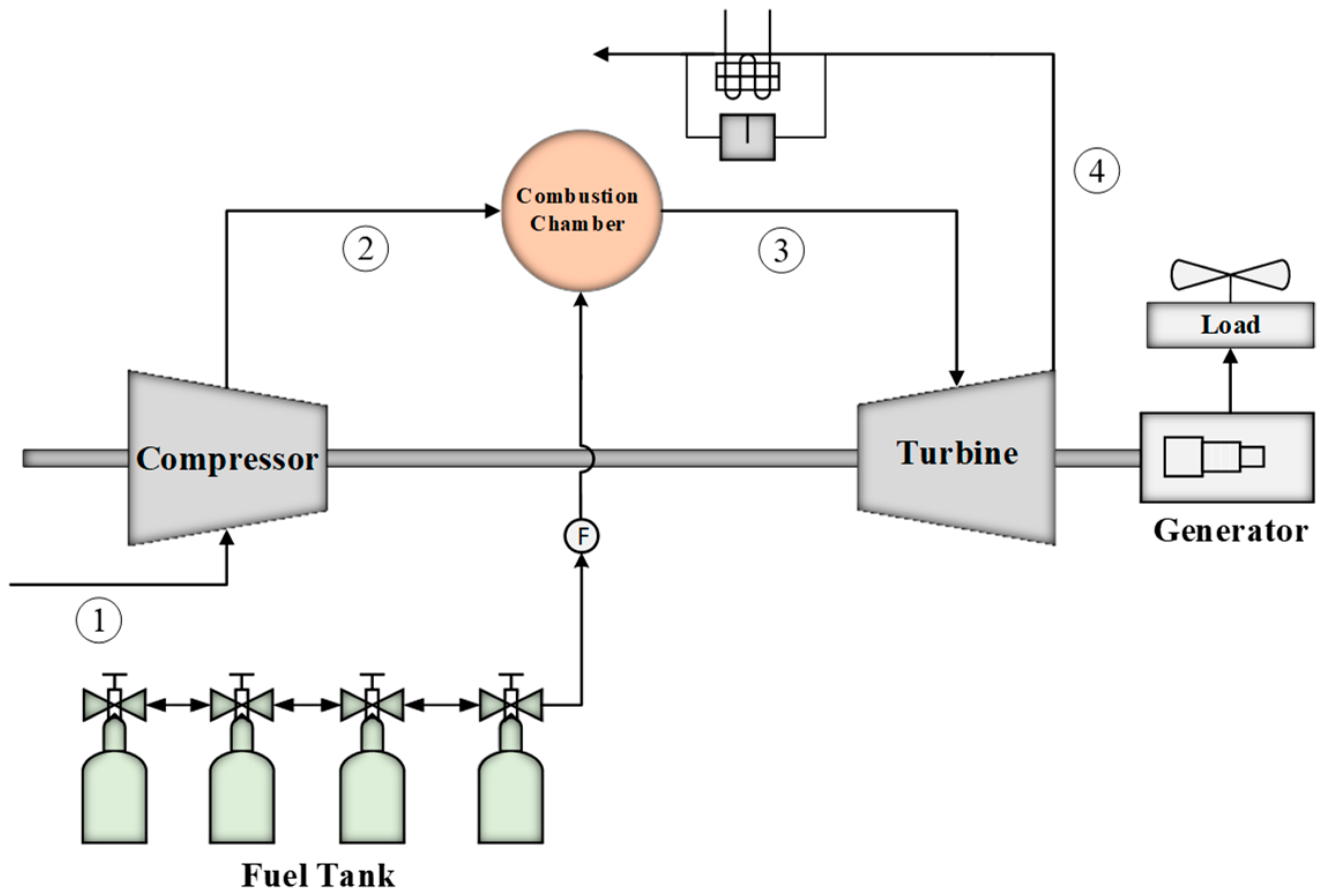

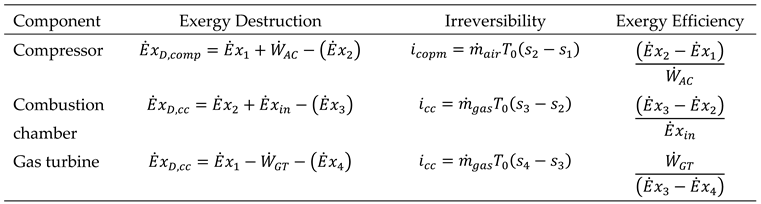

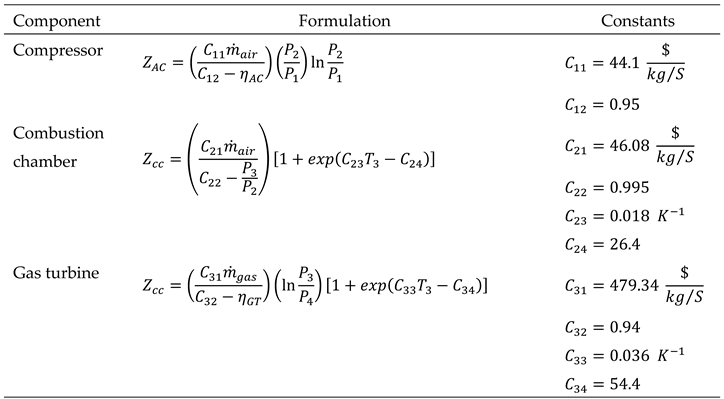

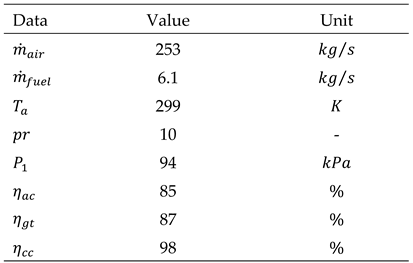

2.1. Energy Analysis

The major part of energy modeling is applying mass and energy balance equations. In this section, the thermodynamic relations governing the gas turbine are analyzed [

16].

Free Stream: Temperature and static pressure are two crucial factors in analyzing the behavior of fluid flow in the Earth’s atmosphere. These parameters undergo significant changes with increasing altitude above sea level. Up to an altitude of approximately 11 kilometers, specific mathematical relationships, expressed as Equations (1) and (2), describe the variation of temperature and pressure with altitude.

The enthalpy and entropy of the air entering the compressor are considered according to equations (3) and (4) below [

17].

Compressor: Air enters the compressor and is compressed in a polytropic process. The actual work consumed by the compressor during the compression process is calculated using equation (5).

The isentropic efficiency of the compressor is also defined as the ratio of the isentropic work to the actual work of the compressor and is determined by equation (6).

In an isentropic process,

. Additionally, for calculating enthalpy and entropy, the following equations are used (equations (7) and (8)) [

2]:

Combustion Chamber: The heat balance equation in the combustion chamber is expressed as equation (9) [

18].

where

is the enthalpy at the outlet of the combustion chamber. Additionally,

and

is the efficiency of the combustion chamber. The outlet pressure is also obtained as follows (equation (10)):

where is the pressure drop across the combustion chamber. In equation (9), the outlet enthalpy and are obtained by solving the combustion equations.

Combustion Equation: The primary equation in the combustion chamber is considered based on the chemical equation for various hydrocarbon fuels as equation (11) [

19].

By balancing the species, the following system of equations (equation (12)) is obtained:

Where,

is the mole fraction of each species and is calculated as follows (equation (13)):

In the system of equations (12), the values of

,

,

and

are known. This system of equations includes 11 unknowns. To solve the above equation and obtain the values of n and

, the following auxiliary equations and equilibrium constants are required [

20].

In addition,

the equilibrium constant associated with each equation can be obtained from the polynomial coefficients presented below (Equation (15)) [

20]:

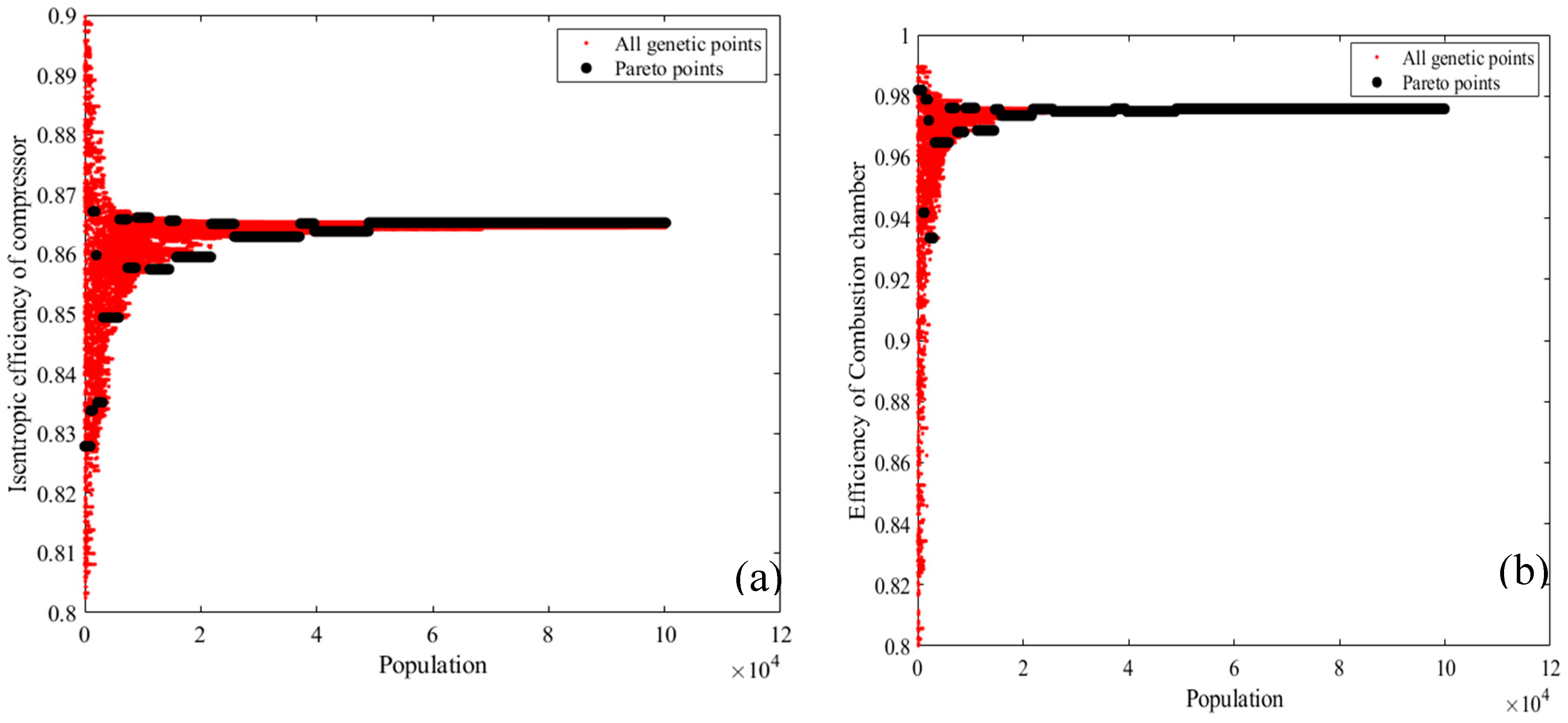

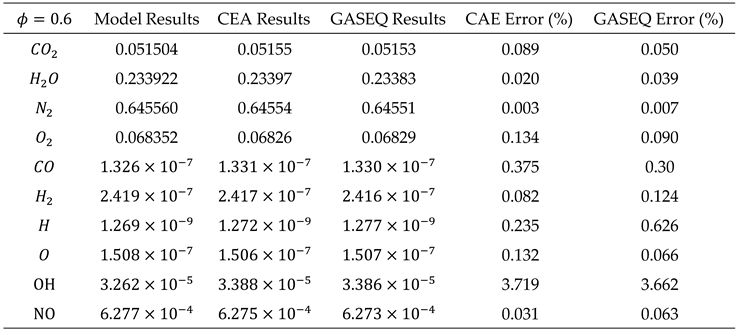

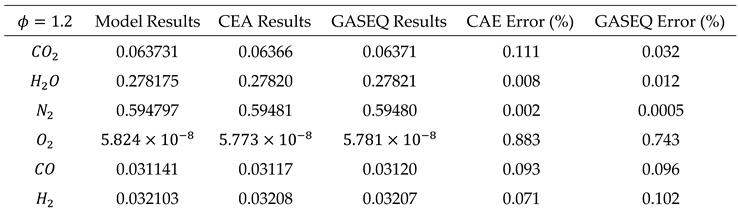

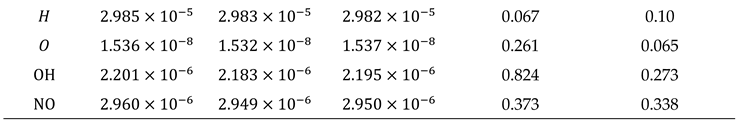

Table 1 shows the values of the coefficients required to calculate the equilibrium constants in Equation (15).

In order to linearize the system of equations (12), the following constants were used (Equation (16)).

Considering the defined constants and substituting them into the system of equations (Equation (12)), the atomic species balance equations are rewritten as follows. Also, the sum of the mole fractions of the combustion products is equal to 1. Therefore, the new system of equations is written as Equation (17).

Additionally, the auxiliary equations are rewritten as follows, so that they can be used in the system of equations (17) (Equation (18)).

By substituting the aforementioned relations into the system of equations (17), the final system of equations (19) is obtained. The following equations consist of 4 equations and 5 unknowns (

and

). Therefore, the energy balance equation between the reactants and combustion products must also be added to the following equations.

The system of equations (19) can be expressed as the following relation (Equation (20)).

The system of equations shown in Equation (20) can be solved using the Newton-Raphson iterative method. If the solution vector of Equation (20)

, is denoted as the left-hand side of the equation

, for a first-guess solution vector close to

, is expanded using a Taylor series, and second-order and higher partial derivatives are neglected. Thus, we have:

In Equation (21), .

Equation (21) can be rewritten in matrix form as

, where matrix A is actually the Jacobian matrix of the system, as defined in equation (22) [

22].

