervention, evaluations were more aligned (

Figure 3B). In Single-Leg Balance, the self-score dropped to 7, while experts remained at 5. In Clapping, the participant maintained 10, while experts’ scores rose slightly to 6 and 5, indicating both continued overestimation and functional gains.

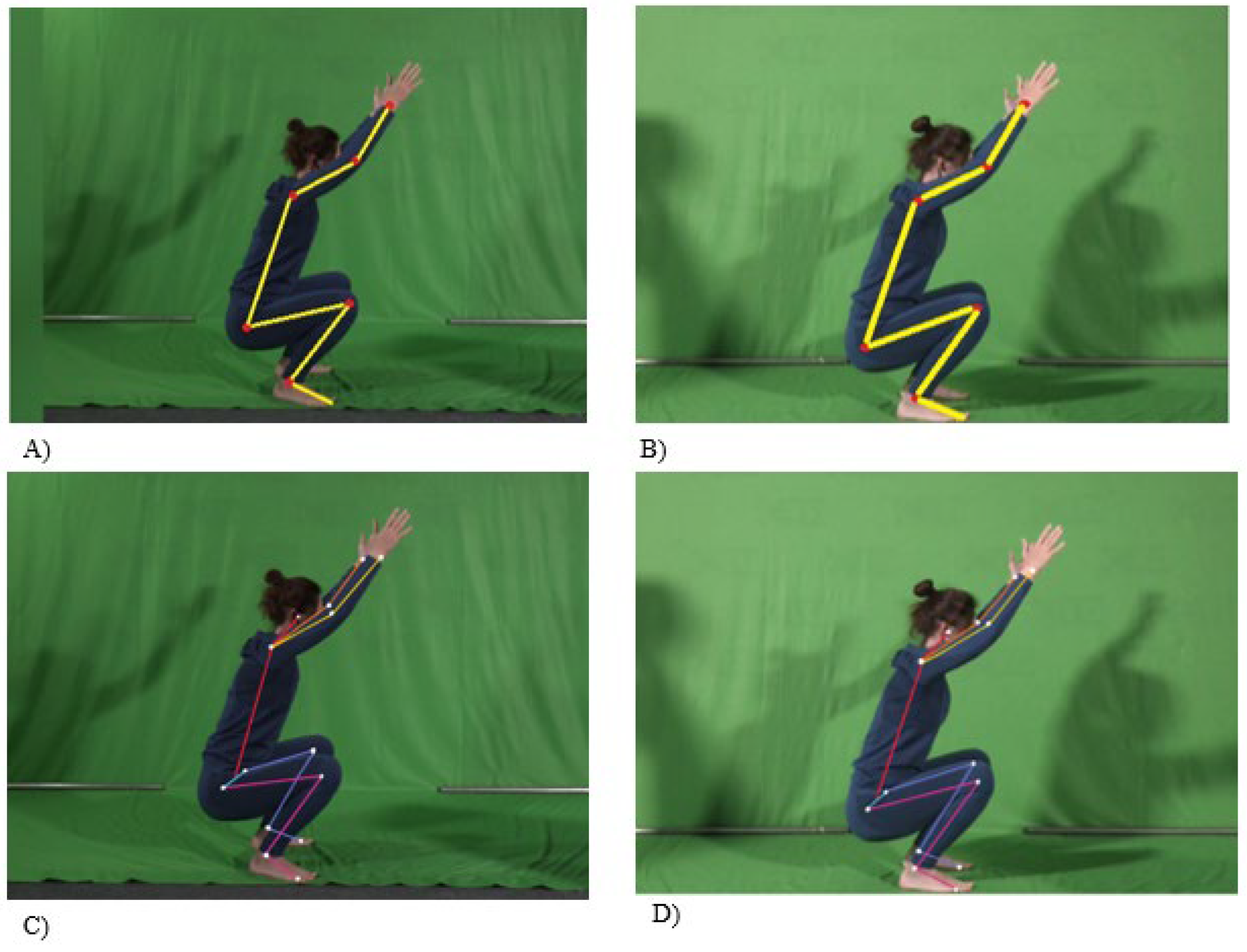

Further insight was obtained through analysis of annotated screenshots (

Figure 4). Experts noted that while Participant L accurately understood task instructions and marked joint positions correctly, the use of overly thick lines complicated the interpretation of minor improvements. Despite this, visual comparisons confirmed subtle but consistent changes in posture across test phases, validating expert evaluations. These findings suggest that while the participant could recognize improvements, her internal benchmark for ideal form may not yet be fully developed, contributing to persistent overestimation.

Overall, the intervention effectively enhanced proprioceptive skills and postural control, though self-assessment accuracy remained limited (will be further examined in the qualitative component of the study).

3.2. Somatic Awareness Screening

In both the pre- and post-intervention somatic screenings, Participant L offered concise observations primarily centered on physical alignment and symmetry, with minimal reference to affective or interoceptive dimensions. During the pre-test assessment, conducted in a supine position with eyes closed to enhance proprioceptive sensitivity, she reported an asymmetrical body posture, perceiving the left side of her body to be elevated relative to the right. This perception was not corroborated by external observation, as her daughter noted that the shoulders were level.

The participant described tension in the cervical region and tingling sensations localized in the middle and ring fingers. These descriptions may suggest mild proprioceptive misalignment or heightened sensitivity in distal extremities. However, the participant did not articulate any emotional associations or broader sensory narratives linked to these bodily sensations.

Post-test reflections remained consistent in focus, with continued emphasis on structural alignment. She again noted that her head contacted the ground at the transition between the crown and occipital region, mirroring her earlier description. She reported equal shoulder contact with the surface and an absence of neck tension, which may indicate localized neuromuscular relaxation or increased postural symmetry. Nonetheless, no new observations were offered regarding the emotional or affective significance of these changes. For movements involving the pelvis and lower limbs, she described the execution as smooth and unproblematic, yet offered no commentary on somatosensory richness or embodiment, suggesting that while proprioceptive function may have improved, interoceptive awareness remained limited.

This persistent absence of emotional or sensory reflection, despite improvements in physical alignment and comfort, is further considered in the thematic analysis.

