Submitted:

03 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

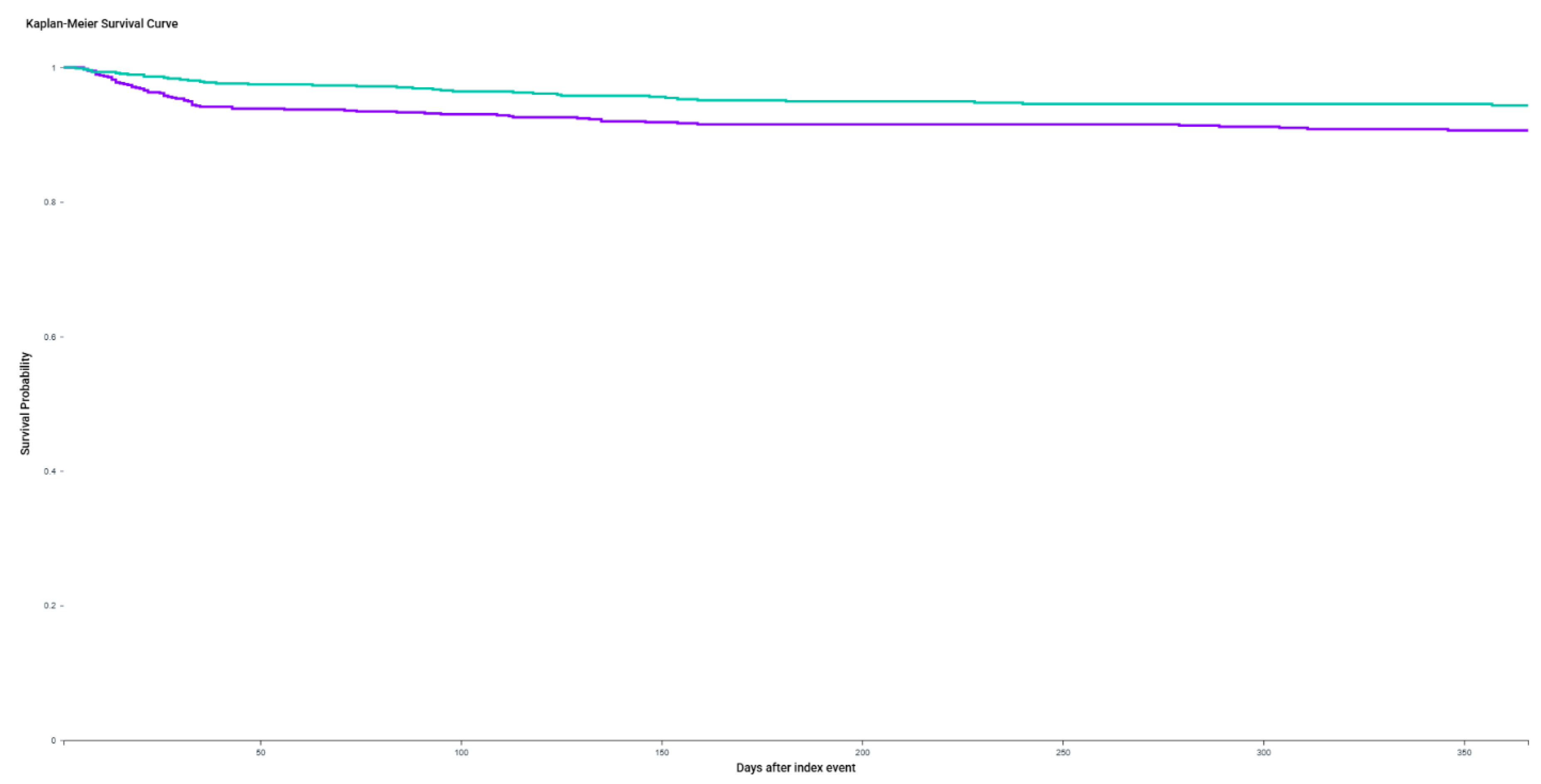

2.1. Urinary Retention

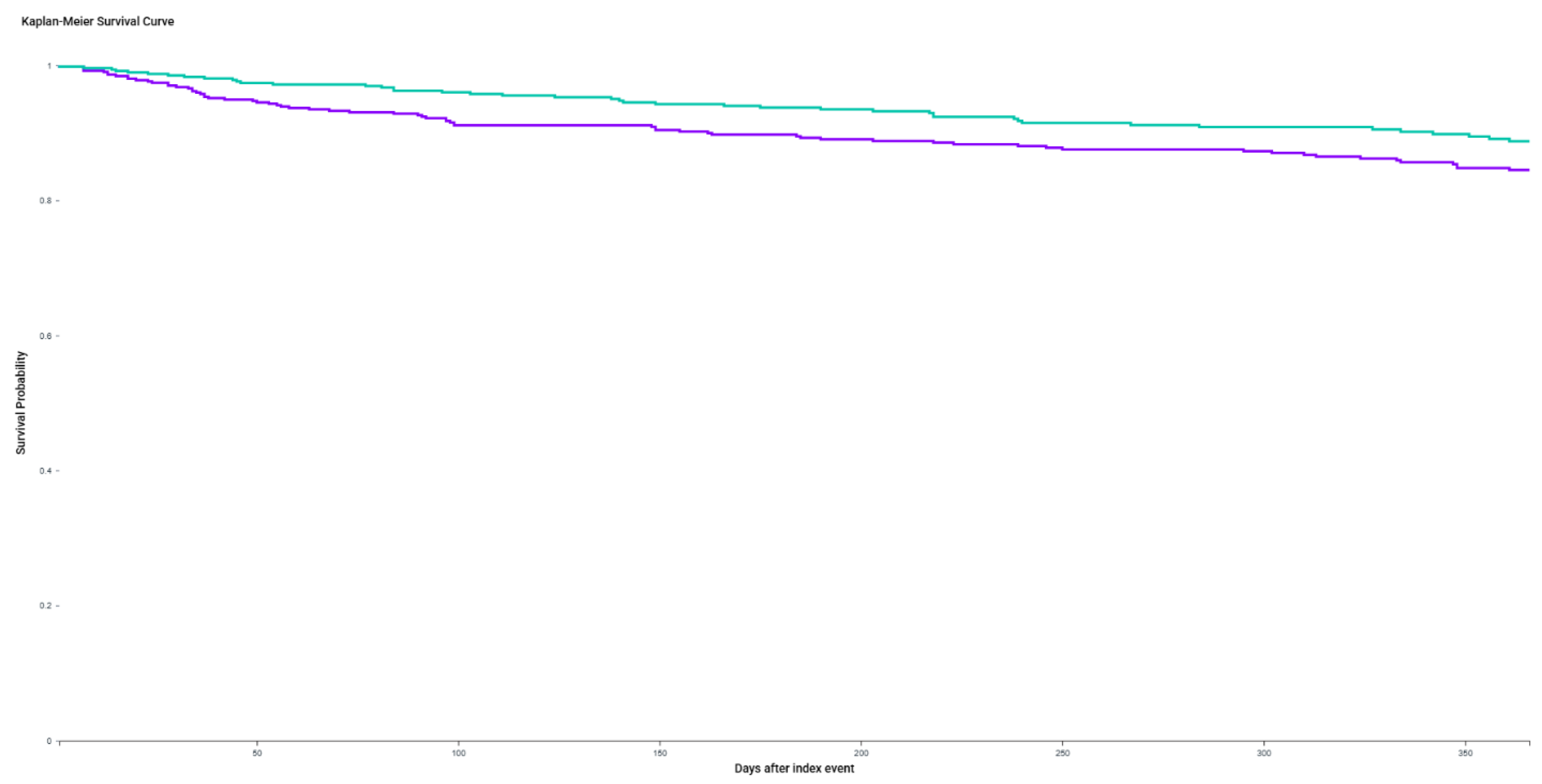

2.2. Urinary Tract Infection

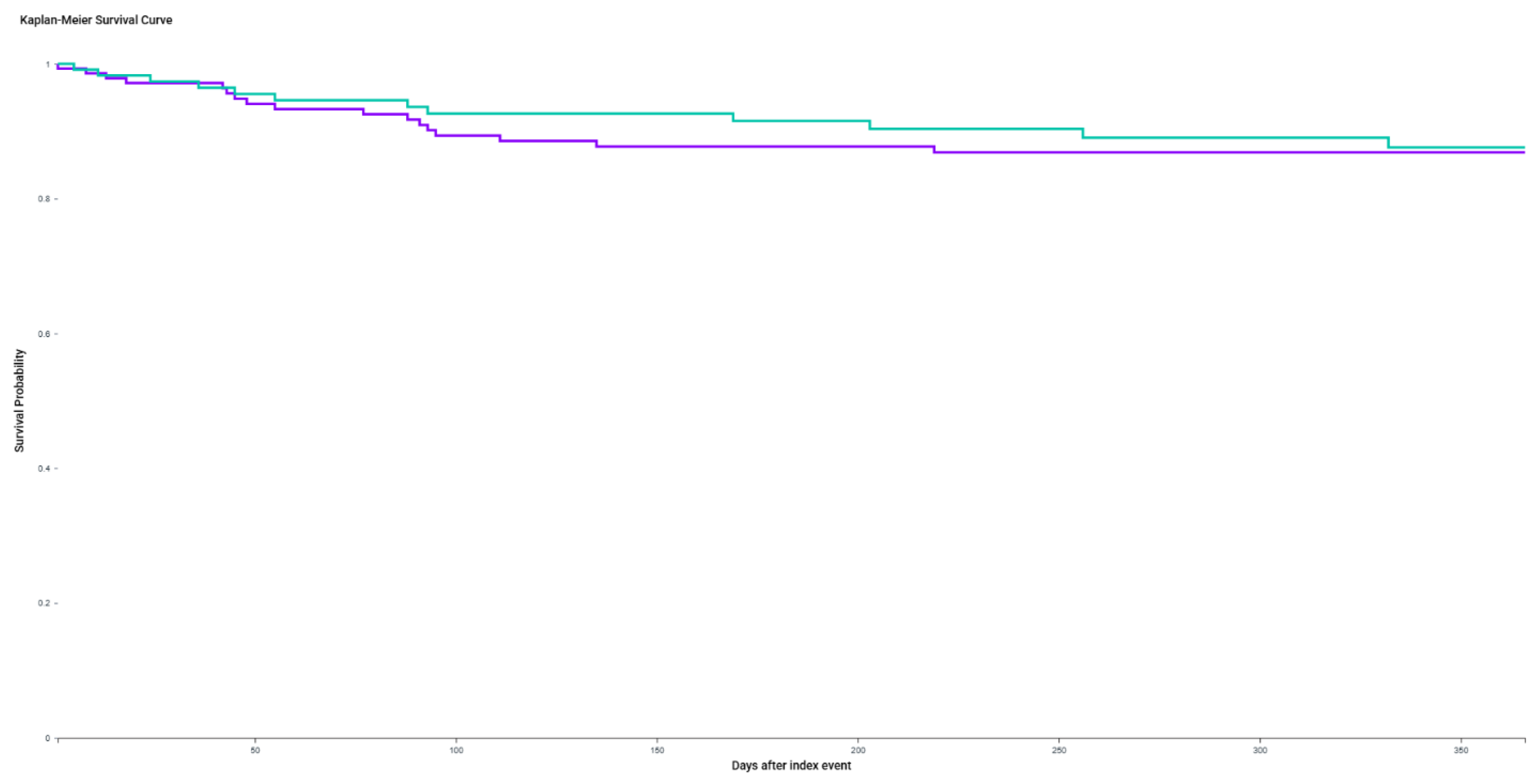

2.3. Urinary Antispasmodic Use

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement and Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OAB | Overactive bladder |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist |

| BOTOX | OnabotulinumtoxinA |

| KM | Kaplan-Meier |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ARC | Arcuate Nucleus |

| AP | Area Postrema |

| NTS | Nucleus Tractus Solitarius |

| POMC | Pro-Opiomelanocortin |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| AgRP | Agouti-Related Peptide |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| AUA | American Urological Association |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| ICD-10-CM | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| VA | Veterans Affairs (used in context of drug classes |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| TriNetX | A federated real world data research network/platform |

References

- Zhang L, Cai, Mo L, et al. Global prevalence of overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J, 2025. [CrossRef]

- UpToDate. Urgency urinary incontinence/overactive bladder (OAB) in females: Treatment. UpToDate. Updated 2025. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urgency-urinary-incontinence-overactive-bladder-oab-in-females-treatment (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Feloney MP, Stauss K, Leslie SW. Sacral Neuromodulation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567751/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Orasanu B, Mahajan ST. The use of botulinum toxin for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Indian J Urol. 2013, 29, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron AP, Chung DE, Dielubanza EJ, et al. The AUA/SUFU guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic overactive bladder. J Urol. 2024, 212, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines. In proceedings of the EAU Annual Congress, Madrid 2025. ISBN 978-94-92671-29-5.

