Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

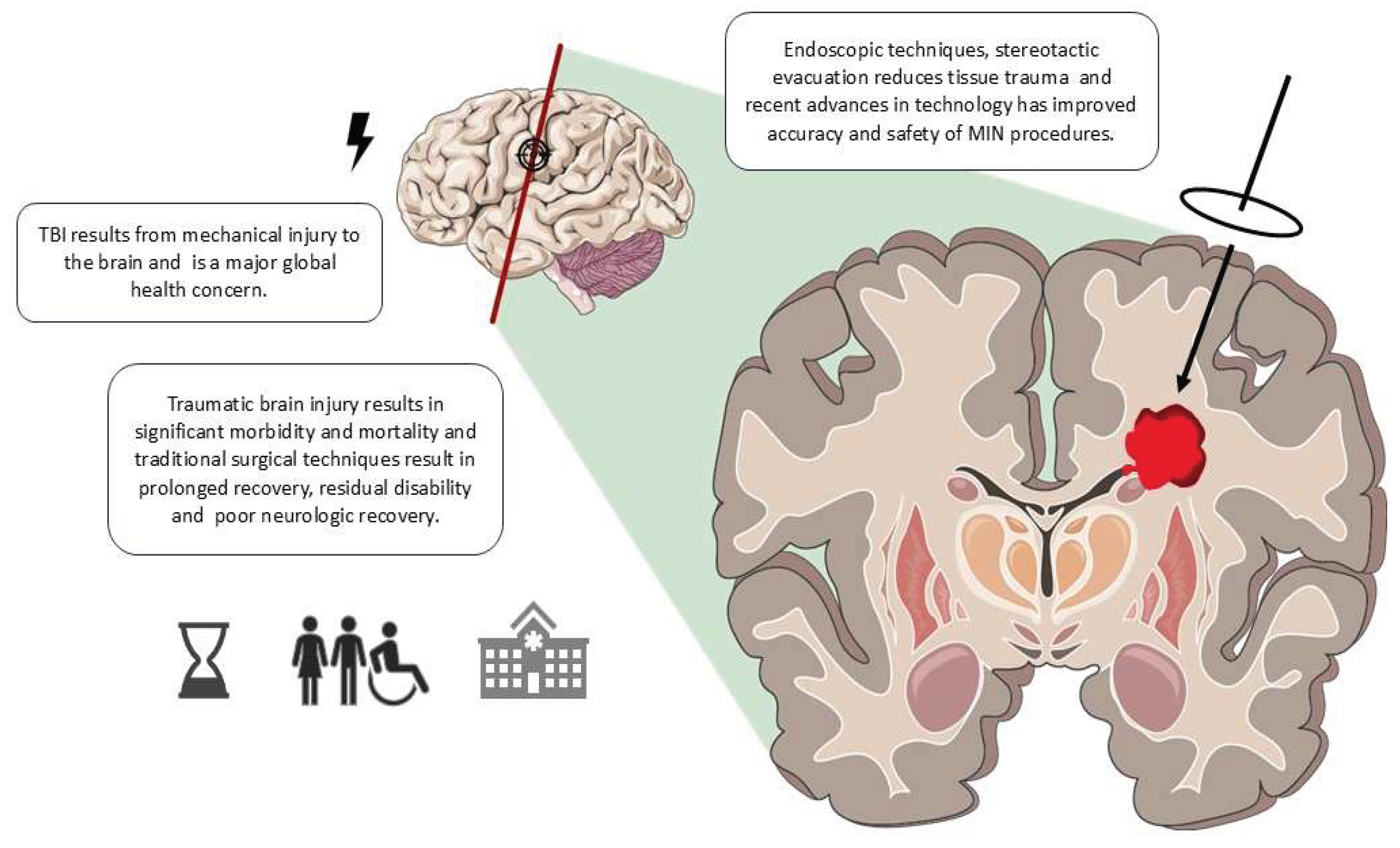

1. Introduction

2. MIN Techniques in TBI

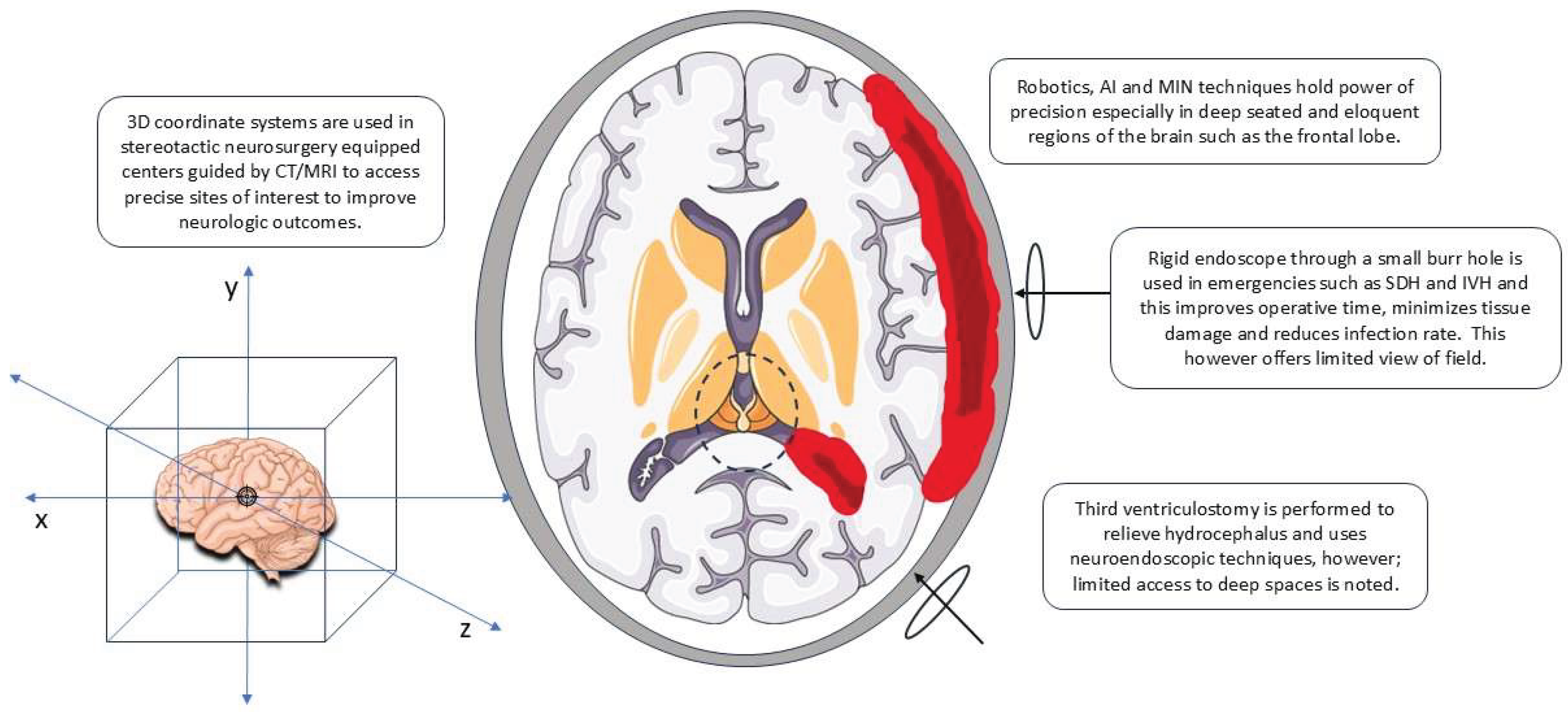

2.1. Overview of Techniques

2.2. Technological Innovations

3. Neurological Outcomes of MIN

3.1. Short-Term Outcomes

3.2. Long-Term Outcomes

3.3. Comparative Analysis

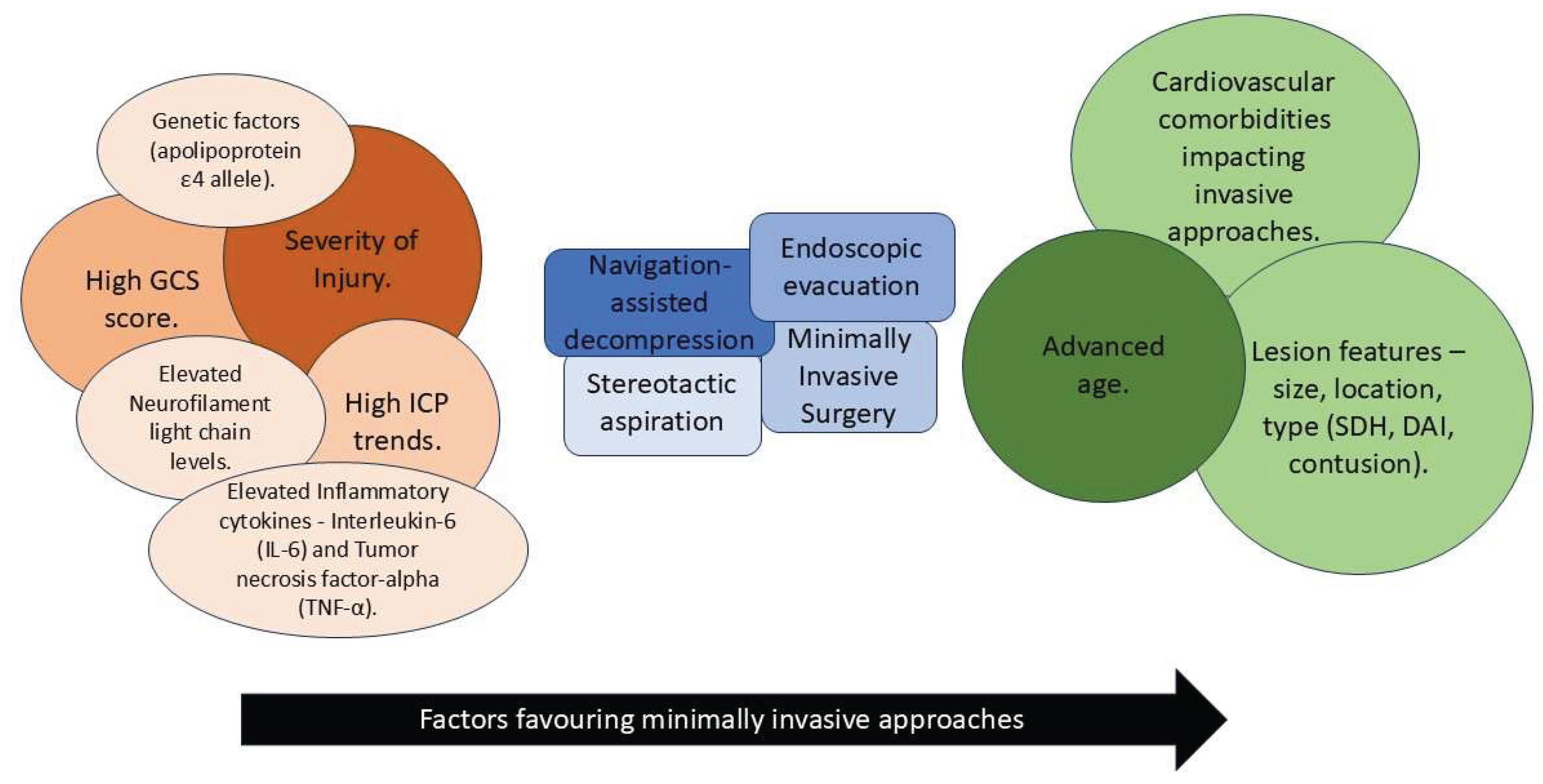

4. Factors Influencing Neurological Outcomes

4.1. Patient-Related Factors

4.2. Injury-Related Factors

4.3. Intervention-Related Factors

4.4. Post-Interventional Care

4.5. Other Factors

5. Integration of Neurology and Neurosurgery in Patient Care

5.1. Multidisciplinary Approaches

5.2. Importance of Continuous Monitoring

6. Personalized Medicine in Neurosurgery for TBI

6.1. Tailoring Surgical Approaches to Individual Patients

6.2. Future Trends in Personalized Neurosurgery

7. Neuroplasticity and Recovery Post-Surgery

7.1. Role of Neuroplasticity in TBI Recovery

7.2. Rehabilitation Strategies to Enhance Neuroplasticity

8. Role of Neuroimaging in Assessing Surgical Outcomes

8.1. Preoperative Neuroimaging

8.2. Postoperative Neuroimaging

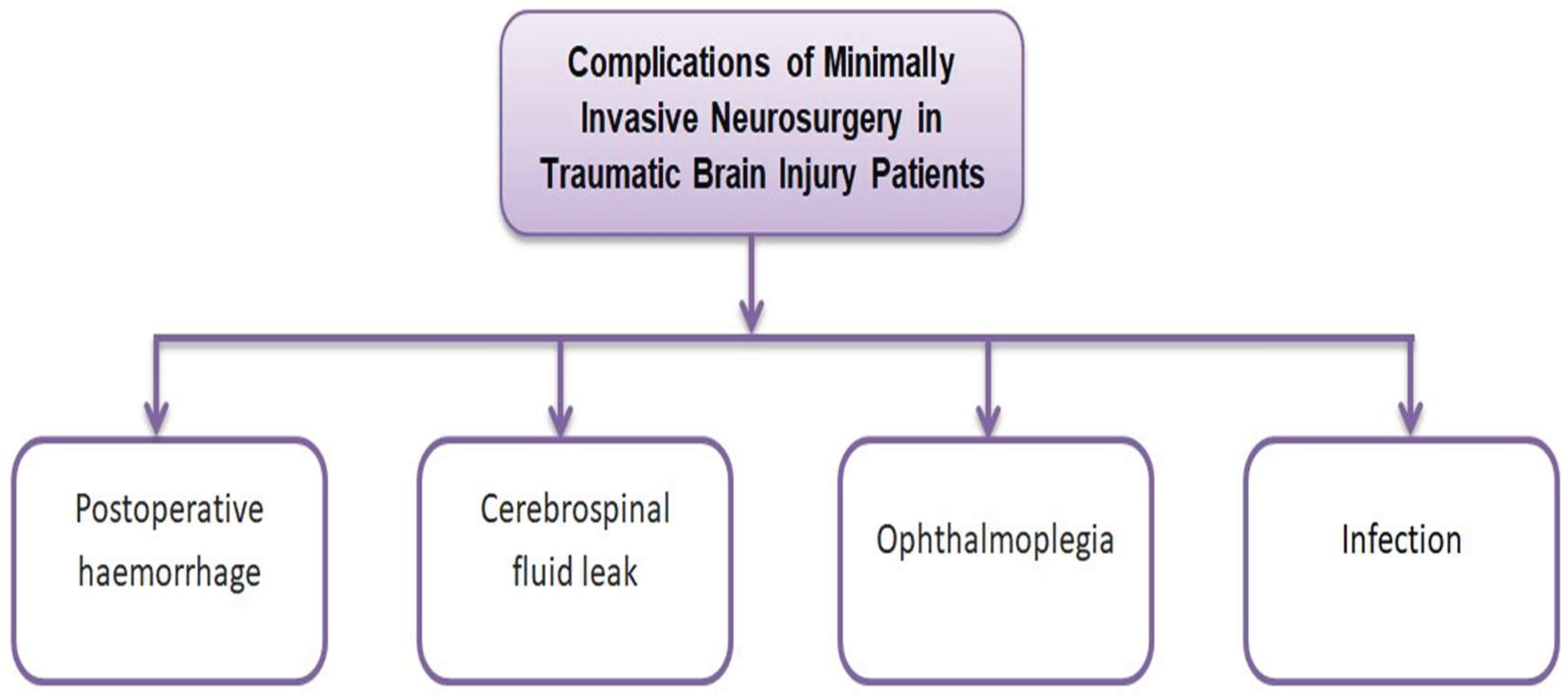

9. Complications and Risk Management in MIN

9.1. Common Complications

9.2. Strategies for Risk Management

10. Patient-Centered Outcomes and QoL

10.1. Assessing QoL Post-Surgery

10.2. Patient Satisfaction and Experience

11. Future Directions

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DAI | Diffuse axonal injury |

| DBS | Deep brain stimulation |

| DC | Decompressive craniectomy |

| DCX | Doublecortin |

| DRS | Disability rating scale |

| DTI | Diffusion tensor imaging |

| ED | Emergency department |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EVD | External ventricular drainage |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| GCS | Glasgow coma scale |

| GDNF | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GOS | Glasgow outcome scale |

| GOSE | Glasgow outcome scale–extended |

| ICES | Intraoperative stereotactic computed tomography-guided endoscopic surgery |

| ICH | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| ICP | Intracranial pressure |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IL | Interlekin |

| IVH | Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| MARI | Micro-angio-resection-interface |

| MAO | Monoamine oxidase |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MIN | Minimally invasive neurosurgery |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRS | Modified Rankin scale |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| PCV | Percutaneous computed tomography-controlled ventriculostomy |

| PEG | Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| SDH | Subdural hemorrhage |

| SEEG | Stereo electroencephalography |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| TRACK-TBI | Transforming research and clinical knowledge in traumatic brain injury |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| US | United States |

References

- Timofeev, I.; Santarius, T.; Kolias, A.G.; Hutchinson, P.J.A. Decompressive Craniectomy - Operative Technique and Perioperative Care. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg 2012, 38, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, M.; Coronado, V. Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Handb Clin Neurol 2015, 127, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global, Regional, and National Burden of Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury, 1990-2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18, 56–87. [CrossRef]

