1. Introduction

The global burden of prostate cancer PCa among the population of men is recognised as an increasing global public health concern [

1,

2,

3]. Black men have the highest disproportional prevalence of PCa than any other racial group across the globe [

4]. The reasons for the disproportionate burden of PCa among men of African ancestry remain unclear [

5]. In South Africa, PCa is the most common cancer in men across all population groups with black men having the highest incidences than any other racial group [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Equally concerning is the fact that black men frequently present with more advanced and aggressive stage of the disease at diagnosis [

6,

7]. Some of the reasons for black men presenting late at PCa diagnosis and with more advanced stage of the disease include limited access to healthcare [

10], lack of awareness of screening and early detection programs [

7,

11], and poor knowledge of the disease among black communities in South Africa [

1,

10,

12]. Additionally, black men are also less likely to participate in clinical research, making it difficult to understand the true burden associated with PCa [

13].

With improvement screening practices and advancement in treatment options, most PCa patients now live for a decade or longer following diagnosis in both high-income countries (HICs) as well as low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) [

14,

15,

16]. As more men diagnosed with PCa live for a long period beyond their diagnosis, attention is increasingly shifting to the psychological issues associated with the disease [

15,

17]. A focus on PCa patients’ quality of life (QOL), including health-related quality of life (HRQOL), is fast gaining momentum in research and clinical practice [

18]. Men suffering from PCa have to live with their debilitating disease symptoms as well as treatment side effects. All these will have far-reaching impact on the patient’s QOL, including HRQOL [

19].

There are a variety of treatment options available for PCa patients. These different treatment options are usually based on the stage of the PCa at diagnosis [

15]. According to [

15], the primary goal of PCa treatment is to cure, prolong survival, or aid in palliative care. Unfortunately, each PCa treatment option has its own side-effects. The most common side-effects of most PCa treatment options include erectile dysfunction (ED), bowel and urinary incontinence [

20,

21,

22]. Due to these treatment side-effects, particularly ED, PCa patients’ masculinity (i.e., a sense of being a man) may be adversely affected [

21]. In some societies, including in Africa, ideas about masculinity and what it means to be a ‘man’ are intimately tied to certain cultural expectations, norms, and practices [

23]. According to [

20], sexuality is not an isolated phenomenon but rather an integral part of a man’s identity and lifestyle. Enactment of gender scripts, that is, ways of thinking, feeling, and acting are based on culturally prescribed norms of masculinity. PCa treatment induced ED may disrupt the identity of men who define masculinity through (hetero) sexual penetrative intercourse and performance.

The theory of hegemonic masculinity contents that masculinity is a culturally constructed ideal of what it means to be a man [

21]. It proposes that masculinity is not biologically determined but a socially constructed concept that emphasises the interplay between men’s identity, ideals, interactions, power and patriarchy [

23]. Framed within the theory of hegemonic masculinity, the aim of this study was to investigate how black South African PCa survivors understand the impact of their PCa disease, including treatment side-effects, on their masculinity and self-identity.

2. Methods

Study Design

The study was part of a bigger project investigating the lived experiences of a group of black South African PCa patients. The study utilized a hermeneutic phenomenological study design. Hermeneutic studies are concerned with the scientific investigation of human experiences as it is lived [

24]. According to [

25], human beings create meanings in the different experiences that shape their lives.

Sampling

The study utilized a purposive sampling method to select twenty [

20] black South African men who were receiving some form of PCa treatment at a tertiary hospital in Limpopo Province, South Africa. The study comprised 20 elderly black South African PCa survivors selected through purposive sampling. Both practical as well as theoretical considerations formed the basis the sample size as well as selection procedure. According to Smith and Osborn [

26], a distinctive feature of feature of phenomenological inquiry is its commitment to detailed account of participants’ narrative account of their experiences and this can only be achieved with a small sample.

Individual Interviews

In-depth, individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 black South African PCa survivors who were receiving some form of treatment at Pietersburg Provincial Hospital. The hospital is a tertiary institution were PCa patients from the different parts of the Province of Limpopo receive oncology treatment. Inclusion criteria included the following: black South African citizen, PCa diagnosis for at least five years before the interview, and able to communicate in one of the most commonly spoken languages in the Province of Limpopo i.e., English, Sepedi, Xitsonga and Tshivenda. Exclusion criteria included the following: individuals who fulfill the inclusion criteria but not wishing to take part, had mental health problems that may exacerbate any adverse feelings that may arise during the interviews, and those who did not speak any of the identified local languages. Each individual interview was audio recorded (after permission was obtained from each participant) and transcribed (verbatim) from the local languages of each participant into English for the broader scientific community.