- Chen YH, Kuo JH, Huang YT, Lai PC, Ou YC, Lin YC. Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Botulinum Toxin in Treating Overactive Bladder in the Elderly: A Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Toxins 2024, 16, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm KM, Abrams MK, Sears SB, et al. The Response of the Urinary Microbiome to Botox. Int Urogynecol J. 2024, 35, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitti V, Haag-Molkenteller C, Kennelly M, Chancellor M, Jenkins B, Schurch B. Treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity and overactive bladder with Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA): Development, insights, and impact. Medicine 2023, 102, e32377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo CW, Wu MY, Yang SS, Jaw FS, Chang SJ. Comparing the Efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA, Sacral Neuromodulation, and Peripheral Tibial Nerve Stimulation as Third Line Treatment for the Management of Overactive Bladder Symptoms in Adults: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Toxins 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh PF, Chiu HC, Chen KC, Chang CH, Chou ECL. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of overactive bladder. Toxins 2016, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semins MJ, Shore AD, Makary MA, Weiner J, Matlaga BR. The impact of obesity on urinary tract infection risk. Urology 2012, 79, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch K, Stangl FP, Prieto J, Bonkat G, Kranz J. Urinary infection management in frail or comorbid older individuals. Eur Urol Focus. 2024, 10, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagovska M, Švihra J, Buková A, et al. The Relationship between Overweight and Overactive Bladder Symptoms. Obes Facts. 2020, 13, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khullar V, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Milsom I, Bitoun CE, Coyne KS. The relationship between BMI and urinary incontinence subgroups: results from EpiLUTS. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014, 33, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing W, Wei C, Huang Y, Fu T, Shen W, Xiao W. Relationship between the weight-adjusted-waist index and urinary incontinence in women: A cross-sectional study of NHANES 2007 to 2020. Medicine 2025, 104, e42996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Chen W, Tang Z, et al. The Association between Obesity and Wet Overactive Bladder: Results from 2005 to 2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Obes Facts, 11 May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pomian A, Lisik W, Kosieradzki M, Barcz E. Obesity and Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Review of the Literature. Med Sci Monit. 2016, 22, 1880–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel N, Masoumi SZ, Haghani S, Rajati F. The effect of weight loss on overactive bladder symptoms in overweight and obese women: a systematic review. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2024, 13, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins L, Costello RA. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Updated February 29, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu D, Nair A, Sigston C, et al. Potential Roles of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in Nondiabetic Populations. Cardiovasc Ther. 2022, 2022, 6820377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al; SELECT Trial Investigators Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink HJL, Apperloo E, Davies M, et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Albuminuria and Kidney Function in People With Overweight or Obesity With or Without Type 2 Diabetes: Exploratory Analysis From the STEP 1, 2, and 3 Trials. Diabetes Care. 2023, 46, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena H, Chiovato L, Nappi RE. Obesity, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Infertility: A New Avenue for GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 105, e2695–e2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Tan J, Yuan Y, Shen J, Chen Y. Semaglutide ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting HDAC5-mediated activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2022, 41, 9603271221125931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnaien A, Mohammad A, Hassan E. Neuroprotective Effects of Semaglutide in Endotoxemia Mouse Model. Iran J War Public Health. 2023, 15, 199–205.