- Invited Commentary on “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Report to Congress: Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation”.; United States, 2015; Vol. 96;

- Masel, B.E.; DeWitt, D.S. Traumatic Brain Injury: A Disease Process, Not an Event. J Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaloshnja, E.; Miller, T.; Langlois, J.A.; Selassie, A.W. Prevalence of Long-Term Disability from Traumatic Brain Injury in the Civilian Population of the United States, 2005. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2008, 23, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment and Prognosis of Coma after Head Injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1976, 34, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.V.; Maas, A.I.; Bragge, P.; Morganti-Kossmann, M.C.; Manley, G.T.; Gruen, R.L. Early Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Lancet 2012, 380, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Adelson, P.D.; Andelic, N.; Bell, M.J.; Belli, A.; Bragge, P.; Brazinova, A.; Büki, A.; Chesnut, R.M.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury: Integrated Approaches to Improve Prevention, Clinical Care, and Research. Lancet Neurol 2017, 16, 987–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, I.W.; Bennett, J.D.; Stein, D.M. Rapid Detection of Significant Traumatic Brain Injury Requiring Emergency Intervention. Am Surg 2021, 87, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccilli, B.; Alan, A.; Aljeradat, B.G.; Shahzad, A.; Almealawy, Y.F.; Chisvo, N.S.; Ennabe, M.; Weinand, M. Neuroprotection: Surgical Approaches in Traumatic Brain Injury. Surg Neurol Int 2024, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamat, A.S.; Parker, A. The Evolution of Neurosurgery: How Has Our Practice Changed? Br J Neurosurg 2013, 27, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, K.B. Harvey William Cushing: The Father of Modern Neurosurgery (1869-1939). Neurol India 2016, 64, 1125–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikova, A.; Birbilis, T. The Basic Steps of Evolution of Brain Surgery. Maedica (Bucur) 2017, 12, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, S. Robot Assisted Stereotactic Surgery Improves Hematoma Evacuation in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Compared to Frame Based Method. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 12427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darzi, S.A.; Munz, Y. The Impact of Minimally Invasive Surgical Techniques. Annu Rev Med 2004, 55, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, K.; Nonaka, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Horio, Y.; Abe, H.; Morishita, T.; Iwaasa, M.; Inoue, T. Optimal Surgical Indications of Endoscopic Surgery for Traumatic Acute Subdural Hematoma in Elderly Patients Based on a Single-Institution Experience. Neurosurg Rev 2021, 44, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas, O.; Karadereler, S.; Bahar, S.; Yesilot, N.; Krespi, Y.; Solmaz, B.; Bayindir, O. Image-Guided Keyhole Evacuation of Spontaneous Supratentorial Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2009, 52, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.J.; Manivannan, S.; Zaben, M. Endoscope-Assisted Techniques for Evacuation of Acute Subdural Haematoma in the Elderly: The Lesser of Two Evils? A Scoping Review of the Literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2021, 207, 106712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, W.