2. From the Angle of Structures

The influence of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators can be discussed from two viewpoints. What substances occur in any particular structure, and in which structures occurs any partcular substance? This main section takes the first viewpoint.

2.1. The Soup

“Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway” (Dubin and Patapoutian 2010). It sounds deceivingly simple: Everything starts with nociceptors and leads up to pain? Indeed, nociception and acute pain start with the activation of nociceptors initiated by an injury to body tissue. However,

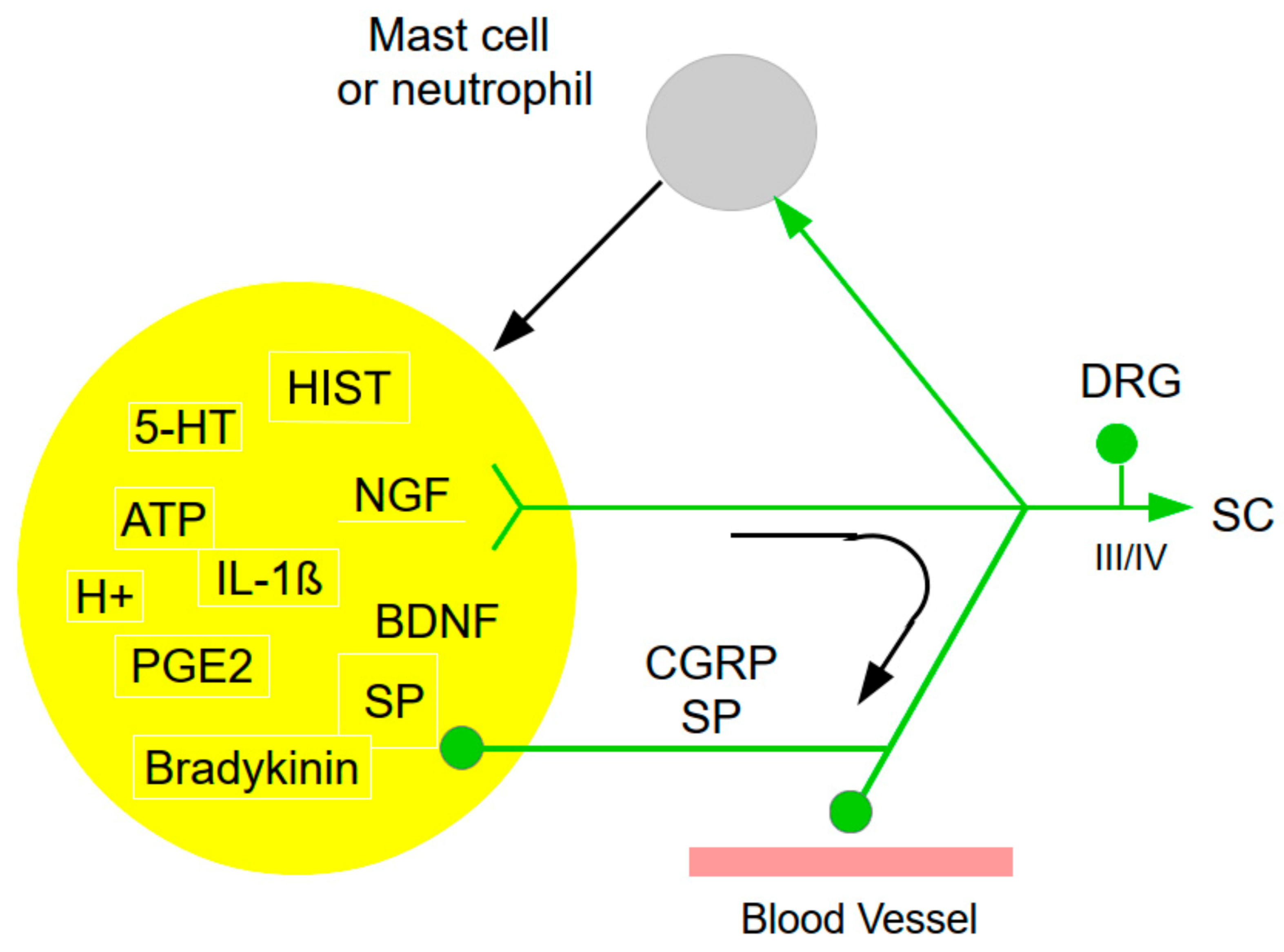

right at this peripheral level, the complexity, too, starts with the sensitization or other modulation, as best illustrated by an inflammation (

Figure 1). Inflammation induces a complex, self-reinforcing sequence of events. As to nociceptor activation and sensitization, there is a close reciprocal cross-talk between the immune system, in particular mast cells, but also other cell types, with nociceptors. In response to injury, nociceptors release various

inflammatory and vaso-active neuropeptides from their terminals (e.g., substance P, SP) that potently activate and recruit immune cells (e.g., mast cells). Iinfiltrated immune cells in turn release plenty of mediators that further promote sensitization of nociceptors by producing cytokines, chemokines, lipid mediators and growth factors,

thus promoting a vicious cycle of mast cell and nociceptor activation, thus promoting neurogenic inflammation and pain/pruritus (Gupta and Harvima 2018; Liu et al. 2021). This ensemle of agents has been dubbed ‘inflammatory soup’ containing a

“A plethora of painful molecules” (Lewin et al. 2004), and their interactions form a complex network.

More specifically, activation of resident mast cells leads to the release of pro-inflammatory chemokines, cytokines, histamine (HIST), proteases, growth factors, lipid mediators, neuropeptides, and reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS). Inflammatory agents so far identified also include protons (H+), prostaglandins, SP, bradykinin (BK), serotonin (5-HT), IL-1, and other endogenous chemicals (Costigan et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2015; Nicol and Vasko 2007; Pezet and McMahon 2006). Some agents induce local degenerative processes, sensitize nociceptors, recruit silent nociceptors, and lead to expression of new receptors and ion channels (Finnerup et al. 2021). Many inflammatory chemicals that excite nociceptors activate intracellular signal transduction pathways and modulate sensory receptor channels and voltage-gated ion channels. Moreover, heat can render cutaneous group III (Aδ) mechanical nociceptors sensitive to heat. Pro-inflammatory influences also spread from the peripheral injury site to the dorsal roots and spinal cord (Moalem and Tracey 2006).

2.2. Sensory Afferents

2.2.1. Nociceptors

Nociceptive primary afferents, despite their morphologically simple appearance, are quite complex. A large assembly of neuromodulators influences nociceptor sensitivity. These agents include corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), vasopressin (AVP), oxytocin (OXT), dopamine (DA), noradrenaline (NA), 5-HT, bradykinin (BK), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), HIST, endocannabinoids, opioids, nerve growth factor (NGF), protons (H+), potassium ions (K+), and others. They contain numerous ligands, e.g., SP, growth factors, hormones such as somatostatin (STT), and neurotransmitters, e.g., glutamate, adenosine, adenosine-trisphosphate (ATP). They express dozens of receptors, along with voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels that contribute to the detection of mechanical, chemical, thermal and/or microbial stimuli, resulting in action potential generation, regulation of discharge patterns, and release of ligand/neurotransmitters that mediate complex interactions between nociceptors (Bourinet et al. 2014; Carlton 2014; Devesa and Ferrer-Montiel 2014; Dubin and Patapoutian 2010; Levine et al. 1993; Sexton et al. 2014; Woolf and Ma 2007). In the rat, various neuropeptides may be co-expressed in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) in varying proportions. For example, GAL-immuno-reactive (GAL-IR) cells are present in the lumbar DRG, and may contain CGRP-, SP- and STT-immuno-reactivity (Yoon et al. 2003).

Nociceptors can be directly or indirectly sensitized, meaning that repeated noxious stimulation or tissue damage elicits prolonged increases in nociceptor afferent excitability, increases in spontaneous activity, decreased threshold for activation, increased and proloned discharge in response to a supra-threhold stimulus. This sensitization contributes to hyperalgesia. Endogenous peptides released at the site of injury or inflammation can sensitize nociceptors directly, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) or NGF; non-peptide substances include PGE2, prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), adenosine, and 5-HT (Levine et al. 1993).

SP is associated with multiple processes: hematopoiesis, wound healing, micro-vasculature permeability, leukocyte trafficking, cell survival and neurogenic inflammation, but possibly also with tumorigenesis and metastasis. Its receptor neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R) is found in the nervous system and in peripheral tissues and is involved in cellular responses such as pain transmission, endocrine and paracrine secretion, vasodilation, and modulation of cell proliferation (Garcia-Recio and Gascón 2015). SP plays a crucial role in pain modulation. Elevated SP concentrations are linked to heightened pain sensitivity (Humes et al. 2024). SP can modulate a variety of ion channels resulting in an increase or decrease of neuronal excitability. SP can enhance the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) channel function leading to greater pain sensitivity. Conversely, during inflammatory processes, inflammatory cells and peripheral nerve terminals release SP, which, in turn, modulates a variety of ion channels rendering sensitization of sensory neurons in an autocrine or paracrine manner. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), SP mainly exists in the small sensory nociceptors. Release of SP can act on NK1R via differential intracellular mechanisms to potentiate the channel activities of vanilloid transient receptor potential channel vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), Nav1.8, and l- and N-type Ca2+ channels in a subset of small-diameter DRG neurons, thereby resulting in hyperalgesia. SP could also decease the activity of low-threshold K+ channel (kv4) in capsaicin-sensitive DRG neurons and thus sensitize the nociceptors (Chang et al. 2019). Tachykinins, co-localized with CGRP in sensory afferents, are involved in viscero-sensitive responses. The role of tachykinins and CGRP was investigated in both nociceptive and viscero-motor responses to inflammation. In inflammation, neurokinin receptors (NK1R and NK2R) mediate the gastric emptying inhibition and visceral pain, respectively. These responses involve a release of CGRP (Julia and Buéno 1997; Levine et al. 1993).

STT [somatotropin release-inhibiting factor (SRIF)] is widely distributed in the body and exerts a variety of hormonal and neural actions. SRIF is important in nociceptive processing because it is localized in a subset of small-diameter DRG cells, activation of SRIF receptors results in inhibition of both nociceptive behaviors in animals and acute and chronic pain in humans, SRIF inhibits dorsal horn (DH) neuronal activity, and SRIF reduces responses of joint mechano-receptors to noxious rotation of the knee joint. Cutaneous nociceptors are under the tonic inhibitory control of SRIF. In a dose-dependent manner, intra-plantar injection of the SRIF receptor antagonist cyclo-somatostatin (c-SOM) resulted in nociceptive behaviors in normal animals and enhancement of nociceptive behaviors in formalin-injected animals. Intra-plantar injection of SRIF antiserum resulted in nociceptive behaviors. Electrophysiological recordings using an in-vitro glabrous skin-nerve preparation showed increased nociceptor activity in response to c-SOM. Parallel behavioral and electrophysiological studies using the opioid antagonist naloxone showed that endogenous opioids do not maintain a tonic inhibitory control over peripheral nociceptors, nor does opioid receptor antagonism influence peripheral SRIF effects on nociceptors. Hence, SRIF receptors maintain a tonic inhibitory control over peripheral nociceptors, and this may contribute to mechanisms that control the excitability of these terminals (Carlton et al. 2001).

