Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

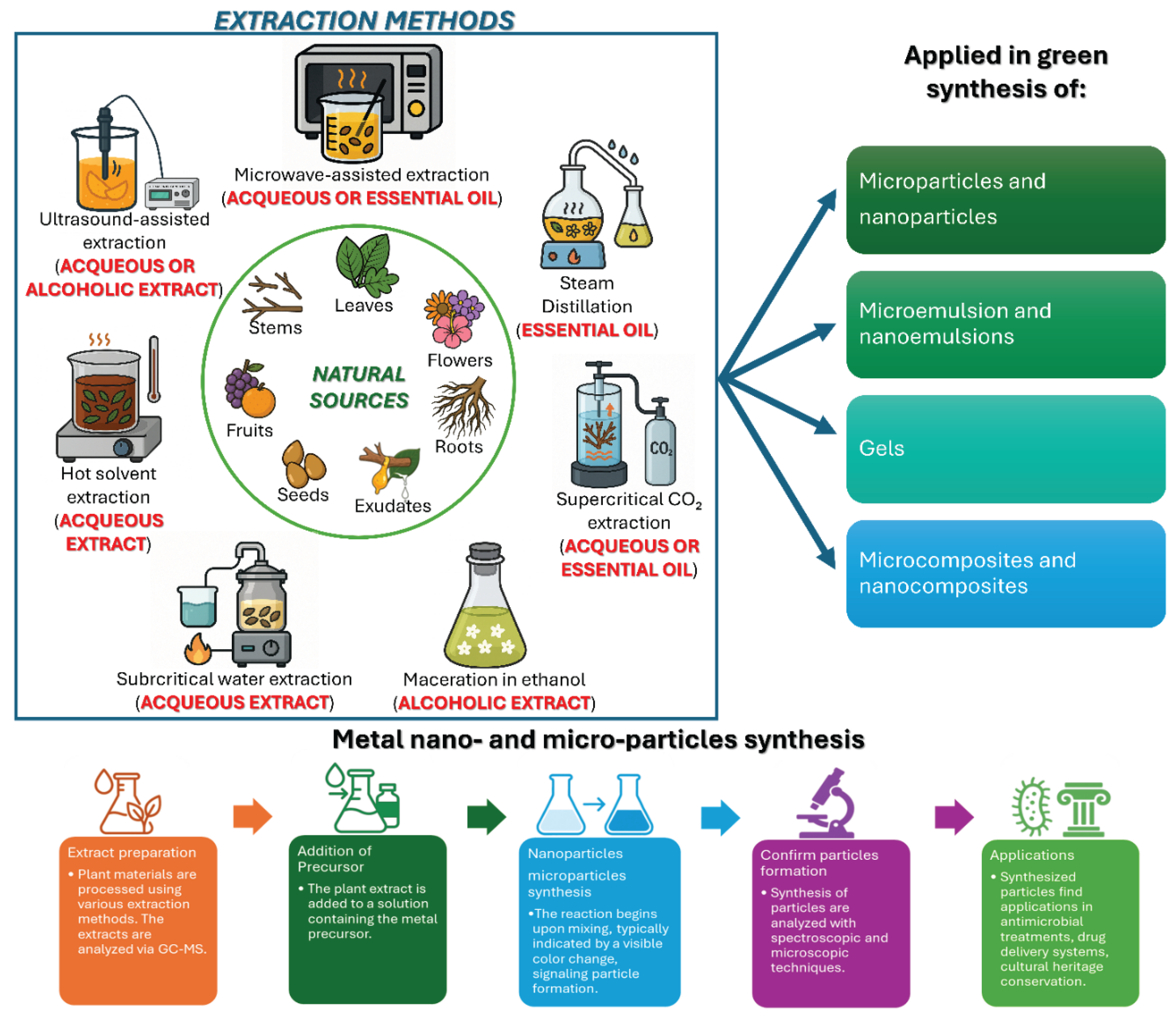

1. Introduction

| Nomenclature | Acronyms abbreviations |

Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium Oxide | TiO2 MPs/SM | Functionalized particles produced in natural extracts of plants | Microparticles (in size) as confirmed in this work |

| Calcium Carbonate | CaCO3 MPs/SM | Functionalized particles produced in natural extracts of plants | Microparticles (in size) as confirmed in this work |

| Microparticles | MPs | Microparticles are tiny spherical particles, typically ranging from 1 to 1000 micrometers in diameter. | Microparticles used for biological assay in this work |

| Nanoparticles | NPs | Nanoparticles are incredibly small particles, typically between 1 and 100 nanometers in size | [1] |

| Satureja montana | SM | Plant species, which is native from the Mediterranean region and cultivated all over Europe, Russia, and Turkey |

Satureja montana L., Lamiaceae, commonly known as winter savory This work |

| Natural Plant Extracts | NPEs | Extracts may be derived from whole plants or from specific parts of plants such as leaves, stems, barks, roots, flowers and/or fruits | Natural Extracts (by drying the leaves of the plants) were performed at low temperature and in bi-distilled water. This work |

| Essential Oils | EOs | Essential Oils are precious mixtures of liquid and volatile aromatic substances, extracted mainly by steam distillation from plant material coming from various types of aromatic plants; they can also be obtained by cold pressing, as in the case of oils derived from citrus peel or by solvent extraction. | [47,48,49,50] |

| Nano-Emulsions | (NEs) | Nanoemulsions are nano-sized emulsions (20–200 nm), thermodynamically stable isotropic system in which two immiscible liquids are mixed to form a single phase | [48,49,50] |

| Satureja montana Essential Oils and Tween-80 | SMEOs | Oil in water Nano-Emulsions (NEs) composed of SMEOs (Satureja montana Essential Oils) and Tween-80 | [48,49] |

| Montmorillonite | NMT | Montmorillonite is a naturally occurring clay mineral belonging to the smectite group, primarily of aluminosilicate | [50] |

| Chitosan-nano-TiO2 Daisy Essential Oil | chitosan/nano TiO2/DEO | Chitosan film, incorporating nano-TiO2, functionalized with Daisy Essential Oil | [53,54] |

| Magnesium Oxide and Calcium Carbonate Moringa oleifera natural extract | MgO/CaCO3/ Moringa oleifera NPs | Biosynthesized MgO and CaCO3 nanoparticles (NPs) using Moringa oleifera natural extract | [58] |

| Iron-Calcium Alginate-Calcium Carbonate microparticles/microspheres | Fe-Alg-CaCO3 MPs | Foliar fertilizer on lettuce plants in an aquaponic system | [59] |

| Zinc- Alginate-Calcium Carbonate microparticles | Zn-Alg-CaCO3 MPs | eco-sustainable solution for precision fertilization of Tomato plants in aquaponic agriculture approach | [61] |

| Volatile Organic Compounds | VOCs | Volatile organic compounds are a group of chemicals that easily evaporate at room temperature and are commonly found in various products used indoors and outdoors (in this study terpenes family) | [56] |

| Methylene Blue | MB | Methylene blue is used as a bacteriologic stain or dye and indicator | [57] |

| Radical Oxygenated Species | ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are unstable, highly reactive molecules containing oxygen that can cause damage to cells by reacting with other molecules. | [49,50,64,65] |

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Functionalized Microparticles and Their Characterization Study