-L.; Kuo, L.-T.; Chen, C.-M.; Yang, S.-H.; Tang, C.-T.; Lai, D.-M.; Huang, A.P.-H. Surgical Application of Endoscopic-Assisted Minimally-Invasive Neurosurgery to Traumatic Brain Injury: Case Series and Review of Literature. J Formos Med Assoc 2022, 121, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarigul, B.; De Macêdo Filho, L.J.; Hawryluk, G.W. Invasive Monitoring in Traumatic Brain Injury. Current Surgery Reports 2022, 10, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.N.G.; Amorim, R.L.; Mandel, M.; do Espírito Santo, M.P.; Paiva, W.S.; Andrade, A.F.; Teixeira, M.J. Endoscopic-Assisted Removal of Traumatic Brain Hemorrhage: Case Report and Technical Note. J Surg Case Rep 2015, 2015, rjv132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadhavekar, N.H.; Sabzvari, T.; Laguardia, S.; Sheik, T.; Prakash, V.; Gupta, A.; Umesh, I.D.; Singla, A.; Koradia, I.; Ramirez Patiño, B.B.; et al. Advancements in Imaging and Neurosurgical Techniques for Brain Tumor Resection: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e72745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockett, W.S.; Cockett, A.T. The Hopkins Rod-Lens System and the Storz Cold Light Illumination System. Urology 1998, 51, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, L.M.; Holzer, P.; Ascher, P.W.; Heppner, F. Endoscopic Neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1988, 90, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, H.B. Technique of Fontanelle and Persutural Ventriculoscopy and Endoscopic Ventricular Surgery in Infants. Childs Brain 1975, 1, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamadani, M.N.A.; Fadhel, M.A.; Alzubaidi, L.; Balazs, H. Reinforcement Learning Algorithms and Applications in Healthcare and Robotics: A Comprehensive and Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowal, S.; Dvijotham, K.; Stanforth, R.; Bunel, R.; Qin, C.; Uesato, J.; Arandjelovic, R.; Mann, T.; Kohli, P. On the Effectiveness of Interval Bound Propagation for Training Verifiably Robust Models. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1810.12715. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.M.; Majid, M.; Qayyum, A.; Awais, M.; Alnowami, M.; Khan, M.K. Medical Image Analysis Using Convolutional Neural Networks: A Review. Journal of Medical Systems 2018, 42, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, L.F.; Marshall, S.B.; Klauber, M.R.; Van Berkum Clark, M.; Eisenberg, H.; Jane, J.A.; Luerssen, T.G.; Marmarou, A.; Foulkes, M.A. The Diagnosis of Head Injury Requires a Classification Based on Computed Axial Tomography. J Neurotrauma 1992, 9 Suppl 1, S287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment of Coma and Impaired Consciousness. A Practical Scale. Lancet 1974, 2, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M.D. Neuropsychological Assessment; Oxford University Press, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-19-511121-4.

