Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Genetics

2.1. ALS Genes

2.2. Genetic Diagnosis and Counseling Challenges

3. Pathophysiology

4. Preclinical Studies on ALS

4.1. In Vivo Studies

4.2. In Vitro Studies

4.2.1. Human iPSC-Derived Organoids

4.2.2. Human iPSC-Derived Neurons and Glia

5. Clinical Presentation

5.1. Classical ALS

5.1.1. Typical Clinical Features

5.1.2. Additional Clinical Features

5.2. Other Motor Neuron Disease Subtypes

5.2.1. Progressive Muscular Atrophy (PMA)

5.2.2. Progressive Bulbar Palsy (PBP)

5.2.3. Primary Lateral Sclerosis (PLS)

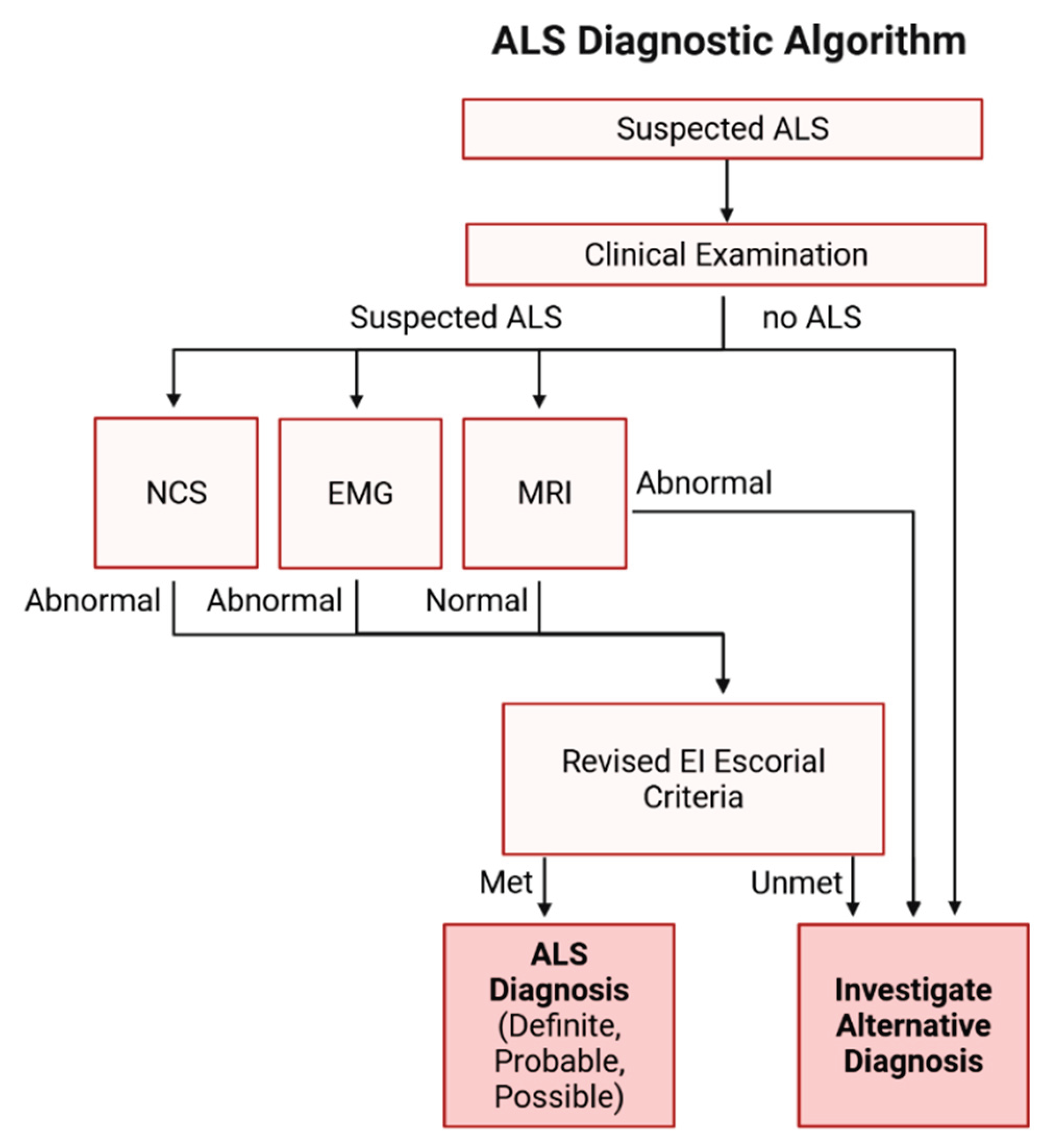

6. Disease Diagnosis

7. Treatment

8. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Song, T.-J. The Global Burden of Motor Neuron Disease: An Analysis of the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 864339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A.; Lally, C.; Kupelian, V.; Flanders, W.D. Estimated Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and SOD1 and C9orf72 Genetic Variants. Neuroepidemiology 2021, 55, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A.; Lally, C.; Kupelian, V.; Flanders, W.D. Estimated Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and SOD1 and C9orf72 Genetic Variants. Neuroepidemiology 2021, 55, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. Clinical Manifestation and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. In Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Araki, T., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane (AU), 2021 ISBN 978-0-6450017-7-8.