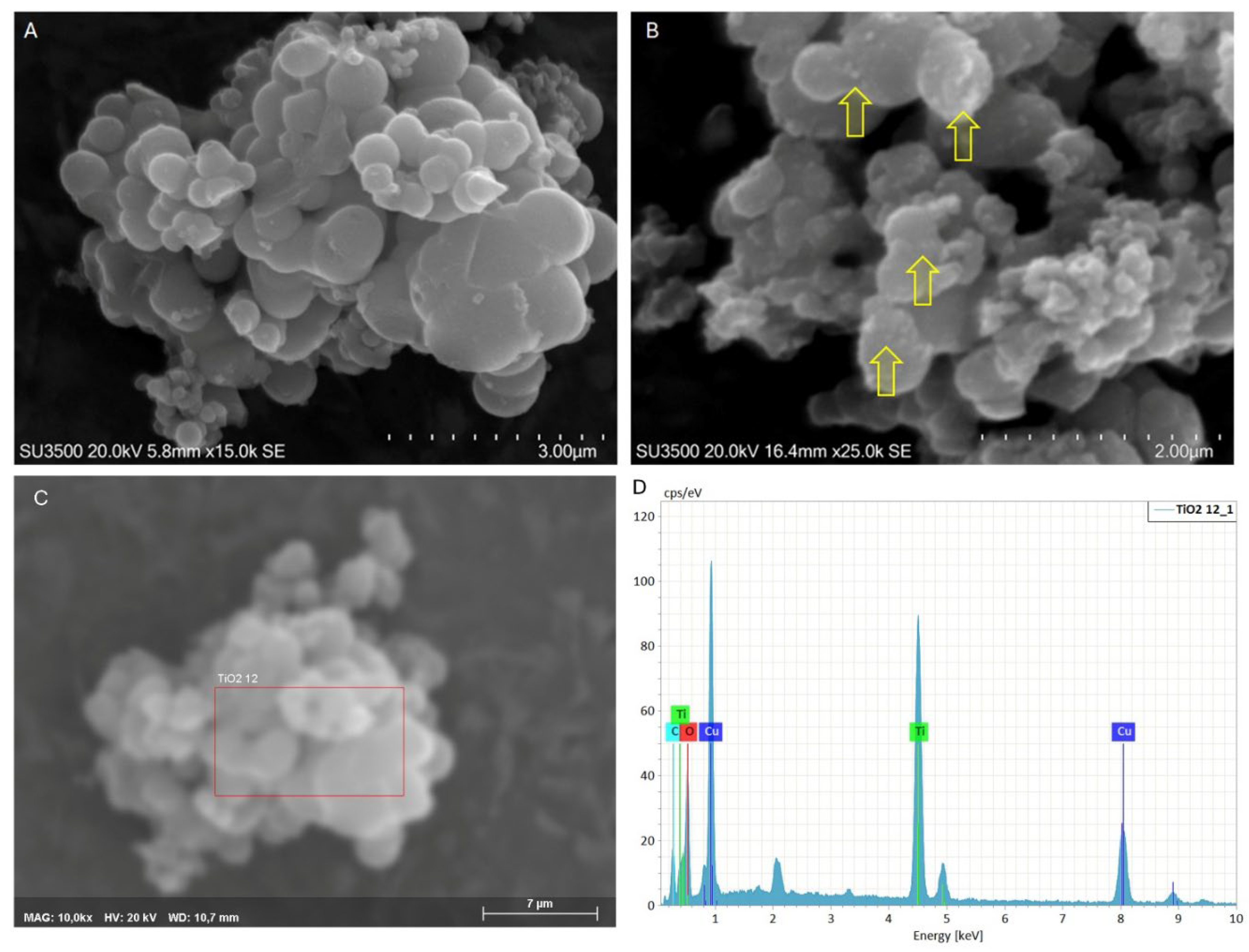

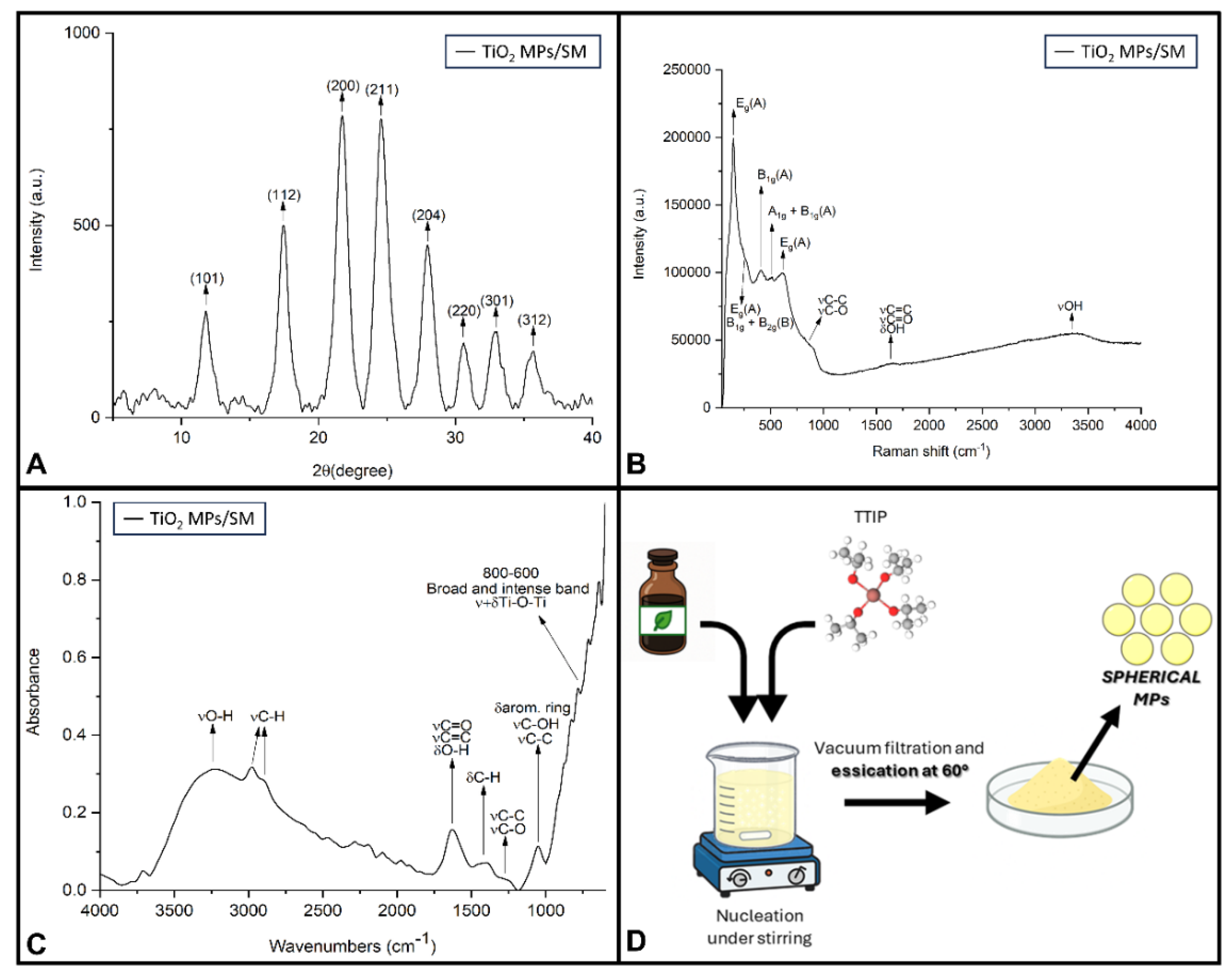

2.1.1. TiO2 MPs/SM

| Band (cm−1) | Assignment | Ref. | ||

| RAMAN SPECTROSCOPY | ||||

| 146 | Eg mode (anatase) | [70,71,72] | ||

| 219-279 | Eg (anatase) B1g + B2g mode (brookite) |

[70,71,72,73] | ||

| 411 | B1g mode (anatase) | [70,71,72] | ||

| 517 | A1g + B1g mode (anatase) | [70,71,72] | ||

| 623 | Eg mode (anatase) | [70,71,72] | ||

| ̴ 874 | νC–OH νC–C δCH/CH2 |

[74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] | ||

| ̴ 1627 | νC=O νC=C δO-H |

[74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] | ||

| ̴ 3352 | νO-H | [84] | ||

| FTIR SPECTROSCOPY | ||||

| 3400 | νO–H | [87,88,89,90,91] | ||

