1. Introduction

Nasality is a form of a disturbed resonance in speech. In normal conditions air exhaled during speech is utilized to produce vowels when the space between pharynx and nasal cavity is closed. Appropriate closing is possible thanks to the function of velopharyngeal muscle. Some medical conditions may lead to inappropriate function of the muscle and enable air stream leakage from oral cavity to the nose. The sound perception created in such conditions is heard as open nasality (rhinolalia aperta). The phenomenon of various degrees is mostly seen in inborn orofacial congenital defects, complete or submucous palate cleft, short palate, or acquired conditions like scars after surgeries or radiotherapy, and fistulas. In other cases incomplete velopharyngeal closure may be caused by palate immobility associated with pathologies located in central nervous system and involving cranial nerves or in some infectious diseases.

Speech production is strictly controlled by central nervous system in conjunction with hearing, which is referred to as auditory control of voice and speech. This complex process takes place as a result of cooperation between laryngeal muscles, central mechanisms of self-regulation of amplitude, frequency, rhythm and timbre of the voice as well as the biomechanics of abdomen, chest and the muscles of oral cavity, including palate. When the auditory control is disturbed by hearing impairment, the function of velopharyngeal muscle may be incomplete, leading to perception of nasality. Numerous publications can be found in the literature that describe the mechanisms of nasality in hearing impaired individuals.

Assessment of nasality can be subjective and objective. Subjective assessment is perceptual and in clinical practice is usually performed by experienced phoniatricians, audiologists or speech therapists. Objective measures include aerodynamic methods including nasometry, rhinospirometry and acoustic methods including spectrography of “i”vowel (SPG) and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The methods were used to analyze a harmonic structure of “i” vowel. According to studies performed in Institute of Physiology and Pathology of Hearing in Warsaw by Cudejko et al. [

1] analysis of “i” vowel is very useful to describe the level of nasality in the best way. Normal spectrogram of “i” includes well marked two high energy stripes: first – fundamental frequency (usually around 300 Hz) and second – second harmonic; sometimes third – low energy stripe stands for third harmonic. When nasality is present, first formant gets shifted towards higher frequencies (up to 500 Hz) which makes that the vowel sounds nasal. Based on the analysis of average energy of third, fourth and fifth harmonic during phonation of “i”, three grades of nasality were described by the authors: 1 grade (12-19 dB SPL), 2 grade (20-25 dB SPL) and 3 grade (25 dB SPL and higher). Values lower than 12 dB are considered as no nasality. This scalewas taken as reference for analyses in further parts of this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included 20 Polish adult patients (10 females and 10 males) with post lingual partial deafness (PD, normal hearing thresholds up to 1 kHz and deep hypoacusis for higher frequencies) and 20 individuals with normal hearing in a control group. The average age of PD patients was 50 years (SD 16,1 years) and 48 years in control group (SD 16,4 years). The average time of partial deafness in the study group was 19 years (SD 9,7 years). All patients were patients of Institute of Physiology and Pathology of Hearing in Warsaw and were qualified to partial deafness cochlear implantation.

Patients were subjects to otolaryngological examination including a detailed inspection of oral cavity and palate, otoscopy, anterior and posterior rhinoscopy, and nasofiberoscopy. Audiological examination included pure tone audiometry, impedance audiometry, otoacoustic emissions and brainstem evoked responses audiometry. Individuals were selected in a way to exclude other pre-existing conditions that might lead to nasality (palate cleft, inborn or acquired orofacial defects, neurological disorders, nasal turbinate hypertrophy, nasal polyps, nasopharyngeal tumors etc). Every individual was also subject to a perceptive assessment of nasality performed by an experienced doctor and clinical acoustician.