3.3. Body Mapping

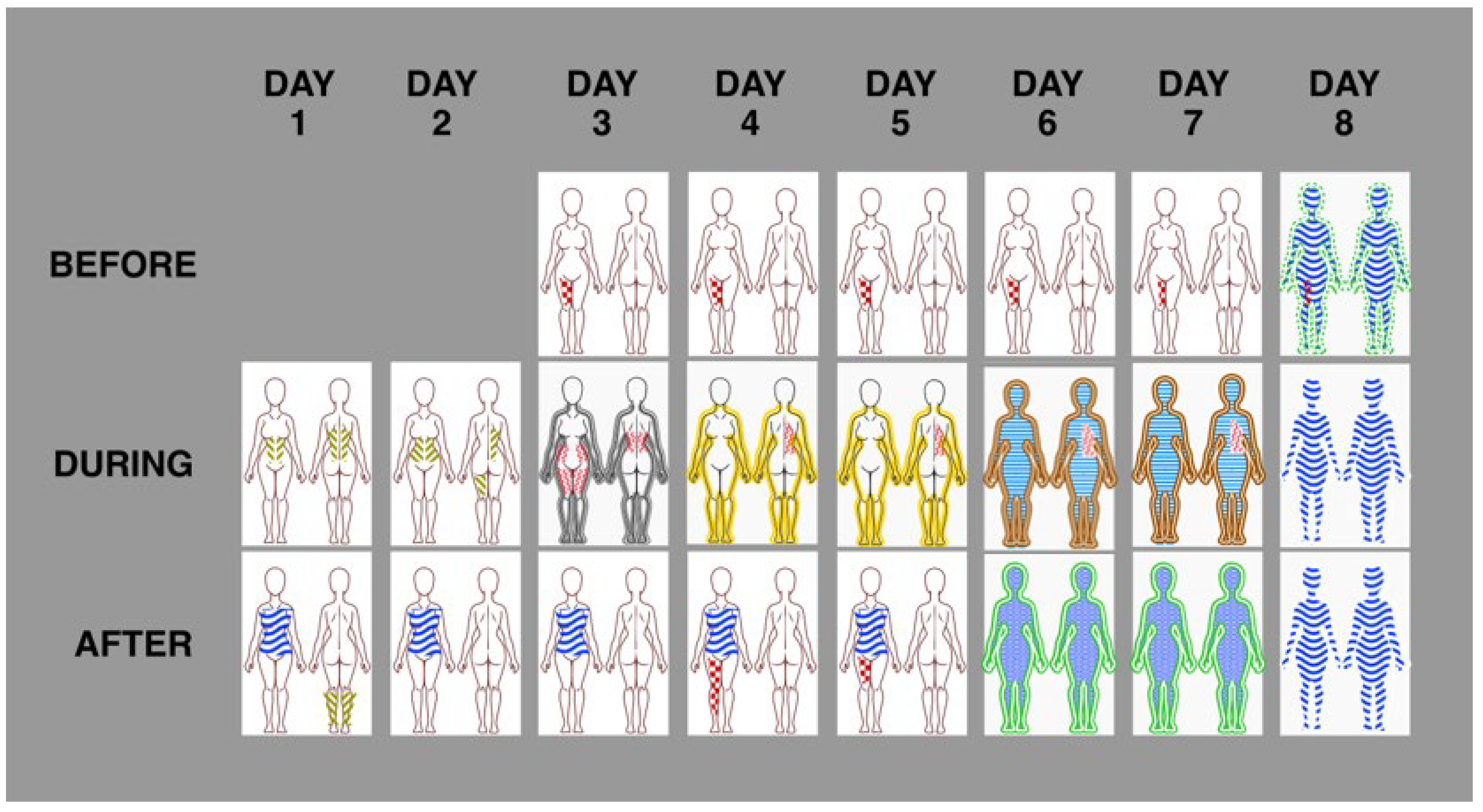

Participant L stated that she understood the instructions for body mapping but applied a format that combined aspects of mapping and journaling. Her descriptive comments often included information about time, mood, and contextual aspects of the practice. These entries were structured in tabular form and are included in the supplementary materials, along with the original hand-drawn maps. The adapted digital versions of the body maps are presented in the main text for clarity and analysis (

Figure 5).

While the protocol allowed for a variety of symbols to indicate bodily sensations, Participant L consistently limited her markings to three main areas: vibration or numbness in the leg, which appeared before the protocol and was attributed to overexertion during vacation; a sensation in the abdominal region during practice; and persistent discomfort under the right shoulder blade.

According to her own commentary and confirmed by expert observation, this last area reflected ongoing difficulty related to upper body weakness. The repeated focus on these specific regions suggests an increase in segmental proprioceptive awareness, particularly in zones subjected to habitual tension and mechanical loading. Comparison between the practice video and the body maps also demonstrated that the participant was able to detect sensitive or painful points in specific areas of the body, reflect them accurately in the body maps, and adjust her posture accordingly in the following session. This correspondence between felt sensation, mapped representation, and motor correction was observable in sequential entries and is illustrated in

Figure 6.

From the beginning of the intervention, Participant L frequently reported sensations of energy and vitality following the exercises. Initially these sensations were localized in the core, but by day 6 she described them as extending throughout the entire body. This shift was reflected in the adapted body maps, which began to display broader, more integrated contours. Her written reflections, including comments such as “Movements 1 and 2 were easy, but movements 3 and 4 felt challenging, likely due to late practice” and “Movement 1 felt easier with better coordination and smoother flow,” corresponded with these visual changes. Although the participant used only a limited set of marks and three recurring patterns involving the leg, torso and full body, the overall tendency showed a shift toward more unified bodily perception. This progression aligns with improved integration of the body schema, indicating a refinement in how proprioceptive inputs were internally organized and represented as a coherent whole.