| 1630 | δO–H νC=O νC=C |

[87,88,89,90,91] | ||

| 2974 | νas –CH3 | [90,91] | ||

| 2893 | νs –CH2 | [90,91] | ||

| 1454, 1395 | δas/s –CH3 δas/s –CH2 |

[90,91] | ||

| 1268 | νC–O νC–C |

[90,91] | ||

| 1051 | νC–O νC–C ring vibration |

[90,91] | ||

| 800-600 | ν+δ Ti–O–Ti | [85,86] | ||

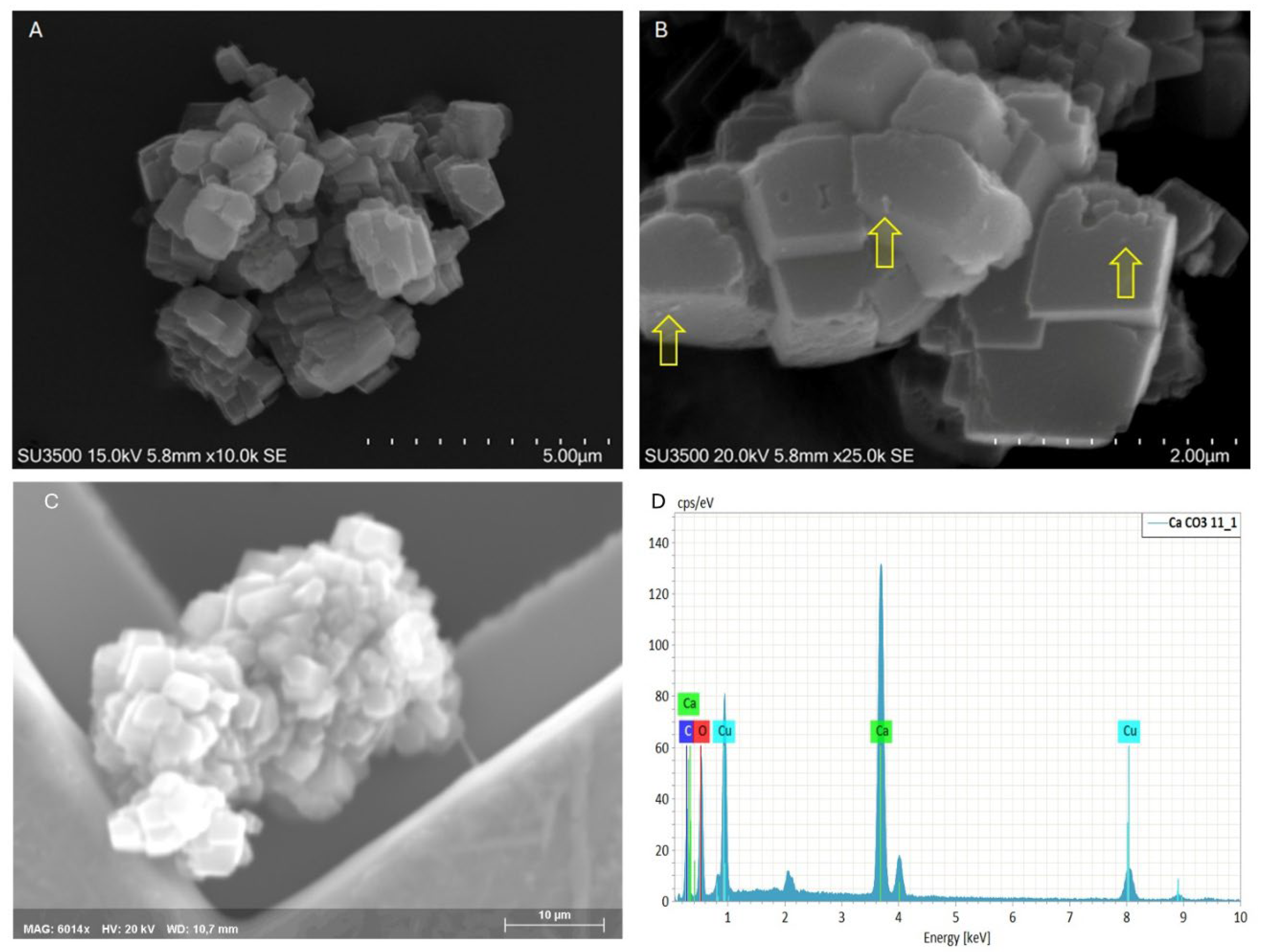

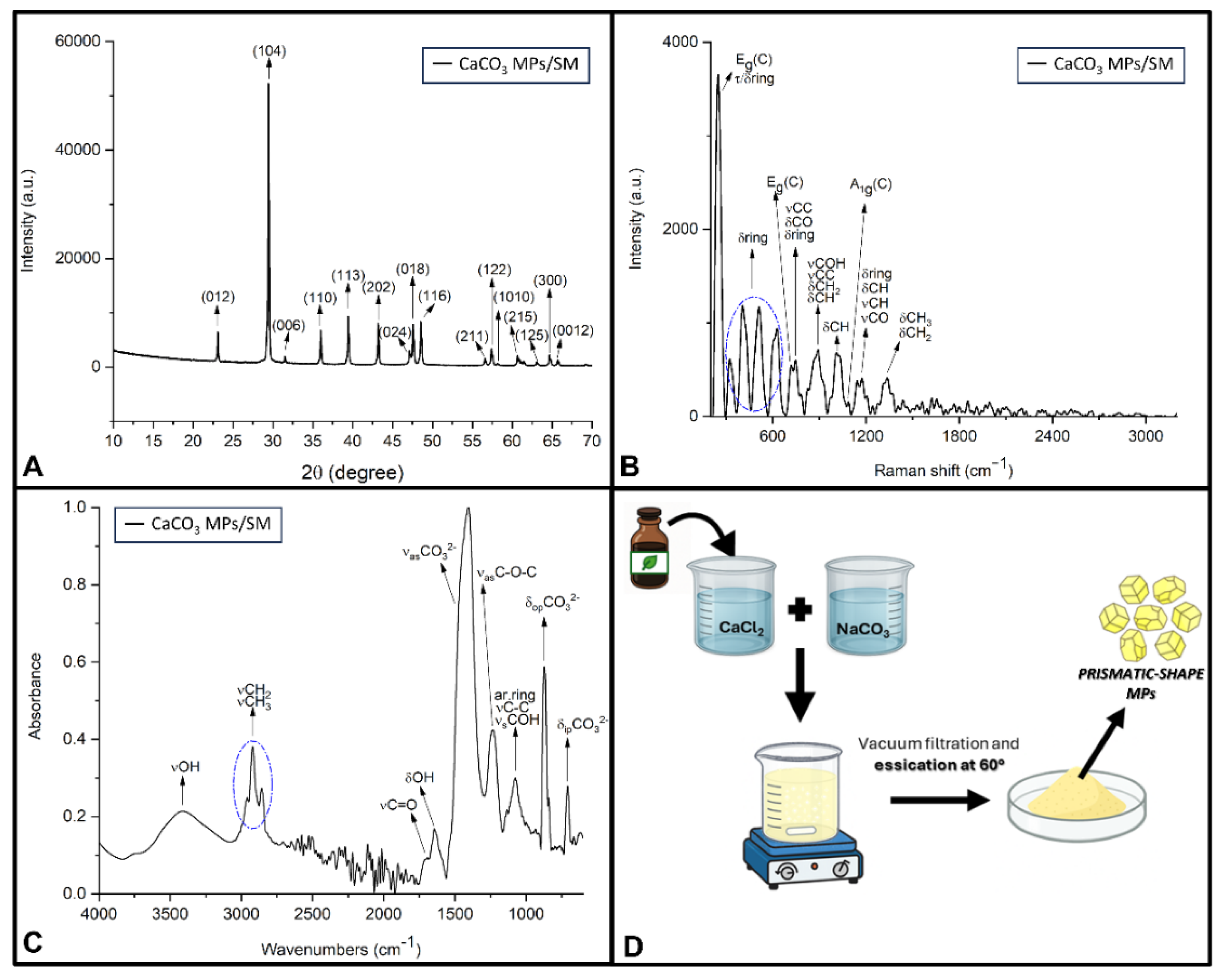

2.1.2. CaCO3 MPs/SM

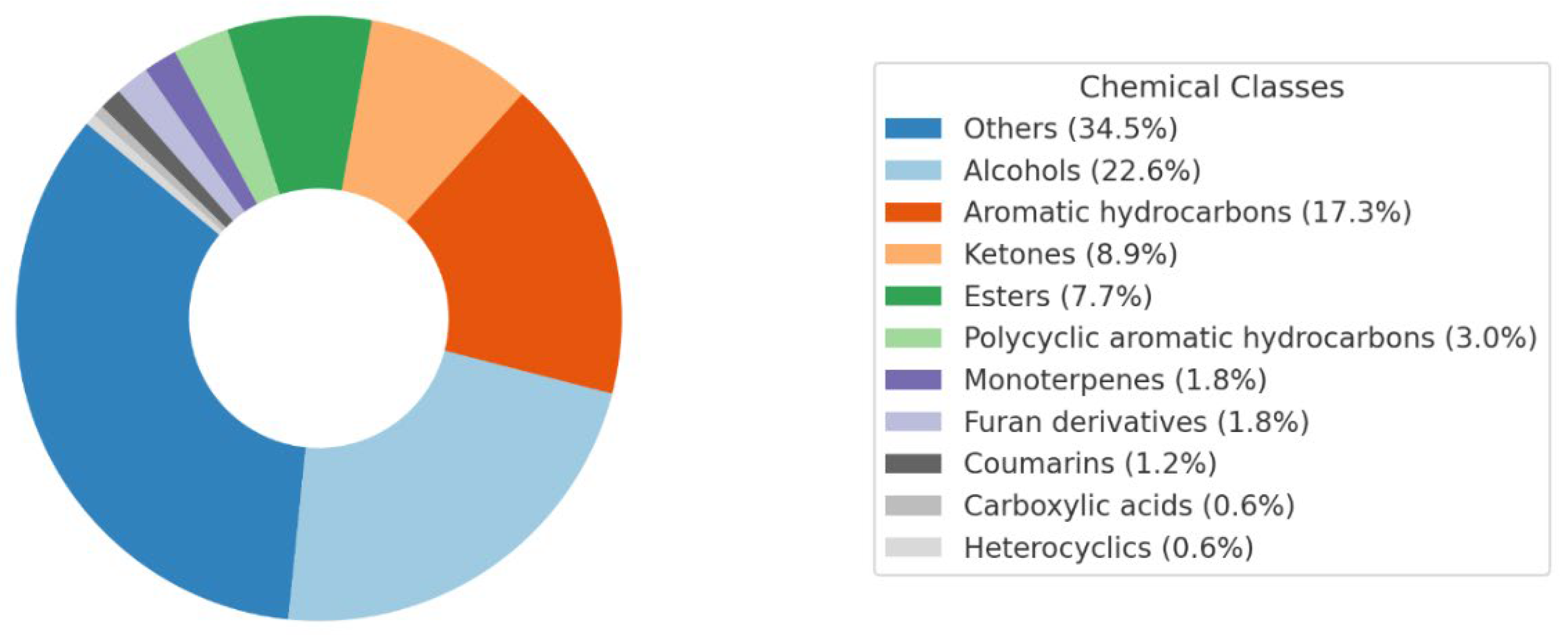

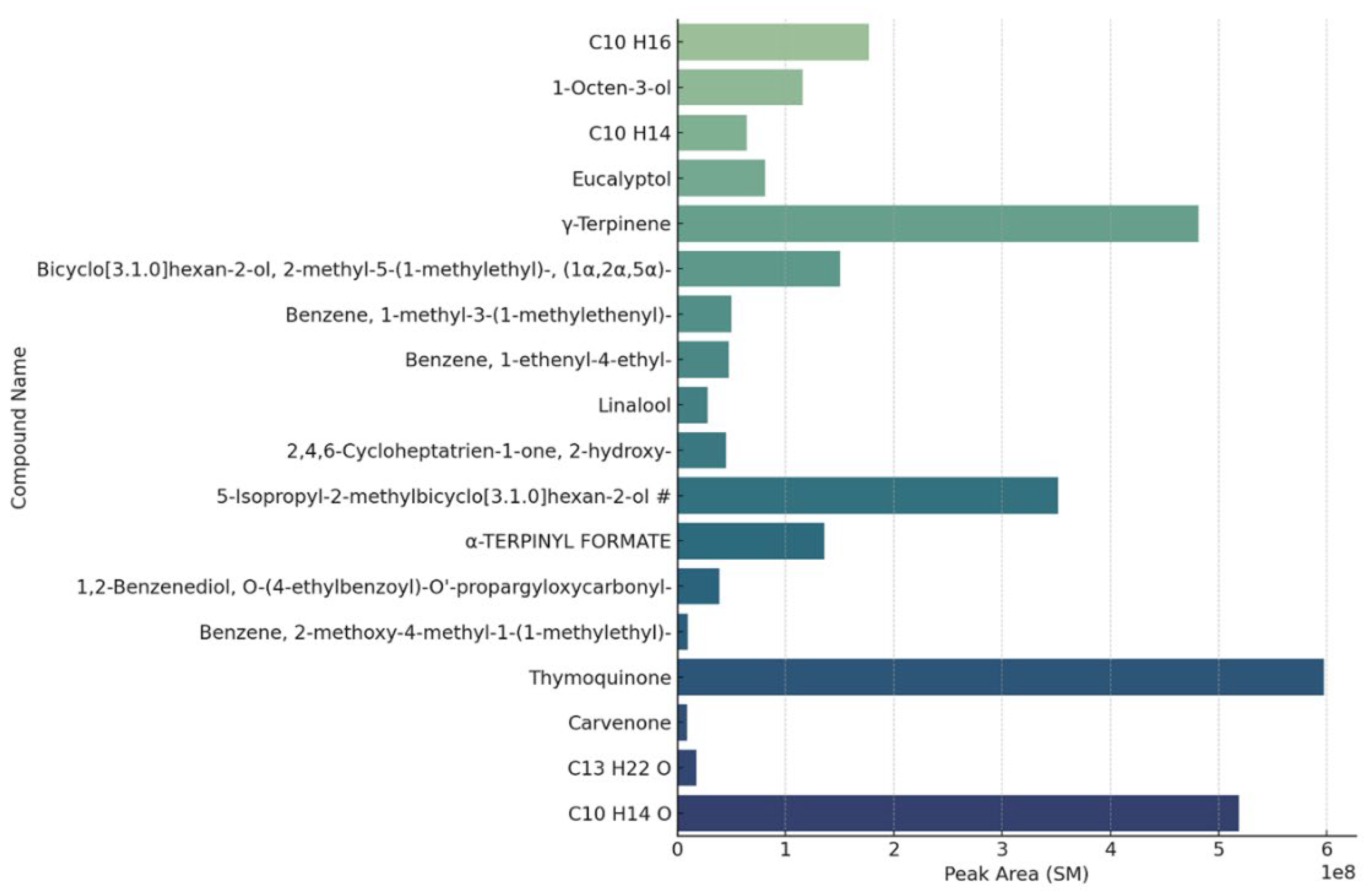

2.2. Chemical Composition of NPEs from SM by GC-MS

2.2.1. Targeted Analysis

2.2.2. Untargeted Analysis

2.3. Antimicrobial Screening

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Materials and Chemicals/Reagents