- Green, R.E.; Colella, B.; Hebert, D.A.; Bayley, M.; Kang, H.S.; Till, C.; Monette, G. Prediction of Return to Productivity after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Investigations of Optimal Neuropsychological Tests and Timing of Assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008, 89, S51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahjoepramono, P.O.P.; Sasongko, A.B.; Halim, D.; Aviani, J.K.; Lukito, P.P.; Adam, A.; Tsai, Y.T.; Wahjoepramono, E.J.; July, J.; Achmad, T.H. Hydrocephalus Is an Independent Factor Affecting Morbidity and Mortality of ICH Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg X 2023, 19, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchetti, N.; Maas, A.I.R. Traumatic Intracranial Hypertension. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguardia, S.; Piccioni, A.; Alonso Vera, J.E.; Muqaddas, A.; Garcés, M.; Ambreen, S.; Sharma, S.; Sabzvari, T. A Comprehensive Review of the Role of the Latest Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery Techniques and Outcomes for Brain and Spinal Surgeries. Cureus 2025, 17, e84682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, J.D.; Cuthbert, J.P.; Harrison-Felix, C.; Whiteneck, G.G.; Bell, J.M.; Miller, A.C.; Coronado, V.G.; Pretz, C.R. US Population Estimates of Health and Social Outcomes 5 Years after Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014, 29, E1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, M.A.; Giacino, J.T.; Barber, J.; Temkin, N.R.; Nelson, L.D.; Levin, H.S.; Dikmen, S.; Stein, M.; Bodien, Y.G.; Boase, K.; et al. Functional Outcomes Over the First Year After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in the Prospective, Longitudinal TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, C.Q.B.; Singh, R.D.; Gerritsen, M.; Kompanje, E.J.O.; Ribbers, G.M.; Peul, W.C.; van Dijck, J.T.J.M. Long-Term Outcome after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Literature Review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2022, 164, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaggiante, J.; Zhang, X.; Mocco, J.; Kellner, C.P. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2018, 49, 2612–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunert, P. From the Idea to Its Realization: The Evolution of Minimally Invasive Techniques in Neurosurgery. Minim Invasive Surg 2013, 2013, 171369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Lai, R.; Tan, D. A Retrospective Cohort Study of Neuroendoscopic Surgery versus Traditional Craniotomy on Surgical Success Rate, Postoperative Complications, and Prognosis in Patients with Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022, 2022, 2650795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-B.; Kuo, L.-T.; Chen, C.-H.; Kung, W.-M.; Tsai, H.-H.; Chou, S.-C.; Yang, S.-H.; Wang, K.-C.; Lai, D.-M.; Huang, A.P.-H. Surgery for Coagulopathy-Related Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Craniotomy vs. Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery. Life (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wan, X.; Cheng, Q. Minimally Invasive Surgery Is Superior to Conventional Craniotomy in Patients with Spontaneous Supratentorial Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2018, 115, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Han, X.; Tao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hua, W.; Xue, J.; Dong, Q. A Prospective Controlled Study: Minimally Invasive Stereotactic Puncture Therapy versus Conventional Craniotomy in the Treatment of Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. BMC Neurol 2011, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Luo, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, Z.; Xu, B.; Chen, X. Minimally Invasive Surgeries for Spontaneous Hypertensive Intracerebral Hemorrhage (MISICH): A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Med 2024, 22, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, S.R.; Puccio, A.M.; Nelson, L.D.; McCrea, M.; Giacino, J.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Conkright, W.; Jain, S.; Sun, X.; Manley, G.; et al. Association of Obesity with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Symptoms, Inflammatory Profile, Quality of Life and Functional Outcomes: A TRACK-TBI Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2023, 94, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, I.; Maas, A.I.R.; Lu, J.; Marmarou, A.; Murray, G.D.; Mushkudiani, N.A.; McHugh, G.S.; Steyerberg, E.W. Prognostic Value of Admission Blood Pressure in Traumatic Brain Injury: Results from the IMPACT Study. J Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, A.R.; Li, X.; McCauley, S.R.; Wilde, E.A.; Barnes, A.; Hanten, G.; Mendez, D.; McCarthy, J.J.; Levin, H.S. Prevalence and Predictors of Poor Recovery from Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knettel, B.A.; Knettel, C.T.; Sakita, F.; Myers, J.G.; Edward, T.; Minja, L.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Staton, C. Predictors of ICU Admission and Patient Outcome for Traumatic Brain Injury in a Tanzanian Referral Hospital: Implications for Improving Treatment Guidelines. Injury 2022, 53, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walcott, B.P.; Khanna, A.; Kwon, C.-S.; Phillips, H.W.; Nahed, B.V.; Coumans, J.-V. Time Interval to Surgery and Outcomes Following the Surgical Treatment of Acute Traumatic Subdural Hematoma. J Clin Neurosci 2014, 21, 2107–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaersgaard, A.; Nielsen, L.H.; Sjölund, B.H. Factors Affecting Return to Oral Intake in Inpatient Rehabilitation after Acquired Brain Injury. Brain Inj 2015, 29, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakia, K.P.; Wells, A.M.; Tchoulhakian, M.; Iskra, B.S.; Kaculini, C.; Tavakoli-Samour, S.; Boyd, J.T.; Hafeez, S.; Seifi, A.; Dengler, B.A. Factors Affecting Outcomes in Geriatric Traumatic Subdural Hematoma in a Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit. World Neurosurg 2022, 158, e441–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.G.; Hammond, F.M.; Weintraub, A.H.; Nakase-Richardson, R.; Zafonte, R.D.; Whyte, J.; Giacino, J.T. Recovery of Consciousness and Functional Outcome in Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J.; Gabbe, B.; Chen, Z.; Perucca, P.; Kwan, P.; O’Brien, T.J. Risk Factors and Prognosis of Early Posttraumatic Seizures in Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, T.; Roks, G.; de Koning, M.; Scheenen, M.; van der Horn, H.; Plas, G.; Hageman, G.; Schoonman, G.; Spikman, J.; van der Naalt, J. Risk Factors and Outcomes Associated with Post-Traumatic Headache after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Emerg Med J 2017, 34, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Lingsma, H.F.; Roozenbeek, B. Predicting Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury. Handb Clin Neurol 2015, 128, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorani, M.D.; Lee, M.; Kim, H.; Meeker, M.; Manley, G.T. Race\ethnicity and Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury at a Single, Diverse Center. J Trauma 2009, 67, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, S.; Marquez de la Plata, C.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Shipman, K.; Carlile, M.; Frankel, H.; Parks, J.; Gentilello, L.M. Racial Disparities in Long-Term Functional Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury. J Trauma 2007, 63, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamabu, L.K.; Bbosa, G.S.; Lekuya, H.M.; Cho, E.J.; Kyaruzi, V.M.; Nyalundja, A.D.; Deng, D.; Sekabunga, J.N.; Kataka, L.M.; Obiga, D.O.D.; et al. Burden, Risk Factors, Neurosurgical Evacuation Outcomes, and Predictors of Mortality among Traumatic Brain Injury Patients with Expansive Intracranial Hematomas in Uganda: A Mixed Methods Study Design. BMC Surg 2023, 23, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.C.; Barber, J.; Temkin, N.; Gardner, R.C.; Manley, G.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Sandsmark, D. Associations of Preexisting Vascular Risk Factors With Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2023, 38, E88–E98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, J.; Richards, R.; Barney, B.J.; Locandro, C.; Pacchia, C.F.; Charles, A.C.; Cook, L.J.; Gioia, G.; Giza, C.C.; Blume, H.K. Evaluation of Posttraumatic Headache Phenotype and Recovery Time After Youth Concussion. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e211312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.L.; Appleton, S.; Fong, K.; Wood, F.; Coll, F.; de Munck, S.; Newnham, E.; Schug, S.A. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of an Early Multidisciplinary Model to Prevent Disability Following Traumatic Injury. Disabil Rehabil 2013, 35, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, D.J.; Parker, S.L.; Zhu, L.; Cox, C.S.; Kitagawa, R.S.; Fletcher, S.A.; Sandberg, D.I.; Shah, M.N. Outcomes and Prognostic Factors of Pediatric Patients with a Glasgow Coma Score of 3 after Blunt Head Trauma. Childs Nerv Syst 2020, 36, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.K.; Robinson, C.K.; Burke, J.F.; Winkler, E.A.; Deng, H.; Cnossen, M.C.; Lingsma, H.F.; Ferguson, A.R.; McAllister, T.W.; Rosand, J.; et al. Apolipoprotein E Epsilon 4 (APOE-Ε4) Genotype Is Associated with Decreased 6-Month Verbal Memory Performance after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Behav 2017, 7, e00791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, L.L.; Yue, J.K.; Barber, J.; Nelson, L.D.; Bodien, Y.G.; Satris, G.G.; Belton, P.J.; Madhok, D.Y.; Huie, J.R.; Hamidi, S.; et al. Longitudinal Recovery Following Repetitive Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2335804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.F.; Meeker, M.; Holland, M.C. Acute Traumatic Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage: Risk Factors for Progression in the Early Post-Injury Period. Neurosurgery 2006, 58, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Sandersjöö, A.; Tatter, C.; Tjerkaski, J.; Bartek, J.J.; Maegele, M.; Nelson, D.W.; Svensson, M.; Thelin, E.P.; Bellander, B.