HIST can modulate nociceptor sesnsitivity by several mechanisms. In the skin, H3Rs occur on certain group II (Aβ) fibers, and on keratinocytes and Merkel cells, as well as on deep dermal, peptidergic group III (Aδ) fibers terminating on deep dermal blood vessels. Activation of H3Rs on the latter in the skin, heart, lung, and dura mater reduces SP and CGRP release, leading to anti-inflammatory (but not anti-nociceptive) actions. By contrast, activation of H3Rs on the spinal terminals of these sensory fibers reduces nociceptive responses to low-intensity mechanical stimuli and inflammatory stimuli such as formalin (Hough and Rice 2011).

It has been argued that cannabinoid modulation of pain occurs through inhibition at the level of the DRG, thus inhibiting ascending nociceptive signals. Another hypothesis propounds that modulation occurs through activity at the level of the brainstem, inhibiting pain signals through descending suppression of nociceptive signals. However, these effects need not be exclusive. Cannabinoid receptor1 (CB1R) modulates nociceptive processing at the level of the peripheral nervous system, specifically in nociceptors in the DRG. CB1Rs are typically expressed on the terminals of sensory afferent fibers and are found on a large majority of nociceptive neurons in the DRG. These neurons send CB1R out to the peripheral nerve terminals in response to noxious stimuli, further suggesting a mediating role of endogenous cannabinoids and their receptors on nociception. Intra-thecal- injection of anandamide, an endogenous cannabinoid ligand, inhibited group III (Aδ) and group IV (C) fiber neuronal responses to inflammatory pain. Anandamide blocked acute pain (Milligan et al. 2019).

Opioid binding sites are sythesized in the DRG and then transported into the periphery and central terminals of sensory neurons. Local injection of opioids into inflamed tissue reduces the activity of primary afferents, antagonized by naloxone. μ-Receptors appear to exert the most potent analgesia (Levine et al. 1993).

NGF receptor activation and downstream signaling alter nociception through direct sensitization of nociceptors at the site of injury and changes in gene expression in the DGR that collectively increase nociceptive signaling from the periphery to the CNS. NGF is active in both peripheral and central sensitization and has complex multi-functional roles in the modulation of nociceptive processing through effects on the release of inflammatory mediators, nociceptive ion channel/receptor activity, nociceptive gene expression, and local neuronal sprouting effects (Barker et al. 2020; Finnerup et al. 2021; Mizumura and Murase 2015; Nicol and Vasko 2007; Pezet and McMahon 2006), and regulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

During inflammation, injury or certain diseases, inflammatory, immune and Schwann cells release NGF that binds to tropomyosin-related receptor kinase A (TrkA), which in turn directly and rapidly activates and/or sensitizes nociceptors. NGF and its receptor TrkA are retrogradely transported to the DRG, resulting in increased synthesis of neuropeptides (e.g.,: SP, BDNF), receptors, ion channels, and anterograde transport of certain neurotransmitters, receptors and ion channels from the DRG to the periphery tissue and spinal cord. During inflammatory injury, NGF is released from mast cells, but also from other recruited cells. Binding of NGF to TrkA on mast cells causes release of inflammatory mediators, such as HIST, 5-HT, and protons (H+) as well as NGF. Binding of NGF to TrkA on the peptidergic fiber terminal activates intracellular signaling pathways, which results in either increased expression or modulation at the membrane surface of a number of receptors, including, bradykinin receptors (B2R), ion channels, including TRPV1, acid-sensing ion channels (ASIC) 2/3, voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) or Ca2+ (Cav) ion channels, delayed rectifier K+ currents and putative mechano-transducers (Mantyh et al. 2011).

BDNF is synthesized by and released from central terminals of nociceptive afferents and increases the excitability of DH neurons. It is markedly up-regulated in inflammatory conditions in an NGF-dependent fashion, and may play a role as a sensitizing modulator in inflammatory pain states by acting on postsynaptic tropomyosin-related receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptors (Merighi et al. 2008; Pezet and McMahon 2006). Application of BDNF to the adult rat isolated DH with dorsal root attached preparation inhibited the electrically evoked release of SP from sensory neurons. This effect was dose-dependent and reversed by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, K-252a. BDNF-induced inhibition of SP release was blocked by the γ-amino-butyric acid B (GABAB) receptor (GABABR) antagonist CGP 55485 but not by naloxone. Acute application of BDNF significantly increased K+-stimulated release of GABA in the DH isolated in vitro and this effect was blocked by K-252a. Intra-thecal injection of BDNF into the rat lumbar spinal cord induced a short-lasting increase in hindpaw threshold to noxious thermal stimulation that was blocked by CGP 55485. This suggests that exogenous BDNF can indirectly modulate primary sensory neuron synaptic efficacy via facilitation of the release of GABA from DH interneurons (Pezet et al. 2002). BDNF acts specifically as a central modulator, via binding to post-synaptic TrkB receptors, whereupon the BDNF-TrkB complex switches on intracellular protein kinases leading to phosphorylation of NMDARs and facilitated opening. This increases the probability of central sensitization and facilitated transmission through the DH synapse and via third-order neurons to the sensory cortex in the brain (Mantyh et al. 2011).

In the rat DRG, there is a high level of expression of M2 mRNA, and much lower levels of M3 and M4 mRNA were also detected. All three of these sub-types are preferentially localized in medium- and small-sized DRG neurons. These findings suggest the possible involvement of the M2, M3, and M4 sub-types in the modulation of nociceptive transduction (Pan et al. 2007).

2.2.2. Proprioceptors

Acidosis in inflamed tissues is a major risk factor in the development of chronic musculo-skeletal pain. Not surprisingly, nociceptors express pro-nociceptive proton (H+)-sensing ion channels ASICs, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, and two-pore K+ (K2P) channels), which are involved in pain associated with tissue acidosis. Strangely, ASICs are also expressed in non-nociceptors such as proprioceptors. Although non-nociceptive cutaneous afferents could contribute to pain hypersensitivity in chronic pain states, whether non-nociceptive muscle afferents are also involved in pain hypersensitivity of deep tissues is unclear (Lee and Chen 2023). In mice, genetic deletion of ASIC3 in proprioceptors, but not in nociceptors, abolished acid-induced chronic hyperalgesia. Chemo-optogenetically activating proprioceptors resulted in hyperalgesic priming that favored chronic pain induced by acidosis. In humans, intra-muscular acidification induced acid perception but not pain (Lee et al. 2025). Functional interactions between nociceptors and proprioceptors also occur in the spinal cord (below). Equivalent data as for muscle spindle afferents don’t appear to exist for Golgi tendon organ (GTO) afferents.

2.3. Spinal Presynapic Inhibition (PSI)

“In search of lost presynaptic inhibition”

Pablo Rudomin (2009)

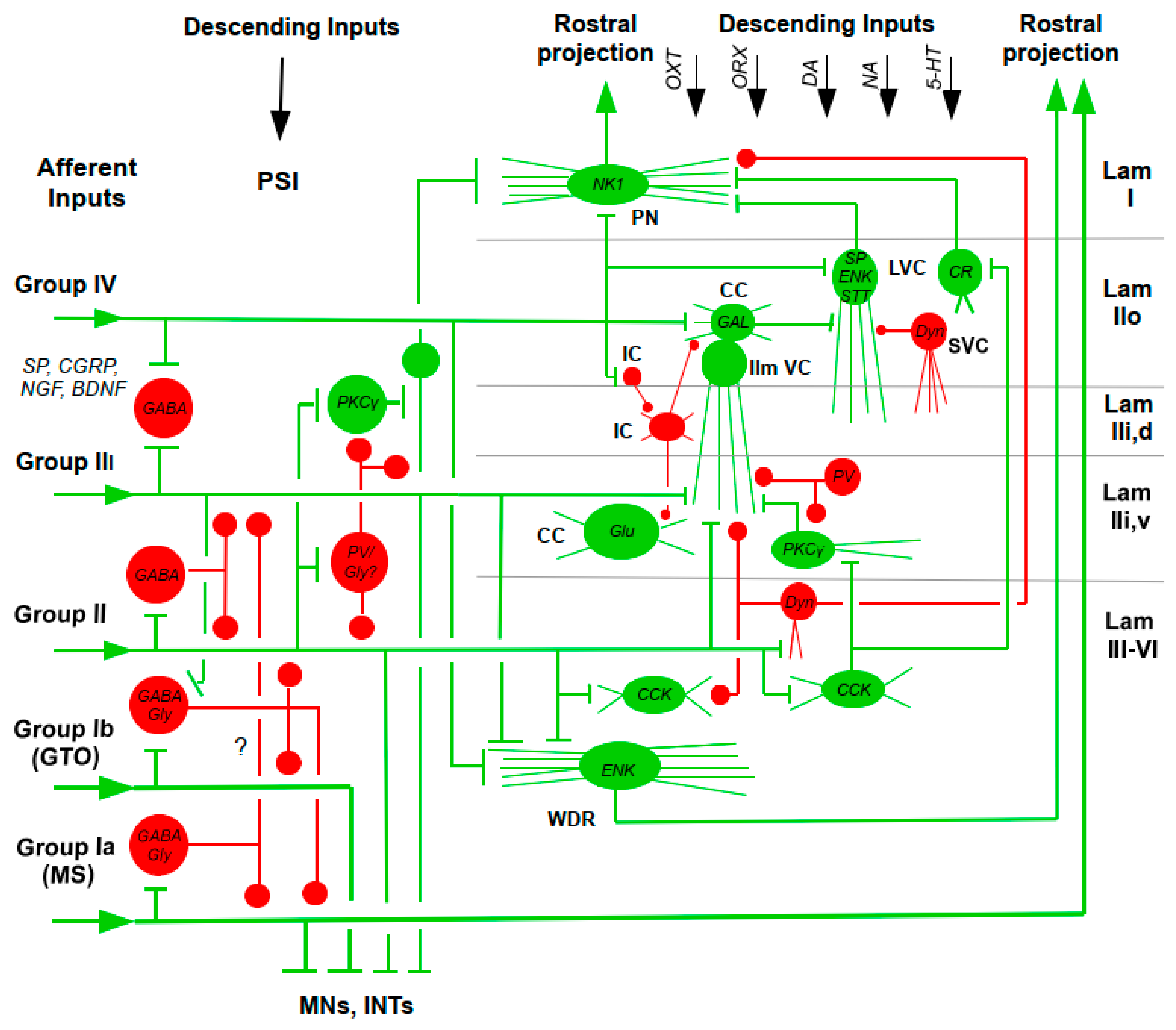

Before even reaching DH neurons, the effects of sensory afferents are modulated by PSI, which acts by decreasing synaptic transmission from presynaptic terminals of sensory afferents to spinal neurons (Comitato and Bardoni 2021; Guo and HU 2014; Hochman et al. 2010; Lu et al. 2018;

Quevedo 2009; Rudomin 2009; Rudomin and Schmidt 1999; Zimmerman et al.