On day 3, a general full-body sensation was noted for the first time. It was marked in grey and interpreted as a sign of overall fatigue resulting from intense practice. This gradually changed over the following days: on day 4, the same area was marked in brown, and by day 5 it appeared in yellow, which the participant associated with decreased physical difficulty and greater ease in movement. On day 7, all three maps presented a complete body outline including the head, which she described alongside experiences of sudden sleep onset and deep relaxation. These entries suggested a high level of post-practice physiological downregulation and a temporary state of perceived internal balance. The emergence of full-body marking and its evolving tonal expression indicates a growing coherence in whole-body proprioception, where the participant increasingly perceived spatial and postural alignment as unified rather than segmented.

On day 8, relaxation was no longer marked. Instead, the participant reported a feeling of energy and alertness involving the entire body, present not only after but also before the session. During the session itself, she again drew a full-body contour, now associated with a sense of harmony. However, she also noted psychological tension due to anticipated testing the following day. This contextual factor may explain the shift from a relaxed state to one of physiological readiness. The ability to detect and describe this internal shift points to an emerging link between interoceptive and proprioceptive processing. Specifically, the participant appeared increasingly capable of registering emotional and autonomic changes in bodily terms, suggesting enhanced proprioceptive discrimination related to internal state monitoring.

3.4. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted in accordance with Braun, Clarke and Weate [

40]. A draft coding scheme was reviewed by an independent colleague to reduce potential bias. While the themes corresponded to structural features of the MAS protocol, deeper patterns emerged concerning perceptual processing, cognitive framing, and the interpretation of sensory experience.

Three primary themes were identified: Movement and Digital Embodiment, Awareness and Embodied Cognition, and Sensation and Emotional Absence. These themes captured the relationship between self-perceived movement, expert evaluation, and evolving somatic attention.

3.4.1. Movement and Digital Embodiment

The participant described herself as skilled and physically competent, rating her performance as effective and reporting ease with the MAS movements. However, expert review of recorded sessions revealed consistent mechanical repetition across all trials. Despite visible limitations such as reduced shoulder mobility and load imbalance, the participant maintained identical patterns without any observed variation. This uniform execution occurred even in situations where minor adjustments could have improved efficiency or comfort. When asked about this, the participant stated, “I just tried to perform as similar as it was possible,” and denied that the consistency was due to shyness or discomfort with being recorded.

This pattern highlights a fundamental contradiction. While the participant described her movements as conscious and intentional, she did not use the sessions to explore different amplitudes, ranges, or movement qualities. Instead, her behavior reflected motor control oriented toward visual mimicry rather than somatic inquiry. From a proprioceptive standpoint, this absence of variability suggests restricted kinesthetic freedom and limited internal feedback integration.

One expert observed, “She doesn’t have this exploration request and this is one of the problems of practitioners like her - midlife women in good shape. While they can go deeper and use a wide range of amplitudes, as L can do very different, they repeat the same. And in case of 3D movement philosophy, progress is endless. Because if, for example, in variations of shrimp squat your knee reaches the floor, you can always use a chair and again explore your progress.”

The body map data reinforced this interpretation. Markings remained focused on previously known discomfort zones, particularly under the right shoulder blade, and showed little change over time. Post-relaxation maps presented broad, undifferentiated body contours rather than nuanced sensory responses. Experts interpreted this as attentiveness to form without corresponding proprioceptive depth or exploratory movement capacity, which was one explanation for the limited improvement observed after eight consecutive days of practice.