-M. Time Course and Clinical Significance of Hematoma Expansion in Moderate-to-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: An Observational Cohort Study. Neurocrit Care 2023, 38, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRovere, K.L.; De Souza, B.J.; Szuch, E.; Urion, D.K.; Vitali, S.H.; Zhang, B.; Graham, R.J.; Geva, A.; Tasker, R.C. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Children with Acute Catastrophic Brain Injury: A 13-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurocrit Care 2022, 36, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spears, C.A.; Adil, S.M.; Kolls, B.J.; Muhumza, M.E.; Haglund, M.M.; Fuller, A.T.; Dunn, T.W. Surgical Intervention and Patient Factors Associated with Poor Outcomes in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Uganda. J Neurosurg 2021, 135, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. The Impact of Time from ED Arrival to Surgery on Mortality and Hospital Length of Stay in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Emerg Nurs 2011, 37, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaca, S.D.; Kuo, B.J.; Nickenig Vissoci, J.R.; Staton, C.A.; Xu, L.W.; Muhumuza, M.; Ssenyonjo, H.; Mukasa, J.; Kiryabwire, J.; Rice, H.E.; et al. Temporal Delays Along the Neurosurgical Care Continuum for Traumatic Brain Injury Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kampala, Uganda. Neurosurgery 2019, 84, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laeke, T.; Tirsit, A.; Kassahun, A.; Sahlu, A.; Yesehak, B.; Getahun, S.; Zenebe, E.; Deyassa, N.; Moen, B.E.; Lund-Johansen, M.; et al. Prospective Study of Surgery for Traumatic Brain Injury in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Surgical Procedures, Complications, and Postoperative Outcomes. World Neurosurg 2021, 150, e316–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Komisarow, J.M.; Mills, B.; Vavilala, M.; Hernandez, A.; Laskowitz, D.T.; Mathew, J.P.; James, M.L.; Haines, K.L.; Raghunathan, K.; et al. Echocardiogram Utilization Patterns and Association With Mortality Following Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Anesth Analg 2021, 132, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matovu, P.; Kirya, M.; Galukande, M.; Kiryabwire, J.; Mukisa, J.; Ocen, W.; Lowery Wilson, M.; Abio, A.; Lule, H. Hyperglycemia in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patients and Its Association with Thirty-Day Mortality: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study in Uganda. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majidi, S.; Makke, Y.; Ewida, A.; Sianati, B.; Qureshi, A.I.; Koubeissi, M.Z. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Early Seizure in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: Analysis from National Trauma Data Bank. Neurocrit Care 2017, 27, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scurfield, A.K.; Wilson, M.D.; Gurkoff, G.; Martin, R.; Shahlaie, K. Identification of Demographic and Clinical Prognostic Factors in Traumatic Intraventricular Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2023, 38, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshita, G.; Wondafrash, M.; G/Egziabher, B.; Getachew, B.; Bergene, E. Clinical Characteristics and Functional Outcome of Surgically Treated Adult Head Trauma Patients with Acute Subdural Hematoma: Ethiopian Tertiary Hospitals Experience. World Neurosurg X 2024, 21, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barmparas, G.; Liou, D.Z.; Lamb, A.W.; Gangi, A.; Chin, M.; Ley, E.J.; Salim, A.; Bukur, M. Prehospital Hypertension Is Predictive of Traumatic Brain Injury and Is Associated with Higher Mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014, 77, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, C.; Hatfield, J.; Temkin, N.; Barber, J.; Manley, G.; Ohnuma, T.; Komisarow, J.; Foreman, B.; Korley, F.K.; Vavilala, M.S.; et al. Risk Factors and Neurological Outcomes Associated With Circulatory Shock After Moderate-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study. Neurosurgery 2022, 91, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Gugger, J.; Ding, K.; Kim, J.A.; Foreman, B.; Yue, J.K.; Puccio, A.M.; Yuh, E.L.; Sun, X.; Rabinowitz, M.; et al. Association of Posttraumatic Epilepsy With 1-Year Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2140191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbach, L.L.; Valko, P.O.; Li, T.; Maric, A.; Symeonidou, E.-R.; Stover, J.F.; Bassetti, C.L.; Mica, L.; Werth, E.; Baumann, C.R. Increased Sleep Need and Daytime Sleepiness 6 Months after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain 2015, 138, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.M.; Dilley, M.D.; Carson, A.; Twelftree, J.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Belli, A.; Betteridge, S.; Cooper, P.N.; Griffin, C.M.; Jenkins, P.O.; et al. Management of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): A Clinical Neuroscience-Led Pathway for the NHS. Clin Med (Lond) 2021, 21, e198–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardiotis, E.; Grigoriadis, S.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Genetic Factors Influencing Outcome from Neurotrauma. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaretti, A.; Barone, G.; Riccardi, R.; Antonelli, A.; Pezzotti, P.; Genovese, O.; Tortorolo, L.; Conti, G. NGF, DCX, and NSE Upregulation Correlates with Severity and Outcome of Head Trauma in Children. Neurology 2009, 72, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblad, C.; Pin, E.; Just, D.; Al Nimer, F.; Nilsson, P.; Bellander, B.-M.; Svensson, M.; Piehl, F.; Thelin, E.P. Fluid Proteomics of CSF and Serum Reveal Important Neuroinflammatory Proteins in Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Outcome Prediction Following Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective, Observational Study. Crit Care 2021, 25, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, N.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Bell, M.J.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Essen, T.A.; Res, L.; Schoones, J.; de Ruiter, G.; Dekkers, O.; Maas, A.; Peul, W.; van der Gaag, N.A. Mortality Reduction of Acute Surgery in Traumatic Acute Subdural Hematoma since the 19th Century: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Dramatic Effect: Is Surgery the Obvious Parachute? J Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, A.E.; Leary, J.B.; Radabaugh, H.L.; Cheng, J.P.; Bondi, C.O. Combination Therapies for Neurobehavioral and Cognitive Recovery after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury: Is More Better? Prog Neurobiol 2016, 142, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Rosenfeld, J.V.; Murray, L.; Arabi, Y.M.; Davies, A.R.; D’Urso, P.; Kossmann, T.; Ponsford, J.; Seppelt, I.; Reilly, P.; et al. Decompressive Craniectomy in Diffuse Traumatic Brain Injury. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Mao, Y.; Cao, J.; Dong, B. Management of Screwdriver-Induced Penetrating Brain Injury: A Case Report. BMC Surg 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noiphithak, R.; Ratanavinitkul, W.; Yindeedej, V.; Nimmannitya, P.; Yodwisithsak, P. Outcomes of Combined Endoscopic Surgery and Fibrinolytic Treatment Protocol for Intraventricular Hemorrhage: A Randomized Controlled Trial. World Neurosurg 2023, 172, e555–e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Nakase, K.; Sasaki, R.; Nishimura, F.; Nakagawa, I. Endoscope-Assisted Evacuation of an Acute Subdural Hematoma in an Elderly Patient With Refractory Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus: An Illustrative Case. Cureus 2024, 16, e63817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Goto, H.; Momozaki, N.; Honda, E. Endoscopic Hematoma Evacuation for Acute Subdural Hematoma with Improvement of the Visibility of the Subdural Space and Postoperative Management Using an Intracranial Pressure Sensor. Surg Neurol Int 2023, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, P.J.; Venteicher, A.S.; Agarwalla, P.K.; Kahle, K.T.; Jho, D.H. Endoscopic Burr Hole Evacuation of an Acute Subdural Hematoma. J Clin Neurosci 2013, 20, 1751–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuge, A.; Tsuchiya, D.; Watanabe, S.; Sato, M.; Kinjo, T. Endoscopic Hematoma Evacuation for Acute Subdural Hematoma in a Young Patient: A Case Report. Acute Med Surg 2017, 4, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Somma, L.; Iacoangeli, M.; Nasi, D.; Balercia, P.; Lupi, E.; Girotto, R.; Polonara, G.; Scerrati, M. Combined Supra-Transorbital Keyhole Approach for Treatment of Delayed Intraorbital Encephalocele: A Minimally Invasive Approach for an Unusual Complication of Decompressive Craniectomy. Surg Neurol Int 2016, 7, S12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikane, E.; Hellstrøm, T.; Røe, C.; Bautz-Holter, E.; Assmus, J.; Skouen, J.S. Missing a Follow-up after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury--Does It Matter? Brain Inj 2014, 28, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeybul, S.; Kolias, A.G. Traumatic Brain Injury: Science, Practice, Evidence and Ethics; Springer Nature, 2021; ISBN 3-030-78075-9.