Semi-structured interviews allow space for rich, detailed, first person account of human experience which the researcher may inquire in detail with prompt probing questions. An interview guide, with a set of questions, was used to collect data. Each individual interview took approximately one hour to complete. The interview guide included some of the following statements: tell me about your experiences with the prostate cancer disease and share with me how you cope with the disease.

Data Analysis

IPA was used to analyse the data obtained in the study. The main strength of IPA is its ability to give full account of each participant’s personal experience [

25]. The primary aim of IPA is to explore, in detail, how each participant makes sense of their experiences. The method is compatible with hermeneutic phenomenology. The method (IPA) was deemed appropriate because the study was interested in understanding the experiences of living with PCa induced side-effects by the participants. Each case-by-case analysis was conducted by the primary researcher who is experienced in the art of IPA.

Ethics

Prior to the commencement of the study, permission was obtained from the following institutional bodies: University of Limpopo Research Ethics Committee (TEC/26/2015), Limpopo Provincial Department of Health Ethics Committee (Ref:4/2/2) as well as a Gate Keeper permission from Pietersburg Provincial Hospital (Ref:2/8/2). All the participants in the study signed informed consent forms.

Trustworthiness of the Study

Credibility, transferability, dependability and conformity (to ensure trustworthiness) was observed in the study. All the five research team members (experienced clinical psychologists) cross-checked the data analysis and involved themselves in a reflective engagement of a dialogue with the participants’’ narratives and meanings to ensure trustworthiness of the study.

3. Results

All the participants in the study were diagnosed with PCa for at least five years (>5 years) before the study commencement. All were men between 67 and 85 years of age (n=20; mean age =76.2; SD=5.3). The majority had primary school education (n=15), retired (n=13), receiving government social security grant (n=7). All, except one, had no family history of prostate cancer. All participants had poor knowledge of PCa and had never participated in any screening for the risk of prostate cancer prior to their formal diagnosis. In their majority (n =16) reported ED and differing loss of their masculinity (n=14).