2019; Figure 2). Stimulation of primary sensory afferents generates depolarization of sensory nerve terminals (primary afferent depolarization: PAD), which is electrotonically conducted into the dorsal root and can here be measured as dorsal-root potential (Hochman et al. 2010; Quevedo 2009).

DH inhibitory interneurons are activated by primary sensory nerve fibers and by fiber tracts descending from supraspinal areas. Group II (Aβ), group III (Aδ) and group IV (C) fibers contact dendrites of DH inhibitory neurons. Glycinergic or mixed GABAergic/glycinergic neurons are preferentially targeted by thickly myelinated low-threshold fibers, whereas purely GABAergic neurons are preferentially contacted by thinly myelinated and un-myelinated fibers. This differential innervation is also reflected in the somewhat different distribution of GABAergic and glycinergic cells with glycinergic neurons being concentrated more in the deeper DH layers. GABAergic and glycinergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) could be evoked by innocuous mechanical stimulation, and the majority of GABAergic superficial DH neurons received mono- and polysynaptic excitatory input from group IV and group III afferent nerve fibers. The presence of group IV fiber input in GABAergic neurons does not necessarily imply that these neurons are excited by noxious stimuli. Rather, the group IV fibers that excite islet cells are different from typical nociceptive group IV fibers. These cells might correspond to a particular sub-class of group IV fibers with a low activation threshold, which suggest that these fibers convey pleasant touch sensations (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

Some gross functional input-output patterns in the cat hindlimb are as follows. Group Ia afferents from primary muscle spindle endings of both flexor and extensor muscles are inhibited presynaptically by group Ia and group Ib afferents from Golgi tendon organs (GTOs) in flexor nerves, while group Ib afferents are inhibited only by group Ib inputs from both flexor and extensor muscles and from joint and large cutaneous afferents but may also be inhibited by these cutaneous afferents. PAD of group II afferents is elicited by activation of group II, cutaneous, joint and pudendal afferents. PAD of low-threshold cutaneous afferents is evoked by activation of low-threshold cutaneous, group Ib, group II afferents and high-threshold muscle afferents. High-threshold cutaneous (groups III/IV) afferents are depolarized by noxious stimulation (Quevedo 2009: Rudomin and Schmidt 1999).

The PSI from and to group III/IV afferents is still not fully explored. First, there could be PSI elicited by MS afferents onto nociceptive afferents. In the cat, a group of superficial DH neurons that responded to noxious pinch of the gastrocnemius muscles (GSs) responded to bradykinin injections into GS with three types of responses: excitatory, inhibitory and mixed. The majority of the neurons with excitatory and mixed responses to bradykinin were also influenced by stretches of the GS applied directly after the bradykinin injection. In these neurons, the GS stretch usually counteracted the bradykinin-induced response, i.e., shortening and reducing bradykinin-induced excitation and re-exciting the cells after bradykinin-induced inhibition. At least the inhibitory effect could hypothetically have been effected by PSI from muscle stretch receptors onto nociceptive afferent terminals (

Figure 2, lower left; Björklund et al. 2004). Conversely, afferent group III/IV input, probably excited by GS muscle-fatigue, enhanced PSI elicited from antagonist muscle nerves (Kalezic et al. 2004). In addition to the classic PSI in which low-threshold cutaneous afferents evoke a GABA

A-receptor-dependent form of PSI that inhibits similar afferent sub-types, another mechanism involves small-diameter afferents, which predominantly evoke an NMDAR-dependent form of PSI that inhibits large-diameter fibers. Behaviorally, loss of either GABA

A receptors (GABA

ARs) or NMDARs in primary afferents leads to tactile hypersensitivity across skin types, and loss of GABA

ARs, but not NMDARs, leads to impaired texture discrimination (Zimmerman et al. 2019). In rodents, non-GABA interneurons have been described that could be involved in pre- and postsynaptic inhibition of small-diameter nociceptive afferents. This population of deep layer DH (dDH) inhibitory interneurons express the receptor tyrosine kinase Ret neonatally. The early RET+ dDH neurons receive excitatory as well as polysynaptic inhibitory inputs from touch- and/or pain-sensing afferents. Conversely, they negatively regulate DH pain and touch pathways through both pre- and postsynaptic inhibition. Specific ablation of early RET+ dDH neurons increases basal and chronic pain, whereas their acute activation reduces basal pain perception and relieves inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Cui et al. 2016).

PSI is also subject to influences from spinally descending pathways, which modulate its strength and probably distribution in a task- and context-dependent way. The synaptic efficacy of spindle group Ia and II, GTO group Ib and cutaneous afferents is differentially altered by signals descending in cortico-spinal, rubro-spinal, reticulo-spinal and vestibulo-spinal tracts, as well as by raphé-spinal 5-HT and LC-spinal NA systems (Quevedo 2009; Rudomin 2009; Rudomin and Schmidt 1999). Moreover, supraspinal sites send Adr, NA and 5-HT fibers to the DH (Figure 4). Both NA and 5-HT have specific effects on defined DH neuron populations. In addition to inhibiting excitatory neurons and terminals, NA and 5-HT fibers excite GABAergic and glycinergic interneurons. In addition to 5-HT and NA fibers, a great number of descending GABAergic and glycinergic fibers innervate the DH. A direct inhibitory innervation (i.e., via monosynaptic connections) of DH neurons from the RVM has been demonstrated using in vivo patch-clamp recordings and was confirmed by morphological evidence. The glycinergic innervation is also evident in reporter mice expressing EGFP in glycinergic neurons. In the spinal cord, descending GABAergic and glycinergic projections mainly target presumed excitatory neurons (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

Based on dorsal root potential (DRP) latency measurements, it had originally been thought that PAD of low-threshold sensory afferents would be mediated by minimally tri-snaptic pathways with pharmacologically identified GABAergic interneurons forming last-order axo-axonic synapses onto afferent terminals. However, it has been argued that there is still no decisive evidence of this organization. This would leave open the possibility of the existence of PAD generated by more direct pathways with a more complex pharmacology than exclusively GABA and GABAARs.

Morphological, physiological and pharmacological data argue for a participation of GABA in PAD. PSI is exerted either in form of rather simple axo-axonic synapses mainly in the case of group II (Aβ) fiber terminals, or in form of complex synaptic arrangements called synaptic gluomeruli. These glomeruli are located in the superficial DH and comprise interneuron axon terminals and postsynaptic dendrites that surround the central primary afferent fiber terminal. The vast majority of glomeruli contain peripheral axons that originate from GABAergic interneurons while the dendrites postsynaptic to the central axon belong to glutamatergic excitatory neurons (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

Activation of GABAAR on primary sensory neurons induces PAD rather than hyperpolarization. Under certain conditions, glutamate and K+ also contribute to PAD but the GABAergic (bicuculline-sensitive) component usually dominates. PAD inhibits rather than facilitates transmitter release from the primary afferent terminal. Different explanations have been proposed for this phenomenon. PAD may lead to the inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels on primary afferent terminals and may thus reduce presynaptic Ca2+ influx and transmitter release. Alternatively, it may interfere with action potential propagation into the terminal through either voltage-dependent inactivation of Na+ channels or through activation of a shunting conductance (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

In the case of most primary nociceptor terminals, especially for peptidergic nociceptors, morphological evidence for a relevant GABAergic innervation is much weaker. Whether or not PSI by GABAergic interneurons is relevant for nociceptive transmission is controversial. Physiological experiments have demonstrated the presence of dorsal root reflexes in capsaicin-sensitive primary afferent axons and the blockade by intra-thecal bicuculline of peripheral flare responses, which depend on the release of CGRP from the peripheral terminals of peptidergic nociceptors (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

A classic role in PSI has played GABA in regulating nociceptive signal strength and separating nociception from touch signals. Intra-thecal application of bicuculline and strychnine (antagonists of GABAA and glycine receptors, respectively) increased responses to noxious stimuli. Presynaptic GABA receptors located on sensory afferent terminals are involved in gating both tactile and noxious stimuli in the DH. GABA receptors of the A and B type are expressed on both nociceptive and non-nociceptive sensory afferents, where axo-axonic synapses exist. GABAARs are ligand-gated ion channels, most commonly formed by 2α, 2β, and 1γ sub-units. Group IV fibers express the α2, α3, and α5 sub-units, while α1, α2, α3, and α5 are present on myelinated A fiber terminals. The sub-unit β3 is the dominant β sub-unit expressed in DRG neurons of both A and C type (Comitato and Bardoni 2021).

In addition to GABAA, activation of GABAB receptors (GABABRs), expressed on nociceptive and non-nociceptive primary afferent terminals, also contributes to presynaptic inhibition, exerting analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic effects. The GABAB1 isoforms 1a and 1b, together with the sub-unit GABAB2, occur in small and large DRG neurons and in the spinal cord, both on primary afferent terminals and on DH neurons. Endogenous or exogenous activation of GABABRs in superficial DH causes both pre- and postsynaptic effects. In rats, activation of presynaptic GABABRs inhibited pinch- and touch-evoked synaptic responses in vivo and decreased glutamate and peptide release from group III-IV primary afferents and DH neurons. The inhibitory effect of GABABRs on transmitter release is due to the concurrent inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and release machinery downstream of Ca2+ entry into the nerve terminals. The block of GABABRs increased the first excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) in a train of four stimuli, recorded from lamina III–IV neurons. This suggests that, differently from GABAARs, which require the release of GABA through synaptic activation, GABABRs are tonically activated, confirming the finding of a previous study performed in lamina II (Comitato and Bardoni 2021).