To solve this system of equations, the Gaussian elimination method, as detailed in equation (23), was employed. The resulting vector from this method was then used as the initial point for optimizing the problem’s initial vector [

22].

where k is the number of iterations. The iterative process continues until the value of

is within a predefined tolerance (ε=0.001) of the target value. The maximum number of iterations is limited to 20. It is worth noting that, in addition to the iterative formula, the choice of the initial value significantly impacts the convergence rate and success of the optimization process. The initial solution vector

, were determined by modeling incomplete combustion of fuel at temperatures below 1000 Kelvin.

Initial Estimation of Mole Fractions: To obtain the mole fraction values, it is necessary to initially estimate the four mole fractions

. Therefore, the combustion equation is considered as follows (Equation (24)):

By writing balance equations for each species, the system of equations (25) can be obtained as follows:

To simplify the equations, the following four constants are defined (Equation (26)).

Using the two auxiliary equations)

( and substituting them into the above equations, a relationship in terms of the variable is obtained as follows (Equation(27)).

By guessing the value of and using the energy balance equation, the only unknown in the above equation is N. The value of N can also be obtained by considering the following two cases.

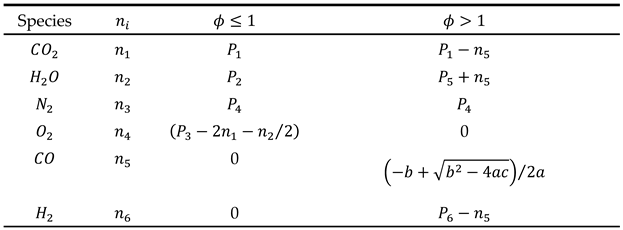

Case 1: In fuel-lean combustion mixtures (ϕ < 1), due to the deficiency of oxygen, we assume that carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2) are completely consumed in the reaction and are not present in the combustion products. Consequently, by setting the number of moles of CO and H2 to zero (i.e.), the number of unknowns in the mass balance equations is reduced, simplifying the solution of the equation system.

Case 2: In fuel-rich combustion mixtures (ϕ > 1), due to the excess of fuel relative to air, all available oxygen is consumed, leaving no residual oxygen in the combustion products (i.e.

). To accurately determine the composition of the incomplete combustion products under these conditions, in addition to atomic balance equations, it is necessary to consider the equilibrium reaction between the products CO2, H2O, CO, and H2. This equilibrium reaction, also known as the water-gas reaction, is represented by equation (28).

The numerical value of the equilibrium constant for the water-gas shift reaction is denoted by KT and is presented in equation (29).

The equilibrium constant equation for

, is obtained using Equation (30).

By writing balance equations for each species, the final equations for both cases can be summarized in the following table.

The parameters in

Table 2 are calculated as follows (Equation (31)).

Also, the coefficients a, b, and c are obtained as follows (Equation (32)).

By calculating the values of N and using the relation

, the value of N is obtained. Therefore, by calculating the value of N to solve Equation (27), it is assumed that the initial mole fraction of the combustion product is 100%, i.e.,

. This clearly causes

to be greater than 0. Then, Equation (33) is used to iterate

until

becomes less than 0. At this point,

will be close to its exact value.

To achieve greater accuracy in the calculations, the values obtained from the initial iterative method can be used as an initial guess in the Newton-Raphson method. This numerical method, whose formula is presented in equation (34), allows us to obtain a more accurate and faster solution.

When the absolute value ratio of

to

is less than 0.001, it can be considered that the exact value of

has been successfully obtained. The initial values of the mole fractions,

and

can be obtained using Equation (25) [

19].

Thermodynamic Property Calculations: Accurate simulation of gas turbine engine performance necessitates precise modeling of the thermal properties of combustion products. By examining and comparing various models for specific heat capacity at constant pressure (cp) and volume (cv), it was found that increasing the complexity of these models leads to a decrease in the calculated thermal efficiency of a standard air dual cycle and a closer convergence of results with the actual thermal efficiency of diesel engines.

Many studies have simplified the thermal properties of combustion products by assuming a linear relationship with temperature, neglecting the effects of pressure and fuel-air ratio. For instance, Lamas’ model considered only five primary combustion product components (O2, N2, CO

2, H2O, and SO2) and disregarded the variation of thermal properties with pressure. These simplifications are made despite the fact that complex chemical reactions occur at high combustion chamber temperatures, leading to a significant increase in the number of combustion product components. Furthermore, the concentration of these components is strongly dependent on temperature and fuel-air ratio. Consequently, neglecting these complexities compromises the accuracy of simulation models [

22,

23].

In many studies, for the sake of computational simplicity, the constituent gases of a combustion mixture are assumed to behave as ideal gases. The thermodynamic properties of these gases are typically obtained from tables or empirical correlations. In this study, we have adopted a comprehensive data-based approach developed by Gordon and McBride. This method relies on fitting NASA polynomials to experimental data. Utilizing these polynomials and considering the mole fractions of each component in the mixture, determined through chemical equilibrium calculations, we can calculate the thermodynamic properties of the mixture using the Gibbs-Dalton law [

24]. Equation (35) presents the relationships for calculating molar mass, molar specific enthalpy, molar internal energy, and molar entropy [

22].