3.4.2. Awareness and Embodied Cognition

Participant L described a strong sense of bodily awareness, expressing confidence in her ability to visualize alignment, monitor posture, and sense body position throughout the exercises. She reported performing tasks with both visual input and eyes closed, noting an internal sense of spatial orientation. Despite these assertions, her awareness was primarily structured around visual-spatial outcomes rather than kinesthetic experience. Descriptions centered on form, joint position, and movement precision, with limited reference to evolving bodily sensations.

This outcome-focused style became evident during feedback processing. Modifications such as reducing effort or increasing range were implemented accurately, but only after explicit instruction. There were no signs of spontaneous adjustment or somatic self-correction. Rather than using internal cues to guide changes, Participant L appeared to evaluate her performance against externally derived standards.

Written reflections and screening forms reinforced this pattern. Exercises were described in terms of task difficulty or completion success, with little attention given to transitional flow or the process of internal sensing. Movement was treated as a sequence to be executed correctly, not as a means of bodily inquiry. Her attentiveness, though sustained and precise, functioned more as supervisory control than as immersive awareness.

In the interview, she explained that movement improvisation was not a personal goal. Her interest lay in creating new combinations of familiar exercises rather than generating novel movement patterns. When discussing her own practice, she described the challenge of identifying complex movements in video materials and figuring out how to perform them correctly. This process was seen as a problem-solving task involving visual recognition followed by accurate repetition. Although this approach demonstrated persistence and strategic learning, it highlighted an externally anchored model of understanding, with minimal proprioceptive engagement.

Participant L also reported no effort to compare her performance with others. She did not view other examples and expressed no desire to assess herself through comparison. This limited reference to external variation suggested underuse of relational proprioception, the capacity to modulate and evaluate bodily action in relation to other bodies or contextual norms.

The overall pattern reflected a model of awareness rooted in visual cognition and structured analysis. While control and monitoring were evident, these did not translate into sensorimotor adaptability or introspective refinement. Her attentional focus remained fixed on outcome and accuracy, with limited translation into embodied responsiveness.

3.4.3. Sensation and Emotional Absence

Sensation emerged as the least articulated aspect of Participant L's experience. She remarked directly that bodily sensations could be misleading, referencing instances where her perception diverged from physical reality. During somatic screening, she reported feeling as though she was lying on stairs when in fact she was on a flat surface. Similarly, she described balance instability during test execution, although video recordings showed relatively stable posture. These discrepancies were not reconciled through internal adjustment but only recognized after external review, indicating an underdeveloped internal body map and limited interoceptive calibration.

Interview responses and written reflections were marked by brevity and neutrality. Descriptions of bodily sensation were confined to factual observations, with no elaboration on metaphor, emotion, or symbolic resonance. Sensory input appeared to be treated primarily as data for performance monitoring rather than a pathway to deeper introspective awareness. Participant L did not frame movement in terms of catharsis, grounding, or affective release, and showed no inclination to explore sensation as a source of personal or emotional insight.

Body maps reflected this lack of expressive depth. Markings were minimal and tended to cluster around familiar points of discomfort, without variation in tone, mood, or subjective interpretation. The visual and verbal language used to describe sensation remained literal and unembellished. Although Participant L expressed appreciation for the MAS protocol and its potential utility, her reflections conveyed a functional orientation toward movement, devoid of any narrative of transformation or embodied self-discovery.

This pattern of response suggests limited integration between proprioceptive and emotional domains. While somatic awareness was present at a cognitive level, it did not appear to extend into affective processing or embodied emotional literacy. The absence of symbolic, metaphoric, or relational language around sensation indicates a restricted use of the body as a medium for self-understanding.

4. Discussion

This first-phase evaluation demonstrates the feasibility and interpretive depth of the MAS protocol as a home-based, low-tech system for proprioceptive screening and training in midlife women. The participant consistently engaged with all components of the protocol, including structured movement practice, body mapping, and self-assessment. While the intervention yielded qualitative gains in somatic awareness and self-reflection, it also exposed clear limitations in proprioceptive accuracy and the reliability of self-evaluation.