When occurring in nociceptor terminals, PAD and PSI should reduce pain. In fact, part of the anti-hyperalgesic action of intra-thecally injected diazepam occurs through an enhancement of as demonstrated in experiments using the sns-α2-deficient mice. However, in nociceptors, PAD cannot only cause PSI, but may under certain conditions also give rise to so-called dorsal root reflexes. These are action potentials elicited in primary sensory fiber terminals by stimulation of a second afferent fiber via an interconnected GABAergic interneuron. They occur when PAD reaches the threshold of action potentials. These action potentials may then propagate both in an orthodromic (central) and antidromic (centrifugal) direction. The centrally propagating action potential is thought to reinforce pain sensation, while the peripheral action potential, in case of peptidergic nociceptors, contributes to neurogenic inflammation, vasodilatation and plasma extravasation through the release of CGRP and SP (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

However, the circumstances are a bit more complicated than instigated by the tri-synaptic GABAergic circuit. (i) Primary sensory afferents may co-release substances acting on receptors with GABAA pharmacology. (ii) Apart from GABAARs, primary sensory afferents contain more receptors that can contzribute to terminal depolarization. Activation of high-threshold afferents evokes DRP, by substances including AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptors. Activation of presynaptic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (AMPARs) depresses exitatory transmission in DH neurons. Capsaicin depresses excitatory transmission elicited by group IV afferents. (iIi) PSI may be not related to PAD. Activation of GABAB receptors inhibits Ca2+ channels without presynaptic depolarization and produces a longer-lasing component of inhibition of monosynaptic EPSPs. Activation of adenosine and cannabinoid receptors inhibits transmiitter release by inhibiting Ca2+ channels. (iv) GABA receptors on presynaptic sensory terminals contain bicuculline/picrotoxin-sensitive glycine, nicotinic ACh receptor (nAChR) or 5-HT receptor sub-units. (v) DH lamina III, projection area of group II and III cutaneous afferents, contains cholinergic (ACh) interneurons that receive inputs from myelinated and un-myelinated cutaneous afferents, which thus could feedback onto the same afferents. (vi) Many sensory afferents co-release ACh, taurine or ß-alanine that might activate GABAARs (Hochmann et al. 2010; Quevedo 2009).

In the absence of a direct innervation by axo-axonic synapses of the majority of primary nociceptors, GABA could still act as a volume transmitter. In this case, GABAARs along the intraspinal segment of the primary afferent axon could be activated by ambient GABA to cause voltage-dependent inactivation of Na+ channels or activation of a shunting conductance. Both would prevent the invasion of the presynaptic terminal by axonal action potentials. Direct experimental proof for either of these possibilities is lacking, in part due to the intrinsic difficulties associated with recording from spinal primary afferent axon terminals (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

Although the network scheme depicted in

Figure 2 is immensely complex, it is incomplete. Currently, much work is being done to complete it. This work is mostly performed in rodents and continuously adds new details, in terms of circuit motifs and neuromodulators.

In the context of the role of PSI in pain, the emhpasis has been on the interaction between cutaneous non-nociceptive group II afferents and nociceptive group III and IV afferents (e.g., Comitato and Bardoni 2021; Guo and Hu 2014; Hochman et al. 2010; Lu et al. 2018; Zimmerman et al. 2019).

The network scheme in

Figure 2 is a step forward by integrating effects of group Ia and Ib afferents from muscle spindles (MSs) and Golgi tendon organs (GTOs), respectively. The immediate problem arising is that group II afferents must be split into a sub-group arising from the skin and a sub-group originating in skeletal muscles, the latter group containing a sub-sub-group from muscle spindles and the rest. To our knowledge, not all the new possibilities of interaction with PSI have been explored. This would indeed be worthwhile studying because cutaneous pain is not separated from muscle pain nor from movement.

The most serious challenge is of course to understand the operation of this network under natural conditions. Quite a few attempts have been made in humans (e.g., Nielsen 2016) and animals (e.g., Côté et al. 2018) to monitor PSI opeation during rest, stance, (fictive) locomotion and voluntary movements (Dibaj and Windhorst 2024a; Windhorst 2007, 2021; Windhorst and Dibaj 2023). The power of PSI changes in these different conditions, the addional influence of pain remaining under-studied, although pain does of course have an effect on movement. An example is that, in the (resting) cat, afferent group III/IV input, probably excited by gastrocnemius muscle-fatigue, enhanced PSI elicited from antagonist muscle nerves (Kalezic et al. 2004). Finally, however, it will be impossible to interpret the role of the network in

Figure 2 in the context of natural behaviors.

2.4. Spinal Cord

The intensely investigated spinal DH networks exhibit a picture of mind-boggling complexity (

Figure 2). DH neurons receive sensory information from multi-modal primary afferents that innervate the skin and deeper tissues of the body and that respond to specific types of noxious and non-noxious stimuli. Small-diameter afferents contact a large variety of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons that provide for complex signal processing at spinal levels, and also connect with a minority of projection neurons that send axons rostrally. Moreover, descending fiber systems impinge on spinal neurons (Dibaj et al. 2024; Nadrigny et al. 2017).

As can be expected from a structure intimately involved in the modulation of nociceptive transmission, the spinal DH contains a plethora of neurotransmitters/neuromodulator, conveyed by the input fibers or expressed by the intrinsic spinal neurons themselves: CCK, CRH, STT, CGRP, GAL, [tachykinins: SP, neurokinin-A (NK-A), neurokinin-B (NK-B)], NT, neuropeptide Y (NPY),

thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH); vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), catecholamines (DA, NA, adrenaline), 5-HT, opioids (ENKs, ß-endorphin, Dyn), [neurotrophins: NGF, BDNF, glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)]; ACh, excitatory (glutamate) or inhibitory (GABA, glycine) amino acids; purines; nitric oxide (NO); TRP channels; capsaicin; and nociceptin, and others (Blumenkopf 1988; Fürst 1999; Merighi 2018, 2024; Merighi et al. 2008; Todd and Spike 1993; West et al. 2015; Zeilhofer et al. 2021). A limited collection of these modulators in shown in the simplified scheme of

Figure 2.

WDRs have been investigated in view of their inputs from cutaneous mechano-receptors and nociceptors. It should be noted that some cutaneous mechano-receptors respond to skin stretch, thus allowíng their afferents to react to joint position and/or movements (Edin and Abbs 1991). This establishes a link between motor and nociceptive systems.

Corticosteroids have been used as a supplementary treatment in acute inflammatory pain conditions, but there appears to be a more direct role that steroids play in the generation and clinical management of chronic pain. The end-product of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cortisone, modulates nociceptive transmission at spinal level. In laminae and II, noxious stimulation releases SP and CGRP, and with their expression co-exists a high density of glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). Termination of treatment with cortisone after four weeks leads to loss of an anti-nociceptive effect (McEwen and Kalia 2010). SVC: small vertical cell; WDR: wide-dynamic range neuron (Data from Merighi 2018; Todd and Spike 1993; West et al. 2015; Zeilhofer et al. 2021).

In rats, DA inhibited the nociceptive group III- and group IV-fiber synaptic inputs to lamina I projection neurons via presynaptic actions. Similar inhibitory effects of DA on EPSCs occurred in rats subjected to complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) to induce peripheral inflammation (Lu et al. 2018). Regulation of the threshold of synaptic plasticity may determine the proneness to sensitization and hyper-responsiveness to noxious inputs. Increasing the endogenous DA levels in the DH by using re-uptake inhibitor GBR 12935 induced hyper-DA transmission. Conditioning low-frequency (1 Hz) stimulation of the sciatic nerve induced long-term potentiation (LTP) of group IV-fiber-evoked potentials in DH neurons. The magnitude of LTP was attenuated by blockade of either DA D1-like receptors or an NMDAR sub-unit (Buesa et al. 2016). In the spinal cord and striatum, anti-nociception of DA is mainly mediated by D2-like receptors, while in the nucleus accumbens (Nac) and peri-aqueductal gray (PAG), both D1- and D2-like receptors are involved as analgesic targets (Wang et al. 2021).

In the DH, NA suppresses nociceptive signal transmission via several mechanisms, including inhibitory action by α2A-adrenoceptors on central terminals of primary nociceptors (PSI), by direct α2-adrenergic action on nociceptive relay neurons (postsynaptic inhibition), and by α1-adrenoceptor-mediated activation of inhibitory interneurons. Furthermore, α2C-adrenoceptors on axon terminals of excitatory interneurons possibly contribute to spinal control of pain (Pertovaara 2006; Yoshimura and Furue 2006). The end-product of the HPA, cortisone, modulates nociceptive transmission at spinal level. In laminae and II, nociceptive stimulation releases SP and CGRP, and with their expression co-exists a high density of GRs. Termination of treatment with cortisone after four weeks leads to loss of an anti-nociceptive effect (McEwen and Kalia 2010).

The median nucleus raphé magnus (NRM) neurons project preferentially into the deep laminae V-VI of the DH, whereas the lateral nucleus paragiganto-cellularis (PG) neurons send projections exclusively into the superficial laminae I-II. These differential projection patterns support the notion that 5-HT neurons might be differently implicated in pain modulations depending on their location in the NRM vs. PG. The majority of 5-HT fibers form non-synaptic varicosities in the vicinity of DH neurons and astrocytes, suggesting that most 5-HT transmission occurs through volume transmission (Bardoni 2019).

The 5-HT pathways descending to the DH exert inhibitory or facilitatory influences on the spinal processing of nociceptive information, depending on acute or chronic pain states and the type of receptor acted upon. To date, more than a dozen types of 5-HT receptors (5-HTRs) have been identified. Most of them are expressed on nociceptors and/or DH neurons in the rodent and human spinal cord. The roles of the different receptor sub-types in pain neurotransmission are not completely known. Due to this diversity, 5-HT can exert both pro-nociceptive and analgesic effects by activating specific types of 5-HTRs, in different pain conditions. Group III and group IV nociceptive fibers express several 5-HTRs on their presynaptic terminals. Activation of the presynaptic 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D and 5-HT7 receptors tends to be anti-nociceptive, producing a decrease of glutamate release. The 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptor tend to promote nociception. The ionotropic 5-HT3Rs are involved in PAD as a sign of PSI, and their effect on glutamate release could be variable. It has also been reported that 5-HTRs play an active role in mediating synaptic plasticity the DH (Bardoni 2019; Cortes-Altamirano et al. 2018; Ossipov et al. 2014). Equally varied and ill-understood are the pain-modulatory effects of 5-HT1, 5-HT2, 5-HT3 and 5-HT7 receptors above the spinal cord, this modulation depending on the type and distribution of the receptors (Cortes-Altamirano et al. 2018).

Primary nociceptive afferents use glutamate as their principal fast neurotransmitter. However, peptides have an influential role in both mediating and modulating sensory transmission. SP is concentrated in laminae I and II, and one of its receptors, NK1R, is present in the same laminae and the medial half of laminae III-X.