- Tan SA, Tan L. liraglutide and semaglutide attenuate inflammatory cytokines interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6: possible mechanism of decreasing cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2019, 73, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenzon O, Capehorn MS, De Remigis A, Rasmussen S, Weimers P, Rosenstock J. Impact of semaglutide on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: exploratory patient-level analyses of SUSTAIN and PIONEER randomized clinical trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdany T, Jakus-Waldman S, Jeppson PC, et al. American Urogynecologic Society Systematic Review: The Impact of Weight Loss Intervention on Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Urinary Incontinence in Overweight and Obese Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020, 26, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacche MM, Giarenis I, Thiagamoorthy G, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Is there an association between aspects of the metabolic syndrome and overactive bladder? A prospective cohort study in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017, 217, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungberg C, Bredahl Kristensen FP, Dalager-Pedersen M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M, Thomsen RW. Risk of Urogenital Infections in People With Type 2 Diabetes Initiating SGLT2is Versus GLP-1RAs in Routine Clinical Care: A Danish Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 20 May 2025, 48, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave CV, Schneeweiss S, Kim D, Fralick M, Tong A, Patorno E. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and the Risk for Severe Urinary Tract Infections: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019, 171, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soogoor AR, Agrawal P, Pupo D, Kohn TP, Du Comb W, Alshak MN. MP45-11 Semaglutide Utilization In Weight Management and its Implications for Urinary Tract Infections and Urolithiasis. Jour. of Urology 2024, 211, e746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler MD, Williams AD, Wein A, et al. Effects of Glucagon like Peptide-1 agonists on patients with overactive bladder: A pilot study. Continence Reports 2025, 14, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan HC, Dampil OA, Marquez MM. Efficacy and Safety of Semaglutide for Weight Loss in Obesity Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2022, 37, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doumouchtsis SK, Loganathan J, Pergialiotis V. The role of obesity on urinary incontinence and anal incontinence in women: a review. BJOG. 2022, 129, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan O, Elias M, Chazan B, Saliba W. Urinary tract infections in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: review of prevalence, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed AE, Abdelkarim S, Zenida M, et al. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Urinary Tract Infection among Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Able C, Liao B, Saffati G, et al. Prescribing semaglutide for weight loss in non-diabetic, obese patients is associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction: a TriNetX database study. Int J Impot Res. 2025, 37, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varnum AA, Pozzi E, Deebel NA, et al. Impact of GLP-1 Agonists on Male Reproductive Health-A Narrative Review. Medicina 2023, 60, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajahjeh A, Al-Faouri R, Bahmad HF, et al. From Diabetes to Oncology: Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonist's Dual Role in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabhari Langroudi, A. , Chen, A.L., Basran, S. et al. Male sexual dysfunction associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: a cross-sectional analysis of FAERS data. Int J Impot Res. [CrossRef]

- Fang A, Frigo DE, Hahn A, et al. GLP-1 Agonist Use Among Men With Localized Prostate Cancer: A Narrative Review and Rationale for Prospective Clinical Trials. Urology 2025, 201, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvio G, Ciarloni A, Ambo N, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists on testicular dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. [CrossRef]

- Nomiyama T, Kawanami T, Irie S, et al. Exendin-4, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, attenuates prostate cancer growth. Diabetes. 2014, 63, 3891–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Dong M, Feng G, et al. Semaglutide mitigates testicular damage in diabetes by inhibiting ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024, 715, 149996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippatos TD, Panagiotopoulou TV, Elisaf MS. Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. Rev Diabet Stud. 2014, 11, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung SD, Liu HT, Lin H, Kuo HC. Elevation of serum c-reactive protein in patients with OAB and IC/BPS implies chronic inflammation in the urinary bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011, 30, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu HT, Jiang YH, Kuo HC. Increased serum adipokines implicate chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of overactive bladder syndrome refractory to antimuscarinic therapy. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e76706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillalamarri N, Shalom DF, Pilkinton ML, et al. Inflammatory Urinary Cytokine Expression and Quality of Life in Patients With Overactive Bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018, 24, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy L, Caldwell A, Brierley SM. Mechanisms Underlying Overactive Bladder and Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. Front Neurosci. 2018, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng X, Zhou J, Zhao CN, Gan RY, Li HB. Health Benefits and Molecular Mechanisms of Resveratrol: A Narrative Review. Foods. 2020, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh I, Wang L, Xia B, et al. Activation of arcuate nucleus glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-expressing neurons suppresses food intake. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014, 124, 4473–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jais A, Brüning JC. Arcuate Nucleus-Dependent Regulation of Metabolism-Pathways to Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2022, 43, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddows CA, Shi F, Horton AL, et al. Pathogenic hypothalamic extracellular matrix promotes metabolic disease. Nature. 2024, 633, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright EE Jr, Aroda VR. Clinical review of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes considered for injectable GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy or currently on insulin therapy. Postgrad Med. 2020, 132, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang KP, Acosta AA, Ghidewon MY, et al. Dissociable hindbrain GLP1R circuits for satiety and aversion. Nature 2024, 632, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | OAB + BOTOX (Before Matching) | OAB + BOTOX + GLP1 RA (Before Matching) | P-Value (Before Matching) | SMD (Before Matching) | OAB + BOTOX (After Matching) | OAB + BOTOX + GLP1 RA (After Matching) | P-Value (After Matching) | SMD (After Matching) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Index (Mean ± SD) | 62.4 ± 17.6 | 59.4 ± 13.2 | < 0.0001 | 0.1935 | 59.3 ± 13.9 | 59.4 ± 13.2 | 0.8073 | 0.011 |