- Grad, L.I.; Rouleau, G.A.; Ravits, J.; Cashman, N.R. Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7, a024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L.P.; Shneider, N.A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2001, 344, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logroscino, G.; Traynor, B.J.; Hardiman, O.; Chiò, A.; Mitchell, D.; Swingler, R.J.; Millul, A.; Benn, E.; Beghi, E. ; EURALS Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010, 81, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, J.R.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M.C. Isolated Bulbar Phenotype of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011, 12, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassano, M.; Moglia, C.; Palumbo, F.; Koumantakis, E.; Cugnasco, P.; Callegaro, S.; Canosa, A.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; De Mattei, F.; et al. Sex Differences in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Survival and Progression: A Multidimensional Analysis. Annals of Neurology 2024, 96, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Emerging Insights into the Complex Genetics and Pathophysiology of ALS. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberio, J.; Lally, C.; Kupelian, V.; Hardiman, O.; Flanders, W.D. Estimated Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Proportion: A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol Genet 2023, 9, e200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, T.; Figlewicz, D.A.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Haines, J.L.; Rouleau, G.; Jeffers, A.J.; Sapp, P.; Hung, W.Y.; Bebout, J.; McKenna-Yasek, D. Linkage of a Gene Causing Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis to Chromosome 21 and Evidence of Genetic-Locus Heterogeneity. N Engl J Med 1991, 324, 1381–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.R.; Siddique, T.; Patterson, D.; Figlewicz, D.A.; Sapp, P.; Hentati, A.; Donaldson, D.; Goto, J.; O’Regan, J.P.; Deng, H.X. Mutations in Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase Gene Are Associated with Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nature 1993, 362, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Traynor, B.J.; Lombardo, F.; Fimognari, M.; Calvo, A.; Ghiglione, P.; Mutani, R.; Restagno, G. Prevalence of SOD1 Mutations in the Italian ALS Population. Neurology 2008, 70, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnlein, P.; Sperfeld, A.-D.; Vanmassenhove, B.; Van Deerlin, V.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; Ludolph, A.C.; Neumann, M. Two German Kindreds With Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Due to TARDBP Mutations. Archives of Neurology 2008, 65, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.J.; Bosco, D.A.; Leclerc, A.L.; Tamrazian, E.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Russ, C.; Davis, A.; Gilchrist, J.; Kasarskis, E.J.; Munsat, T.; et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS Gene on Chromosome 16 Cause Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2009, 323, 1205–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Rollinson, S.; Gibbs, J.R.; Schymick, J.C.; Laaksovirta, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Myllykangas, L.; et al. A Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in C9ORF72 Is the Cause of Chromosome 9p21-Linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011, 72, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJesus-Hernandez, M.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Boeve, B.F.; Boxer, A.L.; Baker, M.; Rutherford, N.J.; Nicholson, A.M.; Finch, N.A.; Flynn, H.; Adamson, J.; et al. Expanded GGGGCC Hexanucleotide Repeat in Noncoding Region of C9ORF72 Causes Chromosome 9p-Linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011, 72, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, M.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Andersen, P.M.; Hosler, B.; Sapp, P.; Englund, E.; Mitchell, J.E.; Habgood, J.J.; de Belleroche, J.; Xi, J.; et al. A Locus on Chromosome 9p Confers Susceptibility to ALS and Frontotemporal Dementia. Neurology 2006, 66, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, C.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Ruddy, D.; Smith, B.N.; Hu, X.; Sreedharan, J.; Siddique, T.; Schelhaas, H.J.; Kusters, B.; Troost, D.; et al. Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Frontotemporal Dementia Is Linked to a Locus on Chromosome 9p13. 2-21.3. Brain 2006, 129, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, A.L.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Boeve, B.F.; Baker, M.; Seeley, W.W.; Crook, R.; Feldman, H.; Hsiung, G.-Y.R.; Rutherford, N.; Laluz, V.; et al. Clinical, Neuroimaging and Neuropathological Features of a New Chromosome 9p-Linked FTD-ALS Family. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011, 82, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, M.A.; Veldink, J.H.; Saris, C.G.J.; Blauw, H.M.; van Vught, P.W.J.; Birve, A.; Lemmens, R.; Schelhaas, H.J.; Groen, E.J.N.; Huisman, M.H.B.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies 19p13. 3 (UNC13A) and 9p21.2 as Susceptibility Loci for Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat Genet 2009, 41, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksovirta, H.; Peuralinna, T.; Schymick, J.C.; Scholz, S.W.; Lai, S.-L.; Myllykangas, L.; Sulkava, R.; Jansson, L.; Hernandez, D.G.; Gibbs, J.R.; et al. Chromosome 9p21 in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Finland: A Genome-Wide Association Study. The Lancet Neurology 2010, 9, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatunov, A.; Mok, K.; Newhouse, S.; Weale, M.E.; Smith, B.; Vance, C.; Johnson, L.; Veldink, J.H.; van Es, M.A.; van den Berg, L.H.; et al. Chromosome 9p21 in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in the UK and Seven Other Countries: A Genome-Wide Association Study. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deerlin, V.M.; Sleiman, P.M.A.; Martinez-Lage, M.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; Wang, L.-S.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Dickson, D.W.; Rademakers, R.; Boeve, B.F.; Grossman, M.; et al. Common Variants at 7p21 Are Associated with Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration with TDP-43 Inclusions. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.N.; Newhouse, S.; Shatunov, A.; Vance, C.; Topp, S.; Johnson, L.; Miller, J.; Lee, Y.; Troakes, C.; Scott, K.M.; et al. The C9ORF72 Expansion Mutation Is a Common Cause of ALS+/−FTD in Europe and Has a Single Founder. Eur J Hum Genet 2013, 21, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaki, K.; Li, Y.; Atsuta, N.; Tomiyama, H.; Funayama, M.; Watanabe, H.; Nakamura, R.; Yoshino, H.; Yato, S.; Tamura, A.; et al. Analysis of C9orf72 Repeat Expansion in 563 Japanese Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33, 2527.e11-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, A.; Niihori, T.; Warita, H.; Izumi, R.; Akiyama, T.; Kato, M.; Suzuki, N.; Aoki, Y.; Aoki, M. Comprehensive Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Japanese Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 53, 194.e1-194.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, A.; Niihori, T.; Warita, H.; Izumi, R.; Akiyama, T.; Kato, M.; Suzuki, N.; Aoki, Y.; Aoki, M. Comprehensive Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Japanese Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 53, 194.e1-194.