Noxious stimuli elicit the release of SP and neurokinin A (NKA). In the DH, SP, acting on NK1R, and NKA, acting on NK2 receptors, excite nociceptive DH neurons, this release causing a late slow depolarization in DH second-order neurons. A sub-population of DH neurons is however inhibited by SP, this effect probably being indirect via excitation of an interposed inhibitory interneuron. This anti-nociceptive effect may be due to an SP-induced release of opioid peptides from DH interneurons. In vivo, SP potentiated NMDA-induced responses of spino-thalamic tract (STTr) cells, and in vitro, SP potentiated an inward glutamate-gated current, which contributes to the wind-up property, i.e., repeated activation of primary nociceptive afferents results in a progressive increase of firing of DH nociceptive neurons to each stimulus (Levine et al. 1993).

CGRP is a neuromodulator, having limited effects on its own, but strongly potentiating the effects of other substances, in particular SP. Unlike SP, CGRP has limited distribution in the spinal cord, CGRP terminals being concentrated in DH laminae I and II and in the reticulated area of lamina V. CGRP terminals make direct connections with second-order STTr neurons. Noxious thermal, mechanical or electrical stimulation elicited the release of CGRP in the superficial DH. In vivo, iontophoretically administered CGRP produced slow, long-lasting excitation of DH cells. In vitro, CGRP produced a slow depolarization in DH cells, probably by increasing the Ca2+ conductance. Like SP, CGRP can regulate the release of amino acids. In vivo in rats, concentrations of CGRP that alone had little effect strongly potentiated the excitatory action of SP or of noxious stimulation (Levine et al. 1993).

Different acute pain states and itch transmitted via the TRPV1 population may have differential effects becoming apparent when either ablating Trpv1-Cre-expressing neurons or inducing vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2) deficiency in Trpv1-Cre-expressing neurons. Furthermore, in Vglut2-deficient mice, pharmacological inhibition of SP or CGRP signaling was used to evaluate the contribution of SP or CGRP to these sensory modulations, with or without the presence of VGLUT2-mediated glutamatergic transmission in Trpv1-Cre neurons. Together with c-fos analyses, these data showed that glutamate via VGLUT2 in the Trpv1-Cre population together with SP mediate acute cold pain, whereas glutamate together with CGRP mediate noxious heat. Moreover, glutamate together with both SP and CGRP mediated tissue-injury-associated pain. Furthermore, itch, regulated by the VGLUT2-mediated transmission via the Trpv1-Cre population, depended on CGRP and gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) transmission because pharmacological blockade of the CGRP or GRPR pathway, or genetic ablation of Grpr, led to a drastically attenuated itch. Hence, different neurotransmitters combined can cooperate with each other to transmit or regulate various acute sensations, including itch (Rogoz et al. 2014).

In some species, CCK is co-localized with SP and/or CGRP. CCK immuno-reactivity also occurs in DH neurons and terminals of descending axons. In rats, CCK iontophoresis excited DH neuons, but weakly and inconsistently. However, CCK antagonized and CCK antagonists potentiated opioid suppression of group IV (C) fiber activation of DH cells (Levine et al. 1993).

In the spinal DH, STT-containing neurons are predominantly localized in laminae I, II and III. About 13% of lamina I and 15% of lamina II neurons express STTR2a receptors. This provides the cellular and molecular basis for the role of STT in the modulation of pain transmission (Pan et al. 2007; Rosen and Schulkin 2022). Pharmacological studies supported either a facilitatory or an inhibitory role for STT in nociception (Levine et al. 1993).

Intra-thecal injection of STT could increase the nociceptive threshold. Intra-plantar injection of the STT analogue octreotide reduced formalin-induced nociceptive behaviors and the responses of group IV (C) fibers to noxious stimulation. Intra-plantar injection of SCR007, a selective non-peptide SSTR2 agonist, significantly increased the nociceptive threshold. STT has been effective in the treatment of patients with certain pain conditions, including cluster headache, headache associated with pituitary tumors, and postoperative pain. Spinal administration STT or octreotide reduced pain in patients with terminal cancer (Pan et al. 2007).

In anesthetized cats, the effects of STT were investigated on nociceptive responses of rostrally projecting DH neurons to different kinds of noxious stimuli (i.e., heat, mechanical and cold stimuli) and to group III and group IV fiber activation of the sciatic nerve. Iontophoretically applied STT suppressed the responses of DH neurons to noxious heat and mechanical stimuli as well as to group IV-fiber activation (Pan et al. 2007). In vitro experiments showed that the STT-induced inhibition of DH cells went along with a hyperpolarization (Levine et al. 1993).

STT also suppressed glutamate-evoked activities of DH neurons. The effects of STT were blocked by the STT receptor antagonist cyclo-STT. This suggests that STT has a dual effect on the activities of DH neurons: facilitation and inhibition, depending on the modality of pain signaled through them and its action site (Jung et al. 2008).

However, STT has also been reported to enhance the responses of DH neurons to noxious cold stimuli and group III-fiber activation (Jung et al. 2008).

Pain information processing in the spinal cord has been postulated to rely on nociceptive transmission (WDR) neurons receiving inputs from nociceptors and group II (Aβ) mechano-receptors, with group II inputs gated through feed-forward activation of spinal inhibitory neurons. Intersectional genetic manipulations were used to identify these critical components of pain transduction. Marking and ablating six populations of spinal excitatory and inhibitory neurons, associated with behavioral and electrophysiological analysis, showed that excitatory neurons expressing STT include WDR-type cells, whose ablation caused loss of mechanical pain. Cells marked by the expression of dynorphin (Dyn) represent inhibitory interneurons, which are necessary to gate group II fibers from activating STT neurons to evoke pain. Hence, peripheral mechanical nociceptors and group II mechano-receptors, together with spinal STT excitatory and Dyn inhibitory neurons, form a micro-circuit that transmits and gates mechanical pain (Duan et al. 2014).

Itch-eliciting stimuli are detected by sensory neurons that innervate the skin. The neuronal pathways for spinal itch neurotransmission was investigated, particularly the contribution of STT. In the periphery, STT was exclusively co-expressed with the neuropeptide natriuretic polypeptide B (Nppb+) in DRG neurons. STT potentiated itch by inhibiting inhibitory Dyn neurons. Elimination of STT from primary afferents and/or from spinal interneurons demonstrated differential involvement of the peptide released from these sources in itch and pain. This defined the neural circuit underlying STT-induced itch and characterized a contrasting anti-nociceptive role for the peptide (Huang et al. 2018).

In many nociceptive, capsaicin-sensitive group IV afferents, GAL co-localizes with SP and CGRP. In thermal nociception, intra-thecal GAL application had an anti-nociceptive effect, although, in mechanical tests at higher doses, it lowered the threshold for vocalization. However, low doses of intra-thecal GAL increased the excitability of the flexion reflex, while at higher doses, it produced a long depression of thermal nociceptive reflexes. The higher doses also blocked the facilitatory effect of SP, CGRP or of the conditioning stimulation of group IV fibers. Thus, like SP, GAL seems to have both pro- and anti-nociceptive effects (Levine et al. 1993).

The endocannabinoid (EC) system consists of two main receptors: cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors exist in both the CNS and periphery, whereas the cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptor occurs principally in the immune system and to a lesser extent in the CNS. The EC family consists of two classes of ligands; the N-acyl ethanolamines, such as N-arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide (AEA), and the monoacylglycerols, such as 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. Much work has studied the role of EC in nociceptive processing and the potential of targeting the EC system to produce analgesia. Cannabinoid receptors and ligands are present at almost every level of the pain pathway from peripheral sites, such as peripheral nerves and immune cells, to central integration sites such as the spinal cord, and higher brain regions such as the PAG and the rostral ventro-lateral medulla (RVL) associated with descending control of pain. The EC has been shown to induce analgesia in preclinical models of acute nociception and chronic pain states (Burston and Woodhams 2014).

It has been argued that cannabinoid modulation of pain occurs through inhibition at the level of the DRG, thus inhibiting ascending nociceptive signals. Another hypothesis propounds that modulation occurs through activity at the level of the brainstem, inhibiting pain signals through descending suppression of nociceptive signals. However, these effects need not be exclusive (Milligan et al. 2019).

Many glutamatergic sensory afferents and DH GABAergic interneurons express CB1. It is purported that eCBs are produced after stimulation of glutamatergic nociceptive, small- and medium-diameter group C fibers and activate CB1 receptors expressed on inhibitory interneurons within the DH. This reduces GABAergic signaling and increases nociceptor excitability leading to maladaptive nociception. A small population of astrocytes in the spinal cord express CB1 receptors and activation of these astrocytic receptors leads to transient Ca2+ currents that stimulate the production of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), a potent endogenous CB1 agonist. This would suggest that CB1 receptors expressed in the DH are responsible for mediating the effects of chronic, neuropathic pain (Milligan et al. 2019).

The DH is a major target for opioids such as analgesic drugs, and the effects of exogenous (mainly morphine) and endogenous opioids on the release of neuropeptides, in particular SP and CGRP, and the inhibition of DH neurons. Opioids directly applied to the spinal cord suppress behavioral responses to noxious stimuli in animals and produce deep anti-nociception in humans. The central terminals of nociceptive afferents contain μ-, δ- and κ-opioid binding sites. Opioids have a direct effect on primary afferents; in particular, they inhibit K+-induced SP release. However, the effects may depend on receptor type. For example, in rat DH slices, selective δ-ligands reduced capsaicin-induced SP release, but μ-selective ligands had no such effect. Opioids also diminish K+- and capsaicin-induced release of CGRP (Levine et al. 1993).

Complex modulations by opioids occurred in the in vitro (from tissue slices) and in vivo rat preparation whose intra-thecal space was perfused with an artificial cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) release of SP and CGRP, depending on the opioid receptor (μ, δ, κ, and their sub-types) stimulated by these compounds. The inhibition by δ agonists of SP release from primary afferent fibers, and that by the concomitant stimulation of μ receptors of the release of CGRP are probably involved in the analgesic action of specific opioids and morphine at the level of the spinal cord. The negative modulation (through presynaptic opioid auto-receptors) by δ and μ agonists of the spinal release of met-enkephalin (M-ENK), and the complex inhibitory/excitatory influence of δ, μ and κ receptor ligands on the release of CCK within the DH very likely also contribute to the anti-nociceptive action of these drugs and morphine (Bourgoin et al. 1994).

Cellular interactions between μ- and δ-opioid receptors, including heteromerization, are thought to regulate opioid analgesia. μ- and δ-opioid receptor co-expression is limited to small populations of excitatory interneurons and projection neurons and unexpectedly predominates in ventral horn (VH) motor circuits. Similarly, μ- and δ-opioid receptor co-expression is rare in cortical brain regions, AMY, and parabrachial nucleus (PBN) processing nociceptive information. In the discrete μ- and δ-opioid receptor co-expressing nociceptive neurons, the two receptors internalize and function independently. Conditional knockout experiments revealed that δ-opioid receptors selectively regulate mechanical pain by controlling the excitability of STT-positive DH interneurons. This illuminates the functional organization of δ-opioid receptors and μ- opioid receptor in CNS pain circuits (Wang et al. 2018).