Acoustic analysis of voice was performed with a MDVP (multi-dimensional voice program) as part of a standard procedure used for patients qualified for cochlear implantation. Subjects were asked to phonate vowel “i”. Recordings of voice samples were made in an anechoic chamber before cochlear implantation and 9 months after cochlear implant activation. Computer processing of voice samples with MDVP included signal analysis as function of time and frequency. The Fast Fourier Transformant (FFT) was used to analyze and present average amplitudes of various frequencies. Values of analyzed amplitudes were then calculated to decibels of speech pressure levels (dB SPL) that enabled assigning nasality to certain degree. Control group consisted of individuals with no nasality present (0) both in perceptive and objective assessment. Statistical analysis was performed using t-test paired two sample for means and correlations were analyzed with Pearson test for correlation analysis.

3. Results

Comparison of signal parameters achieved in PD patients before cochlear implantation to those in control group shows statistical increase in nasality level (p = 0,0001). PD patients presented nasality of different degree, whilst control group individuals presented no nasality in their voices. In objective analysis within PD group 10 subjects presented nasality of degree 1 (50%), 6 individuals presented degree 2 (30%) and 4 individuals presented degree 3 (20%). Average nasality level was 21 dB (SD 4,5). Pearson test was then performed to look for correlation with the time of partial deafness. R index achieved value of 0,33 which represents a positive correlation.

All patients underwent partial deafness cochlear implantation (PDCI). Analysis performed 9 months later showed reduction in nasality, achieving no nasality in 2 individuals (10%), grade 1 in 14 individuals (70%) and grade 2 in 4 individuals (20%). Average nasality level was 17 dB (SD 4,2). Changes vs results before PDCI were statistically significant (p = 0,0002).