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghero, G.; Pugliatti, M.; Marrosu, F.; Marrosu, M.G.; Murru, M.R.; Floris, G.; Cannas, A.; Parish, L.D.; Occhineri, P.; Cau, T.B.; et al. Genetic Architecture of ALS in Sardinia. Neurobiology of Aging 2014, 35, 2882.e7-2882.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassano, M.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C.; Sbaiz, L.; Brunetti, M.; Barberis, M.; Casale, F.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; Canosa, A.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of Genetic Mutations in ALS: A Population-Based Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.-S.; Wakabayashi, K.; Kakita, A.; Yamada, M.; Hayashi, S.; Morita, T.; Ikuta, F.; Oyanagi, K.; Takahashi, H. Neuropathology with Clinical Correlations of Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: 102 Autopsy Cases Examined between 1962 and 2000. Brain Pathol 2003, 13, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Akiyama, H.; Ikeda, K.; Nonaka, T.; Mori, H.; Mann, D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hashizume, Y.; et al. TDP-43 Is a Component of Ubiquitin-Positive Tau-Negative Inclusions in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 351, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziortzouda, P.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Hirth, F. Triad of TDP43 Control in Neurodegeneration: Autoregulation, Localization and Aggregation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Arai, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Akatsu, H.; Obi, T.; Yoshida, M.; Murayama, S.; Mann, D.M.A.; Akiyama, H.; et al. Prion-like Properties of Pathological TDP-43 Aggregates from Diseased Brains. Cell Rep 2013, 4, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Sampathu, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Truax, A.C.; Micsenyi, M.C.; Chou, T.T.; Bruce, J.; Schuck, T.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2006, 314, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragagnin, A.M.G.; Shadfar, S.; Vidal, M.; Jamali, M.S.; Atkin, J.D. Motor Neuron Susceptibility in ALS/FTD. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, N.; Gentile, F.; Cerri, F.; Gallia, F.; Podini, P.; Dina, G.; Falzone, Y.M.; Fazio, R.; Lunetta, C.; Calvo, A.; et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 Aggregates in Peripheral Motor Nerves of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 2022, 145, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, J.; Del Tredici, K.; Toledo, J.B.; Robinson, J.L.; Irwin, D.J.; Grossman, M.; Suh, E.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Wood, E.M.; Baek, Y.; et al. Stages of pTDP-43 Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013, 74, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-F.; Eguchi, H.; Tagawa, A.; Onodera, O.; Iwasaki, T.; Tsujino, A.; Nishizawa, M.; Kakita, A.; Takahashi, H. TDP-43 Immunoreactivity in Neuronal Inclusions in Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with or without SOD1 Gene Mutation. Acta Neuropathol 2007, 113, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.L.; Geser, F.; Stieber, A.; Umoh, M.; Kwong, L.K.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. TDP-43 Skeins Show Properties of Amyloid in a Subset of ALS Cases. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 125, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y. Abnormal Splicing Events Due to Loss of Nuclear Function of TDP-43: Pathophysiology and Perspectives. JMA J 2024, 7, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotter, E.L.; Chen, H.-J.; Shaw, C.E. TDP-43 Proteinopathy and ALS: Insights into Disease Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanashi, K.; Yamaguchi, A. Aggregation of ALS-Linked FUS Mutant Sequesters RNA Binding Proteins and Impairs RNA Granules Formation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2014, 452, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scekic-Zahirovic, J.; Sendscheid, O.; El Oussini, H.; Jambeau, M.; Sun, Y.; Mersmann, S.; Wagner, M.; Dieterlé, S.; Sinniger, J.; Dirrig-Grosch, S.; et al. Toxic Gain of Function from Mutant FUS Protein Is Crucial to Trigger Cell Autonomous Motor Neuron Loss. The EMBO Journal 2016, 35, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejzini, R.; Flynn, L.L.; Pitout, I.L.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D.; Akkari, P.A. ALS Genetics, Mechanisms, and Therapeutics: Where Are We Now? Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balendra, R.; Isaacs, A.M. C9orf72-Mediated ALS and FTD: Multiple Pathways to Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizielinska, S.; Lashley, T.; Norona, F.E.; Clayton, E.L.; Ridler, C.E.; Fratta, P.; Isaacs, A.M. C9orf72 Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Is Characterised by Frequent Neuronal Sense and Antisense RNA Foci. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 126, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.M.; Glineburg, M.R.; Kearse, M.G.; Flores, B.N.; Linsalata, A.E.; Fedak, S.J.; Goldstrohm, A.C.; Barmada, S.J.; Todd, P.K. RAN Translation at C9orf72-Associated Repeat Expansions Is Selectively Enhanced by the Integrated Stress Response. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.M.A.; Rollinson, S.; Robinson, A.; Bennion Callister, J.; Thompson, J.C.; Snowden, J.S.; Gendron, T.; Petrucelli, L.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Hasegawa, M.; et al. Dipeptide Repeat Proteins Are Present in the P62 Positive Inclusions in Patients with Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Motor Neurone Disease Associated with Expansions in C9ORF72. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2013, 1, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M.E.V.; Mrkela, M.; Murray, H.C.; Cao, M.C.; Turner, C.; Curtis, M.A.; Faull, R.L.M.; Walker, A.K.; Scotter, E.L. Microglial CD68 and L-Ferritin Upregulation in Response to Phosphorylated-TDP-43 Pathology in the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2023, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Jawaid, A.; Henstridge, C.M.; Valeri, A.; Merlini, M.; Robinson, J.L.; Lee, E.B.; Rose, J.; Appel, S.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; et al. TDP-43 Depletion in Microglia Promotes Amyloid Clearance but Also Induces Synapse Loss. Neuron 2017, 95, 297–308.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahia El Idrissi, N.; Bosch, S.; Ramaglia, V.; Aronica, E.; Baas, F.; Troost, D. Complement Activation at the Motor End-Plates in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Komine, O. The Multi-Dimensional Roles of Astrocytes in ALS. Neurosci Res 2018, 126, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Held, A.; Dorfman, K.; Sung, J.; Song, C.; Kavuturu, A.S.; Aguilar, C.; Russo, T.; Oakley, D.H.; Albers, M.W.; et al. Neuronal STING Activation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Acta Neuropathol 2024, 147, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurney, M.E.; Pu, H.; Chiu, A.Y.; Dal Canto, M.C.; Polchow, C.Y.; Alexander, D.D.; Caliendo, J.; Hentati, A.; Kwon, Y.W.; Deng, H.X. Motor Neuron Degeneration in Mice That Express a Human Cu,Zn Superoxide Dismutase Mutation. Science 1994, 264, 1772–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, B.; Gautam, M.; Helmold, B.R.; Koçak, N.; Günay, A.; Goshu, G.M.; Silverman, R.B.; Hande Ozdinler, P. NU-9 Improves Health of hSOD1G93A Mouse Upper Motor Neurons in Vitro, Especially in Combination with Riluzole or Edaravone. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, S.; Li, X.