In spinal cord slices, presynaptically acting M-ENK can inhibit glutaminergic input to DH cells in lamina I (Levine et al. 1993).

NGF has a role in both acute, transient nociceptive responses, and in longer-term, chronic pain. NGF belongs to a family of small glycoproteins that also include neurotrophin 3 (NT-3), neurotrophin 4/5 (NT-4/5) and BNDF (below). It is crucial for survival of nociceptive neurons during development, but also plays an important role in nociceptive functions in adults and in the development and modulation of persistent pain. NGF binds to TrkA, whereupon the NGF-TrkA complex is internalized and transported from peripheral terminals to sensory cell bodies in the DRG (Mantyh et al. 2011).

NGF is active in both peripheral and central sensitization and has complex multi-functional roles in the modulation of nociceptive processing through effects on the release of inflammatory mediators, nociceptive ion channel and receptor activity, nociceptive gene expression, and local neuronal sprouting effects (Barker et al. 2020; Boyce and Mendell 2014; Finnerup et al. 2021; Mantyh et al. 2011; Mizumura and Murase 2015; Nicol and Vasko 2007; Pezet and McMahon 2006; Yang and Chang 2019).

Longer-term (days) post-translational effects of NGF-TrkA binding and transport to the DRG include an increase in the concentration of peptides (e.g., SP, CGRP, and BDNF) in DH terminals of peptidergic (TrkA+) primary afferent neurons. Release of these peptides, in addition to glutamate acting on AMPARs, on subsequent stimulation of peptidergic (TrkA+) primary afferent neurons, and binding to their respective receptors (SP to NK1; CGRP to CGRP-R, BDNF to TrkB) may cause strong depolarization of the post-synaptic second-order projection neuron, changes in transcriptional activity in the second order projection neuron (e.g., increased expression of c-fos), and ultimately removal of the Mg2+ block of the glutamatergic NMDAR. BDNF acts specifically as a central modulator, via binding to post-synaptic TrkB receptors, whereupon the BDNF-TrkB complex switches on intracellular protein kinases leading to phosphorylation of NMDARs and facilitated opening. This increases the probability of central sensitization and facilitated transmission through the dorsal horn synapse and via third-order neurons to the sensory cortex in the brain (Mantyh et al. 2011).

NGF is important in inflammatory pain as exemplified by the expression and/or release of NGF by certain inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, lymphocytes, macrophages and mast cells (Kaur et al. 2017; Luo et al. 2015), as a consequence of injury. NGF is also up-regulated in experimental models of inflammation, including those induced by carrageenan, formalin, and CFA. Cutaneous administration of NGF to rodents and to humans causes hyperalgesia within one or three hours, respectively, suggesting that NGF leads to a relatively rapid sensitization of cutaneous nociceptors. These rapid effects in the rat are thought to be mediated primarily through NGF binding with TrkA expressed on mast cells, causing de-granulation and release of a variety of algogenic mediators, such as hydrogen ions (H+), HIST, prostaglandin E2, 5-HT, and bradykinin, as well as additional NGF (Mantyh et al. 2011). NGF plays a central role in initiating and sustaining heat and mechanical hyperalgesia following inflammation. Secreted proforms of nerve NGF (proNT) have biological functions distinct from the processed mature factors raising the possibility that these pro-neurotrophins may have distinct function in painful conditions. ProNTs engage a novel receptor system that may function with or independently of the classic Trk system in regulating inflammatory or neuropathic pain (Lewin and Nykjaer 2014).

NGF may also generate and maintain hypersensitivity by inducing aberrant sprouting and/or neuroma formation in response to tissue and/or nerve injury. Local administration of NGF to normal peripheral nerves can also induce nerve sprouting of peptidergic (TrkA+) nociceptors (Mantyh et al. 2011).

IL-6 is another neurotrophic factor and an important mediator in pain processing. Following nerve injury, IL-6 is released and its concentrations are increased. IL-6 is involved in the development of pain and CNS sensitization. It promotes and mediates various inflammatory pain conditions (Yang and Chang 2019).

BDNF plays important roles in proper growth, neuronal differentiation, development, survival, neuroprotection, neurodegeneration, development and plasticity of glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses, synaptic plasticity, and the control of mood disorders (Merighi 2024). Mature neurotrophin binding to the high-affinity receptor, TrkB receptor, increases cell survival and differentiation, dendritic spine complexity, re-sculptering of neuronal networks, and LTP. Deployment of TrkB receptors significantly increases at synaptic sites following neuronal activity (Phillips 2017; Pitsillou et al. 2020). The precise role of BDNF in pain transmission is still somewhat controversial, though, because evidence has been presented of pro-nociceptive as well as anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities (Cappoli et al. 2020).

BDNF is thought to intervene in the modulation of pain. BDNF has a widespread distribution and functions in pain pathways. Under basal conditions, BDNF is synthesized by various types of neurons and glia within pain pathways. Noxious stimuli can trigger the production and release of BDNF by these cells and/or up-regulate (Merighi 2024).

Data from BDNF-LacZ reporter mouse showed that primary afferent-derived BDNF contributes minimally to the processing of pain and itch. BDNF was expressed primarily by myelinated primary afferents and had limited overlap with the major peptidergic and non-peptidergic sub-classes of nociceptors and pruritoceptors. There was also an extensive neuronal, but not glial, expression in the DH. BDNF deletion in adult mice altered few itch or acute and chronic pain behaviors, beyond sexually dimorphic phenotypes in the tail immersion, HIST, and formalin tests (Dembo et al. 2018).

In the CNS, ACh acts as a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator upon release from groups of ACh projection and interneurons in both brain and spinal cord. Two primary types of receptors respond to ACh. Neuronal nAChRs are ligand-gated cation channels, which are widely expressed in the CNS (Naser and Kuner 2018).

In the DH, ACh interneurons are a sparse population of cells that, although they represent the main source of ACh in the DH, contact a large number of neurons. ACh receptor (AChRs) regulate nociceptive transmission via pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. Elevation of spinal ACh concentrations induced analgesia whereas locally decreasing ACh concentrations or activity (via receptor blockade) strengthened nociceptive sensitivity, inducing hyperalgesia and allodynia. In rats exists a tonic ACh inhibition of spinal nociceptive transmission. In rodents and humans, directly activating muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChRs) reduced pain, and conversely, inhibition of spinal mAChRs induced nociceptive hyper-sensitivity. nAChRs have also been implicated in spinal modulation of pain. intra-thecally administered ACh-esterase inhibitors, such as neostigmine, reduce inflammatory hyper-sensitivity, which is sensitive to muscarinic antagonists (Naser and Kuner 2018).

In the rat, noxious mechanical stimulation of the skin induced neuron double-labeling for fos and for each NK1 and GABAB receptors largely in lamina I. The proportions of fos-positive cells immuno-stained for NK1 or GABAB receptors were higher in lamina I than in the remaining spinal laminae. More fos-positive cells were immuno-reactive (IR) for GABAB receptors than for NK1 in all DH laminae. Co-localization of NK1 and GABAB receptors occurred only in lamina I and was higher in neurons expressing fos. As to the morphological lamina I cell class, NK1-positive cells belonged mainly to the fusiform type while similar proportions of fusiform, pyramidal and flattened NK1 neurons expressed GABAB receptors. No differences occurred between those cell types as to the degree of nociceptive activation. This suggests that the co-localization of NK1 and GABAB receptors is a common feature of fusiform, pyramidal and flattened neurons in lamina I (Castro et al. 2004).

Spinal neurons that receive inputs from primary afferent fibers and whose axons project supraspinally to the medulla oblongata may represent a pathway through which nociceptive and non-nociceptive peripheral stimuli may modulate cardio-respiratory reflexes. Expression of the NK1R is believed to be an indicator of lamina I cells that receive nociceptive inputs from SP releasing afferents, and similarly, somatostatin (STT2A) receptor expression may be a marker for neurons receiving STT inputs. In rat spinal neurons, NK1 and STT2A receptors in lamina I were localized mainly to separate populations of retrogradely labeled cells with fusiform, flattened and pyramidal morphologies. With visceral stimulation, many retrogradely labeled cells expressing c-fos were immuno-reactive for the NK1R, and a smaller population was STT2A positive. In contrast, with cutaneous stimulation, only NK1-positive retrogradely labeled cells showed c-fos expression. Hence, lamina I neurons receiving noxious cutaneous and visceral stimuli via NK1R activation project to NTS and may thus be involved in coordinating nociceptive and cardio-respiratory responses. Moreover, a sub-population of projection neurons that respond to visceral stimuli may receive STT inputs of peripheral, local or supraspinal origins (Gamboa-Esteves et al. 2004).

Nociceptive primary afferents release glutamate, activating postsynaptic glutamate receptors on spinal DH neurons. Glutamate receptors, both ionotropic and metabotropic, are also expressed on presynaptic terminals, where they regulate neurotransmitter release. The rodent DH contains presynaptic glutamate ionotropic (AMPA, NMDA, kainate) and metabotropic receptors (Bardoni 2013).

Kainate receptors are expressed in nociceptive pathways, including the DRG, spinal cord, THAL and cortex. Functional kainate receptors are located postsynaptically or are located presynaptically, where they modulate excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmission. Kainate receptors can regulate nociceptive responses (Wu et al. 2007).

There is an interaction between midazolam, a benzodiazepine-GABAAR agonist, and two glutamate receptor antagonists on acute thermal nociception. Sprague-Dawley rats were implanted with chronic lumbar intra-thecal catheters and were monitored for their tail-withdrawal response to an acute heat stimulus after intra-thecal administration of saline, midazolam, AP-5, or YM872, where AP-5 is an NMDAR antagonist and YM872 is an AMPAR antagonist. Motor disturbance and behavioral changes occurred. Dose-dependent increases in the tail-flick latency (TFL) occurred with midazolam, AP-5, and YM872. When combining midazolam with AP-5 or YM872, a potent synergy in analgesia occurred with decreased behavioral changes and motor disturbance (Nishiyama et al.1999).