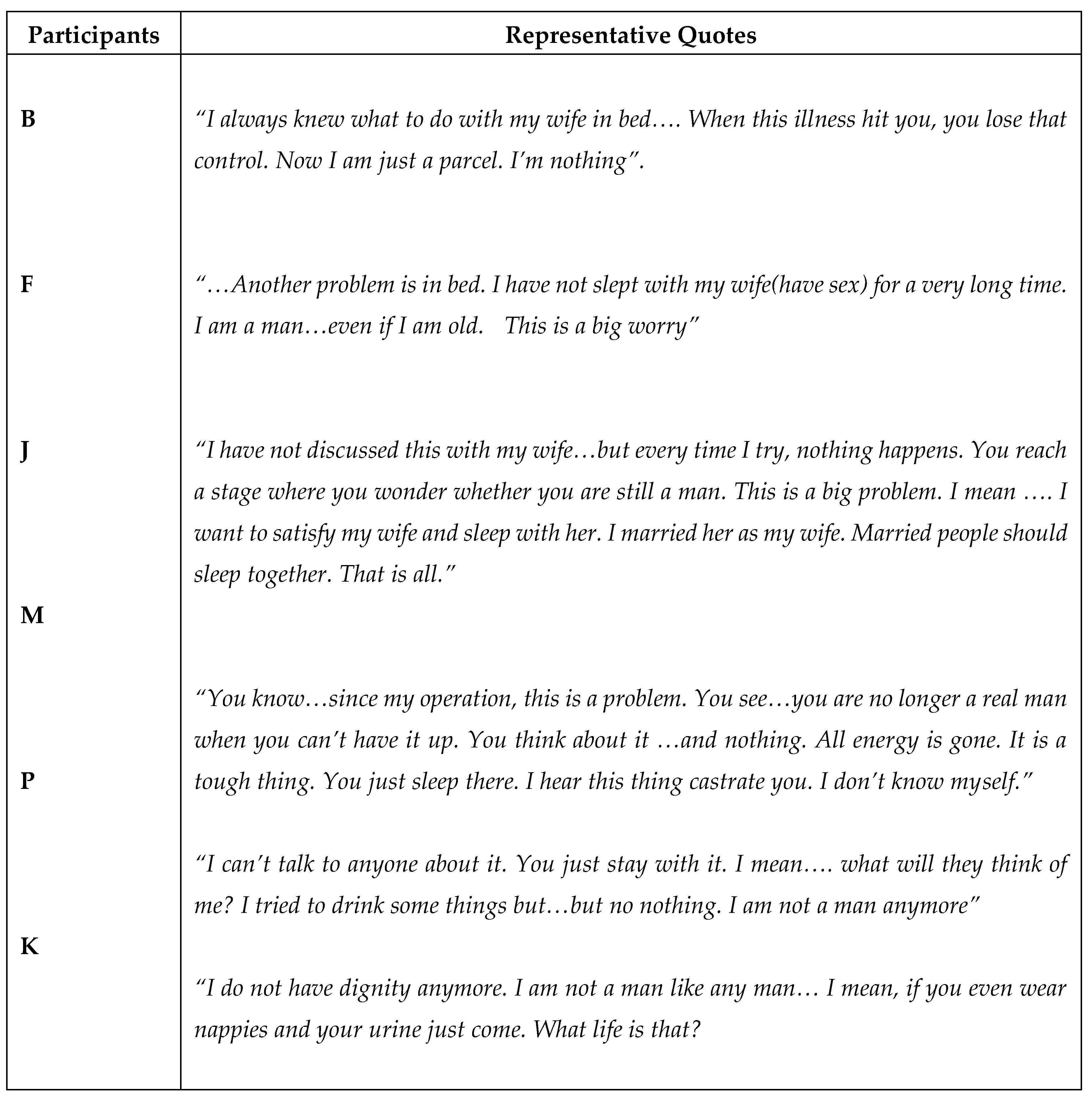

The table below (

Table 1) highlights some of the participants’ narratives about the impact of PCa treatment induced ED on their masculinity. Subsequently, a discussion of the findings is offered.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of PCa treatment side-effects (ED) on masculinity among black South African survivors. According to [

27], hegemonic masculinity emphasises the pursuit of toughness and self-reliance as the cornerstones of what it means to be a man. This pursuit is achieved through certain gender role expectations that are socialized early in life through which men internalize certain attitudes and behaviours associated with masculinity [

21]. Consequently, treatment induced ED may threaten PCa patients’ overall sense of masculinity. According to [

14], hegemonic masculinity (i.e., a man’s identity – a sense of them being a man) may be linked to how men perceive themselves and respond to PCa diagnosis and treatment, including their psychological adjustment. Sexual virility in men – the ability to complete conjugal duty through (hetero)sexual penetrative intercourse, is frequently considered an important aspect in traditional hegemonic masculine practices and ideals [

27]. According to [

22], PCa survivors may experience what is termed “double jeopardy” (i.e., they are first affected by the failure of erectile functioning (ED) and then by accompanying psychological distress of losing their masculinity.

The participants in the study narrated stories of unhappiness and a threat to their masculinity as a result of their inability attain an erection as a result of PCa induced ED. In their majority, the participants in the study narrated a loss of their masculinity (‘I am not a man’) as a result of their ED. Through the participants’ narrative stories, the participants demonstrated that sexual function is a central theme to perceptions of masculinity. The shame (‘I can’t talk about it’) evidenced in some participants’ narratives demonstrate that this threat to their masculinity created a vicious cycle and a conflation of the diminished erectile function and loss of manhood. This subsequently led to their questioning of their self-worth (‘I am nothing’). This suggests that participants in the study viewed their self-worth in terms of their sexual potency and the ability to achieve an erection. Men in the study valued sexual potency or virility as a script indicative of their masculinity. As a result, the men in the study construed failure to have an erection as unmasculine consequently leading to feelings of shame and humiliation. This is akin to a feeling of victimization experience that threatens a man’s socially constructed masculine identity. The findings in this study are consistent with previous research identifying that ED does impact negatively perceptions of mascualnity [

14,

20,

21,

22,

23,

27,

28,

29]. Additionally, most of the participants expressed a sense of “double jeopardy” (i.e., physical failure of the erectile functioning rendering penetrative sexual intercourse impossible as well as the associated psychological distress due to the loss of masculinity) that has been documented in other previous studies elsewhere [

20,

21,

22,

27,

28].