- Fabrizio, C.; Termine, A. Artificial Intelligence Applications for Traumatic Brain Injury Research and Clinical Management. In Neurobiological and Psychological Aspects of Brain Recovery; Petrosini, L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-24930-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Aparicio, P.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. The Impact of Studying Brain Plasticity. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, F.A.; Thelin, E.P.; Helmy, A.; Czosnyka, M.; Hutchinson, P.J.A.; Menon, D.K. A Systematic Review of Cerebral Microdialysis and Outcomes in TBI: Relationships to Patient Functional Outcome, Neurophysiologic Measures, and Tissue Outcome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017, 159, 2245–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.-C.; Shin, D.-S. Endoscopic Treatment of Acute Subdural Hematoma with a Normal Small Craniotomy. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2020, 81, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, C.P.; Song, R.; Pan, J.; Nistal, D.A.; Scaggiante, J.; Chartrain, A.G.; Rumsey, J.; Hom, D.; Dangayach, N.; Swarup, R.; et al. Long-Term Functional Outcome Following Minimally Invasive Endoscopic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation. J Neurointerv Surg 2020, 12, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-X.; He, L.; Zhang, C.-C.; Eisinger, R.; Pan, Y.-X.; Wang, T.; Sun, B.-M.; Wu, Y.-W.; Li, D.-Y. Deep Brain Stimulation in Post-Traumatic Dystonia: A Case Series Study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Vora, N.M.; Tariq, I.; Mujtaba, A.; Caprara, A.L.F. Deep Brain Stimulation for the Management of Refractory Neurological Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, A.-S.; Schwab, M.E. Enhancing Rehabilitation and Functional Recovery after Brain and Spinal Cord Trauma with Electrical Neuromodulation. Curr Opin Neurol 2019, 32, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussard, C.N.; Holm, L.W.; Cancelliere, C.; Godbolt, A.K.; Boyle, E.; Stålnacke, B.-M.; Hincapié, C.A.; Cassidy, J.D.; Borg, J. Nonsurgical Interventions After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2014, 95, S257–S264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, R.; Cordaro, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Management of Traumatic Brain Injury: From Present to Future. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-C.; Wei, W.-Y.; Ho, P.-C. Short-Term Cortical Electrical Stimulation during the Acute Stage of Traumatic Brain Injury Improves Functional Recovery. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janak, J.C.; Cooper, D.B.; Bowles, A.O.; Alamgir, A.H.; Cooper, S.P.; Gabriel, K.P.; Pérez, A.; Orman, J.A. Completion of Multidisciplinary Treatment for Persistent Postconcussive Symptoms Is Associated With Reduced Symptom Burden. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2017, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminmansour, B.; Nikbakht, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Rezvani, M.; Rahmani, P.; Torkashvand, M.; Nourian, M.; Moradi, M. Comparison of the Administration of Progesterone versus Progesterone and Vitamin D in Improvement of Outcomes in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Clinical Trial with Placebo Group. Adv Biomed Res 2012, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talos, I.-F.; O’Donnell, L.; Westin, C.-F.; Warfield, S.K.; Wells III, W.; Yoo, S.-S.; Panych, L.P.; Golby, A.; Mamata, H.; Maier, S.S. Diffusion Tensor and Functional MRI Fusion with Anatomical MRI for Image-Guided Neurosurgery.; Springer, 2003; pp. 407–415.