-J.; Yin, P. Pathological Insights from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Animal Models: Comparisons, Limitations, and Challenges. Translational Neurodegeneration 2023, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, W.; Jeong, Y.H.; Lin, S.; Ling, J.; Price, D.L.; Chiang, P.-M.; Wong, P.C. Rodent Models of TDP-43: Recent Advances. Brain Res 2012, 1462, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Talbot, K.; Ansorge, O. Pathogenesis of FUS-Associated ALS and FTD: Insights from Rodent Models. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2016, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Lee, C.W. Mouse Models of C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/ Frontotemporal Dementia. Front Cell Neurosci 2017, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, D.S.; Liu, J.; She, Y.; Goad, B.; Maragakis, N.J.; Kim, B.; Erickson, J.; Kulik, J.; DeVito, L.; Psaltis, G.; et al. Focal Loss of the Glutamate Transporter EAAT2 in a Transgenic Rat Model of SOD1 Mutant-Mediated Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.M.; Rafuse, V.F. Muscle Fiber-Type Specific Terminal Schwann Cell Pathology Leads to Sprouting Deficits Following Partial Denervation in SOD1G93A Mice. Neurobiology of Disease 2020, 145, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Lee, K.-W.; Choi, S.-M.; Yang, E.J. TDP-43 Modification in the hSOD1(G93A) Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mouse Model. Neurol Res 2015, 37, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripps, M.E.; Huntley, G.W.; Hof, P.R.; Morrison, J.H.; Gordon, J.W. Transgenic Mice Expressing an Altered Murine Superoxide Dismutase Gene Provide an Animal Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijn, L.I.; Becher, M.W.; Lee, M.K.; Anderson, K.L.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Sisodia, S.S.; Rothstein, J.D.; Borchelt, D.R.; Price, D.L.; et al. ALS-Linked SOD1 Mutant G85R Mediates Damage to Astrocytes and Promotes Rapidly Progressive Disease with SOD1-Containing Inclusions. Neuron 1997, 18, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.C.; Pardo, C.A.; Borchelt, D.R.; Lee, M.K.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Sisodia, S.S.; Cleveland, D.W.; Price, D.L. An Adverse Property of a Familial ALS-Linked SOD1 Mutation Causes Motor Neuron Disease Characterized by Vacuolar Degeneration of Mitochondria. Neuron 1995, 14, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafuri, F.; Ronchi, D.; Magri, F.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. SOD1 Misplacing and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, E.; Bravi, R.; Scambi, I.; Mariotti, R.; Minciacchi, D. Increased Anxiety-like Behavior and Selective Learning Impairments Are Concomitant to Loss of Hippocampal Interneurons in the Presymptomatic SOD1(G93A) ALS Mouse Model. J Comp Neurol 2015, 523, 1622–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegorzewska, I.; Bell, S.; Cairns, N.J.; Miller, T.M.; Baloh, R.H. TDP-43 Mutant Transgenic Mice Develop Features of ALS and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 18809–18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.S.; Ling, S.-C.; Huelga, S.C.; Lagier-Tourenne, C.; Polymenidou, M.; Ditsworth, D.; Kordasiewicz, H.B.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Platoshyn, O.; Parone, P.A.; et al. ALS-Linked TDP-43 Mutations Produce Aberrant RNA Splicing and Adult-Onset Motor Neuron Disease without Aggregation or Loss of Nuclear TDP-43. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E736–E745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallings, N.R.; Puttaparthi, K.; Luther, C.M.; Burns, D.K.; Elliott, J.L. Progressive Motor Weakness in Transgenic Mice Expressing Human TDP-43. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 40, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Tong, J.; Bi, F.; Zhou, H.; Xia, X.-G. Mutant TDP-43 in Motor Neurons Promotes the Onset and Progression of ALS in Rats. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wils, H.; Kleinberger, G.; Janssens, J.; Pereson, S.; Joris, G.; Cuijt, I.; Smits, V.; Ceuterick-de Groote, C.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; Kumar-Singh, S. TDP-43 Transgenic Mice Develop Spastic Paralysis and Neuronal Inclusions Characteristic of ALS and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 3858–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-F.; Gendron, T.F.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Lin, W.-L.; D’Alton, S.; Sheng, H.; Casey, M.C.; Tong, J.; Knight, J.; Yu, X.; et al. Wild-Type Human TDP-43 Expression Causes TDP-43 Phosphorylation, Mitochondrial Aggregation, Motor Deficits, and Early Mortality in Transgenic Mice. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 10851–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Huang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Landel, C.P.; Xia, P.Y.; Bowser, R.; Liu, Y.-J.; Xia, X.G. Transgenic Rat Model of Neurodegeneration Caused by Mutation in the TDP Gene. PLoS Genet 2010, 6, e1000887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Tong, J.; Bi, F.; Wu, Q.; Huang, B.; Zhou, H.; Xia, X.-G. Entorhinal Cortical Neurons Are the Primary Targets of FUS Mislocalization and Ubiquitin Aggregation in FUS Transgenic Rats. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 4602–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, H.; Tong, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Xia, X.-G. FUS Transgenic Rats Develop the Phenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. PLoS Genet 2011, 7, e1002011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Lyashchenko, A.K.; Lu, L.; Nasrabady, S.E.; Elmaleh, M.; Mendelsohn, M.; Nemes, A.; Tapia, J.C.; Mentis, G.Z.; Shneider, N.A. ALS-Associated Mutant FUS Induces Selective Motor Neuron Degeneration through Toxic Gain of Function. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.K.; Deykin, A.V.; Bronovitsky, E.V.; Ovchinnikov, R.K.; Ustyugov, A.A.; Shelkovnikova, T.A.; Kukharsky, M.S.; Ermolkevich, T.G.; Goldman, I.L.; Sadchikova, E.R.; et al. Early Lethality and Neuronal Proteinopathy in Mice Expressing Cytoplasm-Targeted FUS That Lacks the RNA Recognition Motif. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2015, 16, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.C.; McGoldrick, P.; Vance, C.; Hortobagyi, T.; Sreedharan, J.; Rogelj, B.; Tudor, E.L.; Smith, B.N.; Klasen, C.; Miller, C.C.J.; et al. Overexpression of Human Wild-Type FUS Causes Progressive Motor Neuron Degeneration in an Age- and Dose-Dependent Fashion. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 125, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Lee, S.; Shang, Y.; Wang, W.-Y.; Au, K.F.; Kamiya, S.; Barmada, S.J.; Finkbeiner, S.; Lui, H.; Carlton, C.E.; et al. ALS-Associated Mutation FUS-R521C Causes DNA Damage and RNA Splicing Defects. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, C.F.; Tang, A.A.; Kulkarni, A.; West, J.; Brooks, M.; Stubblefield, J.J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.Q.; Green, C.B.; Huber, K.M.; et al. Activity-Dependent FUS Dysregulation Disrupts Synaptic Homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, E4769–E4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Gendron, T.F.; Grima, J.C.; Sasaguri, H.; Jansen-West, K.; Xu, Y.-F.; Katzman, R.B.; Gass, J.; Murray, M.E.; Shinohara, M.; et al. C9ORF72 Poly(GA) Aggregates Sequester and Impair HR23 and Nucleocytoplasmic Transport Proteins. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, J.; Gendron, T.F.; Prudencio, M.; Sasaguri, H.