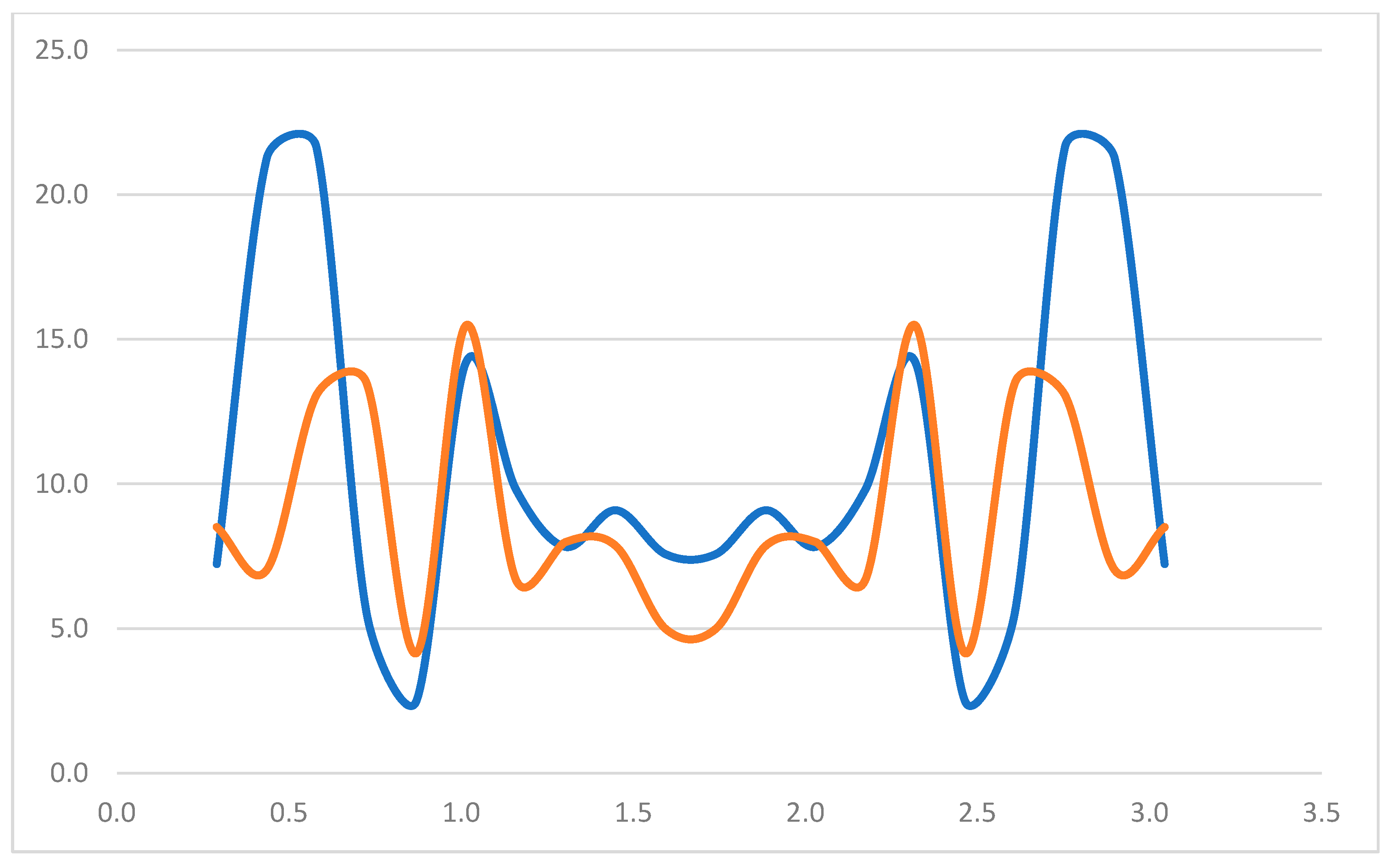

Figure 1 shows Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis that presents the spread of average amplitudes of the signal for certain frequencies, before and after CI.\