Pre- and post-assessment findings consistently showed that the participant overestimated her performance in both static and dynamic tasks. This pattern persisted despite the use of video recordings and structured reflective prompts, suggesting a disconnect between perceived and actual ability. Such misalignment may indicate a disruption or underdevelopment of the body schema. This condition is potentially common among individuals going through the menopausal transition. According to body schema theory, the internal model that guides movement relies on continuous updates through accurate proprioceptive feedback. When this feedback is distorted or inadequately processed, postural control and coordination may decline even if the individual feels confident in her performance.

The participant's limited progress in complex tasks such as side planks and single-leg balance, despite her sense of improvement, highlights the need for objective reference points during training. Expert evaluations identified motor inaccuracies and postural compensation strategies that the participant did not recognize on her own. These observations confirm that self-assessment alone is not sufficient for guiding motor learning or refining the body schema. Future versions of the MAS protocol should include external feedback mechanisms such as AI-based motion tracking or annotated video analysis to support more accurate self-monitoring and motor correction.

Furthermore, the somatic screening and body mapping exercises revealed a weak connection between sensory awareness and emotional experience. The participant’s reflections focused mostly on alignment and physical positioning, with little mention of sensation, emotional tone, or subtle kinesthetic cues. This suggests that although she attended to the visual and mechanical aspects of movement, the sensory and emotional dimensions essential for body schema refinement remained underdeveloped. To address this gap, future iterations of the protocol should include expanded prompts that guide users toward deeper sensory reflection and emotional tracking alongside physical analysis.

Theoretically, the MAS protocol encourages engagement with the body schema through diverse movement experiences and structured proprioceptive reflection. However, its effectiveness as a schema-based training approach depends on providing clearer guidance, reliable feedback tools, and methods for emotional integration. These findings are consistent with broader research on home-based and digital movement programs. While such programs offer promise, they often require additional tools to replace the nuanced feedback that in-person practitioners typically provide.

Although the protocol was designed for flexible, low-tech use, this evaluation suggests that participants may benefit from added support, such as video analysis, structured tutorials, or AI-assisted feedback. The low-tech version remains valuable for accessibility but may be more effective when combined with scalable digital tools.

5. Conclusions

This single-case evaluation provides preliminary support for the MAS protocol as a feasible and accessible tool for proprioceptive training and body schema refinement among midlife women.

While the participant showed strong engagement and reflective interest, the study identified consistent overestimation in self-assessments, limited emotional engagement, and underdeveloped sensory differentiation. These findings highlight the importance of external feedback and structured guidance in home-based movement programs.

The MAS protocol offers a promising model that combines somatic methods with self-monitoring and flexible delivery. However, to maximize its effectiveness and safety, future iterations should incorporate clearer scoring tools, guided sensory reflection, and technology-assisted feedback. As a foundation for future research, this study supports the potential of hybrid digital-somatic interventions to empower proprioceptive awareness and movement intelligence in populations with limited access to traditional in-person training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology, writing—original draft preparation,; writing—review and editing, ES. Author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved a single healthy, competent adult participant and used non-invasive, low-risk procedures. According to institutional and national guidelines, formal ethical approval was not required. All procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participant provided written informed consent. An unsigned version of the consent form is included in the supplementary materials to ensure confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper. The participant gave explicit permission for anonymized data and images to be used in scientific publications.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the personal and individual nature of this single-case study, audio, video, and written data generated or analyzed during the current research are not publicly available. However, these materials may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to privacy and ethical considerations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to begin by sincerely thanking Participant L for her time and dedication to this study. Despite late hours, personal discomfort, or other challenges, she remained fully engaged and committed, making this research possible. I am also deeply grateful to the experts who carefully reviewed the materials and shared their valuable insights. A special thanks to Zarina Del Mar, who went a step further by designing customized practices to help Participant L confront the study’s goals in a meaningful and challenging way.