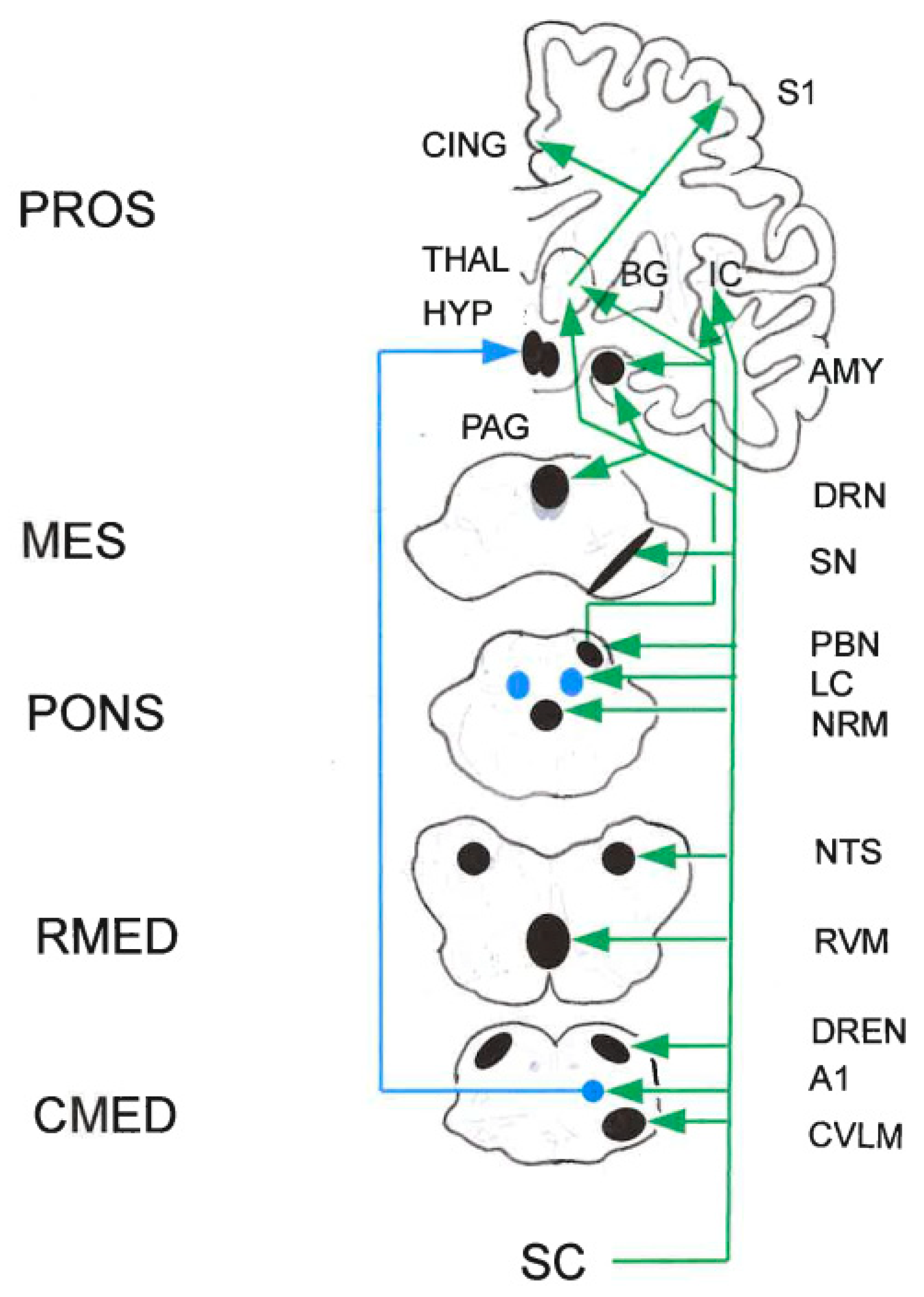

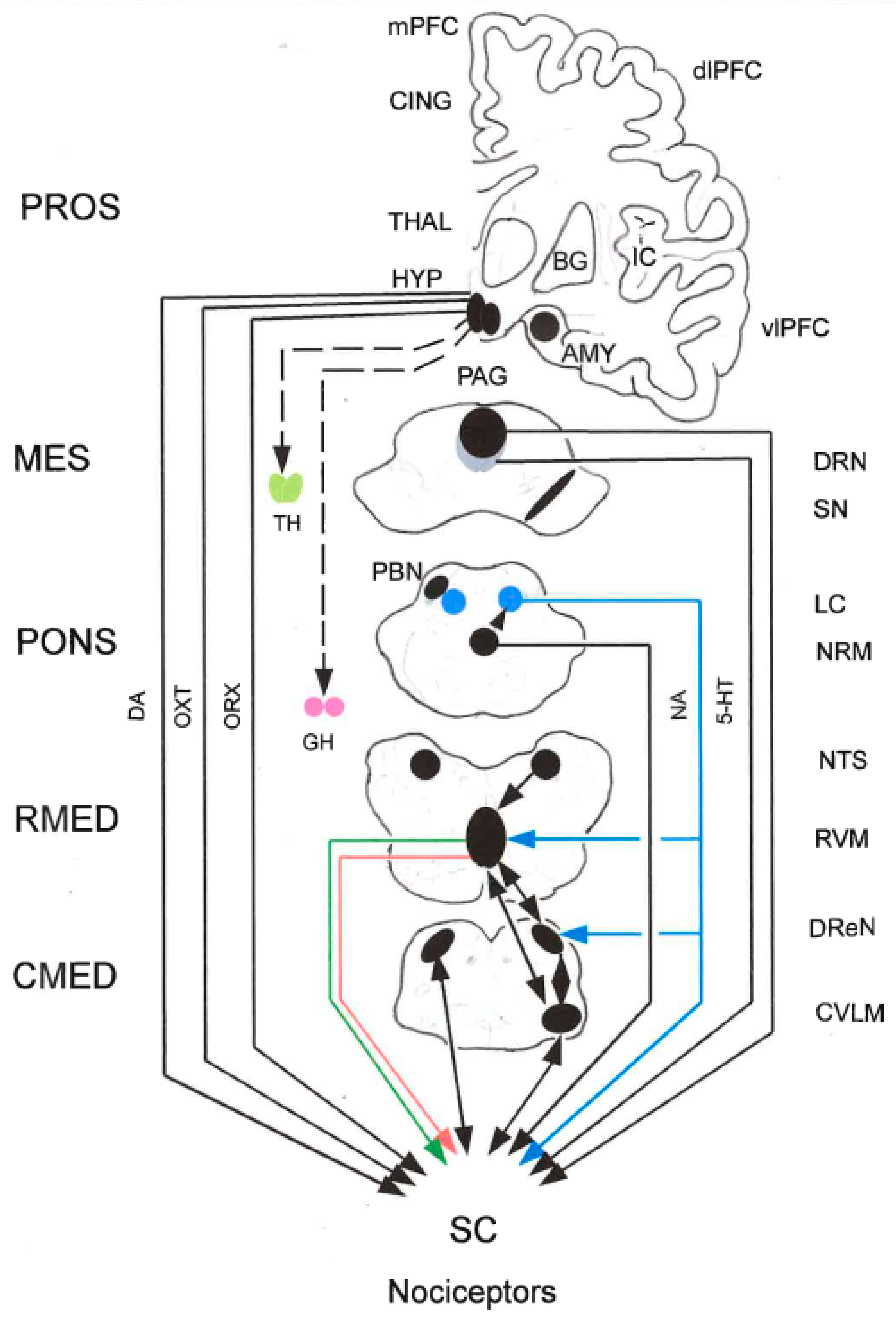

Important nociceptive structures ascending from the spinal cord up to the cerebral cortex are illustrated in

Figure 3. Grosso modo, these structures are also involved in pain modulation (

Figure 4).

2.5. The PAG-Triad Connection

Several brain areas modulate spinal pain transmission through direct projections to the DH. The descending modulation is exerted by neurotransmitters acting both at spinally projecting neurons and at interneurons that target the projection neurons.

In the rat, μ-opioid, GABAB, and NK1 receptors occur in spinally projecting neurons of major medullary pain control areas: RVM, NTS, dorsal reticular nucleus (DReN), ventral reticular nucleus (VReN), and lateral-most part of the caudal ventro-lateral medulla (CVLM). The retrograde tracer cholera toxin sub-unit B was injected into the spinal DH. The RVM contained the majority of double-labeled neurons followed by the dorsal raphé nucleus (DRN). In general, high percentages of μ-opioid- and NK1-expressing neurons were retrogradely labeled, whereas GABAB receptors were mainly expressed in neurons that were not labeled from the cord. Hence, μ-opioid and NK1 receptors play an important role in direct and indirect control of descending modulation. The co-localization of μ-opioid and GABAB in DReN neurons suggests that the pro-nociceptive effects of this nucleus may be controlled by local opoidergic and GABAergic inhibition of the pro-nociception increased during chronic pain (Pinto et al. 2008a,b).

5-HT RVM neurons modulate the activity of RVM neurons. The RVM also contains opioid-sensitive neurons as the activity of OFF-cells is enhanced by μ-opioid agonists whereas the opposite occurs with ON-cells. The local neurochemical control also involves GABA-mediated inhibition, which is triggered by opioids. Local CCK receptors (CCK2) provide further possibilities of fine-tuning the control within the RVM. The endovanilloid system is remotely activated from the PAG since agonists of the TRPV1 injected into the PAG induce glutamate-mediated activation of the activity of OFF-cells. The endovanilloid system in the RVM seems to be inactivated in non-noxious conditions or during acute pain. The system is only activated in the RVM in situations of chronic pain, namely during neuropathic conditions (Martins and Tavares 2017).

Dynamic shifts in the balance between pain-inhibiting and pain-facilitating outflows from the brainstem play a role in setting the gain of nociceptive processing as dictated by behavioral priorities, but are also likely to contribute to pathological pain states (Heinricher et al. 2009).

2.5.1. Peri-Aqueductal Gray (PAG)

Top-down afferents to the PAG arise from various cortical and sub-cortical brain regions, including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and AMY. Changes in connectivity between the ACC and the PAG are prominent in fMRI studies in chronic pain patients. In addition, lesions of the ACC are generally agreed to reduce nociception in human patients. The PFC/ACC-AMY-PAG projections from the PAG to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) have been implicated in avoidancebehaviors in rodents. Both glutamatergic and GABAergic projections from PAG impinge on both DA and GABAergic neurons in VTA. Although DA neurons comprise the majority of the neurons within the VTA and DA in the PAG modulates pain thresholds, the VTA sends primarily GABAergic inputs to PAG (Bagley and Ingram 2020).

The PAG integrates information from cortical and sub-cortical areas to modulate many different behaviors, including defensive responses to pain, threat and stress, as well as cardio-vascular control, and control of respiration, lactation and feeding. Stimulation of the ventro-lateral PAG elicits analgesia in humans and anti-nociception in rats, which is sensitive to naloxone. In rats, the behavioral anti-nociception produced by opioids is mediated by activation of PAG output neurons projecting to the RVM (Bagley and Ingram 2020).