3.2. Preparation of TiO2 Microparticles in SM’ Natural Extracts (TiO2 MPs/SM)

3.3. Preparation of CaCO3 Microparticles in SM’ Natural Extracts (CaCO3 MPs/SM)

3.4. (TiO2 MPs/SM) and (CaCO3 MPs/SM) Characterization Study

3.4.1. SEM/EDX

3.4.2. XRD

3.4.3. Raman Spectroscopy

3.4.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

3.4.5. GC-MS Analysis of SM Extract: Molecular Composition

3.5. Experimental Biological Testing and Sampling

3.5.1. Statistical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patra, A.R.; Pattnaik, A.; Ghosh, P. The Latest Breakthroughs in Green and Hybrid Nanoparticle Synthesis for Multifaceted Environmental Applications. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2025, 106157. [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, A.; Sahu, J.N.; Poonia, A.K.; Ghosh, P. Current Perspective of Nano-Engineered Metal Oxide Based Photocatalysts in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Wastewater. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2023, 190, 667–686. [CrossRef]

- Suman, T.Y.; Radhika Rajasree, S.R.; Ramkumar, R.; Rajthilak, C.; Perumal, P. The Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using an Aqueous Root Extract of Morinda Citrifolia L. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2014, 118, 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, P.; Anbalagan, K.; Manosathyadevan, M.; Lee, K.J.; Cho, M.; Lee, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Oh, S.G.; Bang, K.S.; Oh, B.T. Green Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles Using Zingiber Officinale Root Extract and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles against Food Pathogens. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2014, 37, 1935–1943. [CrossRef]

- Behravan, M.; Hossein Panahi, A.; Naghizadeh, A.; Ziaee, M.; Mahdavi, R.; Mirzapour, A. Facile Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Berberis Vulgaris Leaf and Root Aqueous Extract and Its Antibacterial Activity. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 124, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.Y.; Mazhar, K.; Raees, L.; Mukhtiar, A.; Khan, F.; Khan, M. Green Synthesis of Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles Using Roots Extract of Ziziphus Oxyphylla Edgew Its Characterization and Antibacterial Activity. Mater Res Express 2022, 9, 105001. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh Kumar, V.; Dinesh Gokavarapu, S.; Rajeswari, A.; Stalin Dhas, T.; Karthick, V.; Kapadia, Z.; Shrestha, T.; Barathy, I.A.; Roy, A.; Sinha, S. Facile Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Antidiabetic Potent Cassia Auriculata. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 159–163. [CrossRef]

- Flexa-Ribeiro, B.; Garcia, M.D.N.; Silva, A.C. de J.; Carvalho, J.C.T.; Rocha, L.; Faustino, S.M.M.; Fernandes, C.P.; da Silva, H.F.; Machado, F.P.; Hage-Melim, L.I. da S.; et al. Essential Oil from Curcuma Longa Leaves: Using Nanotechnology to Make a Promising Eco-Friendly Bio-Based Pesticide from Medicinal Plant Waste. Molecules 2025, 30, 1023. [CrossRef]

- Savković, Ž.; Džamić, A.; Veselinović, J.; Grbić, M.L.; Stupar, M. Exploring the Potential of Essential Oils against Airborne Fungi from Cultural Heritage Conservation Premises. Science of Nature 2025, 112, 32. [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Hernández, I.; Gómez-García, R.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Medina-Herrera, N.; González-Hernández, M.D. Unlocking Essential Oils’ Potential as Sustainable Food Additives: Current State and Future Perspectives for Industrial Applications. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2025, 17, 2053. [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Cubeddu, L.X.; Gill, E.J. Harnessing Nanotechnology to Enhance Essential Oil Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 520. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Sana; Aftab, T.; Khan, M.M.A. Conclusions and Future Prospects of Plant-Based Essential Oils. In Essential Oil-Bearing Plants: Agro-techniques, Phytochemicals, and Healthcare Applications; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 381–384 ISBN 9780443248603.

- Silva, E.F. da; Santos, F.A.L. dos; Pires, H.M.; Bastos, L.M.; Ribeiro, L.N. de M. Lipid Nanoparticles Carrying Essential Oils for Multiple Applications as Antimicrobials. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 178. [CrossRef]

- Olaleru, S.A.; Molokwu, M.I.; Mathew, S.; Ejidike, I.P.; Oyebamiji, O.O. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using TiO 2 Nanoparticles Obtained via Chemical and Green Synthesis: A Comparative Analysis. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2025, 97, 541–553. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, S.; Gvozdeva, Y.; Staynova, R.; Grekova-Kafalova, D.; Nalbantova, V.; Benbassat, N.; Koleva, N.; Ivanov, K. Essential Oils – a Review of the Natural Evolution of Applications and Some Future Perspectives. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Verma, S. Importance of Green Chemistry and Nano Techniques in Chemical Synthesis. In Contemporary Trends in Chemical, Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Volume V; Bhumi Publishing: Pune, India, 2025; Vol. V, pp. 72–83 ISBN 978-93-48620-08-8.

- Patadiya, A.; Mehta, D.; Karuppiah, N. Bridging Nature and Nanotechnology: A Review on the Potential of Herbal Nanoparticles in Medicine. E3S Web of Conferences 2025, 619, 05005. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, L.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Fang, H. The Current Status, Hotspots, and Development Trends of Nanoemulsions: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 2937–2968. [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, D.; Wahid, J.B.A.; Karmegam, N.; Jeevika, R.; Sellapillai, L.; Rajkumar, M.; SenthilKumar, K.J. A Comprehensive Review on the Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Advancements in Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Biomedical Materials and Devices 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, D.; Bupesh, G.; Wahid, J.B.A.; Murugeswaran, R.; Ramalingam, J.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Sivasakthi, V.; Panigrahi, J. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Acmella Caulirhiza Leaf Extract: Characterization and Assessment of Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Hemolytic Properties. Biomedical Materials and Devices 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sati, A.; Ranade, T.N.; Mali, S.N.; Ahmad Yasin, H.K.; Pratap, A. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs): Comprehensive Insights into Bio/Synthesis, Key Influencing Factors, Multifaceted Applications, and Toxicity─A 2024 Update. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 7549–7582. [CrossRef]

- Nagime, P. V; Shaikh, N.M.; Singh, S.; Chandak, V.S.; Chidrawar, V.R.; Nweye, E.P. Metallic Nanostructures: An Updated Review on Synthesis, Stability, Safety, and Applications with Tremendous Multifunctional Opportunities. Pharm Nanotechnol 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Soomro, R.; Abdelmonem, M.; Meli, A.D.; Panhwar, M.; Che Abdullah, C.A. A Novel Plant-Based Approach for Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Cancer Therapy. Discover Chemistry 2025, 2, 25. [CrossRef]

- Perveen, F.; Farmn Ullah; Assad Rehman; Haidar Zaman; Waseem Abbas; Muhammad Khan; Muhammad Bilal; Abbas Khan A Review on Nanotechnology-Driven Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Nigella Sativa. Insights-Journal of Health and Rehabilitation 2025, 3, 121–128. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.T.; Sari, I.P.; Yanto, D.H.Y.; Chowdhury, Z.Z.; Bashir, M.N.; Badruddin, I.A.; Hussien, M.; Lee, J.S. Nature’s Nanofactories: Biogenic Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles for Sustainable Technologies. Green Chem Lett Rev 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Narduzzi, M.; Pelosi, C.; Vinciguerra, V.; Antonelli, C.; Vettraino, A.M. Natural Protection for Historic Mural Paintings: Thymus Serpyllum Essential Oil vs. Paracoccus IBR3 2025.

- Abady, M.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Soliman, T.N.; Shalaby, R.A.; Sakr, F.A. Sustainable Synthesis of Nanomaterials Using Different Renewable Sources. Bull Natl Res Cent 2025, 49, 24. [CrossRef]

- Min, W. A Scientometric Review of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development through Evolutionary Perspectives. npj Heritage Science 2025, 13, 215. [CrossRef]

- Srujana, T.L.; Rao, K.J.; Korumilli, T. Natural Biogenic Templates for Nanomaterial Synthesis: Advances, Applications, and Environmental Perspectives. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2025, 11, 1291–1316. [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, B.; Nisha, N.; Baby, N.; Aggarwal, K.; Singh, A.; Kumari, K.; Chandra, R.; Singh, S. Advancements in Silver-Based Nanocatalysts for Organic Transformations and Other Applications: A Comprehensive Review (2019-2024). RSC Adv 2025, 15, 17591–17634. [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, I.; Seghir, B. Ben; Cherif, N.F.; Rebiai, A. Nanomaterials Synthesis and Medicinal Plant Extracts. In Interdisciplinary Biotechnological Advances; 2025; Vol. 103, pp. 103–131.

- Hamad, I.; Aleidi, S.M.; Alshaer, W.; Twal, S.; Al Olabi, M.; Bustanji, Y. Advancements and Global Perspectives in the Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Two-Decade Analysis. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Mangundu, P.; Makaudi, R.; Paumo, H.K.; Ramalapa, B.; Tshweu, L.; Raleie, N.; Katata-Seru, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products and Their Nano Transformation: A Sustainable Option Towards Desert Locust Infestations. ChemistryOpen 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, K.; Anbalagan, T.; Marimuthu, M.; Mariappan, P.; Angappan, S.; Vaithiyanathan, S. Innovative Formulation Strategies for Botanical- and Essential Oil-Based Insecticides. J Pest Sci (2004) 2025, 98, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Peng, J.; Han, Q.; Huang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, X.; Milcovich, G.; Weng, X. Encapsulation of Thyme Essential Oil in Dendritic Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: Enhanced Antimycotic Properties and ROS-Mediated Inhibition Mechanism. Int J Pharm 2025, 669, 125057. [CrossRef]

- Siam, A.M.J.; Abu-Zurayk, R.; Siam, N.; Abdelkheir, R.M.; Shibli, R. Forest Tree and Woody Plant-Based Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 845. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhou, C.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Lin, H.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, S.; Liang, W.; Shao, H. Transforming Bone Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Review of Green-Synthesized Metal Nanoparticles. Cancer Cell International 2025, 25, 193. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ding, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, A.; Yan, X.; Liang, C.; et al. Carrier-Free Nanoparticles—New Strategy of Improving Druggability of Natural Products. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 108. [CrossRef]

- Saghabashi, A.; Sadeghi, A.; Ghodratie, M.; hatami, H.; Alavi Rostami, S.F.; Yazdehi, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Najafi, S.; Mottaghiyan, Z. Antimicrobial Potential of Satureja Species: A Review of Bioactive Compounds and Molecular Mechanisms. Plant Biotechnology Persa 2025, 7, 0–0. [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, S.; Grau, D.; Cristóbal, R.; Moré, E.; De las Heras, X. Chemical Composition of Wild Populations of Thymus Vulgaris and Satureja Montana in Central Catalonia, Spain. JSFA reports 2025, 5, 234–246. [CrossRef]

- Tancheva, L.; Dragomanova, S.; Abarova, S.; Grigorova, V.B.; Gavazova, V.; Stanciu, D.; Tzonev, S.; Kalfin, R. The Potential of Polyphenols Derived from Satureja Montana (Lamiaceae) in Prevention and Treatment of Various Mental Disorders, Including Dementia 2025.