Conflicts of Interest

The author provides independent consulting services to Zarina del Mar LLC, the organization that developed the 3D movement method integrated into the MAS protocol. While Zarina del Mar designed the specific practice sequence for the single participant, her involvement in this study was strictly limited to expert commentary on the practice component. She had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or direct contact with the participant. All feedback was mediated solely by the author.

References

- Hillier, S.; Immink, M.; Thewlis, D. Assessing proprioception: a systematic review of possibilities. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuthill, J.C.; Azim, E. Proprioception. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R194–R203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héroux, M.E.; Butler, A.A.; Robertson, L.S.; Fisher, G.; Gandevia, S.C. Proprioception: a new look at an old concept. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proske, U.; Gandevia, S. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signalling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1651–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthoz, A. The Brain’s Sense of Movement (Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Nieto-Guisado, A.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Cabrejas, C.; Morales, J. The effects of an 8-week cognitive–motor training program on proprioception and postural control under single and dual task in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röijezon, U.; Clark, N.C.; Treleaven, J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Part 1: Basic science and principles of assessment and clinical interventions. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, T.; Gafuroğlu, Ü.; Aliyeva, A.; Elverici, E. Relationship between core stability and dynamic balance in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 64, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Baudry, S. Age-related changes in leg proprioception: implications for postural control. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevoorde, K.; Orban de Xivry, J.J. Does proprioceptive acuity influence the extent of implicit sensorimotor adaptation in young and older adults? J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 126, 1326–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-González, C.; Cueto-Ureña, C.; Cantón-Habas, V.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Healthy aging in menopause: prevention of cognitive decline, depression and dementia through physical exercise. Physiologia 2024, 4, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espírito Santo, J.; Aibar-Almazán, A.; Martínez-Amat, A.; de Loureiro, N.E. M.; Brandão-Loureiro, V.; Lavilla-Lerma, M.L.; Hita-Contreras, F. Menopausal symptoms, postural balance, and functional mobility in middle-aged postmenopausal women. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hita-Contreras, F.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Cruz-Díaz, D.; Pérez-López, F.R. Fall prevention in postmenopausal women: the role of Pilates exercise training. Climacteric 2016, 19, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, S.; Cheng, R.; Tsai, T.Y.; Wang, H. Sarcopenia in older adults is associated with static postural control, fear of falling and fall risk: A study of Romberg test. Gait Posture 2024, 112, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 3–44; erratum Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 209–801. [Google Scholar]