| Female | 15,971 (80.2%) | 904 (91.1%) | < 0.0001 | 0.315 | 913 (92.0%) | 904 (91.1%) | 0.4668 | 0.0327 |

| Male | 3,563 (17.9%) | 63 (6.4%) | < 0.0001 | 0.3594 | 59 (5.9%) | 63 (6.4%) | 0.7085 | 0.0168 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 15,513 (77.9%) | 800 (80.6%) | 0.0435 | 0.0671 | 802 (80.8%) | 800 (80.6%) | 0.9093 | 0.0051 |

| White | 15,858 (79.7%) | 752 (75.8%) | 0.0034 | 0.0927 | 770 (77.6%) | 752 (75.8%) | 0.339 | 0.0429 |

| Black or African American | 1,706 (8.6%) | 127 (12.8%) | < 0.0001 | 0.1373 | 115 (11.6%) | 127 (12.8%) | 0.4104 | 0.037 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,333 (6.7%) | 69 (7.0%) | 0.7498 | 0.0103 | 71 (7.2%) | 69 (7.0%) | 0.8608 | 0.0079 |

| Asian | 339 (1.7%) | 10 (1.0%) | 0.0955 | 0.0601 | 10 (1.0%) | 10 (1.0%) | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Overweight/Obesity (E65-E68) | 5,216 (26.2%) | 756 (76.2%) | < 0.0001 | 1.1554 | 755 (76.1%) | 756 (76.2%) | 0.958 | 0.0024 |

| Hypertension (I10) | 8,944 (44.9%) | 575 (58.0%) | < 0.0001 | 0.2631 | 564 (56.9%) | 575 (58.0%) | 0.6175 | 0.0224 |

| Stress Incontinence (N39.3) | 5,398 (27.1%) | 389 (39.2%) | < 0.0001 | 0.2591 | 391 (39.4%) | 389 (39.2%) | 0.9268 | 0.0041 |

| BMI 40-44.9 (Z68.41) | 880 (4.4%) | 214 (21.6%) | < 0.0001 | 0.5275 | 219 (22.1%) | 214 (21.6%) | 0.7858 | 0.0122 |

| BMI 45-49.9 (Z68.42) | 431 (2.2%) | 110 (11.1%) | < 0.0001 | 0.3647 | 104 (10.5%) | 110 (11.1%) | 0.6641 | 0.0195 |

| BMI 29-29.9 (Z68.29) | 453 (2.3%) | 53 (5.3%) | < 0.0001 | 0.1608 | 48 (4.8%) | 53 (5.3%) | 0.6096 | 0.0229 |

| BMI 28-28.9 (Z68.28) | 457 (2.3%) | 40 (4.0%) | 0.0005 | 0.0993 | 37 (3.7%) | 40 (4.0%) | 0.7273 | 0.0157 |

| BMI 27-27.9 (Z68.27) | 461 (2.3%) | 37 (3.7%) | 0.0044 | 0.0827 | 38 (3.8%) | 37 (3.7%) | 0.9063 | 0.0053 |

| Antimicrobials (AM000) | 17,619 (88.5%) | 976 (98.4%) | < 0.0001 | 0.4075 | 928 (93.5%) | 976 (98.4%) | < 0.0001 | 0.2479 |

| Antiemetics (GA605) | 12,021 (60.4%) | 832 (83.9%) | < 0.0001 | 0.5427 | 745 (75.1%) | 832 (83.9%) | < 0.0001 | 0.2185 |

| Laxatives (GA200) | 11,381 (57.2%) | 740 (74.6%) | < 0.0001 | 0.3739 | 680 (68.5%) | 740 (74.6%) | 0.0028 | 0.1344 |

| Anti-infectives, vaginal (GU300) | 7,163 (36.0%) | 585 (59.0%) | < 0.0001 | 0.4731 | 518 (52.2%) | 585 (59.0%) | 0.0025 | 0.1362 |

| Outcome | Event Rate (BOTOX group) | Event Rate (BOTOX+GLP-1 group) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | KM Log-Rank p | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Retention | 8.60% | 4.90% | 3.66% (1.16-6.17%) | 0.0064 | 1.74 (1.16-2.59) |

| UTI | 13.30% | 8.80% | 4.54% (0.67-8.40%) | 0.042 | 1.48 (1.01-2.17) |

| Antispasmodic Use | 11.80% | 10.30% | 1.55% (-6.07 to 9.17%) | 0.7234 | 1.14 (0.55-2.39) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).