- Štrbac, F.; Krnjajić, S.; Ratajac, R.; Rinaldi, L.; Musella, V.; Castagna, F.; Stojanović, D.; Simin, N.; Orčić, D.; Bosco, A. Anthelmintic Activity of Winter Savory (Satureja Montana L.) Essential Oil against Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Sheep. BMC Vet Res 2025, 21, 405. [CrossRef]

- Zahraoui, E.M. Essential Oils: Antifungal Activity and Study Methods. Moroccan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2025, 6, 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Shanaida, M.; Korablova, O.; Bakalets, D.; Potikha, N.; Rakhmetov, D. Chemotaxonomic Characteristics of Satureja Coerulea (Lamiaceae Family) Based on Analysis of Its Bioactive Compounds. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal 2025, 18, 559–568. [CrossRef]

- Demyashkin, G.; Parshenkov, M.; Tokov, A.; Sataieva, T.; Shevkoplyas, L.; Said, B.; Shamil, G. Therapeutic Efficacy of Plant-Based Hydrogels in Burn Wound Healing: Focus on Satureja Montana L. and Origanum Vulgare L. Scr Med (Brno) 2025, 56, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.K.; Kon, K.V. Fighting Multidrug Resistance with Herbal Extracts, Essential Oils and Their Components; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780123985392.

- Sahu, N.; Upadhyay, P. Phytochemical-Based Drugs for Salmonella Biofilm Disruption. In Salmonella Biofilms: Formation, Resistance, and Therapeutics; Publishing, B., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Maharashtra, India, 2025; pp. 123–143 ISBN 9781837677047.

- Rinaldi, F.; Maurizi, L.; Conte, A.L.; Marazzato, M.; Maccelli, A.; Crestoni, M.E.; Hanieh, P.N.; Forte, J.; Conte, M.P.; Zagaglia, C.; et al. Nanoemulsions of Satureja Montana Essential Oil: Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity against Avian Escherichia Coli Strains. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 134. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Pinto, P.R.; Mariz-Ponte, N.; Sousa, R.M.O.F.; Torres, A.; Tavares, F.; Ribeiro, A.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Fernandes-Ferreira, M.; Santos, C. Satureja Montana Essential Oil, Zein Nanoparticles and Their Combination as a Biocontrol Strategy to Reduce Bacterial Spot Disease on Tomato Plants. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 584. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Pinto, P.R.; Mariz-Ponte, N.; Gil, R.L.; Cunha, E.; Amorim, C.G.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M.; Fernandes-Ferreira, M.; Sousa, R.M.O.F.; Santos, C. Montmorillonite Nanoclay and Formulation with Satureja Montana Essential Oil as a Tool to Alleviate Xanthomonas Euvesicatoria Load on Solanum Lycopersicum. Applied Nano 2022, 3, 126–142. [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, A.; Ambli, A.; Nagabhushana, B.M. Green and Chemical Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles: An In-Depth Comparative Analysis and Photoluminescence Study. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2024, 40, 101408. [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.Q.; Chu, T. Van; Phan, H.T.; Nguyen, S.V.; Le, T.T.; Tran, D.Q.; Nguyen, H.K.; Vo, A.T.K.; Tran, L.D.; Tran, K.N.; et al. Antifungal Nanoformulation of Botanical Anthraquinone and TiO2 against Melon Phytopathogenic Fungi: Preparation, in Vitro Bioassays and Field Test. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj Napoca 2025, 53, 14108. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J. Preparation and Application of Chitosan/Nano-TiO2/Daisy Essential Oil Composite Films in the Preservation of Actinidia Arguta. Food Chem X 2025, 26, 102303. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, C.; Costa, P.C.; Rodrigues, F. Bioactive Compounds from Actinidia Arguta Fruit as a New Strategy to Fight Glioblastoma. Food Research International 2024, 175, 113770. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, N.; Piwoński, I.; Iqbal, P.; Kisielewska, A. Green Synthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Physicochemical Characterization and Applications: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 5454. [CrossRef]

- Wollenweber, E.; Dörr, M.; Rustaiyan, A.; Roitman, J.N.; Graven, E.H. Notes: Exudate Flavonoids of Some Salvia and a Trichostema Species. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 1992, 47, 782–784. [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri Soltan Meydan, T.; Samareh Moosavi, S.; Sabouri, Z.; Darroudi, M. Green Synthesis of CaCO3 Nanoparticles for Photocatalysis and Cytotoxicity. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2023, 46, 727–734. [CrossRef]

- Nelwamondo, A.M.; Kaningini, A.G.; Ngmenzuma, T.Y.; Maseko, S.T.; Maaza, M.; Mohale, K.C. Biosynthesis of Magnesium Oxide and Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles Using Moringa Oleifera Extract and Their Effectiveness on the Growth, Yield and Photosynthetic Performance of Groundnut (Arachis Hypogaea L.) Genotypes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19419. [CrossRef]

- Frassine, D.; Braglia, R.; Scuderi, F.; Redi, E.L.; Valentini, F.; Relucenti, M.; Colasanti, I.A.; Macchia, A.; Allegrini, I.; Gismondi, A.; et al. Enhancing Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa) Productivity: Foliar Sprayed Fe-Alg-CaCO3 MPs as Fertilizers for Aquaponics Cultivation. Plants 2024, 13, 3416. [CrossRef]

- Valentini, F.; Pallecchi, P.; Relucenti, M.; Donfrancesco, O.; Sottili, G.; Pettiti, I.; Mussi, V. Characterization of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles with Architectural Application for the Consolidation of Pietraforte. Anal Lett 2022, 55, 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Frassine, D.; Braglia, R.; Scuderi, F.; Redi, E.L.; Valentini, F.; Relucenti, M.; Colasanti, I.A.; Zaratti, C.; Macchia, A.; Allegrini, I.; et al. Smart Foliar Fertilizer Based on Zn-Alg-CaCO3 Microparticles Improves Aquaponic Tomato Cultivation. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 18092. [CrossRef]

- Valentini, F.; Bertini, F.; Carbone, M.; Antiochia, R.; Favero, G.; Boaretto, A.; Gazzoli, D. Calcite Nanoparticles as Possible Nano-Fillers for Reinforcing the Plaster of Palazzetto Alessandro Lancia in Rome. European Journal of Science and Theology 2016, 12, 245–259.

- Bicchieri, M.; Valentini, F.; Calcaterra, A.; Talamo, M. Newly Developed Nano-Calcium Carbonate and Nano-Calcium Propanoate for the Deacidification of Library and Archival Materials. J Anal Methods Chem 2017, 2017, 2372789. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, Y.; Fu, N. Free Carboxylic Acids: The Trend of Radical Decarboxylative Functionalization. European J Org Chem 2023, 26, e202300166. [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Singh, M.K.; Han, S.; Ranbhise, J.; Ha, J.; Choe, W.; Yoon, K.S.; Yeo, S.G.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kheamrutai Thamaphat; Limsuwan, P.; Boonlaer Ngotawornchai Phase Characterization of TiO2 Powder by XRD and TEM. Kasetsart Journal (Natural Science) 2008, 42, 357–361.

- You, Y.F.; Xu, C.H.; Xu, S.S.; Cao, S.; Wang, J.P.; Huang, Y.B.; Shi, S.Q. Structural Characterization and Optical Property of TiO2 Powders Prepared by the Sol-Gel Method. Ceram Int 2014, 40, 8659–8666. [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, S.M.; Khedr, T.M.; Zhang, G.; Vogiazi, V.; Ismail, A.A.; O’Shea, K.; Dionysiou, D.D. Tailored Synthesis of Anatase–Brookite Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Degradation of Cylindrospermopsin under UV–Vis Light. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 310, 428–436. [CrossRef]

- Bellardita, M.; Di Paola, A.; Megna, B.; Palmisano, L. Absolute Crystallinity and Photocatalytic Activity of Brookite TiO2 Samples. Appl Catal B 2017, 201, 150–158. [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Mousavi Khoie, S.M.; Liu, K.H. The Role of Brookite in Mechanical Activation of Anatase-to-Rutile Transformation of Nanocrystalline TiO2: An XRD and Raman Spectroscopy Investigation. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 5055–5061. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wu, G.; Guan, N.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Cao, X. Understanding the Effect of Surface/Bulk Defects on the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2: Anatase versus Rutile. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15, 10978–10988. [CrossRef]

- Kandiel, T.A.; Robben, L.; Alkaima, A.; Bahnemann, D. Brookite versus Anatase TiO2 Photocatalysts: Phase Transformations and Photocatalytic Activities. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 2013, 12, 602–609. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Tang, C.; Sun, L. High-Quality Brookite TiO2 Flowers: Synthesis, Characterization, and Dielectric Performance. Cryst Growth Des 2009, 9, 3676–3682. [CrossRef]

- Anjos, O.; Santos, A.J.A.; Paixão, V.; Estevinho, L.M. Physicochemical Characterization of Lavandula Spp. Honey with FT-Raman Spectroscopy. Talanta 2018, 178, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Espina, A.; Sanchez-Cortes, S.; Jurašeková, Z. Vibrational Study (Raman, SERS, and IR) of Plant Gallnut Polyphenols Related to the Fabrication of Iron Gall Inks. Molecules 2022, 27, 279. [CrossRef]