- Wirtz, C.R.; Tronnier, V.M.; Bonsanto, M.M.; Haßfeld, S.; Knauth, M.; Kunze, S. NeuronavigationMethoden Und Ausblick. Der Nervenarzt 1998, 69, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, A.G.; Riparbelli, A.C.; Siebner, H.R.; Konge, L.; Bjerrum, F. Using Neuroimaging to Assess Brain Activity and Areas Associated with Surgical Skills: A Systematic Review. Surg Endosc 2024, 38, 3004–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepsveridze, L.T.; Semenov, M.S.; Simonyan, A.S.; Pirtskhelava, S.Z.; Stepanyan, G.G.; Imerlishvili, L.K. Burr Hole Microsurgery in Treatment of Patients with Intracranial Lesions: Experience of 44 Clinical Cases. Surg Neurol Int 2020, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krötz, M.; Linsenmaier, U.; Kanz, K.G.; Pfeifer, K.J.; Mutschler, W.; Reiser, M. Evaluation of Minimally Invasive Percutaneous CT-Controlled Ventriculostomy in Patients with Severe Head Trauma. Eur Radiol 2004, 14, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumofen, D.; Regli, L.; Levivier, M.; Krayenbühl, N. Chronic Subdural Hematomas Treated by Burr Hole Trepanation and a Subperiostal Drainage System. Neurosurgery 2009, 64, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigl, G.C.; Staribacher, D.; Britz, G.; Kuzmin, D. Minimally Invasive Approaches in the Surgical Treatment of Intracranial Meningiomas: An Analysis of 54 Cases. Brain Tumor Res Treat 2024, 12, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitskhelauri, D.I.; Konovalov, A.N.; Shekutev, G.A.; Rojnin, N.B.; Kachkov, I.A.; Samborskiy, D.Y.; Sanikidze, A.Z.; Kopachev, D.N. A Novel Device for Hands-Free Positioning and Adjustment of the Surgical Microscope. J Neurosurg 2014, 121, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitskhelauri, D.; Konovalov, A.; Kudieva, E.; Bykanov, A.; Pronin, I.; Eliseeva, N.; Melnikova-Pitskhelauri, T.; Melikyan, A.; Sanikidze, A. Burr Hole Microsurgery for Intracranial Tumors and Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Results of 200 Consecutive Operations. World Neurosurg 2019, 126, e1257–e1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespa, P.; Hanley, D.; Betz, J.; Hoffer, A.; Engh, J.; Carter, R.; Nakaji, P.; Ogilvy, C.; Jallo, J.; Selman, W.; et al. ICES (Intraoperative Stereotactic Computed Tomography-Guided Endoscopic Surgery) for Brain Hemorrhage: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke 2016, 47, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Paff, M.R.; Abrams-Alexandru, D.; Kaloostian, S.W. Decreasing the Cerebral Edema Associated with Traumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhages: Use of a Minimally Invasive Technique. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2016, 121, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labib, M.A.; Shah, M.; Kassam, A.B.; Young, R.; Zucker, L.; Maioriello, A.; Britz, G.; Agbi, C.; Day, J.D.; Gallia, G.; et al. The Safety and Feasibility of Image-Guided BrainPath-Mediated Transsulcul Hematoma Evacuation: A Multicenter Study. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujijantarat, N.; Tecle, N.E.; Pierson, M.; Urquiaga, J.F.; Quadri, N.F.; Ashour, A.M.; Khan, M.Q.; Buchanan, P.; Kumar, A.; Feen, E.; et al. Trans-Sulcal Endoport-Assisted Evacuation of Supratentorial Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Initial Single-Institution Experience Compared to Matched Medically Managed Patients and Effect on 30-Day Mortality. Oper Neurosurg 2018, 14, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, M.; Tutihashi, R.; Li, Y.; Rosi, J.J.; Ping Jeng, B.C.; Teixeira, M.J.; Figueiredo, E.G. MISIAN (Minimally Invasive Surgery for Treatment of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms): A Prospective Randomized Single-Center Clinical Trial With Long-Term Follow-Up Comparing Different Minimally Invasive Surgery Techniques with Standard Open Surgery. World Neurosurg 2021, 151, e533–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, H.A.; Polsky, D.; Willke, R.J.; Schulman, K.A. A Comparison of Preference Assessment Instruments Used in a Clinical Trial: Responses to the Visual Analog Scale from the EuroQol EQ-5D and the Health Utilities Index. Med Decis Making 1999, 19, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, S.R.; Wilde, E.A.; Anderson, V.A.; Bedell, G.; Beers, S.R.; Campbell, T.F.; Chapman, S.B.; Ewing-Cobbs, L.; Gerring, J.P.; Gioia, G.A.; et al. Recommendations for the Use of Common Outcome Measures in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury Research. J Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 678–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, B. The Glasgow Coma Scale: History and Current Practice. Trauma 2002, 4, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.A.; Sills, G.J.; Forrest, G.; Brodie, M.J. High Dose Gabapentin in Refractory Partial Epilepsy: Clinical Observations in 50 Patients. Epilepsy Res. 1998, 29, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, T.; Wilson, L.; Ponsford, J.; Levin, H.; Teasdale, G.; Bond, M. The Glasgow Outcome Scale - 40 Years of Application and Refinement. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, C.; Pfefferkorn, T.; Ebrahimi, C.; Ottomeyer, C.; Fesl, G.; Bender, A.; Straube, A.; Pfister, H.-W.; Heck, S.; Tonn, J.-C.; et al. Long-Term Neurological Outcome and Quality of Life after World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies Grades IV and V Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in an Interdisciplinary Treatment Concept. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algburi, H.A.; Ismail, M.; Mallah, S.I.; Alduraibi, L.S.; Albairmani, S.; Abdulameer, A.O.; Alayyaf, A.S.; Aljuboori, Z.; Andaluz, N.; Hoz, S.S. Outcome Measures in Neurosurgery: Is a Unified Approach Better? A Literature Review. Surg Neurol Int 2023, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Visser, M.C.; Schouten, H.J.; van Gijn, J. Interobserver Agreement for the Assessment of Handicap in Stroke Patients. Stroke 1988, 19, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, C. “Just Give Me the Best Quality of Life Questionnaire”: The Karnofsky Scale and the History of Quality of Life Measurements in Cancer Trials. Chronic Illn 2013, 9, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Approach | Functional/ Cognitive outcomes | QoL/ Daily activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. [42] | Neuroendoscopy MIN vs. traditional craniotomy | Higher MoCA cognitive scores; better limb motor and NIHSS/GCS scores in MIN group (p < 0.05) | Barthel Index and quality-of-life domains (physiological, psychological, social) significantly better in MIN group |