- Nitz, J.C.; Choy, N.L. Falling is not just for older women: Support for pre-emptive prevention intervention before 60. Climacteric 2008, 11, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; et al. Design of robot-assisted task involving visuomotor conflict for identification of proprioceptive acuity. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, Á.; Ferentzi, E.; Schwartz, K.; Jacobs, N.; Meyns, P.; Köteles, F. The measurement of proprioceptive accuracy: a systematic literature review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2023, 12, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AHan, J.; Waddington, G.; Adams, R.; Anson, J.; Liu, Y. Assessing proprioception: a critical review of methods. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, M.; Low, T.; Rajashekar, D.; Dukelow, S. White matter disconnection impacts proprioception post-stroke. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0310312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.T.; Piitz, M.A.; Singh, N.; Dukelow, S.P.; Cluff, T. The independence of impairments in proprioception and visuomotor adaptation after stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Lin, R.; Zeng, R.R.; Zhang, J.J. Psychometric properties of technology-assisted matching paradigms in post-stroke upper limb proprioceptive assessment: a scoping review. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1556111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzie, J.M.; Semrau, J.A.; Hill, M.D.; Scott, S.H.; Dukelow, S.P. A composite robotic-based measure of upper limb proprioception. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrotek, L.A.; et al. The Arm Movement Detection (AMD) test: A fast robotic test of proprioceptive acuity in the arm. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcelén-Fraile, M.D. C.; et al. Qigong for muscle strength and static postural control in middle-aged and older postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 784320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carbonell, E.; et al. Impact of multicomponent training frequency on health and fitness parameters in postmenopausal women: A comparative study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; et al. Effect of Tai Chi practice on the adaptation to sensory and motor perturbations while standing in older adults. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettee Gabriel, K.; Mason, J.M.; Sternfeld, B. Recent evidence exploring the associations between physical activity and menopausal symptoms in midlife women: perceived risks and possible health benefits. Womens Midlife Health 2015, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, J.J.; Dalla Via, J.; Jansons, P.; Scott, D.; Daly, R.M. Feasibility and acceptability of a remotely delivered, home-based, pragmatic resistance "exercise snacking" intervention in community-dwelling older adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Izquierdo, D.; de Teresa, C.; Mendoza, N. Exercise for peri- and postmenopausal women: recommendations from synergistic alliances of women's medicine and health psychology for the promotion of an active lifestyle. Maturitas 2024, 185, 107924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, D.O.; Standage, M.; Curran, T. Physical education in a post-COVID world: A blended-gamified approach. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q. Physical exercise in remote employees during covid-19. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2023, 29, e2022_0483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. How the Body Shapes the Mind (Clarendon Press, 2006).

- Diyakonova, O.; Habib, V.; Germanotta, M.; Taddei, K.; Bruschetta, R.; Pioggia, G.; Aprile, I.G. Body representation in stroke patients: A systematic review of human figure graphic representation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattin, D.; et al. An overview of the body schema and body image: theoretical models, methodological settings and pitfalls for rehabilitation of persons with neurological disorders. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, J.; McCarthy, P.; Jones, M.; Moran, A. Single-case research methods in sport and exercise psychology (Routledge, 2011).

- Frizziero, A.; Demeco, A.; Oliva, F.; Bigliardi, D.; Presot, F.; Faentoni, S.; Costantino, C. Changes in proprioceptive control in the menstrual cycle: a risk factor for injuries? A proof-of-concept study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2023, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobowik, P.; Wiszomirska, I.; Leś, A.; Kaczmarczyk, K. Selected tools for assessing the risk of falls in older women. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2065201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; et al. Real-time Pilates posture recognition system using deep learning model. In Int. Conf. Smart Homes Health Telematics 3–15 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

- Galofaro, E.; D’Antonio, E.; Patané, F.; Casadio, M.; Masia, L. Three-dimensional assessment of upper limb proprioception via a wearable exoskeleton. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skvortsov, D.; Painev, N. Postural stability Romberg’s test in 3D using an inertial sensor in healthy adults. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, M.; Gastaldi, L.; Pastorelli, S.; Tadano, S.; Agostini, V. Wearable inertial sensors to assess standing balance: a systematic review. Sensors 2019, 19, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, B.; et al. The relationship between single leg balance and proprioception of the knee joint in individuals with non-specific chronic back pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2024, 40, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, P.A. The Feldenkrais Method® of somatic education. In A Compendium of Essays on Alternative Therapy (ed. Peh, W.C. G.) 147–172 (InTech, 2012).

- Crivelli, D.; Di Ruocco, M.; Balena, A.; Balconi, M. The empowering effect of embodied awareness practice on body structural map and sensorimotor activity: The case of Feldenkrais Method. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentikäinen, J. Developing somatic writing from the perspective of the Feldenkrais method. Scriptum Creat. Writ. Res. J. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, K.; et al. Body maps: a generative tool for soma-based design. In Proc. 16th Int. Conf. Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction 2022, 1–14.

- Jager, A.D.; Tewson, A.; Ludlow, B.; Boydell, K. Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. 2016, 17, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise (eds. Smith, B. & Sparkes, A.C.) 213–227 (Routledge, 2016).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).