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Castanedes-Casey, M.; Lee, C.W.; Jansen-West, K.; Kurti, A.; Murray, M.E.; et al. Neurodegeneration. C9ORF72 Repeat Expansions in Mice Cause TDP-43 Pathology, Neuronal Loss, and Behavioral Deficits. Science 2015, 348, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Pattamatta, A.; Zu, T.; Reid, T.; Bardhi, O.; Borchelt, D.R.; Yachnis, A.T.; Ranum, L.P.W. C9orf72 BAC Mouse Model with Motor Deficits and Neurodegenerative Features of ALS/FTD. Neuron 2016, 90, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Gendron, T.F.; Saberi, S.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Seelman, A.; Stauffer, J.E.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Drenner, K.; Schulte, D.; et al. Gain of Toxicity from ALS/FTD-Linked Repeat Expansions in C9ORF72 Is Alleviated by Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting GGGGCC-Containing RNAs. Neuron 2016, 90, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, O.M.; Cabrera, G.T.; Tran, H.; Gendron, T.F.; McKeon, J.E.; Metterville, J.; Weiss, A.; Wightman, N.; Salameh, J.; Kim, J.; et al. Human C9ORF72 Hexanucleotide Expansion Reproduces RNA Foci and Dipeptide Repeat Proteins but Not Neurodegeneration in BAC Transgenic Mice. Neuron 2015, 88, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, J.G.; Bogdanik, L.; Muhammad, A.K.M.G.; Gendron, T.F.; Kim, K.J.; Austin, A.; Cady, J.; Liu, E.Y.; Zarrow, J.; Grant, S.; et al. C9orf72 BAC Transgenic Mice Display Typical Pathologic Features of ALS/FTD. Neuron 2015, 88, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Martin, S.; Chandran, J.; Lewis, K.; Mulcahy, P.; Higginbottom, A.; Walker, C.; Valenzuela, I.M.-P.Y.; Jones, R.A.; Coldicott, I.; Iannitti, T.; et al. Viral Delivery of C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansions in Mice Leads to Repeat-Length-Dependent Neuropathology and Behavioural Deficits. Dis Model Mech 2017, 10, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovsky-Dagan, S.; Mor-Shaked, H.; Eiges, R. Modeling Diseases of Noncoding Unstable Repeat Expansions Using Mutant Pluripotent Stem Cells. World J Stem Cells 2015, 7, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabashi, E.; Lin, L.; Tradewell, M.L.; Dion, P.A.; Bercier, V.; Bourgouin, P.; Rochefort, D.; Bel Hadj, S.; Durham, H.D.; Vande Velde, C.; et al. Gain and Loss of Function of ALS-Related Mutations of TARDBP (TDP-43) Cause Motor Deficits in Vivo. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, R.; Van Hoecke, A.; Hersmus, N.; Geelen, V.; D’Hollander, I.; Thijs, V.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Carmeliet, P.; Robberecht, W. Overexpression of Mutant Superoxide Dismutase 1 Causes a Motor Axonopathy in the Zebrafish. Human Molecular Genetics 2007, 16, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewamadduma, C.A.A.; Grierson, A.J.; Ma, T.P.; Pan, L.; Moens, C.B.; Ingham, P.W.; Ramesh, T.; Shaw, P.J. Tardbpl Splicing Rescues Motor Neuron and Axonal Development in a Mutant Tardbp Zebrafish. Hum Mol Genet 2013, 22, 2376–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, L.; Ghilardi, A.; Rottoli, E.; De Maglie, M.; Prosperi, L.; Perego, C.; Baruscotti, M.; Bucchi, A.; Del Giacco, L.; Francolini, M. INaP Selective Inhibition Reverts Precocious Inter- and Motorneurons Hyperexcitability in the Sod1-G93R Zebrafish ALS Model. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 24515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciura, S.; Lattante, S.; Le Ber, I.; Latouche, M.; Tostivint, H.; Brice, A.; Kabashi, E. Loss of Function of C9orf72 Causes Motor Deficits in a Zebrafish Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013, 74, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Lyon, A.N.; Pineda, R.H.; Wang, C.; Janssen, P.M.L.; Canan, B.D.; Burghes, A.H.M.; Beattie, C.E. A Genetic Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Zebrafish Displays Phenotypic Hallmarks of Motoneuron Disease. Dis Model Mech 2010, 3, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, K.R.; Godena, V.K.; Hewitt, V.L.; Whitworth, A.J. Axonal Transport Defects Are a Common Phenotype in Drosophila Models of ALS. Hum Mol Genet 2016, 25, 2378–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuva-Aydemir, Y.; Almeida, S.; Gao, F.-B. Insights into C9ORF72-Related ALS/FTD from Drosophila and iPSC Models. Trends Neurosci 2018, 41, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Gal, J.; Zhu, H.; Jia, J. Motor Neuron Apoptosis and Neuromuscular Junction Perturbation Are Prominent Features in a Drosophila Model of Fus-Mediated ALS. Mol Neurodegener 2012, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-W.; Brent, J.R.; Tomlinson, A.; Shneider, N.A.; McCabe, B.D. The ALS-Associated Proteins FUS and TDP-43 Function Together to Affect Drosophila Locomotion and Life Span. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 4118–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasayama, H.; Shimamura, M.; Tokuda, T.; Azuma, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Mizuno, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Fujikake, N.; Nagai, Y.; Yamaguchi, M. Knockdown of the Drosophila Fused in Sarcoma (FUS) Homologue Causes Deficient Locomotive Behavior and Shortening of Motoneuron Terminal Branches. PLoS One 2012, 7, e39483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockett, R.J.; Radyuk, S.N.; Benes, J.J.; Orr, W.C.; Sohal, R.S. Phenotypic Effects of Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mutant Sod Alleles in Transgenic Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staveley, B.E.; Phillips, J.P.; Hilliker, A.J. Phenotypic Consequences of Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase Overexpression in Drosophila Melanogaster. Genome 1990, 33, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiguin, F.; Godena, V.K.; Romano, G.; D’Ambrogio, A.; Klima, R.; Baralle, F.E. Depletion of TDP-43 Affects Drosophila Motoneurons Terminal Synapsis and Locomotive Behavior. FEBS Lett 2009, 583, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-C.; Morton, D.B. Drosophila Lines with Mutant and Wild Type Human TDP-43 Replacing the Endogenous Gene Reveals Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination in Mutant Lines in the Absence of Viability or Lifespan Defects. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0180828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-C.; Hazelett, D.J.; Stewart, J.A.; Morton, D.B. Motor Neuron Expression of the Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel Cacophony Restores Locomotion Defects in a Drosophila, TDP-43 Loss of Function Model of ALS. Brain Res 2014, 1584, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.; Rouleau, G.A.; Dion, P.A.; Parker, J.A. Deletion of C9ORF72 Results in Motor Neuron Degeneration and Stress Sensitivity in C. Elegans. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Yang, S.-P.; Xie, L.; Kawano, T.; Fu, D.; Mukai, A.; Bohm, C.; Chen, F.; Robertson, J.; Suzuki, H.; et al. ALS Mutations in FUS Cause Neuronal Dysfunction and Death in Caenorhabditis Elegans by a Dominant Gain-of-Function Mechanism. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash, P.E.A.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Roberts, C.M.; Saldi, T.; Hutter, H.; Buratti, E.; Petrucelli, L.; Link, C.D. Neurotoxic Effects of TDP-43 Overexpression in C. Elegans. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 3206–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskoylu, S.N.; Yersak, J.; O’Hern, P.; Grosser, S.; Simon, J.; Kim, S.; Schuch, K.; Dimitriadi, M.; Yanagi, K.S.; Lins, J.; et al. Single Copy/Knock-in Models of ALS SOD1 in C. Elegans Suggest Loss and Gain of Function Have Different Contributions to Cholinergic and Glutamatergic Neurodegeneration. PLoS Genet 2018, 14, e1007682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; Le, W. Human Superoxide Dismutase 1 Overexpression in Motor Neurons of Caenorhabditis Elegans Causes Axon Guidance Defect and Neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Farr, G.W.; Hall, D.H.; Li, F.; Furtak, K.; Dreier, L.; Horwich, A.L. An ALS-Linked Mutant SOD1 Produces a Locomotor Defect Associated with Aggregation and Synaptic Dysfunction When Expressed in Neurons of Caenorhabditis Elegans. PLoS Genet 2009, 5, e1000350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, A.T.; Jakobs, C.E.; Ljubikj, T.; Huffels, C.F.M.; Cañizares Luna, M.; Vieira de Sá, R.; Adolfs, Y.; de Wit, M.; Rutten, D.H.; Kaal, M.; et al. Molecular Pathology, Developmental Changes and Synaptic Dysfunction in (Pre-) Symptomatic Human C9ORF72-ALS/FTD Cerebral Organoids. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2024, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, Y.; Ross, J.P.; Alipour, P.; Castonguay, C.-É.; Li, B.; Catoire, H.; Rochefort, D.; Urushitani, M.; Takahashi, R.; Sonnen, J.A.; et al. Spinal Cord Extracts of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Spread TDP-43 Pathology in Cerebral Organoids. PLoS Genet 2023, 19, e1010606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebényi, K.; Wenger, L.M.D.; Sun, Y.; Dunn, A.W.E.; Limegrover, C.A.; Gibbons, G.M.; Conci, E.; Paulsen, O.; Mierau, S.B.; Balmus, G.; et al. Human ALS/FTD Brain Organoid Slice Cultures Display Distinct Early Astrocyte and Targetable Neuronal Pathology. Nat Neurosci 2021, 24, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.D.; DuBreuil, D.M.; Devlin, A.-C.; Held, A.; Sapir, Y.; Berezovski, E.; Hawrot, J.; Dorfman, K.; Chander, V.; Wainger, B.J. Human Sensorimotor Organoids Derived from Healthy and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Stem Cells Form Neuromuscular Junctions. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Shi, Q.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lang, J.; Wen, S.; Liu, X.; Cheng, T.-L.; Lei, K. Neuromuscular Organoids Model Spinal Neuromuscular Pathologies in C9orf72 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 113892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Tharkeshwar, A.K.; Fumagalli, L.; Contardo, M.; Van Schoor, E.; Fazal, R.; Thal, D.R.; Chandran, S.; Mancuso, R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; et al. A Toxic Gain-of-Function Mechanism in C9orf72 ALS Impairs the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway in Neurons. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2023, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, P.; Risse, E.; Tyzack, G.E.; Mitchell, J.S.; Taha, D.M.; Chen, Y.-R.; Newcombe, J.; Collinge, J.; Sidle, K.; Patani, R. Distinct Responses of Neurons and Astrocytes to TDP-43 Proteinopathy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 2020, 143, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahsen, B.F.; Nalluru, S.; Morgan, G.R.; Farrimond, L.; Carroll, E.; Xu, Y.; Cramb, K.M.L.; Amein, B.; Scaber, J.; Katsikoudi, A.; et al. C9orf72-ALS Human iPSC Microglia Are pro-Inflammatory and Toxic to Co-Cultured Motor Neurons via MMP9. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.L.; Goutman, S.A.; Petri, S.; Mazzini, L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Lancet 2022, 400, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C.; Mazzini, L.; Mora, G. ; PARALS study group Phenotypic Heterogeneity of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Population Based Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011, 82, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Tian, J.; Fan, D. Differentiating Slowly Progressive Subtype of Lower Limb Onset ALS From Typical ALS Depends on the Time of Disease Progression and Phenotype. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 872500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, L.; Vandriel, S.; Elman, L.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Powers, J.; Boller, A.; Wood, E.M.; Woo, J.; McMillan, C.T.; Rascovsky, K.; et al. ALS-Plus Syndrome: Non-Pyramidal Features in a Large ALS Cohort. J Neurol Sci 2014, 345, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Logroscino, G.; Hardiman, O.; Swingler, R.; Mitchell, D.; Beghi, E.; Traynor, B.G. ; On Behalf of the Eurals Consortium Prognostic Factors in ALS: A Critical Review. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis 2009, 10, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-K.; Liu, X.; Sandner, J.; Pasmantier, M.; Andrews, J.; Rowland, L.P.; Mitsumoto, H. Study of 962 Patients Indicates Progressive Muscular Atrophy Is a Form of ALS. Neurology 2009, 73, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riku, Y.; Atsuta, N.; Yoshida, M.; Tatsumi, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Mimuro, M.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, M.; Senda, J.; Nakamura, R.; et al. Differential Motor Neuron Involvement in Progressive Muscular Atrophy: A Comparative Study with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, P.G.; Evans, J.; Knopp, M.; Forster, G.; Hamdalla, H.H.M.; Wharton, S.B.; Shaw, P.J. Corticospinal Tract Degeneration in the Progressive Muscular Atrophy Variant of ALS. Neurology 2003, 60, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Brignolio, F.; Leone, M.; Mortara, P.; Rosso, M.G.; Tribolo, A.; Schiffer, D. A Survival Analysis of 155 Cases of Progressive Muscular Atrophy. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 1985, 72, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, C.; Scelsa, S.N.; Macgowan, D.J.L. The Clinical Course of Progressive Bulbar Palsy. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010, 11, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRINGLE, C.E.; HUDSON, A.J.; MUNOZ, D.G.; KIERNAN, J.A.; BROWN, W.F.; EBERS, G.C. PRIMARY LATERAL SCLEROSIS: CLINICAL FEATURES, NEUROPATHOLOGY AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA. Brain 1992, 115, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Miller, R.G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T.L. ; World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases El Escorial Revisited: Revised Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.; Dengler, R.; Eisen, A.; England, J.D.; Kaji, R.; Kimura, J.; Mills, K.; Mitsumoto, H.; Nodera, H.; Shefner, J.; et al. The Awaji Criteria for Diagnosis of ALS. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44, 456–457, author reply 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnia, M.; Kelly, J.J. Role of Electromyography in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 1991, 14, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.; Dengler, R.; Eisen, A.; England, J.D.; Kaji, R.; Kimura, J.; Mills, K.; Mitsumoto, H.; Nodera, H.; Shefner, J.; et al. Electrodiagnostic Criteria for Diagnosis of ALS. Clin Neurophysiol 2008, 119, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. Managed Care Considerations to Improve Health Care Utilization for Patients with ALS. Am J Manag Care 2023, 29, S120–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, G.; Lacomblez, L.; Meininger, V. A Controlled Trial of Riluzole in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994, 330, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, M.K. Riluzole and Edaravone: A Tale of Two Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Drugs. Med Res Rev 2019, 39, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing Group; Edaravone (MCI-186) ALS 19 Study Group Safety and Efficacy of Edaravone in Well Defined Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol 2017, 16, 505–512. [CrossRef]