5. Conclusion

Based on the results of the study, it is evident that for most participants, masculinity is a critical factor in their experience of PCa treatment induced ED. Hegemonic masculinity appears to frame how the men in the study interpret what is happening to them. For the men in the study, masculinity suffered tremendous harm as a result PCa treatment induced ED leading to diminished QOL. Impotence and the inability to achieve an erection due to treatment induced ED can be received as a sexual failure and a threat to a man’s hegemonic masculinity. Our study suggests that in addition to the physical loss of sexual function through ED, many men undergoing PCa treatment experience adverse psychological distress leading to decreased HRQOL. Treatment induced ED poses serious threats to men’s scripts for hegemonic masculinity. How masculinity is impacted by treatment induced ED still remains unclear. There is, therefore, a need for empirical research to establish or identify factors that may interact with masculinity as a mediator of psychological outcomes for patients experiencing PCa induced ED. Additionally, given the role of masculinity as a critical factor in men’s perceptions of ED after PCa treatment, consideration should be given to holistic management interventions that are responsive to hegemonic masculinity. This calls for a collaboration between medical and psychological professionals for optimal management of PCa patients.

6. Limitations of the Study

Participants were elderly PCa patients and the results may not be generalizable to younger population groups among black South African men. Despite this, the results in this study may further contribute to the body of literature on the impact of different PCa treatment options on masculinity as well as the overall QOL of patients, which is currently lacking within the South African context.

Author Contributions

SE, the principal investigator of this study, contributed to the overall project design, management, and manuscript writing. TS gave insights on the qualitative analysis, and discussion. AL, MM, and KT contributed to manuscript draft writing and critical review of the final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received financial support from the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of Limpopo Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC/26/2016). Further permission was obtained from the Limpopo Provincial Department of Health (Ref:4/2/2) as well as Gate Keeper permission from Pietersburg Provincial Hospital (Ref:2/8/2).

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the study was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study before commencement.

Data Availability Statement

the data used in the study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the ethical nature of the study, which did not include data sharing.

Acknowledgments

All authors (SN., TS., AL., MM., & KT) sincerely acknowledge all the participants for sharing their information in the study. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. .

Declaration of conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- James, N. D., Tannock, I., N’Dow, J., Feng, F., Gillessen, S., Ali, S. A., Trujillo, B., Al-Lazikani, B., Attard, G., Bray, F., Compérat, E., Eeles, R., Fatiregun, O., Grist, E., Halabi, S., Haran, Á., Herchenhorn, D., Hofman, M. S., Jalloh, M., Loeb, S., … Xie, L. P. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: planning for the surge in cases. Lancet (London, England). 2024. 403(10437), 1683–1722. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018, 68(6), 394–424. [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.B., Albertsen, P.C., Barry, Stephen, R.E., & Freedland, S.J. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. Journal of Urology. 2023. 190: 419.

- Machirori, M., Patch, C., & Metcalfe, A. Study of the relationship between Black men, culture and prostate cancer beliefs. Cogent Medicine. 2018. 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Mutua, K., Pertet, A.M. & Otieno, C. Cultural factors associated with the intent to be screened for prostate cancer among adult men in a rural Kenyan community. BMC Public Health .2017. 17, 894. [CrossRef]

- John, J., Adam, A., Kaestner, L., Spies, P., Mutambirwa, S., & Lazarus, J. (2024). The South African Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines. South African Medical Journal, 114(5), e2194. [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M. O. A., Steinberg, W. J., Claassen, F. M., & Mofolo, N. The profile of Black South African men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the Free State, South Africa. South African family practice: official journal of the South African Academy of Family Practice/Primary Care. 2023. 65(1), e1–e10. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M. J. Investigating racial differences in clinical and pathological features of prostate cancer in South African men. (Thesis). 2016. University of Cape Town, Faculty of Health Sciences, Division of Urology. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11427/22753.