- Minteguiaga, M.; Dellacassa, E.; Iramain, M.A.; Catalán, C.A.N.; Brandán, S.A. FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV–Vis, NMR and Structural Studies of Carquejyl Acetate, a Distinctive Component of the Essential Oil from Baccharis Trimera (Less.) DC. (Asteraceae). J Mol Struct 2019, 1177, 499–510. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Jentzsch, P.; Sandoval Pauker, C.; Zárate Pozo, P.; Sinche Serra, M.; Jácome Camacho, G.; Rueda-Ayala, V.; Garrido, P.; Ramos Guerrero, L.; Ciobotă, V. Raman Spectroscopy in the Detection of Adulterated Essential Oils: The Case of Nonvolatile Adulterants. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2021, 52, 1055–1063. [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, R.; Machado, N.F.L.; Fiuza, S.M.; Gaspar, A.; Garrido, J.; Milhazes, N.; Borges, F.; Marques, M.P.M. Antioxidant Phenolic Esters with Potential Anticancer Activity: A Raman Spectroscopy Study. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2008, 39, 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.; Özkan, G.; Baranska, M.; Krüger, H.; Özcan, M. Characterisation of Essential Oil Plants from Turkey by IR and Raman Spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc 2005, 39, 249–256. [CrossRef]

- Lafhal, S.; Vanloot, P.; Bombarda, I.; Valls, R.; Kister, J.; Dupuy, N. Raman Spectroscopy for Identification and Quantification Analysis of Essential Oil Varieties: A Multivariate Approach Applied to Lavender and Lavandin Essential Oils. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2015, 46, 577–585. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Solana, R.; Daferera, D.J.; Mitsi, C.; Trigas, P.; Polissiou, M.; Tarantilis, P.A. Comparative Chemotype Determination of Lamiaceae Plants by Means of GC-MS, FT-IR, and Dispersive-Raman Spectroscopic Techniques and GC-FID Quantification. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 62, 22–33. [CrossRef]

- Ram Kumar, A.; Selvaraj, S.; Azam, M.; Sheeja Mol, G.; Kanagathara, N.; Alam, M.; Jayaprakash, P. Spectroscopic, Biological, and Topological Insights on Lemonol as a Potential Anticancer Agent. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31548–31566. [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Tinti, A.; Nardi, S. Biological Activity of Vegetal Extracts Containing Phenols on Plant Metabolism. Molecules 2016, 21, 205. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Han, L.; Xu, Y.; Ke, H.; Zhou, N.; Dong, H.; Liu, S.; Qiao, G. Near Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Trioctahedral Chlorites and Its Remote Sensing Application. Open Geosciences 2019, 11, 815–828. [CrossRef]

- Blessymol, B.; Yasotha, P.; Kalaiselvi, V.; Gopi, S. An Antioxidant Study of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles against Mace of Nutmeg in Myristica Fragrans Houtt, Rhizomes of Curcuma Longa Linn and Kaempferia Galanga Extracts. Results Chem 2024, 7, 101291. [CrossRef]

- Pushpamalini, T.; Keerthana, M.; Sangavi, R.; Nagaraj, A.; Kamaraj, P. Comparative Analysis of Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Four Different Leaf Extract. Mater Today Proc 2021, 40, S180–S184. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, O.; Jafarizadeh-Malmiri, H. Intensification Process in Thyme Essential Oil Nanoemulsion Preparation Based on Subcritical Water as Green Solvent and Six Different Emulsifiers. Green Processing and Synthesis 2021, 10, 430–439. [CrossRef]

- Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Ristivojevic, P.; Gegechkori, V.; Litvinova, T.M.; Morton, D.W. Essential Oil Quality and Purity Evaluation via Ft-Ir Spectroscopy and Pattern Recognition Techniques. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2020, 10, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, R.A.; El-Borady, O.M.; El-Sayed, A.F.; Fawzy, M. A Comparative Study of Chemo- and Phytosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Ceratophyllum Demersum Extract: Characterization and Biological Activities. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025. [CrossRef]

- Falcioni, R.; Moriwaki, T.; Gibin, M.S.; Vollmann, A.; Pattaro, M.C.; Giacomelli, M.E.; Sato, F.; Nanni, M.R.; Antunes, W.C. Classification and Prediction by Pigment Content in Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.) Varieties Using Machine Learning and ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. Plants 2022, 11, 3413. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds; 7th Editio.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, United States, 2005; ISBN 1118311655.

- Juhasz-Bortuzzo, J.A.; Myszka, B.; Silva, R.; Boccaccini, A.R. Sonosynthesis of Vaterite-Type Calcium Carbonate. Cryst Growth Des 2017, 17, 2351–2356. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.T.; Yu, J.C.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, L.Z. Sonochemical Synthesis of Aragonite-Type Calcium Carbonate with Different Morphologies. New Journal of Chemistry 2004, 28, 1027–1031. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, V.; Anand, P.; Suresh, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Polymer-Mediated CaCO3 Nanoparticles Using Limestone: A Novel Approach. Advanced Powder Technology 2018, 29, 818–834. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.K.; Pradhan, G.C.; Dash, S.; Mohanty, F.; Behera, L. Preparation and Characterization of Bionanocomposites Based on Soluble Starch/Nano CaCO3. Polym Compos 2018, 39, E82–E89. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Caumon, M.C.; Barres, O.; Sall, A.; Cauzid, J. Identification and Composition of Carbonate Minerals of the Calcite Structure by Raman and Infrared Spectroscopies Using Portable Devices. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2021, 261, 119980. [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.F.; Edwards, H.G.M.; Korsakov, A.; de Oliveira, L.F.C. Revisiting the Raman Spectra of Carbonate Minerals. Minerals 2023, 13, 1358. [CrossRef]

- Legodi, M.A.; De Waal, D.; Potgieter, J.H. Quantitative Determination of CaCO3 in Cement Blends by FT-IR. Appl Spectrosc 2001, 55, 361–365. [CrossRef]

- Vagenas, N. V.; Gatsouli, A.; Kontoyannis, C.G. Quantitative Analysis of Synthetic Calcium Carbonate Polymorphs Using FT-IR Spectroscopy. Talanta 2003, 59, 831–836. [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, A.; Di Marco, G.; Redi, E.L.; Ferrucci, L.; Cantonetti, M.; Canini, A. The Antimicrobial Activity of Lavandula Angustifolia Mill. Essential Oil against Staphylococcus Species in a Hospital Environment. J Herb Med 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, T.; Rajendran, S.; Natarajan, S.; Vinayagam, S.; Rajamohan, R.; Lackner, M. Environmental Fate and Transformation of TiO2 Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Assessment. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2025, 115, 264–276.

- Khalaf Kenawe, L.; Abbas, R.S.; Kadhim, A.S. Comparative Study of Alcohol Clove Extract, TiO2 Nanoparticles, and Clove Extract-TiO2 Complex in Controlling Bacterial Growth in Burn Infections. Microbes and Infectious Diseases 2025, 6, 680–688. [CrossRef]

- Fletes-Vargas, G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; Pinto, N.V.; Kato, K.C.; Carneiro, G.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Rodrigues-Martins, H.; Espinosa-Andrews, H. TiO2 Nanoparticles Loaded with Polygonum Cuspidatum Extract for Wound Healing Applications: Exploring Their Hemolytic, Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, and Antimicrobial Properties. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 926. [CrossRef]

- Al-darwesh, M.Y.; Babakr, K.A.; Qader, I.N.; Mohammed, M.A. Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Potential of Green Synthesis TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Sophora Flavescens Root Extract. Chemical Papers 2025, 79, 1207–1221. [CrossRef]

- Raj, L.F.A.A.; Annushrie, A.; Namasivayam, S.K.R. Anti Bacterial Efficacy of Photo Catalytic Active Titanium Di Oxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles Synthesized via Green Science Principles against Food Spoilage Pathogenic Bacteria. Microbe (Netherlands) 2025, 7. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.R.; Kaewgun, S.; Lee, B.I.; Tzeng, T.R.J. The Antibacterial Effects of Biphasic Brookite-Anatase Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Multiple-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. In Proceedings of the Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology; September 2008; Vol. 4, pp. 339–348.

- Delgado, L.P.; Figueroa-Torres, M.Z.; Ceballos-Chuc, M.C.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Alvarado-Gil, J.J.; Oskam, G.; Rodriguez-Gattorno, G. “Tailoring the TiO2 Phases through Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Synthesis: Comparative Assessment of Bactericidal Activity.” Materials Science and Engineering C 2020, 117. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dabbs, D.M.; Liu, L.M.; Aksay, I.A.; Car, R.; Selloni, A. Combined Effects of Functional Groups, Lattice Defects, and Edges in the Infrared Spectra of Graphene Oxide. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 18167–18176. [CrossRef]

- Nguyet Nga, D.T.; Le Nhat Trang, N.; Hoang, V.T.; Ngo, X.D.; Nhung, P.T.; Tri, D.Q.; Cuong, N.D.; Tuan, P.A.; Huy, T.Q.; Le, A.T. Elucidating the Roles of Oxygen Functional Groups and Defect Density of Electrochemically Exfoliated GO on the Kinetic Parameters towards Furazolidone Detection. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 27855–27867. [CrossRef]

- Mardente, S.; Aventaggiato, M.; Splendiani, E.; Mari, E.; Zicari, A.; Catanzaro, G.; Po, A.; Coppola, L.; Tafani, M. Extra-Cellular Vesicles Derived from Thyroid Cancer Cells Promote the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and the Transfer of Malignant Phenotypes through Immune Mediated Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liao, D.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Tong, Z.; Lai, L.; Sun, L.; Zhou, G. Hollow Calcium Carbonate Microspheres Prepared from Waste Eggshells as PH-Responsive Controlled-Release Carvacrol for Efficient and Safe Antimicrobial Agents in Pork Preservation. Food Control 2025, 176. [CrossRef]

- Koley, R.; Mandal, M.; Mondal, A.; Debnath, P.; Mondal, A.; Mondal, N.K. Synthesis of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles from Mollusc Shell Waste and Its Efficacy towards Plant Growth and Development. Sustainable Chemistry One World 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Motlhalamme, T.; Mohamed, H.; Kaningini, A.G.; More, G.K.; Thema, F.T.; Mohale, K.C.; Maaza, M. Bio-Synthesized Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticles: Their Anti-Fungal Properties and Application as Nanofertilizer on Lycopersicon Esculentum Growth and Gas Exchange Measurements. Plant Nano Biology 2023, 6, 100050. [CrossRef]

- Motlhalamme, T.; Kaningini, A.G.; Thema, F.T.; Mohale, K.C.; Maaza, M. Nanotechnology in Agriculture: Exploring the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles on Tomato Leaf and Fruit Metabolomic Profiles. South African Journal of Botany 2025, 180, 615–624. [CrossRef]