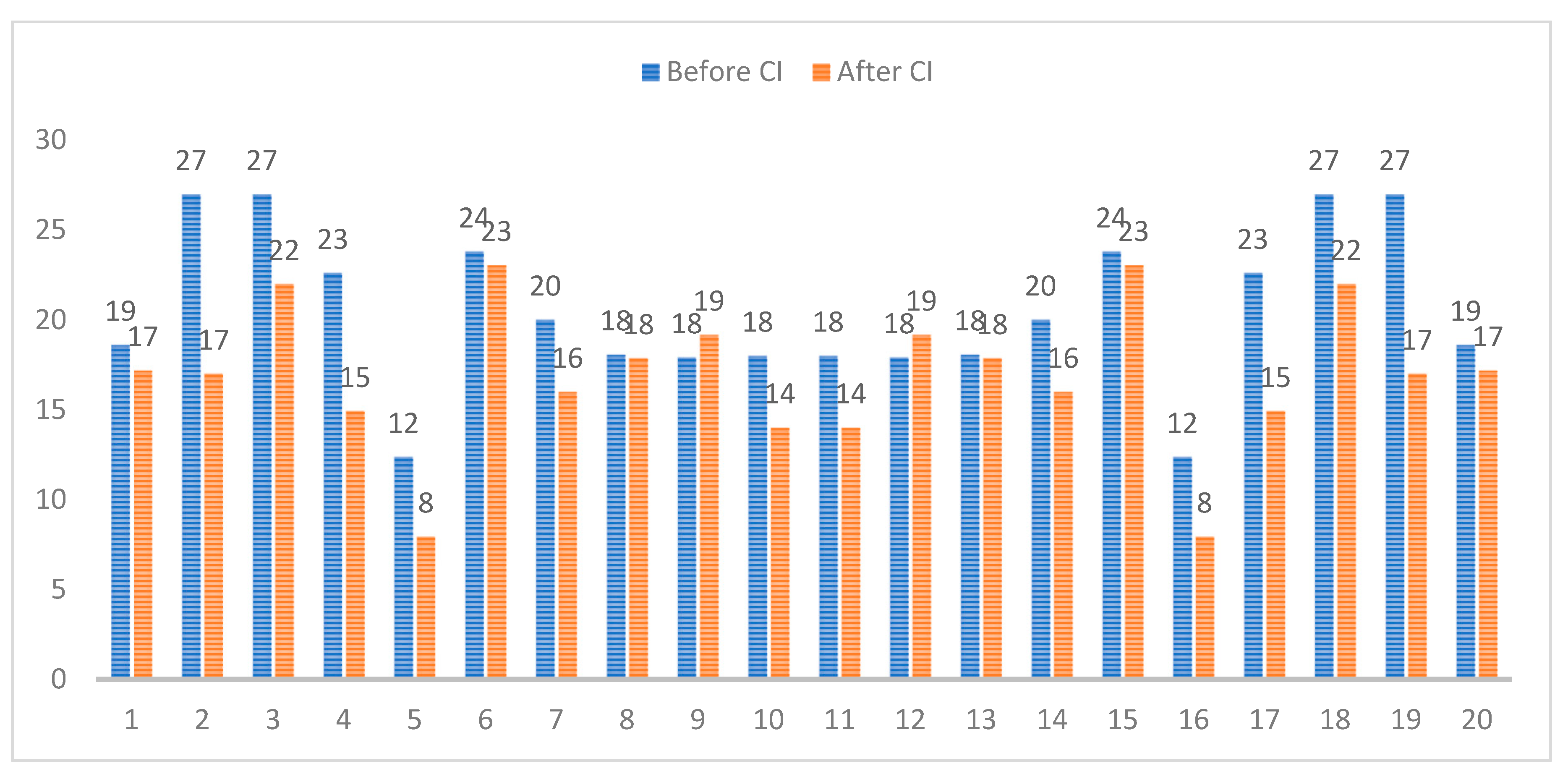

Levels of nasality (in decibels) in PD patients before, and 9 months after partial deafness cochlear implantation were presented in

Figure 2.

In the next step analysis was done to check whether correlations exist between subjective and objective assessment of nasality before and after PDCI. Analysis showed that subjective (perceptual) assessment correlates weakly with objective analysis, achieving r = 0,29 before, and r = 0,20 after cochlear implantation. Comparison of subjective and objective assessment of nasality before and after PDCI is presented in

Table 1.

4. Discussion

First observations on nasality in people with hearing impairment were made years ago. First publications on the topic were made by Hudgins and Numbers in 1942, Boone in 1966, Nober in 1967, Colton and Cooker in 1968 and Norman and 1973 [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Dependency was found between nasality and velopharyngeal function. Mc Clumpha in 1969 [

6] first observed changes in the function of velopharyngeal muscle between normal hearing subjects and those with hearing impairment. In all deaf subjects in the study some velopharyngeal opening was present while producing repeated consonant-vowel syllables. Study performed by Seaver, Andrews, Granata in 1980 [

7] revealed hypernasality in nineteen of twenty six deaf individuals they examined. This was associated by velopharyngeal opening. Radiological examinations excluded anatomical deficiency, therefore changes were of typically functional character. Similar fundings were done by Stevens al. in 1976 [

8], who also found that velopharyngeal insufficiency is caused by inappropriate timing of closing and opening of the palatopharyngeal space. Another suggestion was made, that a reduced rate of speech in the hearing impaired contributes to the perception of nasality as well as increase of air amount used per one syllable.

The above findings were followed by consecutive research conducted in many centers, using both subjective and objective methods of nasality assessment. Ysunza and Vazques [

9] examined a group of deaf individuals and observed a discoordination of velopharyngeal valving activity despite normal muscle activity measured by electromyography. They concluded that the velopharyngeal disorder in such cases is purely functional and results from an inappropriate auditory regulation during phonation. Fletcher, Mahfuzh, and Hendarmin [

10] investigated nasalance in the group of deaf children and compared to the group of their normal hearing peers. The study showed that children with hearing loss presented more nasality. Further studies of Baudonck et al. and Swapna et al. [

11] proved that cochlear implants improve the nasalance to better degree than traditional hearing aids, but still the level of nasalance in both cases is higher than in normal hearing individuals.