- Baratedi, W. M., Tshiamo, W. B., Mogobe, K. D., & McFarland, D. M. Barriers to Prostate Cancer Screening by Men in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Integrated Review. Journal of nursing scholarship : an official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing. 2020. 52(1), 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Mofolo, N., Betshu, O., Kenna, O., Koroma, S., Lebeko, T., Claassen, F. M., & Joubert, G. Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a urology clinic, a South African study. SpringerPlus. 2015. 4, 67. [CrossRef]

- Nkoana, S., Sodi, T., Themane, M. Prostate Cancer Knowledge, Beliefs and Screening Uptake among Black Survivors: A Qualitative Study at a Teriary Hospital, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2024,21,1212. [CrossRef]

- Maladze, N., Maphula, A., Maluleke, M., & Makhado, L. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Prostate Cancer and Screening among Males in Limpopo Province, South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023. 20(6), 5220. [CrossRef]

- Lillard, J. W., Jr, Moses, K. A., Mahal, B. A., George, D. J. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer, 2022.128(21), 3787–3795. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S. K., Chung, E., Wittert, G., & Hyde, M. K. Erectile dysfunction, masculinity, and psychosocial outcomes: a review of the experiences of men after prostate cancer treatment. Translational andrology and urology, 2017, 6(1), 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Latham, S., Leach, M. J., White, V. M., Webber, K., Jefford, M., Lisy, K., Davis, N., Millar, J. L., Evans, S., Emery, J. D., IJzerman, M., & Ristevski, E. Health-related quality of life in rural cancer survivors compared with their urban counterparts: a systematic review. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 2024, 32(7), 424. [CrossRef]

- Gudina, A. T., Cheruvu, V. K., Gilmore, N. J., Kleckner, A. S., Arana-Chicas, E., Kehoe, L. A., Belcher, E. K., & Cupertino, A. P. Health related quality of life in adult cancer survivors: Importance of social and emotional support. Cancer epidemiology, 2021, 74, 101996. [CrossRef]

- Lehto, U. S., Tenhola, H., Taari, K., & Aromaa, A. Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: a nationwide survey. British journal of cancer, 2017,116(7), 864–873. [CrossRef]

- Naccarato, A. M. E. P., Consuelo Souto, S., Matheus, W. E., Ferreira, U., & Denardi, F. Quality of life and sexual health in men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. The aging male : the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male, 2020.23(5), 346–353. [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A., & Zafar, S. Y. Health-Related Quality of Life: The Impact on Morbidity and Mortality. Surgical oncology clinics of North America, 2018.27(4), 675–684. [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, A., Ojala, H., Tammela., T., Pietila. Prostate Cancer-related sexual dysfunction – the significance of social relations in men’s reconstructions of masculanigty, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 2024. 26:6, 773-777,doi:/10.1080/13691058.2023.2250410.

- Andreasson, J., Johansson, T., & Danemalm-Jägervall, C. (2023). Men’s Achilles’ heel: prostate cancer and the reconstruction of masculinity. Culture, health & sexuality, 25(12), 1675–1689. [CrossRef]

- Walther, A., Rice, T., & Eggenberger, L. (2023). Precarious Manhood Beliefs Are Positively Associated with Erectile Dysfunction in Cisgender Men. Archives of sexual behavior, 52(7), 3123–3138. [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, J., Johansson, T., Danemalm-Jagervall, C. Prostate Cancer and the Emotionology of Masculanity: Joking, Intellectualization, and the Reconstruction of Gender. 2023. 3(3), 500-518.https://doi/10.1177/0608265231171031.

- Kafle, N.P. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Research Method Simplified. Bodhi: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2011. 5, 181-200. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology and Health. 1996. 11(2), 261-271. https://doi.10.1080/08870449608400256.

- Smith, J.A & Osborn, M. Pain as an assault on the self: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the psychological impact of chronic benign low back in pain. Psychology and Health. 2007. 22(5), 517-534.https://doi.10.1080/14768320600941756.

- Brüggemann J. Redefining masculinity—Men’s repair work in the aftermath of prostate cancer treatment. Health Sociology Review: TheJjournal of the Health Section of the Australian Sociological Association, 2021. 30(2), 143–156. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, V.W.L., Skead, C., Wassersug, C.,Richard, J., Palmer-Hague J.L. Impact of Prostate Cancer Treatments on Men’s Understanding of their Masculanity. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 2019. 20(2), 214-225. [CrossRef]

- Charlick M, Murphy M, Murphy B, Ettridge K, O’Callaghan M, Sara S, Jay A, Beckmann K. Sexual wellbeing support for men with prostate cancer: a qualitative study with patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2025.30;14(4):913-927. Epub 2025 Apr 27. PMID: 40376534; PMCID: PMC12076225. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Quotes highlighting damage/loss of masculinity narrated.

Table 1.

Quotes highlighting damage/loss of masculinity narrated.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).