- Wesolowska, A.; Grzeszczuk, M.; Jadczak, D. Influence of Harvest Term on the Content of Carvacrol, p-Cymene, Î3-Terpinene and Î2-Caryophyllene in the Essential Oil of Satureja Montana. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj Napoca 2014, 42, 392–397. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Matos, O.; Teixeira, B.; Ramos, C.; Neng, N.; Nogueira, J.; Nunes, M.L.; Marques, A. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Satureja Montana L. Extracts. J Sci Food Agric 2011, 91, 1554–1560. [CrossRef]

- Aravind, M.; Amalanathan, M.; Mary, M. Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles by Chemical and Green Synthesis Methods and Their Multifaceted Properties. SN Appl Sci 2021, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Bahrom, H.; Goncharenko, A.A.; Fatkhutdinova, L.I.; Peltek, O.O.; Muslimov, A.R.; Koval, O.Y.; Eliseev, I.E.; Manchev, A.; Gorin, D.; Shishkin, I.I.; et al. Controllable Synthesis of Calcium Carbonate with Different Geometry: Comprehensive Analysis of Particle Formation, Cellular Uptake, and Biocompatibility. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2019, 7, 19142–19156. [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Kumari, M.; Kumar, M.; Dhiman, S.; Garg, R. Green Synthesis of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles Using Waste Fruit Peel Extract. Mater Today Proc 2021, 46, 6665–6668. [CrossRef]

- Correr, S.; Makabe, S.; Heyn, R.; Relucenti, M.; Naguro, T.; Familiari, G. Microplicae-like Structures of the Fallopian Tube in Postmenopausal Women as Shown by Electron Microscopy. Histol Histopathol 2006, 21, 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Relucenti, M.; Heyn, R.; Correr, S.; Familiari, G. Cumulus Oophorus Extracellular Matrix in the Human Oocyte: A Role for Adhesive Proteins. In Proceedings of the Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology; 2005; Vol. 110, pp. 219–224.

- Relucenti, M.; Heyn, R.; Petruzziello, L.; Pugliese, G.; Taurino, M.; Familiari, G. Detecting Microcalcifications in Atherosclerotic Plaques by a Simple Trichromic Staining Method for Epoxy Embedded Carotid Endarterectomies. European Journal of Histochemistry 2010, 54, 143–147. [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, G.; Relucenti, M.; Iaculli, F.; Salucci, A.; Donfrancesco, O.; Polimeni, A.; Bossù, M. The Application of a Fluoride-and-Vitamin D Solution to Deciduous Teeth Promotes Formation of Persistent Mineral Crystals: A Morphological Ex-Vivo Study. Materials 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bossù, M.; Matassa, R.; Relucenti, M.; Iaculli, F.; Salucci, A.; Di Giorgio, G.; Familiari, G.; Polimeni, A.; Di Carlo, S. Morpho-Chemical Observations of Human Deciduous Teeth Enamel in Response to Biomimetic Toothpastes Treatment. Materials 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Viani, I.; Colucci, M.E.; Pergreffi, M.; Rossi, D.; Veronesi, L.; Bizzarro, A.; Capobianco, E.; Affanni, P.; Zoni, R.; Saccani, E.; et al. Passive Air Sampling: The Use of the Index of Microbial Air Contamination. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91, 92–105. [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Pitzurra, O.; Savino, A. The Index of Microbial Air Contamination. Journal of Hospital Infection 2000, 46, 241–256.

| Band (cm−1) | Assignment | Reference |

| RAMAN SPECTROSCOPY | ||

| 248 | Eg lattice mode (calcite) τ+δ aromatic ring |

[96,97] |

| 320 | τ aromatic ring | [74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 412 | δop+τ aromatic ring | [74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 507 | δop +τ aromatic ring | [74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 626 | δop +τ aromatic ring | [74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 718 | Eg mode (δipCO32−) (calcite) | [96,97] |

| 746 | νC–C δC–O δ aromatic ring |

[74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 890 | νC–OH νC–C δCH/CH2 |

[74,75,76,77,78,82] |

| 1009 | δipCH νC–O δ aromatic skeletal |

[75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

| 1092 | A1g mode (νsCO32−) (calcite) | [96,97] |

| 1180 | δCH νC–O δ aromatic skeletal |

[74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] |

| 1339 | δCH3 (isopropyl) δCH2 |

[74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] |

| FTIR-ATR SPECTROSCOPY | ||

| 3600-3000 | νO–H | [88,89,90,91] |

| 2951 | νas –CH3 | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| 2922 | νas –CH2 | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| 2856 | νs –CH2 | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| 1710 | νC=O | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| 1637 | δO–H νC=O νC=C |

[87,88,89,90,91] |

| 1404 | νasCO32− (calcite) | [98,99] |

| 1231 | νC–O νC–C δ aromatic skeletal |

[87,88,89,90,91] |

| 1070 | νC–O νC–C δ aromatic skeletal |

[87,88,89,90,91] |

| 870 | δopCO32− (calcite) | [98,99] |

| 705 | δipCO32− (calcite) | [98,99] |

| Compound |

Concentration [ng/ml] |

| α-Thujone | 282 |

| α-pinene | n.d. |

| Camphene | n.d. |

| Sabinene | 1054 |

| β-Pinene | n.d. |

| α-Phellandrene | 264 |

| α-Terpinene | 3814 |

| para-cymene | 157 |

| (R)-(+)-Limonene | 535 |

| α-Terpinolene | 284 |

| γ-Terpinene | 882 |

| Terpinen 4-ol | 10305 |

| Carvacrol methyl ether | 23.4 |

| L-Carvone | n.d. |

| Thymoquinone | 8271. |

| Geraniol | n.d. |

| Thymol | 63906 |

| Carvacrol | 5669 |

| β-Caryophyllene | n.d. |

| α-Humulene | 4.0 |

| caryophyllene oxide | 135 |

| cis-α-bisabolene (Levomenol) | 4.7 |

| L-Linalool | 1425 |

| aromadendrene oxide 2 | n.d. |

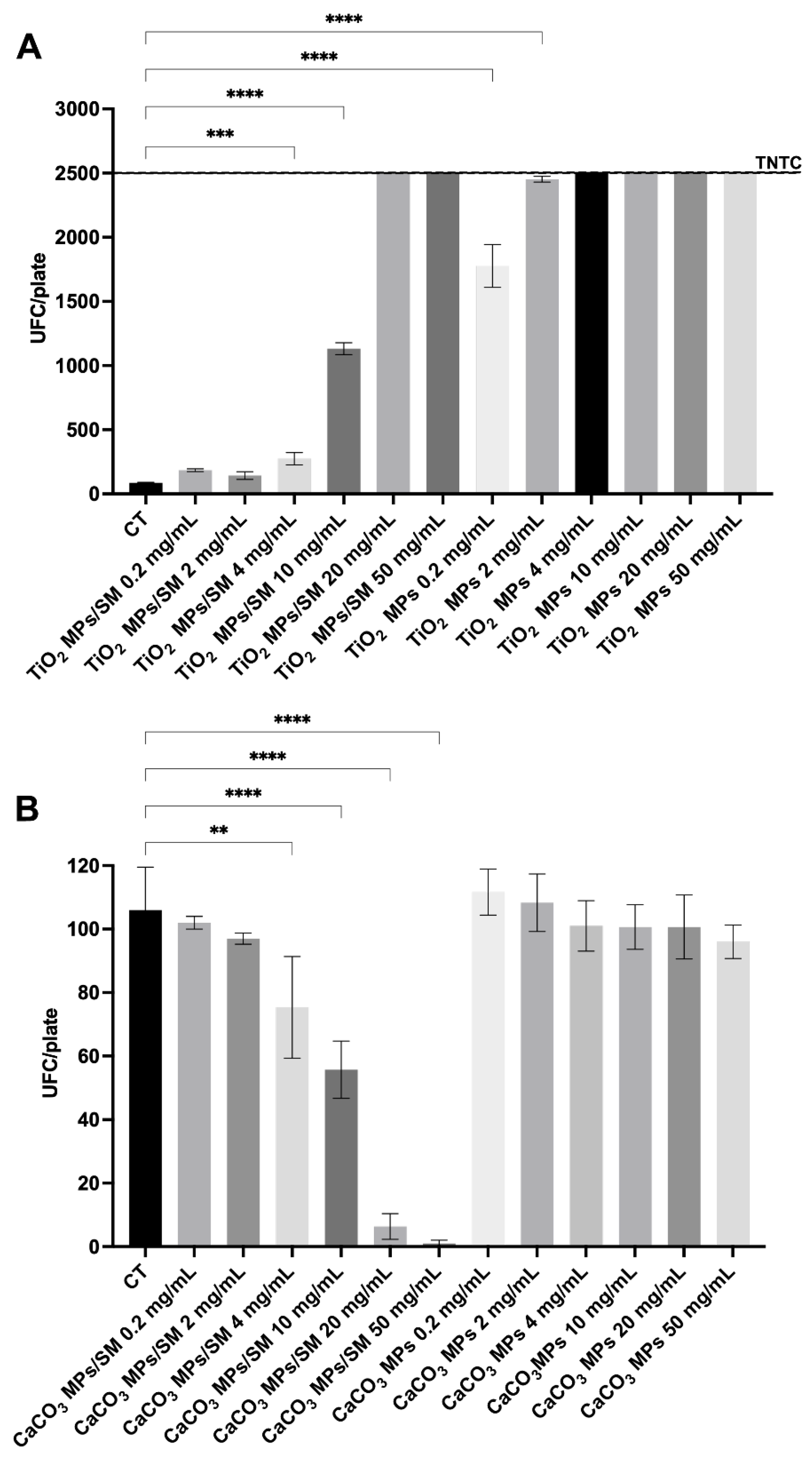

| Treatment | Concentration (mg/mL) | CFU/plate |

MPs Size _SEM (nm/µm) |

| Titanium Oxide | |||

| CT | - | 86.00 ± 3.60 | Diameters ranging from 160 nm to 1.3 µm, with a prevalence of elements with diameters around 400-600 nm |