While individual components of a gas mixture can be considered as ideal gases, the overall behavior of the gas mixture does not necessarily follow the ideal gas laws. For instance, the specific internal energy

of a gas mixture is not solely a function of temperature. To more accurately describe the behavior of such gases, modifications to the ideal gas equation of state are required, such as adjusting the universal gas constant (as seen in Equation (36)) [

22].

Specific heat capacity at constant pressure is defined as the partial derivative of internal energy with respect to temperature under isobaric conditions. This quantity represents a system’s ability to absorb heat and increase its temperature at constant pressure, and is expressed by the differential equation (37).

Based on Equation (36), the specific enthalpy of the gas mixture can be expressed as follows (Equation (38)):

By substituting the relationships, the specific heat capacity is calculated using Equation (39).

The second and third terms on the right-hand side of the above equation represent the kinetic effects of dissociation reactions on the molecular composition of combustion products at elevated temperatures. However, at lower temperature regimes where dissociation reactions are less significant, equation (40) can be approximated by a simpler model.

To determine the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (

) as defined by equation (40), it is necessary to calculate the partial derivatives of the mole fractions (

) of each chemical species in the gas mixture with respect to temperature. This can be achieved by differentiating the chemical equilibrium equation (20) with respect to temperature, resulting in a set of partial differential equations for components

,

,

and

(equation (41)).

By calculating the derivatives expressed in the equation, the following matrix is finally formed, and the method of solving this equation is similar to Equation (20) (Equation (42)).

To obtain the derivatives of functions with respect to pressure, a process similar to calculating the derivative with respect to temperature is performed, and the solution method is also similar to the previous method (Equation (43)).

Also, the enthalpy, specific heat capacity, and entropy of each component are calculated as follows (Equations (44-47)) [

22].

The coefficients presented in the above equations are extracted from reference [

25] for temperatures ranging from 300 to 1000 Kelvin and from 1000 to 3000 Kelvin. Therefore, the specific volume is equal to (Equation (48)):

The derivative of specific volume with respect to temperature at constant pressure (Equation (49)):

The derivative of specific volume with respect to pressure at constant temperature (Equation (50)) [

22]:

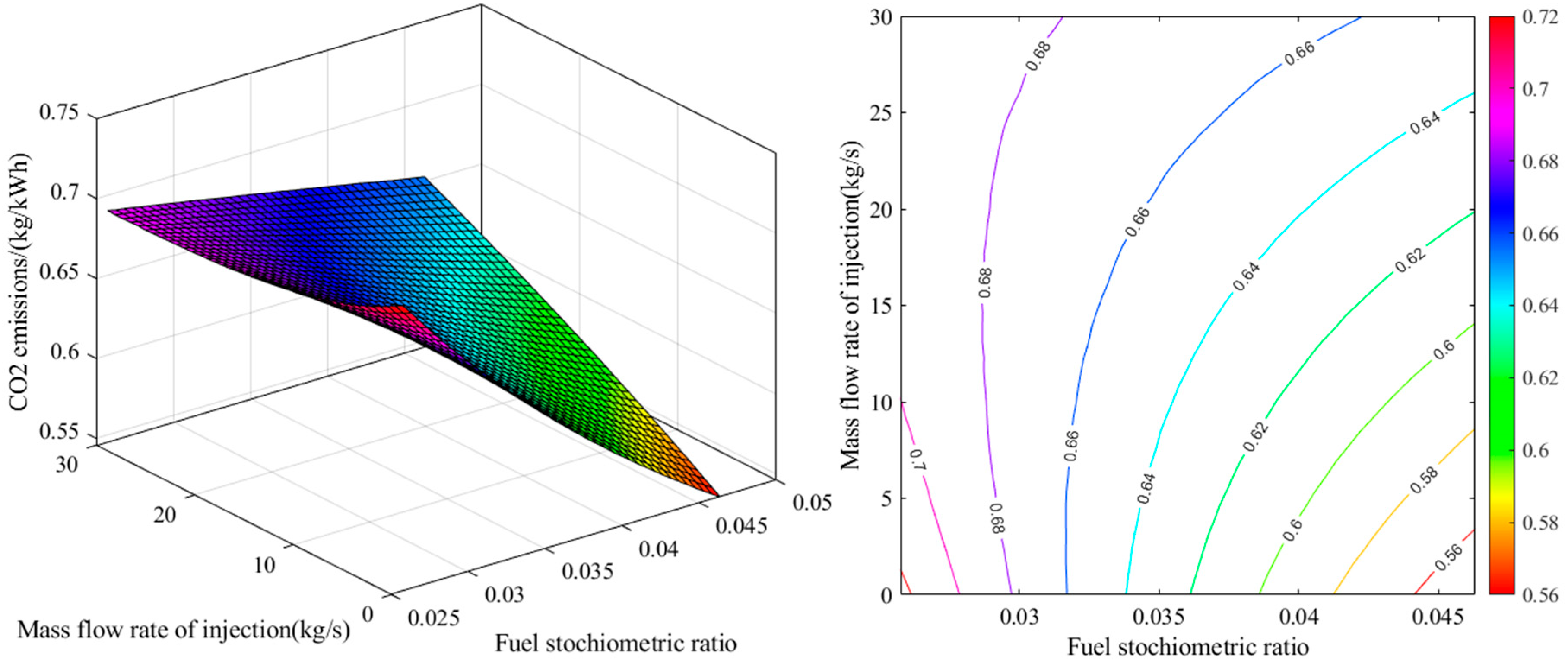

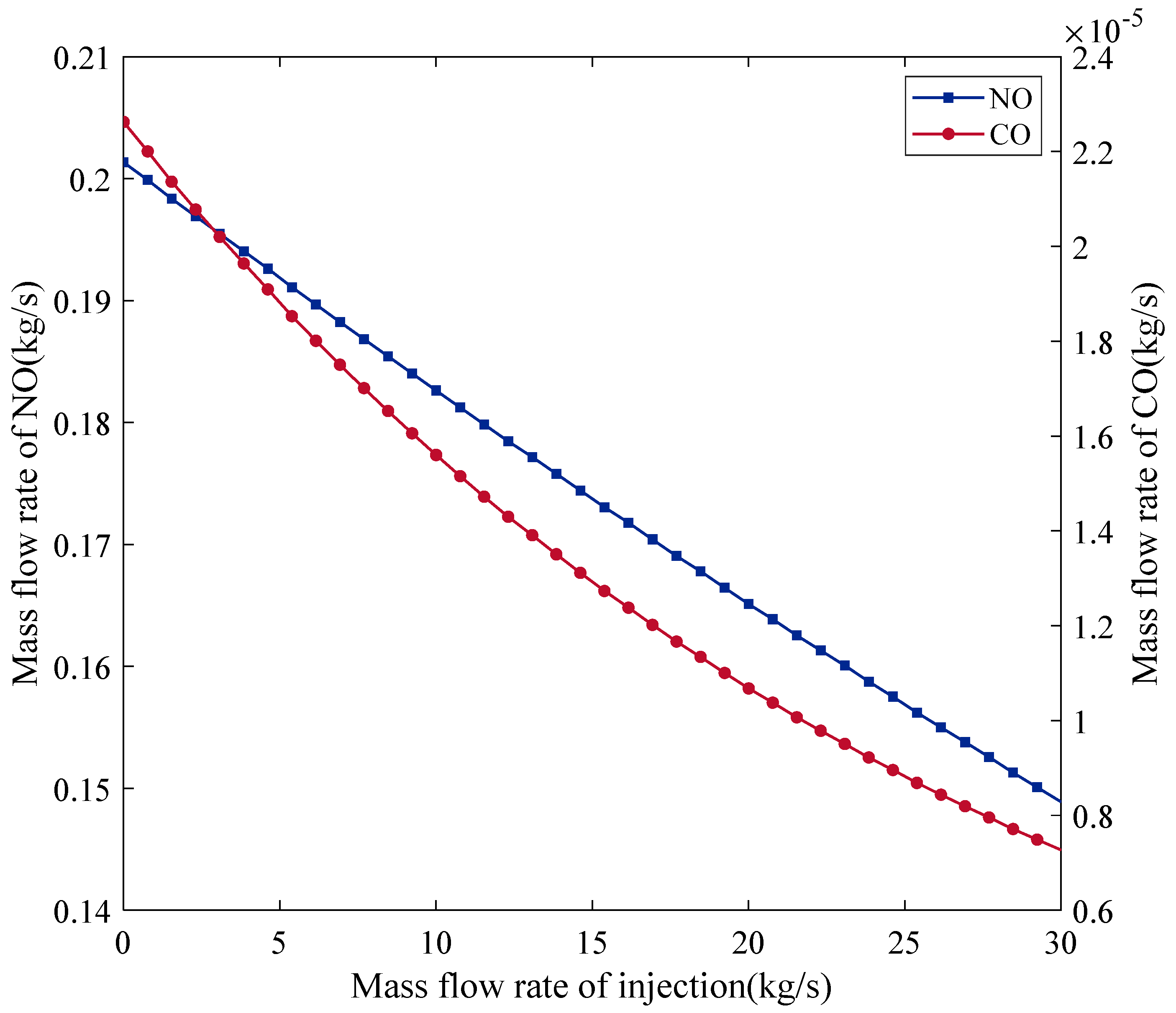

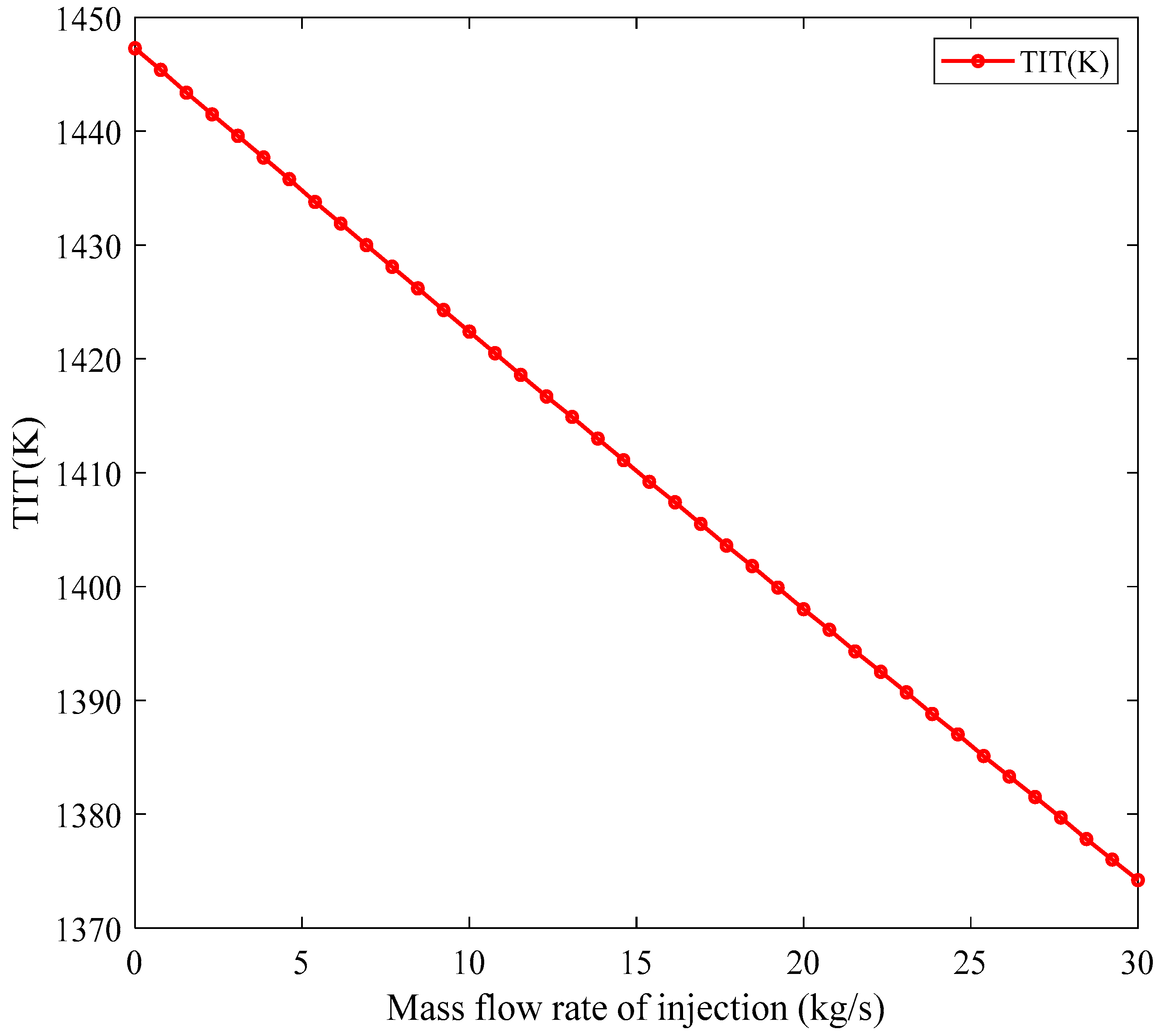

Steam Injection into the Combustion Chamber: Steam injection into the combustion chamber of gas turbines is an effective method for reducing combustion-generated pollutants, especially nitrogen oxides (NOx), and improving turbine performance. Therefore, this paper aims to complete the described algorithm and to include the effects of steam injection on the combustion process in the developed model. With steam injection into the combustion chamber, the combustion equation is rewritten as Equation (51).

The amount of

, the percentage of steam injection into the combustion chamber, is obtained using Equation (52) [

26].

Therefore, to simulate the effects of steam injection into the combustion chamber, the value of must be specified. In this case, the species balance equation (Equation 12) is modified considering the value of .

Energy Balance Equation: The energy balance equation for the control volume of the combustion chamber is obtained according to Equation (53) [

27].

Also, considering the effects of steam injection, we have (Equation 54):

In this relation,

and it is assumed that the amount of heat transferred from the combustion chamber is equal to 2% of the lower heating value of the fuel, and its value is calculated using Equation (55) [

28].