ORX participates in pain modulation. Orexin-1 and orexin-2 receptors (Ox1r and Ox2r) occur at high density in the ventro-lateral PAG (vlPAG). Chemical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus (lHYP) with carbachol induces anti-nociception in the tail-flick test, a model of acute pain, and Ox1r-mediated anti-nociception in the vlPAG is modulated by the activity of vlPAG cannabinoid CB1 receptors. In the current study, TCS OX2 29, an Ox2r antagonist (5, 15, 50, 150, and 500 nmol/L), was microinjected into the vlPAG 5 min before the administration of carbachol (125 nmol/L). It has been shown that the anti-nociceptive effect of ORX is partially mediated by activation of vlPAG Ox2 receptors. It seems that Ox2 and CB1 receptors act through different pathways and Ox2r-mediated anti-nociception does not depend on CB1 receptor activity (Esmaeili et al. 2017).

A sub-population of DA neurons in the PAG/DRN are important modulators of anti-nociception. It was hypothesized that PAG DA neurons contribute to the analgesic effect of D-amphetamine via a mechanism that involves descending modulation via the RVM. Male C57BL/6 mice showed increased c-fos expression in PAG DA neurons and a significant increase in paw-withdrawal latency to thermal stimulation after receiving a systemic injection of D-amphetamine. Targeted micro-infusion of D-amphetamine, L-DOPA, or the selective D2 agonist quinpirole into the PAG produced analgesia, while a D1 agonist had no effect. Inhibition of D2 receptors in the PAG by eticlopride prevented the systemic D-amphetamine analgesic effect. D-amphetamine and PAG D2 receptor-mediated analgesia were inhibited by intra-RVM injection of lidocaine or the GABAAR agonist muscimol, indicating a PAG-RVM signaling pathway in this model of analgesia. Hence, D-amphetamine analgesia is partially mediated by descending inhibition and D2 receptors in the PAG are responsible for this effect via modulating neurons that project to the RVM (Ferrari et al. 2021).—Micro-injection of cumulative doses of morphine into the ventral PAG (vPAG) caused anti-nociception that was dose-dependently inhibited by a DA receptor antagonist, which had no effect on nociception when administered alone. Injection of the DA receptor agonist (-) apomorphine into the vPAG caused a robust anti-nociception that was inhibited by the D2 antagonist eticlopride but not the D1 antagonist SCH-23390. The effects of DA on GABAA-mediated evoked eIPSCs were measured in PAG slices. Administration of M-ENK inhibited peak eIPSCs by 20-50%. DA inhibited eIPSCs by approximately 20-25%. These data indicate that PAG DA has a direct anti-nociceptive effect in addition to modulating the anti-nociceptive effect of morphine (Meyer et al. 2009). In the PAG and NAc, both D1- and D2-like receptors are involved as analgesic targets, while in the striatum and spinal cord, anti-nociception of DA is mainly mediated by D2-like receptors (Wang et al. 2021).

The lateral HYP (lHYP) has been implicated as part of the descending pain modulatory system. The lHYP modifies nociception in the spinal DH partly through connections with the PAG. To determine whether lHYP-induced anti-nociception mediated by the PAG depends on NK1R, behavioral experiments were conducted in which the cholinergic agonist carbachol was micro-injected into the lHYP of lightly anesthetized female Sprague-Dawley rats- and anti-nociception was obtained on the tail flick or foot withdrawal tests. A specific NK1R antagonist was micro-injected in the PAG, which abolished the lHYP-induced anti-nociception. This supports the hypothesis that anti-nociception produced by activating neurons in the lHYP is mediated in part by the subsequent activation of neurons in the PAG by NK1Rs (Holden et al. 2009).

CGRP receptors are widely distributed in the CNS. In male rats, the effects of intra-cerebro-ventricular (ICV) injection of CGRP was investigated on pain behavioral responses and on levels of monoamines in the PAG during the formalin test. ICV injection of CGRP led to a significant pain reduction in acute, middle and chronic phases of the formalin test. Dialysate concentrations of DA, NA, 5-HT and HIAA in the PGA area showed an increase in acute phase, middle phase and beginning of the chronic phase of the formalin test. Hence, CGRP significantly reduced pain by increased concentrations of monoamines and their metabolites in dialysates from PAG when injected ICV to rats (Rahimi et al. 2018).

The PAG is a critical component of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) since it is densely packed with CB1 receptors. In part, cannabinoids and opiates inhibit pain by activating the PAG. In response to noxious stimuli, the PAG released endogenous anandamide. In rats, electrical PAG stimulation induced analgesic effects after intra-dermal formalin injection, which were associated with increased anandamide release in the PAG. These analgesic effects were attenuated after intra-PAG injection of the CB1R antagonist, S141716, suggesting a critical role of CB1R in this brain region for pain modulation. An important role of PAG eCBs in chronic pain inhibition was also suggested by the fact that, whereas early-phase algesia in the hindpaw after formalin injection was not affected by an exogenous cannabinoid ligand, HU-210, injection directly into the dorsal PAG, late-phase algesia was significantly reduced. Administration of HU210 significantly attenuated formalin-evoked increases in c-fos expression in the caudal lateral PAG (Milligan et al. 2019).

If the anti-nociceptive mechanisms are distinct, cross-tolerance between cannabinoids and opioids should not develop. In male Sprague-Dawley rats, this hypothesis was tested by measuring the anti-nociceptive effect of micro-injecting morphine into the vlPAG of rats pretreated with the cannabinoid HU-210 for two days. The rats were injected twice a day for two days with vehicle, morphine, HU-210, or morphine combined with HU-210 into the vlPAG. Repeated injections of morphine caused a rightward shift in the morphine dose-response curve on Day 3 (i.e., tolerance developed). No tolerance was evident in rats pretreated with morphine combined with HU-210. In rats pretreated with HU-210 alone, morphine anti-nociception was enhanced. This enhancement was blocked by pretreating rats with the cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM-251, and it also disappeared when rats were tested one week later. Acute micro-injection of HU-210 into the PAG antagonized morphine anti-nociception, suggesting that HU-210-induced enhancement of morphine anti-nociception is a compensatory response. Hence, there was cross-tolerance between morphine and HU-210. Cannabinoid pretreatment enhanced the anti-nociceptive effect of micro-injecting morphine into the vlPAG (Wilson et al. 2008).

Noxious stimulation increased the release of opioid peptides in the vlPAG. Endogenous opioids, including L-ENK and M-ENK, and β-endorphin, are widely expressed in the brain. Endogenous opioids contribute to the control of the descending pain modulatory system through the activation of δ-, μ-, κ- receptors, and nociceptin-opioid peptide (NOP) receptors. By order of preference, the endogenous opioids, such as ENKs, β-endorphins, and Dyn, bind to δ-, μ-, κ- receptors, respectively. Opioids are involved in both descending inhibition and descending facilitation from PAG pathways relayed in the RVM and LC, respectively. In the PAG-LC circuit, μ-opioid receptors inhibit a sub-type of glutamate neurons, which project to NA LC neurons. Opioids are also involved in the mediation of descending inhibition from the LC through μ-opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of GABAergic neurons that disinhibit NA neurons projecting to the spinal cord (Tavares et al. 2021).

ENK-containing terminals occur throughout the PAG but are densest in the vlPAG, and are apposed to GABA and non-GABA-containing dendrites, as well as PAG output neurons that project to the RVM. A portion of the PAG-RVM projection neurons express μ-opioid receptors and δ-opioid receptors, indicating that endogenous opioids directly inhibit some PAG-RVM output neuron. Some of the ENK-containing neurons in the PAG send projections to the AMY and the NAc, indicating that opioid release in these areas may help to coordinate the response to pain in higher structures. β-Endorphin-containing fibers from the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (HYP ARC) project strongly to the PAG. Stimulation of the HYP ARC increases the release of β-endorphin in the PAG, but stimulation of the PAG predominately increases release of M-ENK. Both M-ENK and β-endorphin are full agonists at μ-opioid receptors. Endomorphin 2-containing neurons from the HYP project to PAG and RVM. This peptide is a partial agonist at μ-opioid receptors in the PAG. β-Endorphin release in the PAG is associated with stress-induced analgesia as well as peripheral injury. Similar increases in endomorphin 2 concentrations occurred following neuropathic pain. Stimulation of the AMY induced release of the κ-opioid receptors agonist Dyn in the PAG, but Dyn did not elicit analgesia when micro-injected into the PAG. Thus, the endogenous opioid system responds to painful situations by activating opioid receptors in the PAG (Bagley and Ingram 2020).

Opioid-triggered analgesia was mediated by vlPAG to RVM projections, while non-opioid-triggered analgesia could be elicited by projections of the lateral PAG (lPAG) and the dorso-lateral PAG (dlPAG) to RVM (Peng et al. 2023). Stimulation of the vlPAG produced opioid-mediated analgesia, as well as freezing and quiescent behaviors, whereas stimulation of the lateral PAG column and more dorsal columns produced escape behaviors such as jumping and flight responses (Bouchet and Ingram 2020; Mills et al. 2021). μ-Opioid, δ-opioid, κ-opioid, and nociception/orphanin receptors (NOPRs) are prevalent in the PAG region. NOPRs can presynaptically inhibit GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the vlPAG and postsynaptically inhibit PAG-RVM projections, leading to hyperalgesia and reverse opioid-induced analgesia (Peng et al. 2023).—Given the dense expression of μ-opioid receptors and the role of DA in pain, the recently characterized DA neurons in the vPAG/DRN are a potentially crucial site for the anti-nociceptive actions of opioids. In a mouse line, μ-opioid receptor activation led to a decrease in inhibitory inputs onto the vPAG/DRN DA neurons. These neurons also expressed the vesicular glutamate type 2 transporter and co-released DA and glutamate in a major downstream projection structure—the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST). Hence, vPAG/DRN DA neurons likely play a role in opiate anti-nociception, potentially via the activation of downstream structures through DA and glutamate release (Li et al.2016).

The descending pain modulatory circuit is sexually dimorphic. Male rats have significantly higher concentrations of the μ-opiod receptors in the vlPAG than cycling females, and selective lesions of μ-opiod receptors disrupt morphine analgesia in males, but not females (Bagley and Ingram 2020).

NO concentrations in brain nuclei, such as the hippocampus (HIPP) and brainstem, are involved in morphine analgesia, but the relationship between the dorsal HIPP and the dlPAG needs clarification. In Wistar rats, morphine administered intra-peritoneally ten minutes before formalin injection into the left hind paw reduced inflammatory pain in the early and late stages of the rat formalin test. High levels of NO in dlPAG may regulate the pain process in downward synaptic interactions (Hashemi et al. 2022).