- Lunetta, C.; Moglia, C.; Lizio, A.; Caponnetto, C.; Dubbioso, R.; Giannini, F.; Matà, S.; Mazzini, L.; Sabatelli, M.; Siciliano, G.; et al. The Italian Multicenter Experience with Edaravone in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol 2020, 267, 3258–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, S.; Maier, A.; Steinbach, R.; Grosskreutz, J.; Koch, J.C.; Sarikidi, A.; Petri, S.; Günther, R.; Wolf, J.; Hermann, A.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Long-Term Intravenous Administration of Edaravone for Treatment of Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, S.; Macklin, E.A.; Hendrix, S.; Berry, J.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Maiser, S.; Karam, C.; Caress, J.B.; Owegi, M.A.; Quick, A.; et al. Trial of Sodium Phenylbutyrate–Taurursodiol for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.M.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Genge, A.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G.; Bucelli, R.C.; Chiò, A.; Van Damme, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Glass, J.D.; et al. Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.; Cudkowicz, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Andersen, P.M.; Atassi, N.; Bucelli, R.C.; Genge, A.; Glass, J.; Ladha, S.; Ludolph, A.L.; et al. Phase 1-2 Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Qu, H.; Liao, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Kang, M.; et al. RAG-17, a Novel siRNA Therapy for SOD1-ALS: Safety and Preliminary Efficacy from a First-in-Human Trial (S5. 003). Neurology 2025, 104, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstein, C.G.; Miller, J.S.; Cao, Q.; McKenna, D.H.; Hippen, K.L.; Curtsinger, J.; Defor, T.; Levine, B.L.; June, C.H.; Rubinstein, P.; et al. Infusion of Ex Vivo Expanded T Regulatory Cells in Adults Transplanted with Umbilical Cord Blood: Safety Profile and Detection Kinetics. Blood 2011, 117, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstein, C.G.; Miller, J.S.; McKenna, D.H.; Hippen, K.L.; DeFor, T.E.; Sumstad, D.; Curtsinger, J.; Verneris, M.R.; MacMillan, M.L.; Levine, B.L.; et al. Umbilical Cord Blood-Derived T Regulatory Cells to Prevent GVHD: Kinetics, Toxicity Profile, and Clinical Effect. Blood 2016, 127, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudkowicz, M.E.; Lindborg, S.R.; Goyal, N.A.; Miller, R.G.; Burford, M.J.; Berry, J.D.; Nicholson, K.A.; Mozaffar, T.; Katz, J.S.; Jenkins, L.J.; et al. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Induced to Secrete High Levels of Neurotrophic Factors in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2022, 65, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Nakayama, L.; Blum, J.A.; Akiyama, T.; Boeynaems, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Couthouis, J.; Tassoni-Tsuchida, E.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Bassik, M.C.; et al. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Reveals v-ATPase as a Drug Target to Lower Levels of ALS Protein Ataxin-2. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmada, S.J.; Serio, A.; Arjun, A.; Bilican, B.; Daub, A.; Ando, D.M.; Tsvetkov, A.; Pleiss, M.; Li, X.; Peisach, D.; et al. Autophagy Induction Enhances TDP43 Turnover and Survival in Neuronal ALS Models. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, D.V.; Kansagra, K.A.; Momin, T.; Patel, H.B.; Jansari, G.A.; Bhavsar, J.; Shah, C.; Patel, J.M.; Ghoghari, A.; Barot, A.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of the Oral NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor ZYIL1: First-in-Human Phase 1 Studies (Single Ascending Dose and Multiple Ascending Dose). Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2023, 12, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.S.; Bradley, W.G.; Chaverri, D.; Hernández-Barral, M.; Mascias, J.; Gamez, J.; Gargiulo-Monachelli, G.M.; Moussy, A.; Mansfield, C.D.; Hermine, O.; et al. Long-Term Survival Analysis of Masitinib in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2021, 14, 17562864211030365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, M.; Wuu, J.; Andersen, P.M.; Bucelli, R.C.; Andrews, J.A.; Otto, M.; Farahany, N.A.; Harrington, E.A.; Chen, W.; Mitchell, A.A.; et al. Design of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial of Tofersen Initiated in Clinically Presymptomatic SOD1 Variant Carriers: The ATLAS Study. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.D.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Windebank, A.J.; Staff, N.P.; Owegi, M.; Nicholson, K.; McKenna-Yasek, D.; Levy, Y.S.; Abramov, N.; Kaspi, H.; et al. NurOwn, Phase 2, Randomized, Clinical Trial in Patients with ALS: Safety, Clinical, and Biomarker Results. Neurology 2019, 93, e2294–e2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, R.; Peterson, K.; Helfand, M. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Skeletal Muscle Relaxants for Spasticity and Musculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004, 28, 140–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garuti, G.; Rao, F.; Ribuffo, V.; Sansone, V.A. Sialorrhea in Patients with ALS: Current Treatment Options. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis 2019, 9, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelica, B.; Petri, S. Narrative Review of Diagnosis, Management and Treatment of Dysphagia and Sialorrhea in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol 2024, 271, 6508–6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipe, C.B.; Carreira, N.R.; Reis-Pina, P. Optimizing Breathlessness Management in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Insights from a Comprehensive Systematic Review. BMC Palliat Care 2024, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, A.; Nijboer, F.; Matuz, T.; Kübler, A. Depression and Anxiety in Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Epidemiology and Management. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fralick, M.; Sacks, C.A.; Kesselheim, A.S. Assessment of Use of Combined Dextromethorphan and Quinidine in Patients With Dementia or Parkinson Disease After US Food and Drug Administration Approval for Pseudobulbar Affect. JAMA Internal Medicine 2019, 179, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S. Pain in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Narrative Review. JYMS 2022, 39, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Promoter(s)/ Model |