| TiO2 MPs/SM | 0.2 | 184.00 ± 10.58 | |

| 2 | 142.40 ± 29.70 | ||

| 4 | 274.00 ± 47.62 *** | ||

| 10 | 1132.00 ± 46.13 **** | ||

| 20 | >2500 | ||

| 50 | >2500 | ||

| TiO2 MPs | 0.2 | 1776.00 ± 166.40 **** | |

| 2 | 2452.00 ± 22.27 **** | ||

| 4 | >2500 | ||

| 10 | >2500 | ||

| 20 | >2500 | ||

| 50 | >2500 | ||

| Calcium Carbonate | |||

| CT | - | 106.00 ± 13.53 |

CaCO3 particles have prismatic shape, sharp edges and variable size, with an average of 1 µm x 1 µm x 1 µm |

| CaCO3 MPs/SM | 0.2 | 102.00 ± 2.00 | |

| 2 | 97.00 ± 1.73 | ||

| 4 | 75.33 ± 16.04 ** | ||

| 10 | 55.67 ± 9.02 **** | ||

| 20 | 6.33 ± 4.04 **** | ||

| 50 | 1.00 ± 1.00 **** | ||

| CaCO3 MPs | 0.2 | 111.7 ± 7.23 | |

| 2 | 108.3 ± 9.07 | ||

| 4 | 101.00 ± 7.93 | ||

| 10 | 100.70 ± 7.02 | ||

| 20 | 100.70 ± 10.07 | ||

| 50 | 96.00 ± 5.29 | ||

| Samples |

SEM (φ: nm) Shape |

XRD 2θ (plane) |

Raman cm-1 (mode) |

SM extract composition (GC-MS) |

References | Notes |

| TiO2 MPs/SM | 400 – 600 nm µ-Spheres |

11.74° (101)/A 17.45° (112)/A 21.77° (200)/A 24.60° (211)/A 27.91° (204)/A 30.54° (220)/A 32.90° (301)/A 35.63° (312)/A 11.74° (111) /B 21.77° (231)/B |

(146, 219, 623) Eg/A (411, 517) B1g/A (517) A1g/A (219) B1g/B (279) B2g/B |

α-Thujone α-pinene Camphene Sabinene β-Pinene α-Phellandrene alfaTerpinene para-cymene (R)-(+)-Limonene α-Terpinolene γ-Terpinene Terpinen 4-ol Carvacrol methyl ether L-Carvone Thymoquinone Geraniol Thymol Carvacrol β-Caryophyllene α-Humulene caryophyllene oxide cis-α-bisabolene (Levomenol) L-Linalool |

This work (2025) | No antimicrobial performances have been observed |

| Anatase and rutile film |

600 nm size, grain size: 100 nm film |

The anatase films appear as flat terraces with mono-atomic steps. The ‘grains’ have a slightly rectangular shape and two kinds of rectangular grains oriented 90 to each other are observed. These are due to the before mentioned twinning of the films |

Not reported in the text | Not reported in the text | [101] | Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy activity against Methicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus |

| TiO2 NPs/ clove extract | 19-33 nm Spheres |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported for the clove extract | [102] | Alcohol-based clove extract combined with TiO2 nanoparticles is a potent antimicrobial agent, capable of inhibiting VMRSA growth even at low concentrations |

| TiO2 NPs from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA) Loaded with Polygonum cuspidatum Extract | 21 nm (as reported by Sigma Aldrich) Spheres |

Not reported in the article, where commercially available nanoparticles have been applied | Not reported in the article, where commercially available nanoparticles have been applied | Not reported for the Polygonum cuspidatum Extract | [103] | Incorporating P. cuspidatum root extract into TiO2 nanoparticles significantly enhances their antioxidant and hemocompatibility properties. TiO2-loaded extract NPs exhibited excellent antibacterial properties against the tested strains |

| Green synthesis TiO2 nanoparticles using Sophora flavescens root extract |

8-24 nm Spheres |

(100) A (004) A (204) A (105) A (211) A (204) A |

Not reported only FTIR | Not reported for the Sophora flavescens root extract | [104] | Their stability and ability to penetrate bacteria cells enhance their antibacterial efficacy, particularly against gram-positive bacteria |

| TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized using Talinum fruticosum leaf extract |

3-12 nm Spheres |

24.92° (101) A 68.99° (200) R |

Not reported only FTIR | Not reported for the Talinum fruticosum leaf extract | [105] | TiO2 showed photocatalytic activity and anti-inflammatory property as the protein degradation inhibition capacity |

| TiO2 P25 TiO2 Br200 |

mean diameter of 40 nm 10-15 nm |

79 % anatase/A 21% rutile/ R 45% anatase/A 2% rutile/R 53% brookite/B |

Not reported | No plant extract was applied for the synthesis of these nanoparticles | [106] | Biphasic brookite-anatase nanoparticles, due to their smaller particle size, may increase the efficiency of TiO2 nanoparticles to inhibit bacterial growth by promoting a greater surface area contact ratio |

|

TiO2, anatase, brookite and rutile, have been synthetized through a microwave-assisted hydrothermal method using amorphous TiO2 as a common precursor |

2000 nm amorphous (spheres) 15 nm A (spheres) 20 nm Degussa P25 (spheres) 20 nm B (spheres) 20 nm R rod-shaped |

Degussa P25 (80% anatase and 20% rutile), A (100% purity) B (94% purity) R (100% purity) |

(144, 196, 639 cm−1) Eg/A (399, 519 cm−1) B1g/A (513 cm−1) /A (127, 154, 194, 247, 412, 640 cm−1), A1g/B (133, 159, 215, 320, 415, 502 cm−1) B1g/B (235, 450 cm-1) /R |

TiO2 without functionalization, as reported in the full text | [107] | The bactericidal activity and photocatalytic antibacterial effectiveness of each material were evaluated through the determination of the minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations, and via the mortality kinetic method under ultraviolet (UV) illumination under similar conditions with two bacterial groups of unique cellular structures: Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). |

| Samples |

SEM (φ: nm) Shape |

XRD 2θ (plane) |

Raman cm-1 (mode) |

SM extract composition (GC-MS) |

References | Notes |

| CaCO3 MPs/SM | 1 µm x 1 µm x 1 µm Prismatic shape |

29.43° (104) /C 31.46° /C 56.54° /C 58.20° /C |

248 cm−1 (Eg) C lattice 718 cm−1 (Eg) C 1092 cm−1 (A1g) C |

α-Thujone α-pinene Camphene Sabinene β-Pinene α-Phellandrene alfaTerpinene para-cymene (R)-(+)-Limonene α-Terpinolene γ-Terpinene Terpinen 4-ol Carvacrol methyl ether L-Carvone Thymoquinone Geraniol Thymol Carvacrol β-Caryophyllene α-Humulene caryophyllene oxide cis-α-bisabolene (Levomenol) L-Linalool |

This work (2025) |

CaCO3 MPs/SM exhibit antimicrobial properties, depending on the particle concentrations, shape, defects, edges, dislocations and density of oxygenated functionalities on edges |

| Hollow calcium carbonate microspheres loaded by carvacrol | 1.97 ± 0.61 μm hollow microspheres |

XRD analysis of the CaCO3 hollow microspheres revealed that they are primarily aragonite (standard card: JCPDS#33–0268) | Not reported in the text | Not reported in the text for the carvacrol loading | [111] | The antimicrobial results indicated that microSCaCA effectively inhibited and killed E. coli and S. aureus, markedly enhancing the efficacy of CA, and exhibiting cellular safety. In practical preservation applications, microSCaCA significantly improved the preservation of pork during 4 ◦C storage, inhibiting key indicators such as TVB-N, pH, TBARS, and TVC, effectively delaying the oxidation of fats and proteins and suppressing the growth of microorganisms during the storage period |

| CaCO3 nanoparticles have been synthetized by using dried powder of mollusc shells |

60-70 nm spheres |

23.1◦ (012) 29.3◦ (104) 31.4° (006) 35.9◦ (110) 39.4◦ (113) 42.7◦ (202) 47.5◦ (018) 48.5◦ (116) 57.4◦ (122) 60.7◦ (214) 64.4◦ (300) 65.4◦ (0012) (JCPDS No. 85–1108) |

Not reported in the text but only FTIR | The synthesis of calcium carbonate nanoparticles from mollusk shell waste occurred without any natural plant extracts. Therefore, this characterization is not specifically contemplated in the text. | [112] | A low level of oxidative stress was recorded under all treatments of CaCO3NPs, and the highest decrease in MDA and O2•- contents of about 12 % and 23 % were recorded under 30 mg/L of CaCO3NPs compared to the control, respectively. The antioxidant system was improved under CaCO3NPs treatments and the highest increase of about 22 % and 37 % in CAT and SOD activity were recorded at 30 mg/L of CaCO3NPs compared to the control, respectively. |

| The extract of Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart (Egyptian doum palm) fruits was used as the reducing/capping agent for the synthesis of CaCO3 nanoparticles |

60 nm - 180 nm shapes from quasi-spherical, to cubical with equiaxed morphology |

012 104 110 113 202, 018, 116 211 122 214 300 correspond to the rhombohedral calcite phase of CaCO3, which is following with the X-pert standard card #47–1743 |

Not reported in the text but only FTIR | Not reported in the text for the extract of Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart (Egyptian doum palm) fruits |

[113] | CaCO3 NPs exhibit antifungal activity and therefore, the findings of this study suggest that the inclusion of a green synthesis of CaCO3 NPs as a nonfertilizer has the potential to promote tomato growth and yield. |

| The extract of Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart (Egyptian doum palm) fruits was used as the reducing/capping agent for the synthesis of CaCO3 nanoparticles |

60 nm - 180 nm shapes from quasi-spherical, to cubical with equiaxed morphology |

012 104 110 113 202, 018, 116 211 122 214 300 correspond to the rhombohedral calcite phase of CaCO3, which is following with the X-pert standard card #47–1743 |

Not reported | Not reported for the extract of Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart (Egyptian doum palm) fruits. This investigation has been reported only for the metabolomes of both tomato cultivars (Heinz-1370andMoneymaker), before and after CaCO3 NPs inoculation/treatments. |

[114] | The application of CaCO3NPs increased the presence of terpenoids and flavonoids in both fruits and leaves compared with the untreated plants. Metabolites such as 13-hydroxy abscisic acid, Dantaxusin A, and Sinuatol were identified in the leaves of the Moneymaker cultivar, with 30-O-linolenoylglyceryl6-O-galactopyranosyl-galactopyranoside, Olean-12-en-28-oic acid and scutianthraquinone B present in the fruits. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).