| Liu et al. [43] | MIN vs. craniotomy | MIN group had higher 1-year GOSE (4.0 vs. 3.1, p = 0.027) and better estimated mRS (p = 0.0427) | Lower morbidity (8.7% vs. 30.8%), and similar hospital/ICU stay |

| Xia et al. [44] | MIN vs. craniotomy | MIN associated with higher rate of “good recovery” (OR 2.27, p-value significant) | No direct QoL metrics, but functional recovery better |

| Zhou et al. [45] | Stereotactic MISPT vs. conventional craniotomy | Similar preoperative GCS, but 1-year GOS, mRS, BI significantly better in MISPT group (p < 0.001) | BI improved—indicative of better daily living ability |

| Xu et al. [46] | Endoscopic or stereotactic aspiration vs. craniotomy | For deep supratentorial hemorrhage: favorable outcome rates ~30% MIN vs. ~15% craniotomy (P = 0.001) | Improved functional outcomes imply better quality of life/daily functioning |

| Domain | Factors | Associated with outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related factors | Age, gender, race | Age: conflicting associations with poor outcomes (linked to both younger and older age, or no association); varies by outcome type. Gender: female patients are generally associated with poorer outcomes than males. Race: black patients tend to have poorer outcomes compared to white and Asian patients. |

| Life style | Smoking: associated with generally poorer outcomes. Alcohol use: linked to increased pain, depressive symptoms, PTSD severity, and reduced physical mobility. | |

| Co-morbidities | Obesity: associated with increased post-concussive symptoms. Migraine/ headache: linked to poorer outcomes. Anxiety/ depression: significant predictors of post-traumatic headache. Vasculopathy comorbidities: primary determinants of post-traumatic seizures, surgical outcomes, and discharge status. |

|

| Biomarkers | Systolic blood pressure >90 mmHg: associated with favorable outcomes. Oxygen saturation >90%: linked to favorable outcomes. Elevated arrival temperature: associated with favorable outcomes. Swirl sign: Indicative of expansive intracranial hematomas. APOE-ε4 Allele: Associated with delayed verbal memory deficits. | |

| Injury-related factors | Number of traumas | Multiple injuries: associated with worse outcomes compared to single trauma. |

| Mechanism of injury | Disorder of consciousness: associated with high-velocity injuries and intracranial hemorrhages. Early post-traumatic seizures: linked to low falls, hemorrhages, and greater injury severity. | |

| Severity of injury and inside damage | Disorder of consciousness: associated with intraventricular hemorrhages. Early post-traumatic seizures: linked to subdural/subarachnoid hemorrhages and injury severity. Surgical decision factors: based on hematoma size, cisternal compression on initial scan, and changes in GCS. | |

| Intervention-related factors | Surgery related factors | Surgery: generally associated with reduced risk of poor outcomes in TBI. Timing of surgery: evidence is conflicting regarding its impact on outcomes. Minimally invasive surgery: linked to shorter hospital stays and operative times; however, one study found no significant difference in outcomes compared to traditional surgery. |

| Other interventions | ICU admission: associated with poorer outcomes. Echocardiogram: linked to reduced mortality. Aspirin use: associated with lower mortality. Dysphagia interventions: increased interventions correlated with reduced likelihood of achieving full oral intake. | |

| Post-interventional care and complications | Hypothermia, seizures, hypotension, shock, low GCS: associated with increased mortality and complications. Elevated hemoglobin: linked to better outcomes. Mechanical ventilation: associated with higher mortality risk. Feeding tubes, spasticity, CSF leakage: predictors of increased mortality. | |

| Others | Environmental factors | Impact well-being and quality of life in TBI patients. |

| Biomarkers after injury | NGF↑, DCX↑, NSE↓: early elevated NGF and DCX, and reduced NSE levels, associated with better neurological outcomes. Complement C9 (CSF) and factor B (serum): identified as predictors of clinical outcomes. | |

| References | Neurological treatment | Neurosurgery treatment | General outcome | Additional outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arai et al. [93] | Lacosamide, diazepam, fosphenytoin, and phenobarbital. | Endoscope-assisted acute subdural hematoma evacuation. | No effect from medication alone; full recovery followed surgery and drug therapy. | Consciousness improved; no neurological deficits; near-total hematoma cleared on CT (day 1); mRS 4 at discharge due to diffuse atrophy. |

| Tanaka et al. [94] | Antithrombotics were paused pre-operatively; restarted with antiplatelets 1 week post-operatively based on the condition. | Endoscopic hematoma evacuation. | Satisfactory outcome with no complications or rebleeding. | Op time: 61–143 min; 2 cases of elevated ICP; hospital stay: 5–250 days; mortality: 22.2%. |

| Codd et al. [95] | Prophylactic levetiracetam (seizures). | Endoscopic burr hole evacuation. | Good functional recovery; seizure-free by day 11 post-op. | Initially unresponsive; by day 4, fully oriented and mobile. Discharged day 11, neurologically intact. |

| Kuge et al. [96] | Mannitol infusion for consciousness recovery. | Endoscopic evacuation for acute subdural hematoma. | Endoscopic evacuation for acute subdural hematoma. | Post-op symptoms significantly improved. |

| Scale | Aim | Main application | Alternative applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) | Assesses functional recovery after severe brain injury | Severe brain injury following TBI | Intracranial aneurysms, tumors, strokes, and cranioplasty | Jennett et al. [129] |

| Modified Rankin scale (mRS) | Classifies functional recovery after cerebrovascular accident at discharge | Assesses cerebrovascular disease in adults (≥60) at discharge or referral | Used in aneurysms, general brain injury, hypothermia trials, sarcopenia, spinal meningiomas, and pediatric transverse myelitis | van Swieten et al. [134] |

| Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) | Assesses functional status in tumor patients | Tumors and cancers, primarily in neuro-oncology and post-treatment settings | Used measure of disability, particularly in palliative care, geriatrics, osteoarthritis, and post-revascularization surgery settings | Timmermann et al. [135] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).