Species | Pathology | Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebrates | |||||

|

SOD1 G93A, G86R, G37R, A4V, D90A |

Human SOD1 | Mouse Rat |

Motor neuron loss, iron accumulation, gliosis, axon degeneration, mitochondrial damage | Model for fALS, well-characterized | [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] |

|

TDP-43 Knock-in, A315T, M337V, Q331K, G348C |

BAC, mPrp, mThy1 | Mouse Rat |

Cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates, motor deficits, neuroinflammation | Models TDP-43 pathology | [71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

|

FUS Knock-out, overexpression, R521C, R521G, P525L |

Tau, mPrp, CAG | Mouse Rat |

Cytoplasmic FUS aggregates, nuclear clearance, motor neuron loss | Found in early-onset ALS, shares features with TDP-43 | [78,79,80,81,82,83,84] |

|

C9ORF72 [100-1000]n [500]n [64]n [147]n [450]n |

BAC, AAV | Mouse | RNA foci, DPRs, nucleocytoplasmic transport defects, TDP-43 pathology, p62 in aggregates | Most common genetic cause of ALS and FTD | [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| Invertebrates | |||||

|

Sod1, tdp-43, fus, c9orf72 |

Morpholino knockdown or gene overexpression; CRISPR/Cas9; injections of human mRNA | Zebrafish | Motor axon length decrease, swimming deficits, synaptic abnormalities | Transparent embryos, live imaging, high-throughput | [93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| TDP-43, FUS, SOD1, DPRs | Gene mutants or overexpression; UAS-Gal4 system for expression of human transgenes | Drosophila melanogaster | Motor neuron degeneration, locomotor defects, inclusion formation, axonal transport defects | Fast generation, conserved pathways |

[99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108] |

| TDP-43, SOD1, DPRs | Knockdown; human transgene expression | Caenorhabditis elegans | Locomotor defects, neurodegeneration, cytosolic aggregates, axonal abnormalities | Genetic screens and modifier identification | [109,110,111,112,113,114] |

| DIAGNOSIS | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| Definite ALS | Presence of both UMN and LMN signs in 3 anatomical regions. |

| Probable ALS | Presence of both UMN and LMN signs in ≥2 anatomical regions, with UMN signs observed rostral to LMN signs, is suggestive of ALS. |

| Probable ALS, supported by laboratory results | Presence of both UMN and LMN signs in 1 region, with EMG evidence of LMN involvement in at least 1 other region. |

| Possible ALS | Presence of UMN and LMN signs in a single region, or UMN signs in 2 or 3 regions without LMN involvement. |

| Anatomical regions used for disease stratification: Bulbar, cervical, thoracic, lumbar. ALS, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; UMN, upper motor neuron; LMN, lower motor neuron. | |

| NCT NUMBER | THERAPY | MECHANISM/ TARGET | PHASE | STATUS | TYPE | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05903690 | RAG-17 | siRNA targeting the SOD1 gene | Early Phase I | Completed | Interventional | [150] |

| NCT06849609 | VGN-R13 | AAV vector | Early Phase I | Recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT06645197 | SNUG01 | AAV vector | Early Phase I | Not yet Recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT06665165 | AMX0114 | AMX0114 ASO | Phase I | Recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT06307301 | Abatacept & IL-2 | Reduction of Treg numbers & suppression | Phase I | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT05695521 | CK0803 | Allogeneic Tregs (cord blood) | Phase I | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | [151,152,153] |

| NCT04948645 | Fosigotifator | ISR modulator (eIF2B activator) | Phase I | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT05633459 | QRL-201 | STMN2 ASO | Phase I | Recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT03626012 | BIIB-078 | C9orf72 ASO | Phase I | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT04494256 | BIIB-105 | ATXN2 ASO (TDP-43) | Phase I/II | Terminated | Interventional | [154] |

| NCT02238626 | MN-166 | Anti-inflammatory (TLR4 inhibitor) | Phase II | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT03456882 | RNS60 | Mitochondrial metabolic enhancer | Phase II | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT04569435 | ANX005 | Anti-C1q monoclonal antibody | Phase II | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT05039099 | AP-101 | Anti-misfolded SOD1 antibody | Phase II | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT03359538 | Rapamycin | Autophagy enhancers | Phase II | Completed | Interventional | [155] |

| NCT05981040 | ZYIL1 (Usnoflast) | NLRP3 inhibitor | Phase II | Completed | Interventional | [156] |

| NCT04615923 | Pridopidine | Sigma-1 receptor agonist | Phase II/III | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT04297683 | DNL343 | ISR modulator | Phase II/III | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT04220190 | RAPA-501 | Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy | Phase II/III | Recruiting | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT04414345 | CNM-Au8 | Nascent nanocrystal therapy | Phase II/III | Completed | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT02588677 | Masitinib in combination with riluzole | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Phase II/III | Completed | Interventional | [157] |

| NCT04856982 | Tofersen | SOD1 ASO | Phase III | Active, not recruiting | Interventional | [158] |

| NCT04944784 | Reldesemtiv | Troponin activator | Phase III | Terminated | Interventional | N/A |

| NCT03280056 | NurOwn | MSC-NTF cell therapy | Phase III | Completed | Interventional | [159] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).