Also,

is the molar enthalpy of the fuel at the inlet fuel temperature. The inlet fuel temperature is considered to be the same as the ambient temperature. According to the problem assumptions, the inlet air and combustion products are considered as an ideal gas mixture. Therefore,

and

are calculated using the following relations.

is also the enthalpy of steam at the desired temperature (Equations (57-58)).

Finally, a system of equations with 5 equations and 5 unknowns is obtained. Solving the above equations ends with assuming an initial value for or and establishing the energy balance condition.

Turbine: The work produced by the turbine during the isentropic expansion process is obtained using Equation (59):

Isentropic efficiency of a turbine is a measure of turbine performance, indicating how closely the actual turbine operation approaches an ideal, reversible process. It is defined as the ratio of the actual work output of the turbine to the ideal work output under isentropic conditions (i.e., without energy losses due to friction or heat transfer). This efficiency is calculated using Equation (60).

In the isentropic process in the turbine, .

Finally, the energy efficiency is obtained by Equation (61) [

2].

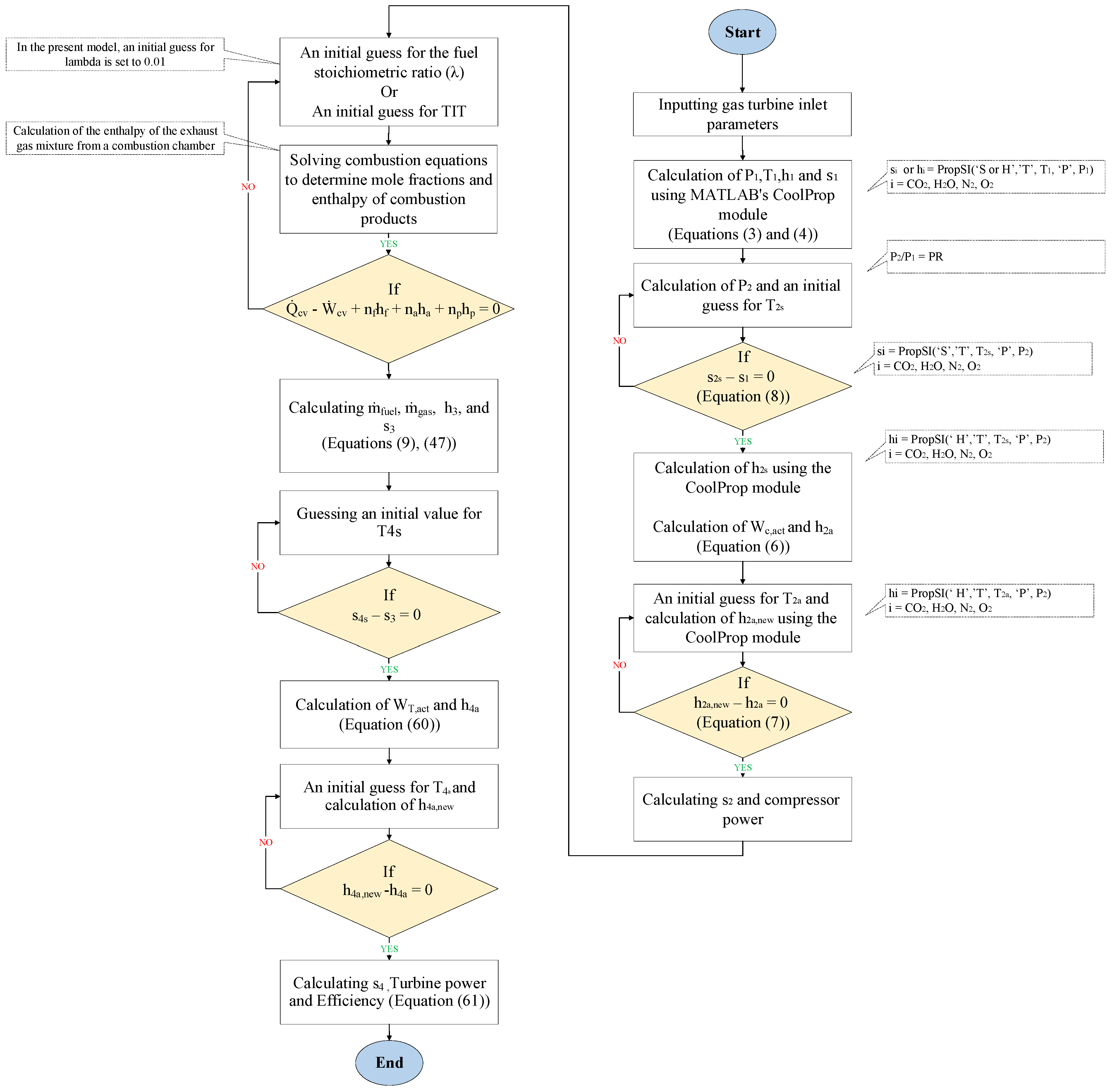

Figure 2 shows the algorithm for solving the energy equations.