Chen [

12] discovered that acoustic analysis of speech in hearing impaired children presents a reduced first formant prominence and a correlation with perceptual assessment of nasality. The study also proved a usefulness of acoustic voice analysis in the assessment of resonance. Kim et al. [

13] in their research found that normal hearing group of subjects demonstrated a significantly lower nasality that the hearing impaired group. They also found that the hearing impaired subjects presented a tendency of velopharyngeal opening during phonation of vowels. The research of Sebastian et al. [

14] proved improvement in nasality after cochlear implantation. Analogical conclusions were drawn from the research conducted by Nguyen et al. [

15] and Guillot et al. [

16].

Our study described in this paper leads to similar conclusions. Partial deafness, as a hearing impairment with appropriate hearing thresholds in low frequencies and deep hearing loss at high frequencies, causes nasality in the affected patients. Statistically important reduction of level of nasality after cochlear implantation proves that restoring hearing control over voice leads to correction in nasal resonance, and improves mechanisms of voice production. The study also confirmed that acoustic method is a valid tool of objective measurement of nasality, better than perceptive assessment.

5. Conclusions

The study showed that partial deafness causes nasality in adults with post lingual partial deafness. The apparent reason of nasality is a disturbance of central control mechanisms of voice production which is coordinated with hearing. Pearson analysis revealed that nasality correlates with the length of partial deafness and the correlation is positive.

Partial deafness cochlear implantation leads to reduction of nasality in 9 months observation by restoring auditory control over voice. Apart from improving hearing, patients benefit from partial deafness cochlear implantation also by reduction of nasality which may improve their comfort of living.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cudejko R, Będziński W, Piłka A, Skarżyśnki H. Assessment of acustic examination in patients with rhinolalia aperta. Now Audiofonol 2012, 1, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lock R, Seaver E. Nasality and velopharyngeal function in five hearing impaired adults. J Commun Disord 1984, 17, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colton R, Cooker H. Perceived nasality in the speech of the deaf. J Speech Hear Res 1968, 11, 553–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens K, Nickerson R, Boothhroyd A, Rollins A. Assessment of nasalization in the speech of deaf children. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1976, 19, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher S, Higgins J. Performance of children with severe to profound auditory impairment in instrumentally guided reduction of nasal resonance. J Speech Hear Disord 1980, 45, 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Clumpha, SL. Cinefluorographic investigation of velopharyngeal function in selected deaf speakers. Folia Phoniatr (Basel). 1969, 21, 368–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaver EJ, Andrews JR, Granata JJ. A radiographic investigation of velar positioning in hearing-impaired young adults. J Commun Disord 1980, 13, 239–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens KN, Nickerson RS, Boothroyd A, Rollins AM. Assessment of Nasalization in the Speech of Deaf Children. J Speech Hear Res. 1976, 19, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ysunza A, Vazquez M. Velopharyngeal sphincter physiology in deaf individuals. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1993, 30, 141–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher S, Mahfuzh F, Hendarmin H. Nasalence in the speech of children with normal hearing and children with hearing loss. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1999, 8, 241–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudonck N, Van Lierde, D’haeseleer E, Dhooge I. Nasalence and nasality in children with cochlear implants and children with hearing aids. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 79, 541–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, MY. Acoustic correlates of English and French nasalized vowels. J Acoust Soc Am 1997, 102, 2360–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim EY, Yoon MS, Kim HH, Nam CM, Park ES, Hong SH. Characteristics of nasal resonance and perceptual rating in prelingual hearing impaired adults. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2012, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sebastian S, Sreedevi N, Lepcha A, Mathew J. Nasalence in cochlear implantees. Clinic Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 8, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen LH, Allegro J, Low A, Papsin B, Campisi P. Effect of cochlear implantation on nasality in children. Ear Nose Throat J 2008, 87, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillot KM, Ohde RN, Hedrick M. Perceptual development of nasal consonants in children with normal hearing and in children who use cochlear implants. